Abstract

Delivering well-coordinated care is essential for optimizing clinical outcomes, enhancing patient care experiences, minimizing costs, and increasing provider satisfaction. The Veterans Health Administration (VA) has built a strong foundation for internally coordinating care. However, VA faces mounting internal care coordination challenges due to growth in the number of Veterans using VA care, high complexity in Veterans’ care needs, the breadth and depth of VA services, and increasing use of virtual care. VA’s Health Services Research and Development service with the Office of Research and Development held a conference assessing the state-of-the-art (SOTA) on care coordination. One workgroup within the SOTA focused on coordination between VA providers for high-need Veterans, including (1) Veterans with multiple chronic conditions; (2) Veterans with high-intensity, focused, specialty care needs; (3) Veterans experiencing care transitions; (4) Veterans with severe mental illness; (5) and Veterans with homelessness and/or substance use disorders. We report on this workgroup’s recommendations for policy and organizational initiatives and identify questions for further research. Recommendations from a separate workgroup on coordinating VA and non-VA care are contained in a companion paper. Leaders from research, clinical services, and VA policy will need to partner closely as they develop, implement, assess, and spread effective practices if VA is to fully realize its potential for delivering highly coordinated care to every Veteran.

KEY WORDS: Veterans Health, case management, organization and management, research, health services, integrated delivery systems

INTRODUCTION

As an integrated national healthcare system with a fully electronic medical record (EMR) and substantial investments in primary care integrated with mental health services, the Veterans Health Administration (VA) has built a strong foundation for internally delivering care that is highly coordinated.1 Care coordination is a core component of Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT), VA’s patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, in which PACT nurses serve as care managers.2 For Veterans with heightened needs, specialized care coordinators are dedicated to coordinating care for specific conditions (e.g., cancer, mental illness) or social situations (e.g., homelessness).

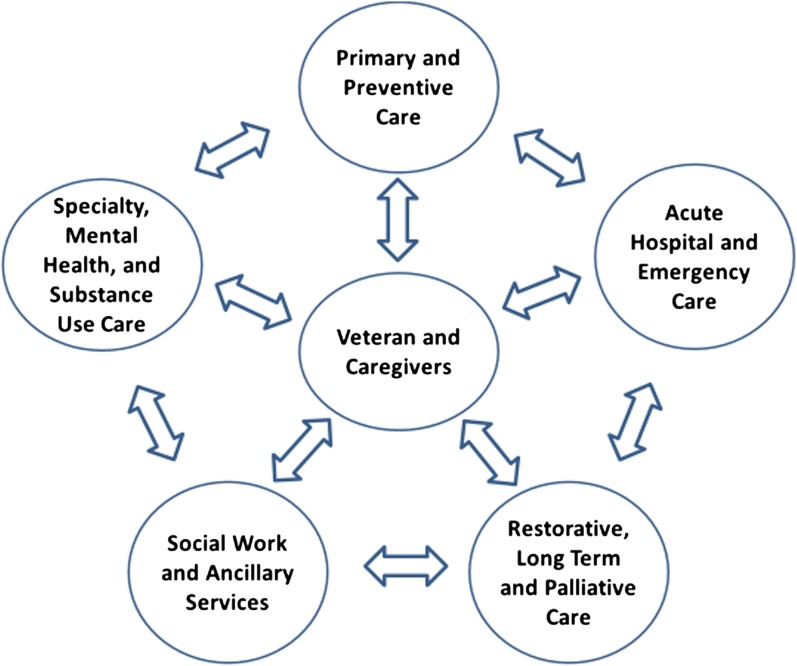

Despite these resources, numerous challenges exist in coordinating care within the VA system, particularly for high-need Veterans. In recent years, the number of Veterans using VA care has grown substantially and VA users have, on average, higher medical and social needs compared to other patient populations.3–6 To meet these needs, VA provides a broad and deep array of services (Fig. 1). Care for high-need Veterans must be coordinated across the VA network of primary and preventive care; specialty, mental health, and substance use care; acute hospital and emergency care; restorative, long-term, and/or palliative care; and social work and ancillary services.2, 7, 8 Veterans must be central in this information exchange, so that care is aligned with Veterans’ priorities.9 With this complex web of services, across multiple providers and settings, Veterans with multiple needs often are assigned to multiple VA care coordinators, and such arrangements may, paradoxically, result in disjointed or duplicative care.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the breadth and depth of services provided by VA (either directly or through purchased care), across which Veterans’ care needs to be coordinated.

