Abstract

Introduction:

Managing fistulizing perianal disease is among the most challenging aspects of treating patients with Crohn’s disease. Perianal fistulas are indicative of poor long-term prognosis. They are commonly associated with significant morbidities and can have detrimental effects on quality of life. While durable fistula closure is ideal, it is uncommon.

In optimal circumstances, reported long-term fistula healing rates are only slightly higher than 50% and recurrence is common. Achieving these results requires a combined medical and surgical approach, highlighting the importance of a highly skilled and collaborative multi-disciplinary team.

In recent years, advances in imaging, biologic therapies and surgical techniques have lent to growing enthusiasm amongst treatment teams, however the most advantageous approach is yet to be determined.

Areas covered:

Here we review current management approaches, incorporating recent guidelines and novel therapies. Additionally, we discuss recently published and ongoing studies that will likely impact practice in the coming years.

Expert opinion:

Investing in concerted collaborative multi-institutional efforts will be necessary to better define optimal timing and dosing of medical therapy, as well as to identify ideal timing and approach of surgical interventions. Standardizing outcome measures can facilitate these efforts. Clearly, experienced multidisciplinary teams will be paramount in this process.

Keywords: Anorectal Fistula, Anti-TNF, Crohn’s Disease, Perianal Fistula, Seton, Mesenchymal Stem Cells

1. Introduction

There are over half a million people in the U.S. living with Crohn’s disease(CD)[1]. Approximately 10% present with perianal disease; this can include skin tags, hemorrhoids, fissures, ulcers, strictures, abscesses and fistulas (perianal, rectovaginal and more rarely, urologic fistulas)[2]. Though perianal fistulas are present in only a small portion of patients at diagnosis, the probability of developing them increases with time, and perianal fistulas ultimately effect approximately 25% of patients with CD[2–5]. Patients with CD of the colon or rectum are most commonly effected[6].

The presence of perianal disease is a poor prognostic indicator for patients with CD[7]. In addition to causing pain, perineal disfigurement, and occasionally fecal incontinence, very severe perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (PFCD) can often require proctectomy and permanent ostomy[8]. These complications can have detrimental effects on quality of life. Despite significant advances in understanding the pathobiology of the underlying disease, and the paralleled increase in availability of targeted biologic therapies, the long-term healing rates of perianal fistulas remain disappointing[2,7].

While this is true in simple fistulas, it is perhaps most pronounced in complex perianal fistulas, which represent approximately 80% of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease[2,9]. A recent study showed that even with initial healing in 65% of patients with complex perianal disease, a dismal 37% were in remission after a median 10-year follow-up[2].

Here we discuss treatment algorithms incorporating the most up to date recommendations, as well as new developments in therapies and techniques.

2. Diagnosis and work-up

Magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI) is universally regarded as the gold standard imaging modality for perianal CD[3,10,11]. Current European guidelines recommend that in routine practice, MRI is the initial procedure of choice in diagnosing PFCD[11]. After ruling out anorectal strictures, endoanal ultrasound (EUS) is an acceptable alternative[3,11]. However, the accuracy of ultrasound can be provider dependent.

When an abscess is accompanied by sepsis, examination under anesthesia (EUA) with drainage of purulence and placement of seton is indicated, and MRI should be performed prior to drainage only if it is immediately available[10,11]. Likewise, when a fistula is confirmed, EUA in the hands of an experienced surgeon is the gold standard[11]. Additionally, drainage of abscess and placement of a draining seton should be performed prior to starting medical therapy[3].

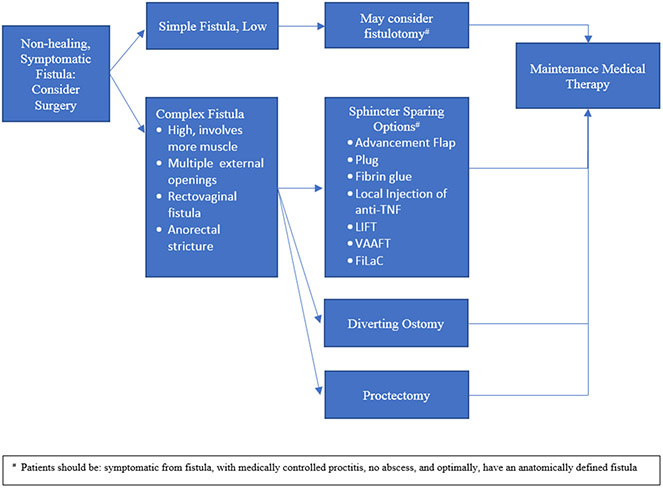

After diagnosis of a fistula and management of associated abscesses, the presence of active rectal disease assists in determining further management. Proctitis is known to have negative effects on fistula healing and has been associated with increased fistula recurrence. Its presence increases the complexity of management, therefore any fistula accompanied by proctitis is regarded as complex disease[8,12]. Thus, examination of the rectal mucosa, either by rigid proctoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy, is an essential step in work-up. Fistulas are generally classified as simple or complex. They are considered complex when they are higher/involving a significant portion of the sphincter, if there are multiple tracts, or if they are associated with fluctuance. Rectovaginal fistulas and fistulas accompanied by anorectal stricture are also regarded as complex[13]. Conversely, a simple fistula is generally low, with minimal involvement of the sphincter and may be amenable to treatment with simple fistulotomy[13]. It is important to establish these designations early, as they assist in decision-making with regard to further management (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm for surgical approach in PFCD.

3. Medical Management

Management of PFCD is a complex process and there are insufficient data to dictate treatment with perfect certainty, therefore a significant portion of management is left to clinical expertise. Guidelines and consensus statements, such as those issued in 2018 by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) (See Table 1), and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization [ECCO] with the European Society of Colo-Proctology [ESCP] can help direct treatment of PFCD[3,11] (See Table 2). Despite these types of helpful recommendations, the lack of strong data in management approaches leaves a level of ambiguity making collaboration and multidisciplinary participation imperative[14].

Table 1.

American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guidelines—Management of Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease.

| Level of recommendation |

Level of Evidence | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | ||

| Moderate | Infliximab is effective and should be considered in treating perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease Infliximab may be effective and should be considered in treating enterocutaneous and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease Tacrolimus can be administered for short-term treatment of perianal and cutaneous fistulas in Crohn’s disease Antibiotics (imidazoles) may be effective and should be considered in treating simple perianal fistulas The addition of antibiotics to infliximab is more effective than infliximab alone and should be considered in treating perianal fistulas Placement of setons increases the efficacy of infliximab and should be considered in treating perianal fistulas |

|

| Low | Adalimumab and certolizumab pegol may be effective and should be considered in treating perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease Thiopurines (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine) may be effective and should be considered in treating fistulizing Crohn’s disease |

|

| Conditional | ||

| Very Low | Drainage of abscesses (surgically or percutaneously) should be undertaken before treatment of fistulizing Crohn’s disease with anti-TNF agents |

Adapted from [3].

Table 2.

