Abstract

The multitude of research clarifying critical factors in embryonic organ development has been instrumental in human stem cell research. Mammalian organogenesis serves as the archetype for directed differentiation protocols, subdividing the process into a series of distinct intermediate stages that can be chemically induced and monitored for the expression of stage-specific markers. Significant advances over the past few years include established directed differentiation protocols of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into human kidney organoids in vitro. Human kidney tissue in vitro simulate the in vivo response when subject to nephrotoxins, providing a novel screening platform during drug discovery to facilitate identification of lead candidates, reduce developmental expenditures, and reduce future rates of drug-induced acute kidney injury. Patient-derived hiPSCs, which bear naturally occurring DNA mutations, may allow for modeling of human genetic diseases to determine pathologic mechanisms and screen for novel therapeutics. In addition, recent advances in genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 enable to generate specific mutations to study genetic disease with non-mutated lines serving as an ideal isogenic control. The growing population of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a world-wide healthcare problem with higher morbidity and mortality that warrants the discovery of novel forms of renal replacement therapy. Coupling the outlined advances in hiPSC research with innovative bioengineering techniques, such as decellularized kidney and 3D printed scaffolds, may contribute to the development of bioengineered transplantable human kidney tissue as a means of renal replacement therapy.

Keywords: Kidney, Organoid, mini-organ, iPS, Pluripotent stem cell, Directed differentiation, Kidney development, Glomeruli, Tissue engineering

Introduction

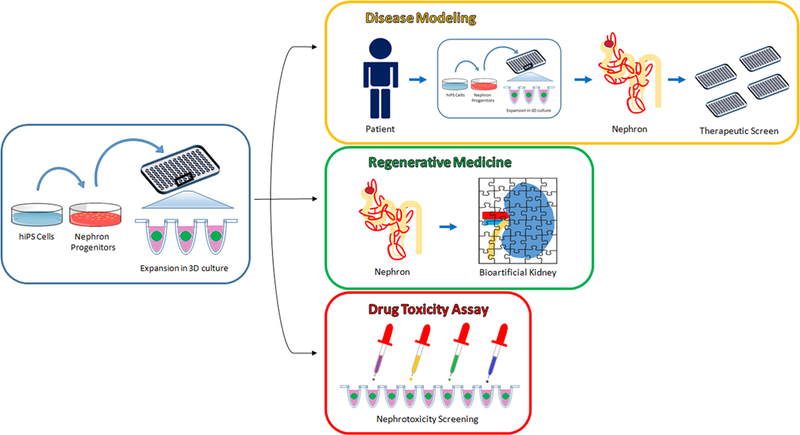

Decades of developmental studies have elucidated the molecular pathways and genes necessary for normal kidney development. Historically, these studies enabled an understanding of human kidney developmental disease processes, but largely have not translated into effective treatment as human kidney development ceases prior to birth. There has been a renaissance in developmental biology with the advent of research involving human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). By definition, hPSCs have the ability to differentiate into cells of the 3 germ layers, namely the mesoderm, ectoderm, and endoderm.1,2 Through directed differentiation, the sequential application of growth factors at specific concentrations for defined periods of time, hPSCs can be transformed into particular organ tissues with a high degree of efficiency. Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), a subset of hPSCs, are generated from reprogramming adult cells through the activation of transcription factors characteristic of pluripotency.2,3 Starting with any individual’s terminally differentiated cells, an unlimited supply of isogenic hiPSCs can be generated. Genomic retention permits modeling of genetic disease and provides an immunocompatible cell source for organ regeneration. The known physiology of vertebrate organogenesis serves as a guide towards the directed differentiation of hPSCs into human tissue. Drawing from studies of vertebrate kidney development, researchers have discovered directed differentiation protocols that derive human kidney tissue in vitro.4–10 Such human kidney tissue in-a-dish, potentially coupled with advances in biomedical engineering, may prove to revolutionize the fields of drug discovery, disease modeling, and kidney regenerative medicine (Fig. 1).11

Figure 1: Translational applications of hiPSC-derived kidney organoids.

