Abstract

Gastric cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide, and most of the cases are associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. This bacterium promotes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause DNA damage in gastric epithelial cells. In this study, we evaluated the expression of important genes involved in the recognition of DNA damage (ATM, ATR, and H2AX) and ROS-induced damage repair (APE1) and the expression of some miRNAs (miR-15a, miR-21, miR-24, miR-421 and miR-605) that target genes involved in the DNA damage response (DDR) in 31 fresh tissues of gastric cancer. Cytoscape v3.1.1 was used to construct the postulated miRNA:mRNA interaction network. Analysis performed by real-time quantitative PCR exhibited significantly increased levels of the APE1 (RQ = 2.55, p < 0.0001) and H2AX (RQ = 2.88, p = 0.0002) genes beyond the miR-421 and miR-605 in the gastric cancer samples. In addition, significantly elevated levels of miR-21, miR-24 and miR-421 were observed in diffuse-type gastric cancer. Correlation analysis reinforced some of the gene:gene (ATM/ATR/H2AX) and miRNA:mRNA relationships obtained also with the interaction network. Thus, our findings show that tumor cells from gastric cancer presents deregulation of genes and miRNAs that participate in the recognition and repair of DNA damage, which could confer an advantage to cell survival and proliferation in the tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: DNA damage response, DNA repair, Gastric cancer, Gene expression, microRNA

Introduction

Gastric cancer, one of the most common types of cancer, is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide1 and presents wide variations in incidence throughout the world.2 In Brazil, gastric cancer ranks fourth in incidence and second in death, with an estimated 23,290 new cases in 2018.3 Diets high in food preservatives (salts and nitrates), alcohol, and smoking are among the main risk factors for gastric carcinogenesis.4 However, chronic inflammation induced by infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the most important factor.5 This bacterium, which colonizes the gastric mucosa, and its virulence factors, such as cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) and vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), are responsible for increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) produced by immune and epithelial cells in an attempt to kill the bacteria.6 The excessive production of ROS is believed to be a major cause of gastric mucosal DNA damage in the infected mucosa,7 thus promoting genomic instability and tumorigenesis.8

Furthermore, ROS produced during H. pylori infection can cause DNA oxidation, leading to the generation of abasic sites,6 which are recognized and processed by human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1), an essential enzyme that is involved in the base excision repair (BER) pathway.9 Previous studies have shown increased APE1 expression in various types of cancer,10, 11, 12 including gastric cancer,13 thus suggesting that APE1 could be associated with survival outcome, lymph node status, proliferation index and resistance to chemotherapy or radiotherapy14 and that upregulation of BER in solid cancers may represent an adaptive survival response.15

In addition, H. pylori can also induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs),16 activating the DDR (DNA damage response), a complex network that includes specialized sensor proteins to recognize DNA damage and transducer proteins to recruit subsequent effector proteins, which in turn are responsible for cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, transcription arrest, and DNA repair.17 In response to DSBs, the activation of proteins such as ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and Rad3-related (ATR) occurs to recognize DNA damage, resulting in H2AX histone phosphorylation at Ser 139 (γH2AX) as an initial step toward DNA repair.18 If the lesion cannot be repaired, apoptosis or premature senescence is promoted.19

Several studies have shown that the microRNA (miRNA) expression profiles are altered when cells are treated with different types of genotoxic agents and chemical mutagens.20, 21, 22 DNA repair genes are directly inhibited by miRNAs,23 such as miRNA-421 that suppresses ATM expression24 and miRNA-24 that target H2AX.25 Therefore, the interactions of miRNAs and their ability to target DDR components control the cellular response to DNA-damaging agents,26 indicating a pivotal role in DDR regulation.27, 28

Therefore, considering the importance of the DDR in the recognition and repair of DNA damage to guarantee genomic stability, the present study evaluated the expression of important genes involved in recognition (ATM, ATR, and H2AX) and ROS-induced damage repair (APE1) and the miRNAs (miR-15a, miR-21, miR-24, miR-421, and miR-605), selected from public databases (TargetScan, TarBase, and MirTarBase), that target genes of the DDR pathway in gastric cancer tissue samples. The goal of this study was to identify genes and miRNAs that may be modulated in response to induced damage in the gastric mucosa and to construct the interaction network among them.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement and study population

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of IBILCE/UNESP (n° 2.197.528) for the use of DNA/RNA samples stored in our laboratory from a previous study.29 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RNA/DNA were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) from fresh biopsies or surgical fragments collected from 35 individuals recruited at the Service of Endoscopy or the Surgery Center at the Hospital de Base, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. Thirty-one tissue samples were histopathologically diagnosed as gastric adenocarcinoma (GA) according to Lauren's classification,30 and four tissue samples were diagnosed as histologically normal, H. pylori-negative (Hp-), gastric mucosa (NM). These normal tissues were collected from healthy individuals who had no previous history of gastric dyspepsia and were cancer free and were analyzed in qPCR experiments as a pool (prepared from equal amounts of each normal mucosa RNA). Epidemiological data for both GA and NM samples are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiological data from individuals with normal mucosa (NM) and gastric adenocarcinoma (GA).

