Abstract

Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels are intimately linked with health and disease. The gene encoding the CRAC channel, ORAI1, was discovered in part by genetic analysis of patients with abolished CRAC channel function. And patients with autosomal recessive loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in ORAI1 and its activator stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) that abolish CRAC channel function and store- operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) define essential functions of CRAC channels in health and disease. Conversely, gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 are associated with tubular aggregate myopathy (TAM) and Stormorken syndrome due to constitutive CRAC channel activation. In addition, genetically engineered animal models of ORAI and STIM function have provided important insights into the physiological and pathophysiological roles of CRAC channels in cell types and organs beyond those affected in human patients. The picture emerging from this body of work shows CRAC channels as important regulators of cell function in many tissues, and as potential drug targets for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

CRAC channels mediate Ca2+ influx in many cell types. They are traditionally viewed as being especially important for the function of electrically non-excitable cells including, but not limited to, immune cells. Ca2+ influx mediated by CRAC channels is called store-operated Ca2+ entry, or SOCE, because it is regulated by the filling state of intracellular (mainly ER) Ca2+ stores [1]. The engagement of cell surface receptors including G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and immunoreceptors such as T cell, B cell and Fc receptors results in the production of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) that binds to the IP3 receptor (IP3R) located in the membrane of the ER, which is a Ca2+ permeable ion channel and mediates the release of Ca2+ from the ER. This release has two consequences: an increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration and a decrease in the Ca2+ concentration of the ER. The latter results in the dissociation of Ca2+ in the ER from STIM proteins, conformational changes of STIM1 and STIM2 and their translocation to ER-plasma membrane junctions. In these junctions, STIM proteins cluster and recruit ORAI proteins to form microdomains of localized Ca2+ influx. ORAI1, and its closely related homologues ORAI2 and ORAI3, is a tetraspanning plasma membrane proteins that assembles in hexamers and forms the highly Ca2+ selective CRAC channel. The ORAI1, 2 and 3 were named after the three horae (hours), Eunomia, Dike, Eirene, who – in Greek mythology – were the guardians of the gates of Olympus (see the cover of this special issue of Cell Calcium), similar to CRAC channels controlling the flux of Ca2+ across the cell membrane. The biophysical properties of CRAC channels, the molecular structure of STIM and ORAI proteins and the mechanisms of SOCE regulation are the subject of reviews in a companion Special Issue of Cell Calcium edited by J. Soboloff and C. Romanin [2].

This issue of Cell Calcium focuses on CRAC channels and disease. It aims to provide a comprehensive picture of our current knowledge of the physiological and pathophysiological roles of CRAC channels gleaned from the phenotypes of humans patients with inherited defects in CRAC channel function and mice genetically engineered to lack Orai or Stim genes. The intimate relationship between CRAC channels and disease first became clear from studies in the 1990s reporting defects in CRAC channel function and SOCE in patients with severe forms of combined immunodeficiency resulting in chronic and often fatal infections with viral and bacterial pathogens [3–6]. At that time, the biophysical properties of CRAC channels had been established [7, 8], but its molecular nature (and thus the genes mutated in the immunodeficient patients) would remain elusive for another decade despite significant efforts to identify the channel. The breakthroughs came with the discovery, first, of STIM1 in two independent RNAi screens [9, 10] and, a year later, of ORAI1 by a combination of RNAi screens and genetic linkage analysis in patients with inherited defects in CRAC channel function [11–13]. These discoveries have spurred hundreds of studies of the molecular regulation of CRAC channel function. They also enabled the generation of animal models to investigate the physiological and pathophysiological roles of CRAC channels in many cell types and tissues. As the reviews assembled in this issue of Cell Calcium impressively demonstrate, we have come a long way in understanding the central role of Ca2+ influx through CRAC channels in many tissues and its involvement in many diseases since the discovery of CRAC channels and the genes encoding them.

