Abstract

The present study investigated the effects of pecking stones on feeding behaviour of hens from 16 to 46 weeks of age. Eighteen flocks of Hy-Line Brown hens were housed in 2 commercial free-range housing systems. Farm A housed 10 flocks of beak trimmed (infrared beak treatment) hens in fixed sheds. Farm B housed 8 flocks of hens with intact beaks in mobile sheds. On each farm, flocks were equally assigned to control groups (no access to pecking stones) and treatment groups (access to pecking stones). Data were evaluated every 10 weeks. At each time point, 10 hens per flock were housed in individual pens, and each hen was provided with 250 g of mash diet and ad libitum water for 24 h. After 24 h, feed samples were collected and used to determine 24-h feed intake. Nutrient and particle selection was measured by subtracting nutrients and particles present in the leftover feed from the vaules obtained in the offered feed and expressed the change (Δ). In addition, pecking stone consumption was recorded for each flock. Data were analysed separately for each farm using fixed effects of pecking stone availability and hen age. Spearman's rho correlation coefficients and linear regression models were constructed to evaluate the relationship of beak length and pecking stone usage, discrete mean particle size (dMEAN) consumption (Δ dMEAN), and Δ nutrient intake. Hens with access to pecking stones consumed significantly lower quantities of large feed particles (>2.8 mm) on farm A (P = 0.029) and selected significantly more fine particles, on farm B (P = 0.013). Overall, positive relationships (P = 0.001) between beak length and pecking stone consumption, Δ dMEAN, and Δ phosphorus consumption were observed. In conclusion, pecking stone consumption resulted in reduced selection and consumption of feed particles in hens housed on both farms. Further research is warranted to investigate the effect of pecking stones on sensory innervation of the beak.

Keywords: Poultry, Welfare, Feeding behaviour, Nutrition, Environmental enrichment

1. Introduction

Beak trimming has been used as a remedy to control severe feather pecking for decades (Dennis et al., 2009). However, due to the potential development of neuromas and the resulting chronic pain, beak trimming has been banned in several countries including Switzerland, Sweden, Germany, Norway and Finland (Gilani et al., 2013, Petek and McKinstry, 2010). In addition, non-beak-trimming strategies coupled with other management approaches, such as rearing pullets in matching housing systems and with reduced light intensity have been of limited success to control severe feather pecking (Angevaare et al., 2012, Gentle et al., 1997, Glatz, 2001, Marchant-Forde and Cheng, 2010).

Environment enrichment is an alternative method to prevent unwanted behaviours in hens (Jones, 2001, Jones et al., 2002). For example, the use of pecking stones has been implemented by many European countries. Pecking stones that have an abrasive surface may result in blunted beaks. Although in a previous report by Glatz and Runge (2017), pecking stone results not in blunting but reduced sharpness of the tip of the beak. This eroding of the beak tip may influence the hens' pecking of feed particle efficiency and as a result modify the feeding behaviour. This modification in feeding behaviour may result in lower consumption of large particles and thus effecting nutrient intake. However, limited research is available about the impact of pecking stones on feeding behaviour and beak length in free range laying hens.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of pecking stone consumption on feed intake, feed particle selection, and nutrient intake in 2 different free-range housing systems. Furthermore, the purpose of this study was to examine the impact of beak length on pecking stone consumption, feed intake, feed particle selection, and nutrient intake.

2. Materials and methods

The experiment was reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (AEC15-008) at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. A total of 18 flocks of hens from 16 to 46 weeks of age were examined in this study. Hy-Line Brown hens were obtained from the same hatchery (Specialised Breeders Australia, East Maitland, NSW, Australia) and housed at 2 different farms (farm A: 10 flocks, farm B: 8 flocks) located in Victoria, Australia.

2.1. Housing

Hens were housed in 2 commercial housing systems, which differed in several aspects, and fed a commercial layer diet offered in mash form. Farm A housed beak trimmed (infrared beak treatment) hens in fixed sheds. The dimensions of the fixed shed were 130 m × 16 m with an indoor flock density of 9 hens/m2. Perches were present up to 1.2 m above the ground. Slats were used to cover the floor inside the shed. Feed was provided by feeder chains running lengthwise through the shed, nipple drinkers provided water ad libitum. Ten pop holes were present along each side of the shed, and the dimensions of each pop hole were 2 m × 0.45 m. The range area held the current industry standard of 1,500 hens/ha. An automatic egg collection system was used to collect eggs from centrally located nest boxes. During the experimental period, daily egg collection started at 09:00 and ended at 16:00. The lighting program was maintained according to the Hy-Line breeder recommendations (Brown, 2016) and included a combination of artificial and natural light.

Farm B housed hens with intact beaks in mobile sheds. The dimensions of the mobile shed were 21 m × 12 m with an indoor stocking density of 7.9 hens/m2. Perches were present inside the house at a height of 0.60 m above the slats. Feed and water were provided ad libitum in automatic feeder pans and nipple drinkers. Three pop holes with dimensions of 1.22 m × 2.5 m were present on both sides of the house. A ranging area of 75 m × 45 m was provided daily, and mobile sheds were moved weekly to fresh pasture. Automatic egg collection started 09:00 completing 15:00 each day. The lighting program was maintained according to the Hy-Line breeder recommendation and included a combination of artificial and natural light (Brown, 2016).

