Abstract

Trichomoniasis is caused by the parasitic protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis and is the most prevalent, nonviral sexually transmitted disease. The parasite has shown increasing resistance to the current 5-nitroimidazole therapies indicating the need for new therapies with different mechanisms. T. vaginalis is an obligate parasite that scavenges nucleosides from host cells and then uses salvage pathway enzymes to obtain the nucleobases. The adenosine/guanosine preferring nucleoside ribohydrolase was screened against a 2000-compound diversity fragment library using a 1H NMR-based activity assay. Three classes of inhibitors with more than five representatives were identified: bis-aryl phenols, amino bicyclic pyrimidines, and aryl acetamides. Among the active fragments were 10 compounds with ligand efficiency values greater than 0.5, including five with IC50 values <10 μM. Jump-dilution and detergent counter screens validated reversible, target-specific activity. The data reveals an emerging SAR that is guiding our medicinal chemistry efforts aimed at discovering compounds with nanomolar potency.

Keywords: antitrichomonal therapeutics, fragment screening, nucleoside ribohydrolase, Trichomonas vaginalis

Graphical Abstract

Trichomonas vaginalis, a parasitic protozoan, is the causative agent of trichomoniasis, which is currently considered the most widespread nonviral sexually transmitted disease in the world.1 According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 276.4 million new cases of trichomoniasis are reported every year, with higher prevalence and incidence in resource-limited settings such as African regions or the Americas.2 Although this disease can affect all genders, a significantly higher percentage of cases are diagnosed in women due to a more severe and evident symptoms’ presentation. Accumulating research has demonstrated that the chief concern about T. vaginalis infections is their predisposing nature for significantly more severe diseases and sequelae2, 3 Trichomoniasis is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm delivery and low birth weights, as well as higher risk of HPV infection that could lead to cervical cancer.2,3 It has also been shown to increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. The correlation between T. vaginalis infections and HIV acquisition remains the most alarming, with up to a 3-fold increased contraction risk in T. vaginalis carriers.4

T. vaginalis is a free-swimming, flagellated trophozoite. It is a predatory obligate parasite that uses carbohydrates as its main energy source through fermentative metabolism in its hydrogenosome.3 T. vaginalis causes trichomoniasis through an infection in the urogenital tract in men and women. In women, the parasite binds to the vaginal epithelial cells, mediated by lipophosphoglycans and surface proteins, and differentiates from its typical pyriform shape to an amoeboid shape in order to increase surface contact with the host cells.1 After this binding occurs, parasitic proteins can be delivered to the host cell using exosomes and the organism can replicate through binary fission.3

The current drugs used as treatment for this disease belong to a class of 5-nitroimidazoles, specifically the compounds metronidazole and tinidazole. Metronidazole enters the hydrogenosome by passive diffusion where it is subsequently activated.5 The drug can then interfere with the metabolic processes and enzymes including pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase, nitroreductase, and thioredoxin reductase.5 However, this treatment was developed over five decades ago, and its efficacy has decreased as some strains of the parasite develop resistance. While the prevalence of resistance is only about 5% in the United States, it has been reported to be as high as 17% in other countries.5 A reliance on a single drug class since 1960, as well as the relatively nonspecific mechanism of these drugs, has caused resistance to the 5-nitroimidazoles to develop. Reduction in drug susceptibility necessitates the development of a novel treatment with a distinct mechanism of action.

One such mechanism could involve the inhibition of key salvage pathway enzymes on which T. vaginalis relies. These enzymes are known as nucleoside hydrolases (NHs), and they are responsible for the cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond of ribonucleosides in order to produce a free nucleic base and a ribose.6 Parasitic protozoans such as T. vaginalis rely on these enzymes because they are unable to synthesize purine and pyrimidine rings de novo.6 Therefore, the inhibition of these enzymes could be used as a novel treatment of this disease.

