Abstract

Background

Multiple comorbidities thought to be associated with poor coordination due to the need for shared treatment plans and active involvement of patients, among other factors. Cardiovascular and mental health comorbidities present potential coordination challenges relative to diabetes.

Objective

To determine how cardiovascular and mental health comorbidities relate to patient-centered coordinated care in the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Design

This observational study used a 2 × 2 factorial design to determine how cardiovascular and mental health comorbidities are associated with patient perceptions of coordinated care among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus as a focal condition.

Participants

Five thousand eight hundred six patients attributed to 262 primary care providers, from a national sample of 29 medical centers, who had completed an online survey of patient-centered coordinated care in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Main Measures

Eight dimensions from the Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care (PPIC) survey, a state-of-the-art measure of patients’ perspective on coordinated and patient-centered care.

Key Results

Mental health conditions were associated with significantly lower patient experiences of coordinated care. Hypotheses for disease severity were not supported, with associations in the hypothesized direction for only one dimension.

Conclusions

Results suggest that VA may be adequately addressing coordination needs related to cardiovascular conditions, but more attention could be placed on coordination for mental health conditions. While specialized programs for more severe conditions (e.g., heart failure and serious mental illness) are important, coordination is also needed for more common, less severe conditions (e.g., hypertension, depression, anxiety). Strengthening coordination for common, less severe conditions is particularly important as VA develops alternative models (e.g., community care) that may negatively impact the degree to which care is coordinated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-04979-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: care coordination, Veterans, diabetes, mental health, primary care, comorbidities

INTRODUCTION

Coordination remains a signature challenge for healthcare. Multiple factors in the delivery system increase opportunities for care fragmentation and make it increasingly difficult to deliver coordinated care, at a reasonable cost.1 The rapid expansion of medical knowledge and the related specialization among physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals, in particular, makes coordination difficult by increasing the number of individuals involved in care for a given patient.2 Coordination ensures completion and synchronization of activities and decisions to accomplish effective delivery of care. Coordinated care can be accomplished through organizational processes, procedures, and information exchange; formal relationships between organizations such as contracts; formal relationships among parts of organizations such as services or clinics; and informal relationships among people.

Patient experiences may be the most straightforward measure of whether or not care is coordinated. Integrated care has emerged as a framework for representing care coordination from a patient-centered perspective.3 Patients are thought to experience the construct of integrated care through the empirically related concepts of care coordination and patient-centered care.4 Patient experiences of coordinated care include experiences of knowledge integration across time and settings, staff knowledge of treatment, support for self-directed care, timely communication of test results, qualities of treatment-related communication, information flow to specialists, and coordination during hospital transitions.5 Authors have distinguished between integration and care coordination arguing that integration eliminates the need for care coordination because integrated systems are unified into synergistic whole.5 For purposes of this paper, consistent with the rest of this special issue, we treat these terms as roughly synonymous, emphasizing how patient-centered integrated care enables coordination.

The potential for delayed and unsuccessful information sharing and treatment is exacerbated by the increasing prevalence of multiple chronic conditions and their associated complicated treatment regimens, often requiring the involvement of multiple specialists.6 Multiple comorbidities are associated with poor coordination, polypharmacy, treatment burden, mental health challenges, functional challenges, reduced quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization.7 One challenge to treating comorbidity is the development of shared treatment plans. Shared treatment plans are needed when knowledge and responsibility for treatment is distributed across individual providers such as between primary care providers and specialists. Higher severity diseases are more likely to require specialist involvement and the concomitant need for shared treatment plans. Low-severity comorbidities may be effectively managed within primary care and therefore be less likely to require shared treatment plans. Shared treatment plans may be easier to develop when diseases are concordant, in that diseases with the same pathophysiologic risk are likely to share the same disease management plan.8 In contrast, discordant diseases (i.e., those “not directly related in either pathogenesis or management8”) may be more challenging to manage across primary and specialty care.

