Abstract

Fibrosis, or the accumulation of extracellular matrix molecules that make up scar tissue, is a common result of chronic tissue injury. Advances in the clinical management of fibrotic diseases have been hampered by the low sensitivity and specificity of non-invasive early diagnostic options, lack of surrogate endpoints for use in clinical trials, and a paucity of non-invasive tools to assess fibrotic disease activity longitudinally. Hence, the development of new methods to image fibrosis and fibrogenesis is a large unmet clinical need. Herein we provide an overview of recent and selected molecular probes for imaging of fibrosis and fibrogenesis by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Keywords: Fibrosis, Fibrogenesis, Molecular Imaging, Targeted Probes, Collagen

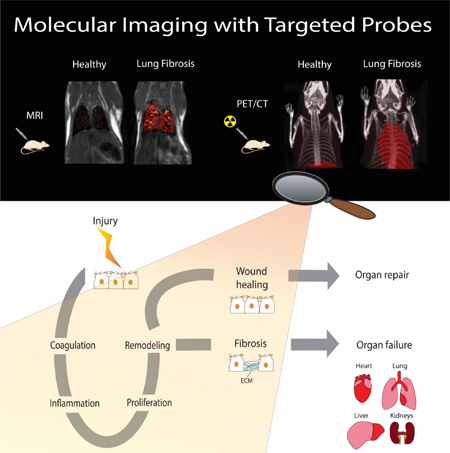

Graphical Abstract

Fibrogenesis is the production of extracellular matrix in response to chronic tissue injury leading to the accumulation of scar tissue and eventually to organ failure and death. Here, we examined the molecular processes involved in the development of fibrosis, identified targets and processes that can be non invasively imaged, and provided insight into the available molecular probes for fibrosis and fibrogenesis imaging.

1. Introduction

Organ fibrosis is the result of maladaptive wound healing responses to ongoing tissue injury resulting in excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and tissue remodeling.[1] If progressive, fibrosis can lead to organ failure and ultimately death. Pulmonary fibrosis,[2] hepatic cirrhosis,[3] hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,[4] diabetic nephropathy[5], and atherosclerosis[6] are among the most common diseases characterized by tissue fibrosis. Fibrotic diseases account for nearly half of the deaths in the industrialized world and represent an enormous unmet medical challenge due to the lack of effective therapies.[7]

Lung fibrosis is associated with a broad category of lung diseases with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) being the most fatal. IPF is a chronic and progressive disease with an estimated prevalence of 20 cases per 100,000.[8] Liver cirrhosis, which can result from conditions including hepatitis viruses, alcohol, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), effects an estimated 2–5% of Americans.[9] Kidney fibrosis commonly occurs in glomerulonephritis and diabetic nephropathy.[5] The number of patients requiring dialysis due to diabetic nephropathy is increasing year by year and the cost of dialysis represents a considerable medical expense in advanced countries. Fibrosis of the heart occurs in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy[10] and can develop after myocardial infarction.[11] Atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction can result from atrial[12] and vascular fibrosis, respectively. Fibrosis occurs in joints, bone marrow, eyes, intestines, pancreas, skin and vessels[6] and is also associated with invasion of tumors[13] and development of metastasis.[14]

Given the prevalence and severity of fibrotic diseases, the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of fibrosis remains a major clinical challenge. At the current time, the management of patients with fibrotic diseases is complicated by the absence of non-invasive imaging methods to facilitate early diagnosis, to assess disease activity and predict progression, and to provide early assessments of patient responses to novel therapies being developed. Tissue sampling can provide important information, but the increased risk of complications renders repeated biopsies to evaluate disease progression or response to treatment a suboptimal strategy.

There has been considerable effort to non-invasively detect and stage fibrosis, e.g. with high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) in the lung;[15] magnetic resonance (MR) imaging late gadolinium enhancement[16] and extracellular volume mapping in the heart;[17] and ultrasound[18] or MR elastography[19] methods in the liver. However, none of these methods are sensitive to early changes in disease and there is no technique that can noninvasively distinguish or quantify disease activity (fibrogenesis). Fibrosis and fibrogenesis imaging may have a major positive impact on patient care. In this review, we will examine the molecular processes involved in the development of fibrosis, identify targets and processes that can be noninvasively imaged, and provide insight into the available molecular probes for fibrosis and fibrogenesis imaging.

2. Molecular Processes Involved inTissue Inflammation and Fibrosis

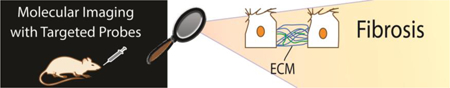

Organ injury triggers a cascade of cellular and molecular wound healing responses.[20] Wound healing can ultimately result in either tissue regeneration or organ fibrosis depending on the degree of wound healing responses (Figure 1). After injury, the first phases of wound healing are characterized by increased vascular permeability and extravascular coagulation.[2] After injury, epithelial and/or endothelial cells release inflammatory mediators, which initiate the coagulation cascade.[21] The circulating platelets are rapidly recruited and activated upon encountering exposed collagen and von Willebrandt factor. Due to platelet degranulation, vasodilation is promoted and blood vessel permeability increases. The proteolytic cleavage of prothrombin, also known as coagulation factor II, forms thrombin. Thrombin converts soluble fibrinogen into soluble strands of fibrin, which helps platelets clump together to form the fibrin clot that ensure hemostasis.[22] Stimulated epithelial and endothelial cells produce matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs). The MMPs disrupt the basement membrane, which allows the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of injury. As part of this inflammatory phase, growth factors, cytokines and chemokines are produced and initiate the healing response by stimulating the proliferation and recruitment of leukocytes. Leukocytes produce additional cytokines and growth factors, interleukin 13 (IL-13), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), activating macrophages and fibroblasts.[22] The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is also produced and induces angiogenesis. Activated macrophages and neutrophils clean up tissue debris and dead cells. Activated fibroblasts transform into myofibroblasts as they migrate into the wound and deposit new connective tissue (collagen type I, fibronectin, elastin).[23] Following activation, the myofibroblasts promote contraction of the wound. Collagen fibers start forming crosslinks by the action of the lysyl oxidase enzymes (LOX, LOXL2).[24] The new collagen matrix becomes organized during the remodeling phase. After restoration of the blood vessels, the scar tissue is eliminated and cells (epithelial and endothelial cells) divide and migrate regenerating tissues.

Figure 1.

Molecular processes involved in wound repair and fibrosis. Adapted with permission from Wynn J. Clin. Invest. 117:524–529 (2007).[26]

In chronic inflammation and repair, however, formation of fibrosis can result due to persistent myofibroblast activation and increased collagen crosslinking. Any shift in the synthesis versus elimination of ECM can shift the balance towards scar formation. Fibrosis occurs when the generation of new collagen exceeds the rate at which it is degraded.[25]

3. Molecular Imaging of Fibrosis and Fibrogenesis

Molecular imaging is the in vivo characterization and measurement of cellular and molecular processes.[26] Molecular imaging requires target identification and validation with high affinity probes. Probes can be small molecules (receptor ligands, enzyme substrate) or higher molecular weight affinity ligands (peptides, monoclonal antibodies, recombinant proteins). Different imaging modalities such as MR imaging, ultrasound, optical imaging and nuclear imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can be used.

There is no one ideal molecular imaging technique and each methodology brings its own strengths and weaknesses. MRI has the benefits of relatively high spatial resolution (down to 0.01 mm), can image deep into tissue, does not require ionizing radiation, uses shelf-stable molecular probes, and can provide additional image contrasts that yield anatomical and functional information in addition to the molecular image. Using nanoparticles, nanomolar concentrations can readily be detected, while small molecules typically require micromolar concentrations for detection. X-ray methods like computed tomography provide even higher resolution and are not limited by tissue depth, however soft tissue contrast is poor and for molecular imaging extremely high concentrations (mM) are required for detection. On the other hand, nuclear techniques like SPECT and PET have exquisite sensitivity for detection (pM) and can also image deep into tissue. But compared to MRI or CT, the spatial resolution is much lower (0.5 – 10 mm). Because of the short half-lives involved, PET and SPECT probes must be synthesized on demand and also result in radiation exposure. The infrastructure for MRI, CT, PET, and SPECT is also expensive. Ultrasound approaches are low cost, portable, and widely available but operator-dependent. They demonstrate high spatial resolution but have limited depth penetration. Ultrasound contrast agents are based on micron sized particles that are echogenic, e.g. gas filled, and the particle size limits delivery outside the vascular system. Optical imaging approaches (fluorescence imaging and near infrared fluorescence imaging) are excellent research tools, because of their potential high sensitivity, high spatial resolution, and low cost, but the low depth of penetration (<1 cm) limits their use in clinic to superficial, intraoperative, or semi-invasive (catheter or endoscope) applications. The low absorption and tissue autofluorescence in the near-infrared range has led to a growing interest in near infrared fluorescence for in vivo imaging to minimize background interference and to improve tissue depth penetration and image sensitivity. Given the forgoing, one can appreciate that hybrid imaging modalities like PET-MRI can be useful to overcome some of the limitations described above.

