Abstract

Background:

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a collaborative and equitable approach to research inquiry; however, the process of establishing and maintaining CBPR partnerships can be challenging. There is ongoing need for innovative strategies that foster partnership development and long-term sustainability. In 2010, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill developed a CBPR charrette model to facilitate stakeholder engagement in translational research.

Objective:

To describe how the Cancer Health Accountability for Managing Pain and Symptoms (CHAMPS) Study leveraged the CBPR charrette process to develop and strengthen its CBPR partnership and successfully implement research objectives.

Methods:

Fourteen CHAMPS community, academic, and medical partners participated in the CBPR charrette. Two co-facilitators guided the charrette application process and in-person discussion of partnership strengths, needs, and challenges. Community and academic experts with extensive experience in CBPR and health disparities provided technical assistance and recommendations during the in-person charrette.

Conclusions:

Overall, the CHAMPS partnership significantly benefited from the charrette process. Specifically, the charrette process engendered greater transparency, accountability, and trust among CHAMPS partners by encouraging collective negotiation of project goals and implementation, roles and responsibilities, and compensation and communication structures. The process also allowed for exploration of newly-identified challenges and potential solutions with support from community and academic experts. Furthermore, the charrette also functioned as a catalyst for capacity building among CHAMPS community, academic, and medical partners. Future studies should compare the impact of the CBPR charrette, relative to other approaches, on partnership development and process evaluation outcomes.

Keywords: Community-Based Participatory Research, Community health partnerships, Community health research, Health disparities, Power sharing, Process issues, Breast Neoplasms, Neoplasms, Diseases

BACKGROUND

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an effective approach for engaging communities in the identification and mitigation of health inequities.1–6 Principles of CBPR include empowerment and power-sharing, co-learning and capacity building, promotion of research inquiry and intervention, and broad partner engagement in disseminating findings.7–10 Central to the CBPR approach is the collaborative and “[equitable involvement of] all partners in [all phases of] the research process and [recognition of] the unique strengths that each [partner] brings to the table.”9,11 However, this process of establishing, maintaining, and achieving equity in CBPR partnerships can be complex (e.g., multiple partners, geographic and cultural barriers, mistrust) and time intensive, particularly when engaging new partners and/or launching new projects.12–16 Thus, there is ongoing need for effective strategies that facilitate the strengthening and capacity building of new CBPR partnerships to address health disparities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention Research Center (PRC) structure has long provided support for CBPR.17 And since its launch in 2006, the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) mechanism has seeded a range of approaches to community engagement capacity-building through CTSA-funded institutions across the country. Examples of CTSA-generated models include Community Engagement Studios for garnering community stakeholder input in investigator-initiated research;18 funding opportunities to seed research partnerships;19 and curricula, training and tools to build collaborative research capacity.20–23 Dissemination of these capacity-building strategies is critical to enhancing the implementation and long-term sustainability of collaborations to improve community health and equity. This paper will highlight a partnership-focused model for building the capacity of academic institutions to function as more effective partners with communities, the CBPR charrette.

The CBPR Charrette Model

With funding from a CTSA Community Engagement supplement, academic partners from the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute (home of the CTSA at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [UNC-CH]), and the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (HPDP; UNC-CH’s PRC), worked collaboratively with community partners to develop a consulting model focused on partnership development and strengthening, the “CBPR charrette.” A charrette is a collaborative planning process typically used in the fields of design and architecture to “harness the talents and energies of all interested parties to create and support a feasible plan” and bring about community development and transformation.24 The UNC model adapted this approach to develop the “CBPR charrette,” which leverages the expertise of community and academic CBPR experts to offer community and academic research partners technical assistance in partnership development, stakeholder engagement, and decision-making infrastructure, with the ultimate goal of strengthening partnerships and advancing translational research. Based on support from recent literature that community partners in CBPR are often under-compensated for their time and involvement and under-valued for their expertise,25 the UNC CBPR charrette model initiated equitably compensated roles for “Community Experts (CEs),” who are community members with extensive experience in research partnerships, to provide CBPR consultation alongside “Academic Experts (AEs),” who are investigators with an established record and leadership in CBPR. Initially, fourteen CEs from diverse backgrounds and three UNC-CH AEs with extensive expertise in health disparities research were selected by a “Charrette Leadership Team” consisting of community and academic representatives. The Charrette Leadership Team also developed the structure for an in-person CBPR charrette technical assistance session (further detailed in the Methods below). This in-person session is structured so that a partnership can review its assets and strengths as well as its challenges under the consultative guidance of CEs and AEs, who provide advice intended to promote partnership strengthening/sustainability and advance the partners’ research goals.

