Abstract

An experiment was designed to determine the influence of fibre and betaine on the development of the intestine, liver and pancreas of broilers from hatch to 14 d of age. A total of 250-day-old Cobb 500 male broilers were allocated to 16 cages with 15 broilers each. Treatments were arranged in a 2 × 4 factorial design, consisting of 2 feed formulations (low and high fibre diets) and 4 levels of betaine (0, 1, 3 or 5 kg/t). At hatch, 10 birds in total were euthanised, and samples of the liver, pancreas, yolk sac and intestine were collected for reference of the analysed parameters before the start of the trial. On d 4, 9 and 14, 5 birds per cage (10 birds per treatment) were selected, euthanised and treated as the same as the birds at hatch. Villus height and width and crypt depth were determined on the duodenum samples, and absorptive area was calculated. The number of enterocytes in mitosis at the villus was determined by a positive reaction to antibody for Ki67 protein, and fused villus was evaluated visually. The relative weight of the yolk sac reduced (P < 0.05) as birds aged while the intestine and liver reached a maximum (P < 0.05) at around d 4 and the pancreas at d 9. Birds fed the high fibre diet had greater feed intake, lower relative weight of the pancreas and higher villus (P < 0.05) than birds fed the low fibre diet. Villus width increased (P < 0.05) at 4 d of age, and this was associated with fused villus. Betaine inclusion reduced (P < 0.05) villus width, increased (P < 0.05) villus size and absorptive area, and reduced (P < 0.05) the number of enterocytes with positive reaction for the antibody Ki-67. Betaine inclusion reduced the width and increased the absorptive area and the villus height of the duodenum of birds up to 14 d of age. The higher fibre diet increased feed intake and villus height, yet reduced pancreas relative weight, while not affecting body weight gain. This response was possibly due to a dilution effect of the fibre, reducing nutrient absorption and consequently stimulating villus growth to improve absorption rates.

Keywords: Broiler, Betaine, Fibre, Intestine maturation, Pancreas, Liver

1. Introduction

At hatch, the gastrointestinal tract of broilers is not completely developed (Uni et al., 1998a), affecting the ability of the animal to digest and absorb nutrients (Moran, 2007). There are dramatic changes in the first few days of age in physiological characteristics, such as expression of membrane transporters, endogenous enzyme activities and cell differentiation, and physical characteristics, including villus and crypt development and the size of the digestive tract (Geyra et al., 2001, Uni et al., 2001). Changes in these parameters reaches a plateau between d 7 and 10, depending on the parameter observed, when the bird is classified as having a mature digestive tract (Geyra et al., 2001, Matthews and Southern, 2000).

During the first days after hatch, broilers need to adapt the digestive tract from a diet based on fat and easily digestible protein from the yolk to a more complex diet based on carbohydrates, less digestible and available protein, mineral sources and non-digestible components such as fibre (Moran, 2007). This change in substrate as a result of diet introduction, coupled with the insufficient ability to digest and absorb nutrients as the digestive tract is not yet mature, means that nutrient digestibility is lower in young animals (Leite et al., 2011). This results in an increased concentration of indigestible nutrients in the lumen of the digestive tract and elevates osmotic pressure which may lead to flow of water from the digestive tract epithelium to the lumen (Kettunen et al., 2001a). High osmotic pressure can lead to inflammatory responses (Hubert et al., 2004, Schwartz et al., 2009) and apoptosis of enterocytes (Alfieri et al., 2002), affecting nutrient digestibility and animal performance.

Development of the gastrointestinal tract is presented by an increase in size and weight compared to other tissues (Obst and Diamond, 1992), and through an increase in villus number and absorptive area, maturation of enterocytes, and an increase in endogenous enzyme production and transporter expression (Uni et al., 1998a). This development of the intestinal mass is important as it correlates with the growth rate of the chicken (Obst and Diamond, 1992). Early development and maturation of the digestive tract is also important for the subsequent development of other tissues and organs (Moran, 2007) such as the immune system (Dibner et al., 1998) and muscle (Halevy et al., 2000). Several strategies to improve gut development have been employed, such as the use of highly digestible or fibrous ingredients (Jimenez-Moreno et al., 2009), changes in feed particle size and whole ingredients (Svihus et al., 2004), and substances that stimulate the development and maturation of the gut such as glutamine (Nascimento et al., 2014) and betaine (Kettunen et al., 2001b).

Studies of fibrous ingredients and their impact on gut development and bird performance have shown inconsistent results. Inclusion of fibrous ingredients stimulates gut development and villus growth (Adibmoradi et al., 2016) and consequently increases the absorptive area of the gastrointestinal tract, but also reduces energy and nutrient digestibility of broilers by dilution (Annison and Choct, 1991). Fibre inclusion modulates lower gut fermentation and affects the microbiota profile (Rezaei et al., 2011), while soluble fibre can also increase gut viscosity and passage rate of digesta in the small intestine (Adeola et al., 2016). Fibre fermentation in the lower gut produces volatile fatty acids such as acetic, propionic and butyric acids. Presence of these volatile fatty acids reduces the pH in the ceaca, inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria, increase mineral absorption and enterocyte proliferation (Kumar et al., 2012).

Part of this inconsistency may be related to variability of the structures which are classified as fibre. The most common systems for classifying fibre are crude fibre, neutral and acid detergent fibre but these assays fail to account for the solubility of the fibre and variation in its structure from different ingredients, each of which have different effects in vivo. Fibre evaluation based on its nutritional properties, solubility and type of sugar would be more relevant (Choct, 2015). The most common non-starch polissaccharide in cereals is arabinoxylans (Knudsen, 2014). The composition of this can be calculated by the sum of arabinose and xylose component in the cereal ingredients used in formulation (Rakha et al., 2012). In leguminous ingredients such as soybean meal the most prominent non-starch polysaccharide is xyloglucan (Knudsen, 2014).

Natural betaine is a feed additive derived from sugar beet. Betaine is used in poultry nutrition both to reduce methionine and choline requirement as a methyl donor and as an osmoprotectant to reduce performance losses in stressful situations, such as heat and hyperosmotic stress (Eklund et al., 2005, Ratriyanto et al., 2009). Betaine accumulates in the intestines, liver and kidney of broilers, serving as a methyl donor for adenosyl cysteine directly or by further demethylation in the mitochondria where it also forms glycine (Craig, 2004). Betaine accumulation is stimulated in cells suffering hyperosmotic stress independent of the presence of the betaine in the feed, suggesting that its accumulation is a natural defense of the organism (Kettunen et al., 2001b). Betaine is also known as a chemical chaperone (Schwahn et al., 2003), reducing protein denaturation and maintaining protein and endogenous enzyme activity during heat and hyperosmotic situations (Gonnelli and Strambini, 2001).

Betaine has been shown to improve water transit through the enterocyte, stimulate villus growth of broilers and reduce the effect of a coccidial challenge (Kettunen et al., 2001b). It also reduces enterocyte apoptosis (Alfieri et al., 2002) and improves inflammatory responses such as the phagocytosis activity of macrophages and nitrogen oxide release (Klasing et al., 2002). The data are equivocal however, as no effect was observed when betaine was fed in conjunction with a coccidial challenge (Matthews and Southern, 2000) and performance results have also been inconsistent results (Rostagno and Pack, 1996). Betaine has been shown to improve performance of young chicks passing through the transition period after hatching, administration via in ovo nutrition has been shown to regulate hepatic cholesterol metabolism (Hu et al., 2015) and improve hatching weight, final weight and feed conversion of chickens at 42 d of age (Gholami et al., 2015).

