Abstract

Background

Wound infections are responsible for significant human morbidity and mortality worldwide. Specifically, surgical site infections are the third most commonly reported nosocomial infections accounting approximately a quarter of such infections. This systematic review and meta-analysis is, therefore, aimed to determine microbial profiles cultured from wound samples and their antimicrobial resistance patterns in Ethiopia.

Methods

Literature search was carried out through visiting electronic databases and indexing services including PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Google Scholar. Original records, available online from 2000 to 2018, addressing the research question and written in English were identified and screened. The relevant data were extracted from included studies using a format prepared in Microsoft Excel and exported to STATA 15.0 software for analyses of outcome measures and subgrouping. Der-Simonian-Laird’s random effects model was applied for pooled estimation of outcome measures at 95% confidence level. Comprehensive meta-analysis version-3 software was used for assessing publication bias across studies. The study protocol is registered on PROSPERO with reference number ID: CRD42019117638.

Results

A total of 21 studies with 4284 wound samples, 3012 positive wound cultures and 3598 bacterial isolates were included for systematic review and meta-analysis. The pooled culture positivity was found to be 70.0% (95% CI: 61, 79%). Regarding the bacterial isolates recovered, the pooled prevalence of S. aureus was 36% (95% CI: 29, 42%), from which 49% were methicillin resistant strains. The pooled estimate of E. coli isolates was about 13% (95% CI: 10, 16%) followed by P. aeruginosa, 9% (95% CI: 6, 12%), K. pneumoniae, 9% (95% CI: 6, 11%) and P. mirabilis, 8% (95% CI: 5, 11%). Compared to other antimicrobials, S. aureus has showed lower estimates of resistance against ciprofloxacin, 12% (95% CI: 8, 16%) and gentamicin, 13% (95% CI: 8, 18%). E. coli isolates exhibited the highest point estimate of resistance towards ampicillin (P = 84%; 95% CI: 76, 91%). Gentamicin and ciprofloxacin showed relatively lower estimates of resistance with pooled prevalence being 24% (95% CI: 16, 33%) and 27% (95% CI: 16, 37%), respectively. Likewise, P. aeruginosa showed the lowest pooled estimates of resistance against ciprofloxacin (P = 16%; 95% CI: 9, 24%).

Conclusion

Generally, the wound culture positivity was found very high indicating the likelihood of poly-microbial contamination. S. aureus is by far the most common bacterial isolate recovered from wound infection. The high estimate of resistance was observed among β-lactam antibiotics in all bacterial isolates. Ciprofloxacin and gentamicin were relatively effective in treating wound infections with poly-microbial etiology.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40360-019-0315-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wound infections, Bacteria, Antimicrobial resistance, Ethiopia

Background

Wound provides a warm, moist, and nutritive environment which is conducive to microbial colonization, proliferation, and infection. It can occur during trauma, accident, burn, surgical procedures or as a result of chronic disease conditions such as diabetes mellitus and leprosy [1, 2]. All wounds can be contaminated from endogenous sources of the patient (e.g. nasopharynx and gastrointestinal tract), the surrounding skin and/or the immediate environment. The local environment is particularly important for patients admitted in healthcare settings. Microbes in such wounds create a continuum from initial contamination all the way through colonization to fully blown infection. For this infection to occur, factors including the virulence characteristics of microbes, selection pressures, the host immune system, age and comorbid conditions of a patient play a critical role. Skin serves as a first line defense (innate immunity) in battle against microbes. Despite this, wound breaks the integrity of the skin, and creates an open filed for microbes thereby circumvents the innate immunity and establishes infection. It is crystal clear that wound infections have resulted in considerable morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospitalization and escalation of direct and indirect healthcare costs [3, 4].

Though it varies based on the wound source, the most commonly isolated gram-positive cocci are Staphylococcus aureus and Coagulase Negative Staphylococci (CoNS). Besides, gram-negative aerobic bacilli such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis are the most prevailing clinically relevant isolates [5–9]. Among these isolates, S. aureus particularity Methicillin resistant strains (MRSA) as well as P. aeruginosa are typical biofilm producers making the wound infection difficult to treat using standard antibiotics [3, 10–12].

Treatment of wound infections with antimicrobial agents as well as optimum treatment regimens remains ill defined. Many published guidelines are mainly based on expert opinion rather than evidence-based data. The selection of appropriate antimicrobial agents has been inconclusive. Though prophylactic use of antimicrobials can help reduce the risk of infection and promotes wound healing, it is not a direct substitute for good local wound care such as irrigation and surgical debridement. Moreover, judicious use of antimicrobials reduces the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [13–15]. Review of recent practices has revealed that potentially inappropriate and inconsistent use of antimicrobials following surgical procedures contributes to development of AMR. In addition, appropriateness of the timing, the duration, route and selection of these agents remains elusive [13, 16–18]. this systematic review and meta-analysis is aimed to provide nationwide pooled estimates of wound culture positivity, microbial profiles and AMR patterns of wound infection in Ethiopia. This will help as a benchmark for developing antimicrobial stewardship programs and generating evidence-based selection of antimicrobials thereby preserve the available antimicrobials and contain AMR.

Methods

Study protocol

The identification and screening of studies as well as eligibility assessment of full texts was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [19]. In addition, the content of this meta-analysis is well described in the completed PRISMA check list [20] (Additional file 1: Table S1). The study protocol is registered on International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with reference number ID: CRD42019117638 and available online at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019117638

Data sources and searching strategy

Literature search was carried out through visiting electronic databases and indexing services. The PubMed, MEDLINE (Ovid®), EMBASE (Ovid®), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Google Scholar, were used as main source of data. Besides, other supplementary sources including ResearchGate, WorldCat, Science Direct and University repositories were searched to retrieve relevant data. Excluding the non-explanatory terms, the search strategy included important keywords and indexing terms: wound, wound infection (MeSH), “antimicrobial susceptibility”, bacteria (MeSH), “antimicrobial resistance”, “antibacterial resistance”, and “Ethiopia”. The MeSH terms, Boolean operators (AND, OR and NOT), and truncation were applied for appropriate searching and identification of records for the research question.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies conducted in Ethiopia

Studies available online from 2000 to 2018

Studies published in English language

Laboratory-based observational (e.g. cross-sectional) studies addressing the research question: studies dealing with wound culture positivity and prevalence of individual isolates recovered from wound samples as primary outcome measures

Exclusion criteria

Any review papers published in the study period

Studies having mixed sample sources (wound and non-wound samples concurrently. E.g. blood, urine, and other discharges)

Wound samples taken from animals

Irretrievable full texts (after requesting full texts from the corresponding authors via email and/or Research Gate account)

Studies with unrelated or insufficient outcome measures

Studies with outcomes of interest are missing or vague

Screening and eligibility of studies

Along with application of appropriate limits, online records from each database or directory were exported to ENDNOTE reference software version 8.2 (Thomson Reuters, Stamford, CT, USA). The records were then merged to one folder to identify and remove duplicates with the help of ENDNOTE and/or manual tracing as there is a possibility of several citation styles per study. Thereafter, two authors Mekonnen Sisay (MS) and Dumessa Edessa (DE) independently screened the title and abstracts with the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Records which passed the screening phase were subjected for eligibility assessment of full texts. For this, two authors, MS and Teshager Worku (TW) independently collected full texts and evaluated their eligibility for meta-analysis. In each case, the third author was consulted to solve disagreement occurred between the two authors.

Data extraction

Using standardized data abstraction format prepared in Microsoft Excel (Additional file 2: Table S2), the authors independently extracted important data related to study characteristics (study area, first author, year of publication, study design, population characteristics, nature of wound samples) and outcome of interests (culture positivity, nature of bacterial isolates, prevalence of bacterial isolates and resistance profile of individual isolates).

Critical appraisal of studies

The quality of studies was assessed using standard critical appraisal tools prepared by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), at University of Adelaide, Australia [21]. The purpose of this appraisal is to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. The JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data contains nine important questions (Q1-Q9) and primarily addresses the methodological aspects of each study. This critical appraisal was conducted to assess the internal (systematic error) and external validity of studies thereby reduces the risk of biases among individual studies. Scores of the two authors (MS and DE) in consultation with third author (TW) (in case of disagreement between the two authors’ appraisal result) were taken for final decision. Studies with the number of positive responses (yes) greater than half of the number of checklists (i.e., score of five and above) were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome measures are the culture positivity of wound samples and the prevalence of bacterial isolates recovered from infected wound samples in Ethiopia. The secondary outcome measure is the antimicrobial resistance profiles of clinically relevant bacterial isolates against commonly prescribed antimicrobial agents taken from different pharmacologic categories (penicillins, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, fluroquinolones, macrolides and sulfonamides). Subgroup analysis was also conducted based on the nature of wound sources (surgical, burn and other non-surgical wounds).