Direct molecular imaging with probes that target the components involved in fibrosis and fibrogenesis offers an innovative approach, with potential high specificity, to expand the diagnostic capabilities of current imaging methods. To date several targets have been explored for fibrosis and fibrogenesis imaging such as activated fibroblasts, activated macrophages and other markers of inflammation, integrins, MMPs, and ECM proteins such as fibrin, fibronectin, type I collagen synthesis, type I collagen overexpression, oxidized collagen overexpression and elastin, (Table 1).

Table 1.

Molecular imaging agents for fibrosis and fibrogenesis imaging.

| Imaging agents | Modalities | Biological Targets |

Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMV101 | PET/optical imaging | Activated macrophages | Pulmonary fibrosis[31] |

| 18F-FEDAC | PET | Translocator protein (HSCs) | Liver fibrosis[32] |

| EP-2104R | MRI | Fibrin | Pulmonary fibrosis[37] |

| Gd-P | MRI | Fibrin/fibronectin complex | Liver fibrosis[39] |

| 99mTc-RP805 | SPECT | MMP-2 | MI,[40–42] atherosclerosis[43] |

| Enzyme-activated NIRF probe | Optical imaging | MMP-2/MMP-9 | MI[44] |

| 111In-Octreotide | SPECT | SSTR (Fibroblasts) | Pulmonary fibrosis[47] |

| 68Ga-DOTANOC | PET | SSTR (Fibroblasts) | Pulmonary fibrosis[48] |

| 99mTc-GlcNAc-PEI | SPECT | Integrin αvβ6 | Liver fibrosis[51] |

| 111In-DTPA-A20FMDV2 | SPECT | Integrin αvβ3 (HSCs) | Pulmonary fibrosis[57] |

| 99mTc-3PRGD2 | SPECT | Integrin αvβ3 (HSCs) | Liver fibrosis[59a] |

| c(RGDyC)-USPIO | MRI | Type I collagen | Liver fibrosis[60] |

| EP-3533 | MRI | Type I collagen | MI,[65] myocardial perfusion,[67] liver fibrosis,[68–69] pulmonary fibrosis[37b] |

| CM-101 | MRI | Type I collagen | Liver fibrosis[70] |

| 99mTc-collagelin | SPECT | Type I/III collagen | MI, Pulmonary fibrosis[72] |

| [68Ga]Ga-NO2A-Col | PET | Type I/III collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[73] |

| [68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-CoL | PET | Type I/III collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[73] |

| 99mTc-CBP1495 | SPECT | Type I collagen | Liver and pulmonary fibrosis[74] |

| 64Cu-CBP7 | PET | Type I collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[78] |

| Al18F-CBP9 | PET | Type I collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[80] |

| Al18F-CBP10 | PET | Type I collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[80] |

| 68Ga-CBP8 | PET | Type I collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[81] |

| Gd-Hyd | MRI | Oxidised collagen | Liver and pulmonary fibrosis[84] |

| Gd-OA | MRI | Oxidised collagen | Pulmonary fibrosis[85] |

| F-CHP | Optical imaging | Collagen remodeling | MI and pulmonary fibrosis[86] |

| Gd-ESMA | MRI | Elastin | Atherosclerosis,[17, 87] artherial thrombi,[88] MI,[89] liver fibrosis[90b] |

3.1. Macrophages Imaging / Inflammatory Cell Imaging

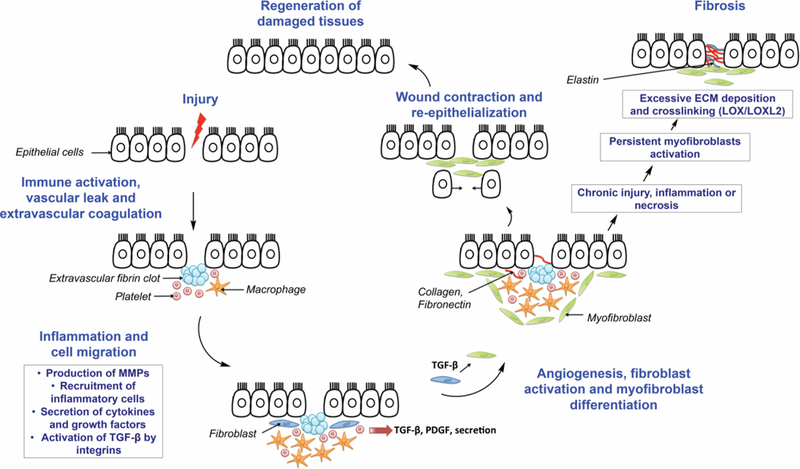

Activated macrophages are involved in IPF pathogenesis.[27] Cysteine cathepsins are a group of protases with elastinolytic and collagenolytic activities that are involved in several aspects of ECM modeling.[28] They are highly expressed in activated macrophages and their activity is upregulated in activated alveolar macrophages during tissue regeneration and modeling.[27] Reagents based on small molecules were developed to assess cysteine cathepsin activity.[29] These reagents form activity-dependent covalent bonds with protease active site nucleophiles. Activity-based probes targeting cysteine cathepsins have electrophilic moieties such 2,6-dimethylbenzoic acid-derived acyloxymethyl ketone (GB123, BMV109) or phenoxymethylketones (BMV101), Figure 2.[30] The dual optical –PET probe (BMV101) was used to monitor the macrophages activity in a mouse model and human patients. In three patients with IPF, probes BMV101 accumulated in fibrotic lung regions. In the lungs of unclassified fibrosis patients, the probe did not show significant accumulation. However, researchers reported on several limitations of the tracer, including relatively high PET signal in the liver and blood.

Figure 2.

Molecular imaging agents targeting macrophages, fibrin, matrix metalloproteinases, fibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells. (Napht = naphthalene)

A translocator protein specific radiotracer has also been developed to image fibrosis. The translocator protein is a receptor complex predominately expressed in macrophages and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). The accumulation of the translocator protein specific radiotracer ([18F]FEDAC (N-benzyl-N-methyl-2-[7,8-dihydro-7-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-8-oxo-2-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl]-acetamide), Figure 2) correlated with the degree of injury in a carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced rat model of liver fibrosis.[31]

3.2. Extravascular and Coagulation Pathway Imaging

During fibrosis, the leaky endothelium results in fibrinogen and other plasma proteins extravasating into the extravascular, extracellular space resulting in fibrin deposition.[32] We developed a gadolinium (Gd)-based, fibrin-binding molecular probe EP-2104R (Figure 2) which comprises an 11 amino acid peptide derivative with 2 GdDOTA-like moieties at the C- and N-terminus of the peptide.[33] EP-2104R was shown to have high specificity for fibrin compared with fibrinogen, and to be a sensitive method for detecting intravascular thrombi with MRI.[33–34] Using ultrashort echo time magnetic resonance imaging (UTE-MRI)[35] of the lungs combined with EP-2104R, we directly assessed fibrin deposition in the lung using a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis associated with vascular leak.[36] We showed that that fibrin imaging of the lung was an effective noninvasive means to detect the extent of fibrin deposition and to monitor response to drug therapy.

In extravascular coagulation matrix fibrin-fibronectin complexes also form, as has been demonstrated in liver fibrosis.[37] A gadolinium-based nanoglobular contrast agent that specifically detects fibronectin-fibrin complexes (termed Gd–P) was shown to detect liver fibrosis in CCl4-injured mice.[38] Nanoglobules are lysine dendrimers with a core made of cubic silsesquioxane. They are compact and globular with a high functionality for conjugation. This makes them ideal for making targeted contrast agents that have a high peptide to Gd(III) chelate ratios.[39] In the case of Gd-P, Gd-DOTA and the cyclic decapeptide CGLIIQKNEC were conjugated on the surface of the nanoglobules. Eventhough Gd-P was able to detect liver fibrosis in a mouse model, its usage was limited in terms of staging disease as Gd-P could not distinguish mice injured with CCl4 for 4 weeks from those injured with CCl4 for 8 weeks.

3.3. Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinases

Matrix metalloproteinases are attractive targets for fibrosis imaging because of their role in ECM remodeling and collagen turnover. 99mTc-RP805 (Figure 2) is a radiolabeled MMP-2 inhibitor and showed a nearly 3-fold higher signal in the infarcted area of mice hearts, one week after myocardial infarction (MI).[40] 99mTc-RP805 was also able to image MMP activity in infarcted areas in dog hearts[41] and in pig models[42] of MI. 99mTc-RP805 has also been successfully used to visualize atherosclerotic plaques in mouse and rabbit models of atherosclerosis.[43] However, clinical translation of 99mTc-RP805 is limited because of its relatively slow blood clearance.

