Abstract

Prenatal testing in recent years has been moving toward non-invasive methods to determine the fetal risk for genetic disorders without incurring the risk of miscarriage. Rapid progress of modern high-throughput molecular technologies along with the discovery of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma led to novel screening methods for fetal chromosomal aneuploidies. Such tests are referred to as non-invasive prenatal tests (NIPTs), non-invasive prenatal screening, or prenatal cell-free DNA screening. Owing to many advantages, the adoption of NIPT in routine clinical practice was very rapid and global. As an example, NIPT has recently become a standard screening procedure for all pregnant women in the Netherlands. On the other hand, invasive sampling procedures remain important, especially for their diagnostic value in the confirmation of NIPT-positive findings and the detection of Mendelian disorders. In this review, we focus on current trends in the field of NIPT and discuss their benefits, drawbacks, and consequences in regard to routine diagnostics.

Keywords: NIPT, fetal aneuploidies, amniocentesis, screening, cffDNA, non-invasive

Evolution of prenatal testing and diagnosis

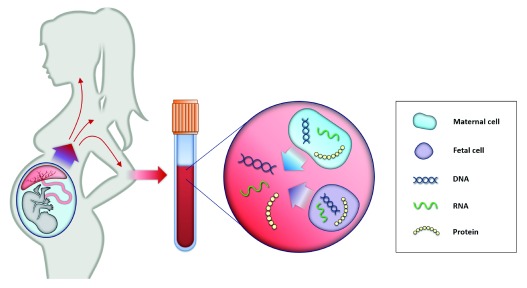

In current clinical practice, various options of prenatal testing are available for pregnant women in developed countries. However, this convenience has been available only in the last few years. Prenatal testing has passed a long evolution from traditional invasive methods (for example, amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling [CVS]) 1. Early reports of transabdominal amniocentesis came from 1877 but this procedure became more prevalent in the 1970s for genetic diagnosis in high-risk pregnancies 2, 3. CVS was first described by Mohr in 1968 4. Since the introduction of ultrasound guidance in 1980, the safety of CVS has increased 5, and this method has become widely accepted in routine prenatal diagnosis. A tremendous contribution to prenatal testing was the implementation of non-invasive procedures based on blood sampling ( Figure 1). In 1959, Zipursky et al. found that intact fetal cells are present in maternal plasma 6; in 1969, Walknowska et al. showed that this approach may have implications for prenatal diagnosis 7. However, the main limitation of the method is a low concentration of intact fetal cells in maternal circulation. The detection of cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) in maternal plasma, by Lo et al. in 1997, launched a new era of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) which has been integrated in clinical practice and represents the standard in developed countries today 8. It was shown that a major fraction of cffDNA is released into the maternal circulation during apoptosis of trophoblasts in placenta, which means that, unlike DNA isolated from circulating fetal cells, cffDNA is actually of placental origin 9. According to previous calculations, the cffDNA concentration is almost 25 times higher than the concentration of fetal DNA extracted from intact nucleated blood cells in a similar volume of whole maternal blood. Moreover, the approach using cffDNA provides easier, less labor-intensive, and less time-consuming ways to work with fetal DNA 10. Current NIPT procedures cannot be performed without modern molecular technologies (for example, next-generation sequencing (NGS)). This is why the cffDNA-based NIPT became commercially available and widespread since 2011 11, 12. Nowadays, NIPT is being implemented in public prenatal care in several countries (for example, the Netherlands) 13.

Figure 1. Principle of non-invasive prenatal testing.

Maternal blood consists of maternal and placental cells, which release their DNA content directly into maternal circulation. Therefore, cell-free fetal elements (for example, DNA, RNA, and proteins) are present in the blood of pregnant woman and can be used as biomarkers for prenatal testing and diagnosis 21, 22.

