Abstract

Despite the evidence supporting the benefits of physical activity in the prevention and treatment of most medical conditions, physical activity remains under-prescribed by physicians. Medical students will form habits during training that they are likely to maintain as future physicians. The overall purpose of this study was to investigate the underlying mechanism(s) contributing to frequency in recommending physical activity, to provide insight into how we can increase physical activity recommendations in future practice as physicians. First to fourth year medical students at three Canadian universities responded to an online survey (N = 221; 12% response rate) between November 2017 and January 2018. Results revealed that engaging in strenuous physical activity was a strong predictor for frequency in recommending physical activity to patients (p < .001). Confidence in recommending physical activity mediated the relationship between strenuous physical activity and frequency recommending physical activity (p = .005); motivation did not mediate this relationship. Students were more motivated, than they were confident, to assess, advise, counsel, prescribe and refer patients regarding physical activity (p < .05). While 70% of students stated they are aware of the Canadian physical activity guidelines, only 52% accurately recalled them. Findings suggest that increased training related to physical activity should be included in the medical school curriculum to increase students' confidence to recommend physical activity. Another way to increase confidence and frequency in recommending physical activity is to help students engage in more strenuous physical activity themselves, which will ultimately benefit both medical students and their future patients.

Keywords: Preventive medicine, Medical students, Physical activity prescription

1. Introduction

The physical and mental health benefits associated with physical activity (PA) have long been established (Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2018; Ravindran et al., 2016; Schuch et al., 2016). Unfortunately, only 20% of Canadians are accumulating enough PA to reap these health benefits (Statistics Canada, 2015). This is concerning as physical inactivity increases the risk of poor overall health and many of the most expensive chronic illnesses (González et al., 2017; Pedersen and Saltin, 2015). This has placed an ever-increasing strain on the healthcare system with an estimated total cost of 6.8 billion Canadian dollars per year (Janssen, 2012). Despite the strong evidence supporting the use of PA in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease, it remains under prescribed by physicians (Baillot et al., 2018; Bélanger et al., 2017; Hoffmann et al., 2016). Given that physicians are often a preferred source of health information and 80% of Canadians visit a physician every year, they have a unique opportunity to influence a large portion of the population (Canadian Medical Association, 2015; Thornton et al., 2016; Tulloch et al., 2006). As future physicians, it is critical to understand what factors determine a medical students' frequency recommending PA in order to work towards reducing physical inactivity among the population.

There are many levels of actions that can be taken by a physician to promote PA, not just prescription. For example, the 5 A's model includes recommendations for physicians to: Ask (identify current PA behaviour), Advise (recommend that the patient would benefit from increased PA), Assess (determine a patients' readiness to change current PA), Assist (develop goals and/or an action plan to increase PA) and Arrange (establish a follow-up to track progress) (Carroll et al., 2011). Referral to an exercise specialist (e.g., registered Kinesiologist) is a different action that has shown to improve patients' PA levels (Baillot et al., 2018; Fortier et al., 2006; Sørensen et al., 2008). However, previous research focuses primarily on PA prescription and/or PA counselling, with other actions being largely under investigated. The present study will address this gap by examining five different actions (modified from the 5 A's model) that can be taken to increase a patients' level of PA including: assess, advise, counsel, prescribe, and refer. These five actions are hereafter collectively termed ‘PA recommendations’. The present study will also consider the factors contributing to the frequency of performing these actions.

One potential factor contributing to the lack of PA prescription in practice is inadequate training during medical school and residency (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Holtz et al., 2013; Solmundson et al., 2016; Stoutenberg et al., 2015). For instance, Holtz and colleagues (Holtz et al., 2013) found that 69% of medical students viewed exercise counselling as highly relevant, but 86% indicated that their training was less than extensive. Inadequate PA training in medical school may result in a reduced likelihood to promote PA to patients.

Prior work has determined that physicians' PA recommendation practices often align with their own activity habits, such that more-active medical professionals are more likely to counsel patients on PA (Holtz et al., 2013; Ng and Irwin, 2013; Frank et al., 2008; Lobelo et al., 2008; Lobelo and de Quevedo, 2016). As future physicians, Frank et al. surveyed U.S. medical students three separate times over their four years of medical school (N = 971 for full cohort) (Frank et al., 2008). Results revealed a significant association between frequency of providing physical activity counselling to patients and whether a student complied with exercise recommendations. Patients are also more likely to adhere to PA recommendations from their physician when the practitioner themselves is active, as they are perceived to be a more credible and motivating role model (Frank et al., 2013). As future physicians, Holtz and colleagues (Holtz et al., 2013) surveyed Canadian medical students (N = 546 in British Columbia) and results showed that students who perceived exercise counselling to be highly relevant, engaged in significantly more strenuous PA compared to those who perceived it to be somewhat or not at all relevant. Distinguishing PA intensities has become a recent trend in the literature (Helgadottir et al., 2016; Panza et al., 2017; Richards et al., 2015). As such, the present study will consider how mild, moderate and strenuous PA relate to medical students' frequency in recommending PA, which has not been done previously. Although there is evidence supporting that active medical students are more likely to perceive counselling on PA as highly relevant, and that active students discuss PA more frequently with their patients, we do not specifically know why.