Virtual care modalities have created an additional dimension across which care and communication need to be coordinated. VA has been a pioneer in developing and adopting virtual care modalities, including secure electronic messaging, videoconferencing, remote monitoring, and use of smart phone applications.10–13

VA’s care coordination practices therefore need to be updated to meet these challenges. VA leaders are working to evolve the current state into one that better matches the complexity of Veterans’ care coordination needs. To support these efforts, VA’s Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) service held a state-of-the-art (SOTA) conference on care coordination in March 2018. The conference was organized into three separate workgroups: one considering measures and models of coordination, another considering integration across VA and non-VA providers (VA Community Care), and a third considering coordination of care within the VA healthcare system. We report here on the recommendations arising from the third workgroup considering coordination of care within the VA system, with others reporting recommendations from the other workgroups.14,15

METHODS

Prior to the SOTA conference, the planning team scanned the literature to identify Veteran subpopulations with particularly intense coordination needs. We defined these populations by their elevated risk for adverse outcomes, high care utilization, and involvement from multiple providers across the services and settings depicted in Figure 1. Multi-morbidity is common in VA patients, with 32% of non-elderly, and 35% of elderly patients having three or more chronic conditions.16 In a cross-sectional population-based study, the past year prevalence of illicit drug dependence among Veterans was 1.5%; alcohol dependence, 6.3%; and serious mental illness, 3.2%.17 Veterans have a higher risk of homelessness compared to the general population, with a relative risk of 1.3 among male Veterans, and 2.1 among female Veterans.18 Veterans experience approximately 700,000 inpatient admissions, and 1.2 million emergency department visits, annually.3 Therefore, by consensus, the planning team identified five high-need subpopulations that illustrate unique coordination issues: (1) Veterans with multiple chronic conditions (e.g., 3 or more); (2) Veterans with specific needs for high-intensity specialty care services (e.g., those with cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), end-stage renal disease); (3) Veterans experiencing transitions following hospitalization or an emergency department visit; (4) Veterans with serious mental illness; and (5) Veterans with homelessness and/or substance use disorders.

The planning group identified evidence-based care coordination practices from a scan of the research relevant to these populations, selecting studies published in high-impact journals, research in VA populations, and review articles. These manuscripts, summarized in Table 1, were provided to workgroup participants in advance of the conference, along with available information on a current national VA care coordination initiative.22–30 Participants were asked to apply this literature, as well as their own knowledge within their areas of expertise, to identify (1) recommendations regarding policies and organizational initiatives, where the current evidence base was felt to be sufficient to support VA action, and (2) recommendations for a research agenda that will build the evidence base for guiding future VA action. The 16-member workgroup met for 1 day, with time allotted for focused discussion on each of the five subpopulations, and concluded with a discussion to identify overarching themes and refine recommendations. The workgroup included leaders of VA national clinical, policy, and research offices; health services researchers with expertise in these patient subpopulations, care coordination, and transitions of care; and front-line clinicians, including primary care physicians, hospitalists, emergency department physicians, nurses, and social workers.

Table 1.

