Abstract

Background:

Despite encouraging evidence from pre-clinical studies, clinical trials of d-cycloserine (DCS) augmentation of cue exposure treatment (CET) for substance use disorders have been disappointing. Recent studies underscore the importance of studying DCS under conditions of adequate cue exposure and protection from reconditioning experiences. In this randomized trial, we evaluated the efficacy of DCS for augmenting CET for smoking cessation under these conditions.

Methods:

Sixty-two smokers attained at least 18 hours abstinence following 4 weeks of cognitive-behavioral treatment combined with varenicline or nicotine replacement therapy and were randomly assigned to receive a single dose of DCS (n=30) or placebo (n=32) prior to each of two sessions of CET. Mechanistic outcomes were self-reported cravings and physiologic reactivity to smoking cues. The primary clinical outcome was 6-week, biochemically-verified, continuous tobacco abstinence.

Results:

We found that DCS, relative to placebo, augmentation of CET resulted in lower self-reported craving to smoking pictorial and in vivo cues (d = 0.8 to 1.21) in a relevant subsample of participants who were reactive to cues and free from smoking-related reconditioning experiences. Select craving outcomes were also significantly related to smoking outcomes, and overall, DCS augmentation was associated with a trend toward a higher continuous abstinence rate (33% vs. 13%) compared to those who received placebo and CET.

Conclusions:

DCS augmentation of CET can significantly reduce cue-induced craving, and such reductions in craving are meaningfully related to smoking cessation outcomes, supporting the therapeutic potential of DCS augmentation when applied under appropriate conditions for adequate extinction learning and retention.

Clinical Trial Registry:

NCT01399866; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01399866

Keywords: d-cycloserine, cue exposure, addiction, nicotine dependence, extinction, craving, cue reactivity, smoking cessation

Introduction

D-cycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist at the glycine co-agonist site of the NMDA glutamate receptor, has been shown to augment cue exposure treatment (CET) efficacy for anxiety disorders.[1] By contrast, the human addiction literature on DCS augmentation of CET has been marked by more negative than positive trials,[2] despite encouraging evidence from animal models of addiction.[3] A framework for understanding variable results for DCS addiction trials is offered by recent clarifications of the limits of DCS augmentation for anxiety disorders. In a series of studies, Smits and colleagues found that successful DCS augmentation of exposure was dependent on the degree to which extinction (low fear) was achieved by the conclusion of individual exposure sessions.[4-5] Of concern, an opposite pattern was evident for those with high fear at the end of a CET session, supporting the principle that the degree of benefit offered by DCS will depend on the degree to which effective extinction was achieved during a session in which it is used.

As extended to the addiction literature, this principle underscores the importance of pairing DCS augmentation with only successful CET sessions and that DCS should not be used proximal to re-conditioning (sensitization) experiences. DCS has a half-life of approximately 10 hours;[6] smoking following DCS use thus may lead to augmented reconditioning effects. Indeed, attention to the adequacy of CET sessions for reducing craving and/or the presence of other sensitizing/conditioning experiences can help clarify results within the DCS addiction literature. For example, DCS augmentation studies for addictive behaviors reporting inadequate or inconsistent within-session extinction also reported null effects for DCS relative to placebo.[7-9] Of three studies reporting consistent reductions in cravings across individual trials within the exposure session, two found a benefit of DCS augmentation,[10-11] and one did not.[12] Furthermore, two negative trials of DCS in smokers provide data indicating that participants were smoking around the study sessions, perhaps renewing the association between smoking cues and nicotine reward at times proximal to DCS administration.[7,13]

