Abstract

Advances in immune profiling techniques have dramatically changed the immune-oncology treatment and monitoring landscape. High-throughput protein and gene expression technologies have paved the way for the discovery of therapeutic targets and biomarkers, and have made monitoring therapeutic response possible through the ability to independently assay the phenotype, specificity, exhaustion status and lineage of single T cells. Although valuable insights into response profiling have been gained with current technologies, it has become evident that single method profiling is insufficient to accurately capture an anti-tumor T cell response. We discuss and propose new methods which combine multiple axes of analysis to provide a comprehensive analysis of T cell repertoire in the fight against cancer.

Keywords: Immune repertoire, Profiling, T Cell, ICPB

The T Cell Repertoire and Tumor Immunity

Immunotherapy plays a critical role in the modern treatment of both solid and blood tumors. As the field matures, a diverse range of therapeutics that harness T cell cytotoxicity are used in the fight against cancer, from personalized vaccines[10] and oncolytic viruses[11], to immune checkpoint blockade[12] and adoptive cell transfer therapy[13]. As T cells take the center stage of cancer immunotherapy, a deep understanding of T cell’s intrinsic properties and their responses to extrinsic environment are important to new therapy development and treatment monitoring. Immune cell repertoire profiling that aims to evaluate immune receptor composition, antigen specificity and cross-reactivity, and functional and activation status of the antigen receptor expressing cells is one research area that holds promise for biomarker and immune signature discovery with the potential to aid in patient stratification as well as in target discovery and therapeutic development.

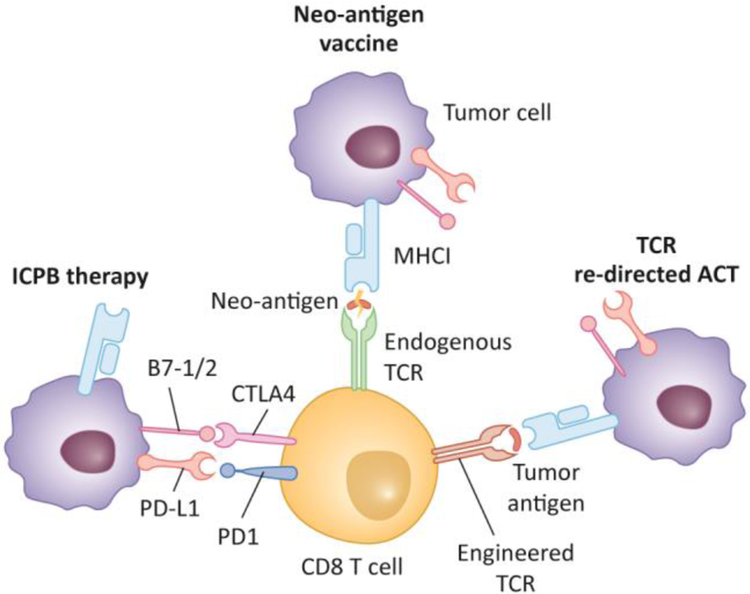

In this opinion, we will focus on repertoire profiling of CD8+ T cells, which are able to directly enact anti-tumor immunity given antigen recognition through their unique TCR [14, 15]. Collectively, the CD8+ TCR repertoire determines an individual’s ability to respond to diverse antigens quickly and effectively. This endogenous immunity is the basis for therapies relying on the patient’s own immune system, including vaccines and immune checkpoint blockade (ICPB, Figure 1). Additional therapies introduce new immunity using receptor-engineered T cells to target tumor antigens. Therefore, being able to quantify the completeness and functional competence of this repertoire is important to identify patients that are most likely to benefit from a specific immunotherapy. Assessing these characteristics requires profiling highly heterogeneous T cell populations on the single cell level, in a high-throughput manner. Comprehensive and multi-faceted T cell profiling is therefore critical to improve the success and safety of current T cell based immunotherapy, as well as in developing new strategies in this area.

Figure 1. T cell based cancer immunotherapies.

Current cancer immunotherapies include (1) immune checkpoint blockade (ICPB) by blocking suppression effects of T cell inhibitory molecules; (2) Neo-antigen vaccine by stimulating T cells that recognizing neo-antigen expressing tumor cells, and (3) TCR re-directed adoptive cell transfer (TCR-ACT), by engineering autologous T cells to recognize specific cancer antigens and infuse them back to patients to fight cancer cells.

