Abstract

Background

Sexual offending is a serious social problem, a public health issue, and a major challenge for social policy. Victim surveys indicate high incidence and prevalence levels and it is accepted that there is a high proportion of hidden sexual victimisation. Surveys report high levels of psychiatric morbidity in survivors of sexual offences.

Biological treatments of sex offenders include antilibidinal medication, comprising hormonal drugs that have a testosterone‐suppressing effect, and non‐hormonal drugs that affect libido through other mechanisms. The three main classes of testosterone‐suppressing drugs in current use are progestogens, antiandrogens, and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. Medications that affect libido through other means include antipsychotics and serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs).

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of pharmacological interventions on target sexual behaviour for people who have been convicted or are at risk of sexual offending.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (2014, Issue 7), Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, and 15 other databases in July 2014. We also searched two trials registers and requested details of unidentified, unpublished, or ongoing studies from investigators and other experts.

Selection criteria

Prospective controlled trials of antilibidinal medications taken by individuals for the purpose of preventing sexual offences, where the comparator group received a placebo, no treatment, or 'standard care', including psychological treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of authors, working independently, selected studies, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. We contacted study authors for additional information, including details of methods and outcome data.

Main results

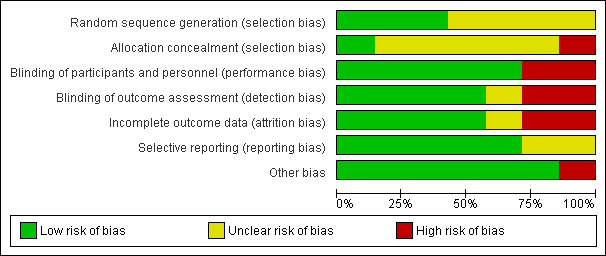

We included seven studies with a total of 138 participants, with data available for 123. Sample sizes ranged from 9 to 37. Judgements for categories of risk of bias varied: concerns were greatest regarding allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, and incomplete outcome data (dropout rates in the five community‐based studies ranged from 3% to 54% and results were usually analysed on a per protocol basis).

Participant characteristics in the seven studies were heterogeneous, but the vast majority had convictions for sexual offences, ranging from exhibitionism to rape and child molestation.

Six studies examined the effectiveness of three testosterone‐suppressing drugs: cyproterone acetate (CPA), ethinyl oestradiol (EO), and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA); a seventh evaluated two antipsychotics (benperidol and chlorpromazine). Five studies were placebo‐controlled; in two, MPA was administered as an adjunctive treatment to a psychological therapy (assertiveness training or imaginal desensitisation). Meta‐analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity of interventions, comparators, study designs, and other issues. The quality of the evidence overall was poor. In addition to methodological issues, much evidence was indirect.

Primary outcome: recividism. Two studies reported recidivism rates formally. One trial of intramuscular MPA plus imaginal desensitisation (ID) found no reports of recividism at two‐year follow‐up for the intervention group (n = 10 versus one relapse within the group treated by ID alone). A three‐armed trial of oral MPA, alone or in combination with psychological treatment, reported a 20% rate of recidivism amongst those in the combined treatment arm (n = 15) and 50% of those in the psychological treatment only group (n = 12). Notably, all those in the 'oral MPA only' arm of this study (n = 5) dropped out immediately, despite treatment being court mandated.

Two studies did not report recidivism rates as they both took place in one secure psychiatric facility from which no participant was discharged during the study, whilst another three studies did not appear directly to measure recividism but rather abnormal sexual activity alone.

Secondary outcomes:The included studies report a variety of secondary outcomes. Results suggest that the frequency of self reported deviant sexual fantasies may be reduced by testosterone‐suppressing drugs, but not the deviancy itself (three studies). Where measured, hormonal levels, particularly levels of testosterone, tended to correlate with measures of sexual activity and with anxiety (two studies). One study measured anxiety formally; one study measured anger or aggression.

Adverse events: Six studies provided information on adverse events. No study tested the effects of testosterone‐suppressing drugs beyond six to eight months and the cross‐over design of some studies may obscure matters (given the 'rebound effect' of some hormonal treatments). Considerable weight gain was reported in two trials of oral MPA and CPA. Side effects of intramuscular MPA led to discontinuation in some participants after three to five injections (the nature of these side effects was not described). Notable increases in depression and excess salivation were reported in one trial of oral MPA. The most severe side effects (extra‐pyramidal movement disorders and drowsiness) were reported in a trial of antipsychotic medication for the 12 participants in the study. No deaths or suicide attempts were reported in any study. The latter is important given the association between antilibidinal hormonal medication and mood changes.

Authors' conclusions

We found only seven small trials (all published more than 20 years ago) that examined the effects of a limited number of drugs. Investigators reported issues around acceptance and adherence to treatment. We found no studies of the newer drugs currently in use, particularly SSRIs or GnRH analogues. Although there were some encouraging findings in this review, their limitations do not allow firm conclusions to be drawn regarding pharmacological intervention as an effective intervention for reducing sexual offending.

The tolerability, even of the testosterone‐suppressing drugs, was uncertain given that all studies were small (and therefore underpowered to assess adverse effects) and of limited duration, which is not consistent with current routine clinical practice. Further research is required before it is demonstrated that their administration reduces sexual recidivism and that tolerability is maintained.

It is a concern that, despite treatment being mandated in many jurisdictions, evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions is so sparse and that no RCTs appear to have been published in two decades. New studies are therefore needed and should include trials with larger sample sizes, of longer duration, evaluating newer medications, and with results stratified according to category of sexual offenders. It is important that data are collected on the characteristics of those who refuse and those who drop out, as well as those who complete treatment.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Aged; Child; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Androgen Antagonists; Androgen Antagonists/adverse effects; Androgen Antagonists/therapeutic use; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects; Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use; Child Abuse, Sexual; Child Abuse, Sexual/prevention & control; Desensitization, Psychologic; Desensitization, Psychologic/methods; Exhibitionism; Exhibitionism/drug therapy; Exhibitionism/prevention & control; Libido; Libido/drug effects; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Rape; Rape/prevention & control; Recurrence; Sex Offenses; Sex Offenses/prevention & control; Sex Offenses/psychology; Sexual Behavior; Sexual Behavior/drug effects

Plain language summary

Drug treatments for sexual offenders or those at risk of offending

Background

Victim surveys suggest that sexual offending is common, and survivors experience psychological problems. However, much offending goes undetected because of under‐reporting and failure to successfully prosecute offenders.

Medications used to treat sex offenders ('antilibidinal' medications) act by limiting the sexual drive (libido). There are two types, those which work by suppressing testosterone (e.g., progestogens, antiandrogens, and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues), and those that reduce sexual drive by other mechanisms (i.e., antipsychotics and serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs)).

We reviewed evidence for the effectiveness of such drugs in people who were convicted or thought to be at risk of committing sexual offences.

Search date

The evidence in this review is current to July 2014.

Study characteristics

We found seven randomised trials involving 138 participants, which provided data on 123. All were male, aged between 16 and 68 years. Offending ranged from very serious (e.g., rape) to minor criminality (e.g., exhibitionism). Comparators included placebo (five studies), psychological treatment (one study), and a combination of psychological and pharmacological treatment (one study). Five studies took place in the community and two in a secure hospital. Duration varied between three and 13 months.

Six studies examined the effectiveness of three testosterone‐suppressing drugs: cyproterone acetate (CPA), ethinyl oestradiol (EO), and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). In two of these studies, MPA was given alongside a psychological therapy (assertiveness training or imaginal desensitisation). The seventh study assessed the effectiveness of two antipsychotics (benperidol and chlorpromazine) versus placebo. Meta‐analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity of interventions, comparator groups, study designs, and other issues.