The charrette service is available free of charge to community and academic researchers with NC TraCS/HPDP funding to compensate the CEs. However, for long-term sustainability, the model is increasingly incorporated into research proposals as a community engagement/partnership development strategy. To request a charrette, a community-academic partnership (with representation from each) must complete a brief application. The essential criteria for the charrette service include: 1) charrette requesters must view themselves as a current, or aspiring, community-academic partnership and 2) representatives from both the community-based organization and the academic institution must draft the questions to be considered during the in-person session, as described more fully in the Methods section.

Since the launch of the model in 2009, CBPR charrettes have been conducted with 18 research partnerships across NC and eight academic institutions and their community partners across the United States. The model has provided technical assistance (e.g., how to establish a Community Advisory Board, develop a governance/decision-making structure, navigate conflict) to partnerships at different phases from newly-formed to mature and has addressed questions at every point along the translational research spectrum according to the specific needs of each partnership. The charrette process has played an instrumental role in building and solidifying new and ongoing research partnerships that align with CBPR principles. The remainder of this paper focuses on a case study of how the charrette process supported a newly-formed CBPR partnership.

Cancer Health Accountability for Managing Pain and Symptoms (CHAMPS) Project

CHAMPS is a recently launched CBPR study aimed at examining racial differences in treatment-related symptoms, symptom management, and treatment completion among Black and White breast cancer patients. CHAMPS is funded through a Diversity Supplement to the Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE) study, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) funded systems change intervention grounded in CBPR and focused on improving racial equity in treatment quality and completion among Black and White breast and lung cancer patients. Building on the long-standing partnerships of the ACCURE study, CHAMPS engages multiple community, academic, and medical partners including UNC-CH, the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative (GHDC), University of Pittsburgh Medical Center-CancerCenter (UPMC-CC), Cone Health Cancer Center (CHCC), and a new partner, Sisters Network Greensboro (SNG).

Although the CHAMPS project initially benefited from the CBPR infrastructure developed under ACCURE, there were multiple nuances to CHAMPS that, from the outset, posed challenges to partnership formation and project implementation. Thus, shortly after receiving NCI funding in early 2015, stakeholders from the CHAMPS research team assembled for a CBPR charrette with the objectives of identifying and addressing community, academic, and medical partner concerns regarding their new research partnership; clarifying roles and responsibilities; and planning for CHAMPS implementation. This paper describes the application of the CBPR charrette process to the CHAMPS study. Specifically, we primarily focus on the partnership among the CHAMPS community, academic, and medical stakeholder partners and how their participation in the CBPR charrette process led to a more effective CBPR partnership and supported implementation of project aims during Year 1 of the CHAMPS study.

METHODS

Setting

With the exception of the setting for the in-person charrette session, the CHAMPS charrette followed the established process and structure of the model. CBPR charrettes are typically held in community settings chosen by the research partnerships requesting the charrette. However, because CHAMPS is a multi-site research study (CHCC in Greensboro, NC and UPMC-CC in Pittsburgh, PA) with limited resources for partnership development and travel, the CHAMPS CBPR charrette was held in Chapel Hill, NC at a UNC-CH-affiliated center convenient and familiar to our NC-based community partners. This location was also chosen in order to ensure inclusion of partners at UPMC-CC, who participated via videoconference.

Stakeholders/Partners

Fourteen stakeholders involved in the development and/or implementation of the CHAMPS project participated in the CBPR charrette. There was representation from the community, including members and Directors from the GHDC and SNG (n=5); academics, including the CHAMPS Principal Investigator (PI), ACCURE Co-PI, UPMC-CC Site PI, and other individuals from UNC-CH and UPMC-CC (n=7); and medical partners, including ACCURE Nurse Navigators from CHCC and UPMC-CC (n=2). Table 1 provides a detailed description of the role of each community, academic, and medical partner in both the CHAMPS study and the CBPR charrette process. In addition to participating in the charrette session and assessing the efficacy and outcomes of the charrette (via post-charrette evaluation forms), all community, academic, and medical stakeholder partners contributed to the development, revision, and final approval of this paper.

Table 1.