Cell-free fetal DNA–based approach

Cell-free fragments derived from fetal DNA are shorter than those of maternal cell-free DNA (cfDNA), and the size distribution is typically lower than 150 base pairs 14, 15. According to Ashoor et al., at 11 to 13 weeks of gestation, the concentration of the fetal DNA fraction ranges from 7.8 to 13.0% depending on gestational age; thus, for analysis of aneuploidy, it is possible to obtain a useful result after 10 weeks of gestation 16. In the vast majority of cases, cffDNA is no longer detectable 24 hours after birth and this is due to rapid clearance 17, 18. Another factor affecting cffDNA fraction is maternal body mass index. It was shown that the median fetal fraction decreased with maternal weight, from 11.7% at 60 kg to 3.9% at 160 kg 16. The relative decrease in fetal fraction could be caused by an increased level of maternal cfDNA originating from active necrosis and apoptosis of adipose tissue in obese pregnant women. The study by Haghiac et al. showed that maternal cfDNA levels are elevated in obese compared with lean pregnant women but that cffDNA concentrations remain unchanged 19. Because the ratio of fetal fraction decreases with increasing maternal weight, maternal obesity has a negative impact on the diagnostic capability of genetic screening; thus, NIPT is less likely to provide an informative result in obese patients 20. Moreover, it was shown that levels of placental proteins—such as free beta human chorionic gonadotropin, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), and placental growth factor (PlGF)—are positively correlated with fetal fraction and placental mass. Furthermore, low PAPP-A and PlGF levels correlate with a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcome, so low fetal fraction may be a useful additional parameter in detecting a high-risk group of pregnancies 23.

With increasing throughput and lowering cost, NGS technology became available and, together with cffDNA analysis, opened a new horizon for detection of trisomies and sub-chromosomal aberrations in a non-invasive manner. Current approaches are based on low-coverage massively parallel whole-genome sequencing analysis of plasma DNA from pregnant women. Total cfDNA is sequenced, sequence reads are aligned to reference human genome, and aligned reads are counted 24. Thus, a proportional representation of each chromosome can be calculated, and chromosome ploidy status can be determined 11.

Studies also reported the use of whole-genome sequencing of plasma DNA for the detection of sub-chromosomal copy number variants (for example, microdeletions and microduplications). However, these approaches are limited by the requirement for an exceptionally high number of sequenced reads and complicated interpretation because of the identification of variants of unknown clinical significance 25. Petersen et al. estimated lower positive predictive values (0–21%) and higher false-positive rates (79–100%) for the selected microdeletion syndromes (cri du chat/5p- syndrome, Prader–Willi/Angelman syndromes, 22q11del/DiGeorge syndrome, and 1p36 deletion syndrome) compared with common aneuploidies 26. Given the low prevalence leading to low positive predictive values, screening for microdeletions should not be used in the general population until clinical validation studies indicate value for the low-risk patients 27. Although expanded NIPT screening is already integrated into clinical practice, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend routine cffDNA screening for microdeletions at this time 28.

While this technology has been widely applied for aneuploidy, there has been relatively little clinical application for the diagnosis of monogenic disorders 29. Early diagnosis of monogenic disorders has been challenging because of background maternal cfDNA which prevents direct observation of maternally inherited alleles 30. Since these tests are provided on a custom-made basis confined to families at known high risk, there is practically no commercial interest, thus less attention has been given to testing for monogenic disorders 31. However, recently, it was shown that it is possible to non-invasively diagnose prenatal monogenic diseases by combining targeted haplotyping of two parents with targeted sequencing of cfDNA extracted during pregnancy 32.

The fast adoption of cffDNA-based NIPT to clinical practice reflects its many benefits. It is a non-invasive, relatively painless, and safe procedure without the related risk of miscarriage which is associated with amniocentesis and CVS. On the other hand, there are still a number of samples that cannot be interpreted with certainty. A source of such uninformative results is the nature of the statistical testing. If the standard cutoff threshold for the reliable conclusion of healthy samples is a z-score of 2.5, the chance that a healthy sample would achieve a greater z-score is estimated to be around 1.86% 33. Also, biological reasons such as maternal malignancy, fetoplacental mosaicism, or non-identical vanishing twins may contribute to incorrect predictions of the fetal condition 34– 36. However, in spite of these limitations, NIPT has been shown to be a highly accurate method for detection of common fetal chromosomal aneuploidies ( Table 1) 37. According to clinical validation, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) suggests that NIPT can replace conventional screening for Patau, Edwards, and Down syndromes; however, use of the updated ACMG guidelines and statements is recommended to provide quality prenatal care 38. However, it should be noted that NIPT is not a diagnostic test and should be confirmed by invasive testing for the presence of any abnormal results 39. Even the ultrasound scan is still an important component of first-trimester screening, and the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends ultrasound because it allows clinicians to detect additional structural or chromosomal abnormalities (or both) that may not show up in the blood test 40.

