Abstract

Background:

Pregnancy-induced low back pain (LBP) is a common problem during the pregnancy which usually begins between the 20th and the 28th weeks of gestation, and the exact duration varies.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of LBP including pelvic girdle pain (PGP) and its various aspects such as nature, intensity, character, radiation, circadian pattern, and its correlation with serum calcium levels.

Setting and Design:

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted in a tertiary care hospital in the capital of Delhi.

Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 200 pregnant women completed a questionnaire and also underwent clinical examinations if PGP is suspected. The clinical examination included various pain provocation tests including active straight leg raise test. Venous blood samples were drawn to evaluate the serum calcium levels in pregnant women complaining of back pain. Possible associating factors were studied by nonparametric tests and logistic regression analysis.

Statistical Analysis:

Bivariant correlation of serum calcium levels, total duration of pain, and Visual Analog Scale score was done with various factors such as parity, socioeconomic status, and nature of pain.

Results:

The point prevalence of LBP was found to be 80% with a significantly lower prevalence of PGP, i.e., 2%, when compared to the international figures. Majority of women graded their pain as dull aching type (47.5%) and moderate to severe in intensity. The circadian rhythm of back pain was observed in 56% of the patients, and out of that, insomnia was complained by 33% of the patients. Limitation of physical activity was observed in 62.5% of the patients.

Conclusion:

A negative correlation was observed between the serum calcium levels and parity; however, a positive correlation between the intensity of pain and parity was observed.

Keywords: Female, low back pain, pelvic girdle pain, pregnancy, serum calcium

INTRODUCTION

The occurrence of pregnancy-induced low back pain (LBP) is very common during pregnancy.[1] A plethora of prospective and retrospective studies exist regarding the epidemiology of pregnancy-related back pain, and the prevalence ranges from 25% to 90%.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Pregnancy-related LBP usually begins between the 20th and the 28th weeks of gestation, and the exact duration varies.[12]

All over the globe, majority of pain management services whether for acute or chronic pain are provided by the anesthesiologists and the later along with the obstetricians are involved in the multidisciplinary management of pain in obstetric patients. Hence, the anesthesiologists must understand the pathophysiology and risk factors of pregnancy-induced LBP.

There are hardly any data available till date in relation to the prevalence of pregnancy-related LBP, especially pelvic girdle pain (PGP) in the Indian-Asian population. Literature search reveals a high prevalence of hypocalcemia in pregnant patients among the Asian population.[13,14] However, on PubMed and Medline search, it was realized that there are no data available on the serum calcium estimation in patients with back pain in pregnancy.

The purpose of this study is to determine the period and point prevalence of back pain during pregnancy and to study the associated risk factors and its various aspects such as nature, intensity, character, radiation, circadian pattern, and limitation of physical activities. A further aim is to evaluate the serum calcium levels at a given point in pregnancy and to correlate it with the parity, severity of back pain, and socioeconomic factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present cross-sectional survey was undertaken after the clearance from the Institutional Ethical Committee – Human. The study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital in the city of Delhi, India, and was done over a period of 8 months. The place was chosen for the study as it has a large turnout of pregnant women from low socioeconomic strata and possibly most prone to develop LBP during pregnancy. Two hundred and twelve pregnant women attending the antenatal outpatient clinic were involved in this study which was conducted over a period of 10 months. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Purposive sampling was done, and every third patient in the obstetric outpatient department was enrolled in the study. All healthy pregnant women with no bad obstetric history were included. The patients were excluded from the study if they were found to have any obstetric problem in the present pregnancy, bad obstetric history, or urologic disorders or with any uncommon causes of back pain such as ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteomalacia.

The pregnant women were asked to fill a questionnaire which included a detailed medical, socioeconomic, vocational, educational, previous hospitalization and history of back surgery [Annexure 1]. Each woman was asked if she had any back pain during surgery. Women with ongoing back pain were asked in a more detailed fashion regarding the aggravation/reduction of pain with the onset of pregnancy. All pregnant women were provided with a diagram projecting the posterior view of female human body. They were instructed to map out a pain-drawing area on the back (upper back/lower back/sacroiliac/radiation to posterior thighs/posterior legs). Patients were also inquired for any complaints of pain in pubic symphysis area that is associated with back pain. Further, a detailed evaluation of back pain was done based on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scoring. Pregnant women were also evaluated for the effect of back pain on the limitation of their activities of daily living such as routine kitchen work, cleaning, dishwashing, floor mopping, or getting confined to bed due to severe back pain. The frequency and the radiation of back pain were explored. To study the circadian pattern of back pain in pregnancy, these patients were asked that whether the back pain occurred predominantly in the night or at daytime and if it occurs at night whether it contributed to insomnia. They were asked the time range at which the peak effect of back pain was experienced.

