Abstract

This scoping review maps a wide array of literature to identify academic programs that have been developed to enhance oral health care for rural and remote populations and to provide an overview of their outcomes. Arksey and O’Malley’s 5-stage scoping review framework has steered this review. We conducted a literature search with defined eligibility criteria through electronic databases, websites of academic records, professional and rural oral health care organizations as well as grey literature spanning the time interval from the late 1960s to May 2017. The charted data was classified, analyzed and reported using a thematic approach. A total of 72 citations (67 publications and seven websites) were selected for the final review. The review identified 62 universities with program initiatives towards improving access to oral health care in rural and remote communities. These initiatives were classified into three categories: training and education of dental and allied health students and professionals, education and training of rural and remote community members and oral health care services. The programs were successful in terms of dental students’ positive perception about rural practice and their enhanced competencies, students’ increased adoption of rural practices, non-dental health care providers’ improved oral health knowledge and self-efficacy, rural oral health and oral health services’ improvement, as well as cost-effectiveness compared to other strategies. The results of our review suggest that these innovative programs were effective in improving access to oral health care in rural and remote regions and may serve as models for other academic institutions that have not yet implemented such programs.

Introduction

Dental workforce shortages in rural and remote areas have been reported throughout the world [1–8]. Educational and socio-economic background, altruistic motivation, previous life experience, and exposure to rural and remote community activities have been shown to influence dental professionals’ decisions in their choice of practice location and willingness to work in a rural and remote area [9–11]. Shortages of dental professionals can lead to reduced accessibility to oral health services and poorer oral health status for rural dwellers than for urban populations [2, 7, 12–15]. It has been reported that people living in rural and remote areas have more unmet dental care needs, poorer oral health knowledge and practices and higher rates of dental caries [14, 16, 17].

The World Health Organization has proposed three strategies to improve access to health workers in rural and remote areas: education and regulatory interventions, monetary compensation and management, environment and social support [18]. A variety of strategies have been recommended to resolve disparities in access to oral health services: prevention and promotion through public health approaches, such as water fluoridation and school-based interventions; facilitating infrastructure and technologies through E-health; temporary services through fly in—fly out or mobile clinic services; financial incentives for the dental workforce in the form of scholarships; interdisciplinary approaches to integration of oral health within primary health care; and academic strategies such as rural training and selective recruitment [7, 16, 19, 20]. Educational institutions have developed strategies to overcome problems due to dental workforce shortages, such as the provision of rural training and outreach programs for dental students, oral health training for allied healthcare professionals and students and selective admission of rural applicants [7, 16]. The impact of academic initiatives on an increased rural dental workforce and the concomitant promotion of rural oral health status is less clear, thus emphasizing the need to conduct this comprehensive review.

Over the past decades, various knowledge synthesis methods, such as narrative, integrative, realist, scoping and systematic reviews have been introduced to foster evidence-informed health care [21]. In 2001, Mays, Roberts, and Popay stated that the objective of a scoping review is to rapidly map the fundamental concepts, primary sources and types of evidence on a topic that has not yet been comprehensively reviewed [22]. We mapped a large body of literature to identify rural and remote academic programs and to give an overview of their outcomes, regardless of the quality of the included studies [22].

Materials and methods

The Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review 5-stage framework has steered this review [23]. Accordingly, the scoping review included five steps, as detailed below:

1. Identifying the research question

One specific research question guided the selection of relevant literature for this scoping review: What are the academic programs and their outcomes that have been designed to enhance oral health care for rural and remote populations?

2. Identifying relevant studies and eligibility criteria

Pertinent publications that spanned the time interval between the late 1960s and June 2017 were reviewed. The authors searched for publications by using Ovid (MEDLINE and Embase) and PubMed electronic databases. The search strategy (Table 1), designed for the MEDLINE database search, was later adapted for other databases. The electronic search was completed by hand searching the list of references in the identified publications or relevant reviews. Data were also retrieved from the websites of pertinent universities, as well as relevant professional, rural and remote oral health organizations. We included publications written in English only, in which academic institution initiatives on rural oral health care were the focus of the publications. After title and abstract screening, articles were excluded which showed no focus on university-based initiatives on rural oral health. Some of the articles were also excluded after full-text review (30) which were focused on rural oral health initiatives but lacked any interventions. Although editorials, commentaries, and reviews were excluded, their references to the original studies were searched and included in our study.

Table 1. Medline search strategy.

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | Education, Professional |

| 2 | exp Schools, Dental/ |

| 3 | exp Students, Dental/ |

| 4 | Community Health Services/ or Community-Institutional Relations/ or "Delivery of Health Care"/ or Health Education/ |

| 5 | exp Universities/ |

| 6 | Clinical Competence/ |

| 7 | exp Oral Health/ or exp Dental Health Services/ or exp Dental Care/ |

| 8 | Dentists/ |

| 9 | Dental Auxiliaries/ |

| 10 | Dental Facilities/ |

| 11 | Dentistry/ or Public Health Dentistry/ or Community Dentistry/ or Preventive Dentistry/ or Pediatric Dentistry/ or Dentistry, Operative/ or School Dentistry/ or Geriatric Dentistry/ |

| 12 | exp Rural Health Services/ or Rural Population/ or exp Rural Health/ |

| 13 | Medically Underserved Area/ or Health Services Accessibility/ |

| 14 | Telemedicine/ |

| 15 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 16 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 |

| 17 | 12 or 13 or 14 |

| 18 | 15 and 16 and 17 |

| 19 | limit 18 to (English) |

3. Study selection

Two independent reviewers (RS, EE) screened the titles and abstracts of each citation and identified eligible articles for full review. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus.

4. Charting the data

One reviewer (RS) charted all data obtained from the selected publications based on authors, years, country, type of publication, program description, program outcomes measures, and results. The other reviewer (EE) then randomly checked 10% of the extracted data to ensure accuracy. Any noted discrepancy was rectified by consensus.

5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The charted data were summarized and reported using descriptive a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis approach. Investigator triangulation was conducted by the scoping review team (RS, EE, FP, FT, JF) who reviewed the charts, results and outcome measures.