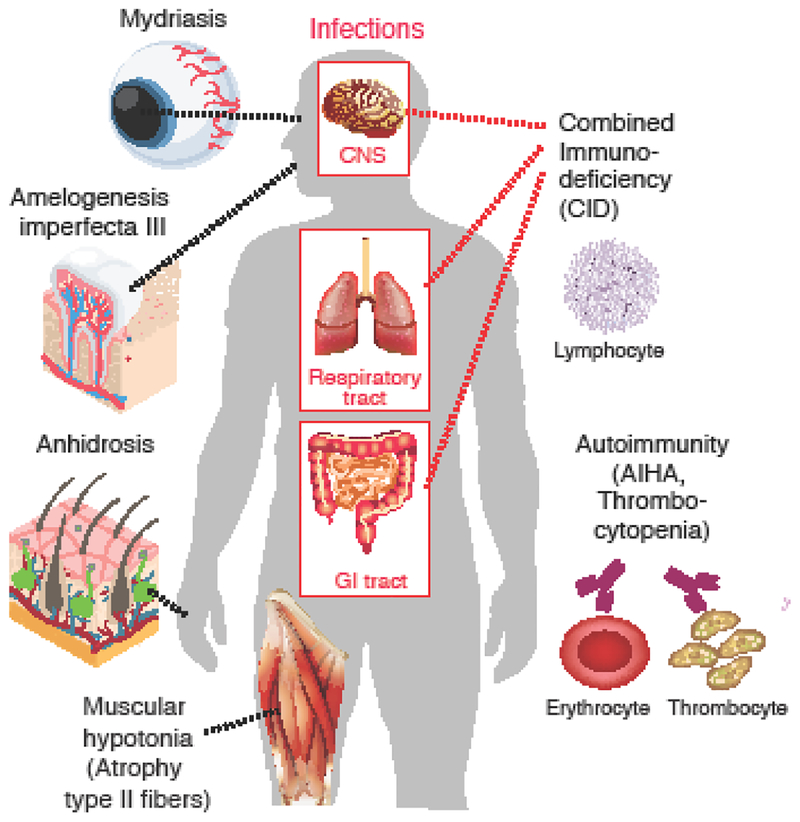

A cornerstone of our understanding of the physiological function of CRAC channels are patients with inherited null or loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in ORAI1 and its activator stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1). These patients lack CRAC channel function and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) resulting in a disease called CRAC channelopathy [14]. This syndrome is characterized by combined immunodeficiency (CID) with recurrent and chronic infections, autoimmunity including autoantibody- mediated hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, muscular hypotonia with muscle fiber atrophy, and ectodermal dysplasia defined by anhidrosis due to abolished sweat gland function and defects in dental enamel development. It is noteworthy that the phenotypes of patients with LOF mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 are almost identical, suggesting a privileged partnership between these two proteins in the same SOCE pathway. Although a rare disease, CRAC channelopathy has provided important insights into the essential functions of CRAC channels in human health and disease.

