Abstract

The CLL-IPI is a risk-weighted prognostic model for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), but has not been evaluated in patients with relapsed CLL or on novel therapies. We evaluated the CLL-IPI in 897 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL in 3 randomized trials testing idelalisib (PI3Kδ inhibitor). The CLL-IPI identified patients as low (2.2%), intermediate (12.8%), high (48.7%), and very high (36.2%) risk, and was prognostic for survival (log-rank p<0.0001; C-statistic 0.706). Of CLL-IPI factors, age >65, β2-microglobulin >3.5mg/L, unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene, and deletion 17p/TP53 mutation were independently prognostic, but Rai I-IV or Binet B/C was not. The CLL-IPI is prognostic for survival in relapsed CLL and with idelalisib therapy. However, low/intermediate risk is uncommon, and regression parameters of individual factors in this risk-weighted model appear different in relapsed CLL. Reassessment of the weighting of the individual variables might optimize the model in this setting.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL-IPI, idelalisib, lymphoma, leukemia, prognostication

Introduction

The Rai classification and Binet staging system incorporate clinical and laboratory features and have been the principal clinical prognostic systems in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) for 40 years,1,2 but in the interim we have developed a deeper understanding of the molecular and genetic landscape in CLL and of their implications for prognosis.

The mutational status of the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) genes informs prognosis, with unmutated IGHV or preferential usage of VH3–21 associated with genetic instability, development of unfavorable genetic lesions, and a more aggressive disease course.3–6 Abnormalities of the tumor suppressor gene p53 resulting from deletion 17p (del17p) and/or TP53 mutation (TP53M) are associated with poor outcomes and refractoriness to chemoimmunotherapy,7–12 and are used to guide choice of therapy. Mutations or deletions of NOTCH1,8,12–14 SF3B1,8,12,14 ATM,7,14 and BIRC312 may also be associated with more aggressive disease. CD383,11,15 and ZAP70 expression11,16–19 are correlated with IGHV mutational status, and their prognostic value independent of IGHV mutational status is uncertain.

There is a need to reliably identify patients expected to have poor survival outcomes despite the availability of targeted therapies, and thus to enable investigators to address unmet needs by designing prospective trials targeting high risk patients. Investigators have developed several prognostic models incorporating clinical and biological risk factors.20–24 The International Prognostic Index for patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL-IPI) is a risk-weighted scoring system consisting of 5 adverse prognostic factors (Table 1), including age >65 (1 point), Rai I-IV or Binet B/C (1 point), β2-microglobulin (B2M) >3.5mg/L (2 points), IGHV unmutated (2 points), and del17p and/or TP53M (4 points), which separates patients into 4 CLL-IPI risk groups: low (score 0–1), intermediate (score 2–3), high (score 4–6), and very high (score 7–10).24 The CLL-IPI scoring system is prognostic for overall survival (OS) among patients with previously untreated CLL receiving chemoimmunotherapy, but has not been evaluated previously in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL or in the context of targeted therapies.

Table 1. CLL-IPI Scoring System.

Patients are assigned points for each adverse CLL-IPI variable: age >65 (1 point), Rai I-IV or Binet B/C (1 point), B2M >3.5mg/L (2 points), IGHV unmutated (2 points), and del17p and/or TP53M (4 points). IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region; B2M, beta-2 microglobulin.

| CLL-IPI Variable | Adverse Factor | Points |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 (17p) | Deleted and/or mutated | 4 |

| IGHV mutation status | Unmutated | 2 |

| B2M, mg/L | >3.5 | 2 |

| Clinical stage | Binet B/C or Rai I-IV | 1 |

| Age, years | >65 | 1 |

| Prognostic score | 0–10 |

It is unknown whether the CLL-IPI risk factors are independently prognostic with comparable hazard ratios when applied to patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. Moreover, novel therapies targeting BTK (ibrutinib) and PI3Kδ (idelalisib) as well as BH3-mimetic BCL2 inhibitors (venetoclax) are active in poor risk CLL and are widely administered to patients with relapsed/refractory disease.25–28 Given the activity of idelalisib in patients with high risk CLL, including those with unmutated IGHV or del17p/TP53M, the most heavily weighted adverse risk factors contributing to the CLL-IPI, we hypothesized that treatment with idelalisib might diminish the prognostic utility of the CLL-IPI scoring system because the outcomes of patients with high and very high risk CLL-IPI scores may improve.