The T. vaginalis genome7 contains three confirmed NHs: adenosine/guanosine nucleoside hydrolase (AGNH, TVAG_213720),8 guanosine/adenosine/cytidine nucleoside hydrolase (GACNH, TVAG_305790),9 and uridine nucleoside hydrolase (UNH, TVAG_092730).10 AGNH efficiently hydrolyzes adenosine and guanosine but has barely detectable activity toward cytidine or uridine. GACNH has broad activity toward guanosine, adenosine, and cytidine but does not hydrolyze uridine. UNH is highly specific for uridine, with only marginal activity toward cytidine and no measurable activity for the other nucleosides. We have previously demonstrated the druggability of all three confirmed NHs by developing NMR-based activity assays to screen the National Institutes of Health Clinical Compound Collection for inhibitors. In the case of AGNH, flavonoids were identified as micromolar inhibitors.8

However, one limitation of the flavonoid inhibitors identified from this collection of known drugs is their low ligand efficiency (LE) values11,12 given their large heavy atom counts (HAC). The flavonoid (+)−taxifolin shown in Figure 1 has a LE of 0.34, but its molar mass of 304 g/mol (heavy atom count of 22) combined with only modest micromolar activity makes it a less than ideal chemical starting point for drug design. It is unlikely to be optimized into a drug with nanomolar activity and molar mass below 500 g/mol.13 However, testing just a dozen flavonoid fragments identified the 7-hydroxyquinoline scaffold in Figure 1 with a molar mass of just 145 g/mol (heavy atom count of 11). This fragment has a markedly better LE of 0.58 and could serve as the basis for medicinal chemistry efforts.14,15 The 7-hydroxyquinoline scaffold was found to retain substantial activity against AGNH compared to the parent flavonoids and may thus provide an interesting scaffold for chemical elaboration. A second limitation of the NIH Clinical Collection is a lack of chemical diversity. While we were able to identify a scaffold with an excellent LE value from just a dozen on-hand or easily obtained compounds, our choice of compounds was directed by a very limited sampling of chemical space. The easy identification of small compounds with LE values >0.5 provides proof-of-concept for a broader fragment-based drug discovery project path. A fragment diversity library encompasses a much broader chemical space than is contained within the NIH Clinical Collection and will very likely contain novel scaffolds that have higher LE values, are more amenable to chemical elaboration, or are otherwise more ideal.

Figure 1.

Structures, IC50 values, and LE values for (+)−taxifolin (left) and 7-hydroxyquinoline (right).

A collection of 1963 fragments, comprising a diversity-based subset of the AstraZeneca fragment library, were tested in the initial screen. The compounds were supplied as 100 mM stock solutions in 1H-DMSO and had an average molar mass of 195 g/mol and heavy atom count of 14. Fragments were first screened in mixtures of six, with mixtures displaying inhibition subsequently deconvoluted by testing the mixture components individually.

AGNH-catalyzed hydrolysis of adenosine to produce adenine and ribose can be monitored by 1H NMR.8 Reaction progress is most easily observed and quantified by the disappearance of an adenosine singlet resonance at 8.48 ppm and the appearance of an adenine singlet resonance at 8.33 ppm as shown in the 40 min control spectrum in Figure 2. The adenosine doublet resonance at 6.09 ppm can also serve as an indicator of reaction progress. A situation where all three resonances are simultaneously obscured by resonances from test compounds has yet to be encountered, making this method very robust for fragment screening. The presence of the 1H-DMSO signal also does not interfere with reaction monitoring.8

Figure 2.

Regions of the 1H NMR reaction spectra for six mixtures (Mix 1 to Mix 6) along with 0 and 40 min control spectra. The 0 min control spectrum contains substrate resonances at 6.09, 8.38, and 8.48 ppm. The 40 min control spectrum contains a new product resonance at 8.33 ppm. Each mixture spectra contains additional, different resonances arising from its six unique components.

The utility of this method for fragment screening is demonstrated in Figure 2, which shows the reaction spectra for six mixtures of six compounds each, along with 0 and 40 min control spectra. None of the resonances for the 36 fragments overlap with the substrate resonance at 6.09 ppm or the product resonance at 8.33 ppm. This product signal is observed in the reaction spectra for each mixture except for mixture 5 (marked by the arrow), indicating that at least one of the fragments in mixture 5 is a strong AGNH inhibitor. Diminished intensity of the product signal in mixture 4 suggests that at least one of the fragments in mixture 4 is a weak AGNH inhibitor. However, only mixture reaction spectra indicative of >90% inhibition were deconvoluted to identify the responsible fragment(s).