CHAMPS Charrette Participants and Roles

| CBPR Charrette Participants | Participant Type | CHAMPS Partnership and Study Role | Charrette Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAMPS Stakeholder Partners | ||||

| UNC-CH • Principal Investigator of CHAMPS • ACCURE Co-Principal Investigator • Research Assistants |

Academic | Leads and oversees coordination and implementation of all CHAMPS research components at CHCC and UPMC Fiscal agent of CHAMPS research funds |

Prepared charrette application alongside lead community partner (GHDC) Provided insight regarding the overall design of CHAMPS, logistical strengths and challenges, and constraints of funding source |

|

| GHDC • GHDC Co-Chair/Director • GHDC Secretary • GHDC Members |

Community | Lead community partner engaged in implementation of CHAMPS research components Represents geographic community served by CHAMPS Holds all research partners accountable to GHDC mission and by-laws for community-engaged research |

Prepared charrette application alongside lead academic partner (UNC-CH) Provided community perspective on the overall design of CHAMPS, potential contributions and concerns of community partners |

|

| SNG • President of SNG |

Community | Represents minority patient community targeted by CHAMPS | Provided patient community perspective on CHAMPS study design and parameters regarding SNG involvement | |

| UPMC-CC • Site Principal Investigator for CHAMPS and ACCURE • Research Assistant • ACCURE Nurse Navigator |

Academic and Medical | Oversees CHAMPS implementation at UPMC-CC Clinical partner for CHAMPS recruitment |

Provided insight regarding UPMC’s clinical and research context as well as the logistical strengths and challenges of implementing CHAMPS at UPMC-CC | |

| CHCC • ACCURE Nurse Navigator |

Medical | Clinical partner for CHAMPS recruitment | Provided insight regarding CHCC’s clinical and research context as well as the logistical strengths and challenges of implementing CHAMPS at CHCC | |

| Charrette Team | ||||

| Co-Facilitators • Charrette Program Director • ACCURE Project Manager |

Community and Academic | N/A | Organized and ensured that all participants adhered to the charrette process Identified Community and Academic Expert Consultants Guided the in-person charrette session ensuring that all participants had equitable opportunity to contribute to the discussion and that all CHAMPS partner questions were addressed |

|

| Community and Academic Expert Consultants • Executive Director of Project Momentum • Project Director of local YMCA • UNC-CH Faculty |

Community and Academic | N/A | Asked clarifying questions during charrette discussion Responded to questions/concerns raised by CHAMPS partners Offered advice and recommendations to address partner questions/concerns |

|

| Observer • UNC-CH Faculty |

Academic | N/A | Drafted charrette discussion notes Administered “Post-Charrette Evaluation Forms” to CHAMPS partners Prepared Post-Charrette Summary Report with contributions from community and academic experts and facilitators |

|

Notes:

CHAMPS - Cancer Health Accountability for Managing Pain and Symptoms

ACCURE - Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity

CBPR - Community Based Participatory Research

UNC-CH - University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

GHDC - Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative

SNG - Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative

UPMC-CC - University of Pittsburgh Medical Center-Cancer Center

CHCC - Cone Health Cancer Center

Co-Facilitators

Two experienced CBPR practitioners facilitated the charrette, one with an academic perspective (CBPR charrette Program Director) and the other with a community perspective (Table 1). The co-facilitators were tasked with adhering to the CBPR charrette process (described further below), ensuring that each participant had room to contribute to the discussion, and guiding the discussion so that all CHAMPS partnership questions were considered and the CE/AE consultants had adequate opportunity to offer advice/recommendations tailored to CHAMPS needs. One co-facilitator, the charrette Program Director, was also responsible for identifying the CE/AE consultants for the CHAMPS charrette process

Community and Academic Expert Consultants

The CHAMPS CBPR charrette process included two CE consultants and one AE consultant (Table 1). Their role in the charrette session was to ask clarifying questions, generate new ideas, respond to the questions raised by CHAMPS partners, and provide advice and recommendations during the charrette that would inform the written Post-Charrette Summary Report (detailed below).

