Abstract

Background

In problem gambling, recent years have seen an expansion of online gambling in treatment-seeking patients. Television advertising may promote risky gambling, and this study aimed to assess gambling-related advertisements, with respect to potentially risky messages, in a country with high rates of online gambling among treatment seekers, for online casino particularly in treatment-seeking women.

Methods

A total of 144 h in six commercial television channels were studied with respect to frequency, extent and content of gambling-related advertisements, which were analyzed with respect to potentially risky messages and specific target groups, and compared with respect to legal status of gambling companies and for online casino gambling vs other gambling types. Aspects to analyze were elected theoretically and based on acceptable inter-rater agreement between the authors.

Results

Nineteen percent (11–28% across different channels) of advertisements promoted gambling, with online casino being by far the most common type of gambling exposed. Messages promoting ease to gamble (including bonuses and rapid cash-out messages) and a female focus were significantly more common in online casino gambling and in non-licensed companies, whereas sports-related messages were more common in licensed companies. Gambling-related advertisements were also common in relation to family movies, and appeared even during children's programs.

Conclusions

Online casino was by far the most common type of televised gambling advertisements. Several risky messages were identified, and female gender, as well as messages promoting the rapidity and facility of gambling, were more commonly addressed by online casino companies. Public health aspects are discussed.

Highlights

-

•

Gambling advertisements are common in television in a country where online games are predominating in treatment settings.

-

•

Several potentially hazardous gambling messages are common, and more common in online casino-related advertisements.

-

•

Online casino-related advertisements more commonly addressed women, with potential implications for the health of female gamblers.

-

•

Findings call for increased attention to gambling advertisements as a public health issue.

1. Background

Gambling disorder is an addictive disorder believed to occur in around 0.5% of the adult population (Kessler et al., 2008; Petry, Stinson, & Grant, 2005), and the broader concept of problem gambling has been stated to range between 0.1 and 5.8% of the population across setting and studies (Calado & Griffiths, 2016). Disordered gambling is known to be associated with a high degree of psychiatric comorbidity (Dowling et al., 2015). With the inclusion of gambling disorder in the chapter of addictive disorders in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), gambling has become more clearly established as a potential health issue in parallel with alcohol and drug use disorders, and gambling has increasingly attracted attention as a potential public health issue with needs for preventive measures. Gambling advertisements are commonly seen by the population (Pitt, Thomas, Bestman, Stoneham, & Daube, 2016), and may send a message of normalization with respect to gambling. It has been argued that – for example – the exposure of sports wagering advertisements may normalize gambling in a sports context (Deans, Thomas, Derevensky, & Daube, 2017).

The increase in online gambling in recent years may present new challenges in the prevention of problem gambling. Online gambling represents an increasing proportion of gambling, and, although differing between countries, online problem gambling can represent a major proportion of treatment-seeking gambling disorder patients, such as in Sweden (Håkansson, Mårdhed, & Zaar, 2017). Sweden has seen an increase in online gambling in recent years, with a gambling market that has been divided between a legal proportion of governmental and other licensed gambling operators, and non-licensed companies operating from other countries, the latter providing mainly online gambling, particularly online gambling and online betting (Swedish government, 2017).

Intuitively, the content and extent of gambling-related commercial advertising may influence gambling behaviors and the risk for gambling-related problems. Also, negative influence from being exposed to gambling advertisements has been reported to be more pronounced in problem gamblers than in other gamblers, and in online gamblers, compared to those gambling in other modalities (Binde & Romild, 2018).

The scientific literature describing the content of gambling advertising has been limited. Deans, Thomas, Daube, Derevensky, and Gordon (2016) analyzed the content of 85 sports advertisements, and identified a number of symbolic features appearing in these advertisements, including both visual, written and verbal messages.

Based on the characteristics of a disordered pattern of gambling, including the loss of control, financial difficulties, and the ‘chasing losses’ behavior (Petry et al., 2005; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), several specific components in gambling advertising may be seen as potentially risky, such as the message that gambling is free or can be carried out without access to money, such as through bonuses (Hing et al., 2018; Hing, Vitartas, & Lamont, 2017), or where rapid cash-out messages give an impression that wins can be rapidly obtained (Hing, Russell, Thomas, & Jenkinson, 2019). In addition, advertising may address specific risk groups; on one hand, a majority of problem gamblers are men, particularly younger men, and on the other hand, women with a gambling disorder are known to have a higher prevalence of psychological distress (Grant, Odlaug, & Mooney, 2012; Håkansson et al., 2017), making women a vulnerable group with respect to gambling.

The aim of the present study was to describe the extent and content of gambling in television advertising, and to analyze the content of gambling advertising in relation to different types of television programs, time of day and the legal status of the television channel, as well as a number of potentially public health-related components of gambling advertisements, such as those promoting the rapidity/ease of gambling, messages allowing gambling without money, or which include celebrities or messages targeting specific gender groups.

2. Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional analysis of the frequency, extent and content of gambling advertisements during one 24-h period of each of the leading six television channels in Sweden.

