Abstract

Blood capillaries deliver oxygen and nutrients to surrounding micro-regions of tissue and carry away metabolic waste. In normal tissue, capillaries are close enough to keep all the cells viable. In solid tumours, the capillary system is chaotic and typical inter-capillary distances are larger than in normal tissue. Therefore, hypoxic regions develop. Drug molecules may not reach these areas at concentrations above the lethal level. The combined effect of low drug concentrations and local hypoxia, often exacerbated by acidity, leads to therapy failure. To better understand the interplay between hypoxia and poor drug penetration, oxygenation needs to be assessed in different areas of inter-capillary tissue. The multicellular tumour spheroid is a well-established three-dimensional (3D) in vitro model of the capillary microenvironment. It is used to mimic nascent tumours and micro-metastases as well. In this work, we demonstrate for the first time that dynamic intra-spheroidal oxygen maps can be obtained at the 3D multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH) using a non-invasive microelectrode array. The same oxygen distributions exist inside the equivalent but less accessible full spheroid. The MCH makes high throughput—high content analysis of spheroids feasible and thus can assist studies on basic cancer biology, drug development and personalized medicine.

Keywords: hypoxia in tumour tissue, oxygen distribution, electrochemical mapping, multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid, in vitro model of capillary microenvironment, in vitro model of micro-metastases

1. Background and introduction

Irregular development of the capillary network in solid tumours leads to the formation of micro-regions where inter-capillary distances are greater than in normal tissue. This creates areas where oxygenation is much below normal levels. This may be exacerbated by the lack of nutrients and inefficient removal of metabolic waste products, leading to local acidification. In such oxygen- and nutrient-deprived, acidic micro-regions necrosis develops. At the periphery of this necrotic core, a layer of dormant cells exist which are live but their metabolic processes are nearly shut down. Outside these areas, cells are close enough to the blood supply to be viable and capable of proliferating. Thus, provided that there is sufficient drug penetration, chemotherapy in these areas can be effective [1–3].

Hypoxia is caused by two processes: diffusion-limited transport across the tissue, and concurrent uptake and consumption by live cells via metabolic processes along diffusion paths. A similar diffusion–reaction–transport regime describes the movement of nutrients inward, while the clearance of waste products outward is diffusion limited. Outward propagation of acidity that may develop at and around necrotic areas is slowed by extracellular buffering. The concentration of therapeutic molecules during treatment also decreases with distance from the closest capillaries, owing to both diffusional limitation and cellular uptake and binding. Therefore, drug concentrations further from capillaries may not reach a lethal level.

Local hypoxia is known to adversely affect treatment efficacy even in areas where drug levels would be sufficient for effective cytotoxicity. Many conventional drug molecules are weak bases and their partitioning into cells is hindered by an acidic extracellular environment [4]. Thus, synergistic interactions between local oxygen deprivation, acidification and insufficient drug penetration contribute to the development of drug resistance in specific areas in tissue and can lead to therapy failure [2,5]. However, despite its importance, quantitative information on oxygenation, pH and drug penetration in the inter-capillary space is lacking. Therefore, how these parameters modulate the efficacy of therapy locally is poorly understood.

Pockets of low oxygen tension inside tumours play key roles in other contexts also, such as in resistance to radio-therapy, tumour proliferation and relapse, and metastatic behaviour [2,5–8]. Thus, assessing oxygen tension in different areas of tumour tissue is currently a subject of major interest. The spatial distribution of oxygen inside tumour tissue is, however, difficult to assess. To measure tissue oxygenation both direct and indirect methodologies have been developed. Direct methods are quantitative but invasive. Indirect methods are typically non-invasive but inaccurate.

Severe hypoxia in tumours and xenografts has been investigated by measuring steady-state oxygen profiles indirectly, with fluorescence ratio imaging, phosphorescence quenching microscopy, and other imaging techniques [9–12]. Non-invasive nuclear magnetic resonance and electron paramagnetic resonance-based imaging methods measure oxygen-dependent changes in relaxation times of magnetic molecules such as haemoglobin and phthalocyanines [13–18]. Immuno-fluorescence staining with EF5, a derivative of nitroimidazole that is localized to hypoxic tissue, and other hypoxia-related markers such as Green 2 W [19–22] is another indirect method that has also been used to quantify pO2 inside tumours. Imaging techniques, in general, facilitate the rendering of spatial maps; however, they are prone to signal attenuation due to surrounding non-hypoxic tissue and to quenching not allowing for long-term experiments. Also, translating indirect markers to quantitatively accurate oxygen concentrations is not straightforward. Quenched-phosphorescence-based sensing, however, allows low-invasive measurement of oxygenation via a photophysical process [12,23].

Oxygen concentration inside tumour tissue has also been measured directly by assessing pO2 using oxygen microelectrodes [9,24–27] and Eppendorf pO2 histography [28]. The limitation of this direct approach is that it is invasive, which restricts its wide use in clinical studies. However, owing to the direct access to pO2, this approach can be accurate and, therefore, it is considered the ‘gold standard' [27,28], especially for in vitro studies. Nonetheless, conventional oxygen microelectrodes have limited spatial and temporal resolution because a single needle-type microelectrode needs to be sequentially moved to different depths inside the tissue, which is possible only along the microelectrode's axis.

Multicellular tumour spheroids (MCSs) are spherical aggregates of cancer cells, typically of submillimetre diameter. Sutherland and co-workers [29] were the first to advocate the spheroid as an in vitro model of the tumour microenvironment between nearest capillaries. Similarities between the microenvironment in the spheroid and that in tumours, but without the complex network of blood vessels, make them a useful in vitro model for investigating the effects of physical parameters on biological and therapeutic outcomes [30,31]. The model is capable of mimicking in vitro the heterogeneous distribution of oxygen and other substances in tumour tissue. They also develop necrotic, dormant and proliferating areas [32–34] especially in larger spheroids (greater than 500 µm), which are therefore more useful as models of the microenvironment [18]. The combined effects of local hypoxia and acidification, and insufficient drug penetration can lead to resistance to therapy in tumour tissue, which the MCS is also capable of replicating [35–38].

Since its inception the spheroid has been extensively used for studying oxygen distribution [12,24,25,39–44], pH distribution [45], spatial modulations of biological parameters [46,47] and therapeutic efficacy [48,49] in vitro in three dimensions. More recently, other parameters (such as apoptosis, necrosis, cell proliferation and others) have also been investigated in the spheroid model combined with oxygenation [50,51].

Obtaining maps of oxygenation directly from the extracellular matrix inside spheroids has not been straightforward, especially for larger spheroids. Inserting a pO2 microelectrode in a spheroid is a lengthy and cumbersome procedure, and, owing to its invasiveness, the measured oxygen concentration may deviate from the actual oxygenation level at the same position in an intact spheroid. This is because the paths of oxygen diffusion may be partially obstructed by the electrode. Diffusion of oxygen from the surrounding medium to the area of interest along the electrode shaft may also be facilitated by gaps between the compact spheroid mass and the electrode. Finally, sequentially moving a microelectrode in a three-dimensional (3D) multicellular construct to different locations can only provide low spatial and temporal resolution in addition to further invasive damage. Thus, neither simultaneous oxygenation maps across the spheroid nor how they change in time can be obtained with invasive pO2 microelectrodes.

To address these problems, in this work, we introduce the multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH), which preserves the entire biology of the full spheroid but allows for high-throughput culture and high-content in-depth analysis of the spheroid's 3D cell mass. This work realizes electrochemical mapping of oxygenation across a 3D multicellular model tissue non-invasively for the first time using the MCH approach.

2. Material and methods

(a). Chemicals and reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA, USA), fetal bovine serum (FBS) and trypsin from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA) and penicillin–streptomycin from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). Analytical grade 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sodium azide (NaN3), 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) and agarose type VIIA used for cell experiments were bought from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Quartz distilled water (18 MΩ.cm) was used to prepare all solutions.

(b). Cell and tissue culture

MCF7-R doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cell line was acquired from the University of TX, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, TX, USA. MCF7-R cells were maintained and propagated in DMEM containing 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin in tissue culture dishes (Fisher Scientific). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment.

(c). Apparatus

(i). Gold micro-disc electrode array

A radial gold electrode array with five micro-disc electrodes for oxygen measurement at the hemi-spheroids was fabricated. Au wires, 5 cm in length and 50 µm in diameter, were insulated with 30 µm thick Parylene using a Parylene vapour depositor (figure 1a). The insulated wires were aligned under a stereo-microscope to run parallel to each other. The aligned wire arrangement was then set in non-conducting epoxy resin to obtain the electrode array of Au micro-disc electrodes, E1 to E5 (figure 1b). The other ends of the Au wires were connected to macro-wires via conducting epoxy (Circuitworks, CW 2400; Chemtronics, Urbana, IL, USA). The whole assembly was then embedded in a glass slide using non-conducting epoxy resin for stability. A reservoir for electrolyte around the electrode array was built by fixing the glass assembly inside a Petri dish using silicone elastomer. For isolation of the electrical circuitry from aqueous test solutions, the wires were routed through a leak-proof hole at the bottom of the Petri dish to the multichannel potentiostat. We note that one device with the electrode array can be reused many times.