Results

Characteristics of the included publications

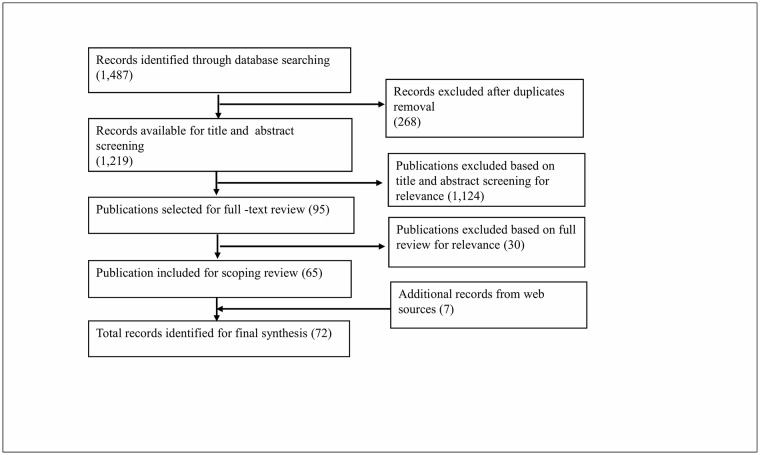

Electronic and hand searches generated 1,487 records (Fig 1). After removal of duplicates, the title and abstract screening was conducted for 1,219 citations, out of which 95 articles were selected for full-text review. From these articles, 65 publications met the eligibility criteria for the scoping review. Additional information was found from 7 healthcare or educational organizations’ web records that were relevant to our scope of review. The inclusion of these records then generated a total of 72 records for final synthesis.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of search strategy.

The scoping review identified a total of sixty-two universities taking initiatives towards improving access to oral health care in rural and remote communities. These publications were identified from 16 countries: USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Scotland, Malta, Brazil, Peru, India, China, South Africa, Nigeria, Uganda, Romania, and Bulgaria. Most of the included publications were from North America, Asia, and Australia and were published in the last decade.

Program classification

Based on our scoping review results, we identified three categories of programs that have been implemented in various universities. The first category characterizes programs for the training and education of dental and allied health students and professionals [1, 3, 11, 24–67]; the second category describes programs for the education and training of rural and remote community members [68–73] and the third category represents programs on oral healthcare services in rural and remote areas [41, 42, 61–63, 68, 69, 73–92].

Themes identified in these university-based rural oral health initiatives

All included programs were clustered into the following four themes identified as implementation platforms. These were the curriculum-based platform; joint programs with the public health sector, organizations and community platform, E-health platform, and mobile dentistry platform (Table 2). Some of the identified programs overlapped under these platforms due to their common objectives.

Table 2. Description of program platform themes based on program categories.

| Platforms | Programs for training and education of dental and allied health students and professionals | Programs for education and training of rural and remote community members | Programs for oral health care service in rural and remote areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curriculum-based |

|

||

| Joint programs with the public health sector, organizations and community |

|

||

| E-health |

|

||

| Mobile dentistry |

|

Curriculum-based platform: This platform incorporated various programs under the first category, classification of training and educational programs for dental students and allied health care professionals and students [1, 3, 11, 24–62]. These programs included 1 to 10 weeks of rural placement training for dental students (mostly fourth and fifth years and internship level) and dental hygiene students; dental education courses; outreach programs; postgraduate fellowship programs; and programs to encourage rural students, under-represented minority and low-income students to study and practice dentistry. The platform for the second category of education and training programs for rural and remote community members included patient oral health education and rural school teachers’ training [68–71]. Lastly, the curriculum based platform for programs in the third category of oral health care services incorporated programs for providing and improving oral health care services and fulfilling the community’s oral health-related needs [41, 42, 61, 62, 68, 69, 74–79].

Joint programs with the public health sector, organizations and community platform: This platform for the first category of training and education programs for dental and allied healthcare professionals and students included training of health workers [63]. Aboriginal health workers were responsible for managing patient appointments and communications, as well as oral health promotion activities with the dentists [63]. For its second category of classification, this platform incorporated training of school teachers and the oral health education of children [72]. Finally, for the third category, this platform included programs for oral health promotion: school-based oral health education and services and culturally-sensitive oral health care programs with community-led recruitment of its dentist, dental assistant, and Aboriginal health worker [63, 80–83].

-

E-health platform: This platform offered teledentistry that facilitated the training of an allied dental workforce for the first category of classification [64]. No relevant article was found in relation to the second category of the classification.

This platform for the third category of classification included programs focused on oral health services through video consultation with dental specialists and a virtual dental home concept (telehealth dental home) for risk assessment, preventive and operative services and follow-ups [84, 85].

Mobile dentistry platform: This platform offered programs for the training of students in dentistry and allied dental professions by providing them with experience in mobile dental outreach under the first category [65–67]. It included programs focused on patient education for the second category [73]. Finally, for the third category, it encompassed programs that provided oral examinations and consultation, as well as preventive, curative and referral oral health services that improved patients’ oral health status [91, 92].

Evaluations of programs (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6)

Table 3. Summary of published research articles identified in the scoping review (1969–2005).

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Podshadley AG, et al.; 1969/ USA [41] Heise AL, et al., 1973/ USA [42] |

University of Kentucky | Original research report | “Community Clinical Laboratory” as 6 hours’ course for final year dental students providing comprehensive dental care for rural children with mobile dental units | Effect on oral health status, cost-effectiveness, and students’ competencies/Oral examination, cost analysis, questionnaire |

|

| Kurtzman C, et al.; 1974 [88] | University of California at Los Angeles and University of Southern California | Original research report | Mobile Dental Project for agriculture workers’ children in rural southern California by dental and dental hygiene students from all classes | Effect on oral health services/Descriptive measurement |

|

| McMillan WB, et al.; 1975 [35] | University of Minnesota | Original research | Summer rural dental externship program for third-year dental students | Students’ competencies; dentists’ and students’ satisfaction/Pre-and post-questionnaires |

|

| Bentley JM, et al.; 1983/ USA [68] | University of Pennsylvania | Original research (experimental study) | Rural Dental Health Program for rural children randomly assigned to school-based practice group and private practitioners’ group that was further divided into improved dental health program and regular health program. | Comparing utilization of services by children over three years/Descriptive measurement |

|

| Feldman CA, et al.; 1988/ USA [69] | University of Pennsylvania | Follow up study | Follow up of the Rural Dental Health Program by Bentley JM, et al.; 1983 [68], evaluated seven years after the funding ended | Long-term evaluation after seven years/Health and oral health-related indices |

|

| Shreve WB, et al., 1989/ USA [44] | University of Florida (contract basis with Lafayette-Suwannee Rural Health Corporation, Inc.) | Original research | Extramural 2-weeks dental education program for dental students | Impact on education, research and services/In-house and external evaluation and surveys |