We therefore evaluated the CLL-IPI scoring system in a pooled dataset of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL who received protocol-based therapy in idelalisib randomized phase 3 trials, and sought to validate the CLL-IPI risk score in patients treated with idelalisib-based therapy.

Methods

Study population

We contacted Gilead Sciences on November 13, 2015 to request access to patient data from 3 multicenter, randomized phase 3 trials: idelalisib plus rituximab and bendamustine vs placebo plus rituximab and bendamustine (Study 115; GS-US-312–0116);29 idelalisib plus rituximab vs placebo plus rituximab (Study 116; GS-US-312–0116);30 and idelalisib plus ofatumumab vs ofatumumab (Study 119; GS-US-312–0119).31 Gilead Sciences agreed to include these data in the analysis. There was no additional specific rationale to include idelalisib rather than an alternative targeted agent for this analysis.

All patients had a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, were previously treated, and had an indication for treatment. Studies 115 and 116 were double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase 3 trials. Study 119 was an open-label randomized phase 3 trial. The clinical trials were approved by the Institutional Review Boards and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01569295; NCT01539512; NCT01659021). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Data analysis

Patients randomized and treated on Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119, were included in the analysis (n=897). Patients randomized to receive idelalisib plus rituximab and bendamustine (Study 115), idelalisib plus rituximab (Study 116), or idelalisib plus ofatumumab (Study 119), were included in the idelalisib subgroup (n=491). Patients randomized to receive the placebo plus rituximab and bendamustine (Study 115), placebo plus rituximab (Study 116), or ofatumumab (Study 119), were included in the comparator subgroup (n=406).

We calculated the CLL-IPI risk score as described in Table 1. Patients were assigned points for each adverse CLL-IPI variable: age >65 (1 point), Rai I-IV or Binet B/C (1 point), B2M >3.5mg/L (2 points), IGHV unmutated (2 points), and del17p and/or TP53M (4 points). Patients were allocated to 1 of 4 CLL-IPI risk groups defined based on the calculated CLL-IPI risk score: low (score 0–1), intermediate (score 2–3), high (score 4–6), and very high (score 7–10).

The primary endpoint of the analysis was overall survival (OS). OS was calculated from date of randomization to date of death, and patients who remained alive on study or in long term follow-up were censored at date last known alive. We estimated the median OS using the Kaplan-Meier method for the 4 CLL-IPI risk groups, and used the log-rank test to compare survival distributions across CLL-IPI risk groups. We assessed the discriminatory value of the CLL-IPI scoring system using C-statistics, wherein a C-statistic value of 1.0 suggests perfect discrimination and a C-statistic value of 0.5 suggests no discrimination. We performed a multivariate analysis of CLL-IPI risk factors for OS (Cox proportional hazards model). We performed subgroup analyses for both the idelalisib subgroup and comparator subgroup to determine the impact of idelalisib treatment on the CLL-IPI scoring system.

Patients with complete baseline data to calculate the CLL-IPI risk score were included in the complete case analysis (n=864). To confirm that missing data did not affect the analysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis wherein we used a multiple imputation model to impute missing covariates. Since the results of the complete case analysis and multiple imputation analysis were similar (Supplementary Table 1), the complete case analysis is presented in the manuscript.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows version 9.2. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

The full dataset included 897 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL who received idelalisib plus rituximab and bendamustine vs placebo plus rituximab and bendamustine (n=416), idelalisib plus rituximab vs placebo plus rituximab (n=210), or idelalisib plus ofatumumab vs ofatumumab (n=171). Of 897 patients, 864 (96.3%) had complete baseline data available to calculate the CLL-IPI risk score and were included in the complete case analysis dataset.

