Abstract

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an uncommon, almost universally fatal, asbestos-induced malignancy. New and effective strategies for diagnosis, prognostication and treatment are urgently needed. Herein we review the advances in MPM achieved in 2017. While recent epidemiological data demonstrated that the incidence of MPM-related death continued to increase in United States between 2009 and 2015, new insight into the molecular pathogenesis and the immunological tumor microenvironment of MPM, for example, regarding the role of BRCA1 associated protein 1 (BAP1) and the expression programmed death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1), are highlighting new potential therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, there continues to be an ever-expanding number of clinical studies investigating systemic therapies for MPM. These trials are primarily focused on immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with other immuno- andnon-immuno therapies. In addition, other promising targeted therapies including ADI-PEG20 focusing on argininosuccinate synthase 1 deficient tumors and Tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor of BAP1 deficient tumors are currently being explored.

Keywords: mesothelioma, immunotherapy, BAP1, mesothelin, surgery, radiation, review, therapy

Introduction and Background

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare aggressive neoplasm, closely linked to asbestos exposure. Median survival ranges between 6–8 months for patients treated with best supportive care and 12–16 months with pemetrexed-containing systemic cytotoxic therapy1. Therapy is generally palliative, improving symptoms and modestly increasing survival2, 3. While asbestos control regulations significantly decreased occupational exposure, many individuals remain at risk3, 4. Asbestos is the commercial name used to identify six different commercially used fibers, however there are over 400 asbestiform fibers in nature, and many have been proven to be carcinogenic, including erionite, and antigorite5. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) identified 45,221 MPM-related deaths in the United States (US) between 1999–2015, with a 4.8% increase in MPM deaths over this period, which was seen across all ethnicities4. Furthermore, Eastern Europe and other rapidly industrializing regions, where asbestos production and commercial use continues unregulated, may experience an increased incidence of MPM in coming decades6–8. Fewer MPM cases have been reported from East and Southeast Asia. It is hypothesized that this is secondary to a more recent industrialization and that numbers in these regions will start to rise in years to come9, 10. The ongoing increase in mortality related to MPM underscores the urgent need for asbestos control, improved understanding of the disease pathogenesis, early detection and better treatment options.

Research output in this field has been increasing steadily. A comprehensive MEDLINE literature search identified relevant publications in 2017. Based on the expert opinion of the authors we elected and reviewed all publications relevant to the epidemiology, pathology, genomics, diagnosis, staging and therapy of MPM published in 2017. In addition, we reviewed and included relevant abstracts of ongoing or recently completed MPM clinical trials presented at 2017 ASCO, 2017 ESMO and the 2017 World Congress of Lung Cancer.

Lessons in Epidemiology and Occupational Medicine

Intra-individual biopersistence of asbestos fibers over time was analyzed in 12 longitudinally collected human lung tissue samples. The results suggested that the purportedly less carcinogenic chrysotile asbestos fibers also demonstrate a long biopersistance, and therefore likely account for a proportion of MPM cases11, confirming suggestions by pre-clinical studies12. A second large study provided insights into the dose-time-response relationship between occupational asbestos exposure and pleural mesothelioma, suggesting that initial high doses of asbestos, followed by low doses thereafter are associated with the highest risk 13. Moreover, non-occupational asbestos exposure is an increasingly recognized risk factor for MPM. In this context a recent review and meta-analysis supported the critical need to evaluate MPM risk in communities with ambient asbestos or other carcinogenic fiber exposures14. Finally, in a large study across 230 countries over a 20 year period, the global burden of MPM deaths was extrapolated to about 38,400 per year, suggesting that it might be even higher than the most recently reported values15.

Developments in Diagnosis and Staging

Blood-based biomarkers serve several potential roles in MPM: diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive of response to specific therapies. The most studied blood-based biomarkers are mesothelin, osteopontin, fibulin-316, and HMGB117. In 2017, three meta-analyses respectively confirmed that pretreatment thrombocytosis18, elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio19, and high serum levels of soluble mesothelin20 are prognostic for poor survival. A recent study identified complement component 4d as a promising biomarker correlating with tumor volume, response to chemotherapy, and survival21. Other potentially useful blood based diagnostic markers for mesothelioma include midkine, calretinin and miRNA22, 23,24, 25. Deregulated miRNA levels of Let-7c-5p and miR-151a-5p in tissue may also be prognostic in MPM26. In addition, proteomic analysis of the secretome, including exosomes from MPM cells identified proteins that potentially enhance the growth and stress response, and inhibit adaptive immunity27, 28.

Clinical and pathological staging is important to determine disease prognosis and facilitate patient selection for multi-modality therapy. The IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project for the 8th edition of the AJCC/UICC staging manual updated TNM staging in MPM29–31. However the project database still overrepresented surgically treated patients and, despite recent advances in cross-sectional anatomic and functional imaging, and mediastinal lymph node sampling, clinical staging remains difficult. One challenge is the inability to distinguish tumor tissue from surrounding normal tissues for staging and follow-up using standard anatomic cross-sectional imaging. While the current version of the modified RECIST guidelines for MPM is more applicable to mesothelioma than RECIST 1.0 or 1.1, further research-based optimization of response criteria for MPM is still required. Tumor volume is increasingly recognized as an anatomical, imaging-based prognostic factor, however valid and reliable measurement of this parameter across sites and software platforms is difficult32. Attempts to create an automated volumetric assessment of tumor volume for treatment response and prognostication have been difficult due to a lack of accuracy and reproducibility33–42. The most promising results on the prognostic value of CT-based tumor volume were recently published from a multi-institutional group43, 44. de Perrot and colleagues published data suggesting that lower radiological tumor volume and smaller diaphragmatic tumor thickness predicted favorable outcomes in patients treated with neoadjuvant radiation followed by extra-pleural pneumonectomy (EPP)45, 46. In addition, a group from the UK also reported a promising random walk-based computer-aided algorithm for image segmentation47.

Progresses in Pathology

The histological diagnosis of MPM is relatively well established when performed by expert pathologists, based on positive markers of mesothelial lineage and negative markers of epithelial lineage. However, diagnostic uncertainty remains common, and continued efforts to improve the accuracy of diagnosis are needed48. One of the most challenging differential diagnoses remains the distinction between sarcomatoid MPM and sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung. In this respect, MUC4 may be a novel sensitive and specific immunohistochemical biomarker for sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung49. Moreover, GATA3 immunostaining may be useful to identify sarcomatoid and desmoplastic mesothelioma50,51. Disabled homolog 2 (DAB2) and Intelectin-1 were reported as new positive immunohistochemical markers for epithelioid mesothelioma52.

Another challenging differentiation has been between MPM and reactive mesothelial hyperplasia (RMH). While BAP1 immunohistochemistry and p16 FISH can effectively discriminate MPM from RMH, methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) loss may also be useful when identified in combination with BAP1 loss53.

In addition, several studies have focused on the evaluation of biomarkers of immunological activation and infiltrating immune cells, in particular, PD-L154–57. The “don’t eat me” signal CD47 was also shown to be overexpressed in diffuse malignant mesothelioma, and was suggested as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target of MPM58.

