Abstract

Background

The published literature demands examples of health‐care systems designed with the active engagement of patients to explore the application of this complex phenomenon in practice.

Methods

This case study explored how the voice of patients was incorporated into the process of redesigning an element of the health‐care system, a centralized system for intake of referrals from primary care to rheumatologists for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis (RA)—centralized intake. The phenomenon of patient engagement using “patient and community engagement researchers” (PaCERs) in research and the process of redesigning centralized intake were selected as the case. In‐depth evaluation of the case was undertaken through the triangulation of findings from the document review and participants’ reflection on the case.

Results

In this case, patients and PaCERs participated in multiple activities including an initial meeting of key stakeholders to develop the project vision; a patient‐to‐patient PaCERs study to gather perspectives of patients with RA on the challenges they face in accessing and navigating the health‐care system, and what they see as key elements of an effective system that would be responsive to their needs; the development of an evaluation framework for future centralized intake; and the choice of candidate centralized intake strategies to be evaluated.

Conclusions

The described feasible multistep approach to active patient engagement in health‐care system redesign contributes to an understanding of the application of this complex phenomenon in practice. Therefore, the manuscript serves as one more step towards a patient‐centred health‐care system that is redesigned with active patient engagement.

Keywords: health system redesign, patient engagement in research and system redesign, patient needs, patient‐centred care, patient‐to‐patient research

1. INTRODUCTION

During the last decades, health‐care organizations around the world have been actively advocating for patient‐centred care as means of ensuring high‐quality care.1, 2, 3, 4 Patient‐centred care calls for a more holistic approach to care delivery that is focused on patients’ needs and experiences of well‐being and illness from a multidimensional biopsychosocial perspective.5, 6, 7, 8 To achieve patient‐centred care, fundamental changes, including a redesign of existing systems and/or design of new ones, are required.9

Integrating patients (ie, patient involvement10) into research and system design has been recognized as important elements in achieving patient‐centred care.11 Patient involvement offers the potential to target research and system design to patients’ needs, thus improving the patient experience with care and quality of care, and potentially reduce costs of care.12, 13, 14 Despite decades of discussions about the importance and potential benefits of patient involvement in health planning, research and system design, to date, patient involvement in designing and redesigning health‐care systems has often been limited to passive involvement.10, 15, 16 Few examples where patients and other stakeholders have been actively engaged as partners to design and redesign the system are available in the literature.12, 17 Therefore, more examples of active engagement of patients and other stakeholders in the system redesign are needed to explore the application of this complex phenomenon in practice.10, 15, 16, 18

This manuscript reports on a case study of patient involvement in redesigning a centralized system for intake of referrals from primary care to rheumatologists for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis (RA), hereafter referred to as centralized intake (CI).

