Abstract

Patients with Behçet's disease (BD) suffer from episodic ocular and mucocutaneous attacks, resulting in a reduced quality of life. The phenotype of Japanese BD has been changing over the past 20 years, and the rate of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B*51-positive complete type is decreasing while that of intestinal type is increasing. This phenotypical evolution may be related to changes in as-yet-unknown environmental factors, as the immigration influx in Japan is low. Mechanisms discovered by genome-wide association studies include ERAP1-mediated HLA class I antigen bounding pathway, autoinflammation, Th17 cells, natural killer cells, and polarized macrophages, a similar genetic architecture to Crohn's disease, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriasis. As for treatments, management guidelines have been implemented, and the development of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors is markedly improving the outcome of BD, but evidence supporting treatment for special-type BD is limited. The classification of BD into distinct clusters based on clinical manifestations and genetic factors is crucial to the development of optimized medicine.

Keywords: Behçet's disease, genetics, environmental factors, GWAS, HLA, ERAP1

Introduction

Behçet's disease (BD), initially reported by Turkish dermatologist Hulusi Behçet in 1937, is a disease of unknown cause, characterized by episodic inflammation of multiple organs, such as the eyes, skin, mucosa, brain, intestine, and large vessels (1,2). A diagnosis of BD is made by a combination of clinical manifestations, and there is no disease-specific symptom or laboratory test for diagnosing the disease. BD can be one of the toughest rheumatic diseases to diagnose owing to its heterogeneity and “time and space” development of lesions.

The diagnosis of BD has become even more challenging in recent years in Japan; the rate of incomplete BD is increasing (3), and their phenotypes are becoming milder (4). For example, BD was the most frequent cause of non-infectious uveitis in Japan until the 1980s, but currently, sarcoidosis is the most frequent cause (5). Such BD patients who may not meet the BD diagnostic criteria can still develop severe organ damage, such as intestinal BD, and thus the identification of the characteristics and prognosis of modern-day BD patients is warranted.

In this review, we describe the recent epidemiological and genetic data of BD, management guidelines and suggest a treatment strategy to cope with issues in BD faced today.

The Diagnosis of BD

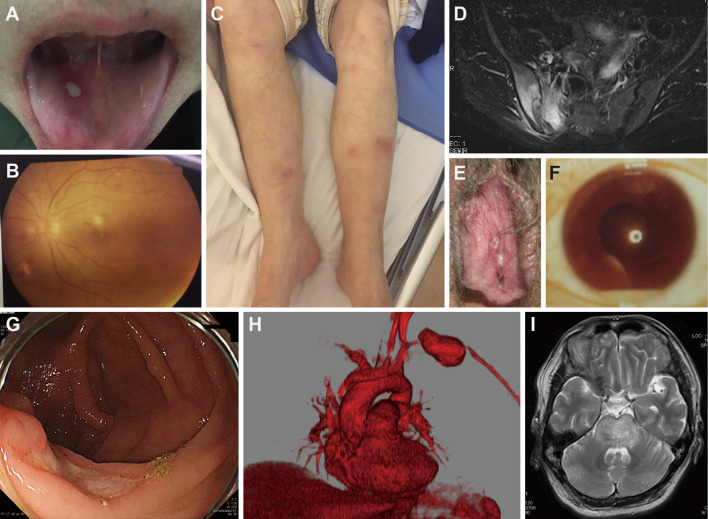

BD is a heterogeneous disease with multiple-organ involvement. Fig. 1 shows the variety of symptoms found in BD patients. As such, the condition is also called Behçet syndrome (1). In Japan, the diagnostic criteria of Behçet's Disease Research Committee were revised in 1987, and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan has since been using these criteria to diagnose the disease (Table 1) (6).

Figure 1.

Clinical manifestations in Japanese patients with Behçet’s disease. Various BD symptoms found in Japanese BD patients. A: oral ulcer; B: posterior ocular uveitis; C: erythema nodosum; D: MRI T2-weighted image showing right sacroiliitis; E: genital ulcer; F: anterior uveitis with hypopyon; G: deep ulcer in the ileocecum; H: aneurysm of the left subclavian artery; I: MRI T2-weighted image showing acute-type neuro Behçet’s disease in the brain stem.

Table 1.

A Comparison of the Behçet’s Disease Criteria.

| Japanese | ISG7 | ICBD9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral ulcer | ◎ | ● | ○ 2 points | |||

| Genital ulcer | ◎ | ○ | ○ 2 points | |||

| Skin region | ◎ | ○ | ○ 1 point | |||

| Uveitis | ◎ | ○ | ○ 2 points | |||

| Pathergy test | × | ○ | ○ 1 point | |||

| Arthritis | ○ | × | × | |||

| Epididymitis | ○ | × | × | |||

| Gastrointestinal | ○ | × | × | |||

| Neuro | ○ | × | ○ 1 point | |||

| Vascular | ○ | × | ○ 1 point |

◎: indicates symptoms included in major criteria, ○: indicates symptoms included in each set of criteria, ×: indicates symptoms not included, ●: indicates that the symptom must be included.

