Abstract

Background

Hemorrhoidectomy is a frequently performed surgical procedure and associated with postprocedural pain. The use of the Ligasure could result in a decreased incidence of pain as coagulation with high frequency currency and active feedback control over the power output has minimal thermal spread and limited tissue charring.

Objectives

To compare patient tolerance focussing on pain following Ligasure and conventional hemorrhoidectomy in patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids.

Search methods

A multi‐database (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and CINAHL) systematic search was conducted. Key journals were handsearched. There was no restriction on language.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials comparing hemorroidectomy using the Ligasure‐technique with conventional diathermy techniques for symptomatic hemorrhoids in adult patients were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently extracted data, assessed trial quality and resolved discrepancies together with a third party. Odd Ratios were generated for dichotomous variables. Weight Mean Differences were used for analysing continuous variables. Only random effects models were used. Heterogeneity was explored by sensitvity analysis.

Main results

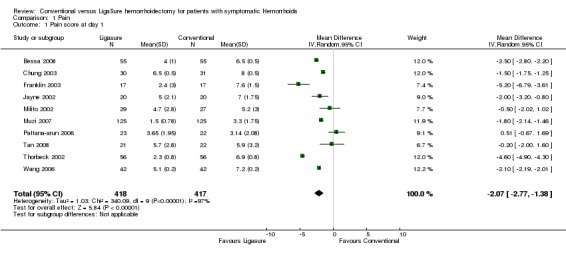

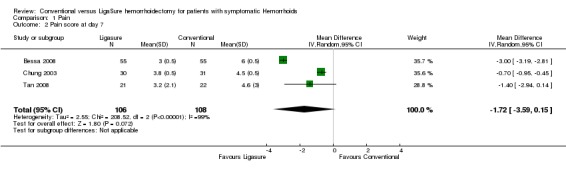

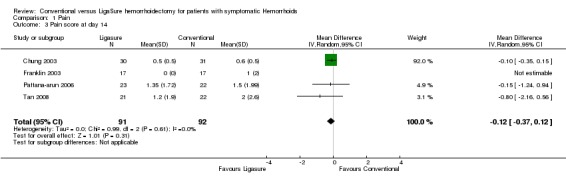

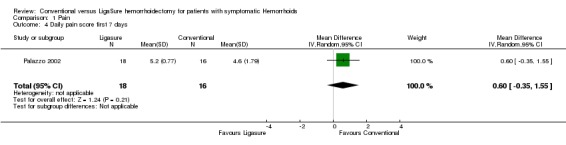

Twelve studies with 1142 patients met the inclusion criteria. The pain score at the first day following surgery was significantly less in the Ligasure group (10 studies, 835 patients, WMD ‐2.07 CI ‐2.77 to ‐1.38). Most outcomes concerning analgesics used (7 studies) and pain scores up to 7 days (5 studies) favoured the Ligasure‐technique. The benefit was diminished at day 14 (VAS pain score, 4 studies, 183 patients, WMD ‐0.12 CI ‐0.37 to 0.12). The conventional technique took significantly longer to complete (11 trials, 9.15 minutes, CI 3.21 to 15.09). There was no relevant difference in postoperative complications, symptoms of recurrent bleeding or incontinence at final follow‐up. Hospital stay was similar for both groups (6 reports, 525 patients, WMD ‐0.19 CI ‐0.63 to 0.24). Patients treated with the Ligasure‐technique returned to work significantly earlier (4 studies, 451 patients, 4.88 days, CI 2.18 to 7.59). Sensitivity analysis on high quality studies, fixed effects models, open or closed conventional techniques revealed no clinical relevant different results.

Authors' conclusions

Since the usage of the Ligasure technique results in significantly less immediate postoperative pain after hemoroidectomy without any adverse effect on postoperative complications, convalescence and incontinence‐rate, this technique is superior in terms of patient tolerance. Although there was a tendency for equal efficacy, more evaluation of the long‐term risk of recurrent hemorrhoidal disease is required.

Plain language summary

The ligasure technique is superior in terms of patient tolerance, but long term risk of recurrence of hemorrhoids needs to be evaluated.

Hemorrhoidectomy is a frequently performed surgical procedure. The excisional technique is regarded to be the first choice for grade III and IV or recurrent hemorrhoids. As conventional hemorrhoidectomy is associated with postprocedural pain, modifications have been proposed to diminish this complication. An example is the use of the Ligasure as coagulation between the forceps only with high frequency currency and active feedback control over the power output has minimal thermal spread and limited tissue charring. This could result in a decreased incidence of postoperative pain.

Background

A considerable part of the adult population is affected by hemorrhoids. When this benign anorectal disorder becomes symptomatic, investigation should follow to rule out other diagnoses. Based on the combination of complaints and the results of clinical examination, hemorrhoidal disease can be classified into four stages. They range from first‐degree bleeding to fourth‐degree protruding hemorrhoids that can not be reduced. Along goes the treatment from medical therapy to operative intervention (Madoff 2004). This review focussed on the hemorrhoids requiring surgical intervention. Two commonly used excisional procedures are the open Milligan‐Morgan (Milligan 1937) and the closed Ferguson (Ferguson 1971) technique. In most trials comparing both techniques, similar results have been reported (Madoff 2004). Although hemorrhoidectomy is currently regarded as the most effective therapy, it is associated with significantly more complications and pain than nonoperative treatment (MacRea 2002; Madoff 2004; Jayaraman 2006). To minimize the postoperative discomfort following conventional surgery, several alternatives to the conventional techniques have been developed such as for instance a circular stapling device. A beneficial effect on postoperative pain has been reported by several autors using this technique but in a cochrane review it was associated with a higher long‐term risk of recurrent hemorrhoidal disease and the appearance of rectal prolapses (Jayaraman 2006). Therefore, the authors concluded that at present the conventional excisional technique remains the standard treatment. The excision can be performed with a cold scalpel, diathermy, scissors, laser, ultrasonically activated scalpel or a bipolar electrothermal sealing device. The use of scissors or laser compared to diathermy provided no significant benefits (Madoff 2004; Pandini 2006). Conflicting results have been reported concerning the use of an ultrasonically activated scalpel (Ultracission TM) making it impossible to draw definitive conclusions in this respect (Madoff 2004). A bipolar electrothermal sealing device or Ligasure‐TM (Valleylab, Boulder, CO) was introduced in the field of hemorrhoidectomy. In contrast to diathermy or electrocautery, this device uses a very high frequency current providing hemostasis by denaturating collagen and elastin from the vessel wall and surrounding connective tissue. It is postulated that sealing of hemorroidal tissue in between the Ligasure‐forceps is achieved with minimal collateral thermal spread and limited tissue charring through use of active feedback control over the power output and could result in diminished post procedural pain as compared to conventional surgical techniques. The validity of this hypothesis is the subject of the present review.

Objectives

This review evaluated the results of randomized trials comparing conventional to Ligasure assisted hemorrhoidectomy. The primary goal was to ascertain whether the use of Ligasure results into less postprocedural pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published randomized controlled trials comparing Ligasure assisted to conventional hemorrhoidectomy were included. Length of follow‐up was not a selection criteria.

Types of participants

All patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids within the randomized setting were included.

Types of interventions

Eligible techniques for conventional hemorrhoidectomy were the open (e.g. Milligan‐Morgan) and the closed (e.g. Ferguson) technique. The dissection had to be with Ligasure in the studygroup and with diathermy in the control group.