2. METHODS

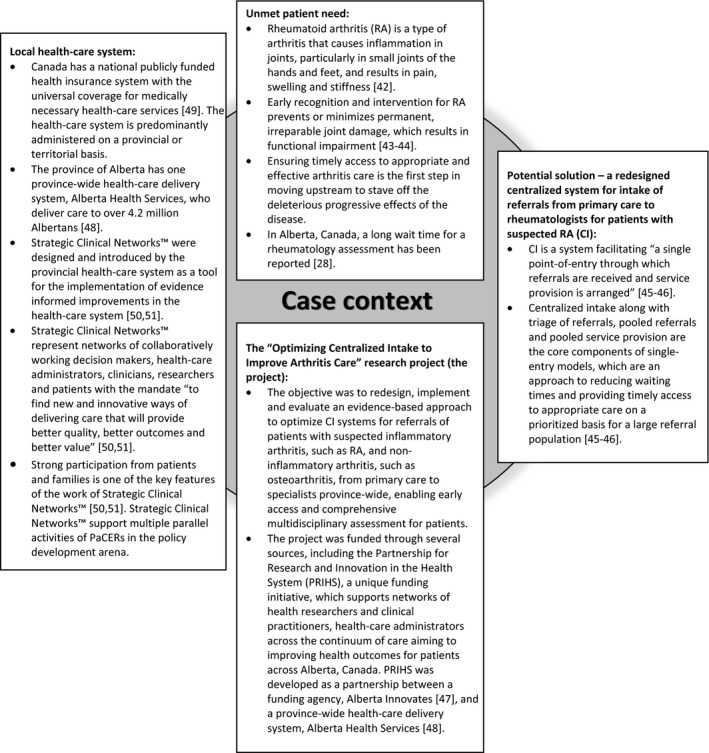

The study followed the case study design approach as described by Yin.19 In this study, the phenomenon of patient engagement using “patient and community engagement researchers” (PaCERs) in research and the process of redesigning CI were selected as the case.19 PaCERs are citizens living with various health conditions who received formal research training that includes how to design research, engage other patients and conduct research projects using an established protocol of qualitative inquiry.20, 21, 22 The case took place within the unique context of a 2‐year‐long research project, which aimed at “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care,” hereafter referred as the project (Figure 1). The case study aimed to explore how the voice of patients was incorporated into the process of redesigning an element of the health‐care system, CI, within the project. The case study research team consisted of multiple stakeholders (PaCERs, academic researchers, health‐care professionals and health‐care administrators), who were engaged in the project. The study was driven by two predefined theoretical propositions19: (a) health‐care systems should be responsive to patients’ needs,2 and (b) active patient engagement (ie, patient involvement10) in system design and redesign is required to build a system that is responsive to patient needs.11 A detailed reporting on each activity within the project (eg, objectives, participants, actions, decisions and results) was undertaken by the project manager (JP) and academic researcher leading the project (DAM) to facilitate the case study. All documents that reported on the case and the context of the case were reviewed by the project manager (JP) and two academic researchers (DAM, EL) with expertise in qualitative and mixed‐methods research to extract data on objectives of patient and PaCERs engagement in redesigning CI, roles of patients and PaCERs in the project, and outcomes of their engagement. An inductive narrative analysis of the extracted data was conducted by three academic researchers (DAM, EL, NM) with expertise in qualitative and mixed‐methods research and two PaCERs (JLM, SRT) to summarize the in‐depth description of the case and preliminary findings of the case study.19, 23 Next, other members of the team reflected on the preliminary findings and refined them from the perspective of their personal experience with participating in the project and observation of the case. Lastly, preliminary findings from the document review and the team's reflection were triangulated through team discussions to generate the final findings.

Figure 1.

Environment and context for the case of patient and PaCERs engagement in the “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care” project. Sources: Badley,42 Goekoop‐Ruiterman et al,43 Pope et al,44 Hazlewood et al,28 Damani et al,45 Lopatina et al,46 Alberta Innovates,47 Alberta Health Services,48 Government of Canada,49 Alberta Health Services50 and Noseworthy et al51

The research was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID number REB13‐0822).

3. RESULTS

Patient and community engagement researchers were engaged in the project from the outset as equal partners with the rest of the project team members. This involved setting up the research agenda, helping to develop the funding application and applying for funding. During the project execution, patients and PaCERs participated in multiple activities described in detail here below and presented in chronological order.

3.1. First stakeholder meeting

At the beginning of the project execution, the project team engaged key stakeholders (patients and PaCERs [n = 4], health‐care professionals [n = 11], health‐care administrators [n = 15] and academic researchers [n = 8]) for a 1‐day meeting to develop the project vision. The meeting started with a discussion about centralized systems for intake of referrals as a construct, including a set of definitions to establish a common language. Subsequently, attendees were engaged in a facilitated discussion of three questions: (a) Can centralized systems for intake of referrals facilitate optimal care for patients living with RA? (b) How can essential services for patients living with RA be integrated in a continuous pathway? (c) How can quality of care be measured in a meaningful manner that the findings can influence patient outcomes and health system efficiency? Throughout the discussion, a scribe took notes. Meeting notes were summarized using thematic analysis by the research team (DAM, JP) to identify common themes. Next, meeting notes and identified themes were circulated to all meeting participants to be checked for consistency and reviewed for comments. Afterwards, the research team (DAM, JP) incorporated participants’ comments and refined the identified themes. Based on those themes, the project vision was framed as a set of principles aimed at developing an optimal CI, which should:

Create a high‐quality experience with the process for patients and providers;

Ensure patients’ timely access to the appropriate care pathway;

Ensure patients engage (and are engaged by) the appropriate care providers with a minimal number of referrals from one specialist to another;

Ensure patients are triaged and referred to appropriate care providers based on “best practice” to achieve desired outcomes;

Ensure resources are optimally used in achieving desired outcomes;

Mitigate risks to avoid unintended or harmful results.

