Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the combined effectiveness of a parenting intervention, Families Preparing the New Generation (FPNG), and a youth curriculum, keepin ‘ it REAL (kiR), on substance use prevention for middle school students in a large urban metro area of the Southwest USA. The study aimed to generate usable knowledge on what works in adolescent substance use prevention and how it works best – a combined parent and youth programing or parent-only programming. A total of 532 adolescents in the 7th grade from 19 participating middle schools were randomly assigned into three intervention conditions: Parent-Youth (PY), Parent-Only (PO), and Comparison (C). This article focuses on the comparison between PY and PO in order to determine which intervention strategy works best to reduce adolescent substance use including, alcohol, inhalant, cigarette, and marijuana uses. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) model examined the longitudinal data. The results for alcohol use show that PO yielded better results than PY and that PY outperformed C after 20 months. Further, PO showed a decreasing trajectory in any substance use over time since the implementation of the intervention. The effect sizes based on Cohen’s h indicate small effects in any substance use and alcohol use for PO condition and smaller effects for the PY condition. These findings have implications for the design of future culturally specific parenting and youth prevention interventions with Latino families.

Keywords: substance use, cultural adaptation, adolescents, parents, Latino

Background

The negative effects of adolescent substance use on psychological and physical development are a major public health concern in the U.S. (Casey & Jones 2010; Hallfors et al. 2004). A large proportion of students in the U.S. middle and high schools are still exposed to a variety of harmful substances. For example, 23.1%, 13.5%, 9.4% and 8.9% of the 8th grade students in 2017 have ever used alcohol, inhalants, cigarette, and marijuana, respectively (Johnson, Miech, O’Malley, Bachman, and Schulenberg 2018). Early age drinking is not only associated with school problems and changes in brain development, but also with a variety of negative physical and psychological outcomes in later life (CDC 2018a and 2018b; Marshall 2015).

Moreover, there is a racial and ethnic variation in substance use. The prevalence of lifetime alcohol, cigarette, inhalant, marijuana and cocaine use are significantly higher among Latino youth than youth from other race and ethnic groups (Kann et al. 2018). Latino youth tend to report a higher level of illicit drug use, particularly marijuana, compared to African Americans and Whites (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulengberg 2017). Further, their substance use tend to persist even after the transition to adulthood, which in turn lead to various health and life problems in their later lives (Chen & Jacobson 2012; Odgers et al. 2008).

A persistent and high level of substance use among Latino youth demands the development of effective interventions, particularly designed for this disadvantaged group. A community-based synchronized parent/youth delivery approach has the potential of lowering barriers to prevention interventions that Mexican heritage youth and their parents often experienced (Marsiglia, Williams, Ayers, & Booth 2014). Strengthening the impact of prevention efforts can lower the cost of treating youths as they get older, and if not exposed to such prevention efforts some youth may develop serious health conditions associated with early onset of alcohol and drug use. Well-supported scientific evidence demonstrates that a variety of programs and policies can prevent substance use initiation, harmful use, and substance use-related problems in a cost-effective manner (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ) 2016). Our study aims to assess the effectiveness of two community-based culturally adapted interventions (Families Preparing the New Generation and keepin ‘ it REAL) involving Latino youth and their parents.

Substance abuse prevention and family involvement

Active and positive family involvement play an important role in lowering the chance of initiation in substance use among adolescents (Van Ryzin, Roseth, Fosco, Lee & Chen 2016). Involving family members in an intervention program can strengthen adolescent anti-drug attitudes and norms, and can reduce actual substance use. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed the overall significant effect of family interventions in reducing alcohol use among general adolescent populations up to 48 months following the intervention (Smit, Verdurmen, Monshouwer, & Smit 2008). In addition, family-focused interventions are more likely to be robust and effective for longer periods compared to individual-focused interventions (Copello, Templeton, & Velleman 2006; Slesnick & Prestopnick 2005).

The eco-developmental theory supports why involving family in substance intervention can be effective. The theory posits that parents, especially, play a primary role in the socialization of youth and can have a strong impact on either the development or prevention of youth problem behaviors. This ecological system model provides a multidimensional framework that helps explain the influence of family, school, peer, and acculturation mechanisms (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth, and Szapocznik, 2003; Martinez, Huang, Estrada, Sutton, & Prado 2017). The theory conceptualizes the multidimensional processes of adolescent risk behaviors according to the multiple contexts influencing development: the micro-systems in which the adolescent participates directly (e.g., parents, school, peers); the meso-systems that connect microsystems (e.g., parental monitoring, parent-peer or parent-school interactions); the exo-system (e.g. parental social support, family socioeconomic situation); and macro-systems (e.g., cultural processes, acculturation stress and perceived discrimination). Positive social support within and between these systems can facilitate positive social outcomes, while conflict between them can lead to behavioral problems, such as drug use.

kiR and FPNG: Two efficacious prevention interventions

keepin’ it REAL (kiR) is a 10 lesson culturally-based, evidence-based substance use prevention program for youth teaching the Refuse-Explain-Avoid-Leave (REAL) drug resistance strategies. kiR was recognized as a National Model Program by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Schinke, Brounstein, & Gardner 2002). It was designed to: (a) increase drug resistance skills; (b) promote anti-substance use norms and attitudes; and (c) develop effective decision making and communication skills for resisting drugs and alcohol (Marsiglia & Hecht 2005). kiR also aims to build personal and cultural strengths and communication and life skills (see Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht 2003). The intervention also provides youth with opportunities to participate in culturally relevant activities that allow them to discuss how and why their cultural values are important to them (Marsiglia & Hecht 2005).

Families Preparing the New Generation (FPNG) empowers parents to assist their children in resisting alcohol and other drugs by using the same REAL strategies, strengthen family functioning, and increase communication skills (Parsai, Castro, Marsiglia, Harthun, & Valdez 2011). FPNG has 8 lessons designed to complement and enhance kiR (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005). Through interactive, hands-on activities, FPNG includes lessons on identifying social support, understanding adolescent development, enhancing a warm and positive parent-child relationship, managing adolescent behaviors, and preparing for sensitive adolescent conversations around risky behaviors (e.g., substance use and sexual behavior; see Williams, et al., 2012).

