Abstract

Background

Research shows that stroke patients and their families are dissatisfied with the information provided and have a poor understanding of stroke and associated issues.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of information provision strategies in improving the outcome for stroke patients or their identified caregivers, or both.

Search methods

For this update we searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (June 2012), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED), and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (The Cochrane Library June, 2012), MEDLINE (1966 to June 2012), EMBASE (1980 to June 2012), CINAHL (1982 to June 2012) and PsycINFO (1974 to June 2012). We also searched ongoing trials registers, scanned bibliographies of relevant articles and books and contacted researchers.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials involving patients or carers of patients with a clinical diagnosis of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) where an information intervention was compared with standard care, or where information and another therapy were compared with the other therapy alone.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial eligibility and methodological quality and extracted data. Primary outcomes were knowledge about stroke and stroke services, and impact on mood.

Main results

We have added four new trials to this update. This review now includes 21 trials involving 2289 patient and 1290 carer participants. Nine trials evaluated a passive and 12 trials an active information intervention. Meta‐analyses showed a significant effect in favour of the intervention on patient knowledge (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.29, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12 to 0.46, P < 0.001), carer knowledge (SMD 0.74, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.43, P = 0.03), one aspect of patient satisfaction (odds ratio (OR) 2.07, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.23, P = 0.001), and patient depression scores (mean difference (MD) ‐0.52, 95% CI ‐0.93 to ‐0.10, P = 0.01). There was no significant effect (P > 0.05) on number of cases of anxiety or depression in patients, carer mood or satisfaction, or death. Qualitative analyses found no strong evidence of an effect on other outcomes. Post‐hoc subgroup analyses showed that active information had a significantly greater effect than passive information on patient mood but not on other outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence that information improves patient and carer knowledge of stroke, aspects of patient satisfaction, and reduces patient depression scores. However, the reduction in depression scores was small and may not be clinically significant. Although the best way to provide information is still unclear there is some evidence that strategies that actively involve patients and carers and include planned follow‐up for clarification and reinforcement have a greater effect on patient mood.

Plain language summary

Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers

Studies have shown that stroke survivors and their carers often report they have not been given enough information about stroke and feel unprepared for life after discharge from hospital. However, the best way to provide information after stroke is unclear. The authors of this review looked at the evidence for the effectiveness of providing information to patients, or carers of patients, who have had a stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), sometimes called a mini‐stroke. They examined randomised trials (studies) in which one group of stroke patients or carers who were given the intervention being tested (such as a course of lectures) was compared with a group of stroke patients or carers who received standard care. Twenty‐one studies, involving 2289 patients and 1290 carers, are now included in this updated review. Overall, the studies showed that providing information to patients and carers improved their knowledge of stroke and increased patient satisfaction with some, but not all, of the information they received about stroke. There was also an effect on reducing patient depression, although the reduction was small and may not be enough to seem meaningful to patients. When information was provided in a way that more actively involved patients and carers, for example by offering repeated opportunities to ask questions, it had more effect on patient mood than information which was given on one occasion only. There is not much evidence that providing information had effects on other aspects of patient or carer stroke recovery such as independence or social activities.

Background

Every year approximately 110,000 people in England have a stroke (National Audit Office 2005) and at any one time over 300,000 people are living with moderate to severe disability as a result of a stroke (Adamson 2004). The provision of appropriate, accurate, timely information and advice about stroke has been recommended as a key component of service provision (Canadian Stroke Network 2006; RCP 2008; National Stroke Foundation Australia 2010). Information, combined with the right support, is the key to better care, better outcomes and reduced costs. Patients should have information and data on all aspects of health care, to enable them to share in decisions about their care and access appropriate services (Department of Health 2010). The information needs of people who have had a stroke and their carers are diverse and change over time. Information should be tailored to an individual's requirements and provided in a variety of formats (Department of Health 2007; Eames 2011), taking into account their stroke‐specific impairment and personal situation (RCP 2008).

There is a wide range of nationally and locally produced leaflets, booklets, videos and audio tapes available for patients and carers. However, despite this emphasis on giving information, research suggests that patients' understanding of stroke, its consequences and the support available, remains poor. A recent systematic review identified multiple and diverse unmet educational needs by stroke patients and their caregivers (Hafsteinsdottir 2011). In a survey of community dwelling adults who suffered a stroke at least one and up to five years previously, over half reported wanting more information about their stroke (McKevitt 2011).

In a UK study, carers of stroke patients reported that whilst leaflets were available, they were not always appropriate to the situation (Mackenzie 2007). A survey by primary care trusts in England, of the information provided to patients after stroke, reported that the majority provided good information. However, only 40% contained information relevant to local services. Furthermore, the size, content and organisation of the information varied extensively (Care Quality Commission 2011). Inadequate provision and receipt of appropriate information has important consequences for compliance with secondary prevention and the longer‐term psycho‐social outcome for patients and carers (O'Mahoney 1997). Enhanced knowledge of stroke care by carers may improve the quality of discharge home from hospital for stroke patients (Evans 1991). Despite the perceived and expressed need for information, successful strategies have not as yet been identified. In order to fully explore available evidence we have undertaken a systematic review of information provision for patients and their carers after stroke.

Description of the condition

A stroke is defined by the World Health Organization as: "Rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than vascular origin" (Aho 1980). A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is a brief reversible episode of focal, non‐convulsive ischaemic dysfunction of the brain with a duration of less than 24 hours (Adams 1998). Stroke can lead to death or physical and cognitive impairment (McKevitt 2011; Mukherjee 2011) and can have long lasting psychological and social implications (Knapp 2000).

Description of the intervention

The intervention is the provision of information for stroke survivors or their informal caregivers, or both, following a stroke or TIA. The intervention may be provided in a variety of formats such as leaflets, workbooks, or verbal communication including lectures or teaching sessions. Whilst the content of the intervention may vary, it is likely to contain at least one of the following components: information about the causes and nature of stroke; management and recovery from the effects of stroke; prevention or reducing the risk of future strokes; information on resources or services. Whilst the provision of information should be incorporated as standard practice following stroke, evidence suggests it is lacking or inconsistent (Mackenzie 2007; Care Quality Commission 2011).

How the intervention might work

If stroke survivors and carers are to be active in their decision making and management of the long‐term effects of stroke, appropriate information delivered in a timely and effective format is necessary. Information is considered necessary to recognise and act upon symptoms, manage disease exacerbation and to access effective treatments and medicines and produce better outcomes (Department of Health 2001; Department of Health 2010). Furthermore, inadequate provision of information has implications for compliance with secondary prevention and psycho‐social outcomes for stroke patients and carers (O'Mahoney 1997). Evidence from non‐stroke populations suggests providing written information improves adherence to hospital after‐care regimens (Gibbs 1989; Firth 1991) and may assist with self‐care (Coulter 1998), which may indirectly produce beneficial outcomes.

Why it is important to do this review

It has been proposed that information, combined with the right support, is the key to better care, better outcomes and reduced costs (Department of Health 2010). The information derived from this review has the potential to lead to the development of more effective information provision strategies and highlight which outcomes might be affected by such interventions.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to examine the effectiveness of information strategies provided with the intention of improving the outcome for stroke patients or their identified caregivers or both.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included unconfounded randomised trials where an information intervention was compared with standard care or where information and another therapy was compared with the other therapy alone.

