Abstract

A simple technique for the preparation of [18F]HF has been developed and applied to the generation of an [18F]FeF species for opening sterically hindered epoxides. This method has been successfully employed to prepare four drug-like molecules, including 5-[18F]fluoro-6-hydroxy-cholesterol, a potential adrenal/endocrine PET imaging agent. This easily automated one-pot procedure produces sterically hindered fluorhydrin PET imaging agents in good yields and high molar activities.

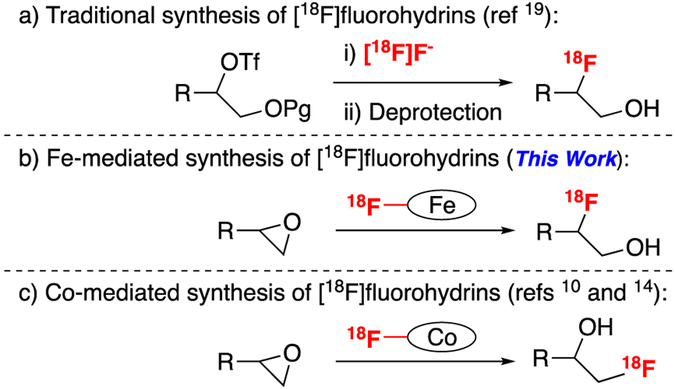

Fluorine-18 is one of the most common radionuclides for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. At present the vast majority of synthetic methods for carbon–fluorine-18 bond formation utilize [18F]KF as the fluoride source in combination with a phase transfer reagent (e.g. Kryptofix-222, (K2.2.2) or quaternary ammonium salt),1 or in newly developed methods for late-stage fluorination.2 However, HF is also a potentially attractive fluorinating reagent, and it has a unique reactivity profile relative to [18F]KF. In addition, it is commonly used as a reagent for the synthesis of metal fluoride salts from basic metal salt precursors.3 Despite these features, [18F]HF has seldom been utilized for the synthesis of PET imaging agents.4–10 This is surprising because it is a historically important reagent for fluorinating organic molecules and was used to prepare the first two fluorine-containing drugs, fludrocortisone and dexamethasone.11–13 In particular, the production of fluorohydrin, a motif found in a variety of known radiotracers, via epoxide opening has remained a challenge in radiochemistry.14–16 Indeed, many tracers that would be straightforward to synthesize in a single step through an epoxide opening with [18F]HF are instead prepared via a two-step substitution/deprotection process (Figure 1a).17–24 We hypothesized that ready access to [18F]HF, as well as [18F]HF-derived metal 18F-fluoride species, could overcome the longstanding challenge of opening epoxides in PET radiochemistry. In this work, we demonstrate a method to prepare [18F]HF from nucleophilic [18F]fluoride ([18F]F-) that is compatible with automated synthesis modules. This [18F]HF is then used to generate an [18F]FeF species that is effective for the opening of epoxides in the context of drug-like molecules (Figure 1b). This new method typically incorporates fluoride at the more substituted side of the epoxide and appears to work best with strained sites such as epoxy steroids. This is complementary to recent (salen)CoF methods developed separately by both Zhuravlev and Doyle which were regioselective for the less-substituted fluoride, typically on terminal epoxides (Figure 1c). 10,14

Figure 1:

Strategies for synthesizing [18F]fluorohydrins (Pg = Protecting group)

Previous work from our group has shown that [18F]F- trapped on a quaternary methylammonium (QMA) cartridge can be eluted using a solution of an organic base (e.g. DMAP, DBU) to provide a reactive and soluble source of [18F]F- without the need for an inorganic base (K2CO3) or K2.2.2.25 The efficiency of [18F]F- elution was found to be dependent on the pKa of the organic base. This procedure was applied to the improvement of radiochemical transformations in which inorganic bases or K2.2.2 had a deleterious effect. The successful elution of [18F]F- under these conditions prompted us to investigate the use of acidic solutions in either H2O or an organic solvent as eluting media for the recovery of [18F]HF from a QMA cartridge.

