Structured Abstract:

Objective.

Individual dermatomyositis-associated autoantibodies are associated with distinct clinical phenotypes. This study was undertaken to explore the association of these autoantibodies with specific muscle biopsy features.

Methods.

Dermatomyositis subjects with a muscle biopsy reviewed at Johns Hopkins had sera screened for autoantibodies recognizing Mi-2, TIF1γ, NXP2, MDA5, Ro52, PM-Scl, and Jo-1. We also included anti-Jo-1 positive polymyositis patients who had a biopsy read at Johns Hopkins. Analyzed histological features included perifascicular atrophy, perivascular inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, primary inflammation, and myofiber necrosis. Duration of disease, biopsy location, and treatment at biopsy were also analyzed.

Results.

91 dermatomyositis and 7 anti-Jo-1 positive polymyositis patients were studied. In univariate analyses, Tif1γ+ patients had more mitochondrial dysfunction (47% vs 18%; p=0.05), NXP2+ patients had less primary inflammation (0% vs 28%; p=0.01), Mi-2+ patients had more primary inflammation (50% vs 19%; p=0.03), and PM-Scl+ patients had more primary inflammation (67% vs 18%; p=0.004) than those who were negative for each autoantibody. Although reliability was limited due to small sample numbers, multivariate analysis confirmed that Tif1γ+ patients had more mitochondrial dysfunction (PR 2.6, 95%CI 1.0–6.1, p=0.05) and PM-Scl+ patients had more primary inflammation (PR 5.2, 95%CI 2.0–13.4; p=0.001) independent of disease duration at biopsy, biopsy site, and treatment at biopsy. No differences in muscle biopsy features were noted between anti-Jo-1 positive patients diagnosed with dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

Conclusion.

The prevalence of different histological features varies according to autoantibody status in dermatomyositis. Muscle biopsy features are similar in anti- Jo-1 patients with and without a rash.

Key Indexing Terms: Myositis, Polymyositis, Dermatomyositis, Autoimmunity, Muscle

Introduction

Dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM) are acquired autoimmune myopathies characterized by symmetric proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, and inflammatory infiltrates on muscle biopsy (1). The classic diagnostic criteria of Bohan and Peter (B&P) distinguished DM from PM based exclusively on the presence or absence of characteristic DM rashes (1). However, in the nearly 40 years since these criteria were published, muscle biopsy features characteristic of both DM and PM have been described. According to more modern classification systems, the pathognomonic histologic feature of DM is perifascicular atrophy, while PM is characterized by lymphocytes surrounding and invading non-necrotic muscle fibers (i.e, primary inflammation) (2–5). Interestingly, histological evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction has been reported as a characteristic feature in some patients with DM (6). In addition, it is now recognized that some patients with autoimmune myopathy have a predominantly necrotizing myopathy with minimal inflammatory cell infiltrates and no perifascicular atrophy. These patients are now categorized histologically as having immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) or necrotizing autoimmune myopathy (NAM) rather than DM or PM (2, 7).

Another major advance in our understanding of the autoimmune myopathies is the recognition that distinct autoantibodies are associated with unique clinical phenotypes. Examples include the following: (a) patients with one of the antisynthetase antibodies (e.g., anti-Jo1, anti-PL7, and anti-PL12) have a syndrome (i.e. the antisynthetase syndrome) that includes myositis, interstitial lung disease, a non-erosive arthritis, mechanic’s hands, and/or Raynaud’s phenomenon (8), (b) amongst patients with cancer-associated DM, 83% (24/29) have antibodies against either TIF1γ or NXP2 (9), (c) anti-NXP2 positive patients frequently develop calcinosis (10), and (d) anti-MDA5 positive patients have prominent skin ulcerations and distinctive palmar papules (11, 12).

It has been shown that anti-SRP and anti-HMGCR autoantibodies are associated with necrotizing muscle biopsies and patients with these serologic profiles have IMNM/NAM (7). However, to date, no studies have systematically analyzed the association of distinct DM-associated autoantibodies with different histologic features routinely analyzed on a diagnostic muscle biopsy.

