Abstract

Although emotion regulation has been identified as a key function of non-suicidal selfinjury (NSSI), it is unclear how specific indices of emotion regulation are associated with particular NSSI methods as markers of risk. This study used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify subgroups of individuals who engage in NSSI and their patterns of emotional regulation difficulties. Undergraduate students in the southeastern United States (N= 326) completed an online survey. LCA was used to identify subgroups of individuals engaging in NSSI and their associated emotion regulation difficulties. These subgroups were then compared across a variety of behavioral health outcomes (e.g. impulsive behavior, disordered eating, problematic alcohol use, suicide attempt history) to characterize specific risk profiles. The LCA revealed four subgroups who engage in NSSI and have specific emotion regulation difficulties. These subgroups were differentially associated with behavioral health outcomes, including suicide risk, disordered eating, and impulsive behavior. Results of this research could aid in clinical identification of at-risk individuals.

Keywords: self-injurious behavior; suicide; suicide, attempted; models, statistical; universities; emotions

1. Introduction

A strikingly large percentage of young adults engage in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), with a meta-analysis reporting a lifetime prevalence rate of 13.4% (Swannell et al., 2014). NSSI can be defined as the deliberate destruction of bodily tissue in the absence of suicidal intent (Nock, 2010). In and of itself, engaging in NSSI is associated with significant psychosocial, academic, and occupational difficulties (Nock et al., 2006). Additionally, research has shown that individuals who engage in NSSI are more likely to have a future suicide attempt and tend to have poorer treatment prognoses (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Asarnow et al., 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2011). Considering these negative outcomes, plus the high percentage of young adults who display NSSI behaviors, understanding who is at risk for engaging in NSSI is paramount.

Many studies have examined predictors of NSSI, but very few factors with strong predictive ability have been identified (Fox et al., 2015), likely due to the small amount of variance in NSSI occurance explained by individual predictors. Some variables that have been identified as predictive of NSSI behavior in young adults include depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, female sex, affective dysregulation, and ruminative cognitive styles (Hankin and Abela, 2011; Hoff and Muehlenkamp, 2009; Jacobson and Gould, 2007; Wilcox et al., 2012). Despite the research on NSSI predictors, there is still much that remains unknown about NSSI. Past research has predominately focused on NSSI in a more general manner, looking at overall frequency of self-injurious behaviors and neglecting to consider the type of behavior or frequency of specific behaviors performed (Burke et al., 2015; Guan et al., 2012; Selby et al., 2010; Whitlock et al., 2013), which may lead us to miss important information that can contribute to assessment of risk.

Given that a recent meta-analysis of 365 articles examining 50 years of research found NSSI to be the strongest predictor of suicide attempt (Franklin et al., 2017) and suicide remains the second leading cause of death for young adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), it seems imperative to understand this phenomenon in more depth to enhance suicide prevention efforts. Recent research using latent class analysis (LCA) has provided evidence for subgroups of individuals who engage in NSSI, with each subtype displaying unique suicide risk profiles. LCA is a person-centered statistical technique whereby a heterogeneous group of individuals can be subdivided into smaller homogenous groups with similar traits. Using this approach, Hamza and Willoughby (2013) identified three subgroups of individuals who engaged in NSSI, each with varying degrees of suicide risk. Among the two groups with a high frequency of NSSI, only one was at an increased risk for suicidal behavior, and this high NSSI frequency/high suicide risk group displayed significantly greater impairment on a variety of psychosocial indices compared to the groups at low risk for suicidal behaviors. Similarly, Klonsky and Olino (2008) performed LCA with young adults who engaged in NSSI and found evidence for four distinct groups, each engaging in differing NSSI methods for varying social and automatic functions, and with differing age of onset, depression and anxiety symptoms, borderline personality disorder symptoms, lifetime suicidal ideation, and number of lifetime suicide attempts. Another study found three subgroups of individuals based upon frequency, type, and severity of NSSI behaviors (Whitlock et al., 2008). Lastly, Dhingra et al. (2016) provided evidence for a three-subgroup model in a sample of university students who endorsed a range of self-injurious thoughts and behavior, including suicidal and non-suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts. The first group endorsed high levels across the range of suicidal and non-suicidal thoughts and behaviors (except performing behaviors that may be indicative of suicide desire, even though no desire is present), the second group endorsed high suicidal ideation and high NSSI thoughts and behaviors, and the third group endorsed low levels of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors.

In light of the evidence for varying NSSI subgroups with distinct risk factors, it is surprising more research has not been done on other variables that would help distinguish these groups. Despite being cited as one of the primary reasons why individuals engage in NSSI (Chapman et al., 2006; Nock, 2009; Klonsky, 2007; Taylor et al., 2017), there is limited understanding of how specific features of emotion regulation are associated with methods of NSSI. Identifying such features may inform tailored intervention and prevention programming for suicide risk. Emotion regulation has been defined as a complex process that involves being aware of/understanding emotions, the acceptance of emotions, the ability to control impulsive behaviors and act in accordance to one’s goals in the face of emotional experience, and the ability to utilize appropriate emotion regulation strategies to modulate one’s emotions (Gratz and Roemer, 2004). Theory suggests that when certain individuals experience difficulties with modulating emotions, normal coping mechanisms may not be distracting or regulating enough to reduce negative emotion; therefore, NSSI may be a behavior that is intense enough to serve as a coping mechanism, albeit a malapdative one (Selby and Joiner, 2009). Indeed, empirical research has demonstrated that the top reason why individuals engage in NSSI is to regulate emotional/physical experiences (Nock and Prinstein, 2004).

Numerous other studies in young adults have found an association between emotion regulation difficulties and NSSI (Emery et al., 2016; Heath et al., 2008; Muehlenkamp et al., 2010; Kranzler et al., 2016; Tatnell et al., 2016). In addition to NSSI, emotion regulation difficulties are also related to a number of non-specific behavioral health risks, such as depression, anxiety, substance use, and disordered eating (Aldao et al., 2010; Berking and Wupperman, 2012; Ehring et al., 2008; Tull and Roemer, 2007; Whiteside et al., 2007). Furthermore, research suggests that there are also likely subgroups of emotion regulation difficulties (Labouliere, 2009), and that certain patterns of emotion regulation may mediate treatment response, both for NSSI treatment (Slee et al., 2008) as well as more generally (Berking et al., 2008). However, it remains unclear whether those with specific emotion regulation difficulties have different risk profiles for other behavioral health outcomes. Additionally, despite the research showing a relationship exists between NSSI and emotional dysregulation in general, it remains unknown if certain methods of NSSI are associated with specific aspects of emotion regulation (i.e. non-acceptance of emotional responses; difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behavior; impulse control difficulties; lack of emotional awareness; limited access to emotion regulation strategies; and lack of emotional clarity).

While LCA seems a promising approach for determining profiles of NSSI and emotion regulation difficulties, the studies to date using this technique have all suffered from methodological issues. Although Klonsky and Olino (2008) measured both NSSI and emotion regulation, their measure of emotion regulation was embedded within a larger measure assessing a variety of functions of NSSI, with only three items measuring emotion regulation. These items were then collapsed with other variables to create an “automatic reinforcement” variable that was used to extract the latent classes, thereby obscuring the unique contribution of emotion regulation outside of other automatic reinforcers. Alternatively, other researchers using LCA to classify NSSI behaviors (Hamza and Willoughby, 2013; Whitlock et al., 2008), did not include measurement of emotion regulation at all when extracting latent classes.