| Variable | NM N (%) |

GA N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 3 (75) | 6 (19.4) |

| Male | 1 (25) | 25 (80.6) |

| Total | 4 | 31 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 30 ± 12.5 | 65 ± 13.8 |

| <30 3 (75) | <65 16 (51,6) | |

| ≥30 1 (25) | ≥65 15 (48,4) | |

| Total | 4 | 31 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 18 (64,3) |

| No | 4 (100) | 10 (35,7) |

| Total | 4 | 28a |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 14 (50) |

| No | 4 (100) | 14 (50) |

| Total | 4 | 28 |

| H. pylori | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 15 (50) |

| Negative | 4 (100) | 15 (50) |

| Total | 4 | 30a |

| Histological type | ||

| Intestinal | – | 26 (86,7) |

| Diffuse | – | 4 (13,3) |

| Total | 30a | |

Data not available for some individuals; N = number of individuals.

Molecular diagnosis of H. pylori infection

The molecular diagnosis was performed according to the protocol of Singh et al.,31 based on nested PCR to amplify the HSP60 gene. The PCR was carried out in a 25-μL volume using 1 × PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM (each) deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 10 μM each primer (HSP1: 5′-AAGGCATGCAATTTGATAGAGGCT-3′ HSP2: 5′-TTTTTTCTCTTTCATTTCCACTT-3′), 1 U of Platinum Taq polymerase (Carlsbad, California, USA), and 100 ng of DNA. For internal amplification, the PCR product from the primary cycle was diluted 1:10, and 10 μL was used as the template in the nested PCR using the primers HSPN1 (5′-TTGATAGAGGCTACCTCTCC-3′) and HSPN2 (5′-TGTCATAATCGCTTCTCGTGC-3′). All the amplification reactions were carried out in a thermal cycler (LabNet Inc) over 30 cycles, changing the temperature from 94 °C to 56 °C to 72 °C, holding each temperature for 30 s. In all the reactions, a negative control without DNA and a negative control containing intestinal DNA sample with a negative diagnosis for H. pylori were used. The nested PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and staining with ethidium bromide. A 501-bp fragment was observed in only the H. pylori-positive samples.

Relative quantification of mRNA and miRNA expression levels by quantitative PCR (qPCR)

First, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized for mRNA and miRNA with the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer's protocols. qPCR was performed in a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (version 2.2.3) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with TaqMan assays using specific probes for the target genes APE1 (Hs00959050_g1), ATM (Hs00175892_m1), ATR (Hs00992123_m1), and H2AX (Hs00266783_s1) and for the miRNAs hsa-miR-15a-5p (MIMAT0000068), hsa-miR-21-5p (MIMAT0000076), hsa-miR-24-3p (MIMAT0000080), hsa-miR-421 (MIMAT0003339), and hsa-miR-605-5p (MIMAT0003273). The reference genes ACTB (Hs99999903_m1) and GAPDH (Hs03929097_g1) were used as endogenous control genes and RNU6B (001093) and RNU48 (001006) were used as control miRNAs in all the analyses, according to the validation performed in a previous study.32 All reactions were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 10 μL using GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix 2 × (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Raw cycle quantification (Cq) data were generated by StepOnePlus™ Software (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California, USA) and normalized to the reference control genes. Relative quantification (RQ) of mRNA and miRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method according to the model proposed by Livak and Schmittgen,33using the pool of Hp- normal mucosa samples as calibrator (RQ = 1.0). qPCR experiments followed the MIQE guidelines,34 and RQ values were expressed as medians of the genes and miRNAs for the GA group.

In silico analysis for prediction of miRNA targets and the miRNA:mRNA interaction network

Considering only the genes and miRNAs evaluated in the present study, an in silico analysis for the search of genes considered as predicted targets was performed from the RNA22-HAS (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22), TARGETSCAN-VERT (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71), MICRORNA.ORG (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do), and MIRDB (MirTar2 v4.0) (http://mirdb.org/miRDB/index.html) databases, while those genes considered as validated targets were collected from the MIRTARBASE (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/) and TARBASE (http://diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/DianaTools/index.php?r=tarbase/index) databases (Supplementary Table 1). For predicted targets, only genes identified by at least three databases were considered. Then, data were integrated using bioinformatic methods, and genes were mapped into proteins, which were then used to construct protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. The PPI networks were generated using the Metasearch STRING platform v10.5.35 Data integration and visualization were performed using Cytoscape v3.1.1.36

Statistical analysis

Initially, the data were evaluated using the D'Agostino-Pearson normality test. All data analyzed were considered non-parametric and the values for the relative expression (RQ) of mRNA and miRNA were expressed as medians with interquartile range. The One-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess changes in mRNA or miRNA expression levels compared to those in a pool of normal mucosa samples (RQ = 1.0), while the correlation between mRNA and miRNA expression was analyzed using Spearman's correlation. The analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism software (version 6.01). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Deregulated expression of genes and miRNAs involved in the DDR in gastric cancer tissues