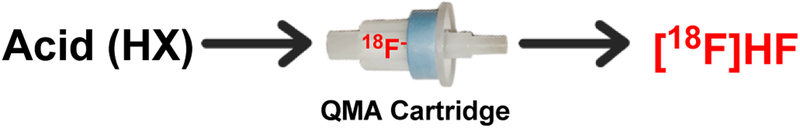

To this end, we initially determined the [18F]HF elution efficiency of a variety of acids with a pKa range of −2.6 to 4.86, using the elution process outlined in Figure 2. This procedure provides a straightforward, automatable route to an acidic solution of [18F]HF. As anticipated, the elution efficiency is dependent on the acid pKa, with stronger acids (i.e. lower pKa values) showing higher efficiency in comparison to weaker acids (Table 1). As [18F]F- in aq. solution is considered relatively inert as a nucleophile due to hydration, it is typical to remove water from, for example, [18F]KF by azeotropic drying with MecN.1,2 However, since [18F]HF is inherently volatile, one reason for its limited use to date, we reasoned that it would be incompatible with the azeotropic drying typically employed for [18F]KF. Therefore we were gratified to next determine that [18F]HF could be prepared without the need for azeotropic drying by using a solution of acid (e.g. TFA or CH3SO3H) in different polar organic solvents commonly used in radiofluorination reactions (DMF, DMA, EtOH and MeCN) as the eluent (see Supporting Information for full details).

Figure 2:

Elution to prepare [18F]HF from [18F]fluoride produced by a small medical cyclotron.

Table 1:

[18F]F− Elution efficiency for acids at 0.5 M in H2O, elution of [18F]HF correlated to pKa and valency of the acid.

| Acid | pKa | Elution Efficiency |

Acid | pKa | Elution Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeSO3H | −2.6 | 93% | (NH4)2EDTA | 2.00 | 92% |

| pTosOH | −0.51 | 90% | H3PO4 | 2.12 | 88% |

| TFA | −0.25 | 91% | ClCH2CO2H | 2.86 | 58% |

| CCl3CO2H | 0.65 | 84% | Citric acid | 3.13 | 37% |

| Oxalic acid | 1.23 | 81% | 2-OH-isobutyric acid | 3.86 | 6% |

| CHCl2CO2H | 1.29 | 73% | Ascorbic acid | 4.17 | 12% |

| KHSO4 | 1.99 | 86% | AcOHa | 4.86 | 0% |

Neat AcOH (0.5 mL) was used to elute the QMA.

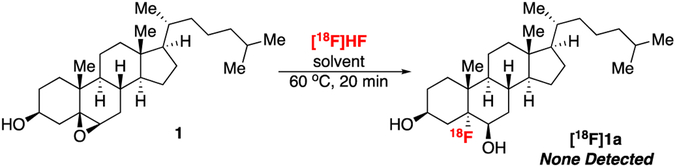

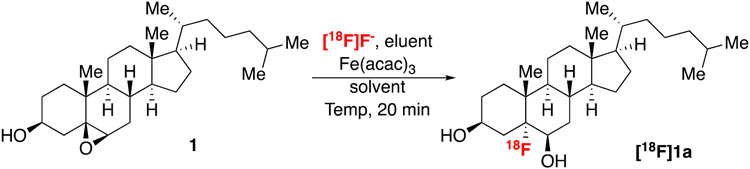

We next sought to apply [18F]HF to the opening of epoxides. 5-[18F]Fluoro-6-hydroxy-cholesterol ([18F]1a) is a target of particular interest given the long history of adrenal imaging at the University of Michigan, as well as our desire to develop a PET imaging agent for examining cholesterol metabolism to replace the single-photon emission computed tomography agent 131I-labeled NP-59.26-31 Preliminary studies showed that the direct reaction of 1 with [18F]HF (generated by elution of [18F]F- with TFA or MeSO3H) did not lead to conversion of 1 to the fluorohydrin [18F]1a under any conditions examined (Scheme 1). We hypothesize that this low reactivity is due to the need for an excess of HF in such reactions.32–36 This stoichiometry is not accessible in radiofluorination reactions since [18F]HF is the limiting reagent.

