Abstract

Purpose:

To characterize the tumor-infiltrating immune cells population in Kras/p53-driven lung tumors and to evaluate the combinatorial anti-tumor effect with MEK inhibitor (MEKi), trametinib, and immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting either programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death protein ligand 1 (PD-L1) in vivo.

Experimental Design:

Trp53FloxFlox;KrasG12D/+;Rosa26LSL-Luciferase/LSL-Luciferase (PKL) genetically engineered mice were utilized to develop autochthonous lung tumors with intratracheal delivery of adenoviral Cre recombinase. Using these tumor-bearing lungs, tumor-infiltrating immune cells were characterized by both mass cytometry and flow cytometry. PKL-mediated immunocompetent syngeneic and transgenic lung cancer mouse models were treated with MEKi alone as well as in combination with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs. Tumor growth and survival outcome were assessed. Finally, immune cell populations within spleens and tumors were evaluated by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry.

Results:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were significantly augmented in PKL-driven lung tumors compared to normal lungs of tumor-free mice. PD-L1 expression appeared to be highly positive in both lung tumor cells and, particularly MDSCs. The combinatory administration of MEKi with either anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs synergistically increased anti-tumor response and survival outcome compared with single-agent therapy in both the PKL-mediated syngeneic and transgenic lung cancer models. Theses combinational treatments resulted in significant increases of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, whereas attenuation of CD11b+/Gr-1high MDSCs, in particular, Ly6Ghigh polymorphonuclear-MDSCs in the syngeneic model.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest a potential therapeutic approach for untargetable Kras/p53-driven lung cancers with synergy between targeted therapy using MEKi and immunotherapies.

Keywords: Trametinib, PD-1, PD-L1, MDSC, Kras/p53-driven lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer, and despite all the advances in cancer treatment, the overall 5-year survival rate remains dismal at 18% 1,2. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) which accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancers is further divided mainly in two groups: adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). KRAS mutation, known as oncogenic driver mutation, has been detected in 20~40% of LUAD and in 3~6% of LSCC 3–5. We have focused on finding new strategy for the KRAS-mutant lung cancer, because there is no clinically effective targeted treatment for this subtype 6–10.

Targeting KRAS signaling has been aimed at its downstream targets, one of which is mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK) 11. However, monotherapy with MEK inhibitor (MEKi) for KRAS-mutated NSCLC has been reported to be largely ineffective 12,13. Moreover, MEKi in combination with conventional chemotherapy caused greater toxicity without improvement in clinical outcomes 14, 15. This observation indicated the need for dose reduction to complete a full cycle of the combination therapy.

Finding a novel strategy for KRAS-mutated NSCLC, it is noteworthy that antagonist monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting programed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), which mediates immunosuppression 16, 17, have been approved for the treatment of advanced NSCLC 18–20. Previous studies have demonstrated KRAS-mutated NSCLC is correlated with up-regulated PD-L1 19,21,22, which indicate that PD-L1 could function as an immune escape mechanism of KRAS-mutated NSCLC. In the clinical studies, however, KRAS mutational status did not seem to be associated with a survival benefit of immune checkpoints inhibitors 20, 23. Therefore, the combinations of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade with other agents would be required to produce higher efficacy.

Here, we have studied the antitumor effect of reduced dose of MEKi in combination with immune checkpoints inhibitors against Kras/p53-driven lung tumors using a Kras G12D mutation and p53 deficiency-driven lung cancer mouse model; Trp53floxflox;KrasLSL-G12D/+.R0sa26LSL-Luciferase/LSL-Luciferase (PKL). We found that combinatorial treatment significantly blocked tumor growth and extended survival outcome in the preclinical models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic lung cancer mouse models

All experiments with animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Yale University (#2017–11464). All animals were housed in the Yale University Animal Facility under the guidelines held by the Yale IACUC. KrasLSL-G12D/+ (strain 01XJ6, B6/129Sv) and Trp53Flox/+ (strain 01XC2, FVB/129) strains were obtained from the National Cancer Institute of Frederick Mouse Repository, and FVB.129S6(B6)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(Luc)Kael/J (005125, FVB/129) strain was purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Based on the method of DuPage et al. 24, the PKL mice were intratracheally infected with adenoviral particles encoding for Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre; 5 × 106 PFU, University of Iowa, IA, USA). Tumor incidence and growth were quantified by bioluminescence live animal imaging (IVIS Spectrum; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). For IVIS images, signal intensity was quantified as the radiance unit of photons/sec/cm2/sr which means the number of photons per second that level a square centimeter of tissue and radiate into a solid angle of one steradian (sr). For ex vivo imaging, mice were injected with D-luciferin and followed by collection of its organs after euthanasia.

Murine lung tumor cells

PKL5–2 murine lung tumor cell line was established from lung tumors derived from our PKL model (FVB dominant). Cells were cultured with RPIMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlasbad, CA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. PKL5–2 cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma-negativity in the study.

Treatment

PKL mice received food and water ad libitum. Lung tumors were induced by Ad-Cre in the transgenic mouse model as described above. Syngeneic tumors were established by subcutaneously implanting 3 × 105 PKL5–2 cells into the right flank of mice. Tumor volume was calculated using the equation (l × w2)/2, where l and w refer to the larger and smaller dimensions collected at each measurement. Treatments began with tumor size 50 to 200 mm3. Trametinib (Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) was daily administered as 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/kg in 2% DMSO-5% polyethylene glycol (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) by oral gavage. Anti-PD-1 (RMP1–14) and anti-PD-L1 (10F.9G2) mAbs were purchased from BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH, USA). These antibodies were intraperitoneally administered as 200 μg/mouse in PBS twice a week. Tumors were monitored daily, and mice were euthanized when an endpoint was reached, defined as tumor volume greater than 1,000 mm3, tumor ulceration, or study end, whichever came first. Tumor regressions, median tumor volume, and treatment tolerability were also considered. Tumor weight was measured at the endpoint of study. The median time to endpoint and its corresponding 95% confidence interval were calculated.

