Abstract

Purpose: The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics supports meal replacement (MR) programs as an effective diet-related weight management strategy. While MR programs have been successful promoting initial weight loss, weight regain has been as high as 50% 1 year following MR program participation. The purpose of this article is to identify barriers to and facilitators of weight loss (WL) and weight loss maintenance (WM) among individuals participating in a MR program. Methods: Sixty-one MR program clients participated in focus groups (WL = 29, WM = 32). Barriers and facilitators were discussed until saturation of themes was reached. Focus group transcriptions were coded into themes to identify the barriers to and facilitators of weight management that emerged within each phase. Queries were run to assess frequencies of references to each theme. Results: The primary barriers within the WL phase included program products, physical activity, and social settings. WM phase participants referenced nutrition, lack of health coach knowledge, and physical activity as barriers. Personal benfits, ability to adhere to the program, and family support emerged as leading facilitators for WL phase participants. Personal benefits, health coach support, and physical activity emerged as facilitators by WM phase participants. Conclusions: Health coaches have the unique opportunity to use perceived facilitators to improve participant success, and help participants address their personal barriers in order to progress through successful, long-term weight management. Current health coaching models used in MRP should aim to identify participants’ specific barriers and develop steps to overcome them.

Keywords: focus groups, lifestyle change, obesity, qualitative methods, physical activity

Introduction

Obesity is a significant public health challenge in the United States. Individuals with obesity are at an increased risk for developing diabetes, heart disease, osteoarthritis, certain cancers, and psychosocial disorders.1 Health care provider–initiated discussions about weight have been shown to help raise awareness of overweight and obesity among patients and encourage weight loss.2-4 However, many primary care providers feel limited in their ability to provide the lifestyle modification counseling needed.5 The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends adults with obesity participate in comprehensive lifestyle interventions to support clinically significant weight loss and reduce the incidence of associated comorbidities.6 There are many commercial weight loss programs that pair a comprehensive lifestyle approach with meal replacement (MR) products.7-9 Use of commercial MR products and weight loss programs are commonly reported weight loss practices in adults that report wanting to lose weight,10 generating a revenue of more than 6 billion dollars in the United States in 2018.11,12 The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics supports the use of MR products as an effective diet-related weight loss strategy, when combined with healthful lifestyle behaviors emphasizing sustainable and enjoyable eating practices and daily physical activity.13

Multiple studies suggest individuals who utilize weight loss programs with MR products experience more weight loss compared with individuals placed on a reduced-calorie diet utilizing grocery store foods.14-20 Because support has also been identified as an essential component of effective weight loss programs,21 health coaching has been added to some MR programs to provide support, accountability, and nutrition and physical activity education. While the addition of a health coach has improved weight management efforts following weight loss,22,23 weight regain is still common. After losing weight via MR products, participants who met for 20 sessions with a health coach over the course of a year regained 14% of the weight they had lost, while individuals who did not participate in postprogram weight maintenance support regained 56% of the weight they had initially lost.24

Barriers to weight management (both weight loss and weight loss maintenance) have previously been identified in the literature,25-43 but not specific to participants of MR programs. Because of the popularity of MR programs, there is a need to understand the barriers and facilitators of weight management specific to MR program participants. Furthermore, because many MR programs are composed of phases with different weight-related goals, there is a need to understand barriers and facilitators specific to each program phase. Through a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators perceived by individuals currently participating in an MR program, strategies for optimizing weight management of program participants can be identified to enhance long-term participant success.

Materials and Methods

Program Background

Study participants were enrolled in a proprietary MR program that included health coaching. The MR program had three phases including a weight loss phase (predominately MR products), a transition phase (transitioning from MR products to grocery store foods), and a weight loss maintenance phase (predominately grocery store foods). Participants moved through the program phases at their own pace based on individualized weight goals. Health coaches met with program participants regularly to guide participants through the program logistics, provide education, and assist participants in reaching their weight loss goals. The program health coaches were trained in-house to provide education around program guidelines, nutrition, physical activity, and lifestyle behaviors. Health coaching sessions included direct education on topics such as: nutrition label reading, food groups, meal planning, exercise basics, changing eating behaviors, and personal responsibility.