Types of outcome measures

Pain measured with a visual analog scale or verbal numeric scale at the first postoperative day as well as the amount and number of patients using analgesics were the primary outcome measures addressed in this review. The operative variables, complications, incontinence and patient related outcome were considered as secondary outcome measures. Operative variables were operating time in minutes and blood loss in mililitres. Complications were postoperative bleeding, urinary retention, constipation, incomplete wound healing, anal fissure, anal stenosis and late minor bleeding. Late minor bleeding was regarded as recurrent disease. Incontinence was defined as any grade of incontinence at follow‐up. Patient related outcomes were length of hospital stay, return to work and satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

A comprehensive search of different electronic databases using a combination of free text and MESH (Medical Subject Heading) terms was undertaken to identify potential studies for inclusion in the review. The strategy in Medline is given:

1 controlled clinical trial.pt. 2 randomized controlled trial.pt. 3 randomized controlled trials/ 4 random allocation/ 5 double blind method/ 6 single blind method/ 7 or/1‐6 8 animals/ not (animals/ and human/) 9 7 not 8 10 clinical trial.pt. 11 exp clinical trials/ 12 random$.tw. 13 research design/ 14 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 15 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 16 factorial.tw. 17 (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 18 animals/ not (animals/ and human/) 19 or/10‐17 20 19 not 18 21 exp HEMORRHOIDS/ 22 (hemorrhoid$ or haemorrhoid$).mp. 23 piles.mp. 24 or/21‐23 25 exp surgical procedures, operative/ or exp ligation/ 26 diathermy.mp. or DIATHERMY/ 27 Milligan Morgan.mp. or Surgical/ 28 Ferguson.mp. or surgical/ 29 Digestive System Surgical Procedures/ or Milligan.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] 30 (haemorrhoidectom$ or hemorrhoidectom$).mp. 31 or/25‐30 32 ligasure.mp. 33 bipolar.mp. 34 electrothermal.mp. 35 device.mp. 36 33 and 34 and 35 37 32 or 36 38 9 and 20 and 24 and 31 and 37

The following electronic databases were searched in the same manner: Medline, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and CINAHL. There was no restriction on language. Principal authors were contacted if possible for further information related to the study and any other studies published and unpublished. All reference lists were searched for additional studies. Hand‐searches were performed on the following journals from 2000 and beyond: Annals of Surgery, British Journal of Surgery and Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. This search was conducted completely in 2008. An updated search in March 2011 encompassed the electronic databases only, and did not reveal any new trials to be included in this version.

Data collection and analysis

The identified trials were screened by two independent authors (SWN and IDH). Full text of the eligible studies were obtained and each reviewer independently assessed whether the studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Excluded studies were documented and the reasons for exclusion stated. Any difference in opinion was arbitrated by a third‐party (JDZ). The methodological quality of all studies eligible for the review was assessed independently. Each included trial was scrutinized for the following criteria: concealed randomization, technique of randomization, number of randomized patients, number of patients not randomized with explanation, exclusion of randomization, blinding of observer, blinding of outcome assessment, similarity between treatment and control group at entry, representativeness of patients, prospective data collection, documentation of dropouts, follow‐up, standardization of outcome assessment, and whether the intention‐to‐treat analysis was employed. Two investigators independently extracted the results of each trial on a standard data sheet. The data were cross‐checked. Where possible missing data was sought from the authors. The quality of included studied was assessed by using the modified Jadad score (Moher 1999), considering a score of four and more as high quality.

For statistical analysis RevMan Analysis software in Review Manager 5.1.1 was used. Odd Ratios were generated for dichotomous variables. Weight Mean Differences type IV were used for analysing continuous variables. Both were presented with a 95% confidence interval. If studies reported medians instead of means, the difference of medians was assumed to be equal to the difference of means. If no measure of dispersion was given, these data were tried to be obtained from the authors or retrieved out of the confidence interval or range. Where there were sufficient data, a summary statistic for each outcome was calculated. If data were insufficient for statistical analysis, observational results were presented. Where appropriate, a formal meta‐analysis was conducted with investigation of heterogeneity. Standard random effects model were used as the data resulted from surgical interventions from different centres. In case of considerable heterogeneity (test of inconsistency > 50%) a sensitivity analysis was performed for high quality studies (MJS>3), conventional open and closed techniques. These analyses were performed for six clinically relevant parameters: pain score at day 1, postoperative bleeding, urinary retention, anal stenosis, incontinence and hospital stay.

Results

Description of studies

A total of 12 RCTs were included (Altomare 2008; Bessa 2008; Chung 2003; Franklin 2003; Jayne 2002; Milito 2002; Muzi 2007; Palazzo 2002; Pattana‐arun 2006; Tan 2008; Thorbeck 2002; Wang 2006). In total 1142 patients were evaluated. Two reports provided additional information as they were follow‐up studies (Peters 2005; Lawes 2003). The characteristics of these trials are provided. Follow‐up periods ranged from 1 to 37 months. The majority of the papers described patients with grade III or IV hemorrhoids. Two papers did not specify the grade of hermorrhoids and used the definition of symptomatic prolapsed hemorrhoidal disease requiring hemorrhoidectomy (Milito 2002; Palazzo 2002). Further selection criteria as well the Ligasure‐technique were defined well in most cases. Five studies applied the closed (Ferguson, Loder and Phillips and Fansler) technique as conventional (Altomare 2008; Chung 2003; Franklin 2003; Pattana‐arun 2006; Wang 2006), the remaining applied the open Milligan‐Morgan technique. In all method sections the use of diathermy was noted, only in the study of Pattana‐arun the excision was by Metzenbaum scissors and bleeding stopped by electrocauterization (Pattana‐arun 2006).

Most trials assessed several different clinical outcomes with postoperative pain being the most common. Most used the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) in centimetres (zero, no pain to ten, worst possible pain). Palazzo et al. (Palazzo 2002) computed a median daily score out of VAS scores of 7 consecutive days. Pattana‐Arun et al. (Pattana‐arun 2006) used the Verbal Numeric Scale. Follow‐up was fully completed in most primary reports. In the trial of Muzi, reasons were provided and total follow‐up was 250 out of 284 patients (88%) (Muzi 2007). Two of the included trials were subsequently re‐published under different authors with long‐term follow up of the original patients in the trial. The original publication by Jayne et al. (Jayne 2002) was updated with long‐term data by Peters in 2005 for 30 of 40 patients (75 per cent)(Peters 2005). Similarly, the original data published by Palazzo et al. (Palazzo 2002) was updated by Lawes in 2004 for 30 out of 34 patients (88%) (Lawes 2003).

Risk of bias in included studies

The randomization assignment ranged from inadequate (Chung 2003; Thorbeck 2002) to adequate (Altomare 2008) whereas the sealed envelopes were not described opaque in any study. In most trials follow‐up was carried out by interview or postal questionnaire. In the study of Jayne et al. (Jayne 2002) a blinded surgeon assessed discharge and follow‐up was performed by blinded nurse practioners. An independent observer was used in three trials (Milito 2002; Muzi 2007; Wang 2006). In the trial conducted by Palazzo (Palazzo) patients were kept unaware of what procedure had been performed until the consignment of the research data two weeks postoperatively. Most studies scored four points on the Modified Jadad Score (MJS). Extremes were 1 point (Thorbeck 2002) and 5 points (Muzi 2007).

Effects of interventions

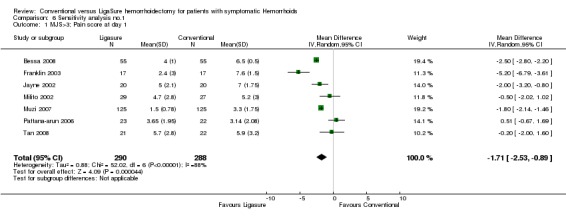

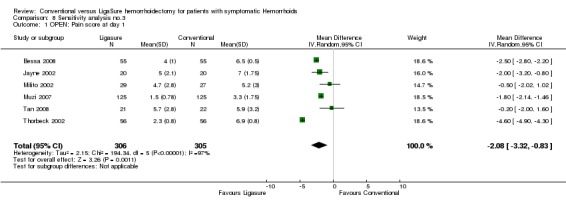

Pain The pain score at the first day following surgery was significantly less in the Ligasure group (10 studies, 835 patients, WMD ‐2.07 CI ‐2.77 to ‐1.38). Test for heterogenity was significant (Chi2=340, p<.001, I2 = 97%). The study wherein no significant difference was found in the mean daily pain score of seven consecutive days, reported a significant higher analgesic requirement in the conventional group. Most outcomes concerning analgesics used (7 studies) and pain scores up to 7 days (5 studies) favoured the Ligasure‐technique. The benefit was diminished at day 14 (VAS pain score, 4 studies, 183 patients, WMD ‐0.12 CI ‐0.37 to 0.12).