Patients and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The median age was 66 (range, 32–92 years), the median number prior therapies was 3 (range, 1–13), 53% were >65 years of age, there was a 2.6:1 male predominance, 17.3% had Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≤70%, median CIRS score was 5 (range, 0–18), 96.8% were Rai stage I-IV (95.2%) or Binet stage B/C (87.0%), 44.4% had elevated LDH, 78.1% had B2M >3.5mg/L, 81.9% had unmutated IGHV, and 37.3% had CLL with del17p (22.4%) and/or TP53M (33.2%).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics.

Baseline characteristics are shown for all patients on Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119, and by whether patients were randomized to the idelalisib treatment arms or to the comparator treatment arms. KPS, Karnofsky performance status; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region; TP53M, TP53 mutation.

| Characteristic | Relapsed/Refractory CLL | Idelalisib Subgroup |

Comparator Subgroup | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | n=897 | n=491 | n=406 | |

| Median age (range) | 66 (32–92) | 66 (38–90) | 66 (32–92) | 0.75 |

| Age >65 (%) | 53% | 51.7%% | 54.40% | 0.42 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Female | 28.0% | 26.7% | 29.6% | 0.37 |

| Male | 72.0% | 73.3% | 70.4% | |

| KPS ≤70 (%) | 17.3% | 18.3% | 16.0% | 0.38 |

| Median CIRS score (range) | 5 (0–18) | 5 (0–18) | 4 (0–18) | 0.24 |

| Rai stage (%) | ||||

| 0 | 1.3% | 0.8% | 2.0% | 0.24 |

| 1 or 2 | 40.3% | 38.5% | 42.4% | |

| 3 or 4 | 54.9% | 58.2% | 50.9% | |

| Missing Data | 3.5% | 2.4% | 4.7% | |

| Binet stage (%) | ||||

| A | 8.0% | 7.3% | 8.9% | 0.20 |

| B | 35.5% | 34.0% | 37.2% | |

| C | 51.5% | 54.6% | 47.8% | |

| Missing Data | 5.0% | 4.1% | 6.2% | |

| Number previous therapies (range) | 3 (1–13) | 3 (1–13) | 3 (1–11) | 0.21 |

| β2 microglobulin >3.5 (%) | 78.10% | 78.20% | 78.10% | 0.87 |

| IGHV unmutated (%) | 81.90% | 81.70% | 82.30% | 0.86 |

| Deletion 17p or TP53M (%) | 37.30% | 37.70% | 36.90% | 0.84 |

| Deletion 17p (%) | 22.40% | 22.60% | 22.20% | 0.94 |

| TP53 mutation (%) | 33.20% | 34.60% | 31.50% | 0.35 |

| CLL-IPI Risk Score (%) | ||||

| Low | 2.10% | 2% | 2.20% | 0.98 |

| Intermediate | 12.40% | 12.80% | 11.80% | |

| High | 46.90% | 47.30% | 46.60% | |

| Very High | 34.90% | 35.20% | 34.50% | |

| Missing Data | 3.70% | 2.60% | 4.90% | |

| Median follow-up (months) | 21.4 (0.03–45.6) | 22.7 (0.1–45.6) | 19.5 (0.03–44.3) | <0.0001 |

CLL-IPI in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL

The complete analysis dataset contained 864 patients with a median follow up of 21.4 (range, 0.03–45.3) months and 290 events (death). The CLL-IPI scoring system separated patients into low (2.2% of the total patient population), intermediate (12.8%), high (48.7%), and very high (36.2%) risk groups. While only 15% patients had low or intermediate risk CLL-IPI scores, the frequency of low or intermediate risk CLL-IPI scores was higher among patients treated on Study 115 (rituximab and bendamustine with or without idelalisib) compared with Studies 116 and 119 (rituximab or ofatumumab with or without idelalisib (21.2% vs 9.6%, p<0.0001).