The discovery of directed differentiation protocols for the generation of 3-dimensional kidney organoids from hiPSCs may provide for numerous translational applications, including human genetic and congenital disease modeling, kidney regenerative medicine, and nephrotoxicity screening during drug development.

Vertebrate Kidney Development

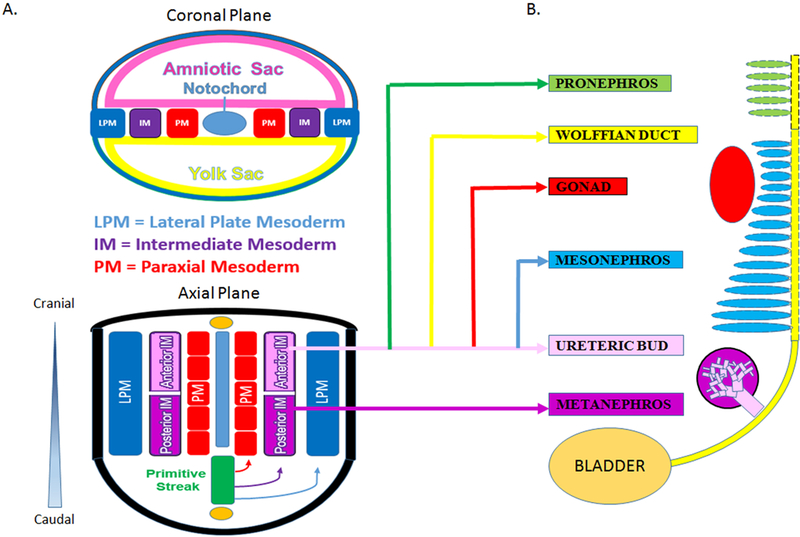

The vertebrate kidney derives from the intermediate mesoderm (IM) of the mesodermal germ layer. During kidney organogenesis, the IM sequentially gives rise to the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. In humans, the pronephros remains nonfunctional, regressing by the fourth week of gestation. The mesonephros forms just prior to degeneration of the pronephros in humans and serves as the primary excretory organ from the fourth to the eighth week of gestation. In females, the mesonephros degenerates, whereas in males it gives rise to portions of the gonads. The metanephros, which begins to form caudal to the mesonephros in the fifth week of gestation, becomes the definitive adult kidney in humans (Fig. 2A).12

Figure 2: Developmental of the vertebrate kidney.

A. Vertebrate kidney development involves the serial progression of three distinct structures derived from the intermediate mesoderm, the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. The pronephros is non-functional and regresses, the mesonephros provides primary exocrine functions until the eighth week of gestation, and the metanephros becomes the mature kidney in humans. Notably, the caudal portion of the mesonephric duct forms portions of the gonads in the male, while regressing in females. Each nephric stage associates with a collecting duct network derived from the Wolffian (or nephric) duct. B. The ureteric bud is an outpouching of the Wolffian duct (WD), which derives from the anterior intermediate mesoderm (aIM). The Metanephric Mesenchyme contains the progenitor cells of all kidney epithelia, save the collecting duct, and derives from the posterior intermediate mesoderm (pIM).

The metanephric kidney forms through the reciprocally inductive interactions between two distinct IM tissues, the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) and ureteric bud (UB).4 The MM arises from the posterior IM and contains a population of multipotent nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) that expresses the transcription factors Six2, Cited1, Pax2, Sall1, and Wt1.4,13–15 The Six2+ NPCs cluster to form the cap mesenchyme around each infiltrating UB tip.15 UB-derived Wnt signals induce NPCs to undergo mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, giving rise to nearly all the epithelial cells of the nephron except for those of the collecting duct.15,16 Meanwhile, the UB arises as an epithelial outpouching from the caudal Wolffian (or nephric) duct, which upon receiving inductive signals from the MM, undergoes iterative branching to form the collecting duct system of the kidney. Nephrogenesis in humans is completed between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation and results in the formation of approximately one million nephrons in each kidney. After birth, no new nephrons are formed, even under circumstances of kidney injury and repair.17,18

Recent work from Taguchi and colleagues has provided important insight into the embryonic origins of NPCs in the MM (4). Employing lineage tracing techniques in mice, the authors demonstrated that NPCs are derived from a population of T+ cells in the primitive streak that persists to give rise to T+Tbx6+ posterior nascent mesoderm followed by Wt1+Osr1+ posterior IM. In contrast, the UB originates from a Pax2+ cell population known to be limited to the anterior IM14,19,20 and is incapable of giving rise to MM (Fig. 2B). Thus, careful consideration of these diverging developmental pathways is critical for the efficient differentiation of PSCs into cells of these two different lineages.

