Abstract

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has a central role in maintaining and strengthening neuronal connections and to stimulate neurogenesis in the adult brain. Decreased levels of BDNF in the aging brain are thought to usher cognitive impairment. BDNF is stored in dense core vesicles and released through exocytosis from the neurites. The exact mechanism for the regulation of BDNF secretion is not well understood. Munc18-1 (STXBP1) was found to be essential for the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles, but its involvement in BDNF secretion is not known. Interestingly, neurons lacking munc18-1 undergo severe degeneration in knock-out mice. Here, we report the effects of BDNF treatment on the presynaptic terminal using munc18-1-deficient neurons. Reduced expression of munc18-1 in heterozygous (+/−) neurons diminishes synaptic transmitter release, as tested here on individual synaptic connections with FM1-43 fluorescence imaging. Transduction of cultured neurons with BDNF markedly increased BDNF secretion in wild-type but was less effective in munc18-1 +/− cells. In turn, BDNF enhanced synaptic functions and restored the severe synaptic dysfunction induced by munc18-1 deficiency. The role of munc18-1 in the synaptic effect of BDNF is highlighted by the finding that BDNF upregulated the expression of munc18-1 in neurons, consistent with enhanced synaptic functions. Accordingly, this is the first evidence showing the functional effect of BDNF in munc18-1 deficient synapses and about the direct role of munc18-1 in the regulation of BDNF secretion. We propose a molecular model of BDNF secretion and discuss its potential as therapeutic target to prevent cognitive decline in the elderly.

Keywords: BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) secretion, munc18-1, Brain aging and dementia, Synaptic vesicle recycling, Neurotransmission, FM 1-43 fluorescence microscopy

Introduction

Aging is a major risk factor for cognitive impairment (Hancock et al. 2017; Katz et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2018; Logan et al. 2018; Robinson et al. 2018; Shobin et al. 2017; Tucsek et al. 2017; Ungvari et al. 2018) and is a main focus of the new geroscience field (Sierra and Kohanski 2017). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is known as a pro-survival factor, promotes neuronal differentiation during the structural development of central nervous system (Cohen-Cory et al. 2010), and serves an important role in synaptic plasticity (Poo 2001). Lower BDNF levels with aging are a well characterized phenotype in mammals including rats, mice, cats, monkeys, and humans (Pal et al. 2014; Shetty et al. 2004; Tong et al. 2015) (but see (Shetty et al. 2013). Importantly, a steady decline of BDNF levels with age is observed in the elderly and correlated with cognitive impairment in women patients (Komulainen et al. 2008). Furthermore, both mice lacking of BDNF or its receptor TrkB expression have spatial learning deficits and decreased LTP in the CA1 hippocampal region (Korte et al. 1995; Minichiello 2009; Pozzo-Miller et al. 1999). BDNF gene variants of SNP rs6265 and rs7103411 were associated with lower memory and perceptual speed in women (Laing et al. 2012). It is well established that BDNF augments learning and memory processes both in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex through strengthening long-term potentiation (LTP) (Figurov et al. 1996; Kang and Schuman 1995; Korte et al. 1995). How BDNF regulates neurotransmission remains still elusive in many details of the molecular mechanism.

Synaptic vesicle release is a key step in neurotransmission. Precise targeting of vesicular release (spatial) and proper execution of membrane fusions (temporal) are two key aspects of exocytosis in eukaryotic cells. This mechanism evolved to a remarkable sophisticated state in neurons for synaptic transmitter release. Recently, observations from genetically engineered models draw the attention to the core machinery of exocytosis the core complex formed by SNARE proteins (syntaxin, SNAP-25, and synaptobrevin) and their essential interacting partner, munc18 (sec1). Munc18-1 is also known as syntaxin-binding protein (STXBP1) or neuronal sec1 (nSec1) or p67 (67 kDa protein) (many other names of this protein refer to its orthologs in various species like “rat brain Sec1–rbSec1 referring to the sec1 in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae; or mammalian unc18 referring to unc-18 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans). Munc18-1 has three major interactions with the members of the exocytosis complex: its two different binding to syntaxin either in the closed or to the open conformation of syntaxin-1; a third binding mode is essential in facilitating vesicle priming through proof reading the core complex of SNARE proteins forming during synaptic exocytosis (Deák et al. 2009; Südhof and Rothman 2009). Excitatory synapses lacking munc18-1 are perfectly silent, with no detectable glutamate release (Deák et al. 2009; Verhage et al. 2000) and mutations that disrupt munc18 binding to the SNARE complex severely impair vesicular transmitter release (Deák et al. 2009). Importantly, synaptic activity is an important driving force for secretion of neurotrophic factors (Deák and Sonntag 2012; Minichiello 2009) as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (Cao et al. 2011) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Shimojo et al. 2015).

It was supposed early on that BDNF may have synaptic effects, possibly enhancing pre-synaptic neurotransmitter release (Kang and Schuman 1995). In spite of compelling evidence that munc18-1 plays a vital role in synaptic vesicular exocytosis, however, it is still unknown whether the effects of BDNF are related to munc18-1 in presynaptic terminal.

In this context, we have hypothesized that the effects of BDNF on synaptic vesicular trafficking and neurotransmitter release might be related to the role of munc18-1. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the functional restoration of synaptic release in munc18-1-deficient neurons of the munc18-1−knock-out (KO) mice by treatment with genetically augmented BDNF expression in cortical neurons. We have fund that BDNF-induced enhanced synaptic recycling in presynaptic terminals of cultured neurons with live cell fluorescence imaging. Taken together, through this study, we have demonstrated that BDNF plays distinct role in enhancing synaptic functions that involves the upregulation of munc18-1 expression in neurons.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and primary neural cultures

Munc18-1 KO was generated as described (Deák et al. 2009; Verhage et al. 2000). Munc18-1 KO mice were bred by crossing heterozygous mutant munc18-1 KO mice. Cortical neurons from littermate mice at embryonic day 16 to 18 were dissociated by trypsin (5 mg/ml for 5 min at 37 °C), triturated with a siliconized Pasteur pipette, and plated onto 12 mm coverslips coated with Matrigel (~ 12 coverslips/cortex) (Deák et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2013). Neurons were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 95% air, 5% CO2 in minimal essential media (MEM) containing 5 g/L glucose, 0.1 g/L transferrin, 0.25 g/L insulin, 0.3 g/L glutamine, 5–10% heat inactivated FCS, 2% B-27 supplement, and 1 μM cytosine arabinoside, and used after 5~18 days in vitro (div). Basic characterization of the cultures did not reveal any difference between WT and munc18-1 KO heterozygous cultures in cell viability or synaptic density.

Constructing a BDNF vector

Lentiviral expression vectors to express full-length mouse BDNF and BDNF tagged with cerulean fluorescence protein were prepared using pLenti-TOPO v6.3 vector (Invitrogen) and full-length mouse BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor isoform 2 precursor from Mus musculus; NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_001272348.1) amplified from cDNA library. First, full length BDNF was generated by PCR to introduce BamHI- and SalI-cloning sites at the N- and C-termini with custom designed primers. These new restriction sites of BamHI and SalI were used for subcloning BDNF into the lentiviral vector. For the cerulean fusion protein, modified primer was used to remove the stop codon of BDNF, which was inserted to the N-terminus of cerulean in the shuttle vector for virus production, and final construct verified by sequencing.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral production and transduction method was as described previously (Deák et al. 2009). Briefly, constructs were co-transfected with plasmids for viral envelop and enzymes into HEK 293 cells using of FuGENE6 transfection system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer’s specifications, and lentivirus containing culture medium was harvested 2 days later, filtered through 0.45 μm pores, and immediately used for infection or frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C. Cortical cultures were infected at day one in vitro by adding 300 μL of viral suspension to each well.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryonic brain tissues were obtained from surgically sacrificed pregnant mice. The enucleated brains were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h at 4 °C. The brains were then transferred three times to 12%, 16%, and 18% sucrose in 0.05 M PBS for 30 min at 4 °C respectively for cryoprotection. The brains embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek) were cut on the coronal plane at 10 μm thicknesses with a cryostat (Leica CM1850, Leica) and attached onto gelatin-coated slide.