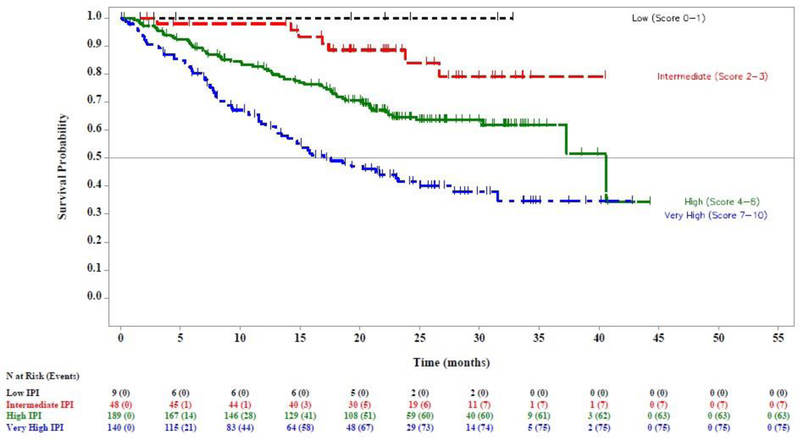

The CLL-IPI risk score was prognostic for OS in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL (log rank test across risk groups p<0.0001; C-statistic of 0.706 [95% CI 0.587–0.813]; Figure 1A). The 24-month OS rate was significantly different between the intermediate, high, and very high CLL-IPI risk groups: intermediate (88.3% [95% CI 79.5–93.5]), high (69.8% [95% CI 64.8–74.2]), and very high risk (52.6% [95% CI 46.5–58.3], Table 3). There was no significant difference in 24-month OS rate between the low and intermediate CLL-IPI risk groups (93.3 vs 88.3%, HR 1.846 (95% CI 0.240–14.183).

Figure 1. Overall survival (OS) by CLL-IPI risk group in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.

(A) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS by CLL-IPI risk group for all patients enrolled and treated in Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119. (B) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS by CLL-IPI risk group for subgroup of patients treated with idelalisib in Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119. (C) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS by CLL-IPI risk group for subgroup of patients treated with comparator therapy in Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119.

Table 3. Survival by CLL-IPI risk group.

Comparison of survival across CLL-IPI risk groups.

| CLL-IPI Risk Group | CLL-IPI score | Patients (%) | 24-month overall survival (95% Cl) | Comparisons | Hazard ratio (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete analysis dataset | n=864 | ||||

| Low | 0–1 | 2.20% | 93.3 (61.3,99.0) | − | − |

| Intermediate | 2–3 | 12.80% | 88.3 (79.5,93.5) | vs Low | 1.846 (0.240, 14.183) |

| High | 4–6 | 48.70% | 69.8(64.8,74.2) | vs Intermediate | 3.044 (1.684, 5.502) |

| Very high | 7–10 | 36.20% | 52.6 (46.5,58.3) | vs High | 1.835 (1.449, 2.325) |

| Idelalisib subgroup | n=478 | ||||

| Low | 0–1 | 2.10% | 88.9 (43.3,98.4) | − | − |

| Intermediate | 2–3 | 13.20% | 91.5 (80.8,96.4) | vs Low | 0.804(0.094,6.888) |

| High | 4–6 | 48.50% | 73.7(67.1,79.2) | vs Intermediate | 3.641(1.466,9.045) |

| Very high | 7–10 | 36.20% | 60.9(52.8,68.1) | vs High | 1.666(1.194,2.326) |

| Comparator subgroup | n=386 | ||||

| Low | 0–1 | 2.30% | 1 | − | − |

| Intermediate | 2–3 | 12.40% | 84.1 (66.7,92.8) | vs Low | 163559.8(0, NR)1 |

| High | 4–6 | 49.00% | 64.7(56.8,71.6) | vs Intermediate | 2.598(1.189,5.674) |

| Very high | 7–10 | 36.30% | 41.5 (32.3,50.4) | vs High | 2.086 (1.491, 2.921) |

Unusually high estimate for hazard ratio is related to absence of death events (n=9, all censored) among patients in the comparator subgroup with low risk CLL-IPI scores.

