Abstract

Social justice is the moral imperative to avoid and remediate unfair distributions of societal disadvantage. In priority setting in healthcare and public health, social justice reaches beyond fairness in the distribution of health outcomes and economic impacts to encompass fairness in the distribution of policy impacts upon other dimensions of well-being. There is an emerging awareness of the need for economic evaluation to integrate all such concerns. We performed a systematic review (1) to describe methodological solutions suitable for integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation, and (2) to describe the challenges that those solutions face. To be included, publications must have captured fairness considerations that (a) involve cross-dimensional subjective personal life experience and (b) can be manifested at the level of subpopulations. We identified relevant publications using an electronic search in EMBASE, PubMed, EconLit, PsycInfo, Philosopher’s Index, and Scopus, including publications available in English in the past 20 years. Two reviewers independently appraised candidate publications, extracted data, and synthesized findings in narrative form. Out of 2388 publications reviewed, 26 were included. Solutions sought either to incorporate relevant fairness considerations directly into economic evaluation or to report them alongside cost-effectiveness measures. The majority of reviewed solutions, if adapted to integrate social justice concerns, would require their explicit quantification. Four broad challenges related to the implementation of these solutions were identified: clarifying the normative basis; measuring and determining the relative importance of criteria representing that basis; combining the criteria; and evaluating trade-offs. All included solutions must grapple with an inherent tension: they must either face the normative and operational challenges of quantifying social justice concerns or accede to offering incomplete policy guidance. Interdisciplinary research and broader collaborations are crucial to address these challenges and to support due attention to social justice in priority setting.

Keywords: fairness, social justice, multicriteria decision analysis, equity weighting, economic evaluation, priority setting, healthcare policy, systematic review

BACKGROUND

Economic evaluation has been defined as “the comparative analysis of alternative courses of action in terms of both their costs and consequences” (Drummond et al., 2005). It is widely used to help prioritize resource allocation for healthcare and public health. As used for these purposes, economic evaluation raises questions of social justice, the moral imperative to avoid and remediate unfair distributions of societal disadvantage (Faden & Shebaya, 2016; Powers & Faden, 2006; Wolff & de-Shalit, 2007).

Specific conceptions of unfair societal disadvantage vary across normative approaches to justice. A contemporary overview of justice and public health by Persad (2017) describes an array of influential normative approaches, many of which are pertinent to social justice in health-related economic evaluation. These approaches vary along two theoretical axes: distributive principles and metrics of justice. As Persad notes, among distributive principles, whereas the principle of maximization requires “maximiz[ing] what is available, irrespective of distribution”, other principles require certain forms of distributive outcome: the prioritarian principle “assign[s] special importance to helping those at the bottom of a distribution”; the egalitarian principle “aims to reduce inequalities in distribution”; and the sufficientarian principle “ensures that no one falls below a specified threshold”. As Persad also notes, a normative approach may conjoin any one or more of these distributive principles with any one of several metrics of justice: that is, “methodologies for quantifying and evaluating the contribution of various interventions, including public health interventions, to the achievement of a just society” (Persad, 2017). One type of metric is welfarism, focusing on distributions of ‘welfare’ understood in terms of either pleasurable mental states, satisfaction of preferences, or types of experience deemed objectively valuable (Persad, 2017, citing Parfit, 1984). Another metric is resourcism, focusing on distributions of resources. A third type of metric focuses on distributions of capabilities (that is, opportunities to function) (Nussbaum, 2006; Nussbaum, 2011; Ruger, 2010; Sen, 1993; Sen, 2009), or of actual functionings (Powers & Faden, 2006; Wolff & de-Shalit, 2007), across multiple core dimensions of well-being, of which health is one dimension on a par with the others – for instance, in the account offered by Powers and Faden (2006), personal security, reasoning, respect, attachment, and self-determination – in moral importance. This multi-dimensional type of metric, in theory, affords due salience to the ways in which social justice concerns go beyond concerns about fairness in distributions of health and income, and include concerns about fairness in distributions of personal life experience in non-health dimensions: for instance, in the dimension of respect, concerns about stigma and about discrimination against subpopulations (Faden and Shebaya, 2016).

In the absence of techniques to assess impacts of health policy and program choices upon multiple non-health dimensions of people’s experiences, the universe of social justice concerns that can be formally represented and viably deployed in health-related economic evaluation will have limited capacity to encompass many forms of cross-dimensional impact that may critically influence societal disadvantage. There is an emerging awareness of the methodological need to integrate the full range of social justice concerns into economic evaluation as used to support priority setting in healthcare and public health (Bailey et al., 2015; Beauchamp & Childress, 2013; Brock et al., 2016; Neumann et al., 2008; Powers & Faden, 2000; Zwerling et al., 2017). This awareness is informed by an earlier, critical literature on related ethical challenges in the design and use of summary population health measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (Gold et al., 2002; Whitehead & Ali, 2010).

Truly to integrate social justice concerns into economic evaluation would be to build the field’s methodological capacity toward being able to relate a fuller range of social justice concerns systematically to one another, as needed, in a single decision context. This task makes distinctive demands on methods capable of evaluating social justice concerns, and gives rise to distinctive challenges. For purposes of this review, we focused on accommodating two key characteristics. First, such concerns involve aspects of intended beneficiaries’ subjective, personal life experience potentially extending beyond health into multiple non-health dimensions of well-being. Second, within a population, they are manifested not only at the individual level but also at the level of subpopulations who suffer disproportionate adverse impacts under societal structures (Kirby et al., 2008).

Comprehensive reviews and analyses of methods incorporating equity concerns into economic evaluation have been conducted (Round & Paulden, 2017; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Sassi et al., 2001). (The concept of equity in economic evaluation involves considerations of distributive fairness such as those emphasized by the prioritarian, egalitarian, and sufficientarian distributive principles.) These systematic reviews have identified methods to consider equity concerns – for example, by assigning special importance to severity of illness on prioritarian grounds – and have characterized associated problems and obstacles. In addition, a recent overview (Cookson et al., 2017) offers valuable guidance for assessing equity impacts in the dimension of health, and for framing trade-offs between equity-focused objectives and the objective of maximizing total health improvement. The authors also provide a much-needed discussion of opportunity costs as burdens to be assessed under net equity impacts. To date, however, there has been no systematic review outlining the range of applicable methodological approaches that would be suitable specifically for assessing fairness in the distribution of policy impacts upon people’s experiences in multiple non-health dimensions of well-being.