Results

Two studies reported reoffending rates formally. One trial of intramuscular MPA plus imaginal desensitisation (ID) found no reoffending at two‐year follow‐up for the intervention group (n = 10 versus one relapse within the group treated by ID alone). A three‐armed trial of oral MPA, alone or in combination with psychological treatment, reported a 20% rate of reoffending amongst those in the combined treatment arm (n = 15) and 50% of those in the psychological treatment only group (n = 12). Notably, all those in the 'oral MPA only' arm (n = 5) dropped out immediately, despite treatment being court mandated. Two studies did not report reoffending rates as they both took place in a secure psychiatric facility from which none were discharged. Three community studies did not formally report reoffending at all, focusing largely on 'abnormal sexual activity'.

Secondary outcomes: Studies reported a variety of secondary outcomes. Results suggested that the frequency of self reported deviant sexual fantasies may be reduced by testosterone‐suppressing drugs, but not the deviancy itself. Where measured, hormonal levels, particularly levels of testosterone, tended to correlate with measures of sexual activity and anxiety. One study measured anxiety formally; one study measured anger/aggression.

Adverse events: Six studies provided information on adverse events and none tested the effects of testosterone‐suppressing drugs beyond six to eight months. The most severe were reported in a trial of antipsychotic medication. Reported side effects in two trials of oral MPA and CPA included considerable weight gain. Side effects of intramuscular MPA led to discontinuation in some participants. Important increases in depression and excess salivation were reported in one trial of oral MPA. No deaths and no suicide attempts were reported in any study.

We conclude that these seven trials (published more than 20 years ago), examining only a limited number of drugs, provide a poor evidence base to guide practice. Not only were the trials small, they were of short duration, included varied participants, and none trialled the newer drugs currently in use, particularly SSRIs or GnRH analogues. The results of this review, therefore, do not allow firm conclusions to be drawn regarding pharmacological interventions as an effective intervention for reducing sexual offending.

New studies are needed that address these deficits. Data should also be collected on the characteristics of those who refuse, drop out, and complete treatment.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence was poor. We had concerns about: number of participants leaving studies, blinding of those who measured outcomes, ways in which investigators concealed allocation of treatment to those delivering it, and reporting of our primary outcome: reoffending.

Background

Description of the condition

Sexual offending is a legal construct which overlaps, but is not necessarily congruent with, the clinical constructs of disorders of sexual preference as described in the ICD‐10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (WHO 1992), or paraphilias as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition‐Revised) (APA 1994). Most, but not all, sexual offences are disorders of sexual preference and most, but not all, disorders of sexual preference are sexual offences. For instance, clinically defined sexual behaviours such as paedophilia, voyeurism, frotteurism, exhibitionism, zoophilia, and necrophilia also meet the rubric for sexual offences but, for instance, fetishism and transvestic fetishism do not, in many jurisdictions. Crimes such as rape and incest with consenting adult participants are not of themselves classified as disorders of sexual preference or paraphilias (Grubin 2008).

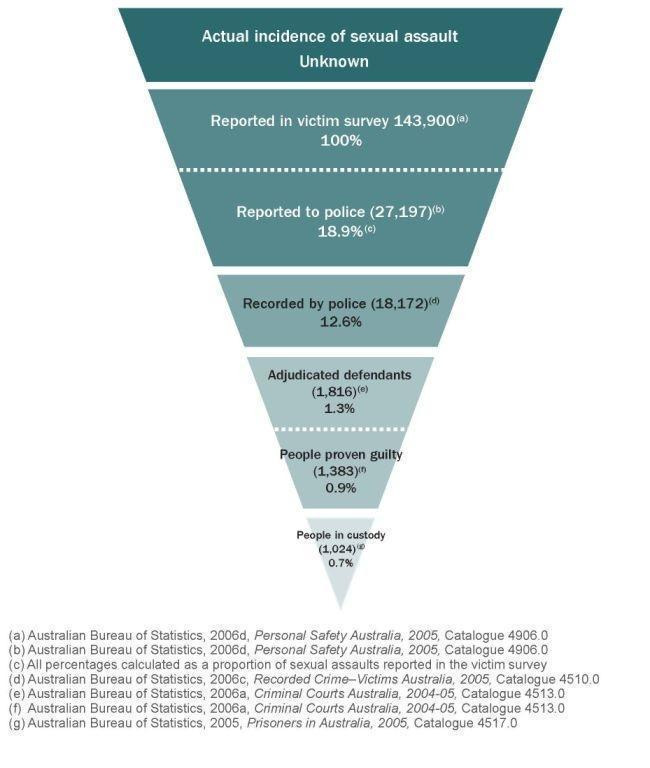

The true prevalence of sexual offending is unknown. Sexual offending accounts for only 1% of crimes recorded in England and Wales (Eastman 2012). In the US, 9.7% of prisoners have a history of sexual offending (Greenfeld 1997), with a figure of 13.3% reported in Australia (Gelb 2007). These figures are similar to the 10% reported by Taylor et al (Taylor 1998) and Duggan et al (Duggan 2013) for high security and medium security hospitals in the UK. They represent significant underestimates of the extent of the problem as many sexual offences are not reported or, if they are reported, the allegations are often subsequently withdrawn. The true proportion of offenders in custody may be only 0.7% of those responsible for offences (Farrow 2012) ‐ see Figure 1 (Gelb 2007). Surveys and reviews show a high incidence of victimisation (Hood 2002; Edwards 2003; Chapman 2004; Barth 2013; Abrahams 2014), as well as high levels of psychiatric morbidity (McCauley 1997; Hill 2000; Molnar 2001; Swanston 2003; Chapman 2004; Mchichi 2004).

1.

From Gelb 2007 (used with permission of the Sentencing Advisory Council, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)

Legislative provisions reflect widespread societal concern. For instance, in the UK, provisions in the Sexual Offences Act 2003 include substantial increases in sentence length and state control, in terms of notification requirements and supervision, for up to 10 years after a sentence has been spent (Great Britain 2003). Again, in England and Wales, the Mental Health Act was amended in 2008 so that sexual deviancy was no longer excluded as a criterion for compulsory detention (DOH 2008). In Germany, penal reform in 1998 made the treatment of sexual offenders mandatory for such offenders receiving a prison sentence of more than two years (Lösel 2005). Similarly, the treatment of mentally disordered offenders in the US includes state‐specific sexual predator laws that allow for the preventative detention of those believed to be at high risk of sexually offending in the future. Finally, also in the US, there is Megan's Law, which allows information on registered sex offenders against children to be made available to the community; a similar law is now in force in the UK (AML 2007; Lipscombe 2012). While this concern is understandable, other commentators have argued that exaggerating the danger that sexual offenders pose is problematic as it may increase public fear, and stigmatise and hinder rehabilitation of offenders who have changed their lifestyles, while wasting valuable resources on unnecessary surveillance (Soothill 2000).

Although therecorded pattern of sexual reoffending is relatively infrequent, with reported rates of 13.4% over four to five years' follow‐up (Hanson 1998), long‐term follow‐up studies demonstrate that recividism may persist over a long period, especially for paedophilia (Prentky 1997). This has two significant consequences for the design of trials and their interpretation. First, its low frequency means that the difference between the two trial conditions has to be substantial in order for an effect to be demonstrated. Second, since reoffending can occur many years after release, follow‐up needs to be long‐term in order to capture data from all of those who reoffend.

The literature also recognises that those convicted of a sexual offence are not homogeneous: the most common distinction is drawn between rapists and child molesters, as these are deemed to have different aetiologies, presenting characteristics, and likelihood of reoffending over different time periods (Prentky 1997; Firestone 2000). Another important confounder in the interpretation of trial data is the degree of psychopathy possessed by the sexual offender, as those with high levels are less likely to benefit from treatment and more likely to reoffend (Seto 1999; Hildebrand 2004).