Impact of treatment on the CLL-IPI scoring system

We undertook a subgroup analyses to determine if idelalisib might impact the CLL-IPI scoring system. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics or CLL-IPI risk factors between the idelalisib subgroup and comparator subgroup (Table 3). The CLL-IPI risk score was prognostic for OS in patients assigned to the comparator subgroup (log rank test across risk groups p<0.0001; C-statistic of 0.736 [95% CI 0.565–0.879]; Figure 1B), and was also prognostic for OS in patients assigned to the idelalisib subgroup (log rank test across risk groups p<0.0001; C-statistic of 0.682 [95% CI 0.509–0.834]; Figure 1C). The interaction between idelalisib treatment and the CLL-IPI scoring system was not significant (Supplemental Table 2). We also demonstrated that the CLL-IPI scoring system is prognostic for OS in patients who receive chemoimmunotherapy (Study 115; C-statistic 0.742, 95% CI 0.563–0.889) or CD20 antibody therapy (Studies 116 and 119; C-statistic 0.670 [95% CI 0.503–0.819]).

Multivariate analysis of CLL-IPI risk factors in relapsed/refractory CLL

We performed a multivariate analysis for OS to determine whether the CLL-IPI risk factors, initially derived and validated in a previously untreated population, are independently prognostic for OS in the relapsed/refractory setting. We also sought to determine whether the prognostic impact of the individual CLL-IPI risk factors, as measured by their hazard ratios in the multivariate model, was comparable in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.

Of the 5 adverse CLL-IPI variables included in the multivariate analysis, age >65 (HR 1.5 [95% CI 1.18–1.91], p=0.001), B2M >3.5mg/L (HR 2.64 [95% CI 1.77–3.94], p<0.0001), IGHV unmutated (HR 1.48 [95% CI 1.06–2.07], p=0.02), and del17p and/or TP53M (HR 2.05 [95% CI 1.63–2.58], p<0.0001) were independently prognostic for OS, but Rai I-IV or Binet B/C staging was not (HR 1.29 [95% CI 0.32–5.2], p=0.72) (Table 4). The regression parameters of the adverse CLL-IPI factors that remained independently prognostic in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL were different from the regression parameters in previously untreated patients.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of CLL-IPI risk factors for overall survival in relapsed/refractory CLL.

Multivariate analyses of CLL-IPI risk factors for overall survival are shown for all patients enrolled and treated on Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119, and for the idelalisib and comparator therapy subgroups.

| Relapsed/Refractory CLL | Idelalisib Subgroup | Comparator Subgroup | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adverse factor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | >65 years | 1.5 (1.18–1.91) | 0.001 | 1.89 (1.34–2.68) | 0.0003 | 1.14 (0.81–1.6) | 0.45 |

| Stage | Rai I-VI or Binet B-C |

1.29 (0.32–5.2) | 0.72 | 234475.12 (0-NR)1 | 0.98 | 0.73 (0.18–3.04) | 0.67 |

| B2M | >3.5mg/L | 2.64 (1.77–3.94) | <0.0001 | 2.22 (1.29–3.79) | 0.0038 | 3.44 (1.87–6.32) | <0.0001 |

| IGHV | Unmutated | 1.48 (1.06–2.07) | 0.0212 | 1.65 (1.02–2.68) | 0.0414 | 1.34 (0.84–2.14) | 0.2169 |

| del17p/TP53M | Deleted or mutated | 2.05 (1.63–2.58) | <0.0001 | 1.86 (1.34–2.58) | 0.0002 | 2.33 (1.68–3.24) | <0.0001 |

Unusually high estimate for hazard ratio is related to absence of death events (n=2, both censored) among patients in the idelalisib subgroup with the adverse factor (Rai I-VI or Binet B-C). B2M, beta-2 microglobulin; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region; del17p, deletion 17p; TP53M, TP53 mutation.