Once established, these targets shaped and guided subsequent project phases. In particular, the patient‐centred nature of the majority of these principles highlighted the demand for further input from patients into the processes of redesign, implementation and evaluation of CI to ensure that the future system is responsive to patients’ needs.

3.2. PaCERs study

Next, PaCERs conducted a study to gather perspectives of patients with RA on the challenges they face in accessing and navigating the health‐care system, and what they see as key elements of an effective system that would be responsive to their needs. Although the focus of this work was on CI, the PaCERs study explored patients’ perspectives on the entire care pathway. This was done to account for the complexity of the health‐care system and possible interactions between the system's elements, as CI is just one element of the care pathway for patients. The study was led by two PaCERs who are patients living with osteoarthritis with previous experience in research on care delivery for patients with musculoskeletal conditions (JLM, SRT) and a research assistant who is a patient living with RA. Participants who self‐identified as having RA were recruited through arthritis networks, posters in rheumatology clinics and rheumatologists’ referrals. Those interested in the study contacted PaCERs, who sent potential participants the study description and a consent form. Next, completed consent forms were sent back to PaCERs. The PaCERs study went through three phases: set, collect and reflect as outlined in the PaCERs methodology.20, 21 Given the iterative nature of the research, patients were recruited and data were collected until data saturation was reached at each phase of the study. Over the three phases, 15 patients were included (Table 1).

Table 1.

Self‐reported characteristics of participants (n = 15) in the patient and community engagement researchers (PaCERs) study

| Characteristic | Number (percentage) of participants |

|---|---|

| Female | 13 (87%) |

| Age groups | |

| Less than 40 y old | 3 (20%) |

| 40‐60 y old | 5 (33%) |

| Over 60 y old | 7 (47%) |

| Living in a large urban centre | 11 (73%) |

| Newly diagnosed RA (approximately a year ago) | 4 (27%) |

3.2.1. Set phase

Patient and community engagement researchers developed a focus group interview guide for the set phase based on the proceedings of the stakeholder meeting. The set focus group took place at neutral grounds for all attendees and lasted about 4 hours. During the set focus group, participants (n = 4) were first asked to talk about their experience being a patient with RA. Then, participants moved into a discussion about their experiences interacting with the health‐care system to manage their RA. The focus group ended with participants giving advice on what to address in the collect interviews. This included such factors as getting diagnosed, accessing a rheumatologist when medications need adjusting, communication between primary care providers and other providers, and maintaining patients’ mental well‐being. Throughout the focus group, participants’ points were documented on flip charts. Subsequently, PaCERs used focus group notes to develop a semistructured interview guide for the collect phase.

3.2.2. Collect phase

In telephone interviews (n = 11), participants were asked about their experience of managing RA and their medications; what or who was most helpful; what other help they could use; and what was key to a system that would be responsive to the needs of patients with RA. Interviews lasted between 1 and 2 hours. Interviews were audiotaped, and notes were taken to document key points. Subsequently, PaCERs independently reviewed notes and the audiotape of each interview for salient points about access and navigating the health‐care system and key elements of a system that would be responsive to the needs of patients with RA and coded them using the grounded theory method and open coding technique.24 PaCERs then compared and contrasted their findings and, using a collaborative, iterative process, identified a preliminary set of themes and subthemes. PaCERs also identified challenges that patients faced when accessing and navigating the system and key elements of a system that patients reported would be responsive to patients’ needs. Next, preliminary findings were compiled and presented for discussion during the reflect focus groups.