The objective of this trial was to evaluate the effect of increasing the concentration of insoluble non-starch polysaccharides levels, using rice bran as source of arabinoxylans, and betaine inclusion in the development and maturation of the intestine, liver and pancreas of broilers between hatch and 14 d of age.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and experimental design

The trial design was evaluated and approved by the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Agricultural Science Campus of the Universidade Federal do Paraná (Protocol number 002/2015). A total of 250 day-old male Cobb 500 broilers were sourced specifically for the experiment and housed in 16 stainless steel cages with 15 birds/cage. A further 10 birds were included for sampling at housing (hatch) for determination of starting parameters. Room temperature was controlled with electric heaters to meet recommendations for different ages (Cobb-Vantress Inc., 2015). Cage dimensions were 0.90 m × 0.40 m, with 0.30 m height. Birds had access to water and feed ad libitum. Treatments consisted of a 2 × 4 factorial arrangement with 2 feed formulations with different levels of insoluble arabinoxylans concentration (low and high based in the inclusion rate of rice bran) and 4 inclusion rates of betaine (0, 1, 3 and 5 kg betaine/t of feed).

2.2. Diets and experimental products

Corn, soybean meal and rice bran were analysed for moisture, protein, fibre, non-starch polysaccharides composition, minerals, fat and betaine contents prior to formulation (Table 1). Non starch polysaccharides were determined in vegetable ingredients by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) after acid hydrolysis (Englyst et al., 1994) and betaine analysed in feeds and ingredients by HPLC (Eurofins Scientific Inc. Des Moines, United States). Arabinoxylans were calculated based on the concentration of arabinose and xylose levels in corn and rice bran (Rakha et al., 2012) and non-starch polysaccharides concentration was calculated based on the constituent sugars determined in corn, soybean meal and rice bran after acid hydrolysis. Diets (Table 2) were formulated according to requirements for broilers (Rostagno, 2011). Betaine (Vistabet 96, AB Vista – Marlborough, United Kingdom) was included to each treatment by replacing similar weight of washed sand. Feed samples were collected prior to the beginning of the trial for moisture, protein, fibre, minerals, fat and betaine contents to confirm the feed formulation (Table 3).

Table 1.

Nutrient, betaine and non starch polysaccharides composition of corn, soybean meal and rice bran ingredients used in feed formulation.

| Item | Corn | Soybean meal | Rice bran | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | ||||

| Moisture | 12.68 | 11.29 | 8.70 | |

| Crude protein | 8.20 | 46.01 | 12.77 | |

| Ether extract | 3.29 | 1.91 | 22.53 | |

| Ash | 0.87 | 5.51 | 9.56 | |

| Crude fibre | 1.57 | 5.64 | 18.36 | |

| Calcium | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.15 | |

| Phosphorus | 0.25 | 0.64 | 1.81 | |

| Betaine | LD1 | LD1 | LD1 | |

| Non starch polysaccharides composition, g/kg | ||||

| Rhamnose | Soluble | LD2 | 1.0 | LD2 |

| Insoluble | LD2 | 1.0 | LD2 | |

| Fucose | Soluble | LD2 | LD2 | LD2 |

| Insoluble | LD2 | 2.0 | LD2 | |

| Arabinose | Soluble | 1.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| Insoluble | 14.0 | 19.0 | 33.0 | |

| Xylose | Soluble | LD2 | 1.0 | LD2 |

| Insoluble | 22.0 | 13.0 | 40.0 | |

| Mannose | Soluble | 2.0 | 5.0 | LD2 |

| Insoluble | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | |

| Galactose | Soluble | 1.0 | 11.0 | 2.0 |

| Insoluble | 5.0 | 32.0 | 9.0 | |

| Glucose | Soluble | 6.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Insoluble | 25.0 | 46.0 | 61.0 | |

| Glucuronic acid | Soluble | LD2 | LD2 | LD2 |

| Insoluble | LD2 | LD2 | LD2 | |

| Galacturonic acid | Soluble | 2.0 | 10.0 | 2.0 |

| Insoluble | 2.0 | 16.0 | 2.0 | |

| Arabinoxylans3 | Soluble | 1.0 | ND4 | 2.0 |

| Insoluble | 36.0 | ND4 | 73.0 | |

| Total non starch polysaccharides | Soluble | 12.0 | 35.0 | 8.0 |

| Insoluble | 71.0 | 134.0 | 148.0 | |

Below limit of detection (0.07 g/kg).

Below limit of detection (1 g/kg).

Calculated as reported by Rakha et al. (2012).

Not determined as arabinoxylanses are not present in soybean meal.

Table 2.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of experimental diets (as-fed basis)1.

| Item | Low fibre diet | High fibre diet |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | ||

| Corn (8% CP) | 53.36 | 46.38 |

| Rice bran (12.5% CP) | – | 7.00 |

| Soybean oil | 3.50 | 4.35 |

| Soybean meal (46% CP) | 38.50 | 37.65 |

| Limestone | 1.06 | 1.09 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.80 | 1.75 |

| Salt | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Vitamin-mineral premix2 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Lysine HCl | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| DL-methionine | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| L-threonine | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Washed sand1 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Choline chloride | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Calculated nutritional value, g/kg | ||

| Crude protein | 220.0 | 220.0 |

| Metabolizable energy, kcal/kg | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| Crude fibre | 29.5 | 43.5 |

| Soluble arabinoxylan | 0.50 | 0.60 |

| Insoluble arabinoxylan | 19.2 | 21.8 |

| Soluble NSP | 19.9 | 19.3 |

| Insoluble NSP | 89.5 | 93.7 |

| Ether extract | 60.0 | 77.0 |

| Ash | 34.0 | 39.0 |

| Calcium | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Phosphorous | 6.8 | 7.6 |

| Available phosphorous | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Sodium | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Digestible lysine | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Digestible methionine + cysteine | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Digestible threonine | 8.1 | 8.1 |

CP = crude protein; NSP = non starch polysaccharides.

Betaine included between 0 and 5 kg/t at the expense of the washed sand.

Supplied per kilogram diet: iron (ferrous sulphate), 60 mg; manganese (manganese sulphate and manganese oxide), 120 mg; zinc (zinc oxide), 100 mg; iodine (calcium iodate), 1 mg; copper (copper sulphate), 8 mg; selenium (sodium selenite), 0.3 mg, vitamin A, 9,600 IU; vitamin D3 3,600 IU; vitamin E, 18 mg; vitamin B12, 15 μg; riboflavin, 10 mg; niacin, 48 mg; D-pantothenic acid, 18 mg; vitamin K, 2 mg; folic acid, 1.2 mg; vitamin B6, 4 mg; thiamine, 3 mg; D-biotin, 72 μg.

Table 3.

Proximate analysis and betaine content in feed samples (as-fed basis).

| Item | Moisture, % |

Crude protein, % |

Ether extract, % |

Crude fibre, % |

Calcium, % |

Phosphorus, % |

Betaine, g/kg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | Exp | Anal | |

| Low fibre treatment | ||||||||||||||

| Betaine inclusion, kg/t | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 11.50 | 11.29 | 22.00 | 22.21 | 6.00 | 5.91 | 2.95 | 4.79 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.0 | LD1 |

| 1 | 11.50 | 11.21 | 22.00 | 22.22 | 6.00 | 5.80 | 2.95 | 5.03 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 11.50 | 11.71 | 22.00 | 21.97 | 6.00 | 6.03 | 2.95 | 4.44 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 11.50 | 11.49 | 22.00 | 22.08 | 6.00 | 6.05 | 2.95 | 4.52 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 5.0 | 5.1 |

| High fibre treatment | ||||||||||||||

| Betaine inclusion, kg/t | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 10.50 | 10.51 | 22.00 | 21.82 | 7.70 | 8.08 | 4.35 | 6.15 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.0 | LD1 |

| 1 | 10.50 | 10.46 | 22.00 | 22.00 | 7.70 | 7.73 | 4.35 | 5.19 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| 3 | 10.50 | 10.75 | 22.00 | 21.82 | 7.70 | 8.23 | 4.35 | 5.46 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| 5 | 10.50 | 11.08 | 22.00 | 22.49 | 7.70 | 7.82 | 4.35 | 5.97 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 5.0 | 5.2 |

Exp = expected; Anal = analysed.