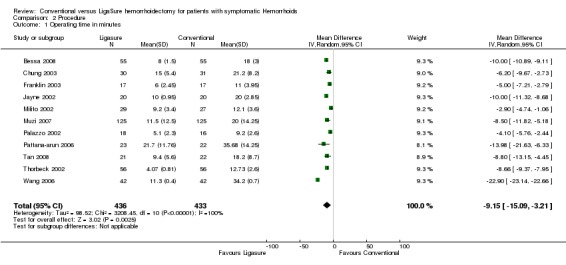

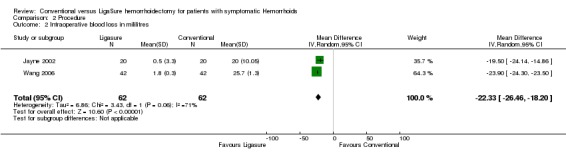

Operative variables The Ligasure technique was performed in significantly less time (11 trials, 9.15 minutes, CI 3.21 to 15.09). Intraoperative blood loss was more with the conventional technique (2 studies, 124 patients, WMD ‐22.33, CI ‐26.46 to ‐18.20).

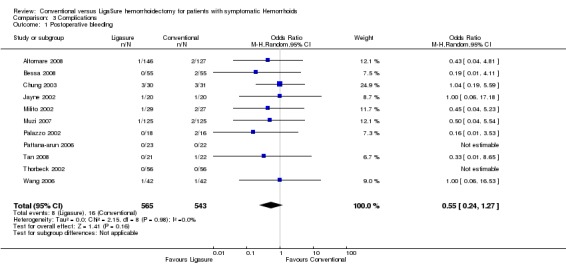

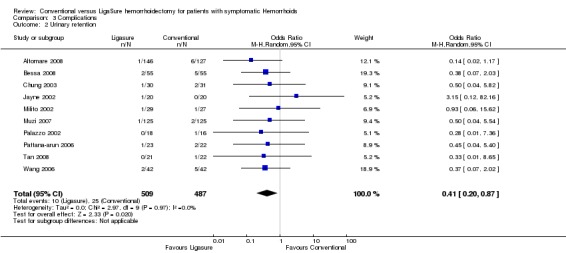

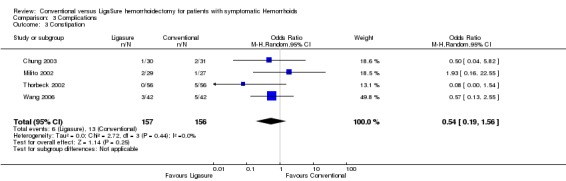

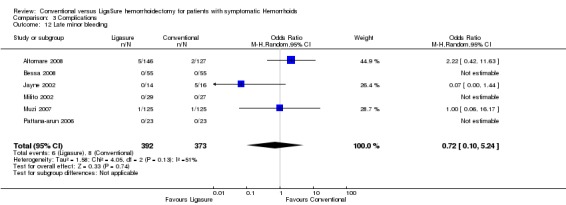

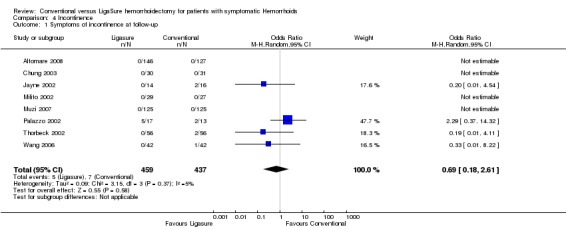

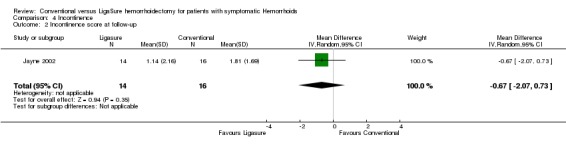

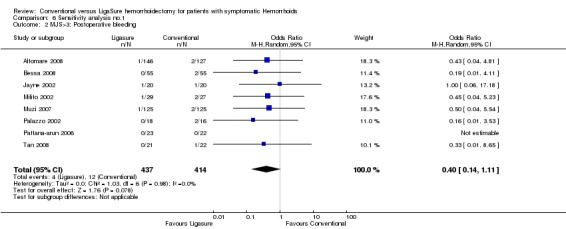

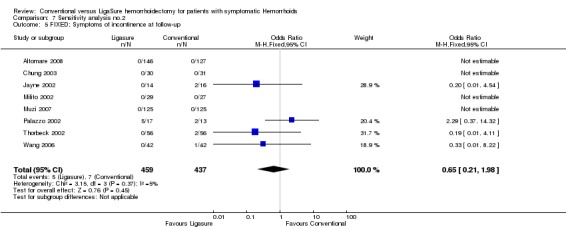

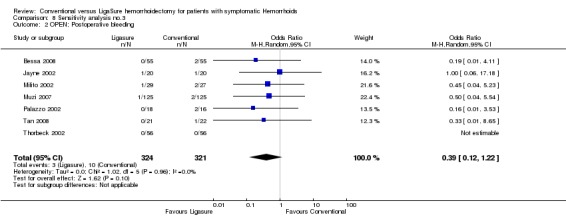

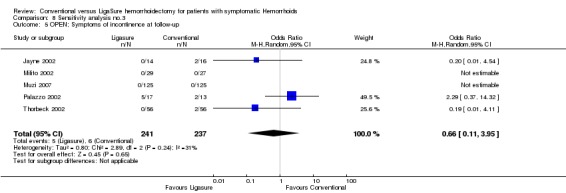

Complications Postoperative bleeding did not differ significantly between the techniques (11 studies, 1108 patients, OR 0.55, CI 0.24 to 1.27). There were non‐significant trends of less urinary retention, constipation, anal fissure and stenosis following the Ligasure procedure. A trend for delayed wound healing was seen in the conventional technique group, which was significant after 3 and 6 weeks (both 1 study) for wound dehiscence in days (2 studies). Late minor bleeding was reported for 6 versus 8 patients (6 studies, 765 patients, OR 0.72, CI 0.10 to 5.24. Symptoms of incontinence at final follow‐up was non significantly different (8 reports, 896 patients, OR 0.69 CI 0.18 to 2.61).

