Abstract

Reference intervals are relied upon by clinicians when interpreting their patients’ test results. Therefore, laboratorians directly contribute to patient care when they report accurate reference intervals. The traditional approach to establishing reference intervals is to perform a study on healthy volunteers. However, the practical aspects of the staff time and cost required to perform these studies make this approach difficult for clinical laboratories to routinely use. Indirect methods for deriving reference intervals, which utilise patient results stored in the laboratory’s database, provide an alternative approach that is quick and inexpensive to perform. Additionally, because large amounts of patient data can be used, the approach can provide more detailed reference interval information when multiple partitions are required, such as with different age-groups.

However, if the indirect approach is to be used to derive accurate reference intervals, several considerations need to be addressed. The laboratorian must assess whether the assay and patient population were stable over the study period, whether data ‘clean-up’ steps should be used prior to data analysis and, often, how the distribution of values from healthy individuals should be modelled. The assumptions and potential pitfalls of the particular indirect technique chosen for data analysis also need to be considered. A comprehensive understanding of all aspects of the indirect approach to establishing reference intervals allows the laboratorian to harness the power of the data stored in their laboratory database and ensure the reference intervals they report are accurate.

Introduction

The reference intervals reported by laboratories are relied upon by clinicians for the interpretation of their patients’ test results. It is therefore essential that laboratorians use all the tools at their disposal to ensure that the reference intervals that appear on reports are as accurate as possible. Modern laboratory databases are a valuable resource for the setting of reference intervals. Drawing on this resource is particularly helpful when practical constraints make performing a traditional reference interval study difficult or impossible.

Indirect methods do need to be applied with caution to ensure accurate reference intervals are established. General considerations include whether the assay performance and characteristics of the study population were stable over the study period and whether data ‘pre-processing’ techniques should be used to clean up the data. It is also essential to consider whether the assumptions of the indirect method used have been met. Many methods assume that the distribution of values from healthy subjects is near-Gaussian. It is therefore necessary to consider whether this assumption is valid and, if not, whether using a mathematical transform will allow a Gaussian model to apply.

This review will cover some of the more well-known indirect techniques as illustrations of the general approaches that may be taken. Appreciation of the methods used will help laboratorians critically appraise the published work of others and, moreover, provide tools to assist them setting reference intervals using on their own patient data.

Direct Versus Indirect Reference Intervals

The traditional approach to establishing reference intervals involves recruiting healthy subjects into a study in which samples are collected for the sole purpose of defining the reference interval. This approach is known as a ‘direct sampling’ technique.1 Direct reference interval studies may be further categorised on the basis of when exclusion criteria are applied. A priori sampling is when the exclusion and partitioning criteria are applied before the selection of the reference individuals, while a posteriori sampling is when these criteria are applied after testing is performed. A priori sampling is the commonest approach. It may be used for well-established analytes for which the confounding factors and sources of variation are known. A posteriori sampling is necessary, however, for new tests where little is known about the sources of variation.2

In contrast, indirect sampling techniques make use of results in a database established for purposes other than deriving a reference interval.2 Results from routine clinical pathology testing stored in laboratory databases are most often used. The indirect approach has significant practical advantages over traditional reference interval studies. Most notably, the indirect approach is considerably less time-consuming and costly to perform than a direct reference interval study. The costs of performing a direct reference interval study include staff time in identifying and consenting willing subjects as well as the costs associated with sample collection, handling, transport and analysis. In contrast, the only costs associated with performing an indirect reference interval study are associated with the staff time for data extraction and analysis. Furthermore, the direct approach quickly becomes impractical if multiple partitions are necessary because of the requirement for a minimum of 120 subjects in each partition.2 Hence if partitioning adults by decade of age from 20 to 80+ years, a minimum of 840 subjects is required. If partitioning by sex is additionally performed, then a minimum of 1680 subjects is necessary.

Indirect approaches may also be valuable when a significant proportion of the general population requires exclusion. For instance, to examine parathyroid hormone (PTH) reference intervals in subjects 75 years and older in Australia, it would be necessary to exclude 42% with chronic kidney disease3 and 66% with vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency.4 Therefore, to obtain 120 subjects after these exclusion criteria are applied, one would need to recruit over 625 subjects into the study. Indeed, PTH provides an illustration of how an overly-narrow focus on using a direct approach may hamper progress in establishing accurate reference intervals. When investigating PTH reference intervals, not only is there a high rate of exclusion but, as levels increase independently with age, there is a desire to define reference intervals in multiple age partitions across the lifespan.5 In 2002, an International Workshop on Asymptomatic Hyperparathyroidism highlighted the need for further research into establishing accurate PTH reference intervals, which encouraged multiple groups to attempt direct reference interval studies.6–9 Subsequent workshops reviewed these studies and concluded that they were inadequate,10,11 demonstrating the impracticality of enrolling adequate numbers of subjects into multiple age partitions for a rigorous direct PTH reference interval study.

An additional advantage of reference intervals generated by an indirect approach is that they reflect routine laboratory operating conditions. In contrast, direct studies may be conducted under ideal pre-analytical and analytical conditions that are difficult, or impossible, to replicate in routine practice. Finally, there are also ethical advantages to the indirect approach, as participants are not subjected to venesection solely for a reference interval study and the approach avoids the dilemmas that occur in direct studies when apparently healthy subjects have extreme results.

A recent publication from the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits (C-RIDL) gives more detail on the relative merits of direct and indirect approaches.1 This current review considers existing approaches for estimation of indirect reference intervals and extends on the C-RIDL publication by providing more details on the performance of the various approaches.