2.2. Hens and experimental design

The study was conducted to investigate the impact of pecking stone consumption and hen age on beak length, feed intake, particle selection, and nutrient selection. On both farms, pullet flocks were equally divided into layer control groups (no access to pecking stones) and treatment groups (with access to pecking stones). At 16 weeks of age, one stone (approximately 10 kg) per 1,000 hens was introduced to each of the treatment flocks. Hens on farm A with 20,000 hens/flock were given 20 pecking stones, while hens on farm B with 2,000 hens/flock were given 2 pecking stones. Pecking stones were of cylindrical shape with a 30 cm circumference (Fig. 1A). Every 10 weeks, an additional pecking stone per 1,000 hens was added, regardless of the amount consumed of the previously placed pecking stones (Fig. 1B). The composition of pecking stones is provided in Table 1. Hens were reared together before they were placed in separate laying houses (control layer shed or treatment layer shed) at 16 weeks of age in order to avoid variation in the hens' behaviour based on early life experiences.

Fig. 1.

Pecking stones inside the housing facilities of a treatment flock (A) 2 days and (B) 10 weeks after being placed.

Table 1.

Pecking stone composition (%).1

| Nutrients | Content |

|---|---|

| HCl-insoluble ash | 3.30 |

| Calcium | 21.00 |

| Phosphorus | 4.50 |

| Sodium | 6.0 |

| Copper (cupric-sulphate pentahydrate) | 0.009 |

| Magnesium | 0.025 |

| Manganese (manganous oxide) | 0.048 |

| Zinc (zinc oxide) | 0.060 |

| Iodine (Ca-iodate anhydrous) | 0.0012 |

| Selenium (sodium selenite) | 0.0005 |

Pecking stones were of cylindrical shape with 30 cm diameter and obtained from Deutsche Vilomix Tierernährung GmbH, Neuenkirchen- Vörden, Germany.

2.3. Data collection

2.3.1. Individual feed intake, feed particle size, and nutrient selection

A cage consisting of 10 individual holding pens was used to monitor individual hen feed intake and feed selection. The cage was placed in the middle of the poultry house before flock placement to minimise stress associated with placement of novel equipment (Fig. 2). At each time point (starting when hens were 16 weeks of age and continuing at 26, 36 and 46 weeks of age), 10 hens were randomly selected from the control and treatment groups and placed individually in the holding pen of a cage with 250 g of mash feed per hen with water ad libitum. The feed was collected directly from the feed hopper prevent demixing. In addition, 3 feed samples were collected for subsequent analysis of feed particles and nutrient content. Nutritional composition of offered diet at each farm on all time points are presented in Table 2. Each hen was weighed (Mini crane scale, Model OCS_L, Anyload Llc, New Jersey, USA) and the beak length was measured (Vernier calipers, Supatool, Kincrome Australia Pty Ltd, Scoresby, VIC, Australia) before placing the hens in individual holding pens within the cage. Beak length measurement was taken from the outer tip of nostril to the tip of the beak (Glatz and Runge, 2017). After 24 h, hens were re-weighed. The leftover feed was collected from individual hens and weighed to calculate the 24-h feed intake. These collected leftover feed samples were used to determine the particle size selection and nutrient selection.

Fig. 2.

(A) Hens being placed in the cage unit for evaluation of individual feed intake and feeding behaviour; (B) individual hens were confined for 24 h in individual holding pens with 250 g mesh feed and ad libitum water.

Table 2.

Analysed nutrient composition (g/100 g) of feed offered to free-range laying hens at different age periods.1

| Item | Age,weeks | CP | Al | Ca | Cu | Fe | K | Mg | Mn | Na | P | S | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm A | 16 | 17.7 | 1.09 | 0.34 | 9.45 | 295 | 0.72 | 0.021 | 1.61 | 0.17 | 0.063 | 0.026 | 8.14 |

| 26 | 22.7 | 1.61 | 0.29 | 10.38 | 342 | 0.74 | 0.021 | 1.64 | 0.18 | 0.065 | 0.027 | 11.1 | |

| 36 | 20.9 | 1.32 | 0.34 | 14.1 | 285 | 0.82 | 0.021 | 1.61 | 0.19 | 0.067 | 0.028 | 9.70 | |

| 46 | 19.0 | 1.61 | 0.35 | 13.7 | 319 | 0.81 | 0.023 | 1.90 | 0.22 | 0.066 | 0.030 | 1.40 | |

| Farm B | 16 | 17.0 | 1.47 | 0.38 | 13.1 | 195 | 0.55 | 0.017 | 1.38 | 0.14 | 0.068 | 0.024 | 8.97 |

| 26 | 17.5 | 1.56 | 0.36 | 10.7 | 208 | 0.58 | 0.017 | 1.46 | 0.15 | 0.072 | 0.026 | 9.31 | |

| 36 | 17.8 | 1.73 | 0.36 | 11.5 | 214 | 0.61 | 0.018 | 1.19 | 0.15 | 0.069 | 0.026 | 8.68 | |

| 46 | 20.0 | 2.04 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 226 | 0.61 | 0.019 | 1.04 | 0.14 | 0.066 | 0.025 | 9.00 |

Means of analysed values of 3 feed samples per time point per flocks.

