Abstract

Background

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by high levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity that are present before the age of seven years, seen in a range of situations, inconsistent with the child's developmental level and causing social or academic impairment. Parent training programmes are psychosocial interventions aimed at training parents in techniques to enable them to manage their children's challenging behaviour.

Objectives

To determine whether parent training interventions are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms and associated problems in children aged between five and eigtheen years with a diagnosis of ADHD, compared to controls with no parent training intervention.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases (for all available years until September 2010): CENTRAL (2010, Issue 3), MEDLINE (1950 to 10 September 2010), EMBASE (1980 to 2010 Week 36), CINAHL (1937 to 13 September 2010), PsycINFO (1806 to September Week 1 2010), Dissertation Abstracts International (14 September 2010) and the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (14 September 2010). We contacted experts in the field to ask for details of unpublished or ongoing research.

Selection criteria

Randomised (including quasi‐randomised) studies comparing parent training with no treatment, a waiting list or treatment as usual (adjunctive or otherwise). We included studies if ADHD was the main focus of the trial and participants were over five years old and had a clinical diagnosis of ADHD or hyperkinetic disorder that was made by a specialist using the operationalised diagnostic criteria of the DSM‐III/DSM‐IV or ICD‐10. We only included trials that reported at least one child outcome.

Data collection and analysis

Four authors were involved in screening abstracts and at least 2 authors looked independently at each one. We reviewed a total of 12,691 studies and assessed five as eligible for inclusion. We extracted data and assessed the risk of bias in the five included trials. Opportunities for meta‐analysis were limited and most data that we have reported are based on single studies.

Main results

We found five studies including 284 participants that met the inclusion criteria, all of which compared parent training with de facto treatment as usual (TAU). One study included a nondirective parent support group as a second control arm.

Four studies targeted children's behaviour problems and one assessed changes in parenting skills.

Of the four studies targeting children's behaviour, two focused on behaviour at home and two focused on behaviour at school. The two studies focusing on behaviour at home had different findings: one found no difference between parent training and treatment as usual, whilst the other reported statistically significant results for parent training versus control. The two studies of behaviour at school also had different findings: one study found no difference between groups, whilst the other reported positive results for parent training when ADHD was not comorbid with oppositional defiant disorder. In this latter study, outcomes were better for girls and for children on medication.

We assessed the risk of bias in most of the studies as unclear at best and often as high. Information on randomisation and allocation concealment did not appear in any study report. Inevitably, blinding of participants or personnel was impossible for this intervention; likewise, blinding of outcome assessors (who were most often the parents who had delivered the intervention) was impossible.

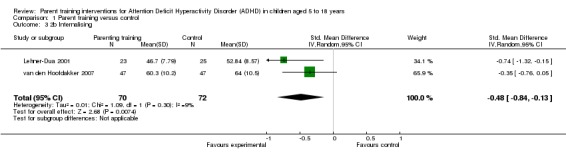

We were only able to conduct meta‐analysis for two outcomes: child 'externalising' behaviour (a measure of rulebreaking, oppositional behaviour or aggression) and child 'internalising' behaviour (for example, withdrawal and anxiety). Meta‐analysis of three studies (n = 190) providing data on externalising behaviour produced results that fell short of statistical significance (SMD ‐0.32; 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.18, I2 = 60%). A meta‐analysis of two studies (n = 142) for internalising behaviour gave significant results in the parent training groups (SMD ‐0.48; 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.13, I2 = 9%). Data from a third study likely to have contributed to this outcome were missing, and we have some concerns about selective outcome reporting bias.

Individual study results for child behaviour outcomes were mixed. Positive results on an inventory of child behaviour problems were reported for one small study (n = 24) with the caveat that results were only positive when parent training was delivered to individuals and not groups. In another study (n = 62), positive effects (once results were adjusted for demographic and baseline data) were reported for the intervention group on a social skills measure.

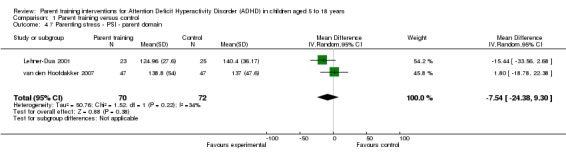

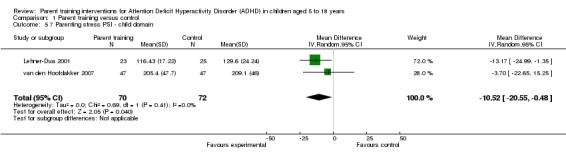

The study (n = 48) that assessed parenting skill changes compared parent training with a nondirective parent support group. Statistically significant improvements were reported for the parent training group. Two studies (n = 142) provided data on parent stress indices that were suitable for combining in a meta‐analysis. The results were significant for the 'child' domain (MD ‐10.52; 95% CI ‐20.55 to ‐0.48) but not the 'parent' domain (MD ‐7.54; 95% CI ‐24.38 to 9.30). Results for this outcome from a small study (n = 24) suggested a long‐term benefit for mothers who received the intervention at an individual level; in contrast, fathers benefited from short‐term group treatment. A fourth study reported change data for within group measures of parental stress and found significant benefits in only one of the two active parent training group arms (P ≤ 0.01).

No study reported data for academic achievement, adverse events or parental understanding of ADHD.

Authors' conclusions

Parent training may have a positive effect on the behaviour of children with ADHD. It may also reduce parental stress and enhance parental confidence. However, the poor methodological quality of the included studies increases the risk of bias in the results. Data concerning ADHD‐specific behaviour are ambiguous. For many important outcomes, including school achievement and adverse effects, data are lacking.

Evidence from this review is not strong enough to form a basis for clinical practice guidelines. Future research should ensure better reporting of the study procedures and results.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Male; Parenting; Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity; Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/psychology; Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/rehabilitation; Child Behavior Disorders; Child Behavior Disorders/psychology; Child Behavior Disorders/rehabilitation; Parents; Parents/education; Parents/psychology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stress, Psychological; Stress, Psychological/therapy

Parent training for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder. For a child to be diagnosed with ADHD, adults such as parents, carers, healthcare workers or teachers must have noticed higher levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity in the child before the age of seven years compared to children of similar age. The inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity must be observed in a range of situations, for a substantial period of time and cause impairment to the child’s learning or social development. Parent training programmes aim to equip parents with techniques to manage their child's 'difficult' or ADHD‐related behaviour (that is their inattention and hyperactivity‐impulsivity).

We found five randomised controlled studies that met our inclusion criteria. Four set out to improve children's general behaviour and one focused specifically on how parents could help their children make friends. All studies were small and their quality varied. Results from these studies were somewhat encouraging as far as parental stress and general child behaviour were concerned, but were uncertain with regard to other important outcomes including ADHD‐related behaviour. No study provided data on the key outcomes of achievement in school, harmful effects or parent knowledge of ADHD. There was no evidence to say whether parent training is better delivered in groups or individually.

The evidence we found was limited in terms of the size of the trials and in their quality, and therefore we do not think it can be used as the basis for guidelines of treatment of ADHD in clinics or schools. We believe more research is needed and that it should ensure better reporting of the study procedures and results.

Background

Description of the condition

Definition of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and its prevalence

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by high levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity that are present before seven years of age. These are seen in a range of situations, are inconsistent with the developmental level of the child and are associated with impairment in social or academic development (APA 1994). In the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) (WHO 1992), hyperkinetic disorder (HKD) is similar to ADHD but the criteria are more restrictive. In this review we used the term ADHD to include HKD, although technically HKD defines a more severe subgroup of ADHD (WHO 1992; APA 1994).