Data processing and analysis

The extracted data were imported from Microsoft Excel to STATA software, version 15.0 for the pooled estimation of outcome measures. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were also conducted to minimize the degree of heterogeneity. Der-Simonian-Laird’s random effects model was applied for the analysis at 95% confidence level. Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed with I2 statistics. Forest plots and summary tables were used to report the results. Comprehensive Meta-analysis software version-3, (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA), was employed for assessment of publication bias. The presence of publication bias was evaluated by using Egger’s regression and Begg’s and Mazumdar’s correlation tests and presented with funnel plot. All statistical tests with p-values less than 0.05 (one-tailed) were considered significant [22, 23].

Results

Search results

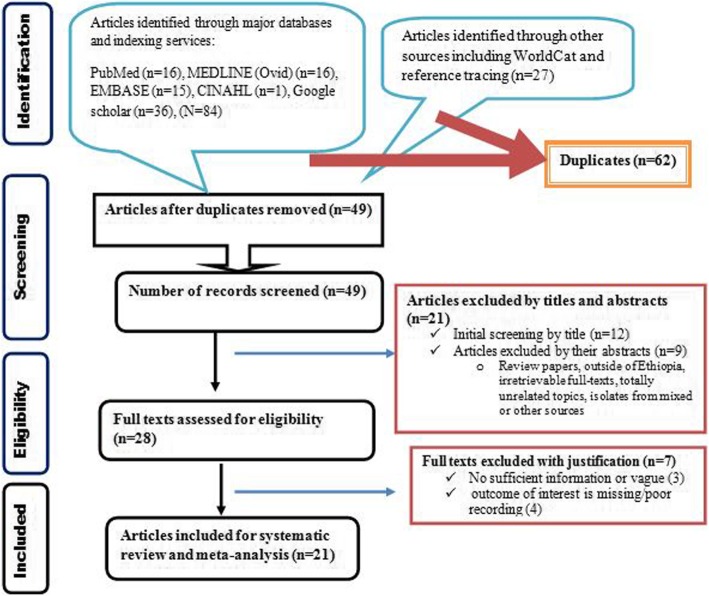

A literature search in electronic databases including PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Google Scholar retrieved a total of 111 studies. From which, 62 studies were found duplicate through ENDNOTE and manual tracing. The remaining studies were screened using their titles and abstracts and 21 of them did not fulfill the inclusion criteria and thus removed from further eligibility study. The full texts of 28 studies were thoroughly assessed to ensure the presence of at least the primary outcome measures in sufficient and non-ambiguous way. In this regard, 7 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and thus removed from final inclusion. Therefore, 21 studies addressing the outcome of interest were included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting the selection process

Results of quality assessment

Having fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria, further rigorous appraisal of individual study was conducted using JBI checklist with the average quality score ranging between 6 and 9. Finally, the 21 studies were included for systematic review and meta-analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality assessment of studies using JBI’s critical appraisal tools designed for cross-sectional studies

| Studies | JBI’s critical appraisal questions | Overall score | Include | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | |||

| Abraham and Wamisho., 2009 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | 7 | ✓ |

| Alebachew et al., 2012 | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 | ✓ |

| Asres et al., 2017 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Azene et al., 2011 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Bitew et al., 2018 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Desalegn et al., 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Dessie et al., 2016 | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Gelaw et al., 2014 | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Godebo et al., 2013 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Guta et al., 2014 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Hailu et al., 2016 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Kahsay et al., 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 | ✓ |

| Kiflie et al., 2018 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Lema et al., 2012 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Mama et al., 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 | ✓ |

| Mengesha et al., 2014 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Mohammed et al., 2014 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Mulu et al., 2006 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Mulu et al., 2017 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | ✓ |

| Sewnet et al., 2013 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | ✓ |

| Tekie, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 | ✓ |

Y Yes, N No, U Unclear, Q Question. Overall score is calculated by counting the number of Ys in each row

Q1 = Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? Q2 = Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? Q3 = Was the sample size adequate? Q4 = Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? Q5 = Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? Q6 = Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? Q7 = Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? Q8 = Was there appropriate statistical analysis? Q9 = Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?

Study characteristics

Twenty one studies with a total of 4284 wound samples, 3012 positive cultures and 3598 bacterial isolates were included for systematic review and meta-analysis. This review included a wide range of wound samples taken from various patient sources including patients surgical wounds [24–32], patients with non-surgical and/or combined wound infections [33–40], patients with fracture [41], patients with burn [42, 43], and patients with leprotic wound infections [44]. The study period of included studies ranges from 2000 to 2018 and three of which were published before 2010 [30, 39, 41]. Regarding the study design, all of them are laboratory based cross-sectional studies with four of them being a retrospective chart review [33, 36, 39, 40]. The number of wound samples, positive cultures and bacterial isolates ranges from 50 [43] to 599 [33], 21 [43] to 422 [33] and 47 [43] to 500 [33], respectively. Two studies have only recovered S. aureus isolates from positive cultures of wound swabs [28, 42]. With exception of three studies which were conducted in regional laboratories [33, 34, 36], all the rest studies were conducted in specialized and/or teaching hospitals of Ethiopian universities. Table 2 has also summarized the number of clinically relevant gram-positive (S. aureus and CoNS) and gram-negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis) bacterial isolates recovered from positive cultures of wound samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies describing the magnitude of culture positive wound samples and microbial profiles of clinical relevant bacterial isolates in Ethiopia (2000–2018)

| Studies | Year of publication | Study setting | Total patients (M/F ratio) | Study characteristics | Wound samples | Culture positive | No of isolates | Gram-positive | Gram -negative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | CoNS | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | K. pneumoniae | P. mirabilis | ||||||||

| Abraham and Wamisho [41] | 2009 | TASH, AA | 191 (158/33) | Fracture in-and outpatients | 200 | 196 | 162 | 24 | 12 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 6 |

| Alebachew et al. [42] | 2012 | Yekatit 12 hospital | 114 (58/56) | Burn in-and outpatients | 114 | 95 | 114 | 65 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Asres et al. [24] | 2017 | TASH, AA | 197 (118/79) | Postoperative in-and outpatients | 197 | 149 | 168 | 56 | 19 | 24 | 8 | 15 | 2 |

| Azene et al. [33] | 2011 | Dessie regional laboratory | 12599 (368/231) | Outpatients with any wound | 599 | 422 | 500 | 208 | 9 | 82 | 92 | 12 | 55 |

| Bitew et al. [34] | 2018 | Arsho medical laboratory | 366 (213/153) | Both in-and Patients with wound | 366 | 271 | 271 | 110 | 11 | 49 | 14 | 12 | 7 |

| Desalegn et al. [25] | 2014 | Hawassa TRH | 194 (116/78) | Post-surgical in and outpatients | 194 | 138 | 177 | 66 | 6 | 45 | 18 | 24 | 18 |

| Dessie et al. [31] | 2016 | St. Paul and Yekatit 12 hosp. | 107 (56/51) | Surgical inpatients | 107 | 90 | 104 | 19 | 4 | 24 | 6 | 10 | 1 |

| Gelaw et al. [26] | 2014 | UoG TH | 42 (27/15) | Surgical inpatients | 142 | 42 | 49 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 9 |

| Godebo et al. [35] | 2013 | JUSH | NS | Out/inpatients with wound | 322 | 310 | 384 | 73 | 14 | 30 | 74 | 46 | 107 |

| Guta et al. [27] | 2014 | HUTRH | 100 (37/63) | Surgical inpatients | 100 | 92 | 177 | 45 | 26 | 30 | 16 | 32 | 12 |

| Hailu et al. [36] | 2016 | Bahir Dar RHRL | 234 (131/103) | Both in-and outpatients with wound | 380 | 234 | 234 | 100 | ND | 33 | 26 | 20 | 22 |