The collected feed samples directly from the feed hopper from each flock house at each time point (triplicate 500 g each) and the collected leftover feed from 10 hens after a 24-h period were pooled separately into 2 equal sample groups for analysis while average values were used for statistical analysis in order to determine feed particles and nutrients selection. One sub-sample was used to investigate particle size distribution. This was performed using a mechanical shaker (Retsch AS 200 digit cA, Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany) operated at an amplitude of 3.0 mm for the duration of 5 min. The samples were sieved using sieving pans with mesh diameters of 4.40, 2.8, 2.0, 1.6, 1.25, 1 mm, 500 and 250 μm (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany). Particles were classified as large (>2.8 mm), medium (1.0 to 2.8 mm) or small (<1.0 mm), and mean particle size was calculated as the discrete mean particle size (dMEAN) (Ruhnke et al., 2015, Wolf et al., 2012) following the method as described by Herrera et al. (2016). The second set of pooled samples was passed through a 0.50 mm mesh size grinder and was used for protein determination based on nitrogen estimation using Leco TrueSpec series based on the Dumas combustion method (TruSpec Series Carbon and Nitrogen Analyser, LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, USA) as indicated by AOAC International (2005). Mineral contents were determined using the Ultrawave microwave digestion technique (Milestone UltraWave, Sorisole, Italy). Digestion and absorption were completed using Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICPOES, Agilent Australia, Mulgrave, Australia). The analysed results (e.g., particle size, protein content, and mineral content) of the leftover feed (post 24 h) and collected feed samples (collected from hopper) were used to calculate the nutrient selection and consumption of nutrient following the equation: , where a positive value of indicates less nutrient present in leftover feed compared with offered in feed, indicating more consumption, while a negative value of indicates more nutrients present in leftover feed compared with offered in feed indicating lower consumption of nutrients.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 2.2 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Mean values (average of 10 values) of flock/time point were used for statistical analysis. The flock was defined as an experimental unit. The data obtained at each farm were analysed separately in order to investigate the effects of pecking stone at each farm. Hen age (time points) was treated as a repeated factor. Each response parameter was analysed using a general linear mixed model (GLMM). The model used for analysing data collected from each farm included the fixed effects of pecking stone, age, and the interaction of pecking stone and age.

Spearman's rho correlation coefficients and linear regression models were utilised in order to evaluate the impact of beak length on feed intake, pecking stone consumption, particle size selection, crude protein, and mineral consumption. Independent variables pecking stones, dMEAN, crude protein (CP), sodium (Na), and phosphorus (P) were included in the analysis as they correlated with beak length (P ≤ 0.10). All possible models were run, and the final model included the variables that resulted in the best fit, determined by adjusted r comparisons and P-values indicating significant change in F statistic from a forward stepwise regression analysis. A variable was removed from the model if it was strongly correlated with another (r ≥ 0.70). The most parsimonious models were reported with statistically useful variables in the model.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of pecking stone consumption and hen age on feed intake, particle and nutrient selection

3.1.1. Infrared beak trimmed hens housed in fixed sheds on farm A

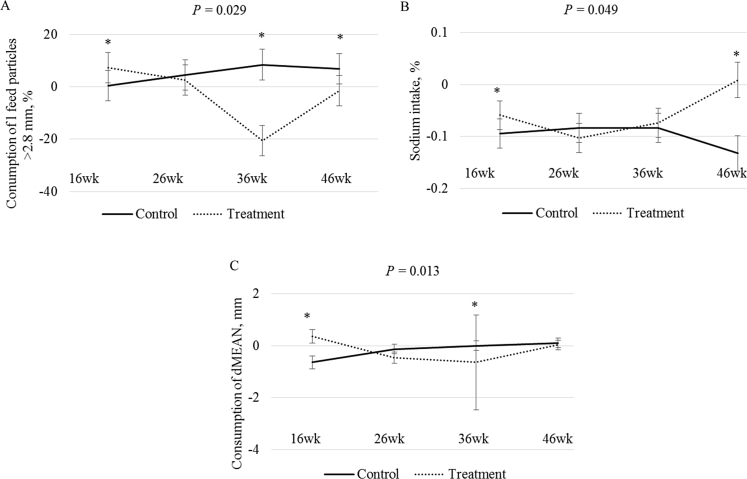

The effect of pecking stones and hen age on beak length, feed intake, particle selection, and nutrient consumption of hens housed on farm A is shown in Table 3. A linear increase in beak length with age (P = 0.001) was observed with beak length being the shortest at the age of 16 weeks, and the longest at the age of 46 weeks. The lowest feed intake (P = 0.004) was observed at the age of 16 weeks, and the highest was observed at the age of 26 weeks. A significant effect (P = 0.001) of age was observed on the consumption of aluminium (Al) in hens housed on farm A (Table 4). Aluminium intake was the highest at the age of 46 weeks, whilst the lowest intake was observed at the age of 36 weeks. A significant interaction between hen age and pecking stone availability (P = 0.029) was observed on large particle (>2.8 mm) selection. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, large particle consumption in control hens increased with age, however, hens offered pecking stones (treatment hens) showed decreased selection of large feed particles from 16 to 36 weeks of age. A significant interaction of pecking stone and time point (P = 0.049) was observed for sodium (Na) consumption. As illustrated in Fig. 3B, Na consumption increased in hens given access to pecking stones with age, whilst a significant decrease in control hens with age was observed.

