Abstract

Background

Feedback is a critical element of graduate medical education. Narrative comments on evaluation forms are a source of feedback for residents. As a shared mental model for performance, milestone-based evaluations may impact narrative comments and resident perception of feedback.

Objective

To determine if milestone-based evaluations impacted the quality of faculty members’ narrative comments on evaluations and, as an extension, residents’ perception of feedback.

Design

Concurrent mixed methods study, including qualitative analysis of narrative comments and survey of resident perception of feedback.

Participants

Seventy internal medicine residents and their faculty evaluators at the University of Utah.

Approach

Faculty narrative comments from 248 evaluations pre- and post-milestone implementation were analyzed for quality and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency by area of strength and area for improvement. Seventy residents were surveyed regarding quality of feedback pre- and post-milestone implementation.

Key Results

Qualitative analysis of narrative comments revealed nearly all evaluations pre- and post-milestone implementation included comments about areas of strength but were frequently vague and not related to competencies. Few evaluations included narrative comments on areas for improvement, but these were of higher quality compared to areas of strength (p < 0.001). Overall resident perception of quality of narrative comments was low and did not change following milestone implementation (p = 0.562) for the 86% of residents (N = 60/70) who completed the pre- and post-surveys.

Conclusions

The quality of narrative comments was poor, and there was no evidence of improved quality following introduction of milestone-based evaluations. Comments on areas for improvement were of higher quality than areas of strength, suggesting an area for targeted intervention. Residents’ perception of feedback quality did not change following implementation of milestone-based evaluations, suggesting that in the post-milestone era, internal medicine educators need to utilize additional interventions to improve quality of feedback.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-04946-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: graduate medical education, milestones, medical education qualitative methods

INTRODUCTION

Feedback on clinical performance is an essential component of learning for residents in graduate medical education.1, 2 Residents utilize feedback from faculty to improve performance and master complex clinical skills. Historically, faculty feedback to residents has varied in quality of content as well as delivery.2, 3 Residents perceive receiving little feedback on clinical skills and report the majority of feedback received is vague and not beneficial to development.4–6 It is unclear if resident perception correlates with the actual quality of feedback content.4

While multiple interventions to improve faculty feedback have been published, application is often limited due to time and resource constraints.2, 3 As part of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program requirements, residents have access to evaluations completed by faculty following each clinical rotation.7 Narrative comments on evaluation forms are formative and evaluative, providing assessment of progress to residents and program directors. More importantly, residents value comments on these forms as a source of feedback.8 Changes to rotation evaluation forms may impact the quality and perception of feedback, making this a feasible and potentially beneficial intervention to improve feedback provided by faculty to residents.

As part of the Next Accreditation System, the ACGME along with relevant American Board of Medical Specialties introduced the concept of milestones—competency-based developmental outcomes—to graduate medical education.9 The purpose of milestones was to provide a transparent and explicit expectation of performance, encourage self-assessment and self-directed learning with guided personal action plans for improvement, and facilitate more specific feedback from the program and faculty.10 Shortly after milestones were introduced, a modest majority of internal medicine residents thought feedback in milestone format would be more helpful in identifying areas of strength, weakness, specific areas for improvement, and rate of progression in professional development.11 In addition, members of internal medicine residency clinical competency committees believed that milestones would make it easier for faculty to provide specific feedback by comparing resident performance with examples of desired skills.12

While the impact of milestone-aligned rotation evaluation forms (henceforth termed: milestone-based evaluation forms) on quantitative data is suggestive of reduced rater error and the ability to better differentiate level of training, the impact on narrative comments is unclear.13, 14 Comments can be valuable resources for trainees to review if they contain specific information and constructive criticism.8, 15 Narrative comments can also be sources of information for program leadership to determine how residents are performing.16, 17 Ongoing work on the formation of narrative comments on evaluation forms suggests they are a construct of the content of the form itself, but also informed by pragmatic concerns such as politeness and fear of inclusion on the resident’s permanent record.16 Milestone-based evaluation forms provide a clear framework for expected performance allowing for comparison of performance to specific examples, and faculty perceive that this can translate into improved quality of comments on resident performance.18 However, if faculty feel that an area was adequately addressed by their rating of a milestone, or that the milestone-based evaluation requires more time to complete, it could hinder narrative comments.18

