Abstract

Background

Growing evidence has indicated that tumor biomarkers, including cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21–1 (Cyfra21–1), carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9), carbohydrate antigen 72–4 (CA72–4), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-Ag) were reported to be commonly used in diagnosis and prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). However, which is the best marker for predicting prognosis remains unknown. Few papers focused on the relationship between tumor biomarkers and postoperative treatment in ESCC.

Methods

A total of 416 ESCC patients were enrolled in this study. The association between tumor markers and overall survival (OS) was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test, followed by multivariate Cox regression models.

Results

The results of Cox multivariate analysis indicated that among these tumor biomarkers, CA19–9 (≥ 37 vs. < 37) [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.130, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.138–3.986, p = 0.018] and CEA (≥ 5 vs. < 5) (HR = 1.827, 95% CI = 1.089–3.064, p = 0.022) were the independent prognostic factors of poor OS. For the ESCC patients with CA19–9 < 37, CEA < 5 or SCC-Ag < 1.5, the surgery plus postoperative chemotherapy group had a significantly longer OS than the surgery group alone (p < 0.05), but this significant difference of OS between these two groups cannot be found in patients with CA19–9 ≥ 37, CEA ≥ 5 or SCC-Ag ≥ 1.5 (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

CEA and CA19–9 maybe are superior to other tumor biomarkers as prognostic indicators in ESCC. CA19–9, CEA, SCC-Ag may be useful in predicting the therapeutic effect of postoperative chemotherapy in ESCC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12885-019-5755-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Prognosis, Postoperative chemotherapy, Therapeutic effect; tumor biomarker

Background

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, it is the third leading cancer in incidence and fourth in mortality in China [1]. Most of esophageal cancers are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [2, 3]. Despite the development of multidisciplinary treatment in ESCC, the prognosis of patients still remains poor [4]. To date, TNM staging system has been regarded as the primary factor in predicting prognosis for ESCC. However, ESCC patients with the same TNM stage often have different clinical outcomes. Therefore, it is very important to explore dependable prognostic factors to accurately predict the prognosis of patients with ESCC and even guide a personalized treatment.

At present, tumor-related proteins could be generated and secreted into the peripheral circulation in some cancers, and can be detected [5]. In the clinic, these peripheral proteins are usually regarded as tumor makers for non-invasive diagnostic tools to identify cancer, as well as predictor of prognosis and therapeutic effect. Until now, cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21–1 (Cyfra21–1), carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9), carbohydrate antigen 72–4 (CA72–4), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-Ag) have been reported to be commonly used in diagnosis and as prognostic predictors of a variety of cancers [6–11], including ESCC [5, 12, 13]. However, which is the best tumor biomarker for the predicting prognosis in patients with ESCC remains unknown. On the other hand, few papers have focused on the relationship between tumor biomarkers and postoperative treatment in ESCC.

In this study, we analyzed the association between the clinicopathological factors of ESCC patients and these tumor biomarkers. We also explored the prognostic value of these tumor biomarkers and compared their capacity for predicting prognosis in ESCC. Moreover, the association between tumor biomarkers and postoperative chemotherapy was explored in our study.

Methods

Patient cohort

We retrospectively reviewed a cohort of resectable ESCC patients who underwent resection at the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital between March 2007 and December 2012. Patients who were diagnosed as ESCC by histopathology after operation and whose serum tumor markers were obtained before breakfast within 2 weeks before surgery were included in this study. Patients who received any neoadjuvant treatment before surgery or patients with another kind of cancer were excluded. A total of 416 ESCC patients were enrolled in this study. The median follow-up was 42 months (range 2–101). Clinical data of ESCC patients, including sex, age and date of surgery, clinicopathological factors (including tumor length, differentiation and TNM stage), and preoperative serum tumor markers testing result, were obtained from the medical records. Surgery was performed by experienced surgeons. Transthoracic esophagectomy with two or three-field lymph node resection was the method of choice based on the location of tumor and clinical stage. The esophagus was dissected en bloc along with its adjacent mediastinal tissue, including lymph nodes, mediastinal pleura, the thoracic duct and azygos vein. Each marker was performed on the same machine (Roche E170 modular immunoassay analyzer, USA) independently. According to the manufacturer’s protocols and previous study [5, 12, 14–16], the normal upper limits were used as the optimal cut-off values of CA19–9, CA72–4, CEA, Cyfra21–1 and SCC-Ag: 37 U/ml, 6 U/ml, 5 μg/L, 3.4 ng/ml and 1.5 ng/ml, respectively. The ESCC stage was classified according to the 7th of the AJCC/UICC TNM classification system.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to analyze the association between clinicopathological factors and these tumor biomarkers. The overall survival (OS) was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences of variables were compared using log-rank tests. Univariate and multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional hazard regression model were used to evaluate prognostic factors. All confidence intervals (CIs) were stated at the 95%.