A near infra-red activatable fluorescent probe was developed to detect expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in the heart after MI.[44] The probe is composed with a poly-L-lysine backbone conjugated to a multiple of NIRF Cy5.5 dye molecules attached to the peptide recognition sequence. The close spatial proximity of the multiple Cy5.5 units led to fluorescence quenching in the bound state. Upon enzymatic cleavage by MMP2 and MMP9, the released peptide fragments resulted in fluorescence signal amplification. Imaging with this probe was able to monitor MMP activity during the myocardial remodeling process in mice.

3.4. Fibroblast Imaging

Animal models of pulmonary fibrosis demonstrate increased somatostatin receptor (SSTR) expression on fibroblasts[45] and prompted the application of the SSTR imaging probes. Positive SSTR scintigraphy findings in IPF cases have been shown to correlate with disease progression using a somatostatin analogue conjugated to diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) for In-111 chelation (111In-Octreotide, Figure 2).[46] SSTR imaging was also performed in IPF patients using 68Ga-DOTANOC (Figure 2) PET to detect activated fibroblasts. Maximal standardized uptake values correlated linearly with disease extent as quantified by HRCT.[47]

3.5. Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells Imaging

The expression of desmin and vimentin is upregulated in activated HSCs.[48] A fluorescent probe[49] and more recently a SPECT probe called 99mTc-GlcNAc-PEI[50] (Figure 2) were developed using polymers bearing N-acetylglucosamine (GlNAc) that demonstrated high affinity for desmin and vimentin. The radiotracer 99mTc-GlcNAc-PEI could detect liver fibrosis 4 weeks after CCl4 treatment in a mouse model. However, the researchers reported a very high unspecific uptake of 99mTc-GlcNAc-PEI in the spleen, which might limit its use in clinical settings.

3.6. Integrin imaging

Secreted TGF-β is one of the major pro-fibrogenic cytokines and mediators of fibrosis. The molecular pathways that regulate TGF-β activity and signaling are therefore attractive targets for fibrosis imaging.[51] TGF-β activation by the integrin αvβ6 plays an important role in models of fibrosis in the lungs,[52] biliary tract,[53] liver[54] and kidney.[55] The expression of integrin αvβ3 is also upregulated and markedly increased at the advanced stage of liver fibrosis.[56] Both integrin αvβ6 and integrin αvβ3 have been used as targets for imaging fibrosis in several organs.

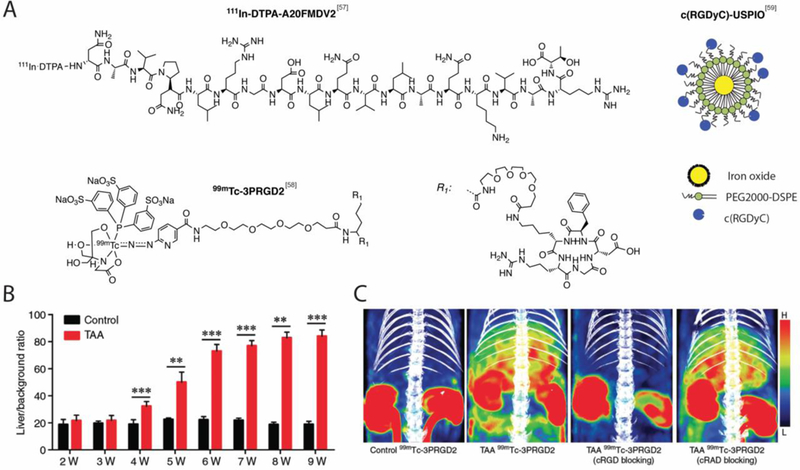

A successful attempt to specifically target integrin αvβ6 used the A20FMDV2 peptide, derived from the VP1 coat protein of the foot-and-mouth disease virus. A20FMDV2 has been shown to be over 1000-fold more selective to αvβ6 integrin than other αv integrins.[56] The peptide was conjugated to DTPA and labeled with In-111 (Figure 3A). Stability of the radiotracer 111In-DTPA-A20FMDV2 was tested in mouse serum.[56] Only 50% of the probe was still intact after 4 hr incubation. 111In-DTPA-A20FMDV2 was also used to measure αvβ6 expression by SPECT-CT in the bleomycin mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis. The authors showed a positive correlation between radiotracer uptake and hydroxyproline, αvβ6 protein and itgb6 messenger RNA levels in mouse lung.[57] Despite low stability, 111In-DTPA-A20FMDV2 could be used for molecular stratification of IPF patients.

Figure 3. Molecular imaging agents for fibrosis detection by targeting integrins.

A. Structure of 111InDTPA-A20FMDV2, c(RGDyC)-USPIO and 99mTc-3PRGD2. B. SPECT activity values in rats treated with thioacetamide (TAA) and control demonstrating that 99mTc-3PRGD2 can monitor fibrosis progression by targeting αvβ3 overexpression as early as week 4 in the TAA-induced rat model of liver fibrosis. Bar chart shows mean liver-to-background radioactivity per unit volume ratio. **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001. C. Representative SPECT/CT images showing significant tracer uptake in fibrotic liver (TAA-treated rats) but not in control and showing predominant uptake of 99mTc-3PRGD2 in the kidneys of both TAA-treated rats and control. Co-injection of a cold integrin αvβ3-specific cyclic RGD peptide (c(RGDfK) with 99mTc-3PRGD2 resulted in a significantly reduced liver-to-background uptake ratio which confirmed the specificity of the radiotracer for αvβ3 overexpression. No reduction was seen after co-injection of 99mTc-3PRGD2 with an irrelevant peptide (c(RADfK). Panels B and C from Yu Radiology. 279:502–512 (2015).[59a]

Fibrosis imaging of αvβ3 overexpression was achieved by using cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) peptides labeled with Tc-99m for SPECT imaging.[58] The radiotracer 99mTc-3PRGD2 (Figure 3A) was used to monitor the progression of fibrosis in the thioacetamide (TAA) induced rat model of liver fibrosis. Authors demonstrated that 99mTc-3PRGD2 allows detection of fibrosis as early as week 4 (Figure 3B). The expression of αvβ3 integrins on HSCs, as determined by 99mTc-3PRGD2, correlated with fibrosis stage. Specificity of 99mTc-3PRGD2 for αvβ3 overexpression was also confirmed by blocking experiments (Figure 3C). The co-injection of a cold integrin αvβ3-specific cyclic RGD peptide (c(RGDfK) with 99mTc-3PRGD2 resulted in a significantly reduced liver-to-background uptake ratio whereas the co-injection of a cold and irrelevant peptide (c(RADfK) had no effect on the liver-to-background uptake ratio. Radiotracer 99mTc-3PRGD2 SPECT/CT also showed efficacy in monitoring antifibrotic therapy.

Similarly, RGD peptides were used to modify ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (SPION) to develop MR T2 contrast agents (Figure 3A).[59] Here, the iron particles were engulfed by activated HSCs in a mouse model of liver fibrosis resulting in reduction of signal intensity and shortening of T2 relaxation times subject to the paramagnetic effect of the particles.[58] However, the researchers reported unspecific uptake of SPION particles by Kuffer cells (the resident macrophages of liver), which is an obvious limitation.

4. Targeting Collagen and Elastin Overexpession

Collagen type I is a hallmark of fibrosis.[21] Type I collagen deposition is a very attractive target because of its specificity for fibrosis across tissue and organ types. Type I collagen concentration is above 10 μM in fibrotic tissue, making this a target compatible with most imaging modalities.[60] Several probes have been developed to molecularly image changes in collagen expression during fibrosis. Elastin accumulation occurs later in fibrosis and has also been used as a target to image fibrosis.

