Abstract

Infection with helminth parasites poses a significant challenge to the mammalian immune system. The Type 2 immune response to helminth infection is critical in limiting worm-induced tissue damage and expelling parasites. Conversely, aberrant Type 2 inflammation can cause debilitating allergic disease. Recent studies have revealed that key Type 2 inflammation-associated immune and epithelial cell types respond to Notch signaling, broadly regulating gene expression programs in cell development and function. Here, we discuss new advances demonstrating that Notch is active in the development, recruitment, localization, and cytokine production of immune and epithelial effector cells during Type 2 inflammation. Understanding how Notch signaling controls Type 2 inflammatory processes could inform the development of Notch pathway modulators to treat helminth infections and allergies.

The multi-faceted mechanisms of Type 2 immune activation

Multicellular eukaryotic helminth parasites afflict over a billion humans worldwide [1,2]. Soil-transmitted intestinal helminths, including Trichuris trichiura, Ascaris lumbricoides and Ancylostoma species, water-borne Schistosoma trematodes, and filarial parasites such as Brugia malayi, cause significant morbidity and economic loss [3]. Current anthelminthic drugs have variable efficacy, treated patients frequently become re-infected, and there are currently no effective vaccines to prevent infection in humans [4]. Thus, a better understanding of the immune mechanisms that mediate natural host protection against helminths is required to develop better treatments and vaccines to limit infection-associated pathology.

Type 2 inflammation is associated with infection with parasitic helminths. This host response can drive tissue repair of worm-induced damage and elimination or sequestration of worms and parasite products. Innate immune effector cells cooperate [5,6] to promote activation of CD4+ T helper 2 (Th2) cells and humoral responses [7]. Dendritic cells (DCs) educate Th2 cells in the lymph node (LN), eliciting production of antigen-specific Type 2 cytokines, including interleukins (IL)-4, 5, 9 and 13 [8]. Mammalian Th2 responses in tissues are supported by group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) [9], basophils [10], and mast cells [5]. Type 2 cytokines produced by innate and adaptive cells also drive the polarization of alternatively-activated macrophages and eosinophil activation [11]; together, they facilitate wound repair and granuloma formation to enclose toxic helminth products [1]. Type 2 cytokines also act directly on epithelial cells in tissues, promoting increased cell turnover, mucus production, and production of anti-helminth proteins [12]. Collectively, these mechanisms are also a hallmark of debilitating inappropriate allergic inflammation in response to environmental substances such as food allergens, pollen and house dust mite (HDM) allergens that causes significant morbidity [13]. Thus, Type 2 inflammation during helminth infection and allergy has important implications for public health. Research efforts aimed at dissecting the mechanisms that control Type 2 inflammation could inform the development of new putative drugs or vaccines to manage these diseases.

While cytokines, bioactive lipids, and other factors can promote or restrain Type 2 inflammation, recent literature has highlighted the importance of the Notch receptor-ligand pathway in regulating Type 2 responses. Notch was originally identified for its functions in embryogenesis, but it also plays a role in organismal homeostasis, regulating epithelial cell differentiation and hematopoiesis; moreover, it contributes to the pathogenesis of human diseases, including hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and certain cancers [14]. In the past decade, Notch has been identified as a key regulator of developmental and functional gene expression programs in immune cells [15]. In this review, we discuss recent advances describing how Notch signals orchestrate Type 2 inflammation. We also highlight opportunities to therapeutically fine-tune Notch-dependent effector functions during Type 2 inflammation to treat helminth infections and allergies, and pose key questions in the field.

Notch, a key pathway for Type 2 immune mechanisms

Notch is a ubiquitous receptor-ligand signaling pathway that controls gene expression programs in many contexts, including mammalian immune activation (Box 1 and Figure 1). Catastrophic tissue damage can occur during helminth infection, for example in Schistosoma mansoni infection (schistosomiasis), in which transit of parasite eggs through tissues causes damage, fibrosis, vascular remodeling and organ dysfunction [16]. This potential for severe damage demands that host tissue-protective gene expression changes be rapid, broad-sweeping and highly organized. Notch-mediated modulation of global gene expression programs is therefore a potentially effective mechanism to elicit such changes [17]. Also, Notch-mediated cell-cell signals allow for rapid alteration of gene expression on a local scale [18], with studies employing cell lines that express luciferase reporters for Notch signaling demonstrating rapid transduction of Notch-mediated signals from the cytoplasm to the nucleus [17]. Thus, Notch can directly modulate effector cell responses in helminth-infected tissues without involving peripheral lymphoid tissues or systemic processes. Finally, as Notch signaling requires intimate cell-cell interactions [14], this mechanism could also play a role in the spatial organization of Type 2 responses in complex tissues such as the intestine.

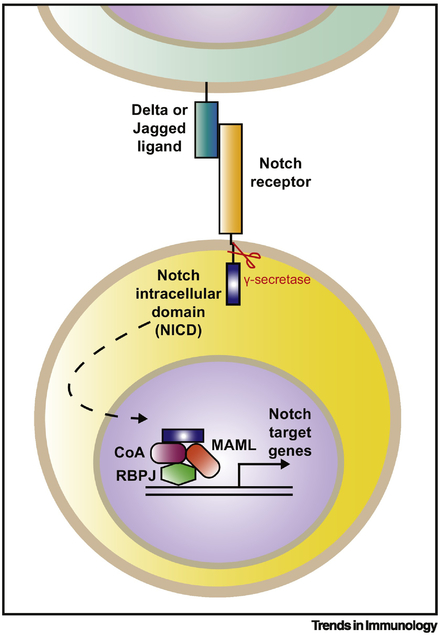

Box 1. The Notch signaling pathway.

The Notch signaling pathway is a critical mechanism of cell-cell communication that is highly conserved, from Drosophila to worms and all mammals [102]. It is active in many cellular processes, including embryogenesis, cell lineage specification, apoptosis, and immune activation. There are 4 receptors and a similar number of ligands that participate in sensitive and dynamic receptor-ligand interactions, influencing downstream gene expression changes at a single cell level [102]. The Notch signaling machinery is expressed by a multitude of cell types, immune as well as non-immune.

Notch signaling requires accessory enzymes for activation, and is modulated by post-translational modifications [18]. It involves rapid conversion of a cell surface receptor into an intracellular signaling molecule that promotes changes in gene transcription. Ligation of a Notch receptor (Notch1–4) by a Notch ligand (Jagged 1 or 2, or Delta-like ligands (Dll) 1, 3 or 4) leads to cleavage of the intracellular domain of the receptor (NICD) by γ secretase enzymes, allowing the translocation of the NICD to the nucleus [18]. The NICD then forms a complex with accessory proteins and coactivators, together with Mastermind-like protein (MAML), and the transcription factor RBPJ (also called CSL). This complex binds to Notch target sites across the genome, rapidly altering gene transcription [15] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Notch receptor activation drives rapid transcription of Notch target genes.

Ligation of a mammalian Notch receptor (Notch 1–4) by a Notch ligand (Delta/Jagged) on the cell surface (various cell types) leads to intracellular cleavage of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) by a γ secretase enzyme. The NICD then translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a transcription-activating complex composed of the transcription factor Rbpj (also known as CSL in humans), various accessory proteins and co-activators (CoA) and Mastermind-like (MAML) proteins. This complex binds to Notch target sites across the genome to induce transcription of Notch target genes.

Notch signaling intersects with other pathways, including intracellular signaling pathways and cytokine, hormone, and lipid signaling [19]; thus, Notch-responsive cells integrate a number of signals. This fact is particularly relevant in the context of murine models of helminth-induced Type 2 inflammation, in which immune effector cells in the tissue are exposed to an array of signals, including alarmins and cytokines such as IL-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), released by dying and/or damaged epithelial cells [19]. Here, we discuss how Notch signaling can control the gene expression programs and functions of Type 2 immune effector and epithelial cells, as well as how the combined effects of Notch signaling on these diverse cells influence the dynamic Type 2 inflammatory environment.