T Cell Profiling in Cancer Therapeutics

T cell-based immunotherapies operate upon one of two main premises: inhibition of the suppressing factors to endogenous anti-tumor immunity or the induction of new anti-tumor immunity. Despite their differences, each technique discussed below relies upon the specific interaction between an effector cell and its cognate, tumor-associated antigen. Understanding and characterizing the downstream transcriptomic and epigenetic changes that these therapies have on T cells is key to improving treatment efficacy and to identifying new therapeutics.

Immune checkpoint blockade therapy

ICPB therapy has revolutionized the treatment of many solid[12] and blood[16] cancers, and is one of the most successful, off-the-shelf cancer therapies to date. ICPB uses antibodies to block T cell inhibitory molecules, such as PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4, to reinvigorate existing T cells without regard to specificity (Figure 1). This is often seen as ‘taking the brakes off’ of the immune system and can result in polyclonal reinvigoration of cellular anti-tumor immunity[17]. Approximately 20–30% of patients achieve an objective response with single ICPB, although this varies between disease types, and combination therapy can achieve a higher response rate[18, 19]. Regardless of patient outcome, ICPB also activates T cells that are not tumor-specific, which can result in autoimmune off-tumor toxicity that ranges from skin depigmentation (vitiligo) to severe myocarditis resulting in cardiac death[20].

Toxicity resulting from ICPB has driven research into pretreatment or early-treatment patient stratification methods to determine which patients are most likely to achieve objective response[21, 22]. Early stratification methods used single-molecule expression or simple metrics to predict patient response to ICPB[23]. Tumor PD-L1 expression, mutation rate and predicted neoantigen burden were proposed and studied for this purpose, but were not robust in their prediction of patient outcome. Because ICPB relies upon a highly diverse set of effector cells, high-throughput profiling methods are needed to quickly and accurately assess the state of response.

Neo-antigen based vaccine

Like ICPB, anti-tumor vaccines often rely upon a highly diverse immune response to elicit tumor recession. Neo-antigen vaccines in particular attempt to bolster the immune response by increasing the awareness of the immune system to specific, aberrant proteins found within the tumor[24]. It is hypothesized that because neo-antigens are not part of the host proteome, the thymic negative selection process preserves T cells bearing high-affinity T cell receptors towards neo-antigens[25, 26]. Administering a mixture of neo-antigens as a therapeutic vaccine should stimulate functional T cells to execute cytotoxicity toward neo-antigen expressing cancer cells.

Three studies [24, 27, 28], independently demonstrated the feasibility and therapeutic potential of selecting personalized neo-antigens and using them as therapeutic vaccines. All three studies performed extensive analysis to identify a set of personalized neo-antigens, which were then injected into the respective patients. All groups demonstrated vaccine-related complete and/or partial objective responses. Interestingly, in two of the studies, there were patients who relapsed, but subsequently achieved complete response after anti-PD-1 was added to the treatment. The necessity of the PD-1 blockade demonstrates that presence of tumor-responsive T cells and their awareness of the antigen is not sufficient to always elicit tumor rejection. Thus, other metrics are needed to quantify the ability of the patient’s immune system to respond to similar treatment.

Adoptive cell transfer therapy

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) therapies physically introduce anti-tumor immunity by intravenous infusion of large quantities of tumor-reactive T cells[13]. The infused cells are generated in one of two ways: expansion of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs, TIL-ACT) or genetic redirection of autologous T cells by TCR transduction (TCRACT). In recent years, the therapeutic potential of ACT therapy has been demonstrated in colorectal cancer (CRC)[29, 30], synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma[31, 32] and breast cancer[33] among others.

As a therapy, TIL-ACT is cumbersome: it requires substantial tumor resection prior to therapy, an intensive search for tumor antigen-specific TILs, and a long outgrowth period[13]. However by using immune profiling of the infusion product and direct TIL isolate, much can be learned about the endogenous anti-tumor response in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. On the other side, TCR-ACT is less constrained by patients’ own T cells, because it can use tumor antigen-specific TCRs identified from other sources[34]. These TCRs can be introduced to T cells isolated from patients’ peripheral blood. Two main challenges have prevented the extensive use of TCR-ACT: discovery of robust, immunogenic tumor antigens and rapid identification of therapeutic TCRs. These represent areas where integrated T cell profiling technologies could impact patient care (below).