To fill this gap, this systematic review aims to consolidate accumulated knowledge on potentially viable methodological approaches. To do so, first, we identify existing methodological solutions that would be suitable for adaptation to integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation. Second, we characterize and analyze the challenges traditionally faced by those solutions in their prior implementation.

METHODS

Data sources and identification of publications

In November 2015, we conducted a comprehensive search for publications available from January 1, 1995 through November 26, 2015. After determining search terms through an iterative process, we searched the following databases: PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, EconLit with Full Text, Philosopher’s Index, and Scopus. Study identification required the presence of a term or controlled vocabulary item from each of three blocks: (1) economic evaluation; (2) ethical theory; and (3) priority setting or resource allocation. Full details of the search strategy are presented in an additional file [see Supplemental file 1].

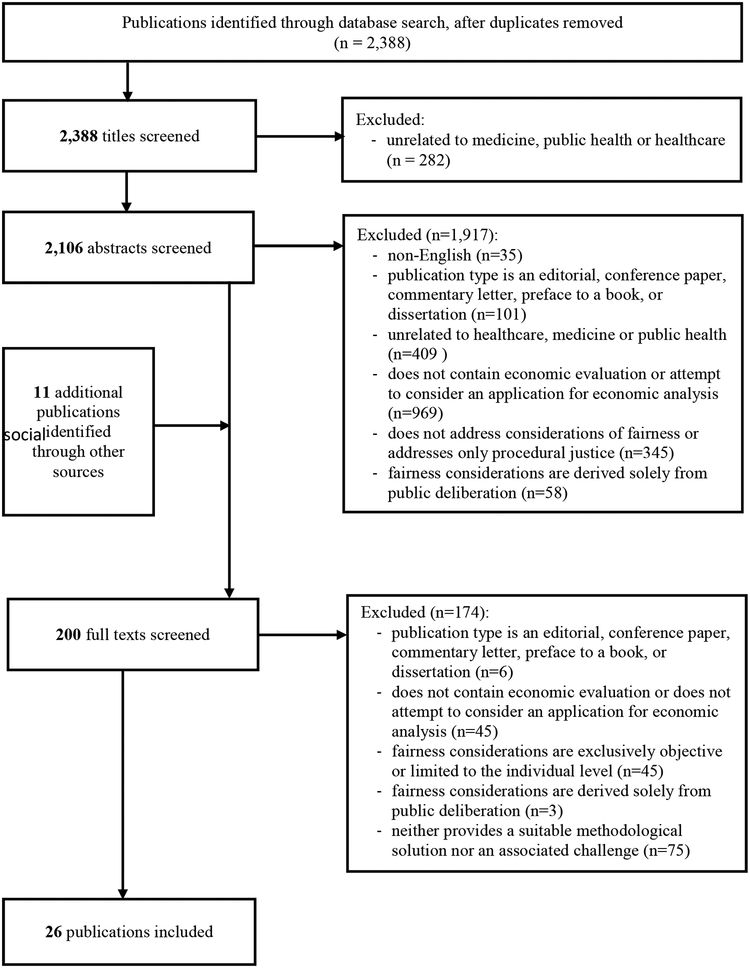

In parallel, we identified grey literature and additional material by searching the websites of relevant health economic and health governance agencies [complete listing provided in Supplemental file 2]. We also examined the bibliographies of reviewed publications to identify further material. We excluded non-English publications, as well as conference papers and abstracts, dissertations, editorials, commentaries, and book prefaces. After combining search results and manually removing duplicates, we identified a total of 2,388 publications for review.

Selection of publications

The sequential review procedure is illustrated in Figure 1. Two independent reviewers screened titles and, subsequently, abstracts and full texts for eligibility against the exclusion criteria, resolving inter-reviewer disagreement through discussion. We excluded publications that were unrelated to medicine, healthcare, or public health. To be included, publications needed either to contain actual economic evaluation (e.g., cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis) or consider the application of theory for economic analysis. In order to accommodate the two key characteristics of social justice concerns under-represented in economic evaluation to date, we also required publications to capture fairness considerations that (a) involve intended beneficiaries’ cross-dimensional subjective personal life experience and (b) can be manifested at the level of subpopulations. Accordingly, publications were not eligible if they addressed fairness considerations that were exclusively objective in nature (such as age or income quintiles) or limited to the individual level.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing selection of publications

Inclusion eligibility was dependent on the provision of a methodological solution or characterization of an associated challenge. To be included, solutions must have been used for, or must have been described as suitable for, integrating fairness considerations that share key characteristics (a) and (b) above. Similarly, challenges must have been associated with an identified solution and discussed in the context of fairness. Publications that pertained only to procedural justice did not meet the inclusion criterion because they did not essentially aim to describe methodological solutions or challenges for representing, in economic evaluation, any particular normative commitments to distributive principles or metrics of justice; rather, they described procedures for discussion, deliberation, and decision that would take such normative commitments as inputs to the reasonable disagreements that procedural justice is called upon to resolve fairly. We excluded on the same grounds publications whose discussions of fairness were derived solely from public deliberation.

Data abstraction and qualitative analysis

Each reviewer independently extracted verbatim passages pertaining either to methodological solutions or to associated challenges. We then employed a data-driven thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The reviewers worked together to first identify descriptive themes in the extracted data and then collate descriptive themes to reflect emerging analytic patterns (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The themes were later checked against both the extractions and the full texts they were extracted from. The findings were synthesized in narrative form. Because of the nature of the reviewed publications, standard procedures to assess study quality were not applicable.