Venous blood samples were drawn to evaluate the serum calcium levels in pregnant women complaining of back pain. A sample of 2 mL venous blood was taken, and the calcium levels were evaluated by ortho-cresolphthalein complexone method.

Physical examinations included complete back and neurological evaluations. Special attentions were directed toward the sacroiliac joint during examinations since sacroiliac subluxation has been described as a common cause of lower back pain in parturient. The diagnostic criteria and confirmatory signs were evaluated in all the patients as per the details given in Table 1. Positive straight leg raise test is consistent with either sacroiliac subluxation or herniated nucleus pulposus. Unilateral loss of knee or ankle reflexes or presence of sensory or motor deficits is suggestive of lumbar nerve root compression at corresponding levels.

Table 1.

Criteria for diagnosis and frequently found confirmatory sign in sacroiliac subluxation or pelvic girdle pain

| Criteria or sign | Description |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| Sacral pain | Pain is usually unilateral and in some cases radiates to the buttock, lower abdomen, anterior medial thigh, groin, or posterior thigh |

| Pelvic pain | Pain in sacral area is provoked by direct bilateral downward pressure on the anterior superior iliac spine |

| Asymmetry of the anterior superior iliac spine | Anterior superior iliac spine should be examined with patients in supine position to eliminate the effect of leg length discrepancy, as in sacroiliac subluxation, one iliac spine will be higher than the other |

| Confirmatory signs | |

| Active straight leg raise test | Passive raising of patients’ leg, with the knee extended and patients in supine position, causes pain, usually at the end range |

| Positive Patrick’s test | Placing one heel on the opposite knee in the recumbent position and simultaneously rotating the leg outward provokes pain |

| Tenderness at Baer’s test | A point of acute tenderness, just to side and below the umbilicus on the painful side |

| Which is about one-third of the way between the umbilicus and ASIS |

ASIS=Anterior superior iliac spine

Sample size calculation

Considering the prevalence of pregnancy-related LBP to be 76%[13] and a relative marginal error of 10% and an alpha error of 5%, a sample size of 125 cases was required. Further reducing the marginal error to 8%, a sample size of 190 cases was needed. To compensate for the dropouts, we have included 212 patients over a period of 8 months.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained was entered into a Microsoft Excel Sheet, which was then imported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Inc. 233 South Wacker Drive, 11th floor, Chicago, IL, USA) for calculating descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation (SD), and percentages. Bivariant correlation of parameters such as VAS score and serum calcium levels was done with factors such as parity, socioeconomic status, and nature of pain.

RESULTS

The results were based on a cross-sectional descriptive study, conducted among 212 pregnant women with gestational period between the 8th and the 36th weeks, at the antenatal clinic of a tertiary hospital in the capital of Delhi, India. The mean age of the parturient was 24.24 ± 3.20 years. Of 212 patients, 11 patients did not complete the questionnaire. The response rate was, therefore, 92% (201/212). Forty-five percent of women were pregnant for the first time and 36% patients for the second; 19% had been pregnant more than twice.

