Traumatic brain injury (TBI) offers a unique opportunity to examine amyloid‐beta (Aβ) pathology since the moment of head trauma is the triggering event of aberrant Aβ genesis. This commentary highlights a study by Abu Hamdeh and colleagues in this issue of Brain Pathology (xxx) in which the authors show surprisingly rapid formation of amyloid oligomers and protofibrils within hours of severe TBI, with higher levels of these potentially toxic Aβ species found in individuals with the APOE e4 genotype. This study provides a window into the very early events of amyloid pathogenesis after TBI, and serves as a platform for future studies to follow the temporal mischief that the Aβ species wreak in the injured brain.

Long recognized as a hallmark pathology of Alzheimer's disease (AD), plaques composed of amyloid‐beta (Aβ) peptides are now widely acknowledged as a common consequence of both acute and late survivals from traumatic brain injury (TBI) 1. However, while in all practical terms it is impossible to determine the precise time of onset of abnormal amyloid processing in AD, in contrast, for TBI the moment of head trauma is essentially “time zero” as the triggering event of aberrant production of Aβ peptides. As such, TBI provides a unique opportunity to study the processes contributing to abnormal Aβ pathologies in neurodegeneration.

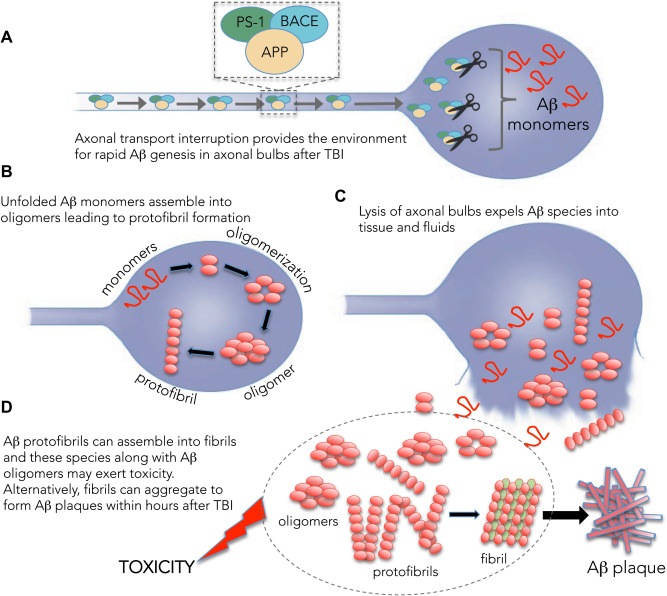

Previous studies using autopsy acquired or surgically excised tissues have shown that moderate to severe levels of TBI can trigger the formation of diffuse plaques in approximately 30% of individuals 2, 3, 4, 5; risk in turn influenced by genetic susceptibility (APOE and neprilysin polymorphisms) 6, 7. Remarkably, these plaques can form within hours of injury, even in young individuals. While the sources of Aβ genesis following TBI remain to be fully characterized, diffuse axonal injury (DAI) presents a strong candidate 8. Common to all severities of TBI, DAI results in axonal transport interruption leading to massive accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and its cleavage enzymes in axonal swellings in stereotypical locations throughout the white matter. In this pathological milieu, Aβ is thought to be cleaved from APP, with the resulting Aβ reservoir released by lysis of the injured axons 9 (Figure 1). However, the ensuing events leading to Aβ aggregation and the rapid deposition of diffuse plaques or other pathological mischief have only been partially explored 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

In this issue of Brain Pathology, Abu Hamdeh and colleagues provide striking insight into post‐TBI amyloid pathogenesis. Particularly laudable in their study is the use of human brain tissue acquired during surgical intervention from 12 patients with severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale 8 or less), thereby providing samples for parallel immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses in many of their cases. While this number of subjects is understandably small due to the unique source, the findings are nonetheless compelling. As with earlier studies in amyloid post‐TBI, this group observed plaque pathology in the excised tissue shortly after injury in around a third of the case material they examined. However, for their biochemical examinations on these as well as the apparently “non‐plaque” cases, the authors report the first evidence of rapid accumulation of Aβ oligomers and protofibrils in a matter of just hours after injury. Notably, while these soluble Aβ aggregates are thought to be integral to AD pathogenesis 15, pushing the disease to progress over many years, this new study demonstrates that these potentially toxic Aβ species can form extremely rapidly after TBI. As such, their appearance perhaps provides a substrate for the initiation or acceleration of processes leading to late post‐TBI neurodegeneration, which might provide insight to similar pathways driving AD.

Interestingly, in common with previous studies in amyloid plaque deposition after TBI, the authors found an association between appearance of these Aβ oligomers and protofibrils and APOE genotype 6, 7. Specifically, higher levels of Aβ species were detected in patients with the high risk APOE ɛ4 allele (in this series all ɛ3/ɛ4 genotype), known to be more prone to developing Aβ plaques after TBI, than in non‐ɛ4 carriers. Since it remains unknown whether the there is an increased generation of Aβ or decreased capacity to clear it, further biochemical and genetic analyses are warranted to further elaborate on this observation. For example, this appearance of increased amyloid pathologies after TBI in APOE ɛ4 carriers may reflect a decreased capacity to traffic Aβ. It would also be interesting to examine the role of the Aβ degrading enzyme, neprilysin, and polymorphisms of its gene in this population of cases 6.