SPSS software version 22.0 was used to assess the statistical analyses in our study. A p-value of less than 0.05 from a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics

Among 416 patients with ESCC, 333 (80.0%) were male and 83 (20.0%) were Female. The median age was 60 years (Range 33–82). Tumors of 164 (39.4%) patients were diagnosed < 4.0 cm, while 252 (60.6%) were diagnosed ≥4.0 cm. Most patients (336, 80.8%) were diagnosed as well or moderate differentiation of ESCC, while 80 (19.2%) ESCC patients were diagnosed as poor differentiation. According to 7th of TNM tumor classification system, I, II and III stage distributions of ESCC cases were 22 (5.3%), 128 (30.8%), 266 (63.9%), respectively. On the other hand, 250 (60.1%) patients with ESCC received postoperative chemotherapy, 202 patients received a regimen of 5-FU plus platinum, the remaining patients received the regimen of paclitaxel plus platinum (26/250), or an irregular regimen (22/250), while 166 (39.9%) patients did not receive any postoperative chemotherapy. The patients’ baseline characteristics and patients’ clinicopathological factors divided by CA19–9, CA72–4, CEA, Cyfra21–1 and SCC-Ag were described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationship between clinicopathological features and tumor biomarkers in ESCC

| Variable | CA19–9 (U/ml) | CA72–4 (U/ml) | CEA (ug/L) | Cyfra21–1 (ng/ml) | SCC-Ag (ng/ml) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 37(%) | ≥37(%) | p | < 6(%) | ≥6(%) | p | < 5(%) | ≥5(%) | p | < 3.4(%) | ≥3.4(%) | p | < 1.5(%) | ≥1.5(%) | p | |

| Age(y) | 0.613 | 0.806 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.215 | ||||||||||

| < 60 | 187 (46.6) | 6 (40.0) | 177 (46.6) | 16 (44.4) | 190 (47.7) | 3 (16.7) | 157 (49.8) | 36 (35.6) | 156 (48.0) | 37 (40.7) | |||||

| ≥ 60 | 214 (53.4) | 9 (60.0) | 203 (53.4) | 20 (55.6) | 208 (52.3) | 15 (83.3) | 158 (50.2) | 65 (64.4) | 169 (52.0) | 54 (59.3) | |||||

| Gender | 0.507 | 0.606 | 0.721 | 0.271 | 0.349 | ||||||||||

| Male | 322 (80.3) | 11 (73.3) | 303 (79.7) | 30 (83.3) | 318 (79.9) | 15 (83.3) | 256 (81.3) | 77 (76.2) | 257 (79.1) | 76 (83.5) | |||||

| Female | 79 (19.7) | 4 (26.7) | 77 (20.3) | 6 (16.7) | 80 (20.1) | 3 (16.7) | 59 (18.7) | 24 (23.8) | 68 (20.9) | 15 (16.5) | |||||

| Tumor length | 0.117 | 0.015 | 0.127 | 0.067 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| < 4 | 161 (40.1) | 3 (20.0) | 143 (37.6) | 21 (58.3) | 160 (40.2) | 4 (22.2) | 132 (41.9) | 32 (31.7) | 143 (44.0) | 21 (23.1) | |||||

| ≥ 4 | 240 (59.9) | 12 (80.0) | 237 (62.4) | 15 (41.7) | 238 (59.8) | 14 (77.8) | 183 (58.1) | 69 (68.3) | 182 (56.0) | 70 (76.9) | |||||