Therefore, we conducted this study to determine if milestone-based evaluation forms impacted the quality of faculty members’ narrative comments and, as an extension, residents’ perception of verbal feedback and narrative comments. Based on prior literature, we hypothesized that milestone-based evaluation forms would have an impact on narrative comment quality, but we did not specify if the quality would increase or decrease. Informed by prior work regarding milestones, we hypothesized residents would perceive improvement in quality of both verbal feedback and narrative comments following milestone implementation. This study was designed to inform the allocation of future faculty development resources around the introduction of milestones, by determining if a milestone-based evaluation form alone would change the quality of narrative comments and/or residents’ perception of feedback quality or if further faculty development was required.

METHODS

This study used a concurrent mixed methods design. Survey data was used to gather information on resident perception of feedback in the program around the time of milestone implementation, and qualitative analysis of narrative comments complemented this data by verifying the quality of feedback delivered to residents. The study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted with the University of Utah School of Medicine Internal Medicine residency training program. Milestone-based evaluation forms were introduced in January 2015. We gathered all faculty evaluation forms of program year 1–3 internal medicine residents on inpatient medicine ward rotations from August 2014 to December 2014 (pre-milestone implementation) and from August 2015 to December 2015 (post-milestone implementation) with January–July 2015 being considered a washout period as faculty adjusted to a new evaluation form. Evaluation forms of residents who were part of the training program for both pre- or post-milestone implementation were included in the study sample; forms from inpatient subspecialty rotations outside of internal medicine and of preliminary interns and any form completed by a group of faculty were omitted. Since accompanying survey data was collected at the resident level and the number of residents that each faculty member rates in a 6-month period varies, we did not want our results to be driven by a faculty member who rates many residents. Thus, we randomly sampled one evaluation form using SPSS from each internal medicine faculty member for pre- and post-milestone implementation periods.

Seventy residents were a part of the training program for both pre- and post-milestone implementation; an additional 54 residents were part of the training program only for pre-milestone implementation, and 59 residents only for post-milestone implementation. The residents who were a part of the training program for both pre- and post-milestone implementation were surveyed on their perception of verbal feedback and narrative comment quality.

Evaluation Forms and Coding of Narrative Feedback Comments

The evaluation forms pre- and post-milestone implementation had 9 and 10 components respectively in which faculty rated resident performance according to components of the ACGME competencies of patient care, medical knowledge, problem-based learning, professionalism, system-based practice, and interpersonal skills and communication. Both forms had the same open-ended prompt (“Comments:”) at the end of the evaluation and were completed online via E*Value. The evaluation form is provided in online in Appendix A.

Prior qualitative work evaluating the content of narrative comments on medical resident evaluation forms revealed variable frameworks applicable to specific country of training.19 Our rubric, while independently formulated, reflected this prior work by categorizing comments into ACGME competencies, as well as an area of strength or area for improvement. The rubric is provided online in Appendix B. At the time of our study, no prior work categorized the quality of narrative comments on residency evaluation forms. Therefore, our rubric for quality (Table 1) was designed based on proposed qualities of effective feedback that could be coded from an independent source of narrative comments.1 To support content validity evidence, a medical educator developed the rubric and two faculty members and research assistants reviewed it for clarity/usability. Two research assistants, blinded to evaluation date, coded all narrative comments independently. Any disagreement in coding was discussed until consensus was reached so inter-rater reliability was not analyzed. The two research assistants were undergraduate students who were trained in the qualitative coding process and meaning of ACGME competencies by a PhD educational psychologist. Rater calibration training was conducted in a separate meeting with a sample of comments prior to the study sample coding to ensure research assistants had similar perceptions of each ACGME competency and comment quality categorization.

Table 1.