Summary of Manuscripts Provided to Workgroup Participants in Advance of the Conference

| High-need Veteran subpopulation | Description of study/review | Summary of study/review findings |

|---|---|---|

| Veterans with multiple chronic conditions | Systematic review of comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions or frailty (Hopman et al. 2016)20 | Evidence for the effectiveness of comprehensive care for multimorbid/frail patients is insufficient. |

| Veterans with high-intensity, focused, specialty care service needs | Systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer care coordination (Gorin et al. 2017)18 | Cancer care coordination improves care quality, patient experience, and appropriate care utilization; patient navigation, home telehealth, and nurse care management are frequently used coordination strategies. |

| Semi-structured interviews with VA HIV clinic providers and patients (Fix et al. 2014)19 | Patients in HIV clinics delivering patient-centered medical home-principled care reported more satisfaction with their care. | |

| Veterans experiencing transitions following hospitalization or emergency department use | Systematic review of hospital/post-hospital transitional care interventions (Kansagara et al. 2016)21 | Successful interventions are comprehensive, extend beyond the hospital stay, and have flexibility to respond to individual patient needs. |

| Report on findings from National Quality Forum environmental scan, key informant interviews, and expert panel findings on measuring and improving emergency department transitions of care (NQF 2017)22 | ED transitions measures and concepts in need of development are infrastructure and linkages; health information technology; payment models; and a research agenda. | |

| Veterans with severe mental illness | Key informant interviews at two VA medical centers with mental health staff embedded in primary care clinics (Lipshitz et al. 2017) [23] | Barriers to optimal implementation include organizational competing priorities, finding assertive care managers to hire, cross-discipline integration and collaboration, and primary care provider burden; formal structural attention to care management may improve the reliability of care management functions. |

| Veterans with homelessness and substance use disorder | Secondary (latent class) data analysis of 16,912 homeless Veterans who were acute care “super-utilizers” (Symkowiak et al. 2017)23 | Persistent acute care superutilizers were more likely to be older, rural, male, non-Hispanic White, unmarried, and have more service-connected disabilities and medical, mental health and substance use morbidities. |

| Across Veteran subpopulations | Original study: cross-sectional correlation analysis assessing if implementation of a newly developed care coordination model was associated with more effective care coordination in safety net primary care practices (Wagner et al. 2014)24 | Suggested that the care coordination model elements may have enabled the safety net clinic to better coordinate care. |

RESULTS

Overarching Themes

The discussion resulted in five overarching themes. First, care coordination systems need to be capable of addressing Veterans’ multiple medical and psychosocial factors as well as flexible to adapt to Veterans’ varying circumstances. No single activity or program will work for all Veterans, conditions, or settings; rather, programs must be responsive to the diversity of Veterans’ needs. For example, a program to care for Veterans residing in rural locations who use multiple telehealth services would be very different than one addressing homeless Veterans who frequently use the emergency department. Second, providers and staff in care coordination programs need to have clearly established roles, responsibilities, and communication mechanisms, with associated accountability. Third, for many care coordination practices, there is lack of consistent evidence that they improve clinical or cost outcomes and more rigorous research is needed. While we recognize the independent value of coordination practices that improve patient and provider experience, evidence on these outcomes is also limited. Fourth, understanding the landscape of care coordination in VA is requisite to further improvement. However, there are currently no sources for comprehensively cataloguing the current state of practice within VA. Finally, we need to avoid the potential for new care coordination programs to introduce additional operational silos.

Recommendations for VA Policies and Organizational Initiatives

Based on the current state of knowledge, the workgroup formulated eight recommendations for VA policies and organizational initiatives, shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recommendations for Policies and Organizational Initiatives, and Research Questions, for Care Coordination Within the Veterans Health Administration (VA)

| High-need veteran subpopulation | Recommendations for policies and organizational initiatives | Research questions |

|---|---|---|

| Veterans with multiple chronic conditions | • None with sufficient evidence base at this time |

• What are the best ways to identify Veterans’ dominant medical, social, and behavioral needs, and match services to those needs? • How can we measure collaboration between the multiple providers caring for Veterans? |

| Veterans with high-intensity, focused, specialty care service needs | • None with sufficient evidence base at this time |

• What is the potential value of primary care models centered around “specialty care” patient-aligned care teams for Veterans with high-intensity, focused, specialty service needs? • For which medical conditions and Veterans would such models be appropriate? • How would such models match with Veterans' preferences? • How would such models ensure that Veterans’ needs across all medical, behavioral, and social domains are met? • How can such models be implemented without increasing fragmentation? • What resources and processes would be needed to implement and support such models? • How does provider culture affect the implementation of such models? |

| Veterans experiencing transitions following hospitalization or emergency department use | • VA should implement models of shared accountability, and modalities for structured communications, across transitions in care. |