Table 3.

Effect of pecking stone availability over time on beak length, feed intake, particle size and nutrient selection in free-range laying hens housed on 2 different type farms.1

| Item | Pecking stone consumption2, kg/1,000 hens | Beak length, mm | Daily feed intake, g/hen | Δ dMEAN, mm | Δ Small, <1.0 mm | Δ Medium, 1.0 to 2.8 mm | Δ Large, >2.8 mm | Δ CP, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm A | |||||||||

| Pecking stone (TR) | No (control) | nd | 13.7 ± 0.15 | 104 ± 3.62 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | −3.59 ± 2.02 | 3.48 ± 3.73 | 5.05 ± 2.08 | −1.12 ± 1.07 |

| Yes (treatment) | nd | 13.6 ± 0.17 | 105 ± 5.54 | 0.02 ± 0.16 | −5.00 ± 2.45 | 0.18 ± 3.36 | −3.00 ± 4.03 | −0.62 ± 1.61 | |

| Age3 (A) | 16 weeks | 0.00a | 13.1 ± 0.21b | 85.7 ± 5.42a | 0.15 ± 0.03 | −2.89 ± 2.00 | −0.98 ± 3.20 | 3.87 ± 1.91 | −1.28 ± 1.81 |

| 26 weeks | 2.73 ± 0.35b | 13.4 ± 0.18bc | 116 ± 8.29b | 0.13 ± 0.30 | −6.66 ± 3.27 | 2.94 ± 2.25 | 3.53 ± 1.30 | −2.91 ± 0.69 | |

| 36 weeks | 6.74 ± 0.34c | 13.9 ± 0.19ac | 106 ± 3.97ab | 0.12 ± 0.24 | −4.38 ± 2.63 | −5.23 ± 5.51 | −6.02 ± 8.50 | 1.71 ± 3.16 | |

| 46 weeks | 12.1 ± 0.71d | 14.2 ± 0.12a | 111 ± 3.46b | 0.15 ± 0.32 | −3.24 ± 4.52 | 10.6 ± 6.86 | 2.71 ± 3.04 | −1.00 ± 0.92 | |

| P-value | TR | nd | 0.909 | 0.891 | 0.337 | 0.166 | 0.562 | 0.047 | 0.803 |

| A | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 1.000 | 0.841 | 0.139 | 0.311 | 0.437 | |

| TR × A | nd | 0.238 | 0.483 | 0.846 | 0.526 | 0.918 | 0.029 | 0.676 | |

| Farm B | |||||||||

| Pecking stone | No (control) | nd | 15.9 ± 0.52 | 116 ± 3.45 | −0.17 ± 0.10 | −3.45 ± 2.59 | 2.09 ± 1.42 | 1.39 ± 2.16 | 2.25 ± 3.70 |

| Yes (treatment) | nd | 15.6 ± 0.51 | 112 ± 4.16 | −0.18 ± 0.14 | −7.65 ± 2.69 | 3.00 ± 1.48 | 4.62 ± 2.23 | 3.12 ± 3.73 | |

| Age3 | 16 weeks | 0.00a | 15.6 ± 0.11ab | 95.5 ± 4.21b | −0.14 ± 0.30 | −10.2 ± 5.29 | 3.52 ± 3.51 | 8.35 ± 3.69 | 7.93 ± 4.40 |

| 26 weeks | 9.93 ± 1.28b | 15.2 ± 0.71b | 120 ± 3.66a | −0.29 ± 0.21 | −1.77 ± 3.79 | 2.71 ± 2.70 | −1.77 ± 2.61 | 0.29 ± 3.38 | |

| 36 weeks | 18.7 ± 3.10c | 15.9 ± 0.82a | 124 ± 2.33a | −0.32 ± 0.15 | −3.24 ± 4.07 | 2.82 ± 2.82 | 3.57 ± 2.82 | 3.56 ± 3.52 | |

| 46 weeks | 27.5 ± 4.90d | 16.5 ± 0.59a | 118 ± 5.47a | 0.07 ± 0.06 | −6.99 ± 3.79 | 2.70 ± 2.70 | 1.88 ± 2.61 | −0.47 ± 3.38 | |

| P-value | TR | nd | 0.819 | 0.576 | 0.927 | 0.284 | 0.667 | 0.324 | 0.873 |

| A | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.188 | 0.578 | 0.722 | 0.171 | 0.171 | |

| TR × A | nd | 0.997 | 0.278 | 0.013 | 0.553 | 0.461 | 0.634 | 0.087 | |

dMEAN = discrete mean particle size; Δ = Offered in control feed sample collected from the hopper minus the value present in the leftover feed; nd = not determined.

a, b, c Within a column, means without a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

In each flock, 10 birds were randomly selected at 5 different places of house every 10 weeks. Data were reported as means ± SEM.

