Abstract

Background

China has the largest obese population in the world, and the prevalence of central obesity is increasing dramatically in China. Moreover, the rapid economic growth of China in recent decades has led to rapid urbanization in rural China. However, studies comparing the prevalence trends of different types of obesity and the association of obesity with hypertension between urban and rural areas in China are very scarce, and most studies have focused only on the difference in the prevalence of overweight and general obesity or hypertension among rural and urban populations. Therefore, the focus of this study was to examine the shifts in the overall distribution of the prevalence of different types of obesity and to estimate the risk of hypertension in different types of obesity among urban and rural adults aged 18–65 years.

Methods

Seven iterations of the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), conducted in 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009 and 2011, were used in this study. A total of 53,636 participants aged 18–65 years were included. Obesity was classified into three types based on body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC). A log-binomial model was constructed to estimate the prevalence ratio (PR) of hypertension with three types of obesity.

Results

The age-standardized prevalence of central obesity only, general obesity only, and both central and general obesity increased from 15.8, 0.2 and 2.9% in 1993 to 30.3, 0.9 and 10.3% in 2011, respectively. The prevalence of central obesity only (urban vs. rural: 20.8% vs. 13.4% in 1993, 29.6% vs. 30.6% in 2011) and both central and general obesity (urban vs. rural: 3.5% vs. 2.5% in 1993, 10.0% vs. 10.6% in 2011) in rural adults exceeded that in urban adults in 2011. Participants with both central and general obesity had the highest risk for incident hypertension compared with those with normal body measurements (adjusted PR, urban: 2.30 (95% CI, 2.01–2.63), rural: 2.50 (95% CI, 2.25–2.77)).

Conclusions

Both WC and BMI should be considered measures of obesity and targeted in hypertension prevention. More attention should be paid to the incidence of central obesity in adults in rural China.

Keywords: Central obesity, General obesity, Hypertension, Urbanization

Background

Obesity, a key cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD), is becoming a worldwide health concern [1]. According to the Chinese resident’s chronic disease and nutrition report in 2015, obesity rates among those 18 years old and above in China were 11.9% in 2012, which indicates that there were more than 124 million obese adults in China in 2012 [2]. Additionally, there were 292 million adults with hypertension in China in 2013–2014; in 2002, there were 153 million adults with hypertension [3]. However, in 2013 in China, the overall blood pressure control rates of adults with hypertension was only 9.7% [3]. Abnormally high blood pressure can lead serious health problem. In 2013, high systolic blood pressure caused 10.4 million deaths and 208.1 million disability-adjusted life years in the world [4].

Previous studies have revealed that obesity seemed to increase the risk of hypertension. In China, body mass index (BMI) is usually used to assess obesity [5]. However, obesity, as defined by BMI, is not a fitness indicator of body fat distribution [6]. Central obesity, measured by waist circumference (WC), has been shown to be a strong risk factor for the prevalence of hypertension and stroke [7]. Compared to individuals with a normal BMI, a population with central obesity has a higher risk of incident hypertension [8]. Additionally, with the improvement of living standards, young Chinese generations are facing more serious obesity problems, and younger cohorts have a higher prevalence of obesity than older cohorts [9, 10]. When these young people become older, those with central obesity will have a higher risk of developing hypertension later in life than those with general obesity [11].

However, studies comparing the trend in the prevalence of different types of obesity and the association with hypertension in urban and rural areas in China are scarce. Most studies have focused only on the difference in the prevalence of overweight and general obesity or hypertension among rural and urban populations [12, 13]. In recent decades, the economy of China has grown dramatically, leading to rapid urbanization in rural China. A previous study showed that China’s disease spectrum had significantly changed from communicable to noncommunicable diseases during China’s urbanization from 1995 to 2010 [14], and chronic health conditions, such as overweight and hypertension, were associated with urbanization [15]. Additional research is needed to explore the impact of urbanization in China on the prevalence of different types of obesity and the association with hypertension.

Therefore, this study focuses on examining the shifts in the overall distribution of the prevalence of different types of obesity and estimates the risk of hypertension with different types of obesity, while also comparing the discrepancy between urban and rural adults aged 18–65 years in China. We used cross-sectional data from a survey administered in China over 18 years to conduct our study.