• What is the epidemiology of care coordination failures across these transitions in VA, and where are the greatest opportunities for improvement? • Which Veterans would benefit most from more-intensive outreach and what is the role, and effectiveness, of models of differing intensity? • How can successful models of shared accountability and structured communications best be implemented in VA to optimize their utility? • Who are the appropriate providers for delivering this support? |

| Veterans with severe mental illness | • VA should develop more robust systems for triaging Veterans with mental health issues, to connect them with the right level of service, within clinically appropriate timeframes, with maximum treatment continuity. |

• What processes could better identify and steer Veterans to appropriate specialty mental healthcare services? • When are in-person hand-offs necessary and when and how can virtual handoffs be utilized, while still achieving effective care coordination? |

| Veterans with homelessness and substance use disorder |

• VA should expand homeless coordination services, and expand capacity to effectively deliver services to women Veterans who are homeless. • VA should expand and improve care coordination for Veterans with substance use disorders, including the capacity for pharmacologic management across care transitions. |

• What services are most effective for coordinating care for Veterans who do not engage in current care structures and what models can bring coordination services to these highest-risk Veterans? • How can new models or structures further augment care coordination for Veterans in substance-use disorders? |

| Across Veteran subpopulations |

• VA should inventory its existing care coordination services and identify promising practices at individual sites that could be disseminated. • For Veterans with care needs spanning multiple providers, VA should establish policies and procedures so that there is communication among the Veterans’ providers, and with the patient, about the roles and responsibilities of each provider. • VA should adapt existing care coordination programs to allow implementation in sites where there are trainees, part-time providers, and/or high-turnover of providers and staff. • VA should continue and expand the use of technologic innovations in supporting care coordination. |

• How does use of telehealth and virtual care modalities impact quality and coordination of care? • How should care models using telehealth and other virtual care modalities be designed to enhance coordination of care? • For which Veterans, and in which situations, is it appropriate to use telehealth and other virtual care modalities? |

Four of the eight recommendations apply specifically to the identified high-need Veteran sup-populations:

For Veterans experiencing transitions in care, models that promote shared accountability and facilitate structured communications are needed.

For Veterans with severe mental illness, robust systems for triaging and connecting Veterans to the appropriate level of needed services, as well as enhanced systems to facilitate treatment continuity, will improve coordination for this vulnerable subpopulation.

For Veterans who are homeless, VA should coordinate across medical and social services to more effectively deliver needed care, particularly for women Veterans who may have heightened needs (e.g., child dependents) and vulnerabilities (e.g., history of military sexual trauma).

For Veterans with substance use disorders, expanding and coordinating services for treatment, including mechanisms for coordinating services between substance use counselors and prescribers of medication-assisted therapy, should be a high priority.

The workgroup determined that more research is needed prior to making recommendations specific to the remaining subpopulations.

The remaining recommendations for VA policies and organizational initiatives apply to all five high-need subpopulations, as well as to Veterans with less-intense coordination needs:

As a foundation for strategically improving care coordination, VA needs to conduct an inventory of existing care coordination services, identifying gaps and promising practices.

Policies and procedures regarding provider communication, roles, and responsibilities need to be developed and maintained to minimize miscommunications and build trusting relationships and collaborations between providers.

VA care coordination practices need to explicitly incorporate trainees and academic practices, since educating and training health professionals is a core VA mission, with nearly 123,000 trainees working in VA in 2017.19

Although VA has been at the forefront in technologic innovations in the delivery of healthcare, VA needs to further develop and use technology for effective coordination of care.