Japanese: 3 major criteria, or uveitis and 1 major or 2 minor criteria, or 2 major and 2 minor criteria are required for the diagnosis; ISG: International Study Group Criteria, 3 out of 5 components are required; ICBD: International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease, ≥4 points are required to fulfil the criteria.

The diagnosis of BD is made based on a combination of symptoms; recurrent aphthous oral ulcers, skin lesions, ocular inflammation, and genital ulcers are included as “major symptoms,” and patients with all four major symptoms during the clinical course are defined as having complete-type BD. Arthritis, intestinal ulcers, epididymitis, vascular lesions, and neurological disease are considered “minor symptoms.” The confirmation of the recurrence of these conditions is crucial to establish the diagnosis of BD. Patients with central nervous system involvement, vascular, and gastrointestinal involvement are categorized as having “special-type” BD. Usually, patients do not present all of the BD symptoms at the same time, and many of the symptoms may appear separately (4). For example, oral ulcers appear an average of seven years before the diagnosis, while special-type BD tends to develop a couple of years after the BD diagnosis (4). Inflammation in the genital and ileocecal areas as well as the brain stem suggest high odds of having BD (1). The phenotype of BD is complicated, as each component of the criteria can further be divided into distinct phenotypes; eye disease can either be anterior or posterior uveitis; skin rash can be pustulosis, erythema nodosum, or superficial venous thrombosis; vascular disease can be an aneurysm or embolism, and so on.

In countries such as Turkey, the International Study Group (ISG) criteria have been used to classify BD (Table 1) (7). The ISG criteria are more stringent than the Japanese criteria, as they do not account for special-type, and the presence of oral ulceration is mandatory. A pathergy test, which is rarely positive in Japanese BD, is included (8). The recently proposed International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ICBD) account for neuro and vascular BD but not intestinal BD (9). The main reason intestinal BD is not included in the ISG or ICBD criteria is that intestinal BD is rare in the Middle East (prevalence: about 1-7%), while it is common in Japan (about 12%) (3,10).

Other symptoms, such as general fatigue, myalgia, chest pain and psychiatric symptoms, are common in BD but are not included in the criteria. In rare cases (at least in Japan), familial Mediterranean fever, spondyloarthritis (SpA; enthesis and sacroiliitis), MAGIC syndrome (a complication with relapsing polychondritis), IgA nephritis, and myelodysplastic syndrome with trisomy 8 may coexist with BD (11-14). BD is classified as an autoinflammatory disease because of its episodic inflammatory attacks, low prevalence of auto-antibodies, and effectiveness of colchicine (15).

There are no specific laboratory data indicating BD. The serum CRP is lower than that with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and the interleukin (IL)-6 levels in spinal fluid may be useful for the diagnosis of chronic progressive type neuro-BD (16). Serum IgD has long been measured in Japan, but the clinical relevance of its measurement is uncertain.

Epidemiology and Environmental Factors in BD

BD patients are highly prevalent along the Silk Road (17). In Turkey, the prevalence of BD is 370 per 100,000 people (about 0.4%), but its incidence in Europe and North America is low (1). The prevalence rate in Japan is about 16 per 100,000 people, and 20,035 persons are medical beneficiaries according to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2014). There is no marked gender difference in the overall disease, but arthritis and genital ulcer are more common in women, whereas central nervous system and eye lesions are more prevalent in men (3). A possible explanation for the male predominance of neuro-BD is that cigarettes may trigger neuroinflammation and that men tend to smoke more than women (18).

It has long been suggested that both environmental and genetic factors are crucial for the occurrence of BD. Several pieces of circumstantial evidence support the role of environment factors in BD. First, the BD incidence rate of Hawaiians of Japanese descent is reported to be lower than in Japanese patients living in Japan (19). Second, it is well known that the disease ameliorates over time (20). Third, dental treatment and inoculation with Streptococcus for vaccination may trigger the BD onset (21). Finally, the phenotype of BD is changing in Japan and Korea, as the proportion of complete-type patients has decreased while that of intestinal-type has increased (3,22). These data suggest that environmental factors are essential in the etiology of BD. Whenever possible, avoiding skin damage, such as surgical intervention, acupuncture, and moxibustion, which can provoke BD skin reactions, may be recommended.