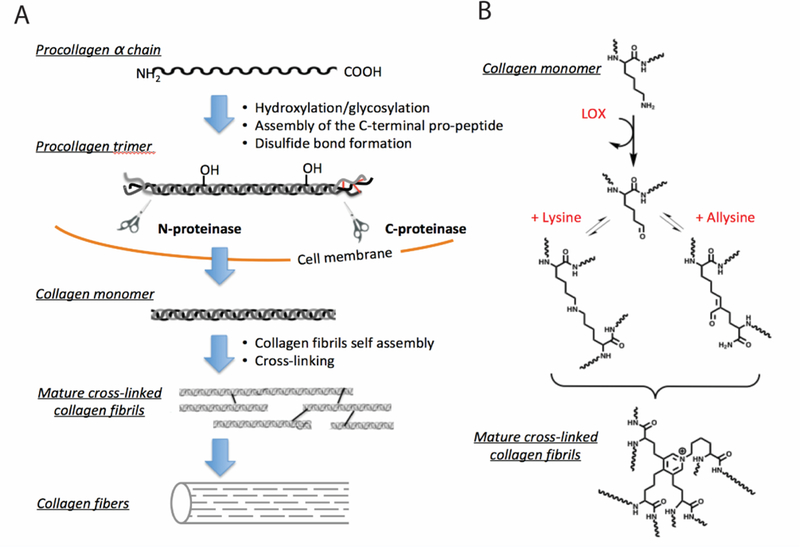

4.1. Mechanism of Collagen Synthesis and Cross-linking

Collagen type I is intracellularly synthesized in fibroblasts in a precursor form, called pre-pro-collagen (Figure 4A).[61] Pre-pro-collagen strands contain mainly glycine (approximately one third of the amino acid content), proline and lysine (both approximately one sixth of the amino acid content).[62] Some of the proline and lysine residues undergo hydroxylation reaction, which leads to the formation of hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine respectively. Hydroxylysine residues can also be modified by glycosylation with galactose or galactosyl-glucose through an O-glycosidic linkage.

Figure 4.

A. Collagen synthesis pathway. Secretion of pro-collagen and self-assembly is followed by the cleavage of the N- and C-termini of the pro-collagen trimer. The resulting collagen monomers are released in the extracellular matrix, aggregate into collagen fibrils and form covalent crosslinks, leading to collagen fibers formation. B. Mechanism of collagen crosslinking. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) catalyses collagen cross-linking.[63]

After hydroxylation and glycosylation, the pro-α chains form the pro-collagen molecule. The pro-collagen molecule contains polypeptide extensions with cysteine residues at both terminal ends. Three pro-collagen molecules assemble via disulfide bonds to form a triple helix winding from the carboxyl terminal end. After cleavage of the polypeptide extensions by extracellular enzyme, the triple helical mature collagen monomers are released in the ECM and spontaneously, aggregate into collagen fibrils. Preceding collagen cross-linking, lysyloxidase (LOX) and LOX-like (Loxl-n) enzymes are upregulated[24a] and oxidize the εamino groups of certain lysine and hydroxylysine residues to the aldehyde allysine (Figure 4B).[62–63] During fibrogenesis, the high concentration and catalytic activity of lysyl oxidases results in the abundance of allysine. Allysine is generated during fibrogenesis but in a stable or treated disease, allysine is converted to crosslinks. Allysine can react with other lysine and hydroxylysine-derived aldehydes to form aldol condensation products. Allysine can also form Schiff bases with the ε-amino groups of unoxidised lysine or hydroxylysines. Histidine is also involved in certain crosslinks. These reactions, after further rearrangements, result in stable, irreversible covalent cross-links.

4.2. Targeting Collagen for Imaging Fibrosis

4.2.1. MR imaging

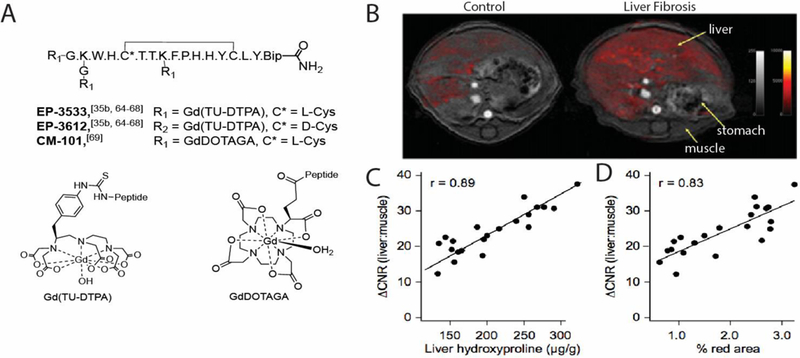

We previously reported a 16-amino acid disulfide-bridged cyclic peptide that was identified via phage display to recognize type I human collagen. This peptide was functionalized with 3 GdDTPA chelators (Figure 5A) to provide MRI signal enhancement.[64] This compound, EP-3533 (Figure 5A), binds type I collagen reversibly (Kd = 1.8 µM) and non-saturably. The isomeric compound EP-3612 (Figure 5A), where one L-cysteine was replaced by D-cysteine, had over 100-fold lower affinity for collagen. In a mouse model of aged myocardial scar, we showed that EP-3533 showed prolonged MR enhancement of the collagen rich scar, while the non-binding isomer EP-3612 showed no such enhancement.[64–65] Ex vivo analyses of the heart and blood for Gd content indicated that there was >2X Gd in the infarct zone relative to remote myocardium 1 hour after injection and 5X more Gd in the infarct than in the blood. In addition to myocardial fibrosis, we have demonstrated that the probe can be used to target normal myocardium for a steady state myocardial perfusion application.[66]

Figure 5.

A. Structures of the collagen-targeted MR imaging probes EP-3533 and CM-101 for fibrosis imaging. EP3612 is the non-binding isomer of EP-3533 where one L-cysteine was replaced by D-cysteine (Bip = biphenylalanine). B. Representative axial MR images of a control and fibrotic mouse demonstrating that EP-3533 enhanced MRI can detect CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. False color overlay is the difference image between post- and pre-injection images of EP-3533. Both images rendered at the same scale. C. MR signal change (ΔCNR) as expressed as the change in contrast between liver and muscle linearly correlated with total collagen (hydroxyproline). D. MR signal change (ΔCNR) as expressed as the change in contrast between liver and muscle linearly correlated with histological characterization (Sirius Red quantification). Panels B-D from Fuchs J. Hepatol. 59:992–998 (2013).[69a]

EP-3533 was also demonstrated to be effective for detecting liver fibrosis.[67] We imaged animals that were given CCl4 over a period of weeks to induce hepatic fibrosis (Figure 5B). We found that MR signal change as expressed as the change in contrast between liver and muscle linearly correlated with hydroxyproline (total collagen, Figure 5C) concentration and with histopathological characterization (Sirius Red quantification, Figure 5D). We subsequently demonstrated that the probe could quantitatively stage fibrosis in multiple animal models of liver fibrosis[68] and assess response to antifibrotic therapies with high lysyloxidase (LOX) and LOX-like (Loxl-n) enzymes are upregulated[24a] and oxidize the εamino groups of certain lysine and hydroxylysine residues to the aldehyde allysine (Figure 5C) concentration and with histopathological characterization (Sirius Red quantification, Figure 5D). We subsequently demonstrated that the probe could quantitatively stage fibrosis in multiple animal models of liver fibrosis[67] and assess response to antifibrotic therapies with highsensitivity and specificity.[68b, 68c] EP-3533 MRI was also effective at detecting fibrosis in the lung. We showed that it (but not its non-binding isomer control) could detect pulmonary fibrosis in the bleomycin model and that probe uptake and MRI signal correlated linearly with the amount of fibrosis assessed by hydroxyproline.[35b]

More recently, we developed CM-101 (Figure 5A) using the same collagen-targeting mechanism but employing the much more stable macrocyclic chelate Gd-DOTA (Figure 5A) to facilitate clinical translation.[69] Less stable, linear gadolinium-contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients.[70] Molecular MR imaging with the collagen-targeted probe CM-101 provided robust detection of liver fibrosis in two animal models.

