INTRODUCTION

Sudden unexpected death (SUD) is a common syndrome that has not been well-characterized in urban and rural populations. Previous work has found a higher incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD)1 in rural populations. However, as strict criteria for SCD based on reported cause and timing of death often exclude deaths from non-cardiac causes that have potential epidemiological overlap with SCD, it is important to take an inclusive approach.2 As rural areas are also challenged with shortages of primary care providers, mental health providers, and health insurance,3 we hypothesize that the incidence of SUD is higher in rural counties than in urban counties due to discrepancies in these measures of health care access. In this study, we (1) compare the incidence of SUD between rural and urban counties in North Carolina (NC) and (2) determine if specific measures of health care access are independent predictors of SUD. In these ways, this work is a preliminary step towards risk stratification for the development of targeted, population-level preventive strategies.

METHODS

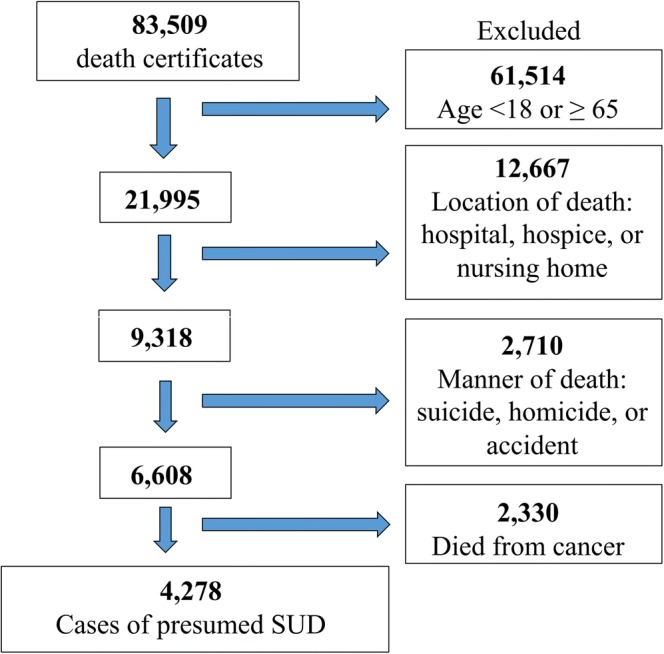

Statewide death certificate data for NC for 2014 were screened to identify cases of presumed SUD among state residents. We sought to identify cases of premature, unexpected, natural deaths that occurred out of hospital, regardless of the cause of death or timing of death relative to the onset of symptoms (Fig. 1). For each county, the incidence of SUD was calculated per 100,000 persons. Counties were divided into three urban-rural categories based on the percent of the county population living in an urbanized area according to the 2010 census, with urban population < 20% designated as highly rural, 20–60% designated as mixed urban-rural, and > 60% designated as highly urban. Poisson regression models were used to analyze the effects of health care access measures, rural status, and other demographic, socioeconomic, and health variables4 on the county incidence of SUD. Multiple Poisson regression models with a backward variable selection method were used to identify county-level variables that independently predict county SUD incidence statewide and for each urban-rural category. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the stepwise screening process used to identify cases of sudden unexpected death. SUD, sudden unexpected death.

RESULTS

A total of 83,509 death certificates collected in 2014 for the 100 NC counties were screened, yielding 4278 cases of SUD (Fig. 1). The mean incidence of SUD was greatest in highly rural counties (100/100,000), followed by mixed urban-rural counties (85/100,000) and highly urban counties (68/100,000). While the univariate regression found several variables to be associated with a high county incidence of SUD (Table 1), the multiple regression model for predicting a high county incidence of SUD only identified the following variables as significant: having a higher percent of the population age 65 or older, lower percent of African-Americans, and lower median household income. For highly rural counties only, lower median household income was significant. Furthermore, although nonmedical use of pain relievers was not initially found to be a significant predictor of SUD, an exploratory analysis found that this variable became significant when included in the state-level multiple regression model.

Table 1.