Below limit of detection (0.07 g/kg).

2.3. Performance parameters

Body weight gain was determined at d 4, 9 and 14, and feed intake determined at d 14 when feed conversion was calculated. Mortality was monitored daily and any dead or culled birds weighed the same day, with this weight included for the calculation of feed conversion.

2.4. Sample collection and morphometry

At hatch, 10 birds that were not assigned to a treatment were separated for initial sampling for reference of the analysed parameters before the start of the trial. Birds were weighted and then euthanised by cervical dislocation. The intestine was collected from the cardiac junction to the cloaca. Intestine, liver and pancreas were weighted and the proportion of weight calculated against live weight of the bird. Intestine length was also measured. After weighing and measuring the intestine, two duodenum samples from each bird were taken from within 2 cm immediately anterior of the pancreatic duct for microscopy analysis. At d 4, 9 and 14, 10 birds per treatment were separated and the same collection process was followed for the determination of organ morphometry and 5 intestine samples in each treatment selected for duodenum collection.

2.5. Morphology of duodenal mucosa

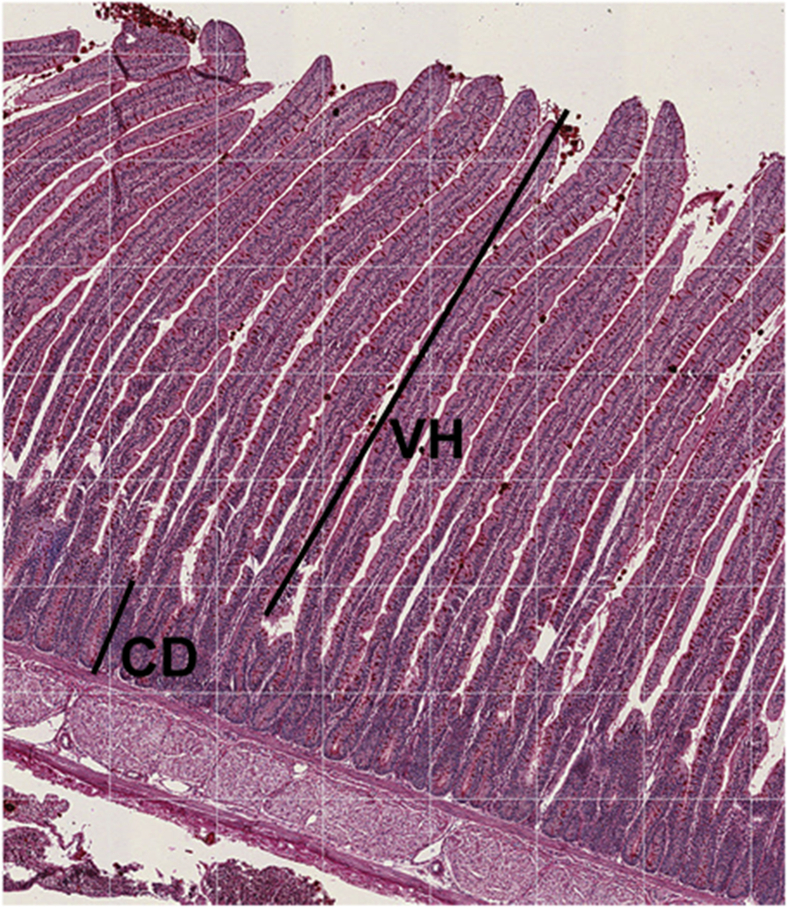

Villus height and crypt depth were determined using 10 birds at hatch, and 5 birds per treatment at d 4, 9 and 14 (Iji et al., 2001). Duodenum samples were washed with saline solution to remove any debris from the intestinal lumen sample and fixed with Bouin's solution. After 24 h samples were washed and dehydrated with etilic alcohol. The samples were set into paraffin blocks and 5 μm sections were cut. Samples were coloured with hematoxiline and eosine solution. Images were captured at 40× magnification and analysed using an image analysis system (Image J). An average of 40 villi/sample was analysed, villus height was determined from the base to the top of the villi, villi weight was determined as the distance between both sides of the villi at the intermediate part of the villi and crypt depth determined from the base of the villi until the base of the crypt (Fig. 1). Proportion of villus height and crypt depth was calculated based on the average of each sample. Absorption surface area was calculated as reported by Kisielinski et al. (2002): Absorption area = [(WV × HV) + (WV/2 + WC/2)2 – (WV/2)2]/(WV/2 + WC/2)2, where WV is the width of the villus, HV is the height of the villus and WC is the width of the crypt.

Fig. 1.

Villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD) of broilers at 14 d of age.

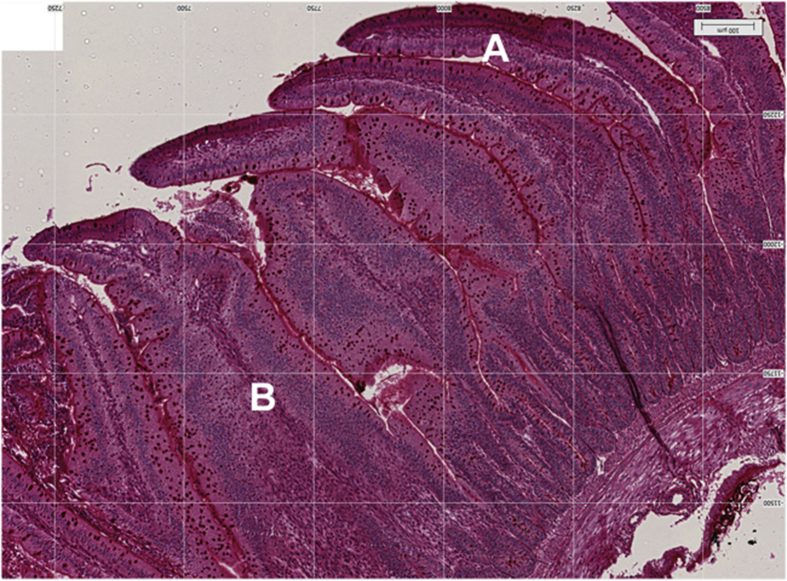

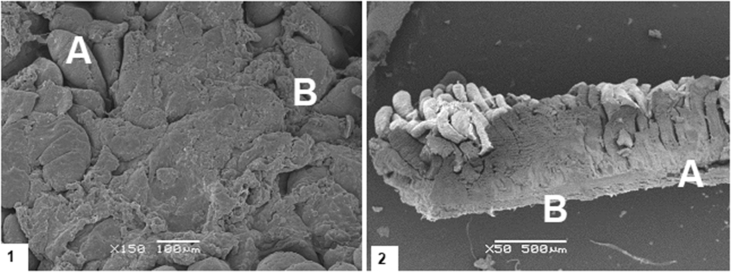

2.6. Proportion of fused villus

Classification of fused villus, as with characteristics of an inflammatory response (Gholamiandehkordi et al., 2007, Teirlynck et al., 2009), was made on the same 40 villus/sample used for the determination of villus height, weight and crypt depth. Determination of fused villus was done visually and reported as a proportion of all villus evaluated for each sample as described by Gholamiandehkordi et al. (2007). A villus was considered fused when it shows a wider structure than it would be expected and characteristics of replication of enterocytes forming a multiple layer as shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Villus of broilers at 4 d of age. (A) represents a regular villus, (B) represents a villus classified as fused.

Fig. 3.

Villus of broilers at (1) 4 d and (2) 9 d of age. (A) represents a regular villus, (B) represents a villus classified as fused.