After every 10 week, 10 kg pecking stones per 1,000 hens were placed in all treatment flocks.

A total of 5 control and 5 treatment flocks in fixed sheds and 4 control and 4 treatment flocks in mobile sheds were investigated.

Table 4.

Effect of pecking stone availability over time on mineral consumption (%) in free-range laying hens housed on2 different type farms.1

| Item | Δ Al | Δ Ca | Δ Cu | Δ Fe | Δ K | Δ Mg | Δ Mn | Δ Na | Δ P | Δ S | Δ Zn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm A | ||||||||||||

| Pecking stone (TR) | No (control) | −0.006 | −0.15 | 0.001 | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.098 | −0.012 | 0.110 | −0.006 |

| Yes (treatment) | −0.006 | −0.07 | 0.001 | −0.009 | −0.007 | −0.002 | −0.004 | −0.057 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | |

| Age2 (A) | 16 weeks | −0.005a | −0.05 | 0.001 | −0.009 | −0.007 | 0.0001 | −0.002 | −0.077 | −0.002 | −0.005 | −0.006 |

| 26 weeks | −0.008a | −0.14 | 0.001 | −0.015 | −0.020 | −0.006 | −0.004 | −0.093 | −0.002 | −0.005 | −0.003 | |

| 36 weeks | −0.001a | −0.07 | 0.001 | −0.003 | −0.012 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.078 | −0.011 | −0.005 | −0.004 | |

| 46 weeks | −0.010b | −0.19 | 0.001 | −0.009 | −0.003 | 0.0001 | −0.006 | −0.061 | −0.000 | 0.229 | −0.003 | |

| SEM | 0.003 | 0.051 | 0.0001 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.0040 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.079 | 0.001 | |

| P-value | TR | 0.856 | 0.177 | 0.928 | 0.981 | 0.400 | 0.906 | 0.947 | 0.010 | 0.241 | 0.149 | 0.053 |

| A | 0.032 | 0.314 | 0.277 | 0.562 | 0.633 | 0.338 | 0.578 | 0.703 | 0.126 | 0.121 | 0.494 | |

| TR × A | 0.221 | 0.494 | 0.057 | 0.603 | 0.603 | 0.580 | 0.684 | 0.049 | 0.660 | 0.135 | 0.780 | |

| Farm B | ||||||||||||

| Pecking stone | No (control) | −0.010 | −0.159 | 0.001 | −0.011 | −0.007 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.036 | −0.012 | −0.003 | −0.004 |

| Yes (treatment) | −0.005 | −0.131 | 0.001 | −0.008 | −0.007 | −0.002 | −0.003 | −0.060 | −0.002 | −0.004 | −0.003 | |

| A | 16 weeks | −0.006 | −0.119 | 0.001 | −0.007 | −0.009 | −0.002ab | −0.004 | −0.049 | 0.014 | −0.004 | −0.002 |

| 26 weeks | −0.005 | −0.114 | 0.001 | −0.004 | −0.000 | −0.001b | −0.002 | −0.030 | −0.010 | −0.001 | −0.002 | |

| 36 weeks | −0.004 | −0.110 | 0.001 | −0.007 | 0.001 | 0.003ab | −0.004 | −0.051 | −0.008 | −0.004 | −0.005 | |

| 46 weeks | −0.017 | −0.237 | 0.000 | −0.020 | −0.019 | −0.011a | −0.006 | −0.061 | −0.024 | −0.005 | −0.007 | |

| SEM | 0.004 | 0.065 | 0.0001 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.002 | |

| P-value | TR | 0.162 | 0.612 | 0.289 | 0.528 | 0.986 | 0.589 | 0.479 | 0.245 | 0.289 | 0.716 | 0.523 |

| A | 0.096 | 0.462 | 0.496 | 0.096 | 0.094 | 0.017 | 0.126 | 0.821 | 0.057 | 0.766 | 0.113 | |

| TR × A | 0.984 | 0.351 | 0.877 | 0.823 | 0.973 | 0.893 | 0.959 | 0.474 | 0.313 | 0.762 | 0.680 | |

Δ = Offered in control feed sample collected from the hopper minus the value present in the leftover feed.

a, b Within a column, means without a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

In each flock, 10 birds were randomly selected at 5 different places of house every 10 weeks. Results are reported as mean values.

A total of 5 control and 5 treatment flocks in fixed sheds and 4 control and 4 treatment flocks in mobile sheds were investigated.

Fig. 3.