3.2.3. Reflect phase

There were three reflect focus groups that included a total of 10 participants: two for participants living in urban areas and one for participants from rural areas. The reflect focus groups took place locations neutral and convenient for all attending (eg, meeting room at a church or community centre) and lasted between 3 and 5 hours. PaCERs presented preliminary findings of the collect interviews. Then, PaCERs asked the focus group participants to reflect on the extent to which each of the identified challenges and key elements of the system that would be responsive to patients’ needs fit with what had previously been discussed during the collect phase. This was followed by a discussion on centralized systems for intake of referrals and the potential role of CI in addressing the key elements of the system that would be responsive to patients’ needs. The points discussed were documented on flip charts. Through a collaborative, iterative process, PaCERs examined the reflect focus group data to refine the preliminary findings and to develop the final findings.24 As a result, five themes were identified: (a) initial access to rheumatology care; (b) on‐going access to rheumatology care; (c) information about RA and resources for those living with RA; (d) fear of the future; and (e) collaborative and continuous care (Table 2). The final set of challenges that patients face when accessing and navigating the system, and key elements of the system that would be responsive to patients’ needs, were mapped to the corresponding themes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes identified through the patient and community engagement researchers (PaCERs) study with the corresponding examples of participants’ experience in accessing and navigating the health‐care system for management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

| Themes | Subthemes | Examples of participants’ experience when accessing and navigating the health‐care system for management of RA |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial access to rheumatology care | Delay in recognition of RA and the referral of patients to rheumatology care team by family doctors |

|

| Long waiting time for initial appointment |

|

|

| Positive experience with the initial access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| Suggestions for improving patients’ experience with the initial access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 2. On‐going access to rheumatology care | Challenges in accessing rheumatologists in case of flare or problems with medications |

|

| Direct contact to rheumatology care team |

|

|

| Suggestions for improving patients’ experience with the on‐going access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 3. Information about RA and resources for those living with RA | Lack of information about RA and resources for those living with RA |

|

| Patients’ education is a professional responsibility of health‐care providers |

|

|

| Positive experience with education sessions for patients with RA |

|

|

| Need for peer support and lack of peer support programs for those living with RA |

|

|

| Suggestions for improving patients’ experience with the access to information about RA and resources for those living with RA |

|

|

| 4. Fear of the future | Fear of unknown |

|

| Biologic drugs |

|

|

| Suggestions for reducing patients fear of the future |

|

|

| 5. Collaborative and continuous care | Lack of collaborative and continuous care |

|

| Suggestions for improving continuity of care |

|

Table 3.

Key elements of the health‐care system that would be responsive to patients’ needs aligned with corresponding themes identified through the patient and community engagement researchers (PaCERs) study

| Themes identified during the PaCERs study | Summary of the issues faced by patients with RA in accessing and navigating the health‐care system | Key elements of the health‐care system that would be responsive to patients’ needs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 2. On‐going access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 3. Information about RA and resources for those living with RA |

|

|

| 4. Fear of the future |

|

|

| 5. Collaborative and continuous care |

|

|

Key elements of a health‐care system that would be responsive to patients’ needs, which participants of the PaCERs study thought could be addressed to some extent through centralized intake.

3.2.4. Interpretation of findings

Findings of the PaCERs study suggest that patient‐centred care for patients with RA should be viewed as a continuum. That continuum starts from the patients’ first point of contact with the health‐care system, carries through their initial appointment with a specialist and continues throughout their long‐term and on‐going follow‐up visits with their rheumatology care team. To be responsive to patients’ needs, the continuum of care should be easy to access and navigate. It should also provide patients easy access to information, education and community resources; as well as incorporate a communication infrastructure to promote collaboration among care providers. Participants reported experiencing multiple challenges when accessing and navigating the system. Among those challenges, initial access and on‐going access to care were raised as the two challenges that were of primary concern to participants.

The main goal of CI, as one element of the care pathway for patients with RA, is to ensure timely initial access to appropriate care. As such, participants found that CI had a potential to vastly improve patients’ experiences with care, as well as their outcomes, and should be considered when redesigning the system to be responsive to the needs of patients. Unfortunately, several participants experienced challenges with the initial access to specialists’ care due to delayed recognition of suspected RA by primary care providers. Therefore, patients recommended that CI should facilitate access to information and resources for primary care providers and patients to improve their knowledge about RA. CI could also play a role in improving communication and collaboration between primary care providers, the rheumatology care team and the patient through electronic communication methods.

Although coordination of on‐going follow‐up is not among the goals for CI, participants suggested that CI could improve the on‐going care by ensuring patients are educated about what to do in case of a flare. Participants also recommended that access to publicly funded nonphysician specialists with RA expertise (eg, advanced practice nurses, physiotherapists and pharmacists), as well as the ability to contact them directly, would improve patient‐centredness of care and could be organized through CI.