Both kiR and FPNG have shown to be efficacious and also effective in preventing substance use for both youth (Williams, Ayers, Baldwin, & Marsiglia 2016; Marsiglia, Ayers, & Kiehne in press; Kulis et al. 2005) and their parents (Williams, Marsiglia, Baldwin, & Ayers 2015).

Latino culture and parental involvement in the intervention

Involving both youth and their families in substance abuse prevention research and practice is not new (Austin, Macgowan, & Wagner 2005). However, it is still unclear what works, where, and for whom — how does an intervention that empowers parents to assist their children in resisting alcohol and other drugs compare to an intervention that involves parents, children, and schoolteachers?

Although it is often cited and shown that among majority cultures, having multiple ecological systems interacting with and involved in the child’s development and well-being (e.g., parents and teachers) (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth & Szapocznik 2003), this may not necessarily be the case for Latino families, particularly immigrant families. In general, Latino culture tends to highly respect teachers, and possible interference from parents could be seen as disrespectful or rude (i.e., respecto; Tinkler 2002). This may account for findings indicating that immigrant parents are less likely to be involved in the formal education of their children (Kuperminc, Darnell, Alvarez-Jimenez 2008). Immigrant parents are, however, more likely to trust schools and teachers compared to US-born parents, including Caucasian and African American parents (Pena 2000). When Latino parents begin to take on roles and responsibilities that the teacher may normally do, it is likely that Latino parents often feel they are interfering in the teacher’s space and are unsure how to act. This is mainly because of their definition of parental involvement in child’s education tends to be life participation than academic involvement (Zarate 2007). Monolingual Latino parents must also rely on teachers more because the coursework is in English. This provides monolingual or Spanish language dominant parents limited opportunities to engage with their child around schoolwork and to navigate complex and large English-speaking bureaucracies (De Gaetano, 2007; Zarate 2007). As a result, those parents may be less likely to engage in a school taught curriculum at home, including a classroom-delivered substance use prevention interventions.

On the other hand, when parents are the only ones receiving the intervention, they may be empowered and feel responsible for relaying messages to their children. For Latino parents, this may be reflected in the cultural value of familism. Familism — a set of normative values that stress the fundamental role of the family unit — provides the cultural framework for parents to guide their children’s behavior and promote pro-social behaviors that are in accordance with these values (Germán, Gonzales, & Dumka 2009; Roosa, Morgan-Lopez, Cree, & Specter 2002). In addition, delivering interventions to parents in their own language (e.g., Spanish) and culture, increases engagement, retention, and improvement in intervention outcomes (George et al. 2017).

Purpose

These considerations led to comparisons between three intervention conditions: 1) Parent-Youth condition (PY) vs. the comparison condition (C); 2) Parent-Only condition (PO) and C; 3) PY vs. PO. In the PY condition, the parents received the FPNG intervention and their child simultaneously received the kiR intervention. In the PO condition, only parents received the intervention, FPNG. In the C condition, only parents received a comparison curriculum designed by the community partner without an alcohol and other drugs prevention focus. The first two comparisons tested if receiving a substance use prevention intervention (PY, PO) compared to receiving a comparison curriculum (C) would reduce adolescent substance use over time. The third comparison (PY vs. PO) tested if there was a preferred delivery method for adolescent substance use prevention interventions for Latino families.

Methods

Cluster randomized controlled trial design

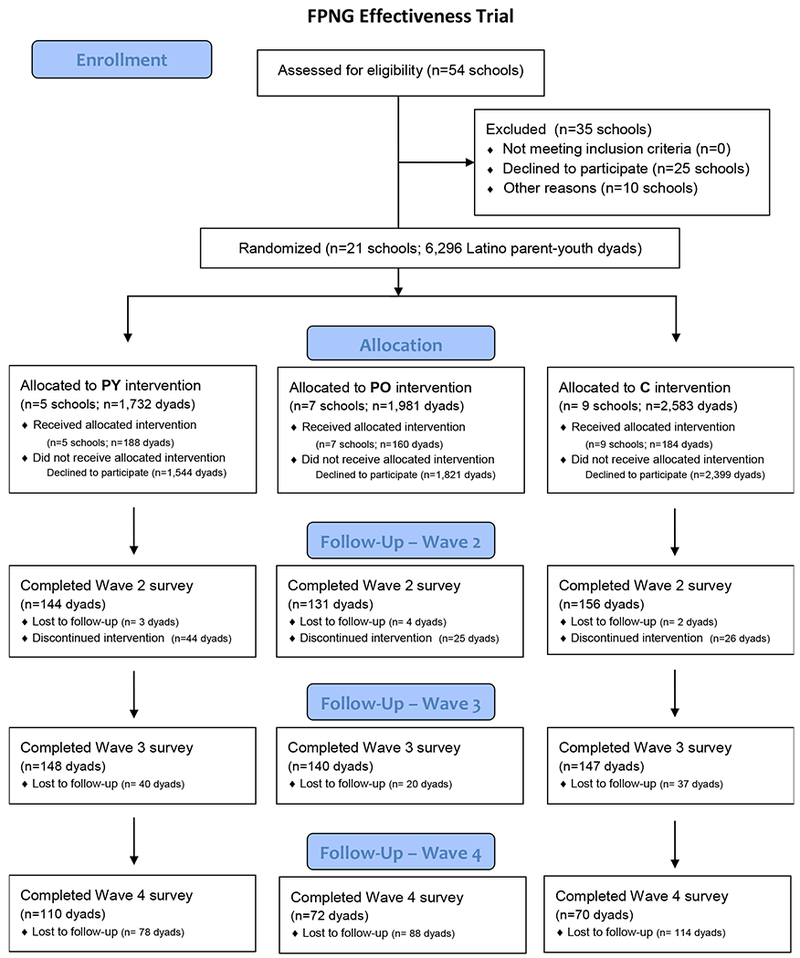

Initially, our community partner, which we call the Parent Academy (PA), approached the 54 eligible and randomized middle schools. The inclusion criteria were the number (over 100 students in the 7th grade) and proportion of Latino students (over 60%) in school, the location (within the county boundary of a major metropolitan area in the Southwest of USA), and Title 1 funding status (federal financial assistance program). Those 54 schools were first rank ordered by the estimated number of Latino 7th grade students and then cluster randomized and assigned to PY, PO or C intervention conditions. The final 21 schools agreed to participate in the study: 9 schools in C, 5 schools in PY, and 7 schools in PO. Within each school, all parents and their 7th grade youth were eligible to participate (see Figure 1 for the Consort diagram).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram for Participant Flow

The eligible sample was drawn from three cohorts of 7th grade youth and their parents: the 2013-2014, 2013-2014, and 2014-2015 school years. The procedures remained the same regardless of the cohort, and the study was complete at the end of the follow-up period for Cohort 3. The community partner, as trained study personnel, oversaw the enrollment and consent process at each school. With coordination from school staff, the community partner focused recruitment and enrollment efforts on Latino families in each of the school. Parents were invited by telephone and invitational flyer to attend an introductory parent information session that explained the parenting program in that school.