Scheme 1:

Attempted synthesis of [18F]1a using [18F]HF (solvent = DMF, CHCl3, PhMe)

Inspired by methods described by Kemnitz3 and Wolf,5,6 we next focused on generating more reactive 18F-metal fluorides from [18F]HF. In particular, Wolf showed that the combination of Sb2O3 and [18F]HF results in metal fluorides with a unique reactivity profile that should complement the traditional, basic conditions of PET radiochemistry. We noted a recent report that used Fe(acac)3, a readily available and stable Fe source, as a catalyst in [19F]HF-mediated epoxide opening.37 In this method, Fe(acac)3 was utilized with anhydrous HF and substrate dissolved in 1,4-dioxane to enable formation of fluorohydrin products that were challenging to access via conventional methods. Building on this precedent, we explored generation of a putative [18F]FeF species from the combination of [18F]HF and Fe(acac)3, and its application to the 18F-fluorination/ring opening of sterically hindered epoxides.

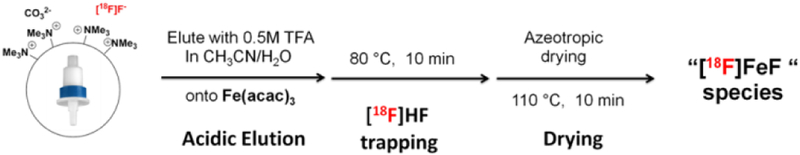

The trapping of [18F]HF solution, obtained after acidic elution of [18F]F- from a QMA cartridge, with Fe(acac)3 was attempted, and this was found to be an effective route to the the putative [18F]FeF species. To adapt this method to an automated, one-pot radiofluorination procedure using [18F]HF, we utilized a GE Tracerlab FxFN module to trap [18F]F- on the QMA, and eluted using a solution of TFA (0.5 M) in MeCN:H2O (4:1). The reactor was then charged with Fe(acac)3, and the [18F]HF and Fe(acac)3 were stirred while heating at 80 °C for 10 min. Subsequent azeotropic drying yielded the putative [18F]FeF species for 18F-fluorination/ring-opening (Figure 3). Following azeotreopic drying, >90% of the radioactivity (decay-corrected and based on activity eluted from the QMA) remained in the reactor, suggesting excellent conversion to the putative [18F]FeF species.

Figure 3:

Preparation of reactive [18F]FeF-species using automated method.

We next applied this [18F]FeF species for the conversion of epoxide 1 to fluorohydrin [18F]1a. This reaction could not be optimized in the traditional sense, because the potential of producing gaseous [18F]HF activity upon evaporation prevented conducting manual reactions and analyzing by radio-TLC.§ As such, the automated reaction was optimized with analysis via radio-HPLC (see Supporting Information for complete details), although we recognize that retention of [18F]F- on HPLC columns can result in overestimation of radiochemical yield (RCY).38 Initial work utilized 0.5 M TFA to elute [18F]HF and, after forming the [18F]FeF species, 1 in dioxane was added, and the epoxide opening reaction was conducted at 100 °C for 20 min to give [18F]1a in 5% RCY¶ (Table 2, entry 1). Lowering the concentration of TFA was found to be detrimental to the reaction (entry 2), as was changing the reaction solvent from dioxane (entry 3). The epoxide opening was also quite sensitive to temperature (entries 4–6). The optimal conditions involved adding the epoxide substrate dissolved in dioxane to the dried [18F]FeF, and then heating the mixture at 120 °C for 20 min under autogenous pressure. Under these conditions, [18F]1a was formed in 22% RCY (entry 5). A similar trend was observed for optimization of the labeling of α-ionone-derived epoxide 2 (Supporting Information). Finally, we note that control reactions using traditional [18F]KF with K2CO3/K2.2.2 yielded no product (Supporting Information).

Table 2:

Optimization of the Synthesis of [18F]1a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | Eluent | Solvent | Temp | RCY¶ |

| 1 | TFA (0.50 M) | Dioxane | 100 °C | 5% |

| 2 | TFA (0.12 M) | Dioxane | 100 °C | 0.2% |

| 3 | TFA (0.50 M) | DMF | 100 °C | 0% |

| 4 | TFA (0.50 M) | Dioxane | 80 °C | 1% |

| 5 | TFA (0.50 M) | Dioxane | 120 °C | 22% |

| 6 | TFA (0.50 M) | Dioxane | 140 °C | <0.1% |

Due to limited synthesis module availability, only single optimization runs were conducted (n = 1).