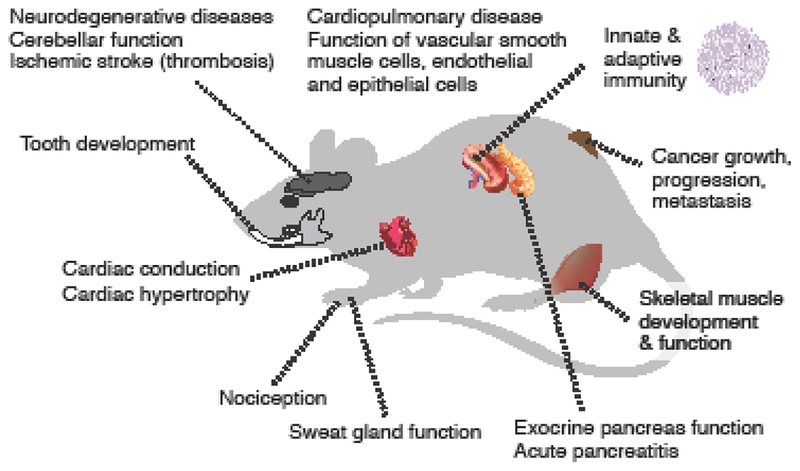

The first group of reviews in this special issue of Cell Calcium examines the physiological and pathophysiological roles of CRAC channels related to cells and organs affected in patients with inherited defects in CRAC channel function (Figure 1, 2) [15–19]. Patients with LOF mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 genes suffer from CRAC channelopathy. This syndrome has a well-defined but relatively limited spectrum of symptoms, suggesting a relatively narrow involvement of CRAC channels in the function of immune cells, skeletal muscle, sweat glands and enamel-forming ameloblasts. This contrasts, however, with the ubiquitous expression of ORAI and STIM genes in many other tissues and the presence of SOCE in many cell types in humans, mice and other species. Furthermore, studies of mice with genetic deletion of Orai and Stim genes have revealed additional roles of CRAC channels in health and disease that go beyond the phenotype of patients with CRAC channelopathy and that are the topic of a second group of reviews in this special issue [20–25]. Arguably the most dramatic difference between CRAC channel deficient patients and mice is that Orai1-/- or Stim1-/- mice are not viable, which is most apparent on the inbred C57BL/6 background. Studies of outbred Orai1-/- or Stim1-/- mice, in which the perinatal lethality is partially attenuated, and mice with conditional knockout of Orai1, Stim1 and Stim2 in specific tissues furthermore demonstrate important physiological roles of CRAC channels in cardiac conduction, platelet function, nociception as well as pathological conditions including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiopulmonary disorders and ischemic stroke that are not observed in ORAI1 or STIM1 deficient patients (Figure 3).

Figure 1. CRAC channelopathy in human patients.

Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 genes result in combined immunodeficiency with chronic, often lethal infections and a variety of non-immunological symptoms. For details see [14, 30]. AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

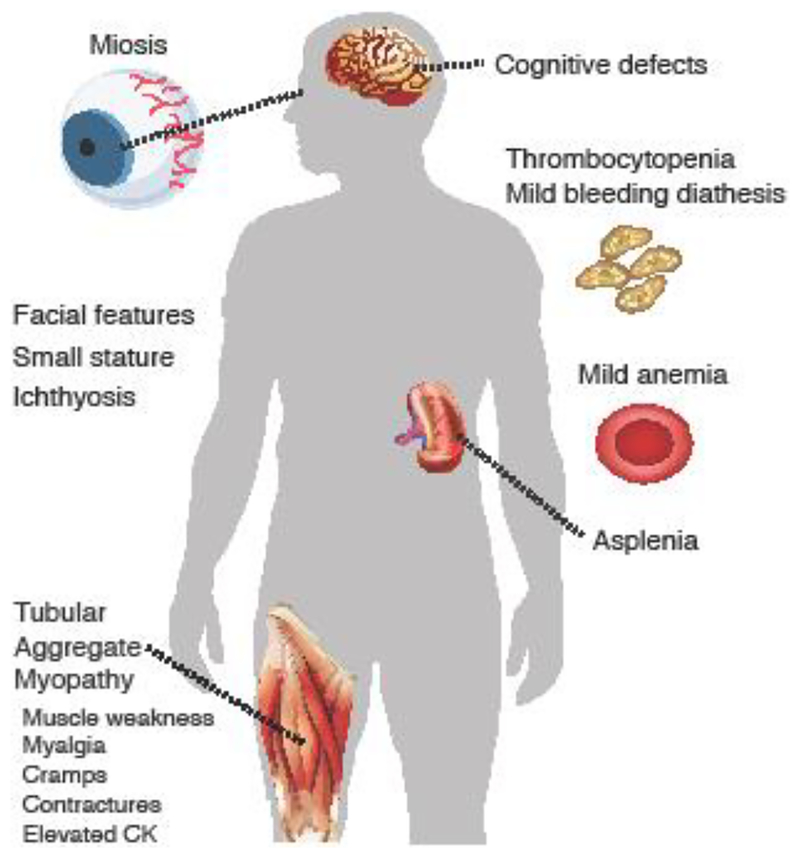

Figure 2. Clinical phenotype of patients with Stormorken syndrome and tubular aggregate myopathy.

Gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1. For details see [15]. CK, creatinine kinase.

Figure 3. Animal models of CRAC channel function in health and disease in mice.

Organs in which CRAC channels play a role in physiological function or disease pathology as examined by reviews in this special issue of Cell Calcium [17–25].