RESULTS

Our systematic database search identified 2,388 unique publications, of which 26 were included (Figure 1). Of these publications, six presented methodological solutions suitable for integrating social justice concerns (Asaria et al., 2015a; Attema, 2015; Baltussen & Niessen, 2006; Goetghebeur et al., 2010; Rotter et al., 2012; Stinnett & Paltiel, 1996), eight presented challenges associated with those solutions (Baltussen et al., 2013; Dowie, 2001; Meltzer & Smith, 2011; Norheim et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2009; Richardson, 2009; Sussex et al., 2013; Whitty et al., 2014), and 12 presented both (Asaria et al., 2015b; Baeten et al., 2010; Bleichrodt et al., 2004; Cookson et al., 2009; Coyle et al., 2003; Drummond et al., 2009; James et al., 2005; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Mortimer, 2006; Sassi et al., 2001; Strømme et al., 2014; Wailoo et al., 2009). Our narrative of results is organized thematically, first considering solutions and then considering challenges.

Overview of methodological solutions

We identified a number of methodological solutions that may be suitable for integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation. While none of the reviewed solutions were developed with that specific purpose, all were either used or described as adaptable for incorporating fairness considerations that share both key characteristics of interest.

As a part of our analysis, we classified methodological solutions into two broad approaches: ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’. Direct approaches incorporated fairness considerations into the economic analysis by, for example, imposing weights or constraints. Indirect approaches, however, made no attempt to modify the economic analysis calculations. Instead, they reported fairness considerations alongside the economic analysis, allowing for discrete comparisons within the final fairness-informed economic evaluation.

Importantly, the distinction between ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ approaches turns not on whether fairness considerations are quantified, but rather on whether they are incorporated into the primary economic analysis (‘direct’) or not (‘indirect’). Furthermore, while most solutions largely followed one of these two broad approaches, these approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive; for example, an analysis that largely incorporates fairness considerations directly into its primary analysis (‘direct’) could also present the results of that fairness analysis separately (‘indirect’).

Direct approaches

Equity weighting

Five publications proposed utilizing weights to value outcomes differently based on equity criteria that reflect considerations of fairness for subpopulations (Attema, 2015; Drummond et al., 2009; Mortimer, 2006; Sassi et al., 2001; Wailoo et al., 2009). For instance, Drummond and colleagues (Drummond et al., 2009) described equity weighting as a methodology to evaluate concerns that accrue “to people with different equity-relevant characteristics, based on values elicited from a relevant stakeholder group”.

In equity weighting, a direct trade-off between efficiency and the chosen weighting criterion is quantified in the cost-effectiveness units. Attema (Attema, 2015) additionally highlighted that the weights for gains and loses should be estimated separately to account for inequity aversion.

Bleichrodt and colleagues in their variation of equity weighting – the rank-dependent QALY model – proposed assigning various groups of individuals a rank (weight) in the evaluation of their QALY profile (outcome measure) (Bleichrodt et al., 2004). Baeten and colleagues discussed the point that the model allows assigning extra weights for those worst-off, thus enabling comparisons at the level of disadvantaged subpopulations (Baeten et al., 2010).

Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis

Asaria and co-authors (Asaria et al., 2015a; Asaria et al., 2015b) proposed distributional cost-effectiveness analysis to provide differential estimations of health effect and health opportunity cost impact by subpopulation. This breakdown of subpopulations by those who gain and who lose can be aggregated into a summary measure in the same analysis, and then evaluated against the impact on the general population to present explicit trade-offs. The authors described the subpopulation impacts using health quantile groups defined objectively, at the same time highlighting that quantiles can be defined in various ways.

Mathematical programming

Three publications proposed mathematical (or linear) programming to create an outcome maximization framework defined by constraints that address fairness considerations (Drummond et al., 2009; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Stinnett & Paltiel, 1996). By conducting economic evaluation with and without constraints, the trade-off between efficiency and imposed criteria (constraints) is calculated directly in the cost-effectiveness units. This approach looks at the cost of equity (due to the equity constraint) but does not attempt to value equity. Various considerations can be applied as constraints, including the sets of criteria that define those worst-off (Stinnett & Paltiel, 1996). Johri and Norheim discussed mathematical programming as a methodology enabling the addition of “neglected distributional concerns” into economic evaluation (Johri & Norheim, 2012).

Stratified cost-effectiveness analysis

Coyle and colleagues (Coyle et al., 2003) introduced a method for incorporating considerations of equity by stratifying cost-effectiveness results by population group and then considering variability between them. The authors theorized that the method can be applied for any potential stratification criteria. Stratified cost-effectiveness analysis explicitly quantifies the trade-off between efficiency and the imposed consideration chosen as a stratification criterion.

Indirect approaches

Included indirect approaches comprised variations of multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA). Six publications discussed utilizing a form of MCDA to integrate considerations of fairness in economic evaluation by presenting them as additional criteria alongside cost-effectiveness measures. (Baltussen & Niessen, 2006; Goetghebeur et al., 2010; James et al., 2005; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Rotter et al., 2012; Strømme et al., 2014). Strømme and colleagues, for example, proposed that under MCDA those worst-off can be “identified by a composite set of multiple criteria” (Strømme et al., 2014).

Our analysis identified two principal techniques to analyze MCDA results: qualitative and quantitative. Under qualitative comparison, alongside cost-effectiveness units, the impacts of a given criterion are described in narrative form without cross-criteria numerical ranking. Under quantitative comparison, the impacts of a given criterion are (1) quantified and (2) calculated against other criteria or cost-effectiveness units. It is also possible to perform an initial quantification of qualitative data without assigning relative weights to the criteria; in other words, results can present (1) without (2). While Baltussen and Niessen considered such analyses as cases of qualitative comparison (Baltussen & Niessen, 2006), we instead refer to them as a mixed comparison.

Under MCDA with quantitative comparison, trade-offs between the criteria are reflected in assigned relative weights and are expressed in units of each criterion. For qualitative and mixed comparison, trade-offs are not calculated and their resolution will rely on further value judgments by policymakers.

Overview of associated challenges

All of the methodological solutions faced significant challenges, spanning both normative and operational aspects. This systematic review identified four broad challenges related to the implementation and adoption of these solutions.