Mass cytometry and Fluorescence-based Flow Cytometry

All tissue preparations were performed simultaneously from each individual mouse. Spleen and either lung tumor or subcutaneous tumor were digested using Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn CA, USA). For mass cytometry (CyTOF) analysis, cells were incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 mAbs (clone 2.4G2, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) and subsequently incubated with a cocktail of metal-conjugated Abs against surface markers on ice. cells were incubated with IrDNA intercalator (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA, USA) at 4°C for overnight. For flow cytometry, lung single cell suspensions were prepared as previously described. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated Abs on ice. Cells were washed and followed by acquisition using the standard protocol on LSRII flow cytometry instrument (BD Bioscience). Acquired data were analyzed with CyToBank (Cytobank Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and FlowJo (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA) software, for CyTOF and flow cytometry, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry,Immunofluorescence staining and western blotting

Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and subjected to high-temperature antigen retrieval in 0.01 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Slides were incubated with Dual Endogenous Enzyme Block (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and followed blocking with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS/0.1 % Tween-20. Primary antibodies against anti-CD45 (ab10558) and anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (ab4051) purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), CD3 (Biocare Medical, CP215) purchased from Biocare Medical (Pacheco, CA, USA), PD-L1(#13684) and PCNA (#2586) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) were used for the staining following dilution in SignalStain® Antibody Diluent. SignalStain® Boost (HRP, Rabbit or Mouse, Cell Signaling Technology) secondary antibodies were used and followed by DAB+ Chromogen (Agilent) staining. For immunofluorescence staining was followed the protocol as previously described 25. For western blotting, PKL5–2 cells were simultaneously exposed to the combinational treatment of trametinib (10 nM) and anti-PD-Ll antibody (2 μg/ml) with or without IFN-r (10 ng/ml; Peprotech, NJ, USA) or IFN-a (40 ng/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) for 24 hours. Cell lysates were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 % SDS, 1 % sodium deoxycholate, 1 % NP-40) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting with anti-cleaved PARP (#5625), anti-PARP (#9542), anti-Caspase 7 (#12827), anti-cleaved Caspase 3 (#9664) and anti-Caspase 3 (#9665) antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-P-actin (Sigma; A2228) was used for loading control.

Statistical analysis

Plot and bar graphs show the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) as calculated by Student’s t-test. Differences between treatment groups were determined by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s posttest. A Kaplan-Meier plot was generated to show survival by treatment group and significance was assessed by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7 and differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Immunogenic autochthonous lung adenocarcinomas driven by PKL harbor abundant PMN-MDSCs.

We independently generated PKL model by intercrossing of Trp53flox/flox;KrasLSL-G12D/+ mouse with a mouse harboring loxP-stop-loxP followed by firefly luciferase in Rosa 26 locus (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Using the mice, intratracheal delivery of Ad-Cre was performed for the development of autochthonous lung tumors. We confirmed that luciferase-mediated bioluminescence is specific to the PKL-driven tumors but not visualized in other organs by live animal imaging using IVIS system (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

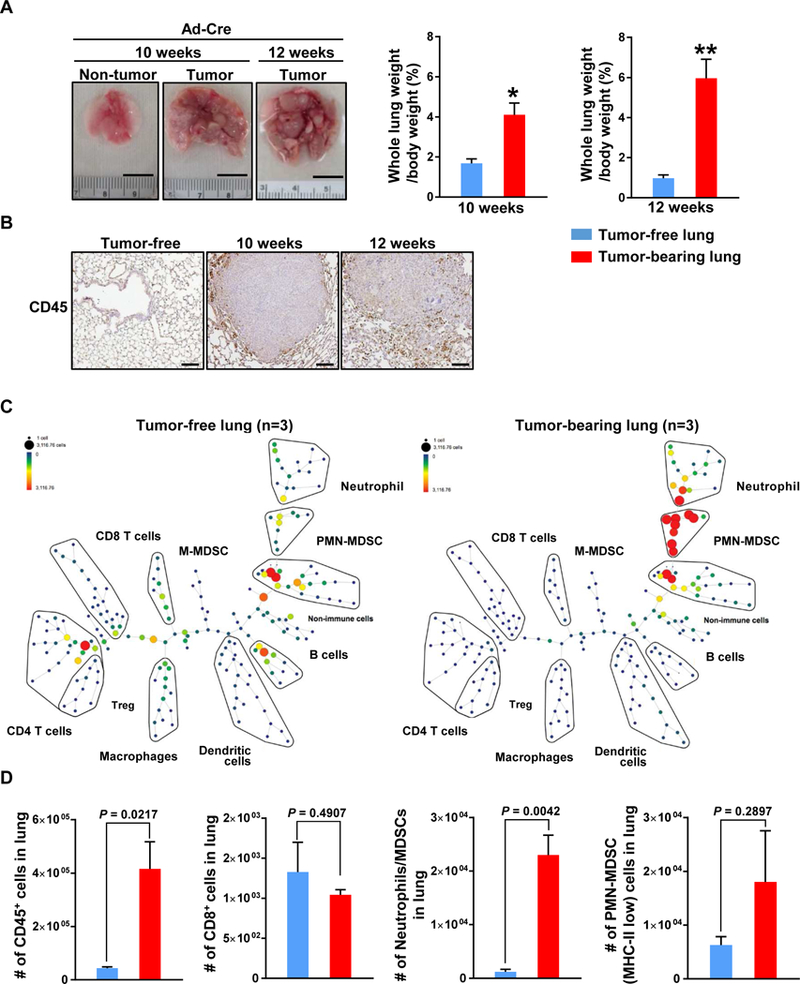

The tumor initiation by Ad-Cre yielded a large number of lung tumors at week 10, as indicated by 2.43-fold higher of the increased percentage of whole lung weight per body weight ratio in tumor-bearing mice compared to tumor-free mice (Fig. 1A; P = 0.0262). Furthermore, these tumors constituted the majority of lung composition at 12 weeks after Ad-Cre (Fig. 1A). We next examined the status of immune cells in these lung tumor specimens by immunohistochemical staining. Interestingly, CD45+ cells were dramatically accumulated mainly at the periphery, but not inside, of tumor nodules (peritumoral regions) in PKL-driven lung tumors in comparison with normal lungs from tumor-free Kras wild-type (Kras+/+) mice, at week 10 and 12 (Fig. 1B). Of note, both Trp53flox/flox;Rosa26LSL-Luc/LSL-Luc concomitant with either Kras+/+ or KrasLSL-G12D/+ mice were identically infected by Ad-Cre to rule out the effect, if any, of the immune response to viral infection and luciferase-mediated immunogenicity.

Figure 1.

Prominent infiltration of immune cells in lung tumor driven by KrasG12D and p53 knockout lung cancer mouse model. A, Representative lungs from Kras+/+;Trp53flox/flox (Non-tumor, n=6) and KrasLSL-G12D/+;Trp53flox/flox (Tumor) mice at 10 (n=6) and 12 weeks (n=6) after Ad-Cre infection. Scale bar = 1 cm (Left). Grossly enlarged tumor bearing lungs relative to tumor-free lungs as shown an average percentage of whole lung weight of body weight (Right). B, A significant increase in the infiltration of immune cells as shown by IHC for CD45 in lung tumors (n=3 each time points) compared with tumor-free lung (n=3). C, SPADE tree derived from CyTOF (15 markers) analysis of whole tumor cell population from either Kras/p53 mutants (Right) or control (Left) mice at 12 weeks after Ad-Cre induction. (n=3). D, Total number of the indicated immune cells in lung. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. P values were determined by 2-tailed t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005