A legitimate question arising from the additional phenotypes of Orai1 and Stim1-deficient mice compared to human patients is whether the physiological roles of SOCE in mice and humans are different. Indeed, lack of ORAI1 in human T cells, for instance, abolishes SOCE and CRAC channel function, whereas Orai1 deletion in murine T cells only partially impairs either, which is due to additional contributions to SOCE by ORAI2 in mouse T cells [26]. Such redundancy of ORAI homologues in mice would suggest that Orai1 deficient animals have a more limited disease phenotype than ORAI1 deficient human patients, which is however not the case. There are several possible explanations why patients with CRAC channelopathy do not reveal the full extent of CRAC channel involvement in the physiology and pathophysiology of cells and tissues. First, the expression patterns of ORAI and STIM genes in human and mouse tissues may be different and some functions of ORAI1 and STIM1, the main homologues studied so far, may be non-redundant in mice. Second, germline LOF mutations in human ORAI1 and STIM1 genes abolish CRAC channel function throughout all pre-and postnatal stages of development and it is not uncommon that cells find ways to compensate for the loss of one signaling pathway by upregulating another. The CRAC channelopathy phenotype in human patients may thus represent only those cells and organs that are not capable, for reasons to be elucidated, of using alternative Ca2+ signaling pathways. Such alternative pathways may be available in human but not mouse tissues. Third, many studies of CRAC channels use conditional knockout mice in which deletion of Orai and Stim genes occurs in specific cell types and at specific stages of cell development that are determined by when and where promoters driving Cre recombinase expression are activated. For instance, in one study expression of Elastase-Cre was induced by tamoxifen injection resulting in acute deletion of Orai1 gene specifically in mature pancreatic acinar cells. This study showed a critical role of ORAI1 in the secretion of antimicrobial peptides by pancreatic acinar cells that shape intestinal innate immunity and are essential for the survival of mice [27]. This role of ORAI1, which is not observed in human patients lacking ORAI1 or STIM1 function, is likely due to the acute deletion of CRAC channel function, preventing any potential compensatory upregulation of alternative Ca2+ signaling pathways. Finally, a similar argument applies to studies using CRAC channel inhibitors that acutely suppress SOCE precluding other Ca2+ signaling pathways from compensating for defective cell functions. Acute genetic deletion of CRAC channel in mice is an important tool to reveal new and unexpected roles for ORAI and STIM proteins that are not readily apparent in CRAC channel deficient patients but critical to assess the (side) effects of CRAC channel inhibitory drugs. With these considerations in mind, let us approach the reviews in this special issue of Cell Calcium.

A first group of reviews examines the role of SOCE in cells and tissues affected in patients with CRAC channelopathy (Figure 1). Clemens & Lowell review evidence for the role of CRAC channels in innate immune cells in health and disease [16]. The immunodeficiency of patients lacking functional CRAC channels was shown to be dominated by defects in adaptive immunity including impaired T cell function, production of antigen specific antibodies and NK cell cytotoxicity. Besides lymphocytes, CRAC channels also are a major Ca2+ entry pathway in innate immune cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils following stimulation of antigen and G protein-coupled receptors. The authors examine evidence based on the deletion of STIM1, STIM2 or ORAI1 in innate cells in mice and humans which indicates that all three proteins contribute to specific innate immune cell functions, for example activation of the neutrophil oxidase and mast cell activation. A common feature of virtually all patients with CRAC channelopathy is ectodermal dysplasia characterized by defects in dental enamel development (hypocalcified amelogenesis imperfecta) and anhidrosis. Eckstein & Lacruz review the mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 causing amelogenesis in human patients, new insights gained from the analysis of CRAC channel-deficient mice and the mechanisms by which SOCE contributes to dental enamel cell development and function [17]. The authors also provide a brief overview of the role of CRAC channels in other mineralizing tissues such as dentine and bone. Ectodermal dysplasia in patients with CRAC channelopathy is further characterized by anhidrosis. The inability to sweat is due to impaired eccrine sweat gland function because of the SOCE-dependent activation of Ca2+ activated Cl− channel TMEM16A [28]. Muallem and colleagues review the current knowledge how CRAC channels regulate the function of secretory epithelial cells and their involvement in disease [18]. They discuss the properties of Ca2+ signals evoked by CRAC and other Ca2+ channels such as TRPC channels as well as phospholipids at ER-plasma membrane junctions with regard to secretory cells function and disease caused by uncontrolled Ca2+ influx.