Methods

Study design and population

We used data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) for our analysis. This survey is still ongoing and was completed in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011 and 2015. The CHNS data and questionnaires can be used freely after registering at the official website (Data: https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china/data, Questionnaires: https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china/data/questionnaires). The main purpose of the survey was to investigate the health and nutrition status of Chinese individuals. The CHNS was conducted by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. A multistage, random cluster process was used to conduct the CHNS survey. The sample was taken in eight provinces (Liaoning, Shandong, Henan, Jiangsu, Hubei, Hunan, Guizhou, and Guangxi). In each province, counties and cities were stratified by income (low, middle and high), and four counties and two cities were randomly selected by a weighted sampling scheme. In the selected counties, villages and townships were randomly selected. In selected cities, urban and suburban neighborhoods were randomly selected. Twenty households were randomly selected, and all household members were interviewed in each community. Additional details of the CHNS can be found elsewhere [16]. The 1989 and 1991 surveys did not collect data on WC, and the 2015 survey only disclosed a part of the data, so this study examined data from 1993 to 2011. This study focused on adults aged 18–65 years. Participants who had missing data on WC, BMI, blood pressure (BP), age, urbanization, or gender or who were actively pregnant were excluded from the analysis. Our analysis included 53,636 participants (6782, 7288, 8227, 7243, 7236, 6668 and 10,192 participants in 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009 and 2011, respectively), with 18,216 from urban areas and 35,420 from rural areas.

Study variables

Well-trained physicians conducted anthropometrical measurements, such as weight, height, WC, and BP, following a reference protocol recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). The weight measurement was conducted with participants wearing lightweight clothing on a balance-beam scale that was accurate to 0.1 kg. The height measurement was conducted with participants barefoot on a portable stadiometer that was accurate to 0.1 cm [12]. The WC measurement was taken with a measuring tape placed at the midpoint between the lower margin of the arcus costalis on the midaxillary and the interiliac crest lines and was accurate to 0.1 cm [11]. Experienced physicians measured systolic and diastolic blood pressures three times on the right arm using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer. Before measurement, participants were required to have an initial five-minute, seated rest and a 30-s interval between cuff inflations; we used the mean value in this study [13]. Demographic and behavioral information, such as smoking, drinking, and urbanization, was collected by a structured questionnaire [16].

General obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2, which is recommended by the Working Group on Obesity in China [17]. Central obesity was defined as WC ≥ 90 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women, as recommended by the International Diabetes Federation [18]. Therefore, we classified obesity into three types: central obesity only (BMI < 28 kg/m2 and WC ≥ 90/80 cm), general obesity only (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 and WC < 90/80 cm) and both central and general obesity (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 and WC ≥ 90/80 cm). Participants with a BMI < 28 kg/m2 and a WC < 90/80 cm were defined as normal. Hypertension was defined as a self-reported doctor diagnosis of hypertension, a measured mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg [19]. Participants who smoked cigarettes or drank alcohol during the previous year were recognized as smokers or drinkers, separately. In this study, the outcome variables were the prevalence of obesity and hypertension, and independent variables were smoking, drinking, gender, survey year, and age.

Statistical analysis

In descriptive analyses, numeric variables were described as the means and standard deviation (SD), and character variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. All analyses were stratified by urbanization (urban vs. rural). The estimated prevalence was age-standardized to the 2010 Sixth National Population Census of Chinese adults by the direct method [20]. Student’s t-test was used to compare the difference in BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, and age between urban and rural individuals. A chi-square test was used to compare differences in the prevalence of hypertension between urban and rural areas. Cochran-Armitage trend testing was used to test the trends of the prevalence of three types of obese participants aged 18–65 years from 1993 to 2011. A multiple log-binomial mixed effect model was performed to estimate the prevalence ratio (PR) of hypertension with the three types of obesity. Models were used with adjustment for clustering effects (communities and households). Adjusted PR was estimated by adjusting smoking, drinking, gender, survey year, and age, which have been recognized as factors of hypertension [11, 21, 22]. All descriptive analyses, tests, and statistical models were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA), and visualization plots were conducted using the ‘ggplot2’ [23] and ‘ggridges’ [24] package in R software v.3.4.3.