In this study, we identified all DM patients with banked serum and a muscle biopsy read at our institution. These sera were then screened for DM-specific autoantibodies including Mi-2, TIF1γ, NXP2, and MDA5. We also screened sera for Jo-1 autoantibodies, which are found in both DM and PM patients. In addition, we screened for Ro52 and PM-Scl, which, though sometimes associated with DM and PM, are not specific for patients with myositis. We then compared muscle biopsy features in DM patients with different autoantibodies to determine if unique histologic abnormalities are associated with different serological subtypes. In addition, since anti-Jo-1 positive patients may have either DM or PM (8), we also evaluated whether muscle biopsy features varied in these patients depending on whether they had a DM rash or not.

Material and methods

Patient population

Patients seen at the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center between 2006 and 2013 were included in this study if they had: (i) a Bohan and Peter (B&P) diagnosis of probable or definite DM (1), (ii) a muscle biopsy evaluated for clinical purposes at the Johns Hopkins Neuromuscular Pathology Laboratory, and (iii) banked serum to test for autoantibodies. Of note, only patients with unambiguous Gottron’s papules, Gottron’s sign, and/or heliotrope rash observed by ALM or LC-S were included; patients with only self-reported rashes were not included. Patients with B&P probable or definite PM who were positive for anti-Jo-1 and had a muscle biopsy read at Johns Hopkins were also included.

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins IRB and all participants signed informed consent.

Antibody assays

All DM serum samples included in the study were tested for the most common myositis-specific (anti-Jo1, anti-Mi2, anti-Tif1γ, anti-MDA5, and anti- NXP2) and myositis-associated antibodies (anti-Ro52 and anti-Pm-Scl). Autoantibody testing was performed specifically for this study in batches using the same methods during 2013 and 2014. Testing for autoantibodies only rarely found in DM (e.g., non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies) was not undertaken. Ro52 and Jo-1 antibodies were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (Inova Diagnostics). MDA5, NXP2, Mi2 and PM-ScL antibodies were assayed by immunoprecipitation using 35S-methionine labeled proteins generated by in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT) from the appropriate cDNAs as described (9). For PM-ScL, cDNAs encoding the 100 and 75 kD subunits were used to generate radiolabeled proteins, and both products were used in the immunoprecipitations to assess anti-PMScL antibodies. All IVTT immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and detected by fluorography. TIF1γ antibodies were assessed by immunoprecipitation using lysates made from cells transiently transfected with TIF1γ cDNA, followed by detection by immunoblotting as described previously (9).

Muscle biopsies

Muscle biopsies were prospectively interpreted as part of routine clinical care at the Johns Hopkins Neuromuscular Pathology Laboratory by a histopathologist who was blinded to autoantibody status and consistently reported on the presence or absence of perifascicular atrophy, COX-fibers, perivascular inflammation, primary inflammation (invasion of non-necrotic fibers by mononuclear cells) and necrosis/degeneration. 77 of 91 (85%) available biopsies were read by a single histopathologist (A.M.C.). To determine the interrater reliability between A.M.C. and the other histopathologists, we compared the readings of each using 15 random DM cases from those included in this study for each of the 5 features analyzed in this study. We found that there was excellent interrater agreement (κ=0.93). The muscle biopsy reports were retrospectively reviewed for muscle biopsy features. Electron microscopic features and specialized immunostainings were not included in the analysis. To classify patients according to the Bohan and Peter criteria, muscle biopsies were considered compatible with an inflammatory myopathy if they showed degeneration, necrosis, myophagocytosis, and/or mononuclear cell infiltrates. Muscle biopsies were defined as revealing a necrotizing myopathy if they included necrotic myofibers (without a predominant perifascicular distribution) in the absence of perifascicular atrophy or significant endomysial or perimysial inflammation (including any primary inflammation). A subset of biopsies were stained with cytochrome oxidase (COX) and succinic dehydrogenase (SDH) and mitochondrial dysfunction was defined as the presence of more than 5 COX-negative fibers per frozen section. Time from the onset of symptoms to the muscle biopsy, location of the muscle biopsy, and information about immunosuppressant treatment prior and during muscle biopsy were recorded as potential sources of bias.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages and absolute frequencies while quantitative variables were expressed as median, first and third quartiles. Fisheŕs exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare categorical and quantitative biopsy findings between different antibodies or antibody combinations in DM patients and between anti-Jo1 positive patients with DM and PM.

A Poisson regression study with robust variance estimates was performed to assess the influence of treatment, time from the onset of the disease to the biopsy and biopsy location (predictor variables) over the prevalence of the five biopsy features analyzed (perifascicular atrophy, perivascular inflammation, primary inflammation, predominantly necrotizing, and mitochondrial dysfunction), reporting the prevalence ratio (PR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and p value of significant results (13).