| Tumor location | 0.842 | 0.461 | 0.930 | 0.594 | 0.369 | ||||||||||

| Upper | 32 (8.0) | 1 (6.7) | 29 (7.6) | 4 (11.1) | 32 (8.0) | 1 (5.6) | 27 (8.6) | 6 (5.9) | 29 (8.9) | 4 (4.4) | |||||

| Middle | 237 (59.1) | 10 (66.7) | 229 (60.3) | 18 (50.0) | 236 (59.3) | 11 (61.1) | 188 (59.7) | 59 (58.4) | 191 (58.8) | 56 (61.5) | |||||

| Lower | 132 (32.9) | 4 (26.7) | 122 (32.1) | 14 (38.9) | 130 (32.7) | 6 (33.3) | 100 (31.7) | 36 (35.6) | 105 (32.3) | 31 (34.1) | |||||

| Differentiation | 0.555 | 0.634 | 0.372 | 0.299 | 0.050 | ||||||||||

| Well-moderate | 323 (80.5) | 13 (86.7) | 308 (81.1) | 28 (77.8) | 320 (80.4) | 16 (88.9) | 258 (81.9) | 78 (77.2) | 256 (78.8) | 80 (87.9) | |||||

| Poor | 78 (19.5) | 2 (13.3) | 72 (18.9) | 8 (22.2) | 78 (19.6) | 2 (11.1) | 57 (18.1) | 23 (22.8) | 69 (21.2) | 11 (12.1) | |||||

| pT category | 0.475 | 0.679 | 0.467 | 0.355 | 0.051 | ||||||||||

| pT1 | 25 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (6.1) | 2 (5.6) | 25 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 22 (7.0) | 3 (3.0) | 22 (6.8) | 3 (3.3) | |||||

| pT2 | 100 (24.9) | 2 (13.3) | 92 (24.2) | 10 (27.8) | 99 (24.9) | 3 (16.7) | 80 (25.4) | 22 (21.8) | 88 (27.1) | 14 (15.4) | |||||

| pT3 | 74 (18.5) | 3 (20.0) | 73 (19.2) | 4 (11.1) | 74 (18.6) | 3 (16.7) | 58 (18.4) | 19 (18.8) | 57 (17.5) | 20 (22.0) | |||||

| pT4 | 202 (50.4) | 10 (66.7) | 192 (50.5) | 20 (55.6) | 200 (50.3) | 12 (66.7) | 155 (49.2) | 57 (56.4) | 158 (48.6) | 54 (59.3) | |||||

| pN category | 0.280 | 0.443 | 0.001 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| pN0 | 210 (52.4) | 4 (26.7) | 199 (52.4) | 15 (41.7) | 211 (53.0) | 3 (16.7) | 176 (55.9) | 38 (37.6) | 184 (56.6) | 30 (33.0) | |||||

| pN1 | 141 (35.2) | 8 (53.3) | 132 (34.7) | 17 (47.2) | 139 (34.9) | 10 (55.6) | 105 (33.3) | 44 (43.6) | 111 (34.2) | 38 (41.8) | |||||

| pN2 | 33 (8.2) | 2 (13.3) | 33 (8.7) | 2 (5.6) | 30 (7.5) | 5 (27.8) | 24 (7.6) | 11 (10.9) | 20 (6.2) | 15 (16.5) | |||||

| pN3 | 17 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 16 (4.2) | 2 (5.6) | 18 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.2) | 8 (7.9) | 10 (3.1) | 8 (8.8) | |||||

| TNM stage | 0.361 | 0.773 | 0.075 | 0.070 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| I | 22 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (5.5) | 1 (2.8) | 22 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (6.3) | 2 (2.0) | 21 (6.5) | 1 (1.1) | |||||

| II | 125 (31.2) | 3 (20.0) | 117 (30.8) | 11 (30.6) | 126 (31.7) | 2 (11.1) | 102 (32.4) | 26 (25.7) | 112 (34.5) | 16 (17.6) | |||||

| III | 254 (63.3) | 12 (80.0) | 242 (63.7) | 24 (66.7) | 250 (62.8) | 16 (88.9) | 193 (61.3) | 73 (72.3) | 192 (59.1) | 74 (81.3) | |||||

| PC | 0.994 | 0.400 | 0.928 | 0.088 | 0.575 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 241 (60.1) | 9 (60.0) | 226 (59.5) | 24 (66.7) | 239 (60.1) | 11 (61.1) | 182 (57.8) | 68 (67.3) | 193 (59.4) | 57 (62.6) | |||||

| No | 160 (39.9) | 6 (40.0) | 154 (40.5) | 12 (33.3) | 159 (39.9) | 7 (38.9) | 133 (42.2) | 33 (32.7) | 132 (40.6) | 34 (37.4) | |||||