Table 1. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA–based non-invasive prenatal test demonstrated by sensitivity and specificity ratio of common tests 37.

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal sex | 0.989 (95% CI 0.980–0.994) | 0.996 (95% CI 0.989–0.998) |

| Rhesus D | 0.993 (95% CI 0.982–0.997) | 0.984 (95% CI 0.964–0.993) |

| Trisomy 21 | 0.994 (95% CI 0.983–0.998) | 0.999 (95% CI 0.999–1.000) |

| Trisomy 18 | 0.977 (95% CI 0.952–0.989) | 0.999 (95% CI 0.998–1.000) |

| Trisomy 13 | 0.906 (95% CI 0.823–0.958) | 1.00 (95% CI 0.999–0.100) |

| Monosomy X | 0.929 (95% CI 0.741–0.984) | 0.999 (95% CI 0.995–0.999) |

CI, confidence interval.

The introduction of NIPT led to a decrease in invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures, but some authors suggest that it also had negative consequences 41. Beaudet suggests that it has caused fewer cases of serious deletion syndromes to be detected, resulting in an increased number of births of infants with severe disabilities 42. Moreover, a reduction in the number of invasive procedures performed reduces practice opportunities for clinicians, leading to significantly higher miscarriage rates 43. Insufficient practice also affects the quality of invasive procedure with more likely side effects, such as infections and fetal loss. In particular, the risks of miscarriage have been estimated to be 0.11% (95% confidence interval [CI] −0.04 to 0.26%) for amniocentesis and 0.22% (95% CI −0.71 to 1.16%) for CVS, according to the systematic review of reported studies in the period of 2000 to 2014 44. Later review of studies in the period of 2000 to 2017 indicated higher risks of miscarriage—0.35% (95% CI 0.07 to 0.63%) and 0.35% (95% CI −0.31 to 1.00%)—for amniocentesis and CVS, respectively 45. If this tendency continues, the training and maintaining of skillful clinicians will be a challenge for future prenatal care.

Fetal cell-based approach

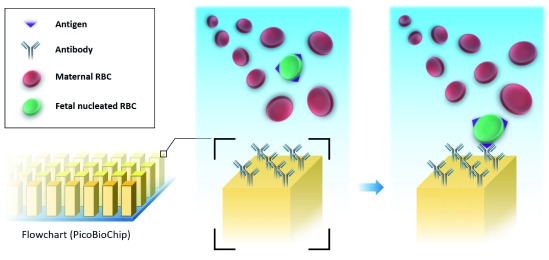

After years of oblivion, several studies recently highlighted the non-invasive analysis of the fetal cells extracted from maternal circulation. It is due to recent advances in single-cell genomics, which opens up opportunities for prenatal screening. Attention in this area has focused on fetal nucleated red blood cells (nRBCs) and trophoblasts. Fetal nRBCs have been the most commonly targeted cell type, however, owing to low-specificity markers and low concentration, trophoblasts have gained more attention 46. The value of cell-based non-invasive prenatal diagnosis (cbNIPD) is that limitations of cffDNA-based NIPT can be overcome. In an effort to prevent the problems with fetoplacental mosaicism, Huang et al. propose a novel silicon-based nanostructured microfluidic platform (Cell Reveal™) for capturing circulating fetal nRBCs and extravillous cytotrophoblasts for cbNIPD 47. This method uses a microfluidic device coated with antibodies which can capture the corresponding antigens on the targeted cells ( Figure 2). The nRBCs isolated through this platform were confirmed to be of fetal, not placental, origin by short tandem repeat analysis, fluorescence in situ hybridization, array comparative genomic hybridization, and NGS 47. Although the cell-based approach has limitations, it has been shown that individual fetal cells can be isolated from maternal circulation and that their pure fetal DNA can be used for the detection of copy number abnormalities of at least 1 Mb by low-coverage NGS. Analysis of the fetal genome at a higher resolution would allow increased accuracy and improved positive and negative predictive values compared with cfDNA-based NIPT in the detection of microdeletion syndromes 48.

Figure 2. Scheme of silicon-based nanostructured microfluidic platform (Cell Reveal™).