Current strategies to direct the differentiation of hPSCs into cells of the kidney lineage have been based on vertebrate animal kidney development models.4,7,8 Key transcription factors, growth factors, and membrane protein factors involved in kidney organogenesis have been identified using gene knock-out and transgenic models with resultant phenotype demonstrating congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) (Table 121–38). These factors serve as critical markers of kidney induction during directed differentiation of hPSCs.

Table 1.

Genetic knockout and transgenic mouse models of kidney development

| Gene Knockout or Mutation | Kidney Phenotype | Related Human Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Mesoderm (IM) | ||

| Eya1 | Renal agenesis, lack of UB branching21 | Brachio-oto-renal syndrome22 |

| Lim1/LHX1 | Renal agenesis, UB branching defect, hydroureter23 | Mayer-Rokitanski-Kuster-Hauser syndrome24 |

| Osr1 | Renal agenesis25 | |

| Wt1 | Renal and gonadal agenesis26 | Wilms tumor, Denys-Drash syndrome27 |

| Ureteric Bud (UB) | ||

| Gata3 | Renal agenesis, ectopic ureteric budding28 | N/A (Embryonic lethal in mice29) |

| Pax2 | Renal agenesis30 | CAKUT, Renal-coloboma syndrome31,32 |

| Pax8 | Severe renal hypoplasia, reduced EB branching33 | |

| Metanephric Mesenchyme (MM) | ||

| Sall1 | Severe renal hypoplasia34 | Townes-Brock syndrome35 |

| Six2 | Renal hypoplasia, depletion of nephron progenitor cells16 | |

| MM-UB Reciprocal Induction | ||

| Gdnf | Renal agenesis36 | Stillbirth37 |

| Ret | Renal agenesis38 | MEN IIA and MEN IIB38 |

Pluripotent Stem Cells

PSCs represent early embryonic progenitor cells, believed to correspond to the blastocyst or epiblast stage of mammalian embryos.39 Cells at this stage arise 5–9 days post-conception in humans and are defined by two intrinsic properties: self-renewal and pluripotency. PSCs have the ability to self-renew indefinitely in culture, without transformation or differentiation. Additionally, PSCs are pluripotent, having the capacity to give rise to all cell types derived from the three embryonic germ layers, namely the mesoderm, endoderm, and ectoderm.40

PSCs are comprised of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). ESCs are derived from the isolation and culture of cells from the inner cell mass of the embryonic blastocyst.1 In contrast, iPSCs are generated following the activation of four key transcription factors of pluripotency (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) in terminally differentiated cells, which directly reprograms them into cells that behave similarly to and appear morphologically identical to ESCs.2,3

Although human ESCs (hESCs) remain the gold standard for stem cell research, hiPSCs have a number of advantages. Unlike hESCs, the derivation of iPSCs does not involve the use of human embryos, a limitation that has led to ethical concerns over the use of hESCs.41 Protocols now exist to derive hiPSCs from a variety of different terminally differentiated cell types, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells, keratinocytes, hepatocytes, urothelial cells, neural stem cells, and kidney mesangial and tubular epithelial cells using both viral and non-viral reprogramming methods.42–48 hiPSCs can be generated from any human being, healthy or diseased, with retention of the host individual’s genome. Therefore, hiPSCs represent an isogenic substrate to generate theoretically immunocompatible tissue for organ regeneration. Additionally, hiPSCs, generated from patients with genetic diseases, can be used to develop in vitro models to better study disease pathogenesis. For diseases that are particularly rare or do not have relevant animal models, iPSCs offer a novel strategy to study disease mechanisms and develop new therapeutics.