Hens offered pecking stones (treatment) compared with control hens on farms A and B showed various selection of (A) large feed particles (>2.8 mm), (B) sodium consumption, and (C) discrete mean particle size (dMEAN). * indicates that recorded values differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.1.2. Non-beak trimmed hens housed in mobile sheds on farm B

The effect of pecking stones and hen age on beak length, feed intake, particle selection, and nutrient consumption of hens housed on farm B is shown in Table 3. Hen beak length showed a significant decline at 26 weeks of age compared with 16 weeks of age, followed by an increase in length at 36 weeks of age, and an increase at 46 weeks of age. Feed intake (P = 0.012) was the lowest at 16 weeks of age, and the highest at 36 weeks of age. A significant effect of hen age (P = 0.017) was observed on Mg consumption (Table 4). Magnesium consumption was variable with age and the highest consumption was observed at 36 weeks of age, whilst the lowest was observed at 16 weeks of age (Table 4). A significant interaction of pecking stone and age (P = 0.013) was observed on the consumption of dMEAN (mm) feed particle size. As illustrated in Fig. 3C, a significant and steady increase was observed in dMEAN consumption by hens in the control group, whilst a rapid decrease in dMEAN consumption was observed in the treatment hens offered pecking stone from 16 to 36 weeks of age and thereafter, an increase was observed.

3.2. Correlation of beak length with pecking stone usage, feed intake, particle size selection, and nutrient selection

Beak length was positively correlated with pecking stone consumption (r = 0.712, P < 0.001), CP consumption (r = 0.310, P = 0.011), Na consumption (r = 0.260, P = 0.032), and P consumption (r = 0.364, P = 0.002). Beak length accounted for 71.2% of the variation observed in pecking stone consumption, 31.0% in CP consumption, 26.0% in Na consumption and 36.4% in P consumption (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of beak length and pecking stone consumption, feed intake, particle size, and nutrient selection.

| Item | Spearmen correlation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | r | P-value | |

| Pecking stone consumption in 10 weeks, kg/hen | 27 | 0.712 | <0.001 |

| Daily feed intake, g/hen | 67 | 0.110 | 0.374 |

| Δ1 dMEAN, mm | 67 | −0.224 | 0.069 |

| Δ2 <1.0, mm | 67 | 0.082 | 0.508 |

| Δ2 1.0 to 2.8, mm | 67 | 0.008 | 0.950 |

| Δ2 >2.8, mm | 67 | 0.012 | 0.950 |

| Δ2 CP, g/100 g | 67 | 0.310 | 0.011 |

| Δ2 Aluminium, g/100 g | 62 | −0.184 | 0.153 |

| Δ2 Calcium, g/100 g | 67 | −0.077 | 0.538 |

| Δ2 Copper, g/100 g | 68 | 0.180 | 0.142 |

| Δ2 Ferrum, g/100 g | 68 | −0.010 | 0.933 |

| Δ2 Potassium, g/100 g | 68 | 0.127 | 0.300 |

| Δ2 Magnesium, g/100 g | 68 | 0.075 | 0.541 |

| Δ2 Manganese, g/100 g | 68 | 0.047 | 0.702 |

| Δ2 Sodium, g/100 g | 68 | 0.260 | 0.032 |

| Δ2 Phosphorus, g/100 g | 68 | 0.364 | 0.002 |

| Δ2 Sulphur, g/100 g | 68 | 0.188 | 0.125 |

| Δ2 Zinc, g/100 g | 67 | 0.185 | 0.133 |

dMEAN = discrete mean particle size.

Δ dMEAN = dMEAN offered in feed subtracted from dMEAN in leftover feed.

Δ = Nutrient determined in the control sample collected from the hopper minus nutrient present in leftover feed

The most parsimonious regression models (P < 0.001) were indicated by an interaction between beak length and pecking stone consumption, dMEAN, CP consumption, P, and Na consumption. The strongest relationship was observed between pecking stone consumption and beak length (r = 0.815, P < 0.001), beak length and dMEAN (r = −0.319, P = 0.159), and beak length and Na consumption (r = 0.147, P = 0.526) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multiple regression analysis on the pecking stone consumption, Δ discrete mean particle size (dMEAN) consumption, nutrients selection, and beak length.

| Item | Estimates of linear regression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient (standardised) | P-value | t(4, 32) | Partial correlation coefficient (r) | |

| Pecking stone consumption, kg/1,000 hens | 0.824 | <0.001 | 6.128 | 0.815 |

| Δ1 dMEAN, mm | −0.198 | 0.159 | −1.465 | −0.319 |

| Δ2 CP, g/100 g | −0.048 | 0.721 | −0.362 | −0.083 |

| Δ2 Phosphorus, g/100 g | 0.103 | 0.526 | −0.167 | 0.147 |

| Δ2 Sodium, g/100 g | 0.125 | 0.869 | 0.647 | −0.038 |

| Model Summary | ||||

| R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-change | Significant F-change |

| 0.830 | 0.689 | 0.608 | 8.435 | <0.001 |

Δ dMEAN = dMEAN offered in feed subtracted from dMEAN in leftover feed

Δ nutrients = Nutrient determined in the control sample collected from the hopper minus the nutrient detected in the leftover feed