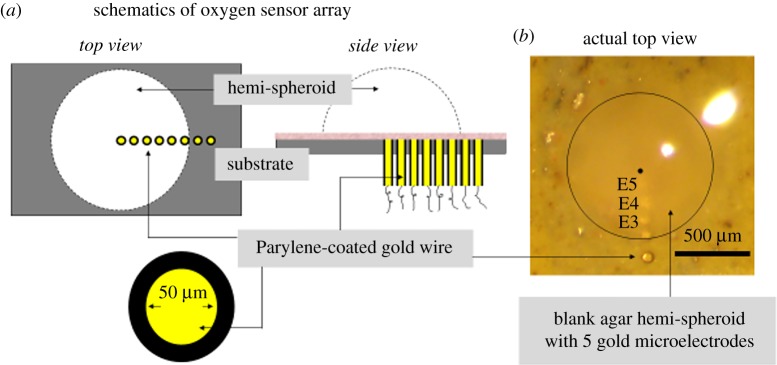

Figure 1.

Oxygen microsensor array for electrochemical mapping of oxygenation across the MCH. (a) Schematics of the oxygen sensor array. Gold micro-disc electrodes are created by embedding gold microwires into the substrate and positioning the wires such that their cut cross sections are flush with the upper surface of the substrate. A radial array is shown that extends from the centre to outside of the MCH. In this work, the wires were 50 µm thick but for higher spatial resolution thinner wires can be used. The sides of the wires were coated with Parylene for insulation and embedded in epoxy for mechanical support. A cellulose acetate layer 10 µm in thickness was deposited on top of the electrode array to reduce electrode fouling (pink layer seen in the side view). (b) Top view of the oxygen sensor array that was used in the experiments in this work, with an agar hemi-spheroid placed on top of the substrate. For better visibility of the electrodes the agar hemisphere is without cells. Distance (in micrometres) of electrode centres from the centre of the hemi-spheroid from E5 to E1: 180, 270, 370, 470, 610. E1 is outside the MCH, in this work, at a distance of about 115 µm from the MCH's edge. (The diameter of the MCH with cells used in the results shown in figure 2 was approx. 990 µm.) (Online version in colour.)

(ii). Instrumentation

A CHI 1030 eight-channel potentiostat (CH Instruments Inc., Austin, TX, USA) was used to perform all electrochemical experiments. The experimental set-up was placed inside a custom-built Faraday cage. A Scion camera was mounted on top of the Faraday cage for visual observation of the electrode array. The array of five Au micro-discs (working electrodes) was used for interrogating oxygen concentrations along the flat bottom of the hemi-spheroid. The obtained data are equivalent to oxygen concentrations in the equatorial plane of a corresponding full spheroid. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode with 4 M KCl filling solution (BAS Inc., West Lafayette, IN, USA) and a stainless steel wire were used as the macro-reference and counter-electrodes, respectively. The reference and counter-electrodes were common to all the micro-Au electrodes. PBS (pH 7.4) without glucose was used as the electrolyte medium unless otherwise indicated.

(d). Procedures and experimental protocols

(i). Preparation of test solutions for calibration

N2 gas was bubbled through air-equilibrated PBS for a minimum of 30 min to purge the oxygen from the buffer. After 30 min of bubbling, the oxygen concentration was considered to be nominally zero. The oxygen level in the test solutions was varied by adding oxygen-depleted buffer or air-equilibrated buffer, respectively, to decrease the O2 level from 21% to approximately 5% and back up to 21%. After each addition, the test solution was homogenized by mixing with a pipette (10 s). The oxygen concentration of the test solution was measured by a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Microelectrode Inc., Bedford, NH, USA). Addition of PBS and homogenization was done in 2 min between sets of consecutive measurements by differential linear scan voltammetry (DLSV) [52] (three DLSV scans per set).

(ii). Preparation of a cellulose acetate protective layer

One microlitre of 1% cellulose acetate hydrogel in a 1 : 1 mixture of acetone and cyclohexanone was deposited on top of the electrode array and allowed to dry for an hour, creating a 8–10 µm thin hydrogel layer on the electrodes [53,54]. This can be seen in the side view schematic (pink layer in figure 1a). The electrode assembly coated with the dry hydrogel layer was rinsed with deionized (DI) water and then hydrated in PBS for an hour before each experiment.

(iii). Preparation of multicellular hemi-spheroids

Confluent plates of MCF7-R cells were trypsinized and collected in a sterile 1 ml vial. The cell density and the total number of cells in the vial were estimated by cell counting using a haemocytometer. The cells were then spun down in a centrifuge and the supernatant medium was removed. The volume of the cell pellet was estimated. To the cells, 1% low-gelling-point agarose type VII-A (in PBS) was added and mixed well, to make 3D multicellular agar-based hemi-spheroids. The added volume was determined such that the final cell-volume fraction (CVF) was about 30%. The corresponding cell density was about 0.3 million cells µl−1 based on cell counting.

The vial with the cell–agar mixture was kept in a water bath at 37°C to prevent the agar from gelling. Tiny hemispherical droplets (600–1200 µm diameter, 0.1–0.9 mm3) of this mixture were deposited onto a cool Teflon® sheet using a 0.25–2.5 µl pipette (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, USA) to obtain hemi-spheroids. The Teflon® sheet with the hemi-spheroid was incubated in the culture medium used for MCF7-R cell culture at 37°C in a 5% CO2. We note that a compact MCH (close to 100% CVF) can be cultured in a few days from the initially 30% CVF MCHs.

(iv). Positioning of the hemi-spheroid on top of the Au microelectrode array

The Teflon® sheet on which hemi-spheroids are made was removed from the incubating medium. A hemi-spheroid was carefully transferred onto the electrode array using the curved edge of a pair of tweezers such that the radial electrode array was aligned along a spheroid radius (figure 1b). The positioning was done under a 2× stereo-microscope to ensure that the spheroid was resting on its flat (bottom) face. The microelectrode array needed to be radial relative to the centre of the MCH and the electrode closest to the centre had to be at the desired distance from it. (In this work, the centre of E5 is at radius 180 µm.)

After the agar spheroid was positioned at the desired location, a droplet of low-gelling agarose made in PBS maintained in liquid form at 37°C was dispensed onto the spheroid from the top to secure its position and prevent it from moving due to transient convection caused by the addition of metabolic modulator molecules during the experiment. PBS was added to the measurement device reservoir immediately after the spheroid position was secured. The time from when the hemi-spheroid Petri dish was removed from the incubator to positioning the MCH and oxygen measurement was started was about 3 min. During this time, the cells in the spheroid (except the outermost shell) were not directly exposed to air.

(v). Sequence of operations in an experiment

The Au micro-disc electrodes were polished using a fine emery paper, grit 2000 (Esslinger, St Paul, MN, USA) to expose fresh electrode surface before each experiment. The polished electrodes were rinsed with DI water and allowed to dry in air (1 h), after which a thin (10 µm) layer of cellulose acetate was deposited on top of the substrate and, thus, the embedded micro-disc electrodes. This layer was effectively a microscopic spacer between the MCH and the O2 sensors, which slowed the movement of large biomolecules from the extracellular space in the MCH to the surface of the micro-disc electrodes to minimize biofouling.

The electrodes were pre-conditioned electrochemically prior to starting the hemi-spheroid experiment by continuous cyclic voltammetry (CV) until a stable measurement (stationary CVs) was reached (typically 50 CVs were performed sequentially). The electrodes were then calibrated using DLSV [52] for the oxygen reduction current in PBS at different oxygen concentrations prior to the hemi-spheroid experiment (henceforth, referred to as pre-calibration). A hemi-spheroid was positioned on top of the microelectrode array and the oxygen concentrations under the hemi-spheroid (equivalent to inside the corresponding spheroid) were interrogated by DLSV (for details see below). It is noted that not all the electrodes need to be under the MCH; in this work, E1 was deliberately designed to be outside the model tissue. This is to measure the effect of overall metabolism in the entire MCH on the oxygen supply in the surrounding medium.

Oxygen reduction currents obtained in negative-going voltage scans were recorded at each electrode for about a half hour (40 min in the experiment shown in figure 2). After this, the viability of cells immobilized in the hemi-spheroid was tested by pharmacological modulation of the cellular oxygen consumption by delivering metabolic modulators NaN3 and DNP in the MCH. At the end of the experiment (about 100 min), the spheroid was removed and the current corresponding to the ambient oxygen concentration was recorded. The spheroid experiment was followed by a post-experiment calibration (henceforth, referred to as post-calibration) of the electrodes to check for bias and sensitivity drifts. The DLSV data recorded during these experiments were post-processed to extract oxygen concentration values using pre- or post-calibration.

