Abstract

Background

Numerous studies suggested that occupational or environmental exposure to lead adversely affects renal function. However, most studies lost relevance because of the substantially lower current environmental lead exposure and all relied on serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration. We investigated the association of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), estimated from serum creatinine, cystatin C or both, with blood lead (BPb) using the baseline measurements of the ongoing Study for Promotion of Health in Recycling Lead (SPHERL; NCT02243904) in newly hired workers prior to significant occupational lead exposure.

Methods

Among 447 men (participation rate, 82.7%), we assessed the association of eGFR and the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) with BPb across thirds of the BPb distribution using linear regression analysis. Fully adjusted models accounted for age, blood pressure, body mass index, the waist-to-hip ratio, smoking, the total-to-high-density-lipoprotein ratio, plasma glucose, serum γ-glutamyltransferase and antihypertensive drug treatment.

Results

Age averaged 28.7 (SD, 10.2) years (range, 19.1–31.8). Geometric mean BPb concentration was 4.34 μg/dL (5th–95th percentile interval, 0.9–14.8). In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, eGFR estimated from serum creatinine [mean (SD), 105.26 (15.2) mL/min/1.73 m2], serum cystatin C [mean (SD), 127.8 (13.8) mL/min/1.73 m2] or both [mean (SD), 111.9 (14.8) mL/min/1.73 m2] was not associated with BPb (P ≥ 0.36), whereas ACR [geometric mean, 4.32 mg/g (5th–95th percentile interval, 1.91–12.50)] was lower with higher BPb.

Conclusions

At the BPb levels observed in this study, there was no evidence for an association between renal function and lead exposure.

Keywords: eGFR, environmental exposure, lead, occupational medicine, renal function

INTRODUCTION

Lead intoxication, such as observed in moonshiners [1], causes nephropathy characterized by the deposition of lead in the straight S3 segments of the proximal tubules and proximal renal tubular dysfunction [2]. Various studies in workers and populations have suggested that occupational or environmental exposure to lead is associated with decrements in renal function [3, 4]. Major factors limiting the interpretation of this abundant literature [3, 4] are incomplete adjustment for confounders, limited relevance of many earlier studies, which were conducted at much higher occupational or environmental lead exposure than presently observed, and estimation of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) from serum creatinine rather than from serum cystatin C or both serum markers [5]. In the USA, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) documented a progressive decline in the geometric blood lead (BPb) concentration over time. Among adults, mean BPb levels decreased from 13.1 μg/dL in NHANES II (1976–80) [6, 7] to 1.2–2.76 μg/dL in NHANES III (1988–94) [8] and next to 1.64 μg/dL in NHANES IV (1999–2002) [8]. Concurrent estimates of GFR based on serum creatinine were inversely associated with BPb [3, 4], suggesting that low-level lead exposure could affect function. However, creatinine-based estimated GFR (eGFR) estimates are imprecise, potentially leading to the over-diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Cystatin C is an alternative filtration marker for estimating eGFR that is less vulnerable to confounding by ethnicity, sex, age, muscle mass and protein intake [5]. Against this background, our aim was to investigate the association between renal function and BPb using the baseline measurements of the ongoing Study for Promotion of Health in Recycling Lead (SPHERL; NCT02243904) [9] in newly hired workers prior to significant occupational lead exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SPHERL is a longitudinal study of newly hired lead workers at battery manufacturing and lead recycling plants in the USA [9]. SPHERL complies with the Declaration of Helsinki for investigations in humans [10]. The Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium) approved the study protocol. Of 556 men invited from 1 May 2015 until 19 September 2017, 460 of them gave written informed consent (participation rate, 82.7%). We excluded 13 participants from the present analysis of SPHERL baseline data because of previous known occupational lead exposure. Thus, the number of workers statistically analysed totalled 447.