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to record the effects of pecking stones on feeding behaviour and beak length in free-range laying hens. Although a linear increase in pecking stone consumption with age was observed on both farms, hens housed on farm B (not beak trimmed) consumed significantly more pecking stones at all ages compared with hens housed on farm A (infrared beak trimmed). Consumption of the pecking stones themselves did not affect (reduce) the beak length of hens with intact beak nor affected the beaks of those hens that were beak treated with the infrared treatment at the hatchery. Anecdotal observation indicated rounding of beak tips in treatment hens indicating abrasive effects of pecking stone (Glatz and Runge, 2017). Pecking stone consumption indicated that this form of environment enrichment was well accepted by hens used in the current study. Un-manipulated hens with intact beaks may be more likely to use their beaks to explore, scratch, and search for feed. This may explain why hens on farm B consumed more pecking stones than those on farm A. Infrared beak trimming had been reported to be associated with behavioural changes associated with pain, e.g., more sitting and sleeping, less walking and running, less feeding and pecking the environment (Gentle and McKeegan, 2007). However, Gentle and McKeegan (2007) showed that 6 weeks after beak trimming had been conducted, the pain indicators assessed for hen welfare were absent. In addition, the frequency of pecking directed towards the environment is known to increase with age in infrared beak trimmed hens (Gentle and McKeegan, 2007). Although infrared beak trimming can be considered as more welfare friendly than hot blade trimming, research investigating the effects of infrared beak trimming, including alterations in pecking behaviour such as feeding behaviour is rare (Dennis et al., 2009).

Hens in the treatment groups housed on farms A and B selected particles and consumed significantly lower quantities of large feed particles, as well as a lower intake of dMEAN than hens that were not offered pecking stones (control) at certain ages. The beak length was correlated with reduced consumption of feed particle size. Thus, we can speculate that pecking stones may influence the feeding behaviour of beak trimmed, as well as non-trimmed hens. Although, increased pecking at a pecking device has been reported (Moroki and Tanaka, 2016), published data on effects of pecking stone on feed pecking efficiency or alteration in feeding behaviour is very infrequent. The critical age for chicks to learn pecking a substrate is when they approximately reach 10 d of age (Vestergaard and Baranyiova, 1996). Whilst in this experiment, hens in the treatment group were first exposed to the pecking stones at 16 weeks of age, exposing the pullets at an earlier age to a new substrate may alter their pecking behaviour during the laying period more significantly (Vestergaard and Baranyiova, 1996). The selection of feed particles behaviour is more complex than just grasping particles (Rogers, 1995, Van Rooijen, 1991). It involves the early life experience of pecking, coupled with a combination of visual, olfactory and tactile execution learned from the environment (Hale and Green, 1988, Hausberger, 1992, Hogan-Warburg and Hogan, 1981). Thus, future research with the provision of pecking stones at an early age may provide a deeper insight into the alteration of feeding behaviour.

Although non-significant effects on protein consumption were observed, previous published data reported lower protein percentages (16.7%) in the leftover feed of beak trimmed hens (Persyn et al., 2004). It has been reported that hens with intact beaks used to peck on feed resulting in consuming more large particles (whole grains) compared with scooping of smaller particles (meal, premix) performed by hens with trimmed beaks (Glatz, 2003, Persyn et al., 2004, Portella et al., 1988). The beak length of 10 to 11 mm compared with 13 to 15 mm was recognised as the most important single factor influencing the feeding behaviour (Glatz, 2003, Persyn et al., 2004). However, the minimum beak length of hens on farm A was 13.1 mm, whilst at farm B was 15.2 mm.

Pecking stones have an abrasive surface, and it was hypothesised that pecking stone usage may result in blunting of the beak. This blunting of beaks was not observed in the present study, as beak length did not decrease over time, and did not differ significantly in hens of the treatment group compared with hens of the control group. However, a decrease in large particle consumption on both farms, as well as a negative correlation of beak length with dMEAN consumption should be assessed in respect of the sensory innervation. Although non-significant effects of pecking stones were observed on beak length, previous findings reported reduction in sharpness of beak tip (Glatz and Runge, 2017). The chicken beak has very well-developed linkages with the trigeminal nerve, and also contains free nerve endings as well as Herbst and Merkel corpuscles (Desserich et al., 1983, Desserich et al., 1984). The specialised dermal papillae on the tip of the lower beak also has a number of free nerve endings (Breward and Gentle, 1985). Future research investigating the effect of pecking stone consumption on the sensory stimulation of beaks would illuminate this area.

Variation in Na consumption in hens offered pecking stones and on altered intake of Mg and P on both farms over time should be considered as a direct result of antagonism or synergism of minerals. All diets offered to the hens in the current experiment were appropriately balanced and contained all the nutrients suggested by the Hy-Line feeding manual (Brown, 2016). However, potassium, phosphorus and zinc contents in the offered diets differed significantly on both farms at different time points. In addition, as pecking stones are an additional source of mineral supplementation, other considerations such as availability of minerals from the range area, and minerals available from the drinking water may potentially impact the mineral intake of hens. Thus in future research, mineral availability from the pecking stone, from the range area, and from the drinking water should be considered in relation to the hen's diet in order to meet specific requirements.