Types of participants

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of stroke or TIA and their identified caregivers or both.

Types of interventions

Information provided with the intention of improving the outcome of patients or their caregivers or both. We excluded trials in which information‐giving was only one component of a more complex rehabilitation intervention, for example family support worker trials (Forster 1996; Dennis 1997; Mant 2000; Lincoln 2003; Ellis 2005), which are the subject of a separate Cochrane review (Ellis 2010).

Types of outcome measures

We considered that information provision would impact most directly on knowledge and patients' or carers' mood state (anxiety and depression) or both. Therefore, we used the following primary and secondary outcome measures to assess the effectiveness of information provision.

Primary outcomes

Patient or carer knowledge about stroke and stroke services or both.

Patient or carer impact on mood (e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

Secondary outcomes

Activities of daily living (e.g. Barthel Index).

Participation (e.g. London Handicap Scale).

Social activities (e.g. Frenchay Activities Index).

Perceived health status (e.g. Short‐form 36, Nottingham Health Profile).

Quality of life (e.g. Dartmouth Coop Chart).

Satisfaction with information.

Hospital admissions, service contacts or health professional contacts.

Compliance with treatment/rehabilitation (e.g. Miller's Health Behaviour Scale).

Death or institutionalisation or both.

Resource outcomes

Cost to health and social services.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged translation of papers published in languages other than English.

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched in June 2012). In addition, we searched the following electronic bibliographic databases and trials registers:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (1966 to June 2012) (Appendix 2);

EMBASE (1980 to June 2012) (Appendix 3);

CINAHL (1982 to June 2012) (Appendix 4);

PsycINFO (1974 to June 2012) (Appendix 5);

Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) (June 2012);

National Rehabilitation Information Center (www.naric.com) (June 2012);

RePORT Expenditures and Results (RePORTER) query tool (http://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm) (December 2012);

Internet Stroke Center stroke trials registry (www.strokecenter.org) (June 2012).

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials, we searched bibliographies of relevant articles and books and contacted authors of relevant research and previous articles on information provision.

For the previous version of the review we searched:

Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index (1981 to March 2007);

ASSIA (Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts) (1987 to March 2007);

Index to UK theses (1970 to March 2007);

Dissertation Abstracts (1961 to March 2007);

National Research Register (www.nrr.nhs.uk) (to September 2007);

Journal of Advanced Nursing (1996 to March 2007).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of records from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full text of the remaining studies and at least two review authors assessed these against the review inclusion criteria to determine which trials would be eligible for inclusion. The review authors resolved disagreements by discussion with other members of the review team.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors scrutinised all the eligible trials to grade methodological quality, patient selection, the intervention, outcome measures used, and length of follow‐up. We allocated studies to one of two categories ‐ passive information or active information ‐ according to the nature of the intervention. An intervention was classified as passive if the information was provided on a single occasion and there was no subsequent systematic follow‐up or reinforcement procedure. An intervention was classified as active if, following the provision of the information, there was a purposeful attempt to allow the participant to assimilate the information and a subsequent agreed plan for clarification and consolidation or reinforcement. We made this classification because it would inform future research and be helpful for service planners in terms of committing resources. Two review authors extracted data independently using piloted data extraction forms, and measured agreement. They resolved disagreement through group consensus. Where necessary, we contacted study authors for additional information and data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the methodological quality of selected studies using the tool for assessing risk of bias as described in section 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We scored each of the following domains as 'high risk of bias', 'low risk of bias', or 'unclear risk of bias' and reported them in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other possible bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We compared studies based on end‐of‐study results. We used the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous outcomes. We treated ordinal data as continuous data and combined them using the MD. We combined dichotomous data using the Peto odds ratio (OR).

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing, we performed an available case analysis. The proportion of participants in each study arm who did not provide data is shown in the 'Data and analyses' section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for the presence of heterogeneity between the trials using the I2 statistic. We used a fixed‐effect model if we detected no substantial heterogeneity (I2 < 50%). Where there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%) we used a random‐effects model.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were able to reduce reporting bias by undertaking comprehensive searches of multiple databases and trials registers, and contacting authors. There were no restrictions based on language and translations were undertaken if required. It was not possible to detect reporting bias by the method of assessment of funnel plots as there were insufficient studies included in the meta‐analyses.

Data synthesis

We compared studies based on the end‐of‐study results. Meta‐analyses have been undertaken for the domains of knowledge, emotional outcome, death and for selected satisfaction questions. For the domain of knowledge, we combined data using the SMD as all the trials had used different knowledge questionnaires. We combined dichotomous data (domains of mood, satisfaction, death) using the Peto OR. For the domain of mood, we dichotomised the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores, the Geriatric Depression Scale scores and the General Health Questionnaire scores using the recommended cut‐off points (Zigmond 1983; Sheikh 1986; Goldberg 1988). We treated ordinal data (domain of patient mood) as continuous data and combined them using the MD. For a number of studies both ordinal and dichotomised patient Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale data were available. If this was the case, we extracted and analysed both forms of data. For other outcomes, we present a narrative summary stratified by subgroup and a summary of the data is provided in the Data and analyses section.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We undertook post‐hoc subgroup analyses for the type of intervention (passive and active). We used the method described by Deeks et al (Deeks 2001) to compare the magnitude of treatment effect of the two subgroups.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this update we reviewed 28,110 titles; 134 papers were reviewed of which duplicate papers were identified for 14 studies, four new studies are included in the review (Johnston 2007; Chiu 2008; O'Connell 2009; Chinchai 2010). Of the 134 papers reviewed for this update, five were commentaries, reviews or meta‐analyses, seven trials included non‐stroke participants and six studies did not investigate the effectiveness of information provision after stroke; 43 studies have been added to the excluded studies section (details reported in Characteristics of excluded studies); 14 studies are currently pending assessment and 10 studies are currently ongoing.

Included studies

The current analysis includes 21 completed trials with 2289 patient and 1290 carer participants (Lomer 1987; Evans 1988; Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Banet 1997; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Johnson 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Larson 2005; Draper 2007; Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; Chiu 2008; O'Connell 2009; Chinchai 2010).

Setting

Three of the included trials were conducted in the USA (Evans 1988; Banet 1997; Johnson 2000), 11 in the UK (Lomer 1987; Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007), three in Australia (Draper 2007; Hoffmann 2007; O'Connell 2009), one in Sweden (Larson 2005), one in the Netherlands (Maasland 2007), one in Taiwan (Chiu 2008) and one in Thailand (Chinchai 2010).

Participants

In 19 trials the majority of patients were at least 60 years old (Evans 1988; Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Johnson 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Larson 2005; Draper 2007; Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; Chiu 2008; O'Connell 2009; Chinchai 2010). Two trials did not report age (Lomer 1987; Banet 1997). Six trials reported carer age (Evans 1988; Downes 1993; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Larson 2005; Draper 2007). Carers were younger than the patients, notably so in Evans 1988 where the mean age of the carers was under 50 years old. This study was carried out at a Veterans Administration Medical Centre and was also exceptional in that 94% of the stroke patients were male. In Larson 2005 the majority of spouses were female. Ten trials were concerned with the patient only (Pain 1990; Banet 1997; Frank 2000; Johnson 2000; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; Chiu 2008; O'Connell 2009) and in four trials the intervention involved the carer or spouse only (Evans 1988; Kalra 2004; Larson 2005; Draper 2007). In the remaining trials the focus of the intervention was the patient and carer (Lomer 1987; Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Johnston 2007; Chinchai 2010).