Hypothesis 1: Higher severity comorbidities have increased challenges to coordination compared to lower severity comorbidities due to the need for shared treatment plans.

A second challenge to treating comorbidity is the active involvement of patients in their treatment. Mental health conditions are typically discordant with medical conditions. Patients with mental health comorbidities report a low preference for involvement in medical decision-making, despite a high preference for involvement in mental health decision-making.9–11 This preference for low involvement in medical decision-making presents challenges to medical treatment adherence.12,13

Hypothesis 2: Mental health comorbidities have increased challenges to coordination compared to cardiovascular comorbidities due to decreased patient involvement in medical treatment.

Hypothesis 3: High-severity mental health conditions have the highest challenges to coordination compared to low-severity cardiovascular conditions due to both decreased patient involvement and the need for shared treatment plans.

Diabetes care exemplifies potential coordination challenges both in terms of treatment of the disease and in management of comorbidities. Diabetes care includes medical management, patient self-management, and clinician support for self-management.8 Comorbidities can vary in terms of the degree to which their treatment aligns or interferes, i.e., the degree of concordance or discordance, with diabetes treatment. Cardiovascular diseases are examples of conditions likely to be concordant with diabetes,14 and mental health conditions are examples of discordant conditions that have been associated with poor treatment outcomes in diabetes.15–18

This is the first study to empirically test patient and disease characteristics that may influence patient-experienced coordinated care. This study will characterize the level of patient-centered coordinated care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), a healthcare system that has invested heavily in organizational, social, and process-based modes of integration and coordination.19–21 This study will determine the extent to which gaps in patient-centered coordinated care associated the severity and discordance of comorbidities may remain even in an integrated system such as the VA. The VA Central Institutional Review Board approved the study.

METHODS

Participants

Patients were identified using inpatient and outpatient ICD-9 codes during calendar years 2014 and 2015. To screen out inactive patients, we excluded those who did not have at least two outpatient visits for any reason in 2015. We included patients who had at least two encounters with ICD codes for diabetes and also two encounters with ICD codes for one of four comorbidity groups: high- and low-severity cardiovascular and mental health comorbidities. For the cardiovascular comorbidities, we selected hypertension as the low-severity condition and congestive heart failure as the high-severity condition. For the discordant comorbidities, we selected depression and anxiety as low-severity mental health conditions and schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as the high-severity conditions. We excluded patients whose ICD codes indicated overlap in more than one comorbidity group, with the exception of hypertension, which was allowed to be comorbid with heart failure and depression/anxiety due to its high prevalence.

Survey Data Collection

We sampled patients from 262 primary care providers, from a national sample of 29 medical centers, who had completed an online survey as part of a national study of coordinated care. For each provider, we randomly selected 15 patients from each of the four comorbidity groups (medical cardiovascular vs mental health) and severity (low vs high). Patients were recruited using up to four mailings by a third-party contractor between April 13, 2016, and September 2, 2016, following a modified Dillman approach.22 Both paper and online data collection methods were used. Surveys were distributed to 15,120 patients, oversampling for mental health to adjust for potential higher non-response (8558 mental health; 6563 cardiovascular). We collected 7339 patient surveys (49% response rate). For this study, we used data from the 5806 patients who confirmed on the survey that they had received care in the prior six months from one of the 262 previously surveyed primary care providers.

Data Sources

The study included survey data regarding patient experiences of the prior six months, matched to their 2016 administrative data.

Patient-Centered Coordinated Care

We measured coordinated care using a patient self-report survey, the Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care (PPIC) survey.4,23 Two versions of the patient survey were drafted, one for patients who had a cardiovascular comorbidity (hypertension, congestive heart failure) and one for patients who had a mental health comorbidity (anxiety/depression, SMI/PTSD). The surveys were identical except for a subset of questions asking about care from specialists (i.e., either mental health or cardiovascular). The survey instrument contained 92 items and took about 30 min to complete. Most questions use a 4-point Likert-type response scale (e.g., 1 = never, 4 = always). When a different number of response options were used, items were converted to a 4-point scale.