Recruitment

The MR program administrators provided de-identified data of individuals currently enrolled in the MR program to the research team, indicating current program phase, phase start date, weight history, birthdate, and sex. The de-identified data were used to determine individuals currently participating in the MR program that met eligibility requirements for the research study. Individuals had to be ≥18 years old and had to have participated in the weight loss (WL) or weight loss maintenance (WM) phase for a minimum of eight weeks, and no more than 12 weeks, to allow time for the adoption of weight management behaviors specific to each phase. A total of 1089 MR program participants who met study qualifications were recruited to participate in the present study via email invitation sent by program administrators. Sixty-one individuals volunteered to participate in focus groups prior to reaching a point of theme and concept saturation, at which point, study recruitment ceased. Twenty-nine study participants were currently enrolled in the WL phase and 32 in the WM phase of the program. Individuals enrolled in the transition phase were not considered eligible to participate in the present study as this phase is brief and simply provides education to help the client transition from primary dependence on MR products to grocery store foods. Research protocols and procedures were approved by the South Dakota State University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants received a $30 gift card for participation.

Data Collection

Focus groups were conducted to promote discussion among participants and encourage sharing of ideas, perceptions, and experiences related to program participation and weight management. All study participants attended one focus group session. Focus groups for the WL and WM phases were held separately with a facilitator and note taker present at each focus group. Ultimately, six focus groups were held for the WL phase and seven were held for the WM phase. As part of the focus group, participants were asked to respond to eight open-ended questions querying strengths and weaknesses of their present program phase, perception of health coaches, nutrition and physical activity education, factors associated with success or lack thereof and final thoughts. Questions were designed to elicit responses regarding internal and external barriers to and facilitators of weight management. Focus groups lasted an average duration of 48 minutes. Subject demographics were collected via electronic survey. Participants were provided the survey link and instructions for completion at focus group sessions and were asked to complete within one week of focus group participation.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were transcribed and imported into NVivo 10 software to be coded and analyzed using content analysis theory by two researchers. Once the initial coding of questions was complete, the researchers met to come to a consensus over discrepancies, then further coded into barriers and facilitators. Two additional researchers reviewed all coding. The kappa coefficient between coders was determined to test for consistency. When kappas across all nodes were 0.4 or higher (average 0.66), as recommended by McHugh,44 queries were run to identify common themes in the data and to examine the frequency distribution of themed responses across the WL and the WM phases. The themes that emerged as barriers to and facilitators of weight management are reported as the theme proportion [(frequency of references within each theme)/(total references) × 100] to allow for comparison between phases despite slight differences in sample size.

Results

Participants were predominately white (23 WL, 22 WM) and female (19 WL, 24 WM). Age range was 34 to 70 years (mean 51 years) in the WL phase, and 31 to 82 years (mean 56 years) in the WM phase. All participants in the WL phase were employed whereas 20 participants (62.5%) in the WM phase were employed.