| Kahsay et al. [28] | 2014 | DMRH | 184 (61/123) | Surgical inpatients | 184 | 73 | 184 | 72 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Kiflie et al. [32] | 2018 | UoG TH | 107 (0/107 | Women with cesarean section or episiotomy | 107 | 90 | 101 | 42 | 13 | 20 | 1 | 14 | 1 |

| Lema et al. [44] | 2012 | Selected Hospitals, AA | 245 (157/88) | In-and outpatients with leprosy | 245 | 222 | 298 | 68 | 18 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 47 |

| Mama et al. [37] | 2014 | JUSH | 150 (107/43) | In/outpatients with wound | 150 | 131 | 145 | 47 | 21 | 29 | 11 | 14 | 23 |

| Mengesha et al. [29] | 2014 | Ayder TRH | 128 (98/30) | Surgical inpatients | 128 | 96 | 123 | 40 | 18 | 6 | 11 | 29 | 15 |

| Mohammed et al. [38] | 2014 | UoG RH | 137 (81/56) | In/outpatients with wound | 137 | 115 | 136 | 39 | 17 | 8 | 8 | 17 | 6 |

| Mulu et al. [39] | 2006 | UoGTH | NS | In/outpatients with wound | 151 | 79 | 79 | 51 | ND | 8 | ND | 7 | 3 |

| Mulu et al. [40] | 2017 | DMRH | 238 (NS) | In/outpatients with wound | 238 | 115 | 90 | 70 | ND | 5 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Sewnet et al. [43] | 2013 | Yekatit 12 hospital | 50 (30/20) | In/outpatients with burn case | 50 | 21 | 47 | 16 | 6 | ND | 15 | 1 | 4 |

| Tekie [30] | 2008 | TASH | 173 (97/76) | Outpatients with surgical wound | 173 | 31 | 55 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 4284 | 3012 | 3598 | ||||||||||

M Male, F Female, CoNS Coagulase negative Staphylococci, ND Not determined, JUSH Jimma University Specialized Hospital, UoGTH University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Hawassa University Teaching and Referral Hospital, CS Cross-sectional, R Retrospective, TASH Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital, AA Addis Ababa, DMRH Debre Markos Referral Hospital, NS Not specified

Besides, the antimicrobial resistance profiles of six clinical isolates (two from gram-positive and four from gram-negative bacteria) were summarized against commonly prescribed antimicrobial agents taken from various pharmacologic classes: penicillins (amoxicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and methicillin), cephalosporins (ceftriaxone), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), marcrolides (erythromycin), sulfonamides (cotrimoxazole) and aminoglycosides (gentamicin). Unlike others, a study conducted by Hailu et al. utilized variable number of bacterial isolates per antimicrobial agent [36]. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of gram-negative isolates was conducted against erythromycin in two studies [29, 33] though not found suitable for meta-analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns of clinically relevant bacterial isolates from wound infection in Ethiopia

| Types of Bacteria | Studies | Number of isolates | Number of isolates resistant to | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMO | AMC | AMP | CIP | CRO | SXT | ERY | GEN | MET | |||

| S. aureus | Abraham and Wamisho | 24 | 9 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Alebachew et al | 66 | – | 22 | – | – | 23 | – | 9 | – | 51 | |

| Asres et al. | 56 | – | 9 | – | 7 | – | 19 | 9 | 7 | 6 | |

| Azene et al | 208 | 165 | – | – | 18 | 37 | 140 | 72 | 26 | 22 | |

| Bitew et al | 110 | – | – | – | 7 | – | 30 | 70 | 2 | – | |

| Kiflie et al | 42 | 28 | – | 30 | – | 15 | 26 | – | – | 22 | |

| Desalegn et al | 66 | 20 | 63 | 26 | 54 | 37 | 29 | 26 | – | ||

| Dessie et al | 19 | – | – | – | 3 | – | 4 | 4 | 3 | – | |

| Godebo et al | 73 | – | – | 67 | 10 | 15 | 44 | 58 | 12 | 57 | |

| Guta et al | 45 | 45 | – | – | – | 16 | – | – | 9 | – | |

| Hailu et al | NDA | – | – | – | 5(67) | – | 16 (94) | 30 (96) | – | 20 (95) | |

| Kahsay et al | 73 | 13 | – | 13 | – | – | 1 | – | 9 | 36 | |

| Lema et al | 68 | 45 | 8 | 58 | 6 | – | 23 | 20 | 5 | 50 | |

| Mama et al | 47 | – | – | 45 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 2 | – | |

| Mengesha et al | 40 | 37 | 20 | 36 | – | 36 | – | 9 | 4 | 34 | |

| Mohammed et al | 39 | 34 | – | – | 8 | 8 | 15 | 24 | 7 | 30 | |

| Mulu et al., 2006 | 51 | – | – | 28 | – | – | 18 | – | – | – | |

| CoNS | Abraham and Wamisho | 12 | 1 | – | 4 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 2 | |

| Asres et al. | 19 | – | 15 | – | 5 | – | 14 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Kiflie et al | 13 | 11 | – | 11 | – | 5 | 8 | – | – | ||

| Desalegn et al | 6 | – | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Dessie et al | 4 | – | – | – | 4 | – | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Godebo et al | 14 | – | – | 9 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Guta et al | 26 | 4 | – | – | – | 13 | – | – | 13 | ||

| Lema et al | 18 | 6 | – | 12 | 1 | – | 9 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Mama et al | 21 | – | – | 19 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Mengesha et al | 18 | 16 | 14 | 14 | – | 13 | – | 9 | 9 | ||

| Mohammed et al | 16 | 13 | – | – | 3 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 3 | ||

| E. coli | Abraham and Wamisho | 17 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | – | 2 | |

| Asres et al. | 24 | 20 | 14 | – | 5 | – | 15 | – | 7 | ||

| Azene et al | 82 | 70 | – | – | 21 | 55 | 55 | 43 | 12 | ||

| Bitew et al | 49 | – | 35 | 35 | 5 | 10 | 22 | – | 5 | ||

| Kiflie et al | 20 | 14 | – | 16 | 4 | 12 | 10 | – | 7 | ||

| Desalegn et al | 45 | – | 21 | 45 | 18 | 18 | 27 | – | 21 | ||

| Dessie et al | 24 | – | 17 | 23 | 16 | 20 | – | – | 13 | ||

| Godebo et al | 30 | – | – | 23 | 1 | 20 | 6 | – | 0 | ||

| Guta et al | 30 | 20 | – | – | – | 10 | – | – | 0 | ||

| Hailu et al | NDA | – | 24 (33) | 31 (33) | 15 (33) | 6 (24) | 23 (30) | – | 18 (33) | ||

| Lema et al | 14 | 10 | 7 | 9 | – | – | 9 | – | – | ||

| Mama et al | 29 | – | – | 29 | 10 | 18 | 16 | – | 15 | ||

| Mengesha et al | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 4 | – | 2 | – | ||

| Mohammed et al | 8 | – | – | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | – | 1 | ||

| Mulu et al., 2006 | 8 | – | – | 7 | – | – | 5 | – | – | ||

| P. aeruginosa | Abraham and Wamisho | 16 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 5 | 11 | – | 2 | |

| Asres et al. | 8 | 8 | 7 | – | 1 | – | 7 | – | 2 | ||

| Azene et al | 92 | 76 | – | – | 4 | 47 | 71 | 83 | 7 | ||

| Bitew et al | 14 | – | 14 | 14 | 1 | 11 | 9 | – | 1 | ||

| Desalegn et al | 18 | – | 18 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 12 | – | 9 | ||

| Dessie et al | 6 | – | 6 | 6 | 2 | 5 | – | – | 0 | ||

| Godebo et al | 74 | – | – | 72 | 4 | 7 | 65 | – | 8 | ||

| Guta et al | 16 | 16 | – | – | – | 8 | – | – | 8 | ||

| Hailu et al | NDA | – | – | – | 5 (26) | – | 3 (9) | – | 7 (23) | ||

| Lema et al | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | – | – | 7 | – | 1 | ||

| Mama et al | 11 | – | – | 11 | – | 7 | 8 | – | 2 | ||

| Mengesha et al | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 11 | – | 3 | – | ||

| Mohammed et al | 8 | – | – | – | 3 | 3 | – | – | 3 | ||

| Tekie | 8 | – | – | – | 6 | 4 | 7 | – | 3 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | Abraham and Wamisho | 12 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 3 | – | 3 | |