Informed parental consent was obtained during an informational workshop for parents describing the parenting intervention being offered at that school. All participants, youth and parents, could participate in the receipt of the intervention (when applicable), regardless of consent. Consent only applied to data collection. No important changes to these methods were made after the trial commenced.

The longitudinal data were collected through four surveys. In the fall (September) of the student’s 7th grade school year, a pre-intervention questionnaire (Wave 1) was administered to youth. In January of the same school year, youth completed a short-term questionnaire (Wave 2; 4 months after Wave 1). The Wave 3 survey was administered in May (8 months after Wave 1), and the Wave 4 survey was administered in May of the following school year – the youth’s 8th grade year (20 months after Wave 1). The questionnaires typically took 30 minutes to complete. The questionnaires collected information on sociodemographic characteristics, parenting practices, parent-child communication, and parenting self-efficacy. No adverse events or unintended effects were reported by any study participant (youth or parent).

The sample size was determined under the assumption of the low level of clustering for the main outcomes based on our experience from similar projects in the past. With 180 child-parent dyads for each treatment group (540 in total), our study is appropriately powered to detect effects on the small-medium range for a desired power of 0.80 and a Type I error rate of 0.05.

With the full sample of 532 participants, the retention rates varied between adolescents and their parents. For parents, it was stable over time (Wave 2=82%; Wave 3=83%; Wave 4=79%) and between conditions (PY=80%; PO=85%; C=79%). For adolescents, the retention rates were higher (Wave 2=97%; Wave 3=97%; Wave 4=90%) and remained stable by condition (PY=93%; PO=95%; C=96%). For analysis, 24 participants who did not receive a free lunch at baseline were excluded from the sample to make the sample socioeconomically homogenous, which yielded the final sample size of 508 participants with 180 in PY, 152 in PO and 176 in C.

Intervention delivery

For youth, regular teachers delivered kiR in the school classroom over the course of 10 weeks (one lesson per week). In addition to teaching drug resistance strategies, the manualized curriculum provides opportunities for students to discuss the importance of their families, communities, and culture (Parsai, Castro, Marsiglia, Harthun, & Valdez, 2011). All parents, regardless of condition, met once a week for 8 weeks (one lesson per week) at the school their youth attended. Trained bi-lingual facilitators delivered the manualized curriculum. Parent participants were majority female (91%), Latino (98%), foreign-born (97%), and married or cohabitating (83%). Parents had the option of attending English only or Spanish only workshops; however, because this curriculum was designed for Latino parents, the majority of groups occurred in Spanish only. On average, parents attended 6 out of 8 workshops with 52% attending all workshops

Measurements of the main outcomes and the covariates

Main outcome variables:

In all four-survey waves, adolescents reported the amount and frequency of the use of alcohol, inhalants, cigarettes, and marijuana in the last 30 days prior to each wave. However, approximately 95% of the participants had never used inhalants, cigarettes, or marijuana at all four waves (see Table 1), and the level of alcohol use was relatively low as well (approximately 10% at all waves). Hence, the outcomes were dichotomized to indicate whether a participant used each substance or not in the last 30 days prior to each wave. Another outcome variable was created to indicate whether a participant used any of those substances prior to each wave.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Outcomes and Youth Characteristics by Intervention

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Condition | % or mean (SE) | % or mean (SE) | % or mean (SE) | % or mean (SE) |

| Substance usesa | |||||

| Any substance | PY | 9.8% | 10.7% | 15.1% | 14.1% |

| PO | 8.0% | 15.2% | 11.3% | 8.6% | |

| C | 10.9% | 14.6% | 14.9% | 20.0% | |

| Alcohol | PY | 6.1% | 7.0% | 12.1% | 12.3% |

| PO | 6.0% | 8.6% | 8.8% | 5.3% | |

| C | 8.0% | 12.8% | 11.0% | 16.2% | |

| Inhalant | PY | 5.9% | 2.3% | 6.1% | 4.5% |

| PO | 4.6% | 8.3% | 5.8% | 2.8% | |

| C | 4.6% | 5.2% | 4.5% | 2.3% | |

| Cigarette | PY | 4.0% | 0.8% | 3.0% | 4.5% |

| PO | 3.3% | 3.1% | 2.0% | 2.2% | |

| C | 1.7% | 3.4% | 1.1% | 1.5% | |

| Marijuana | PY | 3.4% | 2.6% | 5.3% | 5.5% |

| PO | 3.9% | 7.5% | 4.1% | 3.9% | |

| C | 1.1% | 2.5% | 2.8% | 5.1% | |

| Adolescent characteristicsb | |||||

| Age | PY | 12.60 (0.03) | - | - | - |

| PO | 12.79 (0.04) | - | - | - | |

| C | 12.49 (0.03) | - | - | - | |

| Female | PY | 43.9% | - | - | - |

| PO | 48.0% | - | - | - | |

| C | 48.3% | - | - | - | |

| Foreign-born | PY | 18.5% | - | - | - |

| PO | 23.2% | - | - | - | |

| C | 17.9% | - | - | - | |

| Grade | PY | 5.87 (0.12) | - | - | - |

| PO | 5.95 (0.12) | - | - | - | |

| C | 5.83 (0.12) | - | - | - | |

| N | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 | |

Notes: numbers based on 20 datasets with imputed data by using mi estimate command in Stata 14.2; % is reported if dichotomous and mean (SE) is reported if continuous;

no significant differences among three intervention conditions at wave 1;

no significant differences in youth characteristics among three intervention conditions except age; all variables were controlled for in the main model.

