Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an inherited progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by motor, cognitive, and behavioural changes. One of the earliest changes to occur in HD is a reduction in cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1) levels in the striatum, which is strongly correlated with HD pathogenesis. CB1 positive allosteric modulators (PAM) enhance receptor affinity for, and efficacy of activation by, orthosteric ligands, including the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. The goal of this study was to determine whether the recently characterized CB1 allosteric modulators GAT211 (racemic), GAT228 (R-enantiomer), and GAT229 (S-enantiomer), affected the signs and symptoms of HD. GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 were evaluated in normal and HD cell models, and in a transgenic mouse model of HD (7-week-old male R6/2 mice, 10 mg/kg/d, 21 d, i.p.). GAT229 was a CB1 PAM that improved cell viability in HD cells and improved motor coordination, delayed symptom onset, and normalized gene expression in R6/2 HD mice. GAT228 was an allosteric agonist that did not enhance endocannabinoid signaling or change symptom progression in R6/2 mice. GAT211 displayed intermediate effects between its enantiomers. The compounds used here are not drugs, but probe compounds used to determine the potential utility of CB1 PAMs in HD. Changes in gene expression, and not protein, were quantified in R6/2 HD mice because HD pathogenesis is associated with dysregulation of mRNA levels. The data presented here provide the first proof of principle for the use of CB1 PAMs to treat the signs and symptoms of HD.

Keywords: Cannabinoid, Type 1 Cannabinoid Receptor, Huntington’s disease, Allosteric Modulator, G protein-coupled Receptor, Neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an inherited autosomal dominant disease in which patients suffer from depression, reduced cognition, behavioural changes, and uncontrollable choreiform movements over decades (1). The causative agent of HD, the mutant huntingtin (mHtt) protein, affects the transcription of a subset of genes (2,3). mHtt-dependent transcriptional dysregulation occurs in multiple organ systems, but occurs earliest, and is most-pronounced, in the medium spiny projection neurons of the striatum (2,4). One of the earliest transcriptional changes that occurs in HD is the repression of the type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1) in the striatum, leading to a reduction in CB1 mRNA and protein (5,6). Lower levels of CB1 have been observed in all models of HD studied to date and in patients suffering from HD (7,8).

The decrease in CB1 mRNA and protein observed in HD is strongly correlated with the progression and pathophysiology of HD (9–12). Transgenic R6/2 HD mice that are heterozygous for CB1 (i.e. mHtt x CB1−/+) exhibit earlier HD-like symptom onset, more rapid disease progression, and greater neuronal cell death in the striatum than R6/2 HD mice with a full complement of CB1 (9,13). Rescue of CB1 via adeno-associated viral delivery in medium spiny projection neurons of R6/2 mice prevents loss of excitatory markers such a vGLUT-1, and a decrease in dendritic spine density in the striatum, but does not change motor impairment (10,12). These studies demonstrate that 1) lower levels of CB1 in the striatum and elsewhere appears to contribute to HD pathogenesis, and 2) increasing the abundance and/or activity of CB1 may delay or reduce the severity of the signs and symptoms of HD.

Under non-pathological conditions, CB1 is the most-abundant G protein-coupled receptor in the central nervous system (14–18). We recently reported that Gαi/o-biased CB1 agonists, such as anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), increase CB1 mRNA and protein and improve cell viability in the STHdhQ111/Q111 cell culture model of HD (18). In contrast, the arrestin-biased cannabinoid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) reduces CB1 levels and cell viability in the STHdhQ111/Q111 cell model of HD and increases seizure frequency in R6/1 HD mice (17–19). Increasing AEA levels via fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibition preserves CB1 levels in R6/1 HD mice, but does not affect disease progression (19). Increasing 2-AG levels via inhibition of α/β-hydrolase domain-containing protein 6 (ABHD6) normalizes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in R6/2 HD mice and reduces spontaneous seizure frequency, but does not affect disease progression (12). In addition to transcriptional changes in CB1, other transcript levels are dysregulated in the brain and periphery, including the type 2 cannabinoid receptor (CB2), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor g coactivator 1-α (PGC1α), leptin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (10–13,17,18). Enhancement of CB1 abundance and activity has been shown to normalize expression of these transcripts (10–13,17,18). We hypothesized that compounds capable of increasing the potency and efficacy of endocannabinoid-mediated Gαi/o-dependent CB1 signaling may be an effective means of managing the signs and symptoms of HD while limiting adverse on-target effects associated with psychoactive cannabinoids such as THC.

CB1 positive allosteric modulators (PAM) induce a conformational change in the receptor that enhances the receptor’s affinity for, and efficacy of activation by, orthosteric ligands, such as AEA and 2-AG. CB1 PAMs lack intrinsic efficacy in the absence of an orthosteric ligand, and therefore are unlikely to produce supraphysiological activation, desensitization, or downregulation of CB1 in the absence of an orthosteric ligand (20–22). The goal of the present study was to determine whether the recently characterized CB1 allosteric modulators GAT211 (racemic, equimolar mixture of R- and S-enantiomers) (first described as ‘compound AZ-4’ Astra-Zeneca), and its enantiomers GAT228 (R-enantiomer) and GAT229 (S-enantiomer), affect the severity and progression of HD in cell culture and animal models of the disease (23–27). The data presented in this study provide a first proof of principle for the use of CB1 PAMs to treat the signs and symptoms of HD.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Compounds

GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 were synthesized and provided by the laboratory of Dr. Ganesh Thakur (Northeastern University). 2-AG, AEA, (−)-cis-3-[2-Hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexanol (CP55,940), THC, and cannabidiol (CBD) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Cannabinoids were dissolved in DMSO (final concentration of 0.1% in assay media for all assays) and added directly to the media at the concentrations and times indicated. No effects of vehicle were observed compared to assay media alone.

2.2. Cell culture

Conditionally immortalized wild-type (STHdhQ7/Q7) or homozygous mutant (STHdhQ111Q/111) mouse striatal progenitor cell lines (female karyotype) expressing exon 1 from the human huntingtin allele in the mouse huntingtin locus were acquired from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ) (28,29). Cells were propagated at 33°C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 104 U/mL Pen/Strep, and 400 μg/mL geneticin. For all experiments, cells were serum-starved for 24 h.

2.3. Plasmids

Human CB1-green fluorescent protein2 (GFP2) and arrestin2-Renilla luciferase (Rluc) (βarrestin1) were cloned as fusion proteins at the C-terminus. hCB1-GFP2 was generated using the pGFP2-N3 plasmid (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) as described previously (30). Arrestin2-Rluc was generated using the pcDNA3.1 plasmid (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) as described previously (31). The GFP2-Rluc fusion construct, and Rluc plasmids have also been described (30).

2.4. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer2 (BRET2)

Direct interactions between CB1 and arrestin2 were quantified via BRET (2,32). Cells were transfected with the indicated GFP2 and Rluc constructs using Lipofectamine 2000, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen) and treated as previously described (17,30).

2.5. In-cell™ Westerns

ERK1/2 phosphorylation was quantified via the in-cell™ western assay as described previously (17,30).

2.6. Cell viability assays

Viability assays (calcein-AM [Cal-AM], ethidium homodimer-1 [EthD-1]) were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Live/Dead Cytotoxicity Assay, Life Technologies, Burlington, ON) and as described previously (18).