Results

Sample characteristics and trends of BMI, WC, and BP distribution among populations in urban and rural areas from 1993 to 2011

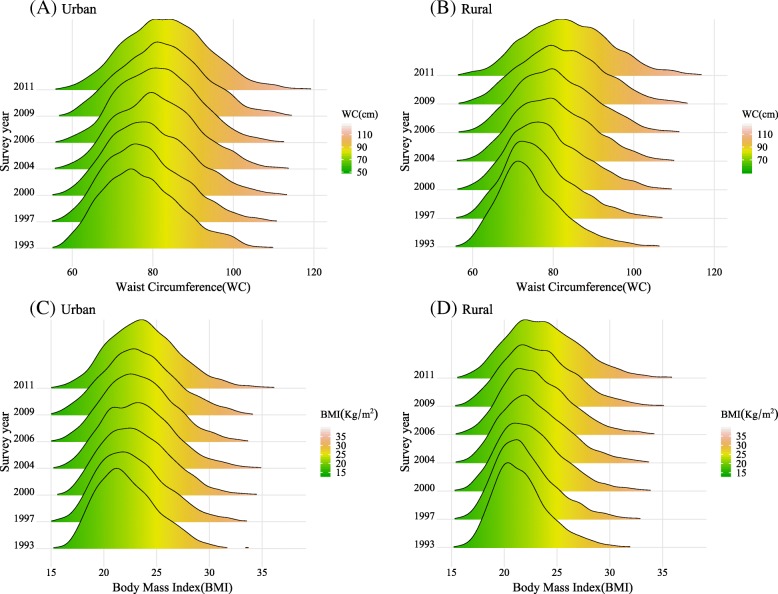

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. For all survey years, the number of female participants was slightly more than that of males. The mean age increased from 38.8 (SD = 12.87) years to 46.5 (SD = 11.99) years. For participants in both urban and rural areas, the anthropometric variables (BMI, WC, SBP, and DBP) increased notably over the past 18 years. We clearly found that the BMI and WC distribution curves among urban and rural participants shifted to the right from 1993 to 2011, as seen in Fig. 1. Before 2006, the BMI and WC of urban participants were higher than those of rural participants. The gap between urban and rural areas was statistically insignificant in 2009 and 2011.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Chinese adults aged 18–65 years by survey year and urban and rural areas in 1993–2011

| Survey year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | |

| All participants | 6782 | 7288 | 8227 | 7243 | 7236 | 6668 | 10,192 |

| Males n (%) | 3235 (47.7) | 3561 (48.9) | 3936 (47.8) | 3466 (47.9) | 3418 (47.2) | 3173 (47.6) | 4777 (46.9) |

| Age (year) | 38.8 (12.87) | 39.8 (12.68) | 41.3 (12.37) | 43.7 (12.01) | 44.7 (11.80) | 45.6 (12.08) | 46.5 (11.99) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.9 (2.81) | 22.3 (3.04) | 22.8 (3.16) | 23.1 (3.28) | 23.3 (3.50) | 23.4 (3.40) | 24 (4.18) |

| WC (cm) | 75.6 (8.93) | 77.3 (9.22) | 79.1 (9.69) | 80.5 (9.74) | 81 (9.78) | 82.4 (10.25) | 83.7 (11.09) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 113.9 (16.30) | 116.8 (16.31) | 117.7 (16.35) | 119.9 (16.83) | 119.5 (16.35) | 121.9 (17.23) | 122.5 (16.53) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75 (10.78) | 76.5 (10.60) | 77.1 (10.73) | 78.3 (11.01) | 78.5 (10.65) | 79.8 (10.91) | 79.2 (10.54) |

| Urban | 2047 | 2457 | 2717 | 2435 | 2367 | 2108 | 4085 |

| Males n (%) | 972 (47.5) | 1178 (47.9) | 1291 (47.5) | 1156 (47.5) | 1121 (47.4) | 995 (47.2) | 1907 (46.7) |