The microfluidic device is coated with antibodies which can bind the corresponding antigens on the surface of circulating fetal nucleated red blood cells (RBCs). By this method, fetal cells can be separated from other components of whole maternal blood.

Bioinformatics

Frequent use of NGS led to the production of a large amount of genomic data which need to be processed, stored, analyzed, or transferred (or a combination of these). This maintenance is a challenge for bioinformatics and is the reason why the discipline became an essential part of the modern clinical laboratory. For the acquisition of genetic data from NIPT, two primary massively parallel sequencing approaches are currently available: shotgun sequencing for sequencing of the whole genome and targeted sequencing for sequencing of specific genomic regions of interest 34. There are many stages of NGS data analysis where bioinformatics takes place (for example, sequence generation, alignment, and detection of genomic variation) 49. Downstream analysis of cfDNA requires bioinformatic algorithms, many of which are based on detection and quantification of imbalances in allelic count, regional genomic representation, or size distribution (or a combination of these) 50. Moreover, with the in silico bioinformatic approach, it is possible to significantly increase the accuracy and specificity of genetic tests without additional investment for labware 33, 51. This highlights the importance and potential of bioinformatics in current NIPT.

Bioinformatic analysis typically consists of two interconnected steps: detecting structural variation and calculating the proportion of fetal fragments in sequenced genomic mixture, called fetal fraction. Traditionally used methods are based on the abundance of sequenced DNA fragments from the affected chromosome. Standard z-score method 52 may be refined by fine selection of reference chromosomes 53, elimination of long fragments predominantly of maternal origin 51, and correction of laboratory-induced bias 54– 56 that depart from the observed draw of sequenced reads from ideal uniform distribution 57. There is also an emerging field of methods that detect structural aberrations on the basis of diversions of fragment length distributions 15. Additionally, count-based and length-based scores may be combined to achieve better separation between euploid and aneuploid samples 58, 59 and reduction of false-positive and uninformative predictions 33, 60.

Even though count-based methods proved to be highly accurate in routine testing, chromosomal counts alone are not sufficient to determine fetal fraction in cases of pregnancies with female fetuses 61 that have the same karyotype as the mother. General methods therefore exploit other characteristics that differ between maternal and fetal DNA fragments, as an uneven distribution of fetal fragments over genome 62. Specific deviation has also been observed in regions influenced by packaging of DNA in nucleosomes 63. Alternately, fragment length distributions may be used but with lower precision 15. Although general methods do not achieve the precision of count-based methods 64, their combination along with additional patient attributes such as gestational age and body mass index of the mother 65 may further improve their predictions. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based approaches that determine a source of each fragment on the basis of known genotypes of the parents 66, 67 would further revolutionize testing in the coming era of genomic biobanking.

Epigenetics

DNA methylation is a key biological factor that epigenetically regulates the development and function of placenta by gene repression, gene activation, splicing regulation, nucleosome positioning, and the recruitment of transcription factors 68, 69. It is known that the placenta plays a crucial role in the normal development of the fetus during pregnancy. Aberrations in placental DNA methylome led to abnormal expression of affected genes and are associated with developmental defects of the fetus 68. Thus, current NIPT research is interested in the analysis of placental DNA methylation status 70. Whole-genome massively parallel bisulfite sequencing enables clinicians to non-invasively analyze the placental methylome from maternal circulation 71. The determination of methylation status is based on treating the DNA with sodium bisulfite, which results in the conversion of unmethylated cytosine into uracil while methylated cytosine remains unchanged 50.

The approach of plasma DNA tissue mapping based on the fact that different tissues exhibit different DNA methylation patterns can be used to deduce the origin of cfDNA fragments 72. This advantage has great potential to override NIPT limitations caused by maternal malignancy. It means that bisulfite sequencing can be used to differentiate between the origin of fetal-derived cfDNA and tumor-derived cfDNA and thus avoid the false-positive result of NIPT analysis 73. However, this advantage also brings the ethical question of how to handle incidental findings (for example, maternal malignancy) 74.