To characterize the tumor-infiltrated immune cells in this model, we conducted a multivariate single-cell analysis using mass cytometry (CyTOF). Using CyTOF analysis, we first observed drastic increases of both CD45+ cells (P = 0.0217) and CD45- cells in tumor-bearing lungs compared to tumor-free lungs (Fig. 1C, 1D and Supplementary Fig. 2). We also identified that neutrophils/polymorphonuclear MDSCs (CD45+/CD11b+/Ly6Ghigh/Ly6Clow) were significantly more abundant in tumor-bearing lungs (P = 0.0042) while CD3+/CD8+ T cells showed a tendency to decrease in tumor-bearing lungs compared to tumor-free lungs. To get further insight into subpopulation of MDSCs, we used MHC-II marker on these cells and we observed that polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs; CD45+/CD11b+/Ly6Ghigh/Ly6Clow/MHC-IIlow) cell population tended to be increased in tumor- bearing lungs, compared with tumor-free lungs (Fig. 1C and 1D). Of note, PMN-MDSCs population in tumor-bearing lungs was accounted for approximately 17% of the CD45+ immune cells in the whole lung. Indeed, we did not observe a significant difference in the percentage of regulatory T cells (FoxP3+) in this tumor model in comparison with tumor-free lung (Supplementary Fig. 3).

PD-L1 is highly expressed in both tumor cells and MDSCs in murine lung tumors driven by PKL.

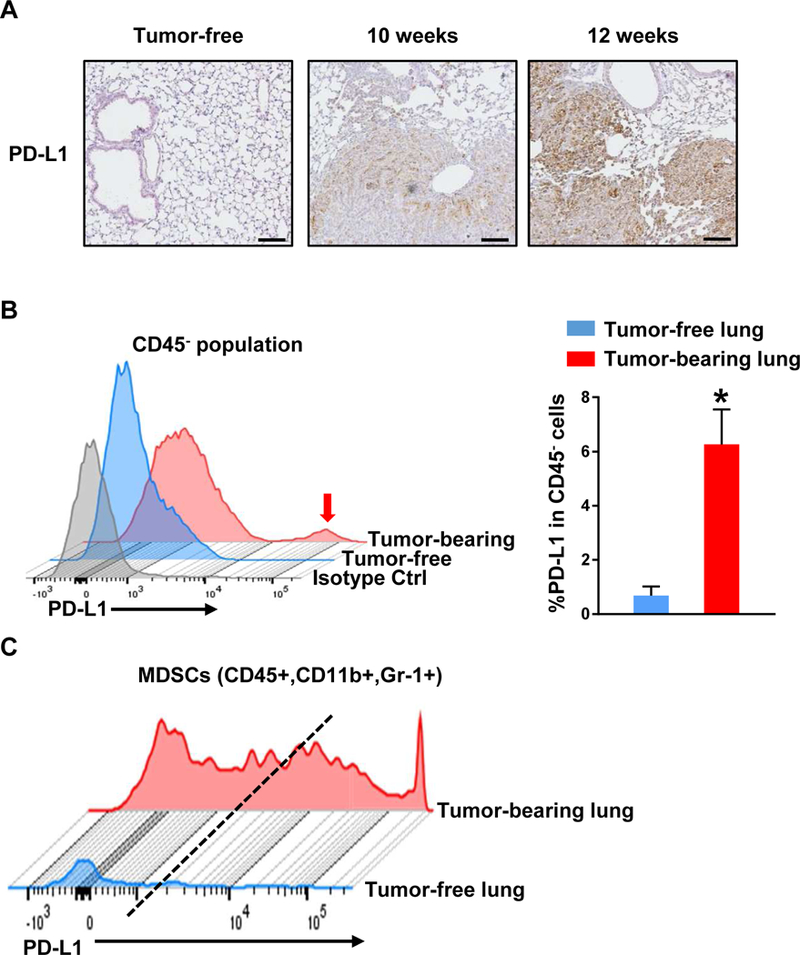

Given that the PD-L1 is an immunosuppressive pathway that is found to be active in the tumor microenvironment, we conducted immunohistochemistry (IHC) with a mouse-specific antibody against PD-L1 using the formalin-fixed paraffin embedded lung tumor tissues in order to see the status of PD-L1 expression. Elevated PD-L1 expression in tumor-bearing lungs was exhibited in a time-course manner upon Ad-Cre induction in the mice (Fig. 2A). Moreover, PD-L1 expression was also higher in CD45- cells isolated from tumor-bearing lungs compared to CD45- cells from tumor-free lungs as determined by flow cytometry, as we expected (Fig. 2B). Indeed, neutrophils/MDSCs isolated from the tumor-bearing lungs also showed substantially higher PD-L1 expression than those found in the tumor-free lungs (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that PD-L1 expressed MDSC, in particular, neutrophils/PMN-MDSCs were accumulated in our Kras/p53-driven lung tumors, suggesting this accumulation may precede tumor progression.

Figure 2.

PD-L1 expression is significantly elevated not only in non-immune cells but also in MDSCs of tumor-bearing lungs as compared with tumor-free lungs. A, A prominent expression of PD-L1 is seen in tumors derived from Kras/p53-mutated mice in a time course manner as shown by IHC for PD-L1 (n=3). Scale bar = 100 μm. B, Highly overexpressed PD-L1 population in CD45- (non-immune) cells of tumor-bearing lungs compared with tumor-free lung. Isotype control antibody for PD-L1 was applied in this flow cytometry analysis (n=6). C, Elevated PDL1 expression in CD11b+/Gr-1+ MDSCs of lung tumors compared with control lungs as shown by flow cytometry analysis. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. P values were determined by 2-tailed t test. *P < 0.05.

Combination of MEKi and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs attenuated tumor growth leading to prolonged survival in PKL-transgenic lung cancer mouse model.