Blood pressure was the average of five consecutive auscultatory readings obtained with a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after participants had rested for 5 min or longer in the sitting position [11]. Mean arterial pressure was diastolic pressure plus one-third of the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure. Hypertension was a blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg systolic, or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic or use of antihypertensive drugs. Body mass index was body weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Study nurses administered validated questionnaires, inquiring about each worker’s medical history, occupations, exposure to heavy metals, smoking and drinking habits, intake of medications and lifestyle.

Venous samples of whole blood were obtained after 8 h of fasting. Whole BPb levels were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry at an analytical laboratory certified for BPb analysis in compliance with the provisions of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Lead Standard, 29CFR 1910.1025. Prior to analysis, specimens were digested with nitric acid and spiked with an iridium internal standard. The analytical laboratory participated in BPb proficiency testing programmes. The detection limit was 0.5 µg/dL. The deviation from known lead standards ran along with the samples in each test run was <10%. Measurements on blood included the serum levels of creatinine, cystatin C, γ-glutamyltransferase (an index of alcohol intake), total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol lipid and plasma glucose. Serum creatinine was measured using Jaffe’s method with modifications in a single certified laboratory that applied isotope-dilution mass spectrometry for calibration [12]. We derived eGFR from serum creatinine [13], serum cystatin C [5] or both [5] using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equations [5]. Stages of chronic kidney disease were defined according to the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guideline [14]. Diabetes mellitus was a fasting glucose exceeding 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or use of antidiabetic agents [15]. Fresh urine samples were analysed for microalbuminuria standardized to creatinine. Microalbuminuria was an albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) of ≥2.5 mg/mmol [11].

Database management and statistical analysis were done using SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC, USA). The flow and quality control of the data have been described in the published protocol [9]. Departure from normality was evaluated using Shapiro–Wilk’s statistic. Skewness and kurtosis were computed as the third and fourth moments of the mean divided by the cube of the SD. We applied a logarithmic transformation to normalize the distributions of BPb, serum γ-glutamyltransferase and ACR. The central tendency (spread) of continuous variables was represented by the arithmetic (SD) or geometric (interquartile range) mean. In exploratory analyses, we assessed renal function across thirds of the BPb distribution or by using unadjusted linear regression. Multivariable analyses were adjusted for co-variables with known physiological relevance and potential confounders [16, 17]. Significance was a two-tailed α-level of ≤0.05.