| Age (year) | 40 (13.10) ** | 40.1 (12.74) | 41.9 (12.46) * | 43.6 (12.36) | 44.9 (12.12) | 46 (12.25) | 46.5 (12.22) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 (2.95) ** | 22.8 (3.21) ** | 23.1 (3.21) ** | 23.4 (3.35) ** | 23.4 (3.28) * | 23.5 (3.45) | 24.1 (4.13) |

| WC (cm) | 77.5 (9.80) ** | 78.4 (9.82) ** | 79.9 (10.15) * | 81.3 (10.01) * | 81.6 (9.73) ** | 82.6 (10.26) | 83.6 (10.94) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 115.3 (17.26) | 116.9 (16.91) | 118 (16.42) | 120.3 (16.95) | 119.8 (15.99) | 121.3 (16.68) | 122.1 (15.58) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.2 (11.36) * | 77 (10.76) ** | 77.4 (10.96) | 78.6 (10.68) | 78.9 (10.27) * | 79.9 (10.50) | 78.8 (9.54) ** |

| Rural | 4735 | 4831 | 5510 | 4808 | 4869 | 4560 | 6107 |

| Males n (%) | 2263 (47.8) | 2383 (49.3) | 2645 (48.0) | 2310 (48.0) | 2297 (47.2) | 2178 (47.8) | 2870 (47.0) |

| Age (year) | 38.3 (12.73) | 39.7 (12.65) | 41 (12.32) | 43.7 (11.83) | 44.7 (11.65) | 45.5 (11.99) | 46.4 (11.83) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 (2.73) | 22.1 (2.92) | 22.7 (3.13) | 23 (3.23) | 23.2 (3.59) | 23.3 (3.37) | 24 (4.22) |

| WC (cm) | 74.8 (8.39) | 76.7 (8.85) | 78.8 (9.43) | 80.2 (9.58) | 80.7 (9.79) | 82.2 (10.25) | 83.7 (11.19) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 113.2 (15.82) | 116.7 (15.99) | 117.5 (16.31) | 119.6 (16.76) | 119.4 (16.53) | 122.2 (17.47) | 122.7 (17.13) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.5 (10.47) | 76.2 (10.52) | 76.9 (10.60) | 78.2 (11.17) | 78.2 (10.82) | 79.7 (11.10) | 79.5 (11.16) |

Values presented as numbers for arbitrary values and as the mean (SD) or n (%) for other variables

Student’s t-test was applied to test the difference between urban and rural areas, * significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01

Fig. 1.

Shifts in the density curves of BMI and WC for Chinese adults aged 18–65 years, by urban and rural areas, 1993–2011

Prevalence trends of three types of obesity among urban and rural populations from 1993 to 2011

In Table 2, we presented the age-standardized prevalence of central obesity only, general obesity only, and both central and general obesity by survey year. The age-standardized prevalence of central obesity only, general obesity only, and both central and general obesity increased from 15.8, 0.2 and 2.9% in 1993 to 30.3, 0.9 and 10.3% in 2011, respectively. The highest prevalence was observed in participants with central obesity only (urban: 29.6%, rural: 30.6%, in 2011). The prevalence of participants with general obesity only (urban: 1.1%, rural: 0.8%, in 2011) was the lowest. Meanwhile, the gap between the prevalence of central only obesity and both central and general obesity between urban and rural participants narrowed from 1993 to 2011. Before 2006, the participants in urban areas had a higher prevalence of central obesity only than that in participants in rural areas, but the prevalence in rural participants increased in 2009 and 2011. However, the prevalence of general obesity was still higher in urban participants than that in rural participants.

Table 2.