The deconvolution reaction spectra for mixture 5 are shown in Figure 3. The product signal is observed for all fragments with the exception of fragment D4 (marked by the arrow) which fully inhibits the reaction. Fragment F4 is also observed to partially inhibit the reaction with 53% inhibition at 333 μM concentration used. Fragments that demonstrated at least 90% inhibition were then assayed in a dose-dependent fashion from 333 to 1.3 μM to determine their IC50 values. A representative sample of the active fragments, including some from each chemical series identified, were also obtained as solids and assayed from 1.33 mM to 0.33 μM. Fragment D4 (subsequently referred to as fragment 9) was one of these compounds to be retested, and its dose-dependent reaction spectra are shown in Figure 4. Here, the 1H NMR spectra provide two pieces of information. First, the change in intensity of the substrate or product signals can be quantified as a function of fragment concentration and used to determine the fragment’s IC50 value. Second, the sharp 1H resonances observed for the fragment at 1.33 mM, as well as the very minimal concentration-dependent changes in chemical shift, suggest that it is highly water-soluble and not aggregating in solution.16 These spectra are also indicators of fragment identity and purity.

Figure 3.

Regions of the 1H NMR reaction spectra for the six components of mixture 5 (A4–F4) along with 0 and 40 min control spectra. Each component spectra contains additional, different resonances arising from its unique structure.

Figure 4.

Regions of the 1H NMR reaction spectra for variable concentrations of fragment 9. Seven concentrations (1.33 mM to 0.33 μM) along with 0 and 40 min control spectra are shown. Resonances from 7.2 to 7.7 ppm arise from fragment 9 and vary in intensity commensurate with its concentration.

A total of 78 fragments (4% hit rate) exhibited some inhibition against the enzyme. Five of those fragments had IC50 values less than 10 μM. More importantly, 36 of the fragments were clustered into 9 classes based on structure. The three most common structural classes were termed bis-aryl phenols, amino bicyclic pyrimidines, and aryl acetamides. Table 1 shows the structures, IC50 values, and LE values for the 10 fragments that have LE values greater than 0.5.

Table 1.

Fragment Structures, IC50 Values, and LE Values

| Fragment | Structure | IC50 (μM)a |

LE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

5.2 | 0.56 |

| 2 |  |

6.8 | 0.55 |

| 3 |  |

25 | 0.53 |

| 4 |  |

46 | 0.54 |

| 5 |  |

6.5 | 0.59 |

| 6 |  |

1.9 | 0.65 |

| 7 |  |

25 | 0.57 |

| 8 |  |

40 | 0.51 |

| 9 |  |

3.6 | 0.73 |

| 10 |  |

19 | 0.50 |

Values are the average of n = 2.

All of these fragments were among those that were obtained as solids for activity validation and will provide excellent starting points for medicinal chemistry efforts.

These initial hits were then used to select 166 fragment analogs from the AstraZeneca compound collection for further testing against the enzyme. A number of fragment analogs were discovered with improved activity compared to the parent fragment, including several with 5- to 10-fold improvements in potency. Just as importantly, a significant number of the fragment analogs had diminished activity compared to the parent fragment, suggesting synthetic modifications to avoid.