RESULTS

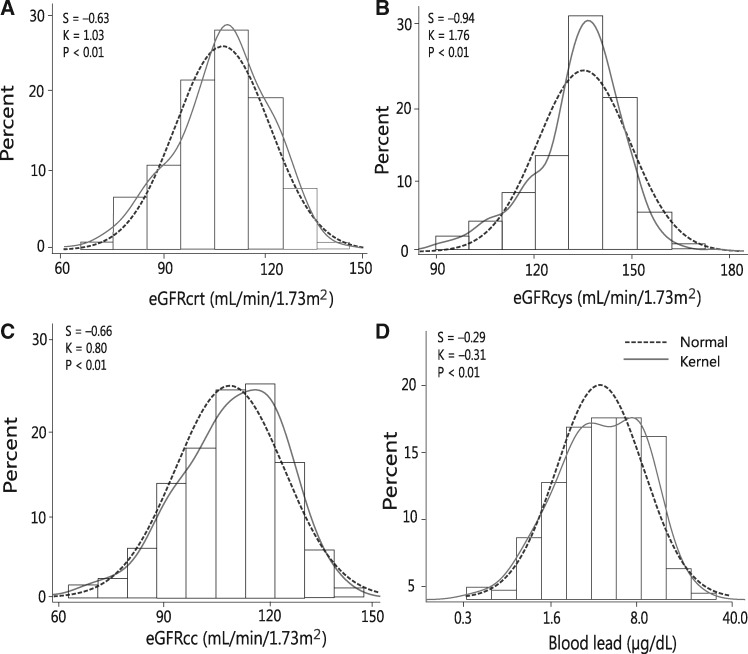

The 447 newly hired workers included 214 Whites (47.87%), 195 Hispanics (43.62%), 16 Blacks (3.58%), 3 Asians (0.67%) and 19 of mixed ethnic descent (4.25%). Prevalence amounted to 133 (29.75%) for smoking, 192 (42.95%) for alcohol consumption, 43 (9.62%) and 43 (9.62%) for hypertension and treated hypertension, respectively, and 9 (2.01%) for diabetes mellitus. Among all workers, average values (SD) were 28.7 (10.2) years for age (range, 19.1–31.8), 120.6 (9.9) mm Hg and 80.6 (8.5) mm Hg for systolic and diastolic blood pressure and 28.7 (6.1) kg/m2 for body mass index. Serum creatinine averaged 0.97 (0.13) mg/dL and serum cystatin C 0.68 (0.10) g/L. The GFR estimated from serum creatinine (eGFRcrt), serum cystatin C (eGFRcys) or both (eGFRcc) averaged 105.2 (15.2), 127.8 (13.8) and 111.9 (14.8) mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. The number of workers with an eGFR <90 and <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 amounted to 72 (16.1%) and 4 (0.89%) for eGFRcrt, to 0 and 7 (1.57%) for eGFRcys and to 31 (6.94%) and 3 (0.67%) for eGFRcc. The geometric means (interquartile range) were 4.34 mg/g (2.84–6.05) for the urinary ACR and 4.34 μg/dL (2.50–7.90) for BPb (Figure 1). The 5th–95th percentile interval of the BPb distribution ranged from 0.9 to 14.80 μg/dL. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the workers by thirds of the BPb distribution. Across the lead categories, mean arterial pressure increased, whereas total cholesterol and ACR decreased.

FIGURE 1.

Distributions of eGFRcrt (A), eGFRcys (B) or both eGFRcc (C) and of logarithmically transformed BPb (D). S and K are the coefficients of skewness and kurtosis. The dotted and full lines represent the normal and kernel density distributions. The P-values are for departure of the actually observed distribution from normality according to Shapiro–Wilk’s statistic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of workers

| Characteristic | BPb <3.0 μg/dL | BPb 3.1–6.3 μg/dL | BPb ≥6.3 μg/dL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in category | 147 | 152 | 148 | |

| Number (%) with characteristic | ||||

| Smoking | 35 (23.8) | 48 (31.5) | 50 (33.7) | 0.06 |

| Drinking alcohol | 62 (42.1) | 72 (47.3) | 58 (39.1) | 0.60 |

| Hypertension | 12 (8.16) | 21 (13.82) | 10 (6.76) | 0.67 |

| Treated hypertension | 12 (8.16) | 21 (13.82) | 10 (6.76) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (2.04) | 4 (2.63) | 2 (1.35) | 0.67 |

| History of nephrolithiasis | 5 (3.40) | 11 (7.24) | 5 (3.38) | 0.98 |

| Average of characteristic | ||||

| Age (years) | 28.8 ± 9.5 | 30.4 ± 11.4 | 27.3 ± 5.3 | 0.11 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.8 ± 6.6 | 29.1 ± 6.2 | 27.3 ± 5.3 | 0.02 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.96 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| Systolic | 120.8 ± 9.6 | 121.2 ± 10.5 | 119.6 ± 9.5 | 0.35 |

| Diastolic | 80.7 ± 8.9 | 80.5 ± 8.9 | 80.7 ± 7.6 | 0.98 |

| Mean | 94.0 ± 8.4 | 94.1 ± 8.7 | 93.7 ± 7.6 | 0.89 |

| Renal function | ||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 0.99 ± 0.14 | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Serum cystatin C (mg/L) | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 0.55 |

| Microalbuminuria | 0.76 (0.40 to 1.30) | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.25) | 0.67 (0.40 to 1.10) | 0.27 |

| eGFRcrt (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 105.4 ± 14.5 | 102.6 ± 16.0 | 107.7 ± 14.8 | 0.01 |

