Abstract

Neonatal brain injury from hypoxia-ischemia (HI) causes major morbidity. Piglet HI is an established method for testing neuroprotective treatments in large, gyrencephalic brain. Though many neurobehavior tests exist for rodents, such tests and their associations with neuropathologic injury remain underdeveloped and underutilized in large, neonatal HI animal models. We examined whether spatial T-maze and inclined beam tests distinguish cognitive and motor differences between HI and sham piglets and correlate with neuropathologic injury. Neonatal piglets were randomized to whole-body HI or sham procedure, and they began T-maze and inclined beam testing 17 days later. HI piglets had more incorrect T-maze turns than did shams. Beam walking time did not differ between groups. Neuropathologic evaluations at 33 days validated the injury with putamen neuron loss after HI to below that of sham procedure. HI decreased the numbers of CA3 pyramidal neurons but not CA1 pyramidal neurons or dentate gyrus granule neurons. Though the number of hippocampal parvalbumin-positive interneurons did not differ between groups, HI reduced the number of CA1 interneuron dendrites. Piglets with more incorrect turns had greater CA3 neuron loss, and piglets that took longer in the maze had greater CA3 interneuron loss. The number of putamen neurons was unrelated to T-maze or beam performance. We conclude that neonatal HI causes hippocampal CA3 neuron loss, CA1 interneuron dendritic attrition, and putamen neuron loss at 1-month recovery. The spatial T-maze identifies learning and memory deficits that are related to loss of CA3 pyramidal neurons and parvalbumin-positive interneurons independent of putamen injury.

Keywords: newborn, learning, hypoxia, hippocampus, cognition, putamen

1. Introduction

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) from birth asphyxia causes persistent and potentially lifelong neurologic disabilities, even when therapeutic hypothermia is used [1, 2]. Translational research with animal models of brain hypoxia-ischemia (HI) is essential to identifying and advancing neuroprotective treatments. Large-animal models, including neonatal piglets [3–6], sheep [7], and nonhuman primates [8], are valuable for testing brain injury mechanisms and potential therapeutics for HIE that are relevant to clinical medicine. The large gyrencephalic brain permits detailed and focused pathologic examinations in distinct, human-relevant regions of interest that are vulnerable to HI [9, 10]. HI injures neonatal piglet brain regions that correspond to those of human term newborns [11]. However, the translational value of the piglet HI model has not been fully realized owing to a paucity of validated neurobehavior tests with known associations to specific neuropathologic injury. Given the risk of long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities in survivors of HIE [1, 2], including learning deficits and apraxia, large-animal tests that identify HI-related cognitive and motor deficits with specific associations to regional neuropathology would advance translational research.

The hippocampus, with its critical role in learning and memory firmly established in humans [12], attracts attention in pig models because the anatomical placement of the hippocampus is mostly in the temporal lobe [11]. Piglet hippocampus is therefore intermediate between rodents and primates because primate hippocampus is entirely in the temporal lobe [13]. The piglet’s hippocampal structure is also more similar to human than to rodent hippocampus [13] and has well-defined interneuron populations [14].

Most piglet neurobehavior tests focus on consciousness, gross cranial nerve function, and gross motor skills, including walking, feeding, ability to stand from a supine position, and overall activity [15–17]. The piglet beam test [18] is a more specific motor measure that also captures motivation to walk a beam. However, most of these tests lack granularity and are generally used to assess short-term recovery. None of these tests evaluate learning or memory. Spatial T-maze tests with visual cues have been developed and validated as a cognitive test for piglets with traumatic brain injury or cognitive dysfunction from scopolamine [19, 20]. The piglet’s ability to learn the location of milk in a maze by learning and memorizing visual cues has been attributed to hippocampal function based on rodent studies [20] and human hippocampal activation during spatial navigation [21]. In piglets with HI brain injury, it is unknown whether T-maze and beam tests can identify cognitive and motor deficits. Moreover, clear associations between poor T-maze performance and hippocampal injury have not been established in piglet HI.

We conducted T-maze and inclined beam tests in piglets randomized to HI brain injury or sham procedure with long-term survival. We hypothesized that HI-injured piglets would have more deficits in T-maze and inclined beam testing than sham piglets. We also theorized that the numbers of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, interneurons, and interneuron dendrites would correlate to test performance.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal comfort was ensured at all times. All protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the United States Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care also followed the National Institutes of Health Guidelines.

We previously published our HI injury protocol [3, 9, 22, 23]. Neonatal male piglets (3 days old, 1–2.5 kg) were randomized to HI or sham procedure. Piglets were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in a 50%/50% nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture through a nose cone and then intubated. Mechanical ventilation was initiated to maintain normocapnea, the inspired fractional oxygen (FiO2) concentration was reduced to 30%, and the isoflurane was decreased to 2% in a 70%/30% nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture. The external jugular vein was cannulated for intravenous (IV) fluid and medication administration. The femoral artery was cannulated for continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring and arterial blood gas sampling. The surgical placement of femoral artery catheter was carefully done to minimize muscle damage and tissue bruising in the leg. Fentanyl (20 μg/kg bolus plus 20 μg/kg/h, IV) in normal saline with 5% dextrose (4 mL/kg/h) was started. After the fentanyl was initiated, the isoflurane was discontinued and the piglets remained anesthetized with 70%/30% nitrous oxide/oxygen and fentanyl infusion. Thus, the isoflurane exposure occurred only during intubation and placement of the femoral catheters, which took approximately 15 min. This anesthetic does not affect normal, developmental apoptosis in cortex [10], white matter [9], or putamen [24]. All piglets received a bolus of 0.2 mg/kg vecuronium to prevent ventilatory effort during the hypoxia-asphyxia protocol and to ensure that all groups received the same anesthetic. We targeted a rectal temperature of 38.5–39.5°C, which is normothermic for swine, using a warming blanket and heating lamps. Sham piglets received the same treatment as HI piglets but without hypoxia and asphyxic cardiac arrest. We checked the piglets’ weights daily while they were housed in the laboratory. Once the piglets transitioned to solid food at 2–3 weeks of age, they were moved to the central animal housing facility.

2.1. HI brain injury from hypoxic-asphyxic cardiac arrest

We decreased the FiO2 to 10% for 45 min to achieve an oxyhemoglobin saturation of approximately 30%. Mechanical ventilation maintained normocapnia during hypoxia. Then, 5 min of room air was provided to re-oxygenate the heart. This interlude is required for successful cardiac resuscitation in this model. Asphyxia was produced by clamping the endotracheal tube for 8 min. The piglets were resuscitated by chest compressions, ventilation with FiO2 50%, and epinephrine (100 μg/kg, IV). After return of spontaneous circulation, the FiO2 was decreased to 30% in a 70%/30% nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture. Temperature corrected blood gases were monitored. Metabolic acidosis and hypocalcemia were corrected with sodium bicarbonate and calcium, as needed. Piglets emerged from anesthesia approximately 3 h after resuscitation from HI or time equivalent in sham-operated piglets. After full recovery, none of the piglets had apparent vision impairments based on their abilities to navigate play areas, locate and drink milk, and interact with other piglets.

2.2. Spatial T-maze

The piglets were fasted for approximately 5 h before testing according to protocols approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. One investigator (RS), who was blinded to HI or sham condition, conducted the T-maze habituation, testing, and measurements to ensure consistency and minimize anxiety for the piglets. Single-operator testing is important because some piglets display behavior changes, including distractibility and excitability, when they encounter a new person. No other people or piglets were permitted in the room during the experiments. The maze was surrounded by a large, white, opaque curtain to prevent distractions for the piglet.