The CHAMPS CBPR Charrette Process

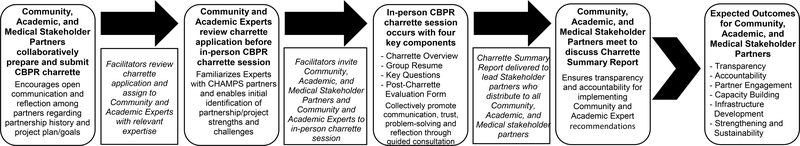

The “overarching goal” of the CBPR charrette process is to move the CBPR partnership and research process forward. While each charrette focuses on the specific needs and questions of a partnership, the process follows a defined structure and series of steps. Conceptually, each step of the charrette process is intended to lead to the overarching goal by facilitating increased transparency, accountability, and engagement among partners, capacity building and infrastructure development, and partnership strengthening and sustainability. Using CHAMPS as an example, Figure 1 depicts the CBPR charrette process described below. The entire CBPR charrette process was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at UNC-CH and designated research exempt.

Figure 1.

The CHAMPS CBPR Charrette Process

Application Process

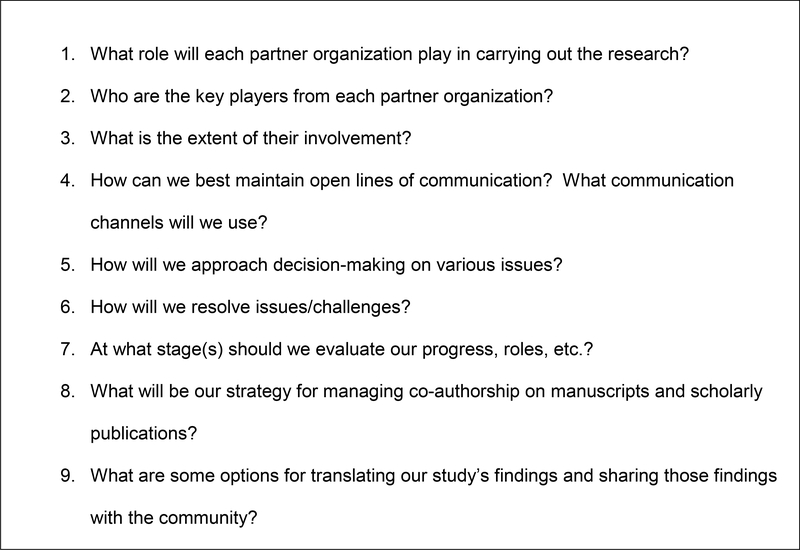

CHAMPS partners, including the CHAMPS PI and lead community partner from SNG, submitted the initial CBPR charrette application. They then worked together to prepare a “Partnership Overview” document to provide important background and context to the CE/AE consultants and co-facilitators. The Partnership Overview document encouraged self-reflection and open communication among CHAMPS partners regarding partnership formation and history; prior experience engaging communities in research; explication of how members agreed on the CBPR approach; partners’ roles in research; health disparity being addressed in the research and its relation to each partners’ mission/goals; population of focus and rationale; recruitment strategies; plans for measurement, methods and analyses; innovative approaches/interventions being employed; benefits to community of interest; and dissemination strategies. The most critical section of the Partnership Overview detailed “key questions” the CHAMPS partners sought to address during the CBPR charrette session. These questions focused on clarifying roles, enhancing communication, and building structures to support CHAMPS as a partnership distinct from the parent ACCURE study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CHAMPS Partnership Overview Key Questions

Application Review

The CHAMPS CBPR charrette facilitators and CEs/AE reviewed the CHAMPS charrette application materials (application and Partnership Overview document) prior to the in-person charrette session. This initial review afforded the facilitators and CEs/AE the opportunity to become familiar with the CHAMPS partnership and research project in order to initially identify partnership/project strengths (internal to partnership), weaknesses (internal to partnership), opportunities (external to partnership), and threats (external to partnership) in preparation for the in-person charrette session.

In-Person Charrette Procedures

The in-person CBPR charrette spans 3 hours and consists of four key components: (1) facilitator-led “Charrette Session Overview”; (2) “Group Resume”; (3) “Key Questions” discussion; (4) “Post-Charrette Evaluation Form” administration. The Charrette Session Overview provides ground rules in order to establish a safe and equitable space for all partners and CEs/AE to express diverse ideas and perspectives. The Group Resume facilitates relationship and trust building among partners through the identification and sharing of partner skills, strengths, and organizational mission. The Key Questions discussion fosters transparency, accountability, and collective problem-solving through open discussion of partner concerns and challenges and solicitation of CEs/AE recommendations for partnership/project strengthening and sustainability. Administration of the Post-Charrette Evaluation Form encourages partner reflection on the charrette process and its impact on the partnership and project planning.