Genetics of BD

BD is classified as a multigenic disease, and the penetration of individual loci is small. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B*51, which was reported by Ohno et al. in 1973, confers the strongest genetic predisposition toward BD, as has been shown worldwide, but about 15% of healthy Japanese individuals possess HLA-B*51, and about 30% of BD patients do not possess HLA-B*51 (20,21). Thus, it is not very useful for the diagnosis of BD (23,24). However, HLA-B*51 positivity is associated with uveitis and neuro-BD (25).

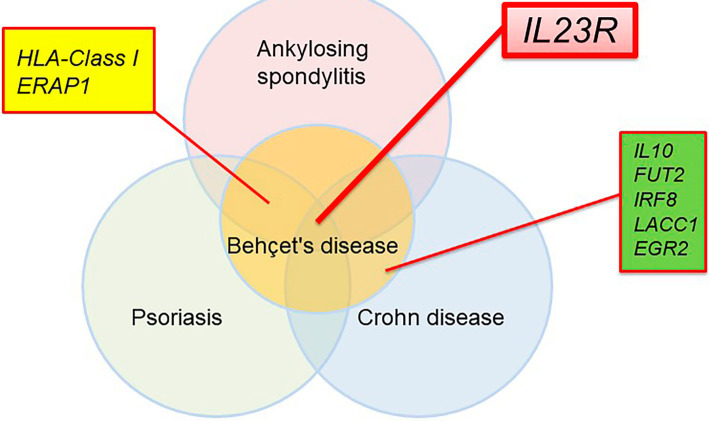

We and others have also reported 17 BD disease susceptibility loci, including HLA-A*26 (A*03 in Turkish), IL23R, STAT4, and ERAP1, through genome-wide association analyses (GWASs) (Table 2) (26-29). Both HLA-Class I, ERAP1 and IL23R have also been determined to be susceptibility genes of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and psoriasis, indicating that the pathogenesis of these diseases is similar to that of BD. Fig. 2 depicts the genetic overlap between BD and other SpAs [a disease concept encompassing AS, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) proposed by Moll et al. (30)]. Recently, the disease concept of “MHC Class I-o-pathy,” diseases, which exhibit HLA-class I and ERAP1 interaction, was proposed (31).

Table 2.

Loci Identified by GWASs and Similar Genetic Analyses of Behçet’s Disease.

| Year | Reference | Population | Loci |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 69 | Turkey | * |

| 2010 | 26 | Japan | HLA-A*26 IL10 IL23R |

| 2010 | 28 | Turkey | HLA-A*03 IL10 IL23R |

| 2012 | 70 | China | STAT4 |

| 2013 | 27 | Turkey, Japan | CCR1 STAT4 KLRC4 ERAP1 |

| 2013 | 56 | Turkey | MEFV M694V |

| 2013 | 71 | Korea | * |

| 2014 | 72 | Iran | FUT2 |

| 2015 | 73 | European, Middle East | IL12A |

| 2017 | 29 | Turkey, Japan, Iran | IL1B, IRF8, IL12A, FUT2, RIPK2, EGR2, LACC1, PTPN1 |

Loci with genome-wide evidence (p<5.0×10-8) are listed in the table.

*No loci with genome-wide significance were identified. IL: interleukin, FUT2: fucosyltransferase 2, HLA: human leukocyte antigen, STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription, KLRC: killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 4, ERAP: Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1, MEFV: Mediterranean Fever, IRF8: interferon regulatory factor 8 binding protein, RIPK2: receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2, EGR2: early growth response 2, LACC1: laccase domain containing 1, PTPN1: protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1

Figure 2.

Overlapping genetic architecture of Behçet’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. The IL23R gene lies in the center of the circles. HLA-Class I and ERAP1 are both found in BD, AS, and psoriasis.

Treatments for BD

Unlike RA, no treat-to-target approach has been developed for BD treatments. In addition, there are only a few disease activity scoring systems available for BD (32,33). For non-organ damaging symptoms, topical steroid, colchicine, low-dose prednisolone, orally administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are generally used. High-dose steroids, immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine A, azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate, and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody are used for severe forms of the disease (1). The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) announced an evidence-based BD management guideline (2018 edition) (34). Unfortunately, even in this guideline, no strong recommendation was made for special-type BD because of the limited amount of evidence. Azathioprine, cyclosporine A, interferon (not covered by insurance in Japan), and anti-TNF-α antibody are recommended for uveitis (35,36). The use of anti-TNF-α antibody is recommended for special-type BD in addition to immunosuppressants. Guidelines for the management of BD are currently being developed by the Japan BD Research Committee.