We built a clear, Plexiglas spatial T-maze based on a published construction [20]. The T-maze dimensions and visual cues, which were secured to the curtain, are shown in figure 1. The maze walls were 2 feet high. The piglet could enter by the north or south arms of the maze. The piglets were placed into a holding pen located in the north or south arms of the maze, and a clear Plexiglas barrier was lifted to open the pen and permit the piglet to enter the maze. Milk bowls were placed in the east and west arms, each containing identical amounts of chocolate milk. The bowls were identical, plastic, and had perforated lids to ensure identical odors. Only one arm of the maze had a bowl with a lid that could be opened to access the milk. The bowl in the opposite arm had a tightly closed lid. The maze was cleaned with 70% ethanol before and after each use.

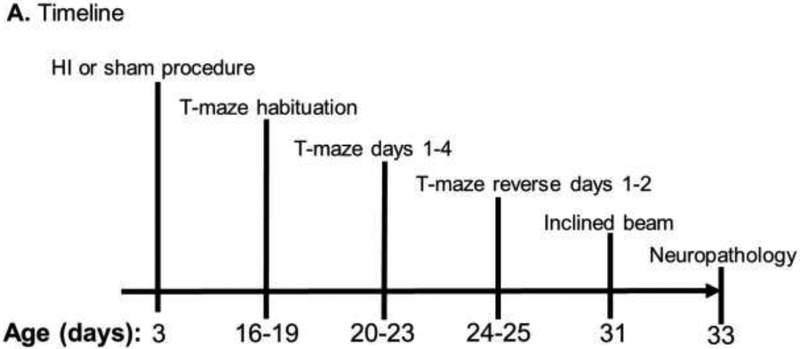

Figure 1.

Protocol timeline and spatial T-maze diagram. (A) Timeline of hypoxic-ischemic (HI) injury or sham procedure, T-maze and inclined beam testing, and euthanasia for histologic examination of the brain. (B) During T-maze days 1–4, the accessible milk was located near the red triangle in the east arm. Piglets alternated entering the maze through the north or south arms. (C) For reverse days 1–2, the milk was moved to the blue triangle in the west arm. Piglets again alternated entering the maze through the north or south arms.

On days-of-life 16–19, the piglets were placed in the T-maze for habituation (Figure 1A). Testing began 17 days after HI or sham procedure and lasted 4 days (days-of-life 20–23). In 10 trials/day the piglets were tested for their ability to learn the accessible milk’s location near the red triangle in the maze’s east arm (Figure 1B). For trial 1, piglets were placed into the maze at the north arm, and a clear Plexiglas barrier blocked the other entry arm. For trial 2, the piglets were put into the maze from the south arm. Each trial alternated north or south entries to avoid the possibility that the piglets could preferentially turn in one direction, which is related to striatal function. Requiring the piglets to rely on visual cues to locate the accessible milk tests spatial navigation and hippocampal function [25]. The number of correct turns and time to reach the milk was recorded. The piglet was coded as having turned if the pelvic girdle passed the central point of the maze.

On day-of-life 24, we began 2 days of reverse testing by moving the accessible milk to the blue square in the maze’s west arm (Figure 1C). Piglets were again placed into the maze from alternating north and south arms during 10 trials/day across 2 days. The same investigator (RS) recorded the number of correct turns and time to reach the accessible milk.

2.3. Inclined beam

The investigator who conducted the T-maze protocol and who was blinded to HI or sham condition also conducted the beam testing to minimize anxiety for the piglets. The inclined beam test was done on the same cohorts of piglets tested in the T-maze. An inclined beam (6 feet long, 14 inches wide) was placed at an approximately 20 degree angle against a 23-inch high platform with a bowl of milk. Plexiglas walls were added to the sides of the beam for safety. The piglets were fasted for approximately 5 h prior to testing and habituated to the beam on day of life 31. Testing began the following day when piglets were given 6 trials to walk up the beam. The trial ended at 20 s. If the pig did not try to walk up the beam, it was placed at the bottom of the beam again to start another 20-s trial. All beam-walking trials were video recorded for later evaluation by RS.

2.4. Neuropathology

The piglets were deeply anesthetized and euthanized on day-of-life 33 with Beuthanasia (50 mg/kg pentobarbital plus 6.4 mg/kg phenytoin). They were perfused transcardially with cold phosphate-buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed hemi-brains (right side) were embedded in paraffin and cut into 10μm coronal sections for hematoxylin and eosin staining of anterior hippocampus (temporal hippocampus) and of striatal sections that contained the putamen. Slides were matched from each animal by anteroposterior anatomic level.

We used the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin to mark a subset of GABAergic hippocampal interneurons by immunohistochemistry (IHC) per our previously published protocols [3, 9, 23]. Antigen retrieval with 20-min exposure to citrate buffer (10 mM citric acid in 0.05% Tween 20 [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO]) was followed by tissue blocking in 3% normal goat serum and IHC with the primary antibody rabbit anti-parvalbumin (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), the secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit (1:20, Sigma-Aldrich), and rabbit peroxidase anti-peroxidase soluble complex antibody (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich). The primary antibody to parvalbumin is highly specific as determined by western blotting [26]. We used 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate to disclose parvalbumin immunoreactivity as brown followed by a cresyl violet stain to identify the surrounding neurons and glia as light blue. Negative control slides were generated by incubating the slides with rabbit, non-immune IgG in equivalent concentration to the primary antibody.

One investigator (JKL), who was blinded to piglet cohort and the T-maze and beam data, counted surviving pyramidal neurons in the Cornu Ammonis subfields CA1 and CA3; dentate gyrus granule neurons; and putamen neurons at 400x magnification. All neurons in CA1, CA3, and dentate were counted in matched anterior levels of hippocampus. One slide per pig was analyzed. The hippocampal subfields were defined based on known pig anatomy [13]. Hippocampal neurons were counted only in temporal hippocampus. Putamen neurons were quantified from 8–10 non-overlapping microscope fields, and the mean count from these fields was used for the statistical analysis. One slide at the striatal anatomic level was analyzed per pig. Surviving neurons were identified by their large oval or round cell body (approximately 8–12 μm in diameter), prominent nucleolus or nucleoli, open nucleus with chromatin strands, intact nuclear and cell membranes, normal thin rim of cytoplasm, and absence of apoptotic or ischemic morphology [10].

In addition, JKL counted the number of all parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneuron cell bodies in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus. The large interneurons were identified by their dark brown stain and often multipolar cell body morphology. All parvalbumin-immunoreactive dendrites in or adjacent to the pyramidal neuron layer of CA1 were also counted and identified as large, dark brown processes, many decorated with axondendritic boutons. Thinner processes, which were likely to be axons, were not counted. Dendrites were counted only in CA1 because they are longitudinally oriented in this region and thus easier to identify as distinct processes. A second investigator (LJM) screened for counter-reliability.

2.5. Statistical methods

Data were analyzed and graphs were generated in SigmaPlot (v.14.0, San Jose, CA) and GraphPad Prism 5 (v.5, LaJolla, CA). T-maze data were analyzed as the proportion of correct turns and the mean time to reach the milk across 10 trials on each day. The total number of surviving neurons in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus; mean number of surviving neurons in putamen; total number of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus; and total number of parvalbumin-positive dendrites in CA1 were analyzed.

We first tested the data distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk normality and the Brown-Forsythe equal variance tests. When data passed both tests of normality and equal variance, we used t-tests to analyze differences between HI and sham piglets in T-maze turns, time to reach the milk, average time to walk up the beam, neuron and interneuron counts, number of dendrites, and body weight. If the data did not pass both normality and equal variance tests, we used Mann Whitney Rank Sum tests. Paired, within-pig comparisons of T-maze turns and time to reach the milk versus the number of neurons, interneurons, and dendrites in each region of interest were conducted with Spearman correlations. To assess learning during the T-maze training days, we analyzed the proportion of correct turns and time to reach the milk across days 1–4 by repeated measures analysis of variance with post-hoc Holm Sidak pairwise comparisons or Friedman repeated measures analysis of variance on ranks with post-hoc Dunn’s pairwise comparisons. We analyzed T-maze learning during days 1–4 for HI and sham piglets separately. The time to walk up the inclined beam across 6 trials was analyzed by Friedman repeated measures analysis of variance on ranks with post-hoc Dunn’s tests.