2.1. Setting

In Sweden, at the time of the study, the gambling market was characterized by an oligopoly situation, with one governmental company with monopoly in several types of gambling, and a number of private companies (mainly in horse racing and lotteries) with legal Swedish licenses for gambling. However, despite the theoretical regulated oligopoly situation, a large share of the actual gambling market was represented by non-licensed online gambling operators operating from other countries, mainly in online sports betting and online casino. At the time of the present study, online casino was not a legal type of gambling in Sweden, and consequently, advertising promoting this type of gambling also was not allowed, although with unclear judicial aspects as several television operators (although completely perceived as Swedish and targeting only the Swedish population) were not Sweden-based, such that the prohibition largely has been without practical consequence to the commercial gambling market (Binde & Romild, 2018; Swedish government, 2017). Likewise, commercial advertising promoting land-based electronic gaming machines and land-based casino are not legal. The legal gambling age in Sweden is 18.

Sweden (with a full population of 10 million inhabitants) has one state-owned non-commercial public service television company without commercial advertising (except for brief messages about sponsors of major sports events and similar). This public service company provides two channels daily reaching 3.5 and 1.8 million viewers, respectively. In addition, a large number of available commercial television channels broadcast either from Sweden or from abroad, with different legal status in the country. TV4 (3.2 million viewers daily) is land-based, with ownership in Sweden and regulated by Swedish legislation, and contents of advertisements are theoretically obliged to respect Swedish legislation, where only legal gambling types can be advertised. TV3 and Kanal 5 (‘Channel 5’) are entirely commercial television channels (0.9 and 1.2 million viewers, respectively) based in the United Kingdom for the Swedish market, and TV6 and Kanal 9 (‘Channel 9’, 0.7 and 0.5 million viewers, respectively) are associated with TV3 and Channel 5, respectively, and with the same legal status. Sjuan (‘Seven’, 0.9 million viewers) is the smaller channel associated with TV4, and likewise land-based and with the same legal status. An additional channel owned by TV4, TV12, is smaller than ‘Seven’ (0.6 million viewers) and was not chosen for the present study. Likewise, within the same domain as TV3 and TV6, TV8 is an additional ‘sister channel’ of TV3, with approximately the same number of viewers as TV6 (rounded off to 0.6 million, MMS, Mediamätning i Skandinavien, 2017), and was also not included in the study.

2.2. Procedures

All 144 h of television were analyzed by the first author. Initially, it was decided to study the three major commercial television channels in Sweden, TV3, TV4 and Channel 5, which were recorded on consecutive dates in December 2017. Thereafter, in order to increase the total amount of data, it was decided to include also the two smaller ‘sister channels’ of the two channels with the highest commercial involvement, and which were recorded in January 2018, and thereafter, for the sake of completeness, the ‘sister channel’ of TV4 (‘Seven’) was also included in the study. Both descriptive and comparative analyses were carried out only after the full completion of all channels. Dates chosen for recording were selected with few specific guidelines, but avoiding weekends and avoiding major sports events and the type of once-only major TV events typically happening on weekends.

Data were registered describing all advertisements (gambling and non-gambling advertisements) appearing in commercial breaks, including the name of the company behind the advertisement and the type of product promoted. The full amount of broadcasting was recorded and reviewed, the timing of each full commercial break was recorded in minutes and seconds, and duration of each gambling-related advertisement was recorded in seconds. Also, brief messages used to ‘present’ a TV show (‘this show was presented by…’) were recorded and analyzed for content, although not recorded with respect to their duration. Every version of a gambling-related advertisement was reviewed independently, such that if messages promoting one gambling product with separate slightly different advertisements, these were analyzed independently. The review of each commercial break was carried out thoroughly, typically viewing and re-viewing until the exact content of the commercial break was correctly noted and coded. This study procedure was carried out by the first author.

After the full review procedure carried out by the first author, a selection of 34 gambling advertisements were chosen for a review by the second author, in order to address inter-rater agreement. The second author was not involved in the selection of these advertisements, and no communication took place about the results of the first author's review. The 34 different advertisements were selected from a total of 67 separate advertisements identified (some of these distinct from each other but with some similarities, and some representing the same gambling operator but with different profiles of the advertisement), and the selection was made with the aim to include a broad spectrum of different gambling types and companies with different legal status. These 34 advertisements included, for example, both those related to online casino, sports, lotteries, and a national television bingo show, those representing licensed and non-licensed companies, and both longer advertisements and those being displayed as a company ‘presenting’ the ongoing TV show.

2.3. Measures

For each advertisement, data was registered describing the type of television program during or after which the advertising appeared, the time of day (2 am–6 am, 6 am–10 am, 10 am-2 pm, 2 pm–6 pm, 6 pm–10 pm, and 10 pm-2 am), the duration of the advertisement, whether or not it involved gambling, and if so, the type of gambling and a number of specific aspects of the gambling content. As many advertisements measured just below each 5-s interval, times were post hoc approximated to these 5-s intervals, such that a commercial slot measuring between 14 and 15 s was rounded off to 15 s.