Clarifying the normative basis

Eleven publications discussed challenges related to clarifying a normative basis for the integration of ethically important criteria, including considerations of fairness. These challenges were relevant to all methodological solutions, and stem from two critical steps: determining what ethical commitments must be made; and selecting measurable criteria to represent those commitments in the context of economic evaluation. Regarding the first step, it was common for authors to discuss difficulties related to the multiplicity and conceptual complexity of ethical considerations (Cookson et al., 2009; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Meltzer & Smith, 2011; Norheim et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2009; Richardson, 2009; Strømme et al., 2014). Norheim and colleagues identified the “lack of a widely accepted normative source on which to ground controversial value choices” as a key impediment to the use of these techniques in decision making, alluding to the substantial disagreement over ethical commitments (Norheim et al., 2014). Others discussed uncertainty about ethical characteristics (Wailoo et al., 2009).

Even once a framework had been agreed upon, analysts faced difficulties when translating it into a set of assessable criteria reflecting its theoretical basis. Baltussen and Niessen described the complexity of this task, explaining how criteria must be selected in order “to assure completeness, feasibility, and mutual independence, and avoid redundancy and an excessive number of criteria” (Baltussen & Niessen, 2006). Several articles discussed the particular challenge of determining the ideal number of criteria to incorporate (Cookson et al., 2009; Dowie, 2001; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Mortimer, 2006; Richardson, 2009). A set comprised of too few criteria will fail to be exhaustive; and may ignore important ethical concerns. A set comprised of too many, on the other hand, not only runs the risk of substantially complicating the analysis, but also may result in overlap, which some consider to be evidence of an unclear relationship to the underlying normative theory (Johri & Norheim, 2012).

Measuring the selected criteria and determining their relative importance

Many publications reported challenges related to measurement and valuation: the measurement of criteria selected to represent ethical considerations (including fairness); and, for methods also requiring weights or ranks, the explicit valuation of their relative importance. Several authors noted that the comprehensive and high-quality evidence base necessary to define accurate measurements does not exist (Cookson et al., 2009; Drummond et al., 2009; Meltzer & Smith, 2011; Sassi et al., 2001; Sussex et al., 2013; Wailoo et al., 2009). Moreover, such evidence is likely to remain insufficient in the future given its potentially high cost and lack of availability (Sassi et al., 2001), especially in resource-limited settings. Beyond the lack of data to support measurements, there was also substantial methodological uncertainty and disagreement over where to derive estimations and preferences (Baltussen et al., 2013; Coyle et al., 2003; James et al., 2005; Meltzer & Smith, 2011; Sassi et al., 2001; Sussex et al., 2013; Wailoo et al., 2009; Whitty et al., 2014) for weighing them. James and colleagues pointed out that although it is generally agreed that weights should be derived from “empirical investigations”, the relative importance they reflect is inherently normative, and there is no decisive opinion on where they should come from (James et al., 2005). There was also concern over the trade-off between “greater generality and practical applicability” (Bleichrodt et al., 2004), given that certain measurements or preferences, particularly weights that may be dependent on value judgments, may be context-specific (Baeten et al., 2010; Whitty et al., 2014).

Combining the criteria

Our review identified a number of publications concerned with challenges related to combining variables. Because they are relevant only for solutions that involve several criteria, these challenges were most frequently discussed in the context of equity weighting or quantitative MCDA. While some authors described the practical difficulties of incorporating an increasing number of (weighted) variables (Dowie, 2001), others described the challenges of losing information and distinguishing detail by attempting to combine diverse criteria into broadly aggregated outcome measures (Baeten et al., 2010). Several publications discussed the imminent challenges of “overlap” and interaction between variables, often noting the lack of evidence for estimating and mitigating these effects (James et al., 2005; Johri & Norheim, 2012; Mortimer, 2006; Wailoo et al., 2009). Mortimer described the possibility of “perverse priorities” that may arise if calculations are applied piece-meal or criteria are combined in ways that fail to account adequately for inter-variable effects (Mortimer, 2006). There was some doubt that a coherent allocation would even be feasible (Dowie, 2001; Mortimer, 2006; Sassi et al., 2001).

Evaluating trade-offs

Four publications discussed challenges associated with determining what level of overall health should (or should not) be forgone in order to achieve other goals, such as equity. Drummond and colleagues, for instance, warned that although certain methods manage to quantify trade-offs, they do “not help the decision maker decide how large a… sacrifice is worth making in order to pursue a particular equity consideration” (Drummond et al., 2009). Sussex and colleagues further discussed the challenges that arise from making decisions based on value judgment (Sussex et al., 2013).

On the other hand, Baltussen and colleagues argued that certain decisions simply cannot be adequately captured by analytical processes (Baltussen et al., 2013). Similarly, Johri and Norheim expressed a worry “that the aggregation function used to construct the final ranking is empirically and statistically driven rather than being based on cultivation of judgment” (Johri & Norheim, 2012).

DISCUSSION

Applying suitable solutions

This review identified several solutions capable of integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation, which we have classified into two types of approach: (i) direct approaches – equity weighting, mathematical programming, stratified cost-effectiveness analysis, and distributional cost-effectiveness analysis; and (ii) indirect approaches – MCDA employing either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed comparison. While none of the reviewed solutions were specifically developed or used to integrate social justice concerns – in the sense of being able systematically relate a full range of social justice concerns to one another – they all demonstrate the potential to do so (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of potential ways to integrate social justice concerns into economic evaluation

| Solution | Potential way to integrate social justice concerns | Social justice input required |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Direct’ approaches | ||

| Equity weighting (rank-dependent QALY model) | Express as weights (for gains and losses) or as ranks of outcome profiles | Prior to the analysis, the magnitude of weights or ranks should be explicitly stated |

| Distributional CEA | Use as the basis to formulate inequality quantiles for which opportunity cost and outcome impact are formed | Inequality quantiles should be identified to initiate empirical estimation of differential distributions |

| Mathematical/linear programming | Transform into constraints used in the programming formulation | Requires constraints to be explicitly, algebraically formulated to initiate the programming |

| Stratified CEA | Use as the basis to define strata for which cost-effectiveness is considered separately | Entails that strata are a priori defined to obtain necessary input |

| ‘Indirect’ approaches | ||

| MCDA with quantitative comparison | Determine criteria and their relative importance against other criteria and cost-effectiveness | Operationalization and quantification of considerations, explicitly assigning relative importance |

| MCDA with mixed comparison | Set quantified criteria; however, without numerical comparison against cost-effectiveness | Quantification of considerations and their assessment (possibly implicit) against others in a qualitative manner |

| MCDA with qualitative comparison | Form criteria that are reported in narrative form alongside cost-effectiveness | Narrative description of decided criteria and their qualitative appraisal (possibly implicit) against other criteria |