After confirming that the blood gas and physiology data were normally distributed, we used repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance (factor 1: HI or sham; factor 2: time) with post-hoc Holm Sidak pairwise comparisons to analyze differences in temperature, blood pressure, blood gas, and electrolyte data. We present two-tailed p-values, and statistical significance is assumed when p<0.05.

2.6. Sample size

We did not have a priori data to guide our sample size selection. One study reported that scopolamine significantly reduced the number of correct T-maze turns in 5 piglets compared to that of 5 control pigs [20]. In another study, four rhesus macaque monkeys with hippocampal lesions performed poorer on memory tests than did control monkeys without hippocampal injury [27]. We selected 5–6 piglets/group to test for differences in T-maze performance between HI and sham piglets.

3. Results

Six piglets received HI injury and six received sham procedure. One piglet died several days after HI. Thus, 5 HI and 6 sham piglets underwent the T-maze and inclined beam tests and neuropathologic evaluations. No overt clinical seizures were observed in the surviving HI piglets during the 1-month recovery period.

3.1. Physiology

Physiology and blood chemistry data are presented in Table 1. HI significantly affected temperature (p=0.037). In post-hoc comparisons, temperature increased from baseline to the 1-h recovery time point in shams (p=0.037), and shams had higher temperature than did HI piglets at 1 h (p=0.006). The mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was affected by time independently (p=0.026) and also interactively by time and HI (p=0.020). Blood pressure decreased across time among HI piglets (p=0.005). The pH changed with time (p=0.016), and HI and time interacted in their effect on pH (p=0.010). The pH at 1 h was lower than that at baseline among HI piglets (p=0.002). No statistical differences were observed for the arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, oxyhemoglobin saturation, sodium, or hemoglobin levels. At 2 weeks of age, HI piglets weighed 3.14 kg (SD: 0.73) and shams weighed 3.03 kg (SD: 0.97; p>0.05).

Table 1.

Blood chemistry and physiologic data

| Parameter/Group | n | Baseline | Hypoxia 42 min | Asphyxia 8 min | ROSC 1 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C)* | |||||

| HI | 5 | 37.6±0.5 | 37.5±0.1 | ||

| Sham | 6 | 37.9±0.8 | 38.7±0.3 | ||

| pH† | |||||

| HI | 5 | 7.39±0.05 | 7.29±0.09 | 6.83±0.13 | 7.33±0.04 |

| Sham | 6 | 7.39±0.05 | 7.39±0.05 | ||

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | |||||

| HI | 5 | 37±4 | 42±5 | 101±12 | 39±2 |

| Sham | 6 | 39±3 | 39±4 | ||

| SaO2 (%) | |||||

| HI | 5 | 100±0.5 | 30±2 | 6±2 | 100±0 |

| Sham | 6 | 100±0 | 100±0.4 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| HI | 5 | 7.8±0.7 | 8.3±0.6 | ||

| Sham | 6 | 7.9±1.4 | 8.0±1.5 | ||

| Sodium (mEq/dL) | 5 | ||||

| HI | 6 | 146±9 | 148±7 | ||

| Sham | 143±2 | 142±4 | |||

| Mean arterial blood | |||||

| pressure (mmHg)‡ | |||||

| HI | 5 | 72±12 | 65±13 | 26±11 | 53±17 |

| Sham | 6 | 69±17 | 70±18 | ||

HI = hypoxia-ischemia; ROSC = Return of spontaneous circulation.

All data are shown as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed by repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance on ranks (factor 1: HI or sham; factor 2: baseline or ROSC 1 h time points) with post-hoc Holm Sidak pairwise tests.

HI significantly affected temperature (p=0.037). In post-hoc comparisons, sham piglets had higher temperatures than did HI piglets at ROSC 1 h (p=0.006). The temperature of sham piglets increased between baseline and 1 h recovery (p=0.037).

Time affected pH (p=0.016), and time and HI interactively affected pH (p=0.010). In post-hoc comparisons, pH at 1 h was lower than that at baseline among HI piglets (p=0.002).

The mean arterial blood pressure was affected by time (p=0.026) and interactively by time and HI (p=0.020). Blood pressure declined across time in HI piglets (p=0.005).

3.2. Spatial T-maze

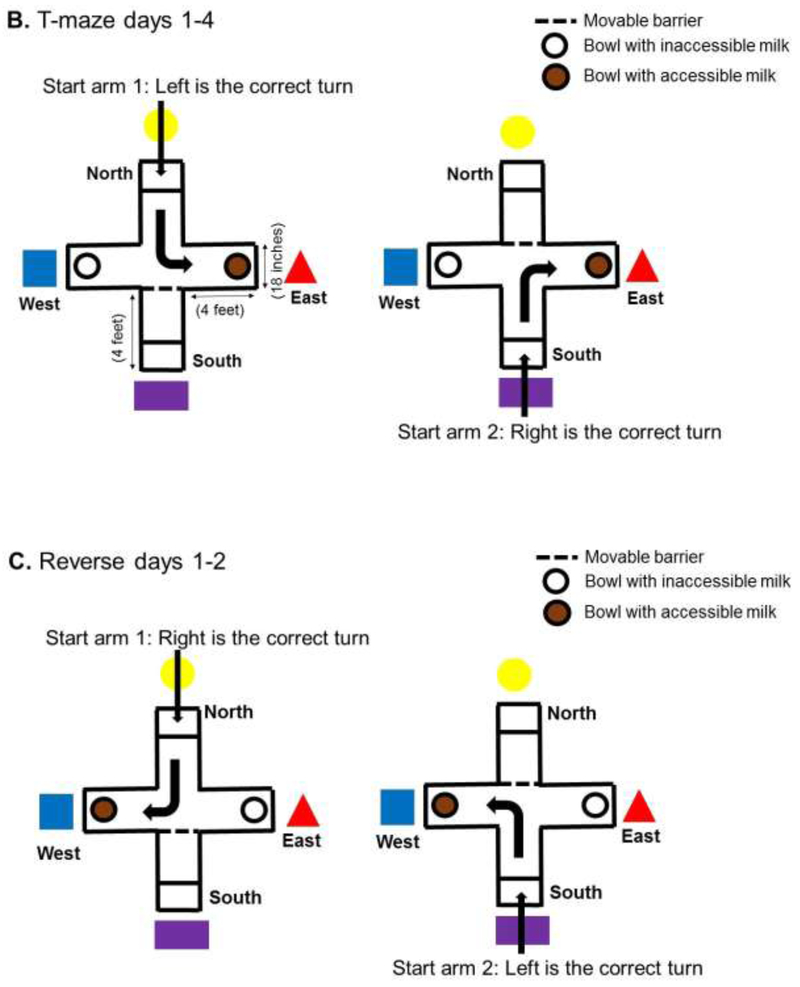

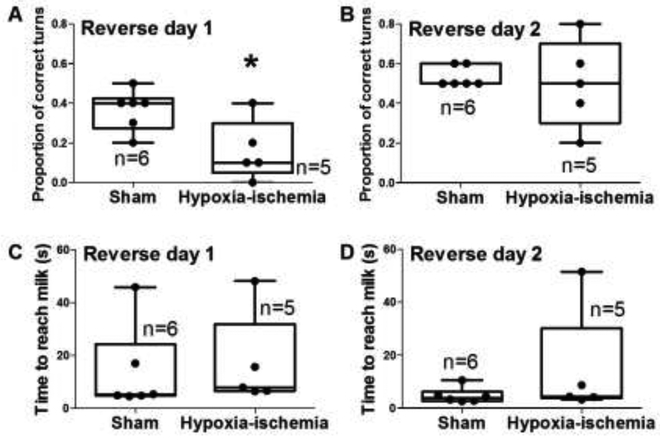

Figure 2 shows the piglets’ progress during T-maze training with the accessible milk in the east arm (near the red triangle). Sham piglets increased their proportion of correct turns across the four training days (p=0.046; Figure 2A). No statistically significant differences were identified in pairwise comparisons of training days. Shams also reached the accessible milk faster as the training days progressed (p<0.001; Figure 2B). In post-hoc comparisons, the time to reach the milk was slower on day 1 than on days 2, 3, and 4 (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). In contrast, piglets with HI brain injury did not show a difference in the proportion of correct turns (p>0.05) or time to reach the milk (p>0.05) across training days (Figure 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Hypoxic-ischemic (HI) brain injury reduces learning in the spatial T-maze. (A) The proportion of correct turns to reach the accessible milk increased across training days in sham piglets (p=0.046). (B) Sham piglets also reached the accessible milk faster with progressive training days (p<0.001). In post-hoc comparisons, the time to reach the milk was longer on day 1 than on days 2, 3, and 4 (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons. (C, D) Piglets with HI brain injury did not show differences in the proportion of correct turns (p>0.05) or time to reach the milk (p>0.05) during 4 days of training.