A factor analysis verified a previously reported seven-dimension factor structure in the VA sample, but indicated that the knowledge integration dimension could be better represented by two factors, which we labeled fragmentation and knowledge integration. Knowledge integration across time and settings was a 4-item measure (α = 0.81) of whether the primary care provider was well informed of the patient’s treatment and key concerns. Knowledge fragmentation was a 5-item measure (α = 0.69) of the amount that a patient needs to remind the primary care provider or repeat information. Staff knowledge of medical treatment was a 3-item measure (α = 0.81) of whether primary care staff are well informed about treatment. Support for self-directed care was a 4-item measure of the degree to which care meets the patent’s goals (α = 0.80). Treatment-related communication was a 5-item scale about medication-related communication and contacts between visits (α = 0.82). Communication of test results was a 3-item scale about the clarity and timeliness of communication of test results (α = 0.74). Information flow to specialists was a 4-item scale of whether specialists were well informed about the care patients receive from other providers (α = 0.73). Hospital transitions was a 5-item scale that assesses whether the primary care provider contacted the patient during and after hospitalization and the quality of information provided at discharge and whether the primary care provider was well informed (α = 0.77).

Patient-Reported Covariates

Relationship status was measured with a dichotomous item asking whether the patient was married or living with a significant other (0 = single). Survey help was measured using a dichotomous item that asked whether someone helped the patient complete the survey; this item may be a proxy for disability. Response bias was measured using the LOT-R Life Orientation Test,24 a 6-item measure of optimism/pessimism towards life with four distraction items, each measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Demographic variables included age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Age was measured in ten-year categories and converted to a continuous scale using median ages, and divided by 10 to facilitate interpretation (i.e., 35–44 was recoded to 3.95, with 75 + recoded to 7.95). Sex was coded as female with male as the comparison. Race included White, Black/African American, or other (consisting of American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Other). Ethnicity was a dichotomous endorsement of Hispanic, Latino, or Latina origin or descent.

Administrative Data Covariates

Discordant comorbidities were measured for each patient as a count variable indicating the number of comorbidities considered discordant with diabetes (range 0–8). We used the Elixhauser method25 to classify comorbidities and used prior research14 to categorize comorbidities as diabetes discordant. Diabetes severity was measured using the Diabetes Severity Complication Index (DCSI) using ICD codes, laboratory, and pharmacy data that generated a score ranging from 0 to 13.26

Analyses

We used random-intercept modeling (SAS PROC GLIMMIX) to account for nesting of patients within providers and medical centers. We estimated eight models, one for each of the PPIC dimensions, and included all covariates in each model. One model (where information flow to specialists was the dependent variable) used only a medical center-level random intercept due to convergence problems. We addressed item-level missing data using mean imputation by averaging items within a scale. We used multiple imputation to address scale-level missing data. We used SAS PROC MI to impute ten missing data sets, conducted SAS PROC GLIMMIX on each data set, and used PROC MIANALYZE to estimate the combined parameters. Significance tests were evaluated using p < 0.05. Analyses for this paper were generated using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that the participant sample was mostly White and male, with a mean age of 68 years. This is consistent with the Veteran population in 2015 which was 93% White, and 91% male, with an average age of 60.5 years.27 Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the study variables prior to missing data imputation. Most participants completed the PPIC scales; the lower response rate for information flow to specialists, staff knowledge of medical history, and hospital transitions was due to survey design. That is, we only asked those questions to patients who respectively reported that they received care from a specialist or a non-medical provider (e.g., nutritionist), or had an inpatient stay. Because the missing data is not random, we imputed missing data once for the first five PPIC dimensions, and then once for each of the remaining three dimensions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Patients in the Sample (N = 5807)

| Measure | N | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 2900 | 90.8 |

| Female | 136 | 5.0 |

| Not reported | 147 | 4.2 |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 4469 | 77 |

| Black/African American | 911 | 15.7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/Native | 242 | 4.2 |