Recommendations for a Research Agenda

The workgroup also formulated recommendations for a research agenda that would build the evidence base for guiding VA in designing and implementing optimal care coordination systems for high-need Veterans. The workgroup noted that, although evidence-based care coordination practices that are developed and implemented outside VA should inform VA practices, they need to be assessed for their applicability within the unique context of the VA and may need to be tailored to Veterans’ needs. Further, the use of reliable, yet timely and logistically feasible methods for evaluating promising practices is essential. To date, many studies have used pre-post evaluation designs which lack contemporaneous controls and may be unreliable due to regression to the mean or other unmeasured confounding factors. The VA, with over 160 medical centers, could study new coordination models through stepped-wedge and/or group-randomized trial designs.20, 21

The specific research questions identified by the workgroup as needing attention are summarized in Table 2. Veterans with multiple chronic conditions are at a particularly high risk for poor outcomes and costly care.16 Research is needed to determine optimal mechanisms for identifying these Veterans’ care needs, including social determinants of health, and for aligning services to those needs. Developing measures for assessing collaboration between the multiple providers caring for these Veterans would also allow researchers to examine an intervention’s effect on collaborations and, in turn, how these collaborations affect outcomes.

For Veterans with high-intensity, focused specialty care needs, the workgroup discussed the potential value of VA implementing “Specialty Care PACT” models in which specialists assume primary ownership of care coordination in situations where the preponderance of the patient’s care needs fall within that specialty. Such models currently exist within VA, in select locations, for Veterans with HIV.25 Although these models have face validity, there is limited research on their effectiveness and implementation beyond a few leading centers. More research is needed to determine which medical conditions and patients would benefit from these models; their effects on Veteran satisfaction and perceptions of coordination; optimal configurations of providers’ roles and responsibilities; arrangements for meeting needs of rural Veterans and others with geographic barriers to specialty care services; organizational determinants (e.g., resources, processes, culture) of these models being feasible and effective; and potential unintended consequences of these models, such as increasing fragmentation or gaps in preventative care outside the specialists’ area of expertise.

Multiple studies have documented that failures in care coordination during transitions following hospitalizations are associated with adverse outcomes, increased costs, and poor patient experiences.29, 31–33 Although less studied, patients not receiving needed care following ED visits are also associated with adverse outcomes.30, 34–36 However, much less is known about care coordination across these transitions in VA or where levers exist for improvement.37, 38 Successful intensive coordination models for post-hospitalization transitions have been developed and shown as being effective in non-VA settings.29 Research is needed on the extent to which they would be valuable for VA, and how these proven models should best be adapted to fit within the VA context, including PACT. Further, researchers should investigate how to target intensive coordination efforts to those Veterans who would benefit the most.

A sizable proportion of Veterans could benefit from the wide array of mental health services available in VA.39, 40 For Veterans with mental health needs presenting to settings outside VA’s mental health clinics, research is needed on processes for identifying and characterizing their needs, both in type and acuity, and then steering them to appropriate care, with effective and efficient hand-offs.41 Further, as VA has embarked on integrating primary care and mental health teams, knowledge is needed regarding factors that are associated with successful implementation.

VA has expansive programs tailored for Veterans with homelessness and/or substance use disorders. Research is needed to develop and test innovative models that would be most effective in connecting high-risk homeless and substance-using Veterans to care coordination resources, which in turn can help to engage them in VA’s medical, mental health, substance use, housing, and social work services.

Finally, although VA has been a pioneer in the use of telehealth and virtual care modalities, more research is needed to guide development and use of technology for care coordination, and to determine how to maintain coordinated care when virtual care is employed. Recent legislation and changes in regulations will dramatically increase VA’s use of virtual care.10 Therefore, there is an urgent need to assess which Veterans and situations are appropriate for these modalities, and how their use affects care coordination. Although the use of these technologies has great promise for improving access to care, as well as coordination, it is essential to assess for their potential unintended consequences on care fragmentation (e.g., if there is separation, without effective communication mechanisms, between virtual care and in-person care providers).