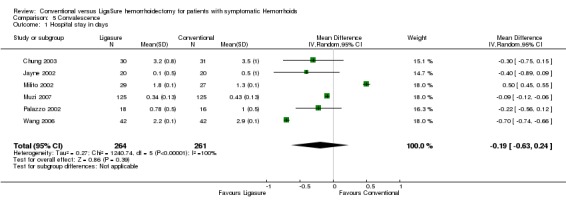

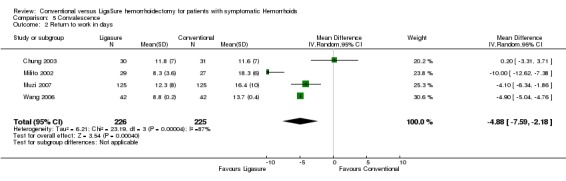

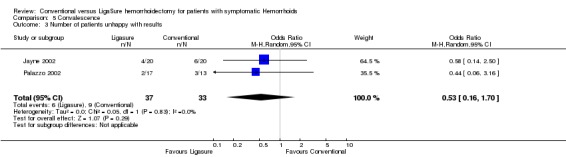

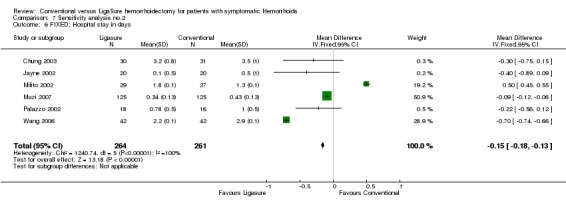

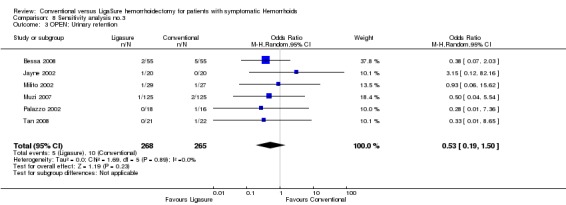

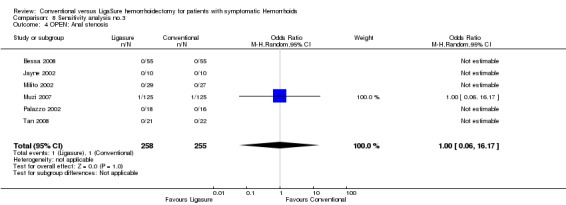

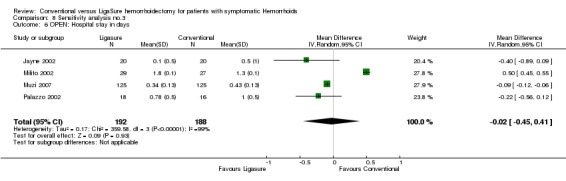

Patient related outcome Hospital stay was similar for both groups (results of 525 patients in 6 reports, WMD ‐0.19 CI ‐0.63 to 0.24). Patients treated with Ligasure returned to work significantly earlier (4 studies, 451 patients, WMD 4.9 days, CI 2.18 to 7.59). There was a non‐significant trend of more patients being unsatisfied with the results in the conventional group (2 studies, 70 patients, OR 0.53 CI 0.16 to 1.70). Heterogeneity For the results of pain at day 1 and 7, procedure time, wound dehiscence, hospital stay and return to work there was significant statistical heterogeneity. In other results it was not significant or not applicable at all. For the six predefined parameters, analysis of the high‐quality studies showed similar results with a reduction in estimated effect and heterogeneity. The use of fixed effects model had hardly any effect on the results. Analysis of the subgroup with open hemorrhoidectomy revealed an increase in the heterogeneity for incontinence, and analysis of the subgroup with the closed technique showed a chance to non significance in statistical heterogeneity for hospital stay.

Discussion

Pain following hemorrhoidectomy is a well known complication. Its aetiology is however less obvious. General factor such as patients' characteristics and anesthetic influences may play a role. As for the surgical components, the tissue damage and subsuquent inflammatory response cause nociception. An example of tissue damage is the thermal spread of diathermy used with hemorrhoidectomy. Avoiding or minimizing extended thermal injury might translate into decreased postoperative pain. It has been postulated that such minimal thermal injury can be achieved with the use of a bipolar electrothermal sealing device (Ligasure‐TM, Valleylab, Boulder, CO). In contrast to diathermy or electrocautery, this device uses a very high frequency current providing hemostasis by denaturating collagen and elastin from the vessel wall and surrounding connective tissue. The Ligasure has the potential to reduce thermal damage through use of active feedback control over the power output. Furthermore the head of the device is heat‐sink engineered to ensure a cool (below 45 degrees Celsius) surface. Histological studies and in situ thermal imaging has shown negligible evidence of thermal damage (Campbell 2003). For this reason the Ligasure‐technique has been used in hemorrhoidectomy. Reviewing the randomized controlled trials on this subject, this technique was related to less postoperative pain in comparison to conventional surgical techniques.

There are however some comments to be made on study size and design, pain assessment, different conventional techniques and other devices. Some trials included in this review had a relatively small number of patients. Follow‐up was sufficient for assessment of direct postoperative pain, however for long‐term outcome such as incontinence and complications, it was only sufficient in three trials (Lawes 2003; Muzi 2007; Peters 2005). Data on possible explanatory factors such as preoperative pain or co‐existing pain syndromes were not provided. Age, degree of hemorrhoids, duration of complaints, employment and the number of piles excised could influence the pain experience. These parameters weren't included in the meta analysis. In the majority of studies reporting these results however, there were no significant differences found. Exceptions are significantly more hemorrhoids treated with Ligasure in two trials (Pattana‐arun 2006, Tan 2008). The primary outcome of the visual analogue pain score at 1 day was only a one‐dimensional pain measurement. Pain disabilities or influences on quality of life were rarely assessed. In future studies on this subject a more comprehensive pain assessment could provide valuable additional information.

Another drawback are the different techniques used. The Milligan‐Morgan technique was applied in the majority, the closed technique was used with different alternatives. In the American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hemorrhoids four trials randomzing between open and closed technique were review (Madoff 2004). In three no difference in pain was found, one reported less pain following the open technique. In another RCT on this subject less pain was reported after the closed technique (You 2005). Based on these results, both open and closed techniques were initially considered to be equal in terms of postoperative pain in this review. The sort of technique was included in the sensitivity analysis.

Pain was the primary endpoint. The significant reduction after Ligasure at day 1 was 2.07 points on a 10‐point‐scale. This result was with a statistical significant heterogeneity. Pains scores in the first week as well as the amount of analgesics used was measured too infrequently to reach consistency or significance. All results showed however a trend for less pain following the Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy. Although this benefit seemed to be reduced two weeks after the procedure, the diminished direct postoperative pain is correlated with a lower risk for persisting postoperative pain (Kehlet 2006). Secondary endpoints were operative variables, complications and convalesence. Although the differences in operating time and blood loss were significant, the tests for heterogeneity were significant and 9 minutes and 22 mililiters reduction may be regarded clincally irrelevant. The lower incidence of complications favoured the Ligasure, however, most results were not significant different. The conventional technique was associated with longer hospital stay and patient's dissatisfaction. The difference in days to return to work, which favoured the Ligasure technique, was significant.

The heterogeneity was assessed. As the test for heterogeneity was significant for some results, a sensitivity analysis was performed on 6 predefined parameters. These parameters were regarded as clinicaly relevant: pain at day 1, postoperative bleeding, urinary retention, anal stenosis, symptoms of incontinence and hospital stay. The analysis of high quality studies (Modified Jadad Score > 3) showed a reduction in the significant difference and the extent of heterogeneity. For symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up there was an increase in difference favouring the ligasure technique. However the extent of heteogeneity increased as well (I2 from 5 to 44%). Subanalysis of the resuls after open and closed technique sowed similar results. The analysis of the other complications were mostly without significant hetereogeneity. In all subanalysis the parameter hospital stay was with a high I2 value. It is probably related to the different hospital's discharge policies.

The decrease in thermal spread is not unique to the Ligasure device. It can also be provided by sealing with ultrasonic coagulating shears. In two studies there was no difference in thermal spread between these two devices (Goldstein 2002; Harold 2003). An ultrasonic device (Harmonic Scalple‐TM) has been used in hemorrhoidectomy and is compared to the Ligasure in one randomized controlled trial (Kwok 2005). The use of an ultrasonic device was associated with more postoperative pain inhere.

The results for patients tolerance favoured the Ligasure technique. Initially, comparable well tolerance was reported for another device, the stapling device. However, due to a high long‐term risk of recurrent hemorrhoidal disease and prolaps found in a review, the ethousiasm has been diminished. In the present review, effort was made to analyse long‐term results. Only six trials included late minor bleeding as an endpoint. The definition for minor bleeding varied between the studies; from late bleeding to hemorrhoidal symptoms. Half the trials reported no recurrences. Altomare et al. (Altomare 2008) reported 5 versus 2 bleedings and 2 versus 1 redo‐surgery within 30 days for the Ligasure and conventional group respectively. The remaining two studies had a follow‐up of 3 years. Their combined results were 1 versus 6 recurrences in favour of the Ligasure technique. Based on the results of 8 trials, the symptoms of incontinence at final follow‐up did not differ significantly. These results established the efficacy of the Ligasure only partly. Therefore, more evaluation of the long‐term risk of recurrent hemorrhoidal disease is required

Since the publication of the protocol of this review another meta‐analysis has been published on this subject (Tan 2007). The authors found similar results as most of their included studies were the same. They included the results of the study of Chung et al.(Chung 2002), wherein another than Ligasure bipolar scissor technique was used. As the latest search of the present review was performed two years later, another four randomized trials were added. The evidence for at least the short‐term outcomes seemed to be growing. The additional costs for the device might be limited when general socio‐economical aspects the benefits are taken into account. With still only three reports with a reasonable follow‐up, long‐term incontinence and recurrence rates could change the evident clinical preference for Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy in terms of patient tolerance.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Since the usage of the Ligasure‐technique results in significantly less postoperative pain after hemoroidectomy without any adverse effect on postoperative complications, hospital stay and incontinence‐rate this technique is superior in terms of patient tolerance.