Molecular Advances

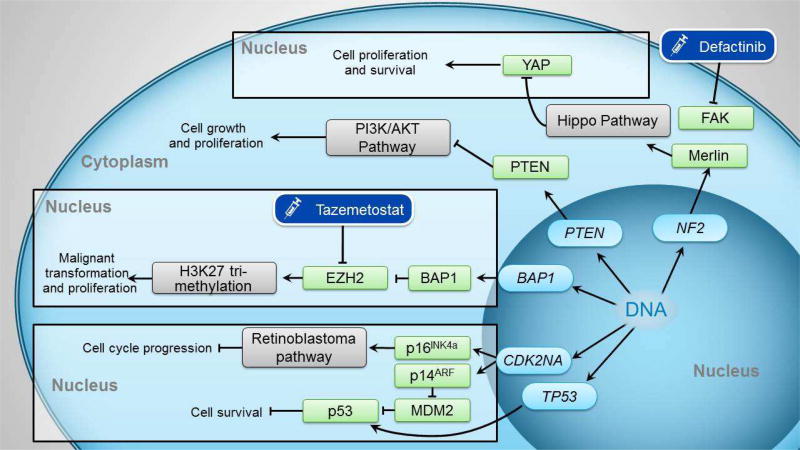

Previous genomic analysis identified the loss of various tumor suppressor genes as the most common molecular event in MPM. Commonly inactivated tumor suppressor genes include the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), BRCA1 associated protein 1 (BAP1), neurofibromin 2 (NF2), and occasionally TP53. These findings have been confirmed in a recent comprehensive genomic analysis (Figure1)59. Enhanced understanding of MPM molecular aberrations has already informed the use of targeted therapies such as the FAK inhibitor (Defactinib) for tumors lacking NF2 (COMMAND study). Unfortunately, maintenance defactinib did not improve patient outcomes and the study was terminated early. A recent publication provides a comprehensive review of molecular advances in MPM60.

Figure 1. Genetic alterations in the malignant transformation of MPM and potential therapeutic targets.

The NF2 gene encodes the merlin protein, which regulates the Hippo pathway. Loss of NF2 function leads to inactivation of the Hippo pathway, activation of the YAP transcriptional coactivator, ultimately promoting cell proliferation and survival. Defactinib is a focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitor created for potential action on the NF2 pathway, but was unsuccessful in MPM treatment.PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway, and loss of PTEN function results in over activation of this pathway, leading to cell growth and proliferation.BAP1 is a tumor suppressor gene. Without it, the EZH2 component of the PRC2 complex is activated, leading to tri-methylation of Histone 3 Lysine 27 (H3K27), and ultimately malignant transformation. Tazemetostat is an EZH2 inhibitor.CDK2NA encodes p14ARF and p16INK4a. p14ARF interacts with MDM2, resulting in MDM2 degradation and ultimate activation of p53 Loss of p14ARF expression increases MDM2 levels, decreasing p53 function, resulting in increased cell survival. p16INK4a is essential in hyperphosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of the retinoblastoma pathway. Loss of this cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor leads to unchecked activation of the retinoblastoma pathway and ultimately cell cycle progression.TP53 encodes p53, and loss of this results in loss of p53 and subsequent cell proliferation and survival.

The role of heredity in familial MPM predisposition, even without occupational asbestos exposure, has finally been proven by the discovery of germline BAP1 mutations61, and supported by murine modeling62, 63. As a result, the tumor predisposing BAP1 cancer syndrome64 has been increasingly recognized and characterized50,65. BAP1 is a deubiquitinating enzyme with several roles in regulating DNA repair and gene expression66. In addition to germline mutations predisposing to mesothelioma and other cancers, BAP1 is the most frequent acquired (somatic) mutation in sporadic mesothelioma67, 68. In 2017, both pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas were shown to have loss of BAP1 in more than 60% of cases69, 70 confirming previous findings67. Novel functions of BAP1 which likely contribute to its role in cancer in general, and in MPM in particular, have been identified. Specifically, BAP1 is a master regulator of calcium-induced apoptosis via regulation of the IP3R3 receptor ubiquitination71, as well as of cellular glycolytic metabolism72, and a radical of oxygen homeostasis73. A novel alternative splice isoform of BAP1 that misses part of the catalytic domain has also been described, and it appears to regulate DNA damage response and influence drug sensitivity74. Furthermore, frequent germline mutations in other genes associated with DNA repair have been identified in asbestos-exposed individuals who developed MPM, suggesting theses pathways to be associated with MPM predisposition75. Interestingly common germline BAP1 variants appear to mediate the risk of developing renal cell carcinoma and lung cancer76, and possibly also MPM77. When mesothelioma develops in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations, these malignancies have a much better prognosis, and survival of 5 or more years is commonly seen78.

In 2017 the role of BAP1 immunohistochemistry in MPM diagnosis and possibly prognosis has also been the focus of several studies. Specifically, BAP1 loss has been shown to reliably differentiate MPM from chronic pleuritis, benign mesothelial hyperplasia and other benign mesothelial lesions, as well as from other malignancies such as non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian serous tumors53, 79–83.

The identification of hereditary factors in MPM pathogenesis has also led to increased interest in the characterization of young patients. In 2017 it was reported that these patients show distinctive clinical, pathologic and genetic features, such as: higher likelihood of a past history of mantle radiation, family history of breast cancer, and lower rates of CDKN2A deletion than older patients84. Moreover, a subset of mesotheliomas in young patients (15%), were associated with recurrent EWSR1/FUS-ATF1 fusions85. Most importantly, the presence of clinically actionable ALK rearrangements was described in about 10% of peritoneal mesothelioma, most commonly younger women86.

Systemic Therapies

Targeting Angiogenesis

Systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin remains the only FDA approved therapy for MPM and represents the current standard of care. With treatment response rates of approximately 40% it extends median overall survival to 12–16 months87. As VEGF signaling is important in the pathophysiology of MPM, VEGF inhibition is being explored as a potential treatment option88–91. The results of the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS) demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in overall survival when bevacizumab was added to first-line cisplatin and pemetrexed chemotherapy92. However due to the observed relatively small increase in overall survival, the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy has not become standard of care in most parts of the world, and is recommended as optional in the National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) guidelines92. A cost-effectiveness analysis published in 2017 did not support the addition of bevacizumab93.

Another antiangiogenic, nintedanib, is a small molecule tyrosine-kinase inhibitor targeting VEGF receptors, fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR), and platelet derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR). The LUME-MESO study is an ongoing randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled Phase II/III examining the efficacy and safety of adding nintedanib to standard chemotherapy in non-surgical MPM patients; phase II results were reported in 201794. In 87 evaluable patients (44 nintedanib, 43 placebo), nintedanib improved progression-free survival (PFS) by 3.7 months as compared with placebo (p=0.01), most notably in those with epithelioid histology (4 months PFS, p=0.006). There was a trend towards improved overall survival (OS) (median 18.3 months versus 14.2 months) in favor of the nintedanib group, however this difference was not statistically significant; the study was not powered to examine OS. The addition of nintedanib to standard chemotherapy was safe, and these results support the rationale for the ongoing Phase III study94,95 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical studies on MPM published in 2017, non-immunotherapy

| Study | Patients | Intervention | RR% | SD% | PFS (mo) OS (mo) |

Phase | Status | Clinical Trial Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-angiogenesis Therapy | ||||||||

| LUME-Meso94 | 87 | Nintedanib C/P | 56.8 | NR | 3.7 | II/III | A | NCT01907100 |

| Mesothelin-targeted Therapy | ||||||||

| Mesothelin130 | 248 | Anetumab ravtansine | 8.4 | NR | 4.3 10.1 | II | A | NCT02610140 |

| Arginine Deprivation Therapy | ||||||||

| ADAM141 | 68 | ADI-PEG20 | NR | 52 | 3.2 | II | A | NCT01279967 |

| TRAP142 | 9 | ADI-PEG20 | 78 | 100 | 7.7 | I | R | NCT02029690 |

These studies were included in the table as they were non-immunotherapy clinical trials on human patients, with some published results in 2017. This is a complete list as of November 2017.