ILC2s: At the forefront of helminth-induced damage detection

Like other innate lymphoid cell (ILC) types, ILC2s are innate sentinels found at mucosal and lymphoid tissues in humans and mice [9]. While ILC2s are rare compared to Th2 cells -- their adaptive counterparts, they are potent Type 2 cytokine producers [20]. ILC2s, unlike Th2 cells, are not activated by antigens, but respond to epithelial- and tissue-derived factors, including IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP, leading to rapid Type 2 cytokine production at sites of inflammation and in the draining lymph nodes (dLN) in mouse models [21,22]. Recent studies have highlighted critical ILC2 responses that drive Type 2 inflammation and which are also regulated by the Notch pathway.

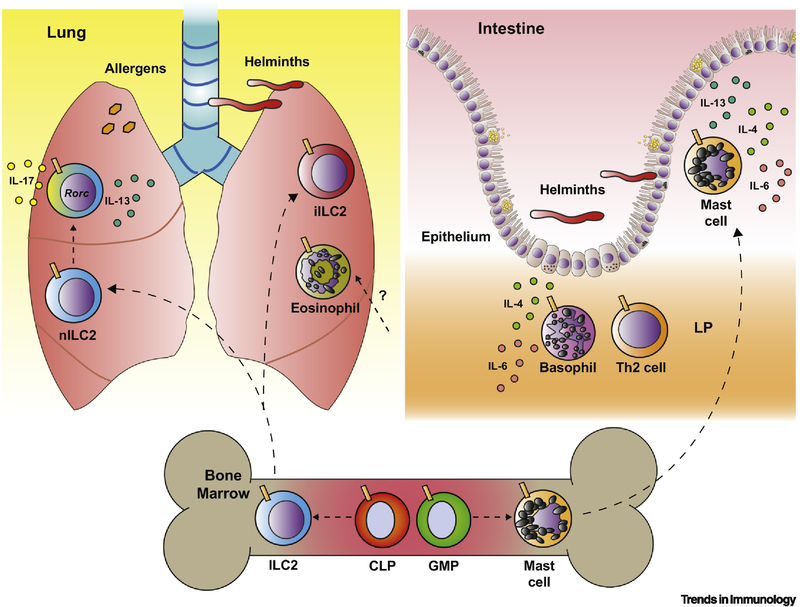

Early studies suggested that Notch could induce ILC2 differentiation in vitro [23], with the strength of Notch1 signals instructing ILC2 lineage specification in human thymic progenitors in vitro [24]. In mice, inhibition of pan-Notch signaling in bone marrow (BM) LSK cells via retroviral transduction with a genetically-encoded dominant-negative form of the adaptor molecule Mastermind-like (MAML) (DNMAML, [25] (Box 1)) limited ILC2 development from LSK cells following in vivo transfer [26]. Following intranasal papain exposure, or during infection with the rodent hookworm-like parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, transferred DNMAML-expressing BM ILC precursors failed to generate normal ILC2 numbers in irradiated recipients, with Notch acting upstream of the transcription factor Tcf-1 to promote ILC2 development [26].

Another study demonstrated that once murine ILC2s enter the periphery, heterogeneous ILC2 subsets emerge, with tissue-resident natural (nILC2s) and inflammatory (iILC2s) subsets accumulating in the lung during pulmonary inflammation in response to N. brasiliensis infection [27]. Murine iILC2s preferentially respond to IL-25 rather than IL-33, while the converse may be true for nILC2s. Murine iILC2s express KLRG1 and are functionally plastic, co-expressing the typical ILC2 product IL-13, as well as IL-17 [27] -- thought to be predominantly expressed by ILC3 [9]. Recent studies have shown that Notch plays a role in regulating these heterogeneous ILC2 populations. Specifically, in a murine model of Type 2 airway inflammation driven by IL-25 treatment, co-administration of IL-25 and the Notch-inhibiting gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI) compound E, resulted in decreased iILC2 lung accumulation in vivo compared to administration of IL-25 alone, indicating that Notch was required for pulmonary iILC2 accumulation [28]. Furthermore, exposure of murine nILC2s to Notch ligands in vitro promoted expression of Rorc, encoding a master transcription factor for ILC3 differentiation, and co-production of IL-13 and IL-17; this suggested that Notch could act as a key regulator of ILC2 functional plasticity [28]. Notch-mediated ILC2 functional plasticity might be physiologically significant in the murine lung, since IL-17 production during Type 2 immunity can result in increased neutrophilia and tissue damage [29]. Indeed, during murine lung inflammation elicited by IL-25 and HDM exposure, administration of blocking anti-Notch1/Notch2 antibodies compared to isotype control antibody resulted in reduced iILC2s co-production of IL-13 and IL-17 and reduced neutrophilia in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) [28].

Notch signaling can also regulate murine lung ILC2 responses indirectly by affecting cell types that suppress inflammation, namely, T regulatory (Treg) cells. For example, during murine respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, treatment with an anti-delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) antibody (to block the Notch ligand, Dll4), relative to treatment with an isotype control antibody, resulted in increased ILC2 accumulation in lungs and dLN and elevated production of IL-5, IL-13 and IL-17 from in vitro RSV-restimulated mouse mediastinal LN cells [30]. This phenotype was associated with decreased Treg cell accumulation in the dLN and acquisition of Th17-like properties by Treg cells [30]. Together, these studies suggested that Notch could directly and indirectly control ILC2 development, and function in homeostasis, as well as in Type 2 inflammation in mice. Whether Notch is an essential signal for ILC2 plasticity and whether Notch preferentially controls the development or recruitment of iILC2s relative to nILC2s remains unclear and warrants robust investigation. Moreover, it is worth noting that the critical Notch target genes that can influence ILC2 phenotype and function remain to be identified in both mice and humans.

Dendritic cells: The influence of Notch on Th2 priming

In mammals, DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that sample antigen in tissues, migrate to dLNs, and present antigen to CD4+ T cells, providing costimulation and other polarizing signals to drive priming of specific T cell fates [8,31]. Even before DCs were identified as key inducers of Th2 cell priming [32,33], DC expression of Notch ligands was known to influence Th2 differentiation of murine CD4+ T cells [34] (Fig. 2). Specifically, mouse splenic CD11c+ cells [35] and GM-CSF-elicited BMDCs (GMDCs) [34] were found to express a variety of Notch ligands. Seminal work showed that GMDCs upregulated the expression of Delta-like ligand genes in conditions that promoted Th1 priming (in vitro stimulation with the TLR ligand, lipopolysaccharide), but upregulated expression of Jagged genes in conditions that promoted Th2 priming (exposure to cholera toxin or prostaglandin E2) [34].

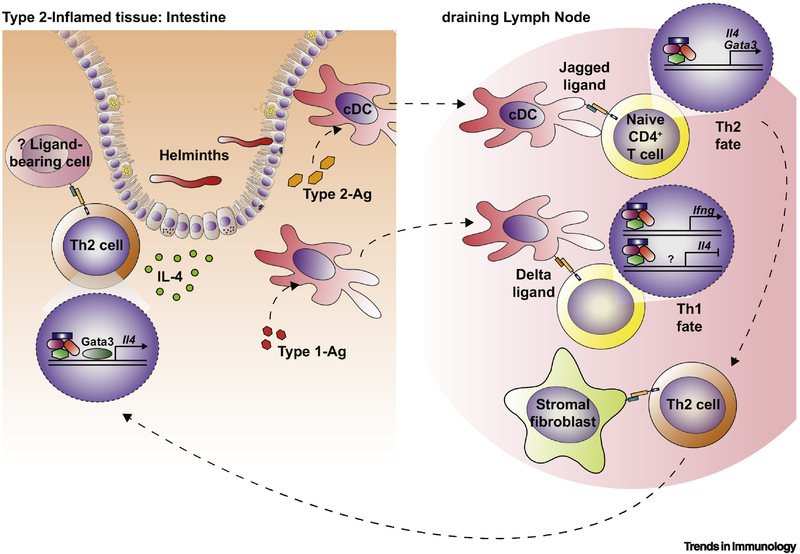

Figure 2. The role of the Notch pathway in human and mouse Th2 cell development and function.