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Burger AD, et al.; 1997/ USA [65] | Youngstown State University | Original research | Dental Disease Prevention and Early Intervention Program to train dental hygiene students and provide essential services to rural population: senior dental hygiene students worked in pairs with supervision of dentist using a mobile dental unit |

|

|

| Pacza T, et al.; 2001/ Australia [59] |

University of Western Australia | Original research (pilot program) | Oral health training program for rural and remote Aboriginal health workers to implement a culturally sensitive preventive oral health care delivery program |

|

|

| Kaakko T, et al.; 2002/ USA [74] | University of Washington | Original research (randomized clinical trial) | Access to Baby and Child Dentistry (ABCD) program involving Medicaid- enrolled children in rural Stevens County compared with children who had regular benefits |

|

|

| Richards L, et al.; 2002/ Australia [79] | University of Adelaide | Clinical report | Final year dental students posted in rural public dental service clinics at Whyalla and Port Augusta |

|

|

| Mouradian WE, et al.; 2003 [11] | University of Washington | Original research | Interdisciplinary Children’s Oral Health Promotion Project at University affiliated Family Practice Residency Network to train family medicine residents |

|

|

| Gonsalves WC, et al., 2004/ USA [60] | University of Kentucky | Original research | Physicians’ oral health education for family medicine residents on children’s oral health screening, risk assessment, and counseling |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Woronuk JI, et al.; 2004/ Canada [37] | University of Alberta | Original research | Satellite dental program for third and final year dental students |

|

|

| Elkind A, et al.; 2005/ UK [51] | University of Manchester | Original research (pilot project) | Pilot outreach program for final year dental students in restorative dentistry and clinical sessions at the dental hospital |

|

|

| Parker EJ, et al.; 2005/ Australia [82] | University of Adelaide | Preliminary project report | The culturally-sensitive oral health program for the Aboriginal community in Port Augusta—first phase in partnership (with Pika Wiya Health Service, South Australian center for rural and remote health and South Australian Dental service) |

|

|

Table 4. Summary of published research articles identified in the scoping review (2006–2010).

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Bernabe E, et al.; 2006/ Peru [47] | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia | Original research | Dental Public Health Teaching-learning experiences of dental students in low income communities |

|

|

| Harrison RL, et al.; 2006/ Canada [61] | University of British Columbia | Original research report | Brighter Smiles program trained pediatric residents in a remote First Nations community including brush-ins, fluoride application, oral presentations, and regular visits by pediatric residents |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Bazen JJ, et al.; 2007/ Australia [3] | University of Western Australia | Original research | Rural, remote, and Aboriginal pre-graduation placements for dental students under the supervision of dentists |

|

|

| Branson BG, et a.l; 2007/ USA [38] | University of Missouri-Kansas City | Original research | Dental hygiene student rotations to rural and underserved areas |

|

|

| Hunter ML, et al.; 2007/ UK [52] | Wales College of Medicine | Original research (pilot study) | Community dental service outreach teaching program for final year dental students for providing pediatric dental care |

|

|

| Lo ECM, et al; 2007/ China [81] | University of Hong Kong | Original research | 3-year outreach dental service program in four primary schools in rural town in southern China (partnered with WHO Collaboration Centre on Primary Health Care) |

|

|

| Macnab J, et al.; 2008/ Canada [62] | University of British Columbia | Original research | Same as Harrison RL, et al.; 2006 [61], three years’ evaluation |

|

|

| Schoo AM, et al; 2008/ Australia [33] | Flinders University and Deaking University | Original research (pilot study) | Medical, dental, nursing and allied health students were enrolled in the rural placement program |

|

|

| Shrestha A, et al.; 2008/ India [75] | Manipal College of Dental Sciences | Original research (cross-sectional survey) | Weekly and monthly conduction of rural outreach dental camps |

|

|

| Abuzar MA, et al.; 2009/ Australia [25] | University of Melbourne | Original research | Rural dental rotation program for education and training of final year dental students |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Andersen RM, et a.l; 2009/ USA [55] Friedman JA, et al.; 2009/ USA [56] Kuthy RA, et al.; 2009/USA [58] Thind A, et al.; 2009/ USA [57] |

National Pipeline schools (11): Universities of Boston, Howard, Temple, Ohio State, South Carolina, Connecticut Health Center, Washington, West Virginia, University of California at San Francisco, University of Illinois at Chicago, and Meharry Medical College California Pipeline schools (4): Universities of Pacific, Southern California, University of California at Los Angeles, and Loma Linda University | Original project | USA Dental Pipeline Project– 2001 to 2010, one of the most extensive projects that involved various dental schools aimed to increase the recruitment and retention of students from under-represented minorities (URM) and low-income groups in dental schools |

|

|

| Fricton J, et al.; 2009/ USA [84] | University of Minnesota | Original project (as a chapter in Dental Clinics of North America) | University of Minnesota Tele-dentistry Project using real-time video conferencing |

|

|

| Skinner JC, et al; 2009/ Australia [54] | Charles Sturt University | Original research report | Charles Sturt University Dentistry program for rural students to study and practice dentistry in rural areas |

|

|

| Arevalo O, et al.; 2010/ USA [91] | University of Kentucky | Original research (cost analysis) | Dental Outreach Programs Kentucky: four mobile dental clinics for elementary school children and Head Start children in several rural counties |

|

|

| McFarland KK, et al.; 2010/ USA [49] | University of Nebraska | Original research (retrospective study) | Analysis of dental students’ attitudes from 1989 to 2008 about rural practice |

|

|

Table 5. Summary of published research articles identified in the scoping review (2011 onward).

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Bhayat A, et al.; 2011/ South Africa [67] | University of Witwatersrand | Original research project report | Final year dental students were enrolled in two groups for outreach:

|

|

|

| Summerfelt FF; 2011/ USA [64] | University of Northern Arizona | Original research | Pilot teledentistry program having dental hygiene students as mid-level practitioners in rural areas |

|

|

| Martinez-Mier, et al.; 2011/ USA [43] | Indiana University | Original research | Hidalgo International Service-learning programme with multidisciplinary students and faculty- dental, medical, nursing, public health and social work |

|

|

| Parlani S, et al; 2011/ India [71] | Chhatrapati Sahuji Maharaj Medical University | Original research | Awareness programs of prosthodontics among aging rural population |

|

|

| Bulgarelli AF, et al.; 2012/ Brazil [50] | University of São Paulo | Original Research | Huka-Katu (beautiful smile) culturally adapted outreach programs in an Indigenous community for final year dental students |

|

|

| Glassman P, et al.; 2012/ USA [85] | University of Pacific | Original research (First phase of demonstration project) | Virtual Dental Home program (Expansion of dental home concept with use of advanced telehealth technology by teamwork between registered dental auxiliaries and distant dentists |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Macnab A, et al., 2012/ Uganda [72] | Joint Ugandan/ Canadian university (University of British Columbia and Makerere University) | Original research intervention study (project report) | ‘Many voices, one song’: oral health model of health promoting schools based on Brighter Smiles program for the Aboriginal community in Canada. It included health education by local teachers and the university team and daily in-school tooth brushing |