In the absence of exogenous growth factors or chemicals, PSCs undergo stochastic differentiation into embryoid bodies (EBs) in vitro and teratomas in vivo.1–3 Both EBs and teratomas are heterogeneous tissues that contain cells of the three embryonic germ layers. The heterogeneity of the tissue confirms pluripotency, but imparts a low induction efficiency of any one specific cell type. Directed differentiation refers to the process by which PSCs are sequentially treated with growth factors and chemicals to efficiently induce a particular cell or tissue type of interest. Directed differentiation protocols often employ a stepwise approach, through intermediate developmental stages, that mirrors normal embryonic organogenesis.49

Differentiation of hPSCs to Kidney Lineage Cells

Chronologically, the earliest work to obtain IM from hESCs involved the generation of WT1+ and PAX2+ kidney precursor cells.50,51 Shortly thereafter, protocols to directly generate cells bearing markers of terminal kidney epithelia were published. Podocin+Synaptopodin+PAX2+ podocyte-like cells were induced in EBs from hiPSCs using a combination of activin, BMP7, and retinoic acid.52 Through a similar protocol, a monolayer culture of these podocyte-like cells was shown to integrate into WT1+ glomerular structures, when combined with dissociated-reaggregated embryonic mouse kidneys. In renal epithelial growth medium, a combination of BMP2 and BMP7 induced the differentiation of hESCs to aquaporin-1 (AQP1)+ proximal tubule-like cells. Flow-sorted AQP1+ cells integrated into tubular compartments of ex vivo newborn mouse kidneys and spontaneously formed cord-like structures when cultured on Matrigel. AQP1+ cells increased cAMP production in response to exogenous parathyroid hormone, demonstrated functional γ-glutamyl transferase enzymatic activity, and produced ammonia.53

Recent studies have focused on the efficient induction of kidney progenitor cells, particularly cells of the IM and MM. An OSR1-GFP hiPSC line was treated with the combination of the glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (CHIR) and activin, followed by BMP7, to yield OSR1+ cells with 90% efficiency within 11–18 days of differentiation. OSR1+ cells differentiated into populations expressing markers of mature kidneys, adrenal glands, and gonads in vitro and integrated into dissociated-reaggregated embryonic mouse kidneys.54 The sequential treatment of hPSCs with CHIR, followed by FGF2 and retinoic acid, generated PAX2+LHX1+ IM-like cells with >70% efficiency. PAX2+LHX1+ cells stochastically differentiated to form ciliated tubular structures expressing the proximal tubular markers LTL, N-cadherin, and kidney-specific protein (KSP).6 Meanwhile, directed differentiation of PAX2+LHX1+ cells, involving treatment with FGF9 and activin, generated cells co-expressing markers of MM including SIX2, SALL1, and WT1.6 A similar protocol efficiently generated PAX2+LHX1+ IM cells from hESCs within 6 days, using a combination of CHIR and FGF9.5 On continued FGF9 treatment, these cells gave rise to SIX2+ cells with 10–20% efficiency within 14 days.5 Mixing these cells with dissociated-reaggregated mouse embryonic kidneys resulted in 3-dimensional aggregates of SIX2+ cells containing tubular structures expressing kidney markers such as AQP1, AQP2, JAG1, E-cadherin, WT1, and PAX2.5

While considerable work has been done to differentiate hPSCs into MM, efforts to differentiate hPSCs into cells of the UB lineage have been limited. In a 4 day directed differentiation protocol involving initial treatment with BMP4 and FGF2, followed by retinoic acid, activin, and BMP2, hESCs and hiPSCs formed PAX2+OSR1+WT1+LHX1+ IM-like cells.55 These cells spontaneously upregulated transcripts of the UB markers HOXB7, RET, and GFRA1 within 2 days. Upon co-culture with dissociated-reaggregated embryonic mouse kidneys, these putative UB progenitor-like cells partially integrated into mouse UB tips and trunks.55