Because this was an exploratory study, a two-sided p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant for these analyses, with no correction for multiple comparisons.

Microsoft Access 2007 was used to do the data collection and the statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE 12.1 and SPSS 20.

Results

Antibody assays

The comercial assays for anti-Ro52 and anti-Jo-1 have been previously described and validated (14). Our assays for anti-NXP-2, anti-TIF1γ, and anti-MDA-5 have been described in detail and validated elsewhere (9). As part of the current study, we screened 34 healthy control sera using the anti-Mi-2 and and anti-PM-Scl assays; none of these tested positive.

Patients

91 adult DM (58 females, 82% B&P definite DM) patients were identified who had sera available and a muscle biopsy read at Johns Hopkins. 7 anti-Jo1 positive PM (6 females, 43% B&P definite PM) patients who had a muscle biopsy read at Hopkins were also included in the study (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). More than half of the DM patients were on treatment before (61%) and at the time of (56%) biopsy (Table 2). Most of the patients receiving immunosuppressants at the time of biopsy were treated with corticosteroids (47% of the patients treated at biopsy) while the most common immunosuppressant at the time of biopsy was methotrexate (8% treated during biopsy). (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects.

| DM (n=91) |

PM (n=7) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age at biopsy (years; median [Q1–Q3]) | 48 (37–60) | 39 (35–53) |

| Age at onset (years; median [Q1–Q3]) | 45 (34–58) | 38 (33–52) |

| Time from onset to biopsy (months; median [Q1–Q3]) | 10 (4–21) | 11 (1–15) |

| Sex (female % [n]) | 64% (58) | 86% (6) |

| Race (W/B/O* % [n]) | W: 68% (62) B: 15% (14) O: 16% (15) |

W: 71% (5) B: 14% (1) O: 14% (1) |

| Place of biopsy (Q/D/B/O** % [n]) | Q: 68% (42) D: 15% (37) B: 16% (8) U: 16% (4) |

Q: 57% (4) D: 29% (2) U: 14% (1) |

W/B/O: White/Black/Other

Q/D/B/U: Quadriceps/Deltoid/Biceps/Unknown

Table 2.

Muscle biopsy features, treatments, and duration of disease at biopsy according to autoantibody subsets in DM patients.

| All DM (n=91) |

All Jo-1 (n=13; 14%) |

Jo-1 with Ro-52 (n=9; 10%) |

Jo-1 without Ro-52 (n=4; 4%) |

Anti-Tif1γ (n=25; 27%) |

NXP2 (n=17; 19%) |

Mi2 (n=12; 13%) |

MDA5 (n=5; 5%) |

PM-Scl (n=9; 10%) |

Ro52 (n=22; 24%) |

No Antibody (n=15; 16%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perivascular inflammation | 56 (62%) | 9 (69%) | 8 (89%) | 1 (25%) | 16 (64%) | 11 (65%) | 10 (83%) | 1 (20%) | 7 (78%) | 15 (68%) | 6 (40%) |

| Perifascicular atrophy | 46 (51%) | 8 (62%) | 7 (78%) | 1 (25%) | 16 (64%) | 9 (53%) | 8 (67%) | 2 (40%) | 3 (33%) | 12 (55%) | 4 (27%) |

| Primary inflammation | 21 (23%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (67%) | 6 (27%) | 3 (20%) |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction* | 14 (28%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (47%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (29%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (29%) | 1 (14%) |

| Necrotizing myopathy | 15 (16%) | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (8%) | 3 (18%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) | 4 (18%) | 4 (27%) |

| Immunosuppresants prior to biopsy | 55 (61%) | 8 (62%) | 6 (67%) | 2 (50%) | 17 (71%) | 7 (44%) | 7 (58%) | 5 (100%) | 5 (56%) | 15 (68%) | 9 (60%) |

| On immunosuppressants during biopsy | 49 (56%) | 6 (55%) | 5 (63%) | 1 (33%) | 16 (67%) | 7 (44%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (44%) | 17 (81%) | 6 (40%) |

| Corticosteroids during biopsy | 42 (47%) | 4 (31%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (25%) | 14 (58%) | 6 (38%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (80%) | 3 (33%) | 14 (64%) | 5 (33%) |

| Days from the onset of symptoms to the biopsy (median [Q1–Q3]) | 290 (117–615) |