Implications for research.

Although there was a tendency for equal efficacy, more evaluation of the long‐term risk of recurrent hemorrhoidal disease and incontinence is required. In future studies on this subject a more comprehensive pain assessment could provide valuable additional information. If costs are taken into account, these should be analysed with general socio‐economical aspects such as an earlier return to work found in this review.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 April 2011 | New search has been performed | Updated search |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2007 Review first published: Issue 1, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 October 2008 | Amended | Final check before publication |

| 17 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 13 July 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the peer reviewers and editor for careful reading and commenting, and Jean‐Paul de Zoete (JDZ) for referering this review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain score at day 1 | 10 | 835 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.07 [‐2.77, ‐1.38] |

| 2 Pain score at day 7 | 3 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.72 [‐3.59, 0.15] |

| 3 Pain score at day 14 | 4 | 183 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.37, 0.12] |

| 4 Daily pain score first 7 days | 1 | 34 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐0.35, 1.55] |

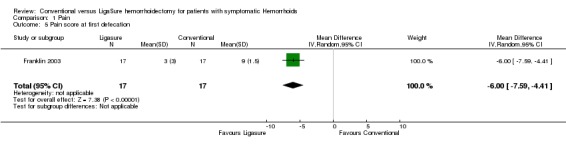

| 5 Pain score at first defecation | 1 | 34 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.0 [‐7.59, ‐4.41] |

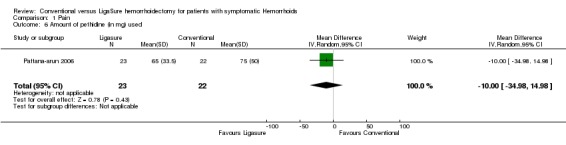

| 6 Amount of pethidine (in mg) used | 1 | 45 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.0 [‐34.98, 14.98] |

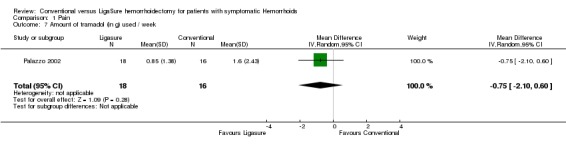

| 7 Amount of tramadol (in g) used / week | 1 | 34 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.75 [‐2.10, 0.60] |

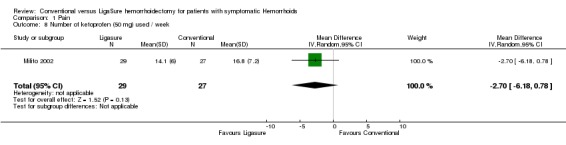

| 8 Number of ketoprofen (50 mg) used / week | 1 | 56 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.70 [‐6.18, 0.78] |

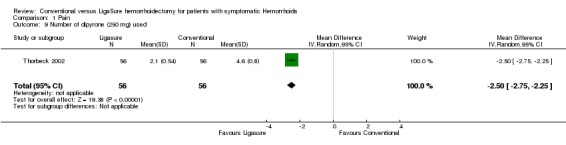

| 9 Number of dipyrone (250 mg) used | 1 | 112 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.50 [‐2.75, ‐2.25] |

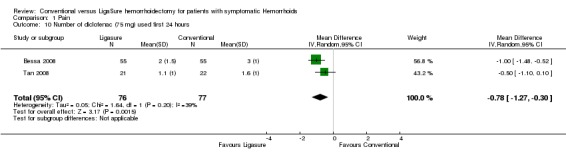

| 10 Number of diclofenac (75 mg) used first 24 hours | 2 | 153 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.78 [‐1.27, ‐0.30] |

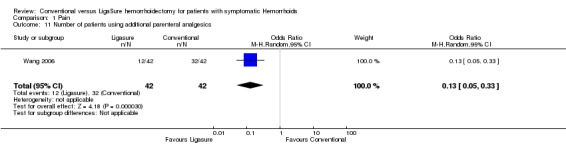

| 11 Number of patients using additional parenteral analgesics | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.05, 0.33] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 1 Pain score at day 1.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 2 Pain score at day 7.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 3 Pain score at day 14.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 4 Daily pain score first 7 days.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 5 Pain score at first defecation.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 6 Amount of pethidine (in mg) used.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 7 Amount of tramadol (in g) used / week.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 8 Number of ketoprofen (50 mg) used / week.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 9 Number of dipyrone (250 mg) used.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 10 Number of diclofenac (75 mg) used first 24 hours.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 11 Number of patients using additional parenteral analgesics.

Comparison 2. Procedure.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Operating time in minutes | 11 | 869 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.15 [‐15.09, ‐3.21] |

| 2 Intraoperative blood loss in mililitres | 2 | 124 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐22.33 [‐26.46, ‐18.20] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Procedure, Outcome 1 Operating time in minutes.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Procedure, Outcome 2 Intraoperative blood loss in mililitres.

Comparison 3. Complications.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative bleeding | 11 | 1108 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.24, 1.27] |

| 2 Urinary retention | 10 | 996 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.20, 0.87] |

| 3 Constipation | 4 | 313 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.19, 1.56] |

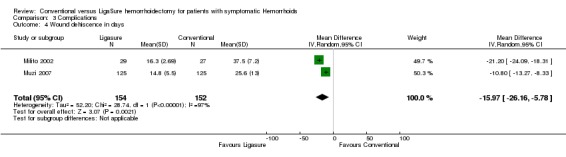

| 4 Wound dehiscence in days | 2 | 306 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐15.97 [‐26.16, ‐5.78] |

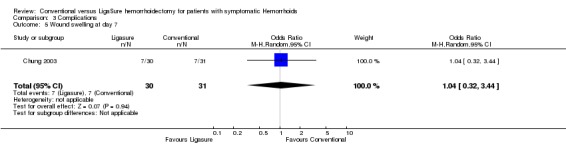

| 5 Wound swelling at day 7 | 1 | 61 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.32, 3.44] |

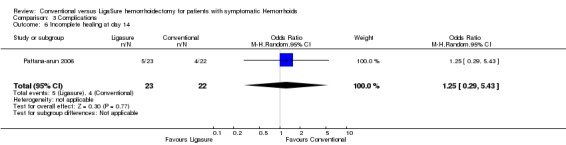

| 6 Incomplete healing at day 14 | 1 | 45 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.29, 5.43] |

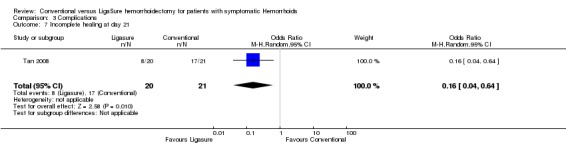

| 7 Incomplete healing at day 21 | 1 | 41 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.04, 0.64] |

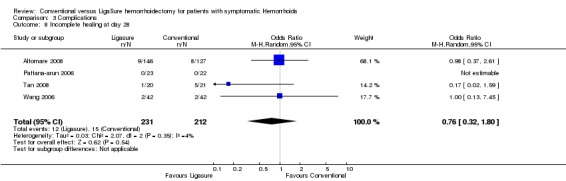

| 8 Incomplete healing at day 28 | 4 | 443 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.32, 1.80] |

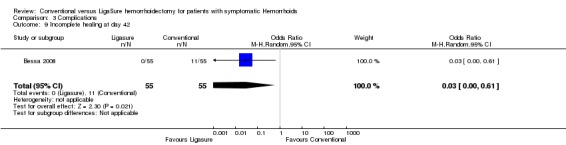

| 9 Incomplete healing at day 42 | 1 | 110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.03 [0.00, 0.61] |

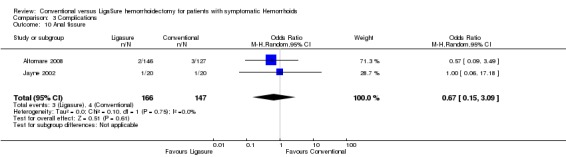

| 10 Anal fissure | 2 | 313 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.15, 3.09] |

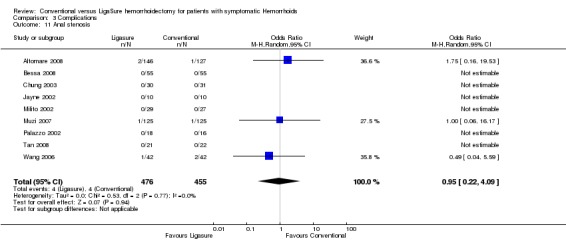

| 11 Anal stenosis | 9 | 931 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.22, 4.09] |

| 12 Late minor bleeding | 6 | 765 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.10, 5.24] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 1 Postoperative bleeding.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 2 Urinary retention.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 3 Constipation.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 4 Wound dehiscence in days.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 5 Wound swelling at day 7.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 6 Incomplete healing at day 14.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 7 Incomplete healing at day 21.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 8 Incomplete healing at day 28.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 9 Incomplete healing at day 42.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 10 Anal fissure.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 11 Anal stenosis.