LIMITATIONS

These recommendations should be interpreted in light of the limitations of our evidence-informed consensus process. First, our SOTA workgroup did not establish levels of priority for their recommendations, nor discuss logistics for accomplishing them. These would be the next steps in realizing the recommended actions. Secondly, our workgroup solely focused on coordination of care internal to the VA system. Recent legislation has enabled Veterans to access community (non-VA) care. The additional associated coordination challenges that accompany Veterans’ increasing dual use of VA and community care cannot be overstated, and therefore were the focus of a separate SOTA conference workgroup dedicated to that topic. The recommendations from that workgroup are described by others.14

CONCLUSION

Achieving optimal care coordination for high-need Veterans is a priority within VA. Our workgroup highlighted policy and organizational initiatives that are ready for immediate consideration as VA embarks on new care coordination models. Numerous questions remain, however, that VA researchers can address to guide future practice and policy. Partnerships between research, clinical, and policy leaders in developing, implementing, assessing, and spreading evidence-based care coordination practices will be paramount for VA to successfully realize its potential for delivering highly coordinated care to every Veteran.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Geraldine McGlynn and Karen Bossi in organizing the SOTA conference, and for administrative support in the preparation of this manuscript. We would also like to thank the members of the SOTA workgroup who contributed to formulating these recommendations, but did not participate in the writing of this manuscript: Cicely Burrow-McElwain, LCSW-C; June Callasan, MSN, RN, CCM; Angela Denietolis, MD; and Laura Taylor, MSW, LSCSW.

Funding

This work was funded by the VA Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All authors are employees of the Department of Veterans Affairs. No authors reported any additional conflicts of interest with this work.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Leung LB, Yoon J, Rubenstein LV, Post EP, Metzger ME, Wells KB, et al. Changing Patterns of Mental Health Care Use: The Role of Integrated Mental Health Services in Veteran Affairs Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):38–48. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, Hebert PL, Liu CF, Dolan E, Taylor L, et al. Implementation of the Patient-centered Medical Home in the Veterans Health Administration: Associations with Patient Satisfaction, Quality of Care, Staff Burnout, and Hospital and Emergency Department Use. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1350–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, available at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/utilization.asp. Accessed December 7th, 2018.

- 4.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are Patients at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers Sicker?: A Comparative Analysis of Health status and Medical Resource Use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Nelson KM, Jakupcak M, Simpson TL. Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoerster KD, Lehavot K, Simpson T, McFall M, Reiber G, Nelson KM. Health and Health Behavior Differences: U.S. Military, Veteran, and Civilian Men. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vimalananda N, Dvorin K, Fincke BG, Tardiff N, Bokhour BG. Patient, Primary Care Provider, and Specialist Perspectives on Specialty Care Coordination in an Integrated Health Care System. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41(1):15–24. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuchowski JL, Rose DR, Hamilton AB, Stockdale SE, Meredith LS, Yano EM, et al. Challenges in Referral Communication Between VHA Primary Care and Specialty Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):305–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3100-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A Systems Approach to Patient-Centered Care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848–2851. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirsh SR, Ho PM, Aron DC. Providing Specialty Consultant Expertise to Primary Care: An Expanding Spectrum of Modalities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(10):1416–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darkins A. The Growth of Teleheatlh Services in the Veterans Health Administration Between 1994 and 2014: A Study of the Diffusion of Innovation. Telemedicine and e-Health., 2014; 20(9): 10.1089/tmj.2014.0143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Veterans E-Health and Telemedicine Support Act of 2017. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s925/BILLS-115s925es.xml. Accessed July 27th, 2018

- 13.VA Telehealth Services. https://www.telehealth.va.gov/. Accessed July 27th, 2018

- 14.Mattocks K, Cunningham K, Elwy AR, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of cross-system care coordination from the VA state-of-the-art working group on VA/non-VA care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019; 10.1007/s11606-019-04972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.McDonald K, Singer S, Gorin SS, et al. Incorporating theory into practice: Reconceptualizing exemplary care coordination initiatives from the US Veterans health delivery system. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019; 10.1007/s11606-019-04969-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Yoon J, Zulman D, Scott JY, Maciejewski ML. Costs Associated with Multimorbidity Among VA Patients. Med Care. 2014;52:S31–S36. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pemberton MR, Forman-Hoffman VL, Lipari RN, et al. Prevalence of Past Year Substance Use and Mental Illness by Veteran Status in a Nationally Representative Sample. SAMHSA Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, November 2016, available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DR-VeteranTrends-2016/NSDUH-DR-VeteranTrends-2016.htm. Accessed December 7th, 2018

- 18.Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and Risk of Homelessness Among US Veterans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VA Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 Statistics: Health Professions Trainees. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics_Short_2017.pdf. Accessed July 26th, 2018.