| Asres et al. | 15 | 14 | 12 | – | 4 | 13 | 13 | – | 9 | ||

| Azene et al | 12 | 12 | – | – | – | – | 8 | – | 0 | ||

| Bitew et al | 12 | – | 12 | 12 | 2 | 7 | 5 | – | 2 | ||

| Kiflie et al | 14 | 14 | – | 14 | 2 | 8 | 9 | – | 3 | ||

| Desalegn et al | 24 | – | 12 | 21 | 15 | 21 | 21 | – | 24 | ||

| Dessie et al | 10 | – | 10 | 10 | 2 | 9 | – | – | 4 | ||

| Godebo et al | 46 | – | – | 32 | 13 | 13 | 30 | – | 13 | ||

| Guta et al | 32 | 25 | – | – | – | 9 | – | – | 12 | ||

| Hailu et al | NDA | – | 10 (20) | 15 (20) | 4 (20) | 2 (18) | 8 (20) | – | 11 (18) | ||

| Mama et al | 14 | – | – | 14 | 5 | 10 | 12 | – | 9 | ||

| Mengesha et al | 29 | 29 | 19 | 26 | 11 | 25 | – | 13 | 8 | ||

| Mohammed et al | 17 | – | – | 16 | 10 | 9 | 11 | – | 5 | ||

| P. mirabilis | Abraham and Wamisho | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – | 0 | |

| Azene et al | 55 | 48 | – | – | 9 | 35 | 45 | 51 | 5 | ||

| Bitew et al | 7 | – | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | – | 2 | ||

| Desalegn et al | 18 | – | 9 | 18 | 0 | 6 | 3 | – | 6 | ||

| Godebo et al | 107 | – | – | 77 | 8 | 8 | 81 | – | 35 | ||

| Guta et al | 12 | 11 | – | – | – | 8 | – | – | 6 | ||

| Hailu et al | NDA | – | 12 (22) | 17 (22) | 5 (22) | 8 (18) | 7 (17) | – | 5 (22) | ||

| Lema et al | 47 | 24 | 20 | 31 | 4 | – | 21 | – | 4 | ||

| Mama et al | 23 | – | – | 21 | 4 | 15 | 9 | – | 6 | ||

| Mengesha et al | 15 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 11 | – | 9 | 3 | ||

| Mohammed et al | 6 | – | – | 6 | 2 | 1 | 5 | – | 2 | ||

---, Not tested, NDA Number of isolates is different among antimicrobial agents tested as indicated in parenthesis of the corresponding rows, AMO Amoxicillin, AMP Ampicillin, AMC Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, SXT Cotrimoxazole, CRO Ceftriaxone, CIP Ciprofloxacin, GEN Gentamicin, ERY Erythromycin

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures: culture positivity and microbial epidemiology

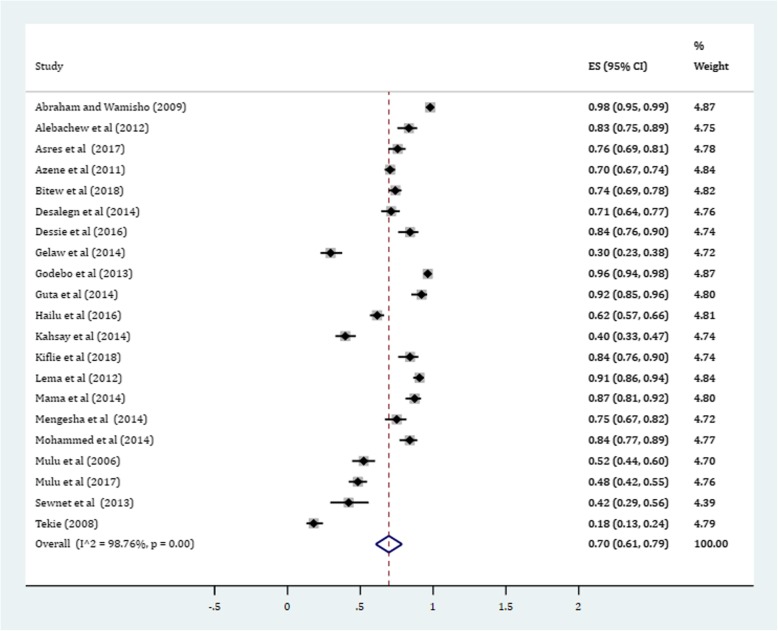

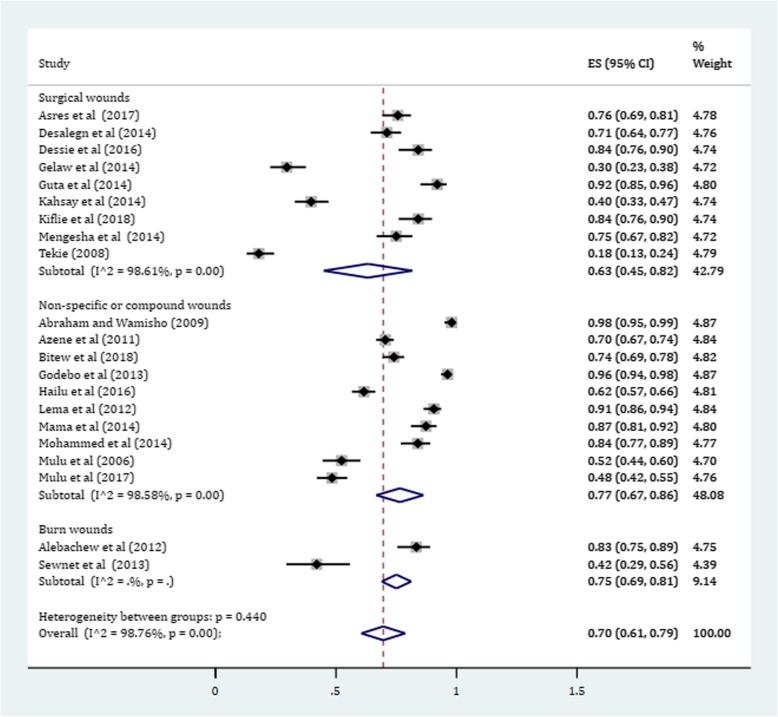

In this meta-analysis, a total of 3012 positive bacterial cultures obtained from 4284 wound samples were included. The pooled prevalence of culture positive cases from all wound samples was found to be 70.0% (95% CI: 61, 79%) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis was conducted to determine whether there is a potential difference of culture positivity among wound sources. Based on this, the prevalence of culture positive samples in non-specific non-surgical simple or compound wounds was estimated about 77% (95% CI: 67, 86%). Likewise, the prevalence of cultures with bacterial growth among burn wounds was estimated 75% (95% CI: 69, 81%). In surgical wounds, a relatively lower culture positivity rate was obtained with a pooled estimate being 63% (95% CI: 45, 82%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot depicting culture positivity among wound sample in Ethiopia

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing subgroup analysis of culture positivity based on wound sources