RR = response rate; SD = stabile disease; PFS = progression free survival; OS = overall survival; Mo = months; NR = not reported; A = active, not recruiting; R = recruiting

Blocking Immune checkpoints

In 2017 immunotherapy was clearly the focus of the largest number of clinical trials investigating new therapies for MPM. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is expressed on T cells, reducing the amplitude of CD28-mediated T cell activation96. CTLA-4 inhibition enhances T-cell activation and increases antitumor efficacy in other cancers97. Phase II studies investigating Tremelimumab, a selective human monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4, showed favorable PFS responses and toxicity profiles98, 99. In 2017, the double-blind study comparing Tremelimumab to placebo in subjects with previously treated unresectable malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE) disappointingly failed to demonstrate differences in OS or PFS between the treatment and control groups100 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical studies on MPM immunotherapy published in 2017

| Study | Patients | Drug | RR% | SD% | DCR% | PFS (mo) |

Target | Phase | Status | Clinical Trial Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Agent Immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| Anti-CTLA-4 | ||||||||||

| DETERMINE100 | 571 | Tremelimumab | 4.5 | 27.7 | 16.8 | 2.8 | CTLA-4 | II | A | NCT01843374 |

| Anti-PD1/PD-L1 | ||||||||||

| JAVELIN111 | 53 | Avelumab | 9 | 27 | 56 | 4.3 | PD-L1 | I | A | NCT01772004 |

| NivoMes110 | 34 | Nivolumab | 15 | 35 | 50 | 3.6 | PD1 | II | C | NCT02497508 |

| MERIT113 | 34 | Nivolumab | 29 | 39 | 68 | 6.1 | PD1 | II | - | * |

| KEYNOTE-028109 | 25 | Pembrolizumab | 20 | 52 | 72 | 5.4 | PD1 | I | A | NCT02054806 |

| Chicago Phase II112 | 35 | Pembrolizumab | 21 | 59 | 80 | 6.2 | PD1 | II | R | NCT02399371 |

| MAPS-2 | 54 | Nivolumab | 17 | 26 | 43 | 4.0 | PD1 | II | A | NCT02716272 |

| Combination Immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| NIBIT-Meso-1114 | 40 | Durvalumab Tremelimumab | 20 | 37.5 | 62.5 | NR | PD-L1 CTLA-4 | II | R | NCT02588131 |

| INITIATE116 | 25 | Nivolumab Ipilimumab | 20 | 4 | 72 | NR | PD1 CTLA-4 | II | R | NCT03048474 |

| MAPS-2115 | 54 | Nivolumab | 27 | 26 | 52 | 5.6 | PD1 | II | A | NCT02716272 |

These studies were included in the table as they were immunotherapy clinical trials on human patients, with some published results in 2017. This is a complete list as of November 2017.

RR = response rate; SD = stabile disease; DCR = durable controlled response; PFS = progression free survival; CTLA-4 = Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; NR = not reported; A = active, not recruiting; C = completed; R = recruiting

International study not listed in clinicaltrials.gov; (−) = information not available

The characterization of the immunological tumor microenvironment has been the subject of considerable research, and the immune status of MPM has been distinctly correlated to prognosis101, 102. Approximately 60% of MPM either expressed PD-L1 or displayed an “inflamed status” designated by a specific mRNA signature, indicating potential susceptibility to immune-directed therapy103, 104. Human monoclonal antibodies against PD1 and PD-L1 are approved for multiple malignancies including first line therapy for non-small cell lung cancer alone for tumors with ≥ 50% PD-L1 staining105, 106, or in combination with chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 staining for adenocarcinoma107. There are many ongoing clinical trials investigating PD1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors alone and in combination.

Single agent immunotherapy trials

Between 20–40% of MPM patients express PD-L1 at various levels, and PD-L1 expression correlates with a poorer prognosis103, 108. In the KEYNOTE-028 trial, the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab as subsequent line therapy was evaluated in 25 patients with PD-L1 positive MPM (≥1% PD-L1 positivity)109. Twenty percent of patients achieved a partial response, and 52% demonstrated stable disease, with a 12-month median duration of response. Furthermore, the median PFS (5.4 months) and the median OS (18 months) were notably longer than patients not receiving second-line therapy. PD-L1 positivity and level of expression were not clearly linked to likelihood of clinical response109. The Netherlands Cancer Institute is currently conducting a similar phase II trial of a PD1 inhibitor, nivolumab, in relapsed MPM patients. Preliminary results reported a disease control rate of 50% at 12 weeks, and 33% at 24 weeks, with a median PFS of 3.6 months110. Avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody also demonstrated clinical activity against MPM in the JAVELIN study, with a response rate of 9.4% and stability in 47%, and median PFS of 4.3 months111. Similar results have been reported from a phase II trial of Pembrolizumab112, and the Nivolumab MERIT study113.

The ongoing Phase III CONFIRM study randomizes patients requiring second line therapy to nivolumab or placebo (NCT03063450). The PROMISE-Meso study, comparing pembrolizumab to gemcitabine or vinorelbine in pre-treated, nonsurgical MPM patients is also currently recruiting (NCT02991482).

Immunotherapy combination trials

In 2017, preliminary findings have also been reported of several ongoing studies investigating combination immune checkpoint inhibition pairing anti-PD1/L1 therapy with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Preliminary results of the NIBIT-MESO (tremelimumab and durvalumab)114, MAPS-2115 and INITIATE (both ipilimumab and nivolumab)116 trials demonstrate potential efficacy for second line therapy of mesothelioma. MAPS-2 is a Phase II study including 108 evaluable patients treated with nivolumab versus nivolumab plus ipilimumab. While the results of the nivolumab arm were promising, the 54 patients in the combination arm had a higher DCR (51.6%), although three treatment-related deaths were also reported115. Sixty percent of patients in the NIBIT-MESO trial experienced adverse events, with three patients requiring study discontinuation due to treatment-related toxicity114. INITIATE appears to be the most favorable thus far based on preliminary data from a 12 week analysis, with a DCR of 72% and only 29% of patients who have experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicity116. Checkmate 743 is an ongoing randomized controlled Phase III study comparing the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab with pemetrexed/cisplatin as first line therapy in 600 patients, and is approaching completion of enrolment117.

Further studies are addressing combinations of anti-PD1/L1 therapy with chemotherapy. The DREAM study is evaluating the effect of durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) plus standard chemotherapy followed by durvalumab alone and has completed recruitment118. Other similar studies, such as CCTG (cisplatin/pemetrexed versus cisplatin/pemetrexed plus pembrolizumab; NCT02784171), PrECOG (Durvalumab + cisplatin/pemetrexed; NCT02899195), and SWOG (cisplatin/pemetrexed plus Atezolizumab and surgery; NCT03228537) are recruiting (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical studies on MPM; yet to be published

| Study | Drug | Target | Phase | Status | Clinical Trial Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Agent Immunotherapy | |||||

| CONFIRM | Nivolumab | PD1 | III | R | NCT03063450 |

| PROMISE-Meso | Pembrolizumab | PD1 | III | R | NCT02991482 |

| Combination Immunotherapy | |||||

| Checkmate 743 | Nivolumab Ipilimumab | PD1 CTLA-4 | III | R | NCT02899299 |

| Immunotherapy Plus Chemotherapy | |||||

| CCTG | Pembrolizumab C/P | PD1 | II | R | NCT02784171 |

| DREAM | Durvalumab C/P | PD-L1 | II | - | * |

| PrECOG | Durvalumab C/P | PD-L1 | II | R | NCT02899195 |

| SWOG | Atezolizumab C/P Surgery ±Radiation | PD-L1 | I | R | NCT03228537 |

These studies were included in the table as they are ongoing clinical trials on human patients, but have yet to publish results. This is a complete list as of November 2017.