|

|

| Parker EJ, et al.; 2012/ Australia [63] | University of Adelaide | Original research evaluation study | Aboriginal children’s Dental Program in Port Augusta by dental therapists and dentists; Integrated health project involving health promotion by conducting a workshop for Aboriginal health workers by dental students with key role of local primary health care provider (in collaboration with Pika Wiya Aboriginal Health Service) |

|

|

| Tandon S, et al.; 2012/ India [73] | Manipal College of Dental Sciences | Original research | Mobile dental health care services in rural areas |

|

|

| Vashisth S, et al.; 2012/ India [77] | Swami Devi Dayal Dental College | Original research (retrospective study) | Various outreach programs in rural areas |

|

|

| Johnson G, et al.; 2011/ Australia [27] | University of Sydney | Original research | 1-month duration of Rural Placement Program was initiated for 4th-year dental students. |

|

|

| Johnson G, et al.; 2012/ Australia [1] |

|

|

|||

| Johnson G, et al.; 2013/ Australia [28] |

|

|

|||

| Johnson G, et al.; 2013/ Australia [29] |

|

|

|||

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Dawkins E, et al.; 2013/ USA [86] | University of Western Kentucky | Original research | Free dental sealant and oral examination program through mobile dental unit for school children since 2001[86]. |

|

|

| Ibiyemi O, et al.; 2013/ Nigeria [40] | University of Ibadan | Original research project report | Ibarapa Community Oral Health Programme: 6-week rural posting program for fifth-year dental students at Igboora |

|

|

| Lalloo R, et al.; 2013/ Australia [30] | Griffith University | Original Research | Remote rural clinical placement in Indigenous Community over three years from 2009 to 2011 |

|

|

| Lalloo R, et al; 2013/ Australia [31] |

|

|

|||

| Lalloo R, et al.; 2013/ Australia [32] |

|

|

|||

| Chandrashekar B, et al.; 2014/ India [70] | Kamineni Institute of Dental Sciences | Original research (intervention study) | Oral health promotion intervention study for six months with children divided into four groups: 1: Control group: no subsequent education 2: Education by a qualified dentist at every three months 3: Education by the trained school teachers with oral hygiene screening 4: Intervention 3 + children were given the oral hygiene aids |

|

|

| Goel P, et al.; 2014/ India [92] | Rajasthan Dental College | Original research | Indigenously fabricated mobile portable dental unit |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Naidu A, et al.; 2014/ Canada [80] | McGill University | Original research | Community-based participatory research to promote oral health of school children in a rural Aboriginal community |

|

|

| Nayar P, et al.; 2014/ US [46] | University of Nebraska | Original research | Rural community- based dental education program for dental students to improve their competencies. |

|

|

| Anderson VR, et al.; 2015/ New Zealand [34] | University of Otago, New Zealand | Original research report | Oranga Niho dental student outplacement project for final year dental students |

|

|

| Asawa K, et al.; 2015/ India [87] | Pacific Dental College and Hospital | Original research (retrospective study) | Dental outreach programs for rural population through mobile dental units |

|

|

| Okeigbemen SA, et al.; 2015/ Nigeria [78] | University of Benin | Original research (retrospective study) | Rural outreach dental clinic |

|

|

| Vashishtha V, et al.; 2015/ India [76] | D.J. College of Dental Sciences and Research | Original research (cross-sectional study) | Community dental outreach programs for the 1-month duration |

|

|

| Abuzar MA, et al.; 2016/ Australia [26] | University of Melbourne | Original research (case study) | Aboriginal community oral health placement for final year DDS and BOH (Bachelor of Oral Health) |

|

|

| Author; Year/ Country | University/ Institution | Type of publications | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument | Results |

| Okeigbemen SA; 2016/ Nigeria [48] | University of Benin | Case study | Clinic-based curriculum for the dental students |

|

|

| Shannon CK, et al.; 2016/USA [36] | University of West Virginia | Original research (survey) | 6-week community-based rotations for senior dental students from 2001–2012 |

|

|

| Verma A, et al.; 2016/ India [39] | M.R. Ambedkar Dental College, V.S. Dental College, and M.S. Ramaiah Dental College | Original research (Non-randomized trial) | Outreach program where dental interns were divided into outreach group and dental school-based group |

|

Higher confidence and communication skills among outreach group students |

Table 6. Summary of non-research publications including relevant web records identified in the scoping review.

| Author; year/ Country | University/ Institution | Program description | Outcome variable/ Measurement instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| The S-Miles To Go Mobile Dental Program; 1997/ USA [90] | Buffalo University | Mobile dentistry program for rural Chautauqua County children |

|

| Dental Training Expanding Rural Placements (DTERP) Program; 2013/ Australia [24] | Universities of Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Western Australia, Queensland, Griffith University, Flinders University | Program to improve rural access to dental services by expanding dental training through placements in rural settings |

|

| NHS Education for Scotland; 2014/ Scotland [53] | Scottish Universities, e.g. University of Dundee, University of Edinburgh, and University of Glasgow | Scottish Dental Postgraduate Training Fellowship program, an initiative for rural Scotland |

|

| RIDE: UWSOD Regional Initiatives in Dental Education; 2015/ USA [45] | University of Washington | Regional Initiatives Project in Dental Education for improving oral health access by increasing number of dentists |

|

| Better Oral Health in European Platform; 2015/ Malta [66] | University of Malta | ‘Our Drive for a Healthy Smile’ with the help of a mobile dental clinic |

|

| European Commission; 2016/ Romania [89] | SAN-CAR—mobile dental health care with Constanta’s Ovidius University | SAN-CAR—mobile dental health care for rural communities in Romania and Bulgaria |

|

| Poche Centre for Indigenous Health- 5 Year strategy, Strategic plan 2016–2020: on Healthy Kids, Healthy Teeth, Healthy Hearts; 2016/ Australia [83] | University of Sydney | Healthy Kids, Healthy Teeth, Healthy Hearts program: To improve health services and capacity- and skill- building |

|

Measuring instruments for outcomes

Three main approaches have been used to evaluate the programs: quantitative, qualitative and mixed. In the quantitative approach, instruments such as questionnaires (closed and open-ended, pre- and post-, anonymous, electronic online) [1, 3, 11, 25–27, 31, 33, 35, 36, 39, 46, 51, 52, 60, 64, 65, 73, 75, 76, 82, 84, 85], oral examinations [61, 62, 74], health and oral health-related indices [69], descriptive measurements [29, 30, 40, 43, 49, 54–58, 64, 65, 68, 70, 74, 77, 78, 81, 85–88], measurement of grades [37] and SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunities and threat) analyses [43] were used. Additionally, quantitative measurements, such as cost per patient, marginal cost and cost analysis [32, 41, 42, 79, 91, 92] were used to measure the cost-effectiveness of various programs. For qualitative measurement, tools, such as data documentation [63], interviews [28, 47, 50, 63, 80] and mixed approaches, questionnaires in combination with focus group discussions, interviews and open-ended questionnaires [34, 38, 48, 59, 67, 71, 72] were used to measure the outcomes.