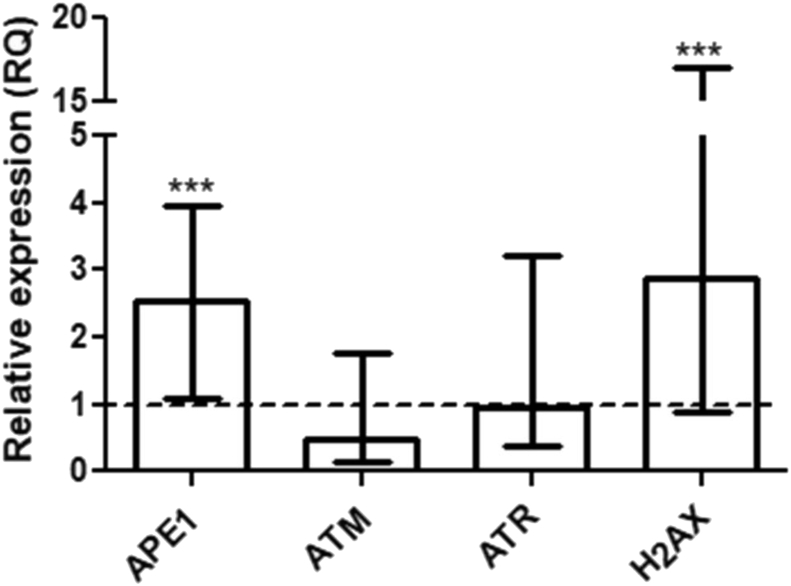

qPCR analysis showed significantly upregulated expression of the APE1 (RQ = 2.55, p < 0.0001) and H2AX (RQ = 2.88, p = 0.0002) genes in the gastric cancer samples compared to the expression in the normal mucosa. However, the expression level of the ATM (RQ = 0.46, p = 0.45) and ATR (RQ = 0.94, p = 0.41) genes were not significantly altered in the gastric cancer samples (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Relative expression of the mRNA of the APE1, ATM, ATR, and H2AX genes in the gastric cancer samples in comparison to the expression of a pool of normal mucosa and the expression of the reference genes (ACTB and GAPDH). The dashed line represents the RQ value of a pool of normal gastric mucosa samples used as calibrator (RQ = 1.0) and error bars represent the interquartile range.