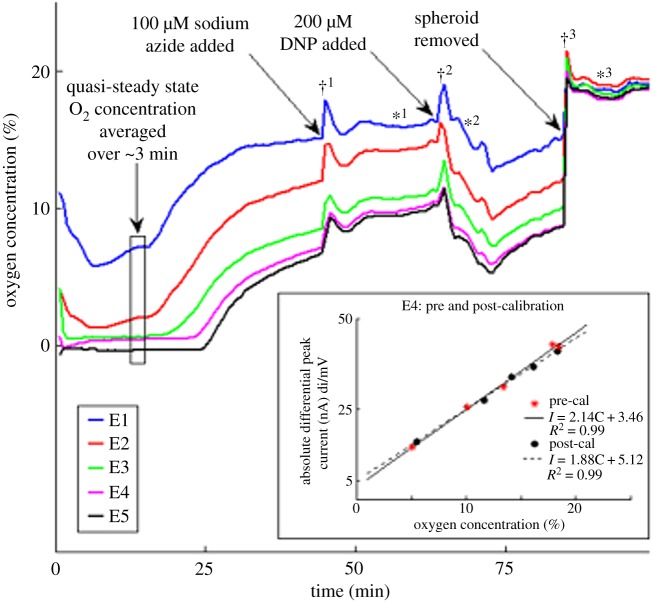

Figure 2.

Oxygen concentrations (%) measured continuously under a 3D MCH. Main panel. Time-series measurements at electrodes E1–E5 over 100 min. Initial cell density: 0.3 million cells µl−1, MCH diameter about 990 µm. The black box indicates a period of relatively steady oxygen levels at all depths. Increase in the measured oxygen concentrations () at the Au micro-disc electrodes is seen after the addition of sodium azide, NaN3 (100 µM final concentration) at . A rapid decrease in the oxygen concentrations () is measured after the subsequent addition of 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) (200 µM final concentration) at . The removal of the spheroid at returned the measured oxygen concentrations to the ambient oxygen level, approximately 21% (). Sharp oxygen concentration peaks seen immediately after the addition of NaN3 (), DNP () and removal of the spheroid () are attributed to brief convective flow created during each of these procedures which disrupts the depleted region around the MCH. Inset. Pre- and post-calibrations using differential linear scan voltammetry (DLSV, [52]). Calibration of differential peak current (nA mV−1) versus oxygen concentration (%) for electrode E4. (*) represents the differential current peak values obtained for pre-calibration and (•) represents the values for post-calibration. Linear regression fits for both pre-calibration (solid line) and post-calibration (dashed line) are shown. (Online version in colour.)

(vi). Addition of pharmacological drugs and glucose for modulation of oxygen consumption

The desired volumes of the NaN3, DNP and glucose solutions prepared in PBS were gently added to the test solution using a disposable transfer pipette. The solution was then homogenized by gentle circular movements induced by the same pipette for 10 s.

(vii). Removal of the hemi-spheroid

The spheroid was removed from the top of the electrode array by using flow. A thin disposable pipette tip was used to precisely direct a stream of buffer towards the spheroid with high enough flow velocity to detach it from the cellulose acetate-coated substrate.

(e). Voltammetry measurement protocol

For interrogation of oxygen levels at the Au microelectrodes, DLSV was used [52]. The DLSV parameters were adjusted such that electrochemical cleaning and surface stabilization were also achieved in each scan. Electrode calibration was done by consecutive DLSVs (0.4 V to −1.2 V at 100 mV s−1, 100 Hz sampling rate) performed every 2 min. Scans under the hemi-spheroid were recorded every 7 s (scans from 0.2 V to −0.5 V). A CHI1030 macro-program was written to automatically start and control the measurements and collect the data after the allotted quiet time for all the experiments.

(f). Data processing

All the LSV data recorded during the experiments were post-processed using Matlab 7.9.0. Numerical differentiation using a first derivative Savitzky--Golay quadratic smoothing filter with a 25-point differentiation window (equivalent to 25 mV) was used to obtain DLSV curves [52]. The height, i.e. the local minimum (due to the cathodic scan) of the differential oxygen reduction peak currents, was used to compute a time series of oxygen concentrations using the calibration data.

Pre-calibration was used to obtain oxygen concentrations under the MCH for the initial part of the experiment in PBS and for after NaN3 addition. NaN3 does not alter the differential current peak height for oxygen (control experiment, not shown). Post-calibration was used to obtain oxygen concentrations from the differential cathodic peaks from the time of DNP addition. The phenol group of DNP is electrochemically active and can be reduced, albeit at potentials more negative than the oxygen reduction potential. The activity of DNP still slightly alters the position of the oxygen reduction peak on the voltage axis and also the height of the peak (control experiment, not shown).

(g). Statistical analysis

Standard deviation of the peak currents for each pre-calibration dataset was calculated considering the linear regression of calibration as the true value. A 95% confidence interval around the linear calibration was estimated using Students t-test. Finally, we tested whether the post-calibration data were within the estimated confidence interval to be able to tell with 95% certainty if the two calibrations were similar (statistically indistinguishable) or not.

3. Approach

Treatment resistance of tumours leads to therapy failure. Cellular (not tissue level) mechanisms that are detrimental to therapy are different modalities of drug resistance which together are termed multidrug resistance (MDR) [55]. MDR can be replicated in vitro using two-dimensional cell monolayers [56] and, ideally, single cells [57]. However, tumours may be resistant to a given treatment even if the cancer cells per se are not resistant to the drug used. Therefore, this type of resistance is better termed therapy resistance, which only 3D cell constructs can replicate. This type of resistance is termed multicellular resistance (MCR) [6,37,38,58].

The spheroid is a model of tumour tissue between blood capillaries but it can also mimic nascent tumours and micro-metastases. Despite the MCS being the earliest 3D tumour model, it is still the most commonly used one owing to its simple geometry and reasonable reproducibility. Several practical problems limit, however, better utilization of the MCS model: problems related to culture, and to in-depth and high-content analysis.

(a). Culture

The two main approaches are the scaffold-free, or liquid-based, and the scaffold-based approach. The first begins with individual cancer cells that grow into a compact, nearly spherical construct of hundreds to thousands of cells. Diverse methodologies are used to ensure that the cells remain attached to each other rather than to the dish, and stay in one 3D tissue-like mass. Scaffold-free methods include rotating vessel [59], pellet culture [60], hanging drop [61], magnetic levitation [62] and other techniques. Scaffold-based cultures are made by seeding cells within a 3D scaffold, natural or man-made, where the initial cells multiply, ultimately developing into a spheroid-like construct but fully embedded in the scaffold from which it needs then to be released (when possible) after it reaches the desired size [63,64]. Both approaches require multiple operations and often considerable culture time, especially for larger MCSs that more realistically mimic the in vivo microenvironment [18]. The second method rarely leads to mechanically robust and truly compact spheroids. Culturing heterogeneous constructs incorporating multiple cell types that coexist and interact in tumour tissue in addition to cancer cells in vivo is still often challenging. To grow MCSs from primary cells (such as those obtained from biopsies) is feasible for limited cell types, and often only small spheroids can be made [65].

(b). Analysis

Depth-resolved analysis in larger constructs has been a challenge for decades. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy [66] is capable of deeper tissue penetration, though it is limited by the availability of optical markers that distribute evenly in a large cell mass reasonably fast. More recently, new techniques have been developed that enable better intra-spheroidal penetration but they are limited to parameters that can be optically indicated [12,42,43,50,51]. Variables that can be best measured by non-optical means require direct contact, such as ultra-microelectrodes for molecular oxygen or pH, which can only be assessed invasively. Such measurements require special expertise and thus they are not feasible in high-throughput settings. Cell viability in larger intact MCSs is difficult to assess, especially in a depth-resolved fashion. The mapping of drug penetration would require in-depth access whether optical or with direct-contact sensing, which is not straightforward. For these reasons, in practice, the most commonly used measure of drug efficacy is changes in spheroid diameter upon exposure to therapeutics, and global cell viability.

Here, we introduce the multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH), a derivative of the conventional spheroid that lends itself to high-throughput and high-content analysis. Real-time monitoring of multiple variables across the model tissue as changes are happening is feasible.