Outcome variables

-

Outcome variables for training and education programs

These included students’ competencies and experience [1, 3, 11, 25–27, 31, 34, 38–43, 47, 50–52, 60, 64, 65, 67], supervising dentists’ and students’ satisfaction [35, 38, 84], staff and supervisors’ attitude, experience, and feasibility [3, 28, 34, 43, 46, 64, 85], client/patient and caregivers’ attitude [34], attitudes of health workers [59] and student evaluations by supervising dentists [37]. Also, several impacts were observed, such as effects on students’ education, research and oral health services [44], impact on rural recruitment and graduate retention [24, 29, 33, 36, 49, 54] and on minority and rural student enrollment [55–58].

-

Outcome variables for oral health service related programs

These outcome variables included community acceptance [82], identification of challenges [63], knowledge, attitude and satisfaction among patients [72, 73, 75, 76], changes in oral health practices [80], changes in oral health status [41, 42, 61, 62, 70, 72, 74, 86], effect on oral health services [48, 77, 87, 88] and utilization of services [63, 68, 71, 74, 78].

-

Other outcomes

These variables consisted of audited reports of services provided [30], cost-effectiveness [41, 42, 79, 81, 91, 92] and expenditures [32, 74].

Program evaluation results (Tables 3–6)

Outcomes of rural oral health initiatives and their impact varied among these programs. Accordingly, most of the training and education programs were shown to be feasible through feedback from staff, academic personnel, and trainees. For example, these programs were reported to have helped improve students’ and trainees’ clinical competencies and social sensitization, and provided them with positive experiences and satisfaction [1, 3, 11, 25–27, 31, 34, 35, 37–43, 47, 50–52, 59, 60, 64, 65, 67, 84]. Staff and supervisors noted positive attitudes and experiences, as well as satisfaction with and feasibility of these programs [3, 28, 34, 35, 38, 43, 46, 64, 84, 85]. Also, the programs demonstrated an increased enrollment, recruitment and retention of dental students in rural and remote areas [24, 29, 33, 36, 49, 54–58] and cost-effectiveness [41, 79, 81, 91, 92]. The clients/patients and caregivers of these training programs had experienced positive attitudes and acceptance of these initiatives [34]. Furthermore, oral health service-related programs had identified and reported community acceptance [82], improved knowledge, attitude and satisfaction among patients [72, 73, 75, 76], improved oral health practices [80], better oral health status [41, 42, 61, 62, 70, 72, 74, 86], improved quality of oral health services [48, 77, 87, 88] and enhanced utilization of services [63, 68, 71, 74, 78].

These oral health care services included the provision of more interventional procedures compared to preventive and improved referral services. A few programs reported barriers to these outcomes, such as short duration, deeming them insufficient to experience and practice rural dentistry [3].

Discussion

In most of the countries, rural-urban health disparities are seen not only in dentistry but also in other health disciplines namely medicine, pharmacy, nursing. It is mostly linked to the disproportionate distribution of health care providers including dentists, physicians, nurses, and pharmacists [8, 93]. Government organizations, for-profit and non-profit non-governmental organizations and academic institutions around the world have taken several steps towards improving access to rural dental care. In this extensive literature scoping review, we have reported evidence of academic institutes’ initiatives in improving access to oral health care for rural and remote communities.

Outcomes of this scoping review revealed that students benefitted from these university initiatives by having opportunities to work in real-world situations that inspired them to learn [46], practice various procedures, manage the diversity of patients and gain experience working in a team [26]. Indicators for the success of these programs were: students’ satisfaction with the program, community-based experience, enhanced communication skills and self-confidence; a high rate of treated patients; reduced oral health problems in rural areas after rural placements; and an increased percentage of students working in rural dental practices [1, 3, 11, 24–27, 29, 31, 33–43, 47, 49–52, 54–65, 67, 68, 70–72, 74, 78, 84, 86]. The effectiveness of rural exposure through training in universities and institutions was found to vary due to reasons such as the short duration of rural placement programs, as well as a lack of standardized methodologic and evaluation tools [94]. According to Lalloo et al., confidence among dental students in choosing a dental practice in rural areas was the most relevant outcome measure of the impact of students’ rural placement programs [31]. Orpin et al. commented that the subsequent fair distribution of the rural workforce would be the ultimate test in evaluating the effectiveness of these kinds of programs, although that would be a long-term vision [94]. Rural areas, by virtue of being smaller, offer better opportunities for any program to be successful due to logistical ease of administrative coordination and collaboration, with less organizational and managerial impediments than in urban settings [16].

Most of the mobile dental clinics, dental camps, and dental outreach programs successfully disseminated awareness, provided treatment and enhanced access to care for people living in rural areas. Results from the various outreach programs showed that they could assist in bridging the wide gap created between rural residents’ actual dental needs and their demand for dental care [71, 73, 75–78, 87]. Integration of telehealth into rural oral health services is likely to be successful, but more time is needed to realize the full oral health implications of rural E-health technology [16].

In most of the programs, universities received funding from various sources, but some programs could not be continued due to lack of funding [63, 68]. If the necessary funds become available, it is expected that these services could be provided at a marginal cost when compared to the costs of similar treatments provided by either public-sector staff or private practitioners [79]. The strong motivation of academia’s initiatives to improve oral health care access for rural and remote communities appears to be justified by their positive and effective results; however, long-term evaluations by the institutes and their partners are crucially needed. Most often, curative services were provided in these programs; hence, there is a need to shift our focus towards preventive and promotional oral health services to achieve the global vision of eliminating oral health disparities among rural and remote communities.

Training undergraduate dental students has the potential to improve dental services in rural areas, particularly in areas with limited or no publically-funded dental services [79]. The total cost of the services provided by students, including their travel, living and supervision, is lower than that of private dental providers [79]. The results of our scoping review suggested that very few outreach programs were found to be cost-effective [41, 81, 92]. These programs not only significantly reduced the cost of setting up dental clinics or mobile dental clinics but also further lower costs by using available local resources and staff, such as school teachers [81]. However, long term evaluation are required to determine true cost-effectiveness of these programs. One study demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of a rural outreach program using a portable dental unit [92]. The cost of dental services provided by students with mobile dental units may be high initially, but they become cost-effective over time. [41].