Abbreviations: CA carbohydrate antigen, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, PC postoperative chemotherapy, SCC-Ag squamous cell carcinoma antigen

Our results showed that the high CEA and Cyfra21–1 were both significantly associated with older age and more advanced pN stage (p < 0.05), elevated SCC-Ag was significantly related to larger tumor size, more advanced pN stage and TNM stage, and CA72–4 was significantly associated with tumor size (p < 0.05). While no statistically significant association was observed between CA19–9 and any clinicopathological factors.

Prognostic value of tumor biomarkers

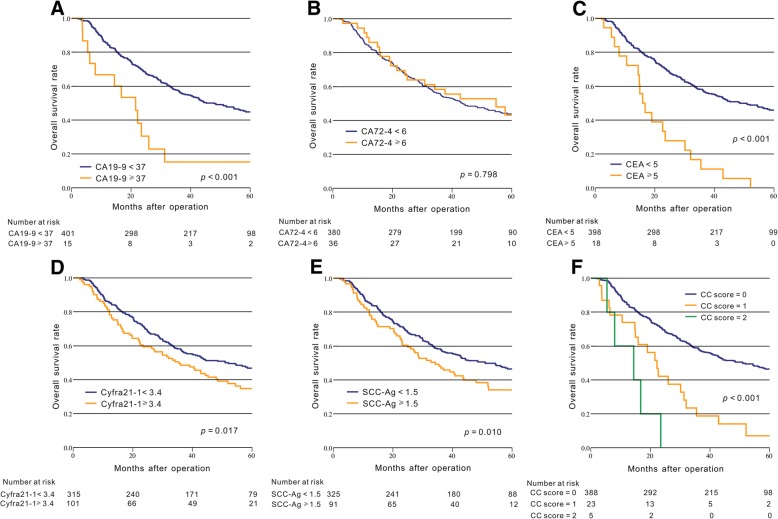

In our study, Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank tests and univariate analysis were used to assess the association between the prognosis of ESCC patients and tumor biomarkers. In univariate analysis, our result indicated that male patients, larger tumor size, advanced pT stage, advanced pN stage, advanced TNM stage, patients who did not receive postoperative chemotherapy and elevated CA19–9, CEA, Cyfra21–1 and SCC-Ag were significantly related to poor OS (p < 0.05, Fig. 1a-e, Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of the overall survival in patients with ESCC based on tumor biomarkers. a: CA 19–9; b: CA72–4; c: CEA; d: Cyfra21–1; e: SCC-Ag; f: CC score

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate survival analyses for overall survival in ESCC patients

| Variable | Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age(y) | 0.362 | |||

| < 60 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 60 | 1.127 (0.871–1.459) | |||

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.010 | ||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.630 (0.441–0.898) | 0.624 (0.435–0.894) | ||

| Tumor length (cm) | < 0.001 | 0.257 | ||

| < 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 4 | 1.665 (1.266–2.190) | 1.182 (0.885–1.579) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.772 | |||

| Upper | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.085 (0.672–1.752) | |||

| Lower | 0.983 (0.594–1.627) | |||

| Differentiation | 0.982 | |||

| Well - moderate | 1 | |||

| Poor | 1.004 (0.725–1.390) | |||

| pT category | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 2.000 (0.786–5.090) | 1.893 (0.739–4.847) | ||

| T3 | 3.456 (1.365–8.747) | 3.017 (1.171–7.772) | ||

| T4 | 5.604 (2.297–13.671) | 4.674 (1.887–11.577) | ||

| pN category | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| pN0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| pN1 | 2.469 (1.856–3.286) | 2.331 (1.732–3.316) | ||

| pN2 | 2.801 (1.805–4.347) | 2.949 (1.840–4.725) | ||

| pN3 | 3.487 (2.015–6.035) | 3.461 (1.960–6.109) | ||

| TNM stage | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 1 | |||

| II | 1.974 (0.709–5.500) | |||

| III | 6.010 (2.231–16.192) | |||

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 0.015 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 1.376 (1.063–1.780) | 1.935 (1.468–2.549) | ||