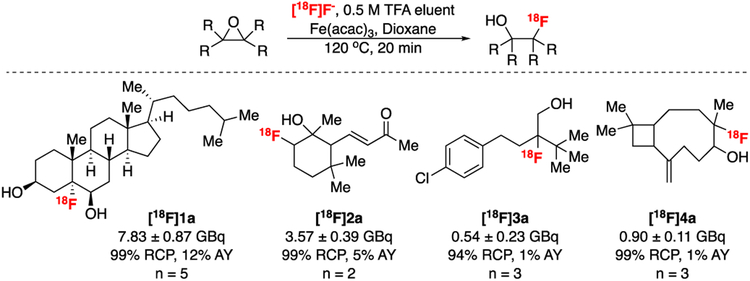

The optimized reaction conditions were applied to the synthesis of a series of 18F-fluorohydrin products ([18F]1a-[18F]4a) using the fully automated procedure. The method proved applicable to the 18F-fluorination of a number of sterically hindered epoxides which have never been radiolabelled before (Figure 4 and Supporting Information).39 Following radiosyntheses, the reaction mixtures were quenched by the addition of HPLC solvent and EDTA, and were then purified by semi-preparative HPLC. The products were isolated in activity yields (AY) ranging from 0.54 ± 0.23 GBq (15 ± 7 mCi; 1% AY; n = 3) for [18F]3a to 7.83 ± 0.87 Gbq (212 ± 25 mCi; 12% AY; n = 5) for [18F]1a, based on starting activity of approx 66.6 GBq (1.8 Ci).|| AY was highest with strained sites such as epoxy steroid [18F]1a. The isolated products exhibited good molar activity (Am), as exemplified by [18F]2a (Am = 56.5 GBq/μmol; 1523 Ci/mmol) and [18F]4a (Am = 63.0 GBq/μmol; 1699 Ci/mmol). The four scaffolds demonstrate the potential utility of this method for preparing new structurally complex fluorohydrin-based PET imaging agents for biological studies. Typically, [18F]Fluoride appears to be incorporated at the more substituted side of the epoxide but, notably, this was not the case for [18F]2a. This is likely because regioselectivity of ring opening under acidic conditions involved neighbouring group participation of the conjugated alkene.40

Figure 4:

The opening of sterically hindered epoxides by radiofluorination with [18F]FeF species produced from [18F]HF. General conditions: a) Cyclotron produced fluorine-18 (approx. 66.6 Gbq, 1.8 Ci), elution solution = TFA in MeCN/H2O 4:1 (0.5M, 0.5 mL), substrate (0.04 mmol), Fe(acac)3 (0.08 mmol) in dioxane (0.5 mL) stirred at 120 °C for 20 min; RCP = radiochemical purity.

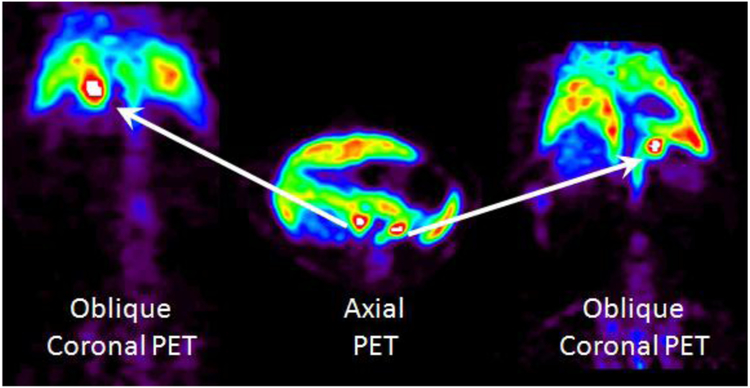

Finally, we conducted a preliminary evaluation of [18F]1a as an adrenal imaging agent.# Following synthesis, the purification of [18F]1a was carried out by HPLC with an EtOH:H2O eluent that was subsequently diluted into saline that contained Tween® 80 (polysorbate) at the concentrations previously utilized for [131I]NP-59 and related cholesterol imaging agents (1.6% Tween® 80 and 6.6% ethanol).41 Biodistribution studies were conducted in female Sprague-Dawley rats (see Supporting Information), confirming both very high adrenal uptake compared to most other organs and good signal to noise (adrenal to liver ratio = 3.3).