The types of academic initiative programs stated in our scoping review benefited both the rural communities and the academic institutions. Rural residents gained access to dental services and students from the academic institutions gained experience in their field and had an opportunity to develop clinical practice skills by providing care to a broad range of patients.

The WHO has provided strategies and recommendations on improving access to health workers in rural and remote areas [18]. According to these strategies, medical and dental schools were identified as playing a major role by enrolling students from rural backgrounds and establishing professional schools in rural areas or on the outskirts of major cities [18]. WHO also recommended students’ clinical rotations in rural areas, as well as introducing rural health issues in the curriculum [18]. Among these WHO recommendations [18], results from our scoping review reveal the major contribution of such institutions through student rural rotations and by enrolling students from rural areas for health promotion activities, thereby reducing cost and related expenditures. However, some countries like Australia has established new dental schools predominantly in rural and remote areas with the aim of increasing the recruitment of rural students, and ultimately providing a rural workforce.

Our scoping review identified the following gaps in the existing literature on academic initiatives in rural and remote areas. These include great variability in program design, duration, data collection tools (often non-standardized), more focus on curative dental services as opposed to preventive or promotive services and lack of sustainable financial support.

Limitations

The main limitations of this scoping review are twofold. Firstly, the literature review was restricted to articles written in English only. There is likely published work in some other areas of the world like Europe and South America in other languages. Secondly, these publications were not assessed specifically for scientific quality; thus, the results of this scoping review should be interpreted carefully.

Recommendations

These findings point to the following empowering ‘next steps’ for international universities and training institutes: development of international partners to conduct long-term program evaluations; create a mandate to expand and sustain rural residency programs; build strong partnerships with public and private health sectors; promote interdisciplinarity of rural health provision; and build links with policy makers to mobilise the support, development and implementation of universal academic rural and remote oral health programs. Future programs could be customized to address the disparities for a country’s or region’s rural health care needs while considering the administrative, educational and fiscal structure of dental faculties and their universities.

Conclusion

This scoping review describes university-based initiatives in improving access to oral health care in rural and remote regions. The results suggest that these innovative programs are transferable and may serve as valuable models for other academic institutions to promote the oral health of rural and remote populations and improve their right of access to oral health care.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Natalie Clairoux, Librarian, Université de Montréal for her contribution in developing the search strategy. Dr. Elham Emami is supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research Clinician Scientist Award.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Johnson G, Blinkhorn A. Assessment of a dental rural teaching program. European journal of dentistry. 2012;6(3):235–43. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emami E, Khiyani MF, Habra CP, Chasse V, Rompre PH. Mapping the Quebec dental workforce: ranking rural oral health disparities. Rural and remote health. 2016;16(1):3630 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazen JJ, Kruger E, Dyson K, Tennant M. An innovation in Australian dental education: rural, remote and Indigenous pre-graduation placements. Rural and remote health. 2007;7(3):703 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cane R, Walker J. Rural public dental practice in Australia: Perspectives of Tasmanian government-employed dentists. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2007;15(4):257–63. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emami E, Feine J. Focusing on oral health for the Canadian rural population. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine. 2008;13(1):36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruger E, Tennant M. Oral health workforce in rural and remote Western Australia: Practice perceptions. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(5):321–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emami E, Wootton J, Galarneau C, Bedos C. Oral health and access to dental care: a qualitative exploration in rural Quebec. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine. 2014;19(2):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDI World Dental Federation. The Challenge of Oral Disease–A call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation, 2015.

- 9.Mofidi M, Konrad TR, Porterfield DS, Niska R, Wells B. Provision of care to the underserved populations by National Health Service Corps alumni dentists. Journal of public health dentistry. 2002;62(2):102–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CS, Ester TV, Inglehart MR. Dental education and care for underserved patients: an analysis of students’ intentions and alumni behavior. Journal of dental education. 2006;70(4):398–408. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouradian WE, Schaad DC, Kim S, Leggott PJ, Domoto PS, Maier R, et al. Addressing disparities in children’s oral health: a dental-medical partnership to train family practice residents. Journal of dental education. 2003;67(8):886–95. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A, Purohit BM. Addressing oral health disparities, inequity in access and workforce issues in a developing country. International dental journal. 2013;63(5):225–9. 10.1111/idj.12035 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vargas CM, Dye BA, Hayes KL. Oral health status of rural adults in the United States. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2002;133(12):1672–81. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruger E, Jacobs A, Tennant M. Sustaining oral health services in remote and indigenous communities: a review of 10 years experience in Western Australia. International dental journal. 2010;60(2):129–34. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharifian N, Bedos C, Wootton J, El-Murr I, Charbonneau A, Emami E. Dental students’ perspectives on rural dental practice: A qualitative study. J Can Dent Assoc. 2015;81:f53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skillman SM, Doescher MP, Mouradian WE, Brunson DK. The challenge to delivering oral health services in rural America. Journal of public health dentistry. 2010;70 Suppl 1:S49–57. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogunbodede EO, Kida IA, Madjapa HS, Amedari M, Ehizele A, Mutave R, et al. Oral Health Inequalities between Rural and Urban Populations of the African and Middle East Region. Advances in dental research. 2015;27(1):18–25. 10.1177/0022034515575538 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organisation. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: Global policy recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnett T, Hoang H, Stuart J, Crocombe L. Non-dental primary care providers’ views on challenges in providing oral health services and strategies to improve oral health in Australian rural and remote communities: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2015;5(10):e009341 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emami E, Harnagea H, Girard F, Charbonneau A, Voyer R, Bedos CP, et al. Integration of oral health into primary care: a scoping review protocol. BMJ open. 2016;6(10):e013807 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013807 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kastner M, Antony J, Soobiah C, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;73:43–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dijkers M. What is a scoping review? KT Update. 2015;4(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 29722555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dental Training Expanding Rural Placements (dterp) Program 2011-14- Operational framework 2013 [updated 17 Sep 2013]. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/work-st-dterp-gui.