| CA19–9 | 0.001 | 0.018 | ||

| < 37 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 37 | 2.754 (1.535–4.938) | 2.130 (1.138–3.986) | ||

| CA72–4 | 0.799 | |||

| < 6 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 6 | 0.942 (0.596–1.490) | |||

| CEA | < 0.001 | 0.022 | ||

| < 5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 3.512 (2.159–5.713) | 1.827 (1.089–3.064) | ||

| Cyfra21–1 | 0.018 | 0.166 | ||

| < 3.4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 3.4 | 1.409 (1.061–1.871) | 1.238 (0.915–1.676) | ||

| SCC-Ag | 0.010 | 0.631 | ||

| < 1.5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 1.5 | 1.472 (1.096–1.975) | 0.926 (0.677–1.267) | ||

Abbreviations: CA carbohydrate antigen, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CI confidence interval, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, HR hazard ratio, SCC-Ag squamous cell carcinoma antigen

In Cox multivariate analysis, the result showed that male patients, advanced pT stage, advanced pN stage, advanced TNM stage and patients who did not receive postoperative chemotherapy were significantly associated with poor OS (p < 0.05, Table 2). Among these tumor biomarkers, CA19–9 (≥ 37 vs. < 37) [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.130, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.138–3.986, p = 0.018] and CEA (≥ 5 vs. < 5) (HR = 1.827, 95% CI = 1.089–3.064, p = 0.022) were the independent prognostic factors of poor OS (Table 2).

According to the result of Cox multivariate analysis, we proposed a novel prognostic biomarker based on a combination of CEA and CA199 levels. Patients were assigned a CEA + CA199 score (CC score) of 0, 1, or 2 based on the presence of elevated CEA (> 5 μg/L), elevated CA199 (> 37 U/ml), or both, as follows: patients with both elevated CEA and CA199 were assigned a score of 2, and patients with either or neither were assigned a score of 1 or 0, respectively. The result showed that high CC score was significantly associated with poor OS (p < 0.001, Fig. 1f).