In order to validate the activity of fragment hits against AGNH and rule out artifactual assay activity,17 counter screens were carried out on 17 compounds selected to be representative of the structural classes of active compounds. The 1H NMR-based activity assay for AGNH proved remarkably robust for the two types of counter screens carried out: jump-dilution assays and detergent assays. Jump-dilution assays are a counter screen for irreversible inhibition.18 Figure 5 shows the jump-dilution assays carried out on fragment 7 which has an IC50 value of 24.9 μM. Incubation with AGNH for 30 min at 200 μM compound followed by running the reaction at 200 μM results in nearly complete inhibition, as expected at an inhibitor concentration about eight times the IC50. However, incubation with AGNH for 30 min at 200 μM compound followed by rapid dilution and running the reaction at 20 μM results in only about 50% inhibition, as expected at an inhibitor concentration near the IC50. Fragment 7 is thus clearly behaving as a reversible inhibitor. Detergent assays are a counter screen for colloidal aggregation.19 If the intrinsic activity of a compound is derived from the formation of colloidal aggregates that adsorb and denature the target enzyme, its activity will be diminished in the presence of detergent. Figure 6 shows the reaction assays for 100 μM fragment 7 in the presence and absence of 0.01% Triton X-100. There is no marked attenuation of inhibition in the presence of detergent, thus indicating that fragment 7 is not functioning as an aggregation-based inhibitor. The 1H NMR spectra collected for the dose–response curves also provide early evidence for lack of aggregation based on sharp resonance line widths at higher concentrations. However, the detergent assay counter screen is more definitive since sharp resonance line widths can also result from exchange between monomers and aggregates as has been demonstrated for a flavonoid similar to (+)−taxifolin.20 As observed in Figure 6, the fragment 7 resonance line widths are also unaffected by detergent.

Figure 5.

Regions of the 1H NMR reaction spectra for fragment 7 jump-dilution counter screen. (A) 200 μM incubation and 200 μM reaction, (B) control for 200 μM incubation and 200 μM reaction, (C) 200 μM incubation and 20 μM reaction, and (D) control for 200 μM incubation and 20 μM reaction. Resonances from 7.3 to 7.5 ppm arise from fragment 7.

Figure 6.

Regions of the 1H NMR reaction spectra for fragment 7 detergent counter screen. (A) 100 μM reaction without detergent, (B) control without detergent, (C) 100 μM reaction with 0.01% Triton X-100, (D) control with 0.01% Triton X-100. Resonances from 7.3 to 7.5 ppm arise from fragment 7. Resonances at 6.90 and 7.38 ppm arise from Triton X-100.

Jump-dilution and detergent assay data for 17 additional compounds are provided as Supporting Information. None of the compounds tested positive in either assay. The 10 compounds shown in Table 1 were also screened for PAINS chemotypes21 using ZINC.22 None were identified. Chemo-type promiscuity was also analyzed using Badapple.23 While the majority of the compounds were clean, high scores were noted for the benzimidazole, quinazoline, and thiazole chemotypes present in several of the fragments. Dose–response curve shapes and already-emerging SAR provide further indication that the fragments described here are well-behaved, target-specific inhibitors.

Deconstruction of larger molecular weight inhibitors to identify fragment inhibitors with higher LE values suggested that a fragment library diversity screen against AGNH would be successful. The data presented here clearly support this outcome. The fact that compound classes were identified with as many as seven compounds strongly indicates that the activity of the fragments is target-specific. The fragment library screened was specifically designed to provide chemical diversity and maximal sampling of unique chemical scaffolds. The most common structural classes identified in the screen were not over-represented in the collection with bis-aryl phenols comprising only 0.7% of the overall fragment collection, amino bicyclic pyrimidines comprising 0.5% of the overall fragment collection, and aryl acetamides comprising 1.1% of the overall fragment screen. This suggests that these features are being preferentially selected in the screen given their small prevalence in the overall collection. Interestingly, three quinoline fragments were among the 78 active fragments, thus rediscovering this fragment scaffold from the earlier hit deconstruction. Since the fragment library was designed to contain compounds with appropriate physicochemical properties and lacking any PAINS chemotypes, as well as diversity, the rich output provides several excellent starting points to progress from fragment to lead template.