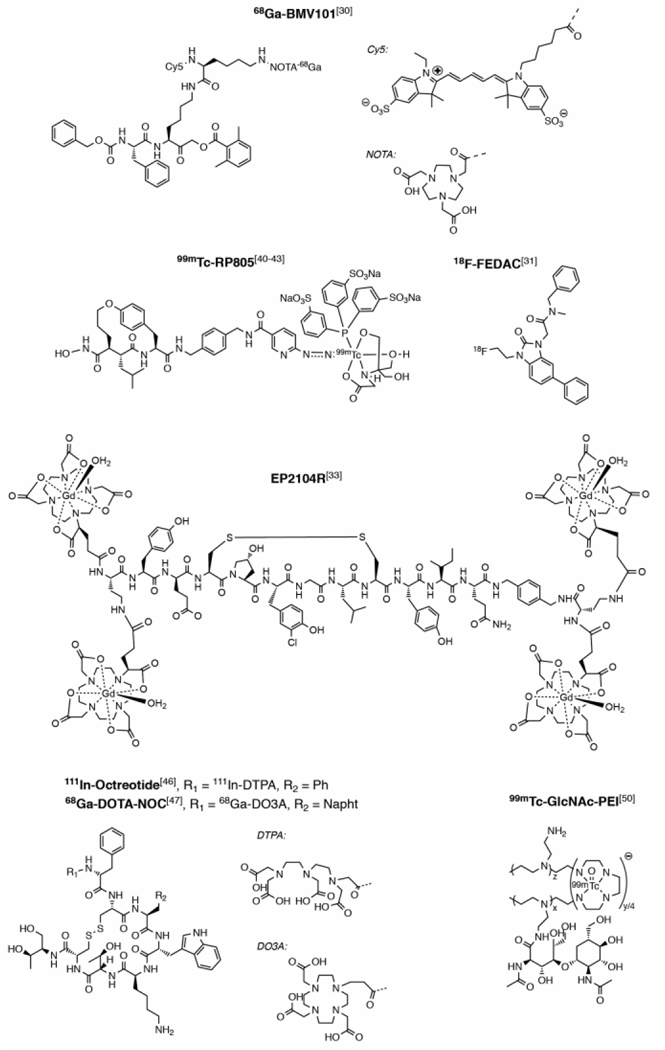

4.2.2. PET/SPECT imaging

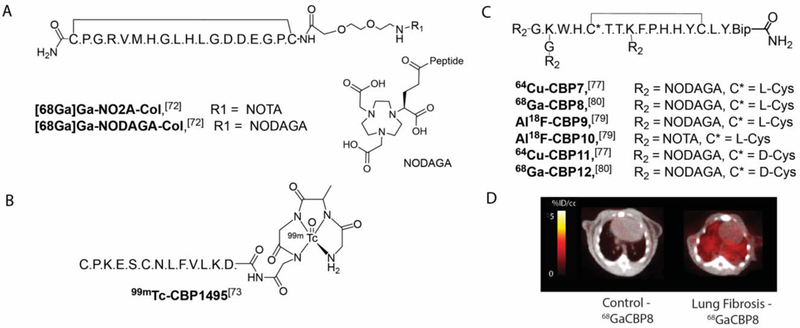

One of the first attempts to develop a collagen-targeted radiotracer for fibrosis imaging was done using a peptide targeted to the platelet receptor binding site on collagens I and III.[71] The peptide was labeled with Tc-99m and the efficacy of probe 99mTc-collagelin was tested in rat models of myocardial infarction and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Uptake of 99mTc-collagelin in fibrotic regions was modestly increased compared to a scrambled peptide control. Two PET versions of this probe ([68Ga]Ga-NO2A-Col and [68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-Col, Figure 6A) were reported but no in vivo data were presented.[72]

Figure 6. Collagen-targeted PET and SPECT imaging probes for fibrosis imaging.

A. Structures of the collagelin PET probes targeted to the platelet receptor-binding site on collagens I and III.[73] B. Structure of the collagen-binding SPECT probe 99mTc-CBP1495 derived from a peptide domain from pro-MMP-2.[74] C. Structures of the collagen-binding PET probes 64Cu-CBP7,[78] Al18F-CBP9,[80] Al18F-CBP10[80] and 68Ga-CBP8, [81].64Cu-CBP11[78] and 68Ga-CBP12[81] are the non-binding isomers of 64Cu-CBP7 and 68Ga-CBP8 respectively where one L-cysteine was replaced by D-cysteine. (Bip = biphenylalanine). D. Representative fused PET-CT images a control and fibrotic mouse demonstrating that 68Ga-CBP8/PET can detect bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. From Désogère Sci. Transl. Med. 9:eaaf4696 (2017).[81]

Another collagen-binding peptide labeled with Tc-99m was reported recently.[73] Peptide CBP1495 is a peptide domain from pro-MMP-2,[74] precursor of the enzyme MMP-2 that interacts with type I collagen.[75] The efficacy of probe 99mTc-CBP1495 (Figure 6B) was evaluated in rat models of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. The authors demonstrated a linear correlation between hydroxyproline content and ex vivo 99mTc-CBP1495 uptake. However, probe 99mTc-CBP1495 has a short circulation time, which limits its accumulation in target tissues. Further optimization is likely required for clinical translation.

We designed a series of collagen-targeted PET probes building on the previous work with the collagen-targeted MR probe EP-3533.[64] Based on previous structure-activity data,[76] we selected the peptides used in CBP1, CBP3, CBP5, CBP6 and CBP7.[77] Each peptide contains 17 amino acids, of which 11 are conserved to maintain collagen affinity. The disulfide bond was also shown to be essential.[64] We introduced a NODAGA chelator linked via an amide bond on the N terminus for Cu-64 chelation. All five probes displayed an affinity for collagen in the low micromolar range and similar pharmacokinetic profile in terms of radioactivity blood clearance. Their metabolic stability varied substantively, with 64Cu-CBP7 (Figure 6b) the most stable. The specificity of the 64Cu-CBP7 was determined by comparison with a non-binding isomer (64Cu-CBP11, Figure 6C), that contained a D-Cys cysteine moiety as opposed to L-Cys in 64Cu-CBP7. The collagen affinity of 64Cu-CBP11 dropped dramatically (100-fold loss), however both probes had the same distribution in healthy mice. In bleomycin-treated mice, 64Cu-CBP7 accumulated predominately in fibrotic lungs. The clinical translation of 64Cu-CBP7 is limited by its high kidney retention in mice. The 12.7 h half-life of copper-64 would result in a substantial radiation exposure to the kidney if a similar biodistribution was observed in humans.

To overcome this limitation, we prepared analogues labeled with radioisotopes with shorter half-lives Ga-68 (68 min) and F-18 (109.7 min). The analogues were all based on the same peptide sequence. The peptide was conjugated to a cyclic chelator and radiolabeled with Ga-68 or F-18 via complexation of aluminium fluoride.[78] The probes were evaluated in a bleomycin-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis and compared to sham-treated animals.[79] The two Al18F-labeled probes Al18F-CBP9 (NODAGA derivative, Figure 6C) and Al18F-CBP10 (NOTA derivative, Figure 6C) demonstrated high uptake in lungs of control animals and high non-target uptake in particular in liver and spleen (>13 and >9 %ID/g respectively), suggesting large aggregate formation in vivo. Off-target signal in the bone was also evident, especially for Al18F-CBP9 (>9 %ID/g). This effect was probably due to the partial dissociation of 18F-fluoride from the chelate.

The NODAGA derivative was also labeled with Ga-68 and the resulting probe 68Ga-CBP8 (Figure 6C) demonstrated fast blood clearance and high stability with respect to metabolism. 68Ga-CBP8 showed high efficacy for pulmonary fibrosis and high target:background ratios in the standard bleomycin mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 6D) and in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis associated with vascular leak.[80] In both models, lung PET signal and lung 68Ga-CBP8 uptake (quantified ex vivo) correlated strongly (r2=0.80) with the collagen concentration in fibrotic mice.

The specificity of 68Ga-CBP8 was determined by comparison with a non-binding isomer (68Ga-CBP12, Figure 6C), that contained a D-Cys cysteine moiety. We also showed that the probe 68Ga-CBP8 could effectively monitor treatment response with an anti-αvβ6 antibody therapy. To assess probe performance in human tissues, we incubated human IPF lung tissue samples with 68Ga-CBP8 and were able to correlate probe uptake with histological findings of IPF in these samples. Altogether, these data showed proof-of-principle evidence of the potential of 68Ga-CBP8 PET as an imaging agent for pulmonary fibrosis in humans.

4.3. Molecular imaging of fibrogenesis

Extracellular allysine represents a target with high specificity for fibrogenesis due to the abundance of allysine during active fibrogenesis. Aldehydes are generally not observed at high concentrations in vivo because they readily undergo reactions with nucleophiles. The LOX enzyme family generates reactive allysine so that it can undergo cross-linking condensation reactions to stabilize the extracellular matrix. While the LOX mediated oxidation of lysine residues is catalytic, subsequent condensation reactions between proteins is slow, and thus there is a buildup of extracellular allysine during fibrogenesis. We developed an assay to quantify allysine in tissue and showed in lung injury models that the allysine exceeds 150 nmol per gram tissue (~150 μM).[81] Since extracellular space is about 20% of tissue,[82] this puts the local extracellular allysine concentration at about 1 mM. These are very high concentrations and readily detectable by a suitably targeted MR probe.

We designed probes that could specifically and reversibly bind allysine. While amines react with aldehydes to form imines (Schiff bases), these are not stable in an aqueous environment. However other nucleophiles like hydrazides, hydrazines, and oxy-amino groups will form more stable, but still reversible condensation products.