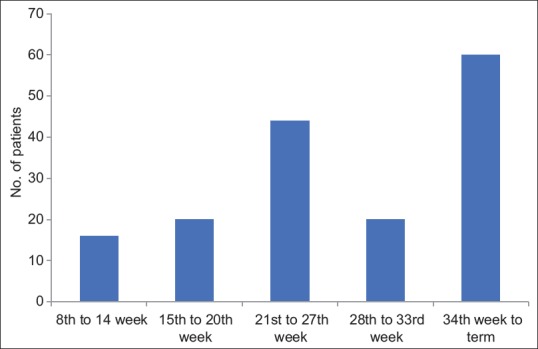

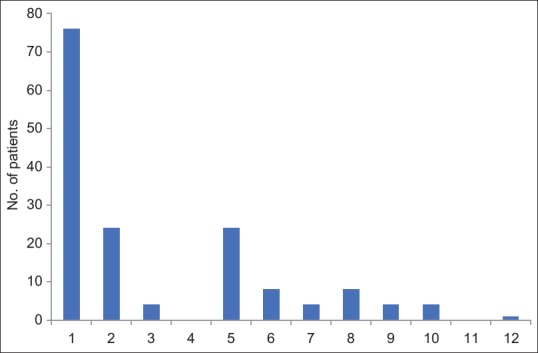

The point prevalence of back pain was found to be 80% or 162/200 and was found maximum in the 34th week to term group. Out of 160 patients who had LBP, 47 % were pregnant for the first time, 33% for the second time and 20 % had been pregnant more than twice. The number of patients in various gestation groups is given in Figure 1. Ninety-one percent of the patients with LBP were observed to be from low socioeconomic status.

Figure 1.

Point prevalence of low back pain during pregnancy

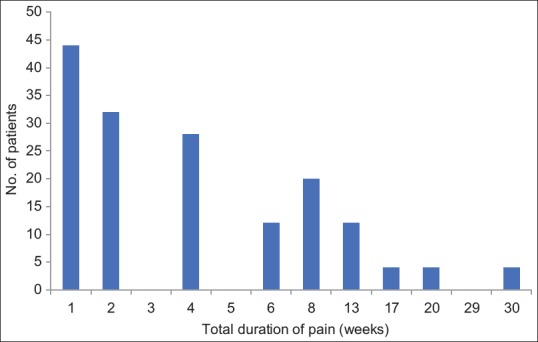

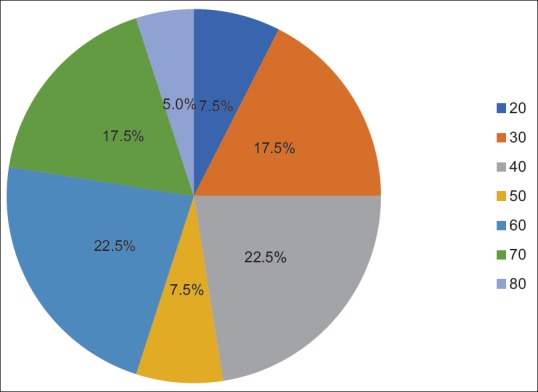

The total duration of pain till date from the beginning of symptoms is illustrated in Figure 2. The patient marked their intensity on VAS pain scale. Majority of the patients i.e., 70% graded it between 40-70; whereas, 17.5 % marked a pain score of 22.5 % of patients graded ≥70 [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Total duration of pain till date from the beginning of symptoms

Figure 3.

Intensity of back pain on Visual Analog Scale

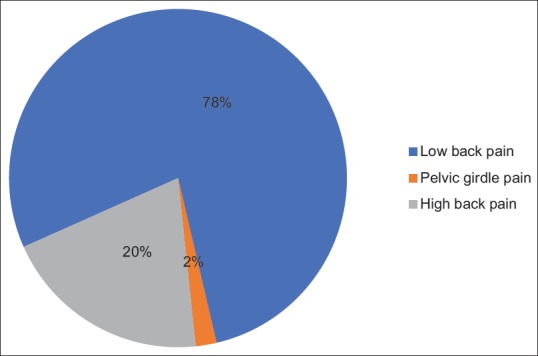

The patients complaining of back pain were also asked to map out the pain-drawing areas on the back. Regarding the nature of pain (high back pain, low back pain, and PGP), maximum number of women had LBP (78%) and 20% complained of high back pain (HBP). The prevalence of PGP was found to be only 2% [Figure 4]. The confirmatory pain provocation tests were found to be positive in this set of patients.

Figure 4.

Types of back pain

In the study of character of pain, maximum number of patients had a pain of dull aching type which was 47.5% (n = 76) [Figure 5]. The phenomenon of radiation of pain was observed in 48% of the patients (76 patients). The presence of circadian rhythm was seen in 56% of the patients (n = 90) who had regular time period of pain occurring either at daytime or at night. The predominant occurrence of pain was observed to be in the nighttime (52.5%, n = 84). Of all patients who had pain during nighttime, only 33.3% had associated insomnia (n = 28). Of the total 28 patients who had LBP with insomnia, 16 patients had pain during early night period and 12 patients had pain in early morning with none occurring in the midnight category.

Figure 5.