2.7. Animals

Seven-week-old, male, R6/2 HD mice [strain name B6CBA-Tg(HDexon1)62Gpb/3J bred on a C57BL/6J background] and age-matched, wild-type (C57BL/6J) mice (mean weight 20.3 ± 0.4 g) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were group housed (3–5 per cage) with ad libitum access to food, water, and environmental enrichment and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Mice were randomly assigned to receive volume-matched, daily i.p. injections of vehicle (10% DMSO, 0.1% Tween-20 in saline) or 10 mg/kg/d GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229; 3 mg/kg THC, or 10 mg/kg CBD for 21 days (N = 5 per group). Mice were weighed daily. All protocols were in accordance with the guidelines detailed by the Canadian Council on Animal Care, approved by the Carleton Animal Care Committee at Dalhousie University. In keeping with the ARRIVE guidelines, power analyses were conducted to determine the minimum number of animals required for the study and animals were purchased – rather than bred – to limit animal waste (33). All assessments of animal behaviour were made during the light phase of the diurnal cycle by individuals blinded to treatment group (33). Female mice were not used because no evidence of sex difference was observed in earlier studies (33,34). Genotype analysis was performed for R6/2 HD mice, according to the protocol provided by The Jackson Laboratory, to confirm the presence of the mutant huntingtin transgene and determine the number of CAG repeats (34,35). The mean number of CAG repeats observed in R6/2 mice was 127 ± 4 and was not different between treatment groups. qRT-PCR was conducted to measure the amount of mHtt transcript in R6/2 mouse tissue (35). mHtt transcript levels were not different between vehicle, GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 treatment groups.

2.7.1. Behavioural analyses

Internal body temperature was measured via rectal thermometer prior to the first injection and 24 h after injection every second day. Anti-nociception was determined by assessing tail flick latency prior to the first injection and 24 h after injection every second day. Mice were restrained with the distal 1 cm of the tail placed into 55°C water and the time until the tail was removed was recorded as tail flick latency (sec). Observations were ended at 10 sec. Locomotion was assessed in the open field test prior to the first injection and 24 h after injection every second day. Mice were placed in an open space 90 cm x 60 cm and recorded for 5 min. Data recorded included: total distance travelled over 5 min (m), number of vertical movements, % time spent in the central quadrant of the field, and time spent immobile (sec). Disease progression was assessed prior to the first injection and 24 h after injection every second day. Mice were monitored for eight signs of disease progression in a closed chamber for 30 min every second day for 21 days and for hindlimb clasping by lifting each mouse by its tail for 30 sec (Supplementary Table S1) (36). Individual scores (0, 1, or 2) from each sign (Supplementary Figure S1) were added to calculate ‘sum of behavioural change (/18)’.

2.7.2. DEXA Scan

Upon completion of all drug treatments and behavioural analyses, mice were euthanized with an overdose (100 mg/kg) of sodium pentobarbital (i.p.) followed by exsanguination. Mice were placed in a prostrate position for whole body measurements (excluding head) of total, fat, and lean masses by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry using a Lunar Piximus2 bone densitometer (GE Medical Systems). All scans were subject to daily calibration and were performed by a single user who was blinded to genotype and treatment group.

2.8. Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was harvested from the striatum, cortex, visceral adipose tissue, and whole blood of R6/2 mice and age-matched C57BL/6J littermates using the Trizol® (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) extraction method according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Reverse transcription reactions and qRT-PCR were conducted as described previously (Supplementary Table S2) (37). qRT-PCR data were normalized to the expression of β-actin (13).

2.9. Statistical analyses

Concentration-response curves (CRC) were fit using non-linear regression with variable slope (4 parameters) and used to calculate EC50 and Emax (GraphPad, Prism, v. 5.0). Statistical analyses were conducted by one- or twoway analysis of variance (ANOVA), as indicated in the figure legends. Post-hoc analyses were performed using Tukey’s (one-way ANOVA) or Bonferroni’s (two-way ANOVA) tests. All results are reported as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) or 95% confidence interval (CI), as indicated. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. ERK1/2 phosphorylation and arrestin2 recruitment in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells

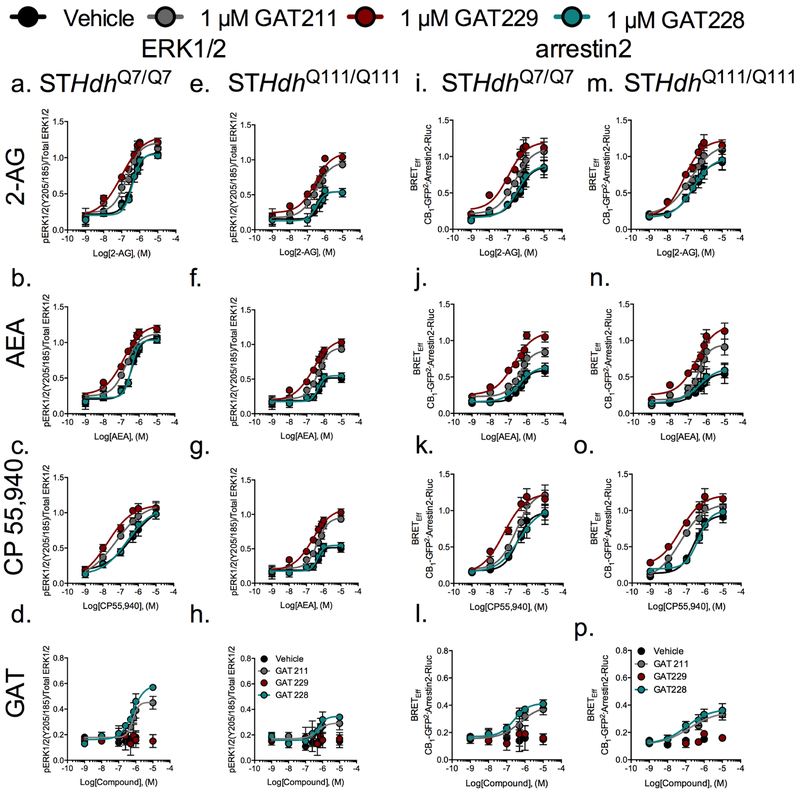

STHdh cells express CB1 at high levels and CB1- and Gαi/o-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK) has been shown to increase the viability of STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (10,13,17,18). CP55,940, and 2-AG and AEA were chosen to investigate pERK, as representative of a high-potency full cannabinoid agonist and the major endocannabinoids, respectively (14,15). GAT229 (S-enantiomer) increased the pEC50 and Emax of 2-AG, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1- and Gαi/o-dependent pERK in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 1A–C,E–G, Table 1). The Emax of pERK1/2 was reduced by approximately 50% in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 cells (18). The pERK Emax was increased 202% in GAT229-treated STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to STHdhQ111/Q111 cells treated with orthosteric agonist alone (Table 1), which was equivalent to a recovery of pERK levels to those observed in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells (Figure 1A–C,E–G). ΔpEC50 was not different between STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells following GAT229 treatment (Table 1). GAT229 displayed probe-dependence because the ΔpEC50, but not Emax, was increased in the presence of CP55,940 more than in the presence of 2-AG or AEA (Table 1). GAT229 did not display intrinsic efficacy in the ERK assay (Figure 1D,H, Table 1).

Figure 1. Characterization of GAT211-, GAT228-, and GAT229-dependent effects on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and arrestin2 recruitment in STHdh cells.

A-H) STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells were treated with 1 nM – 10 μM 2-AG, AEA, CP55,940, GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 ± 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 10 min and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Y185/204) compared to total ERK1/2 levels was determined via In-cell™ western. I-P) STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells were transfected with CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc and treated with 1 nM – 10 μM 2-AG, AEA, CP55,940, GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 ± 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 30 min and BRETEff was determined. CRCs were fit using non-linear regression analysis with variable slope (4 parameter) using Prism (GraphPad v. 5.0). N = 6.

Table 1.