To address these potential limitations, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigating the effects of a single dose of DCS prior to each of two CET sessions for maintenance of tobacco abstinence. We ensured the relevance of cues used for exposure and craving assessments,[9] provided exposure for a range of visual, in vivo, and interoceptive cues for smoking,[7] and repeated relevant cue exposure trials within a session until responsivity was diminished. To minimize reconditioning proximal to DCS administration, we applied DCS augmentation in a relapse-prevention stage of treatment. To enhance external validity, we provided open-phase treatment utilizing each patient’s choice of one of the two most popular pharmacologic cessation strategies[14] combined with group behavioral treatment. We hypothesized that we would observe a greater benefit for 50mg DCS relative to placebo augmentation of CET for decreasing cue-induced craving during early abstinence, and that this effect on cue reactivity would be reflected in reduced physiologic reactivity to smoking-related cues and improved continuous abstinence outcomes.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee, written informed consent was obtained, and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT01399866). Participant recruitment and study procedures were completed between May, 2011, and April, 2013. The setting for all procedures was a hospital-based outpatient clinic specializing in smoking treatment. A Data and Safety Monitoring Board met quarterly to oversee the conduct of the trial.

Participants

Participants were men and women, aged 18-65 who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day for the prior 6 months, had an expired carbon monoxide (CO) ≥ 10 ppm, expressed a desire to quit smoking, and who provided informed consent. Baseline reactivity to in vivo smoking cues was required for study participation. Exclusion criteria included current unstable medical illness, pregnancy, breastfeeding, or use of isoniazid or ethionamide; major depressive episode or substance use disorder other than nicotine or caffeine active in the prior 6 months; or a lifetime history of any other Axis I psychiatric illness.

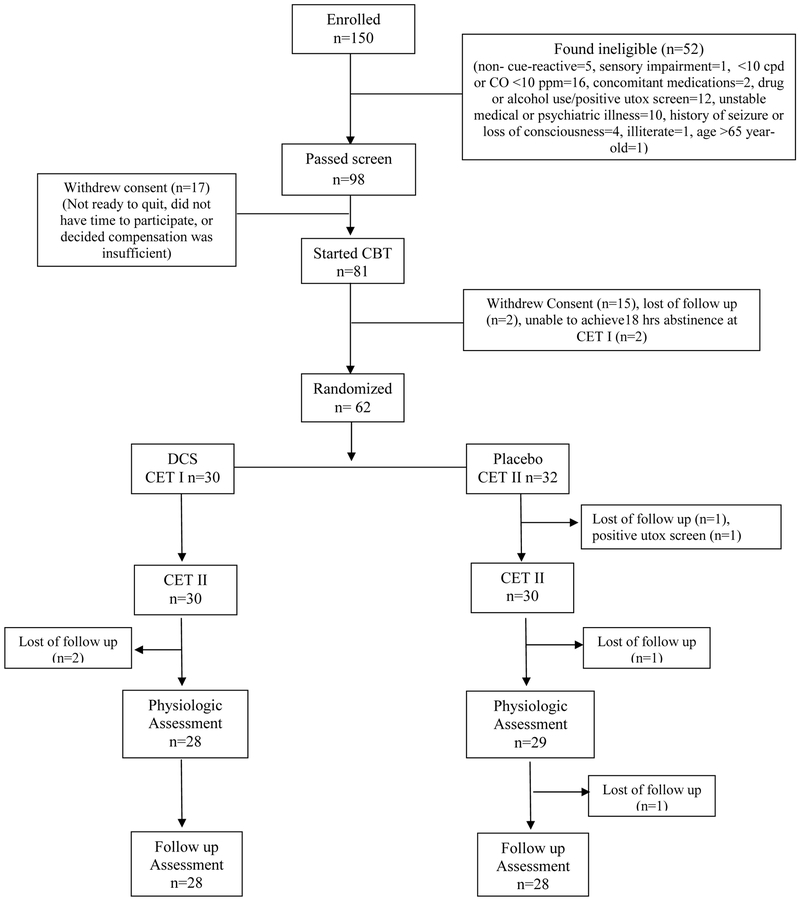

Ninety-eight met inclusion criteria and were offered study treatment, 81 initiated open pharmacologic and behavioral smoking-cessation treatment and 62 attained abstinence during open-label treatment and were randomly assigned to receive a single dose of 50mg DCS (n=30) or placebo (n=32) prior to each of two sessions of CET, one week apart.