Covariates:

Youth characteristics at the baseline were controlled for in the GEE model: age (years) and foreign-born status (born in a country other than the U.S. or not) of youth and parent; school grade (mostly Bs or not) and cohort membership (2013-14, 2014-15, or 2015-16) of youth; the intervention condition assigned to a participant (PO, PY, or C).

Statistical method

To deal with missingness in the data and maximize the statistical power, a multiple imputation (MI) method (mi impute chained command in Stata 14.2) produced twenty datasets with no missing information. Auxiliary variables correlated moderately or highly with substance use were included in the imputation model.

To analyze the twenty datasets created by the imputation, we used a generalized estimating equation (GEE) in Stata 14.2 to deal with the correlations between observations. No specific variance-covariance structure (unstructured) was assumed, and time was considered as categorical. To compute the predicted probabilities of the outcomes, we used the user-written mimrgns command. In all models, age and foreign-born status of youth and parent; gender, school grade, cohort membership of youth; education of parent were included as covariates in addition to dummy variables indicating intervention conditions. In addition, Cohen’s h was calculated to determine the effect sizes (Cohen 1998). The general interpretations of h recommended by Cohen (1998) was used as a rule of thumb to assess effect sizes: small effect (h=.20), medium effect (h=.50) and large effect (h=.80).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the demographic characteristics of adolescents and the outcome variables. The adolescent characteristics show that across the three conditions there were more males than females. On average, the adolescents in the sample were about 13 years old with the school grade of the average grade B (in the range of mostly A’s (=8) and mostly F’s (=0)), and about one in five adolescents were born outside of the U.S.

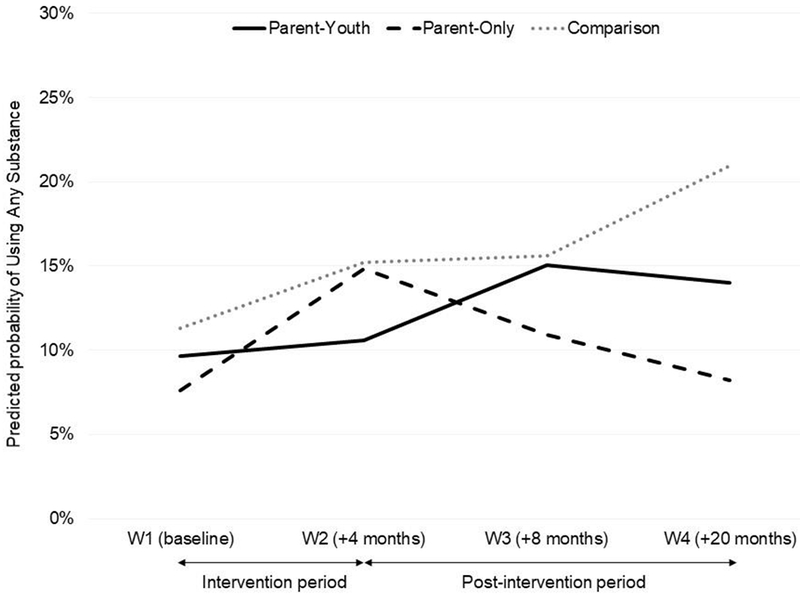

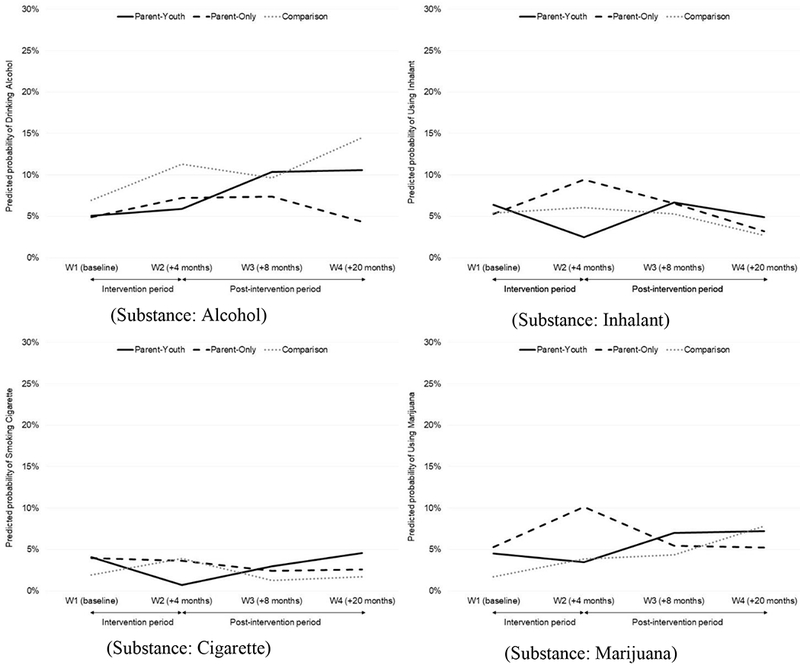

In the next step of the analysis, we examined the trajectories of use of any substance, alcohol, inhalants, cigarettes, and marijuana over time for all three conditions. In all models, time was considered as categorical to compare all possible pairs of four waves in each condition. The predicted probabilities of substance use are visualized in Figure 2 (any substance use) and in Figure 3 (alcohol, inhalant, cigarette, and marijuana, separately). Table 2 summarizes the test results of the differences across four waves within each intervention condition. Table 3 summarizes the differences between the three intervention conditions at each wave.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probabilities of Using Any Substance Before and After Intervention by Conditions

Note: a hypothetical 13-year old US-born male student who participated in the 2014 intervention with the average grade B; all estimates are based on the GEE results by using mi estimate and mimrgns commands in Stata 14.2.

Figure 3.

Predicted Probabilities of Using Substances Before and After Intervention by Conditions

Note: a hypothetical 13-year old US-born male student who participated in the 2014 intervention with the average grade B; all estimates are based on the GEE results by using mi estimate and mimrgns commands in Stata 14.2.