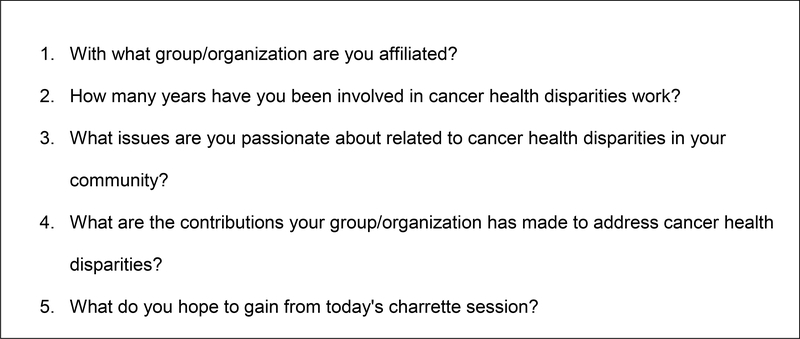

In the case of CHAMPS, after providing an overview of the CBPR charrette session, the co-facilitators led a Group Resume discussion to engage the CHAMPS research partners, many of whom were meeting in-person for the first time, in learning more about one another, assessing each other’s strengths, and clarifying goals for the session. CHAMPS research partners assembled into groups of 4–5 people with diverse representation (i.e., mix of community, academic, and medical partners), and were asked to consider and respond to the questions in Figure 3. Each group reported back to the larger group (i.e., CHAMPS partners, CEs/AE, and co-facilitators) on its discussion. The Group Resume provided a strong foundation for CHAMPS partners to learn more about assets each partner brought to the team, further enhanced the CEs/AE familiarity with the strengths and opportunities available to the CHAMPS partnership, and created an open atmosphere to move into the discussion of challenges and questions to be addressed.

Figure 3.

CHAMPS Partnership Group Resume Questions

Building on the Group Resume activity, the next component of the in-person charrette directly addressed the Key Questions CHAMPS partners identified prior to the session and provided the opportunity to brainstorm solutions, guided by the probing, insightful questions of the CEs/AE. The session ended with a round robin assessment of takeaways from all participants and administration of a Post-Charrette Evaluation Form for CHAMPS partners to evaluate the usefulness and value of the charrette format and CE/AE advice. Throughout the charrette session, an observer (a UNC charrette staff member) drafted discussion notes (e.g., issues/resolutions, details on how the charrette process unfolded, and group interactions) on a computer while the co-facilitators documented discussion points on flip charts at the front of the room for all participants to observe.

Post-Charrette Summary Report

Discussion notes and post-charrette debriefing notes, including reflections and ideas from the CEs/AE, served as the basis for the Post-Charrette Summary Report that was later delivered to CHAMPS partners in order to provide guidance and suggestions for next steps. All CHAMPS partners received the summary report and had ample opportunity to individually and collectively reflect on the Charrette process and discuss the CE/AE recommendations during two separate meetings organized by the CHAMPS steering committee and GHDC. Review of the Post-Charrette Summary Report as a collective CHAMPS partnership helped to maintain transparency and accountability regarding the implementation of the recommendations that emerged from the in-person charrette session.

KEY FINDINGS

Partnership Strengths

The in-person charrette discussion emphasized multiple strengths (internal) and opportunities (external) on which CHAMPS could build. First, CHAMPS partners highlighted the strengths of building on the existing ACCURE partnership, its affiliated organizations (CHCC, UNC-CH, GHDC, and UPMC), and new partner, SNG. In particular, the charrette brought forth the depth of experience among ACCURE’s community and medical partners and demonstrated for the CHAMPS PI, their willingness and capacity to provide intellectual support during project planning, execute components of the CHAMPS grant, and contribute to the dissemination of study findings. Existing ACCURE partners were also able to learn about, engage with, and gain trust in their new academic partners. Specifically, participants discovered synergy among partners, their commitment to a shared mission (i.e., addressing racial disparities in cancer care), and linkages between ACCURE and CHAMPS study aims. Furthermore, all partners became more engaged in utilizing the capacity of the newly formed partnership to assist the CHAMPS PI in developing CBPR skills.