Several frameworks underpinning human behaviour (e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Theory of Planned Behaviour), include motivation and confidence as consistent predictors of behaviour (Dixon, 2008). While low confidence has been found to be a barrier to the delivery of PA counselling and prescription in primary care (Baillot et al., 2018; Fowles et al., 2018; Hébert et al., 2012), motivation has been overlooked. For instance, Fowles et al. (Fowles et al., 2018) evaluated the impact of a training workshop on several different PA actions. The workshop led to increased confidence and frequency to prescribe PA; however, the influence of motivation on frequency was not examined. This knowledge gap could be filled by understanding the differences between motivation and confidence to recommend PA, and how they might predict frequency recommending PA differently. Understanding these differences will help inform future efforts aimed at increasing PA promotion in future practice. For example, if medical students lack both motivation and confidence, it will be important to teach them the importance of PA as preventive and therapeutic medicine and how to promote behavioural changes among patients. However, if students are motivated but lack confidence, future efforts may focus less on why it is important, and more on how to do it.

The overall purpose of the present study is to investigate the underlying mechanism(s) contributing to frequency in recommending physical activity, to provide further insight into how we can increase physical activity recommendations in future practice as physicians. The specific research questions are:

1. a. What is the relationship between PA participation and frequency recommending PA?

-

b.

What are the direct relationships between motivation recommending PA and frequency recommending PA, and between confidence recommending PA and frequency recommending PA?

-

c.

Does motivation and/or confidence recommending PA mediate the relationship between PA participation and frequency recommending PA?

2. Are there differences between medical students' motivation and confidence to recommend PA?

Lastly, as an exploratory research question:

3. a. What percent of medical students are aware of the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines?

-

b.

What percent of medical students accurately recall the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

Research ethics approval was obtained from three Canadian medical schools. While the length of medical school varies internationally, the Canadian structure typically involves a four-year program. As such, electronic surveys were distributed among first to fourth year medical students over three months. The survey link was distributed to students via e-newsletters, Facebook posts, and announcements in mandatory class. Two reminders were sent. A total of 221 medical students responded, out of a possible 1810 (12% response rate). This response rate is typical of online surveys conducted by external researchers (Fryrear, 2015), and comparable to a recent survey involving medical students (Matthew Hughes et al., 2017).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Students reported their gender, age, ethnicity, academic background, year in medical school, and university of enrollment.

2.2.2. Physical activity

The Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) (Godin and Shepard, 1985) is a valid and reliable scale, used frequently (Joseph et al., 2014). This scale asks on average how many times a week an individual engages in strenuous, moderate and mild exercise. Scores for each intensity are calculated by multiplying strenuous activity by 9, moderate by 5, and mild by 3. A score for each intensity was generated, as well as a total PA score by summing the products of all three intensities. Students were asked about the average minutes per activity session. From this, total minutes of strenuous and moderate PA/week was calculated to determine whether the student was meeting the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines1 (hereafter referred to as ‘PA guidelines’).

2.2.3. Physical activity recommendations

The 5 A's model was modified to measure five actions that can be taken to promote PA (i.e., assess, advise, counsel, prescribe, refer). The modification was necessary for relevancy to clinical settings, and similar actions related to promoting physical activity have been used previously in primary care research (e.g., Fowles et al., 2018).

2.2.3.1. Motivation

Students were asked “How motivated are you to…” 1) assess a patient's level of PA; 2) advise a patient to increase their PA levels; 3) counsel a patient about PA; 4) provide a patient with a PA prescription; 5) provide a patient with a referral to an exercise specialist. Response options included a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = “not at all motivated” to 4 = “very motivated”.

2.2.3.2. Confidence

Students were asked “How confident are you to…” 1) assess a patient's level of PA; 2) advise a patient to increase their PA levels; 3) counsel a patient about PA; 4) provide a patient with a PA prescription; 5) provide a patient with a referral to an exercise specialist. Students rated their confidence using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = “not at all confident” to 4 = “very confident”.

2.2.3.3. Frequency

Students were asked “How frequently do you …” 1) assess a patient's level of PA; 2) advise a patient to increase their PA levels; 3) counsel a patient about PA; 4) provide a patient with a PA prescription; 5) provide a patient with a referral to an exercise specialist. Students rated their frequency with a 7-point scale (0 = “never” to 6 = “always”).