Table 2.

Contrasts between Four Waves by Conditions

| Parent-Youth (PY) | Parent-Only (PO) | Comparison (C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | 95% C.I. | Contrast | 95% C.I. | Contrast | 95% C.I. | |

| Outcome: Any substance | ||||||

| 1 vs 2 | 0.009 | [−0.051; 0.070] | 0.072 | [0.017; 0.127] | 0.039 | [−0.019; 0.098] |

| 1 vs 3 | 0.054 | [−0.006; 0.114] | 0.033 | [−0.015; 0.081] | 0.043 | [−0.020; 0.106] |

| 1 vs 4 | 0.044 | [−0.019; 0.107] | 0.006 | [−0.047; 0.059] | 0.097 | [0.017; 0.176] |

| 2 vs 3 | 0.045 | [−0.021; 0.111] | −0.039 | [−0.091; 0.012] | 0.004 | [−0.061; 0.068] |

| 2 vs 4 | 0.034 | [−0.032; 0.101] | −0.066 | [−0.129; −0.003] | 0.057 | [−0.024; 0.138] |

| 3 vs 4 | −0.010 | [−0.072; 0.052] | −0.027 | [−0.082; 0.028] | 0.054 | [−0.016; 0.123] |

| Outcome: Alcohol | ||||||

| 1 vs 2 | 0.008 | [−0.034; 0.050] | 0.023 | [−0.015; 0.061] | 0.044 | [−0.009; 0.097] |

| 1 vs 3 | 0.053 | [0.000; 0.106] | 0.025 | [−0.012; 0.062] | 0.027 | [−0.019; 0.074] |

| 1 vs 4 | 0.055 | [−0.001; 0.111] | −0.006 | [−0.046; 0.035] | 0.076 | [0.011; 0.141] |

| 2 vs 3 | 0.045 | [−0.011; 0.100] | 0.002 | [−0.040; 0.044] | −0.017 | [−0.067; 0.034] |

| 2 vs 4 | 0.047 | [−0.012; 0.106] | −0.029 | [−0.070; 0.013] | 0.032 | [−0.035; 0.099] |

| 3 vs 4 | 0.002 | [−0.051; 0.055] | −0.031 | [−0.073; 0.011] | 0.049 | [−0.006; 0.103] |

| Outcome: Inhalant | ||||||

| 1 vs 2 | −0.039 | [−0.091; 0.013] | 0.042 | [−0.015; 0.098] | 0.007 | [−0.033; 0.047] |

| 1 vs 3 | 0.003 | [−0.047; 0.052] | 0.013 | [−0.035; 0.060] | −0.001 | [−0.047; 0.045] |

| 1 vs 4 | −0.015 | [−0.063; 0.033] | −0.021 | [−0.067; 0.026] | −0.027 | [−0.071; 0.017] |

| 2 vs 3 | 0.042 | [−0.011; 0.094] | −0.029 | [−0.072; 0.015] | −0.008 | [−0.052; 0.036] |

| 2 vs 4 | 0.024 | [−0.027; 0.075] | −0.062 | [−0.116; −0.009] | −0.034 | [−0.077; 0.010] |

| 3 vs 4 | −0.018 | [−0.060; 0.024] | −0.034 | [−0.075; 0.007] | −0.026 | [−0.066; 0.014] |

| Outcome: Cigarette | ||||||

| 1 vs 2 | −0.033 | [−0.076; 0.009] | −0.003 | [−0.037; 0.031] | 0.020 | [−0.017; 0.057] |

| 1 vs 3 | −0.011 | [−0.047; 0.025] | −0.016 | [−0.040; 0.009] | −0.006 | [−0.034; 0.021] |

| 1 vs 4 | 0.005 | [−0.032; 0.041] | −0.013 | [−0.053; 0.026] | −0.002 | [−0.033; 0.028] |

| 2 vs 3 | 0.023 | [−0.010; 0.055] | −0.012 | [−0.048; 0.023] | −0.027 | [−0.064; 0.011] |

| 2 vs 4 | 0.038 | [−0.013; 0.089] | −0.010 | [−0.045; 0.024] | −0.022 | [−0.063; 0.018] |

| 3 vs 4 | 0.016 | [−0.028; 0.059] | 0.002 | [−0.032; 0.037] | 0.004 | [−0.024; 0.032] |

| Outcome: Marijuana | ||||||

| 1 vs 2 | −0.010 | [−0.051; 0.030] | 0.048 | [−0.003; 0.099] | 0.021 | [−0.016; 0.059] |

| 1 vs 3 | 0.025 | [−0.017; 0.068] | 0.002 | [−0.025; 0.029] | 0.026 | [−0.021; 0.073] |

| 1 vs 4 | 0.027 | [−0.020; 0.075] | −0.001 | [−0.049; 0.047] | 0.061 | [−0.002; 0.125] |

| 2 vs 3 | 0.035 | [−0.014; 0.085] | −0.046 | [−0.098; 0.005] | 0.005 | [−0.043; 0.053] |

| 2 vs 4 | 0.038 | [−0.020; 0.095] | −0.049 | [−0.108; 0.010] | 0.040 | [−0.027; 0.107] |

| 3 vs 4 | 0.002 | [−0.050; 0.054] | −0.003 | [−0.045; 0.039] | 0.035 | [−0.022; 0.091] |

Note: Bold if significant at the .05 level of significance; underlined if significant at the .10 level of significance; a hypothetical 13-year old US-born male student who participated in the 2014 intervention with the average grade B; all contrasts are based on the GEE results by using mi estimate and mimrgns commands in Stata 14.2.

Table 3.