PD-1 = programmed cell death protein 1; R = recruiting; CTLA-4 = Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; C/P = cisplatin/pemetrexed; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1

International study not listed in clinicaltrials.gov; (−) = information not available

Based on recent evidence suggesting a role for focal adhesion kinase in the regulation of the immunosuppressive microenvironment119, and synergy between FAK and PD1 inhibition120, a proof of concept phase 1b/2A clinical trial of pembrolizumab and FAK is ongoing and includes a mesothelioma cohort (NCT02758587).

While PD1/PD-L1 targeted checkpoint inhibition has demonstrated promising clinical responses in early phase studies, the results of the ongoing Phase III studies described are needed to better define the role of this approach. It is unclear whether the potentially small additional benefit of combination immune checkpoint inhibition will justify the increased toxicity.

Promising Targeted Therapies

BAP1 Loss in MPM

BAP1 plays an independent role in epigenetic regulation and malignant transformation. BAP1 loss results increased trimethylated histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), elevated enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2) expression, and enhanced repression of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) targets. In preclinical models EZH2 inhibition has been shown to be beneficial in MPM with BAP1 loss121 (Figure 1). A Phase II clinical trial investigating the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in MPM completed enrollment and results should be available soon (NCT02860286). BAP1 inactivation alters double strand DNA repair via homologous recombination122, 123. However, the potential implication for poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor sensitivity in mesothelioma have not yet been evaluated, although the MiST 1 study is currently in development in the UK.

Targeting Mesothelin

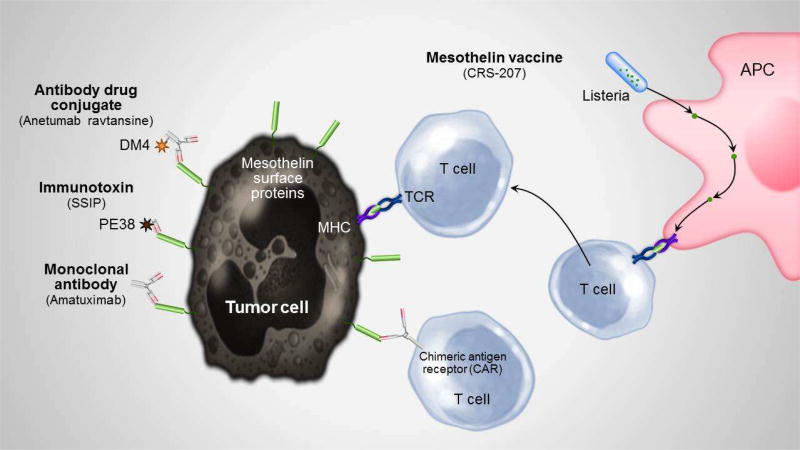

Mesothelin is a cell surface glycoprotein expressed on cells lining the pleura, peritoneum, pericardium, as well as on MPM cancer cells124, 125. It is an attractive potential target in MPM due to its high surface expression126, 127 and its suspected involvement in tumorgenesis128. Mesothelin-targeted therapies involving antimesothelin immunotoxins (SSP1), chimeric anti-mesothelin antibodies (amatuximab), mesothelin-directed antibody drug conjugates (anetumab ravtansine), Listeria based vaccines (CRS-207) and chimeric antigen receptor expressing T-cells (CAR-T-cells) have shown some promise in early phase studies129 (Figure 2), and further studies are ongoing. The recently reported randomized, open-label, active-controlled, multicenter superiority phase II study investigating Anetumab ravtansine versus vinorelbine as second line treatment in patients with mesothelin-positive MPM (248 patients) did not show a difference between the treatment groups130 (Table 1).

Figure 2. Potential therapeutic targets of mesothelin surface proteins.

This figure demonstrates the proposed mechanisms of mesothelioma treatment specifically targeting mesothelin, including via monoclonal antibodies, immunotoxins, antibody drug conjugates, virus-packed vaccine therapy, and CAR-T cell therapy.

TCR = T cell receptor; APC = Antigen presenting cell; CAR = Chimeric antigen receptor; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex

However, there are additional promising preclinical models. Recently, a preclinical study combining direct tumor injection of mesothelin immunotoxin with intra-peritoneal injection of anti-CTLA-4 therapy demonstrated an 86% complete response (CR) rate of in directly treated tumors and a 56% CR of a second untreated tumor while no CR occurred when both drugs were given separately131. A similar combination approach was also published using an anti-mesothelin immunotoxin (RG7787) plus nab-paclitaxel (albumin-bound paclitaxel) in mesothelioma cell lines. Three of four lines revealed durable CR, and studies in human patients began in 2017132.

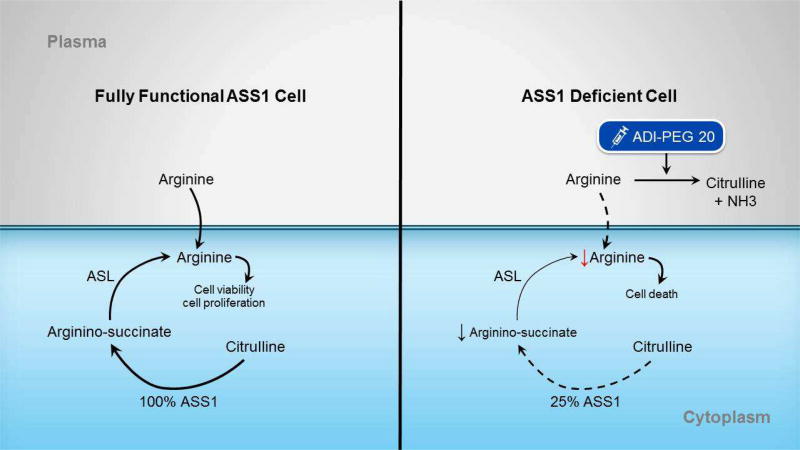

Arginine deprivation therapy

Argininosuccinate synthetase 1 (ASS1) is the rate-limiting enzyme in arginine production, and cell lines deficient of ASS1 usually require exogenous arginine supplementation133 (Figure 3). Intratumoral ASS1 deficiency has been identified in 63% of archived mesothelioma lines, and is associated with increased tumorgenesis, and more aggressive disease133–135. In vitro studies of arginine deprivation with adenosine deaminase (ADI-PEG20) improve progression free survival, with low toxicity136–140. Szlosarek and colleagues applied this concept to mesothelioma, conducting the first prospective biomarker-driven randomized controlled trial in this disease141. Forty-four patients received ADI-PEG20 plus best supportive care, and 24 patients received best supportive care only, with pre-determined interval imaging to assess for progression of disease. They observed a median PFS of 3.2 months in the treatment group as compared to 2.0 months in the control group (p =0.03)141 (Table 2). These findings led to a Phase I study of ADI-PEG20 combined with standard-of-care chemotherapy in ASS1-deficient mesothelioma and non-small cell lung cancer patients142. Nine patients (5 MPM) received escalating weekly doses of ADI-PEG20 with standard chemotherapy. No dose-limiting toxicities were encountered, and only nine reported adverse events were related to ADI-PEG20, most commonly rash. All patients experienced stable disease, and seven (78%) achieved a partial response, including one with sarcomatoid MPM. These results suggested co-administration of standard chemotherapy and arginine deprivation therapy in ASS1-negative patients was well tolerated and could improve tumor response over chemotherapy alone142. A phase II/III trial is currently recruiting MPM patients with 75% loss of ASS1143.

Figure 3. Effect of arginine deprivation on tumor cells.

A) In cells with fully functional ASS1, arginine required for the urea cycle can be created from citrulline via the ASS1 enzyme, or via direct uptake from the plasma. B) In cells deficient in ASS1, its ability to convert citrilline to arginine is decreased at baseline. ADI-PEG20 is an enzyme that breaks down arginine in the plasma into citrulline and ammonia. Giving ADI-PEG20 to cells already deficient in arginine further depletes a cell of arginine, inhibiting urea cycle function and eventually leading to cell death.