| Not reported | 185 | 3.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 208 | 6.3 |

| Non-Hispanic | 2726 | 86.7 |

| Not reported | 249 | 7.0 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/living together | 3875 | 66.7 |

| Not married | 1790 | 30.8 |

| Not reported | 142 | 2.4 |

| Received help on survey | ||

| Yes | 704 | 12.1 |

| No | 4968 | 85.6 |

| Not reported | 135 | 2.3 |

| Measure | Mean | SD |

| Age | 67.92 | 8.20 |

| Discordant comorbidities | 0.52 | 0.91 |

| Diabetes severity score | 0.90 | 1.44 |

Table 2.

Patient Perceptions of Patient-Centered Coordinated Care Scores

| Measure | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge fragmentation | 5491 | 1.53 | 0.69 |

| Knowledge integration | 5724 | 3.18 | 0.83 |

| Support for self-directed care | 5714 | 3.00 | 0.85 |

| Treatment-related communication | 5620 | 2.48 | 0.93 |

| Communication of test results | 4942 | 3.38 | 0.79 |

| Information flow to specialists | 3720 | 3.29 | 0.85 |

| Staff knowledge | 3448 | 3.02 | 0.91 |

| Hospital transitions | 1647 | 2.84 | 0.95 |

| Response bias scale | 5807 | 2.64 | 0.60 |

Coordinated Care Modeling

We present results for our tests of the impact of comorbidity and severity on patient-centered coordinated care in Table 3. Consistent with hypothesis 1, higher severity comorbidities were associated with higher knowledge fragmentation and lower treatment-related communication. However, unexpectedly, higher severity comorbidities were also associated with higher information flow to specialists and better hospital transitions. Also unexpectedly, the number of additional discordant conditions was associated with perceptions of higher support for self-directed care, higher treatment-related communication, and better hospital transitions. Diabetes severity was associated with higher perceived information flow to specialists and hospital transitions. Supporting hypotheses 2, there is a consistent and significant negative association of mental health comorbidities with seven of the eight dimensions of patient-centered coordinated care compared to cardiovascular comorbidities.

Table 3.

Random intercept regression for each of the eight dimensions of patient-centered coordinated care

| Variable | Knowledge Fragmentation | Knowledge Integration | Support for Self−Directed Care | Treatment-related communication | Communication of test results | Staff Knowledge | Specialist Knowledge | Hospital Transitions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.10 | 0.10 | 3.01 | 0.12 | 3.04 | 0.12 | 3.05 | 0.13 | 3.17 | 0.12 | 3.03 | 0.16 | 3.23 | 0.14 | 3.18 | 0.28 |

| Mental Health Comorbidity | 0.06* | 0.02 | − 0.13* | 0.02 | − 0.09* | 0.02 | − 0.07* | 0.03 | − 0.10* | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.06 |

| High−Severity Comorbidity | 0.07* | 0.02 | − 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07* | 0.03 | − 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.13* | 0.03 | 0.12* | 0.05 |

| Discordant Conditions | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08* | 0.02 |

| Diabetes Severity | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.02 |

| Relationship Status | − 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.12* | 0.04 |

| Help Completing Survey | 0.11* | 0.03 | − 0.06 | 0.03 | − 0.06 | 0.04 | − 0.05 | 0.04 | − 0.09* | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.08* | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Response Bias | − 0.04* | 0.02 | − 0.06* | 0.02 | − 0.05* | 0.02 | − 0.13* | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.09* | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Age | − 0.06* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | − 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.07* | 0.04 |

| Female (ref = male) | 0.01 | 0.05 | − 0.08 | 0.06 | − 0.05 | 0.06 | − 0.13* | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.13 |

| Hispanic (ref = no) | 0.12* | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | − 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | − 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.11 |

| Black (ref = white) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.09* | 0.03 | 0.14* | 0.04 | 0.07* | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.07 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American (ref = white) | 0.10* | 0.05 | − 0.15* | 0.05 | − 0.19* | 0.06 | − 0.08 | 0.06 | − 0.18* | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.24* | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.11 |