Contrasts between Conditions at Each Wave

| C vs. PY | C vs. PO | PO vs. PY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | 95% C.I. | Contrast | 95% C.I. | Contrast | 95% C.I. | |

| Outcome: Any substance | ||||||

| W1 | 0.016 | [−0.050; 0.082] | 0.037 | [−0.029; 0.103] | −0.021 | [−0.084; 0.042] |

| W2 | 0.046 | [−0.033; 0.125] | 0.004 | [−0.078; 0.086] | 0.042 | [−0.037; 0.121] |

| W3 | 0.005 | [−0.074; 0.084] | 0.047 | [−0.031; 0.125] | −0.042 | [−0.119; 0.036] |

| W4 | 0.069 | [−0.019; 0.158] | 0.127 | [0.035; 0.219] | −0.058 | [−0.134; 0.017] |

| Outcome: Alcohol | ||||||

| W1 | 0.018 | [−0.029; 0.065] | 0.020 | [−0.029; 0.069] | −0.002 | [−0.047; 0.043] |

| W2 | 0.054 | [−0.010; 0.118] | 0.041 | [−0.024; 0.106] | 0.013 | [−0.041; 0.067] |

| W3 | −0.007 | [−0.069; 0.054] | 0.022 | [−0.038; 0.082] | −0.030 | [−0.093; 0.033] |

| W4 | 0.039 | [−0.033; 0.111] | 0.102 | [0.028; 0.175] | −0.062 | [−0.124; −0.001] |

| Outcome: Inhalant | ||||||

| W1 | −0.010 | [−0.064; 0.043] | 0.001 | [−0.054; 0.056] | −0.011 | [−0.069; 0.046] |

| W2 | 0.036 | [−0.016; 0.088] | −0.034 | [−0.101; 0.033] | 0.070 | [0.005; 0.134] |

| W3 | −0.014 | [−0.067; 0.039] | −0.013 | [−0.071; 0.045] | −0.001 | [−0.061; 0.059] |

| W4 | −0.022 | [−0.070; 0.026] | −0.005 | [−0.048; 0.037] | −0.017 | [−0.069; 0.035] |

| Outcome: Cigarette | ||||||

| W1 | −0.022 | [−0.063; 0.020] | −0.020 | [−0.061; 0.020] | −0.001 | [−0.048; 0.045] |

| W2 | 0.032 | [−0.009; 0.073] | 0.003 | [−0.044; 0.050] | 0.029 | [−0.011; 0.070] |

| W3 | −0.017 | [−0.050; 0.016] | −0.011 | [−0.042; 0.020] | −0.006 | [−0.045; 0.033] |

| W4 | −0.029 | [−0.076; 0.019] | −0.009 | [−0.047; 0.029] | −0.020 | [−0.070; 0.031] |

| Outcome: Marijuana | ||||||

| W1 | −0.028 | [−0.074; 0.018] | −0.036 | [−0.084; 0.012] | 0.008 | [−0.048; 0.064] |

| W2 | 0.004 | [−0.044; 0.052] | −0.063 | [−0.134; 0.008] | 0.067 | [−0.002; 0.135] |

| W3 | −0.027 | [−0.085; 0.031] | −0.011 | [−0.070; 0.048] | −0.015 | [−0.082; 0.051] |

| W4 | 0.006 | [−0.062; 0.074] | 0.026 | [−0.050; 0.102] | −0.020 | [−0.088; 0.048] |

Note: Bold if significant at the .05 level of significance; underlined if significant at the . 10 level of significance; a hypothetical 13-year old US-born male student who participated in the 2014 intervention with the average grade B; all contrasts are based on the GEE results by using mi estimate and mimrgns commands in Stata 14.2.

Outcome: any substance use:

Figure 2 shows the predicted probability of any substance use at each wave during the period of the Wave 1 (0 month) to Wave 4 (20 months post-baseline) in three intervention conditions. The results indicate that the chance of using substances increased for those adolescents in the C condition over time (see Table 2). In detail, adolescents had a significantly higher probability of using any substance at Wave 4 compared to Wave 1 (contrast=.097; 9.7% increase; Cohen’s h=.265), and it was significant at thep-value .05 level. On the contrary, adolescents in the PO condition showed a significant increase in the predicted probabilities between Wave 1 and 2 (contrast=.072; 7.2% increase; Cohen’s h=.232), but then a significant decrease post-intervention, between Wave 2 and 4 (contrast=−.066; 6.6% decrease; Cohen’s h=.210). There was no significant change over time for the adolescents in the PY condition, indicating the probability of using substances remained stable over 20 months. Lastly, there was a significant difference between conditions at Wave 4 between PO and C (See Table 3). The predicted probability of using substances at Wave 4 was significantly higher in the C condition compared to the PO condition (contrast=.127; 12.7% higher; Cohen’s h=.369). The results show no significant differences between C and PY and between PO and PY at any wave.

Outcome: alcohol, inhalant, cigarette, and marijuana use:

Looking at the results for each substance individually revealed that two substances, alcohol and inhalant use, drove the overall trajectory of any substance use. Figure 3 shows the predicted probability of alcohol, inhalant, cigarette, and marijuana use, respectively, during the period of Wave 1 (0 month) to Wave 4 (20 months post-baseline) in all the intervention conditions. The results for alcohol use in the C condition resembled those for any substance use; however, differences diverge for the PY and PO conditions (see Table 2). The predicted probability of alcohol use for those in the C condition significantly increased between Wave 1 and 4 (contrast=.076; 7.6% increase; Cohen’s h=.249). The increasing patterns were also found for those in the PY condition between Wave 1 and 3 (contrast=.053; 5.3% increase; Cohen’s h=.202). For the PO condition, there was no substantial increase or decrease in the predicted probability of alcohol use over time. For the use of inhalants, cigarettes, and marijuana, the only significant difference was found for inhalant use in the PO condition. The predicted probability of inhalant use at Wave 4 was significantly lower than at Wave 2 in this condition (contrast=−.062; −6.2% decrease; Cohen’s h=.265). Last, the differences across conditions at each wave were also tested for alcohol, inhalant, cigarette, and marijuana use (see Table 3). Again, the results of alcohol and inhalant use mimic the patterns for any substance use. In detail, the predicted probability of using alcohol at Wave 4 was significantly higher in the C condition compared to the PO condition (contrast=.102; 10.2% difference; Cohen’s h=.361). At Wave 4, there was also a significant difference between the PO and PY conditions as well (contrast=−.062; 6.2% lower in the PO condition; Cohen’s h=.243). For inhalant use, there was a significant difference between the PO and PY conditions at Wave 2 (contrast=−.070; 7% higher in the PO condition; Cohen’s h=.307). For cigarette and marijuana use, there was no significant difference at any wave though a couple of marginally significant differences between conditions were found, particularly for marijuana use.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of two culturally grounded prevention interventions, keepin’ it REAL (kiR) for Latino youth and Families Preparing the New Generation (FPNG) for their parents, on the adolescence substance use over twenty months. The parents-only (PO) intervention condition involved only parents, and the parent-youth (PY) condition involved both parents and youth. The eco-developmental theory led to the first hypothesis that both intervention conditions would be better than the comparison (C) condition that did not receive either kiR or FPNG. As a next step, we examined possible differences between PO and PY to determine if there was a preferred delivery method for prevention interventions for Latino adolescents.