Another common symptom of CRAC channelopathy syndrome is congenital muscular hypotonia with an atrophy of type II muscle fibers. Dirksen and colleagues examine the role of CRAC channels in skeletal muscle physiology and disease [19]. Their review focuses on the molecular mechanisms and physiological role of SOCE in skeletal muscle, as well as how alterations in STIM1/ORAI1-mediated SOCE contribute to muscle disease. The authors point out that SOCE plays an important role in muscle development as well as prevention of muscle fatigue. Dysfunctional SOCE contributes to the pathogenesis of diseases like muscular dystrophy, malignant hyperthermia, and sarcopenia. Whereas LOF mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 result in congenital muscular hypotonia, gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in the same genes resulting in constitutive Ca2+ entry are the underlying cause of another form of muscle disease called tubular aggregate myopathy (TAM). The effects of GOF mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 are examined in more detail by Böhm & Laporte, who review the phenotype of patients with TAM and a related disease called Stormorken syndrome [15]. Both disorders are part of a clinical continuum that is characterized by muscle weakness and additional features of variable severity including miosis, thrombocytopenia, hyposplenism, ichthyosis, dyslexia, and short stature (Figure 2). The authors also discuss mutations in the reticular Ca2+ buffer calsequestrin (CASQ1) as another genetic cause of TAM and Stormorken syndrome. Myopathy is (besides thrombocytopenia) the only shared feature of patients with LOF and GOF mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1, suggesting that tight regulation of CRAC channel function and SOCE are critical for optimal skeletal muscle development and function.

A second group of reviews in this special issue of Cell Calcium examines the role of SOCE in cells and tissues that are not affected in patients with CRAC channelopathy, but whose function is clearly dependent on CRAC channels based on evidence from mice and other model organisms with deletion of CRAC channel genes (Figure 3). Braun and colleagues review the role of SOCE in thrombosis and thrombo-inflammation [22]. They provide an overview of the physiological and pathophysiological function of SOCE in hematopoietic cells including platelets and immune cells that are involved in thrombosis and inflammation. They furthermore discuss the potential of CRAC channel inhibition as a therapeutic option to prevent or treat arterial thrombosis as well as thrombo-inflammatory diseases such as ischemic stroke. Trebak and colleagues examine the involvement of ORAI channels in cardiorespiratory diseases including systemic arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [21]. The authors point out that a common mechanism underlying the pathophysiology of all these diseases is cellular remodeling, which is regulated by the function of ion channels, including ORAI, in smooth muscle cells, endothelial and epithelial cells as well as platelets and immune cells. Over the last 10 years, many labs have investigated the role of SOCE in cancer growth, proliferation and metastasis. Chalmers & Monteith review the current literature on Ca2+ signals in cancer and how they control the properties of cancer cells including their proliferation, invasion and resistance to cell death [20]. Whereas much earlier work on Ca2+ signaling in cancer had focused on transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, the discovery of ORAI and STIM genes has attracted considerable interest in SOCE as a pathway deregulated in tumor cells. The authors discuss how changes in the expression of ORAI homologues in different cancers and cancer subtypes may affect tumor progression, metastasis and the development of drug resistance.