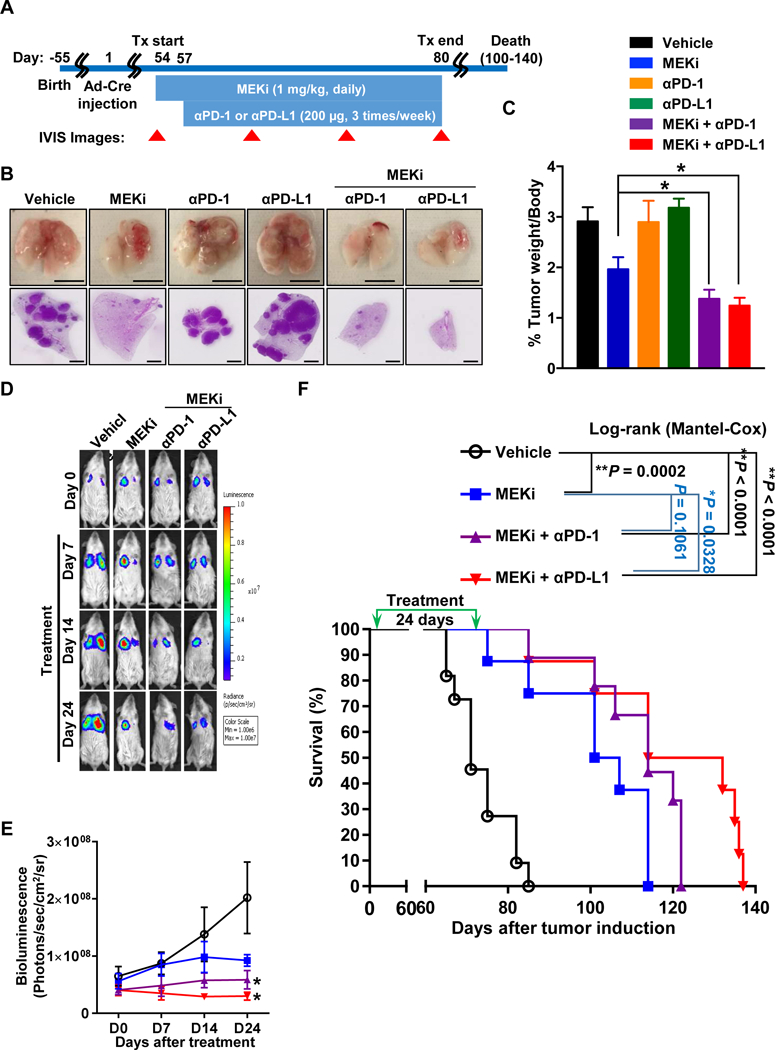

Upon our findings of the elevated PD-L1 expression in the Kras/p53-driven lung tumors as favorable immunotherapy marker, we first decided to explore a potential combinational treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapies and MEKi using our PKL transgenic lung cancer mouse model since MEK has been considered as a direct downstream effector of KRAS oncogenic signaling. Lung tumor-bearing PKL mice induced by intratracheal administration of Ad-Cre were treated with MEKi, trametinib, for three days prior to initiation of combination treatment and followed by further administration of MEKi as a single or combination treatment with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs for following three weeks (Fig. 3A). We observed that any single-agent therapies using either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs failed to control tumor progression (Fig. 3B and 3C). In contrast, MEKi alone and in combination with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs significantly decreased both number and size of tumor nodules as shown grossly visualized and on hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) stained specimens resulting in an attenuation of lung weight/body weight ratio at the endpoint (Fig. 3B and 3C). Moreover, we confirmed that these combinational treatments of MEKi with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs were associated with significant suppression of tumor progression driven by Kras/p53 mutations by IVIS imaging (Fig. 3D and 3E). Indeed, the combinational therapies, but not single agent therapies, resulted in significant improvement of survival compared to vehicle-treated control mice, in particular, the combination with MEKi and anti-PD-L1 mAb (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

MEKi combined with anti-PD-Ll yields anti-tumor efficacy and prolonged survival in the bioluminescent PKL transgenic lung cancer mouse model. A, Schematic of dosing schedule. 6–8 weeks old PKL mice were infected by Ad-Cre through intratracheal intubation. Treatments began on day 54 after Ad-Cre induction, indicated as day 54–57 of drug treatment for MEKi alone and further day 57–80 of drug treatments for the combination of MEKi with anti-PDl or anti-PD-Ll antibodies (n = 8 each group). B, Representative images of gross lung tumors and H&E stained lung lobe in each treatment group. Scale bar = 1 cm (lung pictures) or 1 mm (H&E lobe). C, percentages of whole lung weight per body weight in each group, (mean ± SEM; n=8; *P < 0.05; vehicle vs. combination treatment groups). D and E, Representative images of the bioluminescent in vivo (D) and its bioluminescence intensity monitoring (E) in a time-course manner (mean ± SEM; n=8; *P<0.05). F, Kaplan-Meier survival curve of PKL mice treated with MEKi and either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-Ll antibodies compared to vehicle treated mice (vehicle = 16, MEKi = 8, MEKi + anti-PD-Ll = 9, MEKi + anti-PD-Ll = 8).

Combination of MEKi and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs synergistically abolished tumor growth in syngeneic Kras/p53 mouse model.