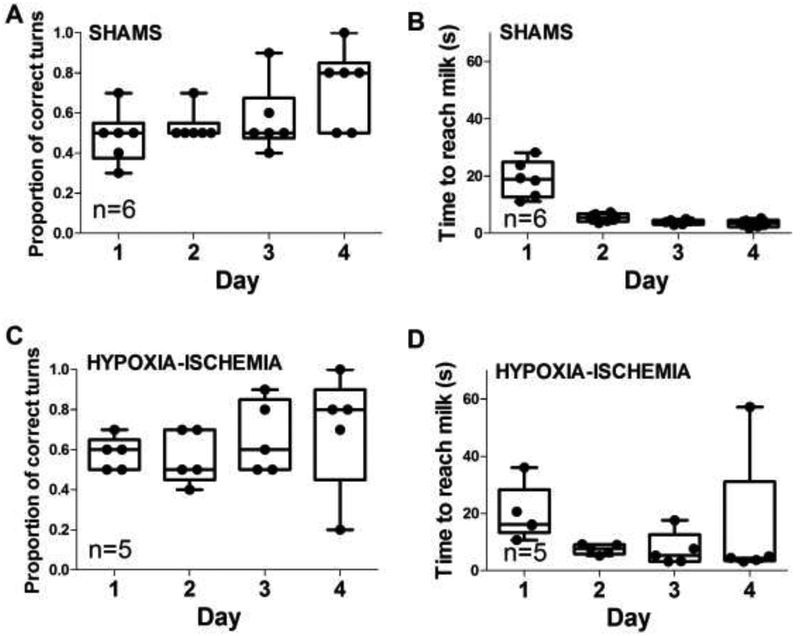

During the first reverse day with the accessible milk in the maze’s west arm (near the blue square), HI piglets had a lower proportion of correct turns than did sham piglets (p=0.025; Figure 3A; video files “VIDEO_HI pig T-maze reverse day 1” and “VIDEO_sham pig T-maze reverse day 1”). The proportion of correct turns did not differ on reverse day 2 (p>0.05; Figure 3B). The time to reach the milk also did not differ on reverse days 1 or 2 between HI and sham groups (p>0.05 for both; Figure 3C, D).

Figure 3.

Hypoxia-ischemia (HI)-injured piglets took longer to learn the reverse maze than did the sham-operated piglets. (A) HI piglets had fewer correct turns on reverse day 1 than did the sham piglets. *p<0.05. (B–D) The proportion of correct turns on reverse day 2 and time to reach the milk on reverse days 1 and 2 did not differ between HI and sham groups. Box plots with whiskers (5–95th percentiles) are shown. Each circle represents one pig.

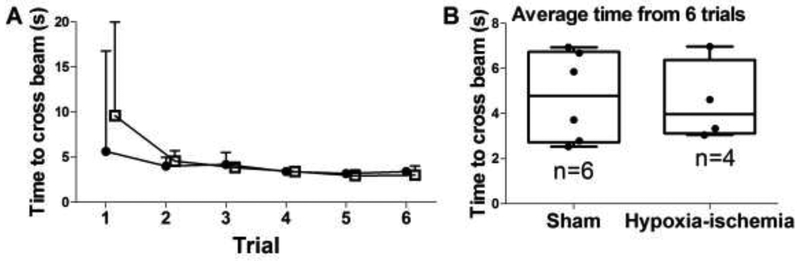

3.3. Inclined beam test

One HI pig did not walk up the beam and was excluded from the analysis, though this pig seemed overtly normal without paresis or ataxia. The time required to walk up the beam decreased across the six trials in both HI (p=0.007; n=4) and sham (p=0.002; n=6) groups (Figure 4A). Post-hoc comparisons for HI piglets showed that they reached the top of the beam faster on trial 5 than on trial 1 (p=0.020). The sham piglets crossed the beam faster on trials 4 (p=0.030) and 5 (p=0.014) than on trial 1. The average time from 6 beam trials did not differ between sham and HI piglets (p>0.05; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Time to walk across the inclined beam. (A) Over the course of six trials, time to walk up the beam decreased for both piglets that received HI brain injury (p=0.007; n=4; closed circles) and those that received sham procedure (p=0.002; n=6; open squares). (B) In post-hoc comparisons, HI piglets reached the top of the beam faster on trial 5 than on trial 1 (p=0.020). The sham piglets had faster walking times on trials 4 (p=0.030) and 5 (p=0.014) than on trial 1. The medians and interquartile ranges are shown.

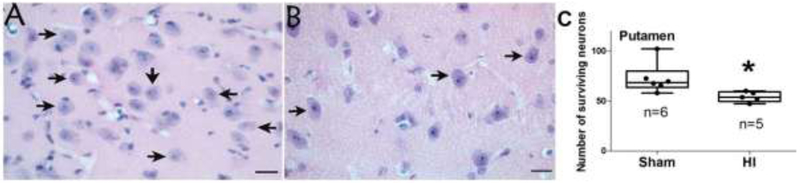

3.4. Surviving neurons

We validated the HI injury by counting the number of surviving neurons in putamen because this highly vulnerable region is a sensitive and reproducible indicator of piglet HI injury [11, 28]. HI piglets had fewer surviving neurons in putamen than did sham piglets (p=0.006; Figure 5). In paired (within pig) comparisons, the number of putamen neurons did not correlate with T-maze performance (p>0.05 for all comparisons; Supplemental Figure 1) or with beam walking time (p>0.05; data not shown).

Figure 5.

Surviving neurons in putamen. (A) A sham piglet had numerous neurons in putamen (arrows). (B) A piglet resuscitated from hypoxia-ischemia (HI) had fewer surviving neurons (arrows). Photos were taken at 400x. Scale bars = 20 μm. (C) HI reduced the number of neurons to below that of sham procedure (*p<0.05).