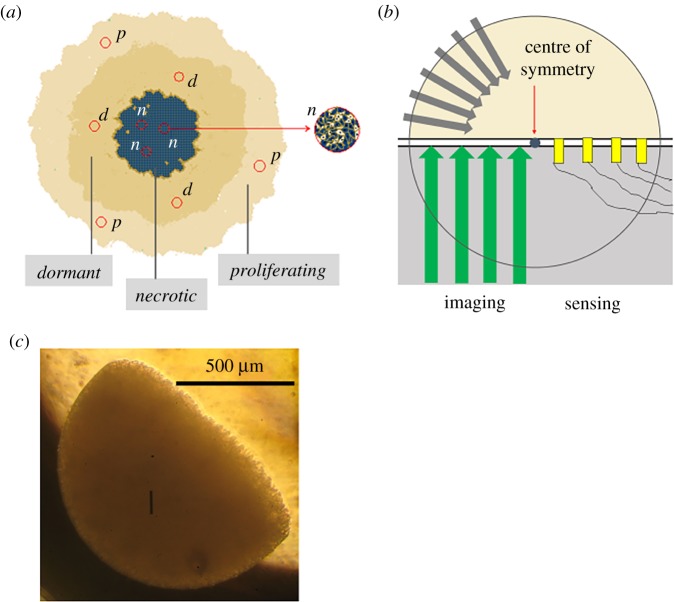

An imperfect real spheroid (figure 3a) when idealized (figure 3b) is spherically symmetric in terms of all transport paths and, consequently, biological parameters. Thus, any half of the MCS functions in the same way as the other half, without having any influence on each other. Thus, if we ‘remove' the lower half of the MCS (grey half circle in figure 3b) what remains is the equivalent MCH (yellow in figure 3b) but with a ‘window' exposed, available for both non-contact imaging and direct sensing modalities that require contact with the interstitial fluid. Combinations are also possible, such as an optical indicator membrane underneath the MCH whose colour distribution is then imaged in a non-contact fashion [67,68]. The remaining problem to solve is how to make hemi-spheroids such that high-throughput culture and analysis become feasible. We have achieved this by suspending the cancer cells in dilute temperature-sensitive hydrogel, which, when drop cast onto a substrate of suitable temperature, instantaneously gels. By controlling the volume and the temperature of the suspension and that of the substrate together with the distance between the dispenser and substrate (see Material and methods), nearly ideal MCHs can be made (figure 3c). These constructs are more reproducible in terms of size, shape and cell density than conventionally cultured spheroids. Heterogeneous model tissue can be created by drop-casting a suspension of the desired mix of the required cell types. MCHs can also be made from primary cells in the same way. To achieve compactness a few days of culture is sufficient.

Figure 3.

Multicellular 3D tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH): experimental approach. (a) Schematic of the interior of a conventional 3D multicellular tumour spheroid (MCS). The MCS consists of hundreds to tens of thousands of cells. Diameters range from about 100 µm to 1.2 mm. The cells close to the surface have enough nutrients, oxygen, and clearance of metabolic waste to be metabolically active and proliferate. Around the centre a necrotic core develops owing to lack of oxygen and nutrients and accumulation of waste products, leading to local acidification. Between the proliferating and necrotic regions, a shell of dormant cells exists. These cells are metabolically inactive but remain viable. Owing to spherical symmetry different micro-regions (red circles) in the same concentric shell are in similar environments (p, proliferating; d, dormant; n, necrotic). (b) Schematic of an idealized multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH). The lower hemisphere is removed (grey area) and the upper hemisphere is placed face down on top of an impermeable substrate. Inward flux of oxygen and nutrients (grey arrows) is preserved since there is no transport path that would cross an equatorial plane. The removal of the lower hemisphere does not perturb the outward transport of waste products for the same reason. Thus, a window into the interior of the spheroid is created but without interfering with transport paths and, therefore, the cells in the remaining half do not ‘sense' that the other half of the spheroid is missing. Using a transparent substrate, different microscopy modalities can be used (green arrows) to acquire functional maps across the entire hemi-spheroid about morphology and distribution of fluorescence markers, and concentration maps of molecules that can be imaged with a thin optically active indicator optode membrane between the MCH and the substrate. Dynamic imaging of drug penetration and cell viability is also possible. For molecules that cannot be imaged optically, arrays of microscopic direct-contact sensors can be embedded in the substrate (yellow blocks). Hence, the MCH can provide a wealth of information that it has not been possible to acquire with conventional full spheroids. Yet, the maps obtained using the MCH are equivalent to the respective depth-resolved distributions in the intact MCS. (c) Image of an MCH of MCF7-R doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells. The cells were cultured for 4 days to form a compact hemi-spheroid. (Initial agar concentration: 1% w/w in PBS; addition of the cells further diluted the gel.) (Online version in colour.)

4. Results and discussion

(a). Agarose scaffold-based multicellular hemi-spheroid

The MCH is analogous to a liquid-cultured spheroid despite a hydrogel scaffold, agarose, being involved. Agarose is used here merely as a mechanical support that traps cells uniformly in an already hemi-spherical volume. Agarose is biocompatible but it is biologically inert. Therefore, it has no influence on the extracellular matrix (ECM) that develops. This situation is similar to a liquid-cultured spheroid where the ECM is produced solely by the cells.

The MCF7-R breast cancer hemi-spheroids used in this work were made with a 30% initial cell-volume fraction (Material and methods). This implies that about two cell divisions per originally embedded cell are sufficient to make the MCH compact. This is typically achieved after 3–4 days of culture, as opposed to the much longer culture times required to produce large MCSs as in this work (650–1200 µm) with either of the conventional methods: liquid-based or scaffold-based culture. We note that morphological parameters such as diameter, shape and irregularities significantly affect the response of large spheroids to treatment [69]. While traditionally cultured MCSs exhibit significant variations identical MCHs can be made when the same parameters are used as nearly ideal hemi-spheres (figure 3c).

The presence of agarose in the compact MCH is inconsequential since, besides being inert, it is present at about 0.6–0.7% w/w. (The MCH is made with 1% agarose of about twice the volume of the pellet of the spun-down cells, which do not contain agarose; see Material and methods.) Additionally, since agar is heavier than water, the total volume occupied by the agarose strands relative to the entire construct is even less. The MCHs made of MCF7-R breast cancer cells used in this work appear compact in bright field microscopy after 4 days of culture (not shown). We note that some MCHs made of more aggressive cell lines (not discussed in this work) after longer culture develop small secondary spheroids budding from the main MCH. These secondary spheroids are devoid of agarose yet they are visually indistinguishable from the parent MCH that was made with agarose (not shown).

It is noted that agarose has been used successfully as a scaffold to support the growth of a range of different tissues for both research and clinical use [70]. Among others, stem cells cultured inside agarose scaffolds can form functional chondrocytes [71], cardiomyocytes [72] and neurons [73]. Thus, agar can be used as a biologically inert mechanical support for tissue formation.

(b). Measuring oxygen distribution with a radial array of gold micro-disc electrodes under multicellular tumour hemi-spheroids of MCF7-R breast cancer cells

Gold micro-disc electrodes are used here for measuring oxygen (figure 1) via electro-reduction of O2. A conventional oxygen electrode, in reality, is a complete voltammetric cell separated from the sample by a gas-permeable membrane to exclude interference by other molecules that may be present and cathodically active. Molecules typically present in media used for in vitro cellular experiments; however, they cannot be reduced at noble metal electrodes. This is particularly valid for experiments performed in PBS, which was the medium used in this work. Also, neither glucose nor the pharmacological modulator NaN3 is voltammetrically active. DNP can be reduced but below the potential of oxygen reduction and we found very little effect of DNP on the oxygen wave at the concentration DNP was used (not shown).

In the vicinity of an MCH, there may be some larger biomolecules, such as by-products of cell metabolism and/or components of the ECM. However, no significant presence of biomolecules that could be electrochemically reduced has been reported. Therefore, in this work, gold micro-discs were used as oxygen sensors without a gas-permeable membrane, with a remote macro-reference electrode. A thin layer of cellulose acetate between the electrodes and the model tissue acts as a spacer, and prevents direct physical contact with the cells (see Material and methods, and figure 1a side view).

The MCH model is biologically equivalent to the analogous full spheroid owing to symmetry in mass transport (inward and outward) including oxygen, with one potential caveat: the first cell layer at the bottom plane faces the substrate. However, these cells are still in communication with other cells in every direction. This is because the 10 µm low-density cellulose acetate spacer between the substrate and the first layer of cells (see Material and methods) does not obstruct the movement of signalling and other molecules: it may add a maximum of half of one cell's diameter to the diffusion paths between adjacent cells but the corresponding delay would be only of the order of milliseconds, and even this is only for the part of the molecular traffic that originates from the bottom of the cells.