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 127.5 ± 13.9 | 126.6 ± 14.4 | 129.4 ± 13.0 | 0.18 |

| eGFRcc (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 111.8 ± 14.5 | 109.6 ± 15.5 | 114.4 ± 14.2 | 0.02 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 4.51 (2.8–5.98) | 4.47 (2.94–6.34) | 3.99 (2.60–5.74) | 0.22 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 172.0 ± 35.3 | 175.4 ± 37.8 | 167.1 ± 37.4 | 0.15 |

| Serum HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44.2 ± 9.5 | 46.7 ± 10.2 | 47.8 ± 12.8 | 0.01 |

| Total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 0.06 |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 93.9 ± 13.0 | 95.0 ± 11.3 | 92.8 ± 10.9 | 0.28 |

| Serum γ-glutamyltransferase (U/L) | 24.2 (18.0–35.0) | 24.9 (17.5–31.0) | 20.7 (14.0–27.5) | 0.005 |

| BPb (μg/dL) | 1.66 (1.3–2.5) | 4.63 (3.9–5.7) | 10.48 (7.9–12.25) | 0.001 |

Average values are arithmetic (SD) or geometric means (interquartile range). Hypertension was a blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg systolic, or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic or use of antihypertensive drugs. Mean arterial pressure was diastolic pressure plus one-third of the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure. Diabetes mellitus was a fasting glucose exceeding 126 mg/dL or use of antidiabetic agents. Microalbuminuria was an ACR ≥3.5 mg/mmol in women or ≥2.5 mg/mmol in men. P-values were derived by Fisher’s exact test or analysis of variance.

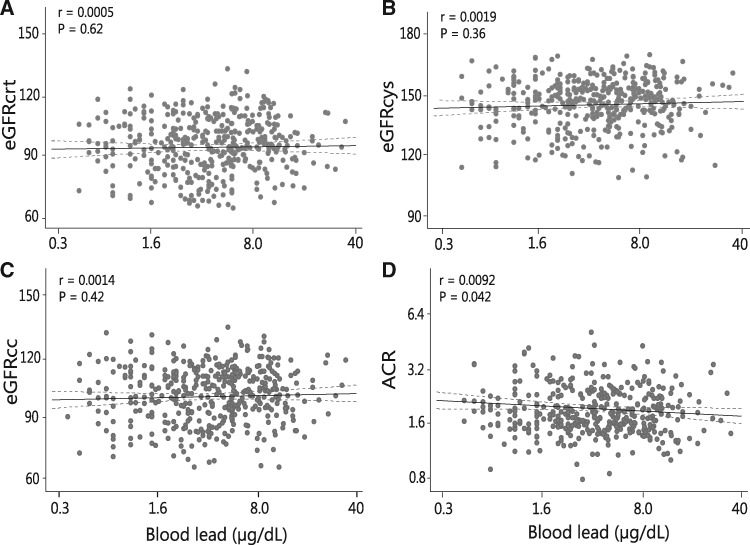

The results of regression analysis appear in Figure 2 and Table 2. Adjusted models included as co-variables: age, mean arterial pressure, body mass index and smoking. Fully adjusted models additionally accounted for the waist-to-hip ratio, the total-to-HDL ratio, plasma glucose, γ-glutamyltransferase and antihypertensive drug treatment. In unadjusted, adjusted and fully adjusted models, associations of eGFRcrt, eGFRcys and eGFRcc with BPb were all non-significant (P ≥ 0.36). Irrespective of the adjustment, ACR was lower with higher BPb. In fully adjusted models, the association size for a doubling of BPb was −0.078 mg/(95% confidence interval, −0.15 to −0.002 mg/g; P = 0.04).

FIGURE 2.

Plots of eGFRcrt (A), eGFRcys (B) or both eGFRcc (C) and of the urinary ACR (D) in relation to BPb. For each association, the unadjusted regression line with the 95% confidence interval is depicted.

Table 2.