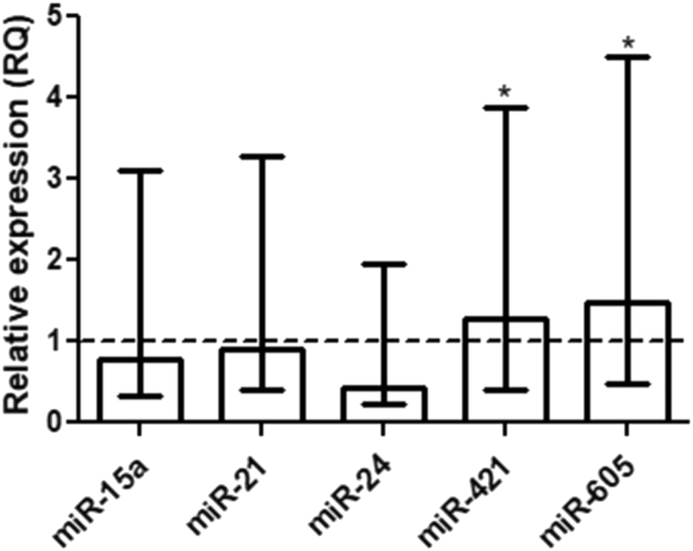

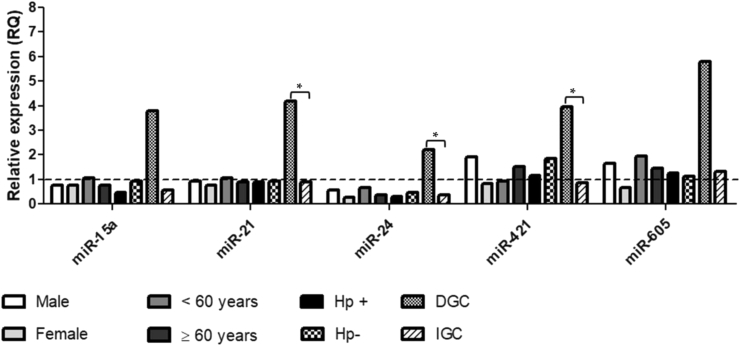

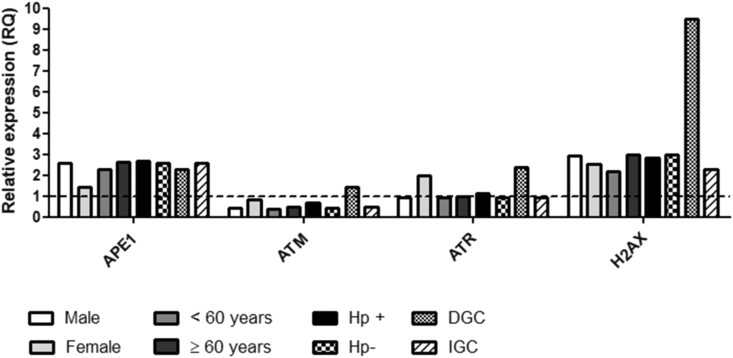

Among the miRNAs evaluated for involvement in the regulation of the DDR, significant upregulation for miR-421 (RQ = 1.27, p = 0.04) and miR-605 (RQ = 1.47, p = 0.02) was observed, while no significant change in the expression of miR-15a (RQ = 0.78, p = 0.50), miR-21 (RQ = 0.89, p = 0.91), and miR-24 (RQ = 0.43, p = 0.82), was detected in the gastric cancer group compared to the expression of a pool of normal mucosa (Fig. 2). In contrast, when we stratified the samples by the histological type of cancer, we identified significantly higher expression of miR-21, miR-24, and miR-421 in diffuse-type cancer than in intestinal-type cancer (Fig. 3). Regarding the mRNA expression levels of the evaluated genes (APE1, ATM, ATR, and H2AX), no significant association was observed with risk factors such as gender, age, H. pylori infection, and histological type of gastric cancer (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Relative expression of the miRNAs (miR-15a, miR-21, miR-24, miR-421, and miR-605) in the gastric cancer samples in comparison to the expression of a pool of normal mucosa and the expression of endogenous RNUs (RNU6B and RNU48). The dashed line represents the RQ value of a pool of normal gastric mucosa samples used as calibrator (RQ = 1.0) and error bars represent the interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the relative expression levels of the microRNAs (miR-15a, miR-21, miR-24, miR-421, and miR-605) according to the risk factors gender, age, H. pylori status, and histological tumor type, in the gastric cancer group. The dashed line represents the RQ value of a pool of normal gastric mucosa samples used as calibrator (RQ = 1.0). Hp+ (H. pylori positive); Hp- (H. pylori negative); DGC (diffuse-type gastric cancer); IGC (intestinal-type gastric cancer).

Figure 4.

Comparison of mRNA expression levels of the APE1, ATM, ATR, and H2AX genes according to the risk factors gender, age, H. pylori status, and histological tumor type, in the gastric cancer group. The dashed line represents the RQ value of a pool of normal gastric mucosa samples used as calibrator (RQ = 1.0). Hp+ (H. pylori positive); Hp- (H. pylori negative); DGC (diffuse-type gastric cancer); IGC (intestinal-type gastric cancer).

Correlation analysis and interaction network involved in the DDR

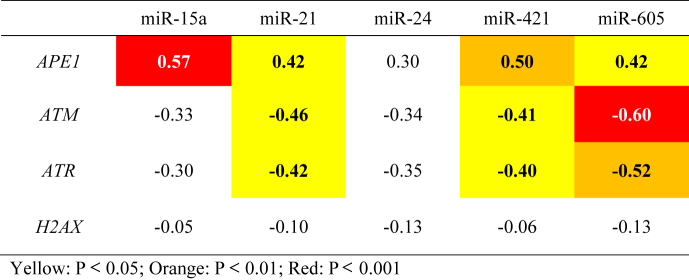

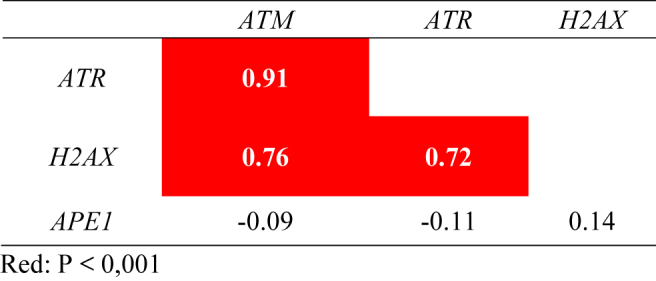

The expression of the ATM, ATR, and H2AX genes was positively correlated in gastric cancer samples (Table 2). The strongest correlation was observed between ATM and ATR (r = 0.91, p < 0.0001), followed by the correlations between ATM and H2AX (r = 0.76, p = 0.0002) and between ATR and H2AX (r = 0.72, p < 0.0001). However, the expression of the APE1 gene did not correlate with that of any of these genes. In addition, significant negative correlations were observed among the expression of miR-21, miR-421, and miR-605 and the ATM and ATR genes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis among the relative expression levels of DDR genes in gastric cancer samples. Data are presented as the Spearman correlation coefficient (r), with significant correlations highlighted in color.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis among the relative expression levels of genes and miRNAs associated with the DDR in gastric cancer samples. Data are presented as the Spearman correlation coefficient (r), with significant correlations highlighted in color.