The Japanese government has approved the anti-TNF-α antibodies infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab for the treatment BD. In BD, combination with methotrexate (MTX) is not required for IFX administration as in RA, but it is possible that production of human antibody against chimeric antibody may be suppressed by using concomitant immunosuppressants, such as MTX and AZA (37). Anti-TNF-α antibody treatment for special-type BD is also covered by insurance in Japan. However, there is a lack of substantial evidence to support the use of anti-TNF-α antibody for these rare conditions; only a small study with an open-label single-arm clinical trial has examined this approach (38,39). In addition, the efficacy of the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast reached the primary endpoint in a phase 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trial of BD stomatitis (40). Apremilast has insurance indications for psoriasis in Japan (41).

At present, several biologics that manipulate IL-17 pathways, such as antibodies against IL-12/IL-23, and IL-17A, can be used to treat psoriasis in Japan (42). As described above, IL23R is a susceptible gene for BD and psoriasis; these anti-Th17 treatments strategy may therefore be of benefit for BD (43). The Janus kinase (Jak)-STAT pathway inhibitor is indicated for RA (44). As STAT4 is a susceptibility gene for both RA and BD, Jak inhibitor may be useful for the treatment of BD (27,45).

Pathogenesis of BD from Genetic and Environmental Aspects

Finally, we summarize the possible mechanisms proposed based on GWASs and epidemiological analyses of BD.

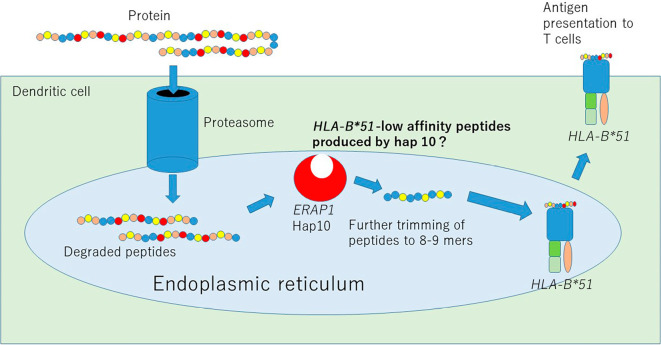

i) Pathway involved in peptide binding to HLA

In AS, psoriasis, and BD, gene interaction is found between single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)s of HLA-Class I and ERAP1 (27,46-48), which is a rare phenomenon showing an effect more than the additive effect between two independent genes and is genetic evidence that genes exhibiting interaction functionally cooperate with each other to contribute to the pathological condition. In BD, AS, and psoriasis, the process by which a specific peptide to a particular HLA-Class I antigen is presented via ERAP1 is vital for disease pathogenesis (Fig. 3). Indeed, it was recently reported that ERAP1 allotype 10 (a type containing R725Q polymorphism, also called hap10), which is a risk factor for BD, is likely to produce HLA-B*51 low-affinity peptides (49). Because homozygosity but not heterozygosity of ERAP1 hap10 carries a substantial risk for BD (48), we suggest that a deficiency in BD-protective peptides, which may “put a lid on” HLA-B*51, produced by ERAP1 hap10 activates HLA-B*51-mediated inflammation in BD.

Figure 3.

ERAP1-mediated antigen processing in BD. Proteins engulfed by dendritic cells (DC) are first degraded by proteasomes. Through TAP, peptides enter the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are further trimmed by ERAP1. ERAP1 hap10, the low-activity form of ERAP1, produces HLA-B*51-low-affinity peptides. These peptides bind to HLA within the ER and then move to the surface of the DC, where they are eventually recognized by T cells.

i) Natural killer cells

KLRC4, another BD-susceptible locus, encodes NKG2F, a natural killer (NK) receptor whose function is largely unknown (50). The role of the similar gene NKG2D has been studied intensively in the field of transplantation (51,52). NKG2D recognizes MICA, a gene that resides next to HLA-B. GWASs have revealed that HLA-B*51 and MICA-allele A6 are in strong linkage disequilibrium, suggesting that MICA might play an additional role to HLA-B*51 in BD (53,54). As a result, MICA expressed on the surface of the target cells may be recognized by the NK receptor NKG2F, thereby potentially inducing NK cell-dependent cell cytotoxicity to the target cells. As mentioned above, the production of BD-protective peptides might be reduced by ERAP1 hap10, which further decreases HLA-B*51-bound peptides, resulting in lower HLA-B expression at the cell surface. NK cells may attack such “HLA-B*51low-MICAhigh” mucocutaneous cells via NK receptor NKG2F. In addition, the NK receptors killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) KIR3DL1, which inhibits the NK function, and KIR3DS1, which activates the NK function, recognize HLA-B*51 Bw4 motif (55). A recent study evaluated the presence of KIR3DL1 or KIR3DS1 alleles in Turkish BD patients bearing HLA-B with a Bw4 motif. However, there no significant differences in the presence between BD patients and controls (55). Further functional studies are needed to clarify whether or not an abnormality in the balance of these two receptors has functional consequence in BD.