The overall patterns of substance use among Latino youth estimated by the generalized estimating equation (GEE) models show a significant effect of the PO intervention post-intervention (between Waves 2 and 4). When use of specific substances was individually examined, we found that the PO intervention significantly reduced any substance use sixteen months after the implementation of the intervention and alcohol and inhalant use mainly drove this pattern. This suggests that when parents are the intervention messaging delivery system to their adolescents, adolescent substance use behaviors change but not immediately. There were not significant decreases at Wave 2, immediately post-intervention. In fact, the adolescents in the PO condition had significant increases in overall substance use between Wave 1 and 2. However, over time, the impact of the parenting intervention materialized, and adolescents in the PO condition showed a lower probability of using alcohol and inhalant at Wave 4 compared to their peers randomly assigned to the other conditions. These trends confirm developmental findings about substance use experimentation and initiation between the ages of 12 and 14 (Marsiglia, Ayers, Baldwin-White, & Booth 2016). As other parenting programs, FPNG appears to have effectively empowered parents to have a more active role in helping their children delay or avoid initiation into alcohol and other drugs (Van Ryzin, Roseth, Fosco, Lee & Chen 2016). Children in the comparison condition, and to a lesser degree in the youth and parent condition, continued in their upward substance use trajectory while children in the Parent Only condition did not.

The youth in the C condition showed a significant increase in any substance use, particularly for alcohol use, at the 20th month. On the other hand, the PY intervention did not show either an increasing or decreasing trajectory of any substance use over time while alcohol use alone showed an increasing trajectory. While these results are not significant statistically, they are meaningful. The fact that receiving a youth intervention combined with a parenting intervention kept the trajectories stable between the beginnings of 7th grade to the end of 8th grade suggests that these adolescents are not following a normal adolescent trajectory for substance use. Lastly, the PO condition outperformed the C and PY condition, particularly for alcohol use at the 20th month, at the end of 8th grade. In terms of effect size, the Cohen’s h for significant differences were over .20 but less than .50 indicating small intervention effects. While this finding is not entirely expected, it may indicate that the youth intervention, kiR, had possible iatrogenic effects, as seen in other parent and youth interventions (Dishion & Andrews 1995; Handwerk, Field, & Friman 2000). This may be a function of the microsystem within the school setting (Handwerk, Field, and Friman 2000), an unintended consequence of grouping adolescents together to talk about antisocial behaviors (Dishion & Andrews 1995), or that some of the scenarios and role playing activities in kiR are antiquated with newer generations of adolescents.

Overall, the results provide some evidence supporting the long-term effectiveness of the intervention involving only parents. This is in line with the major finding of the recent meta-analysis research focusing on interventions aiming to reduce substance use of Latino adolescents (Robles, Maynard, Salas-Wright, & Todic 2016). Similar to our results, the meta-analysis using the 10 selected intervention studies show that the intervention effects were, on average, small or clinically insignificant at the end of the intervention while the effects were also significant but lager at the follow-up months after the implementation of the intervention.

Although the combined PY condition was successful in maintaining the substance use relatively constant at a low level, the PO condition had a stronger desirable effect on the youth. Parents knew that their children were not receiving the classroom-based intervention and that they had a main prevention role to play. They were not able to delegate the prevention role to the teacher or the school but instead became empowered to take the lead while receiving the needed support to do it effectively. These findings suggest that an intervention aiming at reducing adolescent substance use among Latino youth could be effective by intervening only with parents. In addition, Latino children could benefit from interventions that strengthen the cultural assets of their parents. A strong match between the intervention and the culture of origin of parents can yield meaningful intervention effects on the youth.

There are three major limitations of the study. The first limitation is a relatively small sample size. There might be not enough statistical power to detect very small differences across the conditions. In fact, some results are marginally significant (.05<p-value<.10) though the differences were in expected direction (see Table 2 and 3). The computed Cohen’s hs for those marginally significant contrasts varied in the range of .165 and .304. Despite this limitation, the results show some critical differences between intervention conditions and across time points within each intervention. Second, because these are universal prevention interventions, all youth participated regardless of an indicated need for substance use prevention (e.g., a youth was at high-risk for using substances). Thus, most of the participants reported no use of each substance, which consequently limited further statistical analysis on how our culturally adapted intervention influenced the trajectory of frequency and amount of substance use, which would contribute to better understanding the substance use trajectories of Latino youth and how to prevent substance use more effectively in this population. Third, the participants in this study were majority immigrant families living in predominantly low socioeconomic status Latino neighborhoods in the Southwestern U.S. These findings may not representative of the total population of students or be generalizable to Latino families across the U.S.

Conclusion

The study assessed the effectiveness of simultaneously implementing two culturally grounded interventions, kiR and FPNG, on Latino youth’s substance use. In addition to studying the overall effects of the interventions, we focused on whether or not the intervention involving only parents would lead to better outcomes than the intervention involving both youth and their parents. The analysis results show some evidence suggesting that youth benefit the most when their parents alone receive the intervention. We argue that the finding provide credence to the assumption that recent immigrant Latino parents become more involved in prevention when they know their children’s teachers are not involved. It supports a reinterpretation of the eco-developmental theory by being more specific about the role each ecosystem plays across the acculturation continuum. The higher involvement of medium to low acculturation parents -when randomly assigned to the PO condition- may have not being as effective among highly acculturated Latino parents. Our sample does not allowed us to test this assumption but future studies need to include a more diverse acculturation status sample.