Students in all years were asked about motivation and confidence; only third and fourth year students were asked about frequency given that these years represent the core clinical clerkship years. Individual scores and total scores (summation of all five actions) of motivation, confidence and frequency were calculated. This framework has been used in previous research measuring PA counselling in primary care (Carroll et al., 2011).

2.2.4. Knowledge of physical activity guidelines

Students were asked if they were aware of the PA guidelines (yes/no). If they indicated yes, they were asked “According to the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines, how many minutes per week of moderate- to vigorous- intensity PA is recommended for adults aged 18-64?” Students responded using an interactive slider ranging from 0 to 200 (minutes per week).

2.3. Statistical analyses

To address research question 1a, correlation and hierarchal multiple regression analysis were run in SPSS version 25 (IBM, 2017). Preliminary analyses checked for violations of assumptions. For the regression analysis, the independent variables were age, ethnicity, gender, year, university and strenuous physical activity and the dependent variable was total frequency recommending physical activity. Categorical variables were dummy coded. Age, ethnicity, gender, year, and university were entered simultaneously into the regression at step 1, followed by strenuous physical activity at step 2. To address research question 1b three separate two-factor models were tested using path analysis. Strenuous physical activity, total motivation to recommend physical activity and total confidence recommending physical activity were the independent variables, and total frequency recommending physical activity was the dependent variable in all three models (Fig. 1). These direct pathways needed to be significant to proceed with research question 1c, testing indirect relationships. To address research question 1c, two separate three-factor models were tested using path analysis. Both models included strenuous physical activity as the independent variable and total frequency recommending physical activity as the dependent variable. Total motivation to recommend physical activity and total confidence recommending physical activity were tested as mediators. Additionally, a bootstrap method was used to determine mediation in SPSS AMOS. Bootstrap selection was set at 1000 samples and bias corrected-confidence level set at 95% (Cheung and Lau, 2008; IBM, n.d.). Pertaining to the second research question, five paired-samples t-tests were used to assess for differences in motivation and confidence to assess, advise, counsel, prescribe and refer. Preliminary analyses ensured that all assumptions were met, including the additional assumption that the difference between motivation and confidence scores for each participant were normally distributed. A Bonferroni adjustment was applied for multiple comparisons (p < .01). Effect sizes (d) were calculated and interpreted using Cohen's cut-points: 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), 0.8 (large) (Cohen, 1988). Descriptive statistics were generated to address research question 3.

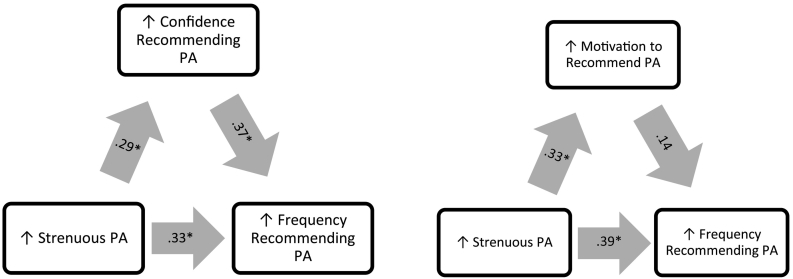

Fig. 1.

Statistically significant direct pathways, as determined by path analysis.

Note: *p < .05; PA = physical activity.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Table 1 provides demographic information for all participants included in this study. Participants ranged from 19 to 46 years old (M = 24.7, SD = 3.91) and the majority were female (61%). Regarding knowledge of PA guidelines, 70% of students indicated “yes” to being aware of them (n = 155). However, over a quarter inaccurately recalled the guidelines, indicating a number other than 150 min of MVPA/ week (n = 39). This means that only 52% of students actually knew the PA guidelines (n = 116); that is, they answered “yes” to the first question and “150 min” to the follow-up question. Among those who were aware and accurately recalled the PA guidelines, 21 had completed a Kinesiology degree and 7 of them a Physiotherapy degree. In contrast, among those who were not aware or who inaccurately recalled the PA guidelines, only 5 of them indicated completing a Kinesiology degree and 2 of them a degree in Physiotherapy.

Table 1.

Demographic information of medical student participants.

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 221) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.7 (3.9) |

| Range | 19–46 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 70 (31) |

| Female | 135 (61) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Non-response | 15 (7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 133 (60) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) |