Prevalence estimates for ADHD vary considerably and depend on the characteristics of the population, sampling methods and the nature of the assessment (Jadad 1999a; Faraone 2003; Sciutto 2007). In a UK survey of 10,438 children aged five to 15 years, Ford 2003 found that 3.62% of boys and 0.85% of girls had a diagnosis of ADHD. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA conducted a survey of 102,353 parents with children aged four to 17 years and found a lifetime childhood diagnosis of 7.8% (2.5 times as many boys as girls) of whom 4.3% had received medication as treatment (CDC 2005). A review of 50 prevalence studies (including 20 US and 30 non‐US sample populations) suggested that the prevalence is similar in US and non‐US populations (Faraone 2003). However, the 'administrative' prevalence, that is the frequency of diagnosis in practice, seems to highlight a cultural difference between US and European clinicians as this ratio is estimated to be as high as 20:1 (Santosh 2005).

Comorbidity between ADHD and conduct problems is high. In the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey, 27% of those with conduct disorder (CD) and 26% of those with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) also qualified for a diagnosis of ADHD, and more than 50% of those with ADHD had a comorbid behaviour disorder (Ford 2003).

Early conduct problems appear to precede antisocial behaviour in later life. Farrington 1995 estimated that it is possible to predict over half of future recidivist delinquents based on their aggressive behaviour and a family's ineffective child rearing practices.The precise relationship between conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder and ADHD, especially the mechanism of development of antisocial behaviour in children with ADHD, is not, however, fully understood.

Aetiology

It is thought that genetic and environmental risk factors interact to cause ADHD rather than operate in isolation (Pliszka 2007; NICE 2008). The genetic contribution to observable phenotypic ADHD traits has been estimated as being up to 76% (Faraone 2005). No large single gene effect has been identified but the DRD4 and DRD5 genes appear to be involved (Li 2006) and a specific haplotype of the dopamine transporter gene has also been associated with the combined‐type ADHD (Asherson 2007). Findings by Williams 2010 indicated an increased rate of chromosomal deletions and duplications in children with ADHD compared to those without ADHD, suggesting further evidence of genetic influence in ADHD development. Controversial and inaccurate press reporting of this study highlights the need for clarity in communication of complex scientific work by journalists (Jones 2010; McFadden 2010).

Possible environmental factors include maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, heroin use in pregnancy, foetal hypoxia and perinatal exposure to toxins, injury and zinc deficiency (NICE 2008).

Issues regarding diagnosis

The diagnosis of ADHD has stimulated considerable debate and sometimes strong and conflicting views (Jadad 1999b). Inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity are normal traits in children, especially young children. There is no reliable test to confirm diagnostic validity, so diagnoses depend on clinical judgment. Consensus among experts in the field (Barkley 2002a) might exist but diagnoses may be open to bias. The use of operationalised diagnostic criteria, such as the DSM‐IV (APA 1994) or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), may reduce such bias. Professional and national bodies that are concerned about the importance of thorough and accurate ADHD diagnoses have issued guidelines to encourage good practice (American Academy of Pediatrics 2001; SIGN 2009; Pliszka 2007; NICE 2008).

Preschool diagnosis of ADHD is particularly problematic because few data on preschool diagnostic practice exist (Sonuga‐Barke 2003a). Lahey 2004 demonstrated that many four to six year olds continue to meet ADHD diagnostic criteria three years on; however factors such as parental expectations might influence the assessment of the severity of the condition and the extent of impairment it causes. Even where particular symptom levels are judged to be out of the normal range for that age, this might be transitory and reflect normal step‐wise or non‐linear competency development (Sonuga‐Barke 2003a). It is a complex process to establish 'caseness' (meeting the criteria for ADHD) where high levels of inattention and hyperactivity exist in a preschool child. The unusual extent of these traits and their association with impairment in the particular child must be demonstrated in order to meet DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria (APA 1994). Because it is uncertain that this can be done in a systematic and precise way, it has been suggested that making consistent diagnostic assessments in this age group could be problematic (Sonuga‐Barke 2003a).

Concerns about diagnostic validity led to the Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS) (Kollins 2006). Kollins 2006 demonstrated that when parent‐ and teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms are examined, DSM‐IV symptoms do not consistently act as meaningful discriminators in identifying ADHD and its subtypes; "it may be that other symptoms not routinely assessed in this age group are more saliently associated with ADHD in the preschool years" (Hardy 2007).

Our review requires that trial participants have a valid ADHD diagnosis. In view of the concerns about diagnostic validity of ADHD in preschool children 'at risk' of developing ADHD, we decided that this group fell outside the scope of our review. Without definite ADHD diagnoses, uncertainty would exist as to whether any behavioural and symptom changes with the intervention occurred in children truly at risk of developing ADHD, as opposed to those with opposition defiant disorder or conduct disorder or simply going through a particular developmental stage.

Treatment

Pharmacological

Over the past decade, a number of systematic reviews on ADHD treatment have been published (Miller 1998; Jadad 1999a; NICE 2000; SIGN 2009; NICE 2006b; NICE 2008). They conclude that stimulant treatments are relatively safe and effective (at least in the short term) for managing the ADHD core symptoms, which are excessive inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Atomoxetine, a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor, has also been found to be effective (Michelson 2001; NICE 2006b; Cheng 2007). Professional guidelines recommend pharmacological treatments, with or without concomitant psychosocial interventions, after a comprehensive diagnostic assessment (American Academy of Pediatrics 2001; Taylor 2004; Pliszka 2007; NICE 2008). Whilst consistent treatment with stimulants is associated with maintenance of effectiveness, it is also associated with 'mild' suppression of growth (MTA 2004).

Adding psychological interventions to medication has not been demonstrated to improve outcomes significantly (Miller 1998; MTA 1999; Abikoff 2004). However, it has been argued that stimulants do not necessarily lead to long‐term benefits (Jensen 2007). Those children with more severe symptoms appear to do better with stimulants than with behavioural interventions (Santosh 2005) but subgroups of ADHD patients with comorbid disorders might respond differentially to pharmacological and psychological treatments (Jensen 2001).

Psychosocial

Over recent years there has been an increased focus on establishing an evidence base of effective psychosocial treatments in ADHD (Pelham 2008). In 1998, Pelham and colleagues reviewed relevant literature and concluded that “Behavioural Parent Training barely met criteria for well‐established treatment” but met criteria for “a probably efficacious treatment” (Pelham 1998). A decade later, Pelham et al updated this review suggesting that their findings extend the earlier review and demonstrate that behavioural interventions (including behavioural parent training, behavioural classroom management and intensive summer programme‐based peer interventions) “are supported as evidence‐based treatments for ADHD” (Pelham 2008).

Children diagnosed with ADHD or HKD often have multiple problems, including comorbid disorders such as anxiety, depression and oppositional defiant disorder, as well as relationship difficulties, so multimodal treatment appears to be appropriate (Wells 2000; Taylor 2004; NICE 2008). This might be why, for children with less severe symptoms, safety and user preference may lead to behavioural interventions may being used as a first choice, despite the small advantage of medication over psychological intereventions (Santosh 2005). There are many reasons for considering psychosocial interventions in ADHD, including uncertainity about the long‐term effectiveness of stimulants; minimal clinical benefits of medication; nonresponsiveness to medication; weak responsiveness to medication; intolerance to medication; clinical needs of younger children, and ethical and other objections to the use of medication (NICE 2008).

Description of the intervention

Parent training programmes are psychosocial interventions aimed at training parents in behavioural or cognitive behavioural techniques they can use to manage their children's challenging behaviour. The programmes vary in their style and content but are generally manual‐based and may involve discussion and the use of video and role play. One example is Webster‐Stratton's Incredible Years programme (Webster‐Stratton 1998). In addition to the behavioural or cognitive behavioural content fundamental to generic parent training programmes, ADHD‐focused parent training often includes psychoeducational components about ADHD and how its presence affects a child's functioning and behaviour (Pliszka 2007). The programmes are typically delivered to groups of parents and usually comprise 10 to 20 weekly sessions of one to two hours covering a range of areas that include the nature of ADHD, positive reinforcement skills (for example, attending carefully to appropriate behaviour and play, as well as how to ignore unwanted behaviour), reward systems, the use of 'time out', liaison with teachers and planning ahead to anticipate problems (Pliszka 2007).

