Abstract

Purpose of Review

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS) and robotic technology are growing in popularity and are increasing utilized in combination. The purpose of this review is to identify the current successes, potential drawbacks, and future directions of robotic guidance for MIS compared to traditional techniques.

Recent Findings

Recent literature highlights successful incorporation of robotic guidance in MIS as a consistently accurate method for pedicle screw placement. With a short learning curve and low complication rates, robot guidance may also reduce the use of fluoroscopy, operative time, and length of hospital stay.

Summary

Recent literature suggests that incorporating robotic guidance in MIS improves the accuracy of pedicle screw insertion and may have added benefits both intra- and postoperatively for the patient and provider. Future research should focus on direct comparison between MIS with and without robotic guidance.

Keywords: MIS, Spine, Robot, Navigation, Pedicle, Fluoroscopy

Introduction

The use of robotics in surgery has been successfully employed across many surgical subspecialties. It has been estimated that the Da Vinci® (Intuative Surgical; Sunnyvale, California, USA) system alone has been involved in as many as 450,000 cases annually and was reportedly associated with decreased blood loss and shorter hospital stays [1] [2]. Recently, robotic systems have become more integrated into spine surgery, with attention placed on their application in minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS).

Minimally invasive spine surgery is increasingly being evaluated for use in place of traditional open procedures to address a variety of surgical spine procedures [3]. Decreased intraoperative blood loss, decreased hospital stay, better soft tissue handling, and improved postoperative pain scores have all been reported benefits of MIS compared to traditional open surgery [4, 5] [6]. As a result, new techniques for its implementation continue to be developed, including the incorporation of robotics.

Increasingly, there has been a focus on combining the technologies of MIS and robotic guidance in an effort to improve the efficiency and outcomes associated with spine surgery. While there is excitement surrounding its integration, the volume of literature defining the foundation on which to support its application is still in its infancy, though it is beginning to grow [3]. The purpose of this manuscript is to summarize and highlight the reported benefits, potential drawbacks, and future direction for robotics in MIS as it has been reported in recent literature.

Definition

Robotic surgery is a heterogeneous collection of techniques with varying levels of control being exerted on surgical instrumentation by both the robot and the surgeon. There are three broad categories of surgical robots; supervisory-controlled, tele-surgical, and shared control [7, 8]. These systems all use preoperative imaging extensively to plan the procedure in three dimensions but differ in their level of intraoperative instrumentation control by the operating surgeon.

Supervisory-controlled robotic surgery is systems in which the surgeon plans the operation with specific motions and supervises an autonomous robot performing the operative procedure. A commercially available supervisory-controlled robotic system is the TSolution One® system (Think Surgical, Inc.; Freemont, California, USA) for total joint replacement. Tele-surgical robotic surgery, like the DaVinci® system (Intuitive Surgical; Sunnyvale, California, USA), utilizes a hand-held control, operated by the surgeon, which performs surgery via instruments being held by the robot. Shared control, or robotic guidance, uses shared instrument control, with robotic guidance of surgeon-operated instruments [8]. Robotic navigation utilizes pre- or intraoperative imaging and instruments that register real time in space without robotic control over instrumentation; these systems are not the focus of this review.

There are several FDA-approved systems currently in use for robotic spine MIS. The ROSA® (Medtech, Zimmer Biomet; Warsaw, Indiana, USA) and the MAZOR® (Medtronic; Dublin, Ireland) are the two most researched robotic systems for spine surgery. Despite differences in their application, both rely on versions of shared control for their robotic application. Another system Excelsius® is also FDA-approved; however, to date, there have been no published studies involving this system. Coupling preoperative and/or intraoperative CT with radiographic imaging, robotic guidance is thought to enable the surgeon-robot combination to use percutaneous techniques with greater assurance of spatial precision in three dimensions at any specific point in time.