Two groups have demonstrated the ability to differentiate hPSCs into 3D kidney organoids containing complex, multi-segmented nephron-like structures.7,8 Treatment of hPSCs with CHIR for 4 days, followed by FGF9 for 3 days, and transfer into 3D suspension culture for up to 20 days generated kidney organoids consisting of nephron-like structures bearing markers of proximal and distal tubules, early loops of Henle, and podocyte-like cells.7 To simulate UB-derived Wnt signaling, a transient 1 hour pulse of CHIR on transfer to suspension culture aided the induction of nephron-like structures. The organoids contained tubular structures expressing markers of collecting ducts, stromal cells expressing markers of the renal interstitium, and endothelial cells, suggesting the presence of a heterogenous mixture of the IM and lateral plate mesoderm.7 More recently, a directed differentiation protocol was found to differentiate both hESCs and hiPSC into SIX2+SALL1+PAX2+WT1+ NPCs that could be induced to form nephron (kidney) organoids in both 2D and 3D culture.8 In a stepwise approach that mirrored vertebrate kidney organogenesis, first T+TBX6+ primitive streak cells were induced with CHIR for 4 days, next WT1+HOXD11+ posterior IM cells were induced with activin, and then SIX2+SALL1+PAX2+WT1+ NPCs were induced using low-dose FGF9 with up to 90% efficiency. Treatment of NPCs with continued FGF9 and a transient CHIR pulse induced PAX8+LHX1+ renal vesicles that spontaneously formed nephron-like structures in 2D culture. Transfer of NPCs into 3D suspension culture resulted in the formation of kidney organoids containing multi-segmented nephron-like structures expressing markers of glomerular podocytes (NPHS1+PODXL+WT1+), proximal tubules (LTL+CDH2+AQP1+), loops of Henle (CDH1+UMOD+), and distal tubules (CHD1+UMOD-) in a contiguous arrangement. Additionally, these kidney organoids demonstrated promise for applications involving studies of kidney development and drug toxicity.

The establishment of efficient protocols for directing the differentiation of hPSCs into NPCs and kidney organoids marks a significant advance in the ongoing effort to apply human stem cells to the regeneration of kidney tissue, modeling of human kidney disease, and drug testing for therapeutic efficacy and toxicity.8,11 However, the development of definitive functional assays and the establishment of reliable genetic markers will be required to verify whether induced hPSC-derived kidney cells and tissues are sufficiently identical to their in vivo complements for translational applications.

Kidney Organoids for Nephrotoxicity Testing

Nephrotoxicity is a common manifestation of the toxic effects of drugs and their metabolites. The kidneys are highly vascularized, receiving 20–25% of the cardiac output, and may accumulate circulating toxins in the vascular, interstitial, tubular, or glomerular spaces. During drug development, 19% of failures in Phase III clinical trials are due to nephrotoxicity.56 As the cost to bring a drug to market is currently ~2.6 billion dollars,57 the availability of high-throughput nephrotoxicity screening systems during drug development may save considerable time and costs.

Recent reports have demonstrated that hPSC-derived kidney cell tissue may respond to nephrotoxic drugs in a manner that mimics in vivo kidney injury.7,8 In the previously discussed protocols to generate hPSC-derived kidney organoids, the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin was demonstrated to cause specific injury to the proximal tubular cells, consistent with known cisplatin toxicity in vivo. Cisplatin-induced proximal tubular injury was characterized by the upregulation of the DNA damage marker γH2AX, increased expression of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), and upregulation of cleaved caspase-3.7,8,10 Additionally, treatment of kidney organoids with the antibiotic gentamicin upregulated KIM-1 in proximal tubules, without any discernible effect on podocytes, consistent with the known nephrotoxicity of aminoglycosides.

Kidney Organoids for Modeling of Kidney Diseases

hiPSC-derived organ tissue represents a valuable platform for the study of human pathophysiology and the discovery of novel therapeutics. As hiPSCs remain isogenic with the original host cell prior to reprogramming, they provide a means of modeling patient-specific genetic diseases. Importantly, the rarity of many genetic diseases precludes enrollment in clinical trials, which coupled with a lack of incentive for drug companies to develop treatments for rare diseases, fuels the hope that hiPSC-based assays can be a scalable and reliable option for pre-clinical studies at low cost. Once established, reliable human disease models may allow for clinical trials-in-a-dish. Human stem cell-based systems may ultimately replace animal testing, known to be poorly predictive of the human response.58 To date, hiPSC lines have been generated for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD),59 autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD),43 and systemic lupus erythematosus.60,61