Assessments

Baseline assessments included expired CO (MicroSmokerlyzer, Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Kent, UK), smoking and medical history, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),[15] Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale (WSWS),[16] and a VAS (Likert scale of 0-10) for craving, and urine pregnancy screen, semi-quantitative urine cotinine (Accutest NicAlert Urine Screen, Jant Pharmaceuticals) and drug screen. Urine pregnancy and drug screens were repeated prior to study drug administration. Cotinine was repeated prior to the physiologic cue reactivity visit and the 6-week follow-up. Self-report of smoking behavior, concomitant medications, expired CO, and adverse events were collected at every visit.

Procedures

Participants received their choice of transdermal nicotine patch (NRT) or varenicline (0.5 mg per day for 3 days, 0.5 mg bid for 4 days, 1 mg bid for 4 weeks) and weekly individual cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for smoking cessation. After 4 weeks of CBT and pharmacotherapy, participants who demonstrated 18 hours of abstinence were randomized to receive two single doses of DCS (50 mg) or identical placebo, in double-blind fashion, one week apart, prior to CET sessions (see Figure 2). Participants were randomly assigned in blocks of four participants (according to the open-label pharmacotherapeutic cessation aid they received) using a computerized randomization schedule generated by the Research Pharmacy. No member of the study team involved in subject enrollment or with subject contact had access to the random allocation sequence.

Figure 2.

Study Design Schema

Cue-Exposure Therapy (CET).

Two CET sessions were conducted to expose participants to the emotional states, somatic sensations, and situational cues for tobacco use and craving in an extinction paradigm and to rehearse one or more non-smoking responses to smoking cues. Participants received a single observed dose of study medication, waited 50 minutes and began the 90-minute CET. The CET had three components: exposure to slides of smoking (visual) exposure to emotions and imagined situations that most reliably triggered an urge to smoke (emotional/imaginal), and exposure to a participant’s own cigarettes and pack (in vivo).[17] The maximum cue-elicited craving was recorded as the highest scale rating 10-point VAS for craving during exposure to each of the three cue types. The maximum number of exposures was determined by either time limitation (30 minutes) or extinction of craving, defined as ≥50% reduction in self-reported craving. Expired CO was measured one day after each CET session to verify abstinence. NRT or varenicline was discontinued two days after CET-1. Participants who arrived for CET-2 in a non-abstinent state (n = 10) were allowed to proceed, but their outcomes were addressed in specific analyses.

Physiologic Cue Reactivity Assessment:

Cue-elicited craving and physiologic reactivity to smoking-related visual, imaginal, and in vivo cues were assessed two days following the CET-2. Participants were required to report at least 8 hours of tobacco abstinence, have an expired CO <10 ppm, and a negative drug and alcohol screen to participate. Physiologic reactivity was measured with a Coulbourn Modular Instrument System. Skin Conductance (SC) was measured with recording skin electrodes (DocXS™), placed on the non-dominant hypothenar surface with a constant-voltage technique. Heart rate (HR) was recorded using 9-mm diameter Ag/AgCl electrodes filled with electrolytic paste, placed on the medial forearm surface; HR was converted from interbeat interval. Left corrugator EMG was obtained with 4-mm Ag/AgCl electrodes. The amplified EMG signal was integrated using a 200-msec time constant. In brief, visual and in vivo cue presentation were conducted much the same as in the CET sessions. In addition, at baseline, participants prepared detailed descriptions of a routine situation that reliably triggered craving to smoke, as well as a neutral script, resulting in idiographic, 40-second, smoking and neutral scripts; physiologic reactivity was evaluated during presentation of these scripts.[18]

Analysis plan

The primary clinical outcome was 6-week, biochemically verified continuous tobacco abstinence, defined as smoking no cigarettes from 18 hours prior to the CET-1 visit to the 6-week follow-up, verified by self-report, expired CO of < 5 ppm at each visit, and urine cotinine ≤ 30 ng/ml (assessed by semi-qualitative measurement) at the physiologic cue reactivity assessment visit and the 6-week follow-up visit. Abstinence rates were compared with an exact logistic regression. Dropouts were considered to be non-abstinent for the analysis.