Given that both NSSI and emotion regulation are interconnected, multifaceted constructs that have subtypes with differential prognoses, research examining these constructs in isolation or not breaking constructs into their relevant subtypes likely obscured critical details and limited our understanding. Identifying groups of individuals who experience different types and frequency of NSSI and different aspects of emotion regulation difficulties would be extremely informative for NSSI prediction, assessment, and treatment. Additionally, determining if persons with specific types or frequencies of NSSI behaviors or emotion regulation difficulties displayed higher levels of suicidality could help clinicians better identify clients at elevated risk and enhance current suicide prevention strategies. The present study aimed to address these gaps by using LCA to identify latent classes based on the frequency of different types of NSSI behavior and specific aspects of emotion regulation. We hypothesized that diverse classes would have distinct differences in the frequency of types of NSSI behavior performed and in specific emotional regulation difficulties. We also hypothesized that suicide-related factors (acquired capability for suicide, history of suicide attempts) would differ between classes. Lastly, it was hypothesized that classes would be differentially associated with behavioral health outcomes, such as impulsive behavior, problematic alcohol use, and disordered eating.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants in this project were recruited from a larger study of college study risk behaviors (N=1221; Labouliere, 2013); data reported in this study were those of the participants endorsing lifetime NSSI (26.7% of the total sample). Participants were undergraduate college students from the southeastern United States. In order to participate in the study, participants had to be age 18 or older, able to speak and read English, and be registered as a full- or part-time undergraduate student. Three-hundred sixty-nine participants endorsed a history of NSSI behavior; of these 369, 327 had complete data on the frequency of specific NSSI behaviors and were thus included in analyses. One participant was removed due to having extreme outlier values (e.g., over three standard deviations above the mean for certain rare NSSI behaviors), resulting in a final analysis sample of 326 participants. Approximately 75% were female (n=244) and their ages ranged from 18 to 51, with a mean age of 21.33 (SD=4.16 years). Nearly 39% of the sample identified as Hispanic or Latinx; 70.4% identified as Caucasian or European American, 11.3% Black or African American, 4.7% Asian or Asian American, 6.9% another racial group, and 6.6% multiracial. Nearly 79% reported more than one episode of NSSI in their lifetime, 33.4% reported engaging in NSSI within the past two years, and 8.0% reported NSSI severe enough to require medical attention.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics.

Information on participants’ age, year in school, and racial and ethnic identities were gathered.

2.2.2. Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI).

The DSHI (Gratz, 2001) is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses the presence, frequency, duration, and types of different NSSI behaviors, including cutting, burning, scratching, banging, and other NSSI behaviors. For each type of self-harm behavior, participants are asked whether they have ever engaged in that behavior (yes/no); for each endorsed NSSI behavior, participants are also asked to respond with age of onset, number of total times they have engaged in that specific behavior (frequency), their most recent engagement in the behavior, total number of years engaging in the behavior (duration), and if they have ever required medical attention following a given NSSI episode (Gratz, 2001). Participants were included in the sample if they endorsed lifetime engagement in any of the 17 NSSI behaviors; frequency scores were utilized in all LCA analyses. The measure has strong internal consistency in college samples (Gratz, 2001; Gratz and Roemer, 2004; α=0.82 in this sample), and has been shown to have good test-retest reliability and construct validity.

2.2.3. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

The DERS (Gratz and Roemer, 2004) is a 41-item self-report measure that assesses clinically-significant difficulties in emotion regulation, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “almost never” (1) to “almost always” (5). Six distinct subscales of emotion regulation difficulties can be derived from the scale: non-acceptance of emotional responses; difficulties in engaging in goal-directed behavior; impulse control difficulties; lack of emotional awareness; limited access to emotion regulation strategies; and lack of emotional clarity. The DERS has established reliability and validity for total and subscale scores in both clinical and community samples (Gratz and Roemer, 2004; total α=0.93 and subscale range= 0.82 to 0.92 in this sample).

2.2.4. Suicide-related factors.

Acquired capability and suicide attempt history were examined using the Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale (ACSS; Bender et al., 2007) and the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ; Gutierrez et al., 2001) respectively. The ACSS is composed of 5 items assessing an individual’s fearlessness surrounding lethal self-injury, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all like me” (1) to “very much like me” (5). The ACSS shows adequate reliability and validity (Bender et al., 2007; Van Orden et al., 2008; α=0.79 in this sample). Suicide attempt history was measured using the question assessing presence or absence of a suicide attempt from the SHBQ suicide attempts subscale. The full SHBQ is a 32-item self-report questionnaire assessing suicide-related thoughts and behaviors across four domains (intentional non-suicidal self-harm, suicide attempts, suicide threats; and suicide ideation) and gathers information on frequency, age of onset, recency, disclosure, and whether medical attention was required. The SHBQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Fliege et al., 2006; Gutierrez et al., 2001; α subscale range = 0.87 to 0.98 in this sample).

2.2.5. Behavioral health factors.

Other behavioral health variables used for class validation included impulsive behavior as assessed by the UPPS Impulsivity Scale (UPPS; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001), problematic alcohol use as assessed by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) and disordered eating as assessed by the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn and Beglin, 1994). The UPPS is a 59-item self-report measure assessing five distinct facets of impulsivity: negative urgency; positive urgency; lack of premeditation; lack of perseverance; and sensation-seeking. The measure utilizes a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “agree strongly” (1) to “disagree strongly” (4), and has well-established psychometrics in both community and clinical samples (Whiteside and Lynam, 2001; Whiteside et al., 2005; α subscale range = 0.84 to 0.95 in this sample).The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure assessing alcohol consumption, drinking behavior, and alcohol-related problems, where items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4, with higher numbers reflecting a higher likelihood of problematic alcohol use. The AUDIT has strong psychometrics established in both domestic and international clinical and community samples (Allen et al., 1997; Reinert, 2002; Saunders et al., 1993; α=0.83 in this sample). Lastly, the EDE-Q is a 41-item self-report measure assessing disordered eating, where items are scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 to 6, with higher numbers representing a higher frequency of disordered eating behaviors. The EDE-Q has good psychometrics in both clinical and community samples (Fairburn and Beglin, 1994; Grilo et al., 2001; Passi et al., 2003; α=0.81 in this sample).

2.3. Procedure

Participants were recruited through a university online recruiting system and data collection software and received psychology course credit for participation. The study was advertised as a general study on mental health and risk behaviors; no specific information was provided regarding the focus on NSSI. Study information was posted online and undergraduate students who met inclusion criteria were allowed to participate. Participants provided informed consent electronically, then completed all self-report measures, which were presented in random order. After completing a measure, participants were not allowed to go back and alter their responses. Depending on their responses, completion of the study took between 30-45 minutes. After completion of all measures, a debriefing page informed participants of the purpose of the study, along with contact information for the principal investigator and local mental health services. All data were de-identified and assigned a random identifier code prior to analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida.