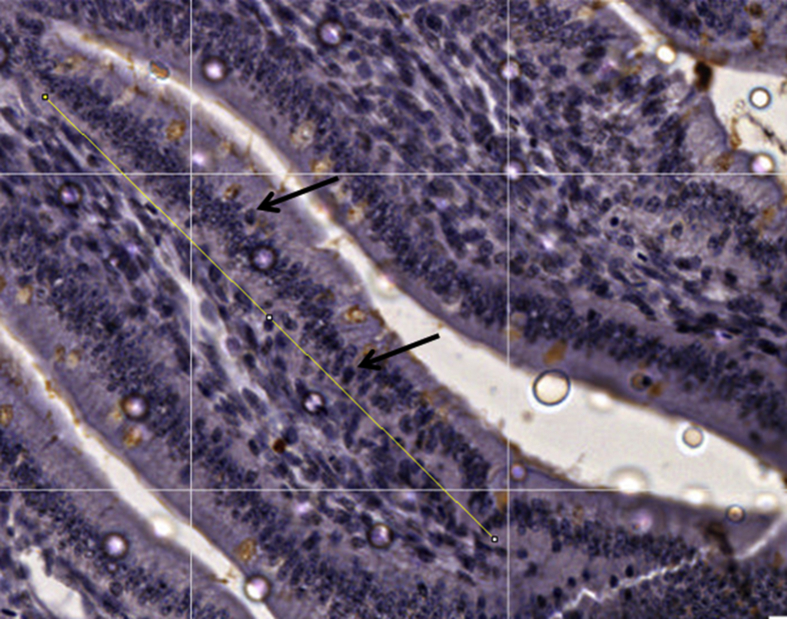

2.7. Number of cells in mitosis

The number of cells was determined using 10 birds at hatch and 5 birds per treatment at d 4, 9 and 14. Antibody Ki-67 was used as a reference of cells under replication (Bologna-Molina et al., 2013). After deparaffinization and rehydration, the tissue section was treated with 0.1 mol/L sodium citrate and Tween 20 to unravel the epitopes. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with 0.9% hydrogen peroxide followed by incubation with 1% BSA to eliminate non-specific bindings. Monoclonal antibodies against Ki-67 (clone MIB-1:100 dilution, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) were incubated with the tissue sections for 45 min. After that period sections were incubated with a biotinylated antibody and peroxidase complex for 30 min each. Images were captured at 40× magnification and analysed using an image analysis system (Image J). Average 30 villi/sample was analysed by the determination of a 200 μm area in the central part of the villi. Positive reaction was determined by colour of the cell nucleus (Fig. 4). All analyses were performed as blind samples by the same trained operator to avoid personal bias.

Fig. 4.

Villus of broilers at 4 d of age. The yellow line represents a 200-μm distance. Cell with positive reaction for Ki-67 antibody are represented by dark nucleolus as indicated by black arrows.

2.8. Scanning electron microscopy

Duodenum samples were taken from 3 birds at hatch and three birds per treatment at d 4 and 9, as described by Maiorka et al. (2003). Samples were collected, intestinal content gently removed with a saline solution and immediately fixed in modified Karnovsky's fixative for 2 h, washed with 0.1 mol/L cacodylic acid buffer (pH 7.3), post-fixed in 1% SO4 in 0.1 mol/L cacodylic acid buffer (pH 7.3) for 1 h, dehydrated in increasing ethanol series, and dried with liquid carbon dioxide. Each duodenum sample was fractionated into 4 different sub-samples that were analysed individually in at least 6 different points in a total of 24 evaluations per sample. Scanning electron microscopy was performed using VEGA3 LMU (Tescan, Kohoutovice, Czech Republic) at 15 kV. Samples were mounted on aluminium stubs with double face tape and coated with layer of gold (SCD 030; Pfeiffer, Balzers, Liechtenstein). Large volumes of samples were evaluated so that the structures reported were consistent on different areas of different animals and correlated with findings from staining microscopy.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality by Shapiro-Wilk and subjected to least squares ANOVA for a completely randomized design procedure of JMP Pro v.13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data wereanalysed in a three-way interaction considering age, non-starch polysaccharide content of the diet and betaine inclusion. Each animal served as the experimental unit. When the effects were found to be significant, treatment means were separated using Tukey's Significant Difference test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. When the main effect of betaine was significant, means were separated using linear and quadratic orthogonal contrasts.

3. Results

Moisture, crude protein, ether extract, calcium, phosphorus and betaine concentration in the feed samples were close to expected levels (Table 3). Fibre concentration was higher than expected in both diets. However, the difference in crude fibre content between the low and high fibre diets was kept constant between treatments, which maintained the expected difference in fibre concentration between low and high fibre diets. Differences observed may be partially explained by the presence of washed sand in the formulation as this will not solubilize during the fibre analysis assay and thus would also be accounted for in the fibre fraction. Moreover, regarding the expected fibre concentration, a 10% to 15% variation in analysis is considered acceptable (FAO, 2011).

Performance response to dietary treatments is shown in Table 4. Mean broiler weights were 47, 121, 260 and 456 g at hatch, d 4, 9 and 14, respectively, close to the expected weight of the genetic line (Cobb, 2015). Betaine inclusion and fibre concentration did not affect body weight gain or feed conversion at d 14 (P > 0.05). Animals fed diets with high fibre concentration had higher (P = 0.028) feed intake (564 ± 19 g) than those fed diets with low fibre concentration (491 ± 19 g).

Table 4.

Performance of broilers fed low and high fibre diets included with betaine1.

| Fibre | Betaine inclusion, kg/t | Initial body weight, g | Day 4 |

Day 9 |

Day 14 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | Feed intake, g | FCR | Body weight, g | Feed intake, g | FCR | Body weight, g | Feed intake, g | FCR | |||

| Low | 0 | 46.7 | 72.7 | 64.3 | 0.89 | 221.8 | 276.1abc | 1.20 | 402.3 | 534.1 | 1.24 |

| 1 | 46.7 | 73.2 | 67.7 | 0.93 | 215.9 | 272.2abc | 1.21 | 403.3 | 543.7 | 1.28 | |

| 3 | 46.3 | 69.7 | 77.7 | 1.13 | 213.1 | 305.4a | 1.40 | 406.2 | 436.9 | 1.21 | |

| 5 | 45.2 | 76.2 | 89.0 | 1.16 | 217.0 | 293.3ab | 1.33 | 415.3 | 448.3 | 1.18 | |

| High | 0 | 48.3 | 79.8 | 66.3 | 0.84 | 197.8 | 280.6abc | 1.36 | 404.2 | 530.1 | 1.30 |

| 1 | 47.0 | 68.0 | 42.8 | 0.62 | 203.2 | 244.3bc | 1.13 | 407.5 | 569.8 | 1.28 | |

| 3 | 46.7 | 76.7 | 59.8 | 0.78 | 212.8 | 242.8c | 1.08 | 406.8 | 612.8 | 1.30 | |

| 5 | 48.0 | 77.0 | 73.3 | 0.96 | 225.9 | 289.1abc | 1.24 | 430.0 | 544.1 | 1.25 | |

| SEM | 0.36 | 1.90 | 3.95 | 0.050 | 4.57 | 5.85 | 0.038 | 6.67 | 17.37 | 0.014 | |

| Low | 46.2 | 73.0 | 74.7 | 1.02 | 217.0 | 286.7 | 1.29 | 406.8 | 490.7 | 1.23 | |

| High | 47.5 | 75.4 | 60.6 | 0.80 | 209.9 | 264.2 | 1.20 | 412.1 | 564.2 | 1.28 | |

| SEM | 0.52 | 3.16 | 4.29 | 0.051 | 7.72 | 4.47 | 0.051 | 12.18 | 19.39 | 0.019 | |

| 0 | 47.5 | 76.2 | 65.3 | 0.86 | 209.8 | 278.3 | 1.28 | 403.3 | 532.1 | 1.27 | |

| 1 | 46.8 | 70.6 | 55.3 | 0.77 | 209.6 | 258.3 | 1.17 | 405.4 | 556.8 | 1.28 | |

| 3 | 46.5 | 73.2 | 68.8 | 0.95 | 212.9 | 274.1 | 1.24 | 406.5 | 524.8 | 1.26 | |

| 5 | 46.6 | 76.6 | 81.2 | 1.06 | 221.4 | 291.2 | 1.29 | 422.7 | 496.2 | 1.22 | |

| SEM | 0.74 | 4.47 | 6.07 | 0.073 | 10.92 | 6.32 | 0.072 | 17.23 | 27.43 | 0.027 | |

| P-value | |||||||||||

| Fibre | 0.120 | 0.605 | 0.049 | 0.015 | 0.537 | 0.007 | 0.269 | 0.765 | 0.028 | 0.073 | |

| Betaine | 0.775 | 0.759 | 0.089 | 0.106 | 0.853 | 0.037 | 0.661 | 0.847 | 0.515 | 0.445 | |

| Fibre × Betaine | 0.600 | 0.738 | 0.490 | 0.511 | 0.735 | 0.023 | 0.211 | 0.991 | 0.174 | 0.666 | |

| Linear (betaine) | 0.091 | ||||||||||

| Quadratic (betaine) | 0.019 | ||||||||||

FCR = feed conversion ratio corrected for mortality.

a, b, c Within a column, means with different superscripts are different at P < 0.05.