Representative Narrative Comments with Application of Rubric for Qualitative Analysis

| Example comment | Categorization based on area addressed and ACGME competency* | Quality rating for strength↑ | Quality rating for improvement↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Dr. X is a pleasure to work with. He did a good job on his ambulatory rotation. He has good medical knowledge and works nicely with his patients. He is thoughtful in his patient assessments/plans.” | Area of strength—patient care, medical knowledge | 1 | n/a |

| “Exceeds expectations for early rotation in first year.” | Area of strength—non-ACGME competency related | 0 | n/a |

| “X has a good grasp of basic medical knowledge. I thought that at times she had difficulty cooperating with the hospital staff and that she needs to work on more effective and clear communication with patients and families.” |

Area of strength—medical knowledge Area for improvement—interpersonal and communication skills |

0 | 2 |

| “I have never given such a poor evaluation to a resident at the VA, as I make allowances for their level of experience and I do not ask a lot. However this resident seemed to expect to receive education while he merely passively received it. He asked me once to give him ‘some pearls’. I do not think it ever occurred to him that pearls are not given to you, you have to dive for them. This involves showing some interest in the subject, showing initiative, reading about your cases and asking questions.” | Area for improvement—practice-based learning and improvement | n/a | 1 |

n/a not applicable

*ACGME competencies included: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, systems based practice, and non-ACGME competency-related comments

↑Quality was assigned as 0 = vague, 1 = specific comment, 2 = specific comment with example/support for claim, 3 = specific comment with example/support for claim written in non-evaluative/non-judgmental language. The highest quality comment per area was used to assign rating

Feedback Quality Survey

To understand the impact of milestone introduction on resident perception of verbal feedback and narrative comment quality, residents were surveyed in January 2015 and 2016, at the end of the defined pre- and post-milestone implementation periods. A literature search revealed no known feedback quality survey specific to generalized verbal feedback or narrative comments so the survey was designed based on Ende’s proposed qualities of effective feedback.1 The survey was constructed by the program director and a medical educator and reviewed by five chief medical residents for clarity and understanding, and subsequently, the elements of quality for verbal feedback and narrative comments were refined for applicability. The final survey (available online in Appendix C) asked residents to rate how often they received feedback based upon 8 verbal and 6 narrative elements of quality, on a 0 to 5 scale where 0 = Never, 1 = 1–20% of the time, 2 = 21–40% of the time, 3 = 41–60% of the time, 4 = 61–80% of time, and 5 = 81–100% of the time. Surveys were administered online via Survey Monkey and completed while the survey was open over a 1-month period of time with one reminder e-mail sent at 2 weeks.

Data Analysis

The frequencies and percentages of area of strength and/or area for improvement narrative comments categorized by (1) ACGME competency and (2) quality were computed for the pre-and post-milestone samples. A narrative comment quality score was assigned as summarized in Table 1. To determine if and how narrative comment quality changed with milestone implementation, we compared the pre- and post-milestone average narrative comment quality scores with a 2 (milestones, pre/post) × 2 (area, strength/improvement) ANOVA. Although an evaluation form could have both an area for improvement and area of strength, we treated this variable as independent since this did not apply uniformly to the study sample.

Data were only analyzed for residents who completed both the pre- and post-milestone surveys. Total resident perceived feedback quality scores were computed by summing ratings across the 8 items for verbal feedback and the 6 items for narrative comments pre- and post-milestones. The pre- and post-milestone resident perceived feedback quality scores (narrative, verbal) were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

RESULTS

Qualitative Results of Narrative Comments

Sixty-three faculty members completed at least one form in both the pre- and post-milestone implementation periods; an additional 48 faculty members completed at least one evaluation form but only during the pre-milestone implementation period, and 74 completed at least one evaluation form but only during the post-milestone implementation period. The randomized samples for the 185 faculty members included 111 pre-milestone evaluation forms and 137 post-milestone evaluation forms.

Ninety-nine percent (246) of the 248 evaluation forms had comments about an area of strength and 9% (22) had comments about areas for improvement. Table 2 provides the frequency and percentages of narrative comments by ACGME competency. The 246 areas of strength comments were most frequently about something not specific to an ACGME competency (e.g., good job) (40% pre- and 43% post-milestone), followed by something specific to patient care (38% pre- and 35% post-milestones) and interpersonal/communication skills (26% pre- and 29% post-milestones). Interpersonal/communication skills and patient care were the most frequently commented on areas for improvement pre-milestones (89% and 56% respectively). There was a decrease in the frequency of comments regarding all ACGME competencies post-milestones.