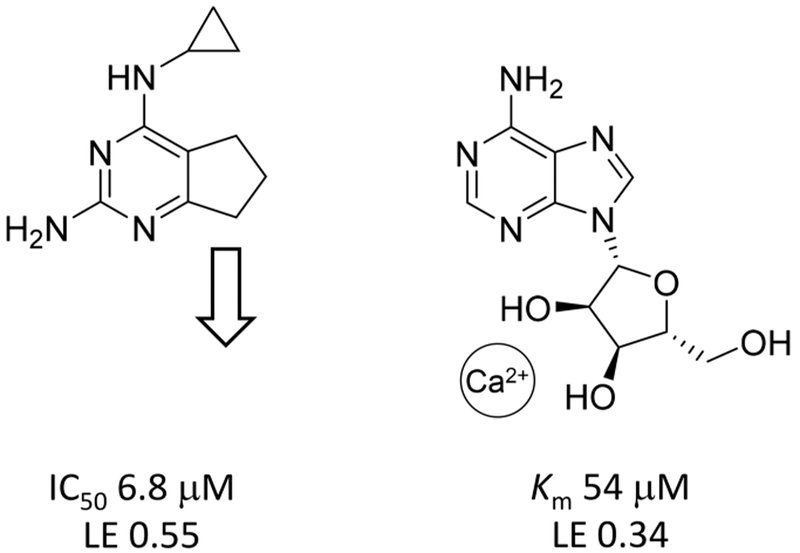

The original fragment hits along with the follow up compound data reveal an emerging SAR that will guide the beginning of our medicinal chemistry efforts. One common theme is the need to pick up interactions with the Ca2+ cation in the active site.6 The majority of fragments have structures that appear to mimic that of the nucleobase and thus likely interact in the nucleobase portion of the active site. However, as illustrated for the amino bicyclic pyrimidine fragment 2 in Figure 7, none of the fragment classes likely make interactions that mimic those of the substrate’s ribose moiety. Thus, extensions from vectors directed toward the Ca2+ site will be explored in order to delineate the optimal placement of Ca2+-chelating functional groups. The presence of the cyclopropyl group in fragment 2 suggests an exploration of hydrophobic interactions on this face of the fragments. This is also supported by the identification of 2-chloro-N(6)-cyclopenty-ladenosine as a 9 μM inhibitor in our previous work.8 Analogs of fragment 2 shown in Table 2 also provide initial SAR, including the impact of polar functional groups delineated by compounds 12–14. Molecular modeling and X-ray crystallography are being pursued to support structure-guided inhibitor design.

Figure 7.

Structures, IC50 or Km values, and LE values for fragment 2 (left) and adenosine (right).

Table 2.

Analogs of Fragment 2

| Compound | structure | IC50(μM)a |

|---|---|---|

| 2 |  |

6.8 |

| 11 |  |

52 |

| 12 |  |

16 |

| 13 |  |

229 |

| 14 |  |

358 |

| 15 |  |

Inactive |

Values are the average of n = 2.

Fragment scaffolds will be developed into chemical tools for in vitro proof-of-concept target validation. A requirement to link enzyme inhibition with antitrichomonal activity is to demonstrate a correlation between enzyme inhibition IC50 values and antitrichomonal IC50 values. There are currently no available tool compounds to carry out these studies for AGNH. At a minimum, this will require at least several compounds with enzyme inhibition <1 μM. A series of chemically related compounds that spans IC50 values from 0.1 to 10 μM would provide more rigorous target validation. This process is also likely to generate lead or lead-like compounds that possess the combination of enzyme inhibition, antitrichomonal activity, and drug-like properties that would form the basis of a focused drug discovery program.

Finally, the utility of the NMR methods used for the two types of counter screens deserves mention. It is well-documented that NMR-based activity assays provide added value when NMR is the method used for fragment screening.24 In contrast to an NMR-based binding assay that only identifies fragments that bind to a target, NMR-based activity assays identify fragments that inhibit a target. The activity assays also use far less target enzyme than do binding assays. Using the NMR-based activity assay for the jump-dilution and detergent counter screens not only answers the original question posed by the counter screen but also provides the added value associated with observing the NMR signals for the compounds being tested. The use of the counter screen methods described here should be considered for other enzymes even if spectrophotometric or other methods are available for the primary screening assay.