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Complications, Outcome 12 Late minor bleeding.

Comparison 4. Incontinence.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up | 8 | 896 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.18, 2.61] |

| 2 Incontinence score at follow‐up | 1 | 30 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.67 [‐2.07, 0.73] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Incontinence, Outcome 1 Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Incontinence, Outcome 2 Incontinence score at follow‐up.

Comparison 5. Convalescence.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospital stay in days | 6 | 525 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.19 [‐0.63, 0.24] |

| 2 Return to work in days | 4 | 451 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.88 [‐7.59, ‐2.18] |

| 3 Number of patients unhappy with results | 2 | 70 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.16, 1.70] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Convalescence, Outcome 1 Hospital stay in days.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Convalescence, Outcome 2 Return to work in days.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Convalescence, Outcome 3 Number of patients unhappy with results.

Comparison 6. Sensitivity analysis no.1.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 MJS>3; Pain score at day 1 | 7 | 578 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.71 [‐2.53, ‐0.89] |

| 2 MJS>3; Postoperative bleeding | 8 | 851 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.14, 1.11] |

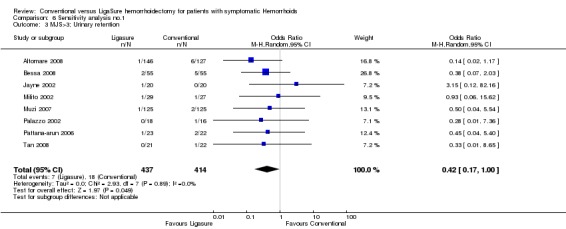

| 3 MJS>3; Urinary retention | 8 | 851 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.17, 1.00] |

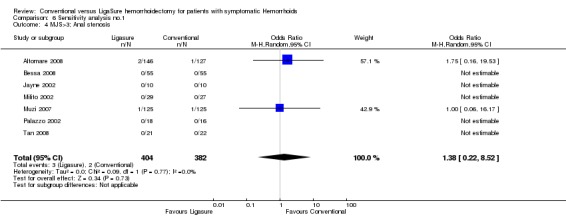

| 4 MJS>3; Anal stenosis | 7 | 786 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.22, 8.52] |

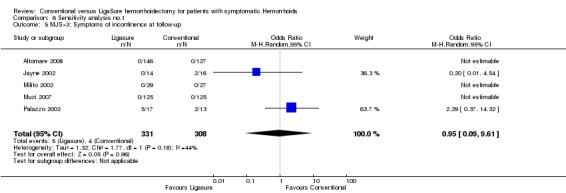

| 5 MJS>3; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up | 5 | 639 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.09, 9.61] |

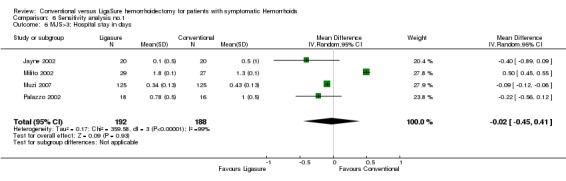

| 6 MJS>3; Hospital stay in days | 4 | 380 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.45, 0.41] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 1 MJS>3; Pain score at day 1.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 2 MJS>3; Postoperative bleeding.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 3 MJS>3; Urinary retention.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 4 MJS>3; Anal stenosis.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 5 MJS>3; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis no.1, Outcome 6 MJS>3; Hospital stay in days.

Comparison 7. Sensitivity analysis no.2.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

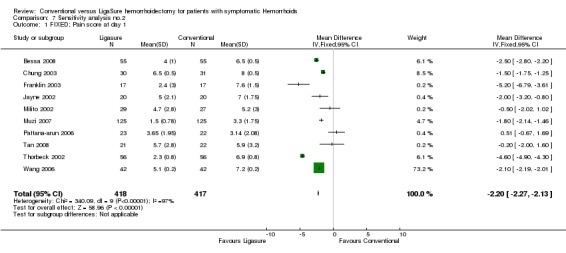

| 1 FIXED; Pain score at day 1 | 10 | 835 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐2.27, ‐2.13] |

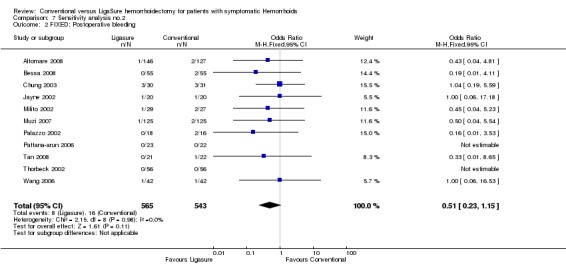

| 2 FIXED; Postoperative bleeding | 11 | 1108 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.23, 1.15] |

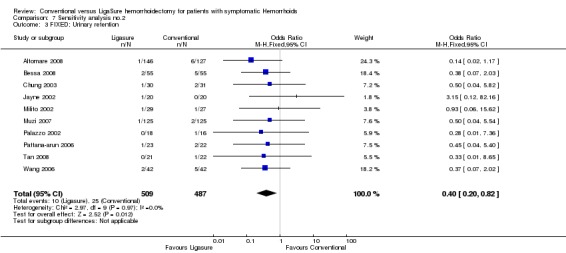

| 3 FIXED; Urinary retention | 10 | 996 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.20, 0.82] |

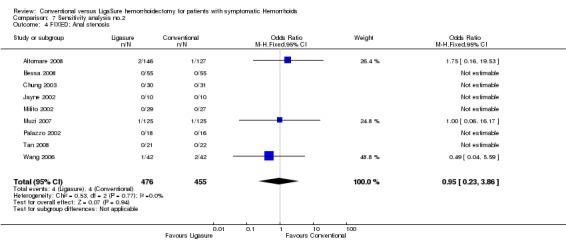

| 4 FIXED; Anal stenosis | 9 | 931 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.23, 3.86] |

| 5 FIXED; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up | 8 | 896 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.21, 1.98] |

| 6 FIXED; Hospital stay in days | 6 | 525 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.18, ‐0.13] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 1 FIXED; Pain score at day 1.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 2 FIXED; Postoperative bleeding.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 3 FIXED; Urinary retention.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 4 FIXED; Anal stenosis.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 5 FIXED; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis no.2, Outcome 6 FIXED; Hospital stay in days.

Comparison 8. Sensitivity analysis no.3.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OPEN; Pain score at day 1 | 6 | 611 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.08 [‐3.32, ‐0.83] |

| 2 OPEN; Postoperative bleeding | 7 | 645 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.12, 1.22] |

| 3 OPEN; Urinary retention | 6 | 533 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.19, 1.50] |

| 4 OPEN; Anal stenosis | 6 | 513 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 16.17] |

| 5 OPEN; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up | 5 | 478 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.11, 3.95] |

| 6 OPEN; Hospital stay in days | 4 | 380 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.45, 0.41] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 1 OPEN; Pain score at day 1.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 2 OPEN; Postoperative bleeding.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 3 OPEN; Urinary retention.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 4 OPEN; Anal stenosis.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 5 OPEN; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis no.3, Outcome 6 OPEN; Hospital stay in days.