Partnership Challenges

Challenges (i.e., internal weaknesses and external threats) related to some of the key questions detailed in the CHAMPS Partnership Overview document (e.g., roles and expectations, partnership structure) were elucidated during the charrette group discussion. In terms of internal weaknesses, CHAMPS partners expressed concerns related to the roles and expectations of each partner organization. Because CHAMPS was initially designed with primary input from academic partners, there was initial concern among community and medical partners that the study aims would demand unrealistic expectations of SNG, GHDC, and UMPC-CC. Thus, it was important to clarify the scope of the proposed study and its relationship to the individual missions of each partner organization and their expected roles and involvement. There was also uncertainty among all CHAMPS partners regarding the structure and function of the CHAMPS partnership as a whole. For example, although a CHAMPS steering committee was formed prior to the charrette, with representatives from each partner organization, the committee lacked clarity on structure, expectations, and oversight.

Enabled by the “safe space” cultivated from the group resume activity, group discussion of CHAMPS strengths and challenges, and skillful facilitation and discerning questions posed by the CEs/AE, the charrette served as a platform for CHAMPS partners to delineate and negotiate the roles and expectations of each partner. For example, during the session it was determined that members of GHDC and SNG could provide feedback on study tools as they were developed, participate in co-analysis of focus group transcripts with academic partners, and assist in dissemination of findings. Additionally, the critical role of nurse medical partners in facilitating participant recruitment and provider buy-in at each medical center was clarified.

This discussion also highlighted a key issue of funding constraints, an area that often challenges equity in community-academic partnerships.25 While many of CHAMPS’ academic partners were familiar with the stipulations of the Diversity Supplement funding mechanism, there was limited transparency in communicating these “external threats” to the CHAMPS community and medical partners prior to the charrette. The charrette served as a venue for the PI to transparently explain the limitations of the Supplement grant, which in contrast to the ACCURE parent grant, focuses on researcher career development and does not provide funding support for other members of the research team, such as community partners. Consequently, community partner concerns regarding compensation for research contributions, and relatedly, negotiating and supporting their involvement in CHAMPS, emerged as critical issues that needed to be addressed in order to build a strong and equitable partnership.

Community and Academic Expert Recommendations Incorporated into CHAMPS Implementation

The Post-Charrette Summary Report captured recommendations provided by the CEs/AEs in response to the “Key Questions” and challenges discussed during the session. Drawing on the charrette process and CEs/AE recommendations, the CHAMPS team successfully collaborative implemented new CBPR strategies to foster their partnership and accomplish their research objectives. Specifically,

The CHAMPS team clarified the structure and function of its steering committee and initiated bi-weekly steering committee phone calls, with equitable representation from community, academic, and medical stakeholder partners in decision-making and study oversight. CHAMPS updates are now provided during weekly ACCURE (the parent grant) steering committee calls, and at monthly GHDC meetings, with opportunities for discussion and suggestions from the broader groups.

The CHAMPS PI maintains contact with each partner organization, receiving input oneach major decision from all research partners.

- The CHAMPS PI applied for and obtained additional institutional funding to support theinvolvement of community members in the research. With these additional funds, CHAMPS launched paid roles and trainings for Community Member Consultants (CMCs). CMC tasks include:

- Conducting focus groups

- Administering participant surveys

- Partnering with academics in coding focus group transcripts

The GHDC Publications and Dissemination Committee that approves and guides publications from the GHDC has reviewed all planned CHAMPS manuscripts and presentations. All members of the CHAMPS and ACCURE steering committees, CMCs, and the GHDC have been invited to participate in publications and members from each are represented in the authorship of this publication.

Participant Assessment of Charrette Value and Usefulness to CHAMPS

Post-charrette evaluation data collected from CHAMPS partners suggest that the process was productive and useful for the partnership. When asked about the helpfulness of the CEs/AE (response options: not helpful at all; not very helpful, somewhat helpful, very helpful), all respondents (n=9) indicated that the CEs/AE were either “very helpful” or “somewhat helpful”, with most (8 out of 9) reporting they were “very helpful.” In particular, most respondents expressed that the CEs/AE advice on “the importance of asking questions and transparency,” “clarification of the decision-making body” for CHAMPS, and “concrete suggestions regarding funding sources” were most helpful. When asked whether they thought the CBPR charrette process would be helpful to the CHAMPS partnership, all respondents reported “yes,” adding that the charrette enabled “honest examination of the partnership and how to move forward with the project,” “helped to clarify roles and future work together,” and “increased lines of communication.” Furthermore, all respondents indicated that they would recommend a CBPR charrette to colleagues interested in employing a CBPR approach.