721 (531 −874) |

721 (599–1022) |

654 (275–802) |

270 (92 −561) |

125 (66–293) |

163 (58–402) |

403 (296–637) |

232 (114–1880) |

497 (291–874) |

435 (289–919) |

Since not all biopsies were stained with COX, mitochondrial dysfunction could not be assessed in all cases

Antibodies in DM

At least one antibody was detected in 76 patients (84%; Table 2). The most frequently detected antibodies were anti-Tif1γ (n=25, 27%), anti-Ro52 (n=22, 24%), anti-NXP2 (n=17, 19%) and anti-Jo1 (n=13, 14%). Around one-third of patients had more than one antibody specificity (n=27, 30%). Anti-Jo1 and anti- Ro52 were the two autoantibodies most frequently found in the same patient (n=9, 10% of the total sample, 69% of anti-Jo1 patients) (Table 2).

In 15 patients (16%), none of the antibodies systematically screened for in this study were detected. In some of these, other autoantibodies were detected either in our lab or in commercial labs. For example, 1 patient was anti-PL-12 positive and 1 patient was anti-U1RNP positive. Among the remaining 13 patients, immunoprecipitations from radioactively labeled HeLa cells revealed numerous unidentified bands, but no patterns were shared between the different patients (data not shown). Since these patients are unlikely to represent a serologically homogenous group, they were excluded from subgroup analyses.

Muscle biopsy features in DM

Perivascular inflammation (n=56, 62%) and perifascicular atrophy (n=46, 51%) were the most frequent muscle biopsy findings in DM patients (Table 2). Other less commonly observed features of DM included primary inflammation (n=21, 23%) and mitochondrial dysfunction, which was found in 14 of 50 (28%) biopsies stained with COX. A predominantly necrotizing myopathy was observed in some DM patients (n=15, 16%).

Regression analysis showed that the prevalence of each muscle biopsy feature was not significantly associated with the time from the onset of the disease to the biopsy. However, patients without immunosuppressant treatment during biopsy had an increased prevalence of perivascular inflammation (PR:1.38, 95% CI:1.00–1.90, p=0.05) and biopsies taken from deltoid muscle had significantly more perivascular inflammation (PR:2.16, 95% CI: 1.44–3.24, p<0.001), perifascicular atrophy (PR:1.88, 95% CI: 1.11–3.18, p=0.02), and mitocondrial dysfunction (PR:4.25, 95% CI: 1.02–17.80, p=0.05) than those obtained from quadriceps. Primary inflammation and necrotizing muscle biopsy findings were not significantly influenced by these potential confounders.

Correlating muscle biopsy features with autoantibody status in DM

We compared muscle biopsy features of all patients positive for each antibody with all those negative for the same antibody (Table 3). Univariate analysis revealed that Tif1γ+ patients had more mitochondrial dysfunction than Tif1γ- patients (47% vs 18%; p=0.05). NXP2+ patients had less primary inflammation than those without this autoantibody (0% vs 28%; p=0.01). In contrast, primary inflammation was more common in Mi-2+ (50% vs 19%; p=0.03) and PM-Scl+ patients (67% vs 18%; p=0.004) compared to those without the respective autoantibodies. Although reliability was limited due to small sample numbers, multivariate analysis confirmed that Tif1γ+ patients had more mitochondrial dysfunction (PR 2.6, 95%CI 1.0–6.5, p=0.05) and PM-Scl+ patients had more primary inflammation (PR 5.2, 95%CI 2.0–13.4; p=0.001) independent of disease duration at biopsy, biopsy site, and treatment at biopsy. There was excellent interrater agreement between the histopathologists that interpreted these biopsies (κ=0.93). However, we also performed univariate and multivariate analyses using only the 77 biopsies read by A.M.C. and the associations described above were conserved.

Table 3.