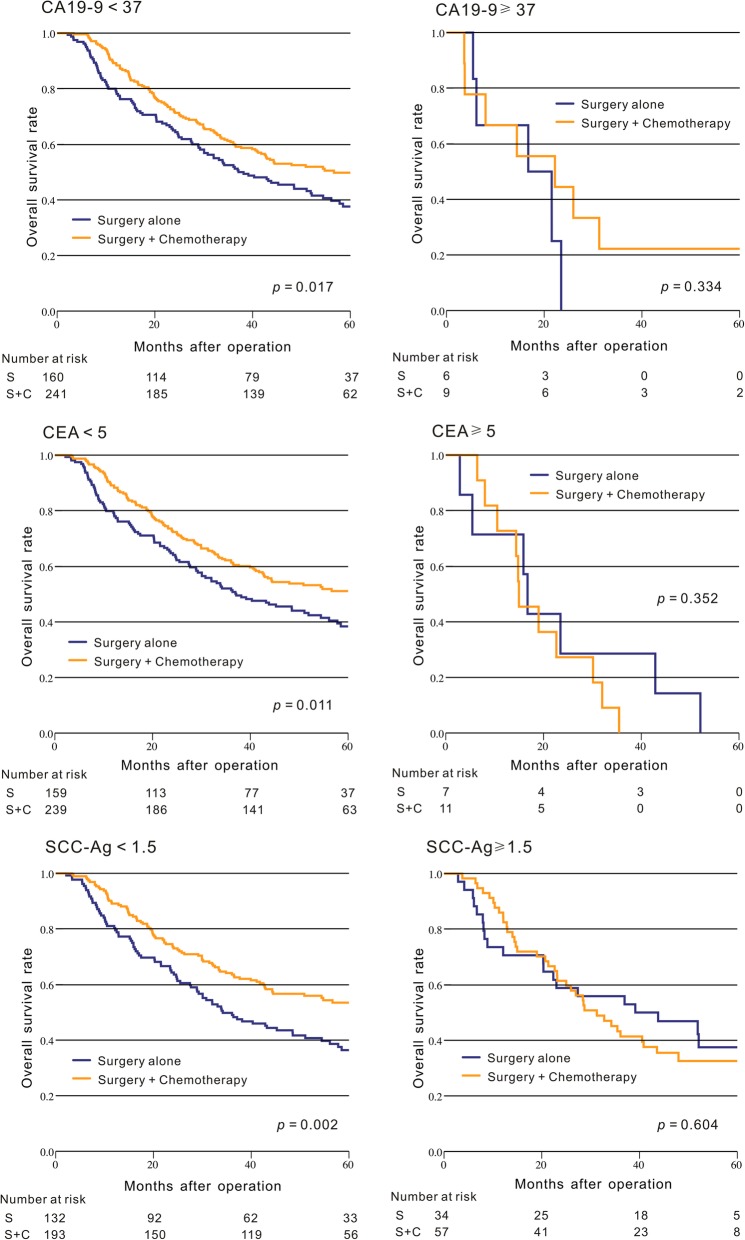

Tumor biomarkers and postoperative chemotherapy

In our study, we also explored the relationship between these tumor biomarkers and the therapeutic effect of postoperative chemotherapy. Our result indicated that for the ESCC patients with CA19–9 < 37 U/ml, CEA < 5 μg/L or SCC-Ag < 1.5 ng/ml, the surgery plus postoperative chemotherapy group had a significantly longer OS than the surgery group alone (p < 0.05, Fig. 2), but this significant difference of OS between these two groups cannot be found in patients with CA19–9 ≥ 37 U/ml, CEA ≥ 5 μg/L or SCC-Ag ≥ 1.5 ng/ml (p > 0.05, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival between the surgery plus chemotherapy group and the surgery group alone in ESCC patients based on CA19–9, CEA, and SCC-Ag

On the other hand, regardless of patients with CA72–4 < 6 U/ml or CA72–4 ≥ 6 U/ml, or in patients with Cyfra21–1 < 3.4 ng/ml or Cyfra21–1 ≥ 3.4 ng/ml, our results showed that the surgery plus chemotherapy group had significantly longer or a tendency of longer OS than the surgery group alone (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

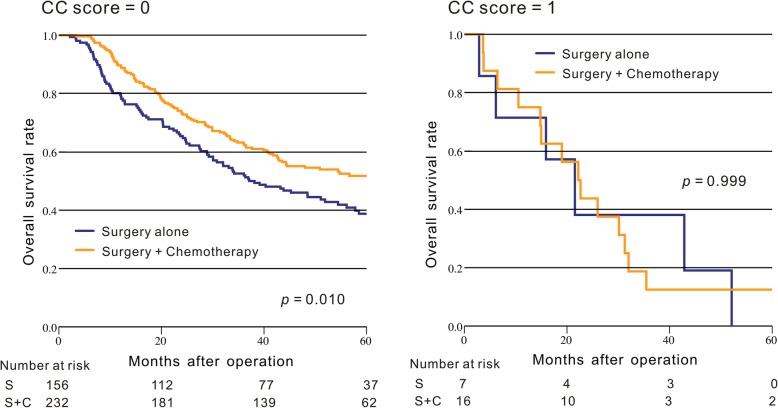

We also explored the correlation of CC score with the response of chemotherapy. The result indicated that for the ESCC patients with CC score = 0, the surgery plus postoperative chemotherapy group had a significantly longer OS than the surgery group alone (p = 0.010, Fig. 3), However, this significant difference of OS between these two groups cannot be observed in patients with CC score = 1 (p = 0.999, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival between the surgery plus chemotherapy group and the surgery group alone in ESCC patients based on CC score

Discussion

Though developments in surgery, chemotherapy and target therapy have improved the prognosis of ESCC patients, the long-term survival still remains unsatisfactory [4, 17]. It is well known that TNM staging system has been regarded as the primary predictor for prognosis and as the foundation for guiding the treatment. However, this staging system also has its own limitation because the clinical prognosis varies widely even in ESCC patients with the same stage [4]. A dependable and accurate prognostic biomarker for patients with ESCC is required to identify high-risk patients with poor prognosis.