Datasets and Categorisation of Indirect Methods

Multiple methods for establishing reference intervals by the indirect approach have been published. The methods have not only been used as they were initially described, but also modified or used in combination. In the broadest terms, the methods may be categorised by the level at which the health-related data is separated: at the level of the subject or the level of the result (or, more specifically, the distribution of results). The first category of methods identifies individuals who are presumed to be relatively healthy, for instance by selecting only subjects undergoing periodic health surveillance (Table 1). The second category of methods is designed to be applied to datasets that contain values from both healthy subjects and those with disease; such datasets may be referred to as ‘mixed’. These methods aim to separate out the distribution of values from healthy individuals from the mixed dataset, for example, by using statistical techniques to identify a central Gaussian distribution. Currently methods applied to mixed datasets are used more frequently than those identifying presumed healthy individuals.

Table 1.

Indirect methods for establishing reference intervals that obtain a dataset from presumed healthy individuals.

|

Special Considerations for Indirect Reference Intervals

Assay and Population Stability

The accurate and stable performance of the assay used is an important consideration for all reference interval studies. However, this requires special attention for indirect reference interval studies because of the extended time-period over which the testing usually occurs. Similarly, it is important to review whether the characteristics of the population tested, and the pre-analytical processes used, were consistent throughout the study period.

Analytical performance may be assessed by reviewing the results of internal quality control and external quality assurance testing over the study period. Review of the median patient result across time is another useful tool, for example monthly medians may be reviewed. This may allow identification of analytical shifts, changes in the characteristics of the patient population or variations in pre-analytical processes. They may additionally allow identification of seasonal influences on analyte concentration, as has been observed for bone turnover markers in European populations, for instance.12

Data Pre-Processing

When an indirect approach is used, the investigator may take steps to limit the number of subjects with disease included in a dataset. While this is not essential for methods designed for use on mixed datasets, many investigators using these techniques still choose to perform one or more pre-processing steps to help ‘clean up’ the data.

The exclusion of extreme values is a common step taken. This may simply involve excluding values beyond an arbitrary limit, such as those more than 10 times the upper reference limit13 or involve a statistical test, such as that of Tukey, or others.14–16

Another data pre-processing step that may be used is the exclusion of data from particular referral sites where there is a high likelihood that the patients have significant disease, such as intensive care units and oncology departments.13,17 It may also be appropriate to exclude data from additional referral sites depending on the analyte of interest, for example lipid and renal clinics. Indeed, if it is possible, excluding data from all referral sites other than primary care will lower the risk of data from subjects with disease affecting the results of the study.

Authors also frequently exclude repeat results, so that each patient only contributes one result to the dataset.18,19 Some investigators have gone further and excluded all data from subjects who had more than one episode of testing for the analyte of interest during the study period.20 This approach assumes that subjects who have multiple episodes of testing are more likely to have disease.

Modelling the Distribution of Values in Healthy Subjects

Most of the indirect methods that are applied to mixed datasets assume that values from healthy populations fit a near-Gaussian distribution. Biochemical data never truly have a Gaussian distribution because the analytical standard deviation (SD) is not constant in the measurement interval. Oftentimes, however, measurands show gross deviation from this model with significant skewing. Several causes may be responsible for skewed distributions. Firstly, it may be that the distribution of values from truly healthy individuals is approximately Gaussian and that the skewing is due to the presence of subjects with disease in the dataset. Secondly, a skewed distribution may result from the overlapping of different subgroups, each with a Gaussian distribution but with different means, as may occur with different age-groups. Lastly, it may be that the distribution of values in healthy individuals is genuinely skewed.

It is therefore vital to gather as much information as possible about the distribution of values in healthy populations prior to using an indirect method on a mixed dataset. Ideally, this would involve review of independent data from large published studies. In some circumstances, it may also be possible to identify a subset of individuals who are likely to be healthy from among the extracted data, such as those being tested as part of periodic health screening and use these values to give insight into the expected distribution in health.13 The dataset extracted should also be examined for the presence of any subgroups that require partitioning.

If it is determined that transforming the data to a Gaussian distribution is appropriate, a suitable transformation needs to be selected. Log transforms are commonly used. They are appropriate for positively (right) skewed data that fits the lognormal model.21 However a power-normal, or ‘Box-Cox’, transformation is a more general approach that is superior for some analytes. This transform is favoured by the IFCC and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).1,2 The Box-Cox transformation is defined by the function:

where yλ is the transformed value, x is the original value, and λ is the transformation value.22

Care needs to be exercised in ensuring that the transformation parameters used are suitable. In particular, one wants to avoid ‘over-transforming’ the data such that values from subjects with disease are incorporated into a Gaussian distribution along with values from healthy subjects. Such a scenario may occur if the underlying distribution of values from healthy subjects is skewed, but the skewedness is increased by the presence of subjects with disease. This type of problem may be encountered for instance when examining transaminase reference intervals in populations where non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is highly prevalent.23 Again, use of independent information regarding the expected degree of skewedness in healthy populations is valuable in avoiding this pitfall.