How the intervention might work

The main aim of parent training, for children with conduct problems, is "to reduce children’s problem behaviour by strengthening parent management skills" (Hartman 2003). Parent training interventions are mainly based on behaviour management principles that arise from social‐learning theory. They are based on the theory that behaviour can be influenced by its antecedents and consequences and that parents can learn how to intervene with both of these. Parent training usually comprises structured programmes that are delivered in a standardised way by professionals trained in behaviour management theory and practice (Kazdin 1997; NICE 2006a).

More specifically, in families with children who have ADHD parent training may be aimed at improving the parents' understanding of ADHD or increasing their behaviour management skills, or both. Parents may also learn self‐management skills aimed at reducing stress and increasing resilience.

In people with ADHD, it is hypothesised that deficits in the brain's executive functioning might result in excessive impulsivity and an altered motivational state may cause delay aversion (Solanto 2001; Sonuga‐Barke 2003b). Hypothetically, to improve ADHD symptoms parent training could be designed to work on both of these areas, through cognitive work on self‐regulation and through motivational interventions focusing on improving delay tolerance (Sonuga‐Barke 2003b).

Why it is important to do this review

Longitudinal research suggests that hyperactivity, in particular, is a risk factor for future problems (Taylor 1996; Sourander 2005). Unfavourable long‐term outcomes include educational and occupational impairment (Weiss 1985; Mannuzza 1997), an increased risk of antisocial personality disorder and substance misuse (Mannuzza 1998; Rasmussen 2000) and an increased risk of "psychiatric diagnosis, persisting hyperactivity, violence and other conduct problems and social and peer problems" (Taylor 1996).

Problem behaviours are viewed in two broad dimensions. Externalising problems include conflict with others, aggression, rulebreaking and oppositional behaviour, whereas internalising problems are those where stress is directed against the self, such as anxiety, depression, somatic problems and social withdrawal (Sourander 2005). The National Survey of Health and Development, a 40‐year cohort study, followed up 3652 adolescents with externalising problems. It found that those with externalising behaviour problems are impaired in their health and social development in multiple ways, with considerable impact on themselves, their families and society throughout adult life (Coleman 2009).

Parent training can improve behaviour in children with conduct disorder (Kazdin 1997; NICE 2006a) and children with behaviour problems (Barlow 1997). There is also some support for the effectiveness of group‐based parenting programmes in improving the emotional and behavioural adjustment in children under the age of three years (Barlow 2010). Furthermore, it may be effective in children who have both conduct disorder and the ADHD core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity (Hartman 2003).

The economic cost of antisocial behaviour to society is considerable and cuts across multiple agencies. When costs were applied to data from the Inner London longitudinal study, it was reported that those with conduct disorder cost 10 times more than those without (Scott 2001b). Parent training programmes for conduct disorder are effective (Kazdin 1997; Scott 2001a; NICE 2006a; Hutchings 2007; Scott 2007) yet until relatively recently they attracted little funding. This was despite the fact that the effect size of these interventions is comparable to that of antidepressant medication in depressed adults (Scott 2007).

Although comorbidity exists between ADHD and conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, it is not clear that parent training in children with ADHD, with or without comorbid conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, is effective for reducing antisocial behaviour or ADHD symptoms. Although NICE recommend parent training as a treatment intervention in ADHD (NICE 2008), this recommendation is based on studies of children under 12 years with conduct disorder rather than with ADHD (NICE 2006a). They nonetheless recommend that clinical services provide all parents or carers of preschool children a parent training or education programme as first‐line treatment. They also suggest that parents or carers of school age children with moderate ADHD symptom impairment be offered parent training programmes and that school‐aged children be offered a group treatment programme involving cognitive behavioural therapy or social skills training, or both (NICE 2008).

Given the high comorbidity between ADHD and conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, it is understandable that NICE have made these recommendations but the relationship between parent training and ADHD needs to be examined in its own right. The mechanism for development of behaviour problems might be different for the two conditions.

Objectives

To determine whether parent training interventions are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms and associated problems (for example, disruptive behaviour disorders or specific impairments such as learning difficulties) in children and young people aged five to 18 years with ADHD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including quasi‐randomised trials where sequence generation was, for example, by birth date or alternate allocation, that contain at least one measure of ADHD‐related behaviour. As specified in the protocol, we did not include trials which did not report any outcome data on outcomes relating directly to the child's own behaviour or well being (ADHD‐related or not).

Types of participants

Children and young people aged five to 18 years (or with a mean age above five years) in whom the main problem was ADHD (or hyperkinetic disorder) diagnosed using DSM or ICD operationalised diagnostic criteria. The diagnoses must have been clinical diagnoses by specialists with or without the use of semi‐structured or structured interview instruments. Acceptable diagnoses included:

Attention‐Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (DSM III‐R, DSM‐IV) (APA 1987; APA 1994);

Attention Deficit Disorder (DSM III) (APA 1980);

Parents of these children were the recipients of the parent training intervention as defined below.

Types of interventions

Parent training programmes where the intervention was designed to train parents in behavioural or cognitive behavioural, or both, interventions to improve the management of their child's ADHD‐related difficulties. The term 'parent training' includes:

group‐based interventions;

interventions for individual parents, or for a couple;

the combination of individual or couple and group interventions; and

parents acting as the main mediators of the intervention with an additional component involving teacher(s) trained in behavioural management.

We did not include trials which did not report any outcome data on outcomes relating directly to the child's own behaviour or well being (ADHD‐related or not). We also excluded trials where direct interventions with the children were used. This was to separate out the effect of parent training and the effect of the direct behavioural intervention with the child and eliminate the possibility of interaction between them.

However, we included trials in which drug treatments were used alongside parent training interventions (that is parent training plus medication versus medication alone) and we planned subgroup analysis of trials in which drug treatments were used.

We recorded details on all interventions permitted to the control group or indeed the intervention groups (that is existing drug or therapy regimes).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

* Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in home setting; for example, Conner's or SNAP questionnaires (Swanson 1983; Conners 1998a)

* Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in school setting; for example, Conner's Teacher Rating Scale (Conners 1998b)

* Changes in the child's general behaviour; for example, Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist (Achenbach 1991)

All primary outcomes related to participant children, not to parent outcomes (for example, reduction of parental stress), so studies with only parent outcomes were excluded. See also Potential biases in the review process.

Secondary outcomes

* Academic achievement of children as measured through school test results or general tests of language or development

*Adverse events (these could include emotional or psychological trauma of any kind, such as might be suffered by a parent with a history of physical abuse experiencing flashbacks in a discussion about physical chastisement, or parents for whom parent training causes an increase in anxiety or depression about their own skills)

*Changes in parenting skills; for example, The Parenting Clinical Observation Schedule (Hill 2008)

*Parental stress; for example, the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin 1995)

Parental understanding of ADHD; for example, ADHD Knowledge & Opinion Scale (Rostain 1993)

Outcome measures may be reports by a clinician, parent, teacher or trained investigator. Instruments used must be published in a peer‐reviewed journal following validation in the population, that is tested for validity in children or young people with ADHD and found to measure the change that they set out to measure.

Outcomes marked by asterisks indicate outcomes planned for inclusion within a 'Summary of findings' table (Schünemann 2008).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2010 Issue 3) (searched 14 September 2010).

MEDLINE: 1950 to current (searched 14 September 2010).

EMBASE: 1980 to 2010 Week 36 (searched 24 September 2010).

CINAHL: 1937 to current (searched 13 September 2010).

PsycINFO: 1806 to September week 1 2010 (searched 14 September 2010).

Dissertation Abstracts International, searched through Dissertation Express (14 September 2010).

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (searched 14 September 2010).

All search strategies used for this review appear in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3. Searches were run between 2002 and September 2010, during which time there were a number of changes to databases and platforms or database providers. For the most recent searches, the RCT filter in MEDLINE was updated to reflect the revised filter published in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2008).