ii) Th17 cells

As mentioned above, the IL-23 receptor (IL23R) is associated with SpA (Fig. 2). The disease-protective variant IL23R R381Q is associated with reduced IL-23 dependent IL-17 production (56). IL23R mediates Th17 T cell differentiation and is a susceptibility gene not only for SpA but also for bacterial infection leprosy (57). It is likely that the immune response of Th17 cells to bacteria is involved in BD.

iii) Autoinflammation

Genetic evidence for an innate immune response in BD comes from a candidate gene analysis performed by next-generation sequencing. We reported that mutations in the innate immune receptors TLR4 and NOD2 are associated with BD (56). Furthermore, Turkish MEFV M694V, a causative variant of familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), is associated with BD (56). MEFV M694V is not prevalent in Japanese, but the allele frequency of the similarly FMF-causative mutation M694I was found to be 0.1-0.3% in the Japanese population. MEFV encodes the protein pyrin, which detects structural changes in Rho GTPase induced by toxins, such as that of Clostridium difficile, leading to IL-1β production by pyrin-inflammasome formation (58). Macrophages from individuals with MEFV exon 10 mutations (M694I, M694V, etc.) spontaneously produce IL-1β due to constitutive pyrin-inflammasome activation (59). Furthermore, our recent genetic analysis identified SNPs associated with IL-1β production in BD (29). The BD-susceptible locus FUT2 is thought to be essential for controlling intestinal bacterial flora and is also associated with IBD (29).

Overall, genetic evidence suggests that intestinal bacteria are involved in the development of BD. Indeed, a microbiome analysis suggests dysbiosis in BD patients (60). Control of the immune response against microorganisms is a potential treatment strategy for BD that should be considered in the future.

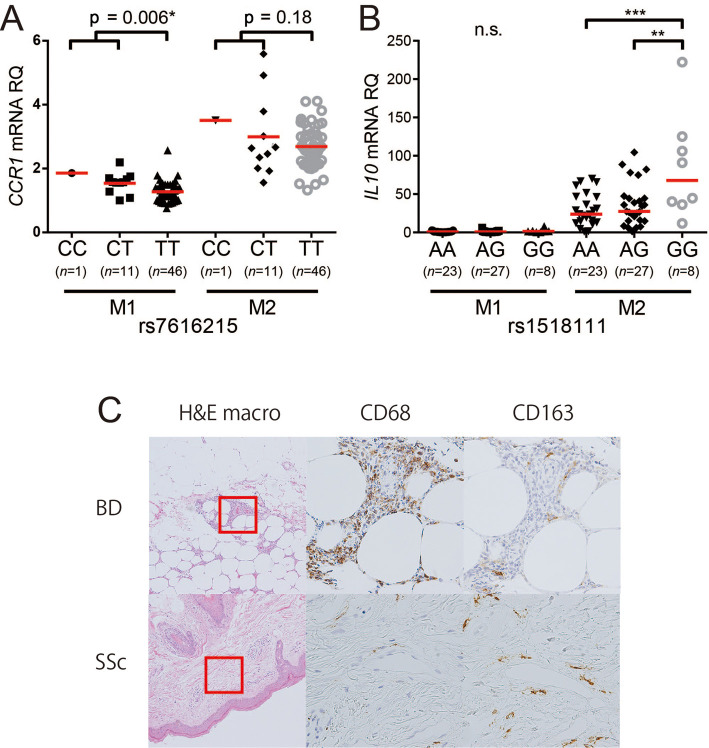

iv) Polarized macrophages

One limitation of GWASs is that they do not tell us the operational basis of the locus, necessitating further basic research. Expression quantity locus (eQTL) analyses have been performed in the context of GWASs (61). A BD GWAS showed that loci IL10 and CCR1 are highly expressed in the monocyte/macrophage lineage (27,28). IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, and its deficiency causes infantile-onset severe IBD mimicking BD (62). Indeed, SNPs with a lower IL-10 expression are associated with a risk of BD (28). CCR1 is a chemokine receptor involved in cell migration. Surprisingly, a lower rate of monocyte migration was identified as a risk factor for BD (27). Macrophages have a subset of inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 (63). Human peripheral blood monocytes that differentiate to M2 in vitro with macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) stimulation exert anti-inflammatory effects through the production of IL-10. We found that the BD disease susceptibility polymorphisms of CCR1 and IL10 loci affect the expression of these gene products in M1/M2 macrophages, leading to M1-predominant inflammation in BD (Fig. 4). We postulate that a decreased CCR1-dependent M2 macrophage migration through GWAS-identified SNPs may therefore result in augmented inflammation due to decreased IL-10 supplementation and SNP-dependent decreased IL-10 production (64).