Age-standardized prevalence (95% CI) of three types of obesity in Chinese adults, aged 18–65 years, by survey year and urban and rural areas in 1993–2011

| Survey year | P for trend a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | ||

| All participants | ||||||||

| Central obesity only | 15.8 (15.5–16.0) | 18.0 (17.7–18.2) | 21.8 (21.6–22.1) | 23.7 (23.5–24.0) | 25.0 (24.8–25.3) | 27.9 (27.6–28.2) | 30.3 (30.0–30.6) | <.0001 |

| General obesity only | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 0.6 (0.5–0.6) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | <.0001 |

| Both central and general obesity | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) | 4.4 (4.3–4.6) | 5.6 (5.5–5.8) | 6.4 (6.3–6.6) | 6.4 (6.2–6.5) | 8.1 (8.0–8.3) | 10.3 (10.1–10.5) | <.0001 |

| Urban | ||||||||

| Central obesity only | 20.8 (20.6–21.1) ** | 21.3 (21.0–21.6) ** | 23.2 (23–23.5) ** | 24.9 (24.6–25.2) ** | 26.2 (25.9–26.4) ** | 27.5 (27.2–27.8) * | 29.6 (29.3–29.9) ** | <.0001 |

| General obesity only | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) ** | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) ** | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) ** | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) ** | 0.7 (0.6–0.7) ** | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) ** | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) ** | <.0001 |

| Both central and general obesity | 3.5 (3.4–3.6) ** | 6.1 (5.9–6.2) ** | 6.6 (6.4–6.7) ** | 7.5 (7.3–7.6) ** | 6.5 (6.4–6.7) * | 8.7 (8.6–8.9) ** | 10.0 (9.8–10.2) ** | <.0001 |

| Rural | ||||||||

| Central obesity only | 13.4 (13.2–13.6) | 16.3 (16.0–16.5) | 21.1 (20.8–21.3) | 23.2 (22.9–23.4) | 24.5 (24.2–24.7) | 28.0 (27.7–28.3) | 30.6 (30.3–30.9) | <.0001 |

| General obesity only | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 0.2 (0.2–0.2) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | <.0001 |

| Both central and general obesity | 2.5 (2.4–2.6) | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) | 5.2 (5.0–5.3) | 5.8 (5.7–6.0) | 6.3 (6.1–6.4) | 7.9 (7.7–8.0) | 10.6 (10.4–10.8) | <.0001 |

CI confidence interval

A chi-square test was applied to test the difference between urban and rural, * significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01

aTrends in the prevalence of three types of obesity from 1993 to 2011 were assessed by Cochran-Armitage trend testing

Prevalence ratio of hypertension with different types of obesity among participants in urban and rural areas

Table 3 presents the prevalence ratio (PR) and adjusted PR of hypertension with different types of obesity among the populations in urban and rural areas. For both urban and rural participants, both central and general obesity had higher risk for incident hypertension than did normal controls (urban: PR = 3.46, 95% CI, 3.16–3.79; rural: PR = 3.64, 95% CI, 3.40–3.90). After adjustment for gender, smoking status, drinking status, age, and survey year (urban: adjusted PR = 2.30, 95% CI, 2.01–2.63; rural: adjusted PR = 2.50, 95% CI, 2.25–2.77), compared with normal subjects, urban participants with central obesity (adjusted PR = 1.82, 95% CI, 1.62–2.04) had a lower risk for incident hypertension than did those with general obesity (adjusted PR = 2.13, 95% CI, 1.48–3.05). However, compared with normal subjects, rural participants with central obesity (adjusted PR = 1.78, 95% CI, 1.62–1.94) had a higher risk for incident hypertension than did those with general obesity (adjusted PR = 1.50, 95% CI, 0.96–2.33).

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios of hypertension with different types of obesity in urban and rural areas according to the log-binomial mixed effects model

| Urban | Rural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR(95% CI) | Adjusted PR(95% CI) | PR(95% CI) | Adjusted PR(95% CI) | |

| Normal (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Central obesity only | 2.22 (2.06–2.38)** | 1.82 (1.62–2.04) ** | 2.03 (1.92–2.15) ** | 1.78 (1.62–1.94) ** |

| General obesity only | 2.56 (1.94–3.39) ** | 2.13 (1.48–3.05) ** | 1.79 (1.31–2.45) ** | 1.50 (0.96–2.33) |

| Both central and general obesity | 3.46 (3.16–3.79) ** | 2.30 (2.01–2.63) ** | 3.64 (3.40–3.90) ** | 2.50 (2.25–2.77) ** |

CI confidence interval, * significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01

aNormal indicates participants with a BMI < 28 kg/m2 and WC < 90/80 cm

bAdjusted for smoking, drinking, gender, survey year, age and clustering effects (communities and households)

Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated that the age-standardized prevalence of central obesity only, general obesity only, and both central and general obesity all increased significantly in Chinese adults from 1993 to 2011. The prevalence of participants with central obesity only was the highest for the three types of obesity. Additionally, the prevalence of central obesity only and both central and general obesity in adults in rural areas exceeded that of adults in urban areas in 2011. Participants with both central and general obesity had the highest risk of incident hypertension compared with those with normal BMIs and WCs.