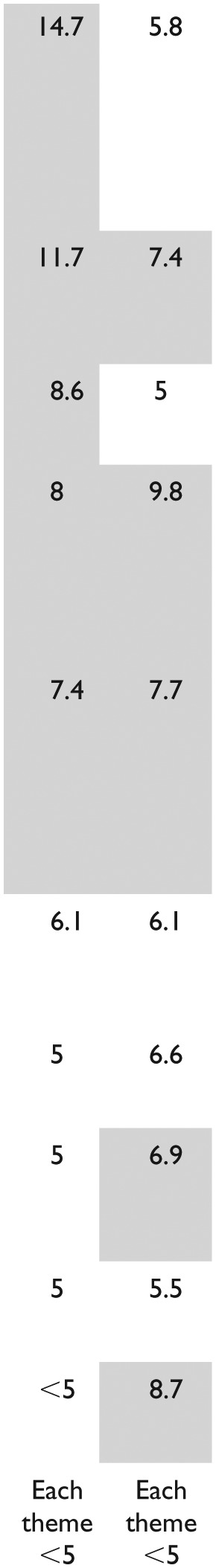

Barriers

Twenty-two themes were identified as barriers for MR program participants in both the WL and WM phases (Table 1). Three of the top five themes that emerged as barriers were consistent between the WL and WM phases: physical activity, health coach knowledge, and nutrition. Regarding the “physical activity” theme, participants in both program phases discussed feeling frustrated that while some health coaches would discuss the recommended physical activity guidelines, they would not provide follow-up education on how to meet them. Overall, participants lacked confidence in engaging in physical activity and did not feel confident knowing what types of activity to do or how to overcome personal barriers to regular physical activity participation. Regarding the “health coach knowledge” theme, participants in both program phases discussed not being able to build rapport with their health coach due to their lack of confidence in their health coach’s knowledge. Moreover, participants felt coaches lacked life experience knowledge and could not relate to what they were going through given that many coaches were of younger age, had no children, and may have never struggled with their weight. Participants in both program phases discussed “nutrition” as a barrier. Participants in the WL phase commonly referenced their difficulty in adhering to the nutrition guidelines of the program. They discussed the difficulty they encountered to avoid temptations, especially when eating with friends and family who were not participating in the program, and when preparing food for their children. Participants of the WM phase struggled with making nutritious food choices following the transition from the MR phase of the program to more grocery store-based food, noting the preparation time required to have healthy foods available at all times to reduce the likelihood they would make unhealthy, impulse food choices.

Table 1.

Barriers.a

| Theme | Description | Representative Participant Quotation(s) | Theme Proportion (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL | WM | |||

| Program Products | Meal replacement bars, shakes, program Bluetooth scale | “Not enough of a variety for me.” I got ‘shaked’ out [referring to the daily shake as a MR] and it made it challenging to adhere to the program.” “We have to figure out how to live without meal replacements (referring to change of grocery store food in the WM phase). Now that we’ve lost the weight and kept it off, how are we going to adjust back to life without meal replacements?” |

|

|

| Physical Activity | Absence of education or emphasis on physical activity from health coach | “One of the things I really wanted help with was advice about exercise and I haven’t gotten anything.” | ||

| Social Settings | The environment in which clients interact with family and/or friends | “Sometimes you almost feel like it causes you to limit your social activity because you have to make a choice.” | ||

| Nutrition | Selection and consumption of healthy foods suggested by the weight management program | “I cook for my kids in the household and so when I’m cooking them things (that are different from what I am supposed to be eating), it’s really hard to stay on track.” “After switching [from MR] to grocery store foods I had to invest more time into selecting and preparing healthy meals and snacks in order to stick to the guidelines of the program.” |

||

| Health Coach Knowledge | The perceived knowledge the health coach had about the weight management program | “I have wondered what their training when they enter their employment is. I wasn’t sure if some coaches knew a lot about the nutrition component to answer my questions.” “My health coach was young and skinny. She didn’t have children and I didn’t feel that she really understood things I would describe as challenges and thus, the solutions (she provided) didn’t always seem feasible.” |

||

| Adherence | The commitment and ability to follow the weight management program guidelines | “When you are in the [weight loss] phase it’s four shakes, your protein, vegetables, and your bar and you don’t have to think about it. Then you switch to the [weight maintenance] phase, and there’s a lot of decision making throughout the day.” | ||

| Consistency of Information Provided | The variation in the advice health coaches provided | “[Coaches] didn’t agree on what I was supposed to do. One set me up with a plan, then the next week I’d go in and another would ask, ‘why are you doing that?’ I was getting so confused. It wasn’t very helpful.” | ||

| Consistency of Health Coaching Assignment | Whether the client continued to see the same coach each visit, or saw multiple coaches | “I’ve been with a different coach every time and I actually am struggling with it. Some have their own strengths and philosophies and I find it confusing.” | ||

| Health Coach Education | The educational background of the health coach | “I have wondered what their training is. I wasn’t sure if some coaches knew a lot about nutrition to answer my questions.” | ||

| Health Coach Support | The lack of support provided by the health coach | “I’d go in, and [the Health Coach] would ask me how everything was going, and I’d be right out the door again. They were very, very quick sessions.” | ||

| Program Tools, Home Settings, Work Settings, Family, Friends, Coworkers, Health Coach Personality, Internal Motivation, Accountability, External Motivation, Time, and Stress | ||||

Gray-shaded cells denote the top five themes for each program phase.