Note: b = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; *significant at p < .05

The demographic variables present a mixed message, Black patients reported higher coordinated care experiences than White patients, while the heterogeneous group of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American patients reported consistently lower coordinated care experiences. Age was associated with less favorable scores on treatment-related communication and hospital transitions, but more favorable scores on knowledge integration and knowledge fragmentation. Patients who reported needing help to complete the survey experienced more knowledge fragmentation, and worse communication of test results and information flow to specialists. Relationship status was protective for knowledge fragmentation and information flow to specialists. The response bias scale was associated with patient experiences of coordinated care on several dimensions such that optimism was positively associated with patient-perceived coordinated care.

Interactions Between Mental Health and High-Severity Comorbidities

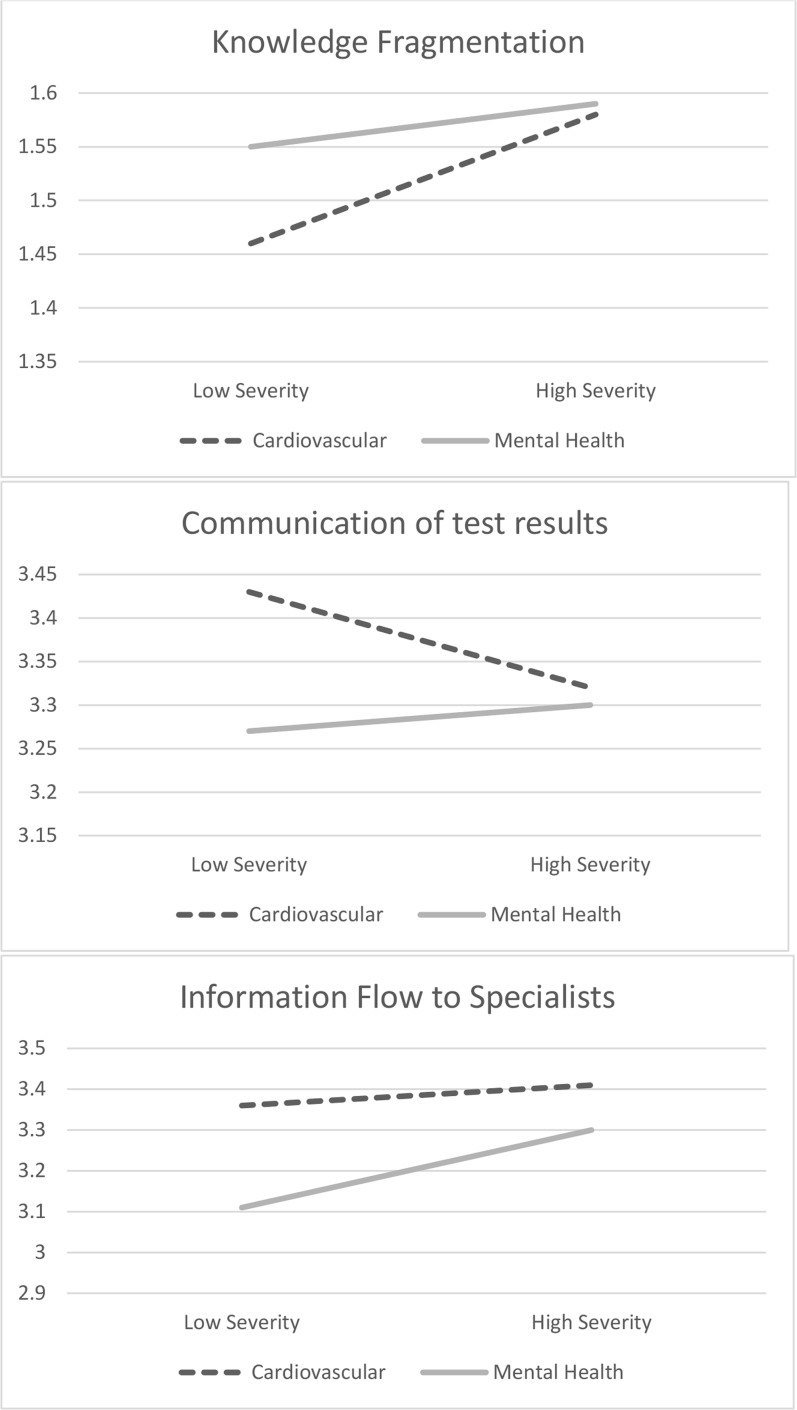

Figure 1 presents the significant interactions. Hypothesis 3 was not supported. Mental health comorbidities were associated with higher knowledge fragmentation and lower communication of test results when severity was lower but not when severity was higher. The simple slope for mental health comorbidity when severity is low was significant for knowledge fragmentation (b = − 0.09; SE = 0.03) and communication of test results (b = 0.17; SE = 0.03). The simple slope of mental health comorbidity was significant for both lower severity (b = 0.27; SE = 0.04) and higher severity (b = 0.11; SE = 0.04) for information flow to specialists.

Figure 1.

Interactions between comorbidity concordance and severity as observed for three dimensions of patient-centered coordinated care. Interactions demonstrate that differences between cardiovascular and mental health comorbidities are most pronounced when severity is low.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to empirically test whether disease characteristics affect care coordination from patients’ perspectives. Having higher severity comorbidities among patients receiving care for type 2 diabetes in the VA healthcare system was associated with higher knowledge fragmentation, supporting the hypothesis that severity increases coordination challenges. However, higher severity comorbidities were also associated with better patient-centered information flow to specialists and hospital transitions. Further, the number of additional discordant conditions was associated with higher support for self-directed care, higher treatment-related communication, and better hospital transitions. One possible explanation is that VA care management programs increase coordination for Veterans with higher disease severity and multimorbidity.