Comparison 9. Sensitivity analysis no.4.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

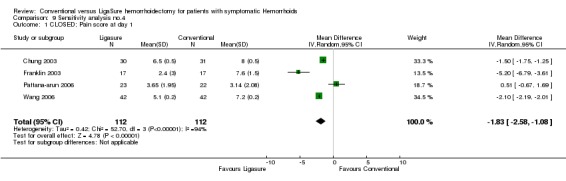

| 1 CLOSED; Pain score at day 1 | 4 | 224 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.83 [‐2.58, ‐1.08] |

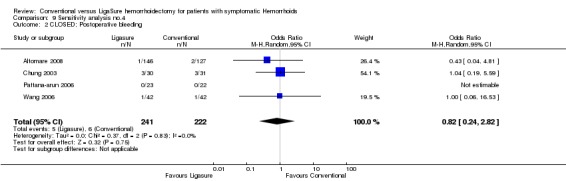

| 2 CLOSED; Postoperative bleeding | 4 | 463 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.24, 2.82] |

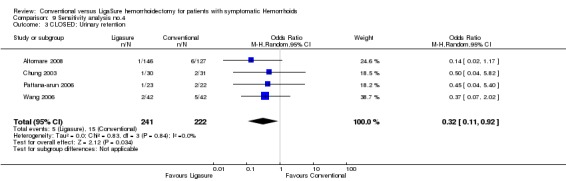

| 3 CLOSED; Urinary retention | 4 | 463 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.11, 0.92] |

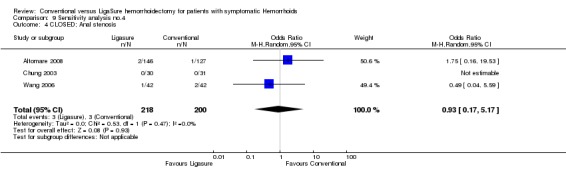

| 4 CLOSED; Anal stenosis | 3 | 418 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.17, 5.17] |

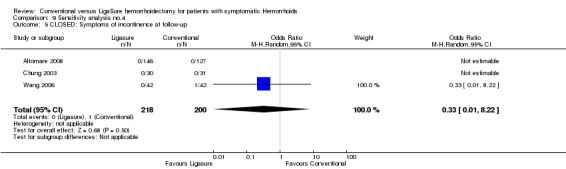

| 5 CLOSED; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up | 3 | 418 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.22] |

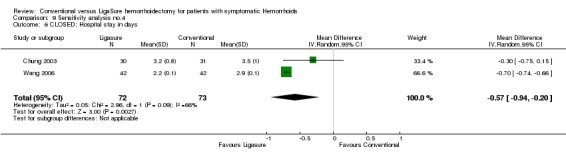

| 6 CLOSED; Hospital stay in days | 2 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.57 [‐0.94, ‐0.20] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 1 CLOSED; Pain score at day 1.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 2 CLOSED; Postoperative bleeding.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 3 CLOSED; Urinary retention.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 4 CLOSED; Anal stenosis.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 5 CLOSED; Symptoms of incontinence at follow‐up.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sensitivity analysis no.4, Outcome 6 CLOSED; Hospital stay in days.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Altomare 2008.

| Methods | Assignment: centralized with permuted blocks Follow‐up: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, obstructed defecation, anticoagulation, pregnancy, acute thrombosed hemorrhoids and hemorrhoid limited to one quadrant. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional closed technique (Loder and Phillps) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, incontinence, complications, healing time, return to work, requirements of analgesics. | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bessa 2008.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 6 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, any degree faecal incontinence. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Miligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, incontinence, complications, wound healing, hospital stay, return to work | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Chung 2003.

| Methods | Assignment: alternating Follow‐up: 4 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional closed technique (Ferguson) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, complications, wound swelling, hospital stay, return to work | |

| Notes | MJS 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Franklin 2003.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 3 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, thrombosed hemorrhoids. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional closed technique (modified Ferguson) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, incontinence, hospital stay | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Jayne 2002.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 3 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: anticoagulation, immunosuppression or regular use of analgesics, patients with ASA 3 or 4, pregnancy, and the inability to give written informed consent | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, incontinence, hospital stay, complications, bowel function, satisfaction, histology, return to normal activity | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Lawes 2003.

| Methods | Follow‐up: 13‐18 months | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | Satisfaction, incontinence | |

| Notes | Follow‐up of study of Palazzo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Milito 2002.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 6 months | |

| Participants | Symptomatic prolapsed hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, anticoagulation, undergoing simultaneousprocedure | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, analgesics use, wound dehiscence, incontinence, hospital stay, complications, bowel function, return to work | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Muzi 2007.

| Methods | Assignment: opaque numbered sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 6‐36 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: haematological disorders, anticoagulation, and medical or social factors precluding day‐case surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists grade III or IV, obesity (body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2), insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, known hypersensitivity to local anaesthetics, and drug or alcohol abuse. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operative details, duration of operation, postoperative pain, hospital stay, wound healing time, bleeding, urinary dysfunction, time to resumption of normal activities, anal stenosis, recurrence, flatus or liquid incontinence | |

| Notes | MJS 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Palazzo 2002.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Symptomatic prolapsed hemorrhoids, requiring a three‐quadrant hemorrhoidectomy. Exclusion: previous anorectal disease, anticoagulation, undergoing simultaneousprocedure | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, analgesics use, incontinence, complications, satisfaction | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Pattana‐arun 2006.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelop Follow‐up: 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, thrombosed or strangulated hemorrhoids, compromised patients, pregnancy and history of bleeding tendency. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional closed technique (Fansler) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, analgesics use, wound dehiscence, complications | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Peters 2005.

| Methods | Follow‐up: 36‐37 months | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | Pain, bleeding, discharge, pruritis, incontinence | |

| Notes | Follow‐up of study of Jayne | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Tan 2008.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelop Follow‐up: 6 weeks | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, allergy to trial medications. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, blood loss, pain, complications, wound healing. | |

| Notes | MJS 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Thorbeck 2002.

| Methods | Assignment: alternating Follow‐up: 6 months | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional open technique (Milligan‐Morgan) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, analgesics use, wound dehiscence, incontinence, complications | |

| Notes | MJS 1 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Wang 2006.

| Methods | Assignment: sealed envelopes Follow‐up: 8 weeks | |

| Participants | Grade 3 and 4 hemorrhoids. Exclusion: previous or concomitant anorectal disease, anticoagulation, and those with a hematologic disorder. | |

| Interventions | Ligasure and conventional closed technique (Ferguson) | |

| Outcomes | Operating time, pain, analgesics use, wound dehiscence, incontinence, hospital stay, compliactions, return to work | |

| Notes | MJS 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Carditello 2007 | Not randomized |

| Chen 2007 | Versus PPH stapler |

| Chung 2002 | Bipolar scissor (Powerstar‐TM) is technically not identical to Ligasure‐TM |

| Kecmanovic 2006 | Milligan‐Morgan with Ligasure technique used in all patients |

| Kraemer 2005 | Versus PPH stapler |

| Kwok 2005 | Versus Ultracision |

| Mistrangelo 2009 | Not randomized |

| Sayfan 2004 | Not randomized |

| Vasil'ev 2004 | Not randomized |

| Wang 2007 | Versus non conventional hemorrhoidectomy |

Contributions of authors

SWN developed the search strategy and searched in multiple databases for eligible papers together with IDH. The full text of these papers were retrieved and further assessed for eligibility by SWN and IDH independently. SWN and IDH extracted data on to a previously designed data extraction sheet. A third party functioned as a referee (JDZ). Data entry was cross checked by SWN. Methodological quality was assessed by SWN and IDH.

Declarations of interest

None known.