5. Conclusion

Based on the results obtained, we can conclude that although beak length was not affected by pecking stone consumption, the presence of pecking stones altered large particle feed intake. Further research is advisable with the provision of pecking stones at an early age (e.g., rearing period) to allow for a comparative investigation of pecking stones effects on beak length, including sensory organs and beak shape.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no known conflict of interests of financial, professional or personal matters that could have influenced this research.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Poultry CRC, established and supported under the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres Program. Poultry CRC, PO Box U242, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia. This study was also funded by DSM Nutritional Products, Singapore (project number 1.5.10).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Angevaare M.J., Prins S., van der Staay F.J., Nordquist R.E. The effect of maternal care and infrared beak trimming on development, performance and behavior of Silver Nick hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2012;140:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International . 18th ed. AOAC Int; Gaithersburg, MD: 2005. Official methods of analysis of the AOAC international. [Google Scholar]

- Breward J., Gentle M. Neuroma formation and abnormal afferent nerve discharges after partial beak amputation (beak trimming) in poultry. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1985;41(9):1132–1134. doi: 10.1007/BF01951693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. Institut de Selection Animale, BV; Boxmeer, the Netherlands: 2016. Nutrition Management Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis R., Fahey A., Cheng H.W. Infrared beak treatment method compared with conventional hot-blade trimming in laying hens. Poultry Sci. 2009;88(1):38–43. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desserich M., Fölsch D., Ziswiler V. Beak trimming in chickens. A procedure for an innervated area. Tierarzt Prax. 1983;12(2):191–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desserich M., Folsch D., Ziswiler V. Schnabelkupieren bei Huhnern. Ein Eingriff im innervierten Bereich. Tierarzt Prax. 1984;10(1):191–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentle M., Hughes B., Fox A., Waddington D. Behavioural and anatomical consequences of two beak trimming methods in 1-and 10-d-old domestic chicks. Br Poult Sci. 1997;38(5):453–463. doi: 10.1080/00071669708418022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentle M., McKeegan D. Evaluation of the effects of infrared beak trimming in broiler breeder chicks. Vet Rec. 2007;160(5):145. doi: 10.1136/vr.160.5.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilani A.-M., Knowles T.G., Nicol C.J. The effect of rearing environment on feather pecking in young and adult laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;148(1):54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Glatz P., Runge G. vol. 1. Australian egg corporation limited; Sydney Australia: 2017. (Managing fowl behaviour). [Google Scholar]

- Glatz P. Effect of poor feather cover on feed intake and production of aged laying hens. Asian Australian J Anim Sci. 2001;14(4):553–558. [Google Scholar]

- Glatz P. The effect of beak length and condition on food intake and feeding behaviour of hens. Intern J Poult Sci. 2003;2(1):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hale C., Green L. Effects of early ingestional experiences on the acquisition of appropriate food selection by young chicks. Anim Behav. 1988;36(1):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberger M. Visual pecking preferences in domestic chicks. Part II. The role of experience in their maintenance or not. Comptes rendus de l'Academie des sciences Serie III Sciences de la vie. 1992;314(7):331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera J., Saldaña B., Guzmán P., Cámara L., Mateos G. Influence of particle size of the main cereal of the diet on egg production, gastrointestinal tract traits, and body measurements of brown laying hens1. Poultry Sci. 2016;96(2):440–448. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan-Warburg A., Hogan J. Feeding strategies in the development of food recognition in young chicks. Anim Behav. 1981;29(1):143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R., McAdie T.M., McCorquodale C., Keeling L. Pecking at other birds and at string enrichment devices by adult laying hens. Br Poult Sci. 2002;43(3):337–343. doi: 10.1080/00071660120103602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Does occasional movement make pecking devices more attractive to domestic chicks? Br Poult Sci. 2001;42(1):43–50. doi: 10.1080/00071660020035064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde R., Cheng H.W. Different effects of infrared and one-half hot blade beak trimming on beak topography and growth. Poultry Sci. 2010;89(12):2559–2564. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroki Y., Tanaka T. A pecking device as an environmental enrichment for caged laying hens. Anim Sci J. 2016;87(8):1055–1062. doi: 10.1111/asj.12525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persyn K.E., Xin H., Nettleton D., Ikeguchi A., Gates R.S. Feeding behaviors of laying hens with or without beak trimming. Trans ASAE. 2004;47(2):591. [Google Scholar]

- Petek M., McKinstry J.L. Reducing the prevalence and severity of injurious pecking in laying hens without beak trimming. Uludag Univ J Facult Vet Med. 2010;29(1):61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Portella F., Caston L., Leeson S. Apparent feed particle size preference by laying hens. Can J Anim Sci. 1988;68(3):915–922. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers L.J. CAB international; 1995. The development of brain and behaviour in the chicken. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhnke I., Röhe I., Krämer C., Boroojeni F.G., Knorr F., Mader A. The effects of particle size, milling method, and thermal treatment of feed on performance, apparent ileal digestibility, and pH of the digesta in laying hens. Poultry Sci. 2015;94(4):692–699. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen J. Feeding behaviour as an indirect measure of food intake in laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1991;30(1):105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard K., Baranyiova E. Pecking and scratching in the development of dust perception in young chicks. Acta Vet Brno. 1996;65(2):133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P., Arlinghaus M., Kamphues J., Sauer N., Modsenthin R. Impact of feed particle size on nutrition digestibility and performance in pigs. Übers Tierern. 2012;40:21–64. [Google Scholar]