For the immunofluorescence staining, anti-munc18-1 (1:500, 116,002, Synaptic Systems) was used as neurite outgrowth and synaptic markers. First, brain sections were washed three times in 0.05 M PBS for 5 min. Nonspecific reactivity was blocked by adding albumin (Sigma) and 1.5% goat serum (Vector Lab) into the primary antibody diluting solution. After the incubation of the primary antibody for 24 h at 4 °C, the brain sections were rinsed three times with 0.05 M PBS for 5 min and incubated in fluorescence tagged secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 555, goat anti-rabbit IgG, A21424, Invitrogen, 1:200) for 90 min at RT. The brain sections were washed again three times for 5 min after the termination of secondary antibody incubation. Finally, nuclei of neurons were counter-stained with DAPI (ABBOT Molecular) and immediately inspected with the laser confocal microscope (LSM-700, Carl Zeiss) equipped with associated software of ZEN2009 (ver. 5.5.0.375 Car Zeiss). Standard master gain was set for rhodamine to 520 and for DAPI fixation to 770.

Enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay (ELISA)

Samples were extracted from the culture media (200 μl per well) and cytoplasmic fraction of the cortical neurons at 7 and 14 div. Samples were treated with protein inhibitor (1 mg/mL) (Sigma). ELISA procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ChemiKine™ Sandwich ELISA Kit; Chemicon), and the results were obtained by multiwall plate reader (model 680, Bio-RAD) at 450 nm.

Western blotting

To isolate proteins from the brain tissue, cerebral cortices were enucleated from brain of embryonic day 18 mice and homogenized with 5X sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 30% glycerol, 5% beta-mercapto-ethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, 10% SDS). In case of cultured cortical neurons, pellets from the cultured cells were manually homogenized (vortexing in lysis buffer No. 17081, PRO-PREP™ Protein Extraction Solution, iNtRON). Homogenates were centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 30 min, and the resulting supernatants were isolated. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay was used to determine protein concentration. Lysates from the cultured neurons were resuspended in 5X SDS-PAGE loading buffer (S2002, Biosesang), separated by electrophoresis on SDS-PAGE gels (10 wells; Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore). Transfer was performed at 4 °C in a buffer containing 23 mM Tris, 193 mM glycine, and 20% methanol (HT2033, Biosesang). After SDS-PAGE, transferred membranes were blocked by 5% skim milk for 12 h at 4 °C.

For primary antibody reaction, rabbit monoclonal anti-munc18-1 (1:2000, 116,002, Synaptic Systems), and anti-GAPDH (1:2000, 2118, rabbit monoclonal, cell signaling) as loading control were added to membranes and incubated overnight at 4 °C. HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody (31,460, Thermo) was used at a dilution of 1:5000 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After the reaction with secondary antibody, signals were enhanced with chemiluminescence (ECL) solution (W1015, Promega) by exposing film (EA8EC, Agfa) into the autoradiography cassette and finally detected by the image detection system (LAS 4000, GE). Densitometric analysis was performed with Image J software (version 1.48). The ratio of individual proteins to GAPDH was then determined, and these values were compared for statistical analysis.

Fluorescence imaging with FM1-43

Modified Tyrode’s bath solution was used in all experiments [in mM 150 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES-NaOH pH 7.4, and 2 CaCl2 (~ 310 mOsm)], and was supplemented with 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM AP-5 to block recurrent neuronal network activity. Neurons were incubated with the depolarizing Tyrode solution with 46 mM KCl in the presence of 0.008 mM N-(3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-(4-(dibutylamino)styryl) pyridinium dibromide (FM1–43; Invitrogen) for 1.5 min, and then washed for 10 min in dye-free Tyrode’s solution lacking Ca2+ to minimize transmitter release. In all experiments, isolated boutons (~ 1 μm2) were selected for analysis. Synaptic vesicle fusion was induced by depolarization using gravity perfusion (~ 3 mL/min) of Tyrode’s solution containing 2 mM Ca2+ and 90 mM KCl (substituted for NaCl) for 90 s. Subsequently, after 1 min perfusion with Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution, full destaining was achieved by a 1 min perfusion with 90 mM KCl Tyrode’s solution again and repeated this way two more times. Fluorescence images were acquired with a cooled CCD camera (Cascade II, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) during illumination (1 Hz and 200 ms) at 480 ± 20 nm (505 dichroic long pass and 534 ± 25 bandpass) via an optical switch (DG-4, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and analyzed using Metafluor Software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyville, CA). Fluorescence levels remaining after four consecutive rounds of high K+ application were subtracted as background from all fluorescence images.

Statistical analysis

Independent Student’s t test for repeated measures was applied for ELISA and Western blotting. In case of FM-dye imaging, one way ANOVA test was applied in combination with post hoc Tukey test to determine significance. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p values of less than 0.05 were considered as significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R-program software (version 2.15.2), and data shown as means ± SEMs.

Results

Characterizations of munc18-1 KO heterozygous mice as model of synaptic dysfunction and impaired BDNF secretion

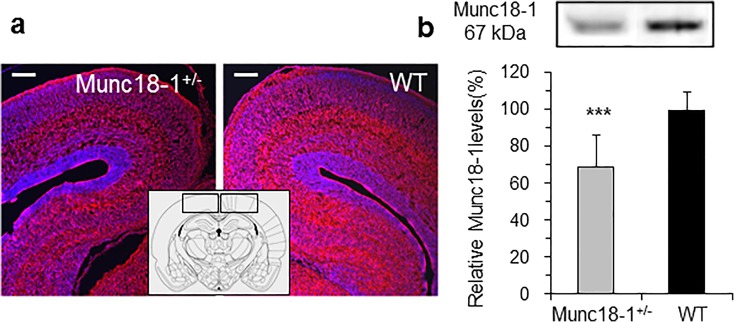

First we investigated the effect of one allele munc18-1 deletion on its expression in the mouse brain. Munc18-1 immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortical areas of adult munc18-1 heterozygous mice was reduced according to average fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1a). Expression levels in the cerebral cortex were further evaluated via Western blot analysis and munc18-1 protein levels were found to be significantly reduced in heterozygous neurons (average to 68%) in comparison to those of WT (Fig. 1b). This result is also in good accordance with the immunohistochemistry data and confirms recent expression results from this mouse model (Orock et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the effect of reduced munc18-1 levels on BDNF secretion in cortical neurons. a Immunofluorescence of munc18-1 in the cerebral cortical region. Immunoreactivities in munc18-1 heterozygous mice were markedly decreased in comparison to those of littermate wild-type mice (n = 24 slides, munc18-1 was detected by Sy116 002 Ab (Synaptic System, Germany) and nuclei counterstained with DAPI). Scale bars, 100 μm. Inset illustrates the region of the analyzed cortical area. b Western blot analysis of munc18-1 levels from the cerebral cortex. Note, amount of munc18-1 from the heterozygous (+/−) are depicted as relative levels in percentage of the wild-type (WT, ***P < 0.001 calculated from triplicates)