Single Axis T Cell Repertoire Profiling

Studies on T cell repertoire profiling often focus upon single axis to parse out information about TILs and peripheral T cells. Key technologies here use immune repertoire sequencing technologies, mass cytometry (CyTOF) or single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to examine the T cell clonal expansion, activation and phenotype.

T cell receptor repertoire sequencing

Recently, we[35, 36] and others[37] developed several second generation immune repertoire sequencing technologies that use molecular identifier (MID) to reduce sequencing and PCR errors that are common to the first generation of immure repertoire sequencing[38–40]. This approach reduces error from more than 1 nucleotide in every TCR sequence to 1 nucleotide in 150 TCRs. Immune repertoire sequencing has been used to show that the clonal diversity index of mucosal TCR repertoire predicts prognosis in gastric cancer[41]. Others[42] examined the TCR intratumor heterogeneity in lung adenocarcinomas and established the correlation between high degrees of TCR intratumor heterogeneity and increased risk of postsurgical relapse and shorter disease-free survival. Another study showed that a less diverse and more clonally expanded TCR repertoire in pre-treatment tissue significantly correlated with clinical response to anti-PD-1 treatment in advanced melanoma patients[43].

Development in informatics to piece out TCR and BCR sequences from bulk RNA sequencing data enables TCR repertoire analysis from existing large cohorts of sequencing data, which potentially could have a predictive power to disease prognosis. This analysis showed that public TRCs are common in tumors[44], which is consistent with another study using HLA-A2+ patient sample[45] that suggested that aside from neo-antigens, T cells recognizing shared antigens are also prevalent. Other studies went a step further and identified potential immunogenic somatic mutations on the basis of their co-occurrence with CDR3 sequences[46, 47]. More recently, an improved algorithm was developed to extract TCR and BCR sequence information from bulk RNA sequencing data[48], revealing that high intratumoral immunoglobulin heavy chain expression levels were associated with longer survival.

Single cell gene expression and phenotypic profiling of T cells

Using scRNA-seq, several groups have documented heterogeneity of TILs in both mice[49, 50] and humans[51–53] for different tumor types. Dysfunction is a common feature of TILs and the gene modules for TIL dysfunction and activation are enriched in different TIL subpopulations. CyToF[54] analysis echoes scRNA-seq results on heterogeneity of TIL gene expression. In-depth studies in both humans and mice showed that anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 treatments target different subsets of TILs and that they induce immune responses by distinct cellular mechanisms[55].

Two studies have used CyToF in combination with other methods to examine possible biomarkers in the peripheral blood of stage IV melanoma patients before anti-PD-1 treatment that can be used to predict responders from non-responders. These two studies, however, generated two different sets of biomarkers. Huang et al. [56] showed that despite that most patients demonstrated an immunological response to anti-PD-1 treatment, the magnitude of circulating exhausted CD8 T cell reinvigoration and tumor burden correlated with clinical response. Also examining the peripheral blood samples, Krieg et al.[57] found that the frequency of CD14+CD16−HLA-DRhi monocytes is a strong predictor of progression-free and overall survival in response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Two recent studies used scRNA-seq and examined 12,346 and 6,311 TILs respectively. Guo et al.[58], found that while the ratio of “pre-exhausted” to exhausted T cells was positively correlated with better prognosis, enrichment of the gene signature of activated tumor regulatory T cells correlated with poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. However, Sava et al.[59], showed that the gene signature of CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells was associate with improved survival. These different prognosis factors reflect the complexity of the anti-tumor T cell response as well as the difference between sampling blood and TIL.

Neo-antigen based immune profiling

Early studies in mice[60] and humans[61] showed that tumor mutations are important targets for ICPB, which led to the hypothesis that it may work the best in tumors with high mutation burden[26]. Studies in melanoma[62] and non-small cell lung cancer[63] supported this hypothesis. In addition, it was found that patients with mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer are more responsive to immune checkpoint blockade therapy than patients with mismatch repair proficient colorectal cancer[64]. Recently, this observation was extended to 11 other solid tumor types[65]. These studies demonstrate that mutational load was associated with the degree of clinical benefit but was not sufficient to predict benefit alone.

Integrated Repertoire Analysis Technologies

Technology development has made it possible to pair information on two different axes in single cells, such as linking TCR affinity with TCR sequences and pairing TCR sequences with antigen specificity and cross-reactivity.