Moreover, participants suggested that CI could address challenges to navigating the health‐care system not related to access to care. For example, CI may help patients cope with the unpredictable course of their disease and lack of information about RA by providing patients with education about RA, available peer support and trustworthy online resources as soon as the referral was received and/or diagnosis established.

3.3. Application of the PaCERs study findings in the project

During the next steps of the project, findings of the PaCERs study were used to inform the development of an evaluation framework for CI (key performance indicators [KPIs] for measuring the quality of care and a patient experience survey; Table 4) and the choice of candidate CI strategies (ie, its potential configurations) to be evaluated.

Table 4.

Key performance indicators (KPIs)25 and statements in the patient experience survey aligned with the corresponding themes identified through the patient and community engagement research (PaCERs) study

| Themes identified during the PaCERs study | KPIsa | Statements in the patient experience survey |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 2. On‐going access to rheumatology care |

|

|

| 3. Information about RA and resources for those living with RA |

|

|

| 4. Fear of the future |

|

|

| 5. Collaborative and continuous care |

|

|

The KPIs in the table refer to the numbering in the manuscript describing the process of the development of KPIs.25

3.3.1. KPIs

The set of KPIs (ie, quantifiable measures of quality of care) to evaluate CI was developed through a multistep process described in detail elsewhere.25 Out of the final set of KPIs,25 four KPIs addressed the identified during the PaCERs study theme of “initial access to rheumatology care,” two—the theme of “on‐going access to rheumatology care,” one—the theme of “lack of information about RA and resources for those living with RA,” and another was focused on patient experience with CI in general (Table 3).

The project then used a multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) process26 to develop an aggregate performance measure for CI.27 In the MCDA process, the KPIs identified that aligned with the themes identified during the PaCERs study were found to be of most importance (ie, were ranked higher) by all stakeholders (patients and PaCERs [n = 2], health‐care professionals [n = 10], health‐care administrators [n = 7] and academic researchers [n = 9]).27 The KPI focused on patient experience with CI was ranked as the top KPI.27 As part of the project, KPIs were developed to evaluate the quality of care delivered by an existing centralized intake and triage in rheumatology system in Calgary, Alberta, and to identify the system's gaps.28 Next, KPIs will be used within the implemented province‐wide redesigned CI to measure the impact of the change on quality of care.

3.3.2. Patient experience survey

To address and measure the KPI about patient experience, the team developed a patient experience survey.29 The survey development involved discussions between PaCERs (n = 2) and academic researchers (n = 4) over the course of several meetings. During discussions, researchers built on findings from the previous activities within the project to adapt questions from several validated instruments on patients’ experience (eg Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) patient survey questions,30 satisfaction questionnaire for patients with RA31).29 This process resulted in the selection of a set of 23 questions (Appendix 1). The patient experience survey will be administered to patients with suspected RA referred to rheumatology clinics through the current centralized intake and triage in rheumatology system in Calgary, Alberta.28 These data will be compared to the patients’ experience after the system optimization.

3.3.3. Candidate strategies for CI

A set of candidate strategies for optimization of CI was identified during a 1‐day stakeholder meeting. Participants (patients and PaCERs [n = 2], health‐care professionals [n = 10], health‐care administrators [n = 7] and academic researchers [n = 9]) were presented with the elements of predefined based on the literature and discussions with relevant stakeholders32, 33 candidate strategies for CI. Afterwards, participants reflected on proposed models and provided feedback to develop the preferred model for Alberta. Throughout this discussion, proposed alternative configurations of CI were refined to ensure their alignment with the previously established set of principles for an optimal, CI identified challenges to accessing and navigating the system, and the key elements of the system that would be responsive to patients’ needs. All discussion points were recorded by a scribe. The meeting notes were reviewed and analysed to select the final set of models to be evaluated.

3.4. Future plans

Once the candidate strategies are selected, they will be tested using simulation models34 delineating the operational features and describing the clinical pathway and the flow of patients. Each strategy will be tested for its ability to adjust for variation in the type of treatment needed by patients and the availability of various care providers and facilities to provide the different services to identify the strategy that would be most efficient and effective in directing patients to appropriate care providers, thus achieving improved patient and system outcomes (ie, optimal strategy). Finally, based on the feasibility and readiness of the clinics, there will be an opportunity to implement and evaluate the identified optimal strategy.