Notch signaling plays a role in T helper type 2 (Th2) cell polarization and maintenance by affecting a variety of processes during Type 2 inflammation. Conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) in mucosal tissue are exposed to antigens during Type 2 inflammation, in this case, helminth infection in the intestine. This includes Type 2-associated antigens (Type 2-Ag), including helminth Ag, and those that induce Type 1 responses (Type 1-Ag), such as those from bacteria or viral species. Type 2-Ag and Type 1-Ag drive upregulation of Jagged and Delta ligands on cDCs, respectively. cDCs traffic to the draining lymph node (dLN) and interact with naïve CD4+ T cells. Jagged upregulation on cDCs may support a Th2 cell fate by activating Gata3 and Il4 expression downstream of Notch. Delta ligands expressed by cDCs may inhibit Th2 priming and induce a Th1 cell fate by inhibiting Il4 expression and driving Ifng induction. Notch ligands are also expressed in the dLN by non-hematopoietic cells, including structural cell populations such as stromal fibroblasts. Exposure to Notch ligands on these cells may drive expression of functional genes and induce migration to inflamed tissue. Further exposure to Notch ligands in the periphery or inflamed tissue (such as the intestine) may also help to maintain a Th2 cell fate by promoting continued Gata3 and Il4 expression [54]. The exact location and ligand-bearing cell(s) in this interaction are not known. Notch ligands can regulate T cell survival and apoptosis, while also influencing the development and function of Tregs (not depicted), which have the potential to limit Type 2 activation to resolve inflammation [30].

Subsequent studies have further dissected how DC expression of Notch ligands could influence Th2 cell priming and function. For example, compared to ovalbumin (OVA)-pulsed GMDCs transduced with empty retroviral vector, OVA-pulsed GMDCs transduced with vectors driving Dll1 and Dll4 over-expression inhibited IL-4 production and promoted IFNγ production from OVA-specific OTII mouse T cells in vitro [36]. Moreover, in a mouse model of OVA-driven allergic airway disease, adoptive transfer of OVA-primed GMDCs subjected to small-interfering RNA-mediated Jag1 knock-down, compared to transfer of GMDCs with intact Jag1 expression, resulted in decreased allergic disease following OVA challenge [37]. Another study showed that intranasal HDM treatment of mice was associated with increased Jag1 expression by CD11b+ conventional DCs (cDCs) in the mediastinal LN relative to controls [38]. Furthermore, HDM-pulsed, transferred GMDCs from Jag1/Jag2-floxed Cd11cCre mice, lacking Jag½ expression in CD11c+ myeloid cells, did not promote allergic airway inflammation in the BAL following HDM challenge, compared to Jag½-sufficient GMDCs [38]. These data support the notion that Jag ligand expression by DCs can drive Th2 priming. However, the latter study also showed that whole-body Jag1/Jag2-floxed Cd11cCre mice and mice with intact Jag½ expression in CD11c+ cells exhibited similar allergic responses in the BAL following HDM sensitization and challenge [38]. Along these lines, another report indicated that while S. mansoni egg antigens (SEA) promoted GMDC Jag2 upregulation in vitro, Jag2 siRNA knockdown in GMDCs did not affect their ability to promote Th2 differentiation in vitro or in vivo [39]. Thus, DC expression of Jag ligands likely plays a role in Th2 priming; however, it may not be essential in all settings.

Outside of questions related to the role of Notch ligand expression by DCs during T cell priming, Notch receptor expression by DC subsets certainly impacts T helper responses. Studies utilizing DC-specific inhibition of Notch signaling in Rbpj-floxed Cd11cCre mice have demonstrated that the absence of Notch signaling in CD11c+ cells alone results in a selective loss of CD8α- cDCs in the spleen [40]. Notch2-floxed Cd11cCre mice also had a specific deficiency in splenic CD8α- CD11b+ cDCs that co-expressed the adhesion molecule Esam, as well as intestinal CD11b+CD103+ DCs [41]. Of note, it is unclear how Esam+ cDCs function in Type 2 inflammation, though CD11b+CD103+ DCs can play pleiotropic roles in Treg and Th17 cell polarization [41–43] and murine intestinal cDCs and CD11b+CD103+ DCs can drive Th2 cytokine production in the dLN in response to SEA challenge [44]. Together, these data suggest that Notch may promote the development of specific murine cDC subsets that direct the phenotype and function of various Th fates, including Th2 cells in the intestine. In humans, peripheral blood cDCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) express Notch receptors, and in vitro, exposure to Notch ligands causes human DCs to upregulate Notch-responsive genes such as HES and HEY1, and to alter the capacity of cDCs and pDCs to elicit cytokine production from T cells in response to TLR ligands [45]. While this latter study did not directly assess how specific Notch ligand exposure shapes the ability of human DCs to promote Th2 priming, overall, Notch signaling in DCs may play a role in the differentiation and function of cDC subsets, with the capacity to drive Th2 priming in specific tissues in mice and humans.

Despite the findings described above, further study is required to understand the importance of Notch for cDC subsets and pDCs in Type 2 immunity at various tissue sites. Of particular interest is whether Notch ligands or receptors play a role in the biology of cDC2s, critical APCs for Th2 priming during N. brasiliensis infection, as well as during HDM-driven allergic inflammation in mice [46,47]. In addition, it is unclear whether cDC2s and cDC1s, which are primary drivers of IFNγ production [48], exhibit differential expression of Notch ligands or receptors, and whether the highly immunomodulatory products of helminths might influence DC function and phenotype [49] through alteration of Notch ligand or receptor expression. To fill the gaps in our understanding of how Notch-driven processes govern Th2 differentiation, further mouse studies are required aiming to target Notch function in cDC2s and other DC subsets in vivo during Type 2 inflammation. The impact of these murine studies will be enhanced with further work using human cells.

Th2 cells: Notch as a key player in adaptive Type 2 immunity

The role of Notch in Th2 cell fate and function

Outside of the DC-intrinsic roles for Notch in regulating Th2 priming, there is a critical role for T cell-intrinsic Notch in Th2 differentiation and function. The same mouse study that described a role for distinct Notch ligands in inducing Th1 vs. Th2 differentiation also established a role for CD4+ T cell-intrinsic Notch signaling in regulating gene expression programs required for Th2 fate [34]. Murine CD4+ T cells lacking the Notch transcription factor Rbpj failed to acquire IL-4-producing capacity when exposed to Jagged-expressing DCs in vitro, and retroviral transduction of CD4+ T cells with activated Notch1 resulted in increased Gata3 expression and direct regulation of Il4 via Rbpj relative to controls [34]. Additionally, in vivo, Rbpj-floxed Cd4Cre mice displayed poor IL-4 responses to SEA challenge relative to littermate controls [50].