Character of back pain. 1 = Dull aching, 2 = Sharp, 3 = Shooting, 4 = Stabbing, 5 = Hot burning, 6 = Splitting, 7 = Sickening, 8 = 1 and 2, 9 = 1 and 3, 10 = 1 and 5, 11 = 5 and 6, 12 = 1, 2, and 5

Due to the high intensity of pain and continuity throughout the day, many patients had limitations in performing daily chores which resulted in patients resorted to bed rest which was of some hours to complete day in many cases. Limitation of physical activity was observed in 62.5% of the patients (n = 75).

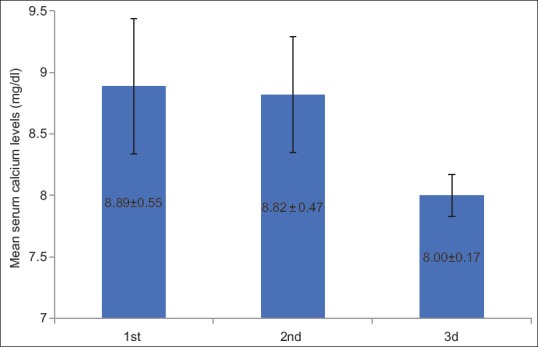

Bivariant correlation of parameters such as VAS score and serum calcium levels was done with various factors such as parity, socioeconomic status, and nature of pain. On correlation of VAS with parity, the mean SD was observed to be 49.25 (17.45) and a positive correlation was observed (P = 0.514). Similarly, on correlation of serum calcium levels with parity, a negative correlation was observed and the correlation (Spearman correlation) value was observed to be 0.081 (P = 0.037) [Figure 6]. The bivariant correlation of VAS score and serum calcium levels with socioeconomic status and nature of pain was not found to be significant. Furthermore, the correlation between the VAS score and serum calcium levels among each other was also not found to be significant.

Figure 6.

Relation of serum calcium levels with parity

DISCUSSION

The present cross-sectional survey shows a higher point prevalence of LBP of 80% with a significantly lower prevalence of PGP, i.e., 2% in 212 Indian women, when compared to the international figures.

LBP is a commonly encountered pathophysiological process of pregnancy. A plethora of studies exist regarding the epidemiology of pregnancy-related LBP. In the 1970s and 1980s, the 50% prevalence of LBP had been widely quoted by various prospective and retrospective studies.[2,3,4,5] Recently in the past two decades, the magnitude of the problems of back pain has been evaluated by various authors in various prospective and retrospective studies. Various cross-sectional surveys found the prevalence of LBP to be around 32%–72%.[3,6,7,8,9,10] In the present study, we found the point prevalence of back pain to be 80% with a value of 88.2% in the 34th to term group which is higher than the international findings found in various studies.

LBP and posterior pelvic pain were considered as one entity in the past research and were grouped under the single classification of LBP, and Bastiaanssen et al.[15] were among the first few to set the criteria for the two. Recently, there are two different patterns of pregnancy-related LBP, i.e., lumbar pain (LP) and PGP.[12] LP is localized to the lumbar spine and above the sacrum, whereas PGP is deep stabbing, recurrent and continuous, between posterior superior iliac spine and gluteal folds and radiating to the thigh, knee and calf. Posterior PGP in pregnancy is generally acute and has diffused anatomic origin over the sacroiliac area (L4–S1).[9] Because of the difference in the location of pain, the physical examination, and results of the provoking tests, they are now considered as two separate entities. Pain provocation tests such as active straight leg raise tests, Patrick's test, and Baer's tests are positive in cases of PGP or sacroiliac pathology.[16,17]

PGP has been reported to be more incapacitating and has found it to be 2–4 times as frequent as LP.[18] In 1998, a higher prevalence of PGP was reported by Wergeland and Strand[19] findings, whereas in the same year, no difference was found between the two.

On the contrary, recently, the prevalence of PGP has been reported to be around only 20%.[12,20] A cross-sectional study to reveal the prevalence of PGP in the first 3 months in the postpartum period in the Indian population has revealed a high prevalence of PGP, i.e., 41%.[21] No data are available in regard to the prevalence of intrapartum PGP in the Indian/Asian population. The present study divides the back pain into HBP and LBP with or without radiation into one or both legs, and the third group included women with pain over the sacroiliac joint area, may be radiating to the thighs, i.e., PGP. Unlike the previous studies, the prevalence of PGP during pregnancy was found to be very low, i.e., 2%. The reason could be that in a developing country like ours, the patients continue physical activity in the form of routine household chores right till the last trimester.