No language filters were applied.

Searching other resources

We checked references in previous reviews and the bibliographies of included and excluded studies. We contacted authors and known experts to identify any additional or unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two researchers working in pairs undertook initial screening of abstracts and titles from the search independently to identify potential trials for inclusion. The first author (MZ) screened abstracts and titles at each of several searches conducted between 2002 and 2010, in tandem with either JD, HJ or AY. Studies were then independently assessed and selected for inclusion by the same pairs of review authors. We reached consensus by discussion. We made a flow chart of the process of trial selection in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Data extraction

Two of four authors (MZ, CT, HJ and JD) extracted data independently using data extraction sheets that had been previously piloted to check for reliability in extracting the relevant data. We stored and organised citations in ProCite bibliographic software.

Data collection

When more than two treatment arms were included in the same trial, we described all arms.

We collected the following data for all trial arms.

Descriptive data, including participant demographics (age, gender, baseline measures of school achievement, social and economic status).

Intervention characteristics (including delivery, duration and within‐intervention variability).

Other interventions received (including delivery and duration).

Outcome measures listed above.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool (Higgins 2008a; Higgins 2008b). Each study was assessed in relation to the six domains listed below.

Ratings given were: low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias.

Sequence generation

Description: the method used to generate the allocation sequence is described in sufficient detail so as to assess whether it should have produced comparable groups. The review authors' judgment: was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment

Description: the method used to conceal allocation sequence is described in sufficient detail to assess whether intervention schedules could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment. The review authors' judgment: was allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding

Description: any measures used to blind participants, personnel and outcome assessors are described so as to assess knowledge of any group as to which intervention a given participant might have received. The review authors' judgment: was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data

Description: when studies did not report intention‐to‐treat analyses, we made attempts to obtain missing data by contacting primary investigators. We extracted and reported data on attrition and exclusions as well the numbers involved (compared with total randomised), reasons for attrition/exclusion where reported or obtained from investigators, and any re‐inclusions in analyses performed by review authors. Review authors' judgment: were incomplete data dealt with adequately by the review authors? (See also Dealing with missing data.)

Selective outcome reporting

Description: attempts were made to assess the possibility of selective outcome reporting by investigators, including searching for trial protocols via registers. The review authors' judgment was based on the question: are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Validity and reliability of outcome measures used

Description: were the outcome measures standardised and validated for the population?

Other sources of bias

Description: was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

During data extraction, we identified potential 'contamination' effects between participants in different arms of a study as an additional risk of bias (see Characteristics of included studies below).

Measures of treatment effect

Only limited meta‐analysis was possible in this review. The methods and choices we made regarding measures of treatment effect and other issues pertinent to meta‐analysis can be viewed in Appendix 4 for binary and categorical data as no such data were identified in studies included within this review.

Continuous data

When continuous outcomes were measured using the same scale across studies, we calculated an overall mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). When the same continuous outcome was measured differently across studies, we calculated an overall standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. We calculated SMDs using Hedges g.

Unit of analysis issues

See Appendix 4.

Dealing with missing data

Where necessary, we contacted the corresponding author of a study to supply any unreported data. We planned to contact authors to obtain outcomes for any studies in which only per protocol analysis had been undertaken but, in the event, some authors undertook intention‐to‐treat analysis (for example, van den Hoofdakker 2007) and for others the number of dropouts was low, so overall this protocol decision was felt to be unnecessary for the current version of this review.

There was only one trial for which we sought additional outcome data (Fallone 1998). This was because numerical data for nonsignificant outcomes or numerical data for the whole sample (as compared with the subset of participants who attended more than 50% of parent training sessions) were absent from the text of the trial report. Our repeated attempts to make contact with this author between 2007 and 2011 were unsuccessful.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the extent of heterogeneity using the three methods suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2008): visual inspection of forest plots, the Chi2 statistic (increasing the level of significance to 0.10 to avoid underestimating heterogeneity) and using the I2 statistic, which describes the "percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance)" (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). It is advised that the thresholds of the I2 statistic might be misleading and the following guide is offered:

0% to 40% might not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity.

We bore in mind that the "importance of the observed value of I2 depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (for example, P value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2)" (Higgins 2008a). Clinical heterogeneity is discussed in the Results, Overall completeness and applicability of evidence and Authors' conclusions.

Assessment of reporting biases

As studies were few and opportunities for meta‐analysis fewer within this review, our plans for funnel plots and related methods were not feasible but we have archived them for future updates (Appendix 4).

As planned in our protocol, we attempted to address the issue of selective outcome reporting by seeking out the protocols of the included studies (within trial registries, conference proceedings etc) and by internal evidence within the published studies.

Data synthesis

Outcome data

Where sufficient clinical and methodological homogeneity existed between trials, we pooled results. We remained mindful of the dangers of interpreting findings of single or even multiple studies in the absence of meta‐analysis. Where meta‐analysis was not possible, for example where outcomes measured different domains such as 'ADHD core symptoms' and 'educational achievement', we provided the reasons and reported investigators’ findings narratively.

Review Manager 5.0 (RevMan 2008) was used to conduct meta‐analysis where feasible. We calculated overall effects using inverse variance methods (we planned to undertake both fixed‐effect and random‐effects model meta‐analyses and report data accordingly). We anticipated that included studies would yield heterogeneous data because of diagnostic variability in ADHD and differences in the parent training models used by different researchers, and we were correct in our assumptions.

Types of analyses

See Appendix 4.

Multiple arms

All relevant outcomes for all eligible trial arms were reported in the review.

When two or more eligible intervention groups were compared to an eligible control, the review authors considered (as planned in the protocol) combining data for interventions provided each met all inclusion criteria and did not involve unacceptable adjunct treatments, for example direct work with children. We used the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008c) to combine data from the two 'active treatment' arms of the three‐arm trial conducted by Fallone 1998 (parent training versus parent training and self‐management versus control).

At protocol stage we planned the following: "If a single eligible intervention group is compared to multiple eligible control groups, 'no‐treatment' controls will be chosen over other groups for comparison and inclusion in meta‐analyses (Lipsey 2001). For studies that do not have no‐treatment condition, the most appropriate eligible alternative will be chosen (see list of comparisons, above)". This decision led us to accept the study by Lehner‐Dua 2001 as we judged her parent support group to be synonymous with an 'attentional control'. We could not be certain of trials such as Lauth 2007, wherein the 'parent support' arm of the trial involved intensive discussion of themes pre‐chosen by intervention organisers to mirror those being taught in the more active parent training intervention arm.

Multiple measures

When a single study provided multiple measures of the same outcome (for example, two measures for ADHD symptoms), we planned at protocol stage to average the effects from the outcomes to arrive at a single effect for use in the meta‐analysis. In the event, this was not feasible in the one instance it occurred. We therefore reported separate subscales of the ADDES‐HOME scale (Hyperactivity and Inattentiveness) in the one trial using these measures (Fallone 1998). These scales measure different aspects of ADHD symptomatology and it was therefore inappropriate to combine them in a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not identify enough trials to conduct any subgroup analyses. Plans for assessment of statistical heterogeneity remain in Appendix 4. Clinical heterogeneity is discussed in Results; Overall completeness and applicability of evidence and Authors' conclusions.

Sensitivity analysis

See Appendix 4.

Qualitative data

We planned to report qualitative data from the included studies to better understand the delivery of interventions, uptake by participants and context; however we did not identify any such data reported in relation to studies included within this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We ran searches six times in the period during which the review was developed: four times after publication of the original 2001 protocol (by Jo Abbott in July 2002; Eileen Brunt in June 2004; Jo Abbott in November 2006; and Lynn Turner in May 2008) and twice after the publication of the revised 2009 protocol (by Jo Abbott in May 2009; Jo Abbott and Margaret Anderson in September 2010).