Histological features, treatment, and biopsy site characteristics of DM patients with and without individual DM autoantibodies.

| Jo1+ (n=13) | Jo1- (n=78) | p | Tif1g+ (n=25) | Tif1g- (n=66) | p | NXP2+ (n=17) | NXP2- (n=74) | p | Mi2+ (n=12) | Mi2- (n=79) | p | PMScl+ (n=9) | PMScl- (n=82) | p | MDA5+ (n=5) | MDA5- (n=86) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perifascicular atrophy | 62% | 49% | 0.6 | 64% | 45% | 0.2 | 53% | 50% | 1 | 67% | 48% | 0.4 | 33% | 52% | 0.3 | 40% | 51% | 0.7 |

| Perivascular inflammation | 69% | 60% | 0.8 | 64% | 61% | 0.8 | 65% | 61% | 1 | 83% | 58% | 0.1 | 78% | 60% | 0.5 | 20% | 64% | 0.1 |

| Primary inflammation | 31% | 22% | 0.5 | 12% | 27% | 0.2 | 0% | 28% | 0.01 | 50% | 19% | 0.03 | 67% | 18% | 0.004 | 0% | 24% | 0.6 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 25% | 29% | 1 | 47% | 18% | 0.05 | 25% | 29% | 1 | 29% | 28% | 1 | 0% | 30% | 0.6 | 50% | 27% | 0.5 |

| Necrotizing myopathy | 15% | 17% | 1 | 8% | 20% | 0.2 | 18% | 16% | 1 | 8% | 18% | 0.7 | 22% | 16% | 0.6 | 0% | 17% | 0.6 |

| Immunosuppresants prior to biopsy | 62% | 61% | 1 | 71% | 57% | 0.3 | 44% | 64% | 0.2 | 58% | 61% | 1 | 56% | 61% | 0.7 | 100% | 58% | 0.2 |

| Immunosuppressants at biopsy | 55% | 55% | 1 | 51% | 67% | 0.2 | 44% | 58% | 0.4 | 50% | 56% | 0.8 | 44% | 56% | 0.5 | 100% | 53% | 0.1 |

| Corticosteroids at biopsy | 31% | 49% | 0.4 | 58% | 42% | 0.2 | 38% | 48% | 0.6 | 50% | 45% | 1 | 33% | 48% | 0.5 | 80% | 44% | 0.2 |

| Days from onset of symptoms to biopsy (median [Q1–Q3]) | 721 (531–874) | 270 (114–497) | 0.02 | 270 (92–561) | 293 (128–721) | 0.5 | 125 (66–293) | 322 (153–777) | 0.01 | 163 (58–402) | 304 (128–663) | 0.1 | 232 (114–1880) | 293 (118–605) | 0.9 | 403 (296–637) | 288 (114–615) | 0.4 |

| Deltoid biopsy | 36% | 42% | 1 | 60% | 34% | 0.06 | 20% | 45% | 0.2 | 29% | 43% | 0.7 | 14% | 44% | 0.2 | 50% | 41% | 1 |

| Biceps biopsy | 9% | 7% | 1 | 0% | 10% | 0.3 | 20% | 5% | 0.1 | 0% | 8% | 1 | 0% | 8% | 1 | 0% | 8% | 1 |

| Quadriceps biopsy | 55% | 51% | 1 | 40% | 56% | 0.3 | 60% | 50% | 0.7 | 71% | 49% | 0.4 | 86% | 48% | 0.1 | 50% | 51% | 1 |

We also compared the prevalence of muscle biopsy features of each autoantibody subgroup against each of the other autoantibody subgroups. Statistically significant differences in the prevalence of primary inflammation were found between anti-Mi2 and anti-Tif1γ (p=0.005), between anti-Mi-2 and anti-NXP2 (p=0.002), between anti-PM-Scl and anti-Tif1γ (p=0.004), between anti-PM-Scl and anti-NXP2 (p<0.001), between anti-NXP2 and anti-Ro52 (p=0.03), between anti-PM-Scl and anti-MDA5 (p=0.03) and between anti-NXP2 and anti-Jo1 (p=0.03). Compared with biopsies from patients positive for both anti-Jo1 and anti-Ro52, biopsies from patients positive for anti-Jo-1 alone showed significantly less perivascular inflammation (p=0.05). Statistically significant differences in the prevalence of perivascular inflammation were also found between anti-MDA5 and anti-Mi2 (p=0.03).