2.4. Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate statistical assumptions such as normality. Variables which violated statistical test assumptions (e.g., scratching, skin piercing, cutting, and burning NSSI behavior) were log-transformed to approximate normality. Due to high levels of collinearity between NSSI behavior types, exploratory factor analysis utilizing an oblique rotation was used to distill endorsement of individual NSSI behavior items from the DSHI into factors for analysis. This resulted in five factors identified through eigen values >1, scree plot, and conceptual relevance (see Supplemental Table 1): scratching and skin piercing (e.g., severely scratching, sticking pins/staples into, or biting the skin to the point of bleeding), cutting (e.g. cutting parts of the body or carved words/pictures into the skin), banging or bruising (e.g., punching the body or another object, banging head or body part to the point of bruising), burning (e.g., burning the skin with a lighter, match, or cigarette), and use of implements (e.g. rubbing sandpaper on the body, dripping acid on the skin, or irritating skin with bleach/other noxious chemicals). Although internal consistency for individual subscales was low, this is not unexpected when there is limited variability in endorsement for each item. As well, item composites may more broadly describe components of NSSI due to the greater diversity of behaviors covered (Boyle, 1991).

Latent class analyses were run using Mplus Version 8, using the Mixture model function (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2017). The Mixture model handles missing data using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2017). Frequency of different types of NSSI behavior (DSHI)1 and levels of different emotion regulation difficulties (DERS) were used to characterize classes. Initially, data were fit to a one-class model to calculate baseline fit indices. Relative model fit was evaluated using standard fit indices recommend in the literature, including the Akaike information criteria (AIC), Bayesian information criteria (BIC), sample-size-adjusted Bayesian information criteria (adj-BIC), the parametric bootstrapped likelihood test (LRT), and entropy values (Nylund et al., 2007). A model was deemed to have relatively better fit if there were significant decreases in AIC, BIC, and adj-BIC values, a significant LRT, and increases in entropy values in comparison with the prior class solution (Nylund et al., 2007). We also evaluated posterior probabilities developed from each class solution (near 1.0) and interpretability of classes.2 The number of classes was added iteratively (e.g. one versus two class solution) until there were no more significant improvements in fit and all class solutions were readily interpretable and distinct.

To identify specific sources of variation characterizing each class, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in demographic factors, suicide risk, and other negative mental health outcomes across classes. To control for multiple comparisons, family-wise modified Bonferroni corrections were utilized for all class characterization post-hoc testing, and Cohen’s d was calculated to quantify the strength of significant differences between classes (small: 0.5 > d >= 0.2; medium: 0.8 > d >= 0.5; large: d >= 0.8; Cohen, 1988). Due to the exploratory nature of class validation analyses, no further statistical corrections were applied.

3. Results

3.1. Latent Class Analyses

Based on iterative LCAs, the best fitting model was the four-class solution, which fit significantly better than one, two, or three class solutions (see Table 1). Five- and six-class solutions were also evaluated but could not be specified due to poor fit. The four-class solution also demonstrated very strong posterior probabilities (0.91-1.00; see Table 2). The largest class was Class 4 (n = 238, 73%), followed by Class 2 (n = 67, 21%), Class 3 (n = 12, 4%), and Class 1 (n = 8, 2%). Although Classes 1 and 3 were small, attempts to collapse these participants into another class were unsuccessful, as they continued to separate into unique classes in the solutions with fewer classes. Based on these results and the classes’ clinical and conceptual relevance, Classes 1 and 3 were retained for further analyses.

Table 1.

Fit indices for the latent class analysis of different types of NNSI behaviors and emotion regulation difficulties.

| Number of Classes | df | AIC | BIC | adj-BIC | Entropy | Bootstrapped LRT, p-value | Significant Change in Fit? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | 22 | 15344.67 | 15427.99 | 15358.20 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Two | 34 | 14766.9 | 14895.66 | 14787.81 | 0.9 | 601.77, p < 0.001 | Yes |

| Three | 46 | 14382.06 | 14556.25 | 14410.35 | 0.94 | 408.84, p < 0.001 | Yes |

| Four | 58 | 14035.45 | 14255.09 | 14071.11 | 0.96 | 370.61, p < 0.001 | Yes |

| Five | Could not be specified | ||||||

| Six | Could not be specified | ||||||

Note: N=326. A model was deemed to have better fit if there were significant decreases in AIC, BIC, and adj-BIC values, a significant LRT, and increases in entropy values in comparison with the prior class solution. Df = Degrees of freedom; AIC = Akaike information criteria; BIC = Bayesian information criteria, adj-BIC = sample-size-adjusted Bayesian information criteria; LRT = parametric bootstrapped likelihood test.

Table 2.

Classification Posterior Probabilities

| Class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

3.2. Class Characterization

Several NSSI behavior types (scratching and skin piercing, cutting, and burning) did not meet normality assumptions; log transformations were used to achieve normality for these variables. However, as results from analyses using transformed and non-transformed variables did not differ significantly, non-transformed results are presented to facilitate interpretation. Based on Bonferroni-corrected one-way ANOVAs, the classes were characterized as: moderate emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of cutting and burning behavior (Class 1); high emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of scratching/skin piercing, banging or bruising, and cutting behaviors (Class 2); moderate levels of emotion regulation difficulties with elevated scratching/skin piercing behaviors and low levels of using implements (Class 3); and low emotion regulation difficulties with low frequency of all NSSI types (Class 4). There were no demographic differences between classes (see Table 3 for descriptive statistics).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

| Total (N=326) | Range | 1 (n=8) | 2 (n=67) | 3 (n=12) | 4 (n=231) | Statistical Testing | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 244 (75%) | - | 4 (50%) | 51 (76%) | 10 (83%) | 179 (75%) | χ2(3,N=326)=3.14, p = 0.37 | N/A |

| Male | 82 (25%) | 4 (50%) | 16 (24%) | 2 (17%) | 60 (25%) | |||

| Agea | 21.33 (4.16) | 18–51 | 21.75 (3.66) | 21.04 (4.30) | 23.17 (5.08) | 21.31 (4.08) | F3,322=0.92, p = 0.43 | N/A |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 123 (38%) | - | 4 (50%) | 22 (33%) | 6 (50%) | 91 (39%) | χ2(3,N=3i8)=2.10, p = 0.55 | N/A |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 203 (62%) | 4 (50%) | 45 (67%) | 6 (50%) | 140 (61%) | |||

| Race | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 224 (69%) | - | 7 (88%) | 41 (61%) | 9 (75%) | 167 (72%) | χ2(18,N=318)=27.03, p = 0.08 | N/A |

| Black or African-Amer. | 25(11%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (8%) | 3 (25%) | 28 (12%) | |||

| Asian or Asian-Amer. | 15 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (3%) | |||

| Another Race | 22 (8%) | 1 (12%) | 7 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (6%) | |||

| Multiracial | 21 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (7%) | |||

| Frequency by Type of NSSI Behavior | ||||||||

| Scratching/Skin Piercing | 11.40 (30.22) | 0-270 | 9.25 (19.65) | 29.01 (52.93) | 27.92 (47.23) | 5.70 (14.90) | F3,322 = 12.91, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

| Banging/Bruising | 6.00 (15.31) | 0-100 | 15.13 (22.90) | 13.75 (26.70) | 3.50 (5.68) | 3.65 (8.93) | F3,322 = 9.32, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

| Cutting | 5.60 (14.66) | 0-108 | 22.63 (39.06) | 11.49 (18.91) | 5.25 (11.54) | 3.39 (10.90) | F3,322 = 9.75, p < 0.001 | 1, 2 > 4 |