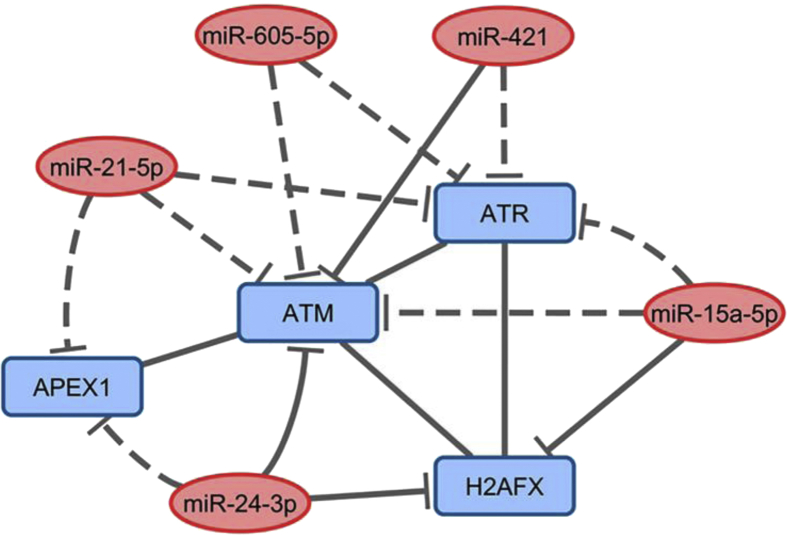

The interaction network depicted in Fig. 5 shows strong relationships among genes and miRNAs participating in the DDR and reinforces the negative correlations observed between the expression of the miR-21, miR-421, and miR-605 and the ATM and ATR genes (Table 3). Furthermore, we also observed interactions among the ATM, ATR, and H2AX genes (Fig. 5), confirming the strong positive correlations observed among the expression levels of these genes in gastric cancer samples (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Interaction networks among the proteins encoded by target genes that are regulated by the miRNAs. Rectangles represent the genes, and the ellipses represent the miRNAs. Dashed lines represent predicted interactions, and the continuous line represents validated interactions. APEX1 = APE1; H2AFX = H2AX.

Discussion

Our results show that gastric cancer tissues exhibit elevated expression of the genes (APE1 and H2AX) and miRNAs (miR-421 and miR-605) involved in DDR and DNA repair, independent of H. pylori infection, histological type, gender or age. However, upon considering the histological type, miR-21, miR-24, and miR-421 presented upregulation in diffuse-type gastric cancer tissues. Our findings also showed significant positive correlations in mRNA expression among ATM/ATR/H2AX, as well as negative correlations among miR-605/ATM/ATR, miR-21/ATM/ATR, and miR-421/ATM/ATR demonstrating gene:gene and gene:miRNA interrelations, which were supported by the miRNA:mRNA interaction network (Fig. 5).

It has been suggested that BER factors may be preferentially upregulated in tumors to repair DNA damage induced by oxidative stress.37 Accordingly, several studies have reported increased expression of APE1 in gastric cancer, being correlated with poor prognosis and development,13 poor overall survival,38 and lymph node metastasis,39 acting as a marker for prognosis in patients with gastric cancer.11, 13 In our study, we also observed elevated expression of APE1 in fresh samples of patients with gastric cancer, reinforcing the hypothesis that upregulation of BER in solid tumors may represent an adaptive survival response in the tumor microenvironment.15

Moreover, oxidative stress in tumors can promote DNA damage that generate oxidative base damage, AP sites, DNA single strand (SSBs) and double strand-breaks (DSBs).37 In our study, we observed upregulation of the mRNA of H2AX in gastric cancer samples, possibly indicating the occurrence of DSBs in the DNA of tumor cells. Furthermore, other studies observed high expression of γH2AX in several types of cancer,40, 41, 42 including gastric cancer and gastric precancerous lesions.43 Considering that H2AX acts as a key factor in the repair process of damaged DNA and in the maintenance of DNA stability, H2AX/γH2AX has been proposed as marker for early cancer detection, prognosis, and therapeutics.40

H2AX phosphorylation is catalyzed by ATM, ATR and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), which are kinases that belong to the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) family.44 While ATM is a key player in the activation of cell cycle checkpoints in response to radiation-induced DSBs,45 ATR is activated during every S-phase in response to a wide range of DNA damage, such as single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and DNA replication errors.46

Although in our study we observed low expression of ATM level (RQ = 0.46) in gastric cancer samples, no significant difference was observed. However it has already been described decreased expression of ATM in gastric cancer cell line exposed to ionizing radiation,47 and in gastric cancer tissues correlated with poor prognosis.48 In addition, we also found no alterations in the mRNA expression of ATR gene (RQ = 0.94) in samples of gastric cancer, but mutations in the ATR gene have been observed in colon cancers.49 There is only one study in gastric cancer that observed loss of ATR protein expression by immunohistochemical analysis.50 Therefore, our study adds information about mRNA expression level of this gene in gastric cancer, indicating the need for further studies on this important gene involved in DNA damage-associated signaling. Furthermore, we observed a strong positive correlation among ATM/ATR/H2AX gene expression levels, further highlighting the role of interactions among these genes in the recognition of DNA damage.