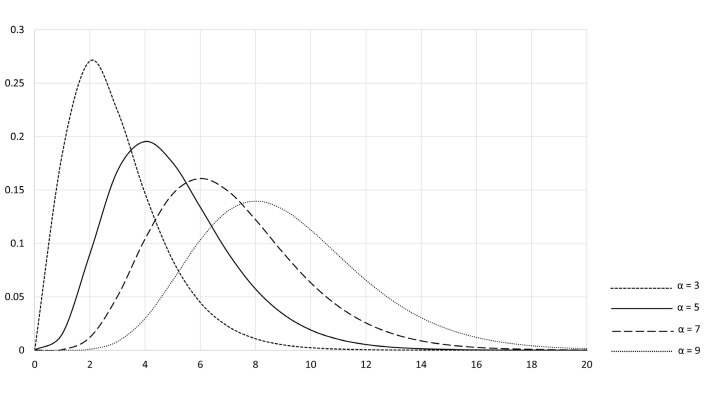

Some indirect approaches allow the values from healthy individuals to be modelled by non-Gaussian distributions. In particular, a modification of the Bhattacharya method (discussed later) utilises gamma distributions. Rather than being a single distribution, these are a family of distributions used to model positively skewed data. Each gamma distribution is described by two parameters, one determining the shape of the distribution (α) and the other having the effect of stretching or compressing the distribution (β)24 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Standard gamma distributions. The shape and scale of the gamma distributions may be ‘parameterised’ in several ways. Here α – shape parameter and β – scale parameter. The standard gamma distributions are those where β = 1.

Methods that Obtain a Dataset from Presumed Healthy Individuals

The most straightforward indirect approach to defining reference intervals, from a theoretical standpoint, is to use results from presumed healthy subjects generated for reasons other than a reference interval study. Once such a dataset is obtained, simple non-parametric statistics can be applied to define the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles as is done in the direct approach. The challenge of this strategy lies in the practicalities of obtaining a dataset from individuals that can be presumed to be relatively healthy. This may be approached in one of two general ways: either data from presumed healthy subjects is extracted, or unselected data is extracted but subjects with disease are subsequently identified and excluded.

Results from Presumed Healthy Individuals Extracted

The indirect method preferred by the CLSI is to extract results from presumed healthy subjects. To achieve this, the CLSI recommends using data from the populations listed in Table 1 (Group A).2 The advantage of this approach is that the subjects used approximate a reference population. However, the approach has practical limitations in that the patient groups recommended are often difficult to identify in a laboratory database, the number of subjects may be small, and there may be a limited range of tests requested on these patients.

Most investigators do not have access to adequately-sized datasets from these populations. Nevertheless, many see the advantage of extracting data from as healthy a population as possible prior to using other indirect techniques. Examples include extracting data from the databases of private pathology providers primarily servicing general practitioners18 or, even more specifically, from patients attending practices focused on ‘wellness checks’.20 Another strategy focuses on the tests requested, limiting the data to only that from subjects in whom ‘basic’ biochemistry tests are requested.20 For instance, an indirect TSH reference interval study only used data from subjects in whom TSH was the sole thyroid function test requested, as opposed to requests which included FT4, FT3, or thyroid antibodies.18

Subjects with Disease Excluded from the Extracted Data

The second approach to obtaining a dataset from relatively healthy subjects is to extract an unselected population and then use techniques to identify and exclude subjects with disease from the dataset. Techniques have identified subjects with disease using known diagnoses or abnormalities in other laboratory results (Table 1, Group B). Currently this approach is not often used, but as database linkage and machine learning becomes more widespread, the approach may become more frequent.

In instances where this approach has been taken, investigators often use known diagnoses to exclude subjects. Approaches vary in how the diagnostic information is obtained and how decisions regarding which diagnoses to exclude are made. Diagnostic information may be most simply obtained from the pathology request form. Notes regarding the medications prescribed to the patient may also indicate particular diagnoses.18 However, the clinical information provided on pathology request forms is notoriously limited, if provided at all. Therefore, accessing databases that contain diagnostic information is generally required. For laboratories associated with a hospital, the hospital’s database may be used.25 Other databases may also be used, depending on the analyte being investigated and the nature of the local health service. For instance, in the NHS region of Tayside, Scotland, investigators examining TSH reference intervals were able to link the databases of the hospital network, community pharmacies and nuclear medicine service to the pathology database. This allowed thorough identification of patients known to have thyroid disorders, those using medications affecting thyroid function, as well as those who had received radioactive iodine treatment.26

Once a dataset containing known patient diagnoses is compiled, it needs to be decided which disorders to exclude from the dataset. This is often done by expert opinion. However, the approach could miss relevant disorders if a pathophysiological link to the analyte of interest is yet to be established. Moreover, the approach is generally labour-intensive. For example, an indirect reference interval study of red cell parameters required a haematologist to review discharge diagnosis codes in a hospital database and compile a list of ‘several hundred’ of these that could possibly affect red cell parameters.25

An alternative approach to determining which conditions to exclude is to use machine learning. This was done by the Laboratory Mining for Individualized Threshold (LIMIT) study, which used an unsupervised machine learning algorithm to identify diagnostic codes that were significantly associated with outlier results for the analyte of interest.14 The ‘learning’ component of the algorithm involved setting values for 4 parameters (one of which, for instance, governed the sensitivity to outlier detection). These values were set using data for serum sodium because of its well-established reference interval. The algorithm derived a reference interval for blood haemoglobin that was comparable with an interval derived by expert-based exclusion. It also derived a reference interval for serum potassium that was consistent with the harmonised reference interval.