ECCO-ECSP 2018 consensus statements regarding diagnosis and management of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease.

| Level of Evidence |

ECCO-ESCP Consensus statements |

|---|---|

| 1 | • The specificity and sensitivity of both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoscopic anorectal ultrasound (EUS) imaging modalities are increased when combined with examination under anesthetic [EUA]. • Infliximab, seton drainage, or a combination of drainage and medical therapy should be used as maintenance therapy. |

| 2 | • Contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI is considered the initial procedure for the assessment of perianal fistulizing CD. • If rectal stenosis is excluded, EUS is a good alternative. • Since the presence of concomitant rectosigmoid inflammation has prognostic and therapeutic relevance, proctosigmoidoscopy should be used routinely in the initial evaluation. • Seton placement after surgical treatment of sepsis is recommended for complex fistulas. The timing of removal depends on subsequent therapy. • In evaluating the response to medical or surgical treatment in routine practice, clinical assessment [decreased drainage] is usually sufficient. • Thiopurines, adalimumab, seton drainage, or a combination of drainage and medical therapy should be used as maintenance therapy. |

| 3 | • Fistulography is not recommended. • Symptomatic simple perianal fistulas require treatment. Seton placement in combination with antibiotics [metronidazole and/or ciprofloxacin] is the preferred strategy. • The indications for surgery aiming to close a fistula-in- ano in CD include a symptomatic patient, with no concomitant abscess, with medically controlled proctitis, and a preferably anatomically defined fistula tract. • There is a real likelihood that a fistula will close after removal of the seton in the absence of abscess, proctitis, or stenosis. • The use of cutting setons in perianal CD is not recommended and may result in keyhole deformity and fecal incontinence. • Fecal diversion is effective in reducing symptoms in perianal CD in two-thirds of patients and may improve quality of life, but only one-fifth of these patients are stoma-free in the long term. |

| 4 | • In recurrent refractory simple fistulizing disease not responding to antibiotics, thiopurines or anti-TNFs can be used as second-line therapy. • Imaging before surgical drainage is recommended. EUA for surgical drainage of sepsis is mandatory for complex fistulas. • In complex fistulas, abscess drainage and loose seton placement should be performed. |

| 5 | • If a perianal fistula is detected, EUA is considered the gold standard in the hands of an experienced surgeon. • There is no consensus for classifying perianal fistulas in CD. In clinical practice, most experts use a classification of ‘simple’ or ‘complex’. • In an uncomplicated low anal fistula, simple fistulotomy may be discussed • The presence of a perianal abscess should be ruled out, and if present should be drained. • Active luminal Crohn’s disease should be treated if present, in conjunction with appropriate surgical management of fistulas. • MRI or anal EUS in combination with clinical assessment is recommended to evaluate the improvement of fistula track inflammation. • Patients refractory to medical treatment should be considered for a diverting ostomy, with proctectomy as the last resort. • Entero-enteric and entero-vesical fistulae often require surgical resection. • Surgery is strongly recommended for entero-enteric fistulas if associated with abscess and bowel stricture and if they cause excessive diarrhea and malabsorption. • Asymptomatic low anal-introital fistulae do not need surgical treatment. • If a patient has a symptomatic recto-vaginal fistula, surgery is usually necessary [including diverting ostomy]. • Active CD with rectal inflammation should be treated medically before surgery, and after surgery to prevent recurrence. • The type of surgical procedure should be tailored to the anatomy of the fistula tracts and of the anus [exposure, strictures, access, previous surgery] and the expertise of the surgeon. • Fistulotomy in the anterior perineum of a female patient should be avoided. • When treating perianal fistula with anti-TNF, seton removal is probably best done after the induction phase of anti-TNF is completed and resolution of proctitis has been achieved |

Adapted from [11].

Regarding medical management, there is some debate as to whether a ‘top-down’ or ‘step up’ approach is more beneficial in CD. However, due to its general association with poor prognosis, a ‘top down’ approach is preferable and may be associated with decreased need for surgery in patients with PFCD[15]. This strategy is negated in the rare circumstance of a simple fistula in the absence of proctitis or active luminal disease, in which case recommendations suggest placing a draining seton, treating with antibiotics, and performing simple fistulotomy[3,11]. However, for the majority of patients, who experience complex perianal fistulizing disease, a ‘top down’ approach, starting with anti-TNF therapy, in combination with seton drainage, antibiotics, and in most circumstances thiopurines, is suggested[3,10,11] (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Global Consensus 2014: Recommendations regarding medical therapies for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease.

| Grade of Recommendation |

Consensus Statement |

|---|---|

| 1A: Strong recommendation, high quality evidence | Infliximab is moderately effective for the induction and maintenance of fistula closure. |

| 1B: Strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence | Adalimumab is moderately effective for the induction and maintenance of fistula closure. |

| 1C: Strong recommendation, low quality evidence | Evidence for efficacy of certolizumab pegol is weaker |

| The short-term goals in the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease are abscess drainage and reduction of symptoms. The long-term goals are resolving fistula discharge, improvement in quality of life, fistula healing, preserving continence, and avoiding proctectomy with stoma. | |

| There is no demonstrated role for aminosalicylates or corticosteroids in perianal CD. | |

| Antibiotics, namely metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, improve fistula symptoms and may contribute to healing. | |

| 2C: Weak recommendation, low quality evidence | Thiopurines may have a moderate effect in the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Evidence for the efficacy of methotrexate and ciclosporin is limited. Tacrolimus is effective for treating active fistulas; when used, therapeutic drug monitoring is required to minimize toxicity. |

| Anti-TNF and thiopurine combination therapy may lead to higher fistula healing response and closure rate compared to monotherapy. |

Adapted from [10].

3.1. TNF-α Inhibitors

TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine that is overproduced in the mucosa and lamina propria of bowel effected by CD[16]. Infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) and certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) are monoclonal antibodies directed against TNF-α. TNF-α inhibitors are the best studied and most reliably effective medical therapy for PFCD. Their precise mechanism of action is incompletely understood, however, it is thought that by binding TNF-α, these drugs interrupt the downstream inflammatory cascade, allowing for resolution of inflammation and mucosal healing in CD[17].

3.1.1. Infliximab

Infliximab was the first Crohn’s specific drug approved by the FDA in 1998. This impacts the data available for this drug, and others, in several ways. Because it is the first, and oldest drug, there is more data on its efficacy and increased clinical experience with its use. Additionally, since it is generally considered first line therapy, many studies for subsequent drugs may be affected by inclusion of patients who have previously been treated with infliximab, a process which selects patients who are less likely to respond to subsequent biologic therapies, thus skewing results for other therapies.

3.1.1.1. Efficacy in healing fistulizing disease

The initial study demonstrating the utility of infliximab in patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s was published in 1999. In a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Present et al. studied the effect of infliximab on fistula activity in 94 patients with fistulizing CD, 85 (90%) had perianal fistulas. The primary endpoint, overall response rate (defined as a decrease from baseline of at least 50% in the number of draining fistulas), was 62% with infliximab versus 26% with placebo (p=0.002). Complete response, defined as absence of drainage on two consecutive visits, was seen in 46% treated with infliximab versus 13% with placebo (p=0.001)[18]. While these data provide evidence for efficacy in terms its ability to induce reduction or cessation of fistula drainage, the definitions of the primary endpoint and complete response are relatively subjective, and there is limited data regarding durability of the response (see following paragraph).

3.1.1.2. ACCENT II—Maintenance therapy, duration of response

The next study, ACCENT II, was a multicenter, randomized, double blind study designed to investigate the utility of infliximab as a maintenance therapy. Among patients who initially responded (as defined in the previous paragraph), investigators assessed the time to loss of response in patients receiving maintenance infliximab versus placebo. In this study, Sands et al. included 282 patients, the majority (n=246, 87%) with perianal fistulizing disease. The initial response rate to induction therapy was 195/282 (67%). Among these responding patients, those receiving maintenance infliximab had a significantly longer time to loss of response in comparison to those receiving placebo (>40 weeks versus 14 weeks, p<0.001). At 54 weeks, patients randomized to the infliximab maintenance group were more likely to have a complete response (36% versus 19%; p=0.009), defined as absence of draining fistulas.[19] These data indicate that even among those with continuing infliximab dosing, loss of response begins after less than a year of therapy. Further, infliximab maintenance dosing is necessary to preserve the initial response to therapy. Loss of response to therapy may contribute to the finding that approximately half of patients who initially respond to infliximab will experience recurrence of draining fistulas in absence of additional therapies.