METHODS

NMR data sets were collected on a Bruker AvanceIII 500 MHz spectrometer equipped with a BBFO probe and a SampleX-press. The acquisition and relaxation delay times of 2.045 and 1.0 s, respectively, resulted in a total acquisition time of 13 min per spectrum with 256 scans.

Fragment library plates were thawed and rocked gently for 2 h prior to screening.Then, 12 μL of 5 mM adenosine and 2 μL of each fragment to be tested were added to microfuge tubes. Reactions were initiated by adding a stock solution consisting of 50 mM potassium phosphate and 0.3 M KCl at pH 6.5, 10% 2H2O, and 50 nM AGNH to give a final volume of 600 μL. Reactions were quenched after 40 min by the addition of 10 μL of 1.5 M HCl. The final concentrations of adenosine and each fragment were 100 and 333 μM, respectively. The ratio of [substrate]/Km of ~2 creates optimal balanced assay conditions for detecting competitive, noncompetitive, and uncompetitive inhibitors.24 Control reactions were also run by quenching at 0 and 40 min in the absence of fragments. Once an inhibitor was identified, a five-point serial dilution assay was performed from 333 to 1.3 μM in duplicate. The percent conversion of substrate was determined for each concentration by comparing the intensity of the substrate peak to that of the 0 min control. Percent inhibition was then determined by comparison to the percent conversion of the 40 min control sample. GraphPad Prism was used to calculate the IC50 value based on the percent inhibition as a function of the compound concentration. A total of 21 compounds were also obtained as solids and retested in duplicate seven-point serial dilution assays from 1.33 mM to 0.33 μM in order to validate their inhibition and determine dose response activity (IC50 values). Fragment analogs were obtained as 10 mM solutions in 1H-DMSO and tested in duplicate six-point serial dilution assays from 200 to 0.2 μM in order to characterize their inhibition and, where appropriate, determine their IC50 values.

Jump-dilution assays were carried out by incubating AGNH with a given fragment at 200 μM for 30 min prior to initiating the reaction assay. Two samples (and two controls) were run in parallel for each fragment. For one sample, the incubation solution containing 200 μM fragment was used without any dilution after the 30 min incubation period to initiate the 40 min reaction. For the other sample, the incubation solution was diluted to 20 μM fragment immediately after the 30 min incubation period and before the 40 min reaction was initiated. The percent inhibition was then compared to corresponding control samples in the absence of fragment. The 200 and 20 μM concentrations were chosen since most of the 17 compounds have IC50 values of around 20 μM. For the detergent assays, fragments were tested at concentrations of 100 and 50 μM in the presence and absence of 0.01% v/v Triton X-100 nonionic detergent. Reactions on a given fragment were run in parallel using separate buffer stock solutions (with and without detergent) and compared to corresponding control reactions. Solutions with detergent were prepared fresh each day.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AI128585 to B.J.S. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Research was also supported by a Horace G. McDonell Summer Research Fellowship awarded to S.N.M., a Landesberg Family Fellowship awarded to J.A.G., and Faculty Development Grants and the Frederick Bettelheim Research Award from Adelphi University to B.J.S.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00346.