ADPKD is the most common potentially lethal monogenic disorder, affecting 1 in 600 to 1 in 1000 live births. Approximately 50% of individuals with ADPKD develop end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) by age 60.62 The traditionally used mouse models are homozygous carriers for ADPKD mutations while afflicted humans are heterozygotes, calling into question the utility of ADPKD animal models.63 hiPSC lines have been created from multiple patients with ADPKD and ARPKD.59 A subsequent study from the same group used the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 system to knockout PKD1 or PKD2, the causative genes for ADPKD, in human ESC lines.64 Tubular organoids derived from these PKD1 and PKD2 knockout mutants developed cystic structures from LTL+ kidney tubules, suggesting that this model could potentially serve as a novel means to study cystogenesis in ADPKD and screen for new therapeutics in vitro.

Pluripotent Stem Cells for Bioengineering Kidney Tissue

The shortage of transplantable organs, coupled with the rising prevalence of ESKD, has led researchers to apply regenerative medicine techniques towards kidney bioengineering.65 Human iPSCs serve as a theoretically immunocompatible and scalable cell source, with therapeutic applications for both chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute kidney injury (AKI). While the kidney is a complex organ consisting of >50 distinct cell types that provide for exocrine, endocrine, and metabolic functions, the essential elements of an envisioned bioengineered kidney would include multiple hPSC-derived cell types supported in a perfusable scaffolding that provides appropriate cellular segregation and compartmentalization. Two scaffolding approaches have been undertaken, kidney decellularization and a 3D-printed framework.66,67

Decellularized kidney approaches preserve the extracellular matrix (ECM) of distinct kidney compartments, retaining matrix-associated signals and growth factors, and conserving the vascular tree and branched collecting duct network. Mammalian kidneys have been decellularized, using the detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and the cell membrane toxicant Triton X-100, with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains confirming the removal of cellular material and immunohistochemistry demonstrated the preservation of native ECM.68 Surgically implanted decellularized vertebrate kidneys remain perfusable and lack blood extravasation, but completely thrombose due to denuded ECM.69 Seeding decellularized rat kidneys with rat fetal kidney cells via the ureter, and endothelial cells via the renal artery, enabled the production of a small amount of urine when perfused by the recipient’s circulation following orthotopic transplantation.66 However, the urinary filtrate was negligible and vasculature rapidly thrombosed. Similarly, murine ESCs were seeded into decellularized rat kidneys via the renal artery and ureter.70 Cells lost their pluripotent phenotype, expressed kidney markers, but was limited by small vessel thrombosis on perfusion testing in vivo. Decellularized vasculature ex vivo lined with the biocompatible polymer, poly(1,8-octanediol citrate), and functionalized with heparin reduced platelet adhesion and whole blood clotting.71 Given their advantage of maintained architecture, decellularized kidney approaches may provide a valuable resource in the efforts to create a bioengineered kidney.

Biologic applications of 3D printing have gained notoriety and credibility with the organ-on-a-chip series, modeling lung, gut, the kidney proximal tubule, and bone marrow.72–75 While these early organ chips employ a soft lithography method first published nearly two decades ago,76 recent advances in 3D printing have enabled faithful manufacturing of micrometer scale, multicomponent 3-dimensional structures. However, current commercially available 3D printing resins for both stereolithography and multijet modeling demonstrate poor biocompatibility.77,78 To overcome obstacles of resin cytotoxicity and the need for a vascular network in tissue engineering, the Lewis lab employed biocompatible collagen-based resins to develop vascular networks.79 Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), embedded in a sacrificial Pluronic F127 hydrogel, were printed in channels and surrounded by photocurable gelatin methacrylate. Removal of the fugitive ink yielded tubular channels consisting of a confluent monolayer of HUVECs. Using a similar methodology, the proximal tubule-on-a-chip has evolved from incorporating a cellular monolayer into tubular structures containing a perfusable lumen.67