4. DISCUSSION

This case study adds information to the scarce body of literature on examples of patient engagement in health‐care system design. In the described case, patient engagement in the redesign of CI was fostered through the continuous engagement of patients in research with the applied focus on optimization of care delivery. The described approach to patient engagement in system redesign has a unique feature, the active engagement of PaCERs, patients trained to design and conduct health research. Throughout the project, PaCERs served as a “bridge” between patients and other stakeholders, ensuring that the patients’ voice was heard and considered during each step of the project. We believe this feature has ensured that patients’ needs and preferences were incorporated into the system redesign rather than being included in a research process as a “token patient.” This case study did not aim to assess the effectiveness of the applied approach to patient engagement in system redesign. Nonetheless, the alignment of the majority of the elements of an evaluation framework for the future CI with the key themes identified during the PaCERs study suggests that the developed framework was indeed patient‐centred. This, in turn, suggests that the applied approach to patient engagement has served as an effective tool for designing a patient‐centred system.

Despite its unique feature, the active engagement of PaCERs, our approach to patient engagement in system redesign correlates with several frameworks for understanding and classifying patient engagement discussed in the literature. For instance, a framework for patient and family engagement in health and health care by Carman et al35 describes engagement activities along a continuum with consultation being at the lower end and partnership and shared leadership representing the higher end of this continuum. The framework also classifies engagement based on the level at which it occurs, including direct care, organizational design and governance, and policymaking.35 According to this framework, our approach covers the higher end of the continuum of engagement within the level of organizational design and governance.35 Next, according to the framework for patient and service user engagement in research,16 our approach includes all components of patient and public involvement in research, such as patient and service user initiation, building reciprocal relationships, colearning process and re‐assessment and feedback, throughout both preparatory, execution and translational phases of the project. Limited feasibility of approaches that cover the higher end of the continuum of patient engagement and/or include all components of patient and public involvement in research has been discussed as a barrier to their application in practice.16, 35 The current manuscript presents an example of a successful application of such an approach.

Our findings should be considered within the context of the single‐case study design and qualitative analysis. First, the discussed approach to the patient engagement in system redesign has emerged from a unique single case, which limits the generalizability of our findings.19 This case study represents one approach to patient engagement in system redesign, which may not fit every question, system settings and clinical area. Nonetheless, the holistic approach of the single‐case study design facilitated an in‐depth description of the case and its context, allowing the reader to make conclusions regarding the feasibility of the approach in the local environment.19 Second, the elements of the system that would be responsive to the needs of patients with RA, as well as the suggestions as to how CI can help to meet those needs, were developed through a qualitative PaCERs study with a relatively homogenous group of patients with RA. To reduce the potential for selection, coding and interpretation biases,36 all steps of the PaCERs study were conducted using sound methodology by trained patient engagement researchers experienced in qualitative research, and data were collected until saturation was reached. All coding, content analysis and interpretation were done by at least two PaCERs, reviewed by the team and finalized when the consensus was achieved. Lastly, although our findings on challenges experienced by patients with RA align with the published literature,28, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 the identified key elements of the system that would be responsive to needs of patients with RA, and suggestions as to how CI can help to meet those needs, might be specific to a universal system with a single public payer as in Alberta, Canada. Therefore, these key elements should be carefully considered within specific local environment.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Overall, this study presents a feasible multistep approach to patient engagement in health‐care system redesign. This manuscript contributes towards the understanding of the complex phenomenon of patient engagement and serves as one more step towards a patient‐centred system that is redesigned with active patient engagement.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest. Elena Lopatina is funded by Mitacs and Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute through Mitacs Accelerate Internship; Deborah Marshall is supported by a Canada Research Chair, Health Systems and Services Research, and the Arthur J.E. Child Chair Rheumatology Outcomes Research.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors meet the authorship criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors: Elena Lopatina, Jean L. Miller, Sylvia R. Teare, Nancy J. Marlett, Jatin Patel, Claire E.H. Barber, Dianne P. Mosher, Tracy Wasylak, Linda J. Woodhouse and Deborah A. Marshall provided substantial contribution to conception and design of the study, as well as analysis and interpretation of data, participated in drafting and revising the article, and provided final approval on the version to be submitted; Deborah Marshall as a corresponding author will act as the overall guarantor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to thank all participants of the patient and community engagement researchers (PaCERs) study and everyone who has been involved in the “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care” project.