Antigen-specific TCR affinity and receptor sequence profiling

MHC multimers[15, 66] have long enabled detection of antigen-specific T cells from patient tissues and peripheral blood. However, tetramer staining intensity is not well-correlated with T cell function[67] while TCR affinity is[68]. Traditionally, TCR affinity has been quantified in solution (three dimensional, 3D affinity) by surface plasmon resonance method, such as Biacore, which involves labor intensive generation of soluble TCR and pMHC. More recently, we[67, 69, 70] and others[71] have shown that TCR affinity measured at the interface of T cell and antigen presenting cell, which is referred to as 2-dimensional (2D) affinity, correlates better with T cell function compared with TCR affinity obtained in solution. Thus, 2D TCR affinity could be used to identify therapeutic TCRs. However, the traditional 2D TCR affinity measurement technologies are low-throughput and are optimum for therapeutic TCR discovery. We developed an in situ TCR Affinity and Sequence Test[67], iTAST, that can measure 2D TCR affinity on individual human primary T cells and at the same time obtain its TCR sequences. With a throughput of 75 cells per day, iTAST can be used to find TCRs of any specified 2D affinity and potentially increasing the speed of the discovery of therapeutic TCRs.

TCR sequence and antigen specificity pairing

Until recently, large scale assessment of TCR antigen specificity and cross-reactivity in TILs and other T cells has been experimentally challenging. We recently made contributions to expand knowledge in this particular area through the development of a new technology to link antigen specificity to TCR sequences on thousands of single T cells for hundreds of peptides simultaneously[72]. We named it TetTCR-Seq for Tetramer associated TCR Sequencing. We achieved this by using DNAs to label pMHC tetramer specificities[73] instead of fluorophore[66, 74] or heavy metal ion labels[75], thus drastically expanding the number of antigen species that can be interrogated at once as well as the number of bound antigen species on single T cells. The ability to detect multiple species of pMHC binding onto the same T cell enables the detection of TCR cross-reactivity.

We have demonstrated the advantage of linking antigen specificity with TCR sequences in studying the potential of neo-antigen recognizing TCRs to cross-react to wildtype antigen counterparts. Using published and experimentally validated neo-antigens, we showed that neo-antigen-recognizing TCRs that cross-react to wild type antigen counterparts are prevalent. TetTCR-Seq therefore enables the identification of neo-antigens that are capable of inducing wild type cross-reactive T cells as well as the identification of neo-antigen specific TCRs that are not cross-reactive and are of potential therapeutic value.

High-throughput Integrated Single T Cell Profiling is the Future

A recent case study[33] demonstrated drastic changes in TCR repertoire when comparing between in vitro expanded, neoantigen-recognizing TILs and the TCRs that can be detected in peripheral blood six weeks after infusion. Antigen-specificities that were nearly undetectable at infusion were represented by dominant clonotypes after six weeks. Furthermore, some of these same clonotypes were those present in high quantities before in vitro expansion, suggesting a degree of reversion to the original TIL repertoire. These dynamic composition changes of TCR repertoire are likely to be shaped by the antigen expression pattern in cancer cells and the suppressive tumor microenvironment, thus highlighting the importance of a comprehensive understanding of these interactions in directing therapy.

High-throughput gene expression analysis of tumors enables the use of computational models to address major scientific questions about tumor immunogenicity. For example, a recent study predicted the immunogenicity of neoantigens by combining the likelihood of neoantigen presentation by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and the probability of recognition by T cells[21]. In this study, the authors developed a neoantigen fitness model that predicted tumor response to ICPB. Part of this model relies upon the assumption that a neoantigen is more likely to be recognized by T cells if it is highly similar to known peptides in Immune Epitope Database (IEDB)1. The positive correlation observed under this assumption could have several implications: responding TCRs could be cross-reactive to a foreign antigen or that certain peptide characteristics result in more robust immune responses. Thus, we identify a need for a comprehensive understanding of how tumor-associated epitopes and their expression impacts recognition by TILs. TIL repertoire profiling in a high-throughput manner, such as TetTCR-Seq, will provide critical knowledge to the relationship between antigens and TCR repertoire in cancer immunology and will be a useful approach to select therapeutic candidates in cancer immunotherapy.

As discussed above, the suppressive tumor microenvironment also impacts the function and differentiation state of T cells. The clinical benefit of CTLA-4 and PD-1 or PD-L1 in some cancers has motivated the search for new ICPB targets and the testing of ICPB combinations. Despite many positive outcomes, the wide range of detrimental side effects associated with ICPB demands new metrics that can be used to correlate and eventually predict patients’ response before therapy. Studies using scRNA-seq or CyToF on TILs found that independent sets of immune parameters on different T cell subsets could be used to correlate patient benefit with immune checkpoint blockade[55, 57, 59]. Despite these improvements, many patients cannot be accurately stratified and most metrics are not widely applicable to all cancer types.