| Burning | 0.75 (2.71) | 0-20 | 15.75 (3.99) | 0.76 (1.85) | 0.92 (1.83) | 0.23 (0.79) | F3,322 = 383.64, p < 0.001 | 1 > 2, 3 |

| Using Implements | 0.05 (0.29) | 0-3 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.33 (0.78) | 0.00 (0.00) | F3,322 = 330.82, p < 0.001 | 3 > 1, 2, 4 |

| Emotion Regulation | 2.38 (0.65) | 1.11-4.42 | 2.39 (0.78) | 3.33 (0.39) | 2.46 (0.45) | 2.11 (0.43) | F3,325 = 140.38, p < 0.001 | 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Difficulties | 3 > 4 | |||||||

| Non-acceptance | 2.31 (0.98) | 1.00-5.00 | 2.46 (1.17) | 3.35 (0.96) | 2.50 (0.80) | 2.00 (0.76) | F3,321 = 48.10, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

| Goal-directed activities | 3.01 (0.98) | 1.00-5.00 | 2.25 (0.98) | 4.04 (0.61) | 2.73 (0.74) | 2.76 (0.87) | F3,321 = 45.62, p < 0.001 | 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Impulse control | 2.13 (0.91) | 1.00-4.83 | 2.17 (1.06) | 3.40 (0.72) | 2.17 (0.74) | 1.78 (0.60) | F3, 321 = 111.86, p < 0.001 | 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Awareness | 2.37 (0.80) | 1.00-4.67 | 2.98 (0.73) | 2.61 (0.75) | 2.74 (0.77) | 2.26 (0.79) | F3,321 = 6.11, p < 0.001 | n.s.1 |

| Coping strategies | 2.30 (0.90) | 1.00-5.00 | 2.14 (0.96) | 3.60 (0.65) | 2.26 (0.66) | 1.94 (0.57) | F3,321 = 132.42, p < 0.001 | 2 > 1, 3, 4 |

| Emotional clarity | 2.29 (0.80) | 1.00-5.00 | 2.43 (1.12) | 2.94 (0.74) | 2.50 (0.57) | 2.09 (0.72) | F3,3215 = 24.71, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

Note: N=326. All total and class values represent M(SD) for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables, unless otherwise denoted.

Omnibus testing suggested significant differences between classes, but these differences did not remain significant after modified Bonferroni correction.

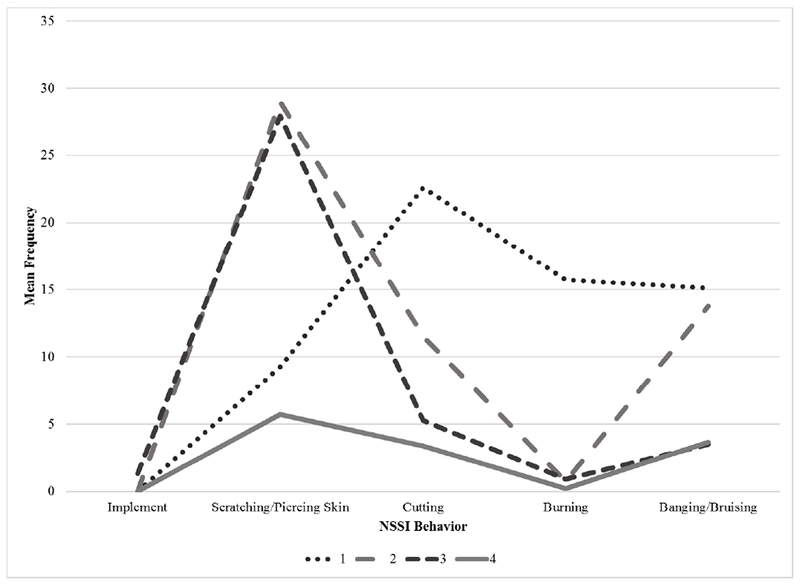

Class 1 had high frequencies of cutting and burning behaviors, moderate frequencies of banging/bruising and scratching/skin piercing behaviors, and no endorsement of using implements. Participants in Class 1 endorsed significantly higher frequencies of cutting (d = 0.67) and burning (d = 5.40) behavior than Class 4, the class with low emotion regulation difficulties and low frequency of all NSSI types. Class 1 also endorsed significantly higher frequency of burning behaviors than Classes 2 (d = 4.82) and 3 (d = 4.78; see Table 3). Class 2 had high frequency of scratching/skin piercing behaviors, moderate frequencies of banging/bruising and cutting behaviors, and very low or no endorsement of burning behavior and using implements. Participants in Class 2 endorsed significantly higher frequencies of scratching/skin piercing (d = 0.60), banging or bruising (d = 0.51), and cutting (d = 0.52) behaviors than Class 4. Class 3 had high levels of scratching/skin piercing behavior, low levels of cutting, banging/bruising behavior, and using implements, and very low or no endorsement of burning behavior. Participants in Class 3 endorsed significantly higher frequencies of implement use for NSSI than Classes 1 (d = 2.41), 2 (d = 2.41), and 4 (d = 2.41). Class 4 had low levels scratching/skin piercing, banging/bruising, and cutting behaviors, and very low or no endorsement of burning behavior or using implements. Participants in Class 4 endorsed significantly lower rates of: cutting (d = 0.67) and burning (d = 5.40) behavior than Class 1; scratching/skin piercing (d = 0.60), banging/bruising (d = 0.51), and cutting (d = 0.52) behaviors than Class 2; and using implements (d = 2.41) than Class 3 (see Table 3 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NSSI Behavior Profiles

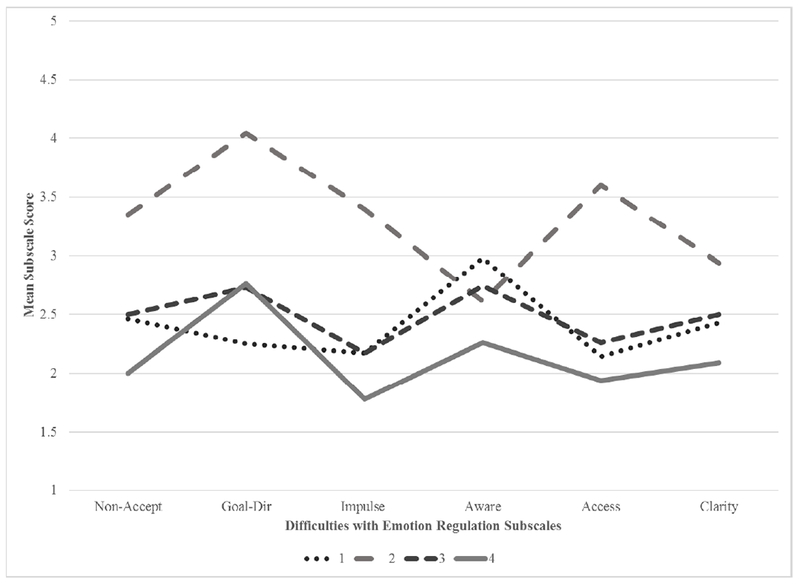

Participants in Class 2 had significantly higher endorsement of non-acceptance of their emotional responses (d = 1.56) and lack of emotional clarity (d=1.16) than Class 4, and greater difficulty in engaging in goal-directed behavior (1: d = 2.19; 3: d = 0.96; and 4: d = 1.56), impulse control difficulties (1: d = 1.37; 3: d = 1.68; and 4: d = 1.01), and limited access to coping strategies (1: d = 1.78; 3: d = 2.05; and 4: d = 2.72) than all classes. No other significant differences in emotion regulation difficulties were present between classes (See Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Emotion Regulation Profiles