Pedicle Screw Insertion—Accuracy

The most lauded aspect of robot-guided MIS (RMIS) has been the improved accuracy of pedicle screw insertion. In spinal fusion, accurate pedicle screw insertion is of the critical to avoid neurovascular injury and to provide biomechanical support to the fusion construct. The most common classification system is the Gertzbein Robbins (GR) classification [9] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gertzbein Robbins pedicle screw grading—grades A and B are typically considered clinically acceptable without the need for intraoperative revision

| Gertzbein Robbins pedicle screw grading | ||

|---|---|---|

| Grade | Relationship of pedicle and pedicle screw | |

| A | Within pedicle | Clinically acceptable |

| B | Encroachment of pedicle wall by < 2 mm | |

| C | 2-4 mm pedicle wall breach | |

| D | 4-6 mm pedicle wall breach | |

| E | > 6 mm pedicle wall breach | |

The findings among peer-reviewed literature evaluating the accuracy of screw positioning by RMIS tend to favor this technique over freehand open (FO) pedicle screw insertion. Despite great heterogeneity in their sample, a recent meta-analysis of 10 manuscripts evaluating the accuracy of pedicle screws placement with robotic guidance versus freehand showed a significant increase in accuracy when using RMIS (p < 0.1) [10]. As high as 98% of pedicle screws (477/487) in 112 patients that were placed with RMIS were graded as GR grade A or B on postoperative CT [11]. Compared to freehand MIS, accuracy rates of RMIS pedicle screw insertion were similar with 93.4% of RMIS screws deemed clinically acceptable GR grade A or B versus 88.9% of freehand MIS [12]. Additionally, the largest patient volume retrospective review with 890 pedicle screws in 190 patients showed significantly more accurate pedicle screw placement with the use of robotic guidance in MIS versus traditional open freehand (n = 176 screws versus 346 screws; 94.32% versus 78.03%; p < 0.001) [13] (Fig. 1).

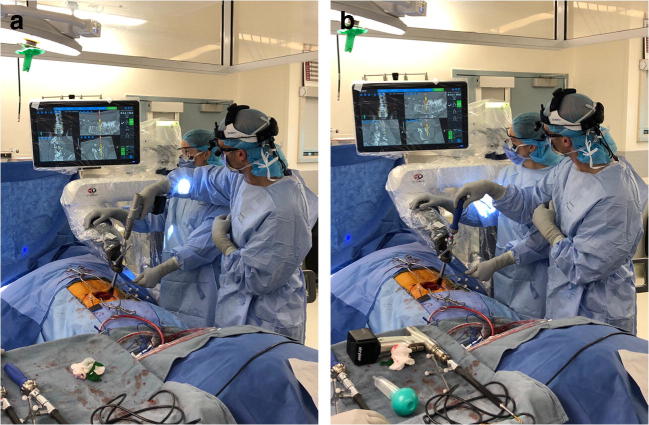

Fig. 1.

Pedicle screw insertion with robotic guidance. Positioning noted on display in real-time three-dimensional orientation. Through preoperative CT, and intraoperative localization, pedicle screw accuracy can be observed throughout pedicle preparation and pedicle screw insertion. a Pedicle screw preparation. b Pedicle screw insertion

In one recent prospective randomized control trial of 78 patients with 166 pedicle screws, there were no differences in the Gertzbein Robbins classification; however, there were 13/82 open freehand screws that violated the proximal facet joint versus 0/74 screws placed with robotic MIS (p < 0.001) [14]. Another prospective randomized controlled trial reported a significantly shorter screw to facet distance in open fluoroscopy-guided pedicle screw insertion compared to RMIS (4.6 mm versus 5.8 mm; p < 0.001) [15].

Conversely, there are several studies that do not show a clear superiority of RMIS and actually report improved accuracy with FO. A recently published systematic review using 8 studies with 2379 pedicle screws showed no difference in RMIS pedicle screw placement compared to FO pedicle screw insertion (FO) (95.3% versus 92.7%; OR 1.47; 95% CI 0.37–5.86; p = 0.59) [16].