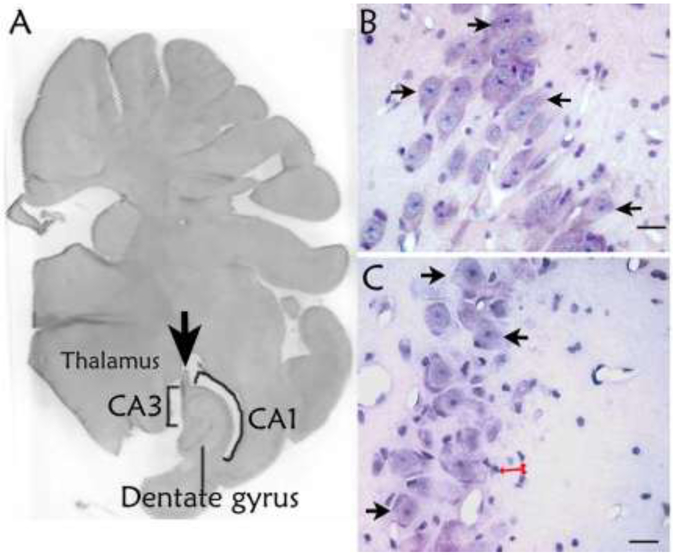

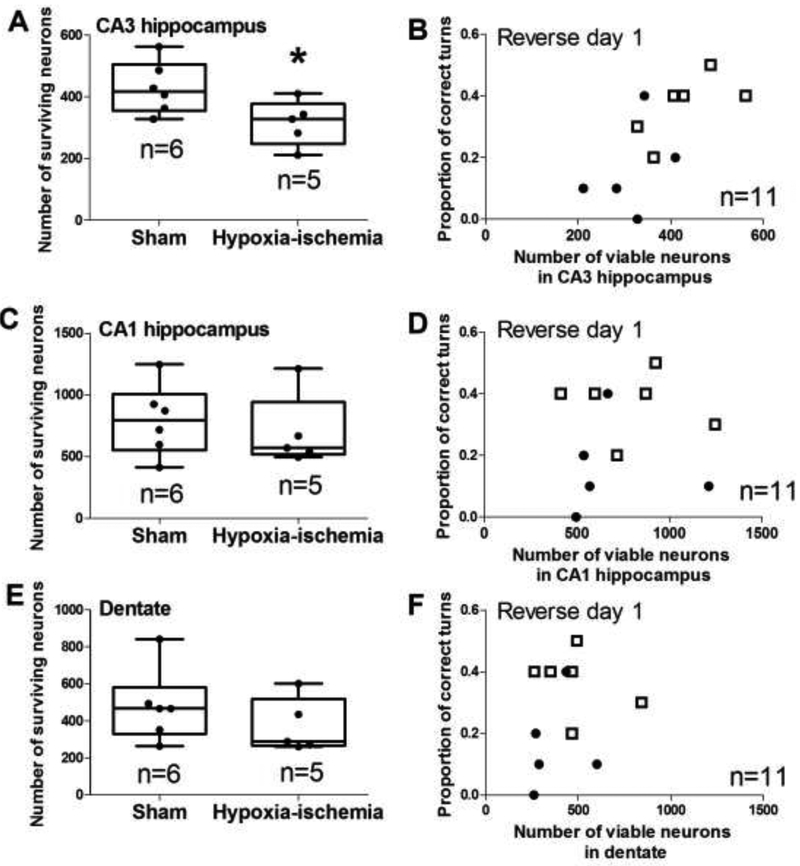

Figure 6 shows the hippocampal anatomy and histology. We counted the pyramidal neurons in the temporal hippocampus CA1 and CA3 subfields and dentate gyrus granule neurons (Figure 6). Piglets resuscitated from HI had fewer surviving neurons in CA3 than did shams (p=0.044; Figures 6B, 6C, and 7A). CA3 neuron loss was qualitatively corroborated by the presence of small, non-neuronal cells that typify a reactive change to neurodegeneration after HI but not sham procedure (Figure 6B, C). The number of surviving CA3 neurons correlated with the proportion of correct T-maze turns on reverse day 1 among all piglets (n=11; r=0.716; p=0.006; Figure 7B). CA3 neuron counts were not related to T-maze time on day 4, reverse day 1, or reverse day 2 nor to T-maze turns on day 4 or reverse day 2 (p>0.05 for all comparisons; Supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 6.

Histologic evaluation of hippocampal injury. (A) Pig brain section showing the hippocampal anatomic level studied. The arrow identifies the fornix. This section was stained with hematoxylin & eosin and converted to grayscale. The photo was taken at 10x. (B) A sham piglet’s CA3 shows numerous surviving neurons (arrows). (C) Fewer surviving neurons (arrows) were observed in the CA3 of a piglet that underwent hypoxia-ischemia. The injured CA3 also had reactive changes identified by multiple small non-neuronal cells (red arrows). Though the identity of these reactive cells was not determined, their morphology is consistent with microglia. Panels B and C were photographed at 400x. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Figure 7.

Surviving neuron counts in hippocampus and the proportion of correct T-maze turns on reverse day 1. (A) Hypoxia-ischemia (HI) decreased the number of neurons in CA3 to below that of piglets that underwent sham procedure (*p<0.05). (B) The number of surviving neurons in CA3 correlated with the proportion of correct T-maze turns (r=0.759; p<0.05). (C–F) The number of neurons in CA1 and dentate gyrus did not differ between sham and HI piglets and did not correlate with the proportion of correct turns in the maze. In panels A, C, and E, each circle represents one pig. In panels B, D, and F, sham piglets are represented by open squares, and HI piglets are represented by closed circles.

The numbers of surviving neurons in CA1 and dentate gyrus did not differ between HI and sham piglets (p>0.05 for both), and they did not correlate with the proportion of correct turns on reverse day 1 (r=0.196 for CA1; r=0.450 for dentate; p>0.05 for both; Figures 7C–F). Surviving neuron counts in CA1 and dentate gyrus also failed to correlate with time to reach the milk on any day or with turns on reverse day 2 (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Finally, the numbers of neurons in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus were not correlated to beam walking time (p>0.05 for all comparisons; data not shown).

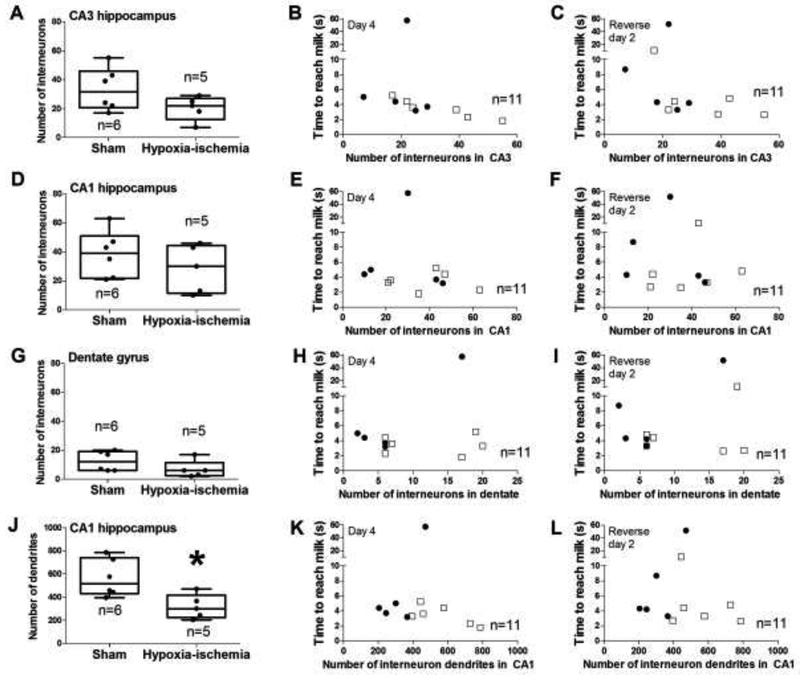

3.5. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneuron cell bodies and dendrites

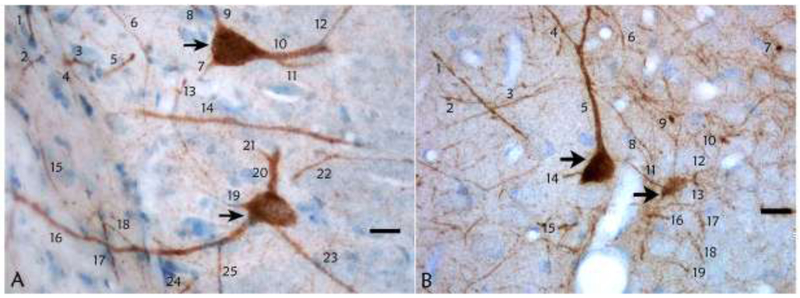

Figures 8A and 8B show examples of histologic interneuron identification and dendrite counting. Though the number of parvalbumin-positive interneuron cell bodies in CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus did not differ between HI and sham groups (p>0.05 for all comparisons; Figure 9A, D, G), piglets resuscitated from HI had fewer dendrites in CA1 than did shams (p=0.017; Figure 9J). A greater number of CA3 interneuron cell bodies correlated with faster time to reach the milk on day 4 and reverse day 2 (r= −0.870, p<0.001 for day 4; r= −0.623, p=0.035 for reverse day 2; Figure 9B and C). No other associations were identified between the regional numbers of interneuron cell bodies or dendrites and T-maze performance (p>0.05 for all comparisons).