As hypothesized, Veterans with mental health conditions comorbid with diabetes report significantly lower patient experiences of coordinated care compared to Veterans with cardiovascular conditions. This is consistent with prior research indicating that mental health comorbidities are associated with decreased involvement in treatment.9–11 To the degree that patients need to coordinate their own care, lower involvement in treatment will decrease experiences of coordination. Coefficients were modest in magnitude, with the strongest coefficient for information flow to specialists. This is perhaps not surprising because, while the need for primary care physicians to have a good understanding of all of a patient’s medical history is clear, the case for mental health providers having this knowledge may be less apparent. However, it also seems reasonable to suggest that mental health specialists should consider patients’ overall health, which includes their medical comorbidities, when making treatment decisions.

Interactions between mental health and high-severity comorbidities similarly yielded surprising results. Relative to cardiovascular comorbidities, mental health comorbidities were associated with higher knowledge fragmentation and lower communication of test results when severity was low but not when severity was high. This may indicate that VA has been successful at improving coordination for Veterans with PTSD and serious mental illness through specialized programs. Increased coordination support may be necessary for Veterans with depression and anxiety comorbidities.

This study was limited by an observational design and reliance on administrative records for patient selection. For example, the patient sample was selected based on administrative records only and does not differentiate clinical differences within diagnoses (e.g., low-severity heart failure). Misclassification would decrease differences between groups and increase the chance of type II error. This study also included only two types of comorbidities relative to diabetes. Research is needed regarding how other comorbidities and psychosocial problems (e.g., housing, employment, legal, and family problems) could contribute to patient-centered coordinated care. Research should also focus on the provider factors such as length of experience with the patient that might affect patient experiences of care coordination. Despite the limitations, the use of both survey and administrative data in analyses is a strength as it avoids the potential influence of common method variance.28

Results are particularly timely as VA considers how to support care coordination between VA and private sector healthcare organizations. The MISSION Act of 2018 mandates timely scheduling, “continuity of care,” ensuring Veterans can receive care across regional networks, and ensuring that Veterans do not receive lapses in care.29 It is currently unclear how VA will ensure that Veterans receive adequate coordination of care as access to non-VA care increases. However, given that VA is an integrated health system with strong investments in primary care mental health,30 we suspect that patient-centered coordinated care in many US private sector healthcare systems may have larger gaps in addressing care coordination. Future research should seek to replicate findings in non-VA settings, and in particular coordination of care for Veterans with mental health comorbidities.