Univariate and Multiple Poisson Regression Results for the Effects of County-Level Variables on the Incidence of Sudden Unexpected Death in North Carolina

| Variable | Univariate regression | Multiple regressions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 95% CI | P value | IR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Mixed urban-rural (between 20 and 60% urban)* | 1.46 | 1.22, 1.74 | < 0.001 | 1.03 | 0.87, 1.22 | 0.73 |

| Highly rural (less than 20% urban)* | 1.67 | 1.40, 2.00 | < 0.001 | 1.06 | 0.85, 1.31 | 0.63 |

| PCP rate† | 0.99 | 0.99, 0.99 | < 0.001 | |||

| MHP rate† | 1.00‡ | 0.99, 1.00 | < 0.001 | |||

| % Uninsured† | 1.05 | 1.02, 1.09 | 0.006 | |||

| % Age ≥ 65 | 1.05 | 1.04, 1.07 | < 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | 0.02 |

| % Female | 0.95 | 0.88, 1.03 | 0.25 | |||

| % African-American | 0.99 | 0.98, 0.99 | < 0.016 | 0.99 | 0.99, 1.00 | 0.003 |

| % Non-Hispanic White | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 | < 0.001 | |||

| % Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.93, 0.98 | 0.001 | |||

| % with some college (or more) | 0.98 | 0.97, 0.98 | < 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Median household income (per 10k) | 0.98 | 0.97, 0.98 | < 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | 0.04 |

| % Married | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.03 | 0.07 | |||

| % Obesity | 1.04 | 1.02, 1.06 | < 0.001 | |||

| % Smoking | 1.06 | 1.01, 1.11 | 0.02 | |||

| Illicit drug dependence or abuse in past year (%) | 0.89 | 0.80 1.01 | 0.06 | |||

| Nonmedical use of pain relievers in past year (%) | 1.44 | 1.28, 1.61 | < 0.001 | |||

P < 0.05 was considered significant. For the multiple Poisson regressions, a backward variable selection was used to identify the most significant county-level variables in a model predicting the incidence of sudden unexpected death (SUD); the variable selection process may lead to the inclusion of some nonsignificant variables

IR, incidence ratio; PCP, primary care provider; MHP, mental health provider

*Incidence ratios calculated using the highly urban category (> 60% urban population) as the reference group

†Measures of health care access

‡Rounded up from 0.998

DISCUSSION

Rural counties in NC have a higher incidence of SUD than urban counties. The higher incidence of SUD in rural counties is best predicted by lower median household income rather than health care access measures (insurance status, the presence of primary care or mental health providers), education level, and health behaviors (smoking, obesity, illicit drug abuse). This finding is consistent with previous work showing that compared to urban residents, rural residents find costs to be more prohibitive to accessing care despite Medicare and Medicaid coverage5 and report fewer doctor’s visits even after controlling for per capita number of physicians.6 It appears that increasing the number of easily accessible primary care services available may have limited benefit without reducing costs or increasing patients’ financial means, especially in rural areas. Identifying mechanisms through which increasing income affects utilization of existing health care resources and subsequent health status may shed light on potential interventions, such as economic development, to prevent SUD in rural areas. Nonmedical use of pain relievers also appears to be an important mediator of SUD. Future research on strategies for reducing SUD in rural areas will require a multifaceted approach that addresses not only socioeconomic factors, but also interrelated variables such as addiction prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. John P. Mounsey for assistance with manuscript review.

Funding

The project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001111; additional funding was provided through grant number T35-DK007386 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

None.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hua W, Zhang LF, Wu YF, Liu XQ, Guo DS, Zhou HL, et al. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in China: analysis of 4 regional populations. J American Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(12):1110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(3):618–20. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolin JN, Bellamy GR, Ferdinand AO, Vuong AM, Kash BA, Schulze A, et al. Rural Healthy People 2020: New Decade, Same Challenges. J Rural Health. 2015;31(3):326–33. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute County Health Rankings 2016.

- 5.Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum G, Horner R. Health services access and use among older adults in North Carolina: urban vs rural residents. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(10):1384–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.10.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson SL, Fleishman JA. Rural-urban differences in usual source of care and ambulatory service use: analyses of national data using Urban Influence Codes. Med Care. 2003;41(7 Suppl):Iii65–iii74. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000076053.28108.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]