3.1.1.3. Infliximab in combination with thiopurines

3.1.1.3.1. SONIC

In 2010, Colombel et al. reported on a multicenter, double blind study investigating the role of combination therapy. Patients were randomized to receive azathioprine, infliximab, or combination therapy with both azathioprine and infliximab. The primary end-point, steroid free remission at week 26, was 30.0% in the azathioprine group, 44.4% in the infliximab group, and 56.8% in the combined therapy group (p versus azathioprine= 0.006; p versus infliximab=0.02). The trial was extended to 50 weeks, and the rates of steroid free remission were 54.7%, 60.8% and 72.2%, respectively. Infliximab monotherapy was no longer superior to azathioprine montherapy. Similarly, combination therapy was no longer superior to infliximab monotherapy. However, combination therapy maintained its improved efficacy in comparison to azathioprine monotherapy (p=0.01)[20]. Though this study did not specifically address fistula healing, results indicate that azathioprine can be used as an adjunct, to preserve drug efficacy (and prevent immunogenicity) when treating patients with infliximab.

3.1.1.3.2. Retrospective French study

Similarly, in 2013 Bouguen et al. reviewed the medical records of 156 patients with PFCD and reported that at 5 years, 72 patients (46%) had fistula closure and at maximal follow up 86 patients (55%) had complete closure. Multivariate analysis revealed that in patients who had not previously been treated with immunosuppressants, combined therapy was associated with an increased rate of fistula closure (HR 2.58, 1.16–5.6; p=0.02)[21]. While retrospective in nature, the data presented here are supportive for an adjunctive role of thiopurines in anti-TNF therapy.

The ACG practice guidelines encourages the practice of using infliximab in combination with thiopurines in treating PFCD[3].

3.1.1.4. Infliximab in combination with antibiotics

In 2004 a group from the Netherlands published a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study investigating the efficacy of ciprofloxacin in addition to infliximab in treating PFCD. 24 patients were randomized to infliximab in combination with ciprofloxacin or placebo for 12 weeks. Primary endpoint was 50% reduction in number of draining fistula tracts. At 18 weeks 8/11 (73%) patients receiving ciprofloxacin had response while 5/13 (39%) taking placebo had response (p=0.12). Using logistic regression, the authors reported a tendency for better response with ciprofloxacin (OR 2.37, CI0.94–5.98, p=0.07)[22]. Overall, the study showed no significant difference in outcomes with the addition of antibiotics. It would likely require more patients to determine with certainty, whether there was a benefit. Still, given the trend toward benefit, and improved data supporting a role for antibiotics in combination with adalimumab (discussed in adalimumab section, below), the addition of antibiotics to infliximab is commonly included in guidelines for treating PFCD[3,10,23,24].

Triple therapy with infliximab, thiopurine and antibiotics has not been formally studied. However, the authors frequently employ a triple therapy approach based on the studies discussed above showing adjunctive benefit of both thiopurines, and antibiotics, with infliximab.

3.1.1.5. Effect of drug concentrations on healing of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease

More recent data suggests that higher serum drug concentrations may be associated with higher rates of fistula healing[25,26].

In 2017, Yarur et al. described a cross-sectional study of 117 patients with PFCD who were receiving infliximab therapy. The group indicated that at a median of 29 weeks of infliximab therapy, those with perianal fistula healing (defined as absence of drainage) had higher serum infliximab concentrations in comparison to those who remained with active disease (15.8 μg/mL versus 4.4 μg/mL; p<0.001). When the group assessed each quartile of serum infliximab concentrations they found that >10.1 mcg/ml and >20.3 mcg/ml were associated with three- and eight-fold chance of fistula healing, respectively. Similarly, patients with fistula healing had a lower likelihood of having serum infliximab antibodies (OR 0.04 CI 0.004–0.3, p<0.0001)[25].

A similar study, published the same year, reported comparable results in a retrospective cohort of 26 patients with PFCD. On multivariate analysis, Davidov et al. found that infliximab concentrations at week 2 and week 6 predicted response at week 14 and week 30[27]. Shortly thereafter, El-Matary et al. examined serum anti-TNF concentrations in 27 children under 17 with PFCD. In this study pre-4th dose trough concentrations were significantly higher in patients with fistula healing, and predicted response at week 24 (OR 0.80, CI 0.64–0.97, p=0.007)[26].

Taken together, these data confirm that serum infliximab concentrations correlate with clinical response both during initial induction doses, and also after more prolonged therapy. An improved understanding of the association between serum drug concentrations and disease activity may assist in developing new strategies to optimize dosing schedules and better indicate timing for converting to alternative therapies.

3.1.2. Adalimumab

Whereas infliximab is a mouse-human chimeric antibody, adalimumab is a fully humanized antibody against TNF. Fistula closure was not a primary endpoint for any randomized controlled trials involving adalimumab, however, three randomized controlled trials investigated the effect of adalimumab on fistula healing in secondary analysis[28,29]. It must be understood that if patients are recruited for the presence of moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease, that only 10–15% of patients with have actively draining perianal fistulas at baseline. Therefore, if the study is statistically powered for assessing Crohn’s disease endpoints, then it will be vastly underpowered for assessing fistula closure outcomes in the small subset of patients with draining fistulas.

3.1.2.1. Dose response in anti-TNF naïve patients—CLASSIC I

In 2006 Hanauer et al. reported a randomized controlled trial investigating the dose response of adalimumab in 299 patients who had never been treated with anti-TNF therapy. Patients were randomized to placebo or adalimumab at three different doses. 32 of 299 (11%) had PFCD at baseline, and at week 4 there was no difference in fistula healing rates across groups[28]. This outcome is not unexpected given the short duration of the trial (4 weeks) and the very limited statistical power for fistula outcome measures.

3.1.2.2. Efficacy in patients who failed prior anti-TNF therapy with infliximab—GAIN

In 2007, Sandborn et al. reported results from a randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled trial, designed to determine whether patients who could not tolerate, or who had lost response to infliximab, could gain benefit with adalimumab. The primary endpoint was induction of remission at week 4. 325 patients were randomized to adalimumab or placebo, 45 (14%) had either enterocutaneous or perianal fistulas. At week 4 there was no difference in healing based on treatment group[29]. Similar to the CLASSIC I trial, these results should be accepted with caution, given the short duration of the trial (4 weeks) and the limited statistical power for fistula outcome measures.

3.1.2.3. Maintenance therapy—CHARM

In 2007, Colombel et al. published a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial aimed at defining the capacity of adalimumab to maintain disease response and remission. 778 patients were randomized to placebo, adalimumab every other week, or adalimumab weekly. Of these patients, 130, representing 15.2% of the study population, had draining enterocutaneous or perianal fistulas. Fistula closure was more common among patients receiving adalimumab at both 26 weeks (30% versus 13%, p=0.043) and 52 weeks (33% versus 13%, p=0.016)[30]. An open label extension of the trial was performed and among patients who had fistula healing at 56 weeks, 90% maintained fistula healing a year later[31]. The results of the CHARM trial, which had more patients and longer follow-up in the subgroup analysis than in the preceding CLASSIC 1 and GAIN trials, demonstrated significantly improved fistula healing with adalimumab.

3.1.2.4. CHOICE

Data from a phase IIIb open-label, single-arm trial supports adalimumab induced fistula healing similar to the CHARM trial. 673 patients who had failed infliximab therapy were enrolled and treated with adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy. Among 88 (13%) patients with enterocutaneous or perianal fistulas, 34 (40%) had fistula healing at the time of their last visit (range 4–36 weeks)[32].

While earlier trials had suggested minimal benefit of adalimumab in the healing of fistula disease, later studies, with improved patient numbers and increased follow-up, indicate that adalimumab is effective in promoting fistula healing. Still, the quality of this data is only moderate, since it is limited to subgroup analysis.

3.1.2.5. Adalimumab in combination with antibiotics: ADAlimumab for the treatment of perianal FIstulas in Crohn’s disease (ADAFI)

In a multi-institutional randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, Dewint et al. showed that the addition of ciprofloxacin to adalimumab resulted in superior healing in comparison to adalimumab monotherapy in PFCD. Patients with perianal fistulas (n=76) were randomized to adalimumab alone or in combination with ciprofloxacin for 12 weeks. Adalimumab was then continued as monotherapy and disease was again assessed at 24 weeks. Primary outcome was clinical response, defined as 50% fistula closure at 12 weeks. In comparison to placebo, the addition of ciprofloxacin resulted in improved clinical response (71% versus 47%, p=0.047) and fistula closure (65% and 33%, p=0.009) at 12 weeks. This finding was not maintained at 24 weeks (62% versus 47%, p=0.22 and 53% and 33%, p=0.098, respectively)[24].