BDNF levels in the neuronal cultures of WT and munc18-1 heterozygous mice

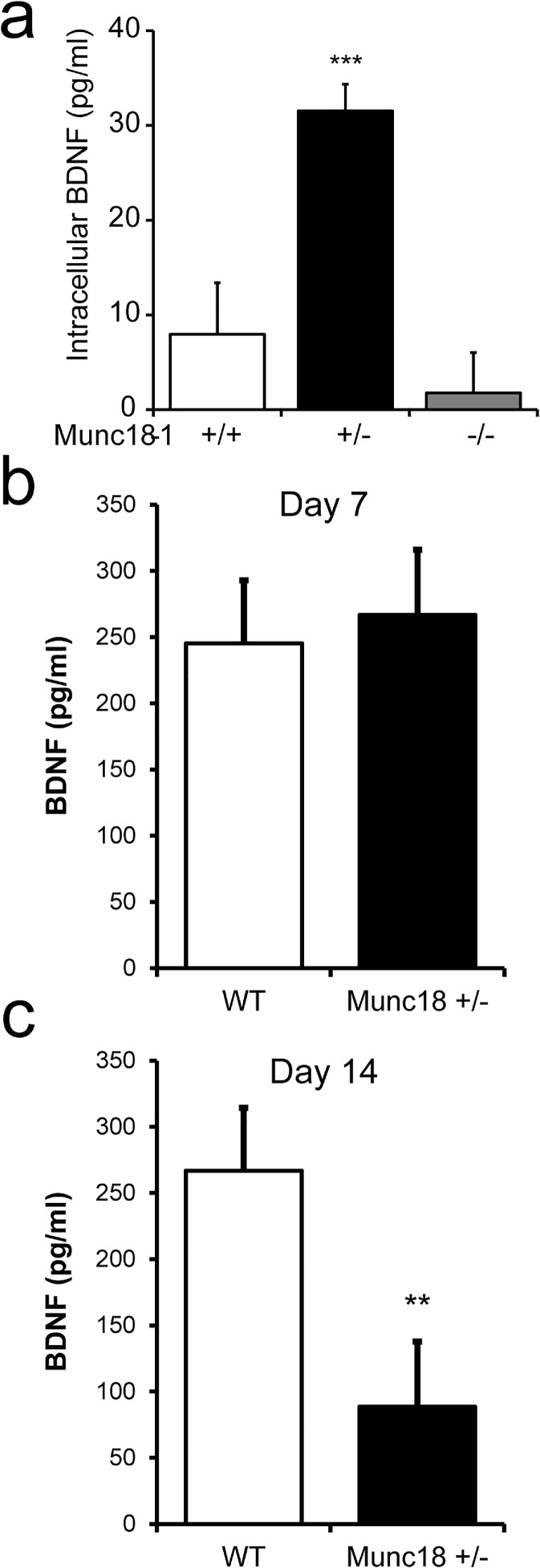

Second, we analyzed the synthetized and stored amount of BDNF in the cultured neurons with ELISA assay and found that amounts of BDNF in the heterozygous neurons is more than triple of that detected in WT cells (Fig. 2a). As negative control, we used homozygous munc18-1 −/− cultures, which have no or only very few neurons surviving but plenty astrocytes, and detected no intracellular BDNF in these KO cultures. Next, we applied the same ELISA assay to measure the secreted amount of BDNF from the same cultures. The BDNF level turned out to be below the detection threshold of this assay (estimated at 5 pg/ml). Therefore, we have applied an approach for boosting BDNF expression levels using transduction with a BDNF-containing vector. Another advantage of this approach over applying BDNF was that we were able to simultaneously assess BDNF secretion and its effect on neurotransmission.

Fig. 2.

Intracellular and secreted amount of BDNF differs in WT and munc18-1+/− KO neurons. a Amounts of intracellular BDNF quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) from cytoplasm fractions of WT, heterozygous munc18-1+/− and homozygous munc18-1−/− KO cultures (n = 3, *** p < 0.001, t test). b Amounts of BDNF quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) from culture medium fractions of WT and munc18-1 KO+/− cortical cultures following transduction with BDNF-expressing lentivirus at day 1 and analyzed as indicated on day 7 or c on day 14. Note that the amount of BDNF in medium fractions was markedly increased by BDNF over-expression in WT both at day 7 and 14 but declined in heterozygous groups by day 14 (n = 3 independent cultures, BDNF levels measured in duplicates; ** p < 0.01, t test)

Effect of transduction with a BDNF-expressing vector

Transduction with the BDNF-containing lentiviral particles resulted in a robust increase in production and secretion of BDNF. The culture medium of WT neurons after transduction with BDNF lentiviral treatment contained around 250 pg/ml BDNF (Fig. 2b). Neurons treated with only cerulean expressing lentiviral particles served as controls and had no increase in BDNF levels in culture medium (data not shown). BDNF content remained elevated DIV 14 in wild-type cultures to a level above 250 pg/ml (Fig. 2c). Surprisingly, BDNF levels rose also markedly in munc18-1 heterozygous cultures at DIV 7 after BDNF over-expression. Whereas the amount of BDNF was similarly high at DIV 14 and DIV 7 in WT, BDNF level declined significantly at DIV 14 in heterozygous culture media samples, but still remained considerably elevated (around 80 pg/ml), above the untreated levels (Fig. 2c). These data indicate that transduced BDNF gene not only worked properly, but the expressed BDNF proteins were secreted early on. While BDNF secretion steadily rose in WT controls after transduction, in munc18+/− cultures BDNF secretion was transient resulting in a decline by DIV 14. To better understand this process, we have assumed that BDNF treatment affected synaptic activity and could upregulate munc18 expression. The following studies below have addressed these possibilities.