Additional studies have now delved into the molecular mechanisms by which Notch signaling can influence Th2 differentiation. In studies employing transduction of CD4+ T cells with the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) or DNMAML-floxed Cd4Cre T cells and measurement of Gata3 exon expression in vitro, Notch signaling directly regulated the transcription of the Gata3 exon 1a but not 1b, acting upstream of Gata3 to promote Th2 differentiation [50,51]. Notch-independent transcript expression of exon 1b was detected at early timepoints during Th2 differentiation following TCR stimulation of murine CD4+ T cells in vitro [52], suggesting that Notch might not play a key role in Gata3 activation in early priming. Rather, Notch might regulate Gata3 to promote Th2 maintenance. Consistent with this idea, DNMAML-floxed Cd4Cre mice exhibited dampened Type 2 effector mechanisms during infection with the murine whipworm Trichuris muris relative to Cd4Cre mice [53,54]; however, the Notch-dependent effects on Th2 responses and worm clearance could be rescued with anti-IFNγ treatment [54]. Notch can also control murine T cell survival [55], as mice treated with a Dll4 blocking antibody compared to an isotype control presented with exacerbated allergic lung inflammation in a cockroach allergen-driven model of allergy, with increased CD4+ T cell activation and global Il2 expression in the lung [56]. This study also found that murine CD4+ T cells exposed to Th2-inducing conditions in vitro, and which were cultured with Dll4 ligand for 5 days, exhibited increased apoptosis after 24–48 hours of rest time, compared to cells cultured in the absence of Dll4 ligand [56]. Together, these data indicate that T cell-intrinsic Notch does not seem to play a key role in the initiation of Th2 differentiation, but rather, that it might reinforce this process by maintaining the Th2 response, possibly via modulation of Il4 expression in Th2 cells [50,53,54], or by promoting Th2 survival [55,56] (Fig. 2). However, these possibilities remain speculative at this point and will require further investigation.

The influence of Notch on Th2 cells beyond helminth infection

Notch-dependent T cell production of Type 2 cytokines occurs in settings outside of helminth infection or allergy, including during viral and fungal infection and graft vs. host disease (GvHD). For instance, following murine RSV infection, antibody-mediated Dll4 inhibition led to increased frequencies of dLN CD4+ T cells and IL-13+ lung Foxp3+ Tregs [30], and increased parameters of Type 2 inflammation, including airway resistance and mucus production [57], relative to controls. During RSV-elicited exacerbation of cockroach antigen-induced allergy in mice, anti-Dll4 antibody treatment compared to isotype treatment reduced these same Type 2 inflammatory readouts after challenge [58]. Furthermore, the glycosyltransferase lunatic fringe (Lfng), which promotes Dll4-mediated Notch activation, was required in CD4+ T cells for fulminant Type 2 inflammation in this model, as evidenced by a decrease in mucus production and IL-4 and IL-13 production in the lungs of Lfng-floxed Cd4Cre mice, compared to control mice, following allergen challenge [58]. Upon infection with the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans, effective fungal control in the lung depends on IFNγ+ Th1 cells driving myeloid cell anti-microbial functions and Th17 cells reinforcing optimal IFNγ production [59]. In this model, mice that expressed DNMAML only in CD4+ T cells had impaired Th1 and Th2 responses relative to littermate controls, with reduced macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, and delayed fungal clearance [59]. Finally, in a murine model of GvHD in which C57BL/6 CD4+ T cells were transferred into irradiated Balb/c hosts, transferred DNMAML CD4+ T cells displayed impaired ex vivo production of T helper cytokines compared to transferred wild type (WT) CD4+ T cells [60]. Together, these data show that functional Notch signaling can regulate the ability of CD4+ T cells to produce Th2 cytokines in many inflammatory settings.

Notch in CD4+ T cell biology

How Notch contributes to the acquisition of regulatory or other T cell fates remains under study. A recent study found that Notch signaling could promote the development of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells that express Il4 during infection with N. brasiliensis, with Notch1/Notch2-floxed Cd4Cre mice exhibiting reduced Tfh that were Il4+ in the dLN compared to littermate controls [61]. Notch signals could also sustain a Treg phenotype and function during murine viral infection; specifically, anti-Dll4 anitbody treatment during RSV infection (compared to isotype control), led to reduced numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs in the mediastinal LN and increased Treg production of effector cytokines [30]. However, significant work is warranted to assess how Notch signaling impacts the development, effector function, and maintenance of Tfh and Treg cells. In addition, how Notch acts to balance effector vs. memory fates of CD4+ T cells in various Th contexts remains unclear. One report indicated that the Il4 enhancer, CNS2, was active in CD44hi CD4+ T cells (effector or memory precursor cells) and depended on Rbpj for activation; this in turn suggested that Notch might be able to promote T cell memory [62]. Here again, further work is needed to dissect the putative role of Notch in T cell memory formation, specifically in Th2 cells during murine and human helminth infections. Thus, many exciting investigation areas remain, and which may provide a better understanding of the influence of Notch on T cell biology in Type 2 inflammation.

Mast cells and basophils: Notch in innate granulocytes

The innate granulocytes include mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils, which release large quantities of pre-formed mediators, such as cytokines and histamine, in response to immunoglobulin E (IgE), or other antibodies binding and crosslinking surface Fc receptors [5]. For this reason, the dogma for many years dictated that gene transcription was not altered to a significant degree in these cells once they matured, even during inflammation. However, studies from the last decade have shown that these three cell types can in fact respond to environmental cues from cytokines and other factors to alter gene expression [63–65], and furthermore, that Notch signaling is a key regulator of these responses.

For instance, Dll1 signaling to Notch2 has been shown to drive the upregulation of Notch-responsive genes Hes1 and Gata3, facilitating mast cell differentiation from murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in vitro [65]. Notch can also affect murine mast cell activities during helminth infection: in Notch2-floxed Mx1Cre mice with Notch2-deficiency in mast cells, mast cells localized to the lamina propria rather than the epithelium during Strongyloides venezuelensis infection, a phenotype associated with impaired parasite clearance [66]. In addition, co-culture of murine BM-derived mast cells with Dll1, Dll4, Jag1 or Jag2-expressing cells led to enhanced IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13 production in vitro after crosslinking of the high-affinity IgE receptor, FcεR1α, compared to culture of crosslinked mast cells alone [67]. While much remains unexplored in this area, particularly related to the role of Notch in mast cell subset biology in various tissues, these data highlight a role for Notch in mast cell differentiation and function (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Notch can drive the differentiation and function of Type 2 innate effector cells in mice.

In the murine bone marrow (BM), Notch has a key role in steady-state hematopoiesis and is required for the effective development of group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) from common-lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) and mast cell development from granulocyte-macrophage precursors (GMPs). In the murine lung, the infiltration of ILC2s during N. brasiliensis infection requires Notch. Notch signaling also drives recruitment of IL-25-responsive KLRG1+ (not depicted) inflammatory ILC2s (iILC2s) during allergic inflammation in the lung. Activation of Notch in natural, lung resident ILC2s (nILC2s) in vitro can induce functional plasticity, normally characteristic of iILC2s, including Rorc expression and co-production of IL-13/IL-17 [28]. Eosinophil accumulation in allergic inflammation may also depend on Notch signaling. In the intestine, Notch is a driver of effective granulocyte localization, key to helminth clearance. Notch signaling in mast cells helps to position them within the small intestinal epithelium. Loss of functional Notch signaling in basophils reduces the proportion of basophils in the lamina propria (LP). This diminishes the likelihood that they are in close proximity to CD4+ T cells at this site, associated with a reduction in the frequencies of Gata3+ Th2 cells in the cecum during T. muris infection [10]. In vitro studies of mast cells and basophils also suggest that Notch can facilitate optimal production of effector cytokines, including IL-4, IL-6 and IL-13 [10,67,68]. The role of Notch for the development and function of alternatively-activated macrophages remains to be determined (not depicted).

Recent studies have shown that Notch signaling can also affect basophil gene expression, effector function and ability to promote Type 2 inflammation. In vitro, murine BM-derived basophils that were subjected to Notch inhibition using a chemical GSI, displayed decreased proliferation, increased cell death, and decreased Il4, Il6 and Il13 expression in response to a calcium ionophore, compared to basophils treated with vehicle alone [68]. Moreover, in a mouse model of airway allergy elicited by transfer of BM-derived basophils into OVA-sensitized mice, Rbpj−/−, compared to WT, basophils drove reduced mucus production and airway hyperactivity in response to methacholine [69]. In the context of murine helminth infection in vivo, mice that expressed DNMAML in basophils alone (DNMAML-floxed Mcpt8Cre mice) had reduced goblet cell hyperplasia and decreased clearance of the helminth T. muris compared to littermate control mice [10]. While loss of basophil-intrinsic Notch signaling did not alter infection-induced changes in splenic or intestinal basophil population size, it was associated with altered basophil localization within the cecum. Notch signaling-deficient basophils were less likely than Notch signaling-sufficient basophils to localize to the cecal lamina propria and near the base of crypts; this was also associated with impaired accumulation of Gata3-expressing CD4+ Th2 cells and a reduction in intestinal Il4 relative to controls [10]. Together, these findings suggest that Notch signaling is a key driver of effective mast cell and basophil localization in tissues associated with helminth expulsion.