This study showed that an upward trend was noted in the distribution of BMIs and WCs in Chinese adults aged 18–65 years. The mean BMI increased from 21.9 kg/m2 to 24.0 kg/m2, and the mean WC increased from 75.6 cm to 83.7 cm in 1993 and 2011, respectively. These results are in line with previous studies [9–11]. Distribution curves of BMIs and WCs shifted to the right, which indicated that the population suffered a higher proportion of obesity and overweight. As we found, the prevalence of obesity, whether defined by BMI or WC, has increased significantly over the past 18 years in China, particularly central obesity. The rising trend is similar in Korean men, whose prevalence rate of abdominal obesity increased from 22.1% in 1998 to 27.5% in 2007 [25]. In addition, in the three types of obesity, we revealed that the prevalence of central obesity with a normal or abnormal BMI (30.3 and 10.3% in 2011) was far higher than that of general obesity with a normal WC (0.9% in 2011), and no difference was found between participants from urban and rural areas. This constitution of different types of obesity has also been reported in a previous study, in which the constituent ratio of subjects with an exclusive BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 was only 0.9% in 2009 [8]. This finding suggests that it may be more accurate to combine WC and BMI when screening for obesity.

One of the concerns in our study was whether there was a similarity or difference in the prevalence of obesity among adults in urban and rural areas in China. Notably, the prevalence of central obesity increased more quickly among adults in rural areas than among adults in urban areas in this study. This result seems to be consistent with previous studies that found that the prevalence of central obesity of residents in rural areas increased more rapidly than that of residents in urban areas [8, 26]. However, we have some new findings. First, the gap between the prevalence of central obesity only and both central and general obesity between adults in urban and rural areas narrowed from 1993 to 2011. Second, the overall prevalence of central obesity in adults in rural areas was beyond that in adults in urban areas in 2011. These findings may be attributed to the changes in China’s social and economic structure led by China’s urbanization [27]. A previous observation confirmed that chronic health conditions, such as overweight, are associated with modernization and affluence, and the appearance of these conditions is no longer restricted to urban populations [15]. In China, the average food consumption per person in rural households increased from 890.3 Yuan in 1997 to 2323.9 Yuan in 2012, and the Engel coefficients of urban and rural households were 46.6 and 55.1% in 1997 and 36.2 and 39.3% in 2012, respectively [28]. Along with urbanization, the food consumption capacity of adults in rural areas has developed rapidly. Therefore, it is possible that accelerated health decline, such as the prevalence of central obesity in more urbanized areas, is exacerbated by a high-fat diet and decreased physical activity [29].

Another aim of our study was to estimate the risk of hypertension with the three types of obesity and to compare the differences between adults in urban and rural areas. The positive relationship between hypertension and obesity has been reported widely in many studies [11, 30–33]. In Chinese adults, BMI is highly associated with high blood pressure [32], and changes in BMI show a dose-response relationship with incident hypertension [33]. WC provides a unique indicator of body fat distribution and has often been used as a reasonable predictor of the risk of hypertension [34]. Previous studies have reported that central obesity also raises the risk of incident hypertension in later life [11] and leads to a higher risk of incident hypertension compared with that of individuals with a normal BMI [8]. However, studies have not investigated whether a population with central obesity has a higher risk of incident hypertension compared with a population with general obesity. Limited information from previous studies is available [8]; however, our results expanded on this information. We found that the risk of hypertension among the three types of obesity in adults in urban areas is as follows: both central and general obesity > general obesity only > central obesity only and in adults in rural areas is both central and general obesity > central obesity only > general obesity only. This indicates that central obesity not only is an independent risk of hypertension but also increases the risk when accompanied by general obesity.