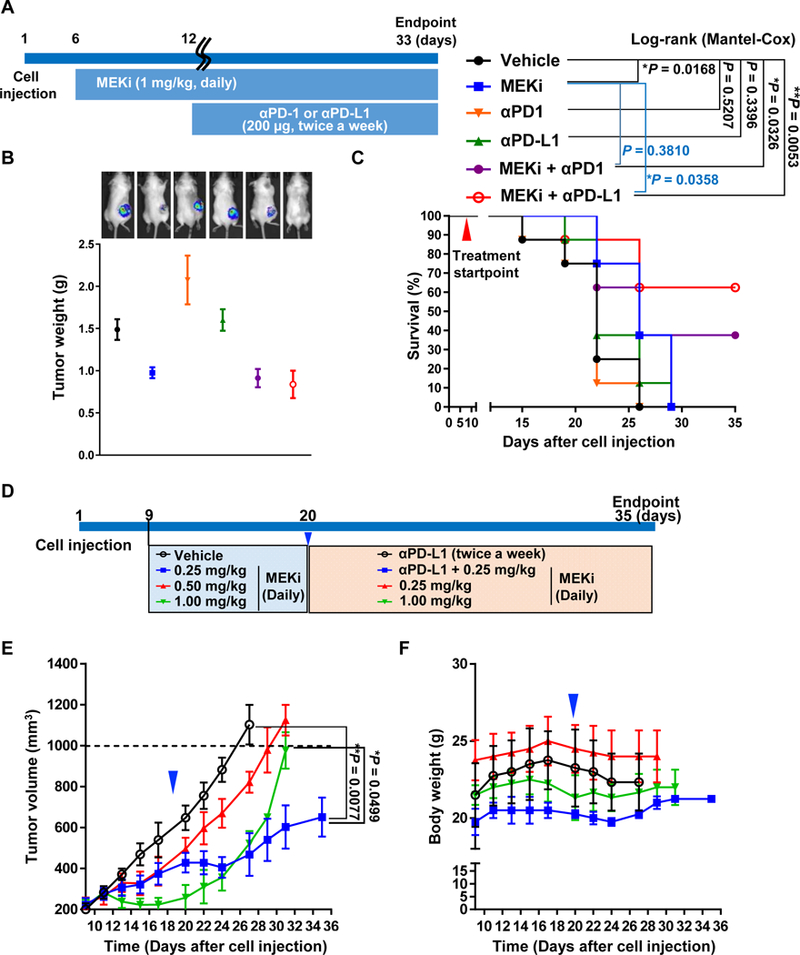

The anti-tumor effect of the combinational treatment was evaluated in the immunocompetent syngeneic model. We initially determined whether one of our murine lung tumor cell lines, called PKL5–2 cells, derived from lung tumors in our PKL-transgenic mice could respond to the immunotherapies by measuring the expression of PD-L1 in the cells. Interestingly, PD-L1 expression was low in resting PKL5–2 tumor cells, whereas its expression on these cells was dramatically induced by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) addition, as determined by flow cytometry, indicating the possibility of response to immunotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, PKL mice were subcutaneously implanted with PKL5–2 lung tumor cells and followed by administration of MEKi, anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1 as a single or a combination (Fig. 4A). In consistent with our finding in the transgenic model, single agent anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 treatments were ineffective or even worse than the control group in tumor growth (Fig. 4B). However, MEKi alone and in combination with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs substantially reduced tumor growth as determined by bioluminescence imaging and tumor weight at the endpoints (Fig. 4B). In consistent with the result from our transgenic model, MEKi in combination with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs also dramatically resulted in prolonged survival of mice, but not MEKi alone (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Anti-tumor effect and prolonged survival benefit by the combination of MEKi with immunomodulators targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 in the PKL5–2 murine lung tumor syngeneic model. A, Schematic of dosing schedule. MEKi began on day 6 after tumor cell implantation, indicated as day 6–12 of drug treatment for MEKi alone and further day 12–33 of drug treatments for the combination of MEKi with anti-PDl or anti-PD-Ll antibodies. Mice (n=8 per group) were treated with MEKi at 1 mg/kg oral gavage daily, or with antibodies, α-mouse PD-1 (RMP1–14 clone) or α-mouse PD-L1 (10F.9G2 clone) mAbs at 200 μg/mouse i.p. twice weekly until tumors reached the endpoint of 1,000 mm3 or by study endpoint. B, Significant decreased tumor masses by the combination of MEKi with either anti-PDl or anti-PD-Ll antibodies and representative bioluminescence imaging of treated mice. Tumor masses were harvested and weighted as shown by an average tumor weight per group. Results are presented as mean ± SEM, *P <0.05. C, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of different treatment groups (n = 8). D, Schematic of dosing schedule for the testing of lower doses MEKi in syngeneic model. Mice were initiated treament with 0.25, 0.5 or 1 mg/kg of MEKi at 9 days after cell implantation and followed by either addition of anti-PD-L1 mAb or changing of regime at 20 days after cell implantation (n=3–4 per group). E, Synergism of anti-tumor effect by the combinational treatment of lowest MEKi dose with anti-PD-L1 mAbs. F, Body weight changes during the study.

Although the combination with MEKi and immune-checkpoint inhibitor mAbs showed substantially synergism in our in vivo models, however, a single treatment with 1 mg/kg of MEKi also exhibited a significant suppressive effect on tumor growth. We thus questioned whether lower doses of MEKi in combination with anti-PD-L1 mAb also show a synergism of anti-tumor effect. It is important to point out that 1 mg/kg of MEKi is likely a similar dose of patients which, however, showed no therapeutic benefit. In this regard, the validation of lower dose MEKi which would not be shown any anti-tumor effect as a single agent in our model was required to overcome this limitation. Thus, we first tested with various doses of MEKi less than 1 mg/kg as a single treatment using our syngeneic model. Tumor-bearing syngeneic mice were administered with 0.25 or 0.5 mg/kg MEKi for 10 days and followed by modification of this treatment regime to test the combinational effect with anti-PD-L1 mAb (Fig. 4D). We simultaneously monitored tumor growth and body weight every other day (Fig. 4E and 4F). In the period of MEKi as a solo, lower dose of MEKi showed modest suppressive effects on tumor growth but not it was not statistically significance, whereas 1 mg/kg MEKi displayed a significant suppressive effect on tumor growth in consistent with our previous finding (Fig. 4E). Remarkably, combinational treatment of anti-PD-L1 mAb with the lowest dose of MEKi (0.25 mg/kg) exhibited a sufficient anti-tumor effect which was more than 1 mg/kg of MEKi single treatment (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 6). In this study, we did not see any abnormalities of both body weight and behavior of the mice (Fig. 4F).

PMN-MDSC population in the tumor is decreased by the combination of MEKi with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs.

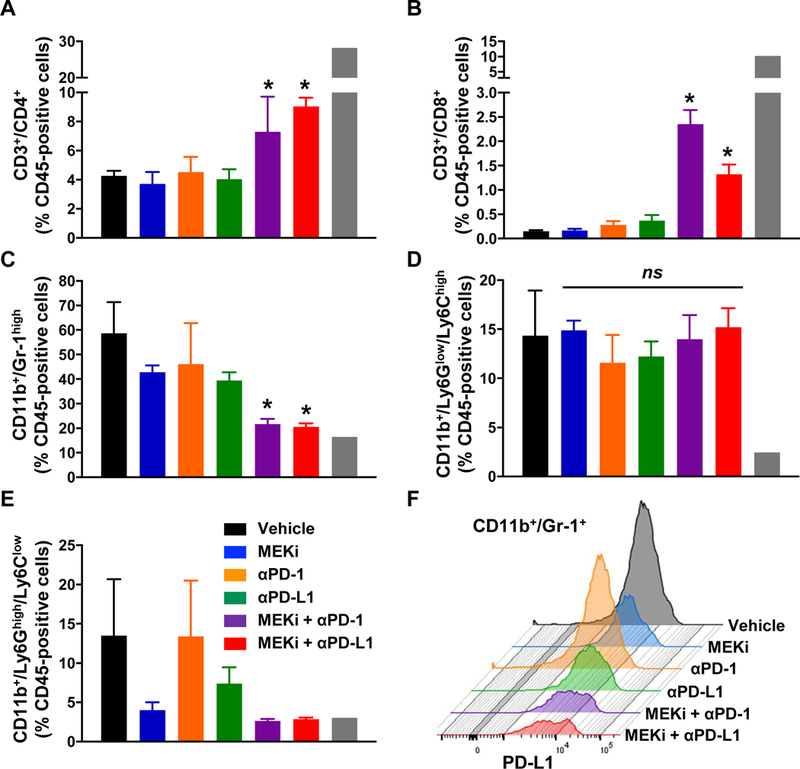

To further determine the effect of PD1/PD-L1 pathway blockade in combination with MEKi in the immune cell composition of the Kras/p53-driven lung tumors, we isolated the infiltrated tumor leukocytes and studied them by flow cytometry. Combination of anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs with MEKi significantly augmented the percentage of CD4+ (MEKi + anti-PD-1: 7.29 ± 2.4 %, MEKi + anti-PD-L1: 9.04 ± 0.6 %; as mean ± SEM) and more profoundly CD8+ T cells (MEKi + anti-PD-1: 2.35 ± 0.28 %, MEKi + anti-PD-L1: 1.32 ± 0.2 %) in the tumor in comparison with vehicle-treated control (4.27. ± 0.34 % and 0.15 ± 0.02 %, respectively), whereas MEKi solo did not increase these populations of CD4+ (3.72 ± 0.81 %) and CD8+ (0.17 ± 0.03 %) T cells in the tumor (Fig. 5A and 5B). Intriguingly, the combination of either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs with MEKi significantly ablated MDSC population (MEKi + anti-PD-1: 21.77 ± 2.00 %, MEKi + anti-PD-L1: 20.6 ± 1.36 %) in the tumor, in particular, the PMN-MDSCs, CD45+/CD11b+/Ly6Ghigh/Ly6Clow (MEKi + anti-PD-1: 2.68 ± 0.19 % and MEKi + anti-PD-L1: 2.89 ± 0.18 %; Fig. 5C and 5E). We did not observe any differences on monocytic-MDSCs as indicated by CD45+/CD11b+/Ly6G-/Ly6Chigh (Fig. 5D). Indeed, there is a dramatic decline in the PD-L1+ MDSCs compartment post-treatment with MEKi and either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs (Fig. 5F). These results suggest that the decreases in MDSCs and PD-L1-positive MDSCs likely lead to the abolishment of immune inhibition, as indicating the increased composition of tumor-infiltrating T cells by the combinational treatment with MEKi plus either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs groups.