Interventions

Two of the included trials evaluated two interventions (Evans 1988; Downes 1993): one evaluated education and counselling (Evans 1988) and the other evaluated information provision plus counselling (Downes 1993). Only the data from the information/education group and the control groups have been analysed in this review.

Category

In nine studies we categorised the intervention as passive and in a further 12 studies we categorised the intervention as active. We considered that one of the 17 studies (Lowe 2007) exhibited features of both categories. We therefore sought further information from the lead author. Following discussion we agreed that it should be categorised as passive because information was provided on one occasion only with no subsequent opportunity for clarification and consolidation or reinforcement.

Content and administration

Nine trials evaluated a passive intervention (Lomer 1987; Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Banet 1997; Mant 1998; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; O'Connell 2009). In three trials (Lomer 1987; Downes 1993; Mant 1998) this comprised written generic information about stroke in the form of booklets and leaflets. In five studies (Pain 1990; Banet 1997; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007) the information was tailored to be of relevance to the individual. In Pain 1990 and Hoffmann 2007 participants were provided with individualised booklets. In Banet 1997 the intervention group were given a copy of their medical history, clinical résumés, test results and leaflets. In Maasland 2007 information was delivered via an individualised multimedia computer programme. In Lowe 2007 the intervention comprised personalised information presented by a research registrar who explained its contents and addressed any additional concerns. In O'Connell 2009, the intervention group were given a patient‐held record that included telephone numbers, generic stroke information and fact sheets relevant to the patient's specific stroke problems.

Twelve trials evaluated an active intervention (Evans 1988; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Johnson 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Larson 2005; Draper 2007; Johnston 2007; Chiu 2008; Chinchai 2010). In four trials (Evans 1988; Rodgers 1999; Johnson 2000; Larson 2005) the intervention consisted of a programme of lectures providing information about stroke and services available and an opportunity to ask questions. In addition to this, the four‐week course evaluated by Johnson 2000 emphasised the importance of self‐esteem and coping strategies. Participants in the trial by Larson 2005 were also able to contact the stroke specialist nurse between sessions for extra information and support. Five studies (Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Draper 2007) evaluated a multi‐component intervention. Carers in Kalra 2004 received instruction on a range of topics plus hands‐on training. In Frank 2000 the intervention consisted of a recovery plan, an interactive workbook and a weekly phone call from the researcher. In Draper 2007 the programme for carers of aphasic patients included communication strategies, relaxation and stress management. Patients and carers in Smith 2004 were provided with an information manual supported by fortnightly pre‐arranged review meetings with their multidisciplinary team. In Ellis 2005, the intervention group patients received a monthly review by a stroke nurse specialist, specially selected relevant written information, and personalised records detailing their individual risk factors and recommended risk factor targets. In Johnston 2007, participants received a workbook which provided information about stroke, task material such as goal setting and an audio relaxation tape. In Chiu 2008, the intervention consisted of information delivered by a pharmacist over a course of six sessions. In Chinchai 2010, the intervention consisted of lectures delivered to carers with weekly follow‐up reinforcement at home by health service volunteers. Further details of the interventions are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Timing

The intervention was implemented prior to discharge from hospital in nine trials (Lomer 1987; Evans 1988; Banet 1997; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; O'Connell 2009); within three weeks of discharge (Johnston 2007) and one month after stroke, or at discharge, which ever was sooner in one trial (Mant 1998). In the remaining trials the intervention was implemented at varying times post‐discharge: soon after discharge (Pain 1990; Downes 1993); within three months of stroke (Ellis 2005; Maasland 2007 ); within 12 months of stroke (Draper 2007); after 12 months since stroke (Chiu 2008); six months to three years after stroke (Johnson 2000); within 18 months of stroke (Chinchai 2010); within two years of stroke (Frank 2000), and a mean of 76 days after stroke onset (Larson 2005).

Outcomes measured

The studies measured a range of outcomes. Details of these are provided in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Assessment of knowledge

Ten trials evaluated patient or carer knowledge or both. All used different questionnaires, the majority of which had been specifically developed for the study. The questionnaire used by Evans 1988 had been validated (Stroke Care Information Test, range 0 to 36) (Evans 1985). The 26‐item knowledge of stroke scale used by Rodgers 1999 and the 17‐item knowledge of stroke and services questionnaire used by Smith 2004 were based on instruments used in other studies (Wellwood 1994; Drummond 1996; Mant 1998), and the content of the specific educational programme under evaluation. In the study by Hoffmann 2007, the 25‐item knowledge of stroke questionnaire developed for the study was based partly on a previously validated measure (Sullivan 2004). The content validity and test‐retest reliability of this instrument were assessed prior to the commencement of the study. The questionnaire used by Lowe 2007 was developed from professionals' ideas of what patients should be aware of concerning secondary prevention of stroke and was piloted with 58 stroke patients. In Maasland 2007 the questionnaire was developed and validated in 42 partners of patients with TIA. None of the questionnaires in the remaining three studies (Lomer 1987; Pain 1990; Mant 1998) had been validated.

Excluded studies

We excluded 51 studies because the information/education was part of a multiple component, complex rehabilitation intervention (Linn 1979; Christie 1984; Printz‐Feddersen 1990; Friedland 1992; Forster 1996; Dennis 1997; Goldberg 1997; Hochstenbach 1999; McKinney 1999; Napolitan 1999; Chang 2000; Rimmer 2000; Andersen 2002; Grant 2002; Nour 2002; Clark 2003; Hartke 2003; Leathley 2003; Boter 2004; Glass 2004; Harari 2004; Burton 2005; Tilling 2005; Claiborne 2006; Grasel 2006; Harwood 2006; Nir 2006; Boysen 2007; Desrosiers 2007; Ertel 2007; Habibzadeh 2007; Kendall 2007; Pierce 2007; Bakas 2008; Redfern 2008; Shyu 2008; Allen 2009; Battersby 2009; Chaiyawat 2009; Sahebalzamani 2009; Winkens 2009; Gillham 2010; Harrington 2010; Mackay‐Lyons 2010; Bacchini 2011; Chang 2011; Cheng 2011; Chumbler 2011; Clarke 2011; Holzemer 2011; Nguyen 2011), nine studies did not include a random allocation procedure (Evans 1984; Folden 1993; Morrison 1998; Ayana 2000; van den Heuvel 2000; Sit 2007; Huijbregts 2009; Oupra 2010; Brier 2011), we excluded three trials because information provision was not the evaluated intervention (Towle 1989; Mant 2000; Lincoln 2003), three trials included participants with conditions other than stroke and the data for stroke were not available separately (Sanguinetti 1987; Dongbo 2003; Brotons 2007), three trials included motivational interviewing (Green 2006; Adie 2010; Byers 2010) and four lacked a suitable control (Lorenc 1992; Skidmore 2008; Jones 2009; Neubert 2011).

Ongoing studies

Ten studies of potential relevance to this review are ongoing (Damush 2006; Boden‐Albala 2007; Shaughnessy 2007; Young 2007; Rochette 2008; Dromerick 2008; Graven 2008; Hackett 2008; Hoffmann 2009; O'Carroll 2010).