Mechanistic outcomes were craving and physiologic reactivity to smoking cues. Detailed analyses of changes in craving across and between CET sessions were provided to allow proof-of-concept evaluation of DCS effects on mechanistic targets under the more precise conditions of adequate CET and an absence of reconditioning events. Specifically, following recommendations by Watson et al. [9], we limited subsequent evaluation of the augmentation of CET learning to those individuals who demonstrated craving to the specific cues targeted in CET. Physiologic outcomes were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA including randomized treatment assignment, cue type (smoking vs. neutral) and abstinence status. For the visual cues, physiological measures were collected during the first five seconds of each slide presentation; the mean for neutral and smoking slides was obtained and compared within subjects. For in vivo and imaginal cues, the mean for each physiologic measure was calculated for each type of cue exposure.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The sample was 66% female, 60% Caucasian, smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes per day, and had moderate severity of nicotine dependence (Mean FTND = 5.6). More than two-thirds of the sample selected NRT as their pharmacotherapeutic cessation aid. The randomized treatment groups did not differ with respect to choice of smoking cessation aid (66% assigned to placebo selected NRT vs. 67% assigned to DCS, ns; see Table 1).

Clinical Abstinence Outcomes

As per Figure 3, DCS augmentation was associated with a 33% (10/30) abstinence rate as compared to a 13% (4/32) rate for placebo augmentation. Abstinence rates were compared with exact logistic regressions in models with and without using cessation pharmacotherapy and its interaction with study drug treatment as independent variables. This difference in abstinence rates reflected a moderate-to-large effect size (d = 0.72) but did not reach significance (exact OR: 3.43, 95% CI: 0.84, 17.18, p=0.096). When adding the choice of cessation pharmacotherapy and its interaction with study drug assignment into the model, the association of treatment assignment and abstinence weakened (exact OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 0.58, 22.42, p=0.238), and neither cessation pharmacotherapy (varenicline vs. NRT exact OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.01, 8.82, p=1.00) or its interaction with DCS treatment (exact OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.02, 82.03, p=1.00) had any association with abstinence at follow-up.

Figure 3.

Continuous abstinence rates at one-month follow-up for each treatment condition.

Within-Session Extinction

In the overall sample of 62 randomized participants, The CET procedures showed themselves to provide an appropriate substrate for the extinction enhancing effects of DCS: in the CET sessions we found both within-session craving activation and within-session extinction. Specifically, 58%,56% and 66% of participants were reactive to visual, in vivo, and imaginal cues, respectively, in CET-1 (with 81% responding strongly to at least one of these cues), and significant reductions in craving were found across all cue exposures within the session (visual: t (59) = 7.88, p < .0001, in vivo: t (58) = 8.04, p < .0001, imaginal: t (59) = 8.88, p < .0001).

Mechanistic Outcomes: Cue-Induced Craving Levels.

We next examined the effect of DCS vs. placebo on the retention of extinction from CET-1 to CET-2, by examining the CET-2 maximal craving score, controlling for the final CET-1 craving rating (see Table 2). To remove the potential effect of reconditioning experiences, we excluded from analysis 2 participants (both in the DCS condition) who had sensitizing experiences as defined by smoking within 24 hours of the CET-1 session. Participants who received DCS had significantly lower maximum craving scores during CET-2 than those who received placebo for visual cue exposure (Beta = −.492, t(28) = −3.20; p = .003, d = 1.21) and in vivo cue exposure (Beta = −.355, t(28) = −2.13; p = .042, d = .80). See Figure 4. Maximal craving scores in response to imaginal cues did not differ by cessation pharmacotherapy (varenicline vs. NRT:Beta = −.153, t(33) = −.91, p = .37, d = .32).

Figure 4.

Advantages of DCS over PBO in terms of effect size (d) for cue-induced cravings at CET-2.