The article most critical of RMIS, authored by Ringle et al., reported that 93% of the screws in FO were GR grade A or B, that is, good screw positions, whereas significantly less good screw positions were achieved in RMIS (85%) (p = 0.019). Inversely, the proportion of suboptimal screw positions (groups C + D + E) was significantly larger in RMIS compared with FO, 15% and 7%, respectively. Furthermore, 10 screws of RMIS in 7 patients required a conversion to a FO approach after the robot-guided drill hole was in the soft tissue lateral to the vertebral body and pedicle without sufficient bone contact. One misplaced group E screw of FO was revised in a second procedure because the patient had radicular pain from the misplaced screw. These reported measurements must be taken in context though as this author group reported and publicized difficulty with their three-dimensional localization set up [17].

Imaging Time

Radiation exposure to the surgeon and operating room staff during a spine procedure is a justified concern with MIS. Compared to FO, a major benefit of RMIS with good consensus through the literature is the reduced time and levels of exposure to radiation during RMIS surgery.

A recent prospective randomized controlled trial reported significantly longer fluoroscopy use for FO versus RMIS pedicle screw insertion (p = 0.015), with decreasing use of fluoroscopy among RMIS patients after the first 15 cases evaluated [15]. In another study, shorter fluoroscopy time was used per screw with RMIS (4.02 s) as compared to intraoperative CT navigation (6.36 s; p < 0.001) or FO (8.89 s; p < 0.001) but significantly longer compared to standard robotic CT navigation (1.29; p < 0.001) [13]. Kim et al. did not compare their robot MIS cohort directly to their freehand cohort but interestingly showed a substantial (30%) decrease in fluoroscopy duration between their first 8 (“early”) cases and their “late” cases (subsequent 29 cases) (27.5 min versus 18.45 min; p < 0.001) [18].

It should not be overlooked that patient radiation exposure includes preoperative CT for RMIS procedures. While there is no increased radiation to the operating room staff, this is not insignificant compared to standard radiography and MRI usually conducted prior to most traditional FO cases.

Operative Time

Across the literature, there does not seem to be a difference in the length of surgery between FO and RMIS. There was no difference in overall surgical time of robotic MIS versus CT navigation, intraoperative CT navigation, and traditional open freehand, though robotic-guided MIS did trend towards a significantly longer operative time versus those other modalities [13]. One recent prospective randomized controlled trial showed identical operative time between RMIS and FO fluoroscopy-guided operative times in matched cohorts undergoing posterior lumbosacral decompression and fusion (208.5 min) [15].

Three studies included in systematic review reported robotic-assisted operative time which was significantly longer than freehand pedicle insertion with an average time difference on 39.63 min per case (p = 0.02); however, this study was not specific to MIS robot use [14]. In a randomized controlled trial with 78 patients and 166 pedicle screws, RMIS was significantly longer operative time (220 min versus 190 min; p = 0.009) [14], but in another study, robotic MIS cases were reported to save 3.4 min per level [19]. Another study evaluated the surgical time for the instrumentation, that is, overall time without the time for decompression, and reported significantly shorter time for instrumentation with FO compared to RMIS, 84 min versus 95 min (p = 0.04), respectively [17].