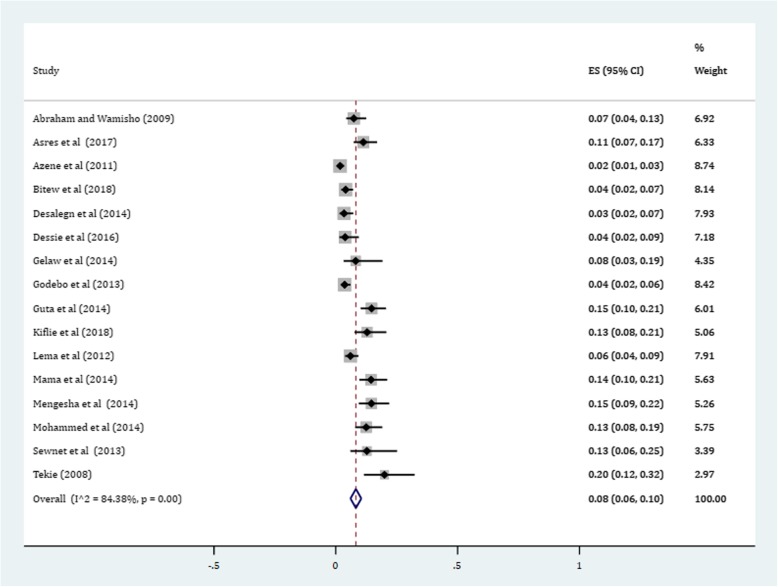

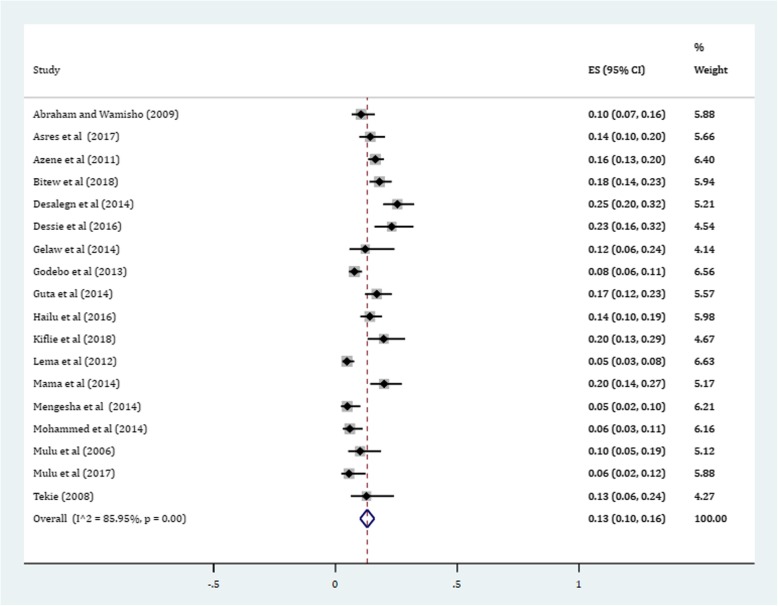

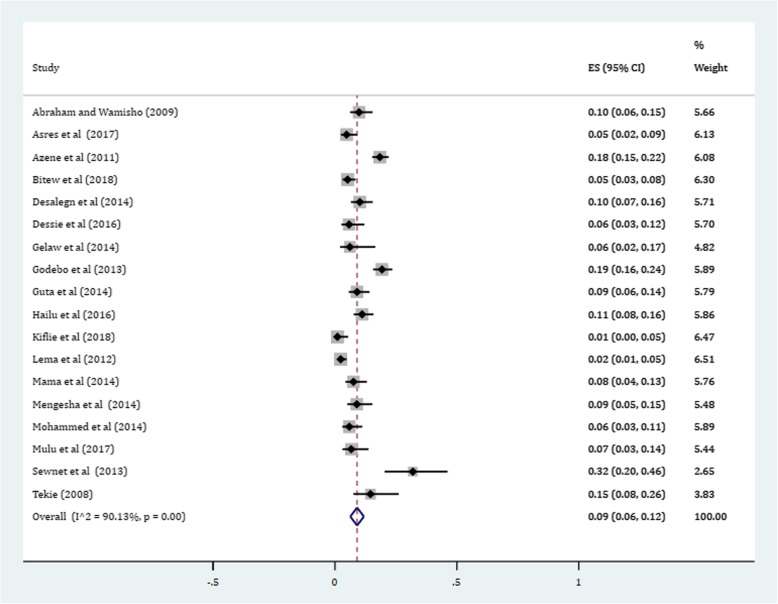

Gram-positive cocci were a predominant isolates recovered. The pooled prevalence of S. aureus was 36% (95% CI: 29, 42%) (Fig. 4). The prevalence of CoNS isolates from wound samples was estimated to be 8% (95% CI: 6, 10%) (Fig. 5). With regard to gram-negative aerobic bacilli, the pooled estimates of E. coli isolates from all isolates of wound samples was found to be 13% (95% CI: 10, 16%) (Fig. 6) followed by P. aeruginosa, 9% (95% CI: 6, 12%) (Fig. 7), K. pneumoniae, 9% (95% CI: 6, 11%) (Fig. 8) and P. mirabilis, 8% (95% CI: 5, 11%) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of S. aureus in wound samples

Fig. 5.

Pooled estimate of CoNS in wound samples in Ethiopia

Fig. 6.

Pooled estimates of E. coli in wound samples

Fig. 7.

Forest plot depicting the pooled prevalence of P. aeruginosa in wound samples

Fig. 8.

Pooled estimates of K. pneumoniae in wound samples

Fig. 9.

Pooled estimate of P. mirabilis

Secondary outcome measures: antimicrobial resistance patterns

Among S. aureus isolates, the prevalence of Methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains was found to be 49% (95% CI: 31, 68%). The combination of amoxicillin with β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid (Coamox-clav) reduced the amoxicillin resistance by 42% (P = 27%; 95% CI: 16, 38%). Besides, the pooled estimates of amoxicillin and ampicillin resistance among CoNS isolates were 62% (95% CI: 34, 90%) and 72% (95% CI: 57, 87%), respectively. Among all antimicrobial agents tested, S. aureus exhibited relatively lower estimates of resistance against ciprofloxacin, 12% (95% CI: 8, 16%) and gentamicin, 13% (95% CI: 8, 18%). Likewise, ciprofloxacin had the least resistant isolates (P = 13%; 95% CI: 4, 23%) followed by gentamicin (P = 33%; 95% CI: 17, 50) for CoNS. The 3rd generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone resistance was observed among gram-positive isolates with estimates being 36% (95% CI: 17, 55%) and 37% (95% CI: 19, 54) for S. aureus and CoNS, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pooled estimates of antimicrobial resistance among Gram-positive bacteria obtained from wound samples in Ethiopia

| Antimicrobial agents | Pooled estimates of resistant isolates (Proportion) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | CoNS | |||

| Pooled ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Pooled ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| AMO | 0.69 (0.50, 0.87) | 97.64 | 0.62 (0.34, 0.90) | 93.05 |

| AMC | 0.27 (0.16, 0.38) | 81.35 | NA | – |

| AMP | 0.76 (0.60, 0.92) | 97.17 | 0.72 (0.57,0.87) | 70.85 |

| CIP | 0.12 (0.08, 0.16) | 72.39 | 0.13 (0.04, 0.23) | 65.46 |

| CRO | 0.36 (0.17, 0.55) | 97.23 | 0.37 (0.19, 0.54) | 81.58 |

| SXT | 0.35 (0.20, 0.49) | 97.64 | 0.49 (0.31, 0.66) | 75.21 |

| ERY | 0.34 (0.22, 0.46) | 94.69 | 0.40 (0.20, 0.40) | 90.05 |

| GEN | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) | 82.90 | 0.33 (0.17, 0.50) | 88.16 |

| MET | 0.49 (0.31, 0.68) | 94.50 | NA | – |

AMO Amoxicillin, AMP Ampicillin, AMC Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, SXT Cotrimoxazole, CRO Ceftriaxone, CIP Ciprofloxacin, GEN Gentamicin, MET Methicillin, ERY Erythromycin, NA Not analyzed: CoNS, Coagulase negative Staphylococci

Regarding the AMR profiles of gram-negative pathogens, E. coli isolates exhibited the highest point estimate of resistance against ampicillin (P = 84%; 95% CI: 76, 91%) followed by amoxicillin (P = 73%; 95% CI: 63, 83%). Gentamicin and ciprofloxacin showed relatively lower estimates of resistance with pooled prevalence being 24% (95% CI: 16, 33%) and 27% (95% CI: 16, 37%), respectively. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination reduced the amoxicillin resistance of E. coli by 16% (P = 57%; 95% CI: 44, 70%). Nearly half (P = 45%; 31, 60%) and more than half (P = 53%; 95% CI: 43, 64%) of E. coli isolates were found resistant to ceftriaxone and cotrimoxazole, respectively in wound samples in Ethiopia (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pooled estimates of antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacterial isolates obtained from wound samples in Ethiopia

| Antimicrobials | Pooled estimates of resistant isolates (Proportion) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa | K. pneumoniae | P. mirabilis | |||||

| ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| AMO | 0.73 (0.63, 0.83) | 55.70 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.92) | 0.00 | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) | 43.97 | 0.75 (0.57, 0.93) | 86.81 |

| AMC | 0.57 (0.44, 0.70) | 74.51 | 0.77 (0.63, 0.91) | 63.67 | 0.67 (0.51, 0.83) | 78.01 | 0.45 (0.36, 0.54) | 19.01 |

| AMP | 0.84 (0.76, 0.91) | 75.08 | 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.00 | 0.88 (0.83, 0.93) | 24.27 | 0.78 (0.70, 0.85) | 39.67 |

| CIP | 0.27 (0.16, 0.37) | 86.99 | 0.16 (0.09, 0.24) | 87.63 | 0.29 (0.15, 0.42) | 85.50 | 0.12 (0.06, 0.19) | 73.68 |

| CRO | 0.45 (0.31, 0,60) | 89.81 | 0.58 (0.35, 0.82) | 95.86 | 0.57 (0.39, 0.75) | 92.32 | 0.43 (0.24, 0.63) | 94.04 |

| SXT | 0.53 (0.43, 0.64) | 75.91 | 0.76 (0.68, 0.85) | 51.82 | 0.64 (0.51, 0.77) | 76.58 | 0.56 (0.39, 0.72) | 88.19 |

| GEN | 0.24 (0.16, 0.33) | 93.09 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.26) | 66.47 | 0.37 (0.22, 0.52) | 89.66 | 0.21 (0.12, 0.30) | 74.31 |