In an effort to determine whether there might be an interaction between idelalisib therapy and the individual CLL-IPI factors, we tested for interactions between treatment (idelalisib vs no idelalisib) and each of the CLL-IPI factors and conducted multivariate analyses for the idelalisib subgroup and the comparator subgroup, respectively. We identified a significant interaction between idelalisib and age on OS (p=0.0359) but with none of the other CLL-IPI factors (Supplementary Table 3). Of the 5 CLL-IPI risk factors, age >65, B2M >3.5mg/L, IGHV unmutated, and del17p/TP53M were independently prognostic for OS in the comparator subgroup, while only B2M >3.5mg/L and del17p/TP53M were independently prognostic for OS in the idelalisib subgroup (Table 4).

Modified CLL-IPI

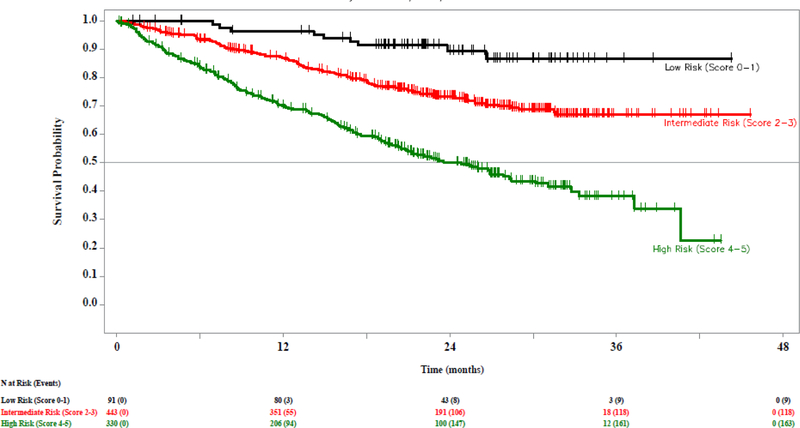

We next evaluated a modified CLL-IPI in an effort to optimize the CLL-IPI scoring system in the relapsed/refractory setting. We modified the cutoff for clinical stage (Rai III-IV/Binet C vs Rai 0-II/Binet A-B) and assigned 1 point to each adverse factor. The resulting model was prognostic for OS (C-statistic 0.695, 95% CI 0.590–0.792; log-rank p <0.0001; Supplemental Figure 1). Based on visual assessment of KM curves, we grouped patients into low (score 0–1), intermediate (score 2–3), and high risk (score 4–5). The resulting modified CLL-IPI separated patients into low (10.5%), intermediate (51.3%), and high (38.2%) risk groups, and was prognostic for OS (C-statistic 0.726, 95% CI 0.606–0.832; log-rank <0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overall survival (OS) by modified CLL-IPI risk group in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.

Kaplan Meier estimate of OS by modified CLL-IPI risk group for all patients enrolled and treated in Study 115, Study 116, and Study 119.

Discussion

The CLL-IPI is a risk-weighted scoring system that is prognostic for OS among patients with previously untreated CLL receiving chemoimmunotherapy,24 but its prognostic utility has not been evaluated previously in the relapsed/refractory setting or in the context of novel targeted therapies. Using patient-level data from 3 randomized trials evaluating idelalisib in relapsed/refractory CLL (rituximab-bendamustine ± idelalisib, rituximab ± idelalisib, and ofatumumab ± idelalisib), we have demonstrated that the CLL-IPI is prognostic for OS in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. However, most patients with relapsed/refractory disease are poor risk according to the CLL-IPI risk score, and our multivariate analysis suggests that the relative contribution of each adverse risk factor might be different in the relapsed/refractory setting. Thus, a reassessment of the weighting of the individual variables might optimize the model in the relapsed/refractory setting.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to validate the CLL-IPI scoring system in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL or in patients treated with novel targeted therapies. We have demonstrated that the CLL-IPI scoring system is prognostic for OS among patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. In this cohort, the 24-month OS rate was 52.6% for patients at very high risk and 69.8% for patients at high risk. The Kaplan-Meier OS curves for patients with low and intermediate risk CLL-IPI scores appear similar, with a 24-month OS rate of approximately 90%. However, these data are underpowered to estimate the OS among low risk patients given very few patients in this risk group, and it is unknown whether there is a survival difference between low and intermediate risk patients.