| Aboriginal Canadian | 2 (1) |

| Black or African | 5 (2) |

| Asian | 41 (19) |

| Other | 16 (7) |

| Non-response | 23 (10) |

| University, n (%) | |

| University X | 84 (38) |

| University Y | 89 (40) |

| University Z | 48 (22) |

| Year of medical school, n (%) | |

| 1st | 91 (41) |

| 2nd | 54 (24) |

| 3rd | 31 (14) |

| 4th | 37 (17) |

| Non-response | 8 (4) |

| Academic background, n | |

| General sciences | 108 |

| Health sciences | 73 |

| Social sciences | 13 |

| Kinesiology | 26 |

| Physiotherapy | 9 |

| Other | 33 |

| Non-response | 12 |

| Physical activity guidelines, n (%) | |

| Meeting physical activity guidelines | 137 (62) |

| Not meeting physical activity guidelines | 72 (33) |

| Non-response | 12 (5) |

| Physical activity scores, mean (SD) | |

| Mild physical activity | 16.0 (19.2) |

| Moderate physical activity | 20.5 (52.6) |

| Strenuous physical activity | 25.2 (39.4) |

| Total physical activity | 61.7 (105.3) |

| Frequency recommending physical activity, mean (SD) | |

| Assess | 2.40 (1.24) |

| Advise | 2.61 (1.37) |

| Counsel | 2.70 (1.19) |

| Prescribe | 1.36 (1.14) |

| Refer | 1.48 (1.32) |

| Total | 10.40 (4.53) |

| Motivation to recommend physical activity, mean (SD) | |

| Assess | 2.91 (0.92) |

| Advise | 3.16 (0.80) |

| Counsel | 3.08 (0.83) |

| Prescribe | 3.00 (0.98) |

| Refer | 3.10 (0.92) |

| Total | 15.24 (3.76) |

| Confidence to recommend physical activity, mean (SD) | |

| Assess | 2.04 (1.03) |

| Advise | 2.31 (0.97) |

| Counsel | 2.12 (1.05) |

| Prescribe | 1.67 (1.23) |

| Refer | 1.93 (1.32) |

| Total | 10.07 (4.61) |

Note. Participants were able to select more than one option for academic background.

Note. Physical activity scores were assessed and calculated according to the LTEQ.

Note. Likert scale for frequency recommending physical activity: 0 = never, 1 = very rarely, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = frequently, 5 = very frequently, 6 = always.

Note. Likert scale for motivation and confidence to recommend physical activity: 0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite, 4 = very.

3.2. Relationship between PA participation and frequency recommending PA

Pearson correlation analyses revealed that strenuous PA was significantly associated with the frequency of assessing, advising, counselling, and prescribing PA to patients, as well as total frequency recommending PA. Table 2 provides information on all of the observed associations.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation between physical activity participation and frequency recommending physical activity (5 actions: assess, advise, counsel, prescribe, refer).

| Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Assess | – | 0.591⁎⁎ | 0.521⁎⁎ | 0.410⁎⁎ | 0.334⁎⁎ | 0.818⁎⁎ | 0.412⁎⁎ | 0.426⁎⁎ | 0.305⁎ | 0.045 |

| (2) Advise | – | 0.595⁎⁎ | 0.421⁎⁎ | 0.037 | 0.763⁎⁎ | 0.308⁎ | 0.338⁎⁎ | 0.130 | 0.152 | |

| (3) Counsel | – | 0.404⁎⁎ | 0.063 | 0.730⁎⁎ | 0.242 | 0.293⁎ | 0.043 | 0.159 | ||

| (4) Prescribe | – | 0.268⁎ | 0.699⁎⁎ | 0.250⁎ | 0.281⁎ | 0.079 | 0.153 | |||

| (5) Refer | – | 0.494⁎ | 0.124 | 0.177 | 0.104 | −0.103 | ||||

| (6) Total frequency | – | 0.236 | 0.346⁎⁎ | 0.027 | 0.097 | |||||

| (7) Total PA score | – | 0.947⁎⁎ | 0.978⁎⁎ | 0.861⁎⁎ | ||||||

| (8) Strenuous PA | – | 0.881⁎⁎ | 0.726⁎⁎ | |||||||

| (9) Moderate PA | – | 0.815⁎⁎ | ||||||||

| (10) Mild PA | – |

Note. PA = physical activity.

Level of significance at p < .05.

Level of significance at p < .01.

Hierarchal multiple regression assessed the relationship between PA on total frequency recommending PA (summation of all five actions),2 after controlling for age, ethnicity, gender, year, and university. Originally, the regression model was to include all three PA intensities as predictor variables, however there was a high correlation (>0.70) between these three variables, violating the assumption of multicollinearity. Given that strenuous PA had the strongest, significant correlation with total frequency recommending PA, it was included in the regression analyses. Demographic variables were entered at Step 1, explaining 19% of the variance in total frequency recommending PA. After entering strenuous PA at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 32%, F (6, 60) = 4.74, p = .001. Strenuous PA explained an additional 13% of the variance in frequency after controlling for demographics, R squared change = 0.13, F change (1, 60) = 11.89, p = .001. In the final model, year (β = 0.42, p = .001) and strenuous PA (β = 0.37, p = .001) made a statistically significant contribution (Table 3). In line with this, a secondary analysis revealed a significant difference in frequency scores, whereby medical students who engaged in ≥150 min of MVPA/ week recommended PA more frequently (M = 11.9; SD = 4.2) than students who did not meet the PA guidelines, M = 7.8; SD = 3.9; t (65) = −4.02, p < .001. The magnitude of the difference was large (eta squared = 0.20).