Subjects with disease may alternatively be identified on the basis of abnormalities of other laboratory tests. Again, expert opinion may be used to decide which tests are relevant. This approach will rely on known physiology and well-established relationships between analytes. For instance, an investigation into PTH reference intervals which excluded subjects with abnormal albumin-adjusted serum calcium, estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D less than 75 nmol/L found that the observed 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for the entire cohort (1.4–12.3 pmol/L), matched the reference interval derived using the more sophisticated statistical approach of Bhattacharya analysis (1.8–12.2 pmol/L).27 Rather than use expert opinion, some investigators have instead looked for statistical associations between test results. For instance, the REALAB collaboration used a multivariate algorithm to identify correlations between results of numerous tests.20

All subjects who had an abnormal result for any test which had shown a correlation with the analyte of interest were then excluded prior to establishing the reference interval. An intriguing report has suggested that the time interval between repeat tests provides an index of how abnormal clinicians consider the initial result. Specifically, it was observed that the time interval between a result being reported and the clinician requesting a repeat test decreased as the initial result varied away from the midpoint of the reference interval, with no threshold effect.28 An interesting approach for future development would be statistically evaluating time interval data on repeat testing to define reference intervals using this parameter alone.

Techniques that are Applied to a Mixed Dataset

A range of techniques have been described that are designed to identify the distribution of health-related values from amongst a mixed dataset. These techniques require that most of the values from subjects with disease do not lie too close to the mean of results from healthy subjects.29 Furthermore, the nature of the distribution of values from healthy subjects needs to be understood. Almost all techniques assume that the results from healthy subjects follow a near-Gaussian distribution. If an analyte does not show a near-Gaussian distribution, a transform can be applied to the data. By assuming a near-Gaussian distribution, these techniques reduce the problem of finding a reference interval to a problem of finding the mean and SD of values from healthy subjects. Once these parameters are determined, the calculation of the reference interval is trivial: mean ± 1.96 × SD.

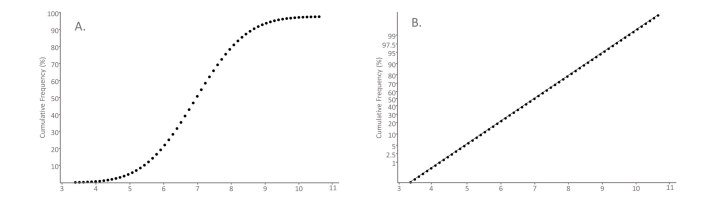

Hoffmann Method

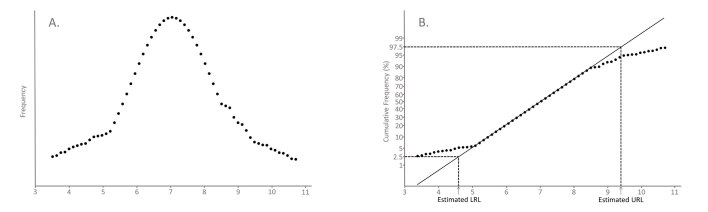

The Hoffmann method, described in 1963, is a graphical method that utilises special scaling of the y-axis of a cumulative frequency plot to identify a central Gaussian component in a dataset.30 For Gaussian distributions, the cumulative frequency will have a sigmoidal shape if a linear scale is used for the x- and y-axes (Figure 2A). Instead Hoffmann’s approach is to plot the cumulative frequency on ‘normal probability paper’, which has a non-linear scale for the y-axis that is designed so a plot of cumulative frequency of a Gaussian distribution will give a straight line (Figure 2B). In Hoffmann’s method, when the Gaussian component is visualised, a straight line is drawn through this part of the curve by eye with greatest weight given to fitting points around the 50% point on the graph. The line is extrapolated to the points on the graph where y = 2.5% and y = 97.5% and the corresponding x-values at these points represent the lower and upper reference limits (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Graphical representations of a cumulative Gaussian distribution. The cumulative percentage of observations (y-axis) of a dataset is graphed as a function of the value (x-axis). (A) Cumulative frequency plot: Data from a Gaussian distribution is plotted with both axes having a standard linear scale. The resulting graph is sigmoidal-shaped. (B) Normal probability plot: The y-axis has a non-linear scale designed so that the cumulative frequency of Gaussian data appears as a straight line.

Figure 3.

Illustration of Hoffmann’s method. A hypothetical mixed dataset is plotted in two ways. (A) Frequency plot: The dataset is seen to follow a Gaussian distribution with distortion in the tails. (B) Normal probability plot: In Hoffmann’s method a line of best fit of the central Gaussian component is drawn. The lower reference limit (LRL) and the upper reference limit (URL) are estimated from the x-values corresponding to y = 2.5% and y = 97.5%, respectively, along this line of best fit. This is the basis of Hoffmann’s original method.

A number of variants of the Hoffmann method have been described. Neumann, for instance, proposed an iterative truncation variation, which he described as ‘dissecting’ out the healthy population.31

It is important for the laboratorian to be aware that a number of recent publications have used a flawed variant of Hoffmann’s method that uses a linear scale for the y-axis rather than a normal probability plot.16,32–34 This approach undermines the theoretical basis of the method and leads to inaccurate reference interval estimates, with the interval generally being overly narrow.34–36

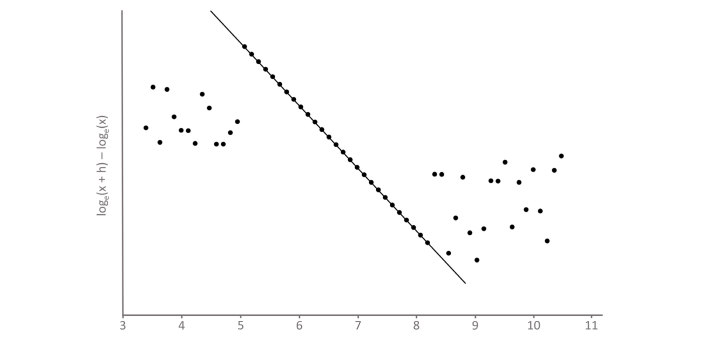

Bhattacharya Analysis

Bhattacharya’s method is a graphical method that involves mathematically straightening the Gaussian distribution prior to plotting the data. Again, the Gaussian component of the mixed population is visualised on the graph as a straight line. The full derivation of the Bhattacharya approach is provided elsewhere.37–39 However, an overview of the derivation provides insight into the apparently convoluted mathematics used. The Gaussian frequency distribution is defined by the function:

where μ – distribution mean and σ – distribution standard deviation.