Clinical Outcomes

Revision Rate

Accurate screw placement, which has been suggested to the major benefit of RMIS, should theoretically decrease the incidence of screw revision rates; however, this has not yet been borne out by the literature. This may be a result of neuromonitoring contributing to intraoperative positional screw adjustments and screw retention once appropriately positioned. An alternative explanation is that revision surgery for malpositioned pedicle screws is similar in its invasiveness and danger to primary spine fusion, and thus rarely undertaken without symptomatic cause or extreme concern for potential harm. A large retrospective study, of 1857 screws in 359 patients, including elective, tumor, trauma, and infection cases, reported an overall revision rate of 1.7% (0.48% of screws placed) for malpositioned screws [20]. Compared to RMIS, open-pedicle screw insertion has been reported to have equal incidence of revision surgery for hardware-related issues [15]. A retrospective review of 72 patients treated with robotic MIS pedicle screw placement and postoperative follow up of at least 1 year had no revision surgeries or implant-related complications [21]. Of note, one meta-analysis of revision following pedicle screw placement robot-guided MIS was reported to have significantly lower revision rates as compared to CT navigation MIS (p < 0.001), though notably not compared to freehand pedicle screw insertion (p = 0.36) [21].

Blood Loss

Blood loss and postoperative stay are improved with MIS utilization in spine surgery [12]. Incorporation of robotic guidance does not change these benefits of MIS. At this point in time, there is no literature to evaluate postoperative outcomes in MIS vs RMIS. Among 190 patients retrospectively reviewed, blood loss with RMIS (362 mL) was significantly less than patients receiving robotic navigation (554 mL; p = 0.001), intraoperative CT navigation (528 mL; p < 0.001), or open freehand pedicle screw placement (557 mL; p < 0.001) [13].

Postoperative Recovery

Compared to RO pedicle screw placement, RMIS has repeatedly been reported to result in a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay; 6.3 days versus 8.9 days (p < 0.001) [13] and 6.8 versus 9.4 days in another prospective randomized controlled trial (p = 0.02) [15]. Interestingly, one study looked at time to ambulation among 78 patients involved in a prospective randomized controlled trial and noted no difference in time to ambulation [14]. It is unclear if time to ambulation was part of a postoperative protocol being followed or if patients decided when they would ambulate. Likely, hospital stay was dictated in part by pain control and incisional healing or drain output, variables reportedly improved by MIS.

Outcome Scores

Despite the many reported benefits of RMIS, patient-reported outcomes have not been shown to be improved by RMIS compared to more traditional methods of spine fusion with FO. One prospective randomized controlled trial reported no significant differences in patient-reported pain and functionality outcomes between RMIS and traditional open-pedicle screw insertion techniques at final follow up [15]. Among retrospective reviews, patients reported no difference in back visual analog score (VAS), leg VAS, and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores at 12 months [22] and at 24 months [23], but both showed significant improvement from baseline, preoperative scores.

Complications

Overall complications related to RMIS are infrequently reported on in the literature. One retrospective review reported that compared to robotic navigation, intraoperative CT navigation, FO, and RMIS had significantly fewer complications and had no return to OR for wound breakdown; however, no significant differences were noted between RMIS and FO or CT navigation [13]. Another report, comprised of MIS studies but not specifically robotic-guided MIS, systematically reviewed 5 studies with 457 patients which suggested no difference in complication rate between robot-assisted spine surgery and traditional freehand pedicle screw insertion (1.33% versus 3.45% OR: 0.46; 95% CI 0.15–1.43; p = 0.18) [16]. It is difficult to interpret reported complications as they are scarcely and heterogeneously reported for MIS at this point in time. Additionally, it is likely that as surgeon familiarity with RMIS systems continue to develop, the rates of complications will fall in comparison to other more traditional and familiar techniques.

System Failures

System failures are poorly tolerated and can have a negative impact on accuracy of pedicle screw insertion. While MIS offers some distinct advantages over traditional open approaches, soft tissue can make appropriate trajectory more difficult to achieve and visualization is sacrificed with the belief that fluoroscopy or robotic systems will accurately guide instrumentation. There has to be trust that the navigation and guidance systems themselves will not fail, with the risk of detriment to the patient. Ringel et al. noted poor accuracy of pedicle screw insertion with the use of robotics as a result of a “bed mount” [17]. The bed mount relies on two spatial platforms for robot-patient spatial relationship; a caudal bed mount, and a single point of patient contact with a solitary cranial spinous process k-wire. Small adjustments within the system, relying on a single k-wire point of patient contact, are thought to disrupt the localization of the robotic system and have largely been abandoned in part as a result of the publicity by Ringel et al.