3.3. Class Validation

3.3.1. Suicide-related factors.

There was a significant difference between classes in acquired capability for suicide, wherein Class 1 was significantly higher than all other classes (2: d = 0.25, 3: d = 1.34; and 4: d = 0.53; see Table 4). However, although Class 1 demonstrated significantly higher acquired capability, they did not display a significantly higher rate of suicide attempts; rather, only Class 2 had significantly greater likelihood of suicide attempt than Class 4 (χ23,N=326 = 15.37, p < 0.005; φ = .21, p < 0.05), although we may have been underpowered to detect significant differences, as Class 1 had the highest proportion of individuals with a suicide attempt history (37.5%). There were no other significant differences between classes.

Table 4.

Class Validation.

| Total (N=326) | Range | 1 (n=8) | 2 (n=67) | 3 (n=12) | 4 (n=231) | Statistical Testing | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide-related factors | ||||||||

| Acquired capability | 1.96 (1.02) | 0.00-4.00 | 3.19 (0.66) | 2.11 (1.10) | 1.72 (0.54) | 1.87 (0.98) | F3.326 = 5.14, p < 0.01 | 2 > 1, 2, 3 |

| History of suicide attempts | 53 (16.3%) | - | 3 (37.5%) | 20 (29.9%) | 2 (16.7%) | 28 (11.7%) | χ23,N=326 = 15.37, p < 0.01 | 2 > 4 |

| Behavioral health factors | ||||||||

| Impulsivity | ||||||||

| Negative urgency | 2.41 (0.59) | 1.25-3.92 | 2.58 (0.75) | 2.82 (0.50) | 2.29 (0.66) | 2.26 (0.54) | F3,226 = 15.26, p < 0.001 | 2 > 3, 4 |

| Positive urgency | 1.94 (0.69) | 1.00-4.00 | 2.41 (0.77) | 2.24 (0.71) | 2.07 (0.92) | 1.80 (0.62) | F3,226 = 7.65, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

| Lack of premeditation | 1.94 (0.48) | 1.00-3.82 | 2.26 (0.45) | 2.10 (0.53) | 1.73 (0.53) | 1.88 (0.43) | F3,226 = 5.01, p < 0.01 | 2 > 4 |

| Lack of perseverance | 1.96 (0.51) | 1.00-3.70 | 2.08 (0.50) | 2.32 (0.52) | 1.88 (0.34) | 1.82 (0.45) | F3,226 = 15.98, p < 0.001 | 2 > 4 |

| Sensation seeking | 2.87 (0.65) | 1.08-4.00 | 3.49 (0.35) | 2.87 (0.60) | 2.60 (0.73) | 2.86 (0.66) | F3,226 = 3.03, p < 0.05 | 1 > 3, 4 |

| Problematic alcohol use | 0.69 (0.60) | 0.00-2.80 | 0.91 (0.61) | 0.83 (0.79) | 0.71 (0.77) | 0.62 (0.49) | F3,229 = 2.04, p = 0.11 | n.s. |

| Disordered eating | 1.87 (1.49) | 0.00-5.65 | 2.25 (1.30) | 2.46 (1.74) | 2.07 (1.27) | 1.63 (1.35) | F3,226 = 4.82, p < 0.01 | 2 > 4 |

Note: N=326. All total and class values represent M(SD).

3.3.2. Behavioral health factors.

Classes showed additional significant differences in behavioral health factors. For impulsive behavior, there were significant differences between classes, in that Class 2 had significantly higher levels of negative urgency than Classes 3 (d = 0.75) and 4 (d = 0.86), and higher levels of positive urgency (d = 0.66), lack of premeditation (p < 0.05), and lack of perseverance (d = 0.55) than Class 4. Class 1 had higher levels of sensation seeking than Classes 3 (d = 1.55) and 4 (d = 1.19); there were no other significant differences between classes in impulsivity.For disordered eating, there was a significant difference between classes in that Class 2 had significantly higher levels of disordered eating than Class 4 (d = 0.53). No significant differences between classes were found for problematic alcohol use (See Table 4 for all class validation statistics).

3.3.3. Summary.

Based on the class validation analyses, it was determined that Classes 1 and 2 conferred the most significant adverse outcomes. Participants in Class 1, who experienced moderate emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of cutting and burning behavior, also had significantly higher levels of acquired capability for suicide and impulsive sensation-seeking. Participants in Class 2, who experienced high emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of scratching/skin piercing, banging or bruising, and cutting behaviors, also had significantly higher endorsement of suicide attempts, disordered eating, and specific facets of impulsive behavior, including negative and positive urgency and a lack of premeditation and perseverance. Although Participants in Class 3 endorsed high levels of scratching/skin piercing behavior, had higher endorsement of using implements than other classes, and had significantly higher emotion regulation difficulties than Class 4, Class 3 mostly was not distinguishable from Class 4 in regard to behavioral health factors. Both Classes 3 and 4 conferred relatively lower risk for suicide-related factors, impulsive behavior, and disordered eating. Problematic alcohol use was endorsed at low rates in this sample and did not differentially associate with specific classes.

4. Discussion

This study presents an initial exploration of the associations between subtypes of NSSI behavior and emotion regulation difficulties. Notably, four classes were identified that showed different patterns of emotion regulatory capacity, distinct rates of NSSI behavioral subtypes, and unique profiles of associated risk (e.g. suicide attempt history, disordered eating symptoms, impulsivity). As NSSI is a prevalent form of maladaptive coping and predictive of serious, negative long-term outcomes (Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Franklin et al., 2017; Hasking et al., 2008; Whitlock et al., 2006), these findings inform our understanding of potential associated mental health risks within this heterogeneous population, and will improve appropriate identification, referral, and treatment for those at highest risk.

As expected, latent classes showing higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties also had higher frequencies of NSSI behaviors and a greater diversity of NSSI behavior types. This is congruent with past literature finding that emotion regulation difficulties are positively associated with NSSI behavior frequency and diversity (Gratz and Chapman, 2007; Jenkins and Schmitz, 2012). Clinicians should be aware of how greater emotion regulation difficulties may indicate greater risk for engagement in NSSI. Similarly, individuals who report a greater diversity of NSSI methods and higher frequency of engagement may benefit from additional support to improve emotion regulation. Future research should further explore the degree to which these associations between emotion regulation difficulties and NSSI behavior frequency and diversity impact treatment outcomes.