- 25.Abuzar MA, Burrow MF, Morgan M. Development of a rural outplacement programme for dental undergraduates: students’ perceptions. European journal of dental education: official journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe. 2009;13(4):233–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00581.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abuzar MA, Owen J. A Community Engaged Dental Curriculum: A Rural Indigenous Outplacement Programme. Journal of public health research. 2016;5(1):668 10.4081/jphr.2016.668 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson GE, Blinkhorn AS. Student opinions on a rural placement program in New South Wales, Australia. Rural and remote health. 2011;11(2):1703 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson G, Blinkhorn A. Faculty staff and rural placement supervisors’ pre- and post-placement perceptions of a clinical rural placement programme in NSW Australia. European journal of dental education: official journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe. 2013;17(1):e100–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2012.00768.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson G, Blinkhorn A. The influence of a clinical rural placement programme on the work location of new dental graduates from the University of Sydney, NSW, Australia. European journal of dental education: official journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe. 2013;17(4):229–35. 10.1111/eje.12043 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lalloo R, Evans JL, Johnson NW. Dental care provision by students on a remote rural clinical placement. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2013;37(1):47–51. 10.1111/1753-6405.12009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lalloo R, Evans JL, Johnson NW. Dental students’ reflections on clinical placement in a rural and indigenous community in Australia. Journal of dental education. 2013;77(9):1193–201. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalloo R, Massey W. Simple cost analysis of a rural dental training facility in Australia. The Australian journal of rural health. 2013;21(3):158–62. 10.1111/ajr.12027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoo AM, McNamara KP, Stagnitti KE. Clinical placement and rurality of career commencement: a pilot study. Rural and remote health. 2008;8(3):964 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson VR, Rapana ST, Broughton JR, Seymour GJ, Rich AM. Preliminary findings from the Oranga Niho dental student outplacement project. The New Zealand dental journal. 2015;111(1):6–14. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMillan WB, Foglesong HD. An evaluation of the University of Minnesota summer rural dental externship program. Journal of public health dentistry. 1975;35(4):260–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon CK, Price SS, Jackson J. Predicting Rural Practice and Service to Indigent Patients: Survey of Dental Students Before and After Rural Community Rotations. Journal of dental education. 2016;80(10):1180–7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woronuk JI, Pinchbeck YJ, Walter MH. University of Alberta dental students’ outreach clinical experience: an evaluation of the program. Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 2004;70(4):233–6. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branson BG, Amyot C, Brown R. Increasing access to oral health care in underserved areas of Missouri: dental hygiene students in AHEC rotations. Journal of allied health. 2007;36(1):e47–65. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verma A, Muddiah P, Krishna Murthy A, Yadav V. Outreach programs: an adjunct for improving dental education. Rural and remote health. 2016;16(3):3848 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibiyemi O, Taiwo JO, Oke GA. Dental education in the rural community: a Nigerian experience. Rural and remote health. 2013;13(2):2241 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podshadley AG, Burkett HN, Kleier DJ. A clinical field-experience for fourth-year dental students. Journal of public health dentistry. 1969;29(1):27–35. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heise AL, Mullins MR, Hill CJ, Crawford JH. Meeting the dental treatment needs of indigent rural children. Health Services Reports. 1973;88(7):591–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Mier E, Soto-Rojas A, Stelzner S, Lorant D, Riner M, Yoder K. An International, Multidisciplinary, Service-Learning Program: An Option in the Dental School Curriculum. Education for Health. 2011;24(1):259-. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shreve WB Jr., Clark LL, McNeal DR. An extramural dental education program in a rural setting in Florida. Journal of community health. 1989;14(1):53–60. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.RIDE: UWSOD Regional Initiatives in Dental Education 2015 [08 Aug 2016]. https://dental.washington.edu/ride/.

- 46.Nayar P, McFarland K, Lange B, Ojha D, Chandak A. Supervising dentists’ perspectives on the effectiveness of community-based dental education. Journal of dental education. 2014;78(8):1139–44. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernabe E, Bernal JB, Beltran-Neira RJ. A model of dental public health teaching at the undergraduate level in Peru. Journal of dental education. 2006;70(8):875–83. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okeigbemen SA. Community based dental education and training–case study of a Nigerian dental school. J Dent Specialities. 2016;4(1):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McFarland KK, Reinhardt JW, Yaseen M. Rural dentists of the future: dental school enrollment strategies. Journal of dental education. 2010;74(8):830–5. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulgarelli AF, Roperto RC, Mestriner SF, Mestriner W. Dentistry students’ perceptions about an extramural experience with a Brazilian indigenous community. Indian journal of dental research: official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2012;23(4):498–500. 10.4103/0970-9290.104957 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elkind A, Blinkhorn AS, Blinkhorn FA, Duxbury JT, Hull PS, Brunton PA. Developing dental education in primary care: the student perspective. British dental journal. 2005;198(4):233–7. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812092 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunter ML, Oliver R, Lewis R. The effect of a community dental service outreach programme on the confidence of undergraduate students to treat children: a pilot study. European journal of dental education: official journal of the Association for Dental Education in Europe. 2007;11(1):10–3. 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00433.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scottish Dental Postgraduate Training Fellowship. NHS Education for Scotland, 2014.

- 54.Skinner JC, Massey WL, Burton MA. Rural oral health workforce issues in NSW and the Charles Sturt University Dentistry Program. New South Wales public health bulletin. 2009;20(3–4):56–8. 10.1071/NB08065 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Atchison KA, Crall JJ, Friedman JA, Hewlett ER, et al. Summary and implications of the Dental Pipeline program evaluation. Journal of dental education. 2009;73(2 Suppl):S319–30. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedman JA, Hewlett ER, Atchison KA, Price SS. The Pipeline program at West VIrginia University School of Dentistry. Journal of dental education. 2009;73(2 Suppl):S161–72; discussion S73-4. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thind A, Hewlett ER, Andersen RM, Bean CY. The Pipeline program at The Ohio State University College of Dentistry: Oral Health Improvement through Outreach (OHIO) Project. Journal of dental education. 2009;73(2 Suppl):S96–106; discussion S-7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuthy RA, Woolfolk M, Bailit HL, Formicola AJ, D’Abreu KC. Assessment of the Dental Pipeline program from the external reviewers and National Program Office. Journal of dental education. 2009;73(2 Suppl):S331; discussion S-9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pacza T, Steele L, Tennant M. Development of oral health training for rural and remote aboriginal health workers. The Australian journal of rural health. 2001;9(3):105–10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonsalves WC, Skelton J, Smith T, Hardison D, Ferretti G. Physicians’ oral health education in Kentucky. Family medicine. 2004;36(8):544–6. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrison RL, MacNab AJ, Duffy DJ, Benton DH. Brighter Smiles: Service learning, inter-professional collaboration and health promotion in a First Nations community. Canadian journal of public health. 2006;97(3):237–40. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macnab AJ, Rozmus J, Benton D, Gagnon FA. 3-year results of a collaborative school-based oral health program in a remote First Nations community. Rural and remote health. 2008;8(2):882 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parker EJ, Misan G, Shearer M, Richards L, Russell A, Mills H, et al. Planning, implementing, and evaluating a program to address the oral health needs of aboriginal children in port augusta, australia. International journal of pediatrics. 2012;2012:496236 10.1155/2012/496236 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Summerfelt FF. Teledentistry-assisted, affiliated practice for dental hygienists: an innovative oral health workforce model. Journal of dental education. 2011;75(6):733–42. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burger AD, Boehm JM, Sellaro CL. Dental disease preventive programs in a rural Appalachian population. Journal of dental hygiene: JDH. 1997;71(3):117–22. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Best Practices in Oral Health Promotion and Prevention from Across Europe. Better Oral Health in European Platform, 2015.