Oxygen is reduced at a gold electrode in two consecutive steps: at −230 mV a peak and at −700 mV a shoulder is seen in negative-going DLSV [52]. DLSV has been developed in the authors' laboratory because it was the technique considered best for selective and quantitative measurements; differential square wave voltammetry (DSWV) did not perform well for measuring oxygen in the experiments in MCHs. The baseline was complicated and can be three to five times larger (depending on pO2) than the actual reduction peaks (at −250 mV and −750 mV, respectively), which made objective determination of the peak heights not possible. The baseline in DLSV was, in the same solution, flat and practically zero. In the same time, the sensitivity of DLSV was close to double that of DSWV. The reason for the much better performance of DLSV is that, despite being a differential, it is essentially Faradaic because the differentiation is performed in a virtual space (digital processing), as opposed to square wave voltammetry where differentiation is performed physically, which skews the results owing to voltage-dependent electrode capacitance.

Oxygen reduction at the gold electrode at physiological pH has not been studied in detail. Our earlier work using DLSV shows a peak at −230 mV that corresponds to the first step of O2 reduction to H2O2, which is followed by a flat section and then a shoulder which represents the second step of oxygen reaction immediately following the first [52]. Therefore, very little, if any, H2O2 would ‘escape' from the electrode to the cells above according to voltammetry theory [74]. Therefore, damage to cells due to the measurement itself is unlikely.

A diffusional overlap between adjacent electrodes is negligible despite their closeness to each other. From the duration of the O2 reduction peak (about 1 s, from [75]), the diffusion coefficient of molecular oxygen in buffer (2.1 × 10−5 cm2 s−1) and the fact that there is a considerable edge effect at the 50 µm disc electrodes, it is estimated that the extension of the oxygen depletion is less than half of the distance between two electrodes (not shown).

In this work, we studied hemi-spheroids made of the MCF7-R breast cancer cell line. A linear regression fit was obtained for each electrode pre- and post-experiment. A representative set of pre- and post-calibration data is shown in figure 2, inset, for electrode E4. Regression coefficients on the average 0.995 with residual errors of 0.4% O2 have been obtained for all five electrodes with DLSV using the cathodic peak at −250 mV. The current values estimated from the post-calibration for the O2 concentration range of 0–21% were within the 95% confidence interval of the pre-calibration values for all the electrodes. This is a further advantage of DLSV: a decrease in sensitivity of the order of only 5% during the entire experiment was found with DLSV, while post-calibration obtained via DSWV had about 40% lower sensitivity than the pre-calibration. This means that biofouling seen by DLSV was about 5% while it was 40% by DSWV. What makes interpretation of this observation elusive at this time is that the electrodes were calibrated with both techniques before and after the same experiment. This means that in fact significant biofouling of the electrodes, at least 40%, has taken place during about 100 min of exposure to the biological environment, but DLSV is essentially insensitive to this electrode fouling as opposed to DSWV, the technique commonly thought of as the best among differential voltammetry techniques.

We note that, in this work, pO2 is measured in the ECM directly instead of indirectly by hypoxia markers. This is what made it possible to also obtain information outside the MCH using the same type of microelectrode as those under the MCH.

(c). Oxygenation in and around an MCF7-R breast cancer hemi-spheroid

(i). Oxygen distribution limited by mass transport and metabolism of oxygen: oxygen-limited oxygen distribution

A hemi-spheroid was positioned on top of the radial array of calibrated Au electrodes (as in figure 1b but more opaque owing to the presence of cells) and oxygen concentrations were measured at each electrode simultaneously. A representative experiment is shown in figure 2. Here, the MCH (diameter 990 µm) was positioned such that the centre of E5 was about 180 µm from the centre and E1 was outside the MCH at a distance of 115 µm from the MCH's edge.

The first voltammetry measurement was performed about 2 min after positioning the MCH and stabilizing it with a small drop of liquid agarose gel (Material and methods). This time point is indicated as 0 min in figure 2. By this time, the MCH was already anoxic at E5, within about 200 µm of the centre, or 300 µm below the surface. However, by this time, the medium outside the MCH was also depleted: at about 115 µm from its edge pO2 = 11%. A rapid decay at E4 and E3 led to significant (pO2 < 1.3%) to severe (pO2 < 0.3%) hypoxia [43,76] also at E4 and E3 within 2 min. Thus, the MCH was close to anoxic up to 400 µm from the centre, or at a depth of 100 µm from the edge by 2 min. Up to 8 min a sustained decay was seen at E2 and E1, too. Relatively steady levels were seen after this up to 15 min. The most stable readings were from 11 to 14 min, indicated with a box in figure 2. (It is noted that the trace appears to be slightly negative at E5 up to 25 min. The nominal value is within 0.5% oxygen below zero, which is about the uncertainty, random and drift together of the oxygen measurement. A few negative data points were also seen early in the trace at E4, of similar origin.)

The sustained decay at E2–E1 is attributed to the consumption of oxygen that had temporarily increased relative to steady-state levels prior to the beginning of the measurements at the bottom plane of the MCH during transfer and placement. It takes a very short time for the innermost area of the MCH to become completely hypoxic. A period of 8 min of continuous consumption of O2 is required for the oxygen levels to reach an approximate steady state in regions closer to the surface (E2). This is because the O2 supply is closer to these regions and therefore inward transport can better ‘keep up' with consumption. Overall, at steady state the rate of oxygen consumption in each hypothetical shell becomes equal to the rate of supply by diffusion entering from the surrounding shell minus that leaving towards the next shell inwards.

pO2 values seen at different depths are limited by mass transport and metabolic consumption of oxygen by the cells. Partial oxygen depletion detected outside the MCH means that there is significant diffusional limitation of oxygen transport in the medium, too. However, the transport in the entire system—hemi-spheroid plus surrounding medium—is not completely limited by diffusion in the medium because if that were the case O2 concentration at the surface of the MCH would be zero. This situation would be analogous to a hemi-spherical electrode with fast electrode kinetics. The difference in the overall transport problem in the MCH model relative to a hemispherical electrode of the same diameter is that consumption is not limited to the surface like in electrochemistry but rather it is a 3D process: all the live cells inside the MCH are microscopic sinks of O2. Diffusion of oxygen towards the spheroid in the surrounding medium is analogous to mass transport to an electrode under mixed kinetic–diffusion control.

(ii). Oxygen distribution modulated by glucose depletion: glucose-limited oxygen distribution

After a period of relatively stable oxygen distribution (from 8 to 14 min) pO2 at E1 begins to increase and after a sustained increase up to about 35 min the level of oxygen stabilizes at 15%. The onset of increase happens at gradually later time points from E2 to E5. Even the innermost anoxic area (E5) experiences an oxygen build-up after 25 min, reaching 5% by 40 min.

The sustained increase in oxygen concentration is attributed to glucose depletion inside the spheroid. MCHs are incubated in cell culture medium containing 25 mM glucose prior to the experiment. As glucose is being consumed in every shell inside the MCH glucose availability decreases with depth even during incubation. Nevertheless, during an oxygen-limited regime, the decrease in glucose with depth cannot be steep since little of it gets consumed where there is severe hypoxia. Therefore, there is excess glucose relative to what is required by the cells deep in the MCH.

The experiment in figure 2 is performed in PBS without glucose. Thus, glucose in the extracellular space and inside the cells is used up in a finite amount of time. In addition, some fraction diffuses back into the PBS. Also, where there is more oxygen available glucose will be used up faster. These together result in glucose deprivation which hits the outermost cell layer first. This is why O2 at E1 and E2 begins to increase before the deeper electrodes would sense the effect of slowing metabolism.

Low glucose is associated with the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) metabolic regulatory pathway [77]. Insufficient glucose leads to slowing of ATP production, resulting in accumulation of AMP, which leads to AMPK activation. AMPK turns on different transcriptional pathways for cells to correct for the low ATP situation. This slows down the activity of cells by inhibiting cell cycle progression [77,78] and starts the deployment of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes. For our experiment, the increase in oxygen concentration inside the spheroid is caused by the gradual cessation of cell activity. The switching in glucose metabolism requires the cells to make the required enzyme and transporter molecules, which takes longer than 30 min, which is more than the time of the observed increases in oxygen concentration.

In a control experiment, 25 mM (final concentration) glucose was added to the PBS after the second plateau was reached (in figure 2 at around 40 min). This resulted in an almost instantaneous decrease in measured oxygen concentrations for all the electrodes, which confirmed the above interpretation. Thus, it was possible to switch from O2 limitation to glucose limitation and then back to O2 limitation.

(iii). Oxygen distribution affected by metabolic modulators

To further investigate the viability of the MCF7-R cells in the MCH, the response in oxygen consumption to metabolic modulator molecules was tested in the same experiment. Oxygen concentrations measured by all the Au electrodes increased after the addition of 100 µM (final concentration) sodium azide, NaN3, at (figure 2), a reversible metabolic poison [79] (figure 2, ). This indicates that there is some residual metabolism right before adding the modulator molecule. pO2 decreased rapidly after the addition of 200 µM (final concentration) DNP at , which reverses the effect of the azide [80] (figure 2, ). (It is noted that brief transient peaks seen after additions are caused by the temporary flow generated by mechanical mixing, which brings buffer with higher O2 content to the MCH.)