With more patients enrolled than the trial of antibiotics in combination with infliximab, this study demonstrates the benefit of adding antibiotics to anti-anti-TNF therapy to induce fistula healing [22]. However, the lack of difference in treatment group outcomes at 24 weeks indicates loss of this effect over time. It follows to conclude that the role of antibiotics is likely to assist in induction of response, rather than in maintenance of response. Alternatively, antibiotics can potentially be continued as chronic maintenance therapy, along with anti-TNF therapy.

3.1.2.6. Biosimilars

Anti-TNF therapies have been transformative in the management of CD. However, the cost burden of these therapies is significant. While a minority of patients are treated with biologics, the cost of these medications represents a majority of all pharmacologic expenses for patients with CD[33,34]. As the patents for the original drugs expire, pharmaceutical companies generate biologic products that are more reasonably priced and functionally similar to the reference product. However, due to variability in manufacturing processes of biologic drugs, these drugs have unavoidable differences at clinically inactive sites. The term biosimilar is therefore used to describe these differences and clarify the distinction from generic drugs, which are the exact same compound. There are no specific studies investigating the efficacy of biosimilars in fistulizing CD. Still, the stringent efficacy requirements for FDA approval of these drugs suggests that they can be used with expectations that they will have similar outcomes to their reference drugs.

3.1.3. Antibiotics

Antibiotics may be useful as primary therapy in healing Crohn’s related fistulas. In fact, simple fistulas may be managed by primarily with seton drainage and antibiotics[3,11]. The purpose of antibiotics, used in this capacity is not to control sepsis, since adequate drainage generally accomplishes this. Rather, in combination with seton, antibiotics are thought to assist in promoting tissue healing.

Except in simple fistulas, antibiotic monotherapy is unlikely to result in healing. However, as discussed above, in combination with other medical therapies, antibiotics may be used to promote fistula healing[22,24,35]. Similarly, data regarding antibiotic use in combination with thiopurines is discussed below[35]. The ACG recognizes the improved efficacy of infliximab in combination with antibiotics and recommends consideration of using antibiotics as an adjunct[3].

3.1.4. Thiopurines

There are no randomized studies evaluating the efficacy of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) in healing PFCD. Data regarding the utility of thiopurine monotherapy is derived from sub-analysis of an early randomized trial and meta-analysis including this, and smaller studies. The onset of action for thiopurines is generally three to four months[36]. In PFCD, where symptoms can be severe and disease threatens sphincter integrity and continence, this delay in onset makes using thiopurine monotherapy impractical. With more recent data demonstrating the clear superiority of anti-TNF therapy in complicated CD, current investigations have focused on the value of thiopurines as an adjunct to anti-TNF therapy.

3.1.4.1. Value of thiopurine monotherapy in fistula healing

Subgroup-analysis of a 1980 study designed to assess the efficacy of 6-MP in treating CD revealed a higher likelihood of fistula healing in patients treated with 6-MP in comparison to those receiving placebo. In this trial, Present et al. included 83 patients, and performed sub-analysis on 36 patients with fistulizing disease. Most fistulas were perianal; 31% of patients in the 6-MP group had fistula closure compared with only 6% in the placebo group[36]. Though this study is limited by small sample size, the increased number of patients with fistula closure in the 6-MP group suggests that thiopurines may have some role in promoting healing.

Pearson et al. then included this study in a meta-analysis along with 4 smaller placebo-controlled trials in 1995. They found that patients receiving thiopurines were more likely to have fistula response, defined as complete healing or decreased discharge, in comparison to those receiving placebo. (54% versus 21%, respectively). Odds ratio of fistula improvement in response to thiopurines was 4.44 (CI, 1.50 to 13.20). Still, these results must be considered with some scrutiny, as approximately half the data were derived from the aforementioned study, by Present et al[36,37].

In 2016 Cochrane Review found no difference in fistula response among patients treated with azathioprine versus placebo (RR 2.0, CI 0.67 to 5.93)[38]. However, the Cochrane analysis was extremely limited given that they included only 18 patients and the overall quality of data for included patients was found to be low. This gives some perspective on the results presented in the Pearson meta-analysis discussed above, since the Cochrane Review excluded most of the studies reported in the Pearson meta-analysis on methodologic and quality basis.

3.1.4.2. Thiopurines as an adjunct in fistula healing

The above data indicate that in fistulizing Crohn’s disease, thiopurine monotherapy is, at best, equivocal, and, the unambiguous efficacy of anti-TNF therapy in treating complicated CD generally negates the use thiopurine monotherapy for this indication. Rather, the value of thiopurines in treatment of PFCD is ostensibly due to their synergistic effects on healing when used in combination with anti-TNF therapies and/or antibiotics[20,35].

3.1.4.3. Thiopurines combined with anti-TNF

As illustrated in the prior section addressing infliximab, Columbel et al. described a complimentary effect with the addition of azathioprine to anti-TNF therapy, which resulted in higher likelihood of achieving steroid free clinical remission in the general study population[20].

3.1.4.4. Thiopurines combined with antibiotics

In a prospective, open-label study Dejaco et al. explored the effect of adding azathioprine to antibiotics in fistula healing. 52 patients with PFCD were treated with an 8-week course of antibiotics alone or in combination with azathioprine. Patients receiving azathioprine were more likely to experience fistula improvement than those not receiving azathioprine (48% versus 15%, p=0.03)[35]. Whereas results of azathioprine monotherapy were more ambiguous, these data suggest that when used in combination with antibiotic therapy, azathioprine exhibits improved efficacy, suggesting an additive effect.

While thiopurines do not appear to have a role as primary therapy in PFCD, they may be more useful in inducing and maintaining remission when used in combination with other therapies. Current American guidelines indicate that thiopurines may possibly be effective, and therefore could be considered in treating patients with PFCD[3]. On the other hand, European guidelines recommend their use in simple fistulas that do not respond to antibiotics and as maintenance therapy[11].

3.1.5. Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressive drug that inhibits IL-2 induced T cell mediated immune responses. Evidence supporting the use of tacrolimus in PFCD is based on a trial published in 2003. Sandborn et al. performed a multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 46 patients (43 had PFCD) were randomized to either tacrolimus or placebo for 10 weeks. Only 27 patients completed the 10-week study, however intention to treat analysis revealed fistula improvement was greater in patients treated with tacrolimus (43% versus 8% in placebo, p=0.01). Despite its effect on healing, there was no effect on fistula closure. Deleterious side effects were also more common in the tacrolimus group prompting the authors to encourage dose reduction in response to side effects when using tacrolimus to treat PFCD[39].

The ACG includes tacrolimus in their recommendations for PFCD, however, given its potential for toxicity, they suggest it be used only as a short-term therapy[3]. Conversely, European guidelines make no mention of the drug[11].

3.1.6. Cyclosporin

Data regarding the use of cyclosporin in PFCD is extremely limited. Perhaps the best-known study addressing its use in PFCD was published in 1994. Present et al. used intravenous cyclosporin to treat 16 patients who had failed traditional medical management; 88% had improvement with closure noted in 44%[40]. Relapse and side effects were common, and cyclosporin therapy is not mentioned in either American or European guidelines[3,11].

3.1.7. Certolizumab pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a pegylated Fab fragment of a humanized antibody to TNF. It was initially FDA approved in 2008, for use in patients failing standard therapy for CD. Data regarding the efficacy of Certolizumab in PFCD is derived from sub-analysis of two randomized controlled trials.