To ‘straighten’ this function, it is necessary to convert it to a function in terms of x. The first step, then, is to take the natural logarithm of the function. The resulting function then varies in terms of x2. Differentiating this function will give an expression in terms of x. For discrete data, differentiation can be approached by the ‘finite difference approximation’: data is categorised into bins of size h and the frequency of one bin (x) is subtracted from the next bin (x + h).

The Bhattacharya plot, which we refer to as the Bhattagram, graphs loge(x + h) - loge(x) on the y-axis versus the mid-point of the bin (x) on the x-axis. Consequently, points will appear in a straight line where the distribution is Gaussian (Figure 4). The slope and intercept of the line of best fit of these points can be used to determine the mean and SD of the Gaussian component of the distribution. Specifically:

Figure 4.

Bhattagram of dataset 3(A). The dataset shown in Figure 3(A) is graphed on a Bhattacharya plot, or ‘Bhattagram’. Loge(x + h) - loge(x) is plotted on the y-axis, where h is the data bin width, against the midpoint of the bin on the x-axis. The central Gaussian component of the dataset is visualised as linearly-related points with a negative slope. The mean and standard deviation of the Gaussian component of the dataset can be calculated from the slope and y-intercept of the line of best fit of these data points.

Bhattacharya’s original method involved establishing a line of best fit by eye using a piece of translucent paper with a line drawn on it.37 Nowadays, spreadsheets40 and computer programs41 are available online, which can produce a Bhattagram and use linear regression to determine a line of best fit for the segment that the operator visually identifies as the straight-line component.

Several modifications to the basic Bhattacharya approach have been developed to address some of the potential pitfalls of the technique. Hemel suggested plotting the residuals of the linear regression to ensure that they are randomly distributed around zero. If they are not, it suggests that the distribution of the analyte is not Gaussian or has been distorted by a subpopulation.39 Others have suggested the rule of thumb that the data should only be analysed for reference intervals, if the linear part of the Bhattagram represents at least 40% of the total population, to ensure that the distributions of subpopulations are not too close.38

To limit the effect of random statistical variations in the frequency distributions, it is recommended that at least 1500 data points are used.38 The influence of random variation is likely to be larger for the bins with lower frequency.

Bhattacharya suggested that when determining the line of best fit by eye, that the operator ensure the fit is best for the points on the graph where the frequency is high. Hemel proposed the rule of thumb that bins with frequency less than one-tenth of the mode are not included in the analysis.39 Naus proposed the use of weighting factors to reduce the influence of the low frequency bins on the linear regression.42

A further modification that has been proposed for Bhattacharya analysis is using gamma distributions to model the distribution of values from healthy subjects for analytes with a positive skew.42 Software, freely available online, for Bhattacharya analysis includes the ability to model the healthy population with gamma distributions.41

There are a number of elements in these graphical techniques which require the subjective input of the operator. The selection of an appropriate bin size is a significant decision. If it is too small the random variation in the frequency of each bin will increase, however if the bin size is too large there is a loss of resolution in the plot and, furthermore, the finite difference approximation to the differential in the Bhattacharya method becomes inaccurate. Selecting the best bin location, that is adjusting the position of all bins of the same fixed size slightly from side to side, may also be done to achieve the optimal fit.

The selection of the points on the graph that represent the Gaussian component of the distribution is also a subjective determination. The central points of the Hoffmann plot or Bhattagram are generally clear. However, it is deciding whether to include the points towards the margins that is more difficult. This decision may be supported by software which allows the operator to inspect the Gaussian plot as well as the residuals from the line of best fit. Some authors have used algorithms to determine the linear portion automatically.43 However it is unclear whether this is an advance over operator-selected fit.

Pryce Method

The method of Pryce analyses the central component of a mixed distribution. It assumes that the central component of the distribution represents values from healthy individuals and follows a Gaussian distribution. It is designed to determine the mean and SD of this component using simple statistics, as it was developed before computers were routinely used for calculations.44

The approach requires knowledge of whether results from subjects with disease occur on just one end of the mixed distribution or on both ends. For instance, AST results from subjects with disease would be expected to occur only on the high side of the mixed distribution, while sodium results from subjects with disease will appear on either end of the distribution.

When values from subjects with disease occur on both ends of the distribution, the method assumes that the presence of these results does not affect the distribution of values from healthy subjects on 1 SD either side of the mean (Figure 5). The mean of the healthy population is therefore estimated from the mean of the mixed distribution and the SD from one-half of the distance between the 16th and 84th percentiles. In the scenario where results from subjects occur only on one side of the distribution, the mode (highest frequency value) is taken as the estimate of the mean value for healthy subjects and the SD of values from healthy subjects is estimated by determining the absolute difference between either the 16th or 84th percentile and the mode. The 16th percentile is used if results from subjects with disease occur on the high side of the distribution (Figure 6). Conversely, the 84th percentile is used if results from subjects with disease occur on the low side of the distribution. A similar approach for the scenario of abnormal results on one side of the distribution was described by Becktel.29