CEA: Cost-effectiveness analysis; MCDA: Multicriteria decision analysis; QALY: Quality-adjusted life year

A key distinction between direct and indirect approaches relates to their requirements for social justice input (Table 1). Direct approaches would require explicit quantification of social justice considerations as a part of the economic analysis. Indirect approaches vary in this regard. For MCDA with a quantitative comparison, the input might be considered after the economic analysis, but would still need to be explicit and quantified. For MCDA with a mixed comparison, the considerations should be quantified and might be considered after the economic analysis, but their appraisal against other criteria will rely on further value judgments. For MCDA with a qualitative comparison, they might be considered after the economic analysis, but be non-mathematical and similarly rely on further value judgments.

Direct and indirect approaches must both reckon with a fundamental tension in any economic evaluation, namely the tradeoffs that must be considered in the face of scarce resources. For example, those who might benefit (either from an economic or social justice perspective) from a given intervention may be more readily identifiable than those who might bear the opportunity cost – and these opportunity costs may be different when considered through economic versus social justice lenses.

The 2017 guide by Cookson and colleagues on using cost-effectiveness analysis to address health equity concerns proposes a more nuanced classification, which we endorse, of solutions identified as direct approaches (Cookson et al., 2017). Following this guide’s recommendations, quantified social justice input could be presented within a range and with variations allowing for sensitivity analysis. Similarly, the value judgments for MCDA with a qualitative comparison could constitute several alternatives allowing for sensitivity analysis and exploring ramifications.

Emerging solutions

This review also identified solutions that have potential to integrate social justice considerations but have not been yet discussed in that regard. One example of such a solution is extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA), whose distributional analysis of benefits by subpopulation has been used to date only for objective criteria, such as income quantile, geographic location, ethnicity, sex, or objectively-measured severity of illness (Cookson et al., 2017; Verguet et al., 2016). The authors state, however, that the definition and selection of subgroups depends on equity and distributional issues posed by the analysts (Verguet et al., 2016). Accordingly, ECEA could represent a suitable solution for purposes of this review. Another example is the production of outcome measures based on the capability approach (Al-Janabi et al., 2012; Flynn et al., 2011; Lorgelly et al., 2015; Simon et al., 2013). Notably, Mitchell and colleagues have developed a method to apply a capability-based approach on the benefit side of economic evaluation; however, the considerations on the costing side have not yet been addressed (Mitchell et al., 2015). Thus, to date, these methodologies have not described exactly how capability-based approaches will replace or supplement the units of cost-effectiveness. Such incorporation would likely still face some of the challenges identified in this review.

Mitigating identified challenges

Our review highlighted several challenges inhibiting the use of these solutions, including clarifying the normative basis; measuring and weighting the selected criteria; combining the criteria; and evaluating trade-offs (Table 2). Understanding and mitigating these challenges is a critical step toward successfully adapting solutions to integrate social justice concerns into economic evaluation.

Table 2.

Review of challenges associated with approaches to integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation

| Challenge | ‘Direct’ approaches | ‘Indirect’ approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Clarifying the normative basis | Requires consensus; Criteria must be exhaustive, assessable, and mutually exclusive criteria, and reflective of the acceptable theoretical framework | |

| Measuring selected criteria | Criteria must be numerical; expected standards are similar to those for standard economic evaluation data | Depending on type of comparison, criteria can be descriptive, binary, ordinal, or numerical |

| Determining relative importance of criteria | Relative importance must be expressed algebraically a priori to analysis | For qualitative and mixed MCDA, the determination of relative importance is delayed and can be implicit For quantitative MCDA, relative importance must be expressed algebraically a priori to appraisal |

| Combining criteria | Operational challenges in computation and concern about potential interaction | Concern about potential interaction |

| Evaluating trade-offs | Guidance must be explicitly expressed in cost-effectiveness units | For qualitative and mixed MCDA, tradeoffs require value judgment For quantitative MCDA, guidance must be explicitly expressed in units of all criteria |

MCDA: Multicriteria decision analysis

One barrier that all solutions will need to overcome is to clarify a normative basis for social justice considerations. The findings from our review are consistent with other literature noting a disconnect between ethicists and economists in public health: most frameworks proposed for public health ethics do not offer practical guidance for relating normative considerations to empirical evidence (Assasi et al., 2015; Marckmann et al., 2015). Marckmann and colleagues recently responded to this challenge by proposing a systematic and practice-oriented ethical framework that “ties together ethical analysis and empirical evidence” (Marckmann et al., 2015). In the context of healthcare resource allocation, Lane and colleagues recently proposed an “operational definition of equity framework”, enabling decision-makers to be more explicit in defending their normative commitments (Lane et al., 2017).

Challenges and concerns regarding the multiplicity of ethical commitments undoubtedly stem from widespread disagreement over ethical considerations. There is no single consensus view on a normative basis for integrating social justice concerns into priority setting. Nonetheless, Bailey and colleagues (Bailey et al., 2015) have recently drawn on leading philosophical theories to develop a core framework of social justice for use as a supplement to traditional economic evaluation. Such a framework may provide an acceptable normative basis for the incorporation of social justice considerations.

Solutions must also address how to measure and weigh social justice criteria, and how to combine them. Measurement is crucial for solutions that require explicit quantification: direct approaches, quantitative MCDA, and mixed MCDA. While all solutions require some source of data to provide measurements for justice considerations, direct approaches would be further expected to meet the rigorous standards required of traditional economic evaluation criteria, such as cost, utility, and probability and level of certainty. Moreover, direct approaches and quantitative MCDA also require an explicit algebraic quantification of the various considerations’ relative importance.