To perform whole-genome NGS methylomic analysis, it is necessary to use corresponding bioinformatic software. For example, Methy-Pipe is an integrated bioinformatic pipeline for whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data analysis. This tool allows data pre-processing, sequence alignment, and downstream methylation data analysis, including basic statistics and sequencing quality report, calculation of methylation level, identification of differentially methylated regions for paired samples, annotation and visualization of methylation data for data mining, and easy interpretation 75. However, high-resolution whole-genome reconstruction of the placental methylome in a non-invasive manner is still challenging. In an effort to reconstruct the whole fetal/placental methylome, Sun et al. propose a novel algorithm called FEMER (fetal methylome reconstructor) 70. According to the authors, this approach provides a high‐quality view of the placental methylome from the maternal plasma and might accelerate potential clinical applications 70.

An approach that is equivalent to NGS and that could be effective for NIPT of trisomy 21 in pregnant women uses methylated DNA immunoprecipitation combined with quantitative polymerase chain reaction 76. This method is based on the selection of fetal–maternal differentially methylated regions, which are used to enrich and assess the fetal DNA ratio 77. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic efficiency for trisomy 21 showed 100% specificity and 100% sensitivity of this methodology 78. Another validation study showed 99.2% specificity (95% CI 95.62 to 99.98%) and 100% sensitivity (95% CI 92.89 to 100.00%) 79. The main advantage of this method is that, in comparison with the NGS, this approach uses equipment that is available in most genetic diagnostic laboratories and is technically easier and less expensive 77.

Conclusions

The current trend in prenatal testing can be characterized by a massive move from invasive sampling to using a non-invasive or more precisely less-invasive source in the form of blood. Despite some limitations of cffDNA analysis of pregnant women, it seems obvious that NIPT will replace other methods of screening for chromosomal aberrations. It is important to understand that NIPT does not entirely replace invasive sampling procedures. Positive NIPT findings must be confirmed by diagnostic tests based on an invasive sample source, mainly amniocentesis. This is different in the case of monogenic disorders, where a haplotyping-based approach allows diagnosis without the need for further confirmation. Continuing research and development efforts are focused on overriding the NIPT limitations, increasing the accuracy, and extending tested defects to reach a diagnostic grade of results and thus to avoid the requirement for confirmation by invasive diagnostic procedures. Invasive testing remains an important part of prenatal care. Recent studies show that procedure-associated risks in the case of amniocentesis are very low when it is performed by experienced clinicians. Unfortunately, widespread adoption of NIPT leads to a drop in performed invasive procedures and experience is decreasing. We believe that novel findings and technological progress will transform NIPT from screening to a final diagnostic test.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Mark D Kilby, College of Medical & Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; Fetal Medicine Centre, Birmingham Women's & Children's Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK

Neeta L Vora, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Agentúra na Podporu Výskumu a Vývoja (APVV-17-0526). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Bringman JJ: Invasive prenatal genetic testing: A Catholic healthcare provider's perspective. Linacre Q. 2014;81(4):302–13. 10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prochownick L: Nachtrag zu dem Aufsatze: Beiträge zur Lehre vom Fruchtwasser und seiner Entstehung. Arch Gynak. 1877;11(3):561–3. 10.1007/BF01765204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nadler HL, Gerbie AB: Role of amniocentesis in the intrauterine detection of genetic disorders. N Engl J Med. 1970;282(11):596–9. 10.1056/NEJM197003122821105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohr J: Foetal genetic diagnosis: development of techniques for early sampling of foetal cells. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968;73(1):73–7. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1968.tb00480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kazy Z, Sztigár AM, Báchárev VA: [Chorionic biopsy under immediate real-time (ultrasonic) control]. Orv Hetil. 1980;121(45):2765–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zipursky A, Hull A, White FD, et al. : Foetal erythrocytes in the maternal circulation. Lancet. 1959;1(7070):451–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(59)92264-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walknowska J, Conte FA, Grumbach MM: Practical and theoretical implications of fetal-maternal lymphocyte transfer. Lancet. 1969;293(7606):1119–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(69)91642-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. : Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alberry M, Maddocks D, Jones M, et al. : Free fetal DNA in maternal plasma in anembryonic pregnancies: confirmation that the origin is the trophoblast. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27(5):415–8. 10.1002/pd.1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norwitz ER, Levy B: Noninvasive prenatal testing: the future is now. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;6(2):48–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chitty LS, Lo YM: Noninvasive Prenatal Screening for Genetic Diseases Using Massively Parallel Sequencing of Maternal Plasma DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5(9):a023085. 10.1101/cshperspect.a023085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. : DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–20. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Schendel RV, van El CG, Pajkrt E, et al. : Implementing non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy in a national healthcare system: global challenges and national solutions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):670. 10.1186/s12913-017-2618-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 14. Lo YM, Chan KC, Sun H, et al. : Maternal plasma DNA sequencing reveals the genome-wide genetic and mutational profile of the fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(61):61ra91. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu SC, Chan KC, Zheng YW, et al. : Size-based molecular diagnostics using plasma DNA for noninvasive prenatal testing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(23):8583–8. 10.1073/pnas.1406103111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, et al. : Fetal fraction in maternal plasma cell-free DNA at 11-13 weeks' gestation: relation to maternal and fetal characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(1):26–32. 10.1002/uog.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lo YM, Zhang J, Leung TN, et al. : Rapid clearance of fetal DNA from maternal plasma. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(1):218–24. 10.1086/302205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kolialexi A, Tsangaris GT, Antsaklis A, et al. : Rapid clearance of fetal cells from maternal circulation after delivery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1022:113–8. 10.1196/annals.1318.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haghiac M, Vora NL, Basu S, et al. : Increased death of adipose cells, a path to release cell-free DNA into systemic circulation of obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(11):2213–9. 10.1038/oby.2012.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zozzaro-Smith P, Gray LM, Bacak SJ, et al. : Limitations of Aneuploidy and Anomaly Detection in the Obese Patient. J Clin Med. 2014;3(3):795–808. 10.3390/jcm3030795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pös O, Biró O, Szemes T, et al. : Circulating cell-free nucleic acids: characteristics and applications. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26(7):937–45. 10.1038/s41431-018-0132-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Biró O, Rigó J, Jr, Nagy B: Noninvasive prenatal testing for congenital heart disease - cell-free nucleic acid and protein biomarkers in maternal blood. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;1–11. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1508437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 23. Scott FP, Menezes M, Palma-Dias R, et al. : Factors affecting cell-free DNA fetal fraction and the consequences for test accuracy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(14):1865–72. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1330881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 24. Swanson A, Sehnert AJ, Bhatt S: Non-invasive Prenatal Testing: Technologies, Clinical Assays and Implementation Strategies for Women's Healthcare Practitioners. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2013;1(2):113–21. 10.1007/s40142-013-0010-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wapner RJ, Babiarz JE, Levy B, et al. : Expanding the scope of noninvasive prenatal testing: detection of fetal microdeletion syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):332.e1–332.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petersen AK, Cheung SW, Smith JL, et al. : Positive predictive value estimates for cell-free noninvasive prenatal screening from data of a large referral genetic diagnostic laboratory. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(6):691.e1–691.e6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 27. Shaffer BL, Norton ME: Cell-Free DNA Screening for Aneuploidy and Microdeletion Syndromes. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(1):13–26. 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 28. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, Committee on Genetics, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Practice Bulletin No. 163: Screening for Fetal Aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):e123–37. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenkins LA, Deans ZC, Lewis C, et al. : Delivering an accredited non-invasive prenatal diagnosis service for monogenic disorders and recommendations for best practice. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(1):44–51. 10.1002/pd.5197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 30. Guissart C, Debant V, Desgeorges M, et al. : Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of monogenic disorders: an optimized protocol using MEMO qPCR with miniSTR as internal control. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53(2):205–15. 10.1515/cclm-2014-0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chitty LS: Advances in the prenatal diagnosis of monogenic disorders. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(1):3–5. 10.1002/pd.5208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 32. Vermeulen C, Geeven G, de Wit E, et al. : Sensitive Monogenic Noninvasive Prenatal Diagnosis by Targeted Haplotyping. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(3):326–39. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 33. Budis J, Gazdarica J, Radvanszky J, et al. : Combining count- and length-based z-scores leads to improved predictions in non-invasive prenatal testing. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(8):1284–1291. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mackie FL, Allen S, Morris RK, et al. : Cell-free fetal DNA-based noninvasive prenatal testing of aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;19(3):211–8. 10.1111/tog.12388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 35. Benn P, Cuckle H, Pergament E: Non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy: current status and future prospects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(1):15–33. 10.1002/uog.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 36. Bianchi DW, Chudova D, Sehnert AJ, et al. : Noninvasive Prenatal Testing and Incidental Detection of Occult Maternal Malignancies. JAMA. 2015;314(2):162–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.7120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 37. Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, et al. : The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124(1):32–46. 10.1111/1471-0528.14050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 38. Gregg AR, Skotko BG, Benkendorf JL, et al. : Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: A position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18(10):1056–65. 10.1038/gim.2016.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 39. Poon Liona CY: First Trimester Prediction of Preeclampsia by Ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43(Supplement 1):S134 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.08.1426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The Role of Ultrasound in Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing [Internet].[cited 2019 Feb 21]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 41. Warsof SL, Larion S, Abuhamad AZ: Overview of the impact of noninvasive prenatal testing on diagnostic procedures. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(10):972–9. 10.1002/pd.4601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beaudet AL: Using fetal cells for prenatal diagnosis: History and recent progress. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2016;172(2):123–7. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 43. Hui L, Tabor A, Walker SP, et al. : How to safeguard competency and training in invasive prenatal diagnosis: 'the elephant in the room'. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):8–13. 10.1002/uog.15806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akolekar R, Beta J, Picciarelli G, et al. : Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(1):16–26. 10.1002/uog.14636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 45. Beta J, Lesmes-Heredia C, Bedetti C, et al. : Risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Ginecol. 2018;70(2):215–9. 10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04178-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 46. Singh R, Hatt L, Ravn K, et al. : Fetal cells in maternal blood for prenatal diagnosis: a love story rekindled. Biomark Med. 2017;11(9):705–10. 10.2217/bmm-2017-0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 47. Huang CE, Ma GC, Jou HJ, et al. : Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy by circulating fetal nucleated red blood cells and extravillous trophoblasts using silicon-based nanostructured microfluidics. Mol Cytogenet. 2017;10:44. 10.1186/s13039-017-0343-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 48. Vossaert L, Wang Q, Salman R, et al. : Reliable detection of subchromosomal deletions and duplications using cell-based noninvasive prenatal testing. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(13):1069–78. 10.1002/pd.5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 49. Oliver GR, Hart SN, Klee EW: Bioinformatics for clinical next generation sequencing. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):124–35. 10.1373/clinchem.2014.224360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chan LL, Jiang P: Bioinformatics analysis of circulating cell-free DNA sequencing data. Clin Biochem. 2015;48(15):962–75. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Minarik G, Repiska G, Hyblova M, et al. : Utilization of Benchtop Next Generation Sequencing Platforms Ion Torrent PGM and MiSeq in Noninvasive Prenatal Testing for Chromosome 21 Trisomy and Testing of Impact of In Silico and Physical Size Selection on Its Analytical Performance. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144811. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chiu RW, Chan KC, Gao Y, et al. : Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosomal aneuploidy by massively parallel genomic sequencing of DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(51):20458–63. 10.1073/pnas.0810641105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sehnert AJ, Rhees B, Comstock D, et al. : Optimal detection of fetal chromosomal abnormalities by massively parallel DNA sequencing of cell-free fetal DNA from maternal blood. Clin Chem. 2011;57(7):1042–9. 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Benjamini Y, Speed TP: Summarizing and correcting the GC content bias in high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(10):e72. 