Other themes that emerged as part of the top five barriers for WL phase participants included “program products” and “social settings.” Program products were often referenced as a barrier as participants questioned moving forward with healthful eating after relying so heavily on program products such as MR bars, shakes, and pre-packaged meals. They also noted growing tired of consuming MR products, despite a variety of options. For social settings, participants noted the difficulty of choosing meals to eat when outside of the home and when faced with social gatherings centered on food.

Other themes that emerged as part of the top five barriers by WM phase participants included “health coach support” and “consistency of health coach assignments.” Many participants often met with different health coaches and found they discussed the same things at each visit rather than building on previous visits. Participants voiced that when they found a health coach that they felt comfortable with, they liked continuing to meet with that coach rather than seeing a variety of coaches, as the coaches were then more aware of their own personal journey and could personalize their care.

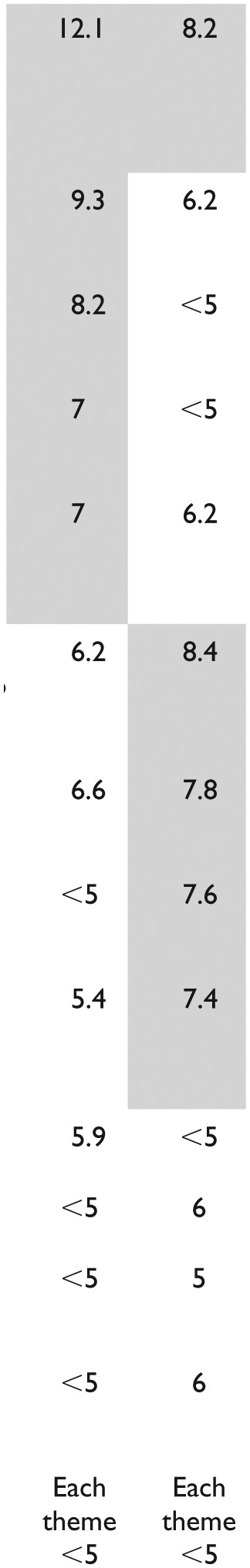

Facilitators

Twenty themes were identified as facilitators for MR program participants in both the WL and WM phases (Table 2). Of the top five themes that emerged as facilitators, only one was present in participants from both phases: personal benefits. Participants in both program phases discussed how “personal benefits” drove them to move forward in their weight management journey, noting improved health, mobility, confidence, and quality of life. Other themes that emerged as part of the top five facilitators for WL phase participants were adherence, family, program products, and program tools. Participants felt that adherence to the program helped their success and the longer they followed the program and had success the more if fostered their drive to continue. Participants also said the program plan was convenient and easy to follow and that “family” was supportive by going out to eat at places that offered healthy choices. Participants often noted how “program tools” were helpful. “Program tools” consisted of educational handouts provided that participants thought helped support their weight loss efforts.

Table 2.

Facilitators.a

| Theme | Description | Representative Participant Quotation | Theme Proportion (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL | WM | |||

| Personal Benefits | Personal benefits that provide motivation, such as improvements in health outcomes, energy, body image, self-confidence, quality of life, and pride. | “I felt better as I lost weight. I liked the way I looked and felt about myself and that kept me wanting to lose more (weight) and reach my goals. |

|

|

| Adherence | The commitment and ability to follow the weight management program guidelines | “[The Weight Management Program] is easy to follow.” | ||

| Family | Influence of parents, spouses, and other family members | “My family has been very encouraging. If we go out to eat, it’s okay if I just have a cup of coffee and that’s really helping me.” | ||

| Program Products | Meal replacement bars, shakes, program Bluetooth scale | “The program scale shows a graph of your weight trends and it is so fun to see that line going down.” | ||

| Program Tools | Supporting materials provided by the health coach that revolved around healthy eating or exercising | “Every time I went in, they gave me reading material. They recommended a lot of articles about nutrition and exercise.” | ||

| Health Coach Support | The support provided by the health coach | “The major thing for me was seeing a coach after I got to my goal weight. Most programs, you get to where you want to be and you’re done….I like that the supports not over.” | ||