These changes in oxygen consumption by metabolic modulators further confirm the viability of the MCF7-R cells embedded in the hemi-spheroid. Addition of NaN3 causes the already decreased oxygen consumption by the cells to slow further down by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase in the electron transport chain (ETC). This results in an additional (incremental) increase in oxygen at each electrode, with very little delay deeper in the MCH (figure 2, ). Subsequent addition of DNP results in a rapid increase in oxygen consumption owing to the uncoupling of ETC and ATPase by negating the proton gradient. The increase in oxygen consumption by the MCF7-R cells translates into decreased oxygen in the vicinity of the cells, which is measured by the electrodes (figure 2, ). Owing to the already depleted glucose reservoirs, however, O2 does not decrease to the levels seen before 15 min.

(iv). Oxygen distribution measured after removal of the multicellular 3D tumour hemi-spheroid from the microelectrode array

The changes seen in oxygen concentration with both modulator drugs also confirm that the electrodes remain functional during the experiment. At the end of the experiment (100 min), the hemi-spheroid is removed (indicated by in figure 2) and the DLSV peak currents almost fully recover to indicate close to ambient oxygen levels at each electrode. This also shows that electrode fouling during the entire experiment was negligible (when using DLSV as opposed to DSWV).

(d). Oxygen maps around and inside the multicellular 3D tumour hemi-spheroid

From the data shown in figure 2, it is possible to reconstruct oxygen maps under the MCH, which corresponds to oxygenation maps in depth in the equivalent MCS. Such simultaneous distributions of molecular oxygen across tissue have been obtained with direct sensing for the first time in this work. This is made possible by the ‘window' into the MCS created by exposing the flat face of the equivalent MCH to direct cross-sectional microsensing. Each map shows a simultaneous snapshot of an entire distribution of molecular oxygen in the MCS.

From the recordings made close to, but outside, the MCH with E1, it is clear that oxygen depletion extends into the medium surrounding the MCH. To be able to create a map of the entire oxygen field affected by metabolism inside the hemi-spheroid, diffusion of O2 from ambient levels far from the spheroid up to the edge of the MCH also needs to be considered.

Since oxygen changes slowly in the tissue (on the minute scale) it is reasonable to approximate diffusional transport in the surrounding medium as steady-state diffusion: a steady-state mass transport problem. (It is noted that the diffusion profile in the unobstructed medium adapts much faster to the oxygen uptake by the spheroid that varies slowly. Nevertheless, diffusion in the medium towards the MCH could be called more precisely a quasi-steady state at all times.) Diffusion towards a spherical sink leads to a polar concentration distribution for r > R as follows:

| 4.1 |

where R is the radius of the MCH, r is the distance from the centre outside the MCH, and is the O2 concentration far from the MCH (21% ambient level) [81]. Since c is measured by E1 outside the MCH the equation can be modified to the equivalent

| 4.2 |

where RE1 is the radius at E1.

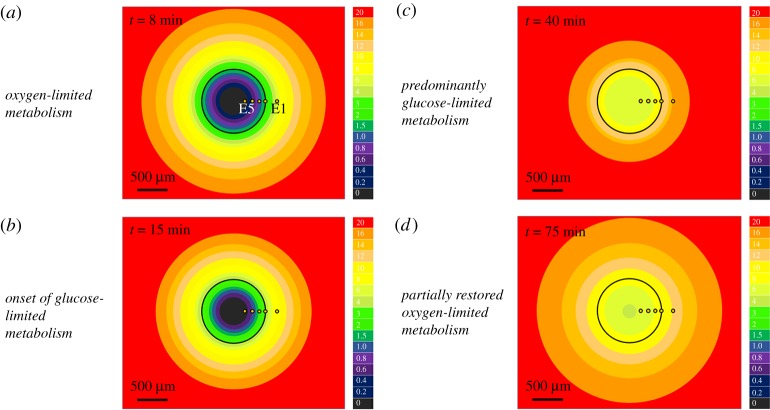

Using the recordings made inside the MCH with E5–E2 and equation (4.2) to estimate pO2 outside we created oxygen maps corresponding to several time points in the experiment shown in figure 2. The colour-coded maps shown in figure 4 strikingly illustrate the following. (i) It is possible to reconstruct, by taking advantage of spherical symmetry and a linear microelectrode array, dynamic distributions of oxygenation inside and outside the hemi-spheroid and as they respond to varying metabolic situations. (ii) Profound changes in oxygenation can occur in the entire spheroid depending on the availability of oxygen and/or nutrients (glucose being the example here) and the presence of metabolic modulators. (iii) Oxygen distribution and supply from the medium are intricately interwoven with changes in intra-spheroidal metabolism.

Figure 4.

Dynamic maps of oxygen inside and around the MCH. Solid black line: boundary of the 990 µm MCH analysed in figure 2. Column to the right of the maps: colour calibration; values: oxygen levels in % (air-saturated buffer: 21%). Space inside the MCH is a non-uniform and time-variable sink of oxygen owing to metabolic consumption of oxygen by cells. Outside the spheroid shells of depleted oxygen are seen despite there being no oxygen consumption. This shows that live tissue significantly depletes oxygen around it, thereby generating diffusion towards it. (a) Oxygenation maps seen at about 8 min after positioning the MCH above the microelectrode array. This map corresponds to the greatest rate of oxygen consumption everywhere in the MCH. It is remarkable that, in a medium at nominally 21% O2, at a distance of 115 µm outside the tissue the oxygen level can already be as low as 5.9%. (b) Gradual depletion of glucose inside the MCH slows the rate of metabolism. Therefore, oxygen depletion decreases and, thus, oxygen levels begin to bounce back up at about 15 min. (c) Depletion of glucose reduces oxygen consumption and, thus, diffusion towards the MCH. The effect is visible most clearly at E1, outside the MCH. Closer to the centre of the MCH oxygen is still relatively low at 40 min (see figure 2, E3, E4, E5). (d) Partially restored oxygen metabolism is seen after the addition of DNP, at about 75 min. During the previous period when the metabolic poison sodium azide decreased the metabolic rate inside the spheroid and especially in the outer layers to very low levels (figure 2), there was enough time for glucose to partially diffuse outward from the anoxic area where it had not been consumed. This made it possible for a rapid decrease of oxygen to happen for a few minutes in the MCH after addition of DNP. (Online version in colour.)

It is noted that an analogous approach was used earlier in our work to determine oxygen consumption by a single cell [75]. Here, the cell is surrounded by a microfabricated ring ultra-microelectrode. pO2 measurements made at this ring were used to compute the rate of oxygen metabolism by the cell using the same hemi-spherical and quasi-steady-state approach as in this work, the difference being only in the size of the construct: single cell versus multicellular spheroid.

It is noteworthy that the studied MCH creates by its own metabolism biological oxygen levels around it despite the bulk medium being saturated with air at 21%. Capillary pO2 in normal tissue is within 3–7%, and 5% is considered typical [82]. A minimum of 5.9% indicated by E1 is seen at 9 min in figure 2, corresponding to the highest metabolic rates when no glucose limitation is evident. Diffusional limitation in the buffer outside the spheroid has not been considered before even though the same diffusion coefficient is used in mathematical models to derive transport of oxygen inside spheroids, as in water. This implies that there must be a gradient in the buffer, too, and thus pO2 cannot abruptly drop when moving into the cell mass from a flat profile outside. Thus, setting the boundary condition at the edge of the MCS as equal to pO2 in the bulk of the medium (in most cases 21%) can lead to skewed intra-spheroidal oxygen levels and distributions. Therefore, without experimentally assessing oxygen at the surface of the MCS it is difficult to build a quantitative mathematical model of MCS oxygenation. Moreover, as seen in figure 4, dramatic changes can happen to oxygen levels inside and at the MCH and, therefore, at spheroids in just minutes. Thus, pO2 at the boundary is not stable, and if changes in spheroidal processes are to be simulated then the overall problem involves an optimization where intra-spheroidal processes and extra-spheroidal transport need to be modelled together. This may be a difficult problem to solve without at least one oxygen measurement performed outside the spheroid because processes inside the spheroid depend on oxygen availability at the surface of the spheroid, which depends on processes occurring inside the spheroid.

As shown in our earlier work [75] at a single cell pO2 is about 19% in air-saturated medium. Oxygen levels around 15% were found at a cluster of five cells. The large spheroid in this work created about a 6% oxygen level in its immediate vicinity. In [83], we saw nearly zero pO2 directly above cell monolayers in a dish. This is because single cells, very small clusters, and spheroids all create spherical diffusion patterns around them that lead to steady-state transport. A monolayer is, however, analogous to a macro-electrode where one-dimensional diffusion does not lead to a steady supply of oxygen: a transient similar to what Cottrell's equation predicts evolves, leading to essentially zero oxygen at the cells in a short time. This has been confirmed with experiments (not shown here). This set of data taken together shows the power of analogy in science: transport at an electrode and extracellular transport are very similar mathematically. The other conclusion is that most cellular experiments are not done at 21% pO2 even when the medium is air saturated. This fact is largely ignored in in vitro experimentation using monolayers, but can have far-reaching consequences relative to correct interpretation of the data obtained.