These findings are not implying that there is no need for classroom-based prevention for Latino youth. On the contrary, we recommend the implementation of more classroom-based universal prevention programs. The findings, however, highlight an opportunity to capitalize on the assets recent immigrant parents have. Prevention science needs to recognize and support the prevention role of different parents of diverse backgrounds in promoting the wellbeing of their children. Our findings suggest that a better understanding of the cultural background of the target population, including their acculturation status; will lead to more effective prevention intervention research and practice. This example of “precision prevention” suggests that to effectively reach different subgroups of youth and advance health equity we may need to engage key ecosystems to different degrees.

Acknowledgement:

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMHD or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All study procedures involving human participants were approved by the Arizona State University’s Institutional Review Board and in accordance with standards for ethical research practice, including the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent: Participants were informed of their rights and parental informed consent coupled with youth assent was obtained prior to any data collection.

References

- Austin AM, Macgowan MJ, & Wagner EF (2005). Effective Family-Based Interventions for Adolescents With Substance Use Problems: A Systematic Review. Research on Social Work Practice, 15(2), 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, & Jones RM (2010). Neurobiology of The Adolescent Brain And Behavior: Implications for Substance Use Disorders. Journal of American Academy of Child &Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(12), 1189–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From The 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 16-4984, NSDUH Series H-51). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-united-states-results-2015-national-survey

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018a). Fact Sheets- Alcohol Use and Youth Health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018b). Fact Sheets- Underage Drinking. Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/underage-drinking.htm [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, & Jacobson KC (2012). Developmental Trajectories of Substance Use from Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Gender and Racial/Ethnic Differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(2), 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Copello AG, Templeton L, & Velleman R (2006). Family interventions for drug and alcohol misuse: is there a best practice?. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(3), 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gaetano Y (2007). The role of culture in engaging Latino parents’ involvement in school. Urban Education, 42(2), 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- George SMS, Parra-Cardona JR, Vidot DC, Molleda LM, Terán AQ, Onetto DC, Gibbons JB, & Prado G (2017). Cultural Adaptation of Preventive Interventions in Hispanic Youth In Schwartz SJ & Unger J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health (pp. 393–410) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Germán M, Gonzales NA, & Dumka L (2009). Familism Values as a Protective Factor for Mexican-Origin Adolescents Exposed to Deviant Peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(1), 16–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, & Iritani B (2004). Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerk ML, Field CE, & Friman PC (2000). The iatrogenic effects of group intervention for antisocial youth: Premature extrapolations? Journal of Behavioral Education, 10(4), 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, & Dustman PA (2003). Culturally-grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science, 4, 233–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Robles E, Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, & Todic J (2016). Culturally Adapted Substance Use Interventions for Latino Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2018). Monitoring the Future, National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2017: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Demographic Subgroup Trends among Adolescents in the Use of Various Licit and Illicit Drugs, 1975-2016. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, & Ethier KA (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc G, Darnell A, & Alvarez-Jimenez A (2008). Parent involvement in the academic adjustment of Latino middle and high school youth: Teacher expectations and school belonging as mediators. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4), 469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EJ (2015). Adolescent Alcohol Use: Risks and Consequences. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 49(2), 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, & Hecht ML (2005). Keepin’it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR Associates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Ayers SL, & Kiehne E (in press). Reducing inhalant use in Latino adolescents through synchronized parent-adolescent interventions. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Ayers SL, Baldwin-White A, & Booth J (2016). Changing Latino Adolescents’ Substance Use Norms and Behaviors: The Effects of Synchronized Youth and Parent Drug Use Prevention Interventions. Prevention Science, 17(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Williams LR, Ayers SL, & Booth JM (2014). Familias: Preparando la Nueva Generación: A Randomized Control Trial Testing the Effects on Positive Parenting Practices. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(3), 310–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MJ, Huang S, Estrada Y, Sutton MY, & Prado G (2017). The Relationship Between Acculturation, Ecodevelopment, and Substance Use Among Hispanic Adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(7), 948–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, Piquero AR, Slutske WS, Milne BJ, Dickson N, Poulton R, & Moffitt TE (2008). Is It Important to Prevent Early Exposure to Drugs and Alcohol among Adolescents?. Psychological Science, 19(10), 1037–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, & Szapocznik J (2003). Preventing Substance Abuse in Hispanic Immigrant Adolescents: An Ecodevelopmental, Parent-Centered approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(4), 469–500. [Google Scholar]

- Parsai MB, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, & Valdez H (2011). Using Community Based Participatory Research to Create A Culturally Grounded Intervention for Parents and Youth to Prevent Risky Behaviors. Prevention Science, 12(1), 34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai MB, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, & Valdez H (2011). Using Community Based Participatory Research to Create A Culturally Grounded Intervention for Parents and Youth to Prevent Risky Behaviors. Prevention Science, 12(1), 34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena DC (2000). Parent Involvement: Influencing Factors and Implications. Journal of Educational Research, 94(1), 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cree WK, & Specter MM (2002). Ethnic Culture, Poverty, and Context: Sources of Influence on Latino Families and Children. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schinke S, Brounstein P, & Gardner S (2002). Science-based prevention programs and principles, 2002, DHHS Pub No. (SMA) 03-3764, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, & Prestopnik JL (2005). Ecologically based family therapy outcome with substance abusing runaway adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 28(2), 277–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit E, Verdurmen J, Monshouwer K, & Smit F (2008). Family interventions and their effect on adolescent alcohol use in general populations; a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 97(3), 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkler B (2002). A Review of Literature on Hispanic/Latino Parent Involvement in K-12 Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED469134.pdf ED469134.

- Van Ryzin MJ, Roseth CJ, Fosco GM, Lee YK, & Chen IC (2016). A Component-Centered Meta-Analysis of Family-Based Prevention Programs for Adolescent Substance Use. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Ayers S, Baldwin A, & Marsiglia FF (2016). Delaying Youth Substance-Use Initiation: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of Complementary Youth and Parenting Interventions. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(1), 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Marsiglia FF, Baldwin A, & Ayers S (2015). Unintended Effects of an Intervention Supporting Mexican-Heritage Youth: Decreased Parent Heavy Drinking. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(2), 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate ME (2007). Understanding Latino Parental Involvement in Education: Perceptions, Expectations, and Recommendations. Tomas Rivera Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED502065.pdf [Google Scholar]