Summary of data for GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells.

| ERK1/2 (Gαi/o) | arrestin2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STHdhQ7/Q7 | STHdQ111/Q111 | STHdhQ7/Q7 | STHdQ111/Q111 | |||||

| ΔpEC50 ± SEMa | Emax ± SEM(%)b | ΔpEC50 ± SEMa | Emax ± SEM(%)b | ΔpEC50 ± SEMa | Emax ± SEM (%)b | ΔpEC50 ± SEMa | Emax ± SEM (%)b | |

| 1 μM GAT229 | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. | N.C. |

| + 2-AG | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 122.37 ± 9.30 | 0.20 ± 0.15*^ | 202.91 ± 9.07*^ | 0.58 ± 0.20 | 139.08 ± 9.95 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | 129.21 ± 6.98 |

| + AEA | 0.47 ± 0.12 | 117.94 ± 6.38 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 211.27 ± 10.90* | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 189.65 ± 8.61† | 0.14 ± 0.19 | 179.83 ± 10.13† |

| + CP 55,940 | 1.36 ± 0.19^† | 100.45 ± 7.86^ | 0.95 ± 0.28† | 194.63 ± 6.44*^ | 0.75 ± 0.26 | 126.98 ± 10.61 | 0.94 0.24† | 129.34 ± 8.06 |

| 1 μM GAT228 | 6.92 ± 0.12 | 58.78 ± 4.92^ | 6.47 ± 0.17 | 34.48 ± 3.93* | 6.60 ± 0.21 | 41.44 ± 3.22 | 6.96 ± 0.46 | 37.04 ± 5.51 |

| + 2-AG | −0.01 ± 0.06 | 98.50 ± 5.01 | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 100.35 ± 4.65 | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 102.21 ± 9.39 | 0.01 ± 0.18 | 103.54 ± 10.13 |

| + AEA | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 97.73 ± 4.84 | 0.04 ± 0.13 | 106.53 ± 4.69 | 0.07 ± 0.14 | 109.47 ± 5.54 | −0.01 ± 0.27 | 111.79 ± 13.02 |

| + CP 55,940 | 0.27 ± 0.33 | 96.85 ± 11.23 | 0.20 ± 0.17 | 103.32 ± 5.33 | −0.07 ± 0.22 | 105.89 ± 12.92 | −0.24 ± 0.10 | 106.54 ± 6.19 |

| 1 μM GAT211 | 6.17 ± 0.10 | 45.29 ± 4.17 | 6.30 ± 0.46 | 29.37 ± 5.69* | 6.26 ± 0.56 | 39.43 ± 9.82 | 6.81 ± 0.49 | 35.36 ± 6.46 |

| + 2-AG | 0.29 ± 0.12 | 113.63 ± 8.61 | 0.15 ± 0.14 | 179.17 ± 8.46*^ | 0.21 ± 0.14 | 128.80 ± 8.98 | 0.18 ± 0.23 | 123.63 ± 13.58 |

| + AEA | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 106.23 ± 7.05 | 0.05 ± 0.09* | 184.82 ± 6.02* | 0.05 ± 0.11 | 147.65 ± 5.87 | 0.03 ± 0.14 | 168.21 ± 9.15† |

| + CP 55,940 | 0.88 ± 0.30^† | 102.52 ± 11.89 | 0.57 ± 0.29† | 157.32 ± 12.07* | 0.07 ± 0.17 | 129.54 ± 11.51 | 0.73 ± 0.27*† | 117.09 ± 9.80 |

pEC50 determined for GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 alone; or determined as the change (Δ) in pEC50 compared to orthosteric agonist alone (1 nM – 10 μM) in the presence of 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229. N.C., not converged.

Emax (%) response compared to Emax for CP 55,940 alone determined for GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 alone or at 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 in the presence of orthosteric agonist.

P < 0.01 compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 cells within assay;

P < 0.01 compared to other orthosteric agonists tested within GAT group;

P < 0.01 compared to arrestin2 (BRETEff) within cell type, as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 6.

GAT228 (R-enantiomer) did not change the pEC50 or Emax of 2-AG, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1- and Gαi/o-dependent pERK1/2 in STHdhQ7/Q7 or STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Fig. 1A–C,E–G, Table 1). pEC50 and Emax were not different between STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells following GAT228 treatment (Table 1). GAT228 alone displayed high nanomolar potency that did not differ between cell types. The efficacy of GAT228 was greater for STHdhQ7/Q7 cells than STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 1D,H, Table 1).

GAT211 (racemic mixture) displayed intermediate activity between its S- and R-enantiomers in the pERK assay. GAT211 increased the pEC50 and Emax of 2-AG, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1- and Gαi/o-dependent pERK1/2 in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells, but less than GAT229 (Figure 1A–C,E–G, Table 1). The pERK Emax was increased 173% in GAT211-treated STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to STHdhQ111/Q111 cells treated with orthosteric agonist alone (Figure 1A–C,E–G, Table 1). ΔpEC50 was lower in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells treated with 1 μM GAT211 + AEA compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 exposed to the same treatment (Table 1). GAT211 displayed similar probe-dependence to GAT229 because the ΔpEC50, but not Emax, was increased in the presence of CP55,940 more than in the presence of 2-AG or AEA (Table 1). Like GAT228, GAT211 alone displayed high nanomolar potency that did not differ between cell types. GAT211 displayed moderate efficacy that was greater for STHdhQ7/Q7 cells than STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 1D,H, Table 1).

Unlike pERK, arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 has been shown to reduce cell viability in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (17,18). GAT229 (S-enantiomer) increased the pEC50 and Emax of 2-AG, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1-dependent arrestin2 recruitment in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 1I–K,M–O, Table 1). No differences in ΔpEC50 or Emax were observed between STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111cells (Table 1). GAT229 displayed probe-dependence because the ΔpEC50 was greater in the presence of CP55,940 than in the presence of 2-AG or AEA in STHdhQ111/Q111cells, and the Emax was greater in the presence of AEA than CP55,940 or 2-AG in STHdhQ111/Q111cells (Table 1). GAT229 did not display intrinsic activity for the arrestin2 assay in STHdhQ7/Q7 or STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 1L,P, Table 1).

GAT228 (R-enantiomer) did not change the pEC50 or Emax of 2-AG-, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1-dependent arrestin2 recruitment (Figure 1I–K,M–O, Table 1). pEC50 and Emax were not different between STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells following GAT228 treatment (Table 1). In the arrestin2 assay, pEC50 and Emax did not differ between cell types treated with GAT228 (Figure 1L,P, Table 1).

GAT211 (racemic mixture) displayed intermediate activity between its S- and R-enantiomers in the arrestin2 assay. GAT211 increased the pEC50 and Emax of 2-AG, AEA- and CP55,940-mediated CB1-dependent arrestin2 recruitment, but less than GAT229 (Figure 1A–C,E–G, Table 1). ΔpEC50 was greater in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells treated with 1 μM GAT211 + CP55,940 compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 exposed to the same treatment (Table 1). GAT211 displayed similar probe-dependence to GAT229 because the ΔpEC50 was increased in the presence of CP55,940 more than in the presence of 2-AG or AEA in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells, and the Emax was greater in the presence of AEA than CP55,940 or 2-AG in STHdhQ111/Q111cells (Table 1). GAT211 displayed lower pEC50 and Emax than GAT228 that did not differ between cell types (Figure 1L,P, Table 1).