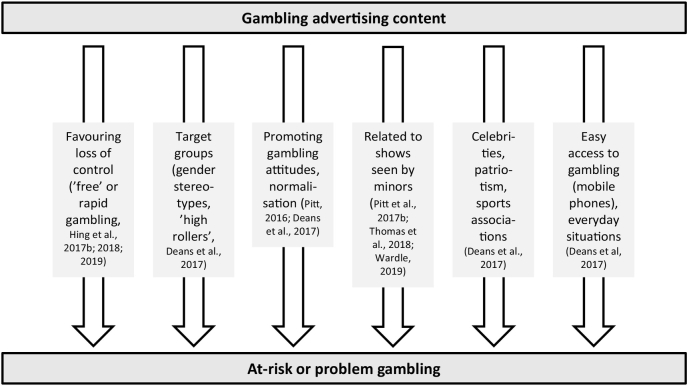

The content analyzed in the present study included marketing contents of relevance documented in previous literature, in a recent governmental policy document, or considered relevant by the authors of the study (Fig. 1). This includes commercial messages examined by Deans et al. (2016) or themes identified in that paper, where all components analyzed were related to sports wagering primarily. This paper inspired the choice of variables describing a focus on winning and how winning may change life, a focus on different experience of gambling (joy/excitement, ‘fun to gamble’, and adventurousness/risk taking), a primarily focus on male stereotypes and males gambling (and consequently, in the present paper, also the opposite, a focus on women's gambling), the social status of gamblers, the feeling of wealth and control in gamblers, prominent people involved in advertisements, the message of luxurious settings related to gambling, peer bonding, patriotism and supporter rituals related to sports, high odds in sports, and the use of mobile telephones in order to facilitate gambling ‘anywhere’, anytime’. Several additional items were derived from advertisement components addressed in a recent proposal for a new gambling legislation in Sweden (Swedish government, 2017), which addressed a number of topics related to gambling advertising; messages about bonuses or gambling perceived as ‘free’ (and consequently, in the present study also the existence of ‘free’-spins' or gifts to the gambler), rapid cash-out and the discussion around the importance of proper registration of gamblers (leading to a focus in the present paper of both the ease/rapidity of registering and cash-out). In addition, inspired by the topics discussed above, in the present study topics addressed also included the use of everyday situations and a more folklore-inspired environment (as a contrast to luxurious situations mentioned above), and based on the social status topic we also included an item describing whether an advertisement targeted particularly big gamblers (‘high rollers'). In addition, based on an impression of a new type of advertising for internet sites providing comparisons of gambling services, this was also included, as well as a focus on whether gambling responsibility is highlighted in the advertisement. Finally, as the present study addressed all kinds of gambling, one variable described whether the advertisement had a sports or horse focus or not. All studied aspects of gambling advertisements are displayed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoreticalmodeldescribingthe rationalefor the studyofgambling advertising, includingcomponentspotentiallyenhancinggambling or riskygambling behaviour.

Table 1.

Components analyzed in gambling-related advertisements.

| Focus on wins (easy to win, the change of life through wins) |

| Focus specifically on jackpots/large wins |

| The experience, joy and excitement in gambling |

| Eternal happiness related to gambling wins |

| A celebrity included in the advertisement |

| Responsible gambling message appearing |

| Advertisement promoting a service which compares different gambling services |

| Focus on bonuses |

| Focus on free-spins |

| The word ‘free’ is included |

| Gifts to gamblers |

| Faster/easier cash-out |

| Faster/easier registration at the gambling site |

| High odds |

| Focus on big gamblers (‘high rollers’) |

| Focuses on one or several women who gamble (men may be gambling but the advertisement focuses on women). Does not exclude number 17. |

| Focuses on one or several men who gamble (women may be gambling but the advertisement focuses on men). Does not exclude number 16. |

| Promotes male stereotypes |

| Focuses on sports (including horse races) |

| Social status in gamblers |

| ’Peer bonding’, friends come together related to gambling |

| Focuses on mobile telephones |

| Everyday situations |

| Luxurious situations |

| Wealth, power, and control |

| Rituals of sports supporters, loyalty to the sports team |

| Patriotism |

| Excitement, adventure, and risk taking |

| Focus on gambling as fun |

| Folklore feeling |

Inter-rater agreement was measured using kappa statistics, and variables with a kappa value below 0.60 were dropped from further analysis. For 19 variables, the kappa value was above 0.6 (ranging from 0.63 to 1.0), whereas for nine variables (excitement/joy of gambling, eternal happiness related to gambling, explicit responsible gambling communications, the mention of mobile telephones, the association to everyday situations, a message of wealth and control, patriotism, excitement/risk taking, and the joy of gambling), Kappa values ranged from 0.18 to 0.53, such that these variables were excluded from further analysis. The message of rapid registration for gambling was not observed in any of the 34 advertisements tested for inter-rater agreement, and therefore, this variables also was not further included.

The specific full content of the 24-h period of each channel is displayed in the supplementary file. Among the 5810 commercial advertising clots included, 28% (n = 1619) appeared in relation to (during or after) reality shows, 18% (n = 1063) in relation to movies primarily aimed for adults, and 14% (n = 786) in relation to comedies/situation comedies. Other common TV show categories were family movies and shows characterized as criminal/science-fiction, soap opera or action series (11% of advertisements, n = 639 and n = 650, respectively), and children's programs (8%, n = 452), news (including sports/weather and morning news magazine, 3%, n = 188), entertainment (3%, n = 200), cooking shows (2%, n = 140), and advertisements appearing in relation to gambling shows (lottery shows, horse racing shows, 1%, n = 75). An additional four advertisements were unrelated to a specific TV show (n = 3), or represented one 2-h advertising show promoting one single company's household products (n = 1).

2.4. Statistical analyses

In addition to descriptive analyses of the extent and content of gambling advertisements, comparisons were made between gambling advertisements from licensed and non-licensed gambling operators. Also, as online casino represented the most common gambling type promoted, comparisons were made between online casino advertisements and other gambling advertisements. These statistical comparisons were made using chi-squared tests, and Fisher's exact test for low numbers (less than five in any of the groups in the cross-tabulation).