3.1.7.1. Efficacy of Certolizumab to induce a response—PRECISE 1

In 2007 Sandborn et al. examined the efficacy of certolizumab pegol to induce a response in 662 patients with moderate to severe CD. In this multicenter, placebo-controlled trial, 662 patients with moderate to severe CD were randomized to receive either certolizumab or placebo. At baseline, 107 patients (16%) had fistulas; fistula healing was studied as a secondary endpoint. At week 26 there was no difference in fistula healing (30% in the certolizumab group versus 31% in the placebo group)[41]. As with several studies mentioned above, the statistical power for fistula outcome measures is limited by the small number of patients with fistulas included in this study.

3.1.7.2. Efficacy of Certolizumab to maintain response—PRECISE 2

The same year, in a separate multicenter, placebo-controlled trial, 428 patients who had initial response to certolizumab at 6 weeks were randomized to receive maintenance therapy with certolizumab or placebo. Sub-group analysis on 58 patients (15%) who had fistulizing disease revealed that at week 26, 15 of 28 (54%) patients in the certolizumab group and 13 of 30 (43%) in the placebo group had fistula closure (no drainage with compression on consecutive visits three weeks apart). The authors comment that this study was not appropriately powered to assess the utility of certolizumab in achieving this endpoint[42]. Though the number of patients here is small, the magnitude of difference between treatment groups is also small, and this minimal difference, even after selecting for responders, was not encouraging.

In 2011, Schreiber et al. reported further on this sub-group analysis, stating that of the 58 patients described, most (91%) had perianal fistulas. They used more careful definitions of fistula closure, breaking it down into those that had at least 50% improvement and those that achieved 100% closure. At 26 weeks, more patients treated with certolizumab maintenance therapy had 100% fistula closure (36% versus 17%, p=0.038). However, a fistula response, as determined by at least 50% fistula closure at this time point was not significantly different between groups[43].

While the group was able to show a significant improvement in 100% fistula closure, this analysis was in a subset of a subset and included only 15 patients (4%) of 428, who had already been selected as responders among an initial 668 who were treated with certolizumab. When including all comers, overall response rate for patients with 100% closure at 26 weeks were 0.015% with certolizumab versus 0.007% with placebo. This study provides only very limited support for efficacy of certolizumab in fistulizing CD.

The evidence to support a role for certolizumab in treating PFCD is certainly not as robust as with other anti-TNF medications. ACG recommendations suggest considering certolizumab despite low evidence (perhaps based more on the knowledge that other ant-TNF drugs demonstrated more robust efficacy for this indication), while European guidelines do not remark on the drug[3,11].

3.1.8. Vedolizumab

Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets intestinal specific leukocyte trafficking by selectively binding to α2β7 integrin. It was FDA approved for moderate to severe CD in 2014.

3.1.8.1. Vedolizumab induction and maintenance—GEMINI 2

In 2013 Sandborn et al. reported on an integrated induction (368 patients randomized to vedolizumab versus placebo) and maintenance trial (461 responders to open label induction therapy were randomized to maintenance therapy with vedolizumab or placebo scheduled every 4 or 8 weeks). 165 of 1115 patients (14.8%) had draining fistulizing disease at baseline. The group found that in comparison to placebo, vedolizumab has greater capacity to induce remission in patients with CD who had failed other therapy (14.5% versus 6.8%, p=0.02). At 52 weeks, in the maintenance group receiving dosing every 8 weeks, fistula closure occurred in 41% of the vedolizumab group versus 11% in the placebo group (p=0.03). On the contrary, no difference was noted in the group receiving treatment every 4 weeks (p=0.32)[44].

In 2018 Feagan et al. describe a more formal, exploratory analysis of fistulizing disease in the same study. They report on fistula closure rates in 153 patients who had fistulizing disease on entering the maintenance period at 14 and 52 weeks. In this study, the authors combined data from the 4-week and 8-week groups in order to achieve greater power. Though differences did not reach statistical significance, a higher proportion of patients receiving vedolizumab maintenance therapy achieved fistula closure at week 52 (31% versus 11%, ARR 19%, CI −8.9 to 46.2). Still, vedolizumab treated patients did have significantly faster time to fistula closure (HR 2.54, CI 0.54–11.96)[45].

Though the data is not entirely convincing, the authors conclude that these data support efficacy of vedolizumab in treating fistulizing CD. Still, the use of vedolizumab is not included in formal guidelines for the treatment of PFCD[3,11]. Of note, the mechanism of action for vedolizumab is to prevent the α4β7 integrin dimer expressed on circulating lymphocytes from binding to MAdCAM-1 which is selectively expressed only in the vascular endothelium of the gastrointestinal tract. The vascular supply for the anal canal, to some degree the most distal rectum, arises from branches of the internal iliac arteries, which should express VCAM-1 but not MADCAM-1. Thus, in principle, vedolizumab would not be able to block lymphocyte trafficking to the very distal rectum and the anal canal. This theoretical concern deserves further exploration in translational medicine studies.

3.1.9. Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 to inhibit T cell activation and the ensuing inflammatory cascade. It is known for its effects in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and was FDA approved for use in CD in 2016.

Data regarding efficacy of ustekinumab in PFCD are limited by small patient numbers from retrospective cohorts and a secondary analysis of clinical trial data.

In 2016 a Spanish group published a retrospective multicenter open-label trial exploring the capacity of ustekinumab to affect a clinical response in patients with CD. Of 116 patients in the study, 18 had perianal disease; 11 (61%) improved clinically, however, 2 developed perianal disease while receiving ustekinumab[46]. A year later, Ma et al. reported on a similar retrospective study assessing clinical and endoscopic or radiographic response to ustekinumab in 167 patients with CD. In 45 patients (26.9%) with perianal fistulizing disease at the time of ustekinumab induction, 14 patients (31.1%) achieved complete healing as demonstrated by pelvic MRI or contrast-enhanced pelvic ultrasound[47].

In 2017, Sands et al. presented pooled data on subsets of patients with PFCD from major clinical trials investigating the efficacy of ustekinumab (UNITI-1, UNITI-2 and CERTIFI). Only 10.8 to 15.5% of patients had active PFCD. Complete healing occurred in 14.1% (10/71) of placebo treated patients and 24.7% (37/150) of patients on ustekinumab (p=0.073) at 8 weeks[48]. Despite heterogeneity in dosing among trials included, this study currently provides the most robust data in terms of patient numbers.

Low patient numbers and a lack of control groups for comparison in some studies make it difficult to interpret these data, however they do indicate that investing in further studies would be worthwhile.

3.1.10. Steroids and Aminosalicylates

Steroids are not effective in healing PFCD and may result in increased sepsis therefore they are not included in the treatment algorithm described here[10]. When necessary to control luminal disease, steroids may be used, however adequate drainage of perianal sepsis must first be assured[10].

Though they have not been specifically tested in PFCD, aminosalicylates have been shown to have no clinical benefit in luminal CD, and are not recommended for use in PFCD[49].

4. Surgical Management

Best outcomes are thought to result when medical and surgical management are combined.[50,51] A multidisciplinary approach to treatment of PFCD is associated with improved healing, decreased risk of relapse and increased time to relapse[51–54].

4.1. Abscess drainage

Though sub-centimeter abscesses may be too small to localize and may not require drainage, it is generally recommended that perianal abscesses are adequately drained prior to starting therapy[3,11]. The rationale for drainage prior to therapy is multifaceted. First, it allows for source control prior to exposing the patient to an immunosuppressed state, theoretically, preventing sepsis. Additionally, resolution of abscess associated inflammation is required for fistula healing. Adequate drainage is commonly accomplished with incision and drainage in combination with placement of a loose seton, when possible[3].

4.2. Seton drainage

A seton is commonly used as an adjunct to medical therapy as a means of providing adequate drainage of the fistula tract to prevent recurrent abscess formation and sepsis. In this context, a seton is generally understood to be a loose, non-cutting seton of silastic material[11]. Cutting setons should be avoided as they are thought to be associated with a moderate risk of incontinence[11]. A systematic review found average rate of any degree of incontinence after treatment of fistulas with cutting seton was 32%, with varying portions of patients reporting incontinence to flatus, liquid and stool (15%, 22% and 6%, respectively)[55]. Adequate drainage results in resolution of local infection and decrease in inflammation.