The CLL-IPI was developed in a population of previously untreated patients who received either chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.24 We have confirmed that the CLL-IPI scoring system can be applied to patients with relapsed/refractory CLL treated with idelalisib, although its discriminatory value appeared slightly less robust among patients in the idelalisib subgroup (C-statistic, 0.682) compared with those in the comparator subgroup (C-statistic, 0.736). This might reflect that idelalisib partially overcomes the negative impact of a high or very high risk CLL-IPI score. Given these data, the CLL-IPI scoring system may be applied to patients with relapsed/refractory CLL including those treated with idelalisib. It is possible that these data might apply to patients treated with alternative targeted agents (e.g. BTK inhibitors or BH3-mimetic BCL2 inhibitors), although additional validation is needed.

However, patients with relapsed/refractory CLL are not evenly distributed among CLL-IPI risk groups in our series, with 84.9% of patients in the high or very high risk groups. We attribute this to a high frequency of the individual adverse CLL-IPI risk factors in the relapsed/refractory setting: 96.8% were Rai stage I-IV or Binet stage B/C, 81.9% had unmutated IGHV, 78.1% had a B2M >3.5mg/L, and 37.3% had deletion 17p or TP53 mutation. Additionally, presence of del17p and/or TP53M (4 points), IGHV mutational status (2 points), and B2M (2 points) disproportionately contribute to the CLL-IPI risk score relative to age (1 point) and clinical stage (1 point), but our multivariate analyses suggest that the individual CLL-IPI variables contribute similarly to prognosis.

We therefore explored a modified CLL-IPI to optimize the CLL-IPI model in the relapsed/refractory setting. By assigning 1 point to each adverse factor and using a more balanced cutoff for clinical stage, the modified CLL-IPI resulted in a better distribution among risk groups and an improved discriminatory value (C-statistic 0.726) in the relapsed/refractory setting. However, this exploratory analysis did not account for baseline variables not assessed in the derivation of the CLL-IPI that might be critical in the relapsed/refractory setting, e.g., number of prior therapies or time from initiation of last therapy. Moreover, factors that were previously evaluated but ultimately not selected for the final CLL-IPI model might emerge as critical risk factors in the relapsed/refractory setting. Given these considerations, a comprehensive analysis of candidate prognostic factors in an expanded dataset of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL treated with targeted therapies is ongoing.

In summary, the CLL-IPI provides prognostic information in the relapsed/refractory setting. However, patients with relapsed/refractory CLL are not evenly distributed among CLL-IPI risk groups and our multivariate analyses suggest that the relative contribution of each adverse risk factor might be different in the relapsed/refractory setting. A modified CLL-IPI partially addresses these limitations, but this approach is restricted to the CLL-IPI variables and does not account for alternative baseline factors which might be critical in this setting. Therefore, a more comprehensive analysis of candidate prognostic factors for OS in an expanded dataset is ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated as well as all the clinicians and research staff contributing to the conduct of the clinical trials. Jacob D. Soumerai, Ai Ni, and Andrew D. Zelenetz conceived of and designed the research study. Andrew D. Zelenetz, Jeffrey Jones, Richard R. Furman, Jeffrey P. Sharman, Adeboye H. Adewoye, Ronald Dubowy, and Lyndah Dreiling oversaw data collection for the trials. Guan Xing and Julie Huang conducted the statistical analysis. Jacob D. Soumerai, Ai Ni, and Andrew D. Zelenetz analyzed the data. Jacob D. Soumerai, Ai Ni, and Andrew D. Zelenetz wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Details

This work was supported by the Lymphoma Research Foundation under Lymphoma Clinical Research Mentoring Program Grant number (498061) and Lymphoma Clinical Research Mentoring Program (498061); the NIH/NCI under Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748); and the clinical trials were supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