| Physical Activity | Regular physical activity regulated weight loss and weight loss maintenance. | “Physical activity is going to help me maintain my weight and keep moving.” | ||

| Nutrition | Selection and consumption of healthy foods suggested by the weight management program | “I didn’t realize how narrow my food choices were….This program has really helped open me to a lot greater variety of nutritional choices.” | ||

| Health Coach Knowledge | The perceived knowledge the health coach had about the weight management program | “I was very impressed with [Health Coach] knowledge. I was a health teacher so I knew some of the questions to ask and I was very impressed with the answers I got.” | ||

| Consistency of Information Provided | The variation in the advice health coaches provided | “I liked being told different things because it made me experiment to find out what worked for me.” | ||

| Friends | Influence of friends | “My friends are understanding when I pass up pizza and don’t harass me to have a cheat day.” | ||

| Social Settings | The environment in which clients interact with others | “This is an easy diet to travel with. I can go anywhere and order meat and a side of vegetables.” | ||

| External Motivation | Motivation that is driven from an external force or for the sake of an external outcome | “My family is just so proud of me.” | ||

| Health Coach Personality, Health Coach Education, Consistency of Health Coach Assignment, Coworkers, Home Settings, Work Settings, and Accountability | ||||

Gray-shaded cells denote the top five themes for each program phase.

Other themes that emerged as part of the top five facilitators for WM phase participants were physical activity, nutrition, health coach knowledge, and health coach support. Participants discussed how being “physically active” was a big part of being able to maintain their weight and the more activity they did the more driven they were to continue with their weight management journey. With regard to “nutrition” participants voiced how the program improved their nutrition-related habits, making them try new foods and incorporate them into their meals. Participants often referenced how the “health coach knowledge” helped them to shape their new nutrition and physical activity behaviors and how the “health coach support” they received helped them to stay motivated and aided in their success.

Discussion

Previous studies indicate that self-management behaviors including being mindful of food choices, committing to physical activity, regular weight monitoring, continued use of MR products, and planning ahead are facilitators of weight management.22-24,33,36,45 Barriers to weight management that have been identified include having children, body dissatisfaction, poor access to parks, trails, or gym equipment, time, poor self-monitoring, social cues, and internal cues.24,33,36,45 The present study extends the current literature by identifying facilitators and barriers to weight management within individuals actively participating in a MR program that includes health coaching.

Physical activity–related barriers to weight management, such as environmental barriers, lack of time, and lack of energy have previously been identified as barriers to physical activity participation33,45 and similar concepts were discussed by participants in the current study. Participants also discussed the difficulty of adhering to a diet while in social settings, which is consistent with previously identified situational barriers such as eating out, attending parties, and traveling as barriers to diet adherence.33 Additional barriers to weight management identified in the present study were unique in that they related to experiences with MR program logistics and heath coaches. Participants lacked confidence in their health coach’s knowledge and support, and they identified inconsistent coaching assignments during in-person visits as a barrier. In contrast, support from health coaches was also seen as a facilitator. Together with previous literature, these data suggest that health coaching can be beneficial to weight management, however, logistical factors may determine if health coaching is perceived as a barrier or facilitator to participant success and should be considered by program management, including health coach level of training, comfort with all topic areas, degree of supportiveness, and format of health coaching (cycling coaches vs. matching participants with a set coach). Future research should examine how health coaches are being used in large-scale weight management programs, and the impact of health coaching logistics on program perception and outcome variables.

Previous studies have noted self-management behaviors as facilitators22-24,33,36,45 much like adherence to program guidelines and personal benefits were identified in the current study. However, the present study adds unique facilitators related to the health coaching component of this particular MR program, including health coach support and knowledge. Participants also noted family, physical activity, and work settings as facilitators of weight management, indicating that support and accountability that facilitates weight management can come from a variety of places.