Table 2.

ACGME Competencies Addressed in Narrative Comments Pre- and Post-Milestone Implementation

| ACGME competency | Area of strength | Area for improvement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-milestones (N = 109) | Post-milestones (N = 137) | Pre-milestones (N = 9) | Post-milestones (N = 13) | |||||

| Patient care | 41 | 38%* | 48 | 35% | 5 | 56% | 4 | 31% |

| Medical knowledge | 4 | 4% | 9 | 7% | 2 | 22% | 1 | 8% |

| Practice-based learning and improvement | 13 | 12% | 15 | 11% | 3 | 33% | 2 | 15% |

| Interpersonal and communication skills | 28 | 26% | 40 | 29% | 8 | 89% | 2 | 15% |

| Professionalism | 7 | 6% | 21 | 15% | 2 | 22% | 2 | 15% |

| Systems-based practice | 5 | 5% | 6 | 4% | 3 | 33% | 2 | 15% |

| Non-ACGME competency-related comments | 44 | 40% | 59 | 43% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 15% |

*Multiple competencies and multiple areas (strength and improvement) could be addressed in a single evaluation comment so the percentages in each column do not add up to 100%

Table 3 provides the number and percent of narrative comment quality categorization for areas of strength and areas for improvement comments pre- and post-milestones. The majority of areas of strength comments were vague (64% pre- and 68% post-milestones) with few comments having an example (5% pre- and 3% post-milestones). The majority of the areas for improvement comments were either specific (44% pre- and 46% post-milestones) or specific with an example (44% pre- and 15% post-milestones). Very few comments met the highest feedback quality indicator.

Table 3.

Feedback Quality Categorization for Narrative Comments Pre- and Post-Milestone Implementation

| Feedback quality indicator categorization | Area of strength | Area for improvement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-milestones | Post-milestones | Pre-milestones | Post-milestones | |||||

| Vague comment | 70 | 64% | 93 | 68% | 1 | 11% | 4 | 31% |

| Specific comment | 33 | 30% | 38 | 28% | 4 | 44% | 6 | 46% |

| Specific comment with example/support for claim | 5 | 5% | 5 | 3% | 4 | 44% | 2 | 15% |

| Specific comment with example/support for claim written in non-evaluative/non-judgmental language | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 0 | 9% | 3 | 8% |

| Total | 109 | 137 | 13 | 9 | ||||

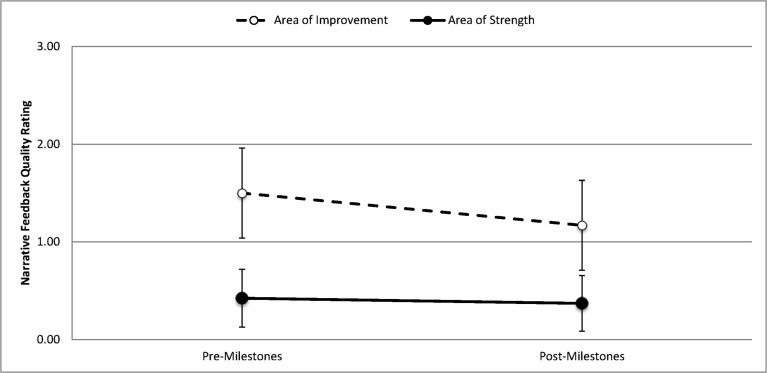

Figure 1 illustrates average narrative comment quality ratings pre- and post-milestones for areas of strength and areas for improvement. There was a main effect of area with higher quality ratings for areas for improvement comments compared to areas of strength, F(1,264) = 29.23, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.10. There was not a significant main effect of milestones, F(1,264) = 1.81, p = 0.180, and there was not an interaction of area by milestones, F(1,264) = 0.99, p = 0.320.

Figure 1.

Average narrative feedback quality ratings pre- and post-milestones implementation* (*narrative feedback quality score: 0 = vague comment, 1 = specific comment, 2 = specific comment with example/support for claim, 3 = specific comment with an example/support for claim written in non-evaluative/non-judgmental language.