4.2.1. Efficacy of seton in combination with anti-TNF

Some data to suggest that seton placement in combination with anti-TNF results in superior fistula healing. In 2003 Regueiro et al. reported on 32 patients with PFCD undergoing anti-TNF therapy. In comparison to patients receiving infliximab alone, patients undergoing EUA prior to infliximab had improved response (100% vs 82.6%, p=0.014), less recurrence (44% vs 79%, p=0.001), and longer time to recurrence (13.5 months vs. 3.6 months)[52].

Geartner at al. later performed retrospective analysis of 226 patients with PFCD to investigate the inverse; they compared patients undergoing EUA alone (n=147) to those with EUA and infliximab (n=79) at mean follow up of 30 months. They found no difference in healing rates with the addition of infliximab[56]. However, there were significantly more patients undergoing fistulotomy in the operative treatment alone group and significantly more patients having setons placed in the combined group suggesting increased complexity of fistulas in the combination group, which might explain the lack of improvement with infliximab despite its known efficacy.

To help better elucidate the role of combined therapy in fistula closure, de Groof et al. attempted to perform meta-analysis comparing seton alone to combined seton and anti-TNF in the management of PFCD. They included four cohort studies with a total of 132 patients; 98 (74%) had combined treatment. Closure rates varied widely and there was limited data regarding seton removal. In all, two of the four studies showed significant improvement in response with combined therapy while two did not, leading the group to assert that variable data prevents arriving at a solid conclusion about optimal treatment. However, they do state that they prefer a combined approach with temporary seton drainage, immunomodulators and anti-TNF[50]. ACG guidelines similarly support a role improved healing of PFCD for seton placement in combination with anti-TNF[3].

4.2.2. Seton removal

Though reported responses are variable, a certain portion of patients will experience fistula closure after a seton is removed.[11] In a review of 10 studies de Groof at al found complete closure after seton removal varied from 13.6% to 100% and recurrence ranged from 0% to 83.3%.[50]

Timing of seton removal in relation to starting therapy with anti-TNF may have an effect on fistula healing, however this is not well defined. Some have cited a 15% abscess recurrence when seton removal was required 2 weeks after starting therapy with infliximab to support delaying removal until the end of induction therapy[19]. However, in a retrospective study, with longer duration of seton (median duration of 33 weeks), abscess recurrence was still 22%, suggesting that longer duration of seton does not prevent abscess recurrence[21]. Additionally, the group found that seton drainage for less than 34 weeks was associated with fistula healing. Yet another study suggests good success with removal after 5 doses of infliximab[57]. Clearly more directed studies will be needed to arrive at a definitive conclusion regarding optimal duration of seton placement.

For patients treated with anti-TNFs, ECCO-ECSP consensus suggests removal of seton after induction of therapy and resolution of proctitis, though this is regarded as level five evidence[11].

4.3. Surgical closure of fistula tracts

When considering surgical closure of fistulas in CD, it is imperative to assure there is no active proctitis or undrained perianal abscesses. Optimally, luminal disease would also be well controlled (See Figure 1).

4.3.1. Simple fistulotomy

Among patients with PFCD, fistula healing is known to be highest in patients undergoing primary fistulotomy (72–100%)[58]. However, this procedure can be associated with a significant rate of incontinence, especially in patients with CD, who commonly have multiple perianal lesions and concurrent scarring. As such, fistulotomy in this population must be performed relatively infrequently, and with prudence. One study examining outcomes of fistulotomy in PFCD found that fistulotomy in CD resulted in 61% of patients reporting fecal soiling[59]. To minimize this detrimental complication, guidelines recommend fistulotomy may only be considered in patients with very low, simple, subcutaneous or superficial fistulas with no mucosal involvement[3,11]. Further, some evidence suggests that initial management with a seton may offer improved healing in comparison to immediate fistulotomy[51].

4.3.2. Advancement Flap

In 1998 Wexner et al. describe outcomes for 31 patients with PFCD who had endorectal advancement flaps. The majority were rectovaginal fistulas, though perianal fistulas accounted for approximately 25%. Mean follow-up was 17 months. 2 (6.5%). Fistula healing was achieved in 71% of cases and was less common in patients with small bowel disease (p<0.05)[60]. The same year Fazio et al. described a series of 13 patients undergoing advancement flap for PFCD, with a healing rate of 62% at one year. Patients who failed either required proctectomy or had recurrence of a rectovaginal fistula. The authors concluded that endorectal advancement flap offered a rational approach in patients without proctitis or if patients would otherwise require proctectomy[61].

In 2010 Soltani et al. reviewed the literature, finding 35 low quality studies of 1654 patients undergoing endorectal advancement flaps for PFCD; patients with rectovaginal and recto-urinary fistulas were then excluded. They described a healing rate of 64%[62]. A similar systematic review published in 2017 cited initial healing rates of 50–85% with 1 year recurrence rates 30–50%[58].

4.3.3. Fistula Plug

Tissue plugs are designed with the intent to create a scaffolding for ingrowth of healthy tissue.

Two existing systematic reviews investigate the value of fistula plugs in PFCD. The first, published in 2012 found the success rate of plugs in non-CD related fistulas was similar to that of CD related fistulas, however, the authors concluded that this data was not reliable since the fistula plug had not been adequately tested in Crohn’s patients[63]. A second group reviewed the literature and came to a similar conclusion in 2016[64]. However, that same year, a 54 patients were randomized to seton removal versus fistula plug in a multi-center, open-label trial. At week 12 fistula closure was similar between groups (31.5% in patients treated with fistula plug versus 23.1% in patients with removal of seton alone [RR 1.31, CI 0.59–4.02, p=0.19])[65].

Data supporting the utility of fistula plugs in Crohn’s disease are inadequate, however available studies indicate no clear benefit of plugs in comparison to seton removal alone.

4.3.4. Fibrin glue

When treating perianal fistulas with fibrin glue, granulation tissue is debrided from the fistula tract, the internal opening is closed with a suture, and fibrin glue is instilled into the tract. The external opening is then closed, sealing the newly formed fibrin clot into the tract. Ensuing fibrinolysis stimulates tissue healing and, ideally, closure of the fistula tract.

Though it is commonly regarded as a marginal technique to prompt fistula healing, fibrin glue can be an appealing approach because using it is technically simple, has minimal effects on continence, and allows for preservation of the anatomy in case future repairs might be necessary.

In 2002 Lindsey et al. described results from a small randomized trial comparing fibrin glue to conventional treatment (loose seton with or without advancement flap) in 16 patients with complex perianal fistulas. More patients had fistula healing with fibrin glue than conventional treatment (69% versus 13%, CI25.9–86.1, p=0.003), however only a portion of these patients had CD.[66]

In 2010 Grimaud et al. reported on results from a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial of 77 patients with PFCD randomized to either fibrin glue versus observation. At 8 weeks post treatment, healing was more likely in the group treated with fibrin glue in comparison to those undergoing observation (38% versus 16%, OR 3.2, CI 1.1–9.8, p=0.04). However, this benefit was greater in patients with simple fistulas[67].

In his systematic review, Lee et al. reported initial healing rates of 40–67%. though this is likely a misrepresentation, since the studies included were neither specific to CD, nor complex fistulas[58]. While healing rates may be inferior to other treatments, advocates of fibrin glue would argue: “It doesn’t hurt to try.”

4.3.5. Local Stem Cell Therapy—Mesenchymal Stem Cells

As noted above, best medical therapy, in combination with traditional surgical approaches results in durable fistula healing in just more than 50% of patients[21,56]. The deleterious effects of fistulas on quality of life in patients with CD, have led many to seek alternative strategies that might improve healing rates. In recent years mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy has drawn interest from many fields wishing to exploit the capacity of these cells to modulate inflammatory processes and regenerate tissues[68].