Skidding or skiving of the cannula is another possible system failure, which can alter the starting point and trajectory of pedicle screws during insertion [24]. With degenerative changes, facet hypertrophy can impact the topography of the pedicle screw starting point, making a steeper surface, with risk for lateralization of the starting point. The most common method to address this change in morphology is the use of Peteron instrumentation to flatten the bony site of pedicle screw insertion [18].

Failure of system registration has been reported as a result of elevated body mass, reflected by BMI > 35 and by severe osteopenia [20]. Several other studies refer to multiple deviations from planned robotic-guided MIS for reasons not described, and although these are occurrences in the literature, this emphasizes the fallibility of the robotic systems at this point in time [11, 24, 25].

The Learning Curve

With the incorporation of any new surgical technique or technology, there is a period of use before mastery can be achieved, coined “the learning curve”. It appears that during the learning curve period, acceptable pedicle screw positioning can be achieved. Using a cumulative summation test, Kim reported adequate accuracy and quality control for the first 20 patients reviving robotic MIS pedicle screw placement [18].

After surgeons have passed this period of time, most metrics indicate rapid progression in terms of speed and decreased use of supplementary resources. Hu and Lieberman reported on their first 150 cases using RMIS. With experience using their robotic guidance, the authors reported an improvement in the success of screw placement, a decrease in the percent of screws that were converted to purely manual insertion, and a decrease in the percent of malpositioned screws [25]. In another prospective randomized controlled trial, evaluating the first 30 patients treated with RMIS showed a significant decrease in time per screw insertion (5.5 min versus 4.0 min; p = 0.23) and trend towards significance with fluoroscopy use per screw (4.1 s versus 2.9 s; p = 0.117) [15]. The improved efficiency with use was also noted for surgeons in training. Although no significance was reached, a retrospective review of neurosurgery resident and fellow use of RMIS showed a trend towards improved efficiency with increased use [24].

Tumor, Infection, Deformity

A small volume of recent literature has focused specifically on RMIS in the clinical setting of infection, tumor, and anatomic abnormalities. The potential benefit of robot utilization is notable in cases of unusual physiologic or anatomic considerations.

Retrospective review of 662 pedicle screws placed in 50 patients undergoing RMIS posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) demonstrated significantly lower rates of screw malpositioning compared to prior studies and improved accuracy when preoperative CT was performed in the prone position, more closely mimicking the intraoperative positioning. Of 662 screws placed, 7.2% had cortical breach of > 2 mm; however, in patients that received preoperative CT in the prone position, only 2.4% of screws implanted had cortical breach > 2 mm [26].

A retrospective matched cohort study including 70 patients with metastatic spine disease had 406 screws placed at various levels through the thoracic and lumbosacral spine reflected only a significant difference in the intensity of radiation among the robotic MIS cohort (2.8 mAs versus 2.0 mAs; p < 0.01). There were no difference in accuracy (acceptable grade of A or B 84.4% versus 83.6%; p = 0.89), duration of surgery (226.1 versus 264.1; p = 0.13), surgical site infection (14.3% versus 22.9%; p = 0.54), or radiation exposure (138.2 s versus 126.5 s; p = 0.61) between the robotic MIS and the open freehand cohorts [27].