Studies awaiting assessment

There are 14 trials currently awaiting assessment (Bonita 1995; Jian 1998; Heier 2002; Andrea 2003; Choi 2006; Tuncay 2006; Ostwald 2007; Eames 2008; Piano 2010; Bodin 2011; Cameron 2011; Kim 2011; Sun 2011; Aben 2012). We are awaiting further information from authors.

Risk of bias in included studies

Method of analyses

Twelve studies reported that an intention‐to‐treat analysis had been conducted (Pain 1990; Banet 1997; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Johnson 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007).

Allocation

Allocation was concealed in nine trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; O'Connell 2009). Larson 2005 reported that the sequence could not be predicted but the method of allocation concealment was not reported. Allocation by random number sequence was reported in one study (Downes 1993). However, the method was not described. Johnson 2000 used a matched pair design with one member of each pair randomly assigned (unconcealed randomisation) to either the treatment or control group. The method of random sequence generation was unclear or not reported in 11 trials (Lomer 1987; Pain 1990; Banet 1997; Frank 2000; Smith 2004; Larson 2005; Draper 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; Chiu 2008; Chinchai 2010). One study reported the use of minimisation (Evans 1988). Ellis 2005 reported the use of a computer‐generated random sequence procedure. However, they reported that three patients were entered twice in to the treatment group in error. Further details of allocation concealment and methods of randomisation are provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Blinding

Blinding of both participants and personnel was not a feature in any of the trials or blinding was unclear. Blinding of outcome assessors was reported in 14 trials (Evans 1988; Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; O'Connell 2009; Chinchai 2010), not described in five (Lomer 1987; Banet 1997; Larson 2005; Draper 2007; Chiu 2008) and not undertaken in two (Frank 2000; Johnson 2000). Further details of blinding are provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Incomplete outcome data

The studies ranged in sample size from 36 (Pain 1990) to 300 (Kalra 2004). Losses to follow‐up ranged from zero (Lomer 1987; Johnson 2000; Chinchai 2010) to more than 20% (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; O'Connell 2009). A sample size calculation was reported for nine trials (Downes 1993; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Draper 2007; Hoffmann 2007; Maasland 2007; O'Connell 2009). Of these, Downes 1993 reported final follow‐up results for 62 couples rather than the estimated 165, and Draper 2007 recruited only 39 of the 60 caregivers required. Rodgers 1999 recruited the required number of patients and carers in each group but a larger than anticipated number of patients were unable to complete the main outcome measure (Short Form‐36) leading to a short fall in the number of patients required to meet the original power calculation (73%, 117 patients of 160). There was also a short fall in the number of carers at final follow‐up (106 of 216). In the O'Connell 2009 trial, a combination of recruitment and retention problems and non‐use of the intervention resulted in the trial being terminated prior to completion. Sample size was small in a number of trials, particularly: Pain 1990 (N = 36); Banet 1997 (N = 52); Frank 2000 (N = 41); Johnson 2000 (N = 41); and Draper 2007 (N = 39). Further details of attrition bias are provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Selective reporting

Study protocols were not obtained for any of the studies. As a result, it is unclear if selective reporting contributed to bias in the majority of studies. Further details of selective reporting bias are provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Other potential sources of bias

In the trial undertaken by Rodgers 1999, only 51 patients (42%) of those randomised attended three or more out of the six outpatient sessions provided. In Draper 2007, collection of baseline data occurred after randomisation (although participants were still blinded at that point). In O'Connell 2009, the trial was terminated early as it was reported that numerous participants could not remember receiving the information (a sample size of 240 was the initial target, however, the trial was stopped when 66 participants were recruited).

Effects of interventions

Results are reported separately for patients and carers. Resource outcomes are also presented separately. Meta‐analyses have been undertaken for the domains of knowledge, emotional outcome, death, and for selected satisfaction questions. For other outcomes we have presented a narrative summary stratified by subgroup, and a summary of the data are provided in the 'Data and analyses' section.

Patient outcomes

Knowledge

Seven trials (Lomer 1987; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007) evaluated the effect of a passive or active intervention on knowledge. All had used different questionnaires.

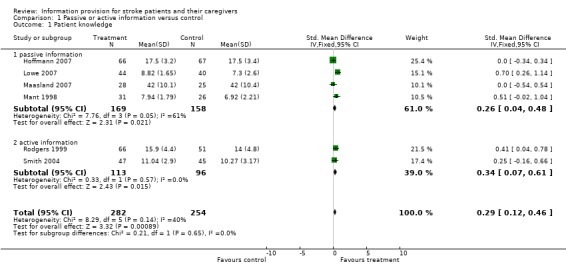

Patient knowledge

Data were available for 536 of 770 participants from six trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007). There was a statistically significant effect on patient knowledge in favour of the intervention (SMD 0.29, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.46, P < 0.001) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 1 Patient knowledge.

Suitable data were not available for one trial (Lomer 1987). Patients followed up at one week knew significantly more about the aetiology of stroke and the treatment they were receiving than the controls (P < 0.05) but not about the specific prognosis or help and benefits available. This was a small trial, methods of randomisation and outcome assessment are unclear, and comparability of treatment groups is not reported. The results may therefore be subject to bias.

Subgroup analysis

Data were available from four passive information and two active information trials. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of effect between passive and active information (passive: SMD 0.26, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.48, active: SMD 0. 34, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.61, test for subgroup differences P = 0.65) (Analysis 1.1).

Emotional outcomes

We performed meta‐analyses for the outcomes of patient anxiety and patient depression using both dichotomous and continuous data. For each outcome we report the results of both meta‐analyses. A narrative summary is presented for other outcomes.

Anxiety

The majority of trials that evaluated patient anxiety used the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. We converted scale data to dichotomised data using an anxiety subscale cut‐off score of 10/11(Zigmond 1983). Johnston 2007 reported data from the anxiety sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at baseline only and a total anxiety and depression score post‐intervention.

Patient emotional outcome: anxiety (dichotomised data)

Dichotomous data were available for 681 of 975 participants from six trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007). The pooled result for all trials showed no significant difference in the number of cases of anxiety between the intervention and control groups (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.38, P = 0.60) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 2 Patient emotional outcome: anxiety (dichotomised data).

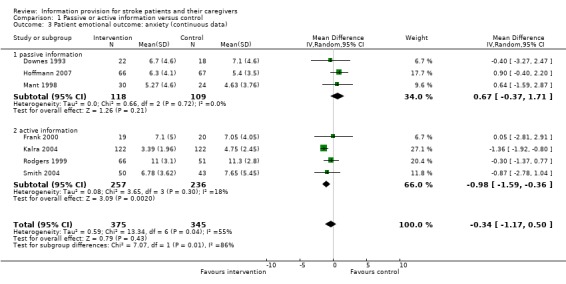

Patient emotional outcome: anxiety (continuous data)

Continuous data were available for 720 of 1016 participants from seven trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007). The pooled result for all trials showed no significant difference in anxiety scores between the intervention and the control groups (MD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐1.17 to 0.50, P = 0.43) (Analysis 1.3). Johnston 2007 was not included in the meta‐analysis as we were unable to obtain suitable data. However, they reported no significant difference between intervention and control at baseline (P > 0.05) and no significant effects post‐intervention (data and P value not reported).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 3 Patient emotional outcome: anxiety (continuous data).