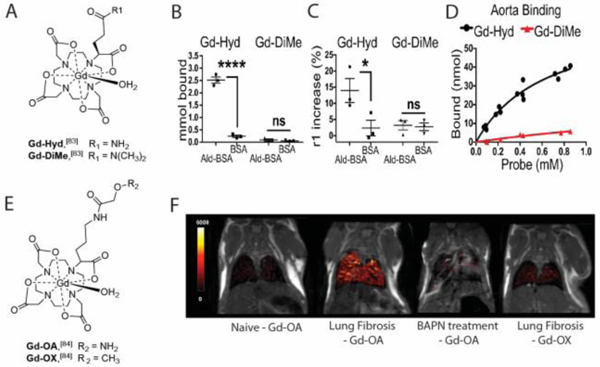

Initially we designed the probe Gd-Hyd based on a Gd-DOTA chelate conjugated to a hydrazide moiety (Figure 8A).[83] Hydrazide reacts with allysine though a reversible condensation reaction with to form a hydrazone. We showed that Gd-Hyd does not exhibit nonspecific protein binding after incubation in plasma but binds reversibly to oxidized BSA measured by ultrafiltration (Figure 8B), or relaxivity increase (Figure 8C), whereas Gd-DiMe showed no affinity for BSA not oxidised BSA. Gd-Hyd also binds to allysine-rich porcine aorta tissue with Kd of 650 μM (Figure 8D). Gd-Hyd has a blood half-life of 4.7 min in mice, similar to Gd-DOTA and other chelates with no protein binding. In the bleomycin lung injury mouse model, Gd-Hyd resulted in a 3.7-fold increase in the change in lung-to-muscle contrast-to-noise ratio (ΔCNR) in bleomycin-treated versus sham-treated mice, while the control probe Gd-DiMe showed no such enhancement. We also showed the ability of Gd-Hyd to monitor treatment response in bleomycin injured mice. Treatment with the pan-LOX inhibitor beta-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) reduced LOX activity to levels similar to those measured in the sham-treated mice. Similar effects of BAPN treatment were also seen by Gd-Hyd enhanced MRI signal, where the ΔCNR of treated animals was decreased to values observed in sham mice. We also showed that Gd-Hyd enhanced MRI could detect CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and monitor disease progression as well as regression.

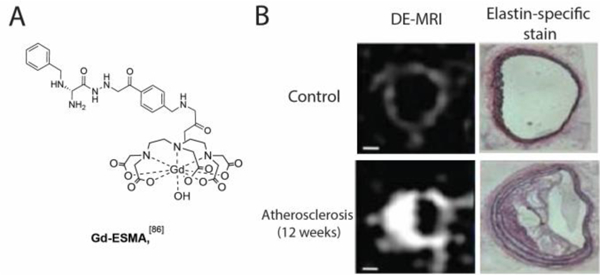

Figure 8.

A. Structure of the elastin-specific MR contrast agent Gd-ESMA. B. Representative delayed enhancement MR images (DE-MRI) of cross-sectional views of brachiocephalic arteries demonstrating that Gd-ESMA can non-invasively detect a plaque burden in a mouse model of atherosclerosis. The extent of plaque burden of the brachiocephalic arteries was confirmed by elastin-specific staining with the Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain. From Makowski Nat. Med 17:383–388 (2011)).[86]

We then modified the probe to change the hydrazide moiety for an oxyamine, but kept the stable Gd-DOTA core to give GdOA (Figure 8E).[84] GdOA exhibited higher relaxivity in the presence of oxidized BSA (8.1 vs 4.6 mM−1s−1) and had higher affinity to porcine aorta than Gd-Hyd (Kd = 340 μM vs 650 μM). Gd-OA displayed both low non-specific binding and rapid background clearance. Gd-OA also demonstrated enhanced MRI signal in fibrotic tissue in the bleomycin mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis by targeting allysine, while the control probe Gd-OX showed no such enhancement (Figure 8F). Effects of treatment with the pan-LOX inhibitor BAPN were also seen by Gd-OA enhanced MRI signal, where the ΔCNR of treated animals was reduced to levels observed in sham animals. Hence Gd-OA imaging enables the degree of ongoing fibrogenesis to be determined non-invasively.

4.4. Imaging of Collagen Remodeling

Collagen undergoes proteolytic remodeling during fibrosis, which leads to the unfolding of the triple helical structure. Hwang et al developed collagen hybridizing peptides (CHP) that recognize the triple helix structure of immature and remodeling collagen fibers.[85] CHP specifically re-forms a triple helical structure by binding to the denatured collagen strands. CHP was labeled with 5-carboxyfluorescein (probe F-CHP) to image collagen remodeling on sections of heart tissues after MI and lung tissues from mice with pulmonary fibrosis. Authors demonstrated the visualization and quantification of tissue remodeling by fluorescence microscopy.

4.5. Elastin Imaging

Gd-ESMA is an elastin-specific MR contrast agent (Figure 8A).[86] Gd-ESMA demonstrated moderate affinity to elastin (IC50 = 0.33 mM) but weak binding to plasma proteins.[86] In normal mice, high-resolution delayed enhancement MRI (DE-MRI) after Gd-ESMA injection showed the presence of elastin in the brachiocephalic vessel wall (Figure 8B, top images), which was further confirmed using the elastin-specific staining (Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain). In a mouse model of atherosclerosis, Gd- ESMA also effectively quantify plaque progressions (Figure 8B, bottom images).[84] Elastin-targeted MR has also been used in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis for assessing plaque burden.[17] Gd-ESMA also showed efficacy in detecting arterial thrombi and defining thrombus age in swine model,[87] assessing aortic aneurysm wall integrity,[88] and assessing myocardial remodeling post myocardial infarction.[89]

Elastin-targeted MR has been performed in several animal models of liver fibrosis with Gd-ESMA demonstrating strong signal in elastin-rich regions.[90] Elastin accumulation occurs later in fibrosis, which will limit its use for assessing early stages of disease.

5. Discussion

Many of the molecular targets discussed above are not unique to fibrosis. Early onset of fibrosis in many organs is marked by an inflammatory component and the cathepsin and macrophage examples, for instance, are also probes that can be used to image inflammation in non-fibrotic diseases. There are also clear parallels in cancer development and progression and aspects of fibrosis biology.[91] Integrins such as αvβ6 and αvβ3 are upregulated in certain cancers and fibrotic diseases. The lack of disease specificity is not necessarily a drawback of these probes. One has to consider the context of the molecular imaging study. Often, the presence of disease is known and the medical question is to quantify the disease (how advanced is the disease) and to assess whether the disease is responding to treatment or worsening. In such cases a less specific probe may be effective provided that it can address the medical question. Molecular imaging is also often performed in conjunction with other types of high resolution imaging that can provide detail on anatomy and function. For example, CT or MR imaging can be combined with molecular imaging of fibrin to demonstrate that the molecular signal is coming from the extravascular space (as the result of a leaky vessel and coagulation associated with fibrosis) and not from a large blood clot within the vessel. On the other hand, if the question is disease diagnosis, then a probe targeting a more specific fibrotic component like collagen would be expected to be more specific than a probe targeting a marker of inflammation.

6. Conclusion

Fibrosis is a common result of chronic tissue injury. Despite progress in our understanding of fibrosis pathogenesis and its underlying molecular mechanisms, advances in the clinical management of fibrotic diseases have been relatively modest. Fibrotic diseases are notoriously difficult to model and there are differences between the pathology in proof-of-concept animal studies and human disease. There are also obstacles to the clinical development of antifibrotic therapies, such as patient heterogeneity and imprecise clinical endpoints, that necessitate long and costly clinical trials. Imaging-based biomarkers are ideal tools for non-invasive and repetitive measurements of changes in vivo, hence facilitating the pre-clinical investigation of new therapeutic targets, the validation of new animal models, and the translational research into humans to improve management and treatment of patients with fibrosis. The molecular probes described here represent first steps for addressing these problems. While much progress has been made, there is still a clear need for better clinical imaging tools. This first generation of molecular probes can be improved with respect to selectivity, dynamic range, and improved target-to-background ratio. The broad potential utility of fibrosis imaging probes makes this an area ripe for further innovation to positively impact patient care.

Figure 7.

A. Structure of Gd-Hyd and Gd-DiMe. B. Protein binding assays demonstrating that Gd-Hyd binds to allysine in oxidized bovine serum albumin (Ald-BSA) but not to unmodified BSA. Gd-DiME showed no binding to oxidized BSA nor unmodified BSA. C. Relaxivity measurements for Gd-Hyd and Gd-DiMe showing a significant increase in relaxivity for Gd-Hyd with BSA-Ald indicating specific probe binding to aldehyde-rich BSA. D. Binding curves of Gd-Hyd and Gd-DiMe with aorta tissue demonstrating that only Gd-Hyd binds to allysine-rich porcine aorta with Kd of 640 μM. E. Structure of GdOA and GdOX. F. Representative coronal MR images with overlaid lung enhancement (shown in false color) showing GdOA uptake in naive mouse, in bleomycin mouse (pulmonary fibrosis), in bleomycin-challenged mouse treated daily for 14 days with the pan-LOX inhibitor BAPN, and showing GdOX uptake in bleomycin mouse. Gd-OA demonstrated enhanced MRI signal in fibrotic tissue in the bleomycin mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis by targeting allysine, while the control probe Gd-OX showed no such enhancement. Effects of treatment with BAPN were also seen by Gd-OA enhanced MRI signal. (*P<0.005, ****P<0.0001, ns, not significant). Panels B, C and D from Chen JCI Insight. 2:1–9 (2017)[84] and panel F from Waghorn Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56:9825–9828 (2017).[85]

Acknowledegements

Dr P. Waghorn is warmly acknowledged for the design of Figure 2. Competing interest: P.C. has equity in Collagen Medical, the company, which holds the patent rights to the fibrin (FBP8) and collagen peptides (EP-3533, CM-101). P.C. and P.D. are inventors on patent/patent application that covers the collagen PET probes (CBPn, n=7–12).