CONCLUSIONS

The establishment and long-term sustainability of CBPR partnerships can be enhanced through processes that facilitate partner engagement, communication, capacity building, and infrastructure that support shared power, decision-making, and governance.26–29 In this paper, we described how the charrette process enabled all CHAMPS partners to engage in a collaborative planning session during which participants negotiated the goals and implementation time frame of the CHAMPS study, role and responsibilities of each partner, and compensation and communication structures. Furthermore, the charrette process elucidated important concerns and challenges that, if left unaddressed, could have potentially jeopardized the integrity of the partnership and planned implementation of the CHAMPS study.

Overall, the CHAMPS partnership significantly benefited from the charrette process. Responses to the Post-Charrette Evaluation Form revealed that several partners gained greater confidence in the overall fit and feasibility of pursuing CHAMPS. The charrette process engendered greater transparency, accountability, and trust within the CHAMPS team, enabling all partners to gain a better understanding of roles and expectations and weigh in on how to establish a shared decision-making process (e.g., formalization of CHAMPS Steering Committee, adoption of GHDC publication guidelines). Moreover, by acting on the CEs’/AE’s recommendation to seek additional funding through institutional sources, community partner concerns were validated, their value and contribution to CHAMPS was openly recognized, and the partnership was fortified through acquisition of additional funding to support community member engagement in CHAMPS.

The charrette also functioned as a catalyst for capacity building for CHAMPS community, academic, and medical partners. Successful implementation of the charrette recommendation to recruit, train, and fund a cadre of CMCs to support the CHAMPS project has been critical to the execution of this study (e.g., community-academic qualitative analysis of CHAMPS focus group transcripts). The charrette process also significantly contributed to the professional development of the CHAMPS PI, a junior faculty member without prior CBPR experience who initially struggled with identifying and addressing gaps in the CHAMPS partnership. Although the CHAMPS PI received individual training on CBPR and community engaged research prior to the charrette, the charrette process served as a pivotal “co-learning” opportunity that helped equip her with the skillset, support, and confidence needed to carry out the CHAMPS study in a collaborative, transparent, and accountable manner. Furthermore, the charrette session also served as a critical “co-learning” opportunity for CHAMPS medical partners, who gained a better understanding of the components of the CHAMPS study that would necessitate accessing patient health information. This understanding facilitated CHAMPS medical partners’ efforts to identify and engage other key medical stakeholders from their respective medical centers.

In light of the strengths of the CHAMPS CBPR charrette process, there are some challenges and limitations worth noting. First, the charrette was held six months after submission of the CHAMPS grant proposal, which was developed through a less equitable partnership process that primarily involved UNC-CH academic partners. Ideally, the charrette would have occurred prior to grant submission to more fully involve community and medical partners from the outset, thereby, increasing transparency and mitigating some of the role confusion, decision-making, and compensation concerns that arose after the project was funded. Still, as illustrated in this paper, the charrette experience proved beneficial during the early stages of CHAMPS partnership development and project implementation process. Moreover, given that many CBPR partnership are formed after a grant has been submitted/awarded, our CHAMPS CBPR charrette experience demonstrates that the charrette process can still be quite beneficial to collaborations emerging after funding has been awarded, and highlights a key strength of CBPR charrettes. Secondly, to involve an out-of-state partner (UPMC-CC) in the charrette, the charrette coordinators set up a live video conference session, a first for the CBPR charrette organizers. However, there were technical challenges, including audio/visual issues and lack of in-person interpersonal engagement with NC-based partners. Thus, for CBPR studies involving multisite collaborations, it is important to consider alternative strategies for charrette engagement when travel to the same location is not feasible for all research partners. Lastly, implementation of CE/AE recommendations has at times been challenging and time consuming. For example, securing a separate funding mechanism to support the important work of CMCs meant that the CHAMPS PI had to learn and undertake a new set of administrative/financial duties. Additionally, the research timeline had to be modified in order to accommodate the CMC training and engagement process. Although these new tasks and processes have been critical to the development and implementation of CHAMPS, other CBPR partnerships should be cognizant of the potential logistical implications of pursuing the recommendations that emerge from a CBPR charrette process (e.g., accommodating new time intensive tasks while simultaneously demonstrating productivity to funding agencies and academic institutions).