Description of the intervention

A companion review of psychological interventions for those who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending has recently been updated (Kenworthy 2003; Dennis 2012), and it is important to note the underlying difference between the psychological and antilibidinal approaches with which this review is concerned (see below). The objective of psychological interventions is, in general, to change the sexual behaviour of the offender while leaving libido intact, whilst encouraging a change from non‐consensual to consensual sexual activity, with partners of appropriate (legal) age. In contrast, many (although not all) antilibidinal interventions, such as the pharmacological interventions reviewed here, are administered to diminish or altogether eradicate sexual desire and capacity (Abel 2000), either temporarily (to provide a 'window' in which psychological treatments may be attempted) or permanently.

Surgical antilibidinal interventions, such as orchiectomy or orchidectomy (male castration) or neurosurgery, require a separate review.

Medication

Antilibidinal medications broadly fall within two categories, namely those hormonal medications that have a testosterone‐suppressing effect, and non‐hormonal medications that affect libido through other mechanisms.

Hormonal drug therapy

The three main classes of testosterone‐suppressing drugs used today include progestogens, antiandrogens, and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. Prior to the 1960s, oestrogens were prescribed in North America to treat sexually aggressive men but this practice has been discontinued (Grubin 2008).

The commonly used testosterone‐suppressing drugs include medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), cyproterone acetate (CPA), triptorelin, and goserelin.

Non‐hormonal drug therapy

Non‐hormonal drugs that affect libido through means other than via testosterone suppression include antipsychotics and serotonergic antidepressants (SSRI) (Baldwin 2003). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been associated with reduced libido and delayed orgasm in 60% to 70% of people taking them (Montejo 2001).

Exact information on rates of administering medication to sexual offenders in practice are limited, as are precise data on the acceptability of treatments. Some data suggest that psychological treatment is considered acceptable by two‐thirds of offenders, but pharmacological treatment only by one‐third (Nagayama‐Hall 1995). Researchers in Germany, concerned at the absence of data for drug use in a clinical context, recently conducted a survey of German forensic‐psychiatric hospitals and outpatient clinics and found that of 611 sex offenders, "almost all were treated psychotherapeutically and 37% were receiving an additional pharmacological treatment" (Turner 2013, p 570). Of the latter, 15.7% were treated with testosterone‐lowering medications (10.6% with a GnRH agonist and 5.1% with CPA); 11.5% with SSRIs, and 9.8% with antipsychotic medications.

How the intervention might work

1.1 Testosterone‐suppressing drugs

Testosterone production in men is controlled by the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, and the gonads. Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus in a pulsatile manner, which stimulates the secretion of the gonadotrophins (luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH)), from the anterior pituitary. LH acts on Leydig cells in the testes resulting in the production and secretion of testosterone, which, in turn, has a negative feedback effect on the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus.

Testosterone has been linked to sexual development and drive in men (Grubin 2008). Testosterone has both organisational and activational effects on the nervous system. The former is associated with the structural development of the brain and the latter with the effect of testosterone on the organised brain (Sisk 2006). The effect of testosterone on sexual interest and arousal appears to be one of maintaining a level of spontaneous functionality as opposed to being stimulus bound (Bancroft 1989). These effects are not immediate and take several weeks to occur after a change in plasma testosterone levels (Bancroft 2005).

The direct relationship between testosterone and sexual behaviour, however, is confounded by the link between testosterone and aggressive behaviour (Book 2001). In addition, there is evidence that behaviour may itself result in changes in plasma testosterone levels and that testosterone levels may be more closely associated with dominance (Mazur 1980).

GnRH analogues appear to be more effective than CPA and MPA in producing long‐term castration levels of testosterone (McEvoy 1999). However, few studies address the issue of reversibility after long‐term use of greater than two years, bar one small cohort study (Rösler 1998). GnRH analogues and MPA have been shown to produce histological changes, such as reduced Leydig cell numbers, in the testes of animals (Avari 1992; Rao 1998; McEvoy 1999).

All three agents are associated with potential adverse effects (Reilly 2000), such as precipitation or aggravation of cardiac conditions (De Voogt 1986; Pierce 1995), gynaecomastia, weight gain, hot flushes, or depression (Grubin 2008). CPA has been associated with fatal liver toxicity (Parys 1991; Roila 1993). An established consequence of low testosterone is osteoporosis (Stĕpán 1989; Schot 1990), a potentially serious and difficult to manage side effect of testosterone suppression, which is more likely to occur with long‐term use of GnRH agonists.

1.2 Drugs that decrease libido via mechanisms unrelated to testosterone suppression

Although the exact mechanisms are unclear, animal studies suggest that mesolimbic dopamine has an activating effect on sexual arousal and that serotonin has the opposite effect (Hull 2004). In addition, dopamine antagonism may result in prolactin elevation, which may have an effect on libido (Bancroft 2005); such drugs may also positively impact on mental disorders prevalent in this population (e.g., depression, substance misuse, and personality disorder) (Fazal 2006).

Both classes of medication in this category, although widely used, have potentially troublesome side effects. The adverse effects of antipsychotics include tardive dyskinesia (Kane 2006), weight gain (Allison 1997), and impaired glucose tolerance (Haddad 2004).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally considered to have a more benign side effect profile than other antilibidinal interventions. However, SSRIs are associated with restlessness, agitation, and suicidality, particularly in the under 30 age group (CSM Working Group 2004), and they are also associated with an increased risk of bleeding (Paton 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Both the prevalence of sexual offending and the association between victimisation and subsequent mental health problems mean that these offences make a significant contribution to mental health morbidity and societal concern more generally. Therefore, there is strong social and political pressure to address this problem, not just in terms of helping the victims but in preventing sexual recidivism (Hanson 2000).

Furby et al, in one of the first major reviews of sex offender recividism, concluded that there was little evidence for any intervention for sex offenders (Furby 1989). This report was criticised by Marshall and Pithers (Marshall 1994), as it contained several flaws, including potential biases against treatment effects, duplication of data, and reliance on outdated programmes. Nagayama‐Hall and colleagues subsequently published a meta‐analysis of 12 of the most recent treatment studies of sexual offenders and found a modest treatment effect for both cognitive behavioural and hormonal treatment, which were both significantly more effective than behavioural therapy but not significantly different from one another (Nagayama‐Hall 1995).

An early Cochrane review looked at all types of interventions for sexual offending (White 1998); it was partially updated in 2003 in a review that considered only psychological interventions (Kenworthy 2003, later updated as Dennis 2012). The older review identified only one small trial (n = 21) that compared antiandrogen medication (MPA) plus a psychological intervention versus the same psychological intervention and identified no significant difference between the two groups (McConaghy 1988). The review authors concluded that there were too few data to come to any conclusion about the effectiveness of MPA.

Adi 2002 reviewed the clinical effectiveness and cost‐consequences of SSRIs in the treatment of sex offenders but identified no RCTs and only nine case series studies with a total of 225 participants. The authors concluded that there were insufficient data of high enough quality to come to any conclusion.

Subsequently, a systematic review by Lösel and Schmucker was produced which, like that by White et al, considered all treatment options for sex offenders but included studies of a larger range of designs (Lösel 2005). They reported a treatment effect size of 3.08 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.40 to 6.79, P value < 0.01) for antilibidinal medication based on six identified studies. However, the review does not report sample sizes or study designs for pharmacological interventions and the methodologies of the included studies were unclear. Briken and Kafka conducted a literature review of the area, which concluded that medication interventions "show definite promise" (p 609), but deplored the absence of randomised controlled trials and recommended pharmacological treatment be combined with other treatments, including cognitive behavioural therapy and community supervision (Briken 2007).