AMO Amoxicillin, AMP Ampicillin, AMC Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, SXT Cotrimoxazole, CRO Ceftriaxone, CIP Ciprofloxacin, GEN Gentamicin

Though it has become clinical concerning, the difficult to treat gram-negative bacteria P. aeruginosa showed the lowest pooled estimates of resistance against ciprofloxacin (P = 16%; 95% CI: 9, 24%, I2 = 87.63). Only 10% reduction in overall resistance was observed in amoxicillin-clavulanate (P = 77; 95% CI: 63, 91%) compared to amoxicillin alone (P = 87%; 95% CI: 82, 92%) in P. aeruginosa isolates.. More than half of P. aeruginosa isolates (P = 58%; 95% CI: 35, 82%) developed resistance to ceftriaxone. Moreover, around three-fourths of these isolates (P = 76%; 95% CI: 68, 85%) were found resistant to cotrimoxazole (Table 5).

The AMR profiles of the two more gram-negative aerobic bacilli (K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis) were also tested against seven antimicrobial agents. The antimicrobials with highest estimates of resistance were found to be amoxicillin and ampicillin in both bacterial isolates. Ciprofloxacin followed by gentamicin were antimicrobials having lower point estimates of resistance in both types of isolates. More than half of K. pneumoniae isolates exhibited ceftriaxone resistance (P = 57%; 95% CI: 39, 75%) (Table 5).

Publication bias

Funnel plots of standard error with log of the prevalence of positive bacterial cultures revealed that there is some evidence of publication bias (Begg’s and Mazumdar’s test, p-value =0.0067; Egger’s test, p-value = 0.048) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Funnel plot showing publication bias of included studies

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, more than two-thirds of wound samples (70%) were found culture positive. The subgroup analysis has also indicated higher culture positivity of burn and other non-surgical wounds compared to surgical wounds regardless of prophylactic antibiotic status. In concordant with this, a five year study conducted by Agnihotri et al reported high culture positivity (96%) from burn wound infections [6]. Besides, a summary of wound infection in orthopedics revealed that the overall culture positivity rate was estimated to be 53% [45]. The lower culture positivity of surgical wounds, as observed in subgroup analysis, might be due to the nature of surgical care (i.e. irrigation, debridement and use of prophylactic antibiotics in some cases). The most common bacterial isolate recovered from wound infection was S. aureus with pooled estimate being 36% which is by far higher than the prevalence of CoNS, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae and other gram-negative aerobic bacilli. This is further supported by several published studies which reported that gram-positive aerobic cocci, particularly, Staphylococci, have been the primary cause of wound infections [3–5, 7–9, 46–50]. More specifically, S. aureus has been a single most common pathogen isolated from several wound samples [46–49, 51]. With regard to gram-negative pathogens, the highly prevailing clinically relevant bacterial isolates were aerobic bacilli under Enterobacteriaceae including E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis. This finding is in trajectory with review of recent literature in different settings [14, 45, 48, 52].

Though it seems controversial, many studies indicated that the two highly prevalent bacterial isolates recovered from chronic wound infections were S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [3, 12, 15, 49, 51, 53, 54]. Nevertheless, a review report conducted by Macedo and Santos on burn wound infections showed that S. aureus was the most prevalent in the first week of wound infection with an overall prevalence of about 28.4%. It was, however, surpassed by P. aeruginosa from the third week onwards [55]. On the top of these, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa are opportunistic pathogenic bacteria and are widely known to cause chronic biofilm-based wound infections [51]. These pathogens are capable of making a strong biofilm that maintains the chronic infection which impairs wound healing [3, 53]. To this end, a meta-analysis of published data revealed that about 78% of non-healing chronic wounds harbor biofilms, with prevalence rates varying between 60 and 100% [12].

The overall prevalence of MRSA strains was found to be 49% indicating one in every two S. aureus isolates were characterized as MRSA strains. This is a clear direction of how high the healthcare settings become a reservoir of resistant strains like MRSA. Likewise, a summary of wound infections in orthopedics indicated that S. aureus constituted about 34% of all isolates and 48% of this isolate were reported to be MRSA [45]. Conditions such as hospitalization, prophylactic use of antimicrobials in surgical procedures and use of broad spectrum antimicrobials predispose patients for such resistant strains [3]. The rapid development and spread of MRSA clones across the globe often results in such hospital outbreaks [56, 57].

Due to β- lactamase producing capability and modification of penicillin binding proteins, S. aureus has developed resistance to majority of β-lactam antibiotics (mainly penicillins and cephalosporins). As the analysis tried to address, the third generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone resistance was estimated to be 36%. Though it is less pathogenic than S. aureus, CoNS had also developed closer estimates of resistance in these antibiotics. Most notably, the steady erosion of the effectiveness of β-lactam antibiotics for treatment of S. aureus infection is due to the fact that it’s extraordinary adaptability in developing resistance with several mechanisms [10, 56, 57]. Gram-positive cocci particularly Staphylococci such as S. aureus produce β-lactamase enzymes which in turn degrade the β-lactam ring of majority of β-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams) and make these drugs devoid of any antibacterial activity. Though they have a wide range of bacterial coverage, the β-lactamase sensitivity of broad (ampicillin and amoxicillin) and extended spectrum (antipseudomonal) penicillins are no longer effective for β-lactamase producing Staphylococci such as S. aureus [6, 14, 56, 58]. To this end, the use of combination of β-lactamase enzyme inhibitors (e.g. clavulanic acid, sulbactam, tazobactam) with these sensitive β-lactam antibiotics has been somehow a notable strategy in combating resistance against strains constitutionally producing these enzymes. In this study, combination of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (Coamox-clav) reduced the pooled estimates of amoxicillin resistance from 69 to 27% clearly indicating the involvement of these enzymes in resistance development. This finding is in trajectory with a 5-year study conducted by Agnihotri et al. in which S. aureus showed high estimate of resistance (about 75%) to standard β-lactam antibiotics whereas coamox-clav resistance was reduced to 23.5% [6].

Moreover, S. aureus has also developed resistant to β-lactamase resistant penicillins (methicillin, naficillin, oxacillin, cloxacillin and diclocoxacillin) with apparently different mechanism. From experience, resistant to these agents was historically treated as MRSA since the first agent in this class of penicillins is methicillin [59–61]. S. aureus acquires resistance genes which encode a modified form of penicillin binding proteins (PBP). In MRSA, the horizontally acquired mecA gene encodes PBP2A. PBP2 is the only bifunctional PBP in S. aureus. In MRSA strains, the essential function of PBP2 may be replaced by PBP2A which functions as a surrogate transpeptidase. Since almost all β-lactams have little or no affinity to this protein, cross resistance occurs regardless of β-lactamase stability status [57, 60]. This is a likely justification why more-than one-thirds of S. aureus strains were found resistant to ceftriaxone. Apart from this, macrolides (erythromycin) and sulfa drugs (cotrimoxazole) resistance was observed in about one-thirds of S. aureus strains. Generally, this study showed that more than 10% of S. aureus isolates were also resistance to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin. CoNS had also showed higher gentamicin resistance than S. aureus.

Observing the AMR profile of gram-negative bacteria, a high estimate of resistance was observed in β-lactam antibiotics. All gram-negative bacilli have developed clinically significant resistant against broad spectrum penicillins (amoxicillin and ampicillin). The combination of β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid with amoxicillin did not show an appreciable reduction. The Coamox-clav resistance in P. aeruginosa was about 77%. Likewise, more than 50% of P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae isolates had developed resistance to the third generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone. From sulfa drug combination, cotrimoxazole resistance was observed in more than half of all isolates in each gram-negative bacterium with the highest resistance estimate (76%) observed in P. aeruginosa. Even if the degree of susceptibility varies across strains, relatively lower estimates of resistance were observed in ciprofloxacin and gentamicin making these agents relatively effective for treatment of wound infections.