We then evaluated the effect of study drug on cue-induced craving at the physiological assessment visit; across the cue types moderate-to-large effect sizes were observed, reflecting lower craving for the DCS relative to the placebo conditions, but none of these effects reached significance (visual cues: t(22) = −.830, p = .415, d = .35; in vivo cues: t(22) = −1.17, p = .26, d = .50; script-driven imagery: t(27)= −1.73, p = .095, d = .67).

Mechanistic Target Engagement and Clinical Outcomes

For visual cues, lower maximum craving level at CET-2 was associated with an increased likelihood of 7-day point prevalence abstinence at the follow up visit (Wald = 5.41, p = .02, exp(B) = 2.10), such that a 1-point change in maximum craving was associated with 2.1 fold increase in the odds of 7-day point prevalence abstinence at follow-up and with a 2.2 fold increase in the odds of continuous abstinence at follow-up, (Wald = 3.65, p = .06, exp (B) = 2.20). Maximal craving level during the in-vivo and imaginal cue exposure of CET-2 did not predict abstinence at follow up. Only individuals who reported cue elicited craving >2 on VAS at CET-1 were included in the above analyses as per Watson and associates.[9]

Physiological Outcomes

Physiologic reactivity to smoking cues was analyzed for the 29 participants who demonstrated cue reactivity at CET-1: 12 participants who had received DCS and 17 participants who had received placebo. Among the physiologic measures—SC, HR, and EMG—only SC was significantly different between smoking and neutral stimuli, and this occurred only for the script-driven imagery. A main effect reflecting significantly greater reactivity for smoking than non-smoking cues for SC was found for both listening and imagining the scripts (listening: F(1, 57) = 26.75, p < .0001; d = 1.37; imagining: F(1, 57) = 9.41, p < .01, d = 0.81). This main effect for the listening condition was moderated by study drug (interaction: F(1, 57) = 29.96, p < .0001; d = 1.45), with lower smoking-cue reactivity for those who had received DCS. This benefit was enhanced among those who had been continuously abstinent, as indicated by a three-way interaction with continuous abstinence associated with greater DCS benefit (F(1, 57) = 9.84, p < .01, d = 0.83). No other differences between smoking and neutral cues and no other moderation effects by study drug were significant.

Adverse Events

Adverse events reported by 3 or more participants after the first dose of study medication were tabulated and comparisons were made between the frequency of these events in the placebo and DCS conditions; no significant differences were found using separate Fisher’s Exact Tests for each adverse event. There was one hospitalization; this was for a compression fracture sustained by a participant assigned to placebo.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first application of DCS augmentation of cue exposure during a relapse-prevention phase of treatment. In terms of mechanistic target engagement, we found significant and large effect sizes for DCS augmentation of exposure to pictorial and in vivo cues, but not imaginal cues, following the first session of exposure, with evidence of moderate and moderate-to-large effect sizes at the post-extinction assessment. Importantly, we found that reduction in self-reported cue-induced craving (the mechanistic target) was significantly associated with continuous abstinence (the clinical outcome). Furthermore, recently-abstinent smokers who received DCS and CET during a relapse-prevention phase of smoking treatment showed trends reflecting a near-threefold increase in rates of continuous abstinence compared to those who received placebo and CET. Hence, this pilot study provided encouraging support for the use of DCS to augment the efficacy of CET for reducing cigarette-related craving and, correspondingly, to show promise (reflecting moderate-to-large effect sizes) for improving clinical outcomes beyond that offered by CET plus placebo. Efforts to replicate and extend these findings in a larger-scale trial are thus encouraged.

We did not find consistent support for DCS effects on physiologic reactivity to smoking cues. However, interpretations of this finding were complicated by the failure to elicit differential reactivity to smoking vs. neutral cues on physiologic reactivity. The single exception was for script-driven imagery effects on skin conductance; for these cues alone, there was greater reactivity with smoking vs neutral scripts, and notably, reactivity to this cue differed significantly by drug condition. Hence, although physiological reactivity did not consistently correspond with craving outcomes (an issue observed previously)[19] when physiologic cue reactivity was found, a large and significant effect for DCS augmentation was also observed.