Results were vetted by different review author pairs at different times. These were: MZ and JD for searches up to 2006; MZ and HJ for searches in May 2008; MZ, HJ and AY for searches in 2009; and MZ and JD for searches in 2010. All decisions on eligibility were made by consensus within the author team.

Total numbers for searches are as follows.

Inception to 2004 ‐ 6671.

2004 to 2006 ‐ 1542.

2006 to 2008 ‐ 1579.

2008 to 2009 ‐ 1280.

2009 to 2010 ‐ 1889.

Minus duplicates that were automatically rejected by Procite software (but not counting overlaps between searches or duplicates later excluded manually), we identified 12,691 records through search strategies (see Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3). After screening of titles and abstracts, full texts of 112 papers were obtained over time. Five unique studies cited in six papers met our inclusion criteria. Many investigators were contacted to supply further data before decisions on inclusion could be made.

We excluded 74 unique studies (reported in 89 documents). See the table of Excluded studies for further details.

Included studies

Five studies published between 1993 and 2010 met the inclusion criteria (Blakemore 1993; Fallone 1998; Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Mikami 2010).

Location

Four of the five studies were conducted in North America. One study was conducted in Canada at The Learning Centre, Calgary, Canada (Blakemore 1993). Three studies were conducted in the USA: one in Memphis, Tennessee (Fallone 1998); one at the Hofstra University's Centre for Psychological Evaluation, New York (Lehner‐Dua 2001); and one at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia (Mikami 2010). The fifth study was conducted in the Netherlands at an outpatient clinic in Groningen (van den Hoofdakker 2007).

Design

All included studies were described by the investigators as randomised controlled trials. Four employed a stratified 'block' design (Blakemore 1993; Fallone 1998; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Mikami 2010) and the fifth (Lehner‐Dua 2001) randomised by individual participants.

Two studies involved three arms (Blakemore 1993; Fallone 1998); the remaining three were, for the purposes of this review, two‐armed intervention studies. Mikami 2010 did involve a third group but as it was a normative comparison group of children without a diagnosis of ADHD the study was treated within this review as a parallel group study.

Sample size

Overall, sample sizes were small, ranging from 24 participants (Blakemore 1993) to 96 (van den Hoofdakker 2007); the remaining studies comprised 54 (Fallone 1998), 48 (Lehner‐Dua 2001) and 62 (Mikami 2010) participants respectively.

Participants

To be included in this review, ADHD had to be the main focus of the trial and participants had to have a clinical diagnosis of ADHD made by a specialist using operationalised diagnostic criteria of the DSM‐IV, or its earlier versions, or a diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder using ICD‐10 (see under 'Inclusion criteria' below).

Participants included within the review ranged in age from four to 13 years old. Ranges, means and standard deviations, where provided, were as follows.

Blakemore 1993, six to 11 years (no other information supplied); Fallone 1998, five to 9 years (means: group 1 = 6.94 (SD = 1); group 2 = 6.56 (SD = 1.03); group 3 = 6.88 (SD = 1.36)); Lehner‐Dua 2001, six to 10 years (median = 8.0); Mikami 2010, six to 12 years (mean = 8.9); van den Hoofdakker 2007, four to 12 years (mean = 7.4, SD = 1.9).

All investigators with the exception of Blakemore 1993 supplied data on gender. They each reported a majority of male children (179 boys versus 65 girls across the four studies in which this demographic was reported).

Most children entered the studies on medication for ADHD symptoms (see below for further details, as reported in the individual studies). In general, where reported, participants had to be stablised on medication throughout the trial and this was established prior to randomisation. We also have to assume that medication, where used, was used in the same way across the intervention and control groups.

Inclusion criteria

Blakemore 1993 used DSM‐III‐R criteria for ADHD. The children had to demonstrate evidence of ADHD in a wide range of situations and the problems must have been evident before the age of six years. Fallone 1998 included participants who had to be diagnosed with ADHD using DSM‐IV criteria. Fallone also required a high level of maternal stress for inclusion in the training programme. Lehner‐Dua 2001 and van den Hoofdakker 2007 used DSM‐IV criteria. Mikami 2010 reported that DSM‐IV criteria were used (that is the proportion of those of Combined type (ADHD‐C) and Inattentive type (ADHD‐I) were reported). In this study, diagnoses were further reinforced and refined using the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI) (Gadow 1994) and confirmed by parental interview using the K‐SADS‐PL (Kaufman 1997).

van den Hoofdakker 2007 included participants who met DSM‐IV criteria for ADHD, had an IQ > 80 (full scale IQ of the WISC‐III‐R; for children under the age of six years the Full Scale IQ of the QWPPSI‐R) and were four to 12 years old. In addition, both parents (if present) had to be willing to participate in the behavioural parent training program. All participants in the trial were offered a comprehensive package of routine clinical care (RCC) including psychological treatment, pharmacological treatment and crisis management, where necessary, with the parent training component being offered as the only difference between the groups. The control group were also offered the intervention after a waitlist period, described as shorter than the one they might have faced had they not participated in the trial (it was hoped that this would improve retention in the control group).

Exclusion criteria

Blakemore 1993 excluded participants if there was evidence of a serious neurological difficulty in the child, evidence of a serious marital difficulty, or where the child met criteria for conduct disorder. Fallone 1998 excluded participants with "mental retardation" or pervasive developmental disorder. Lehner‐Dua 2001 did not specify any exclusion criteria. van den Hoofdakker 2007 did not specify any exclusion criteria, wishing for a 'naturalistic' intake, and its authors made clear that they thus anticipated (and found) a higher rate of comorbidities than other similar studies of children with ADHD. Mikami 2010 excluded children with pervasive developmental disorders, full scale IQ < 70 or verbal IQ < 75. No child could be receiving other psychosocial treatment for social and behavioural issues at the time of the study; however, educational interventions were allowed.

Intervention and control conditions

Blakemore 1993 allocated participants to two active experimental arms, one for group parent training and one for individual parent training, with a waitlist control group who were offered the group intervention at the end of the study. Fallone 1998 included two experimental arms, one for behavioural parent training alone, the other for behavioural parent training combined with self management, again with a waitlist control group offered intervention at the end of the study. Mikami 2010 included one intervention group that received 'Parental friendship coaching' (PFC), a programme that resembled other parent training programmes for the first two sessions then focused on developing social skills in children, versus a no treatment control group which at the close of the study received a summary session on the programme content of the intervention (PFC).

The duration of the parent training varied: 12 weekly, two hour sessions (Blakemore 1993, group treatment); 12 weekly, one hour sessions (Blakemore 1993, individual treatment); 12 two hour sessions spread over five months (van den Hoofdakker 2007); nine weekly, two hour sessions (Lehner‐Dua 2001); eight weekly, 50 minute sessions (Fallone 1998, parent training treatment); and eight weekly one and a half hour sessions (Fallone 1998, parent training and self management treatment). Mikami 2010's intervention, PFC, was delivered in eight group sessions of 90 minutes each.

Lehner‐Dua 2001 stood out in this review by offering a parent support group as a placebo control, whilst van den Hoofdakker 2007 explicitly offered 'treatment as usual' as control. We judged that, as in the other studies, all participants remained on existing pharmacological or other treatment regimes and no child appeared to have been denied such treatment; controls were quite similar in this respect.

Follow‐up

Blakemore 1993 had two follow‐up assessments at three and six months. No other study reported collecting data at later time points, or planning to do so, and this may be explained by waitlist conditions or financial constraints, or both.

Outcomes

Instruments used to measure primary and secondary outcomes within the included studies varied widely.

1. Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in home setting

The Conners' Parent Rating Scale (Conners 1970) was used by Blakemore 1993. Similarly, the ADHD Index subscale of the Conners' Parent Rating Scale‐Revised Short Form (CPRS‐R‐S) (Conners 2001) was used by van den Hoofdakker 2007. Fallone 1998 employed the Hyperactive‐Impulsive and the Inattentive scales of the ADDES‐Home (McCarney 1995) for this outcome. Lehner‐Dua 2001 used the Behaviour Assessment System for Children (BASC) (Reynolds 1998) to measure parents' perceptions of child behaviour.

2. Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in school setting

Fallone 1998 used the ADDES‐School for this outcome (McCarney 1995), which involves both a Hyperactive‐Impulsive and an Inattentive Scale.

3. Changes in the child's general behaviour

Externalising and Internalising subscales of the Dutch version of the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach 1991) were used by van den Hoofdakker 2007 and the Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist (Achenbach 1991) was also used by Blakemore 1993 and Fallone 1998 (who also used a total CBCL score). Investigators involved in Blakemore 1993 also used the Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) (Eyberg 1999).

Mikami 2010 used the teachers' version of the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) (Gresham 1990) and the Dishion Social Acceptance Scale (DSAS) (Dishion 2003). The latter measures the extent to which observers feel a child is liked and accepted or disliked and rejected by peers.

Mikami 2010 used the parents' version of the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) (Gresham 1990).

4. Academic achievement measured through school test results

Academic achievement was not measured in any study included within this review.

5. Adverse events

No study reported adverse events in any way.

6. Changes in parenting skills

Lehner‐Dua 2001 used the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) (Johnston 1989) for this outcome.

7. Parental stress

Blakemore 1993, Lehner‐Dua 2001 and van den Hoofdakker 2007 all used versions of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1986) or short form (PSI‐SF) (Abidin 1990) for this outcome; Fallone 1998 measured parental stress using the Revised Symptom Checklist (SCL‐90‐R) (Derogatis 1994).

8. Parental understanding of ADHD

No study included within this review measured this outcome specifically.

Measures in included studies that were not used in this review

A number of outcomes reported in the studies included in this review are not reported here, either because they did not fit the protocol for the review or they were from unpublished instruments, generally devised by the investigators of the studies themselves (for example, a structured interview with parents (Blakemore 1993)). In a US study primarily focused on assisting parents to help their children form social bonds (Mikami 2010), several outcome measures were unusable in our review including: the 'Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ) and Playdates Hosted', both cited in an unpublished manuscript (Frankel 2003); the 'Child Friendships at Follow‐up' questionnaire (global five point questionnaire completed by parent, devised by investigators); the Parental Behaviour in Playgroup (socialising, facilitation and corrective feedback, videotapes coded by blinded observers on a scale of 10); the Parental Behaviour in Parent‐child Interaction (coded as above using a Likert scale from zero to three).

Treatment fidelity

Parent training for ADHD is typically delivered following training of staff via a manualised treatment protocol. Amongst studies included within this review, only Fallone 1998 described efforts to ensure treatment fidelity across all sessions.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies for details of 74 excluded studies, data for which we found in 89 publications.

Many studies which appeared (by title or even abstract) to be of interest did not ultimately meet our inclusion criteria. Some studies were excluded for more than one reason. Primary reasons for exclusion are listed below.

Lack of random allocation or a control group

Randomised and quasi‐randomised studies were eligible for this review. Of the 68 intervention studies identified and inspected for this review, 64 were (at a minimum) controlled intervention studies.

Seven studies were excluded because participants were not randomly or quasi‐randomly allocated to intervention groups (Anastopoulos 1993; Bandsma 1997; Taylor 1998; Weinberg 1999; Ercan 2005; Salbach 2005; Gibbs 2008). In these studies, it was usually found (sometimes only after contact with investigators) that allocation was by self‐selection on the part of parents, or that groups had been formed by clinical severity alone (Bandsma 1997).

Four studies were excluded because, although they were intervention studies, they proved to have no control group at all (Pollard 1983; Danforth 1998; Arnold 2007; Hautmann 2009).

Fourteen studies included no eligible control group (Barkley 1992; Sanders 2000b; Barkley 2001; Montiel 2002; Corrin 2003; Hall 2003; Isler 2003; Corkum 2005; McGoey 2005; Fabiano 2006; Grimm 2006; Markie‐Dadds 2006; Lauth 2007; Cummings 2008). The latter group of studies generally compared active interventions only; in some cases they also failed to meet diagnostic criteria for children.

Direct intervention of therapist with child

Fourteen studies (Horn 1991; MTA 1999; Abikoff 2004; Chronis 2004; Springer 2004; Waschbusch 2005; Miranda 2006; Bogle 2007; Chacko 2007; Dubbs 2008; Guo 2008; Molina 2008; van der Oord 2008; Coughlin 2009) were excluded because their intervention directly involved the child.

Problems with diagnosis or diagnostic criteria

Sixteen studies were excluded because, although investigators may have described the children as having ADHD, there was no clear ADHD diagnosis made that met our inclusion criteria, or the children were too young for this review (O'Leary 1976; Dubey 1978; Pisterman 1989; Pisterman 1992a; Beyer 1994; Connell 1997; Barkley 2000; Sanders 2000a; Sonuga‐Barke 2001; Barkley 2002b; Bor 2002; Sonuga‐Barke 2004; Gustis 2007; Heriot 2008; Jones 2008; Larsson 2008). Readers interested in the results of studies that focus primarily on the young with subclinical behavioural problems may be interested in the results of another Cochrane review, when complete (Furlong 2010).

Six studies were excluded as the children had behavioural problems due to other conditions including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD) (Nixon 2001; Nixon 2003; Lavigne 2008; Scott 2010), pervasive developmental disorders (Aman 2010) or being 'gifted' (Morawska 2009).

Focus of the study

Two studies were excluded due to intervention type: Chronis 2006 because the intervention targeted maternal depression amongst mothers of children with ADHD, and was assessed as not meeting the inclusion criteria for parent training; and Wolraich 2005 because the intervention sought to improve communication between parents, teachers and clinicians rather than to manage child behaviour.

Two studies narrowly missed inclusion (Scott 2001a; Scahill 2006) because ADHD was not the main focus of the trial, which rendered data interpretation problematic. Scahill 2006 recruited children with tic disorders and disruptive behaviour from a specialised tic disorders clinic, and specifically excluded children with untreated ADHD. This yielded a subset of children with comorbid, medicated ADHD (investigators further responded to our request for subset data with the view that this sample was too small to analyse meaningfully (Scahill 2008)). In contrast, Scott 2001a took pains to exclude children diagnosed with the ICD‐10 diagnosis of 'hyperkinetic syndrome' precisely because he wished to exclude medicated children with ADHD from his study. We have recently learned from a personal communication that, despite the fact that the published paper does not refer to any child having a diagnosis of ADHD, a substantial proportion of participants did, posthoc, merit this diagnosis (Scott 2011) and that unpublished data for this subset exist. Yet these participants, given the exclusion criteria, were solely unmedicated children with ADHD. Thus we concluded that, in the absence of an underpinning focus on ADHD, a risk of bias (in that children with ADHD will have been excluded from both studies who would have been included in other included studies) might 'skew' the results of this review.

No child outcomes

Three studies (Odom 1996; Corkum 1999; Treacy 2005) were excluded because although the studies involved parents of children with ADHD, and sequence generation was adequate for the eligible intervention and control groups, no outcomes relating to the child's behaviour or well being (ADHD‐related or not) were reported. In these studies, outcomes typically included parental stress, parental knowledge of ADHD and willingness to medicate children or seek counselling.

Opinion pieces and review articles

Six studies (Ellis 2009; Fagan Rogers 2009; Hauth‐Charlier 2009; Reeves 2009; Schoppe‐Sullivan 2009; Baker‐Ericzen 2010) were excluded because they were found to be review articles, opinion pieces or other types of studies when obtained and inspected. For example, Schoppe‐Sullivan 2009, whilst tagged as a randomised controlled trial in MEDLINE, proved to be an observational study considering parents' own ADHD symptoms in relation to their parenting practices.