In this regard, a plasmid encoded extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) production has been alarmingly increasing in gram-negative bacteria particularly in Enterobacteriaceae [62–64]. A study indicated that among K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolated from wound samples, around 11% produced ESBL (12.2 and 10.3% for K. pneumoniae and E. coli, respectively) [62]. ESBLs have the ability to hydrolyze extended spectrum β-lactams including third generation cephalosporins (e.g. ceftriaxone, ceftazidime and cefotaxime) and the monobactams (aztreonam). Carbapenems have been the treatment of choice for serious infections due to ESBL-producing organisms, yet carbapenem-resistant isolates have recently been reported [63, 65–67].

The difficult to treat gram-negative bacteria P. aeruginosa has naturally known to develop resistance by its outer membrane (porine channels) permeability problems coupled to adaptive mechanisms such as efflux pumps and can readily achieve clinical resistance. Almost all penicillins, except the fourth generation series (antipseudomonal agents such as ticarcillin and piperacillin), are not clinically effective at all for the treatment of Pseudomonas infections.. Likewise, majority of the third generation cephalosporins and all of the prior generations are no longer effective since they are not able to penetrate the porine channels of this bacterium though other resistance mechanisms should also be considered. Generally, this bacterium is highly notorious to develop resistance to multiple antibiotics and has joined the ranks of ‘superbugs’ due to its enormous capacity to engender resistance [48, 68–73].

Historically, the classes of antibiotics used in the treatment of wound infections include the β -lactams and aminoglycosides [47]. At present, guidelines have indicated that antibiotics prescribing practice primarily relies on expert opinion not on evidence based medicine. This has now created difficulties in interpreting and implementing it in clinical settings [15]. Besides, inappropriate use of antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis increases both the cost and the selective pressure favoring the emergence of resistant strains. Published reports indicated that, from about 30–50% of antibiotics being used for surgical prophylaxis, between 30 and 90% of it is potentially inappropriate [16, 74, 75]. The meta-analysis has vividly indicated that wound is contaminated with multiple microorganisms (poly-microbial infection) and hence antibiotic treatment should be tailored according to the microbial profiles. Particularly, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa are among the pathogen of interest and have several resistance mechanisms making the treatment challenging. In general, the most common drugs used to treat S. aureus infections include amoxicillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam, and cloxacillin whereas MRSA strains are better treated with levofloxacin, vancomycin, linezolid and tigecycline. In the presence of co-infections related to S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems and ciprofloxacin may represent the first choice for treatment of wound infections [53].

Conclusion

Generally, the wound culture positivity was very high indicating the likelihood of poly-microbial load. Surgical wounds had relatively lower culture positivity than non-surgical counterparts though the role of prior local wound care following surgery is yet to be investigated. Staphylococci have been the predominant gram-positive cocci in wound infection with S. aureus being by far the most prevalent isolate. This finding alarms the high load of MRSA strains in hospital settings as well. Gram-negative aerobic bacilli under Enterobacteriaceae are also commonly isolated pathogens in wound infections. Though it is expected in S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, all isolates exhibited highest estimates of resistance against β-lactam antibiotics. Most notably, resistance to the 3rd generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone was observed in more than 40% of all gram-negative isolates (more than half in K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa). Though more than 10% of resistance was reported in all isolates, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin were relatively good in treating wound infections with poly-microbial etiology. Hence, considering microbial epidemiology and AMR patterns, treatment should be tailored for addressing poly-microbial etiology thereby effectively manage wound infection and its complication as well as preserve antimicrobials and contain AMR.

Limitation of the study

Even if the study has extensively included all relevant data regarding wound infection, it was not without limitations. There was no clear demarcation of wound samples in inpatient and outpatient settings. Besides, there was no documented history of prophylactic use of antibiotics in individual studies though we conducted subgroup analyses to reduce culture positivity/negativity errors in surgical patients. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing was a little bit different across studies. Therefore, this meta-analysis should be seen in the context of such limitations.

Additional files

Table S1. Completed PRISMA checklist: The checklist highlights the important components addressed while conducting systematic review and meta-analysis from observational studies (DOC 66 kb)

Table S2. Data abstraction format with crude data: The table presented the ways of data collection (study characteristics and outcome measures) in Microsoft excel format. (XLSX 38 kb)

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to Haramaya University College of Health and Medical Sciences staffs who have technically supported us to realize this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial Resistance

- CoNS

Coagulase Negative Staphylococci

- ESBLs

Extended Spectrum β-lactamases

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- MRSA

Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PBP

Penicillin Binding Protein

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis

Authors’ contributions

MS conceived and designed the study. All authors collected scientific literature; critically appraised individual articles for inclusion, analyzed and interpreted the findings. MS drafted the manuscript, DE and TW critically reviewed it. MS prepared the final version for publication. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All the data is contained within the manuscript and additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mekonnen Sisay, Phone: +251 920 21 21 35, Email: mekonnensisay27@yahoo.com.

Teshager Worku, Email: teshager.kassie@gmail.com.

Dumessa Edessa, Email: jaarraa444@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Maier S, Korner P, Diedrich S, Kramer A, Heidecke CD. Definition and management of wound infections. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 2011;82(3):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00104-010-2012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warriner R, Burrell R. Infection and the chronic wound: a focus on silver. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(8):2–12. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200510001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqui AR, Bernstein JM. Chronic wound infection: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(5):519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens C, Stoessel K. Surgical site infections: epidemiology, microbiology and prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70:3–10. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice LB. Antimicrobial resistance in gram-positive bacteria. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(5):S11–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agnihotri N, Gupta V, Joshi R. Aerobic bacterial isolates from burn wound infections and their antibiograms—a five-year study. Burns. 2004;30(3):241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guggenheim M, Zbinden R, Handschin AE, Gohritz A, Altintas MA, Giovanoli P. Changes in bacterial isolates from burn wounds and their antibiograms: a 20-year study (1986–2005) Burns. 2009;35(4):553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):403–434. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg M. Role of prophylactic antibiotics and prevalence of post-operative wound infection in surgery department. Int Arch BioMed Clin Res. 2018;4(2):187–189. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers HF, De Leo FR. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(9):629. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daeschlein G. Antimicrobial and antiseptic strategies in wound management. Int Wound J. 2013;10(s1):9–14. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malone M, Bjarnsholt T, McBain AJ, James GA, Stoodley P, Leaper D, Tachi M, Schultz G, Swanson T, Wolcott RD. The prevalence of biofilms in chronic wounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. J Wound Care. 2017;26(1):20–25. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elbur AI, Yousif M, El-Sayed AS, Abdel-Rahman ME. Prophylactic antibiotics and wound infection. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2747. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6409.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rijal BP, Satyal D, Parajuli NP. High burden of antimicrobial resistance among Bacteria causing pyogenic wound infections at a tertiary Care Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. J Pathogens. 2017;2017:7. doi: 10.1155/2017/9458218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howell-Jones R, Wilson M, Hill K, Howard A, Price P, Thomas D. A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(2):143–149. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filius PM, Gyssens IC. Impact of increasing antimicrobial resistance on wound management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(1):1–7. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tweed C. Prevention of surgical wound infection: prophylactic antibiotics in colorectal surgery. J Wound Care. 2005;14(5):202–205. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2005.14.5.26769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis SJ. Chronic wound infection and antimicrobial use. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2008;21(11):531–540. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000323578.87700.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D: Prisma 2009 checklist. available at: http://www.prisma-statement.org. Accessed 28 Apr 2018.

- 21.JBI: The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: checklist for prevalence studies. The University of Adelaide. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html. 2017.