In instances where multiple variables are to be accounted for, there is an additional challenge of combining these variables without allowing their interaction or overlap to over- or under-account for any one consideration. As other scholars have noted, the most pressing challenge in equity weighting when a multi-attribute equity system is used lies in identifying those who bear the opportunity costs and estimating values of their total burden (Round & Paulden, 2017).

Finally, solutions should address the need to evaluate trade-offs between social justice objectives and other objectives. While direct approaches are capable of quantifying and presenting such trade-offs in cost-effectiveness units, permitting clear comparisons and potentially informing explicit guidance, indirect approaches do so in varied units, tending to result in comparisons that are less clear, and guidance that is less explicit. Despite having been neglected by the majority of included publications, the challenge of evaluating trade-offs clearly requires significant attention.

In both direct and indirect approaches, the need to quantify relative importance and evaluate trade-offs will often require some type of value judgment. For solutions adopting direct approaches, tradeoffs emerge earlier in the process. Indirect approaches face less daunting challenges related to evaluating trade-offs throughout the analysis, but greater challenges related to evaluating the final trade-off and making an acceptable decision. In both cases, the validity and appropriate sources of various judgments are highly contested. Our findings were consistent with others, who have cautioned that different decision-makers tend to evaluate trade-offs differently (Brouwer & Koopmanschap, 2000; Field & Caplan, 2012). Value judgments themselves may thus be a limitation if they lead to inconsistency, either between contexts or among stakeholder preferences.

Emerging challenges

Beyond those that were extracted, additional challenges emerged as the reviewed publications were compared and synthesized. One major finding is the lack of agreement with regard to who should be making decisions, for example, when determining ethical commitments, selecting measurable criteria, assigning relative importance to those criteria, or evaluating trade-offs (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health, 2006; Cookson et al., 2009; Norheim et al., 2014; Richardson, 2009; Sassi et al., 2001).

Although the reviewed solutions were designed to inform decision making, there is concern that their normative and operational complexities will prevent decision-makers from fully understanding them. This concern is consistent with the views of other authors who have expressed doubt over decision-makers’ abilities to assess ethical considerations appropriately (Wikler et al., 2007). Uptake of any one of these solutions will require it not only to present comparisons accurately, but also to do so in a manner useful to decision-makers.

Implications for Policy

Policymakers must often weigh one alternative that is preferred from an economic perspective against another alternative that is preferred from the perspective of social justice. According to some ideals of clarity in policy guidance, analyses would need to quantify social justice considerations in numerical terms that can be compared with the outputs of economic evaluation. But doing so is associated with the described challenges. Approaches that forgo such quantification may be more appealing, but such approaches implicitly require stakeholders to make value judgments in order to choose between these alternatives. Explicit elicitation of these value judgments, either from policymakers or the public, engenders its own set of challenges (Gu et al., 2015; Johri & Norheim, 2012). All methodological approaches discussed here must therefore grapple with an inherent tension: they must either face the normative and operational challenges of quantifying social justice concerns (in terms of comparison to economic outcomes or elicitation of societal value judgments) or accede to offering incomplete policy guidance.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. Firstly, because we included publications only if they described a suitable methodological solution for integrating fairness considerations that involve intended beneficiaries’ cross-dimensional subjective personal life experience and can be manifested at the level of subpopulations, we may have missed additional solutions in the broader literature that are potentially suitable, but have not yet been discussed in that regard. Examples of such potential solutions are extended cost-effectiveness analysis and the production of outcome measures based on the capability approach, both described above as emerging solutions. Similarly, while certain studies discussing ethical frameworks – for example those summarized by Assasi and colleagues – do address relevant fairness considerations, they do not present a concrete methodological solution for their incorporation and comparison against cost-effectiveness measures (Assasi et al., 2014; Heintz et al., 2015; Hofmann, 2005; Kirby et al., 2008). If a more explicit methodology were developed, such solutions might present an alternative indirect approach beyond MCDA. Our choice not to include publications pertaining only to procedural justice or public deliberation might be seen as another limiting factor. As a mitigating point, while participatory methods inspired by public deliberation are used in some decision-making processes to deal with social justice concerns, they don’t extend to questions about integrating such concerns into economic evaluation (Bombard et al., 2011; Cotton, 2014).

Secondly, this review may not have uncovered the full set of challenges hampering the use of identified solutions for the integration of social justice concerns. We looked for challenges generally concerning the integration of certain fairness considerations, assuming that they would similarly apply when considering social justice more specifically. Nevertheless, there may be unaccounted-for differences between the two applications, and social justice considerations may pose additional challenges not yet encountered or described. Moreover, the identified challenges might not represent a complete real-world spectrum. Among the reviewed publications, aside from certain practical examples – employing MCDA with qualitative (Goetghebeur et al., 2010) or quantitative (Strømme et al., 2014) comparison, or distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (Asaria et al., 2015a) – the application of methodologies was predominantly hypothetical.

Finally, we reviewed only publications available in English and did not consider methodologies of incorporating social justice in economic evaluation outside healthcare and public health. The varied reporting styles of included publications prevented us from using a standardized abstraction form and assessing publication quality. We sought to mitigate the latter limitations by using an iterative process involving multiple researchers during data abstraction and synthesis.

Conclusions

By systematically reviewing existing methodologies, we identified a number of solutions suitable for integrating the full range of social justice concerns into economic evaluation for healthcare and public health. Those solutions, whether they directly incorporate justice considerations or appraise the considerations alongside cost-effectiveness evaluations, face significant challenges encompassing both normative and operational aspects. Moreover, there is a lack of agreement about who should be making the corresponding normative and operational decisions. When used for making policy decisions, these methodological solutions must also grapple with an inherent tension between the challenges of quantifying social justice considerations and the desire to provide clear policy guidance.