Figure 8.

Parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons and dendrites in hippocampus. (A) Parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons in CA1 are identified by the arrows in a sham piglet. Large, parvalbumin-positive processes were identified as dendrites and counted. Thin processes, which were likely to be axons, were not counted. (B) Parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons (arrows) and dendrite counts in the CA1 of a piglet with hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Photos were taken at 400x. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Figure 9.

Comparison of parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons and dendrites to hypoxic-ischemic (HI) injury or sham procedure and to T-maze performance. (A-C) Though CA3 interneuron counts did not differ between HI and sham pigs, the number of CA3 interneurons correlated with the time to reach the milk on day 4 (r= −0.870; p<0.001) and on reverse day 2 (r= ‒0.623; p=0.035). (D-I) The number of CA1 and dentate interneurons did not differ between HI and sham groups. Interneuron counts did not correlate with time to reach the accessible milk. (J) HI piglets had fewer CA1 interneuron dendrites than did shams (*p<0.05). (K, L) T-maze time and the number of CA1 interneuron dendrites showed no correlation. In the second and third columns, sham piglets are represented by open squares, and HI piglets are represented by closed circles.

4. DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that a spatial T-maze can identify cognitive deficits in neonatal piglets after long-term recovery from global HI brain injury and that these deficits are associated with very selective hippocampal pathology. HI piglets failed to learn the T-maze during days 1–4 and on reverse day 1. In contrast, shams successfully learned the T-maze and displayed better recall of visual cues than did HI piglets. At 1-month recovery after HI, piglets had fewer surviving neurons in CA3 hippocampus and fewer parvalbumin-immunoreactive dendrites in CA1 than did shams. Greater CA3 neuron loss correlated with more incorrect T-maze turns, and more parvalbumin-positive CA3 interneuron cell bodies correlated with faster time in the maze. Despite significant neuron loss in putamen, HI piglets did not exhibit motor impairments based on inclined beam walking time or T-maze performance. We conclude that HI causes cognitive deficits related to pathologic hippocampal injury that includes pyramidal neuron loss, parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneuron number, and interneuron dendritic attrition. Cognitive impairments after piglet HI can be identified by the spatial T-maze test.

In nonhuman primates, hippocampal lesions block the ability to retrieve memorized visual cues [27]. Our identified correlation between T-maze performance and CA3 neuron and parvalbumin interneuron counts shows that piglets also have impaired learning and visual cue recall for navigation after HI hippocampal injury. Though the number of parvalbumin interneurons was similar between HI and sham groups, the interneurons showed significant dendritic attrition after HI. Hippocampal parvalbumin interneurons are GABAergic [29]. Possible network abnormalities, such as unregulated and excess excitatory hippocampal input, may have interfered with the animals’ ability to learn the maze [30]. The association between fewer parvalbumin interneurons and slower T-maze navigation in our study is consistent with reports that parvalbumin inhibitory interneurons are essential for cortical network information processing [31]. Although we did not quantify the number of parvalbumin-positive dendrites in CA3 due to the orientation of the processes, it is possible that excess excitatory input could have contributed to the observed CA3 neuronal loss. Interneurons are highly vulnerable in mouse CA3 after HI, but in this setting, it is unclear whether the interneuron loss is secondary to pyramidal neuron destruction from the infarct-like injury [26].

In our piglets, we observed significant interneuron dendritic attrition despite overall integrity of the hippocampus being preserved and no loss of CA1 pyramidal neurons or dentate gyrus neurons. Dendrite attrition is commonly seen in human neurodegenerative diseases [32]. The CA3 pyramidal neuron loss was only moderate. Interneuron dysfunction impairs behavioral performance, and restoring activity in these cells reverses the behavioral deficit [33]. Thus, HI-induced hippocampal neuron and interneuron dendrite loss may contribute to the cognitive impairments of some HIE survivors [1, 2].

The equivalent T-maze performance on reverse day 2 suggests that the HI piglets learned the maze but at a much slower pace than the shams. The piglets had equal opportunity to learn the maze during the 10 trials/day on days 1–4 and reverse day 1. On the second reverse day, both HI and sham piglets had equal proportions of correct turns. Thus, the HI piglets seemed to eventually learn the location of the accessible milk, but they required longer time to retain this information. This finding also indicates that the HI piglets had poor working memory.

We observed significant neuronal loss in putamen at 1 month of recovery from HI. These results are consistent with our prior reports of early putamen injury after piglet HI [11, 28, 34]. Despite this putamen injury, the HI-injured piglets did not display motor impairments based on time to walk up the inclined beam or T-maze performance. Motor ambulatory skills may have been preserved because lesions of the basal ganglia were incomplete in this piglet model. We also identified no association between putamen neuron loss and T-maze performance. This result is not surprising given that the caudate nucleus has a greater role than putamen in the incremental acquisition of stimulus-response learning behavior [35]. Thus, the slowed learning and higher proportion of incorrect turns in HI piglets was likely due to cognitive dysfunction and largely unrelated to motor deficits.

We found that the hippocampal CA1 region of 3-day-old piglets is insensitive to global HI in our model. Our findings corroborate prior evidence that piglet CA3 is more vulnerable than CA1 or dentate gyrus to HI with 10-day recovery [36]. Nevertheless, this contrasts to the exquisite sensitivity of adult human CA1 to cardiac arrest [37]. Studies of 60 min of HI in P7 rats also show less vulnerability of CA1 hippocampus than cortex, striatum, and thalamus [38], and hippocampal injury develops by P13 in rats with HI durations of at least 60 min [39]. Our piglet model utilizes a shorter HI duration and does not produce the infarcts seen in rodent models. It is noteworthy that our results are consistent with postmortem findings in human infants after perinatal asphyxia, as reported by Schiering et al. [40]. In that study, neonatal CA1 hippocampus was far less vulnerable to asphyxia in babies without clinical seizures than in those with clinical seizures. In our study, the HI piglets did not have overt clinical seizures. In addition, the cognitive deficits exhibited suggest that learning and spatial memory deficits develop in piglets when hippocampal lesion severity is less than that required to produce similar cognitive deficits in rats [41]. However, when CA1 injury does occur after four-vessel occlusion in adult rats, CA1 cell loss is not associated with spatial behavior performance. [42]

Though neurobehavioral tests for rodent models of neonatal HI are well established [43], analogous methods are less developed for large-animal, neonatal HI models. Given the risk of intellectual impairment in survivors of HIE, we sought to advance the translational value of piglet HI by identifying a method to assess cognitive dysfunction and the associated neuropathology. Large animals with gyrencephalic brain enable detailed pathologic evaluation in distinct anatomic regions, many of which cannot be fully evaluated in rodents. Moreover, prolonged periods of hypothermia and controlled rewarming can be tested in large animals [3, 7, 9, 10, 23, 44] alongside therapeutic interventions. The spatial T-maze method of detecting piglet cognitive dysfunction has potential for studying the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