Means and standard error of the mean represent 2 replicates per treatment.

The proportion of the yolk sac, intestine, liver and pancreas as a function of the live body weight of broilers between hatch and d 14 are reported in Table 5. At hatch, yolk sac represented more than 14% of the weight of the broiler but this value reduced (P < 0.05) dramatically at d 4 and reduced further (P < 0.05) at d 14. Intestinal weight as a proportion of body weight was greatest (P < 0.001) at d 4 and reduced thereafter. The weight of the pancreas was below the limit of detection at hatch, indicating that its relative weight was less than 0.1% (0.05 g) of the bird's weight at that age. Pancreas relative weight increased (P < 0.05) at d 4 and 9. Birds fed the high fibre diet had a lighter (P < 0.05) pancreas, as a proportion of body weight, compared with animals fed low fibre diet. Liver weight reduced (P < 0.05) proportionally to the body weight of the bird after d 4. Fibre concentration in the feed and betaine inclusion did not affect yolk sac and liver proportions, nor the length or relative weight of the intestine (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Intestinal length and relative weight of intestine, yolk sac, liver and pancreas of broilers fed low and high fibre diets included with betaine1.

| Item | Intestine |

Yolk sac, %BW | Liver, %BW | Pancreas, %BW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length, cm | Weight, %BW | ||||

| Age, d | |||||

| 0 (Hatch) | 44.4d | 5.95d | 14.40a | 4.62a | ND4 |

| 4 | 93.1c | 14.27a | 0.31b | 4.65a | 0.46b |

| 9 | 112.4b | 11.90b | 0.08bc | 3.88b | 0.51a |

| 14 | 132.9a | 10.77c | 0.06c | 3.32c | 0.49ab |

| SEM1 | 1.01 | 0.147 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 0.013 |

| Fibre | |||||

| Low2 | 112.0 | 12.19 | 0.10 | 3.99 | 0.51a |

| High3 | 113.0 | 12.44 | 0.20 | 3.91 | 0.47b |

| SEM | 0.82 | 0.120 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.010 |

| Betaine, kg/t | |||||

| 0 | 113.5 | 12.40 | 0.24 | 3.92 | 0.49 |

| 1 | 111.0 | 12.46 | 0.12 | 3.85 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 112.6 | 12.27 | 0.15 | 4.01 | 0.48 |

| 5 | 112.5 | 12.16 | 0.09 | 4.03 | 0.47 |

| SEM | 1.16 | 0.169 | 0.067 | 0.074 | 0.015 |

| P-value | |||||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Fibre | 0.590 | 0.143 | 0.128 | 0.356 | 0.017 |

| Betaine | 0.465 | 0.595 | 0.450 | 0.304 | 0.414 |

| Fibre × Betaine | 0.349 | 0.495 | 0.734 | 0.254 | 0.317 |

| Fibre × Age | 0.352 | 0.123 | 0.785 | 0.914 | 0.924 |

| Betaine × Age | 0.649 | 0.167 | 0.911 | 0.320 | 0.053 |

| Fibre × Betaine × Age | 0.551 | 0.148 | 0.599 | 0.705 | 0.683 |

a, b, c Mean within columns with different superscripts are different (P < 0.05).

Standard error of the mean of 10 birds.

Corn-soybean meal diet.

Corn-rice bran-soybean meal diet.

Below limit of detection.

Aspects of villus morphometry was affected by the age of the bird, content of fibre in the diet and betaine inclusion in the diet (Table 6). Both higher fibre concentration (P < 0.05) and betaine (linear, P < 0.01) increased villus height (P < 0.05), while no effect was observed of both on crypt depth or villus:crypt ratio. Villus width was greater (P < 0.05) in animals at d 4 and 9 compared with birds at hatch and d 14, while villus width was reduced (linear, P < 0.01) by the inclusion of betaine in the diet. No difference in the absorptive area of the intestine was observed between animals of d 0 and 4, although area increased in animals at d 9 and 14 (P < 0.05). Inclusion of betaine increased (linear, P < 0.01) the absorptive area of the duodenum of broilers, compared to the non-supplemented control.

Table 6.

Villus morphology and absorptive area of the duodenum of broilers fed low and high fibre diets included with betaine1.

| Item | Villus |

Crypt depth, μm | Villus:crypt ratio | Absorptive area, μm2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height, μm | Width, μm | ||||

| Age, d | |||||

| Hatch | 421d | 84b | 74c | 5.75bc | 17.0c |

| 4 | 857c | 170a | 165b | 5.27c | 15.6c |

| 9 | 1,159b | 129a | 172ab | 6.81b | 26.67b |

| 14 | 1,365a | 110b | 180a | 7.81a | 36.9a |

| SEM1 | 19.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 0.186 | 1.17 |

| Fibre | |||||

| Low2 | 1,096b | 128 | 173 | 6.44 | 25.5 |

| High3 | 1,153a | 124 | 172 | 6.79 | 27.3 |

| SEM | 15.7 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 0.155 | 1.12 |

| Betaine, kg/t | |||||

| 0 | 1,080b | 136a | 166 | 6.59 | 24.8b |

| 1 | 1,131ab | 130ab | 179 | 6.42 | 25.0ab |

| 3 | 1,121ab | 120b | 177 | 6.39 | 25.7ab |

| 5 | 1,174a | 120b | 167 | 7.12 | 30.0a |

| SEM | 22.2 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 0.218 | 1.37 |

| P-value | |||||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fibre | 0.022 | 0.359 | 0.799 | 0.149 | 0.205 |

| Betaine | 0.037 | 0.019 | 0.133 | 0.081 | 0.027 |

| Fibre × Betaine | 0.854 | 0.551 | 0.737 | 0.696 | 0.764 |

| Fibre × Age | 0.736 | 0.997 | 0.776 | 0.816 | 0.802 |

| Betaine × Age | 0.866 | 0.697 | 0.278 | 0.567 | 0.568 |

| Fibre × Betaine × Age | 0.729 | 0.215 | 0.988 | 0.782 | 0.951 |

| Linear (betaine) | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.009 | ||

| Quadratic (betaine) | 0.958 | 0.456 | 0.129 | ||

a, b Mean within columns with different superscripts are different (P < 0.05).

Standard error of the mean of 10 birds at hatch and 5 birds at 4, 9 and 14 d of age.

Corn-soybean meal diet.

Corn-rice bran-soybean meal diet.

Fused villus and the presence of enterocytes in the villus with positive reaction to antibody Ki-67 are reported in Table 7. The proportion of fused villus in the duodenum increased (P < 0.05) from hatch to d 4, reducing afterwards, with no effect of betaine or fibre concentration. Inclusion of betaine reduced (linear, P < 0.001) the number of enterocytes with positive reaction for the antibody Ki-67 at the centre portion of the villus, compared to the non-supplemented control. Birds at d 14 had lower (P < 0.05) number of enterocytes with positive reaction to the antibody Ki-67 on the villus compared with birds of younger age and fewer (P < 0.05) were noted at d 9 compared with birds at d 4. Fibre concentration had no influence on the number of enterocytes with positive reaction to the antibody Ki-67.