3. Results

3.1. Extent of gambling advertising in different channels and types of TV shows

Among a total of 5810 advertisements, among which 891 (15%) promoted gambling, representing 67 separate advertisements, each with a separate content analyzed as described below. The proportions of each category of advertisement, are displayed in Table 2, and the extent of gambling advertisements in each channel is displayed in Table 3. The proportion of gambling-related advertisements ranged between eight and 11% in the two land-based Swedish channels, to 20 and 23% in TV3 and Channel 5, respectively. When excluding advertisements for TV channels and TV program information (where typically the TV channel's own shows were promoted), the proportion of gambling advertisements was 19%, ranging from 11 and 12% in the two land-based channels, 17% in Channel 9, to 24, 28 and 22% in TV3, Channel 5, and TV6, respectively.

Table 2.

Content of advertisements, total (N = 5810).

| TV3 | TV4 | Channel 5 | TV6 | ‘Seven’ | Channel 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 28–29 (Tuesday-Wednesday), 2017, 5.30 pm–5.30 pm | December 30–31 (Thursday-Friday), 2017, 6 pm–6 pm | December 29–30, 2017 (Wednesday-Thursday), 6 pm–6 pm | January 8–9 (Monday-Tuesday), 2018, 6 pm–6 pm | February 6–7 (Tuesday-Wednesday), 2018, 6 pm–6 pm | January 10–11 (Wednesday-Thursday), 2018, 6 pm–6 pm | |

| Audience of the channel (MMS; 2017); proportion reached daily in different groups | Men: 8% Women: 11% 15–24 yrs.: 4% 60 + years: 14% |

Men: 30% Women: 37% 15–24 yrs.: 11% 60 + years: 60% |

Men: 12% Women: 13% 15–24 yrs.: 5% 60 + years: 17% |

Men: 8% Women: 5% 15–24 yrs.: 3% 60 + years: 8% |

Men: 7% Women: 12% 15–24 yrs.: 2% 60 + years: 18% |

Men: 6% Women: 5% 15–24 yrs.: 2% 60 + years: 8% |

| Gambling | 20% (193) | 11% (106) | 23% (224) | 17% (167) | 8% (80) | 14% (121) |

| Loans or other financial services | 4% (42) | 7% (66) | 3% (33) | 8% (83) | 3% (27) | 3% (30) |

| TV programs or services | 17% (164) | 14% (142) | 19% (180) | 26% (256) | 24% (227) | 21% (188) |

| Alcohol, Swedish monopoly information | 1% (10) | 2% (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alcohol, commercial | 0 | 0% (3) | 0 | 1% (7) | 0 | 1% (6) |

| Other products or services | 58% (570) | 67% (671) | 55% (532) | 49% (488) | 74% (710) | 61% (545) |

| Total | 100% (979) | 100% (1007) | 100% (969) | 100% (1001) | 100% (964) | 100% (890) |

Table 3.

Gambling advertising content per channel.

| TV3 | TV4 | Channel 5 | TV6 | ‘Seven’ | Channel 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gambling, total time in seconds (minutes) for each 24-h period, (% of total time, excluding program presentation messages) | 2930 (48.8) | 1117a (18.6) | 3205 (53.4) | 2055 (34.3) | 1455 (24.3) | 2425 (40.4) |

| Gambling, number of advertisements (% of total) | 140/805 = 17% | 55/820 = 7% | 151/825 = 18% | 94/857 = 11% | 80/948 = 8% | 113/826 = 14% |

| Gambling, number of program presentations (% of total) | 53/174 = 30% | 51/187 = 27% | 73/143 = 51% | 73/144 = 51% | 0/16 = 0% | 8/64 = 13% |

| Proportion of advertisements from non-registered gambling companies (% of gambling advertisements, % of all advertisements,) | 186/193 = 96% (19%) | 47/106 = 44% (5%) | 219/224 = 98% (23%) | 156/167 = 93% (16%) | 0/80 = 0% (0%) | 13/121 = 93% (13%) |

Excluding 300 s of a separate lottery show.

During each part of the day, 2 am–6 am, 6 am–10 am, 10 am-2 pm, 2 pm–6 pm, 6 pm–10 pm, and 10 pm-2 am, gambling represented 11, 9, 14, 16, 17 and 21% of commercial advertising slots, respectively; thus, the highest proportion was during afternoons and evenings. The proportion of gambling advertisements were the highest during or after movies primarily aimed for adults (26%, n = 272), TV shows focusing on either horse racing, lottery drawings or similar (25%), family movies (20%, n = 125), entertainment (18%, n = 35), comedy series (16%, n = 129), and reality shows (13%, n = 209), but gambling advertisements were also available to some extent during and after children movies (6% of advertisements, n = 25), cooking programs (6%, n = 8) and news (7%, n = 14).

3.2. Types of gambling promoted

A majority of gambling advertisements represented non-licensed gambling operators (81%, n = 721). The proportions of separate gambling types are displayed in Table 4. Among gambling advertisements, the most common type of gambling was online casino. While online casino (only or, in a smaller proportion combined with sports betting) was non-existent in one of the land-based channels and represented 44% of commercial advertising slots in the other (representing only program presentations), its proportion reached 74 and 83%, respectively, in two of the foreign-based channels. In total, online casino represented 64% of gambling advertisements, compared to a total of 20% for sports games, 9% for lotteries, 6% for bingo, and 5% for horse games. The proportion of gambling advertisements representing online casino gambling was 94% (n = 33) for advertisements appearing during or after entertainment programs, 80% (n = 20) for children's movies, 76% for family movies (n = 95), 73% for movies aimed for adults (n = 199), 66% (n = 86) for comedy series, and 41% (n = 23) for criminal and/or sci-fi series.