In conclusion, this is the first study to test how disease characteristics affect patients’ experiences of care coordination. Results indicate that mental health comorbidities are associated with lower patient experiences. Results did not support the hypothesized role of disease severity. A negative association was observed for only one dimension, and positive associations were observed for several dimensions. One possible explanation is that VA has successfully managed the coordination challenges associated with high disease severity. However, results suggest that VA may improve care coordination for Veterans with depression and anxiety. Future research should focus on developing, adapting, and empirically validating care coordination strategies that may impact patients’ perceptions of care coordination.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 15 kb)

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon the work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development Health Services Research and Development (IIR 12-346).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed]

- 2.Sturmberg JP, O’Halloran DM, Martin CM. Healthcare Reform: The Need for a Complex Adaptive Systems Approach. In: Sturmberg JP, Martin CM, editors. Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health. New York: Springer New York; 2013. pp. 827–853. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer SJ, Burgers J, Friedberg M, Rosenthal MB, Leape L, Schneider E. Defining and measuring integrated patient care: promoting the next frontier in health care delivery. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68(1):112–127. doi: 10.1177/1077558710371485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer SJ, Friedberg MW, Kiang MV, Dunn T, Kuhn DM. Development and preliminary validation of the Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer SJ, Kerrissey M, Friedberg M, Phillips R. A comprehensive theory of integration. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718767000. 10.1177/1077558718767000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care — a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, Lewis C, Fahey T, Smith SM. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ. 2015;350. 10.1136/bmj.h176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JR, Drake RE, Wolford GL. Shared decision-making preferences of people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(9):1219–1221. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SR, Bakken S. Preferences for participation in decision making among ethnically diverse patients with anxiety and depression. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(5):466–473. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9323-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moise N, Ye S, Alcántara C, Davidson KW, Kronish I. Depressive symptoms and decision-making preferences in patients with comorbid illnesses. J Psychosom Res. 2017;92:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196–201. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnan EM, Gittelson R, Bartels CM, et al. Establishing chronic condition concordance and discordance with diabetes: a Delphi study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:42. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, et al. Disparities in diabetes care: impact of mental illness. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2631–2638. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreyenbuhl J, Dickerson FB, Medoff DR, et al. Extent and management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(6):404–410. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000221177.51089.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreyenbuhl J, Dixon LB, McCarthy JF, Soliman S, Ignacio RV, Valenstein M. Does adherence to medications for type 2 diabetes differ between individuals with vs without schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):428–435. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, Rosenheck RA. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: A randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darkins A, Ryan P, Kobb R, et al. Care coordination/home telehealth: the systematic implementation of health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management to support the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions. Telemed e-Health. 2008;14(10):1118–1126. 10.1089/tmj.2008.0021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the veterans affairs health care system on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2218–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method -- 2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. Wiley; 2011.

- 23.Kerrissey MJ, Clark JR, Friedberg MW, et al. Medical group structural integration may not ensure that care is integrated, from the patient’s perspective. Health Aff. 2017;36(5):885–892. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaesmer H, Rief W, Martin A, et al. Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R) Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):432–445. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(1):15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. No Title. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.

- 28.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Congress. H.R.5674 - VA MISSION Act of 2018 [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office; [cited 2018 Oct 23]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5674/text?format=txt. Published 2018.

- 30.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Szymanski BR, et al. Initiation of Primary Care-Mental Health Integration programs in the VA Health System: associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Med Care. 2010;48(9):843–851. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e5792b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 15 kb)