Table 7.

Proportion of fused villus and number of enterocytes cells with positive reaction for Ki-67 antibody in the centre of the villus in the duodenum of broilers1.

| Treatments | Proportion of fused villus, % | Positive Ki-67 reaction, cells/200 μm3 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, d | ||

| Hatch | 0.0c | 4.79ab |

| 4 | 19.1a | 5.91a |

| 9 | 10.3b | 3.98b |

| 14 | 1.7c | 2.78c |

| SEM1 | 1.30 | 0.188 |

| Fibre | ||

| Low2 | 10.5 | 4.21 |

| High3 | 10.5 | 4.11 |

| SEM | 0.105 | 0.105 |

| Betaine, kg/t | ||

| 0 | 12.6 | 5.32a |

| 1 | 10.6 | 4.22b |

| 3 | 9.0 | 3.86b |

| 5 | 9.7 | 3.16c |

| SEM | 1.57 | 0.150 |

| P-value | ||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fibre | 0.917 | 0.353 |

| Betaine | 0.352 | <0.001 |

| Fibre × Betaine | 0.287 | 0.564 |

| Fibre × Age | 0.619 | 0.487 |

| Betaine × Age | 0.856 | 0.180 |

| Fibre × Betaine × Age | 0.579 | 0.266 |

| Linear (betaine) | <0.001 | |

| Quadratic (betaine) | 0.631 | |

a, b, c Mean within columns with different superscripts are different (P < 0.05).

Standard error of the mean of 10 birds at hatch and 5 birds at 4, 9 and 14 d of age.

Corn-soybean meal diet.

Corn-rice bran-soybean meal diet.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of the present trial was to evaluate the development of the gastrointestinal tract of broilers in the initial days after hatch. Performance effects were not the main scope of the trial as birds were only raised until d 14. Although the small number of replicates per treatment when considering performance results should be considered, the results suggest no adverse performance responses to dietary treatment.

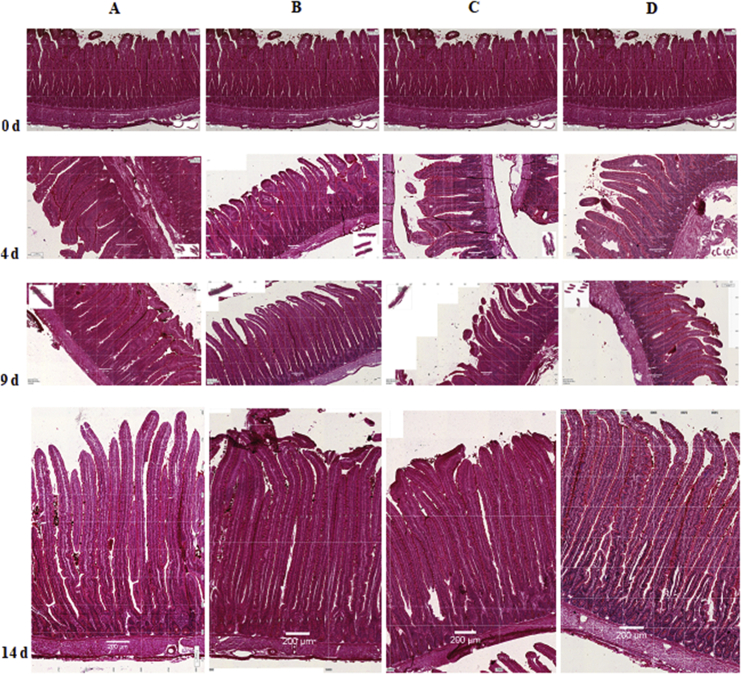

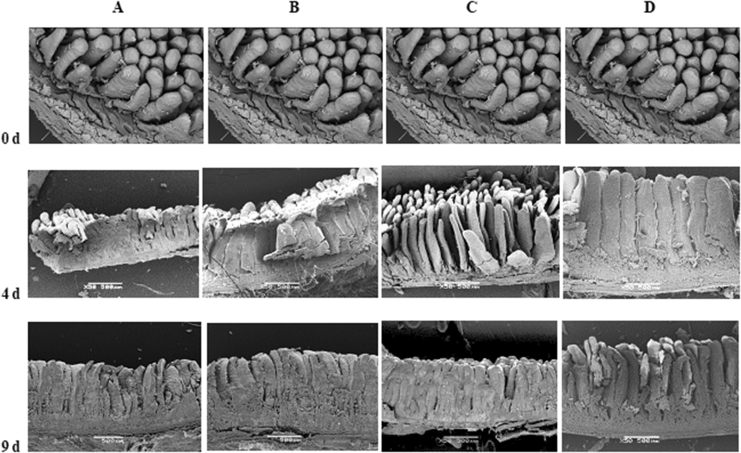

At hatch, the gastrointestinal tract is not totally developed and several transformations take place once the bird starts to eat a complex diet based on carbohydrates and proteins (Geyra et al., 2001). In the present trial, both stained and electron microscopy were used to evaluate the development and maturation of broiler chicken duodenum enterocytes between hatch and d 14 (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, respectively). At hatch, enterocytes present a small structure with small villus; however dramatic morphological changes occur up to d 14 when the structure looks similar to a duodenum villus of older birds (Iji et al., 2001).

Fig. 5.

Duodenum samples, evaluated by staining microscopy, of broilers fed a low fibre diet with (A) 0 or (B) 5 kg of betaine/t or a high fibre diet with (C) 0 or (D) 5 kg of betine/t at 0 (hatch), 4, 9 and 14 d of age. Figures for 0 d of age (at hatch) are the same for all treatments. White bars in the centre bottom of each figure represents 200 μm.

Fig. 6.

Duodenum samples, evaluated by scanning electron microscopy, of broilers fed a low fibre diet with (A) 0 or (B) 5 kg of betaine/t or a high fibre diet with (C) 0 or (D) 5 kg of betine/t at 0 (hatch), 4 and 9 d of age. Figures at hatch are the same for all treatments. White bars in the centre bottom of figures represents 500 µm.

As early as d 4, the contents of the yolk sac had almost completely disappeared, at the same time as the size and weight of the intestine increased. The length of the intestine more than doubled between hatch and d 4, while its relative weight increased almost 3 times during these initial 4 d. Increased pancreas and maintained liver size, as a proportion of live body weight, confirms the degree and rate of specialization of the gastrointestinal tract taking place in order to improve nutrient digestibility and absorption. At d 9 post-hatch, the relative size of the pancreas continues to grow while the proportionate size of the liver and intestine reduces. Lilburn and Loeffler (2015) reported that the relative growth of the intestine and pancreas plateau at approximately d 8, supporting the findings of the present trial.

Birds fed diets with high fibre diets had lower relative pancreatic weights. Previous trials have shown that a larger particle size may stimulate gizzard development and pancreas size possibly related to a stimulus to pancreatic secretion (Svihus et al., 2004), so it is possible that the small particle size of rice bran in the present trial, as a substitute for ground corn, played a role reducing the relative weight of the pancreas. High dietary fibre content reduces the speed of starch absorption and thus may also reduce the stimulus for insulin and glucagon secretion (Hooda et al., 2010), thus possibly affecting pancreas size.

The duodenum was chosen as a reference section for evaluation of gut development and maturation in the present trial. Although it is understood that assessment of gut development differs in specific regions of the small intestine, the duodenum presents a higher correlation between RNA expression, RNA/DNA, RNA/protein and protein/DNA with age and faster and more intense development of the villus when compared to jejunum and ileum (Uni et al., 1998a). Birds fed high fibre diets had higher villus compared to birds fed diets with a low fibre concentration. Results in the literature are inconsistent regarding the effect of fibre on villus development. Rezaei et al. (2011) observed an increase in the villus height:crypt depth ratio of broilers when insoluble fibre was included in diets, while Rahmatnejad and Saki (2016) observed a reduction in villus height depending of the type of fibre included.

