Introduction

In the current era of improving life expectancy for individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), pulmonary disease remains the primary cause of severe morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, many individuals with CF die from respiratory failure without referral for lung transplantation (LTx) [1, 2]. LTx referral is best initiated for individuals with advanced but not end-stage lung disease; emergent referral (Table 1) does not allow time for careful consideration of the LTx option and is not universally available. Early referral for LTx gives individuals with CF the opportunity to learn more about the risks and benefits of LTx, both generally and specific to their clinical situation, so they can make informed decisions. While LTx is not the right option for every individual with CF, the discussion is important for everyone. Early LTx referral increases the likelihood of an individual being a candidate for transplant by giving the patient an understanding of their specific barriers to LTx, as well as an opportunity to address those barriers. While many individuals who meet these Consensus Guidelines’ criteria for referral will be too early for listing,it is important to recognize that referral does not necessarily lead to a full evaluation or listing, but instead gives individuals with CF, their families (“family” will be used throughout this document to refer to the patient’s desired support system, which may or may not include relatives), and the CF care team access to the transplant-specific expertise of the LTx team. Progressing from routine CF care to LTx can be viewed as a transition. As modeled by the transition from pediatric to adult care, it is facilitated by education, communication and support for both the individual and family. Communication between the CF Center and Transplant Center is essential for a smooth transition. Early referral for LTx allows individuals to be medically, psychosocially, and financially prepared for LTx should the need arise. Late referral may lead to death on the transplant waiting list [2] or increased morbidity and/or mortality in the immediate post-operative period stemming from severe pre-operative illness [3]. While there may not be a perfect “window” for referral, an inclusive approach reduces the likelihood that eligible patients miss their opportunity for LTx. The goal of these Consensus Guidelines is to provide pragmatic recommendations and guidance to the CF community to facilitate better identification and timely referral, listing, and transplantation of those individuals with CF who have advanced lung disease (ALD).

Table 1:

Explanation of terminology

| Lung transplant referral | The act of sending a request and transmitting medical records to a lung transplant center to assess an individual’s candidacy for lung transplantation, usually through a clinic visit at the transplant center. In addition to the lung transplant assessment itself, the referral serves as an opportunity for the individual with cystic fibrosis (CF), their family, and the CF care team to gain access to the expert opinion of the lung transplant center. Depending on the situation and transplant program practices, it may result in a brief evaluation with a focus on education, discussion of potential barriers, or a complete evaluation. |

| Lung transplant evaluation | Consultation and diagnostic testing to assess disease severity and identify whether specific barriers to lung transplantation exist and whether those barriers are modifiable. The evaluation involves a comprehensive assessment of the individual’s medical condition and comorbidities, psychosocial situation, and financial/insurance resources. |

| Lung transplant listing | Placement on the lung transplant waitlist as an appropriate candidate for lung transplant to await a suitable donor. Listing is dependent on the completion of an evaluation, approval by a lung transplant selection committee, and insurance coverage for the transplant. A patient’s status on the list is fluid and can change based on disease severity or the development of contraindications after listing. |

| Early referral | Referral of an individual prior to the medical need for lung transplantation. |

| Timely referral | Referral of an individual with medical indications for lung transplantation, likely requiring listing, without an urgent indication for transplant (e.g. acute respiratory failure). |

| Late referral | Referral of an individual for transplant consideration when the individual is too sick to undergo routine transplant evaluation (e.g. emergent referral for an individual in acute respiratory failure). Late referral may lead to death without transplant because of inadequate time to proceed with listing or limited lung donor availability, or to poor post-transplant outcomes (e.g. increased post-operative morbidity/mortality) in the setting of severe pre-transplant illness. |

| Consultation with lung transplant center | Physician to physician conversation via phone, email or in-person about the individual with CF. |

| Communication between CF and lung transplant centers | Phone call, email, or medical record notes to the lung transplant team (MD, RN, social work, dietician, as indicated) from the CF care team and vice versa. |

Methods

The CF Foundation invited a multidisciplinary team including adult and pediatric CF and transplant pulmonologists, a clinical psychologist, a clinical social worker, a transplant recipient with CF, a former CF nurse, and a transplant coordinator to participate in development of consensus guidelines. The committee met for a virtual kickoff meeting on September 26, 2017 to determine the scope of the work and divide into three workgroups focusing on: timing for transplant referral; early referral and modifiable barriers; and transition to transplant care. Several PICO (Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome) questions were developed by each workgroup. These PICO questions were reviewed by the workgroup leaders and chairs to ensure there was no overlap between the working groups. The workgroups performed literature searches in PubMed. Information about the specific literature searches can be found in the Online Supplement. The workgroup leads and chairs met monthly to discuss the progress of their workgroups and address any questions and potential overlap between the workgroups.

Information was also gathered from a focus group of CF transplant recipients and spouses of recipients to inform the recommendation statements, tables and figures presented in this manuscript.

The workgroups developed draft recommendations based on data from the relevant publications identified in the literature searches and learnings from the focus group. Workgroups discussed the recommendations on monthly phone calls. The committee reconvened on May 11, 2018 to revise and vote on the draft recommendation statements. An a priori voting threshold of 80% agreement was established. The committee discussed each recommendation statement, and revised the phrasing of the statement as needed, prior to voting. After this meeting, the chairs and workgroup leads drafted the manuscript. The draft manuscript was reviewed and approved by the committee and focus group. On September 19, 2018, the lung transplant referral guidelines were distributed for public comment.

The committee reviewed the results of the public comment. Based on feedback received, the committee reconsidered eight recommendations (original statement numbers 1, 6, 9, 16, 17, 19, 20, and 21). These statements were revised and voted on again on a virtual meeting on December 7, 2018. Committee members who were unable to attend this meeting sent their votes to the guidelines specialist who tallied the results for the chairs.

Focus Group

A focus group of seven CF transplant recipients and two spouses of recipients (hereafter referred to as “the focus group”) was organized to identify priority issues from the patient’s perspective. Although focus group content and data synthesis are qualitative by nature, these ancillary data sources can provide informative clinical data [4, 5]. The focus group participated in seven, one-hour long video-calls led by a transplant psychologist (PJS) and an adult with CF (AL). Following an introductory session during which thematic content was identified and analyzed, the focus group participated in five content-specific calls and one summary review call. Themes identified during the introductory call included: 1) timing of transplant information delivered in CF Clinic, 2) individual’s transplant-related expectations, 3) treatment team transition issues (from CF to transplant care), 4) stigma associated with the need for transplantation, and 5) concerns regarding social support during the transition to transplant. All calls were video- and audio-recorded in order to facilitate re-analysis by focus group leaders.

Discussion of Recommendation Statements

There was 100% agreement among Lung Transplant Referral Committee members with the consensus guideline recommendation statements as published (listed in Table 2).