At least in the case of basophils, the effects of Notch inhibition on Type 2 immune responses in the intestine have been specifically studied in murine basophils [10]. Such approaches offer distinct advantages to the researcher in dissecting how cell-specific effects of Notch signaling can impact broad Type 2 inflammatory responses and disease pathogenesis. Follow-up studies that employ basophil-specific deletion of Notch signaling components may thus allow for further examination of the importance of Notch-dependent basophil function in supporting Th2 responses in tissues and/or the dLN.

Data linking Notch signaling to eosinophil responses are not well developed. Human peripheral eosinophils express Notch machinery components [70], and Notch can promote GM-CSF-driven eosinophil chemokinesis, as evidenced from in vitro studies of human cells employing transwell or endothelial monolayer transmigration systems, and from in vivo studies in mice using GSI treatment during airway eosinophilia-associated OVA airway challenge [70,71]. Of note, this latter study did not target Notch inhibition in vivo to eosinophils alone.

Regardless, there is now strong evidence that Notch is an important regulator of effective granulocyte localization within tissues, demonstrating that proper positioning is important for optimal cell function and Type 2 immunity (Fig. 3). Collectively, these findings highlight a role for Notch in fine-tuning the transcriptional profile and localization of rare innate effectors to direct their function.

Macrophages: Does Notch have a role in alternative activation?

Given the importance of Notch signaling in regulating other myeloid populations in Type 2 inflammation, it seems likely that alternatively-activated macrophages are also influenced by Notch. Alternatively-activated macrophages are key in wound repair and the formation of granulomas during helminth infections [75,76]. Some studies have suggested that Notch could play a role in granuloma formation, as Schistosoma japonicum egg (SEA) antigen stimulation promoted alternative-activation associated with relative Notch1 and Jag1 upregulation in a murine cell line [77]. In vivo, in response to chitin administration, mice carrying a myeloid-cell deletion of Rbpj in Lyz2-expressing cells exhibited reduced peritoneal eosinophil and macrophage infiltration and reduced peritoneal cell expression of gene transcripts encoding Arginase1 and the mannose receptor (alternative activation-associated molecules), relative to control mice [78]. While these studies suggest that Notch may promote alternatively-activated macrophage polarization, there are a number of caveats, as the genetic approach used to target macrophages in the latter study might not adequately target all macrophages and might have off-macrophage effects [79]. Furthermore, these experiments have not been replicated in helminth infection models. Finally, there are also data that suggest that Notch signals can inhibit alternative-activation, as human monocyte-derived macrophages polarized in vitro with IL-4 in the presence of Dll4 have displayed reduced expression of alternatively-activated molecules such as CD206 and increased apoptosis relative to macrophages cultured in the absence of recombinant Dll4 [80]. Thus, a specific role for Notch in macrophage function during Type 2 immunity remains unclear.

Epithelial cells: Key effectors downstream of Type 2 immunity

Epithelial cells are critical players during Type 2 inflammation - they are often the first to experience helminth parasite-induced damage or allergen exposure, releasing alarmins IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP [19,81] that transduce damage signals to the immune system. Downstream of Type 2 immune activation, intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) responses are key to expulsion of gastrointestinal helminths [81]. Specifically, essential modifications to IEC biology are initiated in response to Type 2 inflammation-associated cytokines and are termed the “weep and sweep” response; well-characterized in the mouse model of helminth infection with T. muris, these inflammatory changes include increased IEC turnover, differentiation of goblet cells, mucus production, and secretion of anti-helminth molecules such as Relmβ, by goblet cells [82–85].

Epithelial cells express all receptors and ligands involved in Notch signaling [86], and Notch and Wnt are critical signaling pathways that function antagonistically to control IEC development in the crypt [87]. In mice, Notch signaling inhibition, broadly or specifically in the epithelium, results in a loss of “stemness” and proliferative capacity of intestinal crypt cells and a skew towards development of secretory cells such as goblet and Paneth cells, leading to goblet cell hyperplasia and increased mucin production [86–88]. For example, mice treated with anti-Notch1/Notch2 blocking antibodies compared to control mice demonstrated a loss of stem cell markers (Lgr5) in the crypt base, reduced stem cell proliferation, and an increase in expression of markers associated with secretory fate, such as lysozyme, observed using immunofluorescence microscopy [87]. Such changes can reduce the absorptive capacity of the intestine, leading to diarrhea followed by weight loss [89]. In another study, compared to control mice, animals with a global knockout or epithelial-specific deletion of Hes1 (a Notch-dependent transcriptional repressor active in the intestinal epithelium), exhibited intestinal microbial dysbiosis and reduced expression of genes encoding antimicrobial peptides such as serum amyloid A and Reg3 family members [90].

Based on the role of Notch in IEC lineage specification and epithelial function, Notch is almost certainly involved in regulating IEC responses during helminth infection. Recent studies in mice have shown that a specific IEC type, the tuft cell, is the primary producer of IL-25 [91–93]. While little is known about the role of Notch in tuft cell function, IEC-specific knockdown of the tuft cell-associated transcription factor Dclk in Dclk1-floxed VillinCre mice led to dysregulation of tuft cell development and altered IEC expression of Notch1 protein [94]. Studies by our laboratory and others have shown that mice in which Notch signaling was inhibited by DNMAML, and under the control of cell-specific Cre in basophils or CD4+ T cells, had reduced goblet cell hyperplasia during T. muris infection compared to control mice [10,53,69]. These findings suggest that immune cell-intrinsic Notch signaling may help to promote production of IL-4 and IL-13 or other factors that act on IECs to elicit goblet cell responses. We hypothesize that such production of Type 2 cytokines may be required to override IEC-intrinsic Notch-dependent suppression of secretory cell differentiation [86–88], allowing for the emergence of goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus production to drive intestinal helminth expulsion [95,96]. While IL-33 can decrease Notch ligand expression in the mucosa in a murine experimental model of dextran-sulfate sodium-dependent colitis, attenuating Notch signals and allowing for goblet cell hyperplasia [97], how immune cell-derived Type 2 cytokines function in such processes during helminth infection remains unclear. Future studies will be needed to determine how IEC subtypes that mediate helminth sensing and clearance (such as tuft and goblet cells), balance distinct roles for Notch in the intestine during homeostasis and worm infection.

Harnessing the influence of Notch to control Type 2 function: A viable option?

Given the role that Notch plays in a large variety of developmental and functional pathways, it is not surprising that Notch is a potential drug target in many conditions and diseases. However, to date, there have been limited attempts to harness Notch signaling to alter the course of Type 2 inflammation. Recent studies have highlighted opportunities to block Notch to prevent the development of allergy, asthma or fibrosis, in particular. During S. japonicum infection, treatment of mice with the GSI N-[N-[3,5-difluorophenacetyl]-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) relative to treatment with vehicle control was associated with a reduction in liver granuloma formation, suggesting that Notch inhibition could mitigate hepatic fibrotic responses [77]. While decreasing granuloma formation may be desirable in one sense to help maintain hepatic function, conversely, the granuloma is also highly protective against egg-induced damage during schistosome infection [16,98]. In a mouse model of OVA-dependent allergic rhinitis, mice treated with DAPT at the time of OVA challenge had reduced allergic symptoms and decreased concentrations of serum IgE and Type 2 cytokines relative to control mice [99]. While these and other studies provide some proof-of-concept that Notch signaling could be inhibited to prevent or treat fibrotic or allergic disease, further work is needed to elucidate how Notch functions in Type 2 immunity before serious preclinical studies can commence. In addition, since Notch also functions in the development and function of Th1 and Treg cells [30,54,100], on-target, yet undesirable effects of any Notch-specific therapies must be considered.

