To the Editor—It is with great interest that we read the recently published manuscript on Kaposi sarcoma (KS) risk in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected children worldwide [1]. The particularly high incidence rate of pediatric KS reported in eastern Africa is striking. The experience in our pediatric HIV-related malignancy program in Lilongwe, Malawi, is consistent with the epidemiologic data from the Pediatric AIDS-Defining Cancer Project Working Group. In eastern and central Africa—where human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is endemic and prevalence rates are highest in the world—KS is among the 3 most common childhood cancers overall [2–5].

With the increased availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade, it is important to determine trends in KS. Data from South Africa and Zambia demonstrate that in adults, the risk for KS and incidence rates remain high despite increased cART coverage [6, 7].

We retrospectively investigated trends in pediatric KS from 2006 to 2015 in our pediatric (<18 years of age) HIV-related malignancy program at the Baylor College of Medicine International Pediatric AIDS Initiative Center of Excellence in Lilongwe, Malawi. The scale-up in delivering cART to children in the Malawian national antiretroviral program began in 2005. Since then, >50000 children have been initiated on cART, including 3964 at our center.

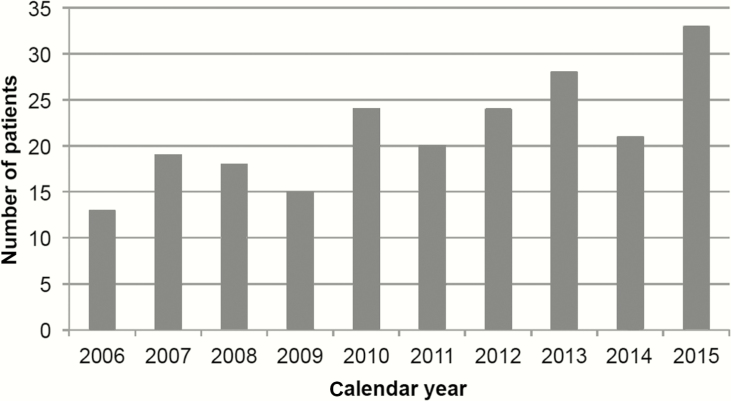

Despite the substantial increase in cART coverage in Malawi, the annual number of new KS diagnoses in HIV-infected children and adolescents has steadily increased over the past decade (Figure 1). The average annual number of new pediatric KS diagnoses from 2006 to 2010 (n = 89) was 17.8 cases per year, compared to 25.2 cases per year from 2011 to 2015 (n = 126).

Figure 1.

Increasing trend in the number of new Kaposi sarcoma diagnoses in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children and adolescents per calendar year at a tertiary care center in Lilongwe, Malawi.

We also compared numbers of new KS diagnoses in HIV-infected children and adolescents from our 2 published cohorts [8, 9]. In the recent cohort, 70 patients were diagnosed with KS over 34 months from 2010 to 2013. That represented 5.2% (70/1359) of all children initiated on cART at our center [9]. The historical control reported 72 patients with KS from 2003 to 2009 (total duration 80 months), representing 3.2% (72/2241) of cART initiations [8]. The older cohort averaged 0.9 new KS diagnoses per month vs 2.1 new KS diagnoses per month more recently.

It is evident that the number of new pediatric KS diagnoses in Malawi is not yet decreasing despite wider availability of cART. Recent data from Blantyre, Malawi, reveal similar numbers [10]. Several factors that may contribute to the current increased numbers of pediatric KS diagnoses include improved referral networks via outreach to regional healthcare professionals, facilities, and patients through our Tingathe Community Outreach Program, improved infrastructure to establish definitive diagnoses via biopsies (especially in lymph node KS), and persistent gaps in access to cART.