Table 4.

Types of gambling promoted in gambling-related advertisements (N = 891), % (n).

| TV3 | TV4 | Channel 5 | TV6 | ‘Seven’ | Channel 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online casino | 68% (131) | 41% (43) | 72% (161) | 60% (101) | 0 | 51% (62) |

| Online sports betting | 10% (20) | 0 | 13% (28) | 13% (22) | 0 | 13% (16) |

| Online casino and sports betting combined | 6% (11) | 4% (4) | 11% (24) | 11% (18) | 0 | 9% (11) |

| Online bingo | 3% (5) | 26% (28) | 1% (3) | 4% (6) | 0 | 9% (11) |

| Lottery | 2% (3) | 0 | 0 | 5% (9) | 29% (23) | 7% (8) |

| Online poker | 8% (16) | 0 | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 4% (5) |

| Regular and traditional weekend-based soccer gambling (‘Stryktipset’) | 1% (2) | 8% (9) | 0% (1) | 0 | 0 | 4% (5) |

| Horse races | 2% (4) | 10% (10) | 0 | 4% (7) | 34% (27) | 0 |

| ‘Postkodlotteriet’, national lottery | 0 | 7% (7) | 0 | 0 | 16% (13) | 0 |

| Monopoly-based lottery (‘Triss’) | 0 | 1% (1) | 0 | 0 | 11% (9) | 0 |

| Monopoly-based sports betting (‘Oddset’) | 1% (1) | 2% (2) | 2% (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monopoly-based eurojackpot | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2% (3) | 0 | 2% (3) |

| Monopoly-based, other | 0 | 2% (2) | 0 | 0 | 10% (8) | 1% (10) |

| Association to gambling advertisementsa | 0 | 0 | 1% (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100% (193) | 100% (106) | 100% (224) | 100% (167) | 100% (80) | 100% (121) |

Advertisement not directly promoting gambling, but with clear references to other operator-specific gambling advertisement.

3.3. Advertising of licensed vs non-licensed gambling and online casino vs other gambling

The present comparisons are displayed in Table 5, Table 6. Several differences were seen between messages from licensed and non-licensed gambling operators. Several different messages promoting ease to gamble (including bonuses, free-spins, rapid cash-out messages, and the use of the word ‘free’) were significantly more common in advertisements from non-registered companies, as were message focusing on big gamblers, or specifically on gambling women or gambling men, respectively. Likewise, in online casino gambling messages, compared to other types of gambling, messages about bonuses, free-spins, rapid cash-out and messages appealing to big gamblers were significantly more common, in contrast to the use of word ‘free’, which was more common in other gambling types. Online casino gambling was significantly associated with a focus on female gambling, whereas no significant difference was seen with respect to male gambling.

Table 5.

Components of gambling advertisements from licensed vs non-licensed gambling operators. Chi-squared test (Fisher's exact test for absolute numbers <5).

| Advertisements from licensed gambling operators (n = 170), % | Advertisements from non-licensed gambling operators (n = 721), % | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus on wins | 68 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Focus on jackpot wins | 56 | 22 | <0.001 |

| Luxury setting | 16 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Prominent person included | 21 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Message about bonuses | 0 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Message about free-spins | 0 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Message about rapid cash-out | 0 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Message involving the word ‘free’ | 0 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Peer bonding | 3 | 9 | <0.01 |

| High odds | 0 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Appeal to big gamblers | 0 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Social status of gamblers | 0 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Focus on female gamblers | 0 | 12 | <0.001 |

| Focus on male gamblers | 5 | 27 | <0.001 |

| Folklore associations | 0 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Sports supporter rituals / team loyalty | 7 | 15 | <0.01 |

| Sports and/or horse focus | 26 | 20 | 0.12 |

Table 6.

Components of gambling advertisements promoting online casino vs advertisements promoting other types of gambling. Chi-squared test (Fisher's exact test for absolute numbers <5).

| Advertisements promoting online casino (n = 566), % | Advertisements not promoting online casino (n = 325), % | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus on wins | 30 | 36 | <0.05 |

| Focus on jackpot wins | 24 | 37 | <0.001 |

| Luxury setting | 10 | 9 | 0.43 |

| Prominent person included | 12 | 8 | 0.10 |

| Message about bonuses | 30 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Message about free-spins | 11 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Message about rapid cash-out | 13 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Message involving the word ‘free’ | 2 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Peer bonding | 4 | 14 | <0.001 |

| High odds | 0 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Appeal to big gamblers | 10 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Social status of gamblers | 13 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Focus on female gamblers | 16 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Focus on male gamblers | 20 | 28 | <0.01 |

| Folklore associations | 7 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Sports supporter rituals / team loyalty | 4 | 30 | <0.001 |

| Sports and/or horse focus | 11 | 40 | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

The present study provides a detailed description of gambling advertising in Swedish television, including the gambling-related content in advertisements in commercial television channels, in a setting with a gambling market divided between licensed and non-licensed companies, and with a large predominance of online gambling in patients seeking treatment for gambling disorder (Håkansson et al., 2017; Swedish government, 2017). The study demonstrates a large component of gambling in television advertisements, but also a large predominance for online casino gambling within gambling-related advertisements. For several messages assumed to promote risky gambling behaviour, such as messages about the rapidity and ease of gambling, giving an impression of gambling as being either free or possible to carry out without money or with monetary bonuses, these messages were more common in non-licensed companies and more common in online casino. In particular, the specific targeting of women was more common in online casino gambling, and differed from the targeting of males, whereas this focus on female gambling was rare in registered companies, where sports-related content was more common.