In summary, the CBPR charrette process was an effective partnership planning and stakeholder engagement strategy for the CHAMPS partnership. A key feature of the charrette process, that potentially enhances its impact, is its systematic consultant-style model that leverages the collective and individual expertise of Community and Academic Experts, who are well-positioned to assess partnership vulnerabilities and offer recommendations for partnership development and sustainability. Additionally, the Post-Charrette Summary Report offers ongoing reflection and accountability opportunities regarding partnership status and shared research implementation planning. Future studies should empirically assess the impact of the CBPR charrette process, relative to other approaches, on partnership development and process evaluation outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallerstein NB, Duran B: Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 7:312–23, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaal JC, Lightfoot AF, Black KZ, et al. : Community-Guided Focus Group Analysis to Examine Cancer Disparities. Prog Community Health Partnersh 10:159–67, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbah O, Ford JG, Qiu M, et al. : Mobilizing social support networks to improve cancer screening: the COACH randomized controlled trial study design. BMC Cancer 15:907, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone LR, Edington K, Rosenberg J, et al. : Building a navigation system to reduce cancer disparities among urban Black older adults. Prog Community Health Partnersh 7:209–18, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, et al. : Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health 98:1398–406, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun KL, Stewart S, Baquet C, et al. : The National Cancer Institute’s Community Networks Program Initiative to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities: Outcomes and Lessons Learned. Prog Community Health Partnersh 9 Suppl:21–32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. : Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 113:1463–71, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff M, Maurana CA: Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health: a qualitative study of perspectives from communities. Acad Med 76:166–72, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. : Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles, in Minkler M, Wallerstein N (eds): Community based participatory research for health San Francisco, : Jossey-Bass, 2003, pp pp.53–76 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed SM, Maurana C, Nelson D, et al. : Opening the Black Box: Conceptualizing Community Engagement From 109 Community-Academic Partnership Programs. Prog Community Health Partnersh 10:51–61, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. : Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 19:173–202, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, et al. : The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: points to consider. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 5:19–31, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonas MA, Jones N, Eng E, et al. : The art and science of integrating Undoing Racism with CBPR: challenges of pursuing NIH funding to investigate cancer care and racial equity. J Urban Health 83:1004–12, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins DL, Metzler M: Implementing community-based participatory research centers in diverse urban settings. J Urban Health 78:488–94, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, et al. : Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2008. pp. pp. 371–392 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, et al. : Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. American Journal of Public Health 93:803–811, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins-Cox D, Harris JR, Brownson RC, et al. : Prevention Research Centers Program: Researcher-Community Partnership for High-Impact Results, in Gullota TP, Bloom M (eds): Encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion, Springer; US, 2014, pp 248–273 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. : Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach to Obtaining Meaningful Input From Stakeholders to Inform Research. Acad Med 90:1646–50, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tendulkar SA, Chu J, Opp J, et al. : A funding initiative for community-based participatory research: lessons from the Harvard Catalyst Seed Grants. Prog Community Health Partnersh 5:35–44, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin CL, Martinez LS, Tse L, et al. : Creating a Culture of Empowerment in Research: Findings from a Capacity-Building Training Program. Prog Community Health Partnersh 10:479–488, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zittleman L, Wright L, Ortiz BC, et al. : Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement: Because You Can’t Study What You Don’t Know. Prog Community Health Partnersh 8:117–24, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodgers KC, Akintobi T, Thompson WW, et al. : A Model for Strengthening Collaborative Research Capacity: Illustrations From the Atlanta Clinical Translational Science Institute. Health Educ Behav 41:267–74, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews JO, Cox MJ, Newman SD, et al. : Training partnership dyads for community-based participatory research: strategies and lessons learned from the Community Engaged Scholars Program. Health Promot Pract 14:524–33, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The NCI Charrette System: The NCI charrette system is more than the charrette, 2016

- 25.Black KZ, Hardy CY, De Marco M, et al. : Beyond incentives for involvement to compensation for consultants: increasing equity in CBPR approaches. Prog Community Health Partnersh 7:263–70, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R: Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q 79:179–205, III-IV, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. : Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J Urban Health 83:1022–40, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Examining Community-Institutional Partnerships for Prevention Research Group: Building and sustaining community-institutional partnerships for prevention research: findings from a national collaborative. J Urban Health 83:989–1003, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yonas M, Aronson R, Coad N, et al. : Infrastructure for equitable decision making in research.. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health,, 2012 [Google Scholar]