10.1093/nar/gks001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhao C, Tynan J, Ehrich M, et al. : Detection of Fetal Subchromosomal Abnormalities by Sequencing Circulating Cell-Free DNA from Maternal Plasma. Clin Chem. 2015;61(4):608–16. 10.1373/clinchem.2014.233312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Straver R, Sistermans EA, Holstege H, et al. : WISECONDOR: detection of fetal aberrations from shallow sequencing maternal plasma based on a within-sample comparison scheme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(5):e31. 10.1093/nar/gkt992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Duris F, Gazdarica J, Gazdaricova I, et al. : Mean and variance of ratios of proportions from categories of a multinomial distribution. J Stat Distrib App. 2018;5:2 10.1186/s40488-018-0083-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang L, Zhu Q, Wang H, et al. : Count-based size-correction analysis of maternal plasma DNA for improved noninvasive prenatal detection of fetal trisomies 13, 18, and 21. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(7):3469–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Sun K, Chan KC, Hudecova I, et al. : COFFEE: control-free noninvasive fetal chromosomal examination using maternal plasma DNA. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(4):336–40. 10.1002/pd.5016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Shubina J, Trofimov DY, Barkov IY, et al. : In silico size selection is effective in reducing false positive NIPS cases of monosomy X that are due to maternal mosaic monosomy X. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(13):1305–10. 10.1002/pd.5178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 61. Hudecova I, Sahota D, Heung MM, et al. : Maternal plasma fetal DNA fractions in pregnancies with low and high risks for fetal chromosomal aneuploidies. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88484. 10.1371/journal.pone.0088484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim SK, Hannum G, Geis J, et al. : Determination of fetal DNA fraction from the plasma of pregnant women using sequence read counts. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(8):810–5. 10.1002/pd.4615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Straver R, Oudejans CB, Sistermans EA, et al. : Calculating the fetal fraction for noninvasive prenatal testing based on genome-wide nucleosome profiles. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(7):614–21. 10.1002/pd.4816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van Beek DM, Straver R, Weiss MM, et al. : Comparing methods for fetal fraction determination and quality control of NIPT samples. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(8):769–73. 10.1002/pd.5079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 65. Rava RP, Srinivasan A, Sehnert AJ, et al. : Circulating fetal cell-free DNA fractions differ in autosomal aneuploidies and monosomy X. Clin Chem. 2014;60(1):243–50. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.207951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jiang P, Chan KC, Liao GJ, et al. : FetalQuant: deducing fractional fetal DNA concentration from massively parallel sequencing of DNA in maternal plasma. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(22):2883–90. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jiang P, Peng X, Su X, et al. : FetalQuant SD: accurate quantification of fetal DNA fraction by shallow-depth sequencing of maternal plasma DNA. NPJ Genom Med. 2016;1:16013. 10.1038/npjgenmed.2016.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Koukoura O, Sifakis S, Spandidos DA: DNA methylation in the human placenta and fetal growth (review). Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(4):883–9. 10.3892/mmr.2012.763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tirado-Magallanes R, Rebbani K, Lim R, et al. : Whole genome DNA methylation: beyond genes silencing. Oncotarget. 2017;8(3):5629–37. 10.18632/oncotarget.13562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 70. Sun K, Lun FMF, Leung TY, et al. : Noninvasive reconstruction of placental methylome from maternal plasma DNA: Potential for prenatal testing and monitoring. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(3):196–203. 10.1002/pd.5214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 71. Lun FM, Chiu RW, Sun K, et al. : Noninvasive prenatal methylomic analysis by genomewide bisulfite sequencing of maternal plasma DNA. Clin Chem. 2013;59(11):1583–94. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.212274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sun K, Jiang P, Chan KC, et al. : Plasma DNA tissue mapping by genome-wide methylation sequencing for noninvasive prenatal, cancer, and transplantation assessments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(40):E5503–12. 10.1073/pnas.1508736112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lo YMD: Noninvasive prenatal testing complicated by maternal malignancy: new tools for a complex problem. NPJ Genom Med. 2016;1:15002. 10.1038/npjgenmed.2015.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Allyse M, Minear MA, Berson E, et al. : Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of international implementation and challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:113–26. 10.2147/IJWH.S67124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jiang P, Sun K, Lun FM, et al. : Methy-Pipe: an integrated bioinformatics pipeline for whole genome bisulfite sequencing data analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Christopoulou G, Papageorgiou EA, Patsalis PC, et al. : Comparison of next generation sequencing-based and methylated DNA immunoprecipitation-based approaches for fetal aneuploidy non-invasive prenatal testing. World J Med Genet. 2015;5(2):23–27. 10.5496/wjmg.v5.i2.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kazemi M, Salehi M, Kheirollahi M: MeDIP Real-Time qPCR has the Potential for Noninvasive Prenatal Screening of Fetal Trisomy 21. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2017;6(1):13–21. 10.22088/acadpub.BUMS.6.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 78. Papageorgiou EA, Karagrigoriou A, Tsaliki E, et al. : Fetal-specific DNA methylation ratio permits noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):510–3. 10.1038/nm.2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 79. Tsaliki E, Papageorgiou EA, Spyrou C, et al. : MeDIP real-time qPCR of maternal peripheral blood reliably identifies trisomy 21. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(10):996–1001. 10.1002/pd.3947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]