5. Conclusion

The multicellular tumour hemi-spheroid (MCH) is a novel in vitro 3D tumour tissue model which is equivalent to the analogous conventional spheroid but more amenable to high-throughput culture and high-content analysis. Besides mapping oxygenation, as shown in this work, it is suitable for analysis of pH distribution, drug penetration and to map other variables including cell viability across tissue. Real-time dynamic mapping is possible with non-contact imaging techniques as well as with microsensor arrays that require direct liquid contact. Information obtained involving direct contact is representative of the interstitial fluid in the ECM. Information from the surrounding medium can also be acquired with sensors extending beyond the surface of the 3D cell mass. Imaging optically responsive membranes underneath the MCH combines non-contact and contact modes of measurement.

Using biologically inert agarose just for mechanical support for a hemispherical cell suspension, the resulting MCH after reaching compactness is analogous to scaffold-free cultured spheroids. However, other temperature-sensitive hydrogels can also be adopted such as a mixture of agarose–collagen, or matrigel. In this way it may be possible to establish MCHs that combine the advantages of free liquid culture and culture within scaffolds that can modulate therapeutic response. The MCH holds promise to aid more effective drug development, as well as personalized medicine owing to the fact that primary cells can be incorporated with ease.

We note that solid tumours can be treated with surgery, radiation therapy and other treatment modalities with good efficacy. Ninety per cent of therapy failures are actually associated with metastases, the treatment of which is at this time inefficient. The spheroid is an ‘inverse' model of the capillary microenvironment in solid tumours, but it is a correctly aligned model of avascular nascent tumours and micro-metastases. Therefore, we believe that the MCH introduced in this work has potential in aiding studies aimed at devising more efficient therapies to eradicate initial metastases.

An interesting finding of this work is the rapid changes observed in oxygenation profiles across the entire cell mass upon external effects or internal glucose status. Dramatically different oxygen maps can follow each other on a time scale of a few minutes in a functional hemi-spheroid. The propagation of changes inward all the way to the core is similarly fast, and this in actually large constructs. The rapid changes seen contrast the very long time scale of usual experiments on drug efficacy where both spheroid diameter and cell viability change very slowly, on a time scale of many days. Monitoring oxygenation may predict drug efficacy much sooner and in a functional manner compared with morphological parameters and cell death.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prasad Oruganti for his contribution to agar-suspended hemi-spheroid fabrication (work being published elsewhere) and Kihwan Kim for his observation on budding of secondary spheroids from hemi-spheroids (work being published elsewhere). Ulrich Hopfer is acknowledged for many useful discussions and advice on metabolic modulators.

Data accessibility

The primary data and codes are available in the PhD thesis [84]. The voltammetry technique used in this work, DLSV, was published in 2013 [52]. An example of processing of raw data for one particular electrode and one particular time point in figure 3 is shown in detail in the electronic supplementary material.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Science Foundation under grant award no. 0352443. Full financial support (stipend and tuition) for 1 year has been awarded to D.B.S. by the Department of Biomedical Engineering, CWRU.