Table 3.

Summary of hierarchal regression analyses assessing the ability of strenuous physical activity to predict frequency recommending physical activity, after controlling for gender, age, ethnicity, university and year.

| Independent variable | B | Std. error | Beta | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Gender | 1.10 | 1.08 | 0.12 | 1.02 | 0.31 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.87 | |

| Ethnicity | −0.001 | 0.31 | −0.001 | −0.005 | 0.99 | |

| University | −0.51 | 0.46 | −0.13 | −1.12 | 0.27 | |

| Year | 1.64 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 3.27 | 0.002 | |

| Step 2 | Gender | 0.96 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.34 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.66 | |

| Ethnicity | −0.04 | 0.28 | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.89 | |

| University | −0.61 | 0.42 | −0.16 | −1.45 | 0.15 | |

| Year | 1.67 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 3.61 | 0.001⁎ | |

| Strenuous PA | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 3.45 | 0.001⁎ |

Note. PA = physical activity.

p < .01.

3.3. Motivation and confidence as mediators

First, three separate 2-factor path models were tested in AMOS to investigate direct relationships between variables, and results revealed significant, positive standardized regression coefficients for all models (p < .05; Fig. 1). The strongest relationship was between confidence recommending PA and frequency recommending PA (r = 0.46, p < .001), whereby greater confidence was associated with a higher frequency in recommending PA.

Next, two separate 3-factor path models were tested in AMOS using bootstrapping to test potential mediators (i.e., confidence and motivation) for the indirect effect of strenuous PA on frequency recommending PA. The standardized regression coefficient between strenuous PA and confidence recommending PA was significant (r = 0.29), as was the coefficient between confidence recommending PA and frequency recommending PA (r = 0.37; Fig. 2). Bootstrapping results revealed a significant indirect effect of strenuous PA on frequency recommending PA, through confidence recommending PA (r = 0.33, p = .005, 95% CI: 0.024–0.243).

Fig. 2.

Testing indirect pathways with path analysis and bootstrap approximation using two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Note: *p < .05; PA = physical activity.

Although the effect of strenuous PA on frequency recommending PA remained significant after controlling for confidence recommending PA in the 3-factor model (r = 0.33, p = .002; Fig. 2), the effect was reduced compared to the 2-factor model including only strenuous PA and frequency recommending PA (r = 0.44, p < .001; Fig. 1). These results support partial mediation. That is, students who engaged in strenuous PA reported an increased confidence recommending PA, which corresponded to an increased frequency recommending PA. Bootstrapping results testing motivation to recommend PA as a mediator for the indirect effect of strenuous PA on frequency recommending PA were not significant (r = 0.39; p = .16, 95% CI: −0.008–0.148).

3.4. Differences in motivation and confidence to recommend PA

Results of paired-samples t-tests revealed that students reported significantly greater motivation, compared to confidence, for all five actions (Table 4). Effect sizes were large (d > 0.80). Students reported the greatest motivation to advise a patient to meet the PA guidelines, and the lowest motivation to assess a patient's level of PA. Students reported the greatest confidence to advise, and the lowest confidence to prescribe PA.

Table 4.

Differences in medical students' motivation and confidence to recommend physical activity in future practice (5 actions: assess, advise, counsel, prescribe, refer).

| Dependent variable | Independent variables | n | Mean | Std. dev. | 95% confidence interval of the difference |

t | df | Sig. | Effect size d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Assess | Motivation | 212 | 2.91 | 0.92 | −1.02 | −0.72 | −11.37 | 211 | 0.000⁎ | 0.89 |

| Confidence | 212 | 2.04 | 1.03 | |||||||

| Advise | Motivation | 212 | 3.16 | 0.80 | −0.98 | −0.72 | −12.92 | 211 | 0.000⁎ | 0.95 |

| Confidence | 212 | 2.31 | 0.97 | |||||||

| Counsel | Motivation | 212 | 3.08 | 0.83 | −1.11 | −0.83 | −13.46 | 211 | 0.000⁎ | 1.01 |

| Confidence | 212 | 2.12 | 1.05 | |||||||

| Prescribe | Motivation | 210 | 3.00 | 0.98 | −1.51 | −1.14 | −14.20 | 209 | 0.000⁎ | 1.19 |

| Confidence | 212 | 1.67 | 1.23 | |||||||

| Refer | Motivation | 212 | 3.10 | 0.92 | −1.34 | −0.99 | −12.93 | 211 | 0.000⁎ | 1.01 |

| Confidence | 212 | 1.93 | 1.32 | |||||||

Note. 0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite, 4 = very.

p < .01.