An intriguing development in the CRAC channel field are reports about roles of ORAI and STIM proteins in electrically excitable cells. The cell types and tissues discussed above, including cancer cells but with the exception of skeletal muscle, have in common that they are not electrically excitable, i.e. they do not propagate action potentials. Historically, the study of CRAC channels and SOCE has for the most part focused on non-excitable cells. This includes salivary gland cells and immune cells (T cells, mast cells) in which SOCE and CRAC channel currents, respectively, were first described. Electrically excitable cells such as neurons and cardiomyocytes express a variety of Ca2+ channels including voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and ionotropic glutamate receptors that mediate Ca2+ influx in response to membrane depolarization and neurotransmitter binding, respectively. Why then would excitable cells need CRAC channels to flux Ca2+? The seeming redundancy of CRAC channels in excitable cells has delayed research compared to non-excitable cells and consequently our knowledge of the function of CRAC channels in neurons and other excitable cells is still nascent. Recent evidence however suggests that SOCE may play critical roles in excitable cells, too. Rosenberg and colleagues examine the involvement of STIM1 and SOCE in the heart and discuss the evidence for their role in cardiomyocyte function and cardiac conduction [24]. They highlight recent studies revealing a role for STIM1 in cardiac growth in response to developmental and pathologic cues. In addition, they discuss SOCE in pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial node and its function in generating the cardiac rhythm. Wegierski & Kuznicki review the function of SOCE in neurons and discuss how CRAC channels control neuronal Ca2+ signaling in health and disease [25]. The authors summarize the available data on the molecular components of SOCE in neurons and their relevance to neuronal signaling. They discuss the evidence for an involvement of SOCE in neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease as well as traumatic brain injury. In addition to emerging evidence for SOCE in neurons of the central nervous system (CNS), Hu and colleagues review the role of CRAC channels in the peripheral nervous system and in pain [23]. The authors summarize the current knowledge about the expression and function of the CRAC channels in neurons and glial cells of the dorsal root ganglion, spinal cord and certain regions of the brain. They discuss recent findings indicating that the CRAC channel ORAI1 and SOCE have important functions in nociception and chronic pain.

Collectively, the reviews cited above demonstrate that our understanding of the physiological and pathophysiological role of CRAC channels, facilitated by the study of human patients and genetically engineered mice lacking ORAI and STIM function, has dramatically improved in the last 5–10 years. In parallel, our knowledge of the molecular regulation of CRAC channels has rapidly expanded as summarized in a companion special issue of Cell Calcium [2]. An obvious question resulting from these advances is how we can utilize these insights into the molecular regulation of CRAC channels and their role in disease and translate them into developing new drugs for the treatment of a variety of disorders including cancer, cardiorespiratory diseases, inflammation and autoimmunity? Indeed, the discovery of ORAI1 and STIM1 a decade and a half ago sparked an immediate interest in CRAC channels as drug targets and has led to the development of CRAC channel inhibitors by several companies. These efforts were motivated, at least in part, by the effects of ORAI1 and STIM1 LOF mutations in patients and the deletion of these genes in mice on immune function, suggesting that CRAC channel inhibitors might be useful therapeutics for immune-related disorders. In this issue, K. Stauderman provides a comprehensive review of the current status of CRAC channels as targets of drug discovery and development and the utility of CRAC channel blockers for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [29]. His review examines the challenges associated with CRAC channel inhibitors including target selection and justification, pharmacological, safety and toxicological profiles of compounds, and reports on the entry of CRAC channel inhibitors into clinical trials. With the currently ongoing testing of CRAC channel inhibitors in phase 2 clinical trials for acute pancreatitis we have come almost full circle from the discovery of patients with rare inherited mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1 and their severe immunodeficiency to developing CRAC channel inhibitors that may benefit patients with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. If indeed CRAC channel blockers should proof to be useful for the treatment of immune-related or other disorders, then the study of patients (and mice) with CRAC channel deficiency will have paid huge dividends.

Cover picture:

Dionysos leading the Horai. Marble, Roman copy (1st century CE) after a Hellenistic neo-Attic work. Artist unknown. Musée du Louvre.

NOTE: This is a public domain image. Details at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dionysos_Horai_Louvre_MR720.jpg

Acknowledgements.

This work was funded by NIH grants AI097302, AI130143 and AI137004 and an Irma T. Hirschl career scientist award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests. S.F. is a scientific cofounder of Calcimedica.