In the context of helminth infection, it could be envisaged that therapies would potentiate Notch function in order to increase Type 2 immune efficacy or perhaps block Notch in IECs to promote protective epithelial responses; however, such studies have not yet been attempted. Nevertheless, activation of Notch using small molecule agonists and recombinant ligands has certainly been possible in vivo in rodent models in other disease states. In a murine model of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in which human AML cells were injected subcutaneously, mice with activated Notch demonstrated tumor suppression relative to control mice [101]. However, given that over-activation of Notch is often tumorigenic, any such approach should be developed with caution. Thus, future research has the potential to generate many new opportunities to target Notch, by limiting or promoting Type 2 immunity. However, significant work using mouse models and ex vivo analyses of human cells in patients with ongoing Type 2 inflammation will also be required to increase our basic understanding of Notch function in Type 2 inflammation (Box 2).

Box 2. Notch receptor ligand-interactions: immune regulation in time and space.

A major gap in knowledge in the study of Notch in the immune system is the lack of understanding of where and when immune cells encounter critical Notch ligands and ligand sources. A recent study in a mouse model of GvHD identified LN stromal cells, particularly fibroblasts, that had expressed or were expressing Ccl19 – a key source of induction of Notch ligands in the priming of alloreactive T cells [103]. The authors suggested that chemokine expression attracted T cells to specific stromal cell niches, where they encountered activating signals, including Notch ligands, over a sustained period of time [103]. In support of this idea, deletion of Delta ligands in Ccl19+ stromal cells inhibited splenic Esam+ cDC2 development in the steady-state, and resulted in defective Tfh and germinal center formation following immunization with S. mansoni eggs [104]. These data indicated that LN fibroblastic stromal cells may be important sources of Notch ligands shaping DC and T cell responses, by orchestrating the spatial organization of cells within the LN.

While innate Type 2 effector cell types other than DCs may not spend considerable time in LNs, Notch might also control spatial organization of innate cells across tissues or within a tissue such as the intestine, promoting their function. Accordingly, basophil-intrinsic Notch signaling has been shown to be required for normal basophil localization in the intestinal crypt architecture associated with optimal Type 2 inflammatory and Th2 responses in the murine intestine following T. muris infection [10]. In this context, it is possible that basophils may encounter instructive ligand-bearing cells in the periphery enabling them to migrate and localize into tissues. Perhaps more likely, however, basophils might encounter ligand-bearing cells in inflamed tissues, with Notch signaling acting either to retain these cells and ensure their function at specific locations, or to provide a signal that promotes function, only once the basophils reach a specific location within the tissue. Candidate ligand-bearing cell types in this setting could include vascular endothelial cells, fibroblastic stromal cells and epithelial cells, although this clearly remains to be tested [103,105,106]. Ultimately, across cell types, it remains to be determined how Notch signaling organizes cellular responses in both space and time in tissues and LNs during helminth infections to promote a balanced inflammatory response that is effective in protecting the host, yet avoids unnecessary tissue damage.

Concluding remarks: Notching it up to Type 2 immunity

Recent advances have provided new and exciting insights into the function of Notch signaling in Type 2 inflammation in helminth infection and allergy. Notch has effects on a multitude of cellular players in the Type 2 immune cascade including epithelial cells, innate immune cells and adaptive CD4+ T cells. Leveraging this unique biology, there is a growing possibility that the Notch signaling pathway could offer new avenues to harness Type 2 effector cells therapeutically in helminth infections and allergies. In particular, future studies investigating how Notch regulates immune and epithelial function in inflamed tissues in mice and humans may provide new insights on how tissue architecture and cellular positioning might be manipulated to rapidly and dynamically regulate Type 2 inflammatory responses. While numerous outstanding questions remain (see Outstanding Questions), studies that can ultimately translate important findings from mouse models to humans are needed to fully realize the potential of Notch pathway targeting in the treatment of helminth infections and allergies.

Outstanding questions.

What are the key Notch receptors and ligands that impact immune cell function in Type 2 inflammation?

In what tissue(s) do Type 2 immune effectors encounter Notch ligands?

Is the timing of Notch signaling in the course of the Type 2 inflammatory response important for altering the outcome of the signal for a specific cell type?

How do Type 2 inflammation-associated immune cells and IECs integrate Notch signals with other signals from cytokines and lipid mediators to regulate gene expression?

Does Notch function in the development of adaptive memory responses and in innate immune cells during Type 2 inflammation?

Is the Notch pathway involved in the development, recruitment or function of eosinophils and alternatively-activated macrophages?

How do helminths, their products and allergens modulate the function of the Notch pathway in Type 2 inflammation?

Are Notch receptor-ligand interactions important mediators of cellular positioning in the tissue that promotes fulminant Type 2 inflammation?

Highlights.

Notch contributes to the development and function of key Type 2 effector cell types, including ILC2s, mast cells, basophils, Th2 cells and IECs

Notch is required to maintain Th2 and other Th fates in T cells

Notch is a driver of epithelial cell fate in the intestine, with the intestinal site strongly influenced by Notch inhibition

Targeted blockade of Notch signaling in various Type 2 effector cell types, including basophils and CD4+ T cells, leads to the abrogation of effective Type 2 immunity and impaired worm clearance during helminth infection

Therapeutic manipulation of Notch signaling-dependent cellular responses is a potential avenue for the treatment of diseases associated with Type 2 inflammation, including helminth infection and allergy

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH NIAID (K22 AI116729, R01 AI132708 and R01 AI130379), the Cornell University Research in Animal Health Grants Program and Cornell University start-up funds (to E.D.T.W). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank all members of the Tait Wojno lab for their constructive contributions to discussions around this work.

Glossary

- Alarmin

signal released by dead or dying cells, in response to tissue damage (e.g. by pathogen challenge).

- Alternatively-activated macrophage

phenotype in Type 2 inflammation promoting wound-healing and granuloma formation.

- Conventional DCs (cDCs)

express the transcription factor Zbtb46 and feature high CD11c expression.

- cDC1s

express Batf3 and the surface markers CD103/CD8α; they prime Th1 and CD8+ T cells.

- cDC2s

depend on Irf4, have the surface marker profile CD11b+CD103-CD8α-, and prime Th2 cells.

- Chitin administration

murine model inducing Type 2 inflammation via delivery of the immunoactivatory polysaccharide chitin.

- Esam

surface adhesion marker.

- Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)

murine model for the human demyelinating disease multiple sclerosis.

- Goblet cell

secretory epithelial cells producing mucus.

- Graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD)

immune-mediated disease following allogeneic bone marrow transplant with donor immune cells, attacking host tissues.

- Granulocyte-macrophage progenitor

hematopoietic precursor for macrophages, DCs, monocytes, basophils, eosinophils and mast cells.

- Granuloma

tissue lesion that walls off pathogens or their products; composed of leukocyte infiltrates, collagen and fibrotic tissue.

- Inflammatory ILC2s (iILC2s)

IL-25-responsive subset that can develop into nILC2s.

- Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)

rare innate lymphocytes lacking antigen-specific receptors, dividing rapidly and producing cytokines upon stimulation.

- Mastermind-like (MAML)

Mastermind-like protein family members act as co-activators for Notch-regulated transcription.

- Natural ILC2s (nILC2s)

subset found in mucosal tissues in the steady-state, expanding during Type 2 inflammation and expressing ST2.

- OVA-specific OTII mouse T cells

murine CD4+ T cells that express a transgenic T cell receptor specific for peptide from chicken egg ovalbumin.

- Paneth cells

secretory epithelial cells producing antimicrobial compounds; they help maintain the intestinal barrier.

- Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs)

highly specialized DCs that rapidly produce Type I IFNs.

- RBPJ

transcriptional repressor in the absence of Notch; transcriptional activator of target genes upon Notch activation.

- Schistosomiasis

fibrotic disease caused by infection with Schistosoma trematodes, water-borne helminths that reside within host vasculature.

- Stemness

ability of a stem cell to develop into different types of fully-differentiated cells.

- T follicular helper cells (Tfh)

CD4+ T cells in germinal centers that support B cell selection, class switching, and affinity maturation.

- Th17

CD4+ T cells express the transcription factor Rorγt; they produce IL-17 and IL-22 and act against extracellular bacteria and fungi.

- Th2 priming

polarization of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells.

- TLR

pattern-recognition receptors recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

- Treg

CD4+ T cells that suppress immune responses.

- Tuft cells

chemosensory IECs producing IL-25 in response to helminths.

- Type 2 inflammation

inflammation type activated during helminth parasite infection and allergy.

- Weep and sweep

epithelial cell response facilitating parasite clearance, featuring increased mucus production, cell turnover and mucosal barrier permeability.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gause WC et al. (2013) Type 2 immunity and wound healing: evolutionary refinement of adaptive immunity by helminths. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gieseck RL et al. (2017) Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat Rev Immunol DOI: 10.1038/nri.2017.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weatherhead JE et al. (2017) The Global State of Helminth Control and Elimination in Children. Pediatric Clinics of North America 64, 867–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell SJ et al. (2016) A Critical Appraisal of Control Strategies for Soil-Transmitted Helminths. Trends Parasitol. 32, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb LM and Tait Wojno E.D. (2017) The role of rare innate immune cells in Type 2 immune activation against parasitic helminths. Parasitology 144, 1288–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inclan-Rico JM and Siracusa MC (2018) First Responders: Innate Immunity to Helminths. Trends Parasitol. 34, 861–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulendran B and Artis D (2012) New Paradigms in Type 2 Immunity. Science 337, 431–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchery T et al. (2014) The Differentiation of CD4(+) T-Helper Cell Subsets in the Context of Helminth Parasite Infection. Front Immunol 5, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tait Wojno E.D. and Artis D (2016) Emerging concepts and future challenges in innate lymphoid cell biology. J Exp Med 213, 2229–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb LM et al. (2019) The Notch signaling pathway promotes basophil responses during helminth-induced type 2 inflammation. J Exp Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maizels RM and Hewitson JP (2016) Myeloid Cell Phenotypes in Susceptibility and Resistance to Helminth Parasite Infections. Microbiology Spectrum 4, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen JE and Sutherland TE (2014) Host protective roles of type 2 immunity: parasite killing and tissue repair, flip sides of the same coin. Semin Immunol 26, 329–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambrecht BN and Hammad H (2015) The immunology of asthma. Nat Immunol 16, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siebel C and Lendahl U (2017) Notch Signaling in Development, Tissue Homeostasis, and Disease. Physiological Reviews 97, 1235–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radtke F et al. (2013) Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce EJ and MacDonald AS (2002) The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Immunol 2, 499–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilagan MXG et al. (2011) Real-time imaging of notch activation with a luciferase complementation-based reporter. Sci Signal 4, rs7–rs7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopan R and Ilagan MXG (2009) The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell 137, 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyesola OO et al. (2018) Cytokines and beyond_ Regulation of innate immune responses during helminth infection. Cytokine DOI: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker JA and McKenzie AN (2013) Development and function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Current opinion in immunology 25, 148–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halim TYF et al. (2012) Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity 36, 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halim TYF et al. (2014) Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity 40, 425–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong SH et al. (2012) Transcription factor RORα is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol 13, 229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentek R et al. (2013) Modulation of Signal Strength Switches Notch from an Inducer of T Cells to an Inducer of ILC2. Front Immunol 4, 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maillard I et al. (2006) The requirement for Notch signaling at the β-selection checkpoint in vivo is absolute and independent of the pre–T cell receptor. J Exp Med 203, 2239–2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Q et al. (2013) T Cell Factor 1 Is Required for Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Generation. Immunity 38, 694–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y et al. (2014) IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1hi cells are multipotential “inflammatory” type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 16, 161–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang K et al. (2017) Cutting Edge: Notch Signaling Promotes the Plasticity of Group-2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. J Immunol 198, 1798–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen JE et al. (2015) IL-17 and neutrophils: unexpected players in the type 2 immune response. Current opinion in immunology 34, 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ting H-A et al. (2017) Notch Ligand Delta-like 4 Promotes Regulatory T Cell Identity in Pulmonary Viral Infection. J Immunol 198, 1492–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker JA and McKenzie ANJ (2017) TH2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol DOI: 10.1038/nri.2017.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phythian-Adams AT et al. (2010) CD11c depletion severely disrupts Th2 induction and development in vivo. J Exp Med 207, 2089–2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammad H et al. (2010) Inflammatory dendritic cells--not basophils--are necessary and sufficient for induction of Th2 immunity to inhaled house dust mite allergen. J Exp Med 207, 2097–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amsen D et al. (2004) Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell 117, 515–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamaguchi E et al. (2002) Expression of Notch ligands, Jagged1, 2 and Delta1 in antigen presenting cells in mice. Immunol Lett 81, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun J et al. (2008) Suppression of Th2 Cell Development by Notch Ligands Delta1 and Delta4. J Immunol 180, 1655–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto M et al. (2009) Jagged1 on dendritic cells and Notch on CD4+ T cells initiate lung allergic responsiveness by inducing IL-4 production. J Immunol 183, 2995–3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tindemans I et al. (2017) Notch signaling in T cells is essential for allergic airway inflammation, but expression of the Notch ligands Jagged 1 and Jagged 2 on dendritic cells is dispensable. J Allergy Clin Immunol 140, 1079–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krawczyk CM et al. (2008) Th2 Differentiation Is Unaffected by Jagged2 Expression on Dendritic Cells. J Immunol 180, 7931–7937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caton ML et al. (2007) Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. J Exp Med 204, 1653–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis KL et al. (2011) Notch2 receptor signaling controls functional differentiation of dendritic cells in the spleen and intestine. Immunity 35, 780–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coombes JL et al. (2007) A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic aciddependent mechanism. J Exp Med 204, 1757–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaensson E et al. (2008) Small intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells display unique functional properties that are conserved between mice and humans. J Exp Med 205, 2139–2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer JU et al. (2017) Different populations of CD11b+ dendritic cells drive Th2 responses in the small intestine and colon. Nat Commun 8, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez-Cabezas B et al. (2011) Ligation of Notch Receptors in Human Conventional and Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Differentially Regulates Cytokine and Chemokine Secretion and Modulates Th Cell Polarization. J Immunol 186, 7006–7015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y et al. (2013) Control of T Helper 2 Responses by Transcription Factor IRF4-Dependent Dendritic Cells. Immunity 39, 722–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams JW et al. (2013) Transcription factor IRF4 drives dendritic cells to promote Th2 differentiation. Nat Commun 4, 2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Everts B et al. (2016) Migratory CD103+ dendritic cells suppress helminth-driven type 2 immunity through constitutive expression of IL-12. J Exp Med 213, 35–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maizels RM et al. (2018) Modulation of Host Immunity by Helminths: The Expanding Repertoire of Parasite Effector Molecules. Immunity 49, 801–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amsen D et al. (2007) Direct Regulation of Gata3 Expression Determines the T Helper Differentiation Potential of Notch. Immunity 27, 89–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang TC et al. (2007) Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity 27, 100–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu Q et al. (2009) T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-γ. Nat Immunol 10, 