- 22.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asres G, Legese M, Woldearegay G. Prevalence of multidrug resistant Bacteria in postoperative wound infections at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Arch Med. 2017;9(4):12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dessalegn L, Shimelis T, Tadesse E. Gebre-selassie S: aerobic bacterial isolates from post-surgical wound and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern: a hospital based cross-sectional study. E3 J Med Res. 2014;3(2):18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelaw A, Gebre-Selassie S, Tiruneh M, Mathios E, Yifru S. Isolation of bacterial pathogens from patients with postoperative surgical site infections and possible sources of infections at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Occup Sci. 2014;3(2):103–108. doi: 10.5455/jeos.20140512124135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guta M, Aragaw K, Merid Y. Bacteria from infected surgical wounds and their antimicrobial resistance in Hawassa University referral teaching hospital, southern Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2014;8(11):1118–1124. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2013.6544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahsay A, Mihret A, Abebe T, Andualem T. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with surgical site infection at Debre Markos referral hospital, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Arch Publ Health. 2014;72(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mengesha RE, Kasa BGS, Saravanan M, Berhe DF, Wasihun AG. Aerobic bacteria in post surgical wound infections and pattern of their antimicrobial susceptibility in Ayder teaching and referral hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:575. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tekie K: Surgical wound infection in Tikur Anbessa hospital with special emphasis on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Unpublished MSc thesis in medical microbiology, Addis Ababa University, Medical Faculty, Ethiopia. http://etd.aau.edu.et/dspace/bitstream/123456789/2621/1/KASSAYE%20TEKIE.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

- 31.Dessie W, Mulugeta G, Fentaw S, Mihret A, Hassen M, Abebe E. Pattern of bacterial pathogens and their susceptibility isolated from surgical site infections at selected referral hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Microbiol. 2016;2016:2418902. doi: 10.1155/2016/2418902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bitew Kifilie Abebaw, Dagnew Mulat, Tegenie Birhanemeskel, Yeshitela Biruk, Howe Rawleigh, Abate Ebba. Bacterial Profile, Antibacterial Resistance Pattern, and Associated Factors from Women Attending Postnatal Health Service at University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Microbiology. 2018;2018:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2018/3165391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azene MK, Beyene BA. Bacteriology and antibiogram of pathogens from wound infections at Dessie laboratory, north East Ethiopia. Tanzan J Health Res. 2011;13(4):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bitew A, Admassie M, Getachew T. Spectrum and drug susceptibility profile of Bacteria recovered from patients with wound infection referred to Arsho advanced medical laboratory. Clin Med Res. 2018;7(1):8. doi: 10.11648/j.cmr.20180701.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godebo G, Kibru G, Tassew H. Multidrug-resistant bacterial isolates in infected wounds at Jimma University specialized hospital, Ethiopia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2013;12(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hailu D, Derbie A, Mekonnen D, Zenebe Y, Adem Y, Worku S, Biadglegne F. Drug resistance patterns of bacterial isolates from infected wounds at Bahir Dar regional Health Research Laboratory center, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2016;30(3):112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mama M, Abdissa A, Sewunet T. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from wound infection and their sensitivity to alternative topical agents at Jimma University specialized hospital, south-West Ethiopia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammed Aynalem, Seid Mengistu Endris, Gebrecherkos Teklay, Tiruneh Moges, Moges Feleke. Bacterial Isolates and Their Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Wound Infections among Inpatients and Outpatients Attending the University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Microbiology. 2017;2017:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2017/8953829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulu A, Moges F, Tessema B, Kassu A. Pattern and multiple drug resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from wound infection at University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44(2):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulu W, Abera B, Yimer M, Hailu T, Ayele H, Abate D. Bacterial agents and antibiotic resistance profiles of infections from different sites that occurred among patients at Debre Markos referral hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2584-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham Y, Wamisho BL. Microbial susceptibility of bacteria isolated from open fracture wounds presenting to the err of black-lion hospital, Addis Ababa university, Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2009;3(12):939–951. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alebachew T, Yismaw G, Derabe A, Sisay Z. Staphylococcus aureus burn wound infection among patients attending Yekatit 12 hospital burn unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(3):209–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Sewunet T, Demissie Y, Mihret A, Abebe T. Bacterial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of isolates among burn patients at Yekatit 12 hospital burn center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23(3):209–216. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v23i3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lema T, Woldeamanuel Y, Asrat D, Hunegnaw M, Baraki A, Kebede Y, Yamuah L, Aseffa A. The pattern of bacterial isolates and drug sensitivities of infected ulcers in patients with leprosy in ALERT, Kuyera and Gambo hospitals, Ethiopia. Lepr Rev. 2012;83(1):40–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rynga D, Deb M, Gaind R, Sharma VK. Wound infections in orthopaedics: a report of the bacteriological pattern and their susceptibility to antibiotics. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2016;18(1):139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perim MC, Borges JC, Celeste SRC, Orsolin EF, Mendes RR, Mendes GO, Ferreira RL, Carreiro SC, Pranchevicius MCS. Aerobic bacterial profile and antibiotic resistance in patients with diabetic foot infections. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48(5):546–554. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0146-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.AlBuhairan B, Hind D, Hutchinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis for wound infections in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90(7):915–919. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bessa LJ, Fazii P, Di Giulio M, Cellini L. Bacterial isolates from infected wounds and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern: some remarks about wound infection. Int Wound J. 2015;12(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernandez R. The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of chronic wounds. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(6):326–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolcott R, Gontcharova V, Sun Y, Zischakau A, Dowd S. Bacterial diversity in surgical site infections: not just aerobic cocci any more. J Wound Care. 2009;18(8):317–323. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2009.18.8.43630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fazli M, Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp-Møller K, Jørgensen B, Andersen AS, Krogfelt KA, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T. Nonrandom distribution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic wounds. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(12):4084–4089. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01395-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Taie LH. Isolation and identification of bacterial burn wound infection and their sensitivity to antibiotics. Al-Mustansiriyah J Sci. 2014;25(2):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serra R, Grande R, Butrico L, Rossi A, Settimio UF, Caroleo B, Amato B, Gallelli L, de Franciscis S. Chronic wound infections: the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2015;13(5):605–613. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1023291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Howell-Jones RS, Price PE, Howard AJ, Thomas DW. Antibiotic prescribing for chronic skin wounds in primary care. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14(4):387–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.JLSd M, Santos JB. Bacterial and fungal colonization of burn wounds. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100(5):535–539. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762005000500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schito G. The importance of the development of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Łęski TA, Tomasz A. Role of penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2) in the antibiotic susceptibility and cell wall cross-linking of Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for the cooperative functioning of PBP2, PBP4, and PBP2A. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):1815–1824. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1815-1824.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehta M, Dutta P, Gupta V. Bacterial isolates from burn wound infections and their antibiograms: a eight-year study. Ind J Plastic Surg. 2007;40(1):25. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.32659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enright MC, Robinson DA, Randle G, Feil EJ, Grundmann H, Spratt BG. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(11):7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122108599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foster TJ. The Staphylococcus aureus “superbug”. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1693–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI200423825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moreno F, Crisp C, Jorgensen JH, Patterson JE. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a community organism. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(5):1308–1312. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kader AA, Kumar A. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a general hospital. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25(3):239–242. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):657–686. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paterson DL, Ko W-C, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, Mulazimoglu L, Trenholme G, Klugman KP, Bonomo RA. Antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(1):31–37. doi: 10.1086/420816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradford PA. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(4):933–951. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.933-951.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Laupland KB, Poirel L. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(1):52–59. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jacob JT, Klein E, Laxminarayan R, Beldavs Z, Lynfield R, Kallen AJ, Ricks P, Edwards J, Srinivasan A, Fridkin S. Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(9):165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(8):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hauke J, Iryna J, Paul C, Clemens K, Theresia P, Michael Q, Mathieu M, Uwe G, Marco HS. Antimicrobial-resistant Bacteria in infected wounds, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2018;24(5):916. doi: 10.3201/eid2405.171506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rayner C, Munckhof W. Antibiotics currently used in the treatment of infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Intern Med J. 2005;35:S3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2005.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Delcour AH. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteomics. 2009;1794(5):808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hancock RE, Speert DP. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and impact on treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2000;3(4):247–255. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Avni T, Levcovich A, Ad-El DD, Leibovici L, Paul M. Prophylactic antibiotics for burns patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2010;340:c241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cohen ML. Epidemiology of drug resistance: implications for a post—antimicrobial era. Science. 1992;257(5073):1050–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Munckhof W. Antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis. Aust Prescr. 2005;28(2):38–40. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2005.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Completed PRISMA checklist: The checklist highlights the important components addressed while conducting systematic review and meta-analysis from observational studies (DOC 66 kb)

Table S2. Data abstraction format with crude data: The table presented the ways of data collection (study characteristics and outcome measures) in Microsoft excel format. (XLSX 38 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All the data is contained within the manuscript and additional files.