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 fellowship training grant (DK007527, to N.G.), a Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) Cross-Disciplinary Fellowship Grant (to N.G.), a Brigham and Women’s Hospital Research Excellence Award (to N.G. and R.M.), the Program for Advancing Strategic International Networks to Accelerate the Circulation of Talented Researchers (from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, JSPS, to KS), the Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Fellowship for Research Abroad (to R.M.), a Grant-in-Aid for a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (to R.M.), a ReproCELL Stem Cell Research grant (to R.M.), a Brigham and Women’s Hospital Faculty Career Development Award (to R.M.), a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Seed Grant (to R.M.), AJINOMOTO Co., Inc. (to R.M.), and Toray Industries, Inc. (to R.M.).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: R.M. is a co-inventor on patents (PCT/US16/52350) on organoid technologies that are assigned to Partners Healthcare.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Thomson JA et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–7. Erratum in: Science. 1998;282(5395):1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taguchi A et al. Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(1):53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takasato M et al. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nature cell biology. 2014;16(1):118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam AQ et al. Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(6):1211–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takasato M et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature. 2015;526(7574):564–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.R Morizane at el. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(11):1193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi S et al. Generation of kidney tubular organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morizane R, Bonventre JV. Generation of nephron progenitor cells and kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature protocols. 2017;12(1):195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morizane R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Organoids: A Translational Journey. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(3):246–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vainio S, Lin Y. Coordinating early kidney development: lessons from gene targeting. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(7):533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang M, Han YM. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into nephron progenitor cells in a serum and feeder free system. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morizane R, Lam AQ. Directed Differentiation of Pluripotent Stem Cells into Kidney. Biomark Insights. 2015;10(Suppl 1):147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi A et al. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell stem cell. 2008;3(2):169–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Self M et al. Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 2006;25(21):5214–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertram JF et al. Human nephron number: implications for health and disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26(9):1529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys BD et al. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dressler GR. Advances in early kidney specification, development and patterning. Development. 2009;136(23):3863–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brophy PD et al. Regulation of ureteric bud outgrowth by Pax2-dependent activation of the glial derived neurotrophic factor gene. Development. 2001;128(23):4747–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu PX et al. Eya1-deficient mice lack ears and kidneys and show abnormal apoptosis of organ primordia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(1):113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdelhak S et al. A human homologue of the Drosophila eyes absent gene underlies Branchio-Oto-Renal (BOR) syndrome and identifies a novel gene family. Nat Genet. 1997;15(2):157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi A et al. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005;132(12):2809–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledig S et al. Frame shift mutation of LHX1 is associated with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2872–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James RG et al. Odd-skipped related 1 is required for development of the metanephric kidney and regulates formation and differentiation of kidney precursor cells. Development. 2006;133(15):2995–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreidberg JA et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74(4):679–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natoli TA et al. A mutant form of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene WT1 observed in Denys-Drash syndrome interferes with glomerular capillary development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(8):2058–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grote D et al. Gata3 acts downstream of β-catenin signaling to prevent ectopic metanephric kidney induction. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(12):e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim KC et al. Gata3 loss leads to embryonic lethality due to noradrenaline deficiency of the sympathetic nervous system. Nat Genet. 2000;25(2):209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torban E et al. PAX2 Activates WNT4 Expression during Mammalian Kidney Development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Favor J et al. The mouse Pax21Neu mutation is identical to a human PAX2 mutation in a family with renal-coloboma syndrome and results in developmental defects of the brain, ear, eye, and kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(24):13870–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porteous S et al. Primary renal hypoplasiain humans and mice with PAX2 mutations: evidence of increased apoptosis in fetal kidneys of Pax21Neu +/– mutant mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narlis M et al. Pax2 and Pax8 Regulate Branching Morphogenesis and Nephron Differentiation in the Developing Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishinakamura R et al. Murine homolog of SALL1 is essential for ureteric bud invasion in kidney development. Development. 2001;128(16):3105–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato A et al. Sall1, a causative gene for Townes-Brocks syndrome, enhances the canonical Wnt signaling by localizing to heterochromatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(1):103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore MW et al. Renal and neuronal abnormalities in mice lacking GDNF. Nature. 1996;382(6586):76–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skinner MA et al. Renal Aplasia in Humans Is Associated with RET Mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(2):344–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuchardt A et al. Defects in the kidney and enteric nervous system of mice lacking the tyrosine kinase receptor Ret. Nature. 1994;367(6461):380–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam AQ et al. Directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to kidney cells. Semin Nephrol. 