MSCs are multipotent cells; regardless of their origin, they are capable of differentiating into bone, muscle, adipose, and other connective tissues depending on stimulus from surrounding environments. MSCs exist in small populations within connective tissues such as bone marrow and adipose tissue. The ease of harvesting and culturing these cells has made them an attractive focus for therapeutic investigations and they have proven beneficial in modifying disease processes in a number of inflammatory conditions[69,70]. Several trials have confirmed the safety and efficacy of these cells in treating perianal fistulas in CD[71–74].

In 2005 Garcia-Olmo et al. published results from a phase I trial demonstrating 75% healing and no adverse effects in 8 patients receiving adipose derived stem cell transplants for the treatment of their fistulas[71]. Four years later the same group reported results from a phase II trial in which 14 of 49 patients (29%) had complex perianal fistulas secondary to CD. Patients were randomized to treatment with local injection of fibrin glue or local injection with a mixture of fibrin glue and MSCs. Healing in CD was comparable to healing in patients without CD and the addition of MSC to fibrin glue was beneficial to healing (RR for healing 4.43, CI 1.7–11.3, p<0.001)[72].

In 2016 Panes et al. then reported on a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of MSC injection patients with complex PFCD (Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Induction of Remission in Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease—ADMIRE-CD). Patients in Europe were randomized to intralesional injection with MSCs versus saline. At 24 weeks healing was seen in 50% of patients receiving MSCs versus 34% of controls (p=0.024)[73]. In 2018 the group then published results for 52-week follow-up. Results were similar, with healing noted in 56.3% in patients who had MSCs versus 38.6% in controls (p=0.01)[74]. This therapy was approved in Europe (CMARK designation) based on this trial, and a second placebo-controlled trial is currently underway (NCT03279081).

In a systematic review of studies investigating the use of MSCs in PFCD, Lightner et al. identified 3 trials appropriate for inclusion in meta-analysis. Meta-analysis revealed improved healing with MSCs as compared to controls at 6–24 weeks (OR 3.06, CI 1.05–8.9, p=0.04), but not later, at 24–52 weeks (OR 2.37, CI 0.9–6.25, p=0.08). In the studies examined, MSCs were delivered in a variety of manners: direct injection, mixed with fibrin glue, and impregnated in a fistula plug. The authors noted that healing rates were higher when MSCs were delivered on a carrier such as glue or a plug[75].

Initial reports using MSCs have thus appeared promising. Future studies investigating optimal methods for harvest and delivery, as well as a means of making this technique more widely available will be important. For a more in depth review of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in PFCD please refer references Bermejo et. al., Bor et. al. and Dailey et. al. [76–78].

4.3.6. Ligation of intra-sphincteric fistula tract—LIFT

The goal of the LIFT procedure is to identify the fistula in the plane between the internal and external anal sphincters, then to debride and ligate the tract.

Though promising, data regarding the application of this technique in PFCD is limited to two retrospective studies emerging from a single institution. The first report of 15 patients undergoing the LIFT procedure for PFCD was published in 2014. 12-month follow-up data were available for only 12 of the 15 patients, however among them, 67% maintained healing[79]. Over the ensuing years, the group expanded their cohort to 23 patients with a median follow-up to 23 months. They reported 48% fistula healing. Recurrence was most often within the first year (75%) and occurred more commonly in patients with colonic disease in comparison with small bowel disease (p=0.02)[80].

Clearly there is limited data available for this technique, and certainly no valid comparison for LIFT versus other surgical techniques, however, rates of healing in the above reports appear comparable to other methods, therefore this practice seems to be a reasonable approach.

4.3.7. Local Injection of anti-TNF

Local injection of anti-TNF therapy was explored as a means of sparing the systemic side effects associated with anti-TNF therapy (i.e. infusion reactions, antibody formation, immunosuppression and malignancy). A systematic review of six pilot studies included a total of 92 patients with PFCD who had anti-TNF medication injected into or around perianal fistulas. Outcomes for these patients were most commonly reported as ‘complete or partial response’ to therapy, which ranged from 40 to 100%[81]. The low numbers of patients included in available studies, variation in reported response, and heterogeneity among studies makes it difficult to arrive at a meaningful conclusion regarding the efficacy of anti-TNF therapy delivered locally in PFCD.

4.3.8. Video assisted anal fistula treatment—VAAFT

VAAFT is a sphincter sparing approach whereby a fistuloscope is inserted into the external opening, and all tracts and side tracts are visualized directly, as well as direct visualization of the internal opening. After fistuloscopy the tract is then cauterized every centimeter in order to obliterate the tract. After the area is irrigated, the internal opening is closed.

In a study of 11 Crohn’s patients with complex fistulas who had VAAFT completed, Schwander et al. reported a success rate of 82% at 9 months. Additionally, VAAFT identified otherwise undetectable side tracts in 64% of patients and did not affect continence[82].

A second report using this technique in symptomatic Crohn’s perianal fistulas was published in 2018. Adegbola et al. describe quality of life survey results from 21 of 25 patients with Crohn’s related perianal fistulas who underwent VAAFT. 84% showed significant improvement in pain and discharge, 81% believed VAAFT was the correct approach and no one regretted having undergone the procedure[83].

These data are limited in both patient numbers and in follow-up. However, preliminarily, they indicate that VAFFT may have a place among already existing surgical options for treating patients with PFCD. More studies will be necessary before recommendations can be made about the procedure. Additionally, challenges regarding cost of equipment and procedure learning curves may hinder widespread uptake of the technique.

4.3.9. Fistula laser closing—FiLaC

Fistula closure using FiLaC depends upon destruction of the epithelialized tract using energy. In FiLaC, the energy source is a laser, and tract destruction is performed blindly. However, in principal the two techniques are analogous. Occasionally the technique is combined with endorectal advancement flap.

In a study published in 2017, Willhelm et al. described outcomes after FiLaC in 117 patients, 13 (11%) with CD. Median follow-up was 25.54 months. The primary and secondary healing rate in Crohn’s patients was 69.2% and 92.3%, respectively[84].

Perhaps even more so than as with VAAFT, uptake of FiLaC is in its infancy and more data must be collected. Similar to VAAFT, FiLaC is associated with increased equipment costs. Learning curve might be less for FiLaC, but at the expense of the ability to identify internal side tracts.

4.3.10. Diversion and proctectomy

Diversion or proctectomy should be considered when achieving quiescence of perianal fistulizing disease and proctitis is not possible despite maximal medical therapy[11]. Among patients with PFCD temporary fecal diversion and permanent ostomy may become necessary in approximately 50% and 30% of patients, respectively[85]. Many patients request temporary diversion due to an aversion for life long stoma, however, few undergoing this procedure go on to have successful re-establishment of bowel continuity. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Singh et al. found that temporary diversion accomplished disease control in 64% of patients, however only 17% underwent successful restoration of bowel continuity[86].

5. Conclusion:

Current management of PFCD relies upon combined medical and surgical approaches. More than anything, this review highlights the insufficient quality of data with regard to both medical and surgical practices. Level I evidence for medical therapy of fistulizing CD exists only for infliximab. Similarly, level I evidence for surgical interventions in PFCD exists only for MSC injection, a procedure that has recently been introduced, and is not widely available (See Table 4). With both fields advancing rapidly, it will be important to gather data efficiently and apply newly acquired data effectively. This will require enhanced medical and surgical collaboration and more well-defined outcomes, as well as standardized tools and timepoints for measuring these outcomes.

Table 4.

Level of evidence and healing rates associated with surgical interventions.

| Surgical Intervention | Level of Evidence | Healing Rates |

|---|---|---|

| Seton | 4 | 14-81% |

| Fistulotomy | 4 | 72-100% |

| Advancement flap | 4 | 50-85% |

| Fistula plug | 1b | 15-86% |

| Fibrin Glue | 1b | 40-67% |

| Local stem cell therapy | 1a | 29-79% |

| FiLaC | 4 | 69-92% |

| LIFT | 4 | 48% |

| Local anti-TNF injection | 4 | 40-100% |

| VAAFT | 4 | 8% |

| Diversion | 3a | 18-83% |

Adapted from [58].