Various risk factors associated with LBP are history of LBP during previous pregnancies, multiple abortions, smoking, age, parity, ethnicity, use of oral contraceptives, educational level, low socioeconomic status, occupation, and vocational risks. In the present survey, we studied the risk factors such as age, parity, gestational age, socioeconomic status, and history of previous back pain. Various studies have reported a high prevalence of LBP with increasing age,[2,4] while others have reported it with young age.[1,5] However, few authors have reported no association between the age and LBP among pregnant women.[3,5] Similarly, some studies identified multiparity as a risk,[1,2,4,9] whereas some denied any association between the two.[3,5] In the present survey, no association between age and LBP was observed; however, multiparity was observed to be associated with the higher occurrence of LBP. As far as the socioeconomic status is concerned, Orvieto et al.[5] had identified low socioeconomic status as a risk factor for LBP; however, Björklund and Bergström[22] have concluded that low socioeconomic status plays no role in the occurrence of LBP among pregnant women. In the present survey, 90% of the patients with LBP were observed to be from low socioeconomic status. Similarly, previous history of back pain has also been considered to be a strong predictor of LBP.[4,9] In the present survey, majority of the patients (72%) complained of previous back pain.

LBP associated with radiation into the buttocks and legs is a commonly encountered problem during pregnancy. In all these cases, radicular and other neurologic symptoms such as true sciatica, posterior facet syndrome,[23] and meralgia paresthetica[24] must be excluded. In addition, pregnancy itself may be associated with lumbar herniation at L5–S1 disk level, spondylolisthesis, and osteonecrosis of the hip due to mechanical and hormonal factors.[4,25] The radiation of pain was observed to be 45% in the study by Fast et al.[3] which is near similar to the present survey results, i.e., 52%.

The pregnancy-induced physical changes and combination of social and psychological factors are mainly responsible for limitation of physical activities as the pregnancy progresses.[26] In the present study, it was observed that 38% of the patients had limitations of physical activity. On the contrary, a high incidence of insomnia (58%) and limitation of physical activity (57%) were reported by Wang et al. in anonymous 950 prospective surveys done in pregnant women participating in various prenatal clinics in the USA.[6]

In the present cross-sectional survey, the serum calcium levels of the parturient with LBP were done and were correlated with various other factors such as VAS score, duration of pain, and parity. The serum calcium levels and parity demonstrated a significant negative correlation, whereas VAS and parity showed a significant positive correlation. A negative correlation between serum calcium levels and parity has been observed. We hypothesize that high parity seen in the Indian population could be the probable cause of low calcium levels which might have a direct link to the pathogenesis of back pain in pregnancy and could be an attributing factor for such high incidence of LBP in India. To our knowledge, there are no data available in regard to the association of serum calcium levels with LBP among pregnant women.

The limitations of the present cross-sectional survey include data from a single tertiary care center and serum calcium levels’ estimation irrespective of the period of gestation. On literature search, it was revealed that the difference in the serum calcium levels is not significant during various trimesters of pregnancy.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, the point prevalence of back pain as 80% in the Indian population is much higher than the global findings. On the contrary, the prevalence of PGP during pregnancy was found to be only 2%, which is significantly lower than the reported prevalence in the literature. The serum calcium levels and parity demonstrated a significant negative correlation, whereas VAS and parity showed a significant positive correlation. Further multicentric trial involving a larger sample size is needed to confirm the low prevalence of intrapartum PGP and positive correlation of serum calcium levels with LBP in a developing country like India.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ANNEXURE

Annexure 1

PRO FORMA

ID No.

Name:

Age/Sex:

Gestation:

Parity:

Socioeconomic status:

Previous history of back pain:

Back pain in current pregnancy – Yes/No

Duration and onset of back pain

-

Nature

- High back pain

- Low back pain

- Sacroiliac pain

Intensity and severity (including VAS score)

Character (dull aching/sharp/shooting/stabbing/hot-burning/splitting/sickening)

Radiation

-

Circadian rhythm of back pain

- Predominant occurrence of back pain – day/night

- If at night, associated insomnia – Yes/No

- Time range of peak effect of back pain

Limitation of physical activities

Pain in pubic symphysis associated with back pain – Yes/No

Serum calcium levels:

Coding Text for Pro forma

Gestation age (in weeks) –

Socioeconomic status – monthly family income

Less than 2000, 2000–5000, 5000–7000, 7000–10,000, and above 10,000

P1 – Back pain – Yes/No

P2 – Total duration of pain till date from beginning of first encounter (in weeks)