Each GAT compound tested differed in potency and efficacy in pERK and arrestin2 assays. For GAT229, the ΔpEC50 was higher and the Emax was lower in the pERK assay compared to the arrestin2 assay in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells treated with CP55,940 (Table 1). In STHdhQ111/Q111 cells treated with GAT229, the ΔpEC50 was lower and the Emax was higher in the pERK assay compared to the arrestin2 assay when 2-AG or CP55,940 (Emax only) were the orthosteric ligands (Table 1). Unlike GAT229, GAT228 displayed agonist activity in the pERK and arrestin2 assays in the absence of orthosteric ligand. Overall, GAT229 behaved as a PAM of 2-AG and AEA-mediated CB1 signaling without having any inherent agonist activity. In contrast, GAT228 had agonist activity, but did not modulate orthosteric agonist activity. GAT211 displayed an intermediate pattern of activity. Importantly, these compounds had the same relative activity in wild-type and mHtt-expressing cells.

3.2. Cell viability assays in STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells

Cells were treated with 100 nM AEA ± 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 and mitochondrial respiration activity (% esterase activity relative to untreated STHdhQ7/Q7 cells) and membrane permeability (% membrane permeability relative to 70% methanol-treated STHdhQ111/Q111 cells) were quantified. Cell viability was lower in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 cells and cell viability was increased following treatment with 100 nM AEA for 18 h (Figure 2A,B). Treatment with 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 18 h did not change cell viability in STHdhQ7/Q7 or STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 2A,B). Treatment with 100 nM AEA + 1 μM GAT211 increased cell viability in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to vehicle-treated STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (Figure 2A,B). GAT228 did not enhance cell viability and may have been antagonistic to AEA-dependent effects (Figure 2A,B). Importantly, treatment with 100 nM AEA + 1 μM GAT229 increased cell viability in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells compared to vehicle- and AEA-treated STHdhQ111/Q111 cells. Therefore, co-treatment with AEA and GAT229 conferred cell-protective effects in the STHdhQ111/Q111 cell culture model of HD that was greater than AEA alone, or GAT211 or GAT228.

Figure 2. GAT211 and GAT229 enhanced the pro-survival effect of AEA in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells.

STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells were treated with vehicle (10% DMSO), 100 nM AEA, 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229, or 100 nM AEA + 1 μM GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 18 h and A) cellular esterase activity was quantified as a measure of cellular viability, or B) membrane permeability to the fluorescent dye EthD-1 was quantified as a measure of cell death, using the Live/Dead Cytotoxicity assay. *P < 0.01 compared to STHdhQ7/Q7 cells within treatment, ^P < 0.01 compared to vehicle treatment within cell type, †P < 0.01 to AEA treatment within cell type, as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 6.

3.3. Assessment of HD-like symptom progression in R6/2 mice

This study used an i.p. dose of 10 mg/kg/d for 21 days of GAT211, GAT228, GAT229, or volume-matched vehicle to initially assess whether CB1 PAMs reduce the signs and symptoms of HD in the R6/2 model of HD. The dose of 10 mg/kg/d was chosen based on previous dose-response experiments by Slivicki et al. in which 10 mg/kg approximates the ED90 for GAT211 in mice (27). A 21 day assessment period was used because the R6/2 mouse is an aggressive model of HD that progresses into a severe disease phenotype between 7–10 weeks of age (34). GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 did not change body temperature or produce an anti-nociceptive effect in the tail flick response assay in wild-type or R6/2 mice following the 21 d treatment period (Supplementary Figure S2A,B). GAT211, GAT228, and to a lesser extent GAT229 each increased the % of time mice spent in the central quadrant of the open field – modelling an anxiolytic effect – consistent with enhanced CB1 signaling in wild-type and R6/2 mice at the end of the 21 d treatment period (Supplementary Figure S2C). No differences in change in body temperature, tail flick response, or time in centre quadrant were observed between wild-type and R6/2 mice (Supplementary Figure S2). In order to compare the effects of the GAT compounds with phytocannabinoids, mice were also treated with THC (3 mg/kg/d) or CBD (10 mg/kg/d). We chose this dose of THC because it has been used previously to stimulate robust cannabimimetic effects (38). We have previously reported that the arrestin2 bias of THC was detrimental to cell viability in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells (27). CBD does not directly activate CB1 but does effect the function of the ECS as a NAM and via non-CB1 targets (25,27). CBD was tested at 10 mg/kg/d because this dose has been used in other animal models of neurological disease (38). THC reduced body temperature, nociception, and anxiety-like behaviour during the treatment period, whereas CBD only reduced anxiety-like behaviour in wild-type mice (Supplementary Figure S3A–C).

The R6/2 mouse model of HD begins to exhibit signs of motor impairment, including hypolocomotion in the open field, at approximately 7 weeks of age (39). Total distance travelled, number of vertical movements, and time spent immobile in the open field were recorded in wild-type and R6/2 mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg/d GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 (Figure 3). Vehicle-treated R6/2 mice displayed less movement compared to vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Figure 3). In wild-type mice, GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 all reduced distance travelled during the 21 d treatment period (Figure 3A–C) and reduced total distance travelled over the whole treatment period (i.e. AUC, Figure 3D). GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 also reduced the number of vertical movements observed in wild-type mice (Figure 3E–G), but only GAT228 and GAT229 reduced total vertical movements (AUC) over the whole treatment period (Figure 3H). In contrast to the treatment effects observed in wild-type mice, GAT-treated R6/2 mice displayed increased total distance travelled (Figure 3A–C), number of vertical movements (Figure 3E–G), total distance travelled during the treatment period (AUC; Figure 3D), and number of vertical movements during the treatment period (AUC; Figure 3H) increased compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice. Total distance travelled and number of vertical movements was significantly lower in GAT228-treated R6/2 mice compared to GAT228-treated wild-type mice (Figure 3A–H). GAT211 and GAT229 did not affect immobility time in wild-type mice (Figure 3I,K). GAT228 increased immobility time in wild-type mice beginning at day 9 and continuing for the duration of the experiment (Figure 3J). GAT211-treated R6/2 mice displayed reduced immobility time (days 7 – 9, 11, 17 – 21) compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 3I); GAT228-treated R6/2 mice displayed reduced immobility time (days 15 – 21) compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 3J); and GAT229-treated R6/2 mice displayed the greatest reduction in immobility time (days 11 – 21) compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 3K). Although vehicle-treated R6/2 mice experience an increase in the total change in immobility time (AUC) compared to wild-type littermates, GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 all reduced total immobility time compared to vehicle treatment in R6/2 mice (Figure 3L). THC treatment did not alter total movement or vertical movement in R6/2 mice compared to vehicle-treated mice, whereas CBD increased total movement between days 5–7) and overall vertical movement (AUC) compared to vehicle-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S3D–I). THC treatment did increase immobility time (days 9, 11, 13; AUC), whereas CBD decreased immobility time on day 21 (Supplementary Figure S3J–L). While GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 each normalized motor activity in R6/2 mice compared to vehicle treatment, GAT229 imparted the most benefit in reducing motor impairment associated with HD and improving motor coordination in the R6/2 mouse model compared to vehicle, GAT211, or GAT228 treatment.

Figure 3. GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 normalized locomotor activity and delayed behavioural changes in R6/2 mice.

Wild-type (C57BL/6J) and R6/2 mice were treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg/d i.p. GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 21 d and measurements of total distance travelled (m), number of vertical movements, and time spent immobile (sec) in open field were made. A–C) Total distance travelled (m) in the open field test over 5 min during the 21 d treatment period. D) Total area under the curve (AUC) for total distance travelled (m) in the open field test for the duration of the treatment period. E–G) Number of vertical movements in the open field test over 5 min during the 21 d treatment period. H) Total AUC for the number of vertical movements in the open field test for the duration of the treatment period. I–K) Time spent immobile (sec) in the open field test over 5 min during the 21 d treatment period. L) Total AUC for immobility time in the open field test for the duration of the treatment period. M–O) Behavioural change (Supplementary Table S1) during the 21 d treatment period. P) Total AUC for behavioural change for the duration of the treatment period. Statistical analyses: A–C,E–G,I–K,M–O) *P < 0.01 R6/2 -vehicle versus R6/2 – GAT compound within day. D,H,I,P) ***P < 0.001 wild-type versus R6/2 within treatment; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, ^^^P < 0.001 compared to vehicle treatment within genotype. Statistical differences determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 5 per group.