References

- [1].Putney JW Jr., A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry, Cell Calcium, 7 (1986) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Soboloff J, Romanin C, STIM1 Structure-function and Downstream Signaling Pathways, Cell Calcium, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Feske S, Giltnane J, Dolmetsch R, Staudt LM, Rao A, Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes, Nat Immunol, 2 (2001) 316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Feske S, Muller JM, Graf D, Kroczek RA, Drager R, Niemeyer C, Baeuerle PA, Peter HH, Schlesier M, Severe combined immunodeficiency due to defective binding of the nuclear factor of activated T cells in T lymphocytes of two male siblings, Eur J Immunol, 26 (1996) 2119–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Le Deist F, Hivroz C, Partiseti M, Thomas C, Buc HA, Oleastro M, Belohradsky B, Choquet D, Fischer A, A primary T-cell immunodeficiency associated with defective transmembrane calcium influx, Blood, 85 (1995) 1053–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Partiseti M, Le Deist F, Hivroz C, Fischer A, Korn H, Choquet D, The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency, J Biol Chem, 269 (1994) 32327–32335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hoth M, Penner R, Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells, Nature, 355 (1992) 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zweifach A, Lewis RS, Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 90 (1993) 6295–6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE Jr., Meyer T, STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx, Curr Biol, 15 (2005) 1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA, STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function, J Cell Biol, 169 (2005) 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A, A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function, Nature, 441 (2006) 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP, CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry, Science, 312 (2006) 1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD, Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release- activated Ca(2+) channel activity, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103 (2006) 9357–9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vaeth M, Feske S, Ion channelopathies of the immune system, Curr Opin Immunol, 52 (2018) 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bohm J, Laporte J, Gain-of-function mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 causing tubular aggregate myopathy and Stormorken syndrome, Cell Calcium, 76 (2018) 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clemens RA, Lowell CA, CRAC channel regulation of innate immune cells in health and disease, Cell Calcium, 78 (2019) 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Eckstein M, Lacruz RS, CRAC channels in dental enamel cells, Cell Calcium, 75 (2018) 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu H, Kabrah A, Ahuja M, Muallem S, CRAC channels in secretory epithelial cell function and disease, Cell Calcium, 78 (2019) 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Michelucci A, Garcia-Castaneda M, Boncompagni S, Dirksen RT, Role of STIM1/ORAI1- mediated store-operated Ca(2+) entry in skeletal muscle physiology and disease, Cell Calcium, 76 (2018) 101–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chalmers SB, Monteith GR, ORAI channels and cancer, Cell Calcium, 74 (2018) 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Johnson M, Trebak M, ORAI channels in cellular remodeling of cardiorespiratory disease, Cell Calcium, 79 (2019) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mammadova-Bach E, Nagy M, Heemskerk JWM, Nieswandt B, Braun A, Store-operated calcium entry in thrombosis and thrombo-inflammation, Cell Calcium, 77 (2019) 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mei Y, Barrett JE, Hu H, Calcium release-activated calcium channels and pain, Cell Calcium, 74 (2018) 180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rosenberg P, Katz D, Bryson V, SOCE and STIM1 signaling in the heart: Timing and location matter, Cell Calcium, 77 (2019) 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wegierski T, Kuznicki J, Neuronal calcium signaling via store-operated channels in health and disease, Cell Calcium, 74 (2018) 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vaeth M, Yang J, Yamashita M, Zee I, Eckstein M, Knosp C, Kaufmann U, Karoly Jani P, Lacruz RS, Flockerzi V, Kacskovics I, Prakriya M, Feske S, ORAI2 modulates store-operated calcium entry and T cell-mediated immunity, Nat Commun, 8 (2017) 14714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ahuja M, Schwartz DM, Tandon M, Son A, Zeng M, Swaim W, Eckhaus M, Hoffman V, Cui Y, Xiao B, Worley PF, Muallem S, Orai1-Mediated Antimicrobial Secretion from Pancreatic Acini Shapes the Gut Microbiome and Regulates Gut Innate Immunity, Cell Metab, 25 (2017) 635–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Concepcion AR, Vaeth M, Wagner LE 2nd, Eckstein M, Hecht L, Yang J, Crottes D, Seidl M, Shin HP, Weidinger C, Cameron S, Turvey SE, Issekutz T, Meyts I, Lacruz RS, Cuk M, Yule DI, Feske S, Store-operated Ca2+ entry regulates Ca2+-activated chloride channels and eccrine sweat gland function, J Clin Invest, 126 (2016) 4303–4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stauderman KA, CRAC channels as targets for drug discovery and development, Cell Calcium, 74 (2018) 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lacruz RS, Feske S, Diseases caused by mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1, Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1356 (2015) 45–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]