- 20.Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. The stepped wedge cluster randomized trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2015; 35 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Turner EL, Li F, Gallis JA, Prague M, Murray DM. Review of recent methodological developments in group-randomized trials: Part1—Design. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):907–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipshitz JM, Benzer JK, Miller C, Easley SR, Leyson J, Post EP, et al. Understanding collaborative care implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs: core functions and implementation challenges. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(691):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D, et al. Health care coordination theoretical frameworks: a systematic scoping review to increase their understanding and use in practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. 10.1007/s11606-019-04966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, Fairfield KM, Krebs P, Clauser SB. Cancer Care Coordination: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 30 Years of Empirical Studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):532–546. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fix GM, Asch SM, Saifu HN, Fletcher MD, Gifford AL, Bokhour BG. Delivering PACT-Principled Care: Are Specialty Care Patients Being Left Behind? J Gen Int Med. 2014;29(S2):695–702. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2677-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szymkowiak D, Montgomery AE, Johnson EE, Manning T, O’Toole TP. Persistent Super-Utilization of Acute Care Services Among Subgroups of Veterans Experiencing Homelessness. Med Care. 2017;55:893–900. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Coleman K, Phillips K, Sugarman JR. Improving Care Coordination in Primary Care. Med Care. 2014;52:S33–S38. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopman P, DeBruin SR, Forjaz MJ, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Tonnara G, Lemmens LC, et al. Effectiveness of comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions or frailty: A systematic literature review. Heath Policy. 2016;120(7):818–832. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kansagara D, Chiovaro JC, Kagen D, Jencks S, Rhyne K, O’Neil M, et al. So many options, where do we start? An Overview of the Care Transitions Literature. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):221–230. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Quality Forum: Emergency Department Transitions of Care [Internet] – A Quality Measurement Framework Final Report. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/08/Emergency_Department_Transitions_of_Care_-_A_Quality_Measurement_Framework_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed July 26th, 2018

- 31.Bull MJ, Hansen HE, Gross CR. Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000;14(3):76–87. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clare J, Hofmeyer A. Discharge planning and continuity of care for aged people: indicators of satisfaction and implications for practice. Aust J Adv Nurs. 1998;16(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:646–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunez S, Hexdall A, Aguirre-Jaime A. Unscheduled returns to the emergency department: an outcome of medical errors? Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(2):102–108. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly AM, Chirnside AM, Curry CH. An analysis of unscheduled return visits to an urban emergency department. N Z Med J. 1993;106(61):334–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierce JM, Kellerman AL, Oster C. “Bounces”: an analysis of short-term return visits to a public hospital emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(7):752–757. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens C, Sackett N, Pierce R, Schopfer D, Schmajuk G, Moy N, et al. Transitional care challenges of rehospitalized veterans: listening to patients and providers. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(5):326–331. doi: 10.1089/pop.2012.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, Weinberger M, Goldberg KC, Oddone EZ. Adverse Health Outcomes After Discharge from the Emergency Department – Incidence and Risk Factors in a Veteran Population. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1527–31. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, Pomerantz A, Saxon AJ, Piette JD, et al. Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Prognosis of Mental Health Among US Veterans. AJPH. 2015;105(12):2564–2569. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fox AB, Meyer EC, Vogt D. Attitudes About the VA Health-Care Setting, Mental Illness, and Mental Health Treatment and Their Relationship with VA Mental Health Service Use Among Female and Male OEF/OIF Veterans. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(1):49. doi: 10.1037/a0038269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bovin Mj, Miller Cj, Koenig CJ, Lipschitz JM, Zamora Ka, Wright PB, et al. Veterans’ experiences initiating VA-based mental health care. Psychol Serv.. 2018. Advance online publication. 10.1037/ser0000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]