Our piglet HI model has several differences from human neonatal HIE that merit discussion. HIE can occur from a variety of insults in utero or at birth that includes hypoxia, asphyxia, infectious agents, and metabolic derangements. We focus our model on hypoxic asphyxic injury at 3 days in term piglets. Piglets are more tolerant of global HI at 3 days than newly born piglets, including better cardiovascular recovery and less gastrointestinal injury. We therefore use 3 day old piglets for survival and cognitive tests. Though swine myelination begins prenatally [45] and continues postnatally [46] like humans [47, 48], piglet brain develops faster than human brain. One week of postnatal piglet brain growth is equivalent to approximately 1 month of postnatal human brain growth [46]. Our piglets did not show apparent motor deficits despite injury in putamen whereas humans may develop complex motor problems, including hypotonia and spasticity, after HIE depending on recovery time. We correct metabolic acidosis after resuscitation from cardiac arrest using bicarbonate in piglets. Though bicarbonate is not clinically recommended during acute resuscitation in HIE, bicarbonate should be considered in prolonged resuscitations once ventilation and cardiovascular circulation are established. [49] Finally, the piglets become hypercarbic when the endotracheal tube is clamped to produce asphyxia. This causes temporary cerebral vasodilation that resolves when ventilation is restored with return to normocarbia. [50]

Some piglets became mildly hypothermic during the surgical preparation. The shams were subsequently warmed to normothermia, but the HI piglets were more difficult to warm due to poorer cardiovascular circulation after whole body HI injury and cardiac arrest. Nonetheless, the HI piglets had significantly more neuron loss in putamen and CA3 hippocampus, greater CA1 interneuron dendrite loss, and more T-maze cognitive deficits than did shams. Thus, this level of mild hypothermia was not neuroprotective after HI.

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. The sample size was small owing to the high costs of housing piglets for 1 month and conducting the T-maze and inclined beam protocols. Thus, outlier effects may influence the interpretation of the data. Additional studies are needed to confirm cognitive deficits after piglet HI. Our repertoire of tests was limited. We did not conduct open field, glass barrier, or food cover tests as has been used in piglet traumatic brain injury studies [18]. We did not assess the presence or absence of sleep pattern abnormalities. Future studies will also require evaluation of both males and females. Lastly, parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons are only one of many subtypes of hippocampal interneurons, and we did not measure synaptic markers.

5. Conclusion

Neonatal piglets with HI brain injury have cognitive deficits that manifest as impaired learning and poor recall of visual cues in a spatial T-maze test. They also exhibit significant CA3 hippocampal neuron loss and CA1 interneuron dendrite attrition. Loss of CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurons and parvalbumin-positive interneurons correlates with poorer T-maze performance. Though putamen injury was significant after HI, putamen neuron loss did not correlate with motor performance. We conclude that the spatial T-maze test can identify piglet cognitive dysfunction related to hippocampal injury, independent of putamen injury. The T-maze test has potential for testing therapeutic interventions in neonatal piglet HI brain injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Dr. Nagat El-Demerdash for her contributions in developing the piglet cognitive and behavior testing methods. We also thank Mr. Michael Reyes for his work with the piglet HI injury and sham procedure protocols and Ms. Claire Levine, MS, ELS for her editing skills.

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grants (grant numbers R01 NS107417, JKL; K08 NS080984, JKL; R01 NS060703, RCK; R21 NS095036, RCK; R01 HL139543, RCK); BrightFocus Foundation (grant number A2015332S, LJM); and the American Heart Association Transformational Project Award (grant number 18TPA34170077, JKL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no disclosures.