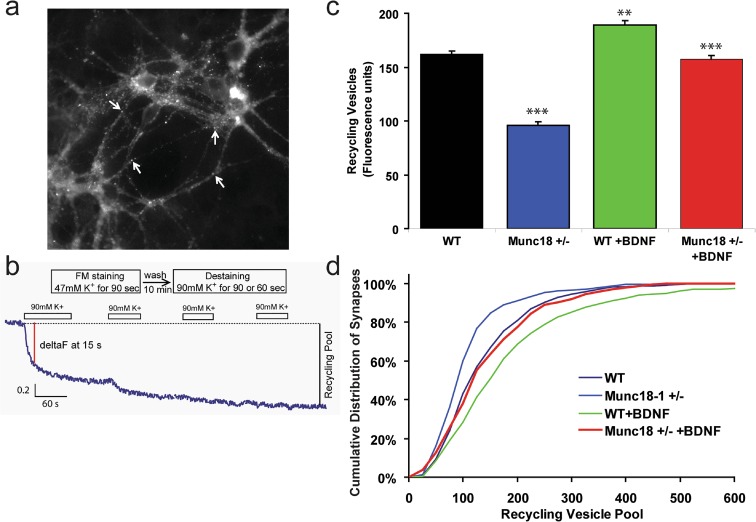

BDNF rescues synaptic function in munc18-1+/− neurons

When analyzed with electrophysiological methods, postsynaptic currents in munc18-1+/− neurons were reported to be weaker than in WT controls (Toonen et al. 2006). A possible pre-synaptic component was suggested in this synaptic dysfunction, but lack of direct functional test of synaptic recycling left the question unanswered. Therefore, next, we tested whether BDNF is able to rescue the significantly impaired vesicle release from munc18-1+/− synapses. To avoid the complication of increased synapse formation, we chose to record vesicle release in individual synaptic connections with FM1-43-fluorescence imaging. We were able to effectively load synapses both in WT and heterozygous cultures with a 90 s depolarization protocol and visualize active synaptic boutons (Fig. 3a, b). Indeed, our imaging data (Fig. 3c, d) consistently indicated that the average vesicular recycling pool of synaptic boutons was lowered in munc18-1 deficient heterozygous neurons in comparison to wild-types (see average fluorescence values of ΔF = 96 vs.162, respectively, on Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Augmented synaptic vesicle recycling after BDNF treatment. a Selection of synaptic boutons from the networks of primary cultured cortical neurons. Isolated boutons with areas not more than 1 μm2 (a few examples pointed to with arrows) were selected for analysis. b Experimental details of FM 1-43 fluorescence imaging procedures. Fluorescence levels from the selected synaptic boutons were measured through four consecutive rounds of depolarization with high potassium (90 mM K+). c Average values of synaptic vesicular recycling pool in each experimental groups (synapses analyzed for WT = 427; munc18-1+/− = 225; WT + BDNF = 993; munc18-1+/− + BDNF = 436; statistical significance as **p < 0.01, WT vs. WT + BDNF; ***p < 0.001, WT vs. munc18-1+/−; WT + BDNF vs. munc18-1+/−; WT + BDNF vs. munc18-1 +/− + BDNF; N.S., WT vs. munc18-1+/− + BDNF by one way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test). Error bars depict S.E.M. d Cumulative graph depicts recycling pool sizes in all analyzed synapses. Note that BDNF treatment increased synaptic release in munc18 +/− neurons to the same activity level as detected in WT controls

Next, we transduced the cultured neurons with BDNF construct to test BDNF effect on synaptic transmitter release using the FM fluorescence labeling paradigm. In the WT neurons, value of the average recycling pool was significantly higher in BDNF over-expressing neurons than control after 10 days of transduction (Fig. 3c). In heterozygous neurons, the average recycling pool size increased dramatically (from 96 to 158 in average) by BDNF expression. With this 60% upshot, vesicle release in munc18-1 +/− neurons perfectly matched that from control WT cells. Interestingly, BDNF treatment further increased synaptic release in WT neurons by less than 20%. However, we provide evidence that genetically introduced BDNF restored the presynaptic function which had been impaired by deficient munc18-1 at least up to wild-type control neurons. Differences of average recycling pool values and statistical significances among the groups were summarized in the legend of Fig. 3.

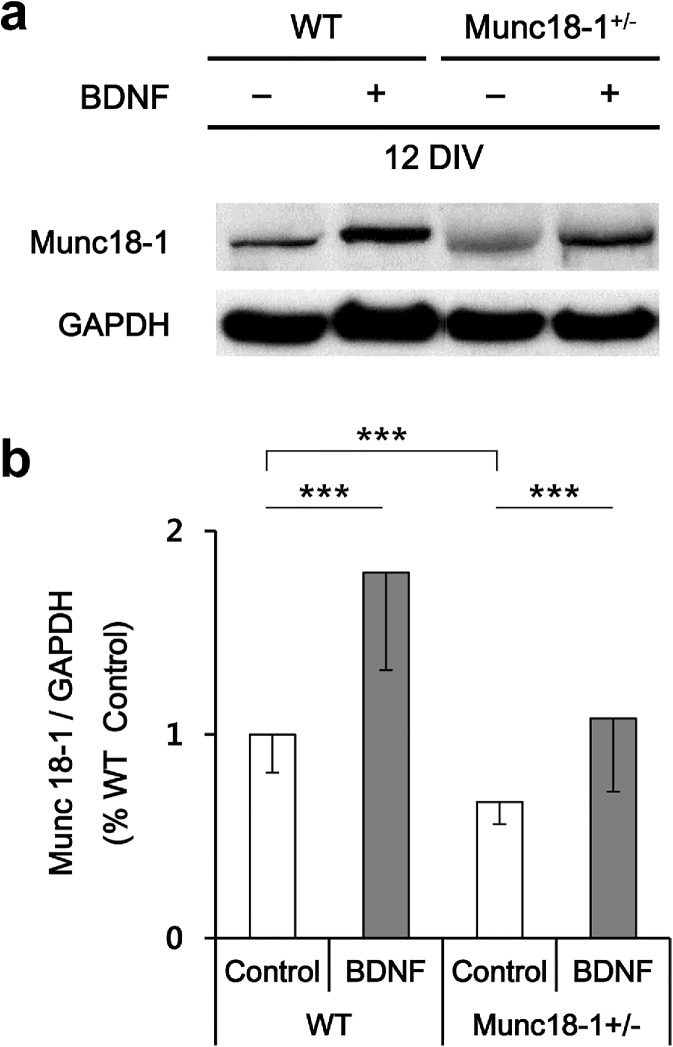

BDNF upregulates munc18-1 expression levels in both WT and munc18-1 heterozygous neurons

To test whether BDNF upregulates munc18-1 expression, we measured amounts of munc18-1 from cultured neurons by Western blotting. After correcting for loading quantity as measured with GAPDH levels (Fig. 4), all the amounts of munc18-1 were normalized to WT control. The average level of munc18-1 in heterozygous untreated neurons was significantly lower than in WT controls (1.73 vs. 2.84, respectively). This means an average of 62% relative levels of munc18-1 in heterozygous neurons compared with WT; a good match to our findings from cortical brain samples. BDNF over-expression increased amounts of munc18-1 significantly in both WT and munc18-1 heterozygous cultures in comparison to BDNF non-treated controls. The average level of munc18-1 was markedly raised by 56% in average in WT neurons (p < 0.01). Munc18-1 expression was also effectively induced in the munc18-1 heterozygous group, reaching in average 69% higher levels after BDNF treatment. Furthermore, the average level of munc18-1 in BDNF over-expressing munc18-1 heterozygous groups (2.93) tend to be even slightly higher than WT controls (2.84) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of BDNF on expression levels of munc18-1 protein in primary cultured neurons. a Representative gels of Western blot analysis from neuronal cultures at 12 DIV (WT and munc18-1+/− cortical neurons; control and BDNF over-expressing groups). b Quantitative analyses of munc18-1 protein expression by densitometry. The expression levels are integrated density values normalized to wild-type control and against GAPDH. Note that the protein levels of munc18-1 increased after BDNF transduction in both WT and munc18-1+/− neurons (statistical significance as ***P < 0.001 by ttest; WT, n = 13; munc18-1+/−, n = 23). Error bars depict S.E.M.

Discussion

BDNF secretion from neurons

In this study, we have used genetically modified mice with impaired munc18-1 expression for the primary cortical neuronal culture and tested chronic effect of BDNF over-expression in wild type (WT) and munc18-1+/− neurons. To our best knowledge, this is the first report to present the role of munc18-1 in the regulation of BDNF secretion. Secretion of BDNF is regulated at multiple levels from transcription/translation to trafficking and controlled secretion from neurites as reviewed (Lessmann and Brigadski 2009; Ovsepian and Dolly 2011). Although it is assumed that synaptotagmins and SNARE complex assembly are driving the exocytosis of BDNF containing vesicles, the exact composition of the SNARE complex and the interacting proteins binding to the complex and regulating its function are not well characterized (Deák 2014; Dean et al. 2009; Ovsepian and Dolly 2011; Shimojo et al. 2015). Our functional study implicates that munc18-1 levels are rate limiting for BDNF secretion. We have found a striking accumulation of BDNF intracellularly if munc18-1 levels are low as it was the case in the munc18-1 heterozygous neurons that contained amounts of BDNF more than triple of that detected in WT cells (Fig. 2a). We assume that the transient upshot in BDNF levels at 7 div in munc18-1+/− cultures may result from release of the accumulated intracellular BDNF in munc18-1+/− neurons as their munc18-1 levels start to rise. The relative importance of munc18-1 is further emphasized by our finding that even under circumstances when BDNF expression is enhanced, munc18-1 will determine the amount of secreted BDNF (Fig. 2b, c).