Given that immunosuppressive treatment could affect muscle biopsy findings, we compared the prevalence of such treatment before biopsy and at the time of biopsy between each autoantibody subgroup. Anti-NXP2 patients were less frequently treated at biopsy than anti-Ro52 (p= 0.03) subjects and less frequently before biopsy than anti-MDA5 subjects (p= 0.05). The time between symptom onset and muscle biopsy was also evaluated between each antibody subgroup. The time from symptom onset to biopsy was longer in anti-MDA5 positive subjects compared to those with anti-NXP2 (p=0.03) and in those with anti-Jo1 compared to those with anti-Mi2 (p=0.02)) or anti-NXP2 (p=0.003). The interval between symptom onset and muscle biopsy was also longer in those with anti-Ro52 compared to those with either anti-NXP2 (p=0.003), anti-Tif1 (p=0.04), or anti-Mi2 biopsies (p=0.01). However, with the exception of comparisons with anti-MDA5 positive patients, who had long disease duration and were all treated at the time of biopsy, differences in treatment or disease duration at biopsy did not appear to account for differences in muscle biopsy features between the different autoantibody subgroups. Multivariate analyses to explore the role of potential confounders was not possible given the small size of individual autoantibody subgroups.

Comparison of muscle biopsy features between DM and PM in anti-Jo1 positive patients

There were no significant differences in muscle biopsy features between DM and PM patients who were positive for anti-Jo-1 (Table 4). Indeed, 3 of 7 (43%) PM patients had perifascicular atrophy, considered to be the hallmark feature of DM, and 4 of 13 (31%) DM patients had primary inflammation. Of note, there were no significant differences in treatment or duration of symptoms at the time of biopsy between anti-Jo-1 DM and PM patients.

Table 4.

Muscle biopsy features, treatments, and duration of disease in anti-Jo1 positive patients diagnosed with DM and PM.

| DM N (%) |

PM N (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perivascular inflammation | 9 (69.2%) | 6 (85.7%) | 0.6 |

| Perifascicular atrophy | 8 (61.5%) | 4 (57.1%) | 1 |

| Primary inflammation | 4 (30.8%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0.4 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction* | 2 (25.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 |

| Necrotizing myopathy | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.5 |

| Immunosuppression prior to biopsy | 8 (61.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0.6 |

| On immunosuppression during biopsy | 6 (54.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 |

| Corticosteroids during biopsy | 4 (30.8%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 |

| Days from the onset of symptoms to the biopsy (median [Q1–Q3]) | 725 (531–874) |

374 (37–435) |

0.1 |

Fisheŕs exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test p-values are shown for the categorical and quantitative variables respectively.

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically compare muscle biopsies from DM patients with different autoantibodies. Certain features were relatively common among most DM patients regardless of autoantibody specificity. These included perivascular inflammation and perifascicular atrophy, which were found in 62% and 51% of all DM patients, respectively. In contrast, mitochondrial dysfunction, a previously described feature in DM muscle biopsies (6), was relatively rare (28%) except in those with anti-TIF1γ where it was found in 47% of patients. However, the prevalence of other muscle biopsy features varied significantly depending upon the autoantibody status. Most strikingly, primary inflammation was present in the majority of 21 patients with antibodies against either Mi-2 (50%) or PM-Scl (67%) but not in any of the 17 anti-NXP2 patients.

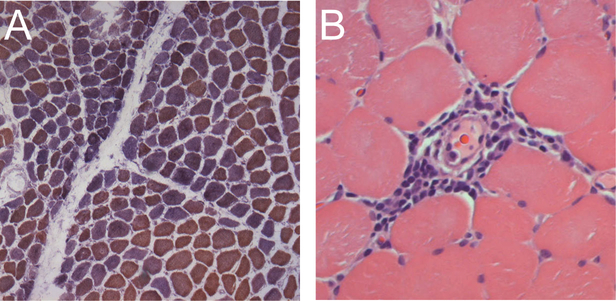

This study reveals for the first time that patients with anti-TIF1γ and anti- NXP-2 have very similar histologic profiles, with prominent perifascicular atrophy and perivascular inflammation but very little primary inflammation. The main difference between muscle biopsies in patients with these two serologies is that only anti-TIF1γ patients have a relatively high prevalence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Figure 1 shows an example of a typical TIF1γ muscle biopsy with perifascicular atrophy, perivascular inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Typical muscle biopsy from an anti-Tif1γ positive DM patient. (A) This low power view of a frozen section stained with COX (brown) and SDH (blue) reveals both normal fibers (brown) and numerous COX-deficient fibers (purple/blue) indicating mitochondrial dysfunction; several fascicles include examples of perifascicular atrophy. (B) This high power view of a paraffin section from the same patient stained with H&E shows a striking example of perivascular inflammation.