There is, therefore, an urgent need for an up‐to‐date systematic review.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of pharmacological interventions on target sexual behaviour for people who have been convicted or are at risk of sexual offending.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials such as those where allocation was undertaken on surname.

Types of participants

Adults aged 18 years old and over, treated in institutional (prison or psychiatric facility) or community settings for sexual behaviours that have resulted in conviction or caution for sexual offences, offences with a sexual element, or violent behaviours with a sexual element (for example, sexual offences where murder is the index offence), or seeking treatment on a voluntary basis for behaviours that would be classified as illegal.

Defining what constitutes a sexual offence in the context of the international literature can be problematic as definitions of criminally sexual behaviour differ between jurisdiction, cultures, and over time. We decided to include trials of interventions where the participants had committed a sexual offence that would be accepted by most jurisdictions as crimes, viz. penetrative or non‐penetrative sexual acts carried out by adults on non‐consenting adult victims, and penetrative or non‐penetrative sexual acts carried out by adults on consenting or non‐consenting children or adults unable to give informed consent due to their physical or mental disability, or both.

Excluded: Studies of interventions for sex offenders where there was no clear international consensus as to whether the sexual behaviour was a crime or not (although it is possible that in two studies a minority of participants may no longer meet the criteria for being 'at risk' of a crime of a sexual nature (Cooper 1981; McConaghy 1988)). General examples of exclusions include consenting same‐sex acts between adults, consenting sadomasochistic acts, and transvestitism. We also excluded interventions for sex offenders with learning disabilities as this is the subject of a separate Cochrane review (Ashman 2008).

In addition, we excluded studies concerning abnormal sexual behaviour/sexual disinhibition arising from dementia, as this is covered within the scope of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group.

Types of interventions

Pharmacological interventions versus placebo or standard care (which might include psychological interventions or no treatment). Where psychological therapy was also a part of treatment, we only analysed comparable therapies within the same comparison.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Sexual recidivism as measured by reconviction, self report, or caution (a legal construct valid in the UK and Hong Kong in which an official warning is given by police to someone who has committed a minor offence but has not been charged, to the effect that further action will be taken if they commit another such offence) or by self report.

Secondary outcomes

* Physiological capacity for sexual arousal as measured by phallometric measures (for example, penile plethysmography or PPG); number of reported spontaneous erections; achieved orgasms; circulating levels of hormones, including plasma testosterone).

* Sexually anomalous urges or sexual obsessions ('sexually anomalous' behaviours was a term coined by the late Dr Neil McConaghy to cover "the broad range of sexual paraphilic behaviours including those that attracted criminal penalties...". The term was used to avoid pejorative connotations associated with terms such as 'deviant', 'aberrant' etc.) (Blaszczynski 2011). This measure aims to capture thoughts and behaviours that participants experience as negative, but which do not always result in a formal charge, or urges likely to lead to recidivism. Such urges may be assessed (for example) by diaries or scales of intrusive deviant fantasies.

* Anxiety as measured (for example) by the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger 1983).

* Anger or aggression as measured (for example) by the State‐Trait Anger Expression Inventory‐2 (STAXI‐II) (Spielberger 1999).

Dropping out of treatment.

Adverse events, including suicide or suicide attempts, and sudden or unexpected death, from any cause.

We divided outcomes into immediate (post‐treatment to within six months), short‐term (six months to 24 months), medium‐term (24 months to five years), and long‐term (beyond five years) during the period at risk, for example, post release from prison or discharge from hospital facility. If the participants were receiving treatment in the community then we considered the period at risk as including the period during treatment and also at maximum follow‐up.

* Starred outcomes were added post‐protocol and are justified as follows:

As investigators comment, in some studies, "the population studied is one compulsorily detained" and "although this provides certain advantages, it does mean that there will be no opportunities for the deviant behavior which brought the subjects into hospital" and "therefore, other variables relevant to sexual behavior need to be measured" (p 263) (Tennent 1974).

The rationale for adding the outcomes asterisked above was based on research concerning dynamic risk factors in sex offending. They have also been added to the companion review to this one, which assesses psychological outcomes for sex offenders (Dennis 2012). These changes may be important for sex offenders yet to be released who have little opportunity to reoffend and so should also be reported on (especially those like anxiety and anger, which may particularly be affected by pharmacological action that suppresses testosterone).

In contrast to the review on psychological interventions, we did not include the outcome of 'cognitive distortions' (a dynamic risk factor according to Hanson 2000), as these are not generally targets of pharmacological therapy except when the latter is used to create a 'window' in which psychological therapies may be used within the context of combined modality therapy.

We did add the outcome of "physiological capacity for sexual arousal", as this is an important target of pharmacological rather than psychological treatments (particularly for those with diagnoses of paraphilias).

Appreciating that different investigators were interested in different aspects of physiological arousal in accordance with the hypothesised mechanism of the drug under investigation, we were careful to record intended action as well as results. As one set of investigators note, "Castration itself is not necessarily followed by loss of libido" (Bancroft 1974, p 262), so it may be important to assess physiological arousal (for example, via PPG) in concert with psychological arousal (for example, urges or obsessions).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We ran the first set of searches in July 2008. We updated them in 2010, again in 2013, and most recently in July 2014. We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2014, Issue 7), 8 July 2014.

Ovid MEDLINE, 1950 to 8 July 2014.

EMBASE (Ovid), 1980 to 8 July 2014.

AMED ‐ Allied and Complementary Medicine, 1985 to 8 July 2014.

ASSIA ‐ Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (CSA), 1987 to 8 July 2014.

Biosis Previews, 1985 to 9 July 2014.

CINAHL (EBSCO host), 1982 to 9 July 2014.

Copac Academic and National Library Catalogue, last searched January 2008.

IBSS ‐ International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, 1951 to 8 July 2014.

ISI Proceedings, 1990 to 9 July 2014.

ISI‐SCI ‐ Science Citation Index Expanded, 1970 to 9 July 2014.

ISI‐SSCI ‐ Social Sciences Citation Index, 1970 to 9 July 2014.

National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts Database, last searched 10 July 2014.

OpenSIGLE, last searched July 2008.

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, last searched 8 July 2014.

PsycINFO (Ovid), 1806 to 9 July 2014.

Social Care Online, last searched 9 July 2014.

Sociological Abstracts, 1952 to 9 July 2014.

ZETOC, last searched September 2010.

The OpenSIGLE website was being redesigned at the time of searching in 2010 and the export function was not available; test searches of OpenGrey in 2013 were unproductive and we decided not to run further searches in this database. We searched ZETOC up until 2010, but not for later updates because of the large volume of irrelevant records. Any relevant records were also found in other databases.

In addition, we added searches of two clinical trials registers for this update:

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/en/) (8 July 2014);

Clinicaltrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (8 July 2014).

We used randomised controlled trial filters as appropriate. We applied no restrictions based on language, date, or publication status. See Appendix 1 for the full list of databases and search terms used.

We constructed the electronic searches taking into account the changing terminology and perception of sex offences. We recognise that several of these terms would now be regarded as unacceptable or misleading, or both, as terms signifying sexual offending.

Searching other resources

Handsearching

We searched reference lists of included studies for additional relevant trials along with the reference lists of reviews.

Requests for additional data

We attempted to contact investigators from each included study and we contacted known experts in the field for information regarding unpublished data or ongoing studies, or both. These included Paul Federoff (Canada), Don Grubin (UK), Markus Kruesi (USA), Stephen Hucker (Canada), and Martin Kafka (USA).