Infection or post infectious degeneration pose unique challenges of wound healing and potential for wound revisions. With minimally invasive tissue handing and less implant contact with inoculated anatomy, there is potential for lower rates of infectious complications and wound healing issues. A retrospective review of 90 patients treated for spondylodiscitis with posterior spinal fusion (24 open fluoroscopy guided, 66 RMIS) reported greater accuracy with RMIS (90% versus 73.5%, screw entirely within pedicle; p < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference when screw position was evaluated to allow for abutment of the screw with the cortex of the pedicle (p = 0.205). Robotic-guided MIS pedicle screws had lower rates of misplaced screw revision (0.58% versus 4.95%; p = 0.024) and RMIS patients had less intraoperative fluoroscopy (0.40 min/screw versus 0.94 min/screw; p < 0.001) as well as shorter postoperative stay (18.1 days versus 13.8 days; p = 0.012) [28]. Another retrospective review of 206 patients receiving posterior spinal fusion (98 RMIS: 98 patients, open-pedicle screw insertion 108) for spondylodiscitis reported a significantly lower rate of revision for wound breakdown among RMIS cohort after multivariate analysis (p = 0.035) [29].

Two studies help to summarize the benefits of RMIS among patients with less predictable anatomy. In a retrospective review of 1857 implanted screws, 96.9% of screws were considered well positioned; however, higher rates of screw deviation were noted among cases for tumor, infection, and osteoporotic fractures (5.5%, 5.1%, and 4.5% of screws placed, respectively) [20]. Accurate screw positioning was noted in 92% of 148 pedicle screws placed (72 with RMIS) as reported by one retrospective review including RMIS pedicle screw insertion in cases including vertebral body fractures and vertebral body destruction as a result of spondylodiscitis or tumor [30].

Need to Compare Robotics in MIS to MIS

While there is a growing body of scientific literature that is evaluating robotics in MIS, to the best of our knowledge, the literature to date has failed to directly compare robotics in MIS to MIS sans robot. The robot likely has decreased fluoroscopy time compared to traditional MIS; however, this would need to be properly evaluated with direct comparison in an appropriately designed study.

Conclusion

The installation of robotics in MIS has been reported to have excellent pedicle screw insertion accuracy and may be superior to open freehand methods, as many studies suggest. It has also been reported that the combination of robotics and MIS reduces the use of intraoperative fluoroscopy and length of hospital stay. There are probably certain clinical scenarios, such as tumor infection and deformity cases, where robotic systems have a more profound advantage for MIS; however, further investigation is needed to fully explore the benefits in application of robotic guidance for MIS procedures.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Justin Stull and John Mangan declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Gregory Schroeder has the following disclosures: Advance Medical: Paid consultant AOSpine: Other financial or material support Medtronic: Other financial or material support Medtronic Sofamor Danek: Research support Stryker: Paid consultant Wolters Kluwer Health - Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Editorial or governing board Zimmer: Paid consultant.

Alex Vaccaro has the following disclosures: Advanced Spinal Intellectual Properties: Stock or stock Options Aesculap: IP royalties Atlas Spine: IP royalties; Paid consultant Avaz Surgical: Stock or stock Options Bonovo Orthopedics: Stock or stock Options Clinical Spine Surgery: Editorial or governing board Computational Biodynamics: Stock or stock Options Cytonics: Stock or stock Options DePuy, a Johnson & Johnson Company: Paid consultant Dimension Orthotics LLC: Stock or stock Options Electrocore: Stock or stock Options Elsevier: Publishing royalties, financial or material support Flagship Surgical: Stock or stock Options FlowPharma: Stock or stock Options Franklin Bioscience: Stock or stock Options Gamma Spine: Stock or stock Options Gerson Lehrman Group: Paid consultant Globus Medical: IP royalties; Paid consultant; Stock or stock Options Guidepoint Global: Paid consultant Innovative Surgical Design: Paid consultant; Stock or stock Options Insight Therapeutics: Stock or stock Options Jaypee: Publishing royalties, financial or material support Medtronic: IP royalties; Paid consultant none: Other financial or material support Nuvasive: Paid consultant; Stock or stock Options Orthobullets: Paid consultant Paradigm Spine: Stock or stock Options Parvizi Surgical Innovations: Stock or stock Options Prime Surgeons: Stock or stock Options Progressive Spinal Technologies: Stock or stock Options Replication Medica: Stock or stock Options Spine Journal: Editorial or governing board Spine Medica: Stock or stock Options SpineWave: IP royalties; Paid consultant Spinology: Stock or stock Options Stout Medical: Paid consultant; Stock or stock Options Stryker: IP royalties; Paid consultant Taylor Franics/Hodder & Stoughton: Publishing royalties, financial or material support Thieme: Publishing royalties, financial or material support Vertiflex: Stock or stock Options.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Justin D. Stull, Email: Justin.stull@gmail.com, Email: Justin.stull@jefferson.edu