Patients with anti-Mi-2 antibodies had the highest prevalence of perifascicular atrophy (67%) and perivascular inflammation (83%) compared to those with one of the other DM-specific autoantibodies (although this was not stastically significant). They also had a higher prevalence of primary inflammation (51%) compared to those with other DM- specific autoantibodies, although anti-PM-Scl positive patients had an even higher prevalence (67%) of this pathologic feature. Of note, patients with anti-Mi-2 are known to have other distinctive clinical features including a severe rash that responds well to immunosuppression and a low cancer rate (15).

Although previously investigated in juvenile DM patients (16), this study includes the first description of muscle biopsies from adult anti-MDA5 positive DM patients. Despite the fact that anti-MDA5 has been linked with clinically amyopathic DM (12), we had 5 biopsies available from patients with this immunospecificity who had two or more myopathic features required for a diagnosis of probable or definite DM by B&P criteria (i.e., proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, irritable myopathy on EMG, and/or characteristic muscle biopsy features). Compared to other adult DM patients, these anti-MDA5 positive subjects had a low prevalence of the histologic features analyzed in this study, including perivascular inflammation, primary inflammation, and perifascicular atrophy. Scattered atrophic fibers were the only histologic abnormality noted on 3 of 5 biopsies from the anti-MDA5 positive subjects. We speculate that the high frequency of treatment at the time of biopsy (100%) may account for the relatively bland biopsies. Indeed, our regression analysis indicated that perivascular inflammation is less prevalent when patients are treated before muscle biopsy.

Approximately one-third of patients were positive for more than one of the autoantibodies we screened for, especially the combination of anti-Jo1 and anti- Ro52. It is well established that the combination of these antibodies may be associated with severe myositis and joint impairment (17, 18). Thus, it is of interest that in the current study we found a significant higher prevalence of perivascular inflammation in anti-Jo1 with anti-Ro52 compared with anti-Jo1 alone (89% vs 25%, p=0.05), suggesting a more intense inflammatory phenomenon in the former group of patients.

In addition to comparing the muscle biopsy features in DM patients with different autoantibodies, we also compared the muscle biopsies of anti-Jo-1 positive patients who were diagnosed with either DM or PM based on B&P criteria. Surprisingly, there were no significant differences in the basic histologic features between anti-Jo-1 positive patients with and without a typical DM rash. Indeed 4 of 7 (57%) anti-Jo-1 positive patients without rash were found to have perifascicular atrophy, considered to be a hallmark histologic feature of DM (2). Based on these findings and a lack of data indicating that anti-Jo-1 positive patients with and without rash are pathophysiologically distinct, we suggest that all anti-Jo-1 positive patients have the same disease and should not be categorized as having DM or PM. Rather, we propose that the anti-Jo-1 syndrome could be considered a single entity characterized by the presence of the antibody along with two or more of the following features of the antisynthetase syndrome: myositis, interstitial lung disease, rash, arthritis, mechanic’s hands, and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Of note, this study showed that 16% of patients with B&P probable or definite DM did not have perifascicular atrophy, primary inflammation, or perivascular inflammation on muscle biopsy. Rather, almost one in six DM patients have a necrotizing muscle biopsy that cannot readily be distinguished from patients with IMNM/NAM and either anti-SRP or anti-HMGCR autoantibodies (7). Therefore, in clinical practice, it may be that only autoantibody testing can reliably distinguish between a patient with DM sine dermatitis and IMNM/NAM.

Interestingly, Poisson regression analysis showed that biopsies from the deltoid muscle and those taken during periods without immunosuppressant treatment were more likely to have perivascular inflammation and perifascicular atrophy. This suggests that the diagnostic performance of the muscle biopsy may be influenced by both treatment and muscle biopsy location.