Synaptic impairment in munc18-1 KO heterozygous neurons

Through the synaptic functional experiments of this study, we showed lowered synaptic release in munc18-1 deficient cultured neurons. Furthermore, we proved functional restoration of synaptic vesicle release by the over-expression of BDNF in munc18-1 deficient neurons. It was shown previously that excitatory synapses lacking munc18-1 are perfectly silent, with no detectable glutamate release (Deák et al. 2009; Verhage et al. 2000). Consequently, this case could hinder BDNF release by diminishing the driving impulse necessary for BDNF secretion. Previous studies mainly focused on the viability of the munc18-1 homozygous KO cultured neurons or on electrophysiological characterization of munc18-1-deficient neurons. Interestingly, it was found that BDNF delayed but could not prevent degeneration of munc-18 KO −/− neurons (Heeroma et al. 2004). Because the stability of cultured neuronal networks depends on synaptic transmission, we focused only on neurons with moderately decreased munc-18 expression. The heterozygous (+/−) neurons were able to differentiate similarly to wild-type cells and formed individual synaptic buttons as described earlier (Toonen et al. 2006) (Orock et al. 2018), and we tested them in our study at 7–18 days in vitro. Morphologically, no remarkable differences were observed between control and munc18-1-deficient group in the aspects of neurite outgrowth and differentiation. Although munc18-1 proteins are indispensable regulators of presynaptic membrane fusion and priming of synaptic vesicles, lack of munc18-1 expression seems not to hinder early stages of brain development and differentiation (Deák et al. 2009; Verhage et al. 2000). The remarkable reduction in the size of the recycling vesicle pool in the munc18-1 +/− synapses closely correlates with the lower level of munc18-1 expression in this model, both at around 65% of control levels (Figs. 1b and 3c).

The relevance of our findings to brain aging is further supported by the recently published phenotype of aging in BDNF-deficient models: Mice heterozygous for BDNF developed abnormal interactions between individual cortical neurons and had accelerated learning impairment during aging (Petzold et al. 2015). Examining cell-autonomous requirements for BDNF in visual cortical layer 2/3 neurons, it was found that the number of functional BDNF alleles a neuron carried determined its density of dendritic spines; the target structures at which most excitatory synapses were formed. This requirement for BDNF existed both during postnatal development and in adulthood (English et al. 2012). Moreover, in old cats, beside marked cellular senescence, both the density and optical absorbance intensity of BDNF- and TrkB-immunoreactive cells in each lateral geniculate nucleus layer were significantly decreased compared with young adult cats (Tong et al. 2015).

Exercise is one of the best studied preventive measures of age-related cognitive decline (Sobol et al. 2015), and its positive effects on frailty and brain function are thought to be the results of increased levels of neurotrophic factors and better perfusion of the brain via angiogenesis (Sonntag et al. 2013; Thomas et al. 2012). Exercise-dependent changes in serum concentration of BDNF were related to an increase in gray matter density in the left hippocampus, the insular cortex, and the left cerebellar lobule in obese patients (Mueller et al. 2015). Indeed, the strongest molecular relationship of exercise and functional connectivity was identified for BDNF, as its allele variant, rs7294919, also showed a pronounced association with hippocampal volume (Foster 2015). Moreover, in the elderly reduced BDNF levels correlated with increased mean diffusivity from diffusion tensor imaging occurring in the left hippocampus along with decreased normalized volume in the left amygdala (Manna et al. 2015). Indeed, sedative lifestyle, major depression, aging, and chronic stress all could lead to dementia and were shown to be associated with lower levels of BDNF (Dwivedi 2013; Pal et al. 2014) (Kennedy et al. 2016). Importantly, polymorphism of BDNF with Val66Met expression is associated with major depression (Czira et al. 2012) and with increased risk of cognitive impairment (Dempster et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2015; Lim et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2016). In turn, low BDNF levels can usher synaptic failure in dementia and may contribute to the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. BDNF levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were significantly reduced in patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease compared with age-matched healthy controls and subjects with mild-cognitive impairment (Forlenza et al. 2015). Amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers and ApoE4, the major risk factor for AD, both reduced BDNF levels via genomic inhibition by histone deacetylation (Sen et al. 2015). Interestingly, the net effect of higher H3K9 methylation in addition to increased H3 and H4 acetylation in 3xTg-AD mice resulted in lower BDNF gene expression (Walker et al. 2013). Lower CSF BDNF levels were proposed to be a useful marker to assess risk of progression from MCI to AD (Forlenza et al. 2015), similarly to lower CSF Aβ42.

BDNF treatment of synaptic dysfunction

The possible therapeutic benefits of neurotrophic administration to alleviate cognitive decline with aging is a recurring subject of debates (Rose 1999). The exact mechanisms of BDNF effects on presynaptic vesicular exocytosis or recycling remained elusive because of the multi-factorial effects of this neurotrophic hormone including an increase in the number of synaptic connections. Our experimental approach made it also possible to see the effects of BDNF directly on presynaptic terminals. We found that BDNF restored the presynaptic function, which had been impaired by munc18-1 haploinsufficiency up to the level in wild-type control neurons. Importantly, these results revealed the functional relationship between BDNF and munc-18 at presynaptic terminals. It must be noted, however, that BDNFstimulated synaptic release even further in wild-type neurons than munc18-1+/− (Fig. 3c, d; note value of ΔF still remained lower in heterozygous cells than in BDNF overexpressing wild-type neurons).

The relevance of our findings to brain aging is further supported by recent papers about the role of BNDF in cognition function. In human studies polymorphism of BDNS at SNP rs6265 but not rs7124442 was associated with severity of depression in elderly men (Czira et al. 2012; Laing et al. 2012). Although no change in transmitter levels have been reported, the applied approach and limited scope of CSF analysis was not suitable for measurement of local cortical transmitter differences. BDNF variants of SNP rs6265 and rs7103411 were associated with lower memory and perceptual speed in women (Laing et al. 2012).

A recently published paper described in details the aging phenotype of BDNF deficient models: Mice heterozygous for BDNF developed abnormal interactions between individual cortical neurons and had accelerated learning impairment during aging (Petzold et al. 2015). Examining cell-autonomous requirements for BDNF in visual cortical layer 2/3 neurons, it was found that the number of functional BDNF alleles a neuron carried determined its density of dendritic spines, the target structures at which most excitatory synapses were formed. This requirement for BDNF existed both during postnatal development and in adulthood (English et al. 2012). Moreover, in old cats, beside marked cellular senescence, both the density and optical absorbance intensity of BDNF- and TrkB-immunoreactive cells in each lateral geniculate nucleus layer were significantly decreased compared with young adult cats (Tong et al. 2015). However a closer investigation is warranted about the role of BDNF in synaptic plasticity and its specific interactions with synaptic vesicular proteins previously reported. For instance, BDNF was indicated to regulate synapsin I–actin interaction by stimulating MAP kinase dependent phosphorylation of synapsin I (Jovanovic et al. 2000). BDNF was also known to mediate rapid enrichment of presynaptic boutons with synaptophysin (Li and Keifer 2012). There is overwhelming evidence that BDNF treatment leads to morphological changes in the synaptic structure (Pozzo-Miller et al. 1999; Tyler and Pozzo-Miller 2001), including an increase in the number of docked vesicles at the presynaptic active zone. Although previous studies also showed that the BDNF increased the levels of synaptophysin and synapsin I in the spinal neurons (Jovanovic et al. 2000) and enhanced synapsin I phosphorylation after BDNF treatment was implicated during post-tetanic potentiation (Valente et al. 2012), detailed characterization of functional consequences on the presynaptic site by BDNF remain elusive. These results seem to correlate BDNF with presynaptic modifications that accompany synaptic regulations and largely consistent with the result of this study showing increased synaptic vesicular recycling pool by BDNF over-expression in wild-type neurons.