Several limitations exist in our study. First, as a limitation of the data, we cannot provide exact explanations for the prevalence of central obesity among adults in rural areas exceeding that of adults in urban areas in 2011. Second, the risk of hypertension with central obesity only and general obesity only is not consistent in adults in urban and rural areas. If central obesity is commonly used as a reasonable predictor of the risk of incident hypertension in Chinese adults, which should be consistent in urban and rural adults, future research may be needed to examine the reasons for this. Third, although our sample size was large and the participants were from eight provinces in China, the sample was still only a part of China, and a broader national study should be conducted to support the results. Fourth, the data of CHNS used in this study is cross-sectional data, the causal inference is weak, and it is difficult to deeply explore the relationship between obesity and hypertension. Fifth, the most recent data in our study was from 2011, but China’s urban and rural areas are still very much changing, and an updated study should continue to pay attention to and observe the difference in trends of residents of urban and rural areas in China.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the prevalence of central obesity increased notably in Chinese adults aged 18–65 years with normal or abnormal BMI from 1993 to 2011. In addition, the prevalence of central obesity increased more rapidly in adults in rural areas than it did in adults in urban areas. The prevalence central obesity only and both central and general obesity in adults in rural areas exceeded that in adults in urban areas in 2011. Subjects with both central and general obesity had the highest risk of incident hypertension despite normal BMI or WC. Therefore, both WC and BMI should be considered measures of obesity and targeted in hypertension prevention. More attention should be paid to the incidence of central obesity in adults in rural areas.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) for sharing the survey data freely. Many thanks to the NIH Fogarty program for financial support for the CHNS data collection and analysis files since 1989, the China-Japan Friendship Hospital, the Ministry of Health for support for CHNS 2009, the Chinese National Human Genome Center at Shanghai since 2009, and the Beijing Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control since 2011.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BP

Blood Pressure

- CHNS

China Health and Nutrition Survey

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- PR

Prevalence Ratio

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

- SD

Standard Deviation

- WC

Waist Circumference

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

CS performed the statistical analyses and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. DL, DTZ, and WYD provided language help and analysis assistance and gave significant suggestions in the process of revising. SL, XXT, and XL provided writing assistance. ZLZ and JMG provided useful suggestions for the study framework. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, R01 HD30880; P2C HD050924), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, R01 DK104371), and the NIH Fogarty D43 TW009077. This study was also funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71874137).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in this study are available from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china/data/datasets/data_downloads/longitudinal.). The CHNS data and questionnaires are publically available, everyone can use freely after registering at the official website.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained written informed consent, and this study was approved by the Ethical Standards Committee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Approval Number: 07–1963).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chi Shen, Email: shenchi@outlook.com.

Zhongliang Zhou, Email: zzliang1981@163.com.

Sha Lai, Email: shayanglala0217@163.com.

Xingxing Tao, Email: singingtao@outlook.com.

Dantong Zhao, Email: zhaodt1224@163.com.

Wanyue Dong, Email: wanyuedong@foxmail.com.

Dan Li, Email: danlixjtu@126.com.

Xin Lan, Email: lanxin1203@126.com.

Jianmin Gao, Email: gaojm@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet (London, England) 2011;377(9765):557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Health Commission of the People’s republic of China. 2014 report on Chinese resident’s chronic disease and nutrition (Updated: 2015-06-15). http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2015-06/15/c_45788.htm (Accessed 26 Nov 2018).