Notably, the complex DNA repair machinery can be regulated by miRNAs.51 It has been suggested that there is a bidirectional connection between miRNAs and the DDR; while some DDR proteins appear to regulate miRNA expression, miRNAs also influence DDR protein expression.23 A large number of miRNAs are transcriptionally induced by different doses of DNA-damaging agents, and the level of induction is variable depending on cell type and the nature and intensity of DNA damage.23

In gastric cancer, upregulation or downregulation of specific miRNAs has been observed,52 which may be associated with progression and prognosis of this cancer.53 We evaluated the expression levels of five miRNAs (miR15a, miR-21, miR-24, miR-421, and miR-605) that target some key proteins involved with the DDR (BCL2, CDC25A, H2AX, ATM, and MDM2)51, 54 in gastric cancer samples, and we found significantly increased expression of miR-421 and miR-605 in these samples, besides upregulation of miR-21, miR-24, and miR-421 in diffuse-type gastric cancer samples compared to the expression in intestinal-type gastric cancer samples, while no change in the expression of the other miRNAs was observed.

Increased expression of miR-421 has been observed in gastric cancer tissues compared to the expression in adjacent tissues and normal tissues.55, 56 Therefore, acting as an oncogene to facilitate tumor growth in gastric cancer,56 mainly in the early stage of stomach carcinogenesis, and being indicated as an efficient diagnostic biomarker.57 Recently, increased expression of miR-421 was also associated with lymph node metastasis and the clinical stage of gastric cancer.58 Thus, our study further indicates the occurrence of high expression of this miRNA, mainly in diffuse gastric cancer. In addition, miR-421 showed negative correlations with the expression levels of the ATM and ATR, their validated and predicted targets, respectively (Fig. 5).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the expression of miR-605 in gastric cancer. Our study is the first to show significant increase of the miR-605 (RQ = 1.47) in the gastric cancer samples. Furthermore, our study identified negative correlations between miR-605 and the mRNA level of the ATM and ATR, which are considered predicted targets of this miRNA (Fig. 5). These results are interesting and should be confirmed in future studies. Moreover, a previous study from our laboratory showed that the miR-605 rs2043556 (A > G) polymorphism confers an increased risk for the development of gastric cancer in individuals from the southeastern region of Brazil,59 thus indicating a possible involvement of this miRNA in gastric carcinogenesis.

Cumulative evidence indicates that miR-21 plays a significant role in the progression of gastric cancer, suggesting that this miRNA can be used as a candidate for early detection and prognosis prediction56, 60 and for prognosis of lymph node metastasis.61 Recently, Gu et al.62 reported high levels of miR-21 in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells, supporting the potential of this miRNA as a marker for early diagnosis and target treatment. In the present study, increased expression of miR-21 and miR-24 was observed only in diffuse-type gastric cancer. It has been shown that miR-24 can be potentially used for early diagnosis and as a tumor molecular marker to assess the stage of gastric lesions and lymph node and liver metastasis.63 This miRNA can regulate gastric carcinogenesis by modulating proliferation, migration, and local invasion and has been suggested as a therapeutic target for gastric cancer.64 Moreover, miR-24 regulates the histone variant H2AX, which plays a key role in DNA damage signaling via phosphorylation of its C terminus. Lal et al.25 showed that upregulation of miR-24 in postreplicative cells reduces H2AX and thereby renders the cells highly vulnerable to DNA damage induced by genotoxic agents.

It has been suggested that circulating miRNAs exhibit unique profiles for each tumor and histopathological subtype.65 Using a mouse model of diffuse-type gastric cancer (DGC) similar to that in humans, Rotkrua et al.66 identified circulating miRNAs upregulated in the sera of mice with both early- and advanced-stage DGC compared with controls, suggesting that these miRNAs can serve as noninvasive biomarkers for DGC diagnosis. Accordingly, our results also suggest that miR-21, miR-24, and miR-421 can be potential biomarkers for DGC diagnosis, which needs to be investigated in future studies.

miR-15a has previously been identified as a tumor suppressor that promotes apoptosis and inhibits cell proliferation, and reduced expression of miR-15a is predictive of a poor survival outcome.67 The expression of this miRNA has been found to be significantly reduced in gastric cancer,68 with ectopic expression of miR-15a being linked to reduced gastric cancer cell growth and invasion.69 However, our study found no significant change in the expression level of miR-15a (RQ = 0.78) in gastric cancer samples.