Association of renal traits with BPb

| Renal trait | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

Fully adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (CI) | P-value | Estimate (CI) | P-value | Estimate (CI) | P-value | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.0032 (–0.031 to 0.037) | 0.85 | 0.0028 (–0.031 to 0.037) | 0.87 | 0.0011 (–0.033 to 0.035) | 0.94 |

| Serum cystatin C (mg/L) | –0.008 (–0.03 to 0.01) | 0.54 | –0.0007 (–0.026 to 0.024) | 0.95 | 0.0014 (–0.024 to 0.027) | 0.90 |

| eGFRcrt (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.970 (–2.97 to 4.91) | 0.62 | –0.257 (–3.52 to 3.00) | 0.87 | –0.135 (–3.40 to 3.13) | 0.93 |

| eGFRcys (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 1.649 (–1.91 to 5.21) | 0.36 | 0.050 (–2.80 to 2.90) | 0.97 | –0.222 (–3.07 to 2.62) | 0.87 |

| eGFRcc (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 1.554 (–2.28 to 5.38) | 0.42 | –0.195 (–2.98 to 2.59) | 0.89 | –0.281 (–3.07 to 2.50) | 0.84 |

| ACR (mg/mmol) | –0.078 (–0.15 to –0.002) | 0.04 | –0.071 (–0.21 to 0.42) | 0.06 | –0.071 (–0.14 to 0.59) | 0.06 |

Adjusted models included as covariables age, mean arterial pressure, body mass index and smoking. Fully adjusted models additionally accounted for the waist-to-hip ratio, the total-to-HDL ratio, plasma glucose, γ-glutamyl transferase and antihypertensive drug treatment. Association sizes, given with 95% confidence interval (CI), express the difference in the renal trait associated with a doubling of the BPb concentration.

DISCUSSION

In the newly hired workers enrolled in this study, the geometric mean BPb concentration was 4.34 μg/dL and reflected environmental exposure. The key finding was that, in men without previous occupational exposure, the associations of eGFRcrt, eGFRcys and eGFRcc with BPb were non-significant and that ACR was lower with higher BPb.

Whereas severe exposure to lead is nephrotoxic [1, 2], studies of low-level environmental exposure, as in our participants prior to starting work at lead-acid battery manufacturing and recycling plants, are less consistent with respect to the association between renal function and BPb [8, 18–21]. In NHANES III [8], among 4813 hypertensive patients, BPb averaged 4.21 μg/dL, and the prevalence of elevated serum creatinine and chronic kidney disease was 11.5 and 10.0%, respectively. The thresholds applied for serum creatinine varied from 1.2 to 1.6 μg/dL, depending on ethnicity and sex, whereas chronic kidney disease was an eGFRcrt of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. On the other hand, among 10 398 normotensive individuals, the BPb concentration averaged 3.30 μg/dL, while the prevalence of elevated serum creatinine and chronic kidney disease was 1.8 and 1.1%, respectively [8]. In multivariable-adjusted analyses, elevated serum creatinine and the prevalence of chronic kidney disease were associated with BPb among hypertensive patients, but in line with our present findings not among normotensive individuals [8]. Among 459 men enrolled in the Normative Aging Study [18], a 10-fold increase in BPb predicted an increase in the serum creatinine concentration by 80 mg/dL (P = 0.005). The association was also significant among men whose BPb concentration had never exceeded 10 μg/dL. These cross-sectional analyses correlated concurrently measured serum creatinine and BPb in participants with the number of measurements ranging from two to six [18]. Each participant was, therefore, included at least twice in the regression models. There was no correlation between changes in serum creatinine and BPb from one visit to the next (P = 0.11) [18]. The age-related increase in serum creatinine was earlier and faster in the highest when compared with the lowest quartile of the time-weighted average of lead exposure [18]. Inverse associations between renal function and the BPb concentration have also been reported in Belgium [19], Sweden [20] and Taiwan [21]. However, these studies do not allow excluding the alternative hypothesis that lead retention is a consequence rather than a cause of renal impairment.