These findings suggest that while viable solutions for integrating social justice concerns into economic evaluation exist, their successful adoption will require concerted efforts to address associated challenges and the inherent tension. Future research should focus on how to deploy substantive ethical frameworks and operationalize empirical input. Interdisciplinary research and broader collaborations amongst other stakeholders will be critical steps in supporting decision making that can formally take social justice more fully into account.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Priority setting in healthcare impacts the distribution of societal disadvantages

We review methods suitable for integrating social justice into economic evaluation

Suitable methodological solutions face normative and operational challenges

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful to C. Simone Sutherland and Fabrizio Tediosi for their valuable contributions to discussion at early stages of this review and to Margaret Gross for her help with devising the search strategy. The authors would also like to thank Michael DiStefano and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on drafts of this manuscript.

List of Abbreviations

- CEA

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life year

- ECEA

Extended cost-effectiveness analysis

- MCDA

Multicriteria decision analysis

- QALY

Quality-adjusted life year

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental files

Electronic search strategies for reviewed databases

List of searched grey literature sources and used search options

References

- Al-Janabi H, Flynn T, & Coast J, 2012. Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: The ICECAP-A. Qual Life Res. 21(1), 167–176. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9927-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaria M, Griffin S, Cookson R, Whyte S, & Tappenden P, 2015a. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis of health care programmes - A methodological case study of the UK bowel cancer screening programme. Health Econ. 24(6), 742–754. doi: 10.1002/hec.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaria M, Griffin S, & Cookson R, 2015b. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis: A tutorial. Med Decis Making. 36(1), 8–19. doi:0272989X15583266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assasi N, Schwartz L, Tarride JE, O’Reilly D, & Goeree R, 2015. Barriers and facilitators influencing ethical evaluation in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 31(3), 113–23. doi: 10.1017/S026646231500032X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assasi N, Schwartz L, Tarride JE, Campbell K, & Goeree R, 2014. Methodological guidance documents for evaluation of ethical considerations in health technology assessment: A systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 14(2), 203–20. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.894464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attema AE, 2015. Incorporating sign-dependence in health-related social welfare functions. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 15(2), 223–8. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.995170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten S, Baltussen R, Uyl-de Groot C, Bridges J, & Niessen L, 2010. Incorporating equity-efficiency interactions in cost-effectiveness analysis-three approaches applied to breast cancer control. Value Health. 13(5), 573–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TC, Merritt MW, & Tediosi F, 2015. Investing in justice: Ethics, evidence, and the eradication investment cases for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Am J Public Health. 105(4), 629–36. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltussen R, Mikkelsen E, Tromp N, Hurtig A, Byskov J, Olsen T, … Norheim OF, 2013. Balancing efficiency, equity and feasibility of HIV treatment in South Africa - development of programmatic guidance. Cost Eff Resour Allocat. 11(1), 26. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltussen R, & Niessen L, 2006. Priority setting of health interventions: The need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff Resour Allocat. 4, 14. doi:1478-7547-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp TL, & Childress JF, 2013. Principles of Biomedical Ethics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichrodt H, Diecidue E, & Quiggin J, 2004. Equity weights in the allocation of health care: The Rank-dependent QALY model. J Health Econ. 23(1), 157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombard Y, Abelson J, Simeonov D, & Gauvin F, 2011. Eliciting ethical and social values in health technology assessment: A participatory approach. Soc Sci Med. 73(1), 135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brock DW, Daniels N, Neumann PJ, & Siegel JE, 2016. Ethical and distributive considerations In: Neumann PJ, Ganiats TG, Russell LB, Sanders GD, and Siegel JE (Eds.), Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine (2nd ed). Oxford University Press, New York. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190492939.003.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer WB, & Koopmanschap MA, 2000. On the economic foundations of CEA. Ladies and gentlemen, take your positions! J Health Econ. 19(4), 439–59. doi:S0167-6296(99)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2006. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada [3rd edition]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Cookson R, Drummond M, & Weatherly H, 2009. Explicit incorporation of equity considerations into economic evaluation of public health interventions. Health Econ Policy Law. 4(2), 231–45. doi: 10.1017/S1744133109004903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson R, Mirelman AJ, Griffin S, Asaria M, Dawkins B, Norheim OF, … Culyer A, 2017. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to address health equity concerns. Value Health. 20(2), 206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton M, 2014. Ethics and technology assessment: A participatory approach. Studies in Applied Philosophy, Epistemology and Rational Ethics (vol. 13). Springer, New York and Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle D, Buxton MJ, & O’Brien BJ, 2003. Stratified cost-effectiveness analysis: A framework for establishing efficient limited use criteria. Health Econ. 12(5), 421–7. doi: 10.1002/hec.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowie J, 2001. Analysing health outcomes. J Med Ethics. 27(4), 245–50. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddart G, 2005. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edition Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, Weather H, Claxton K, Cookson R, Ferguson B, Godfrey C, … Sowden A, 2009. Assessing the challenges of appling standard methods of economic evaluation to public health interventions. Public Health Research Consortium; Available from: http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/papers/PHRC_D1-05_Final_Report.pdf. [Accessed April, 19 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- Faden R, & Shebaya S, 2016. Public Health Ethics In Zalta EN. (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.). Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/publichealth-ethics/. [Accessed November 22, 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- Field RI, & Caplan AL, 2012. Evidence-based decision making for vaccines: The need for an ethical foundation. Vaccine, 30(6), 1009–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn TN, Chan P, Coast J, & Peters TJ, 2011. Assessing quality of life among British older people using the ICEPOP CAPability (ICECAP-O) measure. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 9(5), 317–29. doi: 10.2165/11594150-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebeur MM, Wagner M, Khoury H, Rindress D, Gregoire JP, & Deal C, 2010. Combining multicriteria decision analysis, ethics and health technology assessment: Applying the EVIDEM decision-making framework to growth hormone for turner syndrome patients Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 8, 4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MR, Stevenson D, & Fryback DG, 2002. HALYS and QALYS and DALYS, oh my: Similarities and differences in summary measures of population health. Annu Rev Public Health. 