Data collection and analysis

Except where indicated in Differences between protocol and review, we followed the methods outlined in the protocol for this review (Khan 2009).

Selection of studies

A minimum of two review authors working in pairs (NH, MF, OK, JD, and MP) independently read and assessed the titles and abstracts of studies identified through searches of electronic databases. Two review authors (NH, MF or JD) then independently assessed full copies of those papers that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We resolved uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review through consultation with a third review author (OK). Review authors were not blinded to the name(s) of the study author(s), their institution(s), or publication sources at any stage of the review.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (MF, NH and/or JD) extracted data independently using a piloted data extraction form. We extracted information on study design and implementation, setting, sample characteristics, intervention characteristics, and outcomes from all included studies. NH, JD, and/or OK entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan) software (Review Manager 2014). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted the authors and asked them to supply the missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, two review authors (MF, NH, and/or JD) independently completed The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a). This required authors to assess the degree to which:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated ('sequence generation');

the allocation was adequately concealed ('allocation concealment');

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study ('blinding');

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting.

We made assessments for each domain as 'low', 'unclear', or 'high' risk of bias.

Sequence generation

We determined whether studies used computer‐generated random numbers, table of random numbers, drawing lots or envelopes, coin tossing, shuffling cards, or throwing dice.

Low risk: the study authors explicitly stated that they used one of the above methods.

High risk: the authors did not use any of the above methods.

Unclear: there is no information on the randomisation method or it is not clearly presented.

Allocation concealment

We evaluated whether investigators and participants could foresee assignments before screening was complete and consent was given.

Low risk: researchers and participants were unaware of future allocation to treatment conditions.

High risk: allocation was either not used or was not concealed from researchers before eligibility was determined or from participants before consent was given.

Unclear: information regarding allocation concealment is not known or not clearly presented.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk: participants and personnel were blinded to the treatment conditions.

High risk: there is doubt about the placebo control via differences in appearance, mode of administration etc.

Unclear: information on the blinding of participants is unclear or unavailable from study authors.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Low risk: assessors were blinded to the treatment conditions.

High risk: assessors were not blinded to the treatment conditions.

Unclear: information on the blinding of assessors is unclear or unavailable from study authors.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk: no participants dropped out or were excluded from treatment; there are some missing data but the reasons for missing data are unlikely to be related to the true outcome; or missing data are balanced in proportion across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups.

High risk: there is differential attrition across groups; reasons for dropping out of treatment are different across groups; there was inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear: the attrition rate is unclear or the authors state that intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was used but provide no details.

Selective reporting bias

To assess outcome reporting bias, we attempted to collect all study reports (and protocols, where possible) and tracked the collection and reporting of outcome measures across all available reports within each included study.

Low risk: a protocol is available and all outcome measures and follow‐ups are reported; or, a study protocol is not available but it seems clear that the published report included all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified.

High risk: data from some outcome measures are reported partially (e.g., means but no standard deviations (SD)) or without numerical data and only as 'ns' (non‐significant) or not at all.

Unclear risk: it is not clear whether all data collected by study authors were reported.

Other sources of bias

To assess other sources of bias not detailed above, we scanned all reports of included studies to attempt to ascertain whether other factors (either within or outside the control of investigators) might have introduced bias. These might have included (for example) the nature of recruitment procedures, the source of funding for the trial, changes to definitions of offending over time, etc. We supplied ratings as follows for each study:

Low risk: no issues likely to bias the results of the trial (apart from those elsewhere dealt with within the 'Risk of bias' tool) were identified;

High risk: issues likely to bias the results of the trial identified and judged serious; and

Unclear risk: it is not clear whether relevant issues identified as being likely to bias the trial did in fact do so (or if so, in what direction the bias was likely to be directed).

Measures of treatment effect

All primary outcomes and (originally) all secondary outcomes were dichotomous and we planned to use the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) to summarise results within each study. Some secondary outcomes introduced post‐protocol have been reported as continuous outcomes. Whilst no meta‐analysis has been possible in this review, we plan at update to report these as mean differences with a 95% CI. Where different scales measure the same outcome, we will calculate standardised mean differences (SMDs).

We planned comparisons for specific follow‐up periods:

within the first six months;

between six and 24 months;

between 24 months and five years;

beyond five years.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

The method planned at protocol stage was to use data from any cross‐over trials as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using approximated paired analysis by imputing missing standard deviations and with due attention to other recommendations in section 16.4 (Higgins 2011b).

Multiple treatment arms

In the protocol originally produced for this review we neglected to state our plans for handling studies in which more than one eligible treatment was compared with control. Whilst this does not affect the current results, for future updates we plan to treat such studies as follows:

a) in the event that two or more intervention arms test treatments that would (if employed against similar controls in separate trials) be amenable to combining in a meta‐analysis within our review, then we will pool data from both eligible arms against control. An example of such a study might be one in which different dosages of a drug were compared against placebo;

b) if, in contrast, trials compare two eligible interventions with an eligible control but the former are not sufficiently similar that they merit pooling (for example, should a SSRI be trialled alongside a GnRH agonist against a shared control), we will treat the study as two studies and divide the data from the control group in half (so as to avoid double counting of control group participant data).

We will transparently document all decisions made in regard to such studies.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and the number of participants that dropped out of treatment for each included study and reported the number of participants who were included in the final analysis as a proportion of all randomised participants in each study. We provided reasons, where known, for missing data in the narrative summary, as well as details of the investigators' use of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis (where applicable).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not undertake a meta‐analysis because of the heterogeneity of interventions and outcome measures used, and because of concerns regarding carry‐over effects from some cross‐over studies, especially Bradford 1993.

Plans for assessing statistical consistency of results of any meta‐analysis in future updates can be found in Appendix 2; clinical heterogeneity within the present review is described in detail in the following sections: Description of studies, Effects of interventions, and in the Discussion.

Assessment of reporting biases

We identified insufficient comparable trials for funnel plots to be feasible for this version of the review. See Appendix 2.

Data synthesis

We originally planned to synthesise data using both a fixed‐effect and a random‐effects model. In the event, no meta‐analysis was possible and all results are reported narratively below.

See Appendix 2 for plans for data synthesis for future versions of the review.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We identified insufficient comparable trials for subgroup analysis to be possible for this version of the review. See Appendix 2.

Sensitivity analysis

We identified insufficient comparable trials for sensitivity analysis to be possible for this version of the review. See Appendix 2.

Results

Description of studies

See also Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

We performed electronic searches over four consecutive time periods (2008, 2010, 2013, and July 2014). Searches were not restricted to pharmacological interventions, but included terms relevant to the companion review on psychological interventions for the same population (Dennis 2012). Due to the degree of overlap between these searches, and the fact that fewer studies related to pharmacological treatment than to psychological treatment, we judge it uninformative to produce a flowchart of selection, but report data narratively.

Searches to 2008 yielded 26,197 records (of which we examined 343 in full text).

Searches from September 2008 to October 2010 produced 10,507 records, of which we examined 53 in full text.

Searches run in June 2013, covering the period of 2010 to June 2013, resulted in 6228 records, of which we assessed nine in full text. From these 405 records, we extracted data on eight studies; we excluded one study following clarification from the author regarding lack of a placebo control (Kruesi 1992).

Searches run in July 2014, covering the period of June 2013 to 8‐9 July 2014, resulted in 4242 records, of which we assessed 10 in full text. No new studies were included but we added three new excluded studies (Excluded studies).

As far back as 2012, investigators indicated to us that they had heard that a plan for a randomised controlled trial of a newer medication (triptorelin), a GnRH agonist, was being proposed by Peer Briken and colleagues, but our investigations of the same bore no fruit. Early in 2014 we identified a study protocol for this trial (Briken 2012), whilst the reference remained 'in process' within MEDLINE. We anticipate incorporating its results into the first update of this review.