4. Discussion

Results from this study provide further insight into how we can increase PA recommendations, as an important preventive and therapeutic strategy for several chronic illnesses. It is important to understand these mechanisms, and guide medical students to form positive, evidence-based habits during training that they will carry with them throughout their careers. However, interpretation of these findings should be taken with caution, due to the low response rate. As it relates to medical students' own PA behaviours, results revealed that strenuous PA was a significant predictor of frequency recommending PA. This is consistent with previous work which found a relationship between engaging in strenuous PA and perceiving exercise counselling to be highly relevant (Holtz et al., 2013). It is possible that those who engage in more strenuous types of PA experience health benefits in themselves, making them more likely to recommend PA to their patients. The concept of exercise identity (i.e., defining oneself as an ‘exerciser’) (Burke and Stets, 2013) provides another possible explanation for the relationship between engaging in strenuous PA and frequency recommending PA. Previous research has suggested that individuals who engage in more PA (i.e., frequency, duration, and intensity) have a stronger PA identity (Strachan and Whaley, 2013), and those who identify with PA are more likely to discuss activity pursuits with others (Perras et al., 2016). Taken together, it is possible that medical students who engage in strenuous PA, have a strong PA identity, resulting in more frequent discussions related to PA with patients.

Next, several models were tested to explore direct and indirect relationships between the dependent variables and frequency recommending PA. Results revealed that motivation and confidence were both positively related to frequency recommending PA; however, only confidence significantly mediated the relationship between strenuous PA and frequency recommending PA. While previous research has shown a direct relationship between a provider's own activity levels and their confidence in counselling (Howe et al., 2010) and between a provider's own activity levels and frequency of counselling (Frank et al., 2000), this is the first study to our knowledge to consider confidence as a mediator in the relationship between activity levels and frequency in recommending PA.

These results show that one potential way to increase confidence levels, and in doing so, frequency in recommending PA, is to help medical students engage in PA themselves. Ultimately, this will benefit both medical students' own health, and increase their confidence and frequency in recommending PA to the general population. Future research should implement PA interventions tailored specifically for medical students. Moreover, universities should consider ways to promote PA among students, such as offering free classes over lunch (e.g., yoga, martial arts, running group) and/or providing students access to a PA counsellor.

The second research question investigated whether there are differences in medical students' motivation and confidence to recommend PA. Results revealed that medical students are significantly more motivated than they are confident for all five actions. This lack of confidence is likely due to inadequate training on how to promote PA to specific patients, including those who are healthy and those with multiple comorbidities. Low level of confidence to counsel and prescribe PA has been found previously among medical professionals, despite their perception that PA is important (Solmundson et al., 2016; Howe et al., 2010; Kennedy and Meeuwisse, 2003; Rogers et al., 2006). Fowles et al. provide support for a training workshop to increase confidence and frequency recommending PA (Fowles et al., 2018). However, this is the first study to compare motivation and confidence to recommend PA, and how they might predict frequency recommending PA differently. Regarding motivation, results of this study showed that medical students had high levels of motivation for all five actions related to recommending PA. This is encouraging, as it suggests that students want to do it and that they see the value in it, but they lack the confidence to do so.

Descriptive statistics were generated to answer the third research question, which sought to determine what percent of medical students are aware of the PA guidelines and what percent can accurately recall them. Results revealed that only 52% of students in this study were aware of and accurately able to recall the PA guidelines (18% inaccurately recalled the guidelines, 30% stated they did not know them). This low level of knowledge related to PA guidelines has been found previously (Douglas et al., 2006), and is not overly surprising, as previous research has suggested that there is a lack of training related to PA in the Canadian medical school curriculum (Holtz et al., 2013).

Taken together, the lack of knowledge related to the PA guidelines, and the low confidence to recommend PA to patients, shows that there is insufficient exposure to PA training in medical school. The medical school curriculum should incorporate training related to PA as preventive and therapeutic medicine, including information on the PA guidelines. Although significant strides have been made to do so, including a motion to include PA education in Canadian medical schools proposed by Dr. Jane Thornton and passed at CMA's 2016 General Council (Canadian Medical Association, 2016), these proposed changes have yet to be formally implemented into the medical curriculum.

4.1. Study strengths and limitations

There were several strengths associated with this study. First, the sample included in this study is generally representative of the Canadian medical school population. Indeed, data from the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada show that in 2016/17 first year medical students were predominantly female (58%) and between the ages of 20–25 (The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, 2017). Second, previous research has not investigated the mediating role of motivation and confidence in recommending PA in the relationship between PA participation and frequency recommending PA. It is important to understand the mechanisms contributing to frequency to promote PA recommendations with patients and work towards improving the overall health of the population. Third, previous research has focused solely on PA prescription and/or counselling among medical professionals, neglecting other actions that can be taken to promote PA with patients. This study included five different levels of action related to PA, for a more comprehensive understanding of medical student's confidence, motivation and frequency in recommending PA. Finally, this study focused on medical students specifically, which is important because learners have shown to be more open to learning new strategies and changing their behaviour, compared to practicing physicians (Solmundson et al., 2016).