Residents’ Perception of Feedback Quality

The response rate for the residents who completed the survey both pre- and post-milestones was 86% (N = 60/70). The majority of residents agreed or strongly agreed (95%, N = 57) that feedback was extremely important to their education both pre- and post-milestones. Table 4 provides the percent of residents who perceived that verbal feedback and narrative comments consistently achieved each of the quality indicators pre- and post-milestones. The percentages were low (< 23%) for each indicator. There were no differences between total pre- and post-ratings for narrative comments (pre: 20 (SD = 4), post: 19 (SD = 5)), p = 0.562, or verbal feedback (pre: 27 (SD = 7), post: 26 (SD = 7)), p = 0.840.

Table 4.

Resident Perception of Written and Verbal Feedback Pre- and Post-Milestone Implementation

| Element | Pre-milestones | Post-milestones | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N who said 81–100% of time | % who said 81–100% of time | N who said 81–100% of time | % who said 81–100% of time | |

| Written (narrative) feedback | ||||

| Well-timed and expected | 6 | 10 | 9 | 15 |

| Based on first-hand (observed) data | 10 | 17 | 11 | 18 |

| Limited to a reasonable quantity and types of behaviors that could be remediated | 7 | 12 | 8 | 13 |

| Phrased in straightforward, non-judgmental language | 13 | 22 | 13 | 22 |

| About specific performances, not generalizations | 4 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| Useful | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| Verbal (face-to-face) feedback | ||||

| Undertaken with your attending and you working as allies with common goals | 3 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Well-timed and expected | 5 | 8 | 9 | 15 |

| Based on first-hand (observed) data | 11 | 18 | 8 | 13 |

| Limited to a reasonable quantity and types of behaviors that could be remediated | 8 | 13 | 6 | 10 |

| Phrased in straightforward, non-judgmental language | 10 | 17 | 9 | 15 |

| About specific performances, not generalizations | 6 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

| About decisions and actions, rather than assumed intentions or interpretation | 4 | 7 | 5 | 8 |

| Useful | 6 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

DISCUSSION

Qualitative analysis of narrative comments from evaluation forms suggested low-quality ratings for the majority of comments pre- and post-milestone implementation. This was accompanied by internal medicine residents’ unchanged perception of receiving a low rate of high-quality verbal feedback or narrative comments pre- and post-milestone implementation. In this study of a single internal medicine residency program, there was no evidence of any significant impact of milestone-based evaluations on narrative comments or verbal feedback quality.

Similar to prior work, we found that our residents value feedback and think it is very important to their education.11 However, residents reported a low rate of quality in both verbal feedback and narrative comments across multiple domains including usefulness, which unfortunately is a trend documented throughout medical education literature.20–22 Our analysis of narrative comments supports resident perception, as the majority of commentary consisted of vague statements about resident strengths and are the type of comments that are known to not be valued as feedback.6, 15, 23 This likely contributes to the low rating of usefulness of verbal feedback and narrative comments. In regard to the content of comments, our work supports the use of analysis by competencies, as narrative comments covered all of the ACGME competencies.19, 20 Yet, a portion of comments did not refer to competencies and are of questionable utility to residents. Overall, improving the utility of both verbal feedback and narrative comments is an important area to target, as it could directly translate into changes in clinical care achieving the goal of improved patient outcomes.

Milestones can serve as a guide to feedback, but there is concern that implementation has made faculty feedback overly reliant upon them.10 The architects of milestones suggest that implementation should not be viewed as prescriptive but rather a blueprint for education.10 As programs become more familiar with milestones, additional faculty development is required to improve the content and delivery of verbal and written feedback.6, 24 One area for improvement, suggested by our findings, is the need for faculty to reinforce residents’ areas of strength via specific comments supported by examples.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. Generalizability is limited, as data was analyzed from a single institution and specialty. Our analysis of the quality of narrative comments may be open to interpretation, but findings are consistent with prior analysis of the content of narrative comments included on internal medicine student and resident evaluations.15, 19, 20 There is potential for survey respondents to over or under report feedback when relying on recall. However, it is still helpful to know residents’ perceptions, as their recall of feedback may be the data that they use to make changes in behavior.