Appendix 1. Patient experience survey [1]

1.1.

| Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Health System (PRIHS) grant: Optimizing centralized intake to improve arthritis care for Albertans | ||

|

|

|

Rheumatology Clinic Patient Experience Survey

What is the survey about?

This survey is about your experience as a rheumatology patient in our clinic.

Who should complete the survey?

The survey should be completed by rheumatology patients who receive their care at the University of Calgary rheumatology clinics at either the Richmond Road Diagnostic and Treatment Center or the South Health Campus.

How to complete the survey?

Please select only one answer that shows how much you agree with the following statements.

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not Applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My care started quickly after the referral to the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. The referral from my family doctor to the rheumatology patient clinic was dealt with in a timely manner | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. It was difficult to reach the care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic knew important information about my medical history | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. My family doctor is informed and up‐to‐date about the care I receive at the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. My care was well‐coordinated among different care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. I received consistent messages from all of the different care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic respected my wishes and ideas about my treatment | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. I was as involved as I wanted to be in making decisions about my treatment | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic asked me about my goals for treatment and what is important to me in managing my condition | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 11. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic responded to all my questions or concerns in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic explained the proposed treatment plan to me in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. Before my treatment, all the risks and/or benefits were explained to me in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 14. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic explained the reasons for all the tests in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 15. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic explained my test results to me in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 16. The purpose of the medications that were prescribed were explained to me in a way I could understand | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 17. The information I received about my condition was clear | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 18. I received information on other options to manage my condition (eg, physiotherapy, acupuncture, chiropractor, nonmedical wellness strategies) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 19. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic gave me information on how to self‐manage | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 20. The care providers at the rheumatology patient clinic explained to me what to do if my rheumatoid arthritis gets worse | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 21. The information I received on peer support groups was useful | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 22. Overall, I was treated with respect while I was at the rheumatology patient clinic | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 23. The care providers at the clinic made efforts to understand what having arthritis means to me | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Additional comments | |||||

| __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |||||

Thank you for your participation

Source: Carr et al,29

Lopatina E, Miller JL, Teare SR, et al. The voice of patients in system redesign: A case study of redesigning a centralized system for intake of referrals from primary care to rheumatologists for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis. Health Expect. 2019;22:348–363. 10.1111/hex.12855

Funding information

The “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care” research project, within which the case happened, was funded through: Alberta Innovates, Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Health System (PRIHS) Grant: “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care for Albertans”; The Arthritis Society, Models of Care Catalyst grant: “Creating an optimal model of care for the efficient delivery of appropriate and effective arthritis care”; Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) Planning Grant (funded through Priority Announcement Health Services and Policy Research): “Evidence based planning of an optimal triaging strategy for arthritis care in Alberta”; Alberta Health Services, Research Grant (through the Bone and Joint Health Strategic Clinical Network): “Optimizing Centralized Intake to Improve Arthritis Care for Albertans.”

References

- 1. Patient Focus and Public Involvement. Edinburgh: NHS Scotland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: United States National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Strategy for Patient‐Oriented Research. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html. Accessed December 9, 2016.