Included studies

Design

All seven included studies were published between 1974 and 1993.

All studies are described as randomised controlled trials. Four out of seven employed a cross‐over design (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974; Cooper 1981; Bradford 1993); three studies used a parallel design with no cross‐over (Langevin 1979; Hucker 1988; McConaghy 1988). Two early studies conducted in the same setting used 'Williams squares' or 'Latin squares' as part of their design (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974).

Four trials used a single comparison (Langevin 1979; Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988; Bradford 1993), whilst the other three trials each involved three conditions or 'arms' (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974; McConaghy 1988).

No study used clustering or reported stratification or matching of participants by type of offence, age, or any other participant characteristic.

Sample sizes

The total number of participants randomised in the seven included studies was 138. The number randomised to eligible arms within the studies was 123. The difference between the two figures can be accounted for by the subtraction of participants from one ineligible active treatment arm from each of two three‐armed trials, McConaghy 1988 (n = 10) and Langevin 1979 (n = 5) (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Overall sample sizes were small, varying from nine (Cooper 1981) to 37 (Langevin 1979). No study included a reference to any power calculation for change within this population.

Setting and recruitment

Location

All studies were conducted in high‐income countries, largely English speaking, whether in the UK (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974), Canada (Langevin 1979; Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988; Bradford 1993), or Australia (McConaghy 1988). We identified no study conducted in the USA. This is in contrast to Dennis 2012 (a companion review with data from over 1000 participants in trials assessing the effects of psychological interventions on sex offenders) where five of the 10 included studies were conducted in the USA.

Two studies, conducted in England by the same team of researchers (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974), recruited from within a high security psychiatric hospital. Investigators in all other studies recruited male sex offenders or those with paraphilias who were receiving outpatient treatment, the majority of whom had already committed offences or had reported 'anomalous urges' likely to result in contact with law enforcement agencies, or both.

Participants in some studies volunteered themselves for treatment after serving time in prison for offences. Other studies, for example, Cooper 1981, included a mix of referrals, including court referrals of participants awaiting trial but not yet convicted of offences; here, those who were offered treatment were told that "compliance in no way implied a more lenient judicial outcome" (p 460). Participants who were already incarcerated were told that their participation would not influence their release from hospital, although if the drug were to be found effective, it might be helpful for them on their release (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974). Hucker and colleagues recruited participants with a history of sex crimes against children, all of whom had been instructed to engage in some form of treatment as a condition of their probation (Hucker 1988); these investigators made particular efforts to record baseline data on those offered treatment within their trial (n = 48) who declined to participate as well as data for those who consented.

Participants

Gender, age, and ethnicity

Whilst the capacity of women to commit sexual offences is recognised, the majority of sex offenders are male and all participants in the included studies were male.

Participant age ranged from 16 to 68 years. Mean age varied from 26.08 (standard deviation (SD) = 3.87) (Bancroft 1974) to 43.11 (SD = 12.14) (Cooper 1981). The largest study in the review (Langevin 1979, N = 37) included no data on age.

Ethnicity of participants was not reported in any study.

Baseline characteristics of participants

Participant characteristics in the seven included studies were heterogeneous, but were clearly reported in terms of offences committed, type of paraphilia (where relevant), and other details of the presenting clinical problem.

Authors of the two British studies provided clear details of the time participants had spent in a secure hospital, their most recent offences (for example, from indecent exposure to rape to 'manslaughter with a sexual element') and the overall number of offences (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974). Unsurprisingly, given their setting, these two trials included uniformly 'severe' offenders.

Hucker 1988 included only those with a primary attraction to, and a history of offences against, children. Bradford 1993 included a 'mixed' group and reported on the nature of sexual deviation (for example, paedophilia and whether homosexual or heterosexual, and number of convictions).

Investigators involved in the Langevin 1979 study included, by comparison, less severe offenders (exhibitionists in the main, with some presenting with prominent voyeurism). The small study (n = 9) undertaken by Cooper et al provided sufficient details to make it clear that investigators had recruited two participants who would not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (hypersexuality and homosexuality but with no reported paedophilic interest) (Cooper 1981). McConaghy et al described the offending behaviour and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM‐III) (APA 1980) paraphilia status of participants in their study (McConaghy 1988), some of whom also might not meet contemporary criteria for offending.

Other demographic information is reported well in only two studies. Data on IQ scores, education, alcohol, and drug use were reported in Hucker 1988; data on marital status, literacy, IQ scores, brain damage, and mental illness (schizophrenia) were reported in McConaghy 1988.

Overall (perhaps not surprisingly given the nature of the intervention), participants in studies included within this review were more likely to be in psychiatric care (within or outside the penal system) and more likely to have a diagnosis of a paraphilia than those in the companion review on psychological treatments for this population (Dennis 2012).

Exclusion criteria

Four of the included trials did not report exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria listed by Hucker 1988, McConaghy 1988, and Bradford 1993 included having any medical conditions that would contraindicate participation, active psychosis, and an extensive list of medical and psychiatric conditions (from heart disease, cancer and sickle cell anaemia to severe depression), respectively.

Characteristics of interventions

Most interventions studied fell into the category of testosterone‐suppressing drugs involving progestogens or antiandrogens; only one small study assessed antipsychotics (Tennent 1974).

Testosterone‐suppressing drugs

Bancroft 1974 compared ethinyl oestradiol (EO) with cyproterone acetate (CPA) (both testosterone‐suppressing drugs) versus placebo; Bradford 1993 and Cooper 1981 compared cyproterone acetate (CPA) with placebo; Hucker 1988 compared medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, delivered orally) with placebo; McConaghy 1988 compared medroxyprogesterone (MPA, intramuscular) with imaginal desensitisation versus imaginal desensitisation alone. Langevin 1979 compared assertiveness training with MPA (orally) versus assertiveness training alone.

We identified no study assessing the effects of serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs) or gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues.

Trials of antilibidinal medications ('other')

Tennent 1974 compared benperidol with chlorpromazine (both antipsychotics) and placebo.

Outcomes

Sexual recidivism Only two studies formally measured recividism by reports of being charged for sexual offences (Langevin 1979; McConaghy 1988).

Two studies were both conducted in a high security facility from which participants were not due to be released for some years, if ever (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974). Recividism data therefore could not be collected. Recividism data were also not reported in Hucker 1988, where all participants undertook treatment as a condition of probation.

In two studies, it was unclear whether "sexual activity" or "abnormal sexual activity" was of a criminal nature and therefore recividism cannot be said to be formally assessed (Cooper 1981; Bradford 1993).

Physiological capacity for sexual arousal

Capacity for sexual arousal was assessed by phallometric measures (for example, penile plethysmography or PPG); number of reported spontaneous erections; achieved orgasms; and circulating levels of hormones, including plasma testosterone.

Bancroft 1974 and Tennent 1974 both used an overall "sexual activity score" derived from self reported data on the number of times that masturbation or "any overt sexual acts" led to orgasm; penile erection whilst watching erotic stimuli (film clips) was also measured in mm by means of a "mercury‐in‐rubber gauge" (Bancroft 1966; Bancroft 1971); the latter measure was also used by Bradford 1993 when assessing arousal in participants exposed to erotic stimuli during the course of a slideshow.

Participants involved in three studies were asked to provide data on numbers of spontaneous erections, sexual outlets, and activity during the course of the trials (Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988; Bradford 1993).

Physical capacity per se was not formally assessed in either Langevin 1979 or McConaghy 1988.