When considering specific classes, emotion regulation difficulties and number of NSSI methods appeared to describe a continuum of risk. Interestingly, Class 2 (high emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of scratching/skin piercing, banging or bruising, and cutting behaviors) had a more severe risk profile than other classes (i.e. significantly higher rates of suicide attempt, disordered eating, and impulsivity). As Class 2 was the second largest class in the sample, clinicians should be aware of this more severe risk profile when working with clients exhibiting high emotion regulatory difficulties and elevated frequency of scratching/skin piercing, banging or bruising, and cutting NSSI behaviors, as these individuals may be at even greater risk of negative outcomes due to their higher associated impulsive behavior. While cutting behaviors are frequently studied, past research on banging/bruising and scratching/skin piercing behaviors has been limited and predominantly focused on individuals with developmental disabilities (Favazza and Rosenthal, 1993; Rojahn et al., 2001). In light of the elevated levels of emotion regulation control difficulties and impulsivity, individuals displaying features of Class 2 (moderate-to-high scratching, cutting, banging and bruising) may benefit from improved distress tolerance skills to decrease NSSI frequency and suicide risk, such as skills involving building greater emotional awareness, acceptance of discomfort, and diversifying positive coping skills (Linehan, 2014). Future studies should further explore the function and characteristics of such behaviors to better understand these behaviors in other clinical populations and inform specific intervention strategies.

Two classes with moderate emotion regulation difficulties represented small proportions of the sample (Class 1 (2.4%): moderate emotion regulation difficulties with elevated frequency of cutting and burning behavior; and Class 3 (3.7%): moderate levels of emotion regulation difficulties with elevated scratching/skin piercing behaviors and low levels of using implements). The small sizes of these classes is likely reflective of a lower prevalence of moderate emotion regulation difficulties among individuals who engage in NSSI; rather, those with frequent NSSI behaviors also tended to display greater emotion regulation difficulties, whereas those with low levels of NSSI endorsement also tended to endorse fewer emotion regulation difficulties. However, despite the smaller proportions associated with Classes 1 and 3, the inclusion of these classes was important for satisfactory model fit, implying that they identify important variation in the data. Further, despite its small size, class 1 also conferred significant risk for adverse mental health outcomes (e.g., greater acquired capability for suicide and impulsive behavior). Given the importance of these small classes, future research may wish to recruit larger samples to better understand the NSSI experiences of individuals with moderate levels of emotion regulation difficulties.

Interestingly, although participants in Class 1 endorsed only moderate levels of emotion regulation difficulties, they also demonstrated the highest level of acquired capability for suicide. Past research shows that emotion regulation difficulties are more closely associated with suicidal desire than with acquired capability (Anestis et al., 2011). It is possible that individuals with higher levels of emotion regulation may report suicidal ideation more frequently but be less likely to act on these thoughts. As acquired capability for suicide has been identified as important contributor to suicide attempt when an individual is experiencing suicidal desire, clinicians may wish to further assess acquired capability among individuals showing moderate levels of emotion regulation even if suicidal desire is not disclosed.

It is also possible individuals in Class 1 would be more likely to engage in risky behaviors due to their elevated levels of sensation seeking in comparison with other groups. Although a relatively smaller portion of the larger sample, clinicians may wish to be attentive to the constellation of higher frequencies of burning and cutting behaviors and elevated sensation seeking as potential markers for acquired capability. Use of lethal means counseling, a set of strategies for limiting access to lethal means during periods of distress (Johnson et al., 2011), may help to mitigate risk among this group who may engage quickly in suicidal behaviors when in distress. In addition, skills targeting mindfulness practice may help reduce impulsive NSSI in this group, as mindfulness-based practices have been associated with reductions in impulsive behaviors in other populations (Dixon et al., 2018).

Unexpectedly, there were no differences between classes on alcohol use. Although many individuals report using alcohol while engaging in NSSI, the extant literature shows only small associations between alcohol use and NSSI (Nock et al., 2009; Williams and Hasking, 2010). As past research shows alcohol use is associated with emotion regulation difficulties (Dvorak et al. 2014), it is possible that individuals who use alcohol to manage difficult emotions are a separate group from individuals engaging in NSSI. Within the current sample, our ability to detect associations with alcohol use were limited by a restricted range in alcohol use severity scores, with very few individuals screening positive for problematic alcohol use. In addition, we did not assess the use of other substances (e.g. marijuana, opioids) that may have impacted our ability to detect associations with substance abuse more broadly. Future studies should further better disentangle substance use-NSSI relationships and associated risk.

This study had several limitations that impact interpretation of findings. First, the study was cross-sectional, thus precluding inferences regarding directionality, causality, or the ability to determine whether classes derived in this study are stable over time. The study was also reliant on self-report, and thus subject to associated biases including social desirability and inaccurate reporting on past events; however, all surveys were anonymous to facilitate honest reporting of mental health difficulties. Likewise, it is possible how the study was marketed could have influenced response rates. Although the study was advertised as a general study on “mental health and risk behavior” and no explicit information was provided regarding assessment of specific constructs (e.g., NSSI, affect regulation, suicide history, disordered eating, problematic alcohol use, or impulsive behavior), it is possible that participants could have inferred that some of these indicators may be included based on the descriptor “risk behavior” and thus been more or less likely to participate, resulting in some degree of selection bias. Indeed, participants endorsed NSSI represented 26.7% of the sample recruited for the large study of risk behavior. While this percentage is elevated compared with some studies conducted with young adults (12.8%, Kuentzel et al., 2012; 13.4%, Swannell et al., 2014; 14.7%, Muehlenkamp et al., 2013; 15.3%, Whitlock et al., 2011; 17%, Whitlock et al., 2006), it is lower than lifetime rates reported in other college samples (29.5%, Goldstein et al., 2009; 30%; Labouliere, 2009; 37%, Gratz, 2006; 38%, Gratz et al., 2002; 38.9%, Cerutti et al., 2012; 41%, Paivio and McCulloch, 2004; 44%, Gratz and Chapman, 2007). As such, we do not believe that how the study was advertised unduly influenced response rates, but it is possible that selection bias may have somehow influenced results. Furthermore, our measures of suicide-related factors were limited to acquired capability and a history of suicide attempt, which may not have been the strongest indicators of future suicide risk (e.g., Franklin et al., 2017) and may have neglected other theoretically-relevant constructs (i.e., thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, hopelessness, etc.). Future studies should utilize more thorough measurement of suicide-related factors when examining associations between NSSI, emotion dysregulation, and suicide risk.

Finally, our sample was relatively small, consisted of only college students, and had limited diversity. Thus, our ability to detect less common NSSI classes may have been impacted, and findings for small class sizes may not be as readily replicable or generalizable to other populations. While the general consensus for latent class analysis is often that classes should be larger than 5% of the sample, 5% is not considered a hard cut-off and there is considerable debate within the field as to the how the number of classes should be selected (Galfalvy & Hwei, 2018; Hooker, 2018; Nylund et al., 2007). Common reasons for concern over small class sizes is that models including small class sizes are less likely to converge (Nylund et al., 2007), and when they do, small classes may not actually represent a true separate class, just several outliers from other classes that happened to look similar. A way to determine whether small classes actually represent a distinct group is to examine posterior probabilities, which show the certainty of class membership for participants in each class. If posterior probabilities for small classes are strong, this suggests that the smaller classes represent distinct groups. Such a decision is further supported when the inclusion of smaller classes improves model fit (i.e., suggesting that the classes represent important variance in the data) and interpretability (i.e., classes show significantly different patterns of associations that would be obscured by collapsing the smaller classes; Geiser, 2011; see Houston et al., 2011 and Rodgers et al., 2014 for examples of research with small classes retained).