Risk of bias in included studies

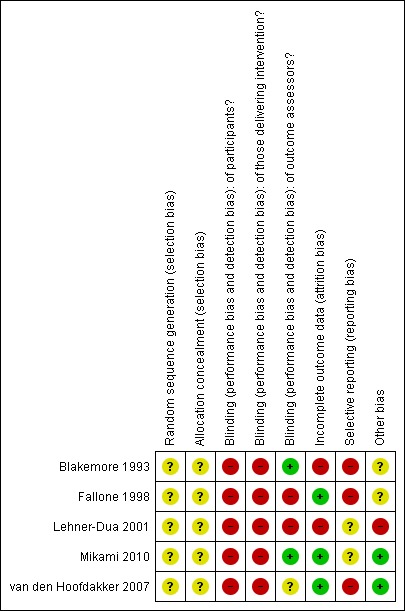

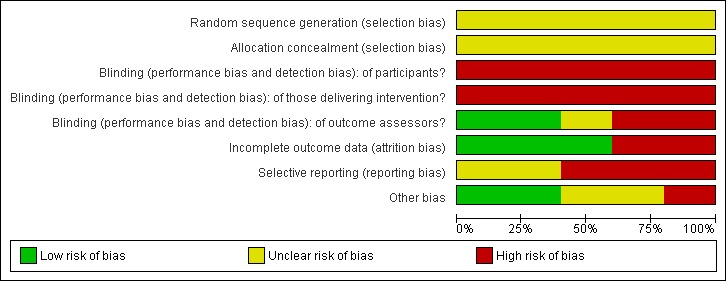

See also Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All included studies were described by investigators as randomised, and the majority as stratified or block designs (see above). No study included in this review described the precise method by which a sequence was generated or allocation concealed. Therefore, overall the risk of bias for this criterion is unclear.

Blinding

As is common with psychological interventions, especially where outcomes are self‐reported, there is inherent bias given the impossibility of blinding participants or those delivering interventions to treatment status. For this reason, despite the best intentions of researchers, the overall risk of bias in all studies is high. Where outcomes are not self‐reported, outcome assessors can and should be kept blind.

We rated two studies as having high risk of bias (Fallone 1998; Lehner‐Dua 2001); two as being unclear (van den Hoofdakker 2007; Mikami 2010); and one as being at low risk of bias (Blakemore 1993).

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies lost only a few participants. Two studies reported using intention‐to‐treat analysis (van den Hoofdakker 2007; Mikami 2010). Attrition was uneven in Lehner‐Dua 2001.

Selective reporting

Original trial protocols were not available for any study in this review. Data for all reasonable outcomes for each study appear to have been reported. Remaining concerns include the fact that Blakemore 1993 only ever published preliminary results, in graph format without tables, and van den Hoofdakker 2007 collected data for both parents but only "analyzed the data from the mothers" (p.266) (van den Hoofdakker 2007). Fallone 1998 clearly collected data for all outcomes but did not report them all numerically, even in additional tables, concentrating mostly on the presentation of significant results. The overall judgment for included studies remains as unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Chief sources of other bias include issues of potential contamination in the study conducted by Lehner‐Dua 2001, where the primary investigator led both parent training and control conditions.

Effects of interventions

In the protocol for this review, the following comparisons were planned:

parent training versus a no treatment or waitlist control;

parent training versus routine care (treatment as usual);

parent training versus unstructured group parent support meetings.

As described above, given that child participants in all studies remained on pre‐existing treatment regimes and that control groups did not differ substantially, results for all studies are reported together. Opportunities for meta‐analysis were, however, very limited due to issues of presentation of outcome data, so the majority of results are reported narratively.

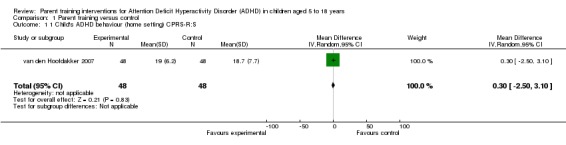

1. Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in home setting

The ADHD Index subscale of the Conners' Parent Rating Scale‐Revised Short Form (CPRS‐R‐S) (Conners 2001) was used by van den Hoofdakker 2007. Within this 27 item scale, a higher number indicates greater psychopathology. Fallone 1998 employed the ADDES‐Home (McCarney 1995) to measure this construct, wherein a higher value indicates less severity. Pooling results for van den Hoofdakker 2007 and Fallone 1998 for this outcome was not possible, even using standardised mean difference and compensating for opposing directions of scales, as the ADDES scale is divided into two subscales (the Hyperactive‐Impulsive scale and the ADDES‐Inattentive scale) (McCarney 1995) but is not a combined measure. In addition, van den Hoofdakker 2007 reported endpoint data and Fallone 1998 reported only change data in full (means and standard deviations). Means without standard deviations (SD) are supplied, but not for the entire sample: we calculated whole sample SDs using standard errors of within‐group differences and report all data narratively below.

Narrative reports of results

Using the CPRS, van den Hoofdakker 2007 (n = 62) reported that, with respect to the ADHD Index of the CPRS, both groups (intervention plus routine clinical care (RCC) and RCC alone) improved, but that adjunctive parent training was not significantly better than with RCC alone. Results for the intervention group were: 19.0 (SD = 6.2) versus 18.7 (SD = 7.7) for the RCC control group.

On the ADDES‐Home's Hyperactive‐Impulsive scale, Fallone 1998 reported that both the parent training (PT) and enhanced parent training treatment (PT and self‐management (SM)) groups did rate significantly better than control (mean of PT alone = 7.50 (calculated SD = 1.64); mean of PT and SM group = 7.46 (calculated SD = 1.64); mean of control group = 5.69 (calculated SD = 1.84)).

On the ADDES‐Home's Inattentive scale, Fallone 1998 reported that both the parent training and enhanced parent training treatment groups did significantly better than control (mean of PT alone = 6.43 (calculated SD = 1.44); mean of PT and SM group = 7.31 (calculated SD = 1.96); mean of control group = 4.50 (calculated SD = 1.92)).

2. Change in the child's ADHD symptom‐related behaviour in school setting

No meta‐analysis was possible for this outcome as the two studies that assessed it (Fallone 1998; Mikami 2010) reported it in very different ways. Fallone used both Achenbach 1991's Child Behaviour Checklist's Teacher Report Form (TRF) and McCarney 1995's ADDES‐School measures. The TRF includes a Total Problems and a Total Externalizing and Total Internalizing scale (see note below), whereas the ADDES‐School comprises Inattentive and Hyperactive‐Impulsive scales. Fallone 1998 reported no numerical data for either of these instruments. Mikami 2010 reported results for the Teacher Questionnaire Measures of child social functioning (SSRS) and the teacher‐assessed Dishion Social Acceptance Scale (DSAS) (Dishion 2003) to consider children's progress in this domain. Mikami reported data in the form of means and SDs.

Narrative reports of results of included studies

Fallone reported only that "analysis of teacher ratings failed to identify significant differences between treatment and control subjects from baseline to post‐treatment. No significant changes on TRF and ADDES‐School scales were detected for any group" (p 37) (Fallone 1998). No data were reported in tables. As above, the review authors await information that will assist in reporting numerical data for this outcome.

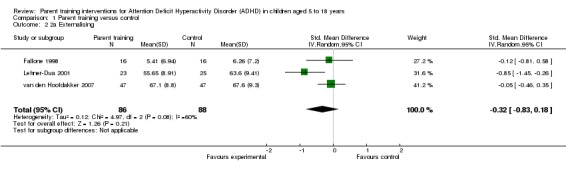

3. Changes in the child's general behaviour

As described above, problem behaviours are viewed in two broad dimensions. Externalising problems include conflict with others, whereas internalising problems reflect dealing with stress internally. Externalizing and Internalizing subscales of the Child Behaviour Checklist were used by van den Hoofdakker 2007 (Dutch version) (Achenbach 1991) and by Fallone 1998 (Achenbach 1986). Externalizing and Internalizing subscales of the Behaviour Assessment System for Children (BASC) (Reynolds 1998) were used by Lehner‐Dua 2001.

The Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) (Eyberg 1999) was used by investigators in Blakemore 1993.