Sexually anomalous urges or sexual obsessions

These were measured variously as follows:

The "sexual attitude score" (a "semantic differential technique" (Marks 1967)) uses four seven‐point scales. Here, a low number indicates positive interest and a high number indicates that the participant finds the stimulus "repulsive". This scale was the most common, used by investigators involved in two studies (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974).

Cooper 1981 reported self report scores of sexual interest; whilst, in another trial, frequency of sexual fantasies were subdivided into those about adults and those about children (Hucker 1988).

Data were collected on "sexually anomalous urges" as defined above by McConaghy 1988.

Sexual arousal, as recorded by self report and rating scales in response to exposure to erotic stimuli via a slideshow, were recorded in one trial (Bradford 1993).

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured formally (Spielberger 1983) in just one study (McConaghy 1988). "Feelings of anxiety" were measured (in an unvalidated way) in one study (Bradford 1993). The 'calming' effects of interventions were reported anecdotally in two studies (Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988).

Anger or aggression

Anger was measured formally in only one included study (Bradford 1993), using the Buss‐Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) (Buss 1957). As above, the 'calming' effects of interventions were reported anecdotally in two studies (Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988).

Dropping out of treatment

All included studies reported data on dropping out of treatment; all investigators reported reasons for the same.

Adverse events

All included studies sought reports of adverse events.

Excluded studies

We formally excluded 50 studies from this review (reasons are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table). Two relevant RCTs (one planned in Norway, the other in France) appear to have been terminated within the last decade (NCT00379626 and NCT00601276, respectively).

Risk of bias in included studies

See also Characteristics of included studies and Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

Sequence generation

With the exception of Bancroft 1974 and Tennent 1974, who used Williams square designs, no study authors described their methods of randomisation; however, personal communication with an author from McConaghy 1988 provided information that clarified the method of randomisation (Blaszczynski 2011), and in these three cases, we have assessed the risk of bias for this criterion to be low. In the four remaining cases, we judged the adequacy of sequence generation in the review to be unclear (even after communication with one author, Hucker 1988).

Allocation concealment

The method of allocation concealment was not reported in any study included within this review; however personal communications with one author, Hucker 1988, caused us to reassess the risk of bias as low (as the investigator recalled remote assignment made by the pharmacist involved). In contrast, personal communication with an author involved in McConaghy 1988 led to an assessment of 'high' risk of bias for one study, as it was confirmed that no method of concealment was employed. We assessed the remaining five studies as unclear.

Blinding

Participants and personnel

Care in blinding treating staff and participants by means of an off‐site pharmacist using coded bottles of identical intervention and placebo pills was clearly reported in the two oldest studies in the review (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974); we therefore assessed these and Bradford 1993 (wherein staff are described as "blinded to allocation") as at low risk of bias. Cooper 1981 reported using a placebo pill (described as "identical" to the active intervention), which would guarantee blinding of participants; we assessed the risk of bias of this study and of Hucker 1988 within the context of this review as 'low'.

We assessed McConaghy 1988 as being at high risk of bias as the conduct of one component of the intervention (imaginal desensitisation) could not be 'blinded' to anyone involved in the study. We assessed Langevin 1979 as being at high risk of bias for the same reason (the intervention common to both arms of the trial was assertiveness training).

Outcome assessors

We assessed three studies as having an overall low risk of bias given the measures taken to blind staff or assessors to group allocation (Bancroft 1974; Tennent 1974; Hucker 1988).

We assessed two studies as having an unclear risk due to lack of information (Langevin 1979), or changes to study protocol based on participants being allowed to change treatment phase (Bradford 1993).

We rated the sixth study as having a high risk of bias as the measures of interest to this review were collected by self report only (Cooper 1981). We also assessed the remaining study, McConaghy 1988, as having a high risk of bias (in contrast to previous work by the same authors, McConaghy 1985) because no attempt was made to blind outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data are a limitation in this review. In one study, Bancroft 1974 (n = 12), no data appeared to be missing (perhaps not surprising in a study of only 12 participants in a secure setting); however, it transpired that one that dropped out during the CPA phase was "replaced" by another participant. Within a similar study conducted in the same setting (Tennent 1974), it is unclear which phases of the study saw the loss of three participants who withdrew or were withdrawn early in the study (for depression or other reasons). New participants were brought in to replace those that dropped out so that outcome data appear for 12 participants, but not those who were recruited. In Bradford 1993, we assessed the risk of bias as 'low' as reasons were supplied for the two participants who left (as well as details of their further conduct).

Attempts to compensate for missing data appear to have been made in two studies, but with varying levels of clarity. In Cooper 1981, the authors reported that to compensate for missing data, appropriate corrections were made, and analysis of variance carried out. For McConaghy 1988, a study in which a high level of dropout in the two drug intervention arms is reported (25% ‐ five of 20 ‐ did not complete their course of medication), the method of dealing with incomplete data is not given for all outcomes although results for all participants appear to be reported.

We have assessed two studies as at 'high' risk of bias for this criterion (Langevin 1979; Hucker 1988), given that the former featured a dropout rate of 67% in the combined treatment arm and 29% in that involving a psychological treatment alone. The study conducted by Hucker et al excluded data from one participant who had a 'medical condition' then lost a further four (almost 25% of the full sample) "of their own accord"; it transpired that these men had "higher frequency of fantasies about children" (p 234); the investigators themselves were unsure whether this might represent "selection bias" of a higher risk group unwilling or unable to give up fantasies about children (Hucker 1988), thus leaving the remaining data at risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Whilst we do not have access to any of the trial protocols for studies included within this review (which were largely conducted and reported in the 1970s and 1980s), we have identified no internal evidence of selective reporting in any paper, nor are any obvious outcomes missing. Testosterone data are missing from one study (Langevin 1979), but this may have been an artefact of measurement issues (data were described as "erratic"). Standard deviations are missing from some measures from another paper (McConaghy 1988), but there is no reason to suspect these were suppressed; data appear to have been lost (Blaszczynski 2011).

Other potential sources of bias

Two potential sources of bias other than those recorded above have been identified. The first was beyond the control of all researchers conducting trials where treatments are not mandated, and that is the phenomenon of those unwilling to participate in treatment at all. Hucker et al remarked that "a key question that is seldom addressed by researchers administering sex drive reducing drugs to sex offenders is the extent to which these drugs are accepted by patients" (Hucker 1988, p 229). As "those participating in a treatment trial are already a select group....", Hucker et al emphasised the need for trialists to consider "a count of all cases approached" [emphasis added]. Such information was not always clear in the studies included within this review. In their own trial, Hucker et al noted that of 100 consecutively referred cases, only 48 were "prepared to complete a comprehensive assessment, consider treatment, or even admit they might have a problem of sexual attraction toward children.... Of these 48, only 18 were willing to participate in a three month double blind trial of MPA versus placebo" (p 231).

In the trial conducted by Bradford and colleagues, authors admit in the discussion that "the placebo phase in this study is not a truly inactive phase nor pharmacologically comparable to the baseline phase" (p 396).

Effects of interventions

We did not undertake meta‐analysis for reasons of heterogeneity of different types, which we summarise briefly here.

Heterogeneity of interventions (results from different drug classes e.g., antilibidinals and antipsychotics must not be combined, as they have entirely different mechanisms of action, side effect profiles, etc.). Results of particular drugs within classes are not always comparable, e.g., ethinyl oestradiol (EO), cyproterone acetate (CPA), and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) due to differing side effect profiles and other issues (the use of MPA is now virtually abandoned in many areas except as a female contraceptive).

Even when interventions were identical, we had concerns regarding differing length of treatment regimes and carry‐over effects from cross‐over studies, especially between Cooper 1981 (where CPA was administered in a 20‐week cross‐over trial with four‐week periods of prescription or four weeks' placebo) and Bradford 1993, where treatment lasted more than a year and was delivered in blocks of 12‐week prescription or 12‐week placebo, compromised (as the investigator admits) by participants being likely to have even more extended periods on the drug if they complained about intrusive thoughts) to the extent that the "placebo phase was not a true placebo phase" (Bradford 1993).