Based on an analysis of NHANES III, Lanphear et al. [22] recently proposed that environmental exposure to lead, even at blood levels <5 μg/dL, entails a population-attributable risk of total mortality of 18.0%, which they attributed to fatal cardiovascular and coronary complications. This extrapolation assumes a causal association, which until now remains unproven. A common point of view is that hypertension explains the association of cardiovascular endpoints with lead exposure. However, our analysis of NHANES 2003–10 demonstrated weak and inconsistent associations of blood pressure with BPb [23]. This finding excludes current environmental lead exposure as a major causal contributor to hypertension in the USA [23]. In Lanphear’s report [22], associations of cardiovascular and coronary mortality with BPb remained significant after adjustment for hypertension. Lanphear et al. did not report on the association of non-cardiovascular mortality with BPb, an issue of relevance, because cardiovascular illness and renal impairment go hand-in-hand, and environmental exposure to lead might increase the vulnerability of people already at risk of chronic kidney disease [8].

An interesting finding of our study is the inverse association of the albumin–creatinine ratio with BPb. Creatinine is removed from the circulating blood primarily not only by glomerular filtration but also by proximal tubular secretion. Little or no tubular reabsorption of creatinine occurs. Small proteins that pass the glomerular sieve undergo tubular reabsorption. Lead alters renal tubular function, such as, for instance, the secretion of urate, which is a cause of lead-induced gout. As a consequence of proximal renal tubular dysfunction, lead-intoxicated children develop aminoaciduria, glycosuria or the Fanconi syndrome [24]. Our study does not allow ascertaining whether the inverse association between ACR and BPb might be explained by higher tubular reabsorption of small proteins or higher proximal tubular excretion of creatinine.

A strong point of our study was that we estimated eGFR from serum creatinine, serum cystatin C or both. Nevertheless, our present findings must be interpreted within the context of their limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small. However, in view of the wide confidence intervals for the slopes of eGFRcrt, eGFRcys and eGFRcc on BPb, it is unlikely that we missed a clinically important association. Secondly, a cross-sectional study does not allow us to make any causal inference. Although animal studies support a causal association between renal dysfunction and lead exposure [25], most of these experiments are irrelevant for human disease given the current low environmental exposure levels. Thirdly, we did not measure blood or urinary cadmium at enrolment. However, analysis of NHANES 1999–2008 data demonstrated that urinary cadmium concentrations decreased markedly between 1988 and 2008. Declining smoking rates and changes in exposure to tobacco smoke probably played an important role in the decline of environmental exposure to cadmium in the USA [26]. Finally, the low prevalence of diabetes mellitus or a history of nephrolithiasis [27] precluded an analysis of these predisposing factors as effect modifiers.

CONCLUSIONS

At the BPb levels observed in this study, we did not find any evidence for an association between renal function and lead exposure. Reverse causality, a less efficient renal function leading to lead retention, remains an issue at current exposure levels. The 2006 report of the Environmental Protection Agency [28] and the 2012 National Toxicology Programme Monograph [29] considered the evidence for reverse causality to be insufficient to explain the associations between renal outcomes and lead exposure. However, neither documents offered definite conclusions. The longitudinal follow-up renal function in exposed and mildly exposed workers in SPHERL [9] will allow this issue to be addressed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the nursing staff employed at the study sites in the USA and the expert clerical assistance of Vera De Leebeeck and Renilde Wolfs at the Studies Coordinating Centre in Leuven, Belgium.

FUNDING

The European Union (HEALTH-F7-305507 HOMAGE) and the European Research Council (Advanced Researcher Grant 2011-294713-EPLORE and Proof-of-Concept Grant 713601-uPROPHET), the European Research Area Net for Cardiovascular Diseases (JTC2017-046-PROACT) and the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, Ministry of the Flemish Community, Brussels, Belgium (G.0881.13) currently support the Research Unit Hypertension and Cardiovascular Research. The sponsors had no role in the preparation of this report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

In support of SPHERL, the Research Unit Hypertension and Cardiovascular Epidemiology received an unrestricted grant from the International Lead Association (www.ila-lead.org).