Figure 5.

The combinatory therapies of MEKi with either anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 mAbs augment tumor infiltrating T cells and ablate PMN-MDSCs in PKL syngeneic tumor beds. A and B, Flow cytometry quantification of tumor-infiltrating immune cells including CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells in the s.c. tumors. C-E, Flow cytometry quantification of tumor-infiltrating immune cells including CD11b+/Gr-1high total MDSCs (C), CD11b+/Ly6Chigh monocytic MDSCs (D), and CD11b+/Ly6Ghigh PMN-MDSCs (E). (mean ± SEM; n=8; *P <0.05 vs. vehicle and single treatment groups). F, Representative histogram of PD-L1-positive CD11b+;Gr-1+ MDSCs after treatment with combination of MEKi with anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1.

Antitumor effect of the combination of MEKi and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs in PKL-transgenic mice is mediated by MEKi-induced apoptosis and augmentation of tumor-filtrating T cells.

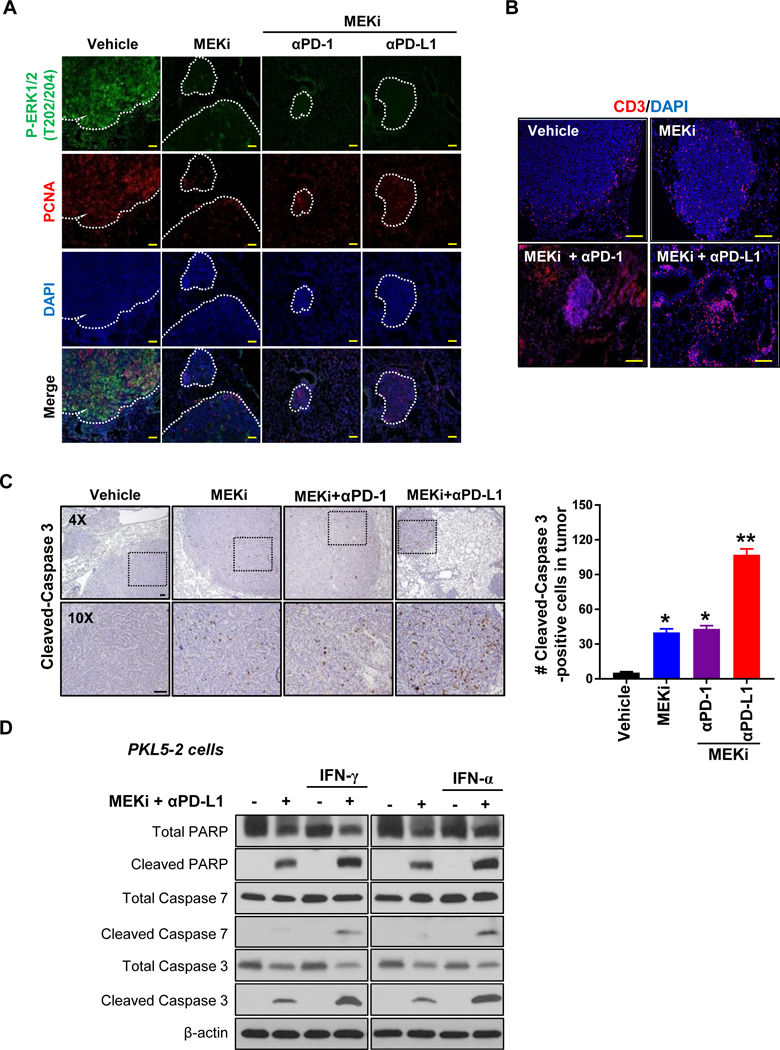

We next tested expressional status of pERK½ in lung tumors, which is a direct downstream of MEK signaling, and a proliferation marker,PCNA, to determine MEKi-mediated inhibitions of MEK signaling and tumor cell proliferation, respectively. In all the treatment groups with MEKi both single and combination, pERK½ expression was almost completely ablated in lung tumors in concomitant with that PCNA was also profoundly decreased, indicating the suppressive effect on tumor proliferation in the setting of MEK inhibition (Fig. 6A). Of note, the majority of the tumors were shrunk by the combination treatment groups. Moreover, in vehicle-treated control tumors, CD3+ T cells were limited to the outer rim of the tumor, whereas MEKi-treated tumor-bearing lungs exhibited infiltration of T cells into the tumor compartment (Fig. 6B). Also, we observed that MEKi treatment not only suppressed tumor proliferation (Fig. 6A), it also induced tumor cell apoptosis, as shown by the augmented expression of cleaved-caspase 3 in tumor bed (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that combinatorial treatment significantly ablated tumor growth and increased tumor-infiltration of T cells.

Figure 6.

The combination of MEKi with either anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies shows a significant decrease in P-ERK whereas increases of highly infiltrated CD3+ T cells and apoptosis in PKL lung tumors. A, Reduction of P-ERK and PCNA in combinatory treated lung tumors as shown double immunofluorescence staining for P-ERK and PCNA. Tumor nodules were marked. B, A significant increase of infiltrated CD3+ T cells in lung tumor treated with MEKi and anti-PD-L1 antibody compared to other groups as shown immunofluorescence staining for CD3. H&E image showed tumor nodules. C, Immunohistochemistry staining for cleaved-caspase 3 in PKL lung tumor treated with the indicated agents. 8 weeks after induction lung tumor by Ad-Cre, mice were administered with MEKi and either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-Ll antibodies for 7 days and followed harvesting lung tumors. The number of cleaved-Caspase 3-positive cells were counted in tumor bed with at least 25 tumor nodules in three individual each group (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005; Scale bar = 100 μm). D, Western blot for cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase 7, and cleaved caspase 3 in PKL 5–2 cells exposed to MEKi and anti-PD-Ll mAb with or without either IFN-γ or IFN-α.