Properties of the fragment screening library along with jump-dilution and detergent counter screen assay data for 17 compounds representative of the chemical structure classes (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hirt RP, and Sherrard J (2015) Trichomonas vaginalis origins, molecular pathobiology and clinical considerations. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 28, 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bouchemal K, Bories C, and Loiseau PM (2017) Strategies for prevention and treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 811–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kissinger P (2015) Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. BMC Infect. Dis. 15, 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Leitsch D (2016) Recent advances in the Trichomonas vaginalis field. F1000Research 5, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Conrad MD, Bradic M, Warring SD, Gorman AW, and Carlton JM (2013) Getting trichy: Tools and approaches to interrogating Trichomonas vaginalis in a post-genome world. Trends Parasitol. 29, 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Versees W, and Steyaert J (2003) Catalysis by nucleoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Carlton JM, Hirt RP, Silva JC, Delcher AL, Schatz M, Zhao Q, Wortman JR, Bidwell SL, Alsmark UCM, Besteiro S, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Noel CJ, Dacks JB, Foster PG, Simillion C, Van de Peer Y, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Westrop GD, Muller S, Dessi D, Fiori PL, Ren Q, Paulsen I, Zhang H, Bastida-Corcuera FD, Simoes-Barbosa A, Brown MT, Hayes RD, Mukherjee M, Okumura CY, Schneider R, Smith AJ, Vanacova S, Villalvazo M, Haas BJ, Pertea M, Feldblyum TV, Utterback TR, Shu C-L, Osoegawa K, de Jong PJ, Hrdy I, Horvathova L, Zubacova Z, Dolezal P, Malik S-B, Logsdon JM Jr., Henze K, Gupta A, Wang CC, Dunne RL, Upcroft JA, Upcroft P, White O, Salzberg SL, Tang P, Chiu C-H, Lee YS, Embley TM, Coombs GH, Mottram JC, Tachezy J, Fraser-Liggett CM, and Johnson PJ (2007) Draft genome sequence of the sexually transmitted pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. Science 315, 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Beck S, Muellers SN, Benzie AL, Parkin DW, and Stockman BJ (2015) Adenosine/guanosine preferring nucleoside ribohydrolase is a distinct, druggable antitrichomonal target. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 5036–5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Alam R, Barbarovich AT, Caravan W, Ismail M, Barskaya A, Parkin DW, and Stockman BJ (2018) Druggability of the guanosine/adenosine/cytidine nucleoside hydrolase from Trichomonas vaginalis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 92, 1736–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Shea TA, Burburan PJ, Matubia VN, Ramcharan SS, Rosario I Jr., Parkin DW, and Stockman BJ (2014) Identification of proton-pump inhibitor drugs that inhibit Trichomonas vaginalis uridine nucleoside ribohydrolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hopkins AL, Groom CR, and Alex A (2004) Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today 9, 430–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Abad-Zapatero C (2007) Ligand efficiency indices for effective drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2, 469–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hajduk PJ (2006) Fragment-based drug design: How big is too big? J. Med. Chem. 49, 6972–6976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dhiman R, Sharma S, Singh G, Nepali K, and Singh Bedi PM (2013) Design and synthesis of aza-flavones as a new class of xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. 346, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Valdez-Padilla D, Rodríguez-Morales S, Hernández-Campos A, Hernández-Luis F, Yépez-Mulia L, Tapia-Contreras A, and Castillo R (2009) Synthesis and antiprotozoal activity of novel 1-methylbenzimidazole derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 1724–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).LaPlante SR, Carson R, Gillard J, Aubry N, Coulombe R, Bordeleau S, Bonneau P, Little M, O’Meara J, and Beaulieu PL (2013) Compound aggregation in drug discovery: Implementing a practical NMR assay for medicinal chemists. J. Med. Chem. 56, 5142–5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Aldrich C, Bertozzi C, Georg GI, Kiessling L, Lindsley C, Liotta D, Merz KM, Schepartz A, and Wang S (2017) The ecstasy and agony of assay interference compounds. ACS Cent. Sci 3, 143–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Copeland RA, Basavapathruni A, Moyer M, and Scott MP (2011) Impact of enzyme concentration and residence time on apparent activity recovery in jump dilution analysis. Anal. Biochem. 416, 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Feng BY, and Shoichet BK (2006) A detergent-based assay for the detection of promiscuous inhibitors. Nat. Protoc. 1, 550–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Dalvit C, Caronni D, Mongelli N, Veronesi M, and Vulpetti A (2006) NMR-based quality control approach for the identification of false positives and false negatives in high throughput screening. Curr. Drug Discovery Technol. 3, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Baell JB, and Holloway GA (2010) New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2719–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sterling T, and Irwin JJ (2015) ZINC 15 – ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 55, 2324–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yang JJ, Ursu O, Lipinski CA, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, and Bologa CG (2016) Badapple: promiscuity patterns from noisy evidence. J. Cheminf. 8, 29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dalvit C (2007) Ligand- and substrate-based 19F NMR screening: Principles and applications to drug discovery. Prog. Nucl Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 51, 243–271. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.