Subgroup analysis

As there was no significant overall effect on anxiety, the following subgroup analyses may be unreliable.

Dichotomous data were available from three passive and three active information trials. The effect on anxiety was not significant in either subgroup (P > 0.05). However, there was a significant difference between active information and passive information on the number of cases of patient anxiety (passive: OR 1.64, 95% CI 0.80 to 3.37; active: OR 0.61 95% CI 0.35 to 1.07, test for subgroup differences P = 0.03). There was a trend towards an increase in anxiety from the passive information and a decrease from the active information.

Continuous data were available from three passive and four active information trials. The effect on anxiety was significant for the active information subgroup (P = 0.002) and not for the passive information subgroup (P = 0.21) There was a significant difference between active information and passive information on patient anxiety scores (passive: MD 0.67, 95% CI ‐0.37 to 1.71; active: MD ‐0.98 95% CI ‐1.59 to ‐0.36, test for subgroup differences P = 0.008). There was a trend towards an increase in anxiety from the passive information.

Depression

Twelve trials evaluated the effect of passive or active information on patient depression. Depression was measured using the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in eight trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007); Johnston 2007 reported the depression sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at baseline and a total score post intervention. Other measures included the Geriatric Depression Scale (short form) (Sheikh 1986) by (Ellis 2005); the Beck Depression Inventory (Gallagher 1982) by Johnson 2000, the Yale single question (Mahoney 1994) by Lowe 2007 and the emotions subscale of the Stroke Impact Scale (Duncan 1999) by O'Connell 2009. Scale data were converted to dichotomous data using the recommended cut‐off scores for each outcome measure (hospital anxiety and depression scale depression sub‐scale cut‐off score of 10/11 and a Geriatric Depression Scale score > 10).

Patient emotional outcome: depression (dichotomised data)

Dichotomous data were available for 956 of 1280 participants from eight trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007). The pooled result for all trials showed no significant difference in the number of cases of depression between the intervention and control groups (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.32, P = 0.59) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 4 Patient emotional outcome: depression (dichotomised data).

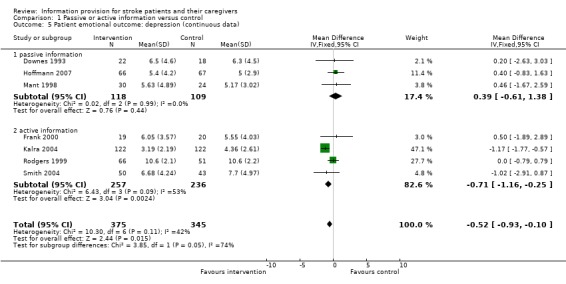

Patient emotional outcome: depression (continuous data)

Continuous data (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) were available for 720 of 1016 participants from seven trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007). There was a significant effect on depression scores in favour of the intervention (MD ‐0.52, 95% CI ‐0.93 to ‐0.10, P = 0.01) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 5 Patient emotional outcome: depression (continuous data).

Two trials were not included in the meta‐analysis as we were unable to obtain suitable data (Johnson 2000; Johnston 2007). Johnson 2000 reported no significant difference between the two groups at baseline but when all patients were reassessed one week after completion of the intervention phase (a four‐week education course), there was a significant difference in the mean depression scores measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (possible score range 0 to 63) (baseline: treatment group 12.52, control 12.94, F = 1.36, P < 0.53; follow‐up: treatment group 8.5, control 12.61, F = 2.79, P < 0.04). Johnston 2007 reported no significant difference between the intervention and the control at baseline (P > 0.05) and no significant effect post intervention (data and P value not reported).

Subgroup analyses

The following subgroup analyses for depression (dichotomous data) may be unreliable as there was no overall net effect.

Dichotomous data were available from four passive and four active information trials. The effect on depression was not significant in either subgroup (P > 0.05). However, there was a significant difference between active information and passive information on the number of cases of patient depression (passive: OR 1.57, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.93; active: OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.03, test for subgroup differences P = 0.02), with a trend in favour of active information.

Continuous data were available from three passive information and four active information trials. The effect on depression was significant in the active information subgroup (P = 0.002) and not in the passive information subgroup (P = 0.44). There was a significant difference between active information and passive information on patient depression scores (passive: MD 0.39, 95% CI ‐0.61 to 1.38; active: MD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.16 to ‐ 0.25, test for subgroup differences P = 0.05).

Other emotional outcomes

An active information study (Johnson 2000) evaluated hope and hopelessness (Herth Hope Scale, score range 0 to 90) (Farran 1995) and coping (Ways of Coping‐Cardiovascular Accident Scale, score range 0 to 93, specifically developed for the study). There were no differences between the two groups at baseline for either outcome. At one week after completion of the intervention phase (a four‐week education course), there was a significant difference between the two groups in the mean hope scale scores (baseline: treatment group 68.89, control 69.2, P < 0.42; follow‐up: treatment group 73.68, control 66.33, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the coping scores.

A further active information study (Johnston 2007) evaluated perceived control over recovery utilising the Recovery Locus of Control Scale (Partridge 1989). Scores from nine items on a five‐point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) are combined such that higher scores indicate greater belief in personal control. A confidence in recovery scale was also administered (Lewin 1992). This scale measured patients' confidence in recovery from 0 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident). There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the intervention and the control for perceived control over recovery. There was a significant group by time interaction effect for patients' confidence in recovery, F(1, 197) = 10.67, P = 0.001. Confidence in recovery declined over time for control group patients but remained relatively stable for patients in the intervention group.

Activities of daily living

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on activities of daily living. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in any of the four trials that evaluated this outcome (Pain 1990; Banet 1997; Mant 1998; O'Connell 2009).

Active information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of active information on activities of daily living. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in any of the four trials that evaluated this outcome (Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Draper 2007; Johnston 2007).

Participation

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on participation. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in any of the three trials that evaluated this outcome (Mant 1998; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007).

Active information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of active information on participation. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in any of the trials that evaluated this outcome (Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Draper 2007).

Social activities

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on social activities. The one trial that evaluated this outcome (Pain 1990) reported no significant difference in social activities between the intervention and control groups as measured by the Frenchay activities index (Holbrook 1983).

Active information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of active information on social activities. The two trials that evaluated this outcome (Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004) reported no significant differences in social activities between the intervention and control groups as measured by the Nottingham extended activities of daily living (Nouri 1987) or the Frenchay activities index (Holbrook 1983) respectively.

Perceived health status and quality of life

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on patient health status or quality of life (Dartmouth COOP Charts) (Rowan 1994) in the two trials that measured this outcome (Mant 1998; Hoffmann 2007).

Active information studies

Four trials (Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Kalra 2004; Ellis 2005) evaluated this outcome. Kalra 2004 reported significantly improved quality in life as measured by the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EuroQol Group 1990) at both three and 12 months in patients whose caregivers had received training (intervention) compared with those who had received conventional care (control) (median score (range) at three months: intervention 60 (42 to 70), control 50 (40 to 90), P = 0.019: median score (range) at 12 months: intervention 65 (55 to 80), control 60 (41 to 80), P = 0.009). Three trials (Rodgers 1999; Frank 2000; Ellis 2005) found no significant difference between the intervention and control groups as measured by the MOS 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF36) (Ware 1992), the Functional Limitations Profile (Patrick 1989) or the EuroQol (EuroQol Group 1990) respectively. Chinchai 2010 investigated quality of life with the WHO Quality of Life Measure (WHOQOL‐BRIEF THAI) (Sakthong 2007). There were significant within group differences (P < 0.05) in the intervention group for the physical, psychological and environmental categories. No significant within‐group differences (P > 0.05) resulted in the control group. Between‐group differences were reported pre‐intervention only (P > 0.05).