Table 2:

Recommendation Statements

| Recommendation | % Consensus among Transplant Referral Guidelines Committee (N=16) | |

| 1 | The CF Foundation recommends routine clinician-led efforts to discuss disease trajectory and treatment options, including a discussion of lung transplantation. | 100% |

| 2 | The CF Foundation recommends CF care team initiated discussion regarding lung transplantation with all individuals with CF and an FEV1 less than 50% predicted. | 100% |

| 3 | The CF Foundation recommends the use of up-to-date CF-specific transplant resources to promote understanding of the transplant journey and to minimize misconceptions regarding outcomes. | 100% |

| 4 | The CF Foundation recommends that CF clinicians develop relationships with peers at partnering transplant centers to:

|

100% |

| 5 | The CF Foundation recommends that the individual’s CF care team elicit and address CF-specific psychosocial and physical concerns about lung transplantation to facilitate transition to transplant. | 100% |

| 6 | The CF Foundation recommends that modifiable barriers to lung transplantation be addressed preemptively to optimize transplant candidacy; however, unresolved barriers should not preclude referral. Potentially modifiable barriers may include but are not limited to: nutritional status, diabetes management, physical inactivity or deconditioning, adherence behaviors, mental health issues, substance use, and psychosocial factors. | 100% |

| 7 | The CF Foundation recommends the CF and lung transplant care teams acknowledge and provide support for mental health concerns regarding the referral and evaluation process for transplant that are unique to individuals with CF. | 100% |

| 8 | For individuals with CF who are 18 years of age and older, the CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral no later than when:

OR

OR

|

100% |

| 9 | For individuals with CF who are under the age of 18 years, the CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral no later than when:

OR

OR

|

100% |

| 10 | For individuals with CF and an FEV1 <40% predicted, the CF Foundation recommends an annual 6-minute walk test (6MWT), assessment of need for supplemental oxygen, and venous blood gas to screen for markers of severe disease that may warrant transplant referral. | 100% |

| 11 | For individuals with CF who are 18 years of age and older with FEV1 <40% predicted, the CF Foundation recommends a baseline echocardiogram to screen for pulmonary hypertension. | 100% |

| 12 | The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral, regardless of FEV1, when there are markers of shortened survival, including:

OR

OR

OR

|

100% |

| 13 | The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for adults with CF with a BMI <18 and FEV1 <40% predicted while concurrently working to improve nutritional status. | 100% |

| 14 | The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and >2 exacerbations per year requiring IV antibiotics or 1 exacerbation requiring positive pressure ventilation regardless of FEV1. | 100% |

| 15 | The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and massive hemoptysis (>240mL) requiring ICU admission or bronchial artery embolization. | 100% |

| 16 | The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and pneumothorax. | 100% |

| 17 | For females with CF, especially those who are younger, the CF Foundation recommends special consideration for lung transplant referral even when other thresholds have not been met. | 100% |

| 18 | For individuals with short stature (height less than 162 cm), the CF Foundation recommends special consideration for lung transplant referral even when other thresholds have not been met. | 100% |

| 19 | The CF Foundation recommends CF clinician consultation with local and geographically distant lung transplant centers for individuals with microorganisms that may pose a risk for lung transplantation (e.g. Burkholderia cepacia complex, nontuberculous mycobacterium, certain molds such as scedosporium). | 100% |

| 20 | Before determining that an individual is not a transplant candidate the CF Foundation recommends consultation with at least two transplant centers, one of which should have experience addressing the individual’s potential contraindications to transplantation. | 100% |

| 21 | For transplant candidates, the CF Foundation recommends communication between the CF and lung transplant care teams at least every 6 months and with major clinical changes. | 100% |

-

1

The CF Foundation recommends routine clinician-led efforts to discuss disease trajectory and treatment options, including a discussion of lung transplantation.

For individuals with CF and ALD, LTx confers a survival benefit [6] and post-transplant survival is increasing, with the current International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry report documenting 9.5 years median survival among adults with CF [7]. Therefore, periodic discussion of LTx is recommended to help destigmatize the procedure. Discussing LTx with individuals with normal lung function or only mildly reduced forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) should be seen as a form of anticipatory guidance for individuals and their families. The routine discussion of LTx can include an acknowledgement that the individual does not require transplant, which may relieve unspoken anxiety. Numerous members of the focus group noted that early introduction and normalization of LTx facilitated a more effective transition/referral process. In contrast, when LTx was introduced in the context of clinical deterioration, it was associated with increased fear, denial, and potential delay and/or avoidance of important clinical elements of care. Many focus group members characterized their impressions of LTx as ‘a death sentence’, ‘the beginning of the end’, or with similarly negative connotations, despite the improving post-transplant survival outcomes (Table 3). It was also noted in the focus group that individuals’ feelings toward transplant strongly mirrored that of their physician(s). For example, a strong association was noted between physicians who reportedly exhibited a negative bias towards transplant and individuals who felt fear, anxiety, and a sense of personal failure. In contrast, individuals that reported having physicians who regarded transplant more positively, and who approached transplant as a treatment option that extends life for end-stage CF, felt more informed, confident, and optimistic about their future quality of life. Several specific recommendations in the consensus guidelines may help accomplish the broader goal to destigmatize discussion of LTx, including earlier physician-patient discussions of LTx as a treatment option for end-stage CF, the use of up-to-date sources of information related to LTx [8, 9], and alternative discussion points for clinicians (Table 3). Discussion of disease trajectory and treatment options serves as an opportunity to discuss treatment goals, which would inevitably include the possibility of LTx [10, 11].

Table 3:

Focus group-derived themes and considerations for communication with individuals with cystic fibrosis

| Thematic Domain | Provider Exemplars from Focus Group | Effective Alternative Exemplars for Clinicians |

| Destigmatize the need for lung transplantation |

|

|

| Eliciting and addressing CF- related concerns and outcomes |

|

|

| Addressing transplant-related expectations |

|

|

-

2

The CF Foundation recommends CF care team initiated discussion regarding lung transplantation with all individuals with CF and an FEV1 less than 50% predicted.

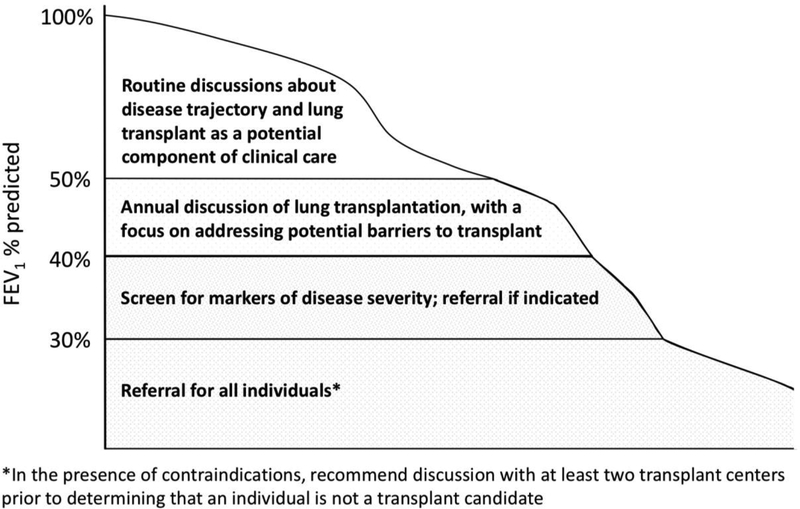

While many studies have demonstrated an association between FEV1 and mortality [12–18], FEV1 is an imperfect marker of disease severity. Survival with low lung function is improving, and some individuals with CF live for many years with severely reduced lung function while others die quickly following a decline in FEV1 [1, 12, 19, 20]. Determining which FEV1 (best, worst, “baseline”, or during an exacerbation) should prompt action is challenging. Expert consensus concluded that an FEV1 <50% predicted, regardless of the context, should prompt discussion of LTx as a potential therapeutic option (Figure 1). This discussion serves as an opportunity to identify barriers to LTx, to clarify the individual’s goals of care (Table 4) and could be reasonably broached by any member of the care team. Some potential barriers to LTx could require years of work to correct in order for an individual to become an acceptable candidate – early discussion may permit this opportunity.

Figure 1: Lung function thresholds for discussion of lung transplantation and timing of lung transplant referral.

Table 4:

Clinical and educational milestones for lung transplant referral

| At diagnosis of CF and throughout the life-span |

|

| When lung function declines to FEV1 <50% predicted |

|

| When lung function declines to FEV1 <40% predicted |

|

| When lung function declines to FEV1 <30% predicted |

|

| Modifiable barriers to lung transplantation |

|

| Special considerations |

|

The following may impact lung transplantation candidacy depending on transplant center-specific practices:

| |

| Decision to initiate lung transplant referral |

|

| Decision to defer listing |

|

| Decision to list for transplant |

|

-

3

The CF Foundation recommends the use of up-to-date CF-specific transplant resources to promote understanding of the transplant journey and to minimize misconceptions regarding outcomes.

Individuals with CF and their families should have access to contemporary, CF-specific information regarding LTx in order to optimize their understanding of potential transplant outcomes. These data can be found on the websites of several organizations, including the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF.org), the ISHLT (ishlt.org), the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR.org), and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) (unos.org). The annual ISHLT Registry Report provides international disease-specific survival statistics and other clinical outcomes data. Many transplant centers have institutional websites that describe local practices and provide contact information for the transplant team. Decision aids or other technology-based sources of information could be useful to highlight misconceptions/misunderstandings and facilitate an accurate fund of knowledge regarding LTx [21–24]. Another potential resource is connecting people with CF with individuals who have undergone LTx to address concerns regarding transplantation [9].

-

4The CF Foundation recommends that CF clinicians develop relationships with peers at partnering transplant centers to:

- optimize the transition to transplant, starting with referral

- understand transplant center-specific practices, including navigating complex socioeconomic barriers to transplant

- maintain ongoing communication about clinical status of individuals listed or approaching transplant listing

Identifying peers at partnering transplant centers allows for improved communication and facilitates continuity of care. CF care teams can deliver the best care to individuals at their home CF Center when they are aware of the partnering lung transplant center’s practices. Clear communication of the necessary medical information at the time of transplant referral will streamline the process and increase efficiency for both teams (see CFF.org for a transplant referral form template). CF teams should develop an understanding of the partnering transplant centers’ approach to multiple organ transplantation (e.g. lung/liver, lung/kidney) and preferred timing of referral in those cases. Maintaining a relationship between the CF team and partnering transplant team allows for a smooth transplant referral and ongoing co-management of individuals in the pre-transplant phase. CF providers, including all members of the CF care team, can reinforce the importance of ongoing work by the individuals with CF and caregivers to address outstanding concerns. Having connections at multiple transplant centers may be valuable in the setting of insurance limitations and the widely varying practices and requirements of lung transplant programs across the United States (US).

-

5

The CF Foundation recommends that the individual’s CF care team elicit and address CF-specific psychosocial and physical concerns about lung transplantation to facilitate transition to transplant.

Numerous psychosocial, physical, and care-related concerns emerged from the focus group as being particularly salient among individuals with CF. Increased complexity of care, the potential for decentralization of care (leaving the CF center), worsening impairments in quality of life at a young age, the potential loss of CF identity, concerns regarding family planning, relationship issues, and education/career could influence their approach to the transplant process [25]. There is decreased access to referral, listing and LTx for individuals with CF and lower socioeconomic status [26, 27]. Geographic disparities in access to LTx are an important consideration for people with CF [26]. A recent study demonstrated increased risk of death without LTx and a younger age at death for Hispanic individuals with CF [28]. Providing psychosocial support to individuals with CF during the transition requires an understanding of these (and other) CF-specific psychosocial concerns. Care and assistance from family is vital for individuals on the transplant journey. LTx teams also need to acknowledge and address CF-specific concerns related to transplant, as some issues may persist post-transplant.

-

6

The CF Foundation recommends that modifiable barriers to lung transplantation be addressed preemptively to optimize transplant candidacy; however, unresolved barriers should not preclude referral. Potentially modifiable barriers may include but are not limited to: nutritional status, diabetes management, physical inactivity or deconditioning, adherence behaviors, mental health issues, substance use, and psychosocial factors.

The number of individuals with CF who die each year without lung transplant referral remains significant [1]. A survey of physicians in the US demonstrated that potentially modifiable barriers are a frequent reason for non-referral [29]. Modifiable barriers to transplant should be identified preemptively in CF clinic, potentially years prior to the need for LTx, but these do not need to be fully resolved prior to a referral (Table 4). Learning about barriers to transplant directly from the transplant team serves to reinforce the messages given by the CF team and may prompt increased effort on behalf of the individual with CF to correct these concerns so that transplant may be an option. Transplant providers can articulate how these issues specifically affect their transplant candidacy and provide tools and motivation to address these barriers.

The transplant team can provide center-specific education for individuals with CF and their families. The transplant program can assess barriers in the context of transplant candidacy as a whole, and determine exactly what progress needs to be made in order for someone to become an acceptable candidate for transplant. Additionally, non-medical barriers to LTx, including insurance status, geography, finances, medical literacy, and limited social support, may influence not only when to refer for transplant, but also where to refer. Certain psychosocial factors may take years of work in order to optimize a candidate for lung transplant.

-

7

The CF Foundation recommends the CF and lung transplant care teams acknowledge and provide support for mental health concerns regarding the referral and evaluation process for transplant that are unique to individuals with CF.

Many focus group members noted that the idea of requiring LTx may elicit reflexive, internal attributions that the need for transplant reflects a failure of their own adherence behaviors. Because the importance of adherence-related behaviors is often underscored for many individuals with CF and their families, and these behaviors are often integrally tied to clinical outcomes, this implicit association may inadvertently elicit feelings of shame [30, 31] or stigma [32]. For example, many individuals in the focus group characterized coping styles that would ‘fight’ or ‘beat’ CF through vigilant adherence behaviors [33–35]. Care teams are encouraged to identify and address individuals’ negative self-directed emotions because they can lead to avoidance of clinical interactions and delay the receipt of appropriate care [36, 37]. Mental health concerns, such as depression and anxiety, should also be assessed through routine screening at least annually and formal mental health treatment should be considered if indicated [38]. For most transplant centers, management of common mental health concerns using psychotropic medications is not a contraindication for transplantation and may optimize an individual’s ability to cope during a period of greater distress and worsening quality of life. In addition, providers should be aware that the introduction of uncertainty about patients’ eligibility for LTx may serve to increase ambivalence and ultimately avoidance of transplant-related knowledge or health decisions [39, 40]. Moreover, depression and anxiety are common among individuals with CF [38] and, if persistent and inadequately treated, may adversely impact LTx outcomes [41, 42].

-

8For individuals with CF who are 18 years of age and older, the CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral no later than when:

- FEV1 is <50% predicted and rapidly declining (>20% relative decline in FEV1 within 12 months)

OR

FEV1 is <40% predicted with markers of shortened survival (including those noted in recommendations #12–16)

OR

FEV1 is <30% predicted

Because FEV1 is associated with mortality [12–18], FEV1 thresholds were identified to prompt further action, including evaluation for markers of shortened survival and/or lung transplant referral. Markers of shortened survival include low FEV1, 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance <400 meters, room air hypoxemia (SpO2 <88% or PaO2 <55 mmHg, at rest or with exertion; at sea level), hypercarbia (PaCO2 >50 mmHg, confirmed on arterial blood gas), pulmonary hypertension (PA systolic pressure >50 mmHg on echocardiogram or evidence of right ventricular dysfunction in the absence of a tricuspid regurgitant jet), BMI <18 kg/m2 for adults (or BMI less than 5th percentile for children), increased frequency of pulmonary exacerbations (>2 exacerbations per year requiring IV antibiotics or one exacerbation requiring positive pressure ventilation), massive hemoptysis, or pneumothorax [1, 12–19, 25, 43, 44]. Additionally, a low physical functioning score on the CFQ-R questionnaire has been associated with reduced survival and, while there was no consensus recommendation for use of CFQ-R in routine clinical practice, a Physical score <30 could be considered alongside other markers of shortened survival in the decision to refer for transplant [44, 45].

Although FEV1 alone should not determine timing of lung transplant referral, referral should occur no later than when the non-exacerbation (“stable”) FEV1 is <30% predicted. Among individuals with a “stable” FEV1 <30% predicted in the US, approximately 10% die without LTx each year after reaching this threshold [1]. For individuals with frequent exacerbations, it may be difficult to assess a “stable” FEV1, but these individuals may benefit from referral (see recommendation #14). Rapidly declining FEV1 has been shown to predict death without LTx [19, 46, 47]. A recent study of a sample of individuals with CF who died in the US found that 38% had a documented “highest” FEV1 that was greater than 40% in the year prior to death, highlighting that a rapid decline in FEV1 may precede death for many individuals with CF [48]. Recommendations #12–16 identify individuals with risk profiles highlighted in published prognostic models [12, 14–18].

-

9For individuals with CF who are under the age of 18 years, the CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral no later than when:

- FEV1 is <50% predicted and rapidly declining (>20% relative decline in FEV1 within 12 months)

OR

FEV1 is <50% predicted with markers of shortened survival (including those noted in recommendations #12–16)

OR

FEV1 is <40% predicted

Individuals with CF frequently transition to adulthood with FEV1 in the normal or only mildly impaired range, with only 5% of 18 year olds having ALD (FEV1 <40%) in 2015 [49]. Children with CF tend to have reduced survival compared to adults with the same FEV1 % predicted. For this reason, expert consensus was that children with CF (under age 18 years) should be referred for LTx at an earlier FEV1 threshold than the average adult individual [46]. For children with markers of increased disease severity (including those noted in recommendations #12–16) consideration for referral prior to the FEV1 <40% threshold is recommended. Referral at a higher FEV1 threshold for this younger population gives more time to address modifiable barriers. Additionally, there are a limited number of transplant centers with pediatric experience, which further contributes to the need for early referral in order to gain insurance approvals and access to these centers.

-

10

For individuals with CF and an FEV1 <40% predicted, the CF Foundation recommends an annual 6-minute walk test (6MWT), assessment of need for supplemental oxygen, and venous blood gas to screen for markers of severe disease that may warrant transplant referral.

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance is used regularly in Canada, Ireland and other parts of the world to assess the clinical status of individuals with advanced/deteriorating CF-related lung disease [50, 51]. Expert consensus was that annual testing with a 6MWT, an assessment for supplemental oxygen requirement, and venous blood gas (VBG) would provide clinically meaningful data for patients with ALD, based on a “stable” FEV1 <40% predicted (Table 5). Assessment for supplemental oxygen requirement (SpO2 <88% or PaO2 <55 mmHg) should occur at rest, with exertion, and during sleep [12, 52–54]. An annual VBG should be used to screen for hypercarbia, and if PvCO2 is elevated (PvCO2 >56 mmHg), a confirmatory arterial blood gas (ABG) should be obtained. In the pediatric population, begin to perform testing when the “stable” FEV1 <50% predicted (Table 5).

Table 5:

Committee’s consensus for testing recommendations for individuals with FEV1 <40% (adults) or FEV1 <50% (pediatrics)

| Test | Action |

|---|---|

| 6-minute walk test | Annual evaluation |

| Venous blood gas | Annual evaluation |

| Echocardiogram | Assess baseline estimate of pulmonary pressure |

-

11

For individuals with CF who are 18 years of age and older with FEV1 <40% predicted, the CF Foundation recommends a baseline echocardiogram to screen for pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension is common in individuals with advanced CF-related lung disease [43, 54–57], but its presence is rarely identified prior to evaluation for LTx. Repeat echocardiogram should be considered for individuals with worsening clinical status. In the pediatric population, perform baseline echocardiogram when the FEV1 is <50% predicted.

-

12The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral, regardless of FEV1, when there are markers of shortened survival, including:

- 6MWT distance <400 meters

OR

hypoxemia (at rest or with exertion)

OR

hypercarbia (PaCO2 >50 mmHg, confirmed on arterial blood gas)

OR

pulmonary hypertension (PA systolic pressure >50 mmHg on echocardiogram or evidence of right ventricular dysfunction in the absence of a tricuspid regurgitant jet)

Adults with “stable” FEV1 greater than 40% predicted are unlikely to have these data available unless their respiratory symptoms are out of proportion to their FEV1.

The 6MWT distance is associated with death or LTx for individuals with CF [56, 58–60]. The ISHLT recommends referral for LTx evaluation when the 6MWT distance is less than 400 meters [61]. Although a sub-maximal exercise test for a majority of individuals with CF, the 6MWT is a marker of functional status and may better reflect limitations experienced by individuals with ALD than the FEV1 alone.

Supplemental oxygen requirement and/or low PaO2 have been repeatedly associated with death without LTx for individuals with CF [1, 12, 52, 53, 56, 62]. Hypercarbia is a known predictor of death in individuals with CF [12, 16, 54, 63]. Pulmonary hypertension has been associated with death without lung transplant [64–66], but echocardiograms are imperfect at determining the severity of pulmonary hypertension in patients with ALD and may identify “false positive” cases [67, 68]. In an individual with FEV1 <40% whose only marker of increased disease severity is an elevated PA systolic pressure (>50 mmHg), a confirmatory right heart catheterization may be warranted prior to transplant referral.

-

13

The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for adults with CF with a BMI <18 and FEV1 <40% predicted while concurrently working to improve nutritional status.

Studies have shown low BMI is a risk factor for death without lung transplantation [1, 14, 15, 18, 69, 70] and it should be considered a marker of urgency for lung transplant referral. Additionally, the trajectory of the BMI (e.g. rapidly declining) is clinically meaningful and may affect timing of referral. Minimum BMI thresholds vary from center to center in the US and low BMI should be proactively addressed (see Enteral Tube Feeding Guidelines) [71] as a modifiable barrier to transplant. While a specific BMI cutoff is not useful for defining malnutrition in the pediatric population and a weight-for-age >10th percentile is a common goal [72], malnutrition (e.g. BMI less than 5th percentile for children) is an important modifiable barrier to lung transplantation for children with CF [73] and should be addressed concurrently with LTx referral for children with ALD.

-

14

The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and >2 exacerbations per year requiring IV antibiotics or 1 exacerbation requiring positive pressure ventilation regardless of FEV1.

Increasing number of pulmonary exacerbations is associated with death without transplant among individuals with ALD, with risk increased in the setting of 1 or more courses of IV antibiotics [1, 13, 17, 18, 74] or the need for hospitalization [14, 15, 17, 18, 52]. The presence of acute hypercapnic or hypoxemic respiratory failure, or chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure necessitating positive pressure ventilation (e.g. noninvasive or invasive ventilatory support), in the hospital or home setting, should prompt referral for LTx regardless of FEV1.

-

15

The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and massive hemoptysis (>240mL) requiring ICU admission or bronchial artery embolization.

Hemoptysis increases the risk for death or LTx [75, 76]. There may be an increased risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure and death following bronchial artery embolization among individuals with ALD [77]. It is expert consensus that among individuals with CF and FEV1 between 30% and 40% predicted, an episode of hemoptysis leading to ICU admission and/or bronchial artery embolization should prompt referral for LTx evaluation. Individuals referred for hemoptysis may have risk that is not captured in the lung allocation score (LAS), and massive hemoptysis may occur without warning, potentially prompting lung transplant centers to request an exception to the LAS. Additionally, individuals with CF and FEV1 >40% may also warrant LTx evaluation if episodes of hemoptysis are frequent and severe.

-

16

The CF Foundation recommends lung transplant referral for individuals with FEV1 <40% predicted and pneumothorax.

The occurrence of pneumothorax is more frequent among individuals with CF and severe pulmonary impairment (FEV1 <40%) and older age. Pneumothorax leads to an increased number of hospitalizations and number of days spent in the hospital, and an increase in 2-year mortality [78, 79]. Recurrent pneumothorax is an indication for referral for LTx in the ISHLT recommendations for individuals with CF [61]. Furthermore, consultation with a transplant surgeon at a partnering center is recommended prior to non-urgent treatment of pneumothorax (e.g. surgical or medical pleurodesis), as these interventions may impact surgical planning for LTx.

-

17

For females with CF, especially those who are younger, the CF Foundation recommends special consideration for lung transplant referral even when other thresholds have not been met.

There is a persistent gender gap in survival for individuals with CF [1, 12–15, 62, 80, 81] and this recommendation aims to focus providers on the increased risk of death for females with CF. The increased risk of death for females is limited to the pre-transplant setting, as post-transplant survival is not worse for females compared to males with CF [80]. Special consideration for LTx referral is recommended for females who are younger, have CF-related diabetes, rapidly declining FEV1, or rapidly declining BMI.

-

18

For individuals with short stature (height less than 162 cm), the CF Foundation recommends special consideration for lung transplant referral even when other thresholds have not been met.

Individuals with shorter stature (under 162 cm) have an increased risk of death on the lung transplant waitlist [82, 83]. This disadvantage is at least partially explained by the difficulties in finding donor lungs of the correct size and is of particular importance among pediatric lung transplant candidates. This recommendation aims to focus CF providers on the potential for a long wait time and the need for early referral of shorter individuals with CF.

-

19

The CF Foundation recommends CF clinician consultation with local and geographically distant lung transplant centers for individuals with microorganisms that may pose a risk for lung transplantation (e.g. Burkholderia cepacia complex, nontuberculous mycobacterium, certain molds such as scedosporium).

Infection with certain microorganisms (e.g. Burkholderia cepacia complex, nontuberculous mycobacterium, molds such as scedosporium, multi-drug resistant or increasingly resistant microorganisms) is associated with worse outcomes following lung transplantation [18, 61, 84–89]. These microorganisms may be considered absolute contraindications at some transplant programs and acceptable at others based on program experience and risk aversion. Similarly, infection with a particular organism may not in and of itself be considered an absolute contraindication by a program, but if combined with other risk factors, may be a reason an individual is declined for LTx. Institution-specific microbiological contraindications shift over time, so it is important not to make assumptions about transplant candidacy based on prior practice.

-

20

Before determining that an individual is not a transplant candidate the CF Foundation recommends consultation with at least two transplant centers, one of which should have experience addressing the individual’s potential contraindications to transplantation.

While there are established international consensus recommendations for the selection of lung transplant candidates, published by the ISHLT [61], each lung transplant program has developed its own specific criteria for transplant candidacy and listing. Individuals who are declined at one transplant center may be deemed suitable at another center. In the US, criteria differ widely based on institutional experience, resources and risk thresholds. In particular, some high-volume lung transplant programs will consider individuals with renal or liver disease (potentially for multi-organ transplant) or pathogenic microorganisms that are considered absolute contraindications at other programs. Transplant center practices evolve over time, so communicating with multiple transplant programs maximizes access to current practice. Once a candidate has been denied transplant by the insurance provider’s preferred transplant center, an appeal can often result in that person being granted access to a center that will consider the individual as an appropriate candidate. While it may be financially infeasible for an individual to travel to a geographically distant transplant center, it is important to consider this option for those who are declined for LTx locally. Consultation (Table 1) with a transplant center with experience addressing an individual’s potential contraindications to LTx would inform the individual, and the CF care team, without necessarily involving an in-person visit to the center. The US has a unique healthcare system, with more than 60 lung transplant centers, and this recommendation may not easily generalize to countries with fewer transplant centers.

-

21

For transplant candidates, the CF Foundation recommends communication between the CF and lung transplant care teams at least every 6 months and with major clinical changes.

Early referral for LTx allows individuals with CF to establish a relationship with the transplant team, obtain transplant specific education, and identify and modify barriers to transplant. For individuals with CF deemed “too early” for listing, ongoing communication at set time intervals will allow for continued assessment of disease progression (e.g. development of markers of increased disease severity noted in recommendations #12–16; significant clinical events) and readiness for transplant. Significant clinical events include, but are not limited to: exacerbation requiring IV antibiotics (especially if increasing in frequency), hospitalization, increase in oxygen requirement, non-invasive positive pressure or mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, new CF-related diabetes, new sputum microbiology (e.g. new Burkholderia or nontuberculous mycobacterium), significant decline in 6MWT or FEV1. It is beneficial for all members of the interdisciplinary team (social worker, mental health coordinator, dietician, physical therapist, respiratory therapist and nurse coordinator) to share information affecting an individual’s candidacy with their counterparts as different information is disclosed to different team members.

For individuals deferred due to barriers, communication should highlight progress toward addressing barriers to transplant. It is critical for the transplant team to be aware of changes in clinical status, which may affect transplant candidacy as well as timing for listing. Open lines of communication between the CF and lung transplant care teams regarding patients who are listed or approaching listing are vital if an individual has a sudden deterioration. Geographic and program-specific donor availability and waitlist times may influence the timing of listing. Further, certain characteristics such as height, chest cavity size, ABO blood type and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) sensitization may result in challenges finding a suitable donor and impact timing for listing. Finally, local lung transplant center practices will necessarily influence how CF providers interpret and implement these consensus recommendations.

International Considerations

Outside of the US, there is a broadly similar experience with delays in referral for LTx. Both European [2] and Australian [90] studies show that many individuals die without receiving LTx. It is likely that similar barriers to LTx seen in the US exist in many countries and guidelines for timely referral for lung transplant assessment are welcome. In addition to the barriers outlined earlier in this statement, there are a number of unique challenges in Europe as many of the smaller European countries do not have a transplant program and must refer to neighboring countries. This leads to further barriers such as inability of very sick individuals to travel (often significant distances by air), language and cultural difficulties throughout the transplant process, and complexities of cross-country funding and follow-up. Even in countries with well-established programs, many individuals with CF die without receiving LTx [2]. In the UK, in a recent survey of 28 specialty CF centers [91] 22% of respondents expressed concerns that LTx was discussed with patients too late and 19% expressed concerns that individuals with CF were referred for transplant assessment too late. Barriers to referral in the UK included patient refusal, poor-adherence and psychological readiness as well as unexpected rapid clinical deterioration or the presence of significant comorbidities/infections that could preclude transplant. In France, with a well-developed National Lung Transplant Program, including the introduction of an emergency transplant program in 2007, 50% of all CF deaths occur without lung transplantation of which 72% had at least one indication for transplant and were not on the active transplant list [2]. Although the majority of these individuals were in the process of lung transplant assessment or had been declined for LTx, 39% of these potentially eligible individuals with CF had never been considered for transplant [2]. A subsequent survey of French centers [92] proposed an earlier structured approach to transplant assessment including improved patient and caregiver education and earlier discussions of transplant options. These studies, in countries with well-established transplant programs and specialized CF centers, highlight that transplant referral challenges are worldwide and that barriers to early referral need to be identified and overcome.

Potential Impact of CFTR Modulators

Consideration of the effect of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulator therapy on these consensus guideline recommendations is important because there is growing evidence that CFTR modulators improve outcomes for a majority of individuals with CF [93–96] and may deliver a sustained benefit over time [97]. While CFTR modulators may change the trajectory of lung function decline, for the foreseeable future there will be many individuals with CF and ALD. There is no data describing survival with ALD in the era of highly-effective CFTR modulator therapy. In the setting of markers of increased disease severity (e.g. FEV1 <30% predicted, or those noted in recommendations #12–16) these consensus guidelines should guide discussions about LTx and decisions about the timing of referral. LTx referral should not be delayed based on anticipated availability or effect of current or future CFTR modulators.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Survival for individuals with CF has improved dramatically over the past few decades and this improvement is expected to accelerate with new agents that address the cellular defect in CF. Nevertheless, the majority of individuals with CF still eventually succumb to their lung disease. LTx has the potential to extend survival for individuals with CF. Despite this fact, evidence indicates that many individuals with CF who die from respiratory disease are never referred for transplant [2, 27]. Presumably, some deaths may have been prevented if LTx had been considered and a referral made. Available data suggests the reasons for non-referral may not be due to absolute contraindications to transplant [2, 29]. Research on factors contributing to lack of transplant referral for individuals with CF and FEV1 <30% or those with higher lung function who die of respiratory disease is warranted. There is a potential application for quality improvement methodology to improve the LTx referral process in a systematic manner.

These guidelines are intended to help CF providers appropriately counsel their patients about LTx and decrease the number of individuals with CF who die from lung disease without consideration of LTx. The journey through referral, evaluation, listing and transplantation is fraught with physical and psychosocial challenges for the individual and their family. LTx requires careful consideration and is not the right therapy for all individuals with advanced CF-related lung disease. It is the responsibility of both the CF and the transplant teams to provide support through this process. Many of the barriers to LTx can be overcome if identified and addressed early enough in the course of the disease to permit adequate time for resolution. While data are limited, there is a growing body of literature to support the use of FEV1 combined with other physiologic parameters including pulmonary artery pressure, blood gas (to detect hypoxemia or hypercarbia), trajectory of lung function and nutritional status to determine appropriate timing of referral and listing for transplant. While most individuals who meet these Consensus Guidelines’ criteria for referral will be too early for listing, it is important to recognize that referral does not necessarily prompt a full evaluation or listing, but instead gives individuals with CF, their families, and providers access to the expertise of the LTx team and the opportunity to fully consider LTx as a treatment option. The individual with CF will then have sufficient information to make a decision if the need for LTx arises.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Annual discussion of lung transplant is recommended for individuals with FEV1 <50%

Screen for markers of increased disease severity & modifiable barriers to transplant

Early referral for lung transplant is essential to optimize access and outcomes

Refer all adults with CF when FEV1<30% predicted, sooner if other severity indicators

US transplant center practices vary; consultation with >1 center may be necessary

Acknowledgements:

The authors and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation would like to thank the members of the focus group of CF transplant recipients and spouses of CF recipients who were instrumental in setting the tone for these Lung Transplant Referral Consensus Guidelines. The focus group included: Heather McCoy, Kasey Seymor, Tyler Patterson, Jennifer Staashelm, Lindsay Bishop, John Roddy, Scott Hastie, and Fanny Vlahos.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests statement: funding for KJR includes: NIH (K23HL138154) and CF Foundation (RAMOS17A0; LEASE16A3) grants; no other relevant sources of financial support or conflicts of interest identified for the authors

References

- 1.Ramos KJ, Quon BS, Heltshe SL, Mayer-Hamblett N, Lease ED, Aitken ML, Weiss NS, Goss CH: Heterogeneity in Survival in Adult Patients With Cystic Fibrosis With FEV1 < 30% of Predicted in the United States. Chest 2017, 151(6):1320–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin C, Hamard C, Kanaan R, Boussaud V, Grenet D, Abely M, Hubert D, Munck A, Lemonnier L, Burgel PR: Causes of death in French cystic fibrosis patients: The need for improvement in transplantation referral strategies! J Cyst Fibros 2016, 15(2):204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun AT, Dasenbrook EC, Shah AS, Orens JB, Merlo CA: Impact of lung allocation score on survival in cystic fibrosis lung transplant recipients. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation 2015, 34(11):1436–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong A, Chapman JR, Israni A, Gordon EJ, Craig JC: Qualitative research in organ transplantation: recent contributions to clinical care and policy. Am J Transplant 2013, 13(6):1390–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour RS: The role of qualitative research in broadening the ‘evidence base’ for clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2000, 6(2):155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thabut G, Christie JD, Mal H, Fournier M, Brugière O, Leseche G, Castier Y, Rizopoulos D: Survival benefit of lung transplant for cystic fibrosis since lung allocation score implementation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2013, 187(12):1335–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb SB, Hayes D, Kucheryavaya AY, Toll AE, Khush KK, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW: The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2018; Focus theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2018, 37(10):1169–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skelton SL, Waterman AD, Davis LA, Peipert JD, Fish AF: Applying best practices to designing patient education for patients with end-stage renal disease pursuing kidney transplant. Prog Transplant 2015, 25(1):77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, Morgievich M, Cohen DJ, Butt Z, Chakkera HA, Lindower C, Hays RE, Hiller JM, Lentine KL, Matas AJ et al. : Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: Improving Education Outside of Transplant Centers about Live Donor Transplantation--Recommendations from a Consensus Conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 10(9):1659–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song M-K, Dabbs AJDV: Advance care planning after lung transplantation: a case of missed opportunities. Progress in Transplantation 2006, 16(3):222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellon EP, Chen E, Goggin J, Homa K, Marshall BC, Sabadosa KA, Cohen RI: Advance care planning in cystic fibrosis: current practices, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2016, 15(1):96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerem E, Reisman J, Corey M, Canny GJ, Levison H: Prediction of mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1992, 326(18):1187–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liou TG, Adler FR, Fitzsimmons SC, Cahill BC, Hibbs JR, Marshall BC: Predictive 5-year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol 2001, 153(4):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaron SD, Stephenson AL, Cameron DW, Whitmore GA: A statistical model to predict one-year risk of death in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Epidemiol 2015, 68(11):1336–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson AL, Tom M, Berthiaume Y, Singer LG, Aaron SD, Whitmore GA, Stanojevic S: A contemporary survival analysis of individuals with cystic fibrosis: a cohort study. Eur Respir J 2015, 45(3):670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belkin RA, Henig NR, Singer LG, Chaparro C, Rubenstein RC, Xie SX, Yee JY, Kotloff RM, Lipson DA, Bunin GR: Risk factors for death of patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 173(6):659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer-Hamblett N, Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Goss CH, Aitken ML: Developing cystic fibrosis lung transplant referral criteria using predictors of 2-year mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166(12 Pt 1):1550–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkam L, Lambert J, Latouche A, Bellis G, Burgel PR, Hocine MN: A 3-year prognostic score for adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2017, 16(6):702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milla CE, Warwick WJ: Risk of death in cystic fibrosis patients with severely compromised lung function. Chest 1998, 113(5):1230–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George P, Banya W, Pareek N, Bilton D, Cullinan P, Hodson M, Simmonds N: Improved survival at low lung function in cystic fibrosis: cohort study from 1990 to 2007. Bmj 2011, 342:d1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandemheen KL, O’connor A, Bell SC, Freitag A, Bye P, Jeanneret A, Berthiaume Y, Brown N, Wilcox P, Ryan G: Randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with cystic fibrosis considering lung transplantation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2009, 180(8):761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain A, Corriveau S, Quinn K, Gardhouse A, Vegas DB, You JJ: Video decision aids to assist with advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open 2015, 5(6):e007491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacey D, Vandemheen KL, Hennessey R, Gooyers T, Gaudet E, Mallick R, Salgado J, Freitag A, Berthiaume Y, Brown N: Implementation of a cystic fibrosis lung transplant referral patient decision aid in routine clinical practice: an observational study. Implementation Science 2015, 10(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB: Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. HEALTH AFFAIRS-MILLWOOD VA THEN BETHESDA MA- 2004, 23,VAR-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castellani C, Duff AJ, Bell SC, Heijerman HG, Munck A, Ratjen F, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Southern KW, Barben J, Flume PA: ECFS best practice guidelines: the 2018 revision. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quon BS, Psoter K, Mayer-Hamblett N, Aitken ML, Li CI, Goss CH: Disparities in access to lung transplantation for patients with cystic fibrosis by socioeconomic status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 186(10):1008–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos KJ, Quon BS, Psoter KJ, Lease ED, Mayer-Hamblett N, Aitken ML, Goss CH: Predictors of non-referral of patients with cystic fibrosis for lung transplant evaluation in the United States. J Cyst Fibros 2016, 15(2):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rho J, Ahn C, Gao A, Sawicki GS, Keller A, Jain R: Disparities in Mortality of Hispanic Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the United States: A National and Regional Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos KJ, Somayaji R, Lease ED, Goss CH, Aitken ML: Cystic fibrosis physicians’ perspectives on the timing of referral for lung transplant evaluation: a survey of physicians in the United States. BMC Pulm Med 2017, 17(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolezal L: The phenomenology of shame in the clinical encounter. Med Health Care Philos 2015, 18(4):567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CR DRHNH: Reactions to Physcian-Inspired Shame and Guilt. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2014, 36:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliver KN, Free ML, Bok C, McCoy KS, Lemanek KL, Emery CF: Stigma and optimism in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2014, 13(6):737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott J, Hart A, Morton A, Gee L, Conway S: Health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis: the role of coping. J Psychosom Res 2008, 64(2):149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbott J: Coping with cystic fibrosis. J R Soc Med 2003, 96 Suppl 43:42–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor JL, Smith PJ, Babyak MA, Barbour KA, Hoffman BM, Sebring DL, Davis RD, Palmer SM, Keefe FJ, Carney RM et al. : Coping and quality of life in patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Psychosom Res 2008, 65(1):71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller SM, Shoda Y, Hurley K: Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychol Bull 1996, 119(1):70–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.RS HCD: Shame in Physician-Patient interactions: Patient Perspectives. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2009, 31:325–334. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quittner AL, Abbott J, Georgiopoulos AM, Goldbeck L, Smith B, Hempstead SE, Marshall B, Sabadosa KA, Elborn S, International Committee on Mental H et al. : International Committee on Mental Health in Cystic Fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus statements for screening and treating depression and anxiety. Thorax 2016, 71(1):26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han PK, Moser RP, Klein WM: Perceived ambiguity about cancer prevention recommendations: relationship to perceptions of cancer preventability, risk, and worry. J Health Commun 2006, 11 Suppl 1:51–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portnoy DB, Han PK, Ferrer RA, Klein WM, Clauser SB: Physicians’ attitudes about communicating and managing scientific uncertainty differ by perceived ambiguity aversion of their patients. Health Expect 2013, 16(4):362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F, Grady KL, Jowsey-Gregoire SG, Kaan A, Kendall K, Young QR, Abbey SE, Butt Z et al. : The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018, 37(7):803–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Freedland KE, O’Hayer CVF, Trulock EP, Martinu T, Schwartz TA, Hoffman BM, Koch GG et al. : Neurobehavioral functioning and survival following lung transplantation. Chest 2014, 145(3):604–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venuta F, Tonelli AR, Anile M, Diso D, De Giacomo T, Ruberto F, Russo E, Rolla M, Quattrucci S, Rendina EA et al. : Pulmonary hypertension is associated with higher mortality in cystic fibrosis patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirche TO, Knoop C, Hebestreit H, Shimmin D, Solé A, Elborn JS, Ellemunter H, Aurora P, Hogardt M, Wagner TOF: Practical guidelines: lung transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pulmonary medicine 2014, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sole A, Perez I, Vazquez I, Pastor A, Escriva J, Sales G, Hervas D, Glanville AR, Quittner AL: Patient-reported symptoms and functioning as indicators of mortality in advanced cystic fibrosis: A new tool for referral and selection for lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016, 35(6):789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson W, Waltz DA: FEV(1) as a guide to lung transplant referral in young patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2000, 30(3):198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Augarten A, Akons H, Aviram M, Bentur L, Blau H, Picard E, Rivlin J, Miller MS, Katznelson D, Szeinberg A et al. : Prediction of mortality and timing of referral for lung transplantation in cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Transplant 2001, 5(5):339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen E, Homa K, Goggin J, Sabadosa KA, Hempstead S, Marshall BC, Faro A, Dellon EP: End-of-life practice patterns at U.S. adult cystic fibrosis care centers: A national retrospective chart review. J Cyst Fibros 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Registry CFFP: 2015 Annual Data Report. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2016, Bethesda, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 50.K R: Personal Communication with M Solomon. September 2018.

- 51.Ramos K: Personal Communication with E McKone. May 2018.

- 52.Ellaffi M, Vinsonneau C, Coste J, Hubert D, Burgel PR, Dhainaut JF, Dusser D: One-year outcome after severe pulmonary exacerbation in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171(2):158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liou TG, Adler FR, Cox DR, Cahill BC: Lung transplantation and survival in children with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2007, 357(21):2143–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venuta F, Rendina EA, Rocca GD, De Giacomo T, Pugliese F, Ciccone AM, Vizza CD, Coloni GF: Pulmonary hemodynamics contribute to indicate priority for lung transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000, 119(4 Pt 1):682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tonelli AR, Fernandez-Bussy S, Lodhi S, Akindipe OA, Carrie RD, Hamilton K, Mubarak K, Baz MA: Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in end-stage cystic fibrosis and correlation with survival. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010, 29(8):865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vizza CD, Yusen RD, Lynch JP, Fedele F, Alexander Patterson G, Trulock EP: Outcome of patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162(3 Pt 1):819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scarsini R, Prioli MA, Milano EG, Castellani C, Pesarini G, Assael BM, Vassanelli C, Ribichini FL: Hemodynamic predictors of long term survival in end stage cystic fibrosis. Int J Cardiol 2016, 202:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin C, Chapron J, Hubert D, Kanaan R, Honore I, Paillasseur JL, Aubourg F, Dinh-Xuan AT, Dusser D, Fajac I et al. : Prognostic value of six minute walk test in cystic fibrosis adults. Respir Med 2013, 107(12):1881–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kadikar A, Maurer J, Kesten S: The six-minute walk test: a guide to assessment for lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1997, 16(3):313–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ciriaco P, Egan TM, Cairns EL, Thompson JT, Detterbeck FC, Paradowski LJ: Analysis of cystic fibrosis referrals for lung transplantation. Chest 1995, 107(5):1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, Dark JH, Davis RD, Keshavjee S, Lederer DJ, Mulligan MJ, Patterson GA, Singer LG et al. : A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014--an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015, 34(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aurora P, Wade A, Whitmore P, Whitehead B: A model for predicting life expectancy of children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2000, 16(6):1056–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tantisira KG, Systrom DM, Ginns LC: An elevated breathing reserve index at the lactate threshold is a predictor of mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165(12):1629–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayes D Jr., Tumin D, Daniels CJ, McCoy KS, Mansour HM, Tobias JD, Kirkby SE: Pulmonary Artery Pressure and Benefit of Lung Transplantation in Adult Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2016, 101(3):1104–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayes D Jr., Tobias JD, Mansour HM, Kirkby S, McCoy KS, Daniels CJ, Whitson BA: Pulmonary hypertension in cystic fibrosis with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014, 190(8):898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flores JS, Rovedder PM, Ziegler B, Pinotti AF, Barreto SS, Dalcin Pde T: Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Factors in a Cohort of Adults With Cystic Fibrosis: A 7-Year Follow-Up Study. Respir Care 2016, 61(2):192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, Sutton MS, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, Pochettino A, Kotloff RM: Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 167(5):735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E, Housten-Harris T, Champion HC, Girgis RE, Corretti MC, Hassoun PM: Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 179(7):615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vedam H, Moriarty C, Torzillo PJ, McWilliam D, Bye PT: Improved outcomes of patients with cystic fibrosis admitted to the intensive care unit. J Cyst Fibros 2004, 3(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Snell GI, Bennetts K, Bartolo J, Levvey B, Griffiths A, Williams T, Rabinov M: Body mass index as a predictor of survival in adults with cystic fibrosis referred for lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1998, 17(11):1097–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwarzenberg SJ, Hempstead SE, McDonald CM, Powers SW, Wooldridge J, Blair S, Freedman S, Harrington E, Murphy PJ, Palmer L et al. : Enteral tube feeding for individuals with cystic fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation evidence-informed guidelines. J Cyst Fibros 2016, 15(6):724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yen EH, Quinton H, Borowitz D: Better nutritional status in early childhood is associated with improved clinical outcomes and survival in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2013, 162(3):530–535 e531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hulzebos EH, Bomhof-Roordink H, van de Weert-van Leeuwen PB, Twisk JW, Arets HG, van der Ent CK, Takken T: Prediction of mortality in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014, 46(11):2047–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Boer K, Vandemheen KL, Tullis E, Doucette S, Fergusson D, Freitag A, Paterson N, Jackson M, Lougheed MD, Kumar V et al. : Exacerbation frequency and clinical outcomes in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2011, 66(8):680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flume PA, Yankaskas JR, Ebeling M, Hulsey T, Clark LL: Massive hemoptysis in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2005, 128(2):729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vidal V, Therasse E, Berthiaume Y, Bommart S, Giroux MF, Oliva VL, Abrahamowicz M, du Berger R, Jeanneret A, Soulez G: Bronchial artery embolization in adults with cystic fibrosis: impact on the clinical course and survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006, 17(6):953–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Town JA, Aitken ML: Deaths Related to Bronchial Arterial Embolization in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis: Three Cases and an Institutional Review. Chest 2016, 150(4):e93–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Flume PA, Strange C, Ye X, Ebeling M, Hulsey T, Clark LL: Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2005, 128(2):720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spector ML, Stern RC: Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis: a 26-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1989, 47(2):204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raghavan D, Gao A, Ahn C, Kaza V, Finklea J, Torres F, Jain R: Lung transplantation and gender effects on survival of recipients with cystic fibrosis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016, 35(12):1487–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reid DW, Blizzard CL, Shugg DM, Flowers C, Cash C, Greville HM: Changes in cystic fibrosis mortality in Australia, 1979–2005. Med J Aust 2011, 195(7):392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sell JL, Bacchetta M, Goldfarb SB, Park H, Heffernan PV, Robbins HA, Shah L, Raza K, D’Ovidio F, Sonett JR et al. : Short Stature and Access to Lung Transplantation in the United States. A Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 193(6):681–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kourliouros A, Hogg R, Mehew J, Al-Aloul M, Carby M, Lordan JL, Thompson RD, Tsui S, Parmar J: Patient outcomes from time of listing for lung transplantation in the UK: are there disease-specific differences? Thorax 2019, 74(1):60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aris RM, Routh JC, LiPuma JJ, Heath DG, Gilligan PH: Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis patients with Burkholderia cepacia complex. Survival linked to genomovar type. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164(11):2102–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stephenson AL, Sykes J, Berthiaume Y, Singer LG, Aaron SD, Whitmore GA, Stanojevic S: Clinical and demographic factors associated with post-lung transplantation survival in individuals with cystic fibrosis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015, 34(9):1139–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Olland A, Falcoz PE, Kessler R, Massard G: Should cystic fibrosis patients infected with Burkholderia cepacia complex be listed for lung transplantation? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011, 13(6):631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parize P, Boussaud V, Poinsignon V, Sitterle E, Botterel F, Lefeuvre S, Guillemain R, Dannaoui E, Billaud EM: Clinical outcome of cystic fibrosis patients colonized by Scedosporium species following lung transplantation: A single-center 15-year experience. Transpl Infect Dis 2017, 19(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chalermskulrat W, Sood N, Neuringer IP, Hecker TM, Chang L, Rivera MP, Paradowski LJ, Aris RM: Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in end stage cystic fibrosis: implications for lung transplantation. Thorax 2006, 61(6):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stephenson AL, Sykes J, Berthiaume Y, Singer LG, Chaparro C, Aaron SD, Whitmore GA, Stanojevic S: A clinical tool to calculate post-transplant survival using pre-transplant clinical characteristics in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Transplant 2017, 31(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bell SC, Bye P, Cooper PJ, Martin AJ, McKay KO, Robinson PJ, Ryan GF, Sims GCJMJA: Cystic fibrosis in Australia, 2009: results from a data registry. 2011, 195(7):396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.West NE; Francis SJ; Medhurst ND; Thaxton AL; Tallarico E; Cosgriff R; Dunk R; Brownlee KG; Elborn JS; Bush EI; Shah PD; Merlo CA: WS18.2 The transition towards lung transplant for cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2018, 17:S33. [Google Scholar]

- 92.David V; Perrin A; Pougneon-Bertand D; Kanaan R; Kerbrat M; Le Rhun A: WS18.4 Evaluation of transplantation information delivered to patients and their relatives by the professionals from cystic fibrosis centres and transplant centres and from transplanted peer-patients in France. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2018, 17:S33–34. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, Tullis E, Bell SC, Drevinek P, Griese M, McKone EF, Wainwright CE, Konstan MW et al. : A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. The New England journal of medicine 2011, 365(18):1663–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Taylor-Cousar JL, Munck A, McKone EF, van der Ent CK, Moeller A, Simard C, Wang LT, Ingenito EP, McKee C, Lu Y et al. : Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for Phe508del. The New England journal of medicine 2017, 377(21):2013–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Davies JC, Moskowitz SM, Brown C, Horsley A, Mall MA, McKone EF, Plant BJ, Prais D, Ramsey BW, Taylor-Cousar JL et al. : VX-659-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 379(17):1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Keating D, Marigowda G, Burr L, Daines C, Mall MA, McKone EF, Ramsey BW, Rowe SM, Sass LA, Tullis E et al. : VX-445-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 379(17):1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sawicki GS, McKone EF, Pasta DJ, Millar SJ, Wagener JS, Johnson CA, Konstan MW: Sustained Benefit from ivacaftor demonstrated by combining clinical trial and cystic fibrosis patient registry data. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2015, 192(7):836–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.