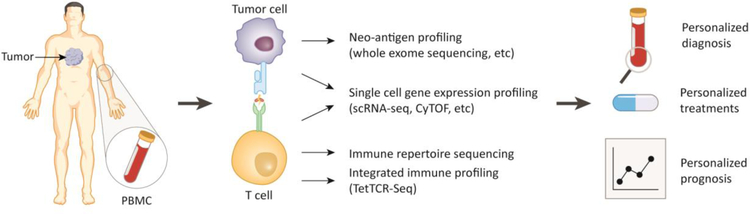

We propose that a high-throughput technology that provides a comprehensive evaluation of a patient’s T cell repertoire in terms of antigen-specificity, T cell phenotype, activation/exhaustion status, and T cell clonal expansion could provide new knowledge for patient stratification and be directly used for ICPB patients. This technology would extensively profile the T cell repertoire in patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade therapy to learn what metrics constitute a good response first, then to predict ICPB efficacy (Figure 2). As previously discussed, neo-antigen vaccines have been shown to have therapeutic value in melanoma and mutational load has been correlated with clinical benefit of immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma and other types of cancer[26]. Thus, neo-antigen specific T cells are an attractive effector in the fight against cancer. A recent study however, showed that TILs recognizing non-tumor antigens are much more prevalent compared to TILs recognizing neo-antigens or tumor associated antigens in both lung and colorectal cancer[76]. It is possible that the lack of tumor-specific T cells found in this study resulted from the unique characteristics of colorectal and lung cancer, although lung cancer is also believe to harbor high amount of mutations[26]. It is also possible that the neo-antigen search space is limited by the number of pMHC can be tested.

Figure 2. Benefits of T cell repertoire profiling in cancer immunology and immunotherapy.

Current methods of T cell repertoire profiling from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) include neo-antigen profiling, single cell gene expression profiling, and immune repertoire profiling. An integrated immune profiling that combines above all aspects can help to guide a personalized diagnosis, treatment plans and prognosis.

The proposed integrated T cell profiling technology would advance our understanding of the interaction between cancer and the immune system. The high-throughput pMHC screening capacity of the integrated technology could offer a near exhaustive screening of all personalized neo-antigens from individual patients while the scRNA-seq aspect of the technology could provide an in-depth analysis TIL functional and activation/exhaustion state. scRNA-seq is especially advantageous in its quantification of transcription factors, which may have more predictive power on cell state compared to surface markers as suggested by a the recent Tabula Muris project[77]. For example, it is possible that neo-antigens recognizing T cells constitute the majority of TILs, and that they are the cells that proliferate extensively and are most exhausted, as hypothesized from other scRNA-seq only studies. However, it is also possible that these T cells recognizing cancer antigens or foreign antigens are cross-reactive to cancer neo-antigens that could not be evaluated by current technologies.

This integrated T cell profiling approach could also be used to identify therapeutic neo-antigens and/or TCRs as the function and activation status of neo-antigen recognizing T cells from patients would provide clues as to whether the predicted antigens are indeed expressed by cancer cells, which is an area lacking high-throughput technology development. Finally, this integrated T cell profiling approach could also provide a way to monitor cancer immunotherapy and direct personalized therapeutic regimens. For example, in ACT therapy, it could be used to monitor the expression of immune checkpoint molecules and then single or multiple ICPBs could be used in addition to the original ACT therapy. In other settings, patients resistant to ICPB therapy could be tested for the existence of T cells targeting dominant cancer antigens using this integrated therapy. If the T cell frequency to these dominant cancer antigens are low, in vitro expanding them or engineering patients’ T cells to express therapeutic TCRs could be applied to the personalized regimen.

Concluding Remarks

By combining TetTCR-Seq with scRNA-seq and other technologies, we could accurately and comprehensively profile antigen specificity, activation/exhaustion, and clonal expansion of TILs, which are parameters essential to distinguish individual T cells. A comprehensive understanding these characteristics of T cells could, in theory, be applied to predict responders before patients receive immune checkpoint blockade therapy or it would yield simple markers for patient stratification that is more clinic friendly. As tumors continue to evolve under the pressure from the immune system, it is essential to profile both the infiltrating T cells and the tumor microenvironment for comprehensively understand the interaction between tumor and T cells in order to develop new immunotherapies and diagnostic tools.