Despite xgreat efforts to reduce the severe complications of pediatric HIV infection with cART, KS still remains an important complication in HHV-8–endemic regions of Africa. Our experience has demonstrated that long-term complete remission may be achieved in childhood KS with the combination of relatively moderate chemotherapy and cART [9]. Continued efforts to increase the awareness of pediatric KS may provide great impact in the vision to treat HIV and cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We wish to acknowledge the courage and strength of our patients and their families, fighting a brave battle against both HIV and cancer in the setting of severe limitations in resources. We thank our colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi inclusive of the Tingathe Outreach Program with special gratitude to Drs Maria Kim, Saeed Ahmed, Avni Bhalakia, and Carrie Cox for their constant support. We additionally appreciate the vision and achievements of Drs Mark Kline and Gordon Schutze and our colleagues in the Baylor College of Medicine International Pediatric AIDS Initiative at Texas Children’s Hospital. We express immense gratitude for the support of Dr David Poplack, Kristi Wilson-Lewis, Elise Ishigami, Michael Cubbage, Dr Peter Wasswa, Dr Joseph Lubega, Dr Carl Allen, and our colleagues at the Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Centers and the Global HOPE Program. We are eternally grateful to Dr Carrie Kovarik (University of Pennsylvania) and Dr Dirk Dittmer (University of North Carolina) for their expert support in the pathology and viral pathophysiology of Kaposi sarcoma. We acknowledge the excellent clinical care provided by our many colleagues at Kamuzu Central Hospital, with appreciation for the consummate work of Idah Mtete, Mercy Mutai, Mary Mtunda, and Mary Chasela, as well as the valuable collaboration of our colleagues from the University of North Carolina Project–Malawi, including their expertise and support for the Kamuzu Central Hospital Pathology Laboratory through Professor George Liomba, Dr Satish Gopal, Robert Krysiak, and Coxcilly Kampani.

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support. The work of the pediatric Kaposi sarcoma program at the Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi in Lilongwe was supported in part by the Baylor-UT Houston Center for AIDS Research Core Support (grant number AI36211 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases); the US Agency for International Development through the Tingathe Program (cooperative agreement number 674-A-00-10-00093-00); and philanthropic contributions to purchase chemotherapy from ConocoPhillips.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Pediatric AIDS-Defining Cancer Project Working Group for IeDEA Southern Africa, TApHOD, and COHERE in EuroCoord. Kaposi sarcoma risk in HIV-infected children and adolescents on combination antiretroviral therapy from sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and Asia. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:1245–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martro E, Bulterys M, Stewart JA, et al. Comparison of human herpesvirus 8 and Epstein-Barr virus seropositivity among children in areas endemic and non-endemic for Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Med Virol 2004; 72:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dollard SC, Butler LM, Jones AM, et al. Substantial regional differences in human herpesvirus 8 seroprevalence in sub-Saharan Africa: insights on the origin of the “Kaposi’s sarcoma belt.” Int J Cancer 2010; 127:2395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sinfield RL, Molyneux EM, Banda K, et al. Spectrum and presentation of pediatric malignancies in the HIV era: experience from Blantyre, Malawi, 1998–2003. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007; 48:515–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tukei VJ, Kekitiinwa A, Beasley RP. Prevalence and outcome of HIV-associated malignancies among children. AIDS 2011; 25:1789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rohner E, Valeri F, Maskew M, et al. Incidence rate of Kaposi sarcoma in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Southern Africa: a prospective multicohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:547–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ngalamika O, Minhas V, Wood C. Kaposi’s sarcoma at the university teaching hospital, Lusaka, Zambia in the antiretroviral therapy era. Int J Cancer 2015; 136:1241–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cox CM, El-Mallawany NK, Kabue M, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of HIV-infected children diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma in Malawi and Botswana. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013; 60:1274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Mallawany NK, Kamiyango W, Slone JS, et al. Clinical factors associated with long-term complete remission versus poor response to chemotherapy in HIV-infected children and adolescents with Kaposi sarcoma receiving bleomycin and vincristine: a retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0153335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chagaluka G, Stanley C, Banda K, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in children: an open randomised trial of vincristine, oral etoposide and a combination of vincristine and bleomycin. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50:1472–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]