In addition, one should consider that munc-18 and its isoforms are implicated in exocytosis beyond the nervous system. Regarding the most prevalent health issue of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, it is currently not known whether reduced munc18-1 levels will change insulin secretion. Exocytosis of insulin from pancreatic β-cells has been shown to utilize similar molecular machinery to control membrane trafficking and vesicle fusion as have primarily been identified and investigated in presynaptic terminals of neurons (Zhang et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2004). The minimal machinery of the SNARE fusion complex is responsible for regulating the secretion of insulin from islet β-cells in response to increased blood glucose, as well as facilitating the downstream action of insulin on peripheral glucose disposal via the insertion of glucose transporter (GLUT4) vesicles into the cell surface membranes of adipocytes and skeletal muscle. During insulin secretion, the process of SNARE complex formation is facilitated by munc18-1 (Leung et al. 2007; Tomas et al. 2008). Munc18-3 has also been shown as a key player in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and in the regulation of insulin secretion. Increased expression of Munc18-3 inhibits the fusion of GLUT4 vesicles by blocking the binding of VAMP2 to syntaxin 4 (Oh et al. 2005; Oh and Thurmond 2009). Impaired insulin response to glucose and greatly reduced expression of islet SNARE complex and SNARE-modulating proteins were demonstrated in patients with type 2 diabetes. The secretory vesicle (v)-SNAREs (VAMP-2), the target (t) membrane-SNAREs (syntaxin-1A and SNAP-25), and the cytosolic SNARE-modulating proteins (munc18–1 and Munc 13–1) were decreased on either or both mRNA and protein levels in these patients (Ostenson et al. 2006).

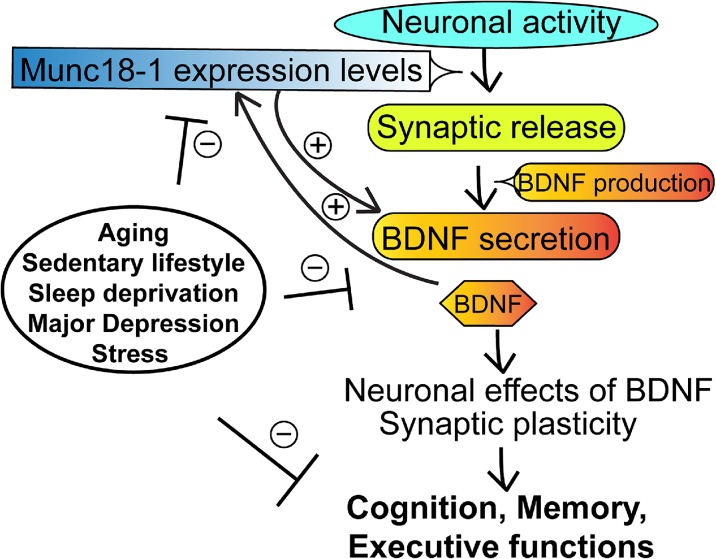

We propose a novel model (Fig. 5) that includes our findings on the positive interaction between munc18-1 and BDNF augmenting synaptic function and its deficiency in the aging brain leading to cognitive impairment. BDNF significantly increased the amount of munc18-1 in both wild-type and munc18-1+/−, and these findings were consistent with the restored synaptic vesicular release. The BDNF induced changes in munc18-1 levels in this study equaled 56% and 69% increases in WT and munc18-1+/− neurons, respectively (Fig. 4). BDNF signaling may stimulate gene transcription (Messaoudi et al. 2002) or protein synthesis (Santos et al. 2010), and BDNF was reported to differentially upregulate the expression of synaptic vesicular associate proteins such as synaptophysin and synaptobrevin (Tartaglia et al. 2001). However, there have been no reports on the upregulated expression of munc18-1 by BDNF at presynaptic terminal, and the result from this study suggests a novel munc18-1 synthesis-dependent form of BDNF modulation of synaptic efficacy. BDNF was also reported to differentially upregulate vesicular glutamate receptors through TrkB receptor activation and by the mechanism sensitive to inhibition of transcription or translation (Melo et al. 2013). Interestingly, BDNF-activated trkB signaling has been reported to induce phosphorylation of munc18-1 on Ser313 in diaphragm muscle by specific isoform of PKC epsilon (Simo et al. 2018). In addition, early BDNF treatment protected neurons and prevented synapse loss in the entorhinal cortex in a mutant amyloid model of Alzheimer’s disease (Nagahara et al. 2013). Overexpressed BDNF did not affect amyloid plaque numbers of APP transgenic mice, indicating that direct amyloid reduction is not necessary to achieve significant neuroprotective benefits by BDNF (Nagahara et al. 2013). Others reported that BDNF significantly reduced amyloid beta levels via induction of SORLA expression and selective activation of the non-amyloidogenic pathway (Rohe et al. 2009). Furthermore, overexpressed BDNF was also shown to be neuroprotective in a Huntington’s disease model (Giralt et al. 2011). Therefore considering the central role of BDNF in learning and memory processes as well as its neuroprotective effects (Deak et al. 2016), BDNF is an excellent therapeutic target to alleviate age-related neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

Fig. 5.

Proposed model of regulatory interactions between BDNF and munc18-1 in neurons. During brain aging according to our model based on the results of this study a vicious cycle is activated: insufficient BDNF is secreted that decreases munc18-1 levels, which, in turn, further hinders BDNF secretion. The process could lead to synaptic failure and neurodegeneration in the aging brain as well as in other harmful circumstances like chronic stress, physical inactivity, and major depression

Conclusions

Taken together, our results are the first evidence demonstrating munc18-1 downstream from BDNF and in direct connection to facilitate synaptic vesicular recycling as part of BDNF potentiating effect on synaptic communication. Results of this study obtained by the synaptic functional assays and measuring munc18-1 expressions allow the following conclusions and a novel model of synaptic failure in the aging brain (Fig. 5). We have found that treatment with BDNF enhances synaptic strength of intact neurons and restores synaptic activity, which is decreased in munc18-1 deficient neuron. Also, expression of munc18-1 is upregulated by BDNF in both intact and munc18-1 deficient neuron, and BDNF function of facilitating neurotransmitter release is related to the role of munc18-1 in presynaptic terminal. Moreover, this is the first report about the direct role of munc18-1 in the regulation of BDNF secretion. Taken together, our results confirm that enhancing BDNF levels in the aging brain might be a candidate approach for therapy of synaptic dysfunction in some neurodegenerative disorders and for prevention of cognitive decline with aging (Deák and Sonntag 2012). Considering the role of BDNF in synaptic plasticity and suggested interactions with neuronal proteins, further studies are clearly justified. Finally, it would be of major significance to test whether other neurotrophic pathways, like insulin or IGF-1 (Deák 2014; Deák and Sonntag 2012; Sonntag et al. 2013) or PACAP (Jozsa et al. 2005; Reglodi et al. 2011), have similar effect in invigorating synaptic connection as seen with BDNF in our present study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following assistants for their skilled help: Nikolett Szarka and Joseph Wood for the neuronal cultures; Asfa Sima, Kushal Thapa and Jennifer Fessler for the mouse husbandry and genotyping.