This study has a number of limitations. First, given the rarity of DM, the number of patients studied in some antibody groups was small (i.e., MDA5 and PM-Scl) and consequently the study may have been underpowered to detect all clinically relevant associations. Second, except for anti-Jo-1 patients with and without anti-Ro52, we did not have adequate numbers of patients with the same combination of multiple antibodies to study these as distinct groups. Third, although all muscle biopsies were interpreted at Johns Hopkins, the biopsies were performed at various institutions, biopsy location was highly variable, and muscle tissue was not available for further study for a majority of the study subjects. Therefore, we utilized only those features that were assessed for clinical purposes using routine histological methods. Fourth, muscle biopsy features were categorized as either present or absent and so severity of these features could not be compared between subgroups. Fifth, the analysis did not include electron microscopy or specialized immunostaining for major histocompatibility complex I, the membrane attack complex, or inflammatory cell subsets (e.g., CD8 positive cells). Comparing specialized immunostaining in DM patients with different autoantibodies would be of interest. Sixth, not all biopsies included in this study were stained for COX, so the data on mitochondrial dysfunction is not complete. Finally, despite the differences we have emphasized, it should be noted that even among those with a given autoantibody, there is considerable variability in the observed muscle biopsy features. Thus, an individual’s autoantibody status cannot be reliably inferred from the histologic features noted on muscle biopsy.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study provides the first comparative description of muscle biopsies from DM patients with different autoantibodies. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that the prevalence of different histological features varies according to autoantibody status in DM. This raises the possibility that different pathologic pathways underlie muscle disease in patients with different autoantibodies. Along with prior work showing that each autoantibody is associated with different disease manifestations (e.g, cancer), our findings further support the conclusion that DM is not a homogenous entity, but may consist of several different diseases with distinct biomarkers (i.e., autoantibodies). Our findings also support the possibility that patients with anti-Jo- 1 antibodies have a single disease, the antisynthetase syndrome (rather than PM or DM), which sometimes includes rash as a prominent feature. This framework for understanding the relationship between different autoantibodies and distinct disease states remains to be validated in other cohorts.

Funding:

The Johns Hopkins Rheumatic Disease Research Core Center, where the autoantibody assays were performed, is supported by NIH grant P30-AR- 053503. LCR is supported by R56 AR062615-01A1. Dr. Christopher-Stine’s work was supported by the Huayi and Siuling Zhang Discovery Fund. This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Iago Pinal-Fernandez, Autoimmune Systemic Diseases Unit, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain.

Livia A. Casciola-Rosen, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Lisa Christopher-Stine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Andrea M. Corse, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Andrew L. Mammen, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts). N Engl J Med 1975;292:403–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogendijk JE, Amato AA, Lecky BR, Choy EH, Lundberg IE, Rose MR, et al. 119th ENMC international workshop: trial design in adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, with the exception of inclusion body myositis, 10–12 October 2003, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord 2004;14:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet 2003;362:971–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanimoto K, Nakano K, Kano S, Mori S, Ueki H, Nishitani H, et al. Classification criteria for polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 1995;22:668–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targoff IN, Miller FW, Medsger TA Jr, Oddis CV. Classification criteria for the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997;9:527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varadhachary AS, Weihl CC, Pestronk A. Mitochondrial pathology in immune and inflammatory myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010;22:651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allenbach Y, Benveniste O. Acquired necrotizing myopathies. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzap E, Barilla-LaBarca ML, Marder G. Antisynthetase syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentino DF, Chung LS, Christopher-Stine L, Zaba L, Li S, Mammen AL, et al. Most Patients With Cancer-Associated Dermatomyositis Have Antibodies to Nuclear Matrix Protein NXP-2 or Transcription Intermediary Factor 1gamma. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2954–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunawardena H, Wedderburn LR, Chinoy H, Betteridge ZE, North J, Ollier WE, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd protein in juvenile dermatomyositis are associated with calcinosis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1807–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaisson NF, Paik J, Orbai AM, Casciola-Rosen L, Fiorentino D, Danoff S, et al. A Novel Dermato-Pulmonary Syndrome Associated With MDA-5 Antibodies: Report of 2 Cases and Review of the Literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91:220–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentow C, Swart A, Wu J, Seaman A, Manfredi M, Infantino M, et al. Clinical performance evaluation of a novel rapid response chemiluminescent immunoassay for the detection of autoantibodies to extractable nuclear antigens. Clin Chim Acta 2013;424:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casciola-Rosen L, Mammen AL. Myositis autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012;24:602–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tansley SL, Betteridge ZE, Gunawardena H, Jacques TS, Owens CM, Pilkington C, et al. Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies in juvenile dermatomyositis identify a distinct clinical phenotype: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutjes SA, Vree Egberts WT, Jongen P, Van Den Hoogen F, Pruijn GJ, Van Venrooij WJ. Anti-Ro52 antibodies frequently co-occur with anti-Jo-1 antibodies in sera from patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1997;109:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marie I, Hatron PY, Dominique S, Cherin P, Mouthon L, Menard JF, et al. Short-term and long-term outcome of anti-Jo1-positive patients with anti-Ro52 antibody. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012;41:890–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]