Given that our models converged easily and have superior fit to models using fewer classes, and the small classes in our data have very strong posterior probabilities, provide unique clinical risk information, and enhance conceptual clarity, we elected to retain the four-class solution as we were interested in exploring the full natural variation in a community sample. While representing only a small number of individuals and percentage of the sample, these small class sizes were differentially-associated with important clinical concerns: higher acquired capability for suicide and high rates of suicide attempt (class 1) and lower endorsement of sensation seeking and negative urgency (class 3), common targets of treatment for NSSI. Collapsing these categories would unnecessarily obscure potential clinical implications; for example, clinicians treating patients with frequent cutting and burning behavior may consider more frequent assessment of suicide risk, while clinicians treating patients with high implement use may want to explore additional functions and drivers of NSSI in treatment. While the numbers associated with these classes is small, it is to be expected that suicide risk may only be prevalent in a small percentage of college samples; nevertheless, identifying better, more nuanced approaches to detection of suicide risk is direly needed (Large et al., 2017).

Of course, these small classes should be interpreted with caution, given that small classes may be less reliable and generalizable to different samples and this is the first study of its kind to derive latent classes of NSSI behaviors and emotion regulation difficulties. Replication studies with new samples would be indicated before the validity of the class structure could be well-supported. In addition to replication studies, future research should also examine whether classes remain stable in both community and clinical samples and during other developmental stages (e.g., children, adolescents, older adults). This research will be vital for establishing reliable and valid indicators of risk based on NSSI and emotion regulation. However, so long as clinicians are cautious regarding the generalizability of these findings to their clients, it is likely that these results could help inform clinical decision-making and guide interventions.

In spite of these limitations, this study provided a first examination of the associations between different types of NNSI behavior and emotion regulation difficulties, as well as other behavioral health factors associated with these classes. Future research should consider recruitment of larger samples with a broader range of psychosocial measures to better inform our understanding of complex emotion regulation-NSSI relationships and determine the replicability of our findings. Additionally, longitudinal research would help to determine the stability of class membership over time and determine prospective associations with suicide risk. Lastly, we did not evaluate factors that may be protective against NSSI engagement, emotion regulation difficulties, and associated adverse mental health outcomes. For example, Class 4, which had the lowest associated risks, was also the largest class identified within our sample. It is possible that there are unique characteristics within Class 4 that mitigated risk and could inform future prevention programming and intervention development.

With regards to clinical practice, NSSI is a common reason for treatment referral and understanding of NSSI-ER associations will be inform assessment and treatment planning. Knowledge of class membership may better inform differential screening (i.e., suicide screening for classes 1 and 2 versus disordered eating for 2, etc.). Clinicians working with clients engaging in NSSI should comprehensively evaluate methods of NSSI, emotion regulation difficulties, impulsivity, and disordered eating to better understand a given individual’s risk profile across the spectrum of maladaptive coping behaviors and associated features. Use of graphical methods may help to facilitate interpretation of risk profiles, inform case conceptualization, and enhance psychoeducation regarding suicide risk (see example; McCullough et al., 2016).

Future research is needed to replicate our findings which could inform specific treatment algorithms based on risk profiles. Such profiles may reduce workload and provide guidance on specific targets of intervention, as targeting emotion regulation difficulties may help a number of risky behaviors. Researchers should consider exploring optimal strategies for utilizing information on emotion regulation difficulties and NSSI behaviors for clinical decision making. In particular, it remains unclear if treatment tailored to risk profiles improves treatment outcomes and if such types of treatments are appetitive to clinicians and their clients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Four subgroups who engage in NSSI were identified using latent class analysis

Subgroups had differing emotional regulation difficulties

Subgroups were associated with a variety of negative mental health outcomes

Subgroups had distinct suicide risk profiles

Acknowledgments

Funding: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. Dr. Chen’s work was supported in part by a Trans NUT Emergency Care Research K12 Career Development Award (5K12HL133115-02). This material is also the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, OR. Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers L30 MH114339 (PI: Labouliere) and T32 MH016434 (PI: Marsh; T32 postdoctoral fellowship to support Dr. Labouliere’s work). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Frequency data were selected for inclusion in latent class analyses as the data had greater variability and was more normal distributed in our sample than either number of NSSI methods utilized or duration of NSSI behavior.

While concerns are sometimes raised when classes are retained that include less than 5% of the sample, considerable debate remains within the field as to the how the number of classes should best be selected, and size is only one of many characteristics to be considered (Nylund et al., 2007). A common reason for concern over small class sizes is that these small classes may not actually represent a true separate class, just several outliers from the other classes that happened to look similar. A way to determine whether small classes actually represent a distinct group is to examine posterior probabilities, which show the certainty of class membership for participants in each class. If posterior probabilities for small classes are strong, this suggests that the smaller classes represent distinct groups. Such a decision is further supported when the inclusion of smaller classes improves model fit (i.e., suggesting that the classes represent important variance in the data) and interpretability (i.e., classes show significantly different patterns of associations that would be obscured by collapsing the smaller classes; Collins and Lanza, 2010; Geiser, 2012).

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S, 2010. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 30(2), 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T, 1997. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 21, 613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bagge CL, Tull MT, Joiner TE, 2011. Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. J Psychiatr Res. 45(5), 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. 2011. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 50(8):772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Joiner TE, 2007. Impulsivity and suicidality: A test of the mediating role of painful experiences. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wupperman P, 2012. Emotion regulation and mental health: Recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 25(2), 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wupperman P, Reichardt A, Pejic T, Dippel A, Znoj H, 2008. Emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behav Res Ther. 46(11), 1230–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle GJ, 1991. Does item homogeneity indicate internal consistency or item redundancy in psychometric scales? Personality and Individual Differences. 12(3), 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Burke TA, Stange JP, Hamilton JL, Cohen JN, O’Garro-Moore J, Daryanani I, et al. 2015. Cognitive and emotion-regulatory mediators of the relationship between behavioral approach system sensitivity and nonsuicidal self-injury frequency. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 45(4), 495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti R, Presaghi F, Manca M, Gratz KL, 2012. Deliberate self-harm behavior among Italian young adults: Correlations with clinical and nonclinical dimensions of personality. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 82, 298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ, 2006. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther. 44, 371–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Accessed on June 1, 2018 from: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars

- Cohen J, 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge Academic, New York [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM Lanza ST, 2010. Latent class and latent transition analysis. With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra K, Boduszek D, Klonsky ED, 2016. Empirically derived subgroups of self-injurious thoughts and behavior: Application of latent class analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 46(4), 486–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Paliliunas D, Belisle J, Speelman RC, Gunnarsson KF, Shaffer JL (2018). The effect of brief mindfulness training on momentary impulsivity. J Contextual Behav Sci. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, Williams TJ, 2014. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: Associations with emotion regulation difficulties. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40(2), 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Fischer S, Schnülle J, Bösterling A, Tuschen-Caffier B, 2008. Characteristics of emotion regulation in recovered depressed versus never depressed individuals. Personal Individ Differ. 44(7), 1574–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Emery AA, Heath NL, Mills DJ, 2016. Basic psychological need satisfaction, emotion dysregulation, and non-suicidal self-injury engagement in young adults: An application of self-determination theory. J Youth Adolesc. 45(3), 612–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ, 1994. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 16, 363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR, Rosenthal RJ, 1993. Diagnostic issues in self-mutilation. Psychiatr Serv. 44(2), 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliege H, Kocalevent RD, Walter OB, Beck S, Gratz KL, Gutierrez PM, et al. 2006. Three assessment tools for deliberate self-harm and suicide behavior: Evaluation and psychopathological correlates. J Psychosom Res. 61(1), 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. 2017. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 143(2), 187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Kleiman EM, Bentley KH, Nock MK, 2015. Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clin Psychol Rev. 42, 156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galfalvy H, Hwei T, 2018, October 18 Email and personal interview. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser C, 2012. Data Analysis With Mplus. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Glett GL, Wekerle C, Wall A, 2009. Personality, child maltreatment, and substance use: examining correlates of deliberate self-harm among university students. Can J BehavSci. 41, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, 2001. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 23(4), 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, 2006. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among female college students: the role and interaction of childhood maltreatment, emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity/reactivity. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 76, 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Chapman AL, 2007. The role of emotional responding and childhood maltreatment in the development and maintenance of deliberate self-harm among male undergraduates. Psychol Men Masc. 8(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L, 2002. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1, 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L, 2004. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, 2001. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 69, 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ, 2012. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 80(5), 842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, 2001. Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 77(3), 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Willoughby T, 2013. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A latent class analysis among young adults. PloS One. 8(3), e59955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abela JR, 2011. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 2½ year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 186(1), 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking P, Momeni R, Swannell S, Chia S, 2008. The nature and extent of non-suicidal self-injury in a non-clinical sample of young adults. Arch Suicide Res. 12(3), 208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath N, Toste J, Nedecheva T, Charlebois A, 2008. An examination of nonsuicidal self-injury among college students. J Ment Health Couns. 30(2), 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff ER, Muehlenkamp JJ, 2009. Nonsuicidal self-injury in college students: The role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 39(6), 576–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker E, 2018, October 19 Email interview. [Google Scholar]

- Houston JE, Shevlin M, Adamson G, Murphy J, 2011. A person-centered approach to modelling population experiences of trauma and mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 46, 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CM, Gould M, 2007. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res. 11(2), 129–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins AL, Schmitz MF, 2012. The roles of affect dysregulation and positive affect in nonsuicidal self-injury. Arch Suicide Res. 16(3), 212–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Frank EM, Ciocca M, Barber CW 2011. Training mental healthcare providers to reduce at-risk patients’ access to lethal means of suicide: Evaluation of the CALM Project. Arch Suicide Res. 15, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuentzel JG, Arble E, Boutros N, Chugani D, Barnett D, 2012. Nonsuicidal self-injury in an ethnically diverse college sample. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 82, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Olino TM, 2008. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 76(1), 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, 2007. The functions of deliberate self-injury. A review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 27, 226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler A, Fehling KB, Anestis MD, Selby EA, 2016. Emotional dysregulation, internalizing symptoms, and self-injurious and suicidal behavior: structural equation modeling analysis. Death Stud. 40(6), 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouliere CD, 2013. The role of acquired capability as a differentially specific risk factor for disordered eating and problematic alcohol use in female college students: A measure development and validation study. Dissertation University of South Florida: Tampa, FL: Accessed on June 1, 2018 from: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=5911&context=etd [Google Scholar]

- Labouliere CD, 2009. The spectrum of self-harm in college undergraduates: The intersection of maladaptive coping and emotion dysregulation. Masters thesis University of South Florida: Tampa, FL: Accessed on June 1, 2018 from: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2052/ [Google Scholar]

- Large MM, Ryan CJ, Carter G, Kapur N, 2017. Can we usefully stratify patients according to suicide risk? BMJ. 359, j4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M, 2014. DBT Skills Training Manual. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough JP, Clark SW, Klein DN, First MB, 2016. A procedure to graph the quality of psychosocil functioning affected by symptom severity. Am J Psychother. 70, 222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 1998-2017. Mplus User’s Guide. 8th ed Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Brausch A, Quigley K, Whitlock J, 2013. Interpersonal features and functions of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 43, 43–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Kerr PL, Bradley AR, Larsen MA, 2010. Abuse subtypes and nonsuicidal self-injury: Preliminary evidence of complex emotion regulation patterns. J Nerv Ment Dis. 198(4), 258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, 2009. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 18(2), 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, 2004. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 72(5), 885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, Sterba SK, 2009. Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 118(4), 816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struc Equ Modeling. 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio SC, McCulloch CR, 2004. Alexithymia as a mediator between childhood trauma and self-injurious behaviours. Child Abuse Negl. 28, 339–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passi VA, Bryson SW, Lock J, 2003. Assessment of eating disorders in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Self-report questionnaire versus interview. Int J Eat Disord. 33, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP, 2002. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 26, 272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. 2016. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 46(2), 225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers S, Holtforth MG, Müller M, Hengartner MP, Rössler W, & Ajdacic-Gross V, 2014. Symptom-based subtypes of depression and their psychosocial correlates: A person-centered approach focusing on the influence of sex. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rojahn J, Matson JL, Lott D, Esbensen AJ, Smalls Y, 2001. The Behavior Problems Inventory: An instrument for the assessment of self-injury, stereotyped behavior, and aggression/destruction in individuals with developmental disabilities. J Autism Dev Disord. 31(6), 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, 1993. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Connell LD, Joiner TE, 2010. The pernicious blend of rumination and fearlessness in non-suicidal self-injury. Cognit Ther Res. 34(5), 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Joiner TE Jr, 2009. Cascades of emotion: The emergence of borderline personality disorder from emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Rev Gen Psychol. 13(3), 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slee N, Spinhoven P, Garnefski N, Arensman E, 2008. Emotion regulation as mediator of treatment outcome in therapy for deliberate self-harm. Clin Psychol Psychother. 15(4), 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 44(3), 273–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatnell R, Hasking P, Newman L, Taffe J, Martin G, 2017. Attachment, emotion regulation, childhood abuse and assault: examining predictors of NSSI among adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. 21(4), 610–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PJ, Jomar K, Dhingra K, Forrester R, Shahmalak U, Dickson JM, 2017. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J Affect Disord. 227, 759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Roemer L, 2007. Emotion regulation difficulties associated with the experience of uncued panic attacks: Evidence of experiential avoidance, emotional nonacceptance, and decreased emotional clarity. Behav Ther. 38(4), 378–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE Jr., 2008. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of suicide behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 76, 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U, Chen E, Neighbors C, Hunter D, Lo T, Larimer M, 2007. Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect?. Eat Behav. 8(2), 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, 2001. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal Individ Differ. 30, 669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK, 2005. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Pers. 19(7), 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Eckenrode J, Silverman D, 2006. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics. 117, 1939–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, 2008. Variation in nonsuicidal self-injury: Identification and features of latent classes in a college population of emerging adults. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 37(4), 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Abrams GB, Barreira P, et al. 2013. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 52(4), 486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp JJ, Purington A, Eckenrode J, Barreira J, Baral Abrams G, et al. 2011. Non-suicidal self-injury in a college population: General trends and sex differences. J Am College Health. 59, 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Pinchevsky GM, O’Grady KE, 2012. Longitudinal predictors of past-year non-suicidal self-injury and motives among college students. Psychol Med. 42(04), 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams F, Hasking P, 2010. Emotion regulation, coping and alcohol use as moderators in the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and psychological distress. Prev. Sci. 11(1), 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.