References

- 1.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. 2007. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 99, 1441–1454. ( 10.1093/jnci/djm135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasuda H. 2008. Solid tumor physiology and hypoxia-induced chemo/radio-resistance: novel strategy for cancer therapy: nitric oxide donor as a therapeutic enhancer. Nitric Oxide 19, 205–216. ( 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrova V, Annichiarico-Petruzelli M, Melino G, Amelio I. 2018. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 7, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojtkowiak JW, Verduzco D, Schramm KJ, Gillies RJ. 2011. Drug resistance and cellular adaptation to tumor acidic pH microenvironment. Mol. Pharm. 8, 2032–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rankin EB, Nam JM, Giaccia AJ. 2016. Hypoxia: signaling the metastatic cascade. Trends Cancer 2, 295–304. ( 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.05.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JM. 2002. Tumor microenvironment and the response to anticancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 1, 453–458. ( 10.4161/cbt.1.5.157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenza GL. 2003. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 721–732. ( 10.1038/nrc1187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moeller BJ, Cao Y, Li CY, Dewhirst MW. 2004. Radiation activates HIF-1 to regulate vascular radiosensitivity in tumors: role of reoxygenation, free radicals, and stress granules. Cancer Cell 5, 429–441. ( 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00115-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewhirst MW, Secomb TW, Ong ET, Hsu R, Gross JF. 1994. Determination of local oxygen-consumption rates in tumors. Cancer Res. 54, 3333–3336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmlinger G, Yuan F, Dellian M, Jain RK. 1997. Interstitial pH and pO2 gradients in solid tumors in vivo: high-resolution measurements reveal a lack of correlation. Nat. Med. 3, 177–182. ( 10.1038/nm0297-177) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaupel P, Kelleher DK, Höckel M. 2001. Oxygenation status of malignant tumors: pathogenesis of hypoxia and significance for tumor therapy. Semin. Oncol. 28(Suppl. 8), 29–35. ( 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90210-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raza A, Colley HE, Baggaley E, Sazanovich IV, Green NH, Weinstein JA, Botchway SW, MacNeil A, Haycock JW. 2017. Oxygen mapping of melanoma spheroids using small molecule platinum probe and phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Sci. Rep. 7, 10743 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-11153-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn JF, et al. 2002. Changes in oxygenation of intracranial tumors with carbogen: a BOLD MRI and EPR oximetry study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 16, 511–521. ( 10.1002/jmri.10192) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan X, River JN, Zamora M, Al-Hallaq HA, Karczmar GS. 2002. Effect of carbogen on tumor oxygenation: combined fluorine-19 and proton MRI measurements. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 54, 1202–1209. ( 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)03035-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishna MC, et al. 2002. Overhauser enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for tumor oximetry: coregistration of tumor anatomy and tissue oxygen concentration. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 99, 2216–2221. ( 10.1073/pnas.042671399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Šentjurc M, Čemažar M, Serša G. 2004. EPR oximetry of tumors in vivo in cancer therapy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 60, 1379–1385. ( 10.1016/j.saa.2003.10.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bratasz A, Pandian RP, Deng Y, Petryakov S, Grecula JC, Gupta N, Kuppusamy P. 2007. In vivo imaging of changes in tumor oxygenation during growth and after treatment. Magn. Reson. Med. 57, 950–959. ( 10.1002/mrm.21212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langan LM, Dodd NJF, Owen SF, Purcell WM, Jackson SK, Jha AN. 2016. Direct measurements of oxygen gradients in spheroid culture system using electron parametric resonance oximetry. PLoS ONE 11, e0160795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinogradov SA, Lo LW, Jenkins WT, Evans SM, Koch C, Wilson DF. 1996. Noninvasive imaging of the distribution in oxygen in tissue in vivo using near-infrared phosphors. Biophys. J. 70, 1609–1617. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79764-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun RD, Lanzen JL, Snyder SA, Dewhirst MW. 2001. Comparison of tumor and normal tissue oxygen tension measurements using OxyLite or microelectrodes in rodents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280, H2533–H2544. ( 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2533) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vukovic V, Haugland HK, Nicklee T, Morrison AJ, Hedley DW. 2001. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is an intrinsic marker for hypoxia in cervical cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 61, 7394–7398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda K, Okabe Y, Kadonosono T, Ueno T, Youssif BGM, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Nagasawa H. 2012. 2-nitroimidazole-tricarbocyanine conjugate as a near-infrared fluorescent probe of in vivo imaging of tumor hypoxia. Bioconjug. Chem. 23, 324–329. ( 10.1021/bc2004704) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhdanov AV, Ogurtsov TVI, Cormac DT, Papkovsky B. 2010. Monitoring of cell oxygenation and responses to metabolic stimulation by molecular oxygen sensing technique. Integr. Biol. 2, 443–451. ( 10.1039/c0ib00021c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller-Klieser WF, Sutherland RM. 1982. Oxygen tensions in multicell spheroids of two cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 45, 256–264. ( 10.1038/bjc.1982.41) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller-Klieser WF, Sutherland RM. 1984. Oxygen consumption and oxygen diffusion properties of multicellular spheroids from two different cell lines. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 180, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acker H, Carlsson J, Mueller-Klieser W, Sutherland RM. 1987. Comparative pO2 measurements in cell spheroids cultured with different techniques. Br. J. Cancer 56, 325–327. ( 10.1038/bjc.1987.197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone HB, Brown JM, Phillips TL, Sutherland RM. 1993. Oxygen in human tumors: correlations between methods of measurement and response to therapy: summary of a workshop held November 19–20, 1992, at the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. Radiat. Res. 136, 422–434. ( 10.2307/3578556) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaupel P, Höckel M, Mayer A. 2007. Detection and characterization of tumor hypoxia using pO2 histography. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 1221–1236. ( 10.1089/ars.2007.1628) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutherland RM, McCredie JA, Inch WR. 1971. Growth of multicell spheroids in tissue culture as a model of nodular carcinomas. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 46, 113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lankelma J. 2002. Tissue transport of anti-cancer drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des 8, 1987–1993. ( 10.2174/1381612023393512) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. 2006. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 583–592. ( 10.1038/nrc1893) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunz-Schughart LA, Freyer JP, Hofstaedter F, Ebner R. 2004. The use of 3-D cultures for high-throughput screening: the multicellular spheroid model. J. Biomol. Screen. 9, 273–285. ( 10.1177/1087057104265040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin RZ, Chang HY. 2008. Recent advances in three-dimensional multicellular spheroid culture for biomedical research. Biotechnol. J. 3, 1172–1184. ( 10.1002/biot.200700228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenzel C, et al. 2014. 3D high-content screening for the indentification of compounds that target cells in dormant tumor spheroid regions. Exp. Cell Res. 323 131–143. ( 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.01.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torisawa Y-s, Takagi A, Shiku H, Yasukawa T, Matsue T. 2005. A multicellular spheroid-based drug sensitivity test by scanning electrochemical microscopy. Oncol. Rep. 13, 1107–1112. ( 10.3892/or.13.6.1107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedrich J, Seidel C, Ebner R, Kunz-Schughart LA. 2009. Spheroid-based drug screen: considerations and practical approach. Nat. Protoc. 4, 309–324. ( 10.1038/nprot.2008.226) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta G, Hsiao AY, Ingram M, Luker GD, Takayama S. 2012. Opportunities and challenges for use of tumor spheroids as models to test drug delivery and efficacy. J. Control. Release 164, 192–204. ( 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perche F, Torchilin VP. 2012. Cancer cell spheroids as a model to evaluate chemotherapy protocols. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13, 1205–1213. ( 10.4161/cbt.21353) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franko AJ, Sutherland RM. 1979. Oxygen diffusion distance and development of necrosis in multicell spheroids. Radiat. Res. 79, 439–453. ( 10.2307/3575173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutherland RM, Sordat B, Bamat J, Gabbert H, Bourrat B, Mueller-Klieser W. 1986. Oxygenation and differentiation in multicellular spheroids of human colon carcinoma. Cancer Res. 46, 5320–5329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walenta S, Snyder S, Haroon ZA, Braun RD, Amin K, Brizel D, Mueller-Klieser W, Chance B, Dewhirst MW. 2001. Tissue gradients of energy metabolites mirror oxygen tension gradients in a rat mammary carcinoma model. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 51, 840–848. ( 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01700-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Achatz DE, Hupf C, Sperber M, Wegener J, Bange S, Lupton JM, Wolfbeis OS. 2013. Imaging of cellular oxygen via two-photon excitation of fluorescent sensor nanoparticles. Sens. Act. B: Chem. 188, 257–262. ( 10.1016/j.snb.2013.06.087) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grimes DR, Kelly C, Bloch K, Partridge M. 2014. A method for estimating the oxygen consumption rate in multicellular tumour spheroids. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20131124 ( 10.1098/rsif.2013.1124) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutherland RM, Durand RE. 1984. Growth and cellular characteristics of multicell spheroids. Recent Results Cancer Res. 95, 24–49. ( 10.1007/978-3-642-82340-4_2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlsson J, Acker H. 1988. Relations between pH, oxygen partial pressure and growth in cultured cell spheroids. Int. J. Cancer 42, 715–720. ( 10.1002/ijc.2910420515) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freyer JP, Sutherland RM. 1986. Proliferative and clonogenic heterogeneity of cells from EMT6/Ro multicellular spheroids induced by the glucose and oxygen supply. Cancer Res. 46, 3513–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver VM, Bissell MJ. 1999. Functional culture models to study mechanisms governing apoptosis in normal and malignant mammary epithelial cells. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 4, 193–201. ( 10.1023/A:1018781325716) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutherland RM, Durand RE. 1976. Radiation response of multicell spheroids—an in vitro tumour model. Curr. Top. Radiat. Res. Q. 11, 87–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Wang W, Yu W, Xie Y, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Ma X. 2005. Development of an in vitro multicellular tumor spheroid model using microencapsulation and its application in anticancer drug screening and testing. Biotechnol. Prog. 21, 1289–1296. ( 10.1021/bp050003l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dmitriev RI, Zhdanov AV, Nolan YM, Papkovsky DB. 2013. Imaging neurosphere oxygenation with phosphorescent probes. Biomaterials 34, 9307–9317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papkovsky DB, Dmitriev RI. 2018. Quenched phosphorescence detection of molecular oxygen. Applications in life sciences. London, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheth DB, Gratzl M. 2013. Differential linear scan voltammetry: analytical performance in comparison with pulsed voltammetry techniques Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 5539–5547. ( 10.1007/s00216-013-6979-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Hutchins LD. 1985. Thin-layer electrochemical detector with a glassy carbon electrode coated with a base-hydrolyzed cellulosic film. Anal. Chem. 57, 1536–1541. ( 10.1021/ac00285a010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Hutchins-Kumar LD. 1986. Cellulose acetate coated mercury film electrodes for anodic stripping voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 58, 402–407. ( 10.1021/ac00293a031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gottesman M, Ling V. 2006. The molecular basis of multidrug resistance in cancer: the early years of P-glycoprotein research. FEBS Lett. 580, 998–1009. ( 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yi C, Gratzl M. 1998. Continuous in situ electrochemical monitoring of doxorubicin efflux from sensitive and drug resistant cancer cells. Biophys. J. 75, 2255–2261 ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77670-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu H, Gratzl M. 1999. Monitoring drug efflux from sensitive and drug resistant single cancer cells with microvoltammetry. Anal. Chem. 71, 2821–2830. ( 10.1021/ac9811773) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wojtkowiak JW, Verduzco D, Schramm KJ, Gillies RJ. 2011. Drug resistance and cellular adaptation to tumor acidic pH microenvironment. Mol. Pharm. 8, 2032–2038. ( 10.1021/mp200292c) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ingram M, Techy GB, Saroufeem R, Yazan O, Narayan KS, Goodwin TJ, Spaulding GF. 1997. Three-dimensional growth patterns of various human tumor cell lines in simulated microgravity of a NASA bioreactor. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 33, 459–466. ( 10.1007/s11626-997-0064-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. 1998. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp. Cell Res. 238, 262–272. ( 10.1006/excr.1997.3858) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelm JM, Timmins NE, Brown CJ, Fussenegger M, Nielsen LK. 2003. Method for generation of homogeneous multicellular tumor spheroids applicable to a wide variety of cell types. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 83, 173–180. ( 10.1002/bit.10655) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haisler W, Gage JA, Tseng H, Killian TC, Souza GR. 2013. Three-dimensional cell culturing by magnetic levitation. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1940–1949. ( 10.1038/nprot.2013.125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heffeman JM, Overstreet DJ, Srinivasan S, Le LD, Vernon BL, Sirianni RW. 2015. Temperature responsive hydrogels enable transient three-dimensional tumor cultures via rapid cell recovery. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 104A, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y, Kumacheva E. 2018. Hydrogel microenvironments for cancer spheroid growth and drug screening. Sci. Adv. 4, eaas8998 ( 10.1126/sciadv.aas8998) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grimshaw MJ, Cooper L, Papazisis K, Coleman JA, Bohnenkamp HR, Chiapero-Stanke L, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Burchell JM. 2008. Mammosphere culture of metastatic breast cancer cells enriches for tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 10, R52 ( 10.1186/bcr2106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huisken J, Swoger J, Del Bene F, Wittbrodt J, Stelzer EH. 2004. Optical sectioning deep inside live embryos by selective plane illumination microscopy. Science 305, 1007–1009. ( 10.1126/science.1100035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahuja P, Peshkova MA, Hemphill B, Gratzl M. 2014. Minimizing color interference from biomedical samples in optode-based measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 12, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahuja P, Nair S, Narayan S, Gratzl M. 2015. Functional imaging of chemically active surfaces with optical reporter microbeads. PLoS ONE 10, e0136970 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0136970) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zanoni M, Piccinini F, Piccinini F, Arienti C, Zamagni A, Santi S, Polico R, Bevilacqua A, Tesei A. 2016. 3D tumor spheroid models for in vitro therapeutic screening: a systematic approach to enhance the biological relevance of data obtained. Sci. Rep. 6, 19103 ( 10.1038/srep19103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]