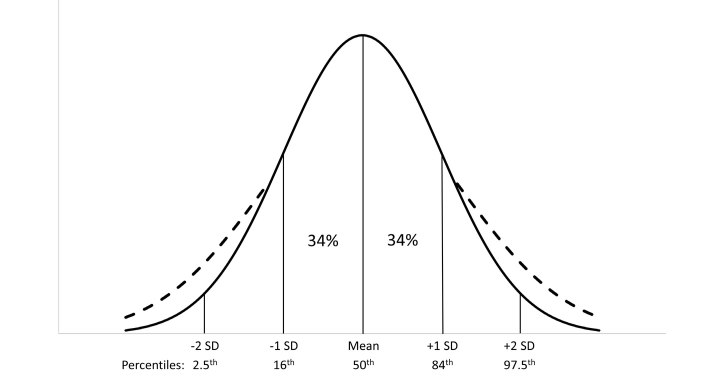

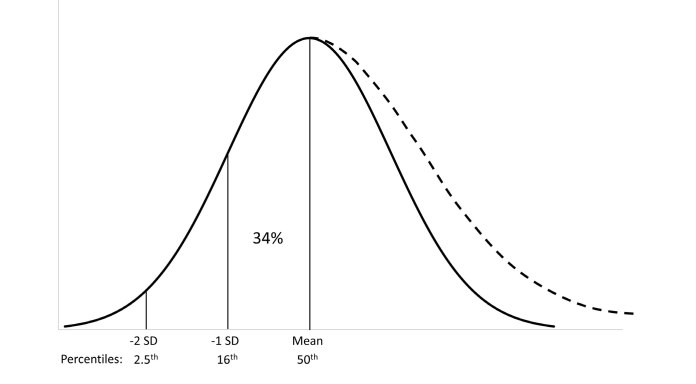

Figure 5.

Principles of Pryce’s method: abnormal values on both ends of the distribution. When values from subjects with disease occur on both ends of the distribution Pryce assumes the values from subjects with disease do not significantly affect the mean value from healthy subjects. The standard deviation (SD) is estimated by assessing 34% of the population on either side of the mean. The solid lines represent the Gaussian distribution of values from healthy individuals. The dashed lines represent the distortion of this distribution by values from subjects with disease.

Figure 6.

Principles of Pryce’s method: abnormal values on one end of the distribution. When values from subjects with disease occur only on one end of the distribution, Pryce uses the mode (highest frequency value) to estimate the mean of values from healthy subjects. The standard deviation (SD) is estimated by assessing 34% of the population on the side of the mode away from the side of the distribution with abnormal values. The solid lines represent the Gaussian distribution of values from healthy individuals. The dashed lines represent the distortion of this distribution by values from subjects with disease.

Recent Developments

Recently, there has been interest in leveraging modern computational power for deriving indirect reference intervals using maximum likelihood estimation.36,45 This approach is exemplified by that of Arzideh et al.,13 who have made software freely available to laboratorians on the website of the German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine.46 The core component of the approach is a truncated maximum likelihood estimation of the parameters (mean, variance, λ) of a power normal distribution.

As a preparative step, the technique creates a density function for the data. This has the advantage over a histogram of smoothing the data into a continuous function. The technique used to create this continuous density function is known as kernel density estimation. In this technique, each observed data point is replaced by a small Gaussian function centred on the data point. This function is known as the ‘kernel’. The kernel functions for all data points are then summed to give an overall smoothed continuous probability density function for the population.

Once the preparative step of creating the density function is complete, the central part of the distribution, assumed to represent the distribution in healthy individuals is analysed. Specifically, the Box-Cox transformation value (λ), mean and variance are determined by ‘maximum likelihood estimation’, which in this context involves the software using an iterative approach to find the parameters most likely to have given the observed results. The limits of the central component of the distribution are defined by an optimisation process that uses the Kolmogorov statistic.

An interesting additional aspect of this approach is the ability to model the distribution of values from subjects with disease. This is achieved by subtracting the density function of the healthy population from the mixed population. This may be useful because the point of intersection of the density function of subjects with disease with the density function of healthy subjects theoretically provides the decision limit with the ‘maximum diagnostic efficiency’ (MDE) in discriminating health and disease. Calculation of this point requires a minimum prevalence of subjects with disease in the dataset. The prevalence required depends on the distance between the modes of the healthy subjects and subjects with disease. If the prevalence becomes too low, the calculated MDE limit can become implausibly high. The authors therefore set the criterion that diagnostic sensitivity of the MDE limit must be greater than 50% for it to be valid. Estimation of MDE limits at the upper end of the distribution has been done for some common chemistry analytes: AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, GGT, LDH, lipase, amylase and CK-MB.13 For most analytes the MDE limit was estimated to be slightly below the 97.5th percentile of the healthy population. Whether the MDE limit might prove clinically useful is an interesting subject for further investigation.

Open source software packages in the R programming language are also available that apply the maximum likelihood approach to fitting Gaussian or gamma distributions to a mixed dataset.36,47 Their use requires familiarity with the R programming languags and, when applied appropriately, are powerful tools for deriving indirect reference intervals.36

Implications for Laboratorians: The Present and the Future

The Present

Currently, the most useful indirect techniques for laboratorians are those that may be applied to mixed datasets. These allow laboratorians to use stored patient results from routine testing. There are no data that clearly point to the superiority of one of these techniques over others. Both the method of Hoffmann and Bhattacharya are well-established and, in our experience, give similar results. The introduction of techniques based on maximum likelihood estimates appears to be a significant advance in the field. A data simulation experiment showed maximum likelihood estimation to outperform the methods of Hoffmann and Bhattacharya.36 Nevertheless, there is less clinical laboratory experience with this approach and hence some caution in its use may be appropriate.