HD-like signs and symptoms were evaluated in R6/2 mice (36,40). Vehicle, GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 did not affect any of the assessed measures in wild-type mice (Figure 3M–P; Supplementary Figure S1). The sum of behavioural changes was lower from days 11 – 17 in GAT211-treated R6/2 mice compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 3M), suggesting that symptom progression was delayed by treatment with 10 mg/kg/d GAT211. GAT228 treatment did not change the sum of behavioural changes in R6/2 mice compared to vehicle treatment (Figure 3N). The sum of behavioural changes was lower from days 13 – 21 in GAT229-treated R6/2 mice compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 3O), indicating that symptom progression was delayed by treatment with 10 mg/kg/d GAT229 compared to vehicle and the racemic compound GAT211. GAT211 and GAT229 reduced the total sum of behavioural changes (AUC) compared to vehicle treatment in R6/2 mice (Figure 3P). In contrast to GAT211 and GAT229, THC treatment exacerbated sum behavioural deficits (days 7, 9, 11; AUC), whereas CBD treatment had limited mitigating effects (days 9, 17) (Supplementary Figure S3M–O). As with modulation of locomotor activity, GAT229 conferred the most benefit in delaying the signs and symptoms of HD, and normalizing animal behaviour, in the R6/2 mouse model of HD.

3.4. Body composition in R6/2 HD mice

R6/2 mice, and patients suffering from HD, experience a failure to gain weight and an increase in body fat content at the expense of lean tissue (41–43). Wild-type mice gained 27 ± 1.4% of their initial weight during the 3-week course of the experiment and weight gain did not differ between vehicle-, GAT211-, GAT228-, and GAT229-treated wild-type mice (Figure 4A–D). As expected, vehicle-treated R6/2 mice lost 6.4 ± 0.59% of their initial body weight (Figure 4A–D) (28). GAT211-treated R6/2 mice gained 8.9 ± 5.1% of their initial body weight during the 21 d course of the experiment, showing improved weight gain compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice by day 15, but less weight gain compared to GAT211-treated wild-type mice (Figure 4A,D). GAT228-treated R6/2 mice lost 4.7 ± 6.6% of their initial body weight during the 21 d course of the experiment, which was not different compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 4B,D). GAT229-treated R6/2 mice gained 11 ± 7.9% of their initial body weight during the 21 d course of the experiment, showing improved weight gain compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice by day 18 that was equivalent to the normal weight gain observed in GAT229-treated wild-type mice (Figure 4C,D). R6/2 mice had a higher % fat, and a lower % lean tissue, compared to wild-type mice regardless of treatment, as determined via post-mortem DEXA scan (Figure 4E,F). In addition, GAT228-treated R6/2 mice displayed a greater % fat, and a lower % lean tissue, than vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 4E,F). Neither THC or CBD treatment altered change in weight, % fat, or % lean tissue in wild-type and R6/2 mice (Supplementary Figure S3P–3). Based on these data we concluded that the CB1 PAM GAT229 promoted normal weight gain in R6/2 mice and was neutral with respect to changes in body composition that occur during HD pathogenesis. In contrast, GAT228 was neutral with respect to weight gain in R6/2 mice and exacerbated the increase in body fat and loss of lean mass that occur during HD pathogenesis. As expected, the racemic compound GAT211 displayed effects intermediate effects between its two enantiomers.

Figure 4. GAT211 and GAT229 improved weight gain in R6/2 mice.

A–D) Wild-type (C57BL/6J) and R6/2 mice were treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg/d i.p. GAT211 (A), GAT228 (B), or GAT229 (C) for 21 d and weight was measured 24 h after GAT treatment every day. D) Summary of total change in weight over 21 d duration of the experiment. *P < 0.01 R6/2 treated with GAT compound versus R6/2 treated with vehicle within day as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 5 per group. E,F) DEXA scans of mice were conducted post-mortem to determine the % fat (E) tissue and % lean (F) tissue following the 3 week experiment. *P < 0.01 compared to wild-type within treatment, ^P < 0.01 compared to vehicle within genotype as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 5 per group.

3.5. Gene expression in R6/2 HD mice

Transcriptional dysregulation is a hallmark pathophysiological event in HD for a specific subset of genes (2,3). Transcriptional dysregulation occurring early in HD progression is observed in the central nervous system, is thought to be a direct result of mHtt expression, and is most-pronounced in the striatum (e.g. decreased CB1, PGC1α, and BDNF-2). Transcriptional dysregulation occurring late in HD progression is observed throughout the body and is associated with changes in inflammation (e.g. increased CB2 and cytokines) and metabolism (e.g. increased leptin, decreased PGC1a) (2,3,39,40). Here, our hypothesis was that treatment with CB1 PAMs would reduce and delay HD-like symptom progression in R6/2 mice. We examined transcript levels for message affected directly by mHtt early in HD, late in HD as inflammatory and metabolic changes occur, and additionally we also assessed general changes in the endocannabinoid system.

We investigated whether treatment with GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 altered mRNA levels in the tissues of wild-type and R6/2 mice (43,44). CB1 mRNA levels were lower in the striatum and cortex of vehicle-, GAT211-, and GAT228-treated R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice (Figure 5A,B). CB1 mRNA levels were normalized to wild-type levels in the striatum and cortex of GAT229-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 5A,B). CB1 mRNA levels were higher in the visceral adipose of GAT228-treated R6/2 HD mice compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 mice and GAT228-treated wild-type mice (Figure 5C). CB1 mRNA levels were not different in the whole blood of wild-type and R6/2 mice (Figure 5D). CB2 mRNA levels were higher in the striatum, cortex, visceral adipose, and whole blood of vehicle-, GAT211-, and GAT228-treated R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice (Figure 5E–H). CB2 mRNA levels were normalized to wild-type levels in the striatum, cortex, visceral adipose, and whole blood of GAT229-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 5E–H).

Figure 5. GAT229 normalized gene expression in R6/2 mice.

RNA was collected from the striatum, cortex, visceral adipose tissue, and whole blood of wild-type (C57BL/6J) and R6/2 mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg/d i.p. GAT211, GAT228, or GAT229 for 21 d and converted to cDNA for qRT-PCR measurement of CB1 (A–D), CB2 (E–H), PGC1α (I–K), leptin (L), and BDNF-2 (M,N) relative to β-actin. *P < 0.01 compared to wild-type within treatment, ^P < 0.01 compared to vehicle within genotype as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. N = 5 per group.

