Abstract

SUMMARY – A rare case of necrotizing hypophysitis (NH) in a 52-year-old man presenting with pituitary apoplexy and sterile meningitis is described. This case indicates that the diagnosis of NH could be made without biopsy, based on concomitant presence of diabetes insipidus, hypopituitarism and radiologic features of ischemic pituitary apoplexy. Conservative management of pituitary apoplexy should be advised in NH. Additionally, this is the first report of a case of sterile meningitis caused by ischemic pituitary apoplexy.

Key words: Stroke, Diabetes insipidus, Hypopituitarism, Hypophysitis, Pituitary apoplexy, Meningitis

Introduction

Hypophysitis is a rare inflammatory disorder associated with diffuse enlargement and dysfunction of the pituitary gland, with estimated prevalence of 0.88% (1). During the preoperative period, it is misdiagnosed as pituitary adenoma in up to 40% of cases (2), although these two clinical entities can be readily distinguished based on the absence of diabetes insipidus in patients with adenoma (1). Several radiologic markers on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are indicative of hypophysitis, i.e. pituitary stalk thickening, pituitary enlargement, intense homogeneous post-contrast imbibition in adenohypophysis, and absence of high-intense signal in neurohypophysis on T1-weighted images (3). Based on histopathologic examination, which is needed to confirm the diagnosis, primary hypophysitis can be categorized into five groups: lymphocytic, granulomatous, xanthomatous, IgG4 plasmacytic, and necrotizing hypophysitis (NH) (2). NH is the rarest type, with only 3 cases reported in the literature so far (4, 5). Here we present another patient with biopsy-proven NH, and discuss its pathogenesis, clinical presentation and treatment options.