Difference in outcome measures or dropout rates or adequacy of data to calculate effect sizes. Whilst some trials are superficially similar (Langevin 1979 and McConaghy 1988 feature MPA plus psychological treatment versus psychological treatment alone), the former trial reports few real data for analysis due to catastrophic dropout (100% of the MPA arm of the trial, 29% of the psychological treatment arm, and 67% of the combined treatment arm left the study). Finally, one might hope data from the latter trial, McConaghy 1988, might be comparable to data within the trial conducted by Hucker (Hucker 1988), but the former provided no standard deviations (SDs) for any of the means provided for continuous data (and data have since been destroyed). These trials moreover have no dichotomous data (e.g., recividism) in common.

Results are therefore reported narratively; first for antilibidinal medications involving testosterone‐suppressing drugs, then for 'other' antilibidinal medications.

1. Trials of antilibidinal medications involving antiandrogens (testosterone‐suppressing drugs) (six studies)

Six studies assessed the impact of testosterone‐suppressing drugs (Bancroft 1974; Langevin 1979; Cooper 1981; Hucker 1988; McConaghy 1988; Bradford 1993).

a) Ethinyl oestradiol to cyproterone acetate (both testosterone‐suppressing drugs) versus no treatment (one study)

Bancroft 1974 reported on 12 patients within a high security institutional setting using a cross‐over design involving six‐week periods of no treatment, ethinyl oestradiol 0.01 mg (twice daily), and cyproterone acetate (CPA) 50 mg (twice daily). Investigators claim no carry‐over effects were evident in their analysis of residual effects, and concluded that "there were no significant differences between the two drugs on any measure" (p 312).

For some outcomes, treatment was not superior to no treatment. Whilst "sexual attitudes" (deviant urges) appeared unaffected by treatment, physiological capacity could be affected.

Primary outcome

Sexual recidivism as measured by reconviction, self report, or caution

Not reported within this study.

Secondary outcomes

Physiological capacity for sexual arousal

A "sexual activity score" was derived from data given by each participant on the number of times that masturbation or "any overt sexual acts" led to orgasm (p 310); penile erection whilst watching erotic stimuli (film clips) was also measured in millimetres by means of a "mercury‐in‐rubber gauge". For "sexual interest", means for all participants (n = 12) during the ethinyl oestradiol phase were 1.58 (SD = 0.84), compared with a mean of 1.67 (SD = 0.61) in the CPA phase, and a mean of 2.9 (SD = 0.89) in the no treatment phase (trial investigators' analysis: F = 9.44; df = 2.22; P value < 0.001). Both drugs were reported to decrease sexual activity significantly in comparison with placebo. However, phallometric data (erectile responses to fantasy, slides, and film) did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect between treatments, with CPA only mildly superior to no treatment and ethinyl oestradiol not significantly different from no treatment.

Sexually anomalous urges or sexual obsessions

The trial investigators report that "When compared with no treatment... sexual attitudes were not significantly altered" (p 312). During the ethinyl oestradiol phase, mean 'sexual attitude' scores were 9.68 (SD = 4.25), compared with a mean of 10.28 (SD = 5.25) in the CPA phase and 7.24 (SD = 3.49) in the no treatment phase (investigators' analysis: F = 1.91; df = 2.22; P value = not significant (NS)).

Anxiety; anger or aggression

No data were reported for these outcomes.

Dropping out of treatment

One participant was removed before completion of the study because of depression whilst in the CPA treatment phase. Trial investigators reported that his depression was unlikely to have been due to the treatment and that "another patient . . . replaced" him (p 313).

Adverse events, including suicide or suicide attempts, and sudden or unexpected death, from any cause

No side effects attributable to the drugs were reported by the investigators. One participant was withdrawn three days after starting CPA having become depressed (see above) but this was not considered to be related to the intervention.

b) Cyproterone acetate with placebo (two studies)

Bradford 1993 recruited 19 outpatients (volunteers) who fulfilled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM‐III‐R) criteria for paraphilia for at least 12 months, and had been charged with a related criminal offence (APA 1987). The study used a cross‐over design with a one‐month baseline phase, followed by four three‐month periods of alternating cyproterone acetate (50 mg to 200 mg per day) or placebo for a total of 13 months. Investigators concluded that CPA was "an effective agent when compared to placebo in controlling important aspects of sexual activity" (Bradford 1993, p 400), albeit with caveats concerning aspects of the cross‐over design employed. These included concerns about a potential "rebound effect" following the placebo phase of treatment, and the fact that some participants were moved on to the active phase of treatment if they experienced concerns about their own sexual impulses.

Cooper 1981, in a community study, recruited nine participants. Seven of these men were described as presenting with severe sexual acting out resulting in social and legal implications, some of whom were facing trial. There is some concern that the remaining two participants might not meet the criteria for this review, as one was included on the basis of "excessive demands on his wife" (p 459) and the other was recruited due to homosexuality, without paedophilic interest. Participants were randomised in a cross‐over design as follows: no treatment, placebo, or cyproterone acetate 50 mg, twice daily; or no treatment, placebo, and then CPA, in four‐week phases. The trial investigators concluded that CPA was effective in reducing libido and associated sexual behaviour to "acceptable levels" (p 463).

We judged meta‐analysis to be inappropriate because of differences in treatment length (treatment phases varied between four and 12 weeks), and inclusion criteria (Cooper's sample being demonstrably less 'severe' than Bradford's). A further limitation, acknowledged by the latter trial investigators, was that "the placebo phase in this study is not a truly inactive phase nor pharmacologically comparable to the baseline phase" (Bradford 1993, p 396). This was related to the fact that inequalities in treatment dosage and duration will have been introduced in the Bradford study, as "if the patient complained that sexual fantasies were returning or they were concerned they might reoffend they were moved ahead to the start of the next three month phase as it was possible that their complaints were due to placebo".

Primary outcome

Sexual recidivism as measured by reconviction, self report, or caution

In the study conducted by Bradford et al, recividism data are not reported specifically, although reference is made to two study participants who had apparently "showed and reported excellent treatment responses to CPA" (p 399) but dropped out because they felt they no longer required treatment. Within six months, one participant committed a "minor homosexual pedophilic act" for which he was charged (Bradford 1993). One may infer no other charges took place during the course of the study, but this outcome does not appear to have been systematically assessed.

Cooper et al do not describe asking about recidivism via self report when assessing sexual activity (recorded as a simple count of episodes rather than subdivided by type or character); therefore it is assumed no data are available for this outcome from this study (Cooper 1981).

Secondary outcomes

Physiological capacity for sexual arousal

Clinical measures for this outcome included monthly assessments of sex hormone profiles, penile tumescence (whilst watching erotic stimuli or contemplating a particular fantasy), sexual activity scores, counts of spontaneous daytime erections, and data from episodes of programmed masturbation.

In terms of hormone profiles, measurement anomalies meant half of the prolactin data were unavailable for one study (Bradford 1993). Luteinising hormone (LH) was not significantly affected across placebo and treatment phases but testosterone and follicle‐stimulating hormones (FSH) both changed significantly in the desired directions. Results of the other objective measure for arousal (millimetres of circumference change of the penis) were analysed as well as assessments by the subjective measure for this outcome (self report). Whilst arousal thus measured was significantly decreased between the baseline and active treatment stage, there were no statistically significant differences between placebo and treatment phases (all relevant data are reported as per the published paper, in Table 1).

1. Bradford 1993 data (Table III, pp 390‐1).