Resources

Highlights.

Bulk TCR and single cell TCR repertoire analysis can provide T cell clonal expansion information

Single cell RNA sequencing and CyTOF can provide cell phenotype and functional status analysis of T cells

DNA-barcoded pMHC tetramers enable high-throughput screening of T cell antigen specificity

Integrating TCR antigen specificity, TCR sequences, T cell phenotype and functional status at single cell level would provide comprehensive T cell profiling, which is critical for T cell based cancer immunotherapy and monitoring.

Outstanding Questions.

What parameters are essential to distinguish individual T cells?

How would comprehensive T cell profiling help cancer diagnosis and treatment?

How can we develop high-throughout, comprehensive profiling techniques for use in research and in the clinic?

Immune Repertoire Characteristics (Text box #1).

Immune Receptor Repertoire – T cells and B cells are able to recognize a large and diverse pool of antigens through their immune receptors. During cellular development, these receptors go through variable, diversity and joining (VDJ) region recombination which enables a potential 1018 unique receptors for T cells and 1013 for B cells[1]. Despite the theoretical possibilities, current estimates place the peripheral diversity in an adult human to be approximately 2×107 unique T cell receptors (TCR) at a given time[2]. The immune repertoire refers to the identities and distribution of these immune receptors present in an individual at a given time.

Immune Cell Repertoire – The cellular repertoire differs from its receptor counterpart by including cellular characteristics. These may include phenotype, activation status, transcriptomic profiling or more recently, epigenetic analysis at the single cell level.

Clonality – When T cells proliferate, their unique TCR sequence is passed to both daughter cells. Thus, the number of T cells bearing the same TCR or their relative fraction can be used to make assumptions about how much that unique T cell or “clone” has proliferated. This can give insight into infection status and the presence of a given antigen.

Antigen Specificity and Cross-reactivity – The individual molecular characteristics of a TCR dictate which antigens it will bind well to and those it will not. Traditionally, only one antigen is associated with a particular TCR, known as TCR antigen specificity. High-throughput screening enabled the detection of multiple antigens that can be bound to the same TCR. These antigens are referred to as TCR cross-reactivity.

Repertoire Completeness – The collection of individual’s TCR repertoire that is able to cover all possible antigens is referred to as repertoire completeness. Repertoire completeness is important to individual’s ability to fight infection and other diseases but is difficult to evaluate due to the lack of high-throughput technologies.

Receptor Affinity – The strength of the interaction between a TCR and its ligand can be referred to as TCR:pMHC affinity. This can be measured using two-dimensional (on cell membrane), three-dimensional (in solution) or indirect affinity measurement methods. We and others have demonstrated correlations between affinity and in vitro functional capacity, which could have impact on adoptive cell transfer therapies.

T Cell Exhaustion – Repeated antigen exposure combined with inhibitory signaling results in loss of T cell functionality. This loss begins as a reversible quality, but over time becomes a cellular state, featured by certain epigenetic modifications, which cannot be overcome using inhibitory molecule blockade such as anti-PD-1 antibodies. Exhausted T cells can be identified by their lack of functionality and expression of inhibitory molecules including Tim-3, LAG3, TIGIT and PD-1.

Neoantigen – Somatic mutations within a tumor can produce altered protein segments that are tumor-restricted. Missense, nonsense and stop-loss mutations that alter the amino acid sequence can produce neoantigens. Recent studies have also pointed to chromosomal fusions and intron retention as potential sources of neoantigens.

High-throughput immune profiling methods (Text box #2).

Immune Repertoire Sequencing – This refers to using various next-generation sequencing platforms to quantify the composition of different kinds of B cell receptor (BCR) or TCR sequences in a sample. The measurement can be done on either single or paired chains[3]. During B cell clonal expansion, BCRs gradually alter their sequences through somatic hypermutation and by selective advantage, change the relative abundance of each B cell clone. TCR sequences remain unchanged but their abundance through clonal selection may change according to proliferation. Thus, analyzing these diversity and abundance changes of BCRs and TCRs using immune repertoire sequencing can help to evaluate clonal alteration and lineage development of B and T cells in the context of infection, vaccination, autoimmune disease, and cancer.