Part of this inconsistency may be related to the definition of the product tested in each trial. The effect of fibre increasing villus:crypt ration was observed by Rezaei et al. (2011) when an insoluble fibre was fed, while the effect observed by Rahmatnejad and Saki (2016) was related to the presence of a soluble fibre source. In the present trial rice bran was used as the fibre source, which is principally an insoluble source of fibre. Thus, it seems plausible that the effect of fibre stimulating villus growth is related to insoluble sources of fibre. Fibre reduces the metabolisable energy of the diet due to a dilution effect (Annison and Choct, 1991) and the increase in the villus height in the duodenum may be related to an attempt by the animal to increase nutrient absorption. In the present trial, birds fed high levels of fibre also increased feed intake but did not increase body weight gain, which suggests the fibre was a diluent in this trial even though the feeds were formulated to be isoenergetic. An increase in the villus height in young animals may support better performance in the long-term due to an increased ability of the bird to increase nutrient digestion and absorption. However, on the other hand, it also represents more energy and nutrients being allocated to a non-productive tissue if further improvement in performance is not observed.

As birds age, the gastrointestinal tract matures and becomes more specialized for nutrient absorption. An increase in crypt depth and villus height in the duodenum is observed as broilers age, resulting in an increased ratio between villus and crypt. The absorptive area, though, does not increase between hatch and d 4 as the increase in villus height is also associated with a big increase in the width and presence of fused villus that will affect this width, so the height advantage is offset by fewer villi per a similar area. The presence of fused villus with hypertrophic layer of enterocytes in the present trial between d 4 and 9 was characteristically similar to that observed during an inflammatory response caused by a coccidial challenge in birds between d 18 and 25 (Gholamiandehkordi et al., 2007). Teirlynck et al. (2009) also observed a higher proportion of fused villus in broilers fed a wheat/rye-based diet compared to broilers fed a corn-based diet and associate it to a higher NSP concentration in the former diet. However, this effect was reduced by the inclusion of zinc bacitracin, suggesting that the high viscosity caused by the soluble fibre present in wheat and rye may be causing a bacterial growth and an inflammatory response. It is unlikely that in the present trial the birds were suffering from a coccidial challenge as they were raised in cages with no access to their faeces, fused villus were observed when birds were too young to be suffering a coccidial challenge, coccidia oocysts were not observed in any lamina and no macroscopic symptom were observed. The characteristic similar to an inflammatory response observed in this trial could be related to the lumen content of the gastrointestinal tract creating a local inflammatory response either directly or through creation of a hyperosmotic solution due to the lack of nutrient absorption. It is possible that the fused villus characteristic observed in this trial is related to the hyperosmotic solution generated in the lumen, caused by the low digestibility of nutrients on young broilers.

Betaine inclusion reduced the width and increased the length of the villus, and consequently increased the absorptive area of the duodenum, although the proportion of villus with inflammatory characteristics was not affected. Betaine acts as an osmoprotectant, reduces inflammatory responses (Klasing et al., 2002) and apoptosis in enterocytes in hyperosmotic solution (Alfieri et al., 2002), and increases villus height and water flow in enterocytes (Kettunen et al., 2001a). It is possible that the presence of betaine helps the intestine to cope with the high osmotic pressure created by the presence of unabsorbed nutrients in the lumen, reducing the inflammatory response and helping the intestine to develop.

The number of enterocytes in mitosis on the villus, as determined by the positive reaction to the antibody Ki-67, reduces as the broilers age, thereby signalling cell differentiation and maturation of the villus (Willing and Van Kessel, 2009). Previous trials have already observed that, in contrast to mammals, birds usually maintain a certain number of enterocytes undergoing mitosis at the centre of the villus (Uni et al., 1998b). The proportion of enterocytes with a positive reaction, signifying the process of mitosis, in the present trial was lower than previously observed by other authors when a cyclin antibody (PCNA) was used (Geyra et al., 2001, Uni et al., 1998a). Although, a similar trend of a reduction in the concentration as birds age has been observed. This difference may be related to the antibody used to determine cells in mitosis, as previously research using PCNA antibody gave higher readings than that determined by Ki67 used in the present trial (Bologna-Molina et al., 2013). Antigen Ki-67 is a nuclear protein expressed in proliferating cells with maximum expression in G2 phase and during mitosis (Sobecki et al., 2016). PCNA, also known as cyclin is a protein that functions as a cofactor for DNA polymerase and increases rapidly in mid-G1, remaining elevated throughout the S-phase and decreases from G2 to G1 phase of the cell cycle (Uni et al., 1998b).

The number of enterocytes with positive reaction to the antibody Ki-67 on the villus did not change between hatch and d 4, but reduced afterwards at d 9 and 14. This effect may be related to the maturation process and the stimulus due to the inflammatory and protective response observed by the number of fused villus observed at younger ages. Betaine inclusion reduced the number of enterocytes with positive reaction at the villus and suggests that the inclusion of betaine may help the animal to overcome the challenge and speed up recovery after an inflammatory response and maintain organ function during this process.

5. Conclusion

Gut development and maturation is a key factor for animal performance during the pre-starter and starter phase. Transitory inflammatory responses during this period was observed and was reduced by the presence of betaine in the diet, suggesting that this damage may be related to a high concentration of non-absorbed nutrients in the lumen of the digestive tract. Betaine inclusion reduced the severity of this apparent inflammatory response and therefore supported an improvement in the absorptive area and villus height of the duodenum of birds up to d 14. The higher fibre diet increased feed intake and villus height, yet reduced pancreas relative weight, while not affecting body weight gain. This response was possibly due to a dilution effect of the fibre, reducing nutrient absorption and consequently stimulating villus growth to improve absorption rates. Betaine and insoluble fibre source can be used in diets for broilers between hatch and 14 d of age to stimulate gut development and reduce inflammation characteristics possibly caused by hyperosmotic solution in the lumen.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

To CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) and FINEP (Empresa Brasileira de Inovacao e Pesquisa) for the support on the purchase of equipments to the multiuser laboratory of conventional and confocal fluorescence microscopy used in the development of the present trial.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Adeola O., Xue P.C., Cowieson A.J., Ajuwon K.M. Basal endogenous losses of amino acids in protein nutrition research for swine and poultry. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;221:274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Adibmoradi M., Navidshad B., Jahromi M.F. The effect of moderate levels of finely ground insoluble fibre on intestine morphology, nutrient digestibility and performance of broiler chickens. Ital J Anim Sci. 2016;15:310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri R.R., Cavazzoni A., Petronini P.G. Compatible osmolytes modulate the response of porcine endothelial cells to hypertonicity and protect them from apoptosis. J Physiol. 2002;540:499–508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annison G., Choct M. Anti-nutritive activities of cereal non-starch polysaccharides in broiler diets and strategies minimizing their effects. World's Poult Sci J. 1991;47:232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bologna-Molina R., Mosqueda-Taylor A., Molina-Frechero N., Mori-Estevez A.D., Sanchez-Acuna G. Comparison of the value of PCNA and Ki-67 as markers of cell proliferation in ameloblastic tumors. Med Oral Patol Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2013;18:174–179. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choct M. Feed non-starch polysaccharides for monogastric animals: classification and function. Anim Prod Sci. 2015;55:1360–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb . Cobb-Vantress Inc.; 2015. 500 SF breeder management and Cobb 500 broiler performance.http://www.cobb-vantress.com/products/cobb-500 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Craig S.A.S. Betaine in human nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:539–549. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibner J.J., Knight C.D., Kitchell M.L., Atwell C.A., Downs A.C., Ivey F.J. Early feeding and development of the immune system in neonatal poultry. J Appl Poult Res. 1998;7:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund M., Bauer E., Wamatu J., Mosenthin R. Potential nutritional and physiological function of betaine in livestock. Nut Res Rev. 2005;18:31–48. doi: 10.1079/NRR200493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englyst H.N., Quigley M.E., Hudson G.J. Determination of dietary fibre as non-stach polysaccharides with gas-liquid chromatographic, high-performance liquid chromatographic or spectrophotometric measurement of constituent sugars. Analyst. 1994;119:1497–1509. doi: 10.1039/an9941901497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2011. Quality assurance for animal feed analysis laboratories. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No 14. Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Geyra A., Uni Z., Sklan D. Enterocyte dynamics and mucosal development in the posthatch chick. Poultry Sci. 2001;80:776–782. doi: 10.1093/ps/80.6.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami J., Ootbi A.A.A., Seidavi A.R., Meluzzi A., Tavaniello S., Maiorano G. Effects of in ovo administration of betaine and choline on hatchability results, growth and carcass characteristics and immune response of broiler chickens. Ital J Anim Sci. 2015;14:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gholamiandehkordi A.R., Timbermont L., Lanckriet A. Quantification of gut lesions in a subclinical necrotic enteritis model. Avian Pat. 2007;36:375–382. doi: 10.1080/03079450701589118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonnelli M., Strambini G.B. No effect of trimethylamine N-oxide on the internal dynamics of the protein native fold. Biophys Chem. 2001;89:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy O., Geyra A., Barak M., Uni Z., Sklan D. Early posthatch starvation decreases satellite cells proliferation and skeletal muscle growth in chicks. J Nut. 2000;130:858–864. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooda S., Matte J.J., Vasanthan T., Zijlstra R.T. Dietary purified oat B-glucan reduces peak glucose absorption and portal insulin release in portal-vein catheterized grower pigs. Live Sci. 2010;134:15–17. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.122721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Sun Q., Li X., Wang M., Cai D., Li X., Zhao R. Ovo injection of betaine affects hepatic cholesterol metabolism through epigenetic gene regulation in newly hatched chicks. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert A., Cauliez B., Chedeville A., Husson A., Lavoinne A. Osmotic stress, a proinflammatory signal in Caco-2 cells. Biochimie. 2004;86:533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iji P.A., Saki A., Tivey D.R. Body and intestinal growth of broiler chicks on a commercial starter diet. 1. Intestinal weight and mucosal development. Br Poult Sci. 2001;42:505–513. doi: 10.1080/00071660120073151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Moreno E., Gonzalez-Alvarado J.M., Gonzalez-Serrano A., Lazaro R., Mateos G.G. Effect of dietary fibre and fat on performance and digestive traits of broilers from one to twenty-one d of age. Poultry Sci. 2009;88:2562–2574. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen H., Peuranen S., Tiihonen K. Betaine aids in the osmoregulation of duodenal epithelium of broiler chicks, and affects the movement of water across the small intestinal epithelium in vitro. Comp Biochem Physiol. 2001;129:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen H., Tiihonen K., Peuranen S., Saarinen M.T., Remus J.C. Dietary betaine accumulates in the liver and intestinal tissue and stabilizes the intestinal epithelial structure in healthy and coccidian-infected broiler chicks. Comp Biochem Physiol. 2001;130:759–769. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisielinski K., Willis S., Prescher A., Klosterhalten B., Schumpelick V. A simple new method to calculate small intestine absorptive surface in the rat. Clin Exp Med. 2002;2:131–135. doi: 10.1007/s102380200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasing K.C., Adler K.L., Remus J.C., Calvert C.C. Dietary betaine increased intraepithelial lymphocytes in the duodenum of coccidian-infected chicks and increases functional properties of phagocytes. J Nut. 2002;132:2274–2282. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen K.E.B. Fiber and nonstarch polysaccharides content and variation in common crops used in broiler diets. Poultry Sci. 2014;93:2380–2393. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-03902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Sinha A.K., Makkar H.P.S., De Boeck G., Becker K. Dietary roles of non-starch polysaccharides in human nutrition: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52:899–935. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.512671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite P.R.S.C., Leandro N.S.M., Stringhini J.H., Café M.B., Gomes N.A., Jardim Filho R.M. Desempenho de frangos de corte e digestibilidade de rações com sorgo ou milheto e complex enzimático. Pesq Agrop Bras. 2011;46:280–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lilburn M.S., Loeffler S. Early intestinal growth and development of poultry. Poultry Sci. 2015;94:1569–1576. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorka A., Santin E., Dahlke F., Boleli I.C., Furlan R.L., Macari M. Posthatching water and feed deprivation affect the gastrointestinal tract and intestinal mucosa development of broiler chicks. J Appl Poult Res. 2003;12:483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J.O., Southern L.L. The effect of dietary betaine in Eimeria acervulina-infected chicks. Poultry Sci. 2000;79:60–65. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran E.T., Jr. Nutrition of the developing embryo and hatchling. Poultry Sci. 2007;86:1043–1049. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento G.M., Leandro N.S.M., Café M.B. Performance and intestinal characteristics of broiler chicken fed diet with glutamine in the diet without anticoccidials agents. Rev Bras Saúde Prod Anim. 2014;15:637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Obst B.S., Diamond J. Ontogenesis of intestinal nutrient transport in domestic chickens (Gallus gallus) and its relation to growth. Auk. 1992;109:451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmatnejad E., Saki E.E. Effect of dietary fibres on small intestine histomorphology and lipid metabolism in young broiler chickens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2016;100:665–672. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakha A., Saulnier L., Aman P., Anderson R. Enzymatic fingerprinting of arabinoxylan and B-glucan in triticale, barley and tritordeum grains. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;90:1226–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratriyanto A., Mosenthin R., Bauer E., Eklund M. Metabolic, osmoregulation and nutrition functions of betaine in monogastric animals. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2009;22:1461–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei M., Karimi A., Torshizi M.A., Rouzbehan Y. The influence of different levels of micronized insoluble fibre on broiler performance and litter moisture. Poultry Sci. 2011;90:2008–2012. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostagno H.S. 3rd ed. UFV; Viçosa: 2011. Tabelas brasileiras para aves e suínos. [Google Scholar]

- Rostagno H.S., Pack M. Can betaine replace supplemental dl-methionine in broiler diets? J App Poult Res. 1996;5:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Schwahn B.C., Hafner D., Hohlfeld T., Balkenhol N., Laryea M., Wendel U. Pharmacokinetics of oral betaine in healthy subjects and patients with homocystinuria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:6–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L., Guais A., Pooya M., Abolhassani M. Is inflammation a consequence of extracellular hyperosmolarity? J Inflamm. 2009;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobecki M., Mrouj K., Camasses A. The cell proliferation antigen Ki-67 organises heterochromatin. eLife. 2016;5:e13722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svihus B., Juvik E., Hetland H., Krogdahl A. Causes for improvement in nutritive value of broiler chicken diets with whole wheat instead of ground wheat. Br Poult Sci. 2004;45:55–60. doi: 10.1080/00071660410001668860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teirlynck E., Bjerrum L., Eeckhaut V. The cereal type in feed influences gut wall morphology and intestinal immune cell infiltration in broiler chickens. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1453–1461. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509990407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uni Z., Gal-Garber O., Geyra A., Sklan D., Yahav S. Change in the growth and function of chick small intestine epithelium due to early thermal conditioning. Poultry Sci. 2001;80:438–445. doi: 10.1093/ps/80.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uni Z., Ganot S., Sklan D. Posthatch development of mucosal function in the broiler small intestine. Poultry Sci. 1998;77:75–82. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uni Z., Platin R., Sklan D. Cell proliferation in chicken intestinal epithelium occurs both in the crypt and along the villus. J Comp Physiol. 1998;168:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s003600050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willing B.P., Van Kessel A.G. Intestinal microbiota differentially affect brush border enzyme activity and gene expression in neonatal gnotobiotic pig. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2009;93:586–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2008.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]