2014;34(4):445–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reijo Pera RA et al. Gene expression profiles of human inner cell mass cells and embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2009;78(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giacomini M et al. Banking on it: public policy and the ethics of stem cell research and development. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1490–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montserrat N et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human renal proximal tubular cells with only two transcription factors, OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(29):24131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song B et al. Generation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from Human Kidney Mesangial Cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1213–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou T et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(12):2080–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou T et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu H et al. Generation of endoderm-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells from primary hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1810–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim JB et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454(7204):646–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staerk J et al. Reprogramming of peripheral blood cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2010;7(1):20–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen DE, Melton D. Turning straw into gold: directing cell fate for regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(4):243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Batchelder CA et al. Renal ontogeny in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) and directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells towards kidney precursors. Differentiation. 2009;78(1):45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin SA et al. Subfractionation of differentiating human embryonic stem cell populations allows the isolation of a mesodermal population enriched for intermediate mesoderm and putative renal progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19(10):1637–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song B et al. The directed differentiation of human iPS cells into kidney podocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Narayanan K et al. Human embryonic stem cells differentiate into functional renal proximal tubular-like cells. Kidney Int. 2013;83(4):593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mae S et al. Monitoring and robust induction of nephrogenic intermediate mesoderm from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Comm. 2013;4:1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia Y et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent cells to ureteric bud kidney progenitor-like cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(12):1507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su R et al. Supervised prediction of drug-induced nephrotoxicity based on interleukin-6 and −8 expression levels. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 16):S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertolini F et al. Drug repurposing in oncology--patient and health systems opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(12):732–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olson H et al. Concordance of the toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and in animals. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;32(1):56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freedman BS et al. Reduced ciliary polycystin-2 in induced pluripotent stem cells from polycystic kidney disease patients with PKD1 mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(10):1571–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thatava T et al. Successful disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell generation from patients with kidney transplantation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;2(6):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y et al. Generation of systemic lupus erythematosus-specific induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iglesias CG et al. Epidemiology of adult polycystic kidney disease, Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1935–1980. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983;2(6):630–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson PD. Mouse models of polycystic kidney disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;84:311–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freedman BS et al. Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bastani B The worsening transplant organ shortage in USA; desperate times demand innovative solutions. J Nephropathol. 2015;4(4):105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song JJ et al. Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):646–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Homan KA et al. Bioprinting of 3D Convoluted Renal Proximal Tubules on Perfusable Chips. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakayama KH et al. Decellularized rhesus monkey kidney as a three-dimensional scaffold for renal tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(7):2207–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orlando G et al. Production and implantation of renal extracellular matrix scaffolds from porcine kidneys as a platform for renal bioengineering investigations. Ann Surg. 2012;256(2):363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ross EA et al. Embryonic stem cells proliferate and differentiate when seeded into kidney scaffolds. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(11):2338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiang B et al. A polymer-extracellular matrix composite with improved thromboresistance and recellularization properties. Acta biomater. 2015;18:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huh D et al. A human disease model of drug toxicity-induced pulmonary edema in a lung-on-a-chip microdevice. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(159):159ra47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim HJ et al. Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinal peristalsis-like motions and flow. Lab Chip. 2012;12(12):2165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jang KJ et al. Human kidney proximal tubule-on-a-chip for drug transport and nephrotoxicity assessment. Integr Biol (Camb). 2013;5(9):1119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torisawa YS et al. Bone marrow-on-a-chip replicates hematopoietic niche physiology in vitro. Nat Methods. 2014;11(6):663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duffy DC et al. Rapid Prototyping of Microfluidic Systems in Poly(dimethylsiloxane). Anal Chem. 1998;70(23):4974–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chia HN, Wu BM. Recent advances in 3D printing of biomaterials. J Biol Eng. 2015;9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macdonald NP et al. Assessment of biocompatibility of 3D printed photopolymers using zebrafish embryo toxicity assays. Lab Chip. 2016;16(2):291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kolesky DB et al. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv Mater. 2014;26(19):3124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]