Author contributions

FD and YIL designed the study. FD and YIL designed the lentiviral constructs used for BDNF expression. YIL prepared the lentiviral vector. AL prepared and purified lentiviral particles for transduction. YIL, YGK, HJP, and AL prepared neuronal cultures. YIL, HJP, SL, and AL performed ELISA assays for BDNF levels. HJP, JCA, KMJ, and AO measured munc18-1 expression with Western blots. YIL, AL, and YGK performed FM imaging experiments. FD and YIL wrote the manuscript.

Funding information

This work was financially supported by the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology, NIH P20GM104934 CoBRE Pilot grant and NIH NIA 3P30AG050911-04S1 Supplement grant as well as the Presbyterian Health Foundation (to FD). We are grateful for the financial support of the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (to A.O., S.L., F.D.); a pilot grant from Oklahoma Center of Neuroscience (to A.O.) and a basic research support grant program (2010-0021928) from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (to YIL).

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care, and the Use Committee strictly follows the guidelines of AALAS and NIH.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Cao P, Maximov A, Sudhof TC. Activity-dependent IGF-1 exocytosis is controlled by the ca(2+)-sensor synaptotagmin-10. Cell. 2011;145:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cory S, Kidane AH, Shirkey NJ, Marshak S. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the development of structural neuronal connectivity. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:271–288. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czira ME, Wersching H, Baune BT, Berger K. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene polymorphisms, neurotransmitter levels, and depressive symptoms in an elderly population. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:1529–1541. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák F. Neuronal vesicular trafficking and release in age-related cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1325–1330. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák F, Sonntag WE. Aging, synaptic dysfunction, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:611–625. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák F, Xu Y, Chang WP, Dulubova I, Khvotchev M, Liu X, Südhof TC, Rizo J. Munc18-1 binding to the neuronal SNARE complex controls synaptic vesicle priming. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:751–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak F, Freeman WM, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Sonntag WE. Recent developments in understanding brain aging: implications for Alzheimer's disease and vascular cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:13–20. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Liu H, Dunning FM, Chang PY, Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin-IV modulates synaptic function and long-term potentiation by regulating BDNF release. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:767–776. doi: 10.1038/nn.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster E, Toulopoulou T, McDonald C, Bramon E, Walshe M, Filbey F, Wickham H, Sham PC, Murray RM, Collier DA. Association between BDNF val66 met genotype and episodic memory American journal of medical genetics part B, neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the international society of. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;134B:73–75. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in late-life depression. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21:433–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English CN, Vigers AJ, Jones KR. Genetic evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates competitive interactions between individual cortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19456–19461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206492109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figurov A, Pozzo-Miller LD, Olafsson P, Wang T, Lu B. Regulation of synaptic responses to high-frequency stimulation and LTP by neurotrophins in the hippocampus. Nature. 1996;381:706–709. doi: 10.1038/381706a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza OV, Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Radanovic M, Talib LL, Rocha NP, Gattaz WF. Lower cerebrospinal fluid concentration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor predicts progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. NeuroMolecular Med. 2015;17:326–332. doi: 10.1007/s12017-015-8361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PP. Role of physical and mental training in brain network configuration. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:117. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt A, Carreton O, Lao-Peregrin C, Martin ED, Alberch J (2011) Conditional BDNF release under pathological conditions improves Huntington's disease pathology by delaying neuronal dysfunction. Mol Neurodegener 6(1): 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1326-6-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hancock SE, Friedrich MG, Mitchell TW, Truscott RJ, Else PL. The phospholipid composition of the human entorhinal cortex remains relatively stable over 80 years of adult aging. GeroScience. 2017;39:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9961-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeroma JH, Roelandse M, Wierda K, van Aerde KI, Toonen RFG, Hensbroek RA, Brussaard A, Matus A, Verhage M. Trophic support delays but does not prevent cell-intrinsic degeneration of neurons deficient for munc18-1. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:623–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Czernik AJ, Fienberg AA, Greengard P, Sihra TS. Synapsins as mediators of BDNF-enhanced neurotransmitter release. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:323–329. doi: 10.1038/73888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozsa R, Hollosy T, Tamas A, Toth G, Lengvari I, Reglodi D. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide plays a role in olfactory memory formation in chicken. Peptides. 2005;26:2344–2350. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Schuman EM. Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science. 1995;267:1658–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.7886457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MJ, Wang C, Derby CA, Lipton RB, Zimmerman ME, Sliwinski MJ, Rabin LA. Subjective cognitive decline prediction of mortality: results from the Einstein aging study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:239–248. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy G, Hardman RJ, Macpherson H, Scholey AB, Pipingas A. How does exercise reduce the rate of age-associated cognitive decline? A review of potential mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;55:1–18. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Kim JW, Pyeon HJ, Hyun JK, Hwang JY, Choi SJ, Lee JY, Deák F, Kim HW, Lee YI. Differential stimulation of neurotrophin release by the biocompatible nano-material (carbon nanotube) in primary cultured neurons. J Biomater Appl. 2013;28:790–797. doi: 10.1177/0885328213481637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen P, Pedersen M, Hänninen T, Bruunsgaard H, Lakka TA, Kivipelto M, Hassinen M, Rauramaa TH, Pedersen BK, Rauramaa R. BDNF is a novel marker of cognitive function in ageing women: the DR's EXTRA study. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing KR, Mitchell D, Wersching H, Czira ME, Berger K, Baune BT. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene: a gender-specific role in cognitive function during normal cognitive aging of the MEMO-study? Age (Dordr) 2012;34:1011–1022. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9275-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Baek JH, Kim YH. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with cognitive impairment in elderly Korean individuals. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13:283–287. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Peng LN, Liang CK, Loh CH, Chen LK. Cognitive frailty predicting all-cause mortality among community-living older adults in Taiwan: a 4-year nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessmann V, Brigadski T. Mechanisms, locations, and kinetics of synaptic BDNF secretion: an update. Neurosci Res. 2009;65:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YM, Kwan EP, Ng B, Kang Y, Gaisano HY. SNAREing voltage-gated K+ and ATP-sensitive K+ channels: tuning beta-cell excitability with syntaxin-1A and other exocytotic proteins. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:653–663. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Keifer J. Rapid enrichment of presynaptic protein in boutons undergoing classical conditioning is mediated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2012;203:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Hassenstab J, Cruchaga C, Goate A, Fagan AM, Benzinger TL, Maruff P, Snyder PJ, Masters CL, Allegri R, Chhatwal J, Farlow MR, Graff-Radford NR, Laske C, Levin J, McDade E, Ringman JM, Rossor M, Salloway S, Schofield PR, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Bateman RJ, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network BDNF Val66Met moderates memory impairment, hippocampal function and tau in preclinical autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2016;139:2766–2777. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PH, Tsai SJ, Huang CW, Mu-En L, Hsu SW, Lee CC, Chen NC, Chang YT, Lan MY, Chang CC (2016) Dose-dependent genotype effects of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on default mode network in early stage Alzheimer's disease. Oncotarget 7(34):54200–54214. 10.18632/oncotarget.11027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Logan S, Owen D, Chen S, Chen WJ, Ungvari Z, Farley J, Csiszar A, Sharpe A, Loos M, Koopmans B, Richardson A, Sonntag WE. Simultaneous assessment of cognitive function, circadian rhythm, and spontaneous activity in aging mice. GeroScience. 2018;40:123–137. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna A, Piras F, Caltagirone C, Bossu P, Sensi SL, Spalletta G. Left hippocampus-amygdala complex macro- and microstructural variation is associated with BDNF plasma levels in healthy elderly individuals. Brain Behav. 2015;5:e00334. doi: 10.1002/brb3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo CV, Mele M, Curcio M, Comprido D, Silva CG, Duarte CB. BDNF regulates the expression and distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters in cultured hippocampal neurons. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi E, Ying SW, Kanhema T, Croll SD, Bramham CR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor triggers transcription-dependent, late phase long-term potentiation in vivo. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7453–7461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07453.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minichiello L. TrkB signalling pathways in LTP and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:850–860. doi: 10.1038/nrn2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K, Möller HE, Horstmann A, Busse F, Lepsien J, Blüher M, Stumvoll M, Villringer A, Pleger B. Physical exercise in overweight to obese individuals induces metabolic- and neurotrophic-related structural brain plasticity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:372. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Mateling M, Kovacs I, Wang L, Eggert S, Rockenstein E, Koo EH, Masliah E, Tuszynski MH. Early BDNF treatment ameliorates cell loss in the entorhinal cortex of APP transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15596–15602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5195-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Thurmond DC. Munc18c depletion selectively impairs the sustained phase of insulin release. Diabetes. 2009;58:1165–1174. doi: 10.2337/db08-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Spurlin BA, Pessin JE, Thurmond DC. Munc18c heterozygous knockout mice display increased susceptibility for severe glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2005;54:638–647. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orock A, Logan S, Deak F. Munc18-1 haploinsufficiency impairs learning and memory by reduced synaptic vesicular release in a model of Ohtahara syndrome. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2018;88:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostenson CG, Gaisano H, Sheu L, Tibell A, Bartfai T. Impaired gene and protein expression of exocytotic soluble N-ethylmaleimide attachment protein receptor complex proteins in pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2006;55:435–440. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db04-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovsepian SV, Dolly JO. Dendritic SNAREs add a new twist to the old neuron theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19113–19120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017235108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Singh SN, Chatterjee A, Saha M. Age-related changes in cardiovascular system, autonomic functions, and levels of BDNF of healthy active males: role of yogic practice. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:9683. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9683-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold A, Psotta L, Brigadski T, Endres T, Lessmann V. Chronic BDNF deficiency leads to an age-dependent impairment in spatial learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2015;120:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo MM. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzo-Miller LD, Gottschalk W, Zhang L, McDermott K, du J, Gopalakrishnan R, Oho C, Sheng ZH, Lu B. Impairments in high-frequency transmission, synaptic vesicle docking, and synaptic protein distribution in the hippocampus of BDNF knockout mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4972–4983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04972.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reglodi D, Kiss P, Lubics A, Tamas A. Review on the protective effects of PACAP in models of neurodegenerative diseases in vitro and in vivo. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:962–972. doi: 10.2174/138161211795589355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AA, Abraham CR, Rosene DL. Candidate molecular pathways of white matter vulnerability in the brain of normal aging rhesus monkeys. GeroScience. 2018;40:31–47. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohe M, Synowitz M, Glass R, Paul SM, Nykjaer A, Willnow TE. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces amyloidogenic processing through control of SORLA gene expression. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15472–15478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3960-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GM. Behavioral effects of neurotrophic factor supplementation in aging. Age (Omaha) 1999;22:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11357-999-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AR, Comprido D, Duarte CB. Regulation of local translation at the synapse by BDNF. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. ApoE4 and Abeta oligomers reduce BDNF expression via HDAC nuclear translocation. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7538–7551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0260-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK, Rao MS, Hattiangady B, Zaman V, Shetty GA. Hippocampal neurotrophin levels after injury: relationship to the age of the hippocampus at the time of injury. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:520–532. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty GA, Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. Neural stem cell- and neurogenesis-related gene expression profiles in the young and aged dentate gyrus. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:2165–2176. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojo M, Courchet J, Pieraut S, Torabi-Rander N, Sando R, 3rd, Polleux F, Maximov A. SNAREs controlling vesicular release of BDNF and development of callosal axons. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shobin E, Bowley MP, Estrada LI, Heyworth NC, Orczykowski ME, Eldridge SA, Calderazzo SM, Mortazavi F, Moore TL, Rosene DL. Microglia activation and phagocytosis: relationship with aging and cognitive impairment in the rhesus monkey. GeroScience. 2017;39:199–220. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9965-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra F, Kohanski R. Geroscience and the trans-NIH geroscience interest group. GSIG GeroSci. 2017;39:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11357-016-9954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simo A, et al. BDNF-TrkB signaling coupled to nPKCepsilon and cPKCbetaI modulate the phosphorylation of the exocytotic protein Munc18-1 during synaptic activity at the neuromuscular junction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:207. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobol NA, Hoffmann K, Vogel A, Lolk A, Gottrup H, Høgh P, Hasselbalch SG, Beyer N. Associations between physical function, dual-task performance and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment Health. 2015;20:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1063108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag WE, Deak F, Ashpole N, Toth P, Csiszar A, Freeman W, Ungvari Z. Insulin-like growth factor-1 in CNS and cerebrovascular aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:27. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia N, Du J, Tyler WJ, Neale E, Pozzo-Miller L, Lu B. Protein synthesis-dependent and -independent regulation of hippocampal synapses by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37585–37593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AG, Dennis A, Bandettini PA, Johansen-Berg H. The effects of aerobic activity on brain structure. Front Psychol. 2012;3:86. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas A, Meda P, Regazzi R, Pessin JE, Halban PA. Munc 18-1 and granuphilin collaborate during insulin granule exocytosis. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 2008;9:813–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong CW, Wang ZL, Li P, Zhu H, Chen CY, Hua TM. Effects of senescence on the expression of BDNF and TrkB receptor in the lateral geniculate nucleus of cats. Dongwuxue Yanjiu. 2015;36:48–53. doi: 10.13918/j.issn.2095-8137.2015.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen RF, Kochubey O, de Wit H, Gulyas-Kovacs A, Konijnenburg B, Sørensen JB, Klingauf J, Verhage M. Dissecting docking and tethering of secretory vesicles at the target membrane. EMBO J. 2006;25:3725–3737. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucsek Z, Noa Valcarcel-Ares M, Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Fülöp G, Gautam T, Orock A, Csiszar A, Deak F, Ungvari Z. Hypertension-induced synapse loss and impairment in synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus mimics the aging phenotype: implications for the pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment. GeroScience. 2017;39:385–406. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9981-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WJ, Pozzo-Miller LD. BDNF enhances quantal neurotransmitter release and increases the number of docked vesicles at the active zones of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4249–4258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04249.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A, Tarantini S, Toth P, Kirkpatrick AC, Csiszar A, Prodan CI. Repeated valsalva maneuvers promote symptomatic manifestations of cerebral microhemorrhages: implications for the pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment in older adults. GeroScience. 2018;40:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente P, Casagrande S, Nieus T, Verstegen AM, Valtorta F, Benfenati F, Baldelli P. Site-specific synapsin I phosphorylation participates in the expression of post-tetanic potentiation and its enhancement by BDNF. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5868–5879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5275-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage M et al (2000) Synaptic assembly of the brain in the absence of neurotransmitter secretion, vol 287, science (New York, NY), pp 864–869 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walker MP, LaFerla FM, Oddo SS, Brewer GJ. Reversible epigenetic histone modifications and Bdnf expression in neurons with aging and from a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Khan A, Ostenson CG, Berggren PO, Efendic S, Meister B. Down-regulated expression of exocytotic proteins in pancreatic islets of diabetic GK rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:1038–1044. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Lilja L, Bark C, Berggren PO, Meister B. Mint1, a Munc-18-interacting protein, is expressed in insulin-secreting beta-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]