Given the protective role of PD-1/PD-L1 on cancer cells from IFN-mediated cytotoxicity26,27, we examined with PKL5–2 cells to see whether the combinational treatment of MEKi with anti-PD-Ll mAb sensitizes cancer cells to IFN-mediated apoptosis. PKL5–2 cells were exposed to MEKi and anti-PD-Ll mAb with or without either IFN-γ or IFN-α for 24 hours and followed by western blotting with antibodies against apoptotic markers. As expected, IFN-mediated apoptosis was dramatically induced in cells exposed to the combination as shown by increases of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase 7 and cleaved caspase 3 (Fig. 6D). Overall, these results indicate that the combinational treatment of MEKi with antibody-mediated PD-1/PD-L1 blockages synergistically suppresses KRAS-mutated lung tumor growth and also sensitize cancer cells to IFN-mediated cytotoxicity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that a combinatorial treatment with low dose of MEKi, trametinib, and anti-PD-Ll in a KRAS-mutated NSCLC could: 1) enhance T-cell infiltration in both tumor microenvironment and inside tumor bed; 2) decrease the number of Ly6Ghigh PMN-MDSCs in the tumor; and 3) suppress tumor cell proliferation and lead to apoptosis of tumor cells. Therefore, MEKi functioned as a sensitizer of previously unresponsive KRAS-mutated tumors to immunotherapy. There are two ongoing clinical trials relavant to the therapeutic regimen of trametinib and pembrolizumab (NCT 03299088, NCT03225664). To the best of our knowledge, our research is the first preclinical study that could provide rationale for the use of the combination treatment for KRAS-mutated NSCLC.

Many clinical trials have evaluated the possible role of MEKi in KRAS-mutated NSCLC (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3). MEKi as single-agent treatment has revealed a limited efficacy in KRAS-mutated NSCLC 12, 28. Also, the efficacy of MEKi in combination with conventional chemotherapy has been tested in randomized clinical trials 15, 29 However, more than two-thirds of patients treated with the combination treatment were reported to experience grade 3 or higher adverse events. Accordingly, 46%, 28%, and 23% of the group had to receive hospitalization, dose reduction, and discontinuation, respectively, suggesting the needs for dose reduction to complete a full cycle of the combination therapy 15. We observed that a combination of the low dose MEKi with anti-PD-L1 mAb showed a significant synergism of both anti-tumor effect and favorable survival in our mouse model. According to The Food and Drug Administration’s guideline on calculating human equivalent dose, the reduced dose of trametinib used in our research, i.e., 0.25mg/kg/day for the mouse is equivalent to 1.22 mg/day for a human who assumed to weigh 60 kg, which is about half of the conventionally used dose 30.

Some previous studies showed that MEKi provoked adaptive drug resistance in KRAS-mutant lung cancer through fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) signaling, indicating combination of MEKi and FGFRi would be effective 31, 32. Also, there is a clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of atezolizumab combined with cobimetinib in colorectal cancer (NCT02788279). However, they did not consider the need for dose adjustment to reduce drug toxicity-related complication when used in cancer patients. As a matter of fact, treatment-related grade 3–4 adverse events were reported in 45% of patients who received atezolizumab with cobimetinib 33. Our study focused on the potential role of low dose MEKi in modifying the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment by attenuating PMN-MDSCs in the tumor bed, so that checkpoint inhibitors could be more effective. Indeed, we observed that when we added either IFN-γ or IFN-α to the combination treatment, i.e., MEKi, anti-PD-L1 mAb, cytotoxic effect was drastically increased in the cells compared to without IFN exposure. In consistent with other studies26, 27, the combinational treatment of MEKi and antibody-mediated PD-1/PD-L1 blockage sensitizes cancer cells to IFN-mediated apoptosis, suggesting that the combination could inhibit immune escape of cancer cells, at least in part, by synergistic enhancement of sensitivity to interferons and cytotoxic T cells-mediated killing with suppression of MDSC.

The efficacy of immunotherapy in KRAS-mutated NSCLC has not been consistently observed in previous clinical studies (Supplementary Table 4). Subgroup analysis of the CheckMate 057 trial showed that NSCLC patients harboring KRAS mutation were more like to benefit from nivolumab as shown by an improved overall survival compared with patients with wild-type KRAS 34. In contrast, two other clinical studies with immune checkpoint inhibitors showed that KRAS mutational status was not associated with survival benefit 20, 23. Interestingly, a recent study corroborated that STK11/LKB1 alterations function as a major driver of primary resistance to PD-1 blockade in KRAS-mutant NSCLC 35.

Our results implicate that low dose trametinib may degrade tumor burden by apoptosis and be followed by an increase of tumor antigens available which are recognized by T cells to mount anti-tumor T cell response. A recent study showed that MEKi, G-38963 in combination with anti-PD-Ll mAb enhanced T cell activity against KRAS-mutated colon cancer cells in CT-26-mediated syngeneic mouse model 36, 37 In melanoma cell lines, MEK inhibition with trametinib was also shown to increase the expression of apoptosis markers along with expression of HLA molecules 38. Simultaneously, trametinib could modify the suppressive tumor microenvironment by both attenuating MDSCs and enhancing T cell infiltration into the tumor bed. Also, a dose reduction of trametinib may prevent the possible adverse events which were observed in previous clinical trials using MEKi. There is an ongoing clinical trial, of which one of the objectives is to determine the highest tolerable dose of trametinib when given with pembrolizumab for NSCLC (NCT03225664). Together with our study, it is worthwhile to anticipate outcomes from this ongoing trial in order to determine the optimal dose of trametinib for future clinical trial that enables to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of trametinib in combination with pembrolizumab for NSCLC.

Inhibition of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment seems to occur through the conversion of effector cells into potent immunosuppressive cell populations such as regulatory T cells, and MDSCs 39, 40 In mice, MDSCs have been classified as CD11b+ and Gr1+ and are made up of a heterogeneous mixture of immature myeloid cells and myeloid progenitor cells 41–44 Mouse tumor-infiltrating MDSCs have been shown to impair CD8+ T cell response and anti-tumor immune response 41. We found that MEK inhibition by trametinib reduced the accumulation of Ly6G+ MDSCs in the tumor and modified the suppressive tumor microenvironment allowing immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade to properly function.

KRAS-mutated cancer may especially have the propensity to recruit MDSCs. In a mouse pancreatic model, overexpression of constitutive active KRAS led to the expression of MIP-2 and MCP-1, which promoted recruitment of MDSC into the tumor stroma 45. MEK inhibition has been shown to reduce chemokines involved in the recruitment of MDSCs into the tumor and block MDSC differentiation. MEK inhibition with trametinib decreased tumor production of osteopontin, an MDSC chemotactic factor and reduced the recruitment of monocytic Ly6C+ MDSCs into a KRAS-driven breast cancer mouse model and in Lewis lung carcinoma model 46. We, however, did not find any differences in the monocytic MDSC population in our MEKi-treated groups but rather found that MEKi reduced the PMN-MDSCs in our models. This may be due to differences in the tumor model. In addition, trametinib was also able to inhibit MDSC expansion from myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow 47. Similarly, MEK inhibitor U0126 was able to block the IL-11-induced MDSC differentiation 48.