ASS1 = Argininosuccinate synthetase 1; ASL = Argininosuccinate lyase; NH3 = ammonia

NF2 Targeted Therapies

NF2 is a gene commonly inactivated in MPM. This gene encodes Merlin, which regulates the Hippo tumor suppressive signaling pathway. Hippo pathway dysregulation leads to constitutive activation of YAP1/TAZ transcriptional coactivators and enhances malignant phenotypes of MM cells144. Although the progress of MPM research based on NF2 alteration was limited in 2017, novel therapeutic strategies against YAP1/TAZ have been developed for a variety of human malignancies including MPM145. Merlin can also accumulate in the nucleus and suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the cullin E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4DCAF1. Combining a NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor, which suppresses CRL4DCAF1, and mTOR/PI3K inhibitor suppresses the growth of in NF2-mutant mesothelioma and shwannoma cells146.

Other Potential Systemic Therapies

Promising results in the adjuvant setting using the WT-1 peptide vaccine galinpepimut-S after multimodality therapy were shown in a randomized phase II trial, but lacked statistical power to draw stronger conclusions147. Autologous monocyte-derived dendric cell immunotherapy pulsed with allogenic tumor cell line lysate was effective in mice, and safe in 9 MPM patients in a phase I trial148. A novel therapeutic strategy currently at a preclinical stage for MPM is the inhibition of the pro-tumor alarmin HMGB1 by a number of compounds such as ethyl pyruvate149 and aspirin150.

The antitumoral properties of various viruses have been demonstrated in a number of malignancies151–155. MPM has been the target of many such investigations156, and promising preclinical data regarding adenovirus oncotherapy157–160 prompted human studies. HSV-1 oncotherapy has shown dramatic responses in vitro161–163, and preliminary results in human patients revealed a 50% disease stability164. In murine xenografted models of mesothelioma, intrapleural oncolytic vaccinia virus administration resulted in improved 30 day survival165. There have also been several promising studies of MPM and intraplural administration of oncolytic measles viruses166, 167, and a phase I study is ongoing to evaluate efficacy in humans168.

Other promising therapeutic candidates include the monopolar spindle 1 kinase, a kinase of the spindle assembly checkpoint that controls cell division and cell fate169; the mTOR/PI3K/AKT axis for the aggressive subset of MPM harboring simultaneous inactivating mutations of the genes LATS2 and NF2170; the sialylated protein HEG1 which can be targeted by a specific monoclonal antibody171; and targeting of MYC which is upregulated in MPM cells172. The first-in-human phase I trial of anti-CD26 antibody, YS110, was also conducted for 33 patients including 22 MPM patients173.

Several microRNAs have been reported as potential therapeutic targets with proof of concept in clinical trials, e.g. the microRNA-15/16 family174, 175, or the microRNA-137, through its control of YB-1176. Interestingly, microRNAs have been shown to contribute to the regulation of PD-L1 expression177, opening to novel potential combinations between microRNA-targeting drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors.

To further bridge preclinical and clinical results, the availability of relevant in vitro and in vivo models is crucial. In this respect, the establishment of primary MPM culture systems to test novel drugs178, 179 as well as of patient-derived xenografts from pleural mesothelioma180 represented a significant scientific advance in 2017.

Surgical resection

Optimal treatment of MPM remains controversial, particularly the role of localized therapies such as surgery and radiation. Historically, operable patients underwent EPP, which has significant complications and substantial mortality, with no appreciable benefit to the patient demonstrated by the small randomized MARS pilot study181. Pleurectomy/decortication (P/D) was then introduced in an attempt to offer a lung-sparing macroscopic resection of the tumor. Previous uncontrolled studies have suggested that this procedure is associated with fewer adverse events, with equivalent to improved survival benefits182–188. Despite these findings, clinical equipoise regarding the true benefit of either operation remains. In 2017, two large observational studies using the National Cancer Database were conducted. In the first, propensity score matching analysis showed that surgery-based multimodality therapy was associated with improved survival and may offer therapeutic benefit among carefully selected patients189. A second study evaluated 271 patients who underwent EPP, and 1036 patients who received P/D. They found no statistically significant differences in OS (19 months in the EPP group and 16 months in the P/D group; p=0.120), 30-day mortality (5%, p=0.999), or 30-day readmission rates (7% versus 5%; p=0.292), implying either technique was a realistic option for surgical candidates190. To further complicate the debate, a relatively large retrospective multicenter study suggested that extended P/D or non-extended P/D (i.e. P/D without resection of the diaphragm and/or pericardium) had similar outcomes in terms of early results and survival rate191. A recently published comprehensive review on quality of life (QoL) in MPM showed that QoL was generally better for patients undergoing P/D compared to EPP192. Presently, the ongoing MARS2 trial is comparing P/D versus no surgery; in 2017 the study surpassed its futility endpoint and patient enrollment will continue193.

Advances in Radiotherapy

The ostensible goal of surgery in MPM has been macroscopic complete resection. Surgical resection alone is associated with frequent loco-regional recurrences187, 194, suggesting adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiotherapy (RT) in a multimodality approach may have a role in improving recurrence control. However the role of RT following EPP has been questioned based on a recently published randomized controlled study195.

A systematic review assessing the role of RT following lung sparing surgery (P/D) in MPM196 concluded that RT can be delivered safely with encouraging survival data and acceptable levels of toxicity after a lung sparing procedure in MPM. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center has been at the forefront of research regarding IMRT after P/D, with studies demonstrating encouraging OS without significant increase in radiation pneumonitis197–199. Shaikh and colleagues evaluated the effect of hemithoracic intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) compared to conventional RT in patients treated with P/D200. 209 patients were analyzed (131 conventional and 78 IMRT) and demonstrated a statistically improved OS in the IMRT arm (median 20.2 versus 12.3 months, p = 0.001). Notably patients in this arm was also more likely to have achieved a macroscopically complete resection (p=0.01), to have epithelial histology (p=0.003), had higher Karnofsky performance scores upon initial receipt of RT (p=0.01), and were less likely to experience esophagitis (p=0.0007) by multivariable analysis. There were no significant differences in rates of local recurrence200.

Another promising approach has been neoadjuvant high-dose RT to the ipsilateral lung, followed by EPP, pioneered by the Toronto group lead by Drs. de Perrot and Cho. This approach has been shown to be safe and demonstrated a very favorable OS201, 202. This group treated 90 patients between November 2008 and February 2017, with a median survival of 28.3 months for the intention-to-treat population. This approach may be most beneficial in patients with epithelial tumors, low tumor volume and no lymph node metastasis45, 195.

Of note, carriers of germline BAP1 mutations may have a high risk of developing a second malignancy when treated with radiation therapy. Therefore, radiation therapy should be used with caution, similar to the treatment guidelines for patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Advances in Palliative Care

In contrast to lung cancer, a recently reported randomized study did not demonstrate any benefit of early implementation of palliative care for MPM (RESPECT-Meso Study)203. It is worth noting that the RESPECT study was conducted in the United Kingdom and Australia by centers with significant nursing support for patients, and its conclusions do not necessarily negate the potential benefit of palliative care in other healthcare settings. In addition, the recently presented PIT Study demonstrated that prophylactic intervention track site radiation did not prevent the occurrence and symptoms of tract site metastasis. The frequency of tract site metastasis was not significantly different; 3.2% in the radiotherapy group and 5.3% in the control group204.

Furthermore, recent data demonstrated that the use of an indwelling pleural catheter resulted in fewer hospital days and fewer subsequent interventions than talc slurry pleurodesis in a randomized study of 144 patients (approximately 25% of patients in each group had MPM)205. It is important to note, however, that clinical concern remains for seeding along a chest tube tract in MPM patients206.