Ai Ni has no potential conflicts of interest; Jacob D. Soumerai received consultancy fees from Verastem; Richard R. Furman received consultancy fees from Janssen, Gilead, Pharmacyclics, Abbvie, Verastem, TG Therapeutics, Genentech, Incyte, Loxo Oncology, and Sunesis. Jeffrey Jones received personal fees as an advisory board member for Gilead; Jeffrey P. Sharman received consultancy fees, research funding, and honoraria from Gilead and TG therapeutics; Michael Hallek received consultancy fees, research funding, and honoraria from Abbvie, Janssen, and Gilead, and speakers bureau fees from Gilead; Andrew D. Zelenetz received consultancy fees from Genentech, Roche, Gilead, Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, Novartis, and Adaptive Biotechnologies, research funding from MEI Pharma, Roche, and Gilead, and served as the DMC chair for Beigene; Guan Xing, Julie Huang, Ming Lin, Adeboye H. Adewoye, Ronald Dubowy, and Lyndah Dreiling are employed by Gilead.

References

- 1.Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite E, Chanana A, Levy R, Pasternack B. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. Blood 46:219–234. 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binet JL, Auquier A, Dighiero G, et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer 48:198–206. 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 94:1840–1847. 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig VH Genes Are Associated With a More Aggressive Form of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 94 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobin G, Thunberg U, Johnson A, et al. Somatically mutated Ig VH3–21 genes characterize a new subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 99:2262–2264. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobin G, Thunberg U, Johnson A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemias utilizing the VH3–21 gene display highly restricted Vlambda2–14 gene use and homologous CDR3s: implicating recognition of a common antigen epitope. Blood 101:4952–4957. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zenz T, Benner A, Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and treatment resistance in cancer: the role of the p53 pathway. Cell Cycle 7:3810–3814. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stilgenbauer S, Schnaiter A, Paschka P, et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the CLL8 trial. Blood 123:3247–3254. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 343:1910–1916. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Döhner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, et al. p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non-response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood 85:1580–1589. 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Genetic and Molecular Features Predicting Outcome in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results From the US Intergroup Phase III Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol 25:799–804. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baliakas P, Hadzidimitriou A, Sutton L-A, et al. Recurrent mutations refine prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 29:329–336. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi D, Rasi S, Fabbri G, et al. Mutations of NOTCH1 are an independent predictor of survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 119:521–529. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Lawrence MS, Wan Y, et al. SF3B1 and Other Novel Cancer Genes in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 365:2497–2506. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kröber A, Seiler T, Benner A, et al. V(H) mutation status, CD38 expression level, genomic aberrations, and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 100:1410–1416. 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rassenti LZ, Huynh L, Toy TL, et al. ZAP-70 Compared with Immunoglobulin Heavy-Chain Gene Mutation Status as a Predictor of Disease Progression in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 351:893–901. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Principe MI, Del Poeta G, Buccisano F, et al. Clinical significance of ZAP-70 protein expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 108:853–861. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crespo M, Bosch F, Villamor N, et al. ZAP-70 Expression as a Surrogate for Immunoglobulin-Variable-Region Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 348:1764–1775. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiestner A, Rosenwald A, Barry TS, et al. ZAP-70 expression identifies a chronic lymphocytic leukemia subtype with unmutated immunoglobulin genes, inferior clinical outcome, and distinct gene expression profile. Blood 101:4944–4951. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Wang X, et al. Prognostic nomogram and index for overall survival in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 109:4679–4685. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Wang X, et al. Multivariable model for time to first treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 29:4088–4095. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haferlach C, Dicker F, Weiss T, et al. Toward a comprehensive prognostic scoring system in chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on a combination of genetic parameters. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49:851–859. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi D, Rasi S, Spina V, et al. Integrated mutational and cytogenetic analysis identifies new prognostic subgroups in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 121:1403–1412. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The CLL-IPI Working Group. An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 17:779–790. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 369:32 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 371:213–223. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JR, Byrd JC, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110δ, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 123:3390–3397. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with Venetoclax in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 374:311–322. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zelenetz AD, Barrientos JC, Brown JR, et al. Idelalisib or placebo in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: interim results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 18:297–311. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and Rituximab in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 370:997–1007. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones JA, Robak T, Brown JR, et al. Efficacy and safety of idelalisib in combination with ofatumumab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 4:e114–e126. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.