Satisfaction with care and information received

Eight trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; Lowe 2007; O'Connell 2009) evaluated patient satisfaction. Of these, four trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005) measured patient satisfaction using the Pound scale (Pound 1994) or a modified version of that scale. Additionally, the bespoke questionnaire used in the trial by Lowe 2007 included some common items. Meta‐analysis was performed for two questions that were considered to be most relevant to the review: (1) satisfaction with information about the causes and nature of stroke; and (2) satisfaction with information about allowances and services. Three trials did not contribute data to the meta‐analysis (Hoffmann 2007; Johnston 2007; O'Connell 2009). Hoffmann 2007 used a bespoke questionnaire, Johnston 2007 assessed satisfaction with treatment and advice using a 0 to 10 scale applied in a previous study (Morrison 2000). O'Connell 2009 evaluated whether participants in the intervention group recalled receiving and reading the information and taking action as a result of the information.

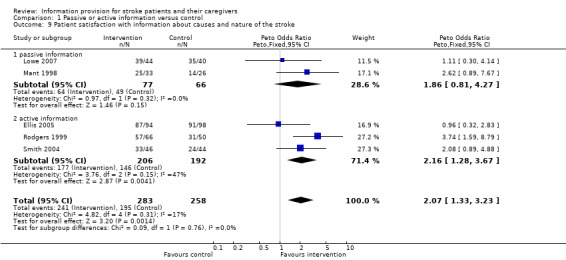

Patient satisfaction with information about causes and nature of the stroke

Data were available for 541 of 772 participants from five trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Lowe 2007). There was a significant difference in favour of the intervention in satisfaction with information about the causes and nature of stroke (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.23, P = 0.001) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 9 Patient satisfaction with information about causes and nature of the stroke.

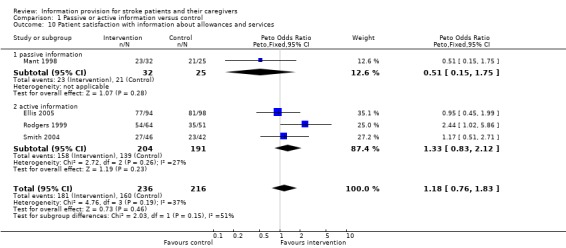

Patient satisfaction with information about allowances and services

Data were available for 452 of 672 participants from four trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005). There was no significant difference in satisfaction with information about allowances and services (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.83, P = 0.46) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 10 Patient satisfaction with information about allowances and services.

Subgroup analyses

Satisfaction with information about the causes and nature of the stroke

Data were available for two passive information and three active information trials. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of effect of passive compared to active information (passive: OR 1.86, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.27; active: OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.67, test for subgroup differences P > 0.2).

Satisfaction with information about allowances and services

There were insufficient data to perform a subgroup analysis.

Service use

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on service use in the one study (Mant 1998) that evaluated this outcome.

Active information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of active information on service use. The four trials that measured this outcome (Evans 1988; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004) reported that there was no significant difference in service use between the intervention and control groups.

Modification of health‐related behaviours or risk reduction

Passive information studies

There is no evidence of an effect of passive information on the modification of health behaviours or risk reduction. Two trials (Banet 1997; Lowe 2007) evaluated this outcome. One trial (Banet 1997) reported no statistically significant difference in scores for diet or medication between the group who received their medical records and the group that received information leaflets only, although actual results were not reported. In the other study (Lowe 2007) there were no statistically significant differences in blood pressure between the intervention group and control groups. In Maasland 2007, those who regularly used tobacco or alcohol reduced these behaviours more in the intervention group, but differences were not significant. There was a decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the intervention and control group but no significant difference between the groups. Patients in neither group reduced their weight. Serum cholesterol dropped significantly in both the intervention and the control group with no differences between the groups.

Active information studies

Three trials evaluated this outcome (Rodgers 1999; Ellis 2005; Chiu 2008). There is limited evidence of an effect of active information on the modifications of health behaviours or risk reduction from one study. In Chiu 2008, there was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) between the intervention and the control group for satisfactory management of blood pressure. However, there was insufficient information reported to determine the effectiveness of the blinding of patients, personnel or outcomes assessment and if allocation concealment was undertaken. There was no significant difference for the management of glucose or lipids. Two trials found no significant difference between the intervention and the control group. In Ellis 2005, they reported that their initial (planned) analysis appeared to demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in systolic blood pressure in the intervention group compared with the control group (P value not reported). However, when the analysis was repeated with adjustment for baseline blood pressure the difference was not significant (P = 0.126). There were no statistically significant changes in other major modifiable risk factors: systolic and diastolic blood pressure; reported smoking rate; cholesterol; random blood glucose; or HbA1c. In the other trial (Rodgers 1999) there was no significant difference in the numbers of patients who stopped smoking after the stroke (intervention 9/25, control 3/17, P = 0.44).

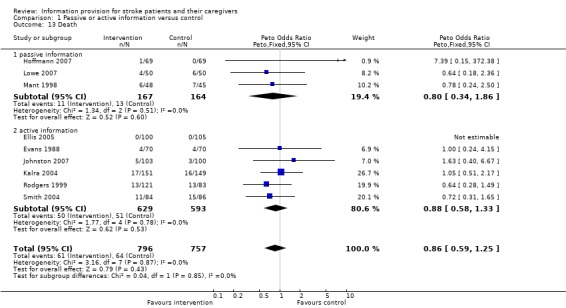

Death

Mortality data were available for 1553 participants from nine trials (Evans 1988; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Johnston 2007). There was no significant difference in mortality between the intervention and control groups (OR 0.86 95% CI 0.59 to1.25, P = 0.43) (Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 13 Death.

Subgroup analysis

Data were available from three passive information and six active information trials. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of effect of passive information compared with active information (passive: OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.86; active: OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.58 to1.33, test for subgroup differences P > 0.9).

Carer outcomes

Knowledge

Six trials (Lomer 1987; Evans 1988; Pain 1990; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004) evaluated the effect of a passive information or active information intervention on carer knowledge.

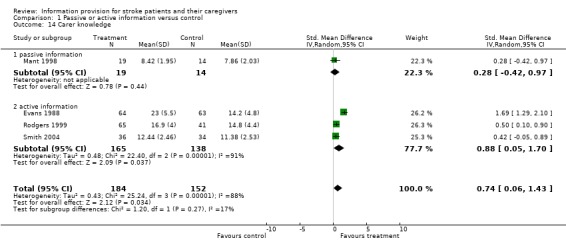

Carer knowledge

Data were available for 336 of 469 participants from four trials (Evans 1988; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004). There was a significant difference in carer knowledge between the intervention and control groups in favour of the intervention (SMD 0.74, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.43, P = 0.03) (Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 14 Carer knowledge.