Conclusion

The year 2017 was characterized by several important advances in this field, although only a minority would be considered practice changing. As of today, pemetrexed based cytotoxic chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab remains the standard of care for most patients. Immunotherapy trials remain an exciting area of investigation, though it remains unclear if the benefits of combination anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/L-1 immunotherapy will outweigh the increased risk of toxicity. Many single agent and combination immunotherapy trials are ongoing, and additional results are expected for 2018/19. While physician-directed immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has now been included into the current NCCN guidelines as an option for second line therapy of MPM, the efficiency of this approach remains unproven, and as such these patients should primarily be encouraged to enroll into ongoing clinical trials.

Improved understanding of MPM molecular biology and the immunological tumor microenvironment provide future therapeutic applications, most notably via the BAP1 pathway.

While the role of multimodality therapy including surgery remains controversial, it is encouraging that there are several new approaches and ongoing multicenter studies. The MARS-2 study surpassed its futility endpoint and preliminary findings are expected in the upcoming years. The 2017 advances will hopefully be followed by significant clinical translation and result in the urgently needed improved therapeutic strategies for this devastating disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Dr. Amanda McCambridge has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Dr. Andrea Napolitano has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Professor Dean Fennell reports personal fees and other non-financial support from Roche, BMS Epizyme, and Astra Zenica. He also reports receiving grants, personal fees and other non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Abbvie, and other non-financial support from MSD. These are not relevant to the submitted work. Professor Fennell also reports serving on the Advisory Boards for Roche, Epizyme, BMS, Abbvie, and Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as acting as serving on the speaker bureau for Astra Zenica, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche, for which honoraria have been granted.

- Dr. Aaron Mansfield reports serving on the Genentech Advisory Board and the AbbVie Advisory Board, for which honoraria were granted to his institution. Furthermore he reports research funding to his institution from Novartis. These are not relevant to the submitted work.

- Dr. Yoshitaka Sekido reports grants from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co, Ltd, and Eisai Co, Ltd which are not relevant to the submitted work.

- Professor Nowak reports grants from Astra Zeneca, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche International, Epizyme, Merck, and Bristol Myer Squibb. Thes are not relevant to the submitted work.

- Professor Reungwetwattana has no conflicts of interest to disclose. H. Dr. Mao has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Dr. Harvey Pass has a patent for Fibulin 3 pending, a patent regarding Osteopontin licensed to Wayne State University, and a patent regarding HMGB1 licensed to University of Hawaii.

- Dr. Michele Carbone: To be submitted separately

- Dr. Tobias Peikert reports serving on the Epizyme Advisory Board, for which an honorarium was granted to his institution. This relevance lies outside the submitted work.

- Dr. Haining Yang reports grants from NCI, grants from DoD, grants from V Foundation, grants from United-4 A Cure Foundation, grants from Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation, grants from Hawaii Community Foundation, during the conduct of the study. In addition, Dr. Yang has a patent for a Biomarker of Asbestos Exposure and Mesothelioma (Patent No: US 9,244,074 B2), a patent for Methods and Kits for Analysis of HMGB1 Isoforms, and has filed a US Provisional Patent application (no. 62/106,092) which is pending, and a patent for Treatment and Prevention of Cancer with HMGB1 Antagonists (US Application no. 14/123,607) which is pending.