P3 – Nature of pain

High back pain – 3, Sacroiliac pain – 2, Low back pain – 1

P4 – Intensity (VAS score) – 0–100

P5 – Character of pain

Dull aching -1, Sharp – 2, Shooting – 3, Stabbing – 4, Hot burning – 5, Splitting – 6, Sickening – 7

P6 – Radiation – Yes/No

P7 – Circadian rhythm – Yes/No

P7a – Predominant occurrence day – 1, Night – 2, Not any – 3

P7b – Associated insomnia, Yes/No/NA

P7c – Time range of peak effect – Early night (up to 10 p.m.) – 1, Midnight (10 p.m. – 4 a.m.) – 2,

Early morning (4–6 AM) – 3

P8 – Limitation of physical activity – Yes/No

P9 – Pain in pubic symphysis – Yes/No

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB, Karlsson K. Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:549–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantle MJ, Greenwood RM, Currey HL. Backache in pregnancy. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16:95–101. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/16.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fast A, Shapiro D, Ducommun EJ, Friedmann LW, Bouklas T, Floman Y. Lowback pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987;12:368–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB. Previous back pain and risk of developing back pain in a future pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:432–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orvieto R, Achiron A, BenRafael Z, Gelernter I, Achiron R. Lowback pain of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:209–14. doi: 10.3109/00016349409023441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SM, Dezinno P, Maranets I, Berman MR, CaldwellAndrews AA, Kain ZN. Low back pain during pregnancy: Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:65–70. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000129403.54061.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce H, Homer CS, Dahlen HG, King J. Pregnancyrelated lumbopelvic pain: Listening to Australian women. Nurs Res Pract 2012. 2012:387428. doi: 10.1155/2012/387428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimoh AA, Omokanye LO, Salaudeen AG, Saidu R, Saka MJ, Akinwale A, et al. Prevalence of low back pain among pregnant women in Ilorin, Nigeria. Med Pract Rev. 2013;4:236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogren IM, Pohjanen AI. Low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy: Prevalence and risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:98391. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158957.42198.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazicioglu M, Tucer B, Ozturk A, Serin IS. Low back pain and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2006;19:8996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kesikburun S, Güzelküçük Ü, Fidan U, Demir Y, Ergün A, Tan AK, et al. Musculoskeletal pain and symptoms in pregnancy: A descriptive study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2018;10:229–34. doi: 10.1177/1759720X18812449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katonis P, Kampouroglou A, Aggelopoulos A, Kakavelakis K, Lykoudis S, Makrigiannakis A, et al. Pregnancyrelated low back pain. Hippokratia. 2011;15:205–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weis CA, Barrett J, Tavares P, Draper C, Ngo K, Leung J, et al. Prevalence of low back pain, pelvic girdle pain, and combination pain in a pregnant Ontario population. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:1038–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Agarwal K, Devi SG, Gupta RK, Batra S. Hypocalcemia in pregnant women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;136:2632. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA. A historical perspective on pregnancyrelated low back and/or pelvic girdle pain. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:794–819. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haugland KS, Rasmussen S, Daltveit AK. Group intervention for women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1320–6. doi: 10.1080/00016340600780458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostgaard HC, Zetherström G, RoosHansson E. Back pain in relation to pregnancy: A 6 year followup. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:2945–50. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wergeland E, Strand K. Work pace control and pregnancy health in a populationbased sample of employed women in Norway. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:206–12. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brynhildsen J, Hansson A, Persson A, Hammar M. Followup of patients with low back pain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:182–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukkannavar P, Desai BR, Mohanty U, Kulkarni S, Parvatikar V, Daiwajna S. Pelvic girdle pain in Indian postpartum women: A crosssectional study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30:123–30. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.816399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björklund K, Bergström S. Is pelvic pain in pregnancy a welfare complaint? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:24–30. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079001024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard TN, Jr, KirkaldyWillis WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(217):266–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norén L, Ostgaard S, Nielsen TF, Ostgaard HC. Reduction of sick leave for lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:v2157–60. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutke A, Boissonnault J, Brook G, Stuge B. The severity and impact of pelvic girdle pain and lowback pain in pregnancy: A multinational study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:510–7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shakhmatova EI, Osipova NA, Natochin YV. Changes in osmolality and serum ion concentrations in pregnancy. Hum Physiol. 2000;26:92. [Google Scholar]