- 67.Bhayat A, Vergotine G, Yengopal V, Rudolph MJ. The impact of service-learning on two groups of South African dental students. Journal of dental education. 2011;75(11):1482–8. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bentley JM, Cormier P, Oler J. The rural dental health program: the effect of a school-based, dental health education program on children’s utilization of dental services. American journal of public health. 1983;73(5):500–5. 10.2105/ajph.73.5.500 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feldman CA, Bentley JM, Oler J. The Rural Dental Health Program: long-term impact of two dental delivery systems on children’s oral health. Journal of public health dentistry. 1988;48(4):201–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chandrashekar B, Suma S, Sukhabogi J, Manjunath B, Kallury A. Oral health promotion among rural school children through teachers: an interventional study. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2014;58(4):235–40. 10.4103/0019-557X.146278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parlani S, Tripathi A, Singh SV. Increasing the prosthodontic awareness of an aging Indian rural population. Indian journal of dental research: official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2011;22(3):367–70. 10.4103/0970-9290.87054 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Macnab A, Kasangaki A. ’Many voices, one song’: a model for an oral health programme as a first step in establishing a health promoting school. Health promotion international. 2012;27(1):63–73. 10.1093/heapro/dar039 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tandon S T S, Acharya S, Kaur H. Utilization of mobile dental health care services to answer the oral health needs of rural population. J Oral Health Comm Dent. 2012;6(2):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaakko T, Skaret E, Getz T, Hujoel P, Grembowski D, Moore CS, et al. An ABCD program to increase access to dental care for children enrolled in Medicaid in a rural county. Journal of public health dentistry. 2002;62(1):45–50. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shrestha A, Doshi D, Rao A, Sequeira P. Patient satisfaction at rural outreach dental camps—a one year report. Rural and remote health. 2008;8(3):891 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vashishtha V, Patthi B, Singla A, Gupta R, Malhi R, Pandita V. Patient satisfaction in outreach dental programs of a Dental Teaching Hospital in Modinagar (India). Journal of Indian Association of Public Health Dentistry. 2015;13(3):324–7. 10.4103/2319-5932.165284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vashisth S, Gupta N, Bansal M, Rao NC. Utilization of services rendered in dental outreach programs in rural areas of Haryana. Contemporary clinical dentistry. 2012;3(Suppl 2):S164–6. 10.4103/0976-237X.101076 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okeigbemen SA, Nnawuihe CU. Oral health trends and service utilization at a rural outreach dental clinic, Udo, Southern Nigeria. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 2015;5(Suppl 2):S118–22. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richards L, Symon B, Burrow D, Chartier A, Misan G, Wilkinson D. Undergraduate student experience in dental service delivery in rural South Australia: an analysis of costs and benefits. Australian dental journal. 2002;47(3):254–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Naidu A, Macdonald ME, Carnevale FA, Nottaway W, Thivierge C, Vignola S. Exploring oral health and hygiene practices in the Algonquin community of Rapid Lake, Quebec. Rural and remote health. 2014;14(4):2975 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lo ECM, Chu CH, Wong AHH, Lin HC. Implementing a model school-based dental care service for children in southern China. Hong Kong Dental Journal. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parker EJ, Misan G, Richards LC, Russell A. Planning and implementing the first stage of an oral health program for the Pika Wiya Health Service Incorporated Aboriginal community in Port Augusta, South Australia. Rural and remote health. 2005;5(2):254 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poche Centre for Indigenous Health- 5 Year strategy, Stretegic plan 2016–2020: on Healthy Kids, Healthy Teeth, Healthy Hearts. 2016. http://sydney.edu.au/dam/corporate/documents/news-opinions/Poche_5%20Year%20Strategy_Brochure_FINAL_LowRes.pdf.

- 84.Fricton J, Chen H. Using teledentistry to improve access to dental care for the underserved. Dental clinics of North America. 2009;53(3):537–48. 10.1016/j.cden.2009.03.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Glassman P, Harrington M, Namakian M, Subar P. The virtual dental home: bringing oral health to vulnerable and underserved populations. Journal of the California Dental Association. 2012;40(7):569–77. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dawkins E, Michimi A, Ellis-Griffith G, Peterson T, Carter D, English G. Dental caries among children visiting a mobile dental clinic in South Central Kentucky: a pooled cross-sectional study. BMC oral health. 2013;13:19 10.1186/1472-6831-13-19 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Asawa K, Bhanushali NV, Tak M, Kumar DR, Rahim MF, Alshahran OA, et al. Utilization of services and referrals through dental outreach programs in rural areas of India. A two year study. Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny. 2015;66(3):275–80. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kurtzman C, Freed JR, Goldstein CM. Evaluation of treatment provided through two universities’ mobile dental project Journal of public health dentistry. 1974;34(2):74–9. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1974.tb00681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.SAN-CAR—mobile dental healthcare provided to rural communities in Romania and Bulgaria: European Commission; 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/romania/san-car-mobile-dental-healthcare-provided-to-rural-communities-in-romania-bulgaria.

- 90.The S-Miles To Go Mobile Dental Program 1997 [updated 17 Jan 2017; cited 10 Nov 2016]. http://dental.buffalo.edu/CommunityOutreach/MobileDentalVan.aspx.

- 91.Arevalo O, Chattopadhyay A, Lester H, Skelton J. Mobile dental operations: capital budgeting and long-term viability. Journal of public health dentistry. 2010;70(1):28–34. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00140.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goel P, Goel A, Torwane NA. Cost-efficiency of indigenously fabricated mobile-portable dental unit in delivery of primary healthcare in rural India. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 2014;8(7):Zc06–9. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8351.4534 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.World HEalth Organisation. Monitoring the geographical distribution of the health workforce in rural and underserved areas. Geneva: Department of Human Resources for Health, World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Orpin P, Gabriel M. Recruiting undergraduates to rural practice: what the students can tell us. Rural and remote health. 2005;5(4):412 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.