Two small trials did not contribute data to the meta‐analysis (Lomer 1987; Pain 1990); Lomer 1987 found no significant difference in carer knowledge of stroke and no difference in the level of knowledge about the specific prognosis or help and benefits available. Pain 1990 reported that individualised information enhanced the carer's knowledge of how therapists had instructed the patient, although statistical significance was not reached.

Subgroup analysis

There were insufficient data to perform a sub‐group analysis.

Emotional outcomes

We conducted a meta‐analysis for the outcome of carer stress. As a variety of outcome measures were used to measure stress we only used dichotomous data in the analysis. A narrative summary is provided for the carer emotional outcomes of psychological distress, depression and burden.

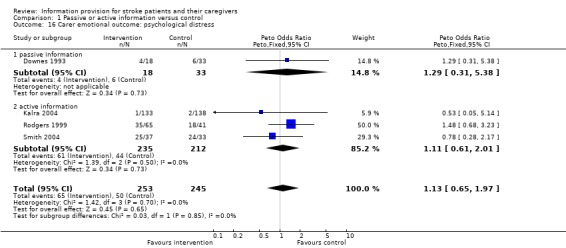

Psychological distress

Psychological distress in caregivers was measured by Downes 1993, Kalra 2004 and Johnston 2007 using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983). Rodgers 1999 and Smith 2004 used the General Health Questionnaire‐30 or the General Health Questionnaire‐28 (Goldberg 1979). we converted scale data to dichotomous data using the recommended cut‐off scores of 10/11 for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and 4/5 for the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg 1979; Zigmond 1983).

Suitable data were not available for Draper 2007 or Johnston 2007. Draper 2007 reported no significant difference in carer stress scores at final follow‐up (three months). Johnston 2007 reported baseline stress data for carers utilising the anxiety sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Mean (SD): Intervention 7.64 (4.89), control 7.08 (4.01) and no significant effect of group by time interaction on total Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score.

Carer emotional outcome: Psycholgical distress

Dichotomous data were available for 498 of 643 participants from four trials (Downes 1993; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004). There was no significant difference in carer stress between the intervention and the control group (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.97, P = 0.65) (Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 16 Carer emotional outcome: psychological distress.

Subgroup analysis

There were insufficient data to perform a subgroup analysis.

Depression

Passive information studies

In the Downes 1993 trial, there was no significant difference in depression as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale between carers in the intervention group and the control group (mean depression score at six months (SD): intervention 5.8 (5.2), control 5.1 (3.2). Johnston 2007 reported baseline data for depression of carers, measured by the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Mean (SD): intervention 5.7 (4.3), control 4.8 (3.9) and reported no significant effect of group by time interaction on total Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score.

Active information studies

One trial (Kalra 2004) evaluated this outcome. Carers in the intervention group were significantly less depressed as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale than carers in the control group (median depression score at one year (IQR): intervention 2 (1 to 3), control 3 (2 to 5); P < 0.0001).

Burden

Passive information studies

In the one trial that evaluated this outcome (Mant 1998) there was no evidence of an effect of passive information on carer burden.

Active information studies

Two trials evaluated this outcome. In the study by Kalra 2004 caregiver burden was significantly reduced in carers in the intervention group compared with the control group at both three months and one year (median score at 12 months (IQR): intervention 32 (27 to 41), control 41 (36 to 50); P = 0.0001). In Draper 2007 there were no significant differences in pre to post‐treatment scores for either the intervention or wait control group.

Social Activities

Passive information studies

No trials evaluated this outcome.

Active information studies

There was no significant difference in carer social activities in the two trials (Kalra 2004; Draper 2007) that evaluated this outcome.

Perceived health status and quality of life

Passive information studies

From the one study (Mant 1998) that evaluated this outcome there is no evidence of an effect of passive information on carer perceived health and quality of life.

Active information studies

Three trials measured this outcome (Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Larson 2005). The largest of these (Kalra 2004) reported that carers in the intervention group had a higher quality of life as measured by the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EuroQol Group 1990) than controls at both three months and one year (median score (IQR) at one year: intervention 80 (70 to 90), control 70 (60 to 80); P < 0.0001). In Rodgers 1999 there were no significant differences between carers in the intervention and the control groups on any of the domains of the SF36 except social functioning. This was significantly higher for carers in the control group (intervention group: mean 66.7 ± 29.8 SD; control group; mean 78.1 ± 27.4 SD; difference between means: 95% CI 11.3; 0.09 to 22.7; P = 0.04). This may be a chance finding due to multiple testing and the authors suggest that it should be interpreted with caution. In the trial by Larson 2005, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups over time.

Satisfaction

Five trials (Pain 1990; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004) evaluated carer satisfaction. Of these, three trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004) measured carer satisfaction using the Pound scale (Pound 1993) or a modified version of this scale. Meta‐analyses were performed for two questions considered to be of most relevance to the review: (1) satisfaction with information about recovery and rehabilitation; and (2) satisfaction with information about allowances and services. The remaining studies (Pain 1990; Kalra 2004) both evaluated aspects of carer satisfaction using a bespoke questionnaire and are not included in the meta‐analyses.

Carer satisfaction with information about recovery and rehabilitation

Data were available for 165 of 273 participants from two trials (Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004). There was no significant difference in satisfaction with information about recovery and rehabilitation (OR 1.78, 95% CI 0.88 to 3.60, P = 0.11) (Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 19 Carer satisfaction with information about recovery and rehabilitation.

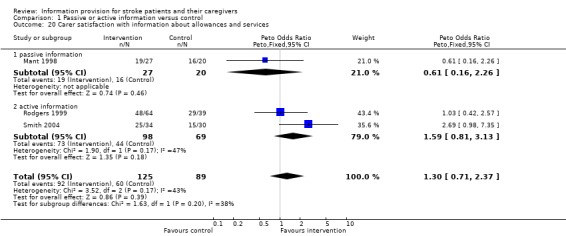

Carer satisfaction with information about allowances and services

Data were available for 214 of 322 participants from three trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004) for one question only: there was no significant difference in satisfaction between the groups (OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.71 to 2.37, P = 0.39) (Analysis 1.20).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Passive or active information versus control, Outcome 20 Carer satisfaction with information about allowances and services.

Subgroup analysis

There were insufficient data to perform a subgroup analysis.

Resource outcomes

Cost to health and social services

Passive information studies

No trials evaluated this outcome.

Active information studies

Only one study (Kalra 2004) evaluated resource use. Total health and social care costs over one year for patients whose carers received training (intervention) were significantly lower (MD ‐£4043 ($7249; EUR 6072), 95% CI to ‐£1595 to £6544). The cost differences were largely due to differences in length of hospital stay.

Discussion

This review has explored the effectiveness of information provision for stroke patients and their carers as a process of care aimed at improving stroke recovery. In order to summarise effectively the available evidence on the core concept of information provision, we categorised the studies according to the nature of the intervention using two categories: passive and active. Our intention was to differentiate between interventions where participation was largely passive with no subsequent systematic follow‐up or reinforcement procedure, and those in which there was active participation with a subsequent agreed plan for clarification and reinforcement. This classification was developed, agreed, and adopted prior to results synthesis.

We performed meta‐analyses for the outcomes of knowledge, mood and death, and for selected satisfaction questions. We carried out a qualitative analysis for all other outcomes. We performed meta‐analyses for the outcomes of patient anxiety and depression using both the reported mean and standard deviation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores and dichotomised data. An advantage of using dichotomised data is that it may provide more clinically meaningful results as it relates to 'cases' of depression and anxiety. However, it has been argued that collapsing ordinal stroke trial data in this way can result in a loss of discrimination between groups such that significant treatment effects are missed (OAST 2007).