Until now, there is no agreement regarding which tumor biomarker is the best predictors for prognosis in patients with ESCC. Some studies indicated that Cyfra21–1 was better than CEA as a predictor of OS for prognosis in ESCC [12, 18], Cao et al. found that Cyfra21–1 and SCC-Ag were both independently significant poor predictors of prognosis in patients with stage II ESCC [5]. In another study, the result showed that SCC-Ag was a better prognostic serum biomarker than CEA [19]. While Kosugi reported that SCC-Ag was superior to CEA and CA19–9 as a predictor for OS in esophageal cancer patients [14]. In this study, our results showed that CA19–9 and CEA were the only two independent prognostic indicators for poor OS among these five tumor biomarkers. These aforementioned results showed that CA19–9 and CEA maybe were potentially superior to other tumor biomarkers as indicators for predicting prognosis in ESCC patients. The results need to be confirmed by larger, more homogeneous studies.

On the other hand, according to the result of Cox multivariate analysis, we proposed a novel prognostic biomarker CC score based on a combination of CEA and CA199 levels. The result indicated that high CC score was significantly associated with poor OS and CC score might show more potent prognostic value in ESCC patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to incorporate CA19–9 and CEA together to evaluate whether the combination of these two biomarkers could present a predictive value for survival outcome of ESCC patients.

But until now, few studies focused on the association between tumor biomarkers and therapeutic effect of treatment in ESCC. Some studies reported that CYFRA21-1 and CEA may be helpful in predicting the sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy in patients with ESCC [20, 21]. Okamura et.al reported that ESCC patients with cT3 tumors in the noncurative group were more likely to have higher serum SCC-Ag [22]. Our study is the first study to report the relationship between tumor biomarkers and therapeutic effect of postoperative chemotherapy in ESCC. Our result indicated that ESCC patients with low CA19–9, CEA, SCC-Ag may be more likely to benefit from the postoperative chemotherapy. In addition, we also explored the association between CC score and the therapeutic effect of postoperative chemotherapy and found that ESCC patients with CC score = 0 may be more likely to benefit from the postoperative chemotherapy. Thus, these preoperative tumor biomarkers may guide the postoperative treatment in ESCC. Given relatively small sample in the group of CEA ≥ 5 μg/L and CA19–9 ≥ 37 U/ml, the result should be confirmed in large-scale sample studies.

Several limitations exist in our study. First, this study was retrospective and our results were based on a single institution experience with a relatively small sample. A multiple-center and large-scale sample study is needed to confirm these results in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, CEA and CA19–9 maybe are superior to other tumor biomarkers as prognostic indicators in ESCC. Moreover, CA19–9, CEA, SCC-Ag may be used in predicting the therapeutic effect of postoperative chemotherapy in ESCC.

Additional file

Figure S1. Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival between the surgery plus chemotherapy group and the surgery group alone in ESCC patients based on CA72–4 and Cyfra21–1. (TIF 2027 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital. We also express our thanks to Carly Isabelle for her helpful English editing.

Abbreviations

- CA19–9

carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CA72–4

carbohydrate antigen 72–4

- CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CI

confidence intervals

- Cyfra21–1

cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21–1

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- OS

overall survival

- SCC-Ag

squamous cell carcinoma antigen

Authors’ contributions

Contributing to the conception and design: YCY and YB; the acquisition and analysis: YCY, XZH, LKZ and MB; interpretation of data: TD, TN, HLL and RL; the creation of new software used in the work: LZ, HYZ and HLL; Drafting the article: XZH, LKZ and TD; Revising it critically for important intellectual content: LZ, HYZ and YB; Approving the final version to be published: all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81772629, 81702431, 81602158 and 81602156), Individualized Medical Platform of National Clinical Research Center for Cancer (13ZCZCSY20300), Demonstrative research platform of clinical evaluation technology for new anticancer drugs (No. 2018ZX09206004). These funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the presence of identifiable patient information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuchong Yang, Xuanzhang Huang and Likun Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuchong Yang, Email: yangyuchong1987@126.com.

Xuanzhang Huang, Email: qq_347310502@126.com.

Likun Zhou, Email: zhoubaling123@163.com.

Ting Deng, Email: xymcdengting@126.com.

Tao Ning, Email: ningtao37@126.com.

Rui Liu, Email: liurui9003@163.com.

Le Zhang, Email: drzhangle@126.com.