FAAH mRNA levels were elevated in the striatum, cortex, and visceral adipose of R6/2 mice compared to wild-type mice; this increase was exacerbated in GAT228-treated R6/2 mice in striatum and cortex and normalized in GAT229-treated R6/2 mice in striatum (Supplementary Table S3). Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) mRNA levels were elevated in the cortex and visceral adipose of R6/2 mice compared to wild-type mice; this increase was normalized in GAT211- and GAT229-treated R6/2 mice in the cortex and visceral adipose (Supplementary Table S3). N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-specific phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) mRNA levels were lower in the striatum and cortex of R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice and not changed by GAT treatment (Supplementary Table S3). Diacylglycerol lipase α (DAGLα) mRNA levels were not changed in any tissue by genotype or GAT treatment (Supplementary Table S3).

mHtt-dependent transcriptional dysregulation of PGC1α, BDNF-2, leptin, interleukin (IL)-1β, and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5) in the brain, adipose, and blood may contribute to HD pathogenesis, and activation of CB1 is known to affect mRNA abundance of these genes in vitro (2,17,41,44–46). PGC1α mRNA levels were lower in the striatum, cortex, and visceral adipose of vehicle-, GAT211-, and GAT229-treated R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice (Figure 6I–K). PGC1α mRNA levels were normalized to wild-type levels in the striatum, cortex, and visceral adipose of GAT229-treated (and GAT211-treated in cortex) R6/2 mice (Figure 5I–K). Leptin mRNA levels were higher in the visceral adipose of vehicle-, GAT211-, and GAT229-treated R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice (Figure 5L). Leptin mRNA levels were normalized to wild-type levels in the visceral adipose of GAT229-treated R6/2 mice, and reduced in GAT211-treated R6/2 mice compared to vehicle-treated R6/2 (Figure 5L). BDNF-2 mRNA levels were lower in the striatum and cortex of vehicle-, GAT211-, and GAT229-treated R6/2 mice compared to treatment-matched wild-type mice (Figure 5M,N). BDNF-2 mRNA levels were normalized to wild-type levels in the striatum and cortex of GAT229-treated R6/2 mice (Figure 5M,N). IL-1β and CCL5 mRNA levels were elevated in the striatum, cortex, and whole blood of R6/2 mice compared to wild-type mice; this increase normalized in GAT211-treated R6/2 mice in cortex and whole blood and in GAT229-treated R6/2 mice in striatum, cortex, and whole blood (Supplementary Table S3). Based on these data, we concluded that GAT229 treatment was associated with normalization of CB1, CB2, FAAH, MAGL, PGC1α, leptin, BDNF-2, IL-1β, and CCL5 mRNA levels in tissues where mHtt is known to affect transcription, whereas GAT228 was either neutral or itself dysregulated gene expression (CB1 in visceral adipose) and GAT211 displayed intermediated effects (2,46).

4. Discussion

In this study, the CB1 allosteric modulators GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 increased viability of cultured medium spiny projection neurons expressing mHtt and improved measures of health in the R6/2 mouse model of HD. Our observations in STHdh cells confirm previous observations made in HEK293A and Neuro2a cells, where GAT229 produced effects consistent with a pure CB1 PAM, GAT228 acted as a CB1 allosteric partial agonist, and GAT211 displayed intermediate effects (25,26). The pharmacological activity of GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 were not affected by mHtt and relative drug effect was similar between STHdhQ7/Q7 and STHdhQ111/Q111 cells.

GAT211 and its enantiomers have previously been shown to have CB1 specificity and their binding is prevented by the CB1 antagonists SR141716A and AM630 (25,27). Whereas a CB1 orthosteric agonist, such as THC, elicits immediate, acute cannabimimetic effects in vivo (47) (Supplementary Figure S3), the allosteric modulators GAT211, GAT228, and GAT229 each elicited behavioural effects only after repeated exposures in wild-type and R6/2 mice. Of note among these was the ability of GAT229, and to a lesser extent GAT211, to increase the abundance of CB1 mRNA and several other transcripts in the brain of R6/2 mice. Based on these data we would anticipate that earlier, pre-symptomatic treatment with CB1 PAMs, or longer-term treatment with these compounds, would produce a re-normalization of CB1 levels and tissue distribution. Because GAT228 is a partial allosteric agonist (25), the cannabimimetic effects observed in GAT228-treated mice may have resulted from direct CB1 activation and not PAM activity. This idea is supported by the observations that GAT228-treated mice were unique among wild-type mice in their immobility. GAT228 may have competed with endogenous cannabinoids for CB1 binding if the two ligand binding sites overlapped (25). Similar to GAT228, the orthosteric partial agonist THC also increased immobility time, whereas CBD – which does not activate CB1 –displayed no cannabimimetic effects. Treatment with the racemic GAT211 is equivalent to 50% treatments with the enantiomers GAT228 and GAT229, with GAT211 producing intermediate effects compared to those of its enantiomers, observed here and previously (25). GAT229-dependent effects may have been the result of: 1) gradual and sustained enhancement of endocannabinoid-mediated CB1 signaling; 2) accumulation of GAT229; or 3) accumulation of a metabolite of GAT229 that in turn affected the endocannabinoid system (47–49). Slivicki et al. recently reported that GAT211 suppresses allodynia following administration of complete Freund’s adjuvant via CB1 (27). Based on their findings, 10 mg/kg approximates the ED90 for GAT211 in mice (27). Slivicki et al. reports that GAT211 does not evoke cannabimimetic effects when administered alone in vivo or impact behaviour in healthy, wild-type mice (27). GAT211 and ZCZ011 both potentiate sub-threshold effects of CB1 agonists (27,48). For the purposes of this study, the chosen dose and treatment paradigm affected the progression of HD-like symptoms in the R6/2 mouse model of HD. Additional studies are required to fully characterize the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of CB1 PAMs (48–50).

Past attempts to enhance CB1-dependent signaling in vivo with various CB1 agonists have met with varied results: HU210 treatment reduces mHtt aggregation but increases seizure frequency in R6/2 mice, inhibition of FAAH reduces striatal atrophy but does not affect motor coordination, and THC treatment exacerbates deteriorating performance in the accelerating rotarod and decreases CB1 binding in the striatum (9–13,19,44,46,51). Based on our understanding of CB1 agonist bias, we hypothesized that enhancement of endocannabinoid-dependent signaling would be expected to produce the greatest benefit, while arrestin-biased agonists – such as THC – would be expected to promote receptor internalization and reduced CB1 binding (8,18,19,51). In accordance with this, the arrestin-biased agonist THC (25,27) exacerbated HD-like symptom progression in R6/2 mice (Supplementary Figure S3M). AEA and 2-AG are Gαi/o-biased agonists (19). In the presence of the CB1 PAM GAT229 this bias is enhanced, which we predict is associated with neuroprotective signaling (19).

In contrast to R6/2 mice, treatment with the GAT compounds reduced locomotor activity in wild-type mice. We hypothesize that this may be the result of different distribution of CB1 in wild-type versus R6/2 mice: activation of the high density of striatal CB1 receptors in wild-type mice results in overall reduced locomotor activity, whereas the relative density of CB1 receptors is shifted away from the striatum to the cortex and substantia nigra in HD mice resulting in increased motor control from cortical neurons projecting to the striatum (52,53). Our observation that GAT treatment brought locomotor activity in wild-type and R6/2 mice to approximately the same level supports this hypothesis.

Failure to gain weight and altered body composition are observed in mouse models of HD and human patients suffering from HD (42,43). Because CB1 activation is known to promote weight gain and enhance adipogenesis, compounds that target CB1 for the treatment of HD must be either neutral or beneficial with respect to the known metabolic dysfunction in HD (54,55). Treatment with GAT229 or GAT211 was associated with weight gain in R6/2 mice and did not affect body composition. GAT228 exacerbated an increase in body fat at the expense of lean tissue in R6/2 mice, suggesting this compound was detrimental in the R6/2 model of HD with respect to metabolism.