23, 115–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Lancsar E, Ghijben P, Butler JRG, & Donaldson C, 2015. Attributes and weights in health care priority setting: A systematic review of what counts and to what extent. Soc Sci Med, 146, 41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz E, Lintamo L, Hultcrantz M, Jacobson S, Levi R, Munthe C, … Sandman L, 2015. Framework for Systematic Identification of Ethical Aspects of Healthcare Technologies: The SBU Approach. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 31(3), 124–30. doi: 10.1017/S0266462315000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann B, 2005. Toward a procedure for integrating moral issues in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 21(3), 312–8. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, Carrin G, Savedoff W, & Hanvoravongchai P (2005). Clarifying efficiency-equity tradeoffs through explicit criteria, with a focus on developing countries. Health Care Anal. 13(1), 33–51. doi: 10.1007/s10728-005-2568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri M, & Norheim OF, 2012. Can cost-effectiveness analysis integrate concerns for equity? systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 28(2), 125–32. doi: 10.1017/S0266462312000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J, Somers E, Simpson C, & McPhee J, 2008. The public funding of expensive cancer therapies: Synthesizing the “3Es”--evidence, economics, and ethics. Organ Ethic. 4(2), 97–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H, Sarkies M, Martin J, & Haines T, 2017. Equity in healthcare resource allocation decision making: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 175, 11–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorgelly PK, Lorimer K, Fenwick EAL, Briggs AH, & Anand P, 2015. Operationalising the capability approach as an outcome measure in public health: The development of the OCAP-18. Soc Sci Med. 142, 68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marckmann G, Schmidt H, Sofaer N, & Strech D, 2015. Putting public health ethics into practice: A systematic framework. Front Public Health. 3, 23. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer DO, & Smith PC, 2011. Theoretical issues relevant to the economic evaluation of health technologies In Pauly MV, Mcguire TG, Barros PP (Eds.), Handbook of Health Economics (pp. 433–469). Elsevier, North Holland. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53592-4.00007-4, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PM, Roberts TE, Barton PM, & Coast J, 2015. Assessing sufficient capability: A new approach to economic evaluation. Soc Sci Med. 139, 71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer D, 2006. The value of thinly spread QUALYs. PharmacoEconomics, 24(9), 845–53. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Jacobson PD, & Palmer JA, 2008. Measuring the value of public health systems: The disconnect between health economists and public health practitioners. Am J Public Health. 98(12), 2173–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norheim OF, Baltussen R, Johri M, Chisholm D, Nord E, Brock D, … Wikler D, 2014. Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-health): The inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 12, 18. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC, 2006. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. The Belknap Press, Cambridge, Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC, 2011. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Ong KS, Kelaher M, Anderson I, & Carter R, 2009. A cost-based equity weight for use in the economic evaluation of primary health care interventions: Case study of the Australian indigenous population. Int J Equity Health. 8, 34. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfit D, 1984. Appendix I in Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Persad G, 2017. (forthcoming). Justice and Public Health [working title] In Kahn J, Kass N and Mastroianni A. (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powers M, & Faden R, 2000. Inequalities in health, inequalities in health care: Four generations of discussion about justice and cost-effectiveness analysis. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 10(2), 109–27. doi: 10.1353/ken.2000.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M, & Faden R, 2006. Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy. Oxford University Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, 2009. Is the incorporation of equity considerations into economic evaluation really so simple? A comment on Cookson, Drummond and Weatherly. Health Econ Policy Law. 4, 247–54. doi: 10.1017/S1744133109004927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JS, Foerster D, & Bridges JF, 2012. The changing role of economic evaluation in valuing medical technologies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res, 12(6), 711–23. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J, & Paulden M, 2017. Incorporating equity in economic evaluations: A multi-attribute equity state approach. Eur J Health Econ. 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10198-017-0897-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruger JP, 2010. Health and Social Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Sassi F, Archard L, & Le Grand J, 2001. Equity and the economic evaluation of healthcare. Health Technol Assess. 5(3), 1–138. doi: 10.3310/hta5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, 1993. Capability and well-being In Nussbaum MC & Sen A (Eds.). The Quality of Life. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, 2009. The Idea of Justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Anand P, Gray A, Rugkåsa J, Yeeles K, & Burns T, 2013. Operationalising the capability approach for outcome measurement in mental health research. Soc Sci Med. 98, 187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinnett AA, & Paltiel AD, 1996. Mathematical programming for the efficient allocation of health care resources. J Health Econ. 15(5), 641–53. doi:S0167-6296(96)00493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strømme EM, Bærøe K, & Norheim OF, 2014. Disease control priorities for neglected tropical diseases: Lessons from priority ranking based on the quality of evidence, cost effectiveness, severity of disease, catastrophic health expenditures, and loss of productivity. Developing World Bioethics. 14(3), 132–41. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussex J, Towse A, & Devlin N, 2013. Operationalizing value-based pricing of medicines: A taxonomy of approaches. PharmacoEconomics, 31(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40273-012-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, & Harden A, 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verguet S, Kim JJ, & Jamison DT, 2016. Extended cost-effectiveness analysis for health policy assessment: A tutorial. PharmacoEconomics. 34(9), 913–23. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0414-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wailoo A, Tsuchiya A, & McCabe C, 2009. Weighting must wait: Incorporating equity concerns into cost-effectiveness analysis may take longer than expected. PharmacoEconomics, 27(12), 983–9. doi: 10.2165/11314100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead SJ, & Ali S, 2010. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: The QALY and utilities. Br Med Bull. 96, 5–21. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitty JA, Lancsar E, Rixon K, Golenko X, & Ratcliffe J, 2014. A systematic review of stated preference studies reporting public preferences for healthcare priority setting. Patient. 7(4), 365–86. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikler D, Brock DW, Marchand S, & Torres TT, 2007. Quantitative methods for priority-setting in health: Ethical issues In Ashcroft RE, Dawson A, Draper H and McMillan JR. (Eds.), Principles of Health Care Ethics (2nd ed.) (pp. 563–568). John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. doi: 10.1002/9780470510544.ch77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, & de-Shalit A, 2007. Disadvantage. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Zwerling A, Dowdy D, Von Delft A, Taylor H, Merritt MW, 2017. Incorporating social justice and stigma in cost-effectiveness analysis: drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 21(11), 69–74. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.