Overall, 2 key findings emerged beyond the specific facilitators and barriers to weight management identified within this study. First, there was an overlap of barriers and facilitators between phases, demonstrating how barriers and facilitators may not be specific to WL or WM phases. We speculate that while one may overcome a barrier during the WL phase of a program, the same barrier may arise again in subsequent phases due to differences in phase protocols, thus requiring a new approach. The nature of MR programs is that participants initially follow a strict diet that predominately includes MR products during the WL phase and then transition to grocery store foods in the WM phase, and the techniques that may be successful in helping clients overcome barriers in one phase may not be applicable within the next. These findings can inform the health coaching practice in MR programs to identify barriers and help participants overcome them during each phase of program participation.

The second key finding that emerged from the present study was that common themes were identified as both a barrier and facilitator among participants within a given phase. This highlights the need for personalizing weight management programs at the individual level to capitalize on perceived facilitators and identify and overcome perceived barriers. While health coaching can be one way to personalize a weight management program to an individual’s needs, blending health coaching with a standardized, protocol-driven program may result in more health education than coaching, making it hard to provide the individualization needed for success. The results of this study highlight areas that coaching logistics could be modified to allow for providing more personalized coaching on health behaviors in addition to health education.

A limitation of the present study is that although focus groups were held until saturation of themes was reached, individuals who chose to participate may not be representative of all program participants in the respective phases, thus, care must be taken when interpreting findings. A strength of the present study is that it provides insight into these issues during the weight management process itself. Although previous research has examined barriers to and facilitators of weight management, it has typically been conducted after an individual has stopped participation in a weight loss program. Future research should extend this work to explore the relationship between perceived barriers and facilitators of weight loss and weight maintenance on changes in weight in MR program participants.

Conclusions

Health coaches have the unique opportunity to use an individual’s perceived facilitators to improve success and help overcome personal barriers to weight management. To enhance the success of MR programs, current health coaching models should aim to identify participants’ specific barriers and work to develop steps to overcome them, engaging participants in individualized health coaching rather than health education. Furthermore, facilitators and barriers should be reassessed at different stages of the weight management process, and coaching should be adjusted in response, as facilitators and barriers may change within different phases of MR programs.

Author Biographies

Hope D. Kleine, MS, ACSM-EP, completed this research as part of the requirements for a master’s degree in Nutrition and Exercise Science from South Dakota State University. She is a Health Education Specialist for South Dakota State University Extension.

Lacey A. McCormack, PhD, MPH, RD, LN, ACSM-EP, is an associate professor in the Department of Health and Nutritional Sciences at South Dakota State University.

Alyson Drooger, MS, completed this research as part of the requirements for a master’s degree in Nutrition and Exercise Science from South Dakota State University.

Jessica R. Meendering, PhD, ACSM-EP, is an associate professor in the Department of Health and Nutritional Sciences at South Dakota State University.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Sanford Health – South Dakota State University collaborative research program and by the South Dakota Board of Regents R&D Innovation program.

ORCID iD: Jessica Meendering  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2967-2818