Cytometry by Time of Flight (CyTOF) – CyTOF is a cytometry method that uses antibodies tagged with rare heavy metal ions instead of fluorescent molecules to assess protein marker expression on the single cell level. After antibody staining, the cells are individually atomized and ionized. The masses corresponding to the heavy metal tags are counted in discrete time-separated detector channels. The minimal overlapping of mass among these heavy metal tags, enables CyTOF to analyze of more than 40 different protein targets on single cells in a sample[4].

Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) – Characterization of transcribed genes on a single-cell level through sequencing of total poly-A+ mRNAs. scRNA-seq has evolved from in-tube methods[5–9] to high-throughput methods including microfluidic chip-based and droplet-based single cell transcriptome amplification. These allow for processing the sample in bulk, but result in reads that can be attributed back to single cells. scRNA-seq has been useful in identifying rare cell populations, studying the development of tissues and organisms, and comparing phenotypes and functions between cell populations among others.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS

N.J. is a scientific advisor for ImmuDX LLC and Immune Arch Inc

References:

- 1.Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M, & Janeway C (2012) Janeway’s Immunobiology, 8th edn., Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arstila TP et al. (1999) A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science 286 (5441), 958–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedensohn S et al. (2017) Advanced Methodologies in High-Throughput Sequencing of Immune Repertoires. Trends Biotechnol 35 (3), 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitzer MH and Nolan GP (2016) Mass Cytometry: Single Cells, Many Features. Cell 165 (4), 780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang F et al. (2009) mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods 6 (5), 377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam S et al. (2011) Characterization of the single-cell transcriptional landscape by highly multiplex RNA-seq. Genome Res 21 (7), 1160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimshony T et al. (2012) CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell Rep 2 (3), 666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picelli S et al. (2013) Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat Methods 10 (11), 1096–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashimshony T et al. (2016) CEL-Seq2: sensitive highly-multiplexed single-cell RNASeq. Genome Biol 17, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Z et al. (2018) Towards personalized, tumour-specific, therapeutic vaccines for cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 18 (3), 168–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman HL et al. (2015) Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14 (9), 642–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribas A and Wolchok JD (2018) Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 359 (6382), 1350–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klebanoff CA et al. (2016) Prospects for gene-engineered T cell immunotherapy for solid cancers. Nat Med 22 (1), 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis MM and Bjorkman PJ (1988) T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature 334 (6181), 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PP et al. (1999) Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med 5 (6), 677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armand P (2015) Immune checkpoint blockade in hematologic malignancies. Blood 125 (22), 3393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma P and Allison JP (2015) Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell 161 (2), 205–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolchok JD et al. (2013) Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 369 (2), 122–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin J et al. (2015) Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med 373 (1), 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postow MA et al. (2018) Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med 378 (2), 158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luksza M et al. (2017) A neoantigen fitness model predicts tumour response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nature 551 (7681), 517–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang P et al. (2018) Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med 24 (10), 1550–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma P and Allison JP (2015) The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 348 (6230), 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ott PA et al. (2017) An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature 547 (7662), 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilboa E (1999) The makings of a tumor rejection antigen. Immunity 11 (3), 263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher TN and Schreiber RD (2015) Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348 (6230), 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carreno BM et al. (2015) Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science 348 (6236), 803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahin U et al. (2017) Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 547 (7662), 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran E et al. (2015) Immunogenicity of somatic mutations in human gastrointestinal cancers. Science 350 (6266), 1387–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran E et al. (2016) T-Cell Transfer Therapy Targeting Mutant KRAS in Cancer. N Engl J Med 375 (23), 2255–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins PF et al. (2011) Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NYESO-1. J Clin Oncol 29 (7), 917–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins PF et al. (2015) A pilot trial using lymphocytes genetically engineered with an NY-ESO-1-reactive T-cell receptor: long-term follow-up and correlates with response. Clin Cancer Res 21 (5), 1019–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zacharakis N et al. (2018) Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Med 24 (6), 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strønen E et al. (2016) Targeting of cancer neoantigens with donor-derived T cell receptor repertoires. Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wendel BS et al. (2017) Accurate immune repertoire sequencing reveals malaria infection driven antibody lineage diversification in young children. Nat Commun 8 (1), 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma KY et al. (2018) Immune Repertoire Sequencing Using Molecular Identifiers Enables Accurate Clonality Discovery and Clone Size Quantification. Frontiers in Immunology 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollmers C et al. (2013) Genetic measurement of memory B-cell recall using antibody repertoire sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (33), 13463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstein JA et al. (2009) High-throughput sequencing of the zebrafish antibody repertoire. Science 324 (5928), 807–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd SD et al. (2009) Measurement and clinical monitoring of human lymphocyte clonality by massively parallel VDJ pyrosequencing. Sci Transl Med 1 (12), 12ra23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freeman JD et al. (2009) Profiling the T-cell receptor beta-chain repertoire by massively parallel sequencing. Genome Res 19 (10), 1817–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia Q et al. (2015) Diversity index of mucosal resident T lymphocyte repertoire predicts clinical prognosis in gastric cancer. OncoImmunology 4 (4), e1001230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuben A et al. (2017) TCR Repertoire Intratumor Heterogeneity in Localized Lung Adenocarcinomas: An Association with Predicted Neoantigen Heterogeneity and Postsurgical Recurrence. Cancer Discov 7 (10), 1088–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tumeh PC et al. (2014) PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515 (7528), 568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown SD et al. (2015) Profiling tissue-resident T cell repertoires by RNA sequencing. Genome Med 7, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munson DJ et al. (2016) Identification of shared TCR sequences from T cells in human breast cancer using emulsion RT-PCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (29), 8272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li B et al. (2016) Landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cell repertoire of human cancers. Nat Genet 48 (7), 725–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li B et al. (2017) Ultrasensitive detection of TCR hypervariable-region sequences in solid-tissue RNA-seq data. Nat Genet 49 (4), 482–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolotin DA et al. (2017) Antigen receptor repertoire profiling from RNA-seq data. Nat Biotechnol 35 (10), 908–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer M et al. (2016) A Distinct Gene Module for Dysfunction Uncoupled from Activation in Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells. Cell 166 (6), 1500–1511 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chihara N et al. (2018) Induction and transcriptional regulation of the co-inhibitory gene module in T cells. Nature 558 (7710), 454–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tirosh I et al. (2016) Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352 (6282), 189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung W et al. (2017) Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat Commun 8, 15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng C et al. (2017) Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 169 (7), 1342–1356 e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chevrier S et al. (2017) An Immune Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell 169 (4), 736–749 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei SC et al. (2017) Distinct Cellular Mechanisms Underlie Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 170 (6), 1120–1133 e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang AC et al. (2017) T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 545 (7652), 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krieg C et al. (2018) High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat Med 24 (2), 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo X et al. (2018) Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. Nat Med 24 (7), 978–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Savas P et al. (2018) Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat Med 24 (7), 986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gubin MM et al. (2014) Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature 515 (7528), 577–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snyder A et al. (2014) Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 371 (23), 2189–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Allen EM et al. (2015) Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 350 (6257), 207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizvi NA et al. (2015) Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348 (6230), 124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le DT et al. (2015) PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 372 (26), 2509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Le DT et al. (2017) Mismatch-repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Altman JD et al. (1996) Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274 (5284), 94–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang SQ et al. (2016) Direct measurement of T cell receptor affinity and sequence from naive antiviral T cells. Sci Transl Med 8 (341), 341ra77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davis MM et al. (1998) Ligand recognition by alpha beta T cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 16, 523–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang J et al. (2010) The kinetics of two-dimensional TCR and pMHC interactions determine T-cell responsiveness. Nature 464 (7290), 932–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams CM et al. (2017) Normalized Synergy Predicts That CD8 Co-Receptor Contribution to T Cell Receptor (TCR) and pMHC Binding Decreases As TCR Affinity Increases in Human Viral-Specific T Cells. Frontiers in Immunology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huppa JB et al. (2010) TCR-peptide-MHC interactions in situ show accelerated kinetics and increased affinity. Nature 463 (7283), 963–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang SQ et al. (2018) High-throughput determination of the antigen specificities of T cell receptors in single cells. Nat Biotechnol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bentzen AK et al. (2016) Large-scale detection of antigen-specific T cells using peptide-MHC-I multimers labeled with DNA barcodes. Nat Biotech 34 (10), 1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newell EW et al. (2009) Simultaneous detection of many T-cell specificities using combinatorial tetramer staining. Nat Methods 6 (7), 497–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Newell EW et al. (2013) Combinatorial tetramer staining and mass cytometry analysis facilitate T-cell epitope mapping and characterization. Nat Biotechnol 31 (7), 623–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simoni Y et al. (2018) Bystander CD8(+) T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature 557 (7706), 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tabula Muris C et al. (2018) Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature 562 (7727), 367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]