In the present study, online casino was by far the most frequent type of gambling appearing in gambling-related advertisements, and a common content in advertisements overall, even though online casino at the time was not an approved form of gambling in Sweden, represented solely by companies unauthorized in Sweden and operating from abroad. Also, in several aspects, advertisements promoting online gambling were more likely than other gambling advertisements to promote potentially risky gambling measures, such as those describing an ease to gamble, even with ‘free’ gambling tools such as bonuses or free-spins, or rapid cash-out messages. This finding can be seen in light of findings describing that online casino represents a majority of treatment-seeking patients with gambling disorder in Sweden (Håkansson et al., 2017), and a large and increasing percentage of callers to a national helpline for problem gambling (Swedish Government, 2017). The connection of online casino to messages promoting rapidness of gambling, and messages promoting the ease to gamble even without access to money, are intuitively perceived as particularly hazardous with respect to the loss of control in problem gambling. In addition, online casino advertisements were more likely to be presented as related to people who gamble more than others, ‘high rollers’, i.e. theoretically further increasing the risk profile of these messages. It is known that detailed content of gambling commercials can influence gamblers' attraction to bonus offers (Hing et al., 2018), and the perception of gambling as free of risk has been described to be attractive to viewers (Hing, Vitartas, & Lamont, 2017). Rapid cash-out messages potentially also could have a particular influence on gamblers having lost control of gambling (Hing et al., 2019), including gamblers in severe financial difficulties. In light of the high percentage of online casino gamblers among those seeking treatment (Håkansson et al., 2017; Swedish Government, 2017), the present findings can be seen as worrying.

In the present study, online casino commercials more commonly involved components targeting women, and less commonly targeting men. A clear message of gambling women was even rare in other gambling types than online casino. While this is partly due to the higher male involvement in commercials for sports-related gambling, the link between online casino and female gender also is seen in the present setting in treatment-seeking gamblers (Håkansson et al., 2017), whereas sports-related gambling is more common in men than in women (Grant & Kim, 2002; Ladd & Petry, 2002; Toneatto & Wang, 2009). Theoretically, if online casino is more common in women with gambling disorder who seek treatment, and if online casino is also more commonly appearing in gambling advertisements perceived as targeting women, this could theoretically provide an increased risk of women with respect to this particular type of gambling, and may require particular attention in public health work in the area. Here, more research is needed in order to highlight whether online casino advertisements may actually attract female viewers to a larger extent. Also, the addressing of women in online casino advertisements may be seen as particularly problematic, given the higher degree of psychiatric comorbidity in female patients with gambling disorder, compared to their male counterparts (Diez, Aragay, Soms, Prat, & Casas, 2014; Grant et al., 2012; Håkansson et al., 2017). Clearly, more research is needed in order to highlight whether there are associations between gambling advertisements targeting women and problem gambling in women, but the psychological vulnerability described in women seeking gambling disorder treatment may call for increased attention to way gambling is advertised in relation to the female population.

Although less common than online casinos in the advertisements studied here, sports-related gambling messages were relatively common in the present study. Sports gambling marketing may normalize sports betting (Deans et al., 2017), and sports bettors are likely to respond to sports betting marketing embedded within sports broadcasting (Hing, Russell, Lamont, & Vitartas, 2017). This may present a particular challenge with respect to the risk of problem gambling in individuals with an extensive involvement in sports. Previous research has demonstrated that problem gambling is more common in high-level athletes, particularly in men (Håkansson et al., 2018).

In the present study, although less common than in television shows primarily aimed for adults, even television shows addressing children were associated with gambling advertisements, and these were even common in movies perceived as family movies. Despite the illegal status of gambling in minors, television advertising in this area is likely to reach far beyond the adult population. It previously has been reported that a large majority of children (and adults) report having seen a sports wagering advertisement (Pitt et al., 2016), and even relatively young children recall detailed information about gambling practices from TV commercials (Pitt, Thomas, Bestman, Daube, & Derevensky, 2017b). Large proportions of children and young adolescents recall gambling operators from their appearance in gambling advertising (Thomas et al., 2018). Also, in qualitative interviews, it has been reported that children are able to report interpretations of specific promotions about cash-backs or other features which make gambling seem ‘free’ and harmless (Pitt et al., 2017b). Gambling advertising may normalize gambling as viewed by children (Wardle, 2019), and the role of advertising as appealing to gambling interest and intentions in young people has been reported (Pitt, Thomas, Bestman, Daube, & Derevensky, 2017a). As young people have been reported to be at particularly high risk of problem gambling (Fröberg et al., 2015), the exposure of gambling-related advertisements and its normalization across different television programs and times of the day, call for a public health-related focus on risky gambling-related messages in television. Potentially, this may even apply specifically to young males with great involvement in sports, where the risk has been demonstrated to be particularly high, compared to female athletes, and compared to the general population (Håkansson et al., 2018).