992–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tu L et al. (2005) Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med 202, 1037–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bailis W et al. (2013) Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple helper T cell programs independently of cytokine signals. Immunity 39, 148–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helbig C et al. (2012) Notch controls the magnitude of T helper cell responses by promoting cellular longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 9041–9046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jang S et al. (2010) Notch Ligand Delta-Like 4 Regulates Development and Pathogenesis of Allergic Airway Responses by Modulating IL-2 Production and Th2 Immunity. J Immunol 185, 5835–5844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schaller MA et al. (2007) Notch ligand Delta-like 4 regulates disease pathogenesis during respiratory viral infections by modulating Th2 cytokines. J Exp Med 204, 2925–2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mukherjee S et al. (2014) STAT5-Induced Lunatic Fringe during Th2 Development Alters Delta-like 4-Mediated Th2 Cytokine Production in Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Exacerbated Airway Allergic Disease. J Immunol 192, 996–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neal LM et al. (2017) T Cell–Restricted Notch Signaling Contributes to Pulmonary Th1 and Th2 Immunity during Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. J Immunol 199, 643–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y et al. (2011) Notch signaling is a critical regulator of allogeneic CD4+ T-cell responses mediating graft-versus-host disease. Blood 117, 299–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dell’Aringa M and Reinhardt RL (2018) Notch signaling represents an important checkpoint between follicular T-helper and canonical T-helper 2 cell fate. Mucosal Immunol. DOI: 10.1038/s41385-018-0012-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanaka S et al. (2006) The Interleukin-4 Enhancer CNS-2 Is Regulated by Notch Signals and Controls Initial Expression in NKT Cells and Memory-Type CD4 T Cells. Immunity 24, 689–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Siracusa MC et al. (2011) TSLP promotes interleukin-3-independent basophil haematopoiesis and type 2 inflammation. Nature 477, 229–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siracusa MC et al. (2012) Functional heterogeneity in the basophil cell lineage. Adv. Immunol 115, 141–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakata-Yanagimoto M et al. (2008) Coordinated regulation of transcription factors through Notch2 is an important mediator of mast cell fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 105, 7839–7844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakata-Yanagimoto M et al. (2011) Notch2 signaling is required for proper mast cell distribution and mucosal immunity in the intestine. Blood 117, 128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakano N et al. (2015) Notch signaling enhances FcεRI-mediated cytokine production by mast cells through direct and indirect mechanisms. J Immunol 194, 4535–4544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qu S-Y et al. (2017) Notch signaling pathway regulates the growth and the expression of inflammatory cytokines in mouse basophils. Cell. Immunol 318, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qu S-Y et al. (2017) Transcription factor RBP-J-mediated signalling regulates basophil immunoregulatory function in mouse asthma model. Immunology 152, 115–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radke AL et al. (2009) Mature human eosinophils express functional Notch ligands mediating eosinophil autocrine regulation. Blood 113, 3092–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu LY et al. (2015) Notch signaling mediates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor priming-induced transendothelial migration of human eosinophils. Allergy 70, 805–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perrigoue JG et al. (2009) MHC class II-dependent basophil-CD4+ T cell interactions promote T(H)2 cytokine-dependent immunity. Nat Immunol 10, 697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Plantinga M et al. (2013) Conventional and Monocyte-Derived CD11b+ Dendritic Cells Initiate and Maintain T Helper 2 Cell-Mediated Immunity to House Dust Mite Allergen. Immunity 38, 322–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang X-Z et al. (2019) A case of mistaken identity: The MAR-1 antibody to mouse FcεRIα cross-reacts with FcγRI and FcγRIV. J Allergy Clin Immunol DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herbert DR et al. (2004) Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hewitson JP et al. (2015) Concerted activity of IgG1 antibodies and IL-4/IL-25-dependent effector cells trap helminth larvae in the tissues following vaccination with defined secreted antigens, providing sterile immunity to challenge infection. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng S et al. (2016) Inhibition of Notch Signaling Attenuates Schistosomiasis Hepatic Fibrosis via Blocking Macrophage M2 Polarization. PLoS ONE 11, e0166808–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Foldi J et al. (2016) RBP-J is required for M2 macrophage polarization in response to chitin and mediates expression of a subset of M2 genes. Protein & Cell 7, 201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vannella KM et al. (2014) Incomplete deletion of IL-4Rα by LysM(Cre) reveals distinct subsets of M2 macrophages controlling inflammation and fibrosis in chronic schistosomiasis. PLoS Pathog 10, e1004372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pagie S et al. (2018) Notch signaling triggered via the ligand DLL4 impedes M2 macrophage differentiation and promotes their apoptosis. DOI: 10.1186/s12964-017-0214-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hammad H and Lambrecht BN (2015) Barrier Epithelial Cells and the Control of Type 2 Immunity. Immunity 43, 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hasnain SZ et al. (2011) Muc5ac: a critical component mediating the rejection of enteric nematodes. J Exp Med 208, 893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Herbert DR et al. (2009) Intestinal epithelial cell secretion of RELM-beta protects against gastrointestinal worm infection. J Exp Med 206, 2947–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hasnain SZ et al. (2010) Changes in the mucosal barrier during acute and chronic Trichuris muris infection. Parasite Immunol 33, 45–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cliffe LJ et al. (2005) Accelerated intestinal epithelial cell turnover: a new mechanism of parasite expulsion. Science 308, 1463–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Es JH et al. (2005) Notch/γ-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature 435, 959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tian H et al. (2015) Opposing Activities of Notch and Wnt Signaling Regulate Intestinal Stem Cells and Gut Homeostasis. CellReports 11, 33–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou Y et al. (2014) Nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 increases intestinal goblet cell differentiation through an mTOR/Notch signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2882–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wei P et al. (2010) Evaluation of Selective -Secretase Inhibitor PF-03084014 for Its Antitumor Efficacy and Gastrointestinal Safety to Guide Optimal Clinical Trial Design. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 9, 1618–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo X-K et al. (2018) Epithelial Hes1 maintains gut homeostasis by preventing microbial dysbiosis. Sci Rep 110, 263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moltke von, J. et al. (2016) Tuft-cell-derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2epithelial response circuit. Nature 529, 221–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Howitt MR et al. (2016) Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science 351, 1329–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gerbe F et al. (2016) Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 529, 226–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.May R et al. (2014) Brief Report: Dclk1 Deletion in Tuft Cells Results in Impaired Epithelial Repair After Radiation Injury. Stem Cells 32, 822–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McKenzie GJ et al. (1998) A distinct role for interleukin-13 in Th2-cell-mediated immune responses. Curr. Biol. 8, 339–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hasnain SZ et al. (2010) Mucin gene deficiency in mice impairs host resistance to an enteric parasitic infection. Gastroenterology 138, 1763–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Imaeda H et al. (2011) Interleukin-33 suppresses Notch ligand expression and prevents goblet cell depletion in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 28, 573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hams E et al. (2013) The schistosoma granuloma: friend or foe? Front Immunol 4, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shi L et al. (2017) The effect of blocking Notch signaling by γ-secretase inhibitor on allergic rhinitis. 98, 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Samon JB et al. (2008) Notch1 and TGF 1 cooperatively regulate Foxp3 expression and the maintenance of peripheral regulatory T cells. Blood 112, 1813–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ye Q et al. (2016) Small molecule activation of NOTCH signaling inhibits acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep DOI: 10.1038/srep26510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guruharsha KG et al. (2012) The Notch signalling system: recent insights into the complexity of a conserved pathway. Sci Rep 13, 654–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chung J et al. (2017) Fibroblastic niches prime T cell alloimmunity through Delta-like Notch ligands. J Clin Invest 127, 1574–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fasnacht N et al. (2014) Specific fibroblastic niches in secondary lymphoid organs orchestrate distinct Notch-regulated immune responses. J Exp Med 211, 2265–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gamrekelashvili J et al. (2017) Regulation of monocyte cell fate by blood vessels mediated by Notch signalling. Nat Commun 7, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Demitrack ES and Samuelson LC (2016) Notch regulation of gastrointestinal stem cells. 594, 4791–4803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]