Figure 4.

The relationship between SNP genotypes associated with Behçet’s disease and the CCR1 and IL-10 expression by M1 and M2 macrophages. A: The CCR1 mRNA expression of M1 and M2 macrophages and genotypes of SNP rs7616215 (the T allele carries a risk of Behçet’s disease), B: The IL-10 mRNA expression of M1 and M2 macrophages and genotypes of SNP rs1518111 in IL10 (the A allele carries a risk of Behçet’s disease), C: Hematoxylin and Eosin staining in BD nodular erythema, differences in the expression of the pan-macrophage marker CD68 and the M2 macrophage marker CD163 (modified from Nakano et al.64).

vi) NFκB signaling

Recently, a whole-exome analysis of familial BD identified a heterozygous germline mutation in TNFAIP3 encoding A20, a regulatory protein suppressing the NFκB signaling pathway (65). Patients with the A20 mutation exhibit constitutive NFκB activation in their leukocytes. A genetic analysis of the Mendelian form of BD would facilitate our understanding of the disease pathogenesis.

vii) Environmental factors

The phenotypic evolution of Japanese BD patients over the last 20 years may be related to environmental changes, as the genetic admixture in the Japanese population has been small over the past thousand years. The mechanisms underlying the increased intestinal BD in Japan may be similar to those underlying the increased incidence of Crohn's disease, which has been attributed to the increased dietary intake of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and animal protein in Japanese (66). Such nutritional changes in Japan may be altering the gut microbiome, resulting in an increased prevalence of IBD (67,68). A lower HLA-B*51 positivity in intestinal BD than in complete-type BD suggests that intestinal BD is a genetically distinct population (3). Although the specific environmental factors affecting the prevalence of BD are still unknown, each BD phenotype is presumably affected by different environmental factors.

Conclusion

We summarized the recent clinical and basic findings in BD. Both environmental factors and a genetic predisposition are essential for the onset of BD. Enacting measures against environmental factors, even after the onset of the disease, such as maintaining a clean oral cavity, treating periodontal disease, and stopping smoking, are important. For severe organ inflammation, early intervention with effective therapies, such as anti-TNF-α antibody, may ameliorate the cumulative organ damage caused by the disease. The identification of the characteristics and prognosis of distinct BD phenotype groups, such as intestinal BD, through national registration is necessary. Clinical trials with domestic and overseas collaboration will be important for establishing robust evidence-based therapies and disease cluster-specific therapies targeting BD.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

This study is supported by grants from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#26713036), Yokohama Foundation for Advancement of Medical Science, The Naito Memorial Foundation, The Uehara Memorial Foundation, Japan Intractable Diseases Research Foundation, Japan Rheumatic Disease Foundation, Kato Memorial Foundation for Incurable Disease, and Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science.