Case Report

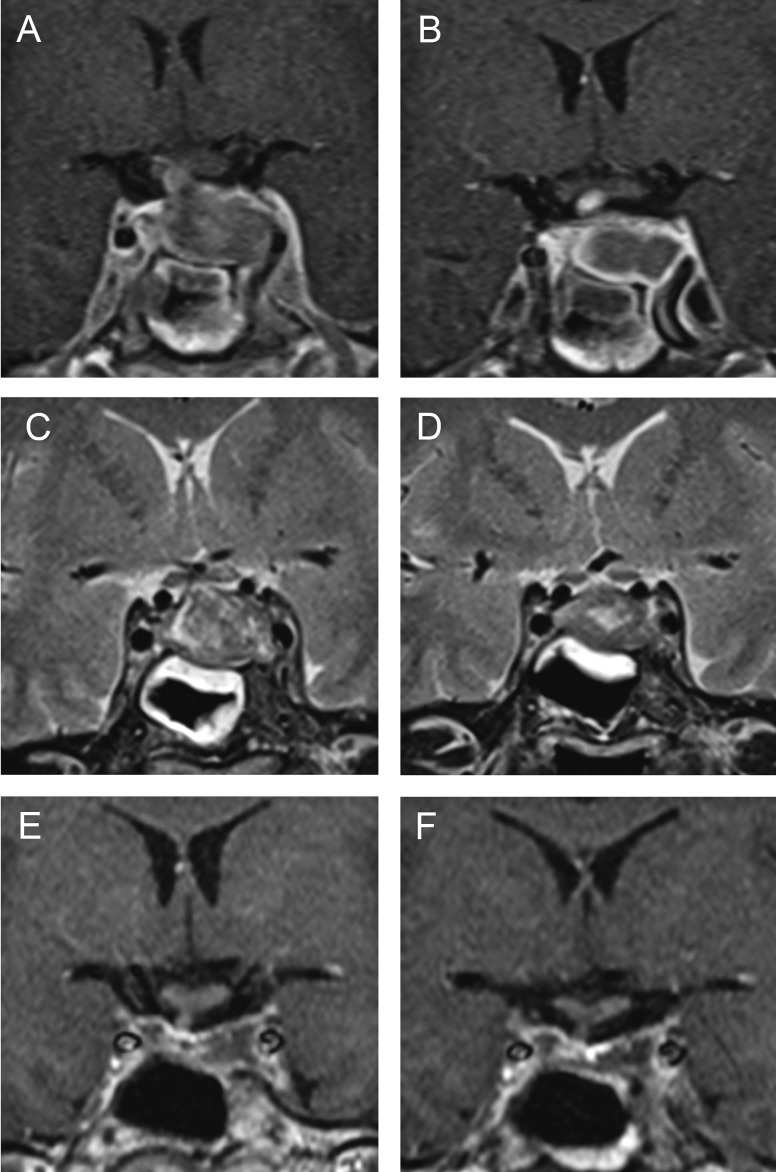

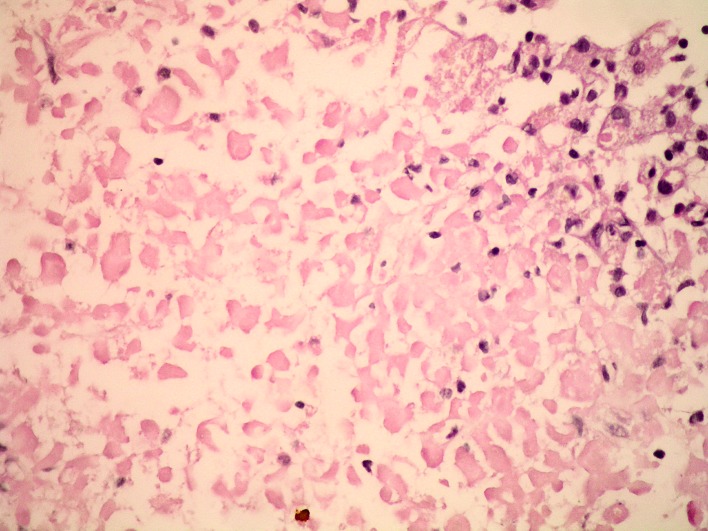

A 52-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with rapidly progressive headache, vomiting and photophobia. His medical history was unremarkable. On admission, he had normal blood pressure, normal heart rate and axillary temperature of 37.5 oC. Physical examination was unremarkable. His complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP) and electrolyte panel were all normal; slightly low urine specific gravity was noted (1.003 g/L). Computed tomography scan showed inhomogeneous intrasellar mass suggestive of pituitary adenoma. His headache intensified and paresis of the left third cranial nerve developed two days after admission. He became febrile up to 39.8 oC, with marked neck stiffness and excessive diuresis (10 L of urine per day). CRP increased to 82 mg/L but his CBC remained normal. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) suggested sterile meningitis (glucose level 4.4 mmol/L, protein concentration 1.0 g/L and white blood cell count 46/mm3 (90% of lymphocytes)). MRI performed two days after symptom onset demonstrated diffusely enlarged pituitary gland (23x15x17 mm), which was slightly hypointense to isointense to the gray matter on T1-weighted images, with thickened pituitary stalk (Fig. 1 A, B). Hypophysitis was suspected, although dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging did not show enhancement within the enlarged pituitary gland. Thickened sphenoid sinus mucosa along with sudden symptom onset suggested pituitary apoplexy. Endocrinologic evaluation revealed adrenal insufficiency (morning serum cortisol of 30 nmol/L) and diabetes insipidus (urine osmolality of 106 mOsm/kg). Hydrocortisone and desmopressin replacement therapy was administered. The patient’s headache, fever and third cranial nerve palsy resolved spontaneously seven days after the onset. Follow up lumbar puncture confirmed aseptic meningitis (glucose level of 3.3 mmol/L, protein concentration of 1.83 g/L, and white blood cell count of 420/mm3 (70% of monocytes)). CSF testing was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Cryptococcus, and other fungi. Serologic analysis was negative for toxoplasma, Treponema pallidum, tick-borne encephalitis, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, Borrelia burgdorferi and human herpes virus 6. Follow up MRI performed twelve days after symptom onset (Fig. 1 B, D) showed enlarged pituitary gland that was profoundly hypointense to the gray matter on T1-weighted images, with only rim enhancement detected on post-contrast images, a finding suggestive of ischemic necrosis. Thickening of the sphenoid sinus mucosa diminished substantially. Detailed endocrinologic evaluation confirmed adrenal insufficiency (cortisol 7.7 nnmol/L, range 138-800 and cortisol in urine <20 nnmol/24 h, range 72.5-372), hypogonadism (luteinizing hormone 1.1 IU/L, range 1.7-8.6 and testosterone levels <0.4 nnmol/L, range 6.7-25.7), hypothyroidism (thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.1 mIU/L, range 0.4-4.0 and thyroxin (T4) 45 nmol/L, range 60-165) and growth hormone deficiency (insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) 38.6 ng/mL, range 115-420). The patient underwent endoscopic transsphenoidal resection followed by total hypophysectomy because the diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy was assumed. It is important to note that the patient was admitted to our hospital 20 days from symptom onset and therefore did not undergo immediate surgery. Macroscopic examination of the sellar content showed a non-hemorrhagic grayish and soft tumorous mass without any traces of normal tissue, while histopathologic examination revealed necrotic pituitary tissue surrounded by siderophages and mononuclear inflammation cells (Fig. 2). There was no evidence for infiltrative, infective, or neoplastic processes. The diagnosis of NH was established, and replacement therapy with hydrocortisone 30 mg/day, levothyroxine 75 mcg/day, desmopressin 60 mcg/day and testosterone undecanoate 1000 mg/12 weeks was initiated. MRI performed four months after the surgery showed residual necrotic pituitary tissue measuring 12 mm within the left cavernous sinus (Fig. 1 E). This MRI finding remained unchanged 18 months later (Fig. 1 F). The patient remained well after the surgery.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with necrotizing hypophysitis showing lack of enhancement within enlarged pituitary gland on contrast-enhanced imaging, which is hypointense to isointense to the gray matter on T1-weighted images and thickened pituitary stalk (A); progression of ischemia 12 days after symptom onset with rim enhancement on T1-weighted images (B); thickened sphenoidal sinus mucosa on T2-weighted images (C), and regression of edema twelve days after symptom onset (D); residual necrotic pituitary tissue on contrast-enhanced imaging 4 (E) and 18 (F) months after the surgery.