Treatment of R6/2 mice with GAT229 normalized the expression of CB1, CB2, PGC1α, BDNF-2, IL-1β, and CCL5 in the striatum, cortex, visceral adipose, and whole blood. Previous data from our group and others have consistently shown an association between activation of CB1, Akt-dependent elevation of BDNF, and reduction in the signs and symptoms of HD in both cell culture and animal models (10,13,45). Activation of CB1 in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells results in an increase in BDNF-2 transcript levels and this increase is dependent upon G protein-dependent activation of ERK1/2 and Akt (44). Subsequent studies, demonstrated that ERK1/2-biased activation of CB1 in STHdhQ111/Q111 cells enhances cell viability (18) and the GAT compounds studied here – specifically GAT211 and GAT229 – do bias CB1 toward ERK1/2-dependent signaling (18,25). In general, ERK1/2-biased ligands are also Akt-biased ligands, relative to arrestin2 (18,25,45). Although GAT-dependent modulation of Akt was not directly assessed in this study, the large amount of data available from our group and others on this topic support the hypothesis that increased Akt and BDNF are associated with reduced signs and symptoms of HD in model systems. Moreover, we found that leptin mRNA levels were normalized in R6/2 mice treated with GAT229. These data support our earlier hypothesis that enhancement of endocannabinoid-mediated, CB1-dependent, signaling normalizes the expression of genes critical to neuroprotection (e.g. BDNF-2, PGC1α), inflammation (e.g. CB2, IL-1β) and energy homeostasis (e.g. PGC1α, leptin) that are dysregulated in HD and may contribute to disease pathophysiology (13,44–46,56).

5. Conclusions

The CB1-selective PAMs used here are probe compounds designed to determine the potential utility of allosteric modulation of CB1 in HD and to define mechanism of action. Importantly, we observed a differential effect in vivo of CB1-selective Gαi/o-biased PAMs reducing HD-like severity in the R6/2 mouse versus the CB1 arrestin2-biased THC exacerbating some signs and symptoms in this model. Drugs based on these probe compounds will need to be developed to optimize pharmacokinetics and bioavailability. This study focused on male R6/2 mice, which are an aggressive form of HD that was chosen to quickly assess the utility of CB1 PAMs in HD. Subsequent analyses of drugs based on the GAT229 probe compound in knock-in models of HD of both sexes where disease progression is more protracted will be required to fully assess the potential of CB1 PAMS for the treatment of HD (37,57,58). This study also focused on chronic treatment of early-symptomatic R6/2 HD mice. It is possible that beginning treatment before symptom onset would be of greater benefit than after these signs have developed (57,58). Tissue analyses described here focused on mRNA levels, rather than protein, because HD is known to be a disease of transcriptional dysregulation. CB1 PAM treatment altered mRNA levels in R6/2 HD mice.

GAT211 and its enantiomer GAT229 are promising lead CB1 PAM compounds because they produce CB1-dependent effects in vivo (20,24,27,57). CB1 PAMs with in vivo efficacy appear to fulfill a key promise of PAMs, namely: reduced psychoactivity and no tolerance or dependence (27,48). In conclusion, positive allosteric modulation of CB1 may be a legitimate means of reducing and delaying the progression of HD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

3 allosteric modulators of CB1R were tested in models of Huntington’s disease

Positive allosteric modulator GAT229 improved cell and mouse viability

Agonist/allosteric modulator GAT228 did not change disease progression in mice

GAT211 (racemic GAT228/GAT229) displayed intermediate effects

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kay Murphy for her assistance with animal behaviour and housing.

Funding: This work was supported by Bridge Funding [Dalhousie University]; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [MOP-97768]; the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [DA027113, EY024717]. Studentships from CIHR, the Huntington Society of Canada (HSC), Killam Trusts, the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (NSHRF), and King AbdulAziz and Dalhousie Universities.

Abbreviations:

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- ABHD6

α/β-hydrolase domain-containing protein 6

- AEA

anandamide

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AUC

area under the curve

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- CB1

type 1 cannabinoid receptor

- CB2

type 2 cannabinoid receptor

- CCL5

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5

- CI

confidence interval; CP55,940, (−)-cis-3-[2-Hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexanol

- CRC

concentration-response curve

- DAGLα

diacylglycerol lipase α

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- IL

interleukin

- MAGL

monoacylglycerol lipase; mHtt, mutant huntingtin protein

- NAPE-PLD

N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-specific phospholipase D

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α

- Rluc

Renilla luciferase

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Shannon KM, Fraint A (2015): Therapeutic advances in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord 30: 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar A, Vaish M, Ratan RR (2014): Transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington’s disease: a failure of adaptive transcriptional homeostasis. Drug Discov Today 19: 956–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valor LM (2015): Transcription, epigenetics and ameliorative strategies in Huntington’s Disease: a genome-wide perspective. Mol Neurobiol 51: 406–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francelle L, Galvan L, Brouillet E (2014): Possible involvement of self-defense mechanisms in the preferential vulnerability of the striatum in Huntington’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci 8: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denovan-Wright EM, Robertson HA (2000): Cannabinoid receptor messenger RNA levels decrease in a subset of neurons of the lateral striatum, cortex and hippocampus of transgenic Huntington’s disease mice. Neuroscience 98: 705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL (2000): The pattern of neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease: a comparative study of cannabinoid, dopamine, adenosine and GABA(A) receptor alterations in the human basal ganglia in Huntington’s disease. Neuroscience 97: 505–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen KL, Waldvogel HJ, Glass M, Faull RL (2009): Cannabinoid (CB(1)), GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptor subunit changes in the globus pallidus in Huntington’s disease. J Chem Neuroanat 37: 266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowie MJ, Bradshaw HB, Howard ML, Nicholson LF, Faull RL, Hannan AJ, et al. (2009): Altered CB1 receptor and endocannabinoid levels precede motor symptom onset in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroscience 163: 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mievis S, Blum D, Ledent C (2011): Worsening of Huntington disease phenotype in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Neurobiol Dis 42: 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarlone A, Bellocchio L, Blázquez C, Resel E, Soria-Gómez E, Cannich A, et al. (2014): A restricted population of CB1 cannabinoid receptors with neuroprotective activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 8257–8262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naydenov AV, Horne EA, Cheah CS, Swinney K, Hsu KL, Cao JK, et al. (2014): ABHD6 blockade exerts antiepileptic activity in PTZ-induced seizures and in spontaneous seizures in R6/2 mice. Neuron 83: 361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naydenov AV, Sepers MD, Swinney K, Raymond LA, Palmiter RD, Stella N (2014): Genetic rescue of CB1 receptors on medium spiny neurons prevents loss of excitatory striatal synapses but not motor impairment in HD mice. Neurobiol Dis 71: 140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blázquez C, Chiarlone A, Sagredo O, Aguado T, Pazos MR, Resel E, et al. (2011): Loss of striatal type 1 cannabinoid receptors is a key pathogenic factor in Huntington’s disease. Brain 134: 119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross RA (2007): Allosterism and cannabinoind CB(1) receptors: the shape of things to come. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pertwee RG (2008): Ligands that target cannabinoid receptors in the brain: from THC to anandamide and beyond. Addict Biol 13: 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piscitelli F, Ligresti A, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Morera L, Allará M, et al. (2012): Indole-2-carboxamides as allosteric modulators of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Med Chem 55: 5627–5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laprairie RB, Bagher AM, Kelly ME, Dupré DJ, Denovan-Wright EM (2014): Type 1 Cannabinoid Receptor Ligands Display Functional Selectivity in a Cell Culture Model of Striatal Medium Spiny Projection Neurons. J Biol Chem 289: 24845–24862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laprairie RB, Bagher AM, Kelly ME, Denovan-Wright EM (2016): Biased type 1 cannabinoid receptor signaling influences neuronal viability in a cell culture model of Huntington disease. Mol Pharmacol 89: 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowie MJ, Howard ML, Nicholson LF, Faull RL, Hannan AJ, Glass M (2010): Behavioural and molecular consequences of chronic cannabinoid treatment in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Neuroscience 170: 324–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamage TF, Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Wiley JL, Abdelrahman M, Trembleau L, Greig IR, et al. (2014): In-vivo pharmacological evaluation of the CB1-receptor allosteric modulator Org-27569. Behav Pharmacol 25: 182–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wootten D, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM (2013): Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12: 630–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Congreve M, Oswald C, Marshall FH (2017): Applying structure-based drug design approaches to allosteric modulators of GPCRs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38: 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adam L, Salois D, Rihakova L, Lapointe S, St-Onge S, Labrecque J, et al. (2007): Positive allosteric modulators of CB1 receptors. Symposium on the Cannabinoids. Burlington, VT, USA. International Cannabinoid Research Society: 86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cairns EA, Szczesniak AM, Straiker AJ, Kulkarni PM, Pertwee RG, Thakur GA, et al. (2017): The in vivo effects of the CB1-positive allosteric modulator GAT229 on intraocular pressure in ocular normotensive and hypertensive mice. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 33: 582–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laprairie RB, Kulkarni PM, Deschamps JR, Kelly MEM, Janero DR, Cascio MG, et al. (2017): Enantiospecific allosteric modulation of cannabinoid 1 receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 8: 1188–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitjavila J, Yin D, Kulkarni PM, Zanato C, Thakur GA, Ross R, et al. (2017): Enantiomer-specific positive allosteric modulation of CB1 signaling in autaptic hippocampal neurons. Pharmacol Res 129: 475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slivicki RA, Xu Z, Kulkarni PM, Pertwee RG, Mackie K, Thakur GA, et al. (2017): Positive allosteric modulation of cannabinoid receptor type 1suppresses pathological pain without producing tolerance or dependence. Biol Psych 8: 31761–31764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trettel F, Rigamonti D, Hilditch-Maguire P, Wheeler VC, Sharp AH, Persichetti F, et al. (2000): Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh (Q111) striatal cells. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2799–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer E, Walter C, Weber JJ, Krahl AC, Mau-Holzmann UA, Rischert N, et al. (2017): Reduced cell size, chromosomal aberration and altered proliferation rates are characteristics and confounding factors in the STHdh cell model of Huntington disease. Sci Rep 7: 16880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagher AM, Laprairie RB, Kelly MEM, Denovan-Wright EM (2013): Co-expression of the human cannabinoid receptor coding region splice variants (hCB1) affects the function of hCB1 receptor complexes. Eur J Pharmacol 721: 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laprairie RB, Bagher AM, Kelly ME, Denovan-Wright EM (2015): Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the type 1 cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 172: 4790–4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James JR, Oliveira MI, Carmo AM, Iaboni A, Davis SJ (2006): A rigorous experimental framework for detecting protein oligomerization using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat Methods 3: 1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010): Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 8: e1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menalled BF, El-Khodor BF, Patry M, Suárez-Fariñas M, Oresnstein SJ, Zahasky B, et al. (2009): Systematic behavioral evaluation of Huntington’s disease transgenic and knock-in mouse models. Neurobiol Dis 35:319–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangiarini SK, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C et al. (1996): Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell 87: 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denovan-Wright EM, Attis M, Rodriguez-Lebron E, Mendel RJ (2008): Sustained striatal ciliary neurotrophic factor expression negatively affects behavior and gene expression in normal and R6/1 mice. J Neurosci Res 86: 1748–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laprairie RB, Warford JR, Hutchings S, Robertson GS, Kelly ME, Denovan-Wright EM (2014): The cytokine and endocannabinoid systems are co-regulated by NF-κB p65/RelA in cell culture and transgenic mouse models of Huntington’s disease and in striatal tissue from Huntington’s disease patients. J Neuroimmunol 267: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiley JL, Burston JJ, Leggett DC, Alekseeva OO, Razdan RK, Mahadevan A et al. (2009): CB1 cannabinoid receptor-mediated modulation of food intake in mice. Br J Pharmacol 145: 293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks SP, Dunnett SP (2015): Mouse models of Huntington’s disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 22: 101–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Lebron E, Denovan-Wright EM, Nash K, Lewin AS, Mandel RJ (2005): Intrastriatal rAAV-mediated delivery of anti-huntingtin shRNAs induces partial reversal of disease progression in R6/1 Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Mol Ther 12: 618–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fain JN, Del Mar NA, Meade CA, Reiner A, Goldowitz D (2001): Abnormalities in the functioning of adipocytes from R6/2 mice that are transgenic for the Huntington’s disease mutation. Hum Mol Genet 10: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phan J, Hickey MA, Zhang P, Chesselet MF, Reue K (2009): Adipose tissue dysfunction tracks disease progression in two Huntington’s disease mouse models. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1006–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malejko K, Weydt P, Süßmuth SD, Grön G, Landwehrmeyer BG, Abler B (2014): Prodromal Huntington disease as a model for functional compensation of early neurodegeneration. PLoS One 9: e114569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laprairie RB, Kelly MEM, Denovan-Wright EM (2013): Cannabinoids increase type 1 cannabinoid receptor expression in a cell culture model of striatal neurons: Implications for Huntington’s disease. Neuropharmacol 72: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blázquez C, Chiarlone A, Bellocchio L, Resel E, Pruunsild P, García-Rincón D (2015): The CB1 cannabinoid receptor signals striatal neuroprotection via a PI3K/Akt/mTORC1/BDNF pathway. Cell Death Differ 22: 1618–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosier B, Muccioli GG, Hermans E, Lambert DM (2010): Functionally selective cannabinoid receptor signalling: therapeutic implications and opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol 80: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long JZ, Li W, Booker L, Burston JJ, Kinsey SG, Schlosburg JE, et al. (2009): Selective blockade of 2-arachidonylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol 5: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Baillie GL, Kinsey S, Crowe M, Ghosh S, Owens RA (2015): A Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor-Positive Allosteric Modulator Reduces Neuropathic Pain in the Mouse with No Psychoactive Effects. Neuropsychopharmacol 40: 2948–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pamplona FA, Ferreira J, Menezes de Lima O Jr, Duarte FS, Bento AF, Forner S, et al. (2012): Anti-inflammatory lipoxin A4 is an endogenous allosteric enhancer of CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 21134–21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khajehali E, Malone DT, Glass M, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Leach K (2015): Biased agonism and biased allosteric modulation at the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Mol Pharmacol 88: 368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiodi V, Uchigashima M, Beggiato S, Ferrante A, Armida M, Martire A, et al. (2012): Unbalance of CB1 receptors expressed in GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 45: 983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horne EA, Coy J, Swinney K, Fung S, Cherry AE, Marrs WR, et al. (2013): Downregulation of cannabinoid receptor 1 from neuropeptide Y interneurons in the basal ganglia of patients with Huntington’s disease and mouse models. Eur J Neurosci 37: 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardinal P, Bellocchio L, Clark S, Cannich A, Klugmann M, Lutz B, et al. (2012): Hypothalamic CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate energy balance in mice. Endocrinol 153:4136–4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cluny NL, Reimer RA, Sharkey KA (2012): Cannabinoid signalling regulates inflammation and energy balance: the importance of the brain-gut axis. Brain Behav Immun 26: 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cui L, Jeong H, Borovecki F, Parkhurst CN, Tanese N, Krainc D (2006): Transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha by mutant huntingtin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Cell 127: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gamage TF, Farquhar CE, Lefever TW, Thomas BF, Nguyen T, Zhang Y, et al. (2017): The great divide: separation between in vitro and in vivo effects of PSNCBAM-1-based CB1 receptor allosteric modulators. Neuropharmacol 125: 365–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Menalled AE, Kudwa AE, Oakeshott S, Farrar A, Paterson N, Filippov I, et al. (2014): Genetic deletion of transglutaminase 2 does not rescue the phenotypic deficits observed in R6/2 and zQ175 mouse models of Huntington’s disease. PLoS One 9: e99520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menalled L, Brunner D (2015): Animal models of Huntington’s disease for translation to clinic: best practices. Mov Disord 29: 1375–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.