Aside from gambling-related advertising in the present study, advertisements promoting loans or other financial services were common. Although partly beyond the scope of the present study, the extent of this kind of advertising may call for further studies of how it relates to gambling behaviors and health in the population. An interplay between rapid loans and gambling may be seen as intuitive, and payday loans have been demonstrated to be associated with poor health (Sweet, Kuzawa, & McDade, 2018), and may present particular risks in relation to gambling (Oksanen, Savolainen, Sirola, & Kaakinen, 2018). Thus, the extent of financial institutes and loans among advertisements is noteworthy, and future research may need to analyze how the dynamics between exposure of gambling and exposure of loans come into play in television advertising.

The present study may have implications for public health-related regulations of television advertisements. Gambling-related advertising was extensive, particularly in the non-land-based television channels, and in several kinds of television shows, including those addressing families and children. Regulations limiting gambling advertising are likely to be accepted by the general public (Thomas et al., 2017). Also, efforts to reduce the riskier types of commercial gambling messages can, through a descriptive content analysis similar to the present one, be followed over time, also in relation to gambling trends and trends in the gambling patterns reported by treatment-seeking patients with gambling disorder. Currently, the legislation in Sweden has been changed, in order to allow for a larger number of licensed gambling operators, in order to allow for responsible gambling requirements to apply to a larger number of operators (Swedish government, 2017). Further follow-up research will need to assess how this changes the extent and content of gambling-related advertising. For example, advertising of land-based casino and electronic gaming machines is illegal and non-existent, while in contrast, although online casino represents the most common gambling type reported in the treatment setting (Håkansson et al., 2017), this type of gambling was also the most commonly one promoted in TV advertising. This clearly calls for action, assumingly with a need for detailed regulations of this particular advertising, considering that a prohibition is in place for land-based gambling types of high addictive potential, whereas promotion of rapid online gambling types are obviously widespread.

The present study has a number of limitations. One 24-h period for each channel was chosen. For practical reasons, the same day could not be analyzed for every channel, and it is unclear to what extent this presents a limitation to the generalizability of the findings. In particular, specific television shows may have a higher or lower exposure of gambling-related advertisements, and in the present study, days with major sports events were not chosen. Clearly, the choice of days, however, potentially could have affected the extent of gambling advertising. In addition, only a proportion of advertising messages were assessed with respect to inter-rater agreement. These 34 advertisements reviewed by both authors were selected by the first author after the full analysis of advertisement content, with the intention for these 34 advertisements to represent a variety of advertisements representing licensed and non-licensed gambling companies, different gambling types, and both entire advertisements and brief messages about companies ‘presenting’ television shows. As these 34 advertisements constitute a proportion of the total of 67 different advertisements addressed, the choice of the advertisements to address presents of limitation. A number of tested variables were erased from further analysis due to low inter-rater agreement. Primarily, several of the types of gambling content with the highest inter-rater agreement were variables describing relatively distinct features, such as whether an advertisement involves a bonus or a free-spin message or not. This type of content analysis may potentially be more difficult for less distinct features such as emotional impressions of advertisements, making these ‘softer’ aspects of advertising more difficult to study, and this may require other types of research designs, such as more in-depth qualitative analyses. Another limitation related to the study of inter-rater agreement is potentially that the selection of the 34 advertisements reviewed in this process, was decided after the full review made by the first author; i.e., a risk of unintentional influence by the first author cannot be fully excluded. However, after the dual review process, it was decided to include or exclude variables as objectively as possible, i.e. through the strict use of Kappa values rather than in a discussion between the authors, in order to limit the analysis to variables which had turned out to have a high inter-rater agreement on their own and without in-depth discussions between the authors.

Even considering these limitations, the present study provides a descriptive picture of how gambling is exposed to television reviewers through advertisements, and that many of commercials communicate messages which potentially may influence public health aspects related to gambling and its consequences. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates a large predominance of one particular type of gambling, online casino, in the advertisements on television in the present setting, and, importantly, online casino advertising was characterized by a number of potentially risky messages, such as those favouring loss of control (free-spins, bonuses), those promoting gambling attitudes (the focus on ‘high rollers’), and the targeting of women, in line with online casino being overrepresented in female gambling disorder patients. In parallel with this, advertising from non-licensed operators was clearly overrepresented with respect to messages favouring loss of control, promoting gambling attitudes (‘high rollers’, social status of gambling), or focusing on either of the genders specifically, rather than focusing on the actual winning. Thus, these aspects were more commonly seen in advertising from operators which are non-licensed and therefore beyond regulatory control, and importantly online casino advertising appeared only in non-licensed operators, putting this gambling type outside of regulations. In total, public health aspects with clinical implications are seen and discussed here. Further and potentially larger studies may be needed, and longitudinal measures may provide trends in gambling advertising, and should take gender aspects into account.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Included television channels and television content included. Names of television shows are translated into English, and Swedish shows appearing only in Swedish are explained briefly.

Role of funding sources

The present research was carried out partially thanks to Dr. Håkansson's general research funding, which is provided from Svenska spel AB (the state-owned Swedish gambling monopoly) to Lund University. This funding is general and unrelated to the present particular study. The funding source had no influence on, and no involvement in, the present study.

Author contributions

AH carried out the major data collection and data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. CW reviewed parts of the advertisements included, for inter-rater agreement, and made significant contributions to the interpretations of results and to the writing of the paper. Both authors approved the final submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the present research project.

AH has a position at Lund University, an employment that was funded by the Swedish state-owned gambling operator Svenska spel AB, as a part of that company's responsible gambling policy, in collaboration with Lund University. This funding is general and unrelated to the present particular study. The funding source had no involvement in the present study, neither in its background idea, design, data collection, interpretation of results, or in the decision to publish results.