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2967-2818

References

- 1. Khaodhiar L, Mccowen KC, Blackburn GL. Obesity and its comorbid conditions. Clin Cornerstone. 1999;2:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jackson SE, Wardle J, Johnson F, Finer N, Beeken RJ. The impact of a health professional recommendation on weight loss attempts in overweight and obese British adults: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003693. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose SA, Poynter PS, Anderson JW, Noar SM, Conigliaro J. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change : a literature review and meta-analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:118-128. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Post RE, Mainous AG, 3rd, Gregorie SH, Knoll ME, Diaz VA, Saxena SK. The influence of physician acknowledgment of patients’ weight status on patient perceptions of overweight and obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frank A. Futility and avoidance. Medical professionals in the treatment of obesity. JAMA. 1993;269:2132-2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03500160102041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US Preventative Services Task Force Recomendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1163-1171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wee CC. The role of commercial weight-loss programs. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:522-523. doi: 10.7326/m15-0429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tsai AG, Wadden T. Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:56-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gudzune KA, Doshi RS, Mehta AK, et al. Efficacy of commercial weight loss programs: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:501-512. doi: 10.7326/M14-2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levy AS, Heaton AW. Weight control practices of US adults trying to lose weight. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 pt 2):661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. IBISWorld. Meal replacement product manufacturing industry in the US: industry market research report. https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-trends/specialized-market-research-reports/consumer-goods-services/food-production/meal-replacement-product-manufacturing.html. Published September 2018. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- 12. IBISWorld. Weight loss services industry in the US: industry market research report. https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-trends/market-research-reports/other-services-except-public-administration/personal-laundry/weight-loss-services.html. Published November 2018. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- 13. Seagle HM, Strain GW, Makris A, Reeves RS; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: weight management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:330-346. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Food provision as a strategy to promote weight loss. Obes Res. 2001;9(suppl 4):271S-275S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rothacker DQ, Staniszewski BA, Ellis PK. Liquid meal replacement vs traditional food: a potential model for women who cannot maintain eating habit change. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:345-347. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(01)00089-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:537-549. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ditschuneit HH, Flechtner-Mors M, Johnson TD, Adler G. Metabolic and weight-loss effects of a long-term dietary intervention in obese patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:198-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ard JD, Lewis KH, Rothberg A, et al. Effectiveness of a Total Meal Replacement Program (OPTIFAST Program) on weight loss: results from the OPTIWIN Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27:22-29. doi: 10.1002/oby.22303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Astbury NM, Piernas C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lapworth S, Aveyard P, Jebb SA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of meal replacements for weight loss. Obes Rev. 2019;20:569-587. doi: 10.1111/obr.12816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arterburn LM, Coleman CD, Kiel J, et al. Randomized controlled trial assessing two commercial weight loss programs in adults with overweight or obesity. Obes Sci Pract. 2018;5:3-14. doi: 10.1002/osp4.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S102-S138. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olsen JM, Nesbitt BJ. Health coaching to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors: an integrative review. Am J Heal Promot. 2010;25:e1-e12. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090313-LIT-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obes (Silver Spring). 2009;17:713-722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ames GE, Patel RH, McMullen JS, et al. Improving maintenance of lost weight following a commercial liquid meal replacement program: a preliminary study. Eat Behav. 2014;15:95-98. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barnes AS, Goodrick GK, Pavlik V, Markesino J, Laws DY, Taylor WC. Weight loss maintenance in African-American women: focus group results and questionnaire development. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:915-922. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Befort CA, Thomas JL, Daley CM, Rhode PC, Ahluwalia JS. Perceptions and beliefs about body size, weight, and weight loss among obese African American women: a qualitative inquiry. Heal Educ Behav. 2008;35:410-426. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reyes NR, Oliver TL, Klotz AA, et al. Similarities and differences between weight loss maintainers and regainers: a qualitative analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:499-505. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sciamanna CN, Kiernan M, Rolls BJ, et al. Practices associated with weight loss versus weight-loss maintenance: results of a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:159-166. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Kausman R, Komesaroff PA. “They all work . . . when you stick to them”: a qualitative investigation of dieting, weight loss, and physical exercise, in obese individuals. Nutr J. 2008;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:222S-225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharifi N. Perceived barriers to weight loss programs for overweight or obese women. Heal Promot Perspect. 2013;3:11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ali HI, Baynouna LM, Bernsen RM. Barriers and facilitators of weight management: perspectives of Arab women at risk for type 2 diabetes. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:219-228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hammarström A, Wiklund AF, Lindahl B, Larsson C, Ahlgren C. Experiences of barriers and facilitators to weight-loss in a diet intervention—a qualitative study of women in Northern Sweden. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:955-962. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ely AC, Befort C, Banitt A, Gibson C, Sullivan D. A qualitative assessment of weight control among rural Kansas women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:207-211. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.04.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Green AR, Larkin M, Sullivan V. Oh stuff it! the experience and explanation of diet failure: an exploration using interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:997-1008. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Herriot AM, Thomas DE, Hart KH, Warren J, Truby H. A qualitative investigation of individuals’ experiences and expectations before and after completing a trial of commercial weight-loss programmes. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:72-80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hindle L, Carpenter C. An exploration of the experiences and perceptions of people who have maintained weight loss. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:342-350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:239-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ogden J. The correlates of long-term weight loss: a group comparison study of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1018-1025. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22:276-282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Venditti EM, Wylie-Rosett J, Delahanty LM, et al. Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]