References

- [1].Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, Vohr BR, Hintz SR, Yolton K, Gustafson KE, Leach TM, Green C, Bara R, Petrie Huitema CM, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, Das A, Hammond J, Peralta-Carcelen M, Evans PW, Heyne RJ, Wilson-Costello DE, Vaucher YE, Bauer CR, Dusick AM, Adams-Chapman I, Goldstein RF, Guillet R, Papile LA, Higgins RD, Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med, 2012;366:2085–2092 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Burton VJ, Gerner G, Cristofalo E, Chung SE, Jennings JM, Parkinson C, Koehler RC, Chavez-Valdez R, Johnston MV, Northington FJ, Lee JK. A pilot cohort study of cerebral autoregulation and 2-year neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy who received therapeutic hypothermia. BMC Neurol, 2015;15:209-015-0464-4 doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0464-4 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee JK, Wang B, Reyes M, Armstrong JS, Kulikowicz E, Santos PT, Lee JH, Koehler RC, Martin LJ. Hypothermia and rewarming activate a macroglial unfolded protein response independent of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal piglets. Dev Neurosci, 2016;38:277–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ezzati M, Kawano G, Rocha-Ferreira E, Alonso-Alconada D, Hassell JK, Broad KD, Fierens I, Fleiss B, Bainbridge A, Price DL, Kaynezhad P, Anderson B, Hristova M, Tachtsidis I, Golay X, Gressens P, Sanders RD, Robertson NJ. Dexmedetomidine Combined with Therapeutic Hypothermia Is Associated with Cardiovascular Instability and Neurotoxicity in a Piglet Model of Perinatal Asphyxia. Dev Neurosci, 2017;39:156–170 doi: 10.1159/000458438 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hoque N, Liu X, Chakkarapani E, Thoresen M. Minimal systemic hypothermia combined with selective head cooling evaluated in a pig model of hypoxia-ischemia. Pediatr Res, 2015;77:674–680 doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.31 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Koehler RC, Yang ZJ, Lee JK, Martin LJ. Perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in large animal models: Relevance to human neonatal encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2018:271678X18797328 doi: 10.1177/0271678X18797328 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Davidson JO, Wassink G, Draghi V, Dhillon SK, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. Limited benefit of slow rewarming after cerebral hypothermia for global cerebral ischemia in near-term fetal sheep. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2018:271678X18791631 doi: 10.1177/0271678X18791631 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McAdams RM, Fleiss B, Traudt C, Schwendimann L, Snyder JM, Haynes RL, Natarajan N, Gressens P, Juul SE. Long-Term Neuropathological Changes Associated with Cerebral Palsy in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Dev Neurosci, 2017;39:124–140 doi: 10.1159/000470903 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang B, Armstrong JS, Reyes M, Kulikowicz E, Lee JH, Spicer D, Bhalala U, Yang ZJ, Koehler RC, Martin LJ, Lee JK. White matter apoptosis is increased by delayed hypothermia and rewarming in a neonatal piglet model of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Neuroscience, 2016;316:296–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang B, Armstrong JS, Lee JH, Bhalala U, Kulikowicz E, Zhang H, Reyes M, Moy N, Spicer D, Zhu J, Yang ZJ, Koehler RC, Martin LJ, Lee JK. Rewarming from therapeutic hypothermia induces cortical neuron apoptosis in a swine model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2015;35:781–793 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.245 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Martin LJ, Brambrink A, Koehler RC, Traystman RJ. Primary sensory and forebrain motor systems in the newborn brain are preferentially damaged by hypoxia-ischemia. J Comp Neurol, 1997;377:262–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li Y, Shen M, Stockton ME, Zhao X. Hippocampal deficits in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 2018. doi: S1074–7427(18)30235–1 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Holm IE, West MJ. Hippocampus of the domestic pig: a stereological study of subdivisional volumes and neuron numbers. Hippocampus, 1994;4:115–125 doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040112 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Abraham H, Toth Z, Seress L. A novel population of calretinin-positive neurons comprises reelin-positive Cajal-Retzius cells in the hippocampal formation of the adult domestic pig. Hippocampus, 2004;14:385–401 doi: 10.1002/hipo.10180 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thoresen M, Haaland K, Loberg EM, Whitelaw A, Apricena F, Hanko E, Steen PA. A piglet survival model of posthypoxic encephalopathy. Pediatr Res, 1996;40:738–748 doi: 10.1203/00006450-199611000-00014 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee JK, Yang ZJ, Wang B, Larson AC, Jamrogowicz JL, Kulikowicz E, Kibler KK, Mytar JO, Carter EL, Burman HT, Brady KM, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Koehler RC, Shaffner DH. Noninvasive autoregulation monitoring in a Swine model of pediatric cardiac arrest. Anesth Analg, 2012;114:825–836 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824762d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].LeBlanc MH, Huang M, Vig V, Patel D, Smith EE. Glucose affects the severity of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in newborn pigs. Stroke, 1993;24:1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Friess SH, Ichord RN, Owens K, Ralston J, Rizol R, Overall KL, Smith C, Helfaer MA, Margulies SS. Neurobehavioral functional deficits following closed head injury in the neonatal pig. Exp Neurol, 2007;204:234–243 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Friess SH, Ichord RN, Ralston J, Ryall K, Helfaer MA, Smith C, Margulies SS. Repeated traumatic brain injury affects composite cognitive function in piglets. J Neurotrauma, 2009;26:1111–1121 doi: 10.1089/neu.2008-0845 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Elmore MR, Dilger RN, Johnson RW. Place and direction learning in a spatial T-maze task by neonatal piglets. Anim Cogn, 2012;15:667–676 doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0495-9 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maguire EA, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Human spatial navigation: cognitive maps, sexual dimorphism, and neural substrates. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 1999;9:171–177 doi: S0959–4388(99)80023–3 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Larson AC, Jamrogowicz JL, Kulikowicz E, Wang B, Yang ZJ, Shaffner DH, Koehler RC, Lee JK. Cerebrovascular autoregulation after rewarming from hypothermia in a neonatal swine model of asphyxic brain injury. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2013;115:1433–1442 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00238.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Santos PT, O’Brien CE, Chen MW, Hopkins CD, Adams S, Kulikowicz E, Singh R, Koehler RC, Martin LJ, Lee JK. Proteasome biology is compromised in white matter after asphyxic cardiac arrest in neonatal piglets. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].O’Brien CE, Santos PT, Kulikowicz E, Reyes M, Koehler RC, Martin LJ, Lee JK. Hypoxia-ischemia and hypothermia independently and interactively affect neuronal pathology in neonatal piglets with short-term recovery. Dev Neurosci, 2019;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fitz NF, Gibbs RB, Johnson DA. Selective lesion of septal cholinergic neurons in rats impairs acquisition of a delayed matching to position T-maze task by delaying the shift from a response to a place strategy. Brain Res Bull, 2008;77:356–360 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.016 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chavez-Valdez R, Emerson P, Goffigan-Holmes J, Kirkwood A, Martin LJ, Northington FJ. Delayed injury of hippocampal interneurons after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia and therapeutic hypothermia in a murine model. Hippocampus, 2018. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22965 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Froudist-Walsh S, Browning PGF, Croxson PL, Murphy KL, Shamy JL, Veuthey TL, Wilson CRE, Baxter MG. The Rhesus Monkey Hippocampus Critically Contributes to Scene Memory Retrieval, But Not New Learning. J Neurosci, 2018;38:7800–7808 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0832-18.2018 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Martin LJ, Brambrink AM, Price AC, Kaiser A, Agnew DM, Ichord RN, Traystman RJ. Neuronal death in newborn striatum after hypoxia-ischemia is necrosis and evolves with oxidative stress. Neurobiol Dis, 2000;7:169–191 doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Klausberger T, Marton LF, O’Neill J, Huck JH, Dalezios Y, Fuentealba P, Suen WY, Papp E, Kaneko T, Watanabe M, Csicsvari J, Somogyi P. Complementary roles of cholecystokinin- and parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic neurons in hippocampal network oscillations. J Neurosci, 2005;25:9782–9793 doi: 25/42/9782 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lapray D, Lasztoczi B, Lagler M, Viney TJ, Katona L, Valenti O, Hartwich K, Borhegyi Z, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Behavior-dependent specialization of identified hippocampal interneurons. Nat Neurosci, 2012;15:1265–1271 doi: 10.1038/nn.3176 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kann O, Papageorgiou IE, Draguhn A. Highly energized inhibitory interneurons are a central element for information processing in cortical networks. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2014;34:1270–1282 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.104 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Martin LJ. Mitochondrial and Cell Death Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2010;3:839–915 doi: 10.3390/ph3040839 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goel A, Cantu DA, Guilfoyle J, Chaudhari GR, Newadkar A, Todisco B, de Alba D, Kourdougli N, Schmitt LM, Pedapati E, Erickson CA, Portera-Cailliau C. Impaired perceptual learning in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome is mediated by parvalbumin neuron dysfunction and is reversible. Nat Neurosci, 2018;21:1404–1411 doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0231-0 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ni X, Yang ZJ, Carter EL, Martin LJ, Koehler RC. Striatal Neuroprotection from Neonatal Hypoxia-Ischemia in Piglets by Antioxidant Treatment with EUK-134 or Edaravone. Dev Neurosci, 2011;33:299–311 doi: 10.1159/000327243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Packard MG, Knowlton BJ. Learning and memory functions of the Basal Ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci, 2002;25:563–593 doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142937 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhu J, Wang B, Lee JH, Armstrong JS, Kulikowicz E, Bhalala US, Martin LJ, Koehler RC, Yang ZJ. Additive Neuroprotection of a 20-HETE Inhibitor with Delayed Therapeutic Hypothermia after Hypoxia-Ischemia in Neonatal Piglets. Dev Neurosci, 2015;37:376–389 doi: 10.1159/000369007 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Petito CK, Feldmann E, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Delayed hippocampal damage in humans following cardiorespiratory arrest. Neurology, 1987;37:1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schwartz PH, Massarweh WF, Vinters HV, Wasterlain CG. A rat model of severe neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Stroke, 1992;23:539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Towfighi J, Mauger D, Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ. Influence of age on the cerebral lesions in an immature rat model of cerebral hypoxia-ischemia: a light microscopic study. Brain Res Dev Brain Res, 1997;100:149–160 doi: S0165380697000369 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schiering IA, de Haan TR, Niermeijer JM, Koelman JH, Majoie CB, Reneman L, Aronica E. Correlation between clinical and histologic findings in the human neonatal hippocampus after perinatal asphyxia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2014;73:324–334 doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000056 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Broadbent NJ, Squire LR, Clark RE. Spatial memory, recognition memory, and the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004;101:14515–14520 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406344101 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nunn JA, LePeillet E, Netto CA, Hodges H, Gray JA, Meldrum BS. Global ischaemia: hippocampal pathology and spatial deficits in the water maze. Behav Brain Res, 1994;62:41–54 doi: 0166–4328(94)90036–1 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ten VS, Bradley-Moore M, Gingrich JA, Stark RI, Pinsky DJ. Brain injury and neurofunctional deficit in neonatal mice with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Behav Brain Res, 2003;145:209–219 doi: S0166432803001463 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Davidson JO, Yuill CA, Zhang FG, Wassink G, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. Extending the duration of hypothermia does not further improve white matter protection after ischemia in term-equivalent fetal sheep. Sci Rep, 2016;6:25178 doi: 10.1038/srep25178 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sheng HZ, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Carnegie PR, Bernard CC. Developmental study of myelin basic protein variants in various regions of pig nervous system. J Neurochem, 1989;52:736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Conrad MS, Johnson RW. The domestic piglet: an important model for investigating the neurodevelopmental consequences of early life insults. Annu Rev Anim Biosci, 2015;3:245–264 doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-111049 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dubois J, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Kulikova S, Poupon C, Huppi PS, Hertz-Pannier L. The early development of brain white matter: a review of imaging studies in fetuses, newborns and infants. Neuroscience, 2014;276:48–71 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.044 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fields RD. White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci, 2008;31:361–370 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.04.001 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martinello K, Hart AR, Yap S, Mitra S, Robertson NJ. Management and investigation of neonatal encephalopathy: 2017 update. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2017;102:F346–F358 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309639 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee JK, Brady KM, Mytar JO, Kibler KK, Carter EL, Hirsch KG, Hogue CW, Easley RB, Jordan LC, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Shaffner DH, Koehler RC. Cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular autoregulation in a swine model of pediatric cardiac arrest and hypothermia. Crit Care Med, 2011;39:2337–2345 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318223b910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.