Mikami 2010 (a study where the focus was on children's social development) used the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) (Gresham 1990).

Results from meta‐analysis

Externalising

Meta‐analysis of three studies (Fallone 1998; Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007) (n = 190) yielded results in favour of the intervention group, but fall short of significance (SMD ‐0.32; 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.18, I2 = 60%).

Internalising

Results from meta‐analysis of two studies (Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007) (n= 142) yielded significant results in favour of the intervention group (SMD ‐0.48; 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.13, I2 = 9%).

Fallone 1998 appeared to have collected, but not reported, numerical data for the Internalising subscale of the CBCL instrument.

Narrative reports of results of included studies

The Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) (Eyberg 1999) was used by Blakemore 1993 (n = 24). Means are not supplied in the text or any table but they are supplied separately for mothers and fathers plotted on a graph that is difficult to interpret. No SDs are given. The investigators' own interpretation is as follows: "According to this measure (Figure 2) there were significant declines for mothers in the frequency of problem behaviours for both individual and group treatment relative to controls, although the effects were stronger for individual [treatment]. Data for fathers indicated a significant decline in the frequency of problem behaviours only for individual treatment relative to controls" (p 81). The investigators add that "effects for group treatment in fathers were not possible to evaluate because of large pre‐treatment differences relative to both individual and control treatments". Investigators summarised their data as follows: "there appears to be stronger treatment effects for individual than group treatment and stronger effects for mothers than fathers" and that the former persist at follow‐up and that the latter do not.

Investigators from the Mikami 2010 study (n = 62) reported results for the SSRS for the intervention group (parental friendship coaching (PFC)) as 90.86 (SD = 14.68) versus 83.87 (SD = 16.28) in the control group. After accounting for "demographic covariates and baseline parent reports on the SSRS", there was a "between small and medium" effect size between intervention and control, and no interactions appeared to exist between treatment and sex, medication or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) status.

Investigators from Mikami 2010 (n = 62) (wherein the target of the intervention was children's social development) reported results for the SSRS (Teacher Questionnaire) for the intervention group (PFC) as 92.38 (SD = 12.90) versus 86.45 (SD = 10.92) in the control group. The investigators reported that this difference was not significant; however, there was an interaction between treatment and ODD status. This indicated that the effect on teacher reports of child social skills may have been generally positive for the children without ODD who had received PFC (beta = 0.16; P = ‐ 0.04) but was not significant for those with ODD (beta = ‐0.09; P = 0.47).

Investigators from Mikami 2010 (n = 62) also reported results for the DSAS like or accept (teacher assessed) for the intervention group (PFC) as 3.45 (SD = 1.35) versus 2.62 (SD = 1.15) in the control group. This outcome referred to the number of classroom peers who "like and accept" the child. Effect sizes were "between small and medium" and there were no interactions for this dependent variable. Results for the DSAS dislike or reject (teacher assessed) for the intervention group (PFC) were reported as 1.66 (SD = 0.81) versus 2.21 (SD = 1.11) in the control group. Effect sizes were "between small and medium" and interactions appeared to include a positive effect of PFC for girls relative to boys and for medicated youth relative to nonmedicated youth.

4. Academic achievement measured through school test results

No study reported on this outcome.

5. Adverse events

No study reported adverse events in any way.

6. Changes in parenting skills

Lehner‐Dua 2001 used the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) (Johnston 1989) to assess whether the parent training programme "would significantly increase parents' sense of competence in comparison to a support group". The investigator reported significant improvement in both groups on the PSOC. The parent training group improved from a score of 58.48 (SD = 12.53) to 70.17 (SD = 8.99), whilst the parent support group changed from 55.2 (SD = 13.24) to 59.08 (SD = 11.63) (P < 0.01) (MD 11.09; 95% CI 5.23 to 16.95). The author commented that because of the absence of a 'no contact' group, "the mechanisms for these meaningful changes cannot be ascertained".

7. Parental stress

Blakemore 1993, Lehner‐Dua 2001 and van den Hoofdakker 2007 all used a variant of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1986) or short form (PSI‐SF) (Abidin 1990) for this outcome; Fallone 1998 measured parental stress using the Revised Symptom Checklist (SCL‐90‐R) (Derogatis 1994).

Results from meta‐analysis

Meta‐analysis involving two studies (Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007) (combined n = 142) gave results for both the Parent and Child Domains of the PSI instrument (Child Domain Stress is linked to the parent's perception of the child's behaviour and Parent Domain Stress is a more general measure).

Results of meta‐analysis of data from these two studies indicated no statistically significant difference between parent training and control for the Parent Domain (PD) of the PSI (MD ‐7.54; 95% CI ‐24.38 to 9.30, I2 = 34%). Results for the PSI Child Domain (CD), however, were significant in favour of the intervention group (MD ‐10.52; 95% CI ‐20.55 to ‐0.48, I2 = 0%).

Narrative results

Investigators from the Blakemore 1993 study (n = 24) also reported PSI total score data in the form of means plotted on a graph or figure, as described above, with no numerical data in tables or text. They reported, however, "an advantage for parents participating in the individual therapy program" and that these gains were durable and even increased at follow‐up, at least for mothers. Subscales of the PSI including the Child Domain Stress and Parent Domain Stress were also reported as improving significantly for mothers but not for fathers. In contrast, their data suggested that fathers benefit more from group treatment, but that these benefits did not last.

Fallone 1998 reported change data for within group results for parental stress using a global measure for this outcome, the SCL‐90‐R (Derogatis 1994). Means without SDs were reported for endpoint data; we calculated the SDs by using within‐group standard errors, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2008). Results were: mean = 47.86 (SD = 8.23) for the parent training only group; for the parent training plus self management group, mean = 53.31 (SD = 6.78); for the control group, mean = 55.56 (SD = 5.08). Fallone reported these differences to be significant in favour of the parent training group (P ≤ 0.01) but not for any other group.

8. Parental understanding of ADHD

No study included in this review measured this outcome specifically.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Studies were few, small and disparate in focus. Opportunities for meta‐analysis were limited due to issues of presentation of outcome data and we reported the majority of results narratively.

Change in the child's ADHD‐symptom‐related behaviour in the home setting

Two studies addressed this. The findings of the largest study in this review (van den Hoofdakker 2007) suggested that both groups improved but parent training plus routine clinical care was not significantly better than routine clinical care alone. Fallone 1998 reported that both parent training and enhanced parent training were significantly better than a waitlist control.

Change in the child's ADHD‐symptom‐related behaviour in the school setting

Two studies reported on this outcome. One yielded no numerical data, stating only that the results were not significant (Fallone 1998). They attributed this to the fact that most children in the study were taking medication that was most effective during school hours. The second study (Mikami 2010) focused mainly on social interaction outcomes for the children. Mikami 2010 concluded that in this domain (Teacher Questionnaire) parent training was only significantly better where ODD was not comorbid with ADHD.

Mikami 2010 also reported teacher assessments of whether children with ADHD were liked and accepted by their peers. Effect sizes were between "small and medium" for both outcomes. There was more effect in girls relative to boys and in medicated relative to nonmedicated participants.

Changes in the child's general behaviour

A meta‐analysis of three studies (Fallone 1998; Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007) (n = 190) favours parent training. However, the effect did not reach significance (SMD ‐0.27; 95% CI ‐0.57 to 0.03, I2 = 60%). Results from meta‐analysis of two studies (Lehner‐Dua 2001; van den Hoofdakker 2007) (n = 142) yields significant results in favour of the parent training (SMD ‐0.48; 95% CI ‐0.81 to ‐0.14, I2 = 9%) for internalising behaviour. We had concerns about selective outcome reporting for a third study (Fallone 1998), which could have contributed data to this outcome but did not.

The Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) (Eyberg 1999) was used by Blakemore 1993 (n = 24). Investigators summarise their data as follows: "There appears to be stronger treatment effects for individual than group treatment and stronger effects for mothers than fathers" and the former persisted at follow‐up and the latter did not.