Biography

Pauline Désogère received her PhD in Chemistry from the University of Burgundy in 92009 under the guidance of Prof. Franck Denat and Dr Christine Goze. She joined the group of Prof. Peter Caravan for her post-doctoral work in 2013 at the A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School (HMS). Here, she developed PET probes that target collagen for detection and staging of pulmonary fibrosis in animal models. Pauline was promoted to the faculty at HMS in 2016 as an Instructor in Radiology and as the Program Manager and Industry Liaison for the Institute for Innovation in Imaging at MGH. Her primary goals are directed towards facilitating the clinical translation of novel diagnostic tools for early disease detection and monitoring emergent treatments.

Sydney Montesi received her medical degree from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. She then completed her residency in internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and her fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine in the Harvard Combined Program. She is an attending physician at Massachusetts General Hospital specializing in the care of patients with interstitial lung diseases. Her research focuses on the use of novel molecular imaging and biomarkers of lung injury to assess disease activity and predict disease progression in pulmonary fibrosis.

Peter Caravan received his BSc from Acadia University and PhD in Chemistry from the University of British Columbia with Professor Chris Orvig. After postdoctoral work with Professor André Merbach at the Université de Lausanne, Dr Caravan joined EPIX Medical in 1998 to develop targeted MR probes including the FDA-approved probe Ablavar. In 2007 he moved to the A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School to establish a translational molecular imaging laboratory. In 2014 he was named Co-Director of the Institute for Innovation in Imaging at MGH. His current research focuses on the development of MR and PET probes and their applications in cardiovascular disease, fibrotic diseases, and cancer.`

Footnotes

This review is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Andrew Tager, an inspirational scientist, mentor, and friend whose passion for research was infectious.

Contributor Information

Pauline Désogère, The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 02129 (USA); Department of Radiology, The Institute for Innovation in Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, 02128 (USA).

Sydney B. Montesi, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, 02114 (USA)

Peter Caravan, The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 02129 (USA); Department of Radiology, The Institute for Innovation in Imaging, Boston, Massachusetts, 02128 (USA).

References

- [1].Chen F, Liu Z, Wu W, Rozo C, Bowdridge S, Millman A, Van Rooijen N, Urban JF Jr., Wynn TA, Gause WC, Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ahluwalia N, Shea BS, Tager AM, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 867–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schuppan D, Afdhal NH, Lancet 2008, 371, 838–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brilla CG, Funck RC, Rupp H, Circulation 2000, 102, 1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sugimoto H, Grahovac G, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R, Diabetes 2007, 56, 1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lan TH, Huang XQ, Tan HM, Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2013, 22, 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Mehal WZ, Iredale J, Friedman SL, Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 552–553; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Scoazec J, Verrecchia F, Jacob M, Bruneval P, in Ann. Pathol., Vol. 26, 2006, pp. 1S43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ueha S, Shand FH, Matsushima K, Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rotman Y, Sanyal AJ, Gut 2016, 180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 549–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jugdutt BI, Joljart MJ, Khan MI, Circulation 1996, 94, 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Burstein B, Nattel S, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cox TR, Erler JT, Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cox TR, Bird D, Baker AM, Barker HE, Ho MW, Lang G, Erler JT, Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1721–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lynch DA, Godwin JD, Safrin S, Starko KM, Hormel P, Brown KK, Raghu G, King TE Jr., Bradford WZ, Schwartz DA, Richard Webb W, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Cheong BY, Muthupillai R, Wilson JM, Sung A, Huber S, Amin S, Elayda MA, Lee VV, Flamm SD, Circulation 2009, 120, 2069–2076; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wong TC, Piehler K, Puntil KS, Moguillansky D, Meier CG, Lacomis JM, Kellman P, Cook SC, Schwartzman DS, Simon MA, J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013, 15, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Phinikaridou A, Andia ME, Indermuehle A, Onthank DC, Cesati RR, Smith A, Robinson SP, Saha P, Botnar RM, Radiology 2014, 271, 390–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Talwalkar JA, Kurtz DM, Schoenleber SJ, West CP, Montori VM, Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 2007, 5, 1214–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Ehman RL, J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 36, 757–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rockey DC, Bell PD, Hill JA, Engl N. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1138–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wynn TA, Pathol J. 2008, 214, 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR, Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1028–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Diegelmann RF, Evans MC, Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Kagan HM, Li W, J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 88, 660–672; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamauchi M, Shiiba M, in Post-translational Modifications of Proteins, Springer, 2008, pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Parsons CJ, Takashima M, Rippe RA, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, S79–S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Weissleder R, Mahmood U, Radiology 2001, 219, 316–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, Phythian-Adams AT, van Rooijen N, Haslett C, Howie SE, Simpson AJ, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 184, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mohamed MM, Sloane BF, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Verdoes M, Oresic Bender K, Segal E, van der Linden WA, Syed S, Withana NP, Sanman LE, Bogyo M, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14726–14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Withana NP, Ma X, McGuire HM, Verdoes M, van der Linden WA, Ofori LO, Zhang R, Li H, Sanman LE, Wei K, Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hatori A, Yui J, Xie L, Kumata K, Yamasaki T, Fujinaga M, Wakizaka H, Ogawa M, Nengaki N, Kawamura K, Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brown LF, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF, Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989, 140, 1104–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Overoye-Chan K, Koerner S, Looby RJ, Kolodziej AF, Zech SG, Deng Q, Chasse JM, McMurry TJ, Caravan P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6025–6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].a) Botnar RM, Buecker A, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC, Katoh M, Katsimaglis G, Weisskoff RM, Lauffer RB, Graham PB, Gunther RW, Circulation 2004, 110, 1463–1466; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Spuentrup E, Buecker A, Katoh M, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC, Botnar RM, Weisskoff RM, Graham PB, Manning WJ, Günther RW, Circulation 2005, 111, 1377–1382; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Spuentrup E, Katoh M, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC Jr, Botnar RM, Mahnken AH, Günther RW, Buecker A, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 494–500.15937292 [Google Scholar]

- [35].a) Johnson KM, Fain SB, Schiebler ML, Nagle S, Magn. Reson. Med. 2013, 70, 1241–1250; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Caravan P, Yang Y, Zachariah R, Schmitt A, Mino-Kenudson M, Chen HH, Sosnovik DE, Dai G, Fuchs BC, Lanuti M, Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 1120–1126; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Togao O, Tsuji R, Ohno Y, Dimitrov I, Takahashi M, Magn. Reson. Med. 2010, 64, 1491–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shea BS, Probst CK, Brazee PL, Rotile NJ, Blasi F, Weinreb PH, Black KE, Sosnovik DE, Van Cott EM, Violette SM, JCI Insight 2017, 2, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Neubauer K, Knittel T, Armbrust T, Ramadori G, Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1124–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chow AM, Tan M, Gao DS, Fan SJ, Cheung JS, Man K, Lu ZR, Wu X, Invest. Radiol. 2013, 48, 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tan M, Wu X, Jeong EK, Chen Q, Lu Z-R, Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 754–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Su H, Spinale FG, Dobrucki LW, Song J, Hua J, Sweterlitsch S, Dione DP, Cavaliere P, Chow C, Bourke BN, Circulation 2005, 112, 3157–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liu YH, Sahul Z, Weyman CA, Dione DP, Dobrucki WL, Mekkaoui C, Brennan MP, Ryder WJ, Sinusas AJ, J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sahul ZH, Mukherjee R, Song J, McAteer J, Stroud RE, Dione DP, Staib L, Papademetris X, Dobrucki LW, Duncan JS, Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].a) Fujimoto S, Hartung D, Ohshima S, Edwards DS, Zhou J, Yalamanchili P, Azure M, Fujimoto A, Isobe S, Matsumoto Y, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1847–1857; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Haider N, Hartung D, Fujimoto S, Petrov A, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Ohshima S, Liu H, Zhou J, Fujimoto A, J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2009, 16, 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chen J, Tung CH, Allport JR, Chen S, Weissleder R, Huang PL, Circulation 2005, 111, 1800–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Borie R, Fabre A, Prost F, Marchal-Somme J, Lebtahi R, Marchand-Adam S, Aubier M, Soler P, Crestani B, Thorax 2008, 63, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lebtahi R, Moreau S, Marchand-Adam S, Debray MP, Brauner M, Soler P, Marchal J, Raguin O, Gruaz-Guyon A, Reubi JC, Le Guludec D, Crestani B, J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 47, 1281–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ambrosini V, Zompatori M, De Luca F, Antonia D, Allegri V, Nanni C, Malvi D, Tonveronachi E, Fasano L, Fabbri M, Fanti S, J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 1950–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Niki T, Pekny M, Hellemans K, De Bleser P, Van Den Berg K, Vaeyens F, Quartier E, Schuit F, Geerts A, Hepatology 1999, 29, 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kim SJ, Ise H, Kim E, Goto M, Akaike T, Chung BH, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 6504–6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Azad AK, Rajaram MV, Metz WL, Cope FO, Blue MS, Vera DR, Schlesinger LS, Immunol J. 2015, 195, 2019–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Vaeyens F, Nat. Med, 2013, 19, 1617–1624.24216753 [Google Scholar]