We investigated lung adenocarcinomas carrying common KRAS and/or TP53 mutations because we identified these tumors to be inadequately infiltrated by CD8+ T cells in both humans and mice. As previously described, this model was found to be poorly immunogenic with no CD3+ T cell tumor infiltration 49. In contrast, we found that there was T cell tumor infiltration but limited to the tumor edge in our mouse model. We evaluated if the difference between our models was due to the incorporation of luciferase into our tumor model, which could act as xenoantigen. However, in our model without luciferase, there was also T cell surrounding the tumor (Supplementary Fig. 5A). We postulate that the difference in T cell infiltration into the tumor may be due to the differences in the genetic background of the mouse models used. Pfirschke et al. used a mouse model on B6 or 129 backgrounds, which are of MHC haplotype b, whereas our mice were on FVB background, which is of MHC haplotype q (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Despite the difference in the level of T cell infiltration, our model remained poorly immunogenic and did not respond to single-agent immunotherapy treatment with either PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade.

In conclusion, this study expands upon the emerging targeted therapy of MEK inhibition in KRAS-mutated NSCLC with trametinib by demonstrating synergistic anti-tumor effect in combination with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs immunotherapies. This should prompt further investigation into this potential breakthrough in the treatment of the largest genotype subset of NSCLC, a leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States and worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant P50CA196530 (Yale SPORE in Lung Cancer to R.S.H., L.C., J.S.K.), R01-CA126801 (to J.S.K), and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant CA-16359 (to Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick F The potential of targeting Ras proteins in lung cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2015;19:451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick F K-Ras protein as a drug target. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94:253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell 2017;170:17–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 2018;553:446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay CR, Jamal-Hanjani M, Forster M, et al. KRAS: Reasons for optimism in lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2018;99:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aredo JV, Padda SK. Management of KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Era of Precision Medicine. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2018;19:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, et al. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for Efficient Patient Matching to Approved and Emerging Therapies. Cancer Discov 2017;7:596–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014;511:543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okumura S, Janne PA. Molecular Pathways: The Basis for Rational Combination Using MEK Inhibitors in KRAS-Mutant Cancers. Clinical Cancer Research 2014;20:4193–4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenschein GR Jr., Smit EF, Planchard D, et al. A randomized phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) compared with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)dagger. Ann Oncol 2015;26:894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hainsworth JD, Cebotaru CL, Kanarev V, et al. A phase II, open-label, randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus pemetrexed in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1630–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janne PA, Mann H, Ghiorghiu D. Study Design and Rationale for a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Selumetinib in Combination With Docetaxel as Second-Line Treatment in Patients With KRAS-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (SELECT-1). Clin Lung Cancer 2016;17:e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janne PA, van den Heuvel MM, Barlesi F, et al. Selumetinib Plus Docetaxel Compared With Docetaxel Alone and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With KRAS-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The SELECT-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2017;317:1844–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sznol M, Chen L. Antagonist antibodies to PD-1 and B7-H1 (PD-L1) in the treatment of advanced human cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:1021–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He J, Hu Y, Hu M, et al. Development of PD-1/PD-L1 Pathway in Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Treatment for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Sci Rep 2015;5:13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1837–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lastwika KJ, Wilson W 3rd, Li QK, et al. Control of PD-L1 Expression by Oncogenic Activation of the AKT-mTOR Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2016;76:227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen N, Fang W, Lin Z, et al. KRAS mutation-induced upregulation of PD-L1 mediates immune escape in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017;66:1175–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1064–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JW, Park HS, Park SA, et al. A Novel Small-Molecule Inhibitor Targeting CREB-CBP Complex Possesses Anti-Cancer Effects along with Cell Cycle Regulation, Autophagy Suppression and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gato-Canas M, Zuazo M, Arasanz H, et al. PDL1 Signals through Conserved Sequence Motifs to Overcome Interferon-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Cell Rep 2017;20:1818–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK½ Mutations. Cancer Discov 2017;7:188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter CA, Rajan A, Keen C, et al. Selumetinib with and without erlotinib in KRAS mutant and KRAS wild-type advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2016;27:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm 2016;7:27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitai H, Ebi H, Tomida S, et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Defines Feedback Activation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling Induced by MEK Inhibition in KRAS-Mutant Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:754–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchado E, Weissmueller S, Morris JPt, et al. A combinatorial strategy for treating KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nature 2016;534:647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NABendell J, Ciardiello F, Tabernero J, et al. LBA-004Efficacy and safety results from IMblaze370, a randomised Phase III study comparing atezolizumab+cobimetinib and atezolizumab monotherapy vs regorafenib in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology 2018;29:mdy208.003-mdy208.003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1627–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebert PJ, Cheung J, Yang Y, et al. MAP Kinase Inhibition Promotes T Cell and Anti-tumor Activity in Combination with PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade. Immunity 2016;44:609–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Mayes PA, Eastman S, et al. The BRAF and MEK Inhibitors Dabrafenib and Trametinib: Effects on Immune Function and in Combination with Immunomodulatory Antibodies Targeting PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1639–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson DB, Estrada MV, Salgado R, et al. Melanoma-specific MHC-II expression represents a tumour-autonomous phenotype and predicts response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Nat Commun 2016;7:10582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindau D, Gielen P, Kroesen M, et al. The immunosuppressive tumour network: myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells. Immunology 2013;138:105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:253–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youn JI, Gabrilovich DI. The biology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells: the blessing and the curse of morphological and functional heterogeneity. Eur J Immunol 2010;40:2969–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:162–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabrilovich DI, Bronte V, Chen SH, et al. The terminology issue for myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2007;67:425; author reply 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2006;55:237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ji H, Houghton AM, Mariani TJ, et al. K-ras activation generates an inflammatory response in lung tumors. Oncogene 2006;25:2105–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allegrezza MJ, Rutkowski MR, Stephen TL, et al. Trametinib Drives T-cell-Dependent Control of KRAS-Mutated Tumors by Inhibiting Pathological Myelopoiesis. Cancer Res 2016;76:6253–6265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu-Lieskovan S, Mok S, Homet Moreno B, et al. Improved antitumor activity of immunotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF(V600E) melanoma. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:279ra–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kentaro Sumida YO, Junya Ohtake, Shun Kaneumi, Takuto Kishikawa, Norihiko Takahashi, Akinobu Taketomi, Hidemitsu Kitamura. IL-11 induces differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells through activation of STAT3 signalling pathway. Sci Rep 2015;5:13650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfirschke C, Engblom C, Rickelt S, et al. Immunogenic Chemotherapy Sensitizes Tumors to Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Immunity 2016;44:343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.