Acknowledgements

The authors' research receives a general funding from the Swedish national gambling monopoly, Svenska spel AB. This funding is not specifically provided for the present project, and the funding body does not have any influence on the research idea, design or the interpretation of the findings.

References

- American Psychiaric Association . American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychiatric disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Binde P., Romild U. Self-reported negative influence of gambling advertising in a Swedish population-based sample. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9791-x. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado F., Griffiths M. Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000-2015) Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2016;5:592–613. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans E.G., Thomas S.L., Daube M., Derevensky J., Gordon R. Creating symbolic cultures of consumption: An analysis of the content of sports wagering advertisements in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:208. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2849-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans E.G., Thomas S.L., Derevensky J., Daube M. The influence of marketing on the sports betting attitudes and consumption behaviours of young men: Implications for harm reduction and prevention strategies. Harm Reduction Journal. 2017;14:5. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez D., Aragay N., Soms M., Prat G., Casas M. Male and female pathological gamblers: Bet in a different way and show different mental disorders. Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2014;17:E101. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2014.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling N.A., Cowlishaw S., Jackson A.C., Merkouris S.S., Francis K.L., Christensen D.R. Prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity in treatment-seeking problem gamblers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;49:519–539. doi: 10.1177/0004867415575774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröberg F., Rosendahl I.K., Abbott M., Romild U., Tengström A., Hallqvist J. The incidence of problem gambling in a representative cohort of Swedish female and male 16–24 year-olds by socio-demographic characteristics, in comparison with 25–44 year-olds. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015;31:621–641. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.E., Kim S.W. Gender differences in pathological gamblers seeking medication treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43:56–62. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.29857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.E., Odlaug B.L., Mooney M.E. Telescoping phenomenon in pathological gambling: Association with gender and comorbidities. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2012;200:996–998. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182718a4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A., Mårdhed E., Zaar M. Who seeks treatment when medicine opens the door to gambling disorder patients – Psychiatric co-morbidity and heavy predominance of online gambling. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2017;8:255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A., Kenttä G., Åkesdotter C. Problem gambling and gaming in elite athletes. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2018;8:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Browne M., Russell A.M.T., Greer N., Thomas A., Jenkinson R., Rockloff M. Where's the bonus in bonus bets? Assessing sports bettors' comprehension of their true cost. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9800-0. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Russell A.M.T., Lamont M., Vitartas P. Bet anywhere, anytime: An analysis of internet sports bettors' responses to gambling promotions during sports broadcasts by problem gambling severity. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2017;33:1051–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10899-017-9671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Russell A.M.T., Thomas A., Jenkinson R. Wagering advertisements and inducements: Exposure and perceived influence on betting behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-09823-y. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Vitartas P., Lamont M. Understanding persuasive attributes of sports betting advertisements: A conjoint analysis of selected elements. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017;6:658–668. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Hwang I., LaBrie R., Petukhova M., Sampson N.A., Winters K., Shaffer H. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G.T., Petry N.M. Gender differences among pathological gamblers seeking treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10:302–309. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MMS (Mediamätning i Skandinavien, [‘Media measure in Scandinavia]) Månadsrapport [monthly report, November 2017] 2017. http://mms.se/wp-content/uploads/_dokument/rapporter/tv-tittande/manad/2017/Månadsrapport_2017_11.pdf

- Oksanen A., Savolainen I., Sirola A., Kaakinen M. Problem gambling and psychological distress: A cross-national perspective on the mediating effect of consumer debt and debt problems among emerging adults. Harm Reduction Journal. 2018;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Stinson F.S., Grant B.F. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt H., Thomas S.L., Bestman A., Daube M., Derevensky J. Factors that influence children's gambling attitudes and consumption intentions: Lessons for gambling harm prevention research, policies and advocacy strategies. Harm Reduction Journal. 2017;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt H., Thomas S.L., Bestman A., Daube M., Derevensky J. What do children observe and learn from televised sports betting advertisements? A qualitative study among Australian children. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2017;41:604–610. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt H., Thomas S.L., Bestman A., Stoneham M., Daube M. “It's just everywhere!” children and parents discuss the marketing of sports wagering in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;40:480–486. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Government En omreglerad spelmarknad. Betänkande av spellicensutredningen. [Bill proposal SOU 2017:30. Swedish Department of Finances.] 2017. http://www.regeringen.se/rattsdokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2017/03/sou-201730/ Available (including summary in English) at.

- Sweet E., Kuzawa C.W., McDade T.W. Short-term lending: Payday loans as risk factors for anxiety, inflammation and poor health. SSM Population Health. 2018;5:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.L., Bestman A., Pit H., Cassidy R., McCarthy S., Nyemcsok C.…Daube M. Young people's awareness of the timing and placement of gambling advertising on traditional and social media platforms: A study of 11–16-year-olds in Australia. Harm Reduction Journal. 2018;15:51. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.L., Randle M., Bestman A., Pitt H., Bowe S.J., Cowlishaw S., Daube M. Public attitudes towards gambling product harm and harm reduction strategies: An online study of 16-88 years olds in Victoria, Australia. Harm Reduction Journal. 2017;14:49. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T., Wang J.J. Community treatment for problem gambling: Sex differences in outcome and process. Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;45:468–475. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H. Perceptions, people and place: Findings from a rapid review of qualitative research on youth gambling. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;90:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Included television channels and television content included. Names of television shows are translated into English, and Swedish shows appearing only in Swedish are explained briefly.