References

- 1.Carbone M, Ly BH, Dodson RF, et al. Malignant mesothelioma: facts, myths, and hypotheses. Journal of cellular physiology. 2012;227:44–58. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemen RA. Mesothelioma from asbestos exposures: Epidemiologic patterns and impact in the United States. Journal of toxicology and environmental health Part B, Critical reviews. 2016;19:250–265. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2016.1195323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson WJ, Perkel G, Selikoff IJ. Occupational exposure to asbestos: population at risk and projected mortality--1980–2030. American journal of industrial medicine. 1982;3:259–311. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700030305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazurek JMSG, Wood JM, Hendricks SA, Weston A. Malignant Mesothelioma Mortality — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2017;66:214–218. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a3. 2017;Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann F, Ambrosi JP, Carbone M. Asbestos is not just asbestos: an unrecognised health hazard. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14:576–578. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Z, Carbone M, Zhang X, et al. Improving the Accuracy of Mesothelioma Diagnosis in China. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2017;12:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao W, Zhang X, Guo Z, et al. Association of Asbestos Exposure With Malignant Mesothelioma Incidence in Eastern China. JAMA oncology. 2017;3:562–564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbone M, Kanodia S, Chao A, et al. Consensus Report of the 2015 Weinman International Conference on Mesothelioma. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11:1246–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi C, Bianchi T. Malignant Mesothelioma in Eastern Asia. 2012 doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.4849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imsamran WAC, Wiangnon S, Pongnikorn D, Suwanrungrung K, Sangrajrang S, Buasom R. Cancer in Thailand. Cancer Registry Unit, National Cancer Institute Thailand. 2015:VIII. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feder IS, Tischoff I, Theile A, et al. The asbestos fibre burden in human lungs: new insights into the chrysotile debate. Eur Respir J. 2017:49. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02204-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi F, Okimoto G, Jube S, et al. Continuous exposure to chrysotile asbestos can cause transformation of human mesothelial cells via HMGB1 and TNF-alpha signaling. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1654–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacourt A, Leveque E, Guichard E, et al. Dose-time-response association between occupational asbestos exposure and pleural mesothelioma. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:691–697. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh GMPF, Riordan ASM, Keeton KAM, et al. Non-occupational exposure to asbestos and risk of pleural mesothelioma: review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:838–846. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odgerel CO, Takahashi K, Sorahan T, et al. Estimation of the global burden of mesothelioma deaths from incomplete national mortality data. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:851–858. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Gaudino G, Pass HI, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for malignant mesothelioma: an update. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:259–269. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2017.05.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Napolitano A, Antoine DJ, Pellegrini L, et al. HMGB1 and Its Hyperacetylated Isoform are Sensitive and Specific Serum Biomarkers to Detect Asbestos Exposure and to Identify Mesothelioma Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3087–3096. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuo Y, Lin L, Zhang M. Pretreatment thrombocytosis as a significant prognostic factor in malignant mesothelioma: a meta-analysis. Platelets. 2017;28:560–566. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1246712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N, Liu S, Huang L, et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:57460–57469. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian L, Zeng R, Wang X, et al. Prognostic significance of soluble mesothelin in malignant pleural mesothelioma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46425–46435. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klikovits T, Stockhammer P, Laszlo V, et al. Circulating complement component 4d (C4d) correlates with tumor volume, chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Sci Rep-Uk. 2017;7:16456. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ak G, Tada Y, Shimada H, et al. Midkine is a potential novel marker for malignant mesothelioma with different prognostic and diagnostic values from mesothelin. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:212. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnen G, Gawrych K, Raiko I, et al. Calretinin as a blood-based biomarker for mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:386. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalleri T, Angelici L, Favero C, et al. Plasmatic extracellular vesicle microRNAs in malignant pleural mesothelioma and asbestos-exposed subjects suggest a 2-miRNA signature as potential biomarker of disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber DG, Gawrych K, Casjens S, et al. Circulating miR-132-3p as a Candidate Diagnostic Biomarker for Malignant Mesothelioma. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:9280170. doi: 10.1155/2017/9280170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Santi C, Melaiu O, Bonotti A, et al. Deregulation of miRNAs in malignant pleural mesothelioma is associated with prognosis and suggests an alteration of cell metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3140. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greening DW, Ji H, Chen M, et al. Secreted primary human malignant mesothelioma exosome signature reflects oncogenic cargo. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32643. doi: 10.1038/srep32643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creaney J, Dick IM, Leon JS, et al. A Proteomic Analysis of the Malignant Mesothelioma Secretome Using iTRAQ. Cancer genomics & proteomics. 2017;14:103–117. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak AK, Chansky K, Rice DC, et al. The IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project: Proposals for Revisions of the T Descriptors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Pleural Mesothelioma. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11:2089–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusch VW, Chansky K, Kindler HL, et al. The IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project: Proposals for the M Descriptors and for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Mesothelioma. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11:2112–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pass H, Giroux D, Kennedy C, et al. The IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project: Improving Staging of a Rare Disease Through International Participation. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2016;11:2082–2088. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armato SG, 3rd, Li P, Husain AN, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of mesothelioma tumor volume. Lung Cancer. 2015;87:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ak G, Metintas M, Metintas S, et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of chemotherapy response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. European journal of radiology. 2010;74:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armato SG, 3rd, Oxnard GR, Kocherginsky M, et al. Evaluation of semiautomated measurements of mesothelioma tumor thickness on CT scans. Academic radiology. 2005;12:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frauenfelder T, Tutic M, Weder W, et al. Volumetry: an alternative to assess therapy response for malignant pleural mesothelioma? The European respiratory journal. 2011;38:162–168. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F, Zhao B, Krug LM, et al. Assessment of therapy responses and prediction of survival in malignant pleural mesothelioma through computer-aided volumetric measurement on computed tomography scans. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2010;5:879–884. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181dd0ef1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plathow C, Schoebinger M, Fink C, et al. Quantification of lung tumor volume and rotation at 3D dynamic parallel MR imaging with view sharing: preliminary results. Radiology. 2006;240:537–545. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401050727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labby ZE, Armato SG, 3rd, Dignam JJ, et al. Lung volume measurements as a surrogate marker for patient response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2013;8:478–486. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828354c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaisaowong K, Aach T, Jager P, et al. Computer-assisted diagnosis for early stage pleural mesothelioma: towards automated detection and quantitative assessment of pleural thickening from thoracic CT images. Methods of information in medicine. 2007;46:324–331. doi: 10.1160/ME9050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sensakovic WF, Armato SG, 3rd, Straus C, et al. Computerized segmentation and measurement of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Medical physics. 2011;38:238–244. doi: 10.1118/1.3525836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labby ZE, Nowak AK, Dignam JJ, et al. Disease volumes as a marker for patient response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2013;24:999–1005. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy DJ, Gill RR. Volumetric assessment in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2017:5. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.05.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noonan SA, Berry L, Lu X, et al. Identifying the Appropriate FISH Criteria for Defining MET Copy Number-Driven Lung Adenocarcinoma through Oncogene Overlap Analysis. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rusch VW, Gill R, Mitchell A, et al. A Multicenter Study of Volumetric Computed Tomography for Staging Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2016;102:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.06.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Perrot M, Dong Z, Bradbury P, et al. Impact of tumour thickness on survival after radical radiation and surgery in malignant pleural mesothelioma. The European respiratory journal. 2017:49. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01428-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perrot M, Wu L, Wu M, et al. Radiotherapy for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18:e532–e542. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30459-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen M, Helm E, Joshi N, et al. Computer-aided volumetric assessment of malignant pleural mesothelioma on CT using a random walk-based method. International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery. 2017;12:529–538. doi: 10.1007/s11548-016-1511-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo Z, Carbone M, Zhang X, et al. Improving the Accuracy of Mesothelioma Diagnosis in China. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amatya VJ, Kushitani K, Mawas AS, et al. MUC4, a novel immunohistochemical marker identified by gene expression profiling, differentiates pleural sarcomatoid mesothelioma from lung sarcomatoid carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:672–681. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carbone M, Flores EG, Emi M, et al. Combined Genetic and Genealogic Studies Uncover a Large BAP1 Cancer Syndrome Kindred Tracing Back Nine Generations to a Common Ancestor from the 1700s. PLoS genetics. 2015;11:e1005633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berg KB, Churg A. GATA3 Immunohistochemistry for Distinguishing Sarcomatoid and Desmoplastic Mesothelioma From Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1221–1225. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuraoka M, Amatya VJ, Kushitani K, et al. Identification of DAB2 and Intelectin-1 as Novel Positive Immunohistochemical Markers of Epithelioid Mesothelioma by Transcriptome Microarray Analysis for Its Differentiation From Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1045–1052. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hida T, Hamasaki M, Matsumoto S, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of MTAP and BAP1 protein loss for mesothelioma diagnosis: Comparison with 9p21 FISH and BAP1 immunohistochemistry. Lung Cancer. 2017;104:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valmary-Degano S, Colpart P, Villeneuve L, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of two antibodies against PD-L1 and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in epithelioid peritoneal malignant mesothelioma: A RENAPE study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1915–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansour MSI, Seidal T, Mager U, et al. Determination of PD-L1 expression in effusions from mesothelioma by immuno-cytochemical staining. Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cncy.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thapa B, Salcedo A, Lin X, et al. The Immune Microenvironment, Genome-wide Copy Number Aberrations, and Survival in Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inaguma S, Lasota J, Wang Z, et al. Expression of ALCAM (CD166) and PD-L1 (CD274) independently predicts shorter survival in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Human Pathology. 2018;71:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schurch CM, Forster S, Bruhl F, et al. The “don’t eat me” signal CD47 is a novel diagnostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target for diffuse malignant mesothelioma. Oncoimmunology. 2017;7:e1373235. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1373235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48:407–416. doi: 10.1038/ng.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yap TA, Aerts JG, Popat S, et al. Novel insights into mesothelioma biology and implications for therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:475–488. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1022–1025. doi: 10.1038/ng.