References

- 1. Yazici H, Seyahi E, Hatemi G, Yazici Y. Behcet syndrome: a contemporary view. Nat Rev Rheumatol 14: 119, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet's disease. N Engl J Med 341: 1284-1291, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirino Y, Ideguchi H, Takeno M, et al. Continuous evolution of clinical phenotype in 578 Japanese patients with Behçet's disease: a retrospective observational study. Arthritis Res Ther 18: 217, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ideguchi H, Suda A, Takeno M, Ueda A, Ohno S, Ishigatsubo Y. Behçet disease: evolution of clinical manifestations. Medicine (Baltimore) 90: 125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iwata D, Mizuuchi K, Aoki K, et al. Serial frequencies and clinical features of uveitis in Hokkaido, Japan. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 25: S15-S18, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mizushima Y, Inaba G, Mimura Y. Guide for the diagnosis of Behçet's disease. Report of Behçet's Disease Research Committee, Japan 8-17, 1987(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease International study group for Behçet's disease. Lancet 335: 1078-1080, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaneko F, Togashi A, Nomura E, Nakamura K. A new diagnostic way for Behçet's disease: skin prick with self-saliva. Genet Res Int 2014: 581468, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28: 338-347, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, et al. Behçet's disease: from East to West. Clin Rheumatol 29: 823-833, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kimura S, Kuroda J, Akaogi T, Hayashi H, Kobayashi Y, Kondo M. Trisomy 8 involved in myelodysplastic syndromes as a risk factor for intestinal ulcers and thrombosis-Behçet's syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 42: 115-121, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Firestein GS, Gruber HE, Weisman MH, Zvaifler NJ, Barber J, O'Duffy JD. Mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage: MAGIC syndrome. Five patients with features of relapsing polychondritis and Behçet's disease. Am J Med 79: 65-72, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwartz T, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Gazit E, Pras M, Livneh A. Behçet's disease in Familial Mediterranean fever: characterization of the association between the two diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 29: 286-295, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cho SB, Kim J, Kang SW, et al. Renal manifestations in 2007 Korean patients with Behçet's disease. Yonsei Med J 54: 189-196, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R. Autoinflammatory disease reloaded: a clinical perspective. Cell 140: 784-790, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirohata S, Kikuchi H, Sawada T, et al. Clinical characteristics of neuro-Behçet's disease in Japan: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Mod Rheumatol 22: 405-413, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verity DH, Marr JE, Ohno S, Wallace GR, Stanford MR. Behçet's disease, the Silk Road and HLA-B51: historical and geographical perspectives. Tissue Antigens 54: 213-220, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aramaki K, Kikuchi H, Hirohata S. HLA-B51 and cigarette smoking as risk factors for chronic progressive neurological manifestations in Behçet's disease. Mod Rheumatol 17: 81-82, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirohata T, Kuratsune M, Nomura A, Jimi S. Prevalence of Behçet's syndrome in Hawaii. With particular reference to the comparison of the Japanese in Hawaii and Japan. Hawaii Med J 34: 244-246, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 77: 808-818, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mizushima Y, Matsuda T, Hoshi K, Ohno S. Induction of Behçet's disease symptoms after dental treatment and streptococcal antigen skin test. J Rheumatol 15: 1029-1030, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim DY, Choi MJ, Cho S, Kim DW, Bang D. Changing clinical expression of Behçet disease in Korea during three decades (1983-2012): chronological analysis of 3674 hospital-based patients. Br J Dermatol 170: 458-461, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ono S, Aoki K, Sugiura S, Nakayama E, Itakura K. Letter: HL-A5 and Behçet's disease. Lancet 2: 1383-1384, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Menthon M, Lavalley MP, Maldini C, Guillevin L, Mahr A. HLA-B51/B5 and the risk of Behçet's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control genetic association studies. Arthritis Rheum 61: 1287-1296, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horie Y, Meguro A, Ohta T, et al. HLA-B51 Carriers are susceptible to ocular symptoms of Behçet disease and the association between the two becomes stronger towards the East along the Silk Road: a literature survey. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 25: 37-40, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 42: 703-706, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirino Y, Bertsias G, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for Behçet's disease and epistasis between HLA-B*51 and ERAP1. Nat Genet 45: 202-207, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet's disease. Nat Genet 42: 698-702, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeuchi M, Mizuki N, Meguro A, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related loci implicates host responses to microbial exposure in Behçet's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 49: 438-443, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moll JM, Haslock I, Macrae IF, Wright V. Associations between ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter's disease, the intestinal arthropathies, and Behçet's syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 53: 343-364, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, Gul A, Mahr A, Direskeneli H. 'MHC-I-opathy'-unified concept for spondyloarthritis and Behçet disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11: 731-740, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bhakta BB, Brennan P, James TE, Chamberlain MA, Noble BA, Silman AJ. Behçet's disease: evaluation of a new instrument to measure clinical activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 38: 728-733, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, et al. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behçet's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 605-613, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 77: 808-818, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yazici H, Pazarli H, Barnes CG, et al. A controlled trial of azathioprine in Behçet's syndrome. N Engl J Med 322: 281-285, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ohno S, Nakamura S, Hori S, et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of multiple administration of infliximab in Behçet's disease with refractory uveoretinitis. J Rheumatol 31: 1362-1368, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 362: 1383-1395, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hibi T, Hirohata S, Kikuchi H, et al. Infliximab therapy for intestinal, neurological, and vascular involvement in Behçet disease: efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics in a multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm phase 3 study. Medicine (Baltimore) 95: e3863, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tanida S, Inoue N, Kobayashi K, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of Japanese patients with intestinal Behçet's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 940-948.e3, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hatemi G, Melikoglu M, Tunc R, et al. Apremilast for Behçet's syndrome-a phase 2, placebo-controlled study. N Engl J Med 372: 1510-1518, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohtsuki M, Okubo Y, Komine M, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy, safety and tolerability results from a phase 2b randomized controlled trial. J Dermatol 44: 873-884, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim J, Krueger JG. Highly effective new treatments for psoriasis target the IL-23/Type 17 T cell autoimmune axis. Annu Rev Med 68: 255-269, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tang H, Jin X, Li Y, et al. A large-scale screen for coding variants predisposing to psoriasis. Nat Genet 46: 45-50, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Nakamura H, Toyoizumi S, Zwillich S. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib as monotherapy in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-week, randomized, phase 2 study. Mod Rheumatol 25: 514-521, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 357: 977-986, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium & the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2:. Strange A, Capon F, Spencer CC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat Genet 42: 985-990, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Evans DM, Spencer CC, Pointon JJ, et al. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 43: 761-767, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takeuchi M, Ombrello MJ, Kirino Y, et al. A single endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase-1 protein allotype is a strong risk factor for Behçet's disease in HLA-B*51 carriers. Ann Rheum Dis 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guasp P, Barnea E, González-Escribano MF, et al. The Behçet's disease-associated variant of the aminopeptidase ERAP1 shapes a low-affinity HLA-B*51 peptidome by differential subpeptidome processing. J Biol Chem 292: 9680-9689, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim DK, Kabat J, Borrego F, Sanni TB, You CH, Coligan JE. Human NKG2F is expressed and can associate with DAP12. Mol Immunol 41: 53-62, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science 285: 727-729, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suarez-Alvarez B, Lopez-Vazquez A, Baltar JM, Ortega F, Lopez-Larrea C. Potential role of NKG2D and its ligands in organ transplantation: new target for immunointervention. Am J Transplant 9: 251-257, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mizuki N, Ota M, Kimura M, et al. Triplet repeat polymorphism in the transmembrane region of the MICA gene: a strong association of six GCT repetitions with Behçet disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 1298-1303, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yasuoka H, Okazaki Y, Kawakami Y, et al. Autoreactive CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes to major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related gene A in patients with Behçet's disease. Arthritis Rheum 50: 3658-3662, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Erer B, Takeuchi M, Ustek D, et al. Evaluation of KIR3DL1/KIR3DS1 polymorphism in Behçet's disease. Genes Immun 17: 396-399, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kirino Y, Zhou Q, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Targeted resequencing implicates the familial Mediterranean fever gene MEFV and the toll-like receptor 4 gene TLR4 in Behçet disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 8134-8139, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang F, Liu H, Chen S, et al. Identification of two new loci at IL23R and RAB32 that influence susceptibility to leprosy. Nat Genet 43: 1247-1251, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xu H, Yang J, Gao W, et al. Innate immune sensing of bacterial modifications of Rho GTPases by the Pyrin inflammasome. Nature 513: 237-241, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Park YH, Wood G, Kastner DL, Chae JJ. Pyrin inflammasome activation and RhoA signaling in the autoinflammatory diseases FMF and HIDS. Nat Immunol 17: 914-921, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shimizu J, Kubota T, Takada E, et al. Bifidobacteria abundance-featured gut microbiota compositional change in patients with Behçet's disease. PLoS One 11: e0153746, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet 48: 481-487, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med 361: 2033-2045, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol 23: 549-555, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nakano H, Kirino Y, Takeno M, et al. GWAS-identified CCR1 and IL10 loci contribute to M1 macrophage-predominant inflammation in Behçet's disease. Arthritis Res Ther 20: 124, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhou Q, Wang H, Schwartz DM, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TNFAIP3 leading to A20 haploinsufficiency cause an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Nat Genet 48: 67-73, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shoda R, Matsueda K, Yamato S, Umeda N. Epidemiologic analysis of Crohn disease in Japan: increased dietary intake of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and animal protein relates to the increased incidence of Crohn disease in Japan. Am J Clin Nutr 63: 741-745, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kanai T, Matsuoka K, Naganuma M, Hayashi A, Hisamatsu T. Diet, microbiota, and inflammatory bowel disease: lessons from Japanese foods. Korean J Intern Med 29: 409-415, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jazayeri O, Daghighi SM, Rezaee F. Lifestyle alters GUT-bacteria function: linking immune response and host. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 31: 625-635, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fei Y, Webb R, Cobb BL, Direskeneli H, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Sawalha AH. Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci for Behçet's disease using a genome-wide association study. Arthritis Res Ther 11: R66, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hou S, Yang Z, Du L, et al. Identification of a susceptibility locus in STAT4 for Behçet's disease in Han Chinese in a genome-wide association study. Arthritis Rheum 64: 4104-4113, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee YJ, Horie Y, Wallace GR, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies GIMAP as a novel susceptibility locus for Behçet's disease. Ann Rheum Dis 72: 1510-1516, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Xavier JM, Shahram F, Sousa I, et al. FUT2: filling the gap between genes and environment in Behçet's disease? Ann Rheum Dis 74: 618-624, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kappen JH, Medina-Gomez C, van Hagen PM, et al. Genome-wide association study in an admixed case series reveals IL12A as a new candidate in Behçet disease. PLoS One 10: e0119085, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]