Aβ oligomers and protofibrils are implicated in a growing number of pathological processes, such as interrupting long‐term potentiation and memory function and increasing inflammation 16, 17, 18, 19. As such, their processing to and deposition as plaques might conceivably represent an amyloid pathology of lesser concern, since the otherwise toxic Aβ species are literally “bound up (Figure 1).” Nonetheless, acute plaque formation does not appear to be the final chapter as TBI has been shown to be an “injury that keeps on taking.” Indeed, approximately 30% of patients go on to have progressive neuropathological processes, including the late re‐emergence of widespread amyloid plaque pathologies and further protein misfolding pathologies, including striking pathologies in tau, and persistent and evolving neuroinflammation; pathologies common to many neurodegenerative diseases 1, 20, 21. Therefore, as this work illustrates, TBI provides an intriguing and informative platform to explore events springing from “time zero” that are directed toward identifying candidate pathological processes responsible for converting an initial traumatic event into a progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Figure 1.

One potential source for rapid genesis of amyloid‐beta (Aβ) species after traumatic brain injury (TBI). A. Widespread damage to axons induces transport interruption and accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the secretases, PS‐1 and BACE that can cleave it to form Aβ peptides within axonal swellings. B. Accumulating Aβ assembles into oligomers and protofibrils, that are (C) released into the brain when the axonal bulb is lysed. D. Free Aβ oligomers, protofibrils and developing fibrils may exert toxicity to the brain and/or form plaques that can be observed within hours after TBI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (NS038104, NS092389, NS09003 and EB021293).

References

- 1. Smith DH, Johnson VE, Stewart W (2013) Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat Rev Neurol 9:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roberts GW, Gentleman SM, Lynch A, Graham DI (1991) beta A4 amyloid protein deposition in brain after head trauma. Lancet 338:1422–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith DH, Chen XH, Iwata A, Graham DI (2003) Amyloid beta accumulation in axons after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg 98:1072–1077. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeKosky ST, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Paljug WR, Wisniewski SR, Clark RSB, Ikonomovic MD (2007) Association of increased cortical soluble abeta42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch Neurol 64:541–544. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts GW, Gentleman SM, Lynch A, Murray L, Landon M, Graham DI (1994) Beta amyloid protein deposition in the brain after severe head injury: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicoll JA, Roberts GW, Graham DI (1995) Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele is associated with deposition of amyloid beta‐protein following head injury. Nat Med 1:135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Graham DI, Stewart JE, Praestgaard AH, Smith DH (2009) A neprilysin polymorphism and amyloid‐beta plaques after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 26:1197–1202. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008-0843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2013) Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 246:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2010) Traumatic brain injury and amyloid‐beta pathology: a link to Alzheimer's disease? Nat Rev Neurosci 11:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrn2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marklund N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Ronne-Engstrom E, Enblad P, Hillered L (2009) Monitoring of brain interstitial total tau and beta amyloid proteins by microdialysis in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 110:1227–1237. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mondelo S, Buki A, Barzo P, Randall J, Provuncher G, Hanlon D, Wilson D et al (2014) CSF and plasma amyloid‐beta temporal profiles and relationships with neurological status and mortality after severe traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 4:6446. doi: 10.1038/srep06446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magnoni S, MacDonald CL, Esparza TJ, Conte V, Sorrell J, Macri M, Bertani G et al (2015) Quantitative assessments of traumatic axonal injury in human brain: concordance of microdialysis and advanced MRI. Brain 138:2263–2277. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gatson JW, Warren V, Abdelfattah K, Wolf S, Hynan LS, Moore C, Diaz-Arrastia R et al (2013) Detection of beta‐amyloid oligomers as a predictor of neurological outcome after brain injury. J Neurosurg 118:1336–1342. doi: 10.3171/2013.2.JNS121771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brody DL, Magnoni S, Schwertye KE, Spinner ML, Esparza TJ, Stocchetti N, Zipfel GJ et al (2008) Amyloid‐beta dynamics correlate with neurological status in the injured human brain. Science 321:1221–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1161591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang T, Li S, Xu H, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ (2017) Large soluble oligomers of Amyloid beta‐protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate. J Neurosci 37:152–163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM et al (2008) Amyloid‐beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paranjape GS, Gouwens LK, Osborn DC, Nichols MR (2012) Isolated amyloid‐beta(1–42) protofibrils, but not isolated fibrils, are robust stimulators of microglia. ACS Chem Neurosci 3:302–311. doi: 10.1021/cn2001238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O'Nuallain B, Freir DB, Nicoll AJ, Risse E, Ferguson N, Herron CE, Collinge J et al (2010) Amyloid beta‐protein dimers rapidly form stable synaptotoxic protofibrils. J Neurosci 30:14411–14419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3537-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartley DM, Walsh DM, Ye CP, Diehl T, Vasquez S, Vassiley PM, Teplow DB et al (1999) Protofibrillar intermediates of amyloid beta‐protein induce acute electrophysiological changes and progressive neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. J Neurosci 19:8876–8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2012) Widespread tau and amyloid‐beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol 22:142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00513.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W et al (2013) Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136:28–42. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]