There were also some limitations that should be considered. For instance, there was a low response rate and relatively fewer third and fourth year students completed the survey, compared to first and second. This may speak to the increased time demands that clerkship students face. This limited the sample size for the path analyses, as only third and fourth year students were asked about frequency. Future research should use additional recruitment methods, and should target third and fourth year students specifically (e.g., announcements and/or advertisements in hospitals). Another limitation is self-report measures and using recall to assess frequency recommending physical activity, which may result in bias. Future research should consider using accelerometers to track PA and review electronic medical records to measure frequency recommending PA. Finally, there may have been self-selection bias in this study, whereby students who are interested in the promotion of PA responded to the survey. This may have resulted in an over-estimation of motivation, confidence and frequency recommending PA, as well as increased awareness of the PA guidelines in our sample.

5. Conclusion

Overall, results of this study show that medical students are highly motivated to recommend PA, but often lack the knowledge and confidence necessary to assess, advise, counsel, prescribe and refer. This highlights the need for increased training related to PA as preventive and therapeutic medicine in medical school so that students gain positive, evidence-based habits moving forward in their career. Increased training may correspond to an increased confidence, and thus frequency recommending PA in future medical practice. Another way to increase confidence and frequency is to encourage students to engage in more strenuous PA themselves, which will ultimately benefit both medical students and their future patients.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None to declare.

Footnotes

Canadian physical activity guidelines recommend adults accumulate 150 min of moderate- to vigorous- PA per week. Throughout this paper the term strenuous is used to describe vigorous physical activity, for consistency with the language used in the LTEQ.

Total frequency recommending physical activity was used as the dependent variable for regression and path analyses. These analyses were also run individually for all five actions (frequency to assess, advise, counsel, prescribe, refer), but due to length restrictions and similar significant results being found for all five actions, total frequency recommending physical activity results are reported.

References

- Baillot A., Baillargeon J.P., Pare A., Poder T.G., Brown C., Langlois M.F. Physical activity assessment and counseling in Quebec family medicine groups. Can. Fam. Physician. 2018;64:234–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger M., Phillips E.W., O'Rielly C., Mallet B., Aubé S., Doucet M. Longitudinal qualitative study describing family physicians' experiences with attempting to integrate physical activity prescriptions in their practice: ‘it's not easy to change habits’. BMJ. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke P.J., Stets J.E. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2013. Identity Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Medical Association Healthy behaviours – promoting physical activity and healthy eating. 2015. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/policies/cma_policy_healthy_behaviours_promoting_Physicial_Activity_and_Healthy_Eating_PD15-12-e.pdf Available from:

- Canadian Medical Association General consent motions. 2016. https://www.cma.ca/EN/Pages/cma-consent-agenda-videos.aspx Available from.

- Carroll J.K., Antognoli E., Flocke S.A. Evaluation of physical activity counseling in primary care using direct observation of the 5As. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011;9:416–422. doi: 10.1370/afm.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung G.W., Lau R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: bootstrapping with structural equation models. Org Res Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Routledge Academic; New York, NY: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A. The Kings Fund; London: 2008. Motivation and Confidence: What Does it Take to Change Behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas F., Torrance N., Van Teijlingen E., Meloni S., Kerr A. Primary care staff's views and experiences related to routinely advising patients about physical activity. A questionnaire survey. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier M., Tullock H., Hogg W. A good fit: integrating physical activity counselors into family practice. Can. Fam. Physician. 2006;52:942. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles J.R., O'Brien M.W., Solmundson K., Oh P.I., Shields C.A. Exercise is Medicine Canada physical activity counselling and exercise prescription training improves counselling, prescription, and referral practices among physicians across Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:535–539. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Biola H., Burnett C.A. Mortality rates and causes among U.S. physicians. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000;19:155–159. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Tong E., Lobelo F., Carrera J., Duperly J. Physical activity levels and counseling practices of U.S. medical students. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008;40:413–421. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ff399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Dresner Y., Shani M., Vinker S. The association between physicians' and patients' preventive health practices. CMAJ. 2013;185:649–653. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryrear A. What's a good survey response rate? 2015. https://www.surveygizmo.com/resources/blog/survey-response-rates/ Available from:

- Godin G., Shepard R.J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González K., Fuentes J., Márquez J.L. Physical inactivity, sedentary behavior and chronic diseases. Korean J Fam Med. 2017;38:111–115. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2017.38.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert E.T., Caughy M.O., Shuval K. Primary care providers' perceptions of physical activity counselling in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012;46:625–631. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgadottir B., Hallgren M., Ekblom O., Forsell Y. Training fast or slow? Exercise for depression: a randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016;91:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.C., Hons B., Maher C.G., Phty B., Bphysed T.B., Sherrington C. Prescribing exercise interventions for patients with chronic conditions. CMAJ. 2016;188:510–519. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz K.A., Kokotilo K.J., Fitzgerald B.E., Frank E. Exercise behaviour and attitudes among fourth-year medical students at the University of British Columbia. Can. Fam. Physician. 2013;59:e26–e32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe M., Leidel A., Krishnan S.M., Weber A., Rubenfire M., Jackson E.A. Patient-related diet and exercise counseling: do providers' own lifestyle habits matter? Prev. Cardiol. 2010;13:180–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2010.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Boostrapping 2018. https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/SSLVMB_24.0.0/spss/bootstrapping/idh_idd_bootstrap.html Available from.

- Janssen I. Health care costs of physical inactivity in Canadian adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:803–806. doi: 10.1139/h2012-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R.P., Royse K.E., Benitez T.J., Pekmezi D.W. Physical activity and quality of life among university students: exploring self-efficacy, self-esteem, and affect as potential mediators. Qual. Life Res. 2014;23:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M.F., Meeuwisse W.H. Exercise counselling by family physicians in Canada. Prev. Med. 2003;37:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobelo F., de Quevedo I.G. The evidence in support of physicians and health care providers as physical activity role models. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016;10:36–52. doi: 10.1177/1559827613520120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobelo F., Duperly J., Frank E. Physical activity habits of physicians and medical students influence their counseling practices. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008;43(2):89–92. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.055426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew Hughes J.D., Azzi E., Rose G.W., Ramnanan C.J., Khamisa K. A survey of senior medical students' attitudes and awareness toward teaching and participation in a formal clinical teaching elective: a Canadian perspective. Med Educ Online. 2017;22 doi: 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng V., Irwin J.D. Prescriptive medicine: the importance of preparing Canadian medical students to counsel patients toward physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2013;10:889–899. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.6.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza G.A., Taylor B.A., Thompson P.D., White C.M., Pescatello L.S. Physical activity intensity and subjective well-being in healthy adults. J. Health Psychol. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1359105317691589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen B.K., Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2015;2:1–72. doi: 10.1111/sms.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perras M.G.M., Strachan S.M., Fortier M.S. Possible selves and physical activity in retirees: the mediating role of identity. Res Aging. 2016;38:819–841. doi: 10.1177/0164027515606191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC] Let's get moving: a common vision for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary living in Canada. 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/lets-get-moving.html Available from:

- Ravindran A.V., Balneaves L.G., Faulkner G., Ortiz A., McIntosh D., Morehouse R.L. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 5. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2016;61:576–587. doi: 10.1177/0706743716660290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J., Jiang X., Kelly P., Chau J., Bauman A., Ding D. Don't worry, be happy: cross-sectional associations between physical activity and happiness in 15 European countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:53–61. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers L.Q., Gutin B., Humphries M.C., Lemmon C.R., Waller J.L., Baranowski T. Evaluation of internal medicine residents as exercise role models and associations with self-reported counseling behavior, confidence, and perceived success. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18:215–221. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch F.B., Vancampfort D., Richards B., Rosenbaum S., Ward P.B., Stubbs B. Exercise as treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016;77:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmundson K., Koehle M., McKenzie D. Are we adequately preparing the next generation of physicians to prescribe exercise as prevention and treatment? Residents express the desire for more training in exercise prescription. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7:e79–e96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen J.B., Kragstrup J., Skovgaard T., Puggaard L. Exercise on prescription: a randomized study on the effect of counseling vs counseling and supervised exercise. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2008;18:288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Distribution of the household population meeting/not meeting the Canadian physical activity guidelines, by sex and age group, occasional (percentage) 2015. http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/department-ministere/state-public-health-status-2016-etat-sante-publique-statut/alt/pdf-eng.pdf Available from.

- Stoutenberg M., Stasi S., Stamatakis E., Danek D., Dufour T., Trilk J.L., Blair S.N. Physical activity training in US medical schools: preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys. Sportsmed. 2015;43:388–394. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan S.M., Whaley D.E. Identities, schemas, and definitions: how aspects of the self influence exercise behaviour. In: Ekkekakis P., editor. Handbook of Physical Activity and Mental Health. Routledge; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada Canadian medical education statistics. 2017. https://afmc.ca/sites/default/files/CMES2017-Complete.pdf Available from:

- Thornton J.S., Frémont P., Khan K., Poirier P., Fowles J., Wells G.D., Frankovich R.J. Physical activity prescription: a critical opportunity to address a modifiable risk factor for the prevention and management of chronic disease: a position statement by the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016;0:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulloch H., Fortier M., Hogg W. Physical activity counseling in primary care: who has and who should be counseling? Patient Educ. Couns. 2006;64:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]