6. Expert Opinion:

Key weakness in clinical management of PFCD have their origins in an incomplete understanding of the biology underlying PFCD, and in CD, more generally. The pathogenesis of perianal fistulas in CD is broadly understood to result from mucosal ulceration, activation of inflammatory pathways and persistence of local inflammation, which can then be exacerbated by infection. However, the best methods for preventing or interrupting this cascade of events are poorly understood. Therefore, disease recurrence remains high despite advances in therapies and best attempts at management.

Research regarding the genetic and environmental factors, as well as their interactions with available therapies will be important in identifying characteristics of responders and non-responders. With growing information in these areas, we may look forward to developing more personalized treatment plans.

Increased knowledge of inflammatory pathways and new mechanisms for interrupting them will continue to encourage the interest of dedicated researchers. Ideally, a precise and complete understanding of the biologic pathways would enable disease management without need for surgical intervention. Until then, the focus will be on optimizing dosing, timing, and monitoring of both medical and surgical management to give patients the best outcomes, allowing for improved quality of life.

To this end, recent advances in treating PFCD with MSCs are promising. We eagerly await results from the ADMIRE-CD II trial, which has potential to lead to FDA approval for this local MSC therapy. If this should be successful, we will need to make steps to overcome logistic challenges in administering this therapy; for trial purposes, the cells must be ordered several weeks ahead of time, transported from a single production site in Spain and used within 24 hours of its dispatch. It will be necessary to simplify this process and identify means by which to improve cell stability over time. Additional studies confirming whether alternative cell carriers, such as glues or plugs might increase the efficacy will also be valuable.

Further, it would be of great interest to define the full spectrum of patients who might benefit from local MSC therapy. Inclusion criteria for the ADMIRE-CD studies are relatively stringent and the patients with the most severe disease accompanied by proctitis have been excluded. However, these patients might stand to benefit the most from protection of the sphincter complex with this novel local therapy. It will be exciting to explore the utility of MSC therapy in these types of patients.

Finally, one of the largest challenges in deriving meaningful and compatible results from multicenter trials is a relative lack of infrastructure on both national and international levels. In perianal fistulizing CD there are no universally accepted means by which to interpret outcomes. Recent efforts, such as those put forth by ENiGMA collaborators, to standardize outcome measures in perianal fistulas represent the kind of efforts necessary to make outcomes more readily interpreted and compared[87]. However, in addition to establishing such measures, there must be international buy-in to adopt such a system, where results can be understood interchangeably.

In five years, new biologic therapies will undoubtedly become available. A phase II trial investigating the role of the JAK 1 inhibitor, Filogotinib, will conclude in 2020 and other novel therapies will likely be introduced for investigations. Similarly, new combinations of therapy may offer novel approaches. Case reports of patients with unremitting perianal disease have demonstrated significant response to dual biologic therapy[88]. It will be interesting to note whether, and how we might pursue investigating the effect of dual biologic therapy on outcomes.

From a surgical standpoint, innumerable studies currently investigating the efficacy of MSCs will indisputably improve our clinical applications of this intervention. Even before these data are mature, others are moving on to identifying new ways to deliver the active factors present in stem cells through such techniques as extracellular vesicles.

On a more concrete level, results from the multimodal treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: seton versus anti-TNF versus advancement plasty (PISA) study, will become available, giving us the first randomized data regarding the efficacy of currently accepted treatment strategies for PFCD, and enabling head to head comparison of outcomes with these approaches[89].

Article Highlights.

Perianal Crohn’s disease is a pervasive problem with deleterious effects on patients’ quality of life

Despite major advances in therapy, treating perianal Crohn’s disease remains a significant challenge

Close collaboration between gastroenterologists and surgeons in research and clinical realms will enable improved approximations of best practices

Advanced understandings of interactions between genetics, environmental factors and therapeutic factors will enable more targeted approaches

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was funded by grants from the US National Institutes of Health / National Library of Medicine, grant: T15LM011271

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

W.J. Sandborn has received research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos; has received consulting fees from Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Janssen, Lilly, Miraca Life Sciences, Nivalis Therapeutics, Novartis Nutrition Science Partners, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Paul Hastings, Pfizer, Precision IBD, Progenity, Prometheus Laboratories, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials (owned by Health Academic Research Trust or HART), Salix, Shire, Seres Therapeutics, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Takeda, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Vivelix; and owns stock options in Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Oppilan Pharma, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Precision IBD, Progenity.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

- 1.Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci, 58(2), 519–525 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molendijk I, Nuij VJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, van der Woude CJ Disappointing durable remission rates in complex Crohn’s disease fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 20(11), 2022–2028 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol, 113(4), 481–517 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eglinton TW, Barclay ML, Gearry RB, Frizelle FA. The spectrum of perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Dis Colon Rectum, 55(7), 773–777 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr., Tremaine WJ et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology, 122(4), 875–880 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loffler T, Welsch T, Muhl S, Hinz U, Schmidt J, Kienle P. Long-term success rate after surgical treatment of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis, 24(5), 521–526 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology, 130(3), 650–656 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Wilkinson K, Cohen RC, Kamm MA. The clinical course of fistulating Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 17(9), 1145–1151 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pittet V, Juillerat P, Michetti P et al. Appropriateness of therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease: findings from a national inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 32(8), 1007–1016 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA et al. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut, 63(9), 1381–1392 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bemelman WA, Warusavitarne J, Sampietro GM et al. ECCO-ESCP Consensus on Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis, 12(1), 1–16 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Starlinger M. Clinical course of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Gut, 37(5), 696–701 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice C. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology, 125(5), 1508–1530 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, Rodriguez-de-Santiago E, Lopez-Sanroman A. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol, 30(1), 33–44 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsui JJ, Huynh HQ. Is top-down therapy a more effective alternative to conventional step-up therapy for Crohn’s disease? Ann Gastroenterol, 31(4), 413–424 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Deventer SJ. Tumour necrosis factor and Crohn’s disease. Gut, 40(4), 443–448 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowers Y, Allez M. Efficacy of anti-TNF in Crohn’s disease: how does it work? Curr Drug Targets, 11(2), 138–142 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.*.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med, 340(18), 1398–1405 (1999).Landmark paper demonstrating significant improvement in acheiveing steroid-free clinical remission in patients treated with either infliximab monotherapy or combination therapy with infliximab plus azathioprine over azathioprine monotherapy.

- 19.*.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med, 350(9), 876–885 (2004).Important study showing the efficacy of infliximab in maintaining clinical remission in patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease.

- 20.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med, 362(15), 1383–1395 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Gizard E et al. Long-term outcome of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 11(8), 975–981 e971–974 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West RL, van der Woude CJ, Hansen BE et al. Clinical and endosonographic effect of ciprofloxacin on the treatment of perianal fistulae in Crohn’s disease with infliximab: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 20(11–12), 1329–1336 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz DA, Ghazi LJ, Regueiro M. Guidelines for medical treatment of Crohn’s perianal fistulas: critical evaluation of therapeutic trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 21(4), 737–752 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dewint P, Hansen BE, Verhey E et al. Adalimumab combined with ciprofloxacin is superior to adalimumab monotherapy in perianal fistula closure in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial (ADAFI). Gut, 63(2), 292–299 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ et al. Higher infliximab trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 45(7), 933–940 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Matary W, Walters TD, Huynh HQ et al. Higher Postinduction Infliximab Serum Trough Levels Are Associated With Healing of Fistulizing Perianal Crohn’s Disease in Children. Inflamm Bowel Dis, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidov Y, Ungar B, Bar-Yoseph H et al. Association of Induction Infliximab Levels With Clinical Response in Perianal Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis, 11(5), 549–555 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology, 130(2), 323–333; quiz 591 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med, 146(12), 829–838 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]