S O U R C E S O F S U P P O R T External sources of support • No sources of support supplied Internal sources of support • No sources of support supplied

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Altomare 2008 {published data only}

- Altomare DF, Milito G, Andreoli R, Arcanà F, Tricomi N, Salafia C, Segre D, Pecorella G, Pulvirenti d'Urso A, Cracco N, Giovanardi G, Romano G, on behalf of the Ligasure™ for Hemorrhoids Study Group. Ligasuretrade mark Precise vs. Conventional Diathermy for Milligan‐Morgan Hemorrhoidectomy: A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51(5):514‐519. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bessa 2008 {published data only}

- Bessa SS. Ligasure vs. conventional diathermy in excisional hemorrhoidectomy: a prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51(6):940‐944. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chung 2003 {published data only}

- Chung YC, Wu HJ. Chung YC, Wu HJ. Chung YC, Wu HJ. Chung YC, Wu HJ. Clinical experience of sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy with LigaSure. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46(1):87‐92. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franklin 2003 {published data only}

- Franklin EJ, Seetharam S, Lowney J, Horgan PG. Randomized, clinical trial of Ligasure vs conventional diathermy in hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46(10):1380‐1383. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jayne 2002 {published data only}

- Jayne DG, Botterill I, Ambrose NS, Brennan TG, Guillou PJ, O'Riordain DS. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus conventional diathermy for day‐case haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 2002;89(4):428‐432. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawes 2003 {published data only}

- Lawes DA, Palazzo FF, Francis DL, Clifton MA. One year follow up of a randomized trial comparing Ligasure with open haemorrhoidectomy. Colorectal Dis 2004;6(4):233‐235. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Milito 2002 {published data only}

- Milito G, Gargiani M, Cortese F. Randomised trial comparing LigaSure haemorrhoidectomy with the diathermy dissection operation. Tech Coloproctol 2002;6(3):171‐175. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muzi 2007 {published and unpublished data}

- Muzi MG, Milito G, Nigro C, Cadeddu F, Andreoli F, Amabile D, Farinon AM. Randomized clinical trial of LigaSure and conventional diathermy haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 2007;94(8):937‐942. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Palazzo 2002 {published data only}

- Palazzo FF, Francis DL, Clifton MA. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 2002;89(2):154‐157. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pattana‐arun 2006 {published and unpublished data}

- Pattana‐Arun J, Sooriprasoet N, Sahakijrungruang C, Tantiphlachiva K, Rojanasakul A. Closed vs ligasure hemorrhoidectomy: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Med Assoc Thai 2006;89(4):453‐458. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peters 2005 {published data only}

- Peters CJ, Botterill I, Ambrose NS, Hick D, Casey J, Jayne DG. Ligasure trademark vs conventional diathermy haemorrhoidectomy: long‐term follow‐up of a randomised clinical trial. Colorectal Dis 2005;7(4):350‐353. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tan 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Tan KY, Zin T, Sim HL, Poon PL, Cheng A, Mak K. Randomized clinical trial comparing Ligasure haemorrhoidectomy with open diathermy haemorrhoidectomy. Tech Coloproctol 2008;epub ahead of print:epub ahead of print. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thorbeck 2002 {published data only}

- Thorbeck CV, Montes MF. Haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled clinical trial of Ligasure compared with Milligan‐Morgan operation. Eur J Surg 2002;168(8‐9):482‐484. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2006 {published data only}

- Wang JY, Lu CY, Tsai HL, Chen FM, Huang CJ, Huang YS, Huang TJ, Hsieh JS. Randomized controlled trial of LigaSure with submucosal dissection versus Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy for prolapsed hemorrhoids. World J Surg 2006;30(3):462‐466. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Carditello 2007 {published data only}

- Carditello A, Stilo F. [Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy, modified by using the Ligasure radiofrequency coagulator]. Chir Ital 2007;59(1):99‐104. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2007 {published data only}

- Chen S, Lai DM, Yang B, Zhang L, Zhou TC, Chen GX. [Therapeutic comparison between procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids and Ligasure technique for hemorrhoids]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2007;10(4):342‐345. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chung 2002 {published data only}

- Chung CC, Ha JP, Tai YP, Tsang WW, Li MK. Double‐blind, randomized trial comparing Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy, bipolar scissors hemorrhoidectomy, and scissors excision: ligation technique. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45(6):789‐794. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kecmanovic 2006 {published data only}

- Kecmanovic DM, Pavlov MJ, Ceranic MS, Kerkez MD, Rankovic VI, Masirevic VP. Bulk agent Plantago ovata after Milligan‐Morgan hemorrhoidectomy with Ligasure. Phytother Res 2006;20(8):655‐658. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kraemer 2005 {published data only}

- Kraemer M, Parulava T, Roblick M, Duschka L, Muller‐Lobeck H. Prospective, randomized study: proximate PPH stapler vs. LigaSure for hemorrhoidal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48(8):1517‐1522. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kwok 2005 {published data only}

- Kwok SY, Chung CC, Tsui KK, Li MK. A double‐blind, randomized trial comparing Ligasure and Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48(2):344‐348. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mistrangelo 2009 {published data only}

- Mistrangelo M, Mussa B, Brustia R, Gavello G, Mussa A. [Ligasure haemorrhoidectomy. Personal experience]. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80(3):199‐204. [PUBMED: 20131537] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sayfan 2004 {published data only}

- Sayfan J, Becker A, Koltun L. Sutureless closed hemorrhoidectomy: a new technique. Ann Surg 2001;234(1):21‐24. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vasil'ev 2004 {published data only}

- Vasil'ev SV, Soboleva SN, Itkin IM, Dzhaparidze BV. [Open hemorrhoidectomy with using the apparatus controlled bipolar electrocoagulation]. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek 2004;163(4):75‐78. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2007 {published data only}

- Wang JY, Tsai HL, Chen FM, Chu KS, Chan HM, Huang CJ, Hsieh JS. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of Starion vs Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy for prolapsed hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50(8):1146‐1151. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Campbell 2003

- Campbell PA, Cresswell AB, Frank TG, Cuschieri A. Real‐time thermography during energized vessel sealing and dissection. Surg Endosc 2003;17(10):1640‐1645. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferguson 1971

- Ferguson, JA, Mazier, WP, Ganchrow, MI, Friend, WG. The closed technique of hemorrhoidectomy. Surgery 1971;70:480. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldstein 2002

- Goldstein SL, Harold KL, Lentzner A, Matthews BD, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Pratt B, Lipford EH, Heniford BT. Comparison of thermal spread after ureteral ligation with the Laparo‐Sonic ultrasonic shears and the Ligasure system. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2002;12(1):61‐63. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harold 2003

- Harold KL, Pollinger H, Matthews BD, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Heniford BT. Comparison of ultrasonic energy, bipolar thermal energy, and vascular clips for the hemostasis of small‐, medium‐, and large‐sized arteries. Surg Endosc 2003;17(8):1228‐1230. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jayaraman 2006

- Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PH, Malthaner RA. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue CD005393. [CENTRAL: 10.1002/14651858.CD005393.pub2.; MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kehlet 2006

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367(9522):1618‐1625. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MacRea 2002

- MacRae HM, Temple LK, McLeod RS. A meta‐analysis of hemorrhoidal treatments. Semin C R Surg 2002;13:77. [Google Scholar]

Madoff 2004

- Madoff RD, Fleshman JW, Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology 2004;126(5):1463‐1473. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Milligan 1937

- Milligan ET, Morgan CN, Jones LE. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and the operative treatment of haemorrhoids. Lancet 1937;2:1119. [Google Scholar]

Moher 1999

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, Pham B, Klassen TP. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: implications for the conduct of meta‐analyses. Health Technol Assess 1999;3(12):1‐98. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pandini 2006

- Pandini LC, Nahas SC, Nahas CS, Marques CF, Sobrado CW, Kiss DR. Surgical treatment of haemorrhoidal disease with CO2 laser and Milligan‐Morgan cold scalpel technique. Colorectal Dis 2006;8(7):592‐595. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tan 2007

- Tan EK, Cornish J, Darzi AW, Papagrigoriadis S, Tekkis PP. Meta‐analysis of short‐term outcomes of randomized controlled trials of LigaSure vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy. Arch Surg 2007;142(12):1209‐1218. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

You 2005

- You SY, Kim SH, Chung CS, Lee DK. Open vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48(1):108‐113. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]