Although half of the gastric cancer samples evaluated in the present study were H. pylori positive, we did not observe an association of H. pylori infection with the expression levels of the genes and miRNAs investigated. It is possible that the small number of samples obtained after stratification according to the presence and absence of the bacteria may have influenced the statistical analysis. In addition, it is known that H. pylori shows a stronger relationship with the early stage of gastric cancer than with the advanced stage,70 H. pylori infection is often acquired in childhood and persists for years, but the infection tends to disappear with advanced atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, rendering the gastric mucosa inhospitable to the bacterium but increasing the cancer risk even after loss of infection.71 Moreover, the incubation period of H. pylori infection is longer in advanced cancer patients than in early cancer patients, and this factor may lead to frequent positive-to-negative changes in serology in advanced cancer patients, which is consistent with the weak correlation between advanced gastric cancer and H. pylori infection.72 Therefore, all of these factors may influence the analysis of the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings show the elevated expression of genes and miRNAs that act in response to DNA damage and repair, such as APE1, H2AX, miR-421 and miR-605 in gastric cancer tissues, which might be involved with the survival of the cells in the tumor microenvironment. However, additional studies are needed to better understand the performance of these genes and miRNAs in response to the treatment of gastric tumor cells with DNA-damaging agents in an attempt to identify possible therapeutic targets for the treatment of this type of neoplasia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant number 2015/21464-0), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, grant number 1460154) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, grant number 310120/2015-2).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2019.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Globocan . International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. New Global Cancer Data: GLOBOCAN 2018.https://www.uicc.org/new-global-cancer-data-globocan-2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart B.W., Wild C.P. World Health Organization Press; Lyon, France: 2014. World Cancer Report 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Instituto Nacional do Câncer (INCA) Tipos de câncer: estômago. https://www.inca.gov.br/tipos-de-cancer/cancer-de-estomago