Regardless of the method used, once a laboratorian derives indirect reference intervals, it is important that they are subjected to critical scrutiny. Ideally, this will be done in several different ways. Comparison of the results to published reference intervals using both direct, if available, and indirect methods, should be done and any known method-specific differences between the assays used considered. Results may also be compared to the reference intervals that are used by different laboratories, as well as those used historically at the laboratory at which the data were generated.

Furthermore, if partitioning is done, the reference intervals for the different groups may be compared to known physiology. For example, if it is known that values for the analyte in question increase with age in healthy individuals, then one would evaluate the indirect reference intervals derived to determine if this effect is seen. The percentage of patient results falling outside the derived reference interval should be reviewed, preferably on an independent dataset. For example, the authors of a paper using a flawed Hoffmann approach identified an issue with the reference interval they derived (using a standard value for the allowable deviation from the linear portion of the Hoffmann plot), by determining that 48% of patient results in an independent dataset would be outside the reference interval.34

A laboratorian may also choose to use more than one indirect technique to determine the extent of the between-method variation in indirect reference intervals. Additionally, for techniques in which there are subjective elements, such as those of Hoffmann and Bhattacharya, there may be value in varying the subjective elements within plausible limits to help gain some insight into the degree of within-method variation that may exist.

In summary, the most robust approach for the laboratorian to take when utilising indirect techniques for establishing reference intervals is to consider the results in the context of all the information at their disposal. In this manner, a decision to implement a particular reference interval is based on the convergence of a number of lines of evidence rather than the outcome of a single indirect reference interval study that has not been critically scrutinised.

The Future

The field of study relating to indirect reference intervals has had a slow evolution since the description of methods by the likes of Hoffmann and Pryce in the early 1960s. However, we expect that the revolution in data analytics that has occurred in recent years outside the laboratory will cross over into the medical laboratory in the coming years. A collaboration has already been established between Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Amazon’s data analytics division48 and, although it has not yet addressed issues in the clinical laboratory, it illustrates a mechanism by which future advances in the field may be rapidly realised.

In the coming years, it is likely that maximum likelihood approaches will undergo modification, as was seen for Bhattacharya’s method, as clinical laboratorians gain experience with the technique and come to better understand its limitations. However, the largest advances are likely to come from linkage of databases across the healthcare system. Linkage of laboratory results to known patient diagnoses and clinical outcomes may not only allow the derivation of reference intervals for particular patient populations but also allow the establishment of decision limits for particular clinical questions. Certainly, as technology and techniques develop, it is likely that indirect approaches to establishing reference intervals will become increasingly valuable to laboratorians.

Conclusion

The use of accurate reference intervals is an important responsibility borne by laboratorians. The traditional focus when establishing reference intervals has been on direct reference interval studies. However, modern computing now allows the storage of vast datasets of patient results and the ability to rapidly analyse this data using advanced algorithms. Consequently, the indirect approach to deriving reference intervals is becoming increasingly valuable. The approach is not only inexpensive and quick to perform, but it allows granular assessment of population sub-groups and partitioning of these groups if necessary. Caution does need to be exercised when using the indirect approach. However, a thorough understanding of the principles involved in deriving indirect reference intervals allows the laboratorian to harness the power of the data stored in their laboratory database.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Jones GR, Haeckel R, Loh TP, Sikaris K, Streichert T, Katayev A, et al. IFCC Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits. Indirect methods for reference interval determination - review and recommendations. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;57:20–9. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document EP28-A3c. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2010. Defining, Establishing, and Verifying Reference Intervals in the Clinical Laboratory; Approved Guideline – Third Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Chronic Diseases, 2011–12. [Accessed 17 April 2019]. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4364.0.55.005Chapter1002011-12.

- 4.Daly RM, Gagnon C, Lu ZX, Magliano DJ, Dunstan DW, Sikaris KA, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and its determinants in Australian adults aged 25 years and older: a national, population-based study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:26–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paik JM, Farwell WR, Taylor EN. Demographic, dietary, and serum factors and parathyroid hormone in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1727–36. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1776-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souberbielle JC, Cormier C, Kindermans C, Gao P, Cantor T, Forette F, et al. Vitamin D status and redefining serum parathyroid hormone reference range in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3086–90. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aloia JF, Feuerman M, Yeh JK. Reference range for serum parathyroid hormone. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:137–44. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Heickendorff L, Mosekilde L. Determinants of plasma PTH and their implication for defining a reference interval. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touvier M, Deschasaux M, Montourcy M, Sutton A, Charnaux N, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Interpretation of plasma PTH concentrations according to 25OHD status, gender, age, weight status, and calcium intake: importance of the reference values. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1196–203. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastell R, Arnold A, Brandi ML, Brown EM, D’Amour P, Hanley DA, et al. Diagnosis of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:340–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilezikian JP, Brandi ML, Eastell R, Silverberg SJ, Udelsman R, Marcocci C, et al. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the Fourth International Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3561–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woitge HW, Scheidt-Nave C, Kissling C, Leidig-Bruckner G, Meyer K, Grauer A, et al. Seasonal variation of biochemical indexes of bone turnover: results of a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:68–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.1.4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arzideh F, Wosniok W, Gurr E, Hinsch W, Schumann G, Weinstock N, et al. A plea for intra-laboratory reference limits. Part 2. A bimodal retrospective concept for determining reference limits from intra-laboratory databases demonstrated by catalytic activity concentrations of enzymes. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1043–57. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole S, Schroeder LF, Shah N. An unsupervised learning method to identify reference intervals from a clinical database. J Biomed Inform. 2016;59:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clerico A, Trenti T, Aloe R, Dittadi R, Rizzardi S, Migliardi M, et al. Italian Section of the European Ligand Assay Society (ELAS) A multicenter study for the evaluation of the reference interval for TSH in Italy (ELAS TSH Italian Study) Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;57:259–67. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katayev A, Fleming JK, Luo D, Fisher AH, Sharp TM. Reference intervals data mining: no longer a probability paper method. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:134–42. doi: 10.1309/AJCPQPRNIB54WFKJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilcol YO, Aslan D. Use of total patient data for indirect estimation of reference intervals for 40 clinical chemical analytes in Turkey. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:867–76. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahapola-Arachchige KM, Hadlow N, Wardrop R, Lim EM, Walsh JP. Age-specific TSH reference ranges have minimal impact on the diagnosis of thyroid dysfunction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:773–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell CL, Nguyen L, Carter AC. Data mining for age-related TSH reference intervals in adulthood. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:e213–5. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossi E, Colombo R, Cavuto S, Franzini C. The REALAB project: a new method for the formulation of reference intervals based on current data. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1232–40. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.047787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng C, Wang H, Lu N, Chen T, He H, Lu Y, et al. Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2014;26:105–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Box G, Cox D. An analysis of transformations. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1964;26:211–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichihara K, Ozarda Y, Barth JH, Klee G, Shimizu Y, Xia L, et al. Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits, International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine and Science Committee, Asia-Pacific Federation for Clinical Biochemistry. A global multicenter study on reference values: 2. Exploration of sources of variation across the countries. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;467:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NIST/SEMATECH. e-Handbook of Statistical Methods: Gamma Distributions. [Accessed 10 December 2018]. https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda366b.htm.