- 3.Li Y, Yang L, Wang L, Zhang M, Huang Z, Deng Q, Zhou M, Chen Z, Wang L. Burden of hypertension in China: a nationally representative survey of 174,621 adults. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, Brauer M, Burnett R, Casey D, Coates MM, Cohen A, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–2323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Mi J, Shan X, Wang QJ, Ge K. Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. Int J Obes. 2007;31(1):177. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rankinen T, Kim SY, Pérusse L, Després JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis. Int J Obes. 1999;23(8):801–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Shu XO, Gao YT, Yang G, Li H, Zheng W. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of stroke in Chinese women. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1098–1104. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.539692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du T, Huo R, Chaochao Y, Xuefeng X. Increasing trends in central obesity among Chinese adults with normal; body mass index, 1993-2009. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):327. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren Qian, Su Chang, Wang Huijun, Wang Zhihong, Du Wenwen, Zhang Bing. Change in Body Mass Index and Its Impact on Incidence of Hypertension in 18–65-Year-Old Chinese Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016;13(3):257. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaacks LM, Gordon-Larsen P, Mayer-Davis EJ, Adair LS, Popkin B. Age, period and cohort effects on adult body mass index and overweight from 1991 to 2009 in China: the China health and nutrition survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(3):828–837. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niu J, Seo DC. Central obesity and hypertension in Chinese adults: a 12-year longitudinal examination. Prev Med. 2014;62:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Du S, Zhai F, Popkin BM. Trends in the distribution of body mass index among Chinese adults, aged 20-45 years (1989-2000) Int J Obes. 2007;31(2):272–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attard SM, Herring AH, Zhang B, Du S, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Associations between age, cohort, and urbanization with SBP and DBP in China: a population-based study across 18 years. J Hypertens. 2015;33(5):948–956. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu M, Liu X, Huang Y, Ma Z, Bi J. Epidemic transition of environmental health risk during China’s urbanization. Sci Bull. 2017;62(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van de Poel E, O'Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E. Urbanization and the spread of diseases of affluence in China. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7(2):200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, Zhang B. Cohort profile: the China health and nutrition survey-monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China, 1989-2011. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1435–1440. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet (London, England) 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet (London, England) 2005;366(9491):1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Bureau of Statistics. 2010 Sixth National population census data. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm (Accessed 31 May 2018).

- 21.Nurdiantami Y, Watanabe K, Tanaka E, Pradono J, Anme T. Association of general and central obesity with hypertension. Clin Nutr. 2017;37(4):1259–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Huxley R, Li L, Anna V, Xie G, Yao C, Woodward M, Li X, Chalmers J, Gao R, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from the China National Nutrition and health survey 2002. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2679–2686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claus O. Wilke: ggridges: Ridgeline Plots in ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.5.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggridges.

- 25.Yoo S, Cho HJ, Khang YH. General and abdominal obesity in South Korea, 1998-2007: gender and socioeconomic differences. Prev Med. 2010;51(6):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xi B, Liang Y, He T, Reilly KH, Hu Y, Wang Q, Yan Y, Mi J. Secular trends in the prevalence of general and abdominal obesity among Chinese adults, 1993–2009. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen T, Hui EC-M, Lang W, Tao L. People, recreational facility and physical activity: new-type urbanization planning for the healthy communities in China. Habitat Int. 2016;58:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Bureau of Statistics. Average food consumption per person in rural households. http://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0A01&sj=2016 (Accessed 31 May 2018).

- 29.Ouyang Y, Wang H, Su C, Du W, Wang Z, Zhang B. Why is there gender disparity in the body mass index trends among adults in the 1997-2011 China health and nutrition surveys? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24(4):692–700. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.4.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohammadi M, Mirzaei M. Population-attributable fraction of hypertension associated with obesity, abdominal obesity, and the joint effect of both in the central provinces of Iran. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangros FJ, Torrecilla J, Giraldez-Garcia C, Carrillo L, Mancera J, Mur T, Franch J, Diez J, Goday A, Serrano R, et al. Association of General and Abdominal Obesity with Hypertension, dyslipidemia and prediabetes in the PREDAPS study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71(3):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z, Smith M, Du H, Guo Y, Clarke R, Zheng B, Collins R, Chen J, Qian Y, Wang X. Blood pressure in relation to general and central adiposity among 500 000 adult Chinese men and women. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(4):1305–1319. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Zhao Y, Sun H, Luo X, Wang C, Li L, Zhang L, Wang B, Ren Y, Zhou J, et al. Effect of dynamic change in body mass index on the risk of hypertension: results from the rural Chinese cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;238:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berglund G, Ljungman S, Hartford M, Wilhelmsen L, Björntorp P. Type of obesity and blood pressure. Hypertension. 1982;4(5):692–696. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.4.5.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china/data/datasets/data_downloads/longitudinal.). The CHNS data and questionnaires are publically available, everyone can use freely after registering at the official website.