- 4. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient‐centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liberati EG, Gorli M, Moja L, Galuppo L, Ripamonti S, Scaratti G. Exploring the practice of patient centered care: the role of ethnography and reflexivity. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:45‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein RM. The science of patient‐centered care. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):805‐810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras M‐E. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient‐centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):155‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, Zelinsky S, Quan H, Lu M. How to practice person‐centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2017;21:429‐440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forbat L, Cayless S, Knighting K, Cornwell J, Kearney N. Engaging patients in health care: an empirical study of the role of engagement on attitudes and action. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(1):84‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moore JE, Titler MG, Low LK, Dalton VK, Sampselle CM. Transforming patient‐centered care: development of the evidence informed decision making through engagement model. Women's Health Issues. 2015;25(3):276‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Souza S, Galloway J, Simpson C, et al. Patient involvement in rheumatology outpatient service design and delivery: a case study. Health Expect. 2017;20(3):508‐518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient‐centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores’. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):216‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tritter J, Daykin N, Evans S, Sanidas M. Improving Cancer Services Through Patient Involvement. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151‐1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cooper K, Gillmore C, Hogg L. Experience‐based co‐design in an adult psychological therapies service. J Ment Health. 2016;25(1):36‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Menichetti J, Libreri C, Lozza E, Graffigna G. Giving patients a starring role in their own care: a bibliometric analysis of the ongoing literature debate. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):516‐526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marlett N, Shklarov S, Marshall D, Santana MJ, Wasylak T. Building new roles and relationships in research: a model of patient engagement research. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1057‐1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marlett N, Emes C. Grey Matters: A Guide to Collaborative Research With Seniors. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shklarov S, Marshall DA, Wasylak T, Marlett NJ. “Part of the Team”: mapping the outcomes of training patients for new roles in health research and planning. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1428‐1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J. 2007;50(1):25‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glaser B. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barber CE, Patel JN, Woodhouse L, et al. Development of key performance indicators to evaluate centralized intake for patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thokala P, Devlin N, Marsh K, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—an introduction: report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(1):1‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marshall DA. Developing an aggregate performance measure for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis centralized intake system’ key performance indicators. 2017. (in preparation).

- 28. Hazlewood GS, Barr SG, Lopatina E, et al. Improving appropriate access to care with central referral and triage in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(10):1547‐1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carr EC, Ortiz M, Patel J, Miller JL, Teare SR, Marshall DA. Meaningful patient engagement and the process of co‐designing a patient experience survey tool for people with arthritis referred to a central intake clinic. (under review).

- 30. Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, et al. Development of and field‐test results for the CAHPS PCMH survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S2‐S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tijhuis GJ, Kooiman KG, Zwinderman AH, Hazes J, Breedveld F, Vliet Vlieland T. Validation of a novel satisfaction questionnaire for patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving outpatient clinical nurse specialist care, inpatient care, or day patient team care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2003;49(2):193‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greenwood‐Lee J, Wild G, Marshall D. Improving accessibility through referral management: setting targets for specialist care. Health Syst. 2017;6(2):161‐170. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenwood‐Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, Marshall DA. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marshall DA, Burgos‐Liz L, Ijzerman MJ, et al. Applying dynamic simulation modeling methods in health care delivery research—the simulate checklist: report of the ISPOR simulation modeling emerging good practices task force. Value Health. 2015;18(1):5‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):223‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, Morales A. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(2):236‐264. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qian J, Feldman DE, Bissonauth A, et al. A retrospective review of rheumatology referral wait times within a health centre in Quebec, Canada. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(5):705‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh DP, Esdaile JM. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2005;53(2):241‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ahlmén M, Nordenskiöld U, Archenholtz B, et al. Rheumatology outcomes: the patient's perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2005;44(1):105‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Mowinckel P, Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Finset A. Rheumatology care: involvement in medical decisions, received information, satisfaction with care, and unmet health care needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2006;55(3):394‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li LC, Badley EM, MacKay C, et al. An evidence‐informed, integrated framework for rheumatoid arthritis care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2008;59(8):1171‐1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Badley EM. Arthritis in Canada: what do we know and what should we know? J Rheum. 2005;72:39‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goekoop‐Ruiterman YP, de Vries‐Bouwstra JK, Kerstens PJ, et al. DAS‐driven therapy versus routine care in patients with recent‐onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(01):65‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pope JE, Haraoui B, Rampakakis E, et al. Treating to a target in established active rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor: results from a real‐world cluster‐randomized adalimumab trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(9):1401‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Damani Z, Conner‐Spady B, Nash T, et al. What is the influence of single‐entry models on access to elective surgical procedures? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lopatina E, Damani Z, Bohm E, et al. Single‐Entry Models (SEMs) for scheduled services: towards a roadmap for the implementation of recommended practices. Health Policy. 2017;121(9):963‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alberta Innovates . http://albertainnovates.ca/. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 48. Alberta Health Services . http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/about/about.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 49. Government of Canada . Canada's Health Care System. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html. Accessed December 1, 2017

- 50. Alberta Health Services . Strategic Clinical Networks. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/scns/scn.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 51. Noseworthy T, Wasylak T, O'Neill B, eds. Strategic Clinical Networks in Alberta: Structures, Processes, and Early Outcomes. Healthcare Management Forum. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]