The high signal in the adrenal glands led us to investigate the radiotracer further via small animal PET imaging (Figure 5). A female Sprague-Dawley rat was injected with [18F]1a i.v. and imaged for 120 min. Both adrenal glands can be seen in the axial plane, and the corresponding oblique coronal plane for each adrenal gland is also shown. It is clear that adrenal gland uptake is high compared to background uptake by other organs. Imaging the utilization of cholesterol in the body with [18F]1a therefore merits further study as part of our ongoing adrenal/endocrine imaging efforts.

Figure 5:

Small animal PET imaging of a female Sprague-Dawley rat, summed frames 0-120 minutes, with an axial view showing both adrenal glands (arrows) and oblique views where one adrenal gland is in plane.

In summary, a simple method for the preparation of [18F]HF has been developed and applied to the generation of an [18F]FeF species for the opening of sterically hindered epoxides. This method has been automated and successfully applied to four drug-like molecules including a potential adrenal/endocrine PET imaging agent ([18F]1a). Pre-clinical evaluation of [18F]1a revealed good adrenal uptake and retention in rodent, and demonstrates the potential for advances in radiochemistry to rapidly impact new radiotracer development. In addition, access to [18F]HF will allow for the simple preparation of other metal fluorides using related procedures for the future development of additional fluorine-18 methodologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01EB021155 from NIBIB (Scott and Sanford) and funding from the Center for the Discovery of New Medicine at the University of Michigan and a Mi-Kickstart Award from MTRAC for Life Sciences Innovation Hub (Viglianti and Brooks).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details and characterization of reactions, and procedures for animal experiments. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Radio-TLC was attempted initially but did not give consistent results, even when the same sample was spotted on different plates.

RCY are non-isolated and were calculated by % integrated area of the 18F product versus 18F- in a radio-HPLC trace.

Starting [18F]F- activity for full scale radiosyntheses is not measured for every run due to restrictions of the lab setup and radiation safety concerns, but is rather estimated using our established 18F-production curve (see Supporting Information).

All animal PET imaging experiments were conducted under the supervision of the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

References

- 1.For comprehensive reviews of traditional fluorine-18 radiochemsitry, see:Cai L, Lu S and Pike VW, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2008, 2853–2873;Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R and Gee AD, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed, 2008, 47, 8998–9033;Jacobson O, Kiesewetter DO and Chen X, Bioconjugate Chem, 2015, 26, 1–18.

- 2.For recent reviews of new late-stage fluorination methods, see:Brooks AF, Topczewski JJ, Ichiishi N, Sanford MS and Scott PJH, Chem. Sci, 2014, 5, 4545–4553;Campbell MG and Ritter T, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 612–633;Preshlock S, Tredwell M and Gouverneur V, Chem. Rev, 2016, 116, 719–66;Deng X, Rong J, Wang L, Vasdev N, Zhang L, Josephson L and Liang SH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 2580–2605.