It is worthy of comment that we undertook extensive searches for the update of this review, we reviewed over 20,000 titles, yet only four new studies are included. This reflects a lack of precision of the search strategies but may also be a reflection on research progress. We excluded 73 studies, many of which evaluated a complex intervention of which information provision and education are components. Information provision is acknowledged as a key component of stroke service delivery, provision of leaflets is not effective and it would seem that new multi‐faceted ways of addressing the information needs of patients and their carers are being developed and evaluated.

Summary of main results

We have identified a total of 21 trials involving 2289 patients and 1290 carer participants. We found some statistically significant but clinically small benefits supporting the general concept that information provision after stroke might improve outcomes. There was evidence of benefit in relation to improved patient and carer knowledge, some aspects of patient‐reported satisfaction and for depression scores in patients. Additionally, we found some evidence that interventions using active information provision may be more effective than passive information for the clinically important outcomes of patient depression and anxiety symptoms. However, as we saw no effect with the dichotomous endpoints of anxiety or depression, effects may be small. We found no evidence that information interventions are associated with improvements in activity limitation, participation or changes in service use.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All included studies were relevant to the review question. There was extensive variation in the content and delivery format of the interventions. This appears to reflect the diversity of interventions provided within clinical practice. Whilst there were sufficient data to address the primary outcomes and the majority of secondary outcomes for this review, there were limited studies to address social activities in carers or resource outcomes. Current practice on information provision after stroke varies nationally and internationally. Our review identified studies from seven countries, thus drawing conclusions on overall applicability of findings internationally is limited.

Quality of the evidence

There was considerable variation in the interventions evaluated and the 21 included trials were of variable quality. Clearly concealed randomisation was achieved in only 10 trials (Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Kalra 2004; Smith 2004; Ellis 2005; Larson 2005; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007; O'Connell 2009). The rate of attrition was over 20% in five trials (Downes 1993; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; O'Connell 2009). In several trials the sample size was small: less than 75 participants in eight trials (Pain 1990; Downes 1993; Banet 1997; Frank 2000; Johnson 2000; Draper 2007; Maasland 2007; Chinchai 2010).

Our evaluation of the effect on passive or active information provision on the outcome of stroke knowledge was limited by a lack of a consistently‐used measure. Knowledge of stroke was assessed in nine of the 21 studies reviewed (Lomer 1987; Evans 1988; Pain 1990; Mant 1998; Rodgers 1999; Smith 2004; Hoffmann 2007; Lowe 2007; Maasland 2007) but as each study had used a different questionnaire, combining the results in a meta‐analysis was problematic. Our initial intention was to perform a meta‐analysis using dichotomised data (knowledge improved or not improved). However, this was not feasible as in some trials knowledge was measured on one occasion only. We therefore combined the data using the SMD wherein the MDs in outcome between the groups being studied are standardised to account for differences in scoring methods. A disadvantage with this method is that interpretation of the clinical relevance of the treatment effect is difficult as estimated effect sizes serve only as a qualitative measure of the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis (de Beurs 1999). The results should therefore be treated with some caution. In addition, for the majority of the bespoke questionnaires used to measure knowledge there was limited information available about the reliability of the questions they contained.

Potential biases in the review process

Our search strategy was comprehensive and as we were able to identify a number of unpublished studies, publication bias is unlikely. Study selection, data collection and analysis were undertaken by two people, with a third person or consensus meeting used to resolve differences. As a result we are confident of limited bias in the review process for this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The positive effects of information on knowledge and depression demonstrated in this review are supported by the findings of reviews of patient education interventions in other conditions. In a meta‐analysis, Brown reported that diabetes education had a moderate to large effect on improving patient knowledge (Brown 1990). A systematic review of education for adults with rheumatoid arthritis showed a small effect on depression (Riemsma 2003). In accord with our review, an overview of systematic reviews of educational interventions for healthcare professionals reported that passive approaches were generally ineffective and unlikely to result in changes in professionals' behaviour, whereas educational approaches involving active learning were more likely to be effective (Grimshaw 2001). A systematic review of education programmes for patients with diabetic kidney disease found education programmes have beneficial effects on improving patients' knowledge of diabetes and some self‐management behavioural changes (Li 2011). A meta‐analysis of patient teaching strategies showed that the greatest effect size was associated with reinforcement, independent study, and the use of multiple strategies (Theis 1995).

Future direction

This review has demonstrated some positive effects of information provision on patient and carer knowledge, aspects of satisfaction and depression. However, the effects, although statistically significant, were clinically small and more effective information provision strategies after stroke need to be developed. The results of the review suggest that a strategy based on an active, rather than passive intervention approach should be adopted. This is perhaps unsurprising as stroke is a complex condition with wide‐ranging effects and probably requires a more profound approach to promote recovery than can be achieved by the provision of passive information alone. The specific components of the active information provision (i.e. involving recipients, planned follow‐up or reinforcement), which resulted in modest beneficial effects on some outcomes, requires further investigation. Future work should focus on the further development of a generalisable active information intervention that could be robustly evaluated in a large multicentre study.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is evidence to support the routine provision of information to stroke patients and their families. Providing information has been shown to improve knowledge of stroke, increase some aspects of patient satisfaction, and reduce patient depression scores. However, the reduction in depression score (as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) was small and may not be clinically significant. There is currently no evidence that providing information is effective in improving other patient and carer outcomes. Although the best way to provide information is still not clear, the results of the review suggest that strategies that actively involve patients and carers and include planned follow‐up for clarification and reinforcement should be used in routine practice.

Implications for research.

Future work should focus on the further development of a generalisable intervention which could be robustly evaluated in a large multicentre study. The evaluation of interventions is currently limited by the lack of a widely recognised measure of stroke knowledge. Attention should be given to given to the design, development and evaluation of a stroke knowledge questionnaire. Consideration should be given to the most appropriate outcome domains for this type of intervention.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 July 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The results and the conclusions for this update are the same as for the previous version of the review. |

| 30 December 2011 | New search has been performed | This review update has added four new trials (Johnston 2007; Chiu 2008; O'Connell 2009; Chinchai 2010).The review now includes 21 trials involving 2289 patient and 1290 carer participants. Additional data have been added for analysis for the patient outcome for death. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. Additional text added to the 'Acknowledgements' section and a new 'External sources of support' included. |

Acknowledgements

Northern and Yorkshire NHS Executive Research and Development Directorate funded the original review. This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding stream (Grant Reference Number RP‐PG‐0606‐1128 ). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We would like to thank the authors who provided additional information and data: H Rodgers, H Pain, R Evans, J Mant, L Lorenc, J Johnson, V Morrison, L Kalra, R Hartke, IW Miller, S Jian, D Lowe, T Hoffmann, L Kalra, G Ellis, Dongbo Fu, E Maasland, B Draper, B O'Connell and M Johnston. We also wish to thank Deirdre Andre (University of Leeds) who undertook the search strategies and Tom Crocker and Seline Ozer for assisting with reviewing the papers. We are also grateful for the ongoing support of Brenda Thomas and Hazel Fraser from the Cochrane Stroke Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane search strategy