Ming Bai, Email: bmmhead1982@126.com.

Haiyang Zhang, Email: wild_man@yeah.net.

Hongli Li, Email: hongli@126.com.

Yi Ba, Phone: +86-022-23340123, Email: bayi@tjmuch.com.

References

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y, Ueda J, Wei W, Inoue M, Tanaka H. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):233–242. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohashi S, Miyamoto S, Kikuchi O, Goto T, Amanuma Y, Muto M. Recent advances from basic and clinical studies of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1700–1715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao X, Zhang L, Feng GR, Yang J, Wang RY, Li J, Zheng XM, Han YJ. Preoperative Cyfra21-1 and SCC-ag serum titers predict survival in patients with stage II esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:197. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita T, Kikuchi T, Hashimoto S, Kobayashi Y, Tokue A. Cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) in bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 1997;32(2):237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holdenrieder S, Wehnl B, Hettwer K, Simon K, Uhlig S, Dayyani F. Carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin-19 fragments for assessment of therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(8):1037–1045. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer TM, El-Rayes BF, Li X, Hammad N, Philip PA, Shields AF, Zalupski MM, Bekaii-Saab T. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 is a prognostic and predictive biomarker in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who receive gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy: a pooled analysis of 6 prospective trials. Cancer. 2013;119(2):285–292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamazoe R, Maeta M, Matsui T, Shibata S, Shiota S, Kaibara N. CA72-4 compared with carcinoembryonic antigen as a tumour marker for gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A(8–9):1351–1354. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffy MJ. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a marker for colorectal cancer: is it clinically useful? Clin Chem. 2001;47(4):624–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charakorn C, Thadanipon K, Chaijindaratana S, Rattanasiri S, Numthavaj P, Thakkinstian A. The association between serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen and recurrence and survival of patients with cervical squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HQ, Wang RB, Yan HJ, Zhao W, Zhu KL, Jiang SM, Hu XG, Yu JM. Prognostic significance of CYFRA21-1, CEA and hemoglobin in patients with esophageal squamous cancer undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(1):199–203. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeguchi M, Kouno Y, Kihara K, Suzuki K, Endo K, Nakamura S, Sawada T, Shimizu T, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, et al. Evaluation of prognostic markers for patients with curatively resected thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5(6):767–772. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosugi S, Nishimaki T, Kanda T, Nakagawa S, Ohashi M, Hatakeyama K. Clinical significance of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels in esophageal cancer patients. World J Surg. 2004;28(7):680–685. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-6865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tokunaga R, Imamura Y, Nakamura K, Uchihara T, Ishimoto T, Nakagawa S, Iwatsuki M, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 is a useful prognostic marker in esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4(11):1659–1666. doi: 10.1002/cam4.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oki S, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Shimura T, Okigami M, Yasuda H, Fujikawa H, Okita Y, Yoshiyama S, Hiro J, et al. Clinical burden of preoperative albumin-globulin ratio in esophageal cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2017;214(5):891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, ten Kate FJ, van Dekken H, Obertop H, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan HJ, Wang RB, Zhu KL, Jiang SM, Zhao W, Xu XQ, Feng R. Cytokeratin 19 fragment antigen 21-1 as an independent predictor for definitive chemoradiotherapy sensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin Med J. 2012;125(8):1410–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada H, Nabeya Y, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Shiratori T, Gunji Y, Kobayashi S, Hayashi H, Ochiai T. Prediction of survival with squamous cell carcinoma antigen in patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2003;133(5):486–494. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi Y, Li B, Sun H, Zhang Z, Gong H, Li H, Huang W, Wang Z. Predictors of sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2010;31(4):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi Y, Li B, Wang Z, Sun H, Gong H, Zhang Z. CYFRA21-1 and CEA are useful markers for predicting the sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Biomarkers. 2009;14(7):480–485. doi: 10.3109/13547500903180265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura A, Watanabe M, Mine S, Kurogochi T, Yamashita K, Hayami M, Imamura Y, Ogura M, Ichimura T, Takahari D, et al. Failure of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(9):1–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival between the surgery plus chemotherapy group and the surgery group alone in ESCC patients based on CA72–4 and Cyfra21–1. (TIF 2027 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the presence of identifiable patient information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.