A number of limitations in our study design deserve note. First, we designed the study to provide adequate power to detect a large effect size on smoking abstinence outcomes (targeted N = 60). Our targeted power was maintained for our test of clinical outcomes with the intent-to-treat sample. Statistical power was diminished for the proof-of concept analyses of relevant subsamples, and we did not adjust alpha for these multiple small-sample tests of mechanism. Yet, with low power, we obtained significant results for many of the cues examined, and reported promising effect sizes for many of the findings that did not reach significance.

Second, participants in consultation with clinicians chose their cessation pharmacotherapy (varenicline or NRT) during the initial treatment phase. Open choice maximizes external validity, but may have left individuals differentially reactive to smoking cues because of their medication choice. There is preliminary evidence that cue reactivity may be greater with nicotine replacement than varenicline,[20-21] but in independent analyses we were not able to confirm these effects within the current sample. Also, we conducted CET-2 after patients had discontinued these medications, hence exposure augmentation was completed across the changing contexts of medication status, a design feature intended to improve generalization of extinction effects to a medication-free context.[22]

Third, our analytic plan differentially stressed internal and external validity, respectively, for the mechanistic and clinical (smoking cessation) outcomes of the study. This was done to access whether DCS can work under controlled conditions, and whether it did work for the broader sample. Our abstinence outcomes, based on the full sample, suggest that these conditions can be met sufficiently to achieve important clinical outcomes, as reflected by a moderate to large effect size.

Fourth, reactivity to the smoking cues utilized ranged from 56% to 66% of the sample for the visual, in vivo, and imaginal cues used in the protocol. The result is that exposure exercises were not relevant to up to 44% of the sample for any one of these cues, and 19% of the sample showed no reactivity to any of these cues. As such, any strategy to enhance cue relevance/reactivity has the potential to enhance the extinction results reported here and help ensure that these procedures are relevant to a larger sample of smokers. Specifically, smoking cues delivered via virtual reality that can include both social and non-social contexts for smoking[23] may increase the magnitude of cue reactivity as well as the number of individuals showing reactivity to smoking cues. Accordingly immersive virtual reality strategies may provide a more powerful set of cues and contexts for extinction of smoking cues. Combining these strategies with DCS augmentation has the potential to provide stronger results than those reported here.

Overall, our results are more positive than have been generally reported for DCS augmentation of CET for substance dependence. We attribute this finding to our ability to ensure that therapeutic learning occurred during CET and was protected from reconditioning experiences in this relapse prevention trial, following evidence for the importance of these factors from the DCS literature for anxiety disorders.[1] If these considerations are accurate, this would argue for application of DCS only when cue reactivity can be carefully assessed and targeted, and patients can be relatively insulated from drug use following cue exposure and DCS dosing: for example, in residential or inpatient settings or during a relapse-prevention phase of treatment. Further testing of DCS in these contexts is warranted and may significantly enhance the impact of CET on smoking cessation outcomes.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding and Role of the Sponsors

This research was supported by grants R21DA030808 Cognitive Remediation with D-cycloserine to Improve Smoking Cessation Outcomes (Evins), K24030443 Mentoring in addiction treatment research (Evins). Mentoring support was also provided to Gladys N Pachas by the Interdisciplinary Research Training Institute on Hispanic Drug Abuse (NIDA R25DA026401). These funding sources had no other role than financial support.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