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashouri OS. Hyperkalemic distal renal tubular acidosis and selective aldosterone deficiency. Combination in a patient with lead nephropathy. Arch Intern Med 1985; 145: 1306–1307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batuman V. Lead nephropathy, gout, and hypertension. Am J Med Sci 1993; 305: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ekong EB, Jaar BG, Weaver VM.. Lead-related nephrotoxicity: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Kidney Int 2006; 70: 2074–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flora G, Gupta D, Tiwari A.. Toxicity of lead: a review with recent updates. Interdiscip Toxicol 2012; 5: 47–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H.. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 20–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gartside PS. The relationship of blood lead levels and blood pressure in NHANES II: additional calculations. Environ Health Perspect 1988; 78: 31–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pirkle JL, Brody DJ, Gunter EW. et al. The decline in blood lead levels in the United States. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). JAMA 1994; 272: 284–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muntner P, He J, Vupputuri S. et al. Blood lead and chronic kidney disease in the general population United States population: results from NHANES III. Kidney Int 2003; 63: 1044–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hara A, Gu YM, Petit T. et al. Study for promotion of health in recycling lead - rationale and design. Blood Press 2015; 24: 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Assembly of the World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Coll Dent 2014; 81: 14–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K. et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 2159–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myers GL, Miller WG, Coresh J. et al. Recommendations for improving serum creatinine measurement: a report from the laboratory working group of the National Kidney Disease Education Program. Clin Chem 2006; 52: 5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Eckardt K-U, Tsukamoto Y. et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67: 2089–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabet Care 2003; 26 Suppl 1: S5–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei FF, Drummen NEA, Schutte AE. et al. Vitamin K dependent protection of renal function in multi-ethnic population studies. EBioMed 2016; 4: 162–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang ZY, Ravassa S, Pejchinovski M. et al. A urinary fragment of mucin-1 subunit a is a novel biomarker associated with renal dysfunction in the general population. KI Rep 2017; 2: 811–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim R, Rotnitsky A, Sparrow D. et al. A longitudinal study of low-level lead exposure and impairment of renal function. The Normative Aging Study. JAMA 1996; 275: 1177–1181 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Staessen JA, Lauwerys RR, Buchet JP. et al. Impairment of renal function with increasing blood lead concentrations in the general population. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Åkesson A, Lundh T, Vahter M. et al. Tubular and glomerular kidney effects in Swedish women with low environmental cadmium exposure. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 1627–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu TN, Shen CY, Ko KN. et al. Occupational lead exposure and blood pressure. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 791–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lanphear B, Rauch S, Auinger P. et al. Low-level lead exposure and mortality in US adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018; 3: e177–e184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hara A, Thijs L, Asayama K. et al. Blood pressure in relation to environmental lead exposure in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Hypertension 2015; 65: 62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chisolm JJ Jr, Leahy NB.. Aminoaciduria as a manifestation of renal tubular injury in lead intoxication and a comparison with patterns of aminoaciduria seen in other diseases. J Pediatr 1962; 60: 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Staessen JA, Lauwerys RR, Bulpitt CJ. et al. Is a positive association between lead exposure and blood pressure supported by animal experiments? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1994; 3: 257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A, Caldwell KL. et al. Reduction in cadmium exposure in the United States population, 1988-2008: the contribution of declining smoking rates. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 120: 204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hara A, Yang WY, Petit T. et al. Incidence of nephrolithiasis in relation to environmental exposure to lead and cadmium in a population study. Environ Res 2016; 145: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Center for Environmental Assessment. Integrated Science Assessment for Lead.http://www.epa.gov/ncea/isa/lead.htm (11 August 2018, date last accessed), Research Triangle Park, NC: 2013

- 29.National Toxicology Program. Renal effects. NTP monograph on health effects of low-level lead. National Toxicology Program, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: 2012; 77–87