- [52].Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJD, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet JF, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay MA, Rifkin DB, Sheppard D, Cell 1999, 96, 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang B, Dolinski BM, Kikuchi N, Leone DR, Peters MG, Weinreb PH, Violette SM, Bissell DM, Hepatology 2007, 46, 1404–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Patsenker E, Stickel F, Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G425–G434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hahm K, Lukashev ME, Luo Y, Yang WJ, Dolinski BM, Weinreb PH, Simon KJ, Wang LC, Leone DR, Lobb RR, Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 110–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Saha A, Ellison D, Thomas GJ, Vallath S, Mather SJ, Hart IR, Marshall JF, The Journal of pathology 2010, 222, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].John AE, Luckett JC, Tatler AL, Awais RO, Desai A, Habgood A, Ludbrook S, Blanchard AD, Perkins AC, Jenkins RG, J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 2146–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].a) Yu X, Wu Y, Liu H, Gao L, Sun X, Zhang C, Shi J, Zhao H, Jia B, Liu Z, Radiology 2015, 279, 502–512; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li F, Song Z, Li Q, Wu J, Wang, Xie C, Tu C, Wang J, Huang X, Lu W, Hepatology 2011, 54, 1020–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].a) Wang QB, Han Y, Jiang TT, Chai WM, Chen KM, Liu BY, Wang LF, Zhang C, Wang DB, Eur. Radiol. 2011, 21, 1016–1025; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b)Zhang C, Liu H, Cui Y, Li X, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wang D, Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Siegel RC, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1974, 71, 4826–4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Fratzl P, in Collagen, Springer, 2008, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tanzer ML, Science 1973, 180, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].a) Bornstein P, Kang AH, Piez KA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1966, 55, 417–424; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pinnell SR, Martin GR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1968, 61, 708–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Caravan P, Das B, Dumas S, Epstein FH, Helm PA, Jacques V, Koerner S, Kolodziej A, Shen L, Sun WC, Zhang Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007, 46, 8171–8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Helm PA, Caravan P, French BA, Jacques V, Shen L, Xu Y, Beyers RJ, Roy RJ, Kramer CM, Epstein FH, Radiology 2008, 247, 788–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Spuentrup E, Ruhl KM, Botnar RM, Wiethoff AJ, Buhl A, Jacques V, Greenfield MT, Krombach GA, Gunther RW, Vangel MG, Caravan P, Circulation 2009, 119, 1768–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Polasek M, Fuchs BC, Uppal R, Schühle DT, Alford JK, Loving GS, Yamada S, Wei L, Lauwers GY, Guimaraes AR, Tanabe KK, Caravan P, Hepatol J. 2012, 57, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].a) Fuchs BC, Wang H, Yang Y, Wei L, Polasek M, Schühle DT, Lauwers GY, Parkar A, Sinskey AJ, Tanabe KK, J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 992–998; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Farrar CT, DePeralta DK, Day H, Rietz TA, Wei L, Lauwers GY, Keil B, Subramaniam A, Sinskey AJ, Tanabe KK, Fuchs BC, Caravan P, J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 689–696; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhu B, Wei L, Rotile N, Day H, Rietz T, Farrar CT, Lauwers GY, Tanabe KK, Rosen B, Fuchs BC, Hepatology 2017, 65, 1015–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Farrar CT, Gale EM, Kennan R, Ramsay I, Masia R, Arora G, Looby K, Wei L, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Bunzel MM, Radiology 2017, 170595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].a) Thakral C, Abraham JL, J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36, 1244–1254; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sanyal S, Marckmann P, Scherer S, Abraham JL, Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 3616–3626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Muzard J, Sarda-Mantel L, Loyau S, Meulemans A, Louedec L, Bantsimba-Malanda C, Hervatin F, Marchal-Somme J, Michel JB, Le Guludec D, Billiald P, Jandrot-Perrus M, PloS one 2009, 4, e5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Velikyan I, Rosenström U, Estrada S, Ljungvall I, Häggström J, Eriksson O, Antoni G, Nucl. Med. Biol. 2014, 41, 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zheng L, Ding X, Liu K, Feng S, Tang B, Li Q, Huang D, Yang S, Amino acids 2017, 49, 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lee ER, Lamplugh L, Kluczyk B, Leblond CP, Mort JS, Dev. Dyn. 2009, 238, 1547–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].An B, Lin YS, Brodsky B, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].a) Caravan P, Das B, Deng Q, Dumas S, Jacques V, Koerner SK, Kolodziej, Looby RJ, Sun WC, Zhang Z, Chem. Commun. 2009, 430–432;; b) Désogère P, Caravan P, US Patent App. 15/320,112, 2017.

- [77].Désogère P, Tapias LF, Rietz TA, Rotile N, Blasi F, Day H, Elliott J, Fuchs BC, Lanuti M, Caravan P, J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1991–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].a) McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, D’Souza CA, Rossi EA, Laverman P, Chang CH, Boerman OC, Goldenberg DM, J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 991–998; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McBride WJ, D’Souza CA, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Rossi EA, Chang CH, Goldenberg DM, Bioconjug. Chem. 2010, 21, 1331–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Désogère P, Tapias L, Rietz T, Rotile N, Blasi F, Day H, Fuchs B, Lanuti M, Caravan P, J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 6–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Désogère P, Tapias LF, Hariri LP, Rotile NJ, Rietz TA, Probst CK, Blasi F, Day H, Mino-Kenudson M, Weinreb P, Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaaf4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Waghorn PA, Oliveira BL, Jones CM, Tager AM, Caravan P, J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1064, 7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bandula S, Banypersad SM, Sado D, Flett AS, Punwani S, Taylor SA, Hawkins PN, Moon JC, Radiology 2013, 268, 858–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Chen HH, Waghorn PA, Wei L, Tapias LF, Schühle DT, Rotile NJ, Jones CM, Looby RJ, Zhao G, Elliott JM, JCI Insight 2017, 2, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Waghorn PA, Jones CM, Rotile NJ, Koerner SK, Ferreira DS, Chen HH, Probst CK, Tager AM, Caravan P, Angew. Chem. 2017, 56, 9825–9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Hwang J, Huang Y, Burwell TJ, Peterson NC, Connor J, Weiss SJ, Yu M, Li Y, ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9825–9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Makowski MR, Wiethoff AJ, Blume U, Cuello F, Warley A, Jansen CH, Nagel E, Razavi R, Onthank DC, Cesati RR, Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Corti R, Fuster V, Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1709–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].a) Botnar RM, Wiethoff AJ, Ebersberger U, Lacerda S, Blume U, Warley A, Jansen CH, Onthank DC, Cesati RR, Razavi R, Circ.: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 679–689; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Okamura H, Pisani LJ, Dalal AR, Emrich F, Dake BA, Arakawa M, Onthank DC, Cesati RR, Robinson SP, Milanesi M, Circ.: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 690–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Protti A, Lavin B, Dong X, Lorrio S, Robinson S, Onthank D, Shah AM, Botnar RM, Am J. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].a) Pellicoro A, Aucott RL, Ramachandran P, Robson AJ, Fallowfield JA, Snowdon VK, Hartland SN, Vernon M, Duffield JS, Benyon RC, Hepatology 2012, 55, 1965–1975; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ehling J, Bartneck M, Fech V, Butzbach B, Cesati R, Botnar R, Lammers T, Tacke F, Hepatology 2013, 58, 1517–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Karagiannis GS, Poutahidis T, Erdman SE, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Diamandis EP, Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 1403–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]