In the past, Dr. Otto has served as a paid consultant for MicroTransponder Inc., Concert Pharmaceuticals, ProPhase, received speaker compensation from Big Health, and received royalty compensation for use of the SIGH-A from ProPhase. Dr. Cather has served as a paid consultant for Envivo and ProPhase. Dr. Smits has served as a paid consultant for MicroTransponder Inc. Dr. Evins has received research grant or study supply support from Pfizer and Forum Pharmaceuticals; she has received compensation to her institution for consultation from Pfizer and Reckitt Benckiser. No other authors have financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Otto MW, Kredlow MA, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG, Tolin DF, de Kleine RA, van Minnen A, Evins AE, Pollack MH. Enhancement of psychosocial treatment with D-cycloserine: Models, moderators, and future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;80:274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers KM, Carlezon WA Jr. D-cycloserine effects on extinction of conditioned responses to drug-related cues. Biol. Psychiatry 2012;71:947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nic Dhonnchadha BA, Szalay JJ, Achat-Mendes C, Platt DM, Otto MW, Spealman RD, Kantak KM. D-cycloserine deters reacquisition of cocaine self-administration by augmenting extinction learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smits JAJ, Rosenfiel D, Otto MW, Marques L, Davis ML, Meuret AE, et al. D-cycloserine enhancement of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder depends on the success of exposure sessions. J.Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1455–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smits JAJ, Rosenfield D, Otto MW, Powers MB, Hofmann SG, Telch MJ, et al. D-cycloserine enhancement of fear extinction is specific to successful exposure sessions: Evidence from the treatment of height phobia. Biol Psychiatry 2013;73:1054–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Physicians’ Desk Reference. 2006. Montvale, NJ: Thompson PDR. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamboj SK, Joye A, Das RK, Gibson AJ, Morgan CJ, Curran HV. Cue exposure and response prevention with heavy smokers: a laboratory-based randomised placebo-controlled trial examining the effects of D-cycloserine on cue reactivity and attentional bias. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;221:273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmann SG, Huweler R, MacKillop J, Kantak KM. Effects of D-cycloserine on craving to alcohol cues in problem drinkers: preliminary findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2012;38:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson BJ, Wilson S, Griffin L, Kalk NJ, Taylor LG, Munafo MR, et al. A pilot study of the effectiveness of D-cycloserine during cue-exposure therapy in abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;216:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKillop J, Few LR, Stojek MK, Murphy C, Malutinok SF, Johnson FT, Hofmann SG, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Monti PM. D-cycloserine to enhance extinction of cue-elicited craving for alcohol: a translational approach. Transl Psychiatry 2015;5:e544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santa Ana EJ, Rounsaville BJ, Frankforter TL, Nich C, Babuscio T, Poling J, et al. D-Cycloserine attenuates reactivity to smoking cues in nicotine dependent smokers: a pilot investigation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104,220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamboj SK, Massey-Chase R, Rodney L, Das R, Almahdi B, Curran HV, et al. Changes in cue reactivity and attentional bias following experimental cue exposure and response prevention: a laboratory study of the effects of D-cycloserine in heavy drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;217:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon JH, Newton TF, Haile CN, Bordnick PS, Fintzy RE, Culbertson C, et al. Effects of D-cycloserine on cue-induced craving and cigarette smoking among concurrent cocaine- and nicotine-dependent volunteers. Addict Behav. 201338;1518–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etter J-F, Schneider NG. An Internet Survey of Use, Opinions and Preferences for Smoking Cessation Medications: Nicotine, Varenicline, and Bupropion. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. 1991. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welsch SK, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Development and validation of the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH. Cue-provoked craving and nicotine replacement therapy in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1136–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pachas GN, Gilman J, Orr SP, Hoeppner B, Carlini SV, Loebl T, et al. Single dose propranolol does not affect physiologic or emotional reactivity to smoking cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;232: 1619–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRowe SD, Saladin ME, Carpenter MJ, Upadhyaya HP. Reactivity to nicotine cues over repeated cue reactivity sessions. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2888–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandon TH, Drobes DJ, Unrod M, Heckman BW, Oliver JA, Roetzheim RC, et al. Varenicline effects on craving, cue reactivity, and smoking reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;218:391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiffany ST, Cox LS, Elash CA. Effects of transdermal nicotine patches on abstinence-induced and cue-elicited craving in cigarette smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto MW, McHugh RK, Kantak KM. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Medication effects, clucocorticoids, and attenuated outcomes. Clin Psychology: Sci Pract. 2007;17:91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: Review and analysis. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2005;12:72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pericot-Valderde I, Germeroth LJ, Tiffany ST. The use of virtual reality in the production of cue-specfic craving for cigarettes: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]