- 25.Kouri T, Kairisto V, Virtanen A, Uusipaikka E, Rajamäki A, Finneman H, et al. Reference intervals developed from data for hospitalized patients: computerized method based on combination of laboratory and diagnostic data. Clin Chem. 1994;40:2209–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadiveloo T, Donnan PT, Murphy MJ, Leese GP. Age-and gender-specific TSH reference intervals in people with no obvious thyroid disease in Tayside, Scotland: the Thyroid Epidemiology, Audit, and Research Study (TEARS) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1147–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrell CL, Nguyen L, Carter AC. Parathyroid hormone: Data mining for age-related reference intervals in adults. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;88:311–7. doi: 10.1111/cen.13486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber GM, Kohane IS. Extracting physician group intelligence from electronic health records to support evidence based medicine. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becktel JM. Simplified estimation of normal ranges from routine laboratory data. Clin Chim Acta. 1970;28:119–25. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(70)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann RG. Statistics in the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1963;185:864–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060110068020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann GJ. The determination of normal ranges from routine laboratory data. Clin Chem. 1968;14:979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grecu DS, Paulescu E. Quality in post-analytical phase: indirect reference intervals for erythrocyte parameters of neonates. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:617–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soldin OP, Sharma H, Husted L, Soldin SJ. Pediatric reference intervals for aldosterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, testosterone and 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 using tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:823–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Ma W, Wang G, Lv Y, Peng Y, Peng X. Limitations of the Hoffmann method for establishing reference intervals using clinical laboratory data. Clin Biochem. 2019;63:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones G, Horowitz G, Katayev A, Fleming JK, Luo D, Fisher AH, et al. Reference intervals data mining: getting the right paper. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:526–7. doi: 10.1309/AJCP26VYYHIIZLBK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes DT, Buhr KA. Widespread incorrect implementation of the Hoffmann method, the correct approach, and modern alternatives. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;151:328–36. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqy149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharya CG. A simple method of resolution of a distribution into gaussian components. Biometrics. 1967;23:115–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baadenhuijsen H, Smit JC. Indirect estimation of clinical chemical reference intervals from total hospital patient data: application of a modified Bhattacharya procedure. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1985;23:829–39. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1985.23.12.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemel JB, Hindriks FR, van der Slik W. Critical discussion on a method for derivation of reference limits in clinical chemistry from a patient population. J Automat Chem. 1985;7:20–30. doi: 10.1155/S1463924685000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones GR. Bhattacharya spreadsheet. [Accessed 11 April 2019]. http://www.sydpath.stvincents.com.au/index.htm.

- 41.Chesher D. Bellview: A tool to perform Bhattacharya analysis on laboratory data. [Accessed 4 November 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naus A. De berekening van referentiwwaarden in klinische chemie uit analseresultaten van ee patientenpopulatie (Thesis) 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oosterhuis WP, Modderman TA, Pronk C. Reference values: Bhattacharya or the method proposed by the IFCC? Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:359–65. doi: 10.1177/000456329002700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pryce JD. Level of haemoglobin in whole blood and red blood-cells, and proposed convention for defining normality. Lancet. 1960;2:333–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(60)91480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Concordet D, Geffré A, Braun JP, Trumel C. A new approach for the determination of reference intervals from hospital-based data. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;405:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.German Society of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Decision limits/guideline values. [Accessed 18 December 2018]. https://www.dgkl.de/verbandsarbeit/arbeitsgruppen/entscheidungsgrenzen-richtwerte/

- 47.Benaglia T, Chauveau D, Hunter DR, Young DS. mixtools: An R Package for Analyzing Mixture Models. J Stat Softw. 2009;32:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wood M. Improving patient care with machine learning at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. [Accessed 11 April 2019]. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/machine-learning/improving-patient-care-with-machine-learning-at-beth-israel-deaconess-medical-center/