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu J, Kadariya Y, Cheung M, et al. Germline mutation of Bap1 accelerates development of asbestos-induced malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4388–4397. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Napolitano A, Pellegrini L, Dey A, et al. Minimal asbestos exposure in germline BAP1 heterozygous mice is associated with deregulated inflammatory response and increased risk of mesothelioma. Oncogene. 2016;35:1996–2002. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carbone M, Ferris LK, Baumann F, et al. BAP1 cancer syndrome: malignant mesothelioma, uveal and cutaneous melanoma, and MBAITs. J Transl Med. 2012;10:179. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haugh AM, Njauw CN, Bubley JA, et al. Genotypic and Phenotypic Features of BAP1 Cancer Syndrome: A Report of 8 New Families and Review of Cases in the Literature. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:999–1006. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carbone M, Yang H, Pass HI, et al. BAP1 and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nrc3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nasu M, Emi M, Pastorino S, et al. High Incidence of Somatic BAP1 alterations in sporadic malignant mesothelioma. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10:565–576. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshikawa Y, Emi M, Hashimoto-Tamaoki T, et al. High-density array-CGH with targeted NGS unmask multiple noncontiguous minute deletions on chromosome 3p21 in mesothelioma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:13432–13437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612074113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joseph NM, Chen YY, Nasr A, et al. Genomic profiling of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma reveals recurrent alterations in epigenetic regulatory genes BAP1, SETD2, and DDX3X. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:246–254. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leblay N, Lepretre F, Le Stang N, et al. BAP1 Is Altered by Copy Number Loss, Mutation, and/or Loss of Protein Expression in More Than 70% of Malignant Peritoneal Mesotheliomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:724–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bononi A, Giorgi C, Patergnani S, et al. BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca2+ flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature. 2017;546:549–553. doi: 10.1038/nature22798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bononi A, Yang H, Giorgi C, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations induce a Warburg effect. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1694–1704. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hebert L, Bellanger D, Guillas C, et al. Modulating BAP1 expression affects ROS homeostasis, cell motility and mitochondrial function. Oncotarget. 2017;8:72513–72527. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parrotta R, Okonska A, Ronner M, et al. A Novel BRCA1-Associated Protein-1 Isoform Affects Response of Mesothelioma Cells to Drugs Impairing BRCA1-Mediated DNA Repair. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1309–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Betti M, Casalone E, Ferrante D, et al. Germline mutations in DNA repair genes predispose asbestos-exposed patients to malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Lett. 2017;405:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin M, Zhang L, Hildebrandt MAT, et al. Common, germline genetic variations in the novel tumor suppressor BAP1 and risk of developing different types of cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:74936–74946. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rizzardi C, Athanasakis E, Cammisuli F, et al. Puzzling Results from BAP1 Germline Mutations Analysis in a Group of Asbestos-Exposed Patients in a High-risk Area of Northeast Italy. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3073–3083. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baumann F, Flores E, Napolitano A, et al. Mesothelioma patients with germline BAP1 mutations have 7-fold improved long-term survival. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:76–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang LM, Shi ZW, Wang JL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of BRCA1-associated protein 1 in malignant mesothelioma: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:68863–68872. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCroskey Z, Staerkel G, Roy-Chowdhuri S. Utility of BRCA1-associated protein 1 immunoperoxidase stain to differentiate benign versus malignant mesothelial proliferations in cytologic specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:312–319. doi: 10.1002/dc.23683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shinozaki-Ushiku A, Ushiku T, Morita S, et al. Diagnostic utility of BAP1 and EZH2 expression in malignant mesothelioma. Histopathology. 2017;70:722–733. doi: 10.1111/his.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McGregor SM, McElherne J, Minor A, et al. BAP1 immunohistochemistry has limited prognostic utility as a complement of CDKN2A (p16) fluorescence in situ hybridization in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Hum Pathol. 2017;60:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chapel DB, Husain AN, Krausz T, et al. PAX8 Expression in a Subset of Malignant Peritoneal Mesotheliomas and Benign Mesothelium has Diagnostic Implications in the Differential Diagnosis of Ovarian Serous Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vivero M, Bueno R, Chirieac LR. Clinicopathologic and genetic characteristics of young patients with pleural diffuse malignant mesothelioma. Modern Pathology. 2017;31:122. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Desmeules P, Joubert P, Zhang L, et al. A Subset of Malignant Mesotheliomas in Young Adults Are Associated With Recurrent EWSR1/FUS-ATF1 Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:980–988. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hung YP, Dong F, Watkins JC, et al. Identification of ALK Rearrangements in Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. JAMA Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Strizzi L, Catalano A, Vianale G, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine growth factor in human malignant mesothelioma. J Pathol. 2001;193:468–475. doi: 10.1002/path.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Robinson BW, Lake RA. Advances in malignant mesothelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–1603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Masood R, Kundra A, Zhu S, et al. Malignant mesothelioma growth inhibition by agents that target the VEGF and VEGF-C autocrine loops. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:603–610. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Filho AL, Baltazar F, Bedrossian C, et al. Immunohistochemical expression and distribution of VEGFR-3 in malignant mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:786–791. doi: 10.1002/dc.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1405–1414. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhan M, Zheng H, Xu T, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of additional bevacizumab to pemetrexed plus cisplatin for malignant pleural mesothelioma based on the MAPS trial. Lung Cancer. 2017;110:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grosso F, Steele N, Novello S, et al. Nintedanib Plus Pemetrexed/Cisplatin in Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Phase II Results From the Randomized, Placebo-Controlled LUME-Meso Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3591–3600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.9012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scagliotti GV, Gaafar R, Nowak AK, et al. LUME-Meso: Design and Rationale of the Phase III Part of a Placebo-Controlled Study of Nintedanib and Pemetrexed/Cisplatin Followed by Maintenance Nintedanib in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18:589–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Maio M, et al. Four-year survival rates for patients with metastatic melanoma who received ipilimumab in phase II clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2174–2180. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Tremelimumab for patients with chemotherapy-resistant advanced malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Efficacy and safety of an intensified schedule of tremelimumab for chemotherapy-resistant malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:301–309. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maio M, Scherpereel A, Calabro L, et al. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1261–1273. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chee SJ, Lopez M, Mellows T, et al. Evaluating the effect of immune cells on the outcome of patients with mesothelioma. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nguyen BH, Montgomery R, Fadia M, et al. PD-L1 expression associated with worse survival outcome in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ajco.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mansfield AS, Roden AC, Peikert T, et al. B7-H1 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma is associated with sarcomatoid histology and poor prognosis. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2014;9:1036–1040. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Patil NS, Righi L, Koeppen H, et al. Molecular and Histopathological Characterization of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Advanced Stage of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.09.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375:1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reck M. Pembrolizumab as first-line therapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:93–105. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, et al. Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17:1497–1508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30498-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cedres S, Ponce-Aix S, Zugazagoitia J, et al. Analysis of expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alley EW, Lopez J, Santoro A, et al. Clinical safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): preliminary results from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18:623–630. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Quispel-Janssen J, Zago G, Schouten R, et al. OA13.01 A Phase II Study of Nivolumab in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (NivoMes): with Translational Research (TR) Biopies. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12:S292–S293. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hassan R, Thomas A, Patel MR, et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) in patients with advanced unresectable mesothelioma from the JAVELIN solid tumor phase Ib trial: Safety, clinical activity, and PD-L1 expression. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:8503–8503. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kindler H, Karrison T, Carol Tan Y-H, et al. OA13.02 Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Malignant Mesothelioma (MM): Interim Analysis. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12:S293–S294. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goto Y, Okada M, Kijima T, et al. MA 19.01 A Phase II Study of Nivolumab: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Single Arm Study in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MERIT) Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12:S1883. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Calabro L, Morra A, Giannarelli D, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with durvalumab in first or second-line mesothelioma patients: Safety analysis from the phase II NIBIT-MESO-1 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35:8558–8558. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Scherpereel A, Mazieres J, Greillier L, et al. Second- or third-line nivolumab (Nivo) versus nivo plus ipilimumab (Ipi) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patients: Results of the IFCT-1501 MAPS2 randomized phase II trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35:LBA8507–LBA8507. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Disselhorst M, Harms E, Van Tinteren H, et al. OA 02.02 Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in the Treatment of Recurrent Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Phase II Study. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12:S1746. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zalcman G, Peters S, Mansfield AS, et al. Checkmate 743: A phase 3, randomized, open-label trial of nivolumab (nivo) plus ipilimumab (ipi) vs pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin as first-line therapy in unresectable pleural mesothelioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35:TPS8581–TPS8581. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nowak A, Kok P-S, Livingstone A, et al. P2.06-025 DREAM - A Phase 2 Trial of DuRvalumab with First Line chEmotherApy in Mesothelioma with a Safety Run In: Topic: Mesothelioma and SCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12:S1086–S1087. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Serrels A, Lund T, Serrels B, et al. Nuclear FAK controls chemokine transcription, Tregs, and evasion of anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 2015;163:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jiang H, Hegde S, Knolhoff BL, et al. Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nature medicine. 2016;22:851–860. doi: 10.1038/nm.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.LaFave LM, Beguelin W, Koche R, et al. Loss of BAP1 function leads to EZH2-dependent transformation. Nature medicine. 2015;21:1344–1349. doi: 10.1038/nm.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bononi A, Giorgi C, Patergnani S, et al. BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca(2+) flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature. 2017;546:549–553. doi: 10.1038/nature22798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yu H, Pak H, Hammond-Martel I, et al. Tumor suppressor and deubiquitinase BAP1 promotes DNA double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:285–290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309085110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Morello A, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Mesothelin-Targeted CARs: Driving T Cells to Solid Tumors. Cancer discovery. 2016;6:133–146. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pastan I, Hassan R. Discovery of mesothelin and exploiting it as a target for immunotherapy. Cancer research. 2014;74:2907–2912. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]