John J. Mangan, Email: Johnmangan3@gmail.com

Alexander R. Vaccaro, Email: alex.vaccaro@rothmaninstitute.com

Gregory D. Schroeder, Email: gregdschroeder@gmail.com

References

- 1.Pilecki MA, McGuire BB, Jain U, Kim JYS, Nadler RB. National multi-institutional comparison of 30-day postoperative complication and readmission rates between open Retropubic radical prostatectomy and robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy using NSQIP. J Endourol. 2014;28(4):430–436. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg H. Robotic surgery: growing sales, but growing concerns [internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/id/100564517. Accessed 22 Dec 2018.

- 3.Fan G, Han R, Zhang H, He S, Chen Z. Worldwide research productivity in the field of minimally invasive spine surgery: a 20-year survey of publication activities. Spine. 2017;42(22):1717–22. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu VM, Kerezoudis P, Gilder HE, McCutcheon BA, Phan K, Bydon M. Minimally invasive surgery versus open surgery spinal fusion for spondylolisthesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine. 2017;42(3):E177–E185. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein CL, Macwan K, Sundararajan K, Rampersaud YR. Comparative outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for posterior lumbar fusion: a systematic review. Clin Orthop. 2014;472(6):1727–1737. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3465-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu M-H, Dubey NK, Li Y-Y, Lee C-Y, Cheng C-C, Shi C-S, Huang TJ. Comparison of minimally invasive spine surgery using intraoperative computed tomography integrated navigation, fluoroscopy, and conventional open surgery for lumbar spondylolisthesis: a prospective registry-based cohort study. Spine J. 2017;17(8):1082–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overley SC, Cho SK, Mehta AI, Arnold PM. Navigation and robotics in spinal surgery: where are we now? Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3S):S86–S99. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathoo N, Cavuşoğlu MC, Vogelbaum MA, Barnett GH. In touch with robotics: neurosurgery for the future. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(3):421–433. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000153929.68024.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertzbein SD, Robbins SE. Accuracy of pedicular screw placement in vivo. Spine. 1990;15(1):11–14. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Y, Du JP, Liu JJ, Zhang JN, Qiao HH, Liu SC, et al. Accuracy of pedicle screw placement comparing robot-assisted technology and the free-hand with fluoroscopy-guided method in spine surgery: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(22):e10970. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijk JD, van den Ende RPJ, Stramigioli S, Köchling M, Höss N. Clinical pedicle screw accuracy and deviation from planning in robot-guided spine surgery: robot-guided pedicle screw accuracy. Spine. 2015;40(17):E986–E991. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molliqaj G, Schatlo B, Alaid A, Solomiichuk V, Rohde V, Schaller K, Tessitore E. Accuracy of robot-guided versus freehand fluoroscopy-assisted pedicle screw insertion in thoracolumbar spinal surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E14. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.FOCUS179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Y, Du J, Zhang J, Liu S, Xue X, Huang Y, et al. Comparison of accuracy of pedicle screw insertion among 4 guided technologies in spine surgery. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:5960–5968. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H-J, Jung W-I, Chang B-S, Lee C-K, Kang K-T, Yeom JS. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of robot-assisted vs freehand pedicle screw fixation in spine surgery. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hyun S-J, Kim K-J, Jahng T-A, Kim H-J. Minimally invasive robotic versus open fluoroscopic-guided spinal instrumented fusions: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2017;42(6):353–358. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Chen X, Margalit A, Peng H, Qiu G, Qian W. Robot-assisted vs freehand pedicle screw fixation in spine surgery - a systematic review and a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int J Med Robot. 2018;14(3):e1892. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ringel F, Stüer C, Reinke A, Preuss A, Behr M, Auer F, Stoffel M, Meyer B. Accuracy of robot-assisted placement of lumbar and sacral pedicle screws: a prospective randomized comparison to conventional freehand screw implantation. Spine. 2012;37(8):E496–E501. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31824b7767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H-J, Lee SH, Chang B-S, Lee C-K, Lim TO. Hoo LP, et al. Monitoring the quality of robot-assisted pedicle screw fixation in the lumbar spine by using a cumulative summation test. Spine. 2015;40(2):87–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menger RP, Savardekar AR, Farokhi F, Sin A. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the integration of robotic spine technology in spine surgery. Neurospine. 2018;15(3):216–224. doi: 10.14245/ns.1836082.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keric N, Doenitz C, Haj A, Rachwal-Czyzewicz I, Renovanz M, Wesp DMA, Boor S, Conrad J, Brawanski A, Giese A, Kantelhardt SR. Evaluation of robot-guided minimally invasive implantation of 2067 pedicle screws. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E11. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.FOCUS16552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schröder ML, Staartjes VE. Revisions for screw malposition and clinical outcomes after robot-guided lumbar fusion for spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E12. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.FOCUS16534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H-J, Kang K-T, Chun H-J, Hwang JS, Chang B-S, Lee C-K, Yeom JS. Comparative study of 1-year clinical and radiological outcomes using robot-assisted pedicle screw fixation and freehand technique in posterior lumbar interbody fusion: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Int J Med Robot. 2018;14(4):e1917. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SM, Kim HJ, Lee SY, Chang BS, Lee CK, Yeom JS. Radiographic and clinical outcomes of robot-assisted posterior pedicle screw fixation: two-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Yonsei Med J. 2018;59(3):438–444. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.3.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urakov TM, Chang KH-K, Burks SS, Wang MY. Initial academic experience and learning curve with robotic spine instrumentation. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E4. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.FOCUS175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu X, Lieberman IH. What is the learning curve for robotic-assisted pedicle screw placement in spine surgery? Clin Orthop. 2014;472(6):1839–1844. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3291-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macke JJ, Woo R, Varich L. Accuracy of robot-assisted pedicle screw placement for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in the pediatric population. J Robot Surg. 2016;10(2):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s11701-016-0587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solomiichuk V, Fleischhammer J, Molliqaj G, Warda J, Alaid A, von Eckardstein K, Schaller K, Tessitore E, Rohde V, Schatlo B. Robotic versus fluoroscopy-guided pedicle screw insertion for metastatic spinal disease: a matched-cohort comparison. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E13. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.FOCUS1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keric N, Eum DJ, Afghanyar F, Rachwal-Czyzewicz I, Renovanz M, Conrad J, Wesp DMA, Kantelhardt SR, Giese A. Evaluation of surgical strategy of conventional vs. percutaneous robot-assisted spinal trans-pedicular instrumentation in spondylodiscitis. J Robot Surg. 2017;11(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/s11701-016-0597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alaid A, von Eckardstein K, Smoll NR, Solomiichuk V, Rohde V, Martinez R, Schatlo B. Robot guidance for percutaneous minimally invasive placement of pedicle screws for pyogenic spondylodiscitis is associated with lower rates of wound breakdown compared to conventional fluoroscopy-guided instrumentation. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;41(2):489–496. doi: 10.1007/s10143-017-0877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roser F, Tatagiba M, Maier G. Spinal robotics: current applications and future perspectives. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 1):12–18. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318270d02c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]