- 3.Scholz G and Kemnitz E, eds. Groult H, Leroux FR and A. B. T.-M. S. P. and R. of F. C. Tressaud, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 609–649. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blessing G, Coenen HH, Franken K and Qaim SM, Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrumentation. Part A. Appl. Radiat. Isot, 1986, 37, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelini G, Speranza M, Shiue C-Y and Wolf AP, J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun, 1986, 924–925. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelini G, Speranza M, Wolf AP and Shiue CY, Radiochim. Acta, 1990, 50, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angelini G, Speranza M, Wolf AP and Shiue C-Y, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 1990, 28, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathiessen B, Jensen ATI and Zhuravlev F, Chem. – A Eur. J, 2011, 17, 7796–7805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathiessen B, Jensen M and Zhuravlev F, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2011, 54, 816–818. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revunov E and Zhuravlev F, J. Fluor. Chem, 2013, 156, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA and Liu H, Chem. Rev, 2014, 114, 2432–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharts CM and Sheppard WA, Org. React, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahak I, Manor S and Bergmann ED, Organic fluorine compounds. Part XLI. The reaction of hydrofluoric acid with cycloalkene epoxides, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham TJA, Lambert RF, Ploessl K, Kung HF and Doyle AG, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 5291–5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podichetty AK, Wagner S, Schroer S, Faust A, Schaf̈ers M, Schober O, Kopka K and Haufe G, J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 3484–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schirrmacher R, Lucas P, Schirrmacher E, Wan̈gler B and Wan̈gler C, Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1973–1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turkman N, Gelovani JG and Alauddin MM, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2010, 53, 782–786. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kil HS, Cho HY, Lee SJ, Oh SJ and Chi DY, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2013, 56, 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiesewetter DO, Kilbourn MR, Landvatter SW, Heiman DF, Katzenellenbogen JA and Welch MJ, J. Nucl. Med, 1984, 25, 1212–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knott KE, Grätz D, Hübner S, Jüttler S, Zankl C and Müller M, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2011, 54, 749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao J, Liu Y, Zhang L, Du F, Ci Y, Zhang Y, Xiao H, Yao X, Shi S, Zhu L, Kung HF and Qiao J, J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem, 2017, 312, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amaraesekera B, Marchis PD, Bobinski KP, Radu CG, Czernin J, Barrio JR and Michael van Dam R, Appl. Radiat. Isot, 2013, 78, 88–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackermann U, Lewis JS, Young K, Morris MJ, Weickhardt A, Davis ID and Scott AM, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2016, 59, 424–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou D, Lin M, Yasui N, Al-Qahtani MH, Dence CS, Schwarz S and Katzenellenbogen JA, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 2014, 57, 371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mossine AV, Brooks AF, Ichiishi N, Makaravage KJ, Sanford MS and Scott PJH, Sci. Rep, 2017, 7, 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross MD, Shapiro B, Bouffard JA, Glazer GM, Francis IR, Wilton GP, Khafagi F and Sonda LP, Ann. Intern. Med, 1988, 109, 613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross MD, Shapiro B, Francis IR, Bree RL, Korobkin M, McLeod MK, Thompson NW and Sanfield JA, Eur. J. Nucl. Med, 1995, 22, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar SD, Beierwaltes WH, Ice RD, Basmadjian GP, Hetzel KR, Kennedy WP and Mason MM, J. Nucl. Med, 1975, 16, 1038–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross MD, Grekin RJ, Brown LE, Marsh DD and Beierwaltes WH, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 1981, 52, 612–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wale DJ, Wong KK, Viglianti BL, Rubello D and Gross MD, Biomed. Pharmacother, 2017, 87, 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Counsell RE, Ranade VV, Blair RJ, Beierwaltes WH and Weinhold PA, Steroids, 1970, 16, 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucsi I, Török B, Marco AI, Rasul G, Prakash GKS and Olah GA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2002, 124, 7728–7736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olah GA, Welch JT, Vankar YD, Nojima M, Kerekes I and Olah JA, J. Org. Chem, 1979, 44, 3872–3881. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olah GA and Meidar D, Isr. J. Chem, 1978, 17, 148–149. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okoromoba OE, Han J, Hammond GB and Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 14381–14384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Z, Zeng X, Hammond GB and Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 18202–18205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhone-Poulenc Chemicals Ltd., Preparation of fluoro-compounds, WO1994/026756 A1, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ory D, Van den Brande J, de Groot T, Serdons K, Bex M, Declercq L, Cleeren F, Ooms M, Van Laere K, Verbruggen A and Bormans G, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal, 2015, 111, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.19F-1a is known, while [18F]1a and 18F/19F2a-4a are novel compounds. See:Henbest HB and Wrigley TI, J. Chem. Soc, 1957, 5765–4768;Boswell G Jr. J. Org. Chem, 1968, 33, 3699–3713;Bourgery G, Frankel JJ, Julia S and Ryan RJ, Tetrahedron, 1972, 28, 1377–1390;Trka A and Kasal A, Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1982, 47, 2946–2960.

- 40.Uebelhart P, Baumler A, Haag A, Prewo R, Bieri JH, Eugster CH. Helv. Chim. Acta 1986, 69, 816–834. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beierwaltes WH, Wieland DM, Yu T, Swanson DP and Mosley ST, Semin. Nucl. Med, 1978, 8, 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.