Fig. 2.

Section of the inflamed pituitary gland showing necrotic pituitary tissue, marginally surrounded by siderophages and mononuclear inflammation cells (hematoxylin-eosin (HE), X400).

Discussion

Necrotizing hypophysitis is an extremely rare clinical entity of unknown etiology, the diagnosis of which is currently established by combining endocrinologic, radiologic and histopathologic findings (2). Concomitant presence of hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus in a patient with sellar mass should raise suspicion of hypophysitis. Typical radiologic findings include pituitary stalk thickening, pituitary enlargement and pronounced enhancement in the pituitary gland on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (6). However, NH is the only type of hypophysitis presenting with lack of contrast enhancement, which is attributable to the histopathologic finding of ischemic pituitary apoplexy, and is one of the reasons it is often unrecognized and misinterpreted as pituitary adenoma. However, it should be noted that pituitary adenomas do not cause diabetes insipidus (3). Therefore, the triad of sudden-onset hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus and radiologic findings of ischemic pituitary apoplexy should be a strong indicator of NH.

All three previously published cases of NH presented acutely with sudden and severe headache, such as in our case. All of them had hypopituitarism, but diabetes insipidus was absent in one patient (4). In all three cases, MRI showed isointense to hypointense sellar mass on T1-weighted sequences with thickened pituitary stalk and only rim contrast enhancement. Thus, we believe that the radiologic finding of ischemic pituitary apoplexy coupled with the presence of diabetes insipidus should be sufficient for diagnosis of NH, although a larger study is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Our experience also suggests a possibility of conservative management of idiopathic hypophysitis. Although transsphenoidal surgery is a safe and effective method in the treatment of pituitary apoplexy (7), conservative approach might be just as effective in patients experiencing milder symptoms without visual abnormalities (8). Headache and diplopia in our patient resolved spontaneously, suggesting that conservative management might have been successful in this case. Moreover, residual necrotic pituitary tissue remained unchanged 18 months after the surgery and the patient experienced no symptoms. Hence, transsphenoidal surgery might not be mandatory in the treatment of NH.

The cause of NH remains uncertain. However, since all common bacterial and viral infections were ruled out, it is plausible to state that it likely represents an autoimmune disease in which inflammation and limitation of blood flow cause ischemic necrosis via an unknown mechanism.

Here we report the first case of concomitant sterile meningitis caused by ischemic necrosis, which was previously associated only with rare instances of hemorrhagic pituitary apoplexy (9). Since CSF infection was ruled out, we suggest that proinflammatory cytokines and debris released from necrotic pituitary gland could cause meningeal irritation and subsequently lead to sterile meningitis.

In summary, NH is an idiopathic disease that presents with sudden-onset hypopituitarism, neural compression, diabetes insipidus and radiologic features of ischemic pituitary apoplexy. Definitive diagnosis of NH could be made in patients with all these clinical elements, without the need for histopathologic confirmation. Conservative management could be considered in patients with NH.

References

- 1.Caturegli P, Newschaffer C, Olivi A, Pomper MG, Burger PC, Rose NR. Autoimmune hypophysitis. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:599–614. 10.1210/er.2004-0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutenberg A, Larsen J, Lupi I, Rohde V, Caturegli P. A radiologic score to distinguish autoimmune hypophysitis from nonsecreting pituitary adenoma preoperatively. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1766–72. 10.3174/ajnr.A1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakata Y, Sato N, Masumoto T, Mori H, Akai H, Nobusawa H, et al. Parasellar T2 dark sign on MR imaging in patients with lymphocytic hypophysitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1944–50. 10.3174/ajnr.A2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed SR, Aiello DP, Page R, Hopper K, Towfighi J, Santen RJ. Necrotizing infundibulo-hypophysitis: a unique syndrome of diabetes insipidus and hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1499–504. 10.1210/jcem.76.6.8501157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutenberg A, Caturegli P, Metz I, Martinez R, Brück W, Rohde V. Necrotizing infundibulo-hypophysitis: an entity too rare to be true? Pituitary. 2012;15:202–8. 10.1007/s11102-011-0307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamel N, Ilgin SD, Güllü S, Tonyukuk VC, Deda H. Lymphocytic hypophysitis and infundibuloneurohypophysitis; clinical and pathological evaluations. Endocr J. 1999;46:505–12. 10.1507/endocrj.46.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semple PL, Webb MK, de Villiers JC, Laws ER., Jr Pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:65–72. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000144840.55247.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayuk J, McGregor EJ, Mitchell RD, Gittoes NJ. Acute management of pituitary apoplexy – surgery or conservative management? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61:747–52. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valente M, Marroni M, Stagni G, Floridi P, Perriello G, Santeusanio F. Acute sterile meningitis as a primary manifestation of pituitary apoplexy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:754–7. 10.1007/BF03347359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]