In our study of feedback in the post-milestone era, we found that narrative comments provided to residents were not high quality and that resident perception of feedback has not been impacted by milestone-based evaluations. This suggests that introducing milestones to faculty by changing an evaluation form to align with milestones is not enough for changing feedback culture. Future work needs to identify if evaluation form prompts can be improved to help faculty write more specific and high-quality narrative comments, especially for areas of strength. However, changing prompts on evaluation forms is only one approach to tackle the paucity of quality feedback in medical education and more investment is needed in faculty development to improve high-quality narrative and verbal feedback to residents. Without high-quality feedback, residents will have a difficult time acting on narrative comments to improve and will be unable to reinforce positive behaviors that can translate into changes in patient care.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 178 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors

No additional contributors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777–781. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154–158. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bing-You R, Hayes V, Varaklis K, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. Feedback for learners in medical education: what is known? a scoping review. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1346–1354. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen AR, Wright AS, Kim S, Horvath KD, Calhoun KE. Educational feedback in the operating room: a gap between resident and faculty perceptions. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bing-You RG, Paterson J. Feedback falling on deaf ears: residents’ receptivity to feedback tempered by sender credibility. Med Teach. 1997;19(1):40–45. doi: 10.3109/01421599709019346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy ST, Zegarek MH, Fromme HB, Ryan MS, Schumann SA, Harris IB. Barriers and facilitators to effective feedback: a qualitative analysis of data from Multispecialty Resident Focus Groups. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):214–219. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00461.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine. 2017; https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/140_internal_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2018.

- 8.Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CP, Eva KW, Lingard L. Cracking the code: residents’ interpretations of written assessment comments. Med Educ. 2017;51(4):401–410. doi: 10.1111/medu.13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system--rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Edgar L, et al. Reflections on the First 2 Years of Milestone Implementation. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):506–511. doi: 10.4300/JGME-07-03-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus S, Moriarty J, Nardino RJ, Chmielewski A, Rosenblum MJ. Internal Medicine Residents’ Perspectives on Receiving Feedback in Milestone Format. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):220–224. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00446.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aagaard E, Kane GC, Conforti L, et al. Early feedback on the use of the internal medicine reporting milestones in assessment of resident performance. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):433–438. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00001.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett KW, Whicker SA, Bookman J, et al. Milestone-Based Assessments Are Superior to Likert-Type Assessments in Illustrating Trainee Progression. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):75–80. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00389.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman KA, Balwan S, Cacace F, Katona K, Sunday S, Chaudhry S. Impact on house staff evaluation scores when changing from a Dreyfus- to a Milestone-based evaluation model: one internal medicine residency program’s findings. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:25185. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.25185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulbas L, Guerin W, Ryder HF. Does what we write matter? Determining the features of high- and low-quality summative written comments of students on the internal medicine clerkship using pile-sort and consensus analysis: a mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:145. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0660-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Lingard L, Eva KW. Reading between the lines: faculty interpretations of narrative evaluation comments. Med Educ. 2015;49(3):296–306. doi: 10.1111/medu.12637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM, Eva KW. The hidden value of narrative comments for assessment: a quantitative reliability analysis of qualitative data. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1617–1621. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabors C, Peterson SJ, Forman L, et al. Operationalizing the internal medicine milestones-an early status report. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):130–137. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00130.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsburg S, Gold W, Cavalcanti RB, Kurabi B, McDonald-Blumer H. Competencies “plus”: the nature of written comments on internal medicine residents’ evaluation forms. Acad Med. 2011;86(10 Suppl):S30–34. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822a6d92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JL, Kay C, Jackson WC, Frank M. The quality of written feedback by attendings of internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):973–978. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmboe ES, Fiebach NH, Galaty LA, Huot S. Effectiveness of a focused educational intervention on resident evaluations from faculty a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):427–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330–1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delva D, Sargeant J, Miller S, et al. Encouraging residents to seek feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):e1625–1631. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kogan JR, Conforti LN, Bernabeo EC, Durning SJ, Hauer KE, Holmboe ES. Faculty staff perceptions of feedback to residents after direct observation of clinical skills. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):201–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 178 kb)