- 4.Karimi P., Islami F., Anandasabapathy S. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23:700–713. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quadri H.S., Smaglo B.G., Morales S.J. Gastric adenocarcinoma: a multimodal approach. Front Surg. 2017;4:42. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2017.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butcher L.D., den Hartog G., Ernst P.B., Crowe S.E. Oxidative stress resulting from Helicobacter pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handa O., Naito Y., Yoshikawa T. Helicobacter pylori: a ROS-inducing bacterial species in the stomach. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:997–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eftang L.L., Esbensen Y., Tannæs T.M. Interleukin-8 is the single most up-regulated gene in whole genome profiling of H. pylori exposed gastric epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley M.R., Georgiadis M.M., Fishel M.L. APE1 ⁄ Ref-1 role in redox signaling: translational applications of targeting the redox function of the DNA repair ⁄ redox protein APE1 ⁄ Ref-1. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2012;5:36–53. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo D.G., Song Y.J., Cho E.J. Alteration of APE1/ref-1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: the implications of impaired extracellular superoxide dismutase and catalase antioxidant systems. Lung Canc. 2008;60:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Attar A., Gossage L., Fareed K.R. Human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1) is a prognostic factor in ovarian, gastro-oesophageal and pancreatico-biliary cancers. Br J Canc. 2010;102:704–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou D., Zhu L., Ding H. Aberrant expression of redox protein Ape1 in colon cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1078–1082. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qing Y., Li Q., Ren T. Upregulation of PD-L1 and APE1 is associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:901–909. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo J., Park H., Sung S.H. Prognostic value of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) expression in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo Y., Kinsella T.J. Essential role of DNA base excision repair on survival in an acidic tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7285–7293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toller I.M., Neelsen K.J., Steger M. Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14944–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper J.W., Elledge S.J. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao A., Li H., Shechter D. WSTF regulates the H2A.X DNA damage response via a novel tyrosine kinase activity. Nature. 2009;457:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature07668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalisperati P., Spanou E., Pateras I.S. Inflammation, DNA damage, Helicobacter pylori and gastric tumorigenesis. Front Genet. 2017;8:20. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wouters M.D., van Gent D.C., Hoeijmakers J.H., Pothof J. MicroRNAs, the DNA damage response and cancer. Mutat Res. 2011;717:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G., Sun L., Lu X. Cisplatin treatment leads to changes in nuclear protein and microRNA expression. Mutat Res. 2012;746:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang G., Li G., Wang Y. Aberrant miRNA expression response to UV irradiation in human liver cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:904–910. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma V., Misteli T. Non-coding RNAs in DNA damage and repair. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1832–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu H., Du L., Nagabayashi G. ATM is down-regulated by N-Myc-regulated microRNA-421. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1506–1511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907763107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lal A., Pan Y., Navarro F. MiR-24-mediated downregulation of H2AX suppresses DNA repair in terminally differentiated blood cell. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:492–498. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y., Taniguchi T. MicroRNAs and DNA damage response: implications for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:32–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.23051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magistri M., Faghihi M.A., St Laurent G., 3rd, Wahlestedt C. Regulation of chromatin structure by long noncoding RNAs: focus on natural antisense transcripts. Trends Genet. 2012;28:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rinn J.L., Chang H.Y. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira J.G., Rossi A.F., Nizato D.M. Influence of functional polymorphisms in TNFA, IL8 and IL10 cytokine genes on mRNA expression levels and risk of gastric cancer. Tumor Biol. 2015;32:9159–9170. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh V., Mishra S., Rao G.R. Evaluation of nested PCR in detection of Helicobacter pylori targeting a highly conserved gene: HSP60. Helicobacter. 2008;13:30–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi A.F.T., Cadamuro A.C., Biselli-Périco J.M. Interaction between inflammatory mediators and miRNAs in Helicobacter pylori infection. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1444–1458. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2- ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bustin S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szklarczyk D., Morris J.H., Cook H. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction network. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbotts R., Madhusudan S. Human AP endonuclease 1 (APE1): from mechanistic insights to druggable target in cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei X., Duan W., Li Y. AT101 exerts a synergetic efficacy in gastric cancer patients with 5-FU based treatment through promoting apoptosis and autophagy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:34430–34441. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei X., Li Y.B., Li Y. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer by serum APE1 expression. J Cancer. 2017;8:1492–1497. doi: 10.7150/jca.18615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sedelnikova O.A., Bonner W.M. GammaH2AX in cancer cells: a potential biomarker for cancer diagnostics, prediction and recurrence. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2909–2913. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu T., MacPhail S.H., Banath J.P. Endogenous expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX in tumors in relation to DNA double-strand breaks and genomic instability. DNA Repair. 2006;5:935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagelkerke A., van Kuijk S.J., Sweep F.C. Constitutive expression of gamma-H2AX has prognostic relevance in triple negative breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Z., Pei S., Si T. Expression of the γ-phosphorylated histone H2AX in gastric carcinoma and gastric precancerous lesions. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1790–1794. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stiff T., Walker S.A., Cerosaletti K. ATR-dependent phosphorylation and activation of ATM in response to UV treatment or replication fork stallin. EMBO J. 2006;25:5775–5782. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavin M.F., Kozlov S. ATM activation and DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:931–942. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marechal A., Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinase. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012716. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L., Jia G., Li W.M. Alteration of the ATM gene occurs in gastric cancer cell lines and primary tumors associated with cellular response to DNA damage. Mutat Res. 2004;557:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang B., Guo R.F., Tan X.H. Expression status of ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated gene correlated with prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Mutat Res. 2008;638:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis K.A., Bakkum-Gamez J., Loewen R. Mutations in the ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related-checkpoint kinase 1 DNA damage response axis in colon cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Z.Z., Liu Y.J., Yin X.L. Loss of BRCA1 expression leads to worse survival in patients with gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1968–1974. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Majidinia M., Yousefi B. DNA damage response regulation by microRNAs as a therapeutic target in cancer. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;47:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Q.X., Zhu Y.Q., Zhang H., Xiao J. Altered MiRNA expression in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:933–944. doi: 10.1159/000369750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valenzuela M.A., Canales J., Corvalán A.H., Quest A.F. Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and epigenetic changes during gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12742–12756. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao J., Lin H., Luo X. miR-605 joins p53 network to form a p53:miR-605:Mdm2 positive feedback loop in response to stress. EMBO J. 2011;30:5021. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu H., Gao Y., Song D., Liu T., Feng Y. Correlation between microRNA-421 expression level and prognosis of gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:15128–15132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J., Li G., Yao Y. MicroRNA-421 is a new potential diagnosis biomarker with higher sensitivity and specificity than arcinoembryonic antigen and cancer antigen 125 in gastric cancer. Biomarkers. 2015;20:58–63. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.992812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang Z., Guo J., Xiao B. Increased expression of miR-421 in human gastric carcinoma and its clinical association. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang P., Zhang M., Liu X., Pu H. MicroRNA-421 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by targeting claudin-11. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:2625–2632. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poltronieri-Oliveira A.B., Madeira F.F., Nunes D.B.S.M. Polymorphisms of miR-196a2 (rs11614913) and miR-605 (rs2043556) confer susceptibility to gastric cancer. Gene Rep. 2017;7:154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 60.LArki P., Ahadi A., Zare A. Up-Regulation of miR-21, miR-25, miR-93, and miR-106b in Gastric Cancer. Iran Biomed J. 2018;22:367–373. doi: 10.29252/.22.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren J., Kuang T.H., Chen J. The diagnostic and prognostic values of microRNA-21 in patients with gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:120–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu J.B., Bao X.B., Ma Z. Effects of miR-21 on proliferation and apoptosis in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:618–622. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Q., Wang N., Wei H. miR-24-3p regulates progression of gastric mucosal lesions and suppresses proliferation and invasiveness of N87 via peroxiredoxin 6. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3486–3497. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4309-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duan Y., Hu L., Liu B. Tumor suppressor miR-24 restrains gastric cancer progression by downregulating Reg IV. Mol Canc. 2014;13:127. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song J.H., Meltzer S.J. MicroRNAs in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroesophageal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:35–47. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rotkrua P., Shimada S., Mogushi K. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for early detection of diffuse-type gastric cancer using a mouse model. Br J Canc. 2013;108:932–940. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao G., Tang H., Wei W. Aberrant expression of microRNA-15a and microRNA-16 Synergistically associates with tumor progression and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:364549. doi: 10.1155/2014/364549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang T., Hou J., Li Z. miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p negatively regulate Twist1 to repress gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:122–134. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu C., Zheng X., Li X. Reduction of gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by miR-15a mediated suppression of Bmi-1 translation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:14522–14536. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kikuchi S., Nakajima T., Kobayashi O. Effect of age on the relationship between gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori. Jpn J Canc Res. 2000;91:774–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Correa P., Piazuelo M.B. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